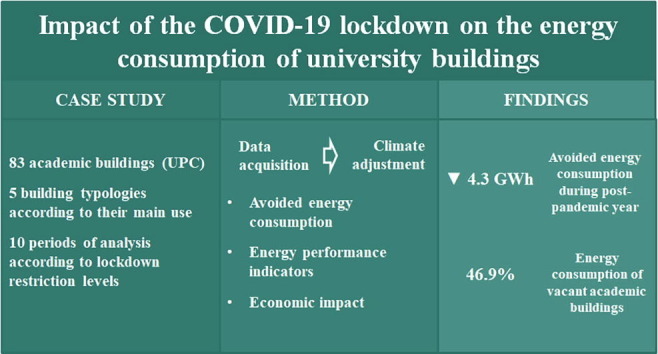

Graphical abstract

Keywords: COVID-19, Lockdown, Energy consumption, Avoided energy, Academic buildings, Universities

List of Abbreviations: CDD, Cooling degree days; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; ESEIAAT, School of Industrial, Aeronautical and Audiovisual Engineering of Terrassa; HDD, Heating degree days; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2; UPC, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya - Barcelona Tech

Abstract

Exceptional pandemic lockdown measures enabled singular experiments such as analysing the energy consumption of vacant buildings. This paper assesses the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the energy use of academic buildings. For this purpose, weather-adjusted energy use was compared before and during the lockdown, including different levels of lockdown restrictions. Results obtained for the 83 academic buildings of Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya - Barcelona Tech (UPC) reveal that the avoided energy consumption amounted to over 4.3 GWh during the post-pandemic year. However, the results indicate that academic buildings were still using approximately 46.9% of their typical energy consumption during strict lockdown. This revelation emphasizes the high environmental burden of buildings, regardless of whether they are occupied.

1. Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a global pandemic [22]. Urgent measures were adopted to contain the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, including stay at home orders, mandatory quarantines and restricted movements, among others. One year after the COVID-19 outbreak, restrictions still continue and might be prolonged with different intensities, depending on national or localised outbreaks.

Along with the staggering loss of life, the pandemic has undoubtedly disrupted lives, businesses and economies [34]. The pandemic is also having an unprecedented impact on education worldwide. Over 190 countries have implemented closures of educational institutions, affecting over 94% of the world’s student population [35].

Although the impacts of COVID-19 on health systems and national economies have been covered extensively in the media, the implications of the disease for energy and climate policy are more prosaic [34]. Even in the research field, the impact of COVID-19 on energy consumption has not been extensively studied until now although Zhang et al. [40] recently highlighted it as one of the top research hotspots. In addition, most of the existing research has focused on evaluating the impact of the coronavirus lockdown on aggregated energy demand and consumption at country, regional or local level. As way of example, Abu-Rayash and Dincer [2] investigated the effects of the global pandemic on the energy sector dynamics for the province of Ontario (Canada). Norouzi et al. [26] analysed the impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak on the electricity and petroleum demand in China. Abulibdeh [3] assessed the impact of the pandemic on electricity consumption patterns in the State of Qatar. Santiago et al. [30] analysed the Spanish electricity demand and load patterns in during pandemic times. Other researchers such as Jiang et al. [21], Krarti and Aldubyan [24] and Smith et al. [32] conducted more global studies, taking into account various states. Zhang et al. [39] investigated the impact of lockdown measures due to COVID-19 pandemic on energy demand of a building mix including residential buildings, offices, schools and retail shops in a district in Sweden by simulating the energy performance. Bielecki et al. [5] analysed changes concerning residential electricity consumption comparing data from energy meters from almost 7000 flats in Warsaw’s housing estates during the lockdown in 2020 to the pre-pandemic period. Garcia et al. [15] used smart meter data to analyse the consumption behaviour of residential users in a Spanish location during the COVID-19 pandemic. Zhang et al. [41] analysed the energy consumption of different building typologies, including hotels, transportation, tourism culture, and public utilities in commercial tourism cities.

Only a few studies have targeted individual buildings. Residential buildings were recently addressed by Abdeen et al. [1], who analysed 500 homes in Ottawa (Canada), de Frutos et al. [10], who studied 12 dwellings located in Madrid during Spain’s state of emergency, Kawka and Cetin [23], who measured the shifts in electricity use in 225 housing units located primarily in Austin (the United States) over the years 2018–2020 at a disaggregated level, and Rouleau and Gosselin [28], who assessed the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown measures on the energy consumption in 40-dweling social housing in Quebec city (Canada). Finally, Cvetković et al. [9] simulated four scenarios to assess the impact of people’s behaviour on the energy and water consumption in a household located in Kragujevac (Central Serbia) in circumstances similar to the COVID-19 pandemic. Tertiary-sector buildings have been studied by a small number of researchers. Ding et al. [11] analysed educational buildings (primary and secondary schools) and residential buildings with electric heating in Norway to identify potential deviations in electricity use patterns. Geraldi et al. [16] assessed how the COVID-19 lockdown measures affected electric energy use of municipal buildings (health centres, administrative buildings, elementary schools and nursery schools) in Florianópolis (Brazil). Kang et al. [18] conducted a study in South Korea analysing changes in building energy consumption during the COVID-19 lockdown according to the building use type. Lastly, Samuels et al. [29] evaluated the energy demand of five public schools in South Africa along with occupancy variations due to the COVID-19-imposed lockdowns. Other authors such as Cortiços et al. [8] and Faulkner et al. [14] simulated energy consumption, CO2 emissions and operational costs of office buildings in post COVID-19 scenarios.

Following the coronavirus outbreak, universities closed their doors and immediately transitioned to distance learning. Academics quickly adopted digital tools for lectures, conferences and meetings during the lockdown. Many universities held lectures online during the last part of 2019–2020 and the entire 2020–2021 academic year. In other cases, a hybrid model has been adopted, combining mainly theoretical online lessons with in-person lab sessions. In addition, universities around the world are still uncertain about when measures such as physical distancing might end completely.

Theoretically, the energy consumption of academic buildings should drop when they are empty. However, minimum operating levels are required to ensure that core activities can be performed remotely (i.e. servers and data centres ensuring access to email, databases or software tools). In addition, essential building services must remain on, such as emergency lights and elevators. Sometimes, shutting down HVAC systems can compromise indoor conditions or cause technical problems that would complicate fast building reopening. Plug loads such as computers, monitors, printers or audio–video equipment might not have been disconnected when the building was closed and could therefore have been consuming energy throughout the period. Although the individual energy consumption of miscellaneous loads is relatively small, they can end up using a significant portion of buildings’ energy because of a large, steadily increasing number of devices, their wide distribution around buildings and their invisibility.

The COVID-19 crisis provided a unique opportunity to measure on-site the energy consumption of vacant buildings and to devise energy saving options. This is even more relevant as people are expected to study and work from home more often in the future. To the authors’ knowledge, only two studies have focused on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on energy consumption of university buildings. Chihib et al. [7] assessed the impact of closing thirty-three buildings across the University of Almeria (Spain) on the energy use of its different facilities. Gui et al. [17] studied the energy use changes of one hundred and twenty-two university buildings of the Griffith University (Australia), and identified corresponding facilities management strategies for future e-learning modality. Unfortunately, these studies did not take into account the influence of the climate variations when reporting changes in energy consumption.

The main objective of this paper was to analyse the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the energy consumption of university buildings taking into account climate adjustments to baseline period conditions. The methodology was applied to 83 academic buildings of Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya - Barcelona Tech (Spain).

Following this introduction, Section 2 describes the methodology, Section 3 presents the case study and Section 4 presents and discusses the results obtained for the case study. Finally, conclusions are detailed in Section 5.

2. Methodology

The methodology used to estimate the impact of the coronavirus lockdown on the energy consumption of university buildings consists of three steps, as shown in Fig. 1 :

-

•

First, spatial and temporary study boundaries are defined by selecting buildings to be analysed and establishing study periods and their estimated occupancy.

-

•

Second, data acquisition process is described. This step encompass data collection process and subsequent data filtering process as raw data usually requires correction and cannot be used directly.

-

•

Third, the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the energy consumption is evaluated by determining the avoided energy consumption during the post-COVID period compared to the analogous period before the pandemic (covering a full year), considering routine adjustments such as climate conditions and building activity levels. Afterwards, the impact on the overall energy consumption through energy performance indicators is explored and the economic impact of the avoided energy consumption is evaluated.

Fig. 1.

Methodology.

2.1. Definition of spatial and temporal study boundaries

This step involves determining which buildings are going to be analysed. To make an adequate comparison, the selected buildings must be characterised in terms of year of construction, floor area and type of building depending on use. Most academic buildings are intended for more than one use (i.e. teaching rooms, research laboratories, libraries, sports centres, academic and administrative offices, etc.). When the energy consumed by buildings is not sub-metered for individual functional areas, the main use of a building determines the type of building. In this study, the main use of a building is defined as that for which over 50% of its built area is destined. In the event that the area devoted to different uses in a building is similar, without exceeding 50%, the building is classified as mixed use. For each type of building, the operating period and the occupancy levels are identified.

Restrictions and their temporally evolution depend on the decisions made by state and local governments. Study periods must be defined according to the restriction levels or the building activity levels, which is the same thing.

For the sake of comparison, reference consumptions are identified by comparing corresponding periods over past years, considering that the number of working days and weekends must be kept within the period. Ideally, the control period should cover at least one year. Other control periods can be used (i.e. the average of the two years immediately preceding the lockdown) but the results might be similar to those obtained from a one-year control period [28].

2.2. Data acquisition

This step entails the creation of a dataset of the buildings that are analysed, including information about the buildings’ main characteristics (construction year, floor area and main building use) and energy-related data. COVID-19 impacts on energy use must be differentiated from those due to other factors that might affect the energy performance of the building in the study period. Along the lines of the International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol [12], a building’s energy performance might be affected by routine and non-routine events. Routine events are conditions affecting the energy consumption that vary in a predictable way (i.e. weather variations, changes in the number of enrolled students, etc.) whereas non-routine events are characteristics that are not expected to routinely change (i.e. changes in the amount of space being heated or cooled, changes in the buildings’ envelope characteristics, changes in the buildings’ equipment, changes in indoor air conditions, etc.). Therefore, in this step of the methodology, data related to routine and non-routine adjustments must be collected (i.e. daily outdoor temperature records and total enrolment).

Energy performance certificates are a valuable source of information for buildings’ main characteristics (i.e. construction year, floor area). Regarding the type of building, the information on the use of spaces can be acquired from the graphic documentation of the building. Building typologies might differ significantly in occupancy patterns, in terms of operating periods (both yearly and daily) and occupation density.

Preferably, energy-related data should be retrieved from smart meter data platforms. Alternatively, meter readings or issued bill readings, which are usually provided by building managers, can be used. It might be better to exclude buildings with missing or inaccurate data from the analysis.

Daily outdoor temperature records can be obtained from the closest meteorological stations. Typically, the number of enrolled students can be found in university annual reports. However, this analysis can only be performed at school level and each school may be based in more than one building.

2.3. Evaluation of the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on energy consumption

The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the buildings’ energy consumption was evaluated by determining the avoided energy consumption during the post-COVID period compared to the control period (Section 2.3.1), by exploring the impact on the overall energy consumption through energy performance indicators (Section 2.3.2), and by estimating the economic impact of the avoided energy consumption (Section 2.3.3).

2.3.1. Determination of avoided energy consumption

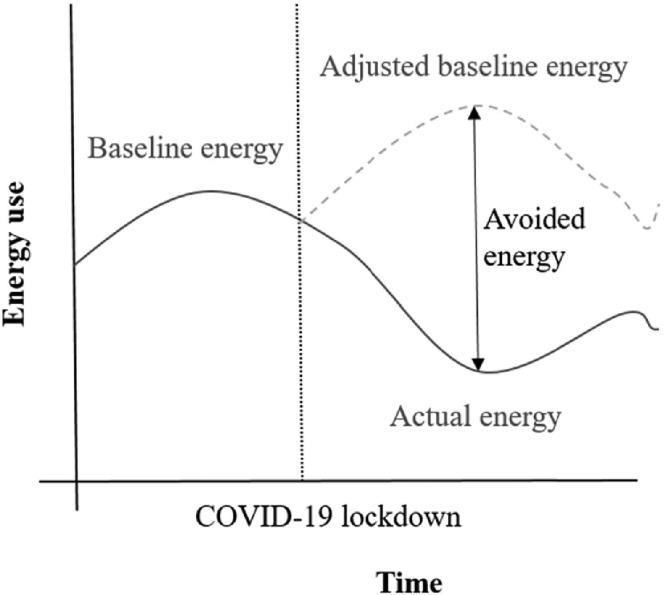

Along the lines of the Efficiency Valuation Organization [12], the comparison of energy consumption before (pre-COVID periods) and after (post-COVID periods) the lockdown (Fig. 2 ) should be made using the following equation:

| (1) |

where E avoided represents the avoided energy consumption, E adjusted baseline is the adjusted baseline energy consumption or the baseline energy consumption adjusted to routine adjustments, E actual denotes the actual energy consumption and NRA represents non-routine adjustments to reporting period conditions.

Fig. 2.

Estimation of avoided energy consumption due to COVID-19. Source: adapted from the Efficiency Valuation Organization (2016).

Therefore, energy impacts due to the COVID-19 outbreak can be tracked by adapting the Efficiency Valuation Organization [12] guidelines:

a) Development of a mathematical model correlating actual energy consumption with appropriate independent variables in the pre-COVID-19 period. Baseline data should be representative of at least a year. Within the context of academic buildings, common independent variables are number of students enrolled and weather (often simplified to outdoor dry-bulb temperature and later transformed into heating and/or cooling degree days). Heating degree days (Eq. (2)) and cooling degree days (Eq. (3)) measure how cold or warm a specific location has been during a certain amount of time, respectively.

| (2) |

| (3) |

where Theating base is the outdoor temperature below which the building needs heating, Tcooling base is the outdoor temperature above which the building needs cooling, Toutdoor is the outdoor temperature and N is the number of days of the period to be studied. In any case, base temperatures (also known as balancing points) need to be properly defined according to each case.

b) Independent variables are inserted into the baseline mathematical model to obtain the adjusted base energy during the post-COVID period.

c) Differences between the actual energy consumption (metered data) during the post-COVID period and the adjusted baseline energy consumption over the applicable time interval are calculated.

d) The cumulative sum of differences (CUSUM) is calculated and plotted according to the Efficiency Valuation Organization [13]. Note that the cumulative sum of differences can only be attributed to the COVID-19 effect if no other significant changes have occurred during the analysed periods, including the implementation of energy saving measures.

Data granularity always depends on their availability. If smart meter data is available for all the energy supplies, daily analysis is preferred. If available data is on a monthly basis for any reason, the analysis should be weekly at most, so as not to misunderstand weekday and weekend energy consumption profiles.

2.3.2. Impact on energy performance indicators

Energy performance indicators are identified by answering two key performance questions: (i) Did the COVID-19 lockdown have an impact on the building’s energy consumption overall? and (ii) If so, what is the impact on the building’s energy consumption for each period of the COVID-19 lockdown? Selected indicators are summarised in the following equation:

| (4) |

where Ii j is the average daily energy consumption as a function of the adjustment factors calculated for the j period and Et represents energy consumption during the entire j period, expressed in kWh. Average daily energy consumption data, including energy for heating and cooling, is used. To obtain more accurate results, the average daily energy consumption for heating (Eh) expressed in kWh, and the average daily energy consumption for cooling (Ec) expressed in kWh can be used for the entire period, if possible. N denotes the number of days of the j period. AFi represents the adjustments factors that have an impact on the energy consumption of a building or facility. In this case, differences in consumption observed during the lockdown period might be influenced by routine adjustment factors such as the outdoor temperature and/or the building activity levels. To isolate the influence of outdoor temperature, heating degree days (HDD) and cooling degree days (CDD) are calculated following Eq. (2) and Eq. (3). To isolate the influence of levels of activity within the buildings, differences in the number of enrolled students between periods should be checked. Moreover, it should be noted that if a non-routine event occurs between the compared periods, the designed indicators should take this into account (i.e. an increase in a building’s floor area).

To determine the impact of the periods of the COVID-19 lockdown on energy consumption, each of the identified periods must be compared with the corresponding control periods in past years. The following equation (Eq. (5)) allows an estimation of the difference between the energy consumed during an abnormal situation and normal operating conditions:

| (5) |

where VR is the variation rate of indicator Ii expressed in %, I j lockdown represents indicator Ii calculated for the j period of the lockdown and I j control denotes indicator Ii calculated for the j period of the control period. A negative variation rate indicates that the energy consumed during the lockdown period was lower than the energy consumed during the analogous period before the pandemic.

2.3.3. Economic impact of the avoided energy consumption

Avoided energy consumption (Eq. 1) is translated into economic impact according to energy source prices. The overall economic impact provided by the avoided energy consumption is estimated using Equation (6):

| (6) |

where indicates the total economic impact in period j (in €/period), is the economic impact in period j in electricity (in €/period), and is the economic impact in period j in gas (in €/period).

3. Case study

This paper uses Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya - Barcelona Tech buildings as a case study. The sample included 83 buildings for 18 schools distributed across 9 campuses (Baix Llobregat, Diagonal Besòs, Diagonal Nord, Diagonal Sud, Manresa, Nàutica, Sant Cugat del Vallès, Terrassa and Vilanova i la Geltrú). Buildings are mostly located in the C2 climate zone, except those on the Campus de Terrassa that are in the D2 climate zone [33].

3.1. Definition of spatial and temporal study boundaries

According to the criteria established in the methodology (Section 2), UPC buildings were first classified according to their main use as teaching buildings, research buildings, office buildings, libraries, sports centres and mixed-use buildings. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the sample in terms of number of buildings, floor area and building age. Daily and yearly operating periods and occupancy patterns for each building typology are summarised in Table 2 .

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the analysed sample.

| Building typology | Number of buildings | Main characteristics | Minimum value | Lower quartile (25%) | Average (50%) | Upper quartile (25%) | Maximum value | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching building | 11 | Floor area (m2) | 863 | 2,311 | 3,791 | 3,936 | 9,421 | 2,248 |

| Construction year | 1,945 | 1,990 | 1,991 | 1,992 | 2,005 | 17 | ||

| Research building | 7 | Floor area (m2) | 263 | 458 | 1,320 | 3,403 | 5,391 | 2,034 |

| Construction year | 1,967 | 1,988 | 1,996 | 2,005 | 2,019 | 18 | ||

| Office building | 31 | Floor area (m2) | 2,218 | 2,848 | 3,049 | 5,919 | 18,565 | 4,454 |

| Construction year | 1,863 | 1,989 | 1,994 | 2,001 | 2,016 | 37 | ||

| Library | 6 | Floor area (m2) | 1,400 | 1,642 | 2,141 | 5,425 | 6,652 | 2,469 |

| Construction year | 1,908 | 1,995 | 1,999 | 2,005 | 2,009 | 38 | ||

| Sports centre | 1 | Floor area (m2) | 6,612 | 6,612 | 6,612 | 6,612 | 6,612 | – |

| Construction year | 1,998 | 1,998 | 1,998 | 1,998 | 1,998 | – | ||

| Mixed-use building | 27 | Floor area (m2) | 561 | 2,305 | 4,264 | 10,429 | 27,359 | 7,255 |

| Construction year | 1,934 | 1,964 | 1,969 | 1,994 | 2,016 | 22 |

Table 2.

Occupancy patterns for the identified building typologies.

| Building typology | Operating period |

Occupancy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | Yearly | ||

| Teaching buildings | 8:00–20:00 | 14/09–31/01 and 10/02–30/06 | High |

| Research buildings | 9:00–18:00 | 01/09–31/07 | Low |

| Office buildings | 8:00–18:00 | 01/10–31/05 | Low |

| 8:00–15:00 | 01/06–30/09 | Low | |

| Libraries | 8:30–18:00 | 14/09–30/06 | Medium |

| 8:30–14:00 | 01/07–31/07 and 01/09–13/09 | Low | |

| Sports centres | 8:00–22:00 | 01/09–31/07 | Low |

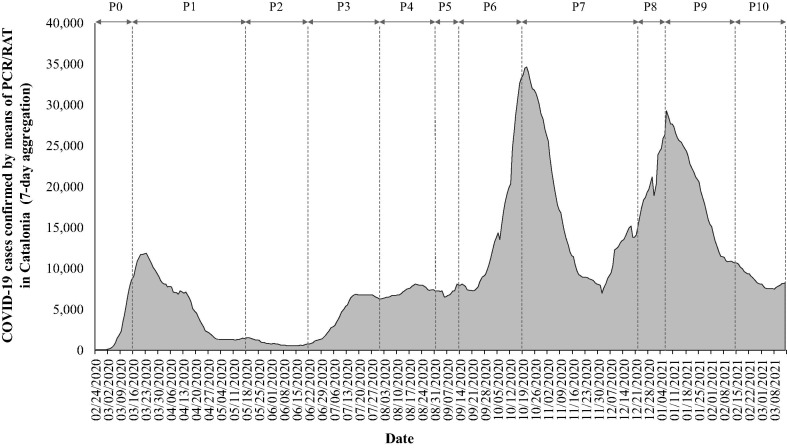

Regarding temporal study boundaries, on 13 March 2020 all face-to-face activities at Spanish universities were suspended. From that date on, universities went through different levels of lockdown depending on the pandemic’s evolution (Fig. 3 ). Table 3 summarizes the selected periods for this case study during the COVID-19 lockdown year (2020) and the corresponding control year in 2019.

Fig. 3.

Selected periods and COVID-19 cases confirmed by means of PCR/RAT (7-day aggregation) for epidemiologic monitoring in Catalonia. Source: adapted from Catalan Government [6].

Table 3.

Correspondence between lockdown and control periods and estimated occupancy.

| Period | Lockdown period |

Control period |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | Description | Estimated occupancy | Dates | |

| P0 | 10/02/20–15/03/20 | Beginning of the second semester 19/20 with normal operating conditions. | 100% | 11/02/19–17/03/19 |

| P1 | 16/03/20–17/05/20 | Total lockdown, access to buildings is prohibited. | 0% | 18/03/19–19/05/19 |

| P2 | 18/05/20–21/06/20 | Lockdown easing, access to buildings is allowed although occupancy is minimised and teleworking is maintained. | 5% | 20/05/19–23/06/19 |

| P3 | 22/06/20–31/07/20 | Resumption plan, buildings’ occupation is allowed at 50%. | 30% | 24/06/19–31/07/19 |

| P4 | 01/08/20–31/08/20 | Summer holidays. | 0% | 01/08/19–31/08/19 |

| P5 | 01/09/20–13/09/20 | Preparation of the first semester 20/21. | 10% | 01/09/19–15/09/19 |

| P6 | 14/09/20–18/10/20 | Beginning of the first semester 20/21. Face-to-face classes restricted to first year students and lab sessions. | 33% | 16/09/19–20/10/19 |

| P7 | 19/10/20–22/12/20 | Face-to-face classes are suspended, except lab sessions and exams. | 5% | 21/10/19–20/12/19 |

| P8 | 23/12/20–06/01/21 | Winter holidays. | 0% | 21/12/19–06/01/20 |

| P9 | 07/01/21–14/02/21 | Exam period (only a few of them are face-to-face) and preparation of the second semester 20/21. | 10% | 07/01/20–16/02/20 |

| P10 | 15/02/21–14/03/21 | Beginning of the second semester 20/21. Face-to-face classes restricted to first year students and lab sessions. | 33% | 17/02/20–15/03/20 |

3.2. Data acquisition

The buildings’ main characteristics, including construction year and floor area, were compiled from the UPC Planning, Assessment and Quality Bureau reports [36] and completed with information provided by the UPC Infrastructure Service. Existing drawings were used to determine building functions. When needed, on-site inspections were also conducted.

The number of registered students was collected using schools’ annual reports for 2018/2019, 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 (publicly available on the schools’ webpages) and UPC statistical and management data [37].

Smart meter data were collected through the UPC Sirena platform [38]. The collected dataset included quarterly electricity consumption data for almost all the buildings and almost all the periods in 2018, 2019 and 2020. To address existing gaps in smart metering data, estimates were used when no more than 12 consecutive quarterly electricity readings were missing. Unfortunately, end-use electricity sub-metering is not available for UPC buildings. Although gas consumption is monitored and displayed on the UPC Sirena platform [38], detected errors prevented its use and bills had to be used instead. Bills were provided by the UPC Infrastructure Service. In this case, meter readings were available on a monthly basis and they were proportionally distributed to fit the identified periods. In some cases, electricity and gas meter readings include more than one building (often a set of buildings comprising a school). Therefore, this determined the granularity of the analysis.

Average daily outdoor temperatures were taken from the closest meteorological station with open data. By way of example, average daily temperature records registered at the Barcelona University station were provided by the Meteorological Service of Catalonia [31] and used to calculated the degree-days for buildings located on the Campus Nord and Campus Sud. Meteorological data for buildings on the Terrassa Campus was retrieved from a weather station located in the centre of the city [20].

4. Results and discussion

The evaluation of the effects of the COVID-19 lockdown measures on university buildings encompasses the determination of the avoided energy consumption during the post-COVID period (Section 4.1), the determination of energy performance indicators (Section 4.2), and the estimation of the economic impact of the avoided energy consumption (Section 4.3).

The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions on UPC buildings’ energy consumption was evaluated in 50 buildings. The remaining buildings (Table 4 ) had to be discarded, as there were considerable gaps in the electricity readings or the monitoring infrastructure did not cover the analysed periods. For example, the B0 building (on the Diagonal Nord UPC Campus) was first monitored in 2020. Therefore, there were no available data for 2018 and 2019. In this case study, a weekly approach was chosen since gas consumption data were only available on a monthly basis.

Table 4.

Buildings outside of the scope of the analysis.

| UPC Campus | Number of buildings [ut.] | Buildings outside of the scope of the analysis [ut.] |

|---|---|---|

| Baix Llobregat | 7 | 4 |

| Diagonal Besòs | 3 | 3 |

| Diagonal Nord | 31 | 5 |

| Diagonal Sud | 12 | 8 |

| Manresa | 4 | 4 |

| Nàutica | 3 | 3 |

| Sant Cugat del Vallès | 2 | 2 |

| Terrassa | 15 | 0 |

| Vilanova i la Geltrú | 6 | 4 |

4.1. Determination of the avoided energy consumption

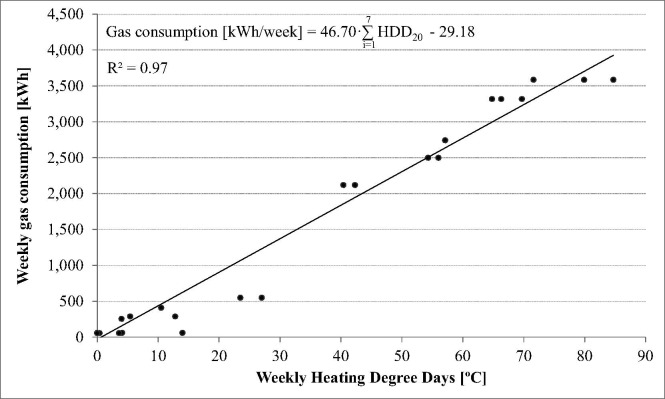

First, along the lines of what is stated in Section 2.3.1, a baseline energy consumption model was developed using actual energy consumption for the pre-COVID period (from 18/03/2019 to 15/03/2020) for each building. The energy consumption was found to be clearly influenced by climatic conditions, particularly in winter. Therefore, heating degree days were used as a routine adjustment in the baseline equations. To calculate heating degree days, the heating base temperature (T heating base) or the outdoor temperature below which the building needs heating, which is the same thing, was set at 20 °C. Cooling degree days were discarded as an explanatory variable since few UPC buildings have cooling systems and in most cases only a few rooms are cooled. In addition, cooling systems typically only work two months a year (June and July). The number of students enrolled in the UPC schools was found to be very similar in the 2018/2019, 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 academic years (variation rate of 0.9% and 1.0%, respectively). Therefore, the number of registered students was not considered an adjustment factor in the assessment of the impact of the pandemic lockdown restrictions on UPC buildings’ energy consumption.

The baseline energy consumption model was determined by plotting the energy used for heating (or the best approximation to it) versus weekly heating degree days (Fig. 4 ). Regression analysis was used to determine the equation explaining the influence of heating degree days on the energy consumption. The statistical validity of the baseline model is determined by the coefficient of determination (R2), which should be higher than 0.75 [4]. In the case of gas-heated buildings, only gas consumption figures were weather-corrected with heating degree days. In this case, electricity consumption was not considered to be weather dependent. In the case of electricity-heated buildings, electricity consumption figures were weather-corrected with heating degree days, although this might have led to some inaccuracies because not all electricity consumption is weather dependent.

Fig. 4.

Baseline gas consumption model for the TR11 building (Terrassa Campus). Source: own elaboration.

In the second step of the methodology, weekly heating degree days were calculated for the lockdown period (from 16/03/2020 to 14/03/2021) and inserted into the baseline mathematical model to obtain the adjusted base energy consumption.

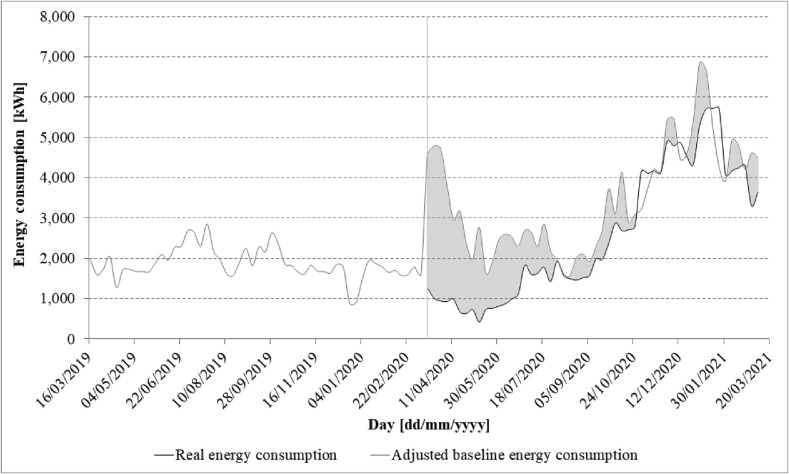

Thirdly, differences between the registered energy consumption (electricity and gas) during the post-COVID period and the adjusted baseline energy consumption were calculated on a weekly basis (Fig. 5 ) and the cumulative sum of differences was calculated and plotted (Fig. 6 ) for each building.

Fig. 5.

Adjusted baseline energy consumption and real energy consumption during the post-COVID-19 period for the TR11 building (Terrassa Campus). Source: own elaboration.

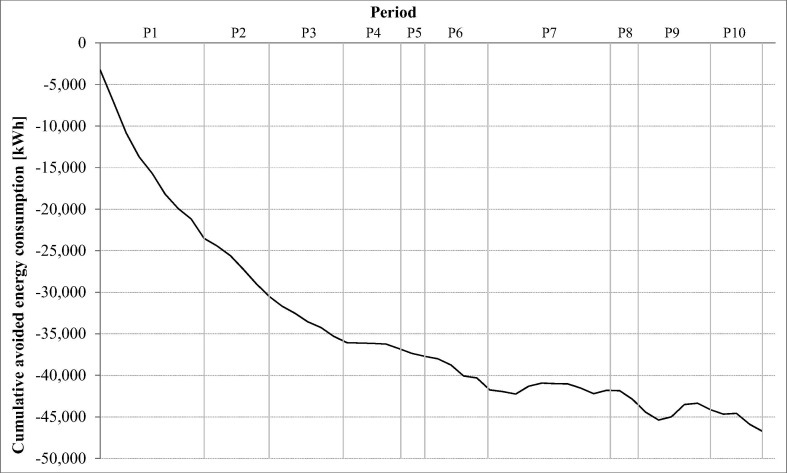

Fig. 6.

Cumulative avoided energy consumption during the post-COVID period for the TR11 building (Terrassa Campus). Source: own elaboration.

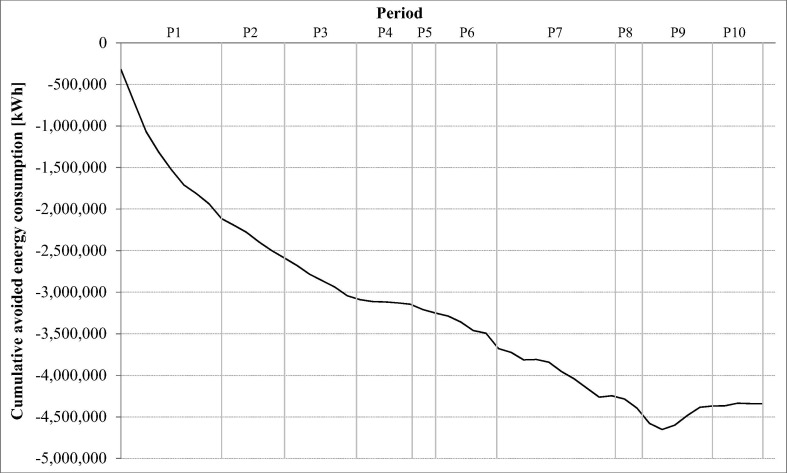

Figure 7 provides a general picture of the UPC buildings’ avoided energy consumption after the coronavirus outbreak. To the authors’ knowledge, no energy efficiency measures were implemented during the post-COVID period in the UPC buildings and no other significant factors have changed. Therefore, changes in the slope of the time series can be attributed to the impact of the levels of restrictions on the UPC buildings. The shift amounted to over 4.3 GWh in one year (from 16/03/2020 to 14/03/2021), representing a decrease in energy consumption of 19.3%. Similar outcomes were presented for the Griffith University, where the energy savings accounted for 16% of the total energy use [17].

Fig. 7.

Cumulative avoided energy consumption in all UPC buildings following the outbreak of COVID-19. Source: own elaboration.

As shown in Table 5 and according to the buildings’ typology, most of the avoided energy consumption took place in mixed-use buildings (41.19%), followed by office buildings (38.04%). Research buildings experienced the lowest proportion of avoided energy (1.51%). These results are along the lines of the results obtained by Chihib et al. [7] and Gui et al. [17].

Table 5.

Distribution of the avoided energy consumption by typology.

| Floor area (m2) | Avoided energy consumption |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| [kWh] | [%] | ||

| Teaching buildings | 16,907.36 | 128,372.57 | 2.96% |

| Research buildings | 8,014.42 | 65,814.65 | 1.51% |

| Office buildings | 128,629.28 | 1,651,698.46 | 38.04% |

| Libraries | 17,039.33 | 465,536.63 | 10.72% |

| Sports centres | 6,612.27 | 242,404.44 | 5.58% |

| Mixed-use buildings | 93,497.99 | 1,788,365.83 | 41.19% |

| Total | 270,700.65 | 4,342,192.58 | 100% |

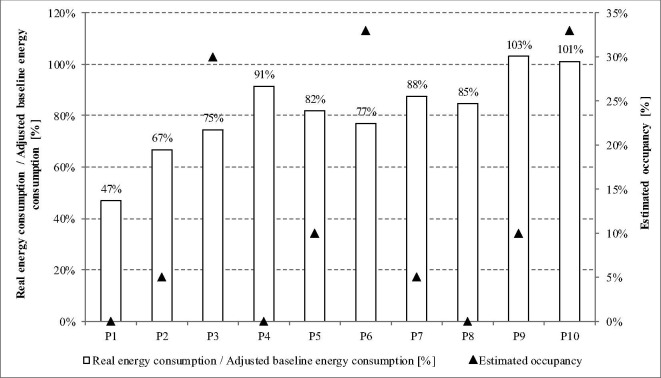

Figure 8 shows the percentage of energy actually consumed by all UPC buildings in relation to what they were expected to consume (or what is the same, in relation to the adjusted baseline energy consumption) for each of the identified periods after the COVID-19 outbreak. Initial lockdown periods experienced the largest decrease in energy consumption. Real energy consumption in period 1 (P1) accounted for 47% of the expected energy consumption according to the adjusted baseline, this period had the strictest lockdown measures. In period 2 (P2) and period 3 (P3), with less stringent measures, actual energy consumption increased, as did the occupancy of buildings, (67% and 75%, respectively). Period 4 (P4) and period 8 (P8) were holidays periods. During these periods there was a slight decrease in expected energy consumption. In period 5 (P5) and period 6 (P6), real energy consumption increased to 82% and 77% of the adjusted baseline energy consumption, respectively. In period 7 (P7), although occupancy of buildings decreased due to new restricting measures, actual energy consumption increased compared to previous periods. However, the increase in energy consumption became more evident during period 9 (P9) and period 10 (P10).

Fig. 8.

Relation between real energy consumption and adjusted baseline energy consumption, and estimated occupancy in all UPC buildings following the outbreak of COVID-19. Source: own elaboration.

4.2. Impact on energy performance indicators

For a more detailed analysis, energy performance indicators (Equation (4)) were calculated for the identified lockdown periods and compared to data from 2019 using the variation rate (Equation (5)). In this case, the most meaningful energy performance indicators were found to be the average weather-corrected daily energy consumption (Et/N·HDD), expressed in kWh/°C·day and the average weather-corrected daily energy consumption per square meter (Et/N·HDD·S), expressed in kWh/ °C·day·m2.

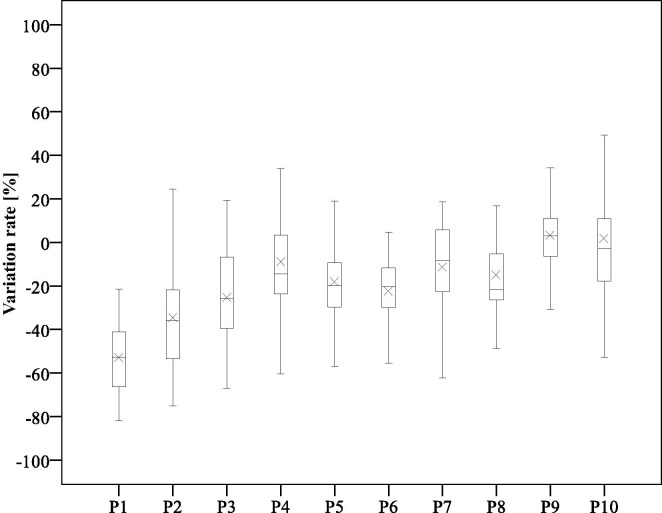

The results were summarised statistically using IBM SPSS Statistics package 21 [19]. Fig. 9 shows the time evolution of the impact of the lockdown on the energy consumption of UPC buildings. It can be concluded that differences in the energy consumption were strongly correlated to changes in restriction levels.

Fig. 9.

Boxplots of variations in weather-corrected energy consumption in 2020 in relation to 2019 for all UPC buildings per period. Source: own elaboration.

During period number 0 (P0 from 10/02/2020 to 15/03/2020), buildings were operating normally and therefore no significant changes were detected.

Major differences (53.1%) were observed during the first period (P1 from 16/03/2020 to 17/05/2020), with the toughest restrictions. However, one could expect a bigger energy reduction. In other words, energy reduction did not to coincide with the buildings’ occupancy drop. This lack of correlation between the occupancy rate and energy consumption was also detected by Chihib et al. [7]. During the days of the strict lockdown, UPC buildings were completely shut down and the activity in them completely ceased. Lecturers, researchers and students stayed at home and attempted to perform their usual routines in their home offices. Computers, laptops and other office-related appliances were plugged in at home instead of in lecturers’ offices, labs and classrooms. Lighting and space conditioning energy was also shifted from academic buildings to households. In spite of all the above, the results demonstrate that empty buildings still consumed a significant amount of energy. This might have a range of explanations including (i) buildings have a low level of centralised controls, (ii) building systems continue to operate automatically without modifications, (iii) buildings host data servers that must run in the same conditions or (iv) work computers remain on because this is thought to be needed for remote desktop connection. At regional level, Kang et al. [18] observed that in stronger social distancing, educational and research facilities had the highest decline in energy consumption.

Variation rates diminished when restriction measures were relaxed. In the second and third lockdown periods (P2 from 18/05/2020 to 21/06/2020, and P3 from 22/06/2020 to 31/07/2020), energy use rose but was still 33.2% and 25.5% below normal, respectively. Similarly, Chihib et al. [7] detected an increase in energy consumption in academic buildings during these periods compared to the previous period. The fourth period (P4 from 01/08/2020 to 31/08/2020) corresponded to the summer holidays and the results reveal a lower variation (8.6%) in the energy consumed in 2020 than in 2019. However, this indicates that buildings could be better managed in future summer breaks.

During the following periods, restrictions were eased and this translated into lower energy consumption variation rates. During the fifth period (P5 from 01/09/2020 to 13/09/2020), classes had not started and only professors and research and administrative staff were using the buildings. In this case, 18.2% less energy was consumed in 2020 than in 2019. Period 6 (P6 from 14/09/2020 to 18/10/2020) corresponded to the beginning of the first semester of the 2020/2021 academic year. Avoided energy consumption amounted to 23.0%, since face-to-face classes were restricted to first year students and lab sessions. Professors teaching theoretical contents on other courses were usually working at home. Kang et al. [18] also reported decreases in energy consumption caused by teleworking and e-learning. Due to the pandemic’s evolution, face-to face classes were suspended, except lab sessions and exams during the seventh period (P7 from 19/10/2020 to 22/12/2020). However, the avoided energy consumption was 12.4%. This variation rate increased to 15.3% during the winter holidays (P8 from 23/12/2020 to 06/01/2021).

Since then, UPC buildings have been found to consume more energy during lockdown than in the control year. This could be attributed to the recommendation of keeping doors and windows open to reduce the risk of coronavirus transmission, although heating systems are on. This effect was analysed by Mokhtari and Jahangir [25]. They found that by increasing the ventilation rate in academic buildings, the number of infected decreased considerably, but in contrast, energy consumption increased due to HVAC systems. During the ninth period (P9 from 07/01/2021 to 14/02/2021), as is usual at this time of year, buildings were only used for exams. In this case, energy use rose 3.0% above normal. The last period (P10 from 15/02/21 to 14/03/21) corresponds to the beginning of the second semester of the 2020/2021 academic course. Face-to-face classes were again restricted to first-year students and lab sessions. In this case, the variation rate was 1.1% above normal. Jiang et al. [21] noted that energy consumption of offices and schools/universities compared to home office due to teleworking and e-learning is interrelated. However, researchers highlighted that the increase or decrease in energy consumption is not changing equivalently between options. In this regard, further studies are needed taking into account users behavior and lifestyle changes. Moreover, O’brien and Aliabadi [27] pointed out that rebound effect of teleworking tends to compensate and even exceed energy savings significantly.

Table 6 summarizes the variation rates and corresponding standard deviations in weather-corrected energy consumption per square meter for each building typology and for each of the identified periods. In general, during the strict lockdown (P1), reductions in libraries (−74.22%) and teaching buildings (−68.10%) were higher than in mixed-use (−57.15%), research (−55.27%) and office buildings (−45.39%). In almost all cases, energy reductions lessened when restrictions were eased. This could be attributed to the process of resuming activities after the strict lockdown and to the guidelines that were promoted to ensure that buildings were safe during the COVID-19 pandemics, which mainly recommended keeping windows and doors open although this might have entailed higher energy consumption to maintain indoor thermal comfort. High standard deviations in the calculation of the variation rates are in line with those obtained by Chihib et al. [7]. These might be attributed to the fact that some buildings might have completely returned to normality while others were still partially closed one year after the coronavirus outbreak. It can be observed that returning from winter holidays (P9 and P10), most of academic building typologies, except libraries and sport centres, experienced an increase in energy consumption. This could indicate a possible rebound effect, as pointed out by O’brien and Aliabadi [27] and Jiang et al. [21].

Table 6.

Variation rates (%) in weather-corrected energy consumption per square meter in 2020 in relation to 2019 according to building typologies.

| Period | Teaching buildings |

Research buildings |

Office buildings |

Libraries |

Sport centre |

Mixed-use buildings |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variation [%] | Standard deviation | Variation [%] | Standard deviation | Variation [%] | Standard deviation | Variation [%] | Standard deviation | Variation [%] | Standard deviation | Variation [%] | Standard deviation | |

| 1 | −68.10 | 12.85 | −55.27 | 8.24 | −45.39 | 17.39 | −74.22 | 7.27 | −46.02 | – | −57.15 | 7.39 |

| 2 | −43.89 | 24.47 | −27.40 | 9.10 | −30.89 | 27.75 | −16.76 | 45.52 | −53.21 | – | −42.61 | 15.62 |

| 3 | –23.21 | 29.38 | –23.23 | 12.92 | −24.94 | 23.38 | 17.58 | 62.26 | −40.41 | – | −21.85 | 21.99 |

| 4 | −20.59 | 28.49 | −2.06 | 18.24 | −5.95 | 20.64 | −2.96 | 125.01 | −7.52 | – | −14.27 | 19.18 |

| 5 | −25.49 | 23.54 | –23.85 | 11.50 | −20.70 | 14.49 | 49.34 | 81.76 | −25.54 | – | −17.35 | 23.10 |

| 6 | −26.88 | 17.61 | −17.99 | 6.72 | −20.11 | 9.78 | 28.49 | 50.03 | −20.41 | – | −20.31 | 37.92 |

| 7 | −16.15 | 33.78 | 8.55 | 3.97 | −6.97 | 15.14 | −27.33 | 16.37 | −53.02 | – | −14.25 | 19.30 |

| 8 | −19.67 | 37.92 | −10.50 | 16.36 | −14.43 | 18.24 | −45.59 | 19.52 | −29.16 | – | −18.49 | 13.96 |

| 9 | 22.78 | 51.90 | 9.97 | 9.52 | 4.02 | 18.05 | −9.47 | 13.52 | −69.93 | – | 1.08 | 22.79 |

| 10 | 35.90 | 38.05 | 14.04 | 24.24 | 0.29 | 20.29 | –22.31 | 17.88 | −52.95 | – | 2.11 | 28.63 |

4.3. Economic impact of the avoided energy consumption

The economic impact was estimated according to Equation (6) by considering the avoided electricity and gas consumption. Table 7 shows the obtained results by building typology and period. Estimated economic savings amounted to a total of €1,748,238.03, of which 95.2% corresponded to savings from electricity consumption and 4.8% from gas consumption. Periods with the highest estimated economic savings were period 3 (P3), period 1 (P1) and period 6 (P6), representing 30.7%, 23.6% and 13.9% of the total, respectively.

Table 7.

Economic impact of the avoided energy consumption according to building typologies.

| Period | Teaching buildings |

Research buildings |

Office buildings |

Libraries |

Sport centre |

Mixed-use buildings |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic savings[€] | Economic savings per square meter [€/m2] | Economic savings [€] | Economic savings per square meter [€/m2] | Economic savings[€] | Economic savings per square meter [€/m2] | Economic savings[€] | Economic savings per square meter [€/m2] | Economic savings [€] | Economic savings per square meter [€/m2] | Economic savings[€] | Economic savings per square meter [€/m2] | |

| 1 | 27,338.70 | 1.62 | 10,180.41 | 1.27 | 176,289.69 | 1.37 | 38,148.43 | 2.24 | 12,326.32 | 1.86 | 147,957.41 | 1.58 |

| 2 | 8,682.62 | 0.51 | 2,569.67 | 0.32 | 56,220.94 | 0.44 | 11,477.80 | 0.67 | 8,186.91 | 1.24 | 49,437.09 | 0.53 |

| 3 | 15,471.74 | 0.92 | 12,897.45 | 1.61 | 283,418.88 | 2.20 | 50,597.65 | 2.97 | 25,738.61 | 3.89 | 148,252.02 | 1.59 |

| 4 | 4,849.37 | 0.29 | 598.60 | 0.07 | 28,495.15 | 0.22 | 24,770.38 | 1.45 | −79.76 | −0.01 | 22,536.32 | 0.24 |

| 5 | 7,287.71 | 0.43 | 4,972.24 | 0.62 | 93,845.29 | 0.73 | −3,324.35 | −0.20 | 7,179.15 | 1.09 | 50,623.08 | 0.54 |

| 6 | 11,746.90 | 0.69 | 4,544.45 | 0.57 | 114,842.18 | 0.89 | 5,655.94 | 0.33 | 9,666.60 | 1.46 | 96,022.21 | 1.03 |

| 7 | 7,695.77 | 0.46 | −2,502.12 | −0.31 | 10,017.99 | 0.08 | 19,511.98 | 1.15 | 11,178.53 | 1.69 | 70,870.06 | 0.76 |

| 8 | 3,972.25 | 0.23 | 1,709.99 | 0.21 | 20,749.59 | 0.16 | 7,789.87 | 0.46 | 1,987.78 | 0.30 | 30,816.87 | 0.33 |

| 9 | −20,074.57 | −1.19 | −1,666.79 | −0.21 | −18,934.11 | −0.15 | 9,883.27 | 0.58 | 13,417.29 | 2.03 | 4,983.76 | 0.05 |

| 10 | −15,209.89 | −0.90 | −459.48 | −0.06 | −5,479.39 | −0.04 | 9,836.35 | 0.58 | 6,489.62 | 0.98 | 12,229.61 | 0.13 |

| Total | 51,760.62 | 3.06 | 32,844.42 | 4.10 | 759,466.21 | 5.90 | 174,347.32 | 10.23 | 96,091.03 | 14.53 | 633,728.43 | 6.78 |

According to the buildings’ typology, office buildings obtained the greatest proportion of estimated economic savings (43.4%), followed by mixed-use buildings (36.2%). These results are conditioned by the representativeness of each type of building within the analysed sample, as office buildings and mixed-use buildings are the types of buildings with the largest floor area. Results changed when the analysis of estimated economic savings was conducted per square meter. Sports centre (€14.53/m2) and libraries (€10.23/m2) were the buildings’ typology with the greatest estimated economic savings per square meter throughout the year, followed by mixed-use buildings (€6.78/m2).

5. Conclusions

This paper assessed the effect of the pandemic lockdown on energy consumption in academic buildings. Data analysis compared the lockdown periods with the immediately preceding year, considering the year-on-year meteorological variation and changes in students’ enrolment. The methodology was applied to 83 academic buildings based on Barcelona (Spain). Buildings were classified according to their main use as teaching buildings, research buildings, office buildings, libraries, sport centres and mixed-use buildings. Moreover, ten periods of analysis were identified considering different levels of lockdown restrictions. The following conclusions can be outlined:

-

•

The results showed that UPC buildings’ weather-corrected energy consumption fell by 19.3% during the post-pandemic year or, in other words, avoided energy consumption amounted to over 4.3 GWh, representing an estimated economic saving of €1,748,238.03. The substantial decrease of energy consumption in academic buildings might be obvious but the novelty is that the energy consumption of academic buildings did not drop proportionally according to the buildings’ occupancy. For example, UPC buildings were completely empty between 16/03/2020 and 17/05/2020 (P1, full lockdown), but the energy consumption in classrooms, offices and laboratories dipped only 53.1%. During the reopening period (P2 between 18/05/2020 and 21/06/2020), results showed that academic buildings decreased their consumption around 33.2%.

-

•

A data-based comparison of energy consumption before and during the strict lockdown (P1) revealed that the variations in energy consumption were higher in libraries (−74.2%), followed by teaching buildings (−68.1%) and mixed-use buildings (−57.15%). In contrast, the comparison for period 9 (P9), when buildings were only used for examinations, and period 10 (P10), when the second semester of the 2020/2021 academic course began, showed that UPC buildings were found to consume more energy during the lockdown than during the control year (3.0% and 1.1%, respectively).

One of the strengths of this study is that the analysed period covers a full year, including the four seasons, with different levels of lockdown restrictions. The methodology could be extrapolated to other geographic areas since differences in lockdown restriction levels and climatic conditions are considered. This research was conducted on academic buildings but the methodology could also be extended to other tertiary-sector buildings such as offices and hotels.

The results might be useful to minimize energy consumption in vacant tertiary-sector buildings and forecast demand in case of future pandemic situations. However, this retrospective analysis also allows the identification of potential energy saving opportunities when buildings operate normally.

Further research is needed to assess the energy consumed as a consequence of increased digitalisation. This acquires even more importance as the transition towards telework and telelearning has been clearly boosted by the COVID-19 pandemic but it is also a trend that many expect to last.

More in-depth analysis and understanding is required to estimate the energy consumed to avoid future spread of infectious diseases in operating buildings as a consequence, for example, of stricter ventilation requirements. Increasing ventilation rates might increase heating and cooling loads, especially in extremely hot or cold seasons. If the existing buildings’ capacity is limited, temporary solutions might be adopted including space heaters and portable air filtration systems. In some cases, budget restrictions for system upgrades may make temporary solutions permanent.

On another level, and although teleworking has been widely perceived as a more sustainable mode of working or studying compared to the status quo of commuting to centralised buildings [27], the situation is far more complex when the scope is expanded to include home office energy use.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the R&D project IAQ4EDU, reference no. PID2020-117366RB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the Catalan Agency AGAUR under their research group support programme (2017SGR00227). The Infrastructures Service of the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya – Barcelona Tech is gratefully acknowledged for allowing access to UPC buildings’ energy consumption data.

References

- 1.Abdeen A., Kharvari F., O’Brien W., Gunay B. The impact of the COVID-19 on households’ hourly electricity consumption in Canada. Energy Build. 2021;250 doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.111280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abu-Rayash A., Dincer I. Analysis of the electricity demand trends amidst the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Energy Res. Social Sci. 2020;68 doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abulibdeh A. Modeling electricity consumption patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic across six socioeconomic sectors in the State of Qatar. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australasian Energy Performance Contracting Association, 2004. A Best Practice Guide to Measurement and Verification of Energy Savings. Available at: <http://icaen.gencat.cat/web/.content/01_estalvi_i_eficiencia_energetica/ambits/industria/documents/arxius/a_best_practice_guide_to_mmeasurement_and_verification_of_energy_savings.pdf>. Accessed on 29/07/2021.

- 5.Bielecki S., Skoczkowski T., Sobczak L., Buchoski J., Maciąg Ł., Dukat P. Impact of the Lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic on electricity use by residential users. Energies. 2021;14:980. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catalan Government, 2021. COVID Data. Available at: <https://dadescovid.cat/descarregues?lang=eng>. Accessed on: 20/11/2021.

- 7.Chihib M., Salmerón-Manzano E., Chourak M., Perea-Moreno A.J., Manzano-Agugliaro F. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the energy use at the university of almeria (Spain) Sustainability. 2021;13(11) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortiços N.D., Duarte C.C. COVID-19: the impact in US high-rise office buildings energy efficiency. Energy Build. 2021;249 doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.111180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cvetković D., Nešović A., Terzić I. Impact of people’s behavior on the energy sustainability of the residential sector in emergency situations caused by COVID-19. Energy Build. 2021;230 doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.F. de Frutos, T. Cuerdo-Vilches, C. Alonso, F. Martín-Consuegra, B. Frutos, I. Oteiza, M.Á. Navas-Martín. 2021. Indoor environmental quality and consumption patterns before and during the COVID-19 lockdown in twelve social dwellings in Madrid, Spain. Sustainability 13 7700.

- 11.Ding Y., Ivanko D., Cao G., Brattebø H., Nord N. Analysis of electricity use and economic impacts for buildings with electric heating under lockdown conditions: examples for educational buildings and residential buildings in Norway. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021;74 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Efficiency Valuation Organisation, 2016. EVO 10000-1:2016. Core concepts. International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol. Available at: <https://evo-world.org/en/library/download-protocol-documents-mainmenu-en/ipmvp-core-concepts>. Accessed on 20/04/2021.

- 13.Efficiency Valuation Organization, 2021. Impacts of COVID-19 on Measurement and Verification (M&V) of Energy Savings. Available at: <https://evo-world.org/images/corporate_documents/COVID-19_in_MV_Final_20210407.pdf>. Accessed on 20/04/2021.

- 14.Faulkner C.A., Castellini J.E., Zuo W., Lorenzetti D.M., Sohn M.D. Investigation of HVAC operation strategies for office buildings during COVID-19 pandemic. Build. Environ. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García S., Parejo A., Personal E., Guerrero J.I., Biscarri F., León C. A retrospective analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 restrictions on energy consumption at a disaggregated level. Appl. Energy. 2021;287 doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.116547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.M.S. Geraldi, M.V. Bavaresco, M.A. Triana, A.P. Melo, R. Lamberts. 2021. Addressing the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on energy use in municipal buildings: a case study in Florianópolis, Brazil. Sustain. Cities Soc. 102823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Gui X., Gou Z., Zhang F., Yu R. The impact of COVID-19 on higher education building energy use and implications for future education building energy studies. Energy Build. 2021;251 doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.111346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang H., An J., Kim H., Ji C., Hong T., Lee S. Changes in energy consumption according to building use type under COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021;148 doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.111294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibm . IBM Corp; Armonk, NY: 2021. IBM SPSS Statistics 21. [Google Scholar]

- 20.InfoMet, 2021. Terrassa - Centre. Available at: <http://infomet.am.ub.es/clima/terrassa/>. Accessed on: 15/06/2021.

- 21.Jiang P., Fan Y.V., Klemeš J.J. Impacts of COVID-19 on energy demand and consumption: challenges, lessons and emerging opportunities. Appl. Energy. 2021;285 doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.116441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanda W., Kivimaa P. What opportunities could the COVID-19 outbreak offer for sustainability transitions research on electricity and mobility? Energy Res. Social Sci. 2020;68 doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawka E., Cetin K. Impacts of COVID-19 on residential building energy use and performance. Build. Environ. 2021;205 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krarti M., Aldubyan M. Review analysis of COVID-19 impact on electricity demand for residential buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021;143 doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.110888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mokhtari R., Jahangir M.H. The effect of occupant distribution on energy consumption and COVID-19 infection in buildings: a case study of university building. Build. Environ. 2021;190 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.N. Norouzi, G. Zarazua de Rubens, S. Choupanpiesheh, P. Enevoldsen. 2020. When pandemics impact economies and climate change: exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on oil and electricity demand in China. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 68, 101654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.O'Brien W., Aliabadi F.Y. Does telecommuting save energy? A critical review of quantitative studies and their research methods. Energy Build. 2020;225 doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rouleau J., Gosselin L. Impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown on energy consumption in a Canadian social housing building. Appl. Energy. 2021;287 doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.116565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samuels J.A., Grobbelaar S.S., Booysen M.J. Pandemic and bills: the impact of COVID-19 on energy usage of schools in South Africa. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021;65:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santiago I., Moreno-Munoz A., Quintero-Jiménez P., Garcia-Torres F., Gonzalez-Redondo M.J. Electricity demand during pandemic times: the case of the COVID-19 in Spain. Energy Policy. 2021;148 doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Servei Meteorològic de Catalunya, 2021. Dades de l'estació automàtica Barcelona - Zona Universitària. Available at: <https://www.meteo.cat/observacions/xema/dades?codi=X8>. Accessed on: 12/06/2021.

- 32.Smith L.V., Tarui N., Yamagata T. Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on global fossil fuel consumption and CO2 emissions. Energy Econ. 2021;97 doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spain, 2006. Royal Decree 314/2006, 17 March, approving the Technical Building Code. Available at: <http://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2006/03/28/pdfs/A11816-11831.pdf>. Accessed on 01/04/2021.

- 34.Sovacool B.K., Furszyfer Del Rio D., Griffiths S. Contextualizing the Covid-19 pandemic for a carbon-constrained world: Insights for sustainability transitions, energy justice, and research methodology. Energy Res. Social Sci. 2020;68 doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.United Nations, 2020. Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. Available at: <https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf>. Accessed on 08/04/2021.

- 36.UPC, 2021a. Dades estadístiques i de gestió. Relació de les superfícies construïdes per la UPC. Available at: <https://gpaq.upc.edu/lldades/indicador.asp?index=4_1_3>. Accessed on 25/03/2021.

- 37.UPC, 2021b. Dades estadístiques i de gestió. Principals indicadors. Available at: <https://gpaq.upc.edu/lldades>. Accessed on 25/03/2021.

- 38.UPC, 2021c. Sirena. Available at: <https://sirenaupc.app.dexma.com/>. Accessed on 25/03/2021.

- 39.Zhang X., Pellegrino F., Shen J., Copertaro B., Huang P., Kumar S.P., Lovati M. A preliminary simulation study about the impact of COVID-19 crisis on energy demand of a building mix at a district in Sweden. Appl. Energy. 2020;280 doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L., Li H., Lee W.J., Liao H. COVID-19 and energy: Influence mechanisms and research methodologies. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021;27:2134–2152. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2021.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang D., Li H., Zhu H., Zhang H., Goh H.H., Wong M.C., Wu T. Impact of COVID-19 on urban energy consumption of commercial Tourism City. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021;73 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.103133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]