Abstract

Purpose:

To determine classification criteria for acute retinal necrosis (ARN).

Design:

Machine learning of cases with ARN and 4 other infectious posterior/ panuveitides.

Methods:

Cases of infectious posterior/panuveitides were collected in an informatics-designed preliminary database, and a final database was constructed of cases achieving supermajority agreement on diagnosis, using formal consensus techniques. Cases were split into a training set and a validation set. Machine learning using multinomial logistic regression was used on the training set to determine a parsimonious set of criteria that minimized the misclassification rate among the infectious posterior/panuveitides. The resulting criteria were evaluated on the validation set.

Results:

Eight hundred three cases of infectious posterior/panuveitides, including 186 cases of ARN, were evaluated by machine learning. Key criteria for ARN included: 1) peripheral necrotizing retinitis; and either 2) polymerase chain reaction assay of an intraocular fluid specimen positive for either herpes simplex virus or varicella zoster virus; or 3) a characteristic clinical appearance with circumferential or confluent retinitis, retinal vascular sheathing and/or occlusion, and more than minimal vitritis. Overall accuracy for infectious posterior/panuveitides was 92.1% in the training set and 93.3% (95% confidence interval 88.2, 96.3) in the validation set. The misclassification rates for ARN were 15% in the training set and 11.5% in the validation set.

Conclusions:

The criteria for ARN had a reasonably low misclassification rate and appeared to perform sufficiently well for use in clinical and translational research.

PRECIS

Using a formalized approach to developing classification criteria, including informatics-based case collection, consensus-technique-based case selection, and machine learning, classification criteria for the acute retinal necrosis were developed. Key criteria included peripheral necrotizing retinitis and either PCR evidence of intraocular infection with herpes simplex or varicella zoster virus or characteristic clinical picture with circumferential or confluent retinitis, retinal vascular sheathing and/or occlusion, and vitritis. The resulting classification criteria had a reasonably low misclassification rate.

The first published use of the term acute retinal necrosis (ARN) was by Young and Bird in 1978,1 to describe the clinical findings of four patients with the sudden onset of a bilateral, symmetrical, and rapidly progressive retinal necrosis. In the course of their disease all four patients also were described as having aqueous and vitreous inflammatory cells and retinal vascular occlusion. Young and Bird noted similarities between their four patients and patients with herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV) retinitis, as well as with two prior cases of necrotizing retinitis and retinal vascular occlusion of unknown cause described by Willerson et al.2 There also was a striking clinical similarity between the patients described by Young and Bird and six patients described in the Japanese literature by Urayama et al3 and a single case report of a patient with herpes zoster ophthalmicus complicated by panuveitis and retinal arteritis described by Brown and Mendis.4 Despite originally being described as a bilateral disease, it subsequently became evident that the majority of ARN cases were unilateral.5

Although herpesviruses were suspected causes of the ARN syndrome since its original descriptions,6 the first immunolocalization of a herpesvirus antigen in the eyes of patients with the ARN syndrome was reported by Peyman et al in 1984.7 In 1986 Culbertson et al8 provided ultrastructural, immunohistochemical and viral culture evidence of VZV as a cause of the ARN syndrome. Numerous subsequent reports support HSV type 1 (HSV-1), HSV type 2 (HSV-2) and VZV as pathological causes of ARN.9–13 Although some authors suggested that ocular infections with cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus also may produce the characteristic findings of the ARN syndrome, the data to support these assertions have not been robust. Cases series have consistently reported that the viral cause of ARN segregates by age. HSV-2 is present in youngest group (mean age early third decade of life); HSV-1 next youngest (mean age late third decade to early 4th decade); and VZV the oldest (mean age sixth decade of life).9–16

The ARN syndrome is rare. In a prospective population-based surveillance study in the United Kingdom, 45 confirmed cases of ARN were reported in a 14-month study period, resulting in an estimated incidence of 0.63 cases per million population per year,16 an estimate which was very similar to results previously published on the incidence of ARN in the United Kingdom five years earlier (0.50 cases per million population).17

Of note, eight patients captured in the United Kingdom 2012 surveillance study were recognized as having either a preceding or concurrent central nervous system herpetic disease.14 Several case series and case reports similarly have reported an association between ARN and prior, subsequent and or concurrent viral meningitis or encephalitis, particularly among younger patients with HSV-1 or HSV-2 ARN.10,18,19 Given the low incidence of ARN, the high prevalence of latent HSV and VZV infection, and the data the linking herpesvirus encephalitis or meningitis with selective defects in viral immunity,20–22 it is possible that there may be genetic risk factors in the immune response for the ARN syndrome, although there are as yet limited data to support this inference.23

Because ARN is a rare disease, the data on treatment are of limited quality, largely coming from case series. Nevertheless, because of the viral etiology, rapid progression, and poor prognosis, there is a consensus that prompt treatment with antiviral agents is needed. In early reports patients were treated with intravenous acyclovir at a dose of 500 mg/m2 every 8 hours (~850 mg every 8 hours in an average adult).24 Subsequent studies have used oral valacyclovir, typically at a dose of 2 gm TID-QID,25–,28 and one case series suggested similar results between oral valacyclovir plus intravitreal foscarnet and intravenous acyclovir.26 Given that systemically-administered drugs need five half-lives to achieve steady state and the rapid progression of the disease, initial therapy with intravitreal antiviral agents (e.g. foscarnet) in order to achieve high intraocular drug levels appears appropriate.25,28 Systemic therapy appears to decrease the risk of second eye involvement.25 Although the optimal duration of oral therapy is uncertain, the high risk period for second eye involvement is the first 14 weeks after presentation,25 and many experts suggest treating with lower dose maintenance therapy for at least 6 months. Retinal detachment is a frequent sequelae of ARN occurring in up to 85% of eyes.5,23–28 Its frequency does not appear to be decreased by systemic antiviral therapy, perhaps due to the extensive amount of retinal necrosis at presentation, but one retrospective case series suggested that it may be decreased by the early use of adjunctive intravitreal foscarnet5,26,28 Because of the poor visual outcomes in eyes with ARN (~50% 20/200 or worse at 6 months after presentation),28 prevention of second eye involvement is an important goal of therapy.

The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group is an international collaboration, which has developing classification criteria for 25 of the most common uveitides using a formal approach to development and classification. Among the diseases studied was ARN.29–35

Methods

The SUN Developing Classification Criteria for the Uveitides project proceeded in four phases as previously described: 1) informatics, 2) case collection, 3) case selection, and 4) machine learning.30–34

Informatics.

As previously described, the consensus-based informatics phase permitted the development of a standardized vocabulary and the development of a standardized, menu-driven hierarchical case collection instrument.31

Case collection and case selection.

De-identified information was entered into the SUN preliminary database by the 76 contributing investigators for each disease as previously described.32,33 Cases in the preliminary database were reviewed by committees of 9 investigators for selection into the final database, using formal consensus techniques described in the accompanying article.33,34 Because the goal was to develop classification criteria,35 only cases with a supermajority agreement (>75%) that the case was the disease in question were retained in the final database (i.e. were “selected”).33,34

Machine learning.

The final database then was randomly separated into a training set (~85% of the cases) and a validation set (~15% of the cases) for each disease as described in the accompanying article.34 Machine learning was used on the training set to determine criteria that minimized misclassification. The criteria then were tested on the validation set; for both the training set and the validation set, the misclassification rate was calculated for each disease. The misclassification rate was the proportion of cases classified incorrectly by the machine learning algorithm when compared to the consensus diagnosis. For infectious posterior and panuveitides, the diseases against which ARN was evaluated were: CMV retinitis, syphilitic uveitis, tubercular uveitis, and toxoplasmic retinitis.

The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at each participating center reviewed and approved the study; the study typically was considered either minimal risk or exempt by the individual IRBs.

Results

Two hundred fifty-two cases of ARN were collected and 186 (74%) achieved supermajority agreement on the diagnosis during the “selection” phase and were used in the machine learning phase. These cases of ARN were compared to cases of infectious posterior/panuveitides, including 211 cases of CMV retinitis, 174 cases of toxoplasmic retinitis, 35 cases of syphilitic posterior uveitis and 197 cases of tubercular uveitis. The details of the machine learning results for these diseases are outlined in the accompanying article.32 The characteristics of cases with acute retinal necrosis are listed in Table 1, and the classification criteria developed after machine learning are listed in Table 2. In all of the cases the retinitis involved the peripheral retina, though in 18% it had extended into the posterior pole. Key features of the criteria include a peripheral necrotizing retinitis and either confirmation of HSV or VZV infection on PCR of an intraocular fluid specimen or the characteristic clinical picture (Figure 1). The characteristic clinical picture includes: 1) either circumferential or confluent retinitis, and 2) retinal vascular inflammation (sheathing, leakage, and/or occlusion), and 3) greater than minimal vitritis, unless the patient is immune compromised. The overall accuracy for infectious posterior/panuveitides was 92.1% in the training set and 93.3% (95% confidence interval 88.2, 96.3%) in the validation set. The misclassification rate for acute retinal necrosis in the training set was 15% and, in the validation set, 11.5%. In both the training set and the validation set, the diseases with which it was most often confused were CMV retinitis and ocular toxoplasmosis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cases with Acute Retinal Necrosis

| Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|

| Number cases | 186 |

| Demographics | |

| Age, median, years (25th 75th percentile) | 50 (33, 63) |

| Gender (%) | |

| Men | 55 |

| Women | 45 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 61 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 10 |

| Hispanic | 2 |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 15 |

| Other | 5 |

| Missing | 7 |

| Uveitis History | |

| Uveitis course (%) | |

| Acute, monophasic | 67 |

| Acute, recurrent | 4 |

| Chronic | 18 |

| Indeterminate | 11 |

| Laterality (%) | |

| Unilateral | 87 |

| Unilateral, alternating | 0 |

| Bilateral | 13 |

| Ophthalmic examination | |

| Keratic precipitates (%) | |

| None | 19 |

| Fine | 27 |

| Round | 18 |

| Stellate | 6 |

| Mutton Fat | 29 |

| Other | 1 |

| Anterior chamber cells (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 6 |

| 1/2+ | 9 |

| 1+ | 23 |

| 2+ | 27 |

| 3+ | 22 |

| 4+ | 12 |

| Anterior chamber flare (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 29 |

| 1+ | 32 |

| 2+ | 29 |

| 3+ | 9 |

| 4+ | 2 |

| Iris (%) | |

| Normal | 91 |

| Posterior synechiae | 6 |

| Iris nodules | 3 |

| Iris atrophy (sectoral, patchy, or diffuse) | 0 |

| Heterochromia | 0 |

| Intraocular pressure (IOP), involved eyes | |

| Median, mm Hg (25th, 75th percentile) | 15 (12, 19) |

| Proportion patients with IOP>24 mm Hg either eye (%) | 6 |

| Vitreous cells (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 7 |

| 1/2+ | 4 |

| 1+ | 31 |

| 2+ | 30 |

| 3+ | 21 |

| 4+ | 7 |

| Vitreous haze (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 20 |

| 1/2+ | 11 |

| 1+ | 19 |

| 2+ | 31 |

| 3+ | 16 |

| 4+ | 4 |

| Retinitis characteristics | |

| Number lesions (%) | |

| Unifocal (1) | 37 |

| Paucifocal (2 to 4) | 25 |

| Multifocal (≥5) | 36 |

| Lesion shape (%) | |

| Round or ovoid | 13 |

| Placoid | 24 |

| Wedge-shaped | 20 |

| Ameboid | 14 |

| Not determined | 28 |

| Lesion character (%) | |

| Circumferential | 30 |

| Confluent | 49 |

| Granular | 4 |

| Lesion location (%) | |

| Posterior pole and periphery involved | 18 |

| Mid-periphery and/or periphery only | 82 |

| Lesion size (%) | |

| <250 μm | 8 |

| 250–500 μm | 15 |

| >500 μm | 77 |

| Other features (%) | |

| Retinal vascular sheathing or leakage or occlusion | 54 |

| Hemorrhage | 38 |

| Systemic disease | |

| Immunocompromised patients (%) | 15 |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection | 3 |

| Organ transplant | 0 |

| Chemotherapy or other immunosuppression | 12 |

| Laboratory data (%) | |

| Aqueous or vitreous specimen PCR* positive for HSV | 29 |

| Aqueous or vitreous specimen PCR* positive for VZV | 53 |

PCR = polymerase chain reaction. HSV = herpes simplex virus; 54 of 153 tested (35%) were positive. VZV = varicella zoster virus; 101 of 153 tested (66%) were positive. Two cases were positive for both viruses.

Table 2.

Classification Criteria for Acute Retinal Necrosis

| Criteria |

| 1. Necrotizing retinitis involving the peripheral retina |

| AND (either #2 OR #3) |

| 2. Evidence of infection with either herpes simplex virus (HSV) or Varicella zoster virus (VZV) |

| a. Positive PCR* for either HSV or VZV from either an aqueous or vitreous specimen |

| OR |

| 3. Characteristic clinical picture |

| a. Circumferential or confluent retinitis AND |

| b. Retinal vascular sheathing and/or occlusion AND |

| c. More than minimal vitritis † |

| Exclusions |

| 1. Positive serology for syphilis using a treponemal test |

| 2. Intraocular specimen PCR-positive for cytomegalovirus or Toxoplasma gondii (unless there is immune compromise, morphologic evidence for >1 infection, the characteristic clinical picture of acute retinal necrosis, and the intraocular fluid specimen has a positive PCR for either HSV or VZV) |

PCR = polymerase chain reaction. HSV = herpes simplex virus. VZV = varicella zoster virus.

Vitritis criterion not required in immunocompromised patients.

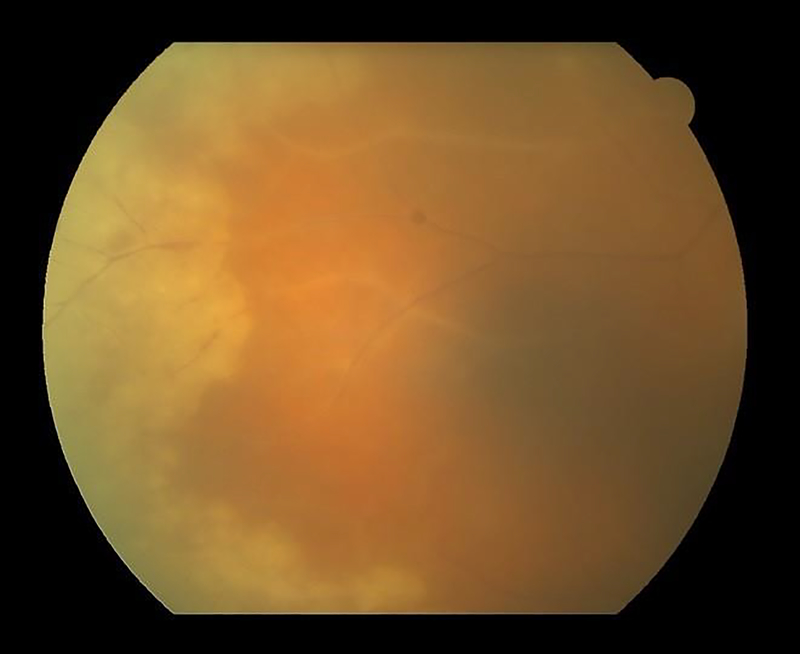

Figure 1.

Fundus photograph of a case of acute retinal necrosis with confluent, circumferential peripheral retinitis and vascular sheathing.

Discussion

The ARN syndrome is a necrotizing retinitis that involves the peripheral retina. Necrotizing retinitides are characterized by full thickness retinal necrosis with or without inflammation, which, upon resolution, leave an atrophic and gliotic scar in the involved areas. Clinically, the initial presentation is white to yellow retinal edema and opacity with or without hemorrhage. Necrotizing retinitides may have relatively well demarcated borders, as in the case of ARN (Figure 1), or have satellites extending into adjacent retina, as is seen in CMV retinitis. The classification criteria developed by the SUN Working Group for ARN have a relatively low misclassification rate, indicating reasonable discriminatory performance against other infectious posterior and pan-uveitides. The SUN criteria require a peripheral necrotizing retinitis and either 1) confirmation of of intraocular infection with HSV or VZV (via PCR of an intraocular fluid) or 2) the classic clinical picture. The inclusion of both ways of classifying a case as ARN permits reporting of retrospective case series where intraocular fluid sampling may not have been performed in every (or even any) cases, and therefore will reduce potential bias if intraocular fluid sampling a a given center was reserved for those cases where the diagnosis was uncertain.

In 1994 the American Uveitis Society proposed standard diagnostic criteria for the ARN syndrome.36 These criteria included: 1) well demarcated areas of retinal necrosis in the peripheral retina; 2) rapid circumferential progression of retinal necrosis; 3) occlusive vasculopathy; and 4) a prominent inflammatory reaction in the anterior chamber and vitreous. The guidelines further noted that the definition of ARN did not depend on the immunological status of the host or the isolation of any specific pathogen from ocular tissues. Furthermore, if a causal agent was identified, then the retinitis should be referred to as being caused by the agent, with the designation of ARN as a modifier.36 The SUN classification criteria are similar in many respects to the proposed AUS criteria, except that rapid circumferential progression, which requires more than a single observation (and therefore cannot be used to diagnose ARN at the initial visit) was not included, and peripheral necrotizing retinitis with appropriate confirmation of the HSV or VZV viral etiology was included.

In 2015, the Japanese ARN Study Group proposed criteria for ARN with 2 levels of certainty: virus-confirmed and virus-unconfirmed. Both virus-confirmed and virus unconfirmed required anterior segment inflammation, yellow-white peripheral retinal lesions, and continued observation to determine course.37 Virus-confirmed required any one of the following: rapid circumferential expansion, development of retinal breaks or detachment, retinal vascular occlusion, development of optic atrophy, or response to antiviral therapy. Virus-unconfirmed required any two of the above plus any two additional clinical features, including: retinal arteritis, disc hyperemia, vitritis, elevated intraocular pressure.37 Like the AUS criteria, the Japanese criteria require observation at more than a single visit, and therefore cannot be used to diagnose ARN at the initial visit, whereas the SUN Criteria can be used at an initial visit.

Although originally described in patients without evident immune compromise, it subsequently was recognized that a morphologically similar syndrome occurs in immune compromised patients, although vitritis may not be present in these patients.38,39 As such, the AUS criteria allowed for patients without and with evident immune compromise (e.g. AIDS, cancer, transplant, chemotherapy) to be diagnosed as having ARN.36 The SUN Classification Criteria for ARN also allowed for patients with evident immune compromise to be diagnosed as having ARN, and indeed 15% of the cases in the database were immunocompromised.

The ARN syndrome is a morphologic syndrome, and there are other variants of herpetic retinitis, such as the progressive outer retinal necrosis syndrome.40–43 In contrast to the ARN syndrome, it is seen exclusively in immune compromised hosts, often with profound immune compromise, has early posterior pole involvement, and an initial appearance of inner retinal sparing. It tends to progress even more rapidly than ARN and responds poorly to single agent antiviral therapy with intravenous acyclovir.39 Successful management of HIV infection with modern antiretroviral therapy has substantially decreased the population at risk for progressive outer retinal necrosis, so that it now is seen rarely,43 and too few cases were collected for formal analysis in the SUN project. In addition, cases of a non-necrotizing herpetic retinitis, papillitis, or retinal vasculitis have been reported.44,45 These cases tend to present as corticosteroid-resistant posterior uveitis and have either HSV or VZV identified on PCR analysis of an intraocular fluid specimen. Given the absence of a peripheral necrotizing retinitis, these cases similarly would not be classified as the ARN syndrome. The term necrotizing herpetic retinopathy has been used by some experts to refer collectively to the group of infectious retinitides caused by herpes family viruses. Acute retinal necrosis is one of these diseases, and the SUN criteria address the individual diseases, not the entire group. The criteria for cytomegalovirus retinitis are presented in an accompanying article.46

Classification criteria are employed to diagnose individual diseases for research purposes.35 Classification criteria differ from clinical diagnostic criteria, in that although both seek to minimize misclassification, when a trade-off is needed, diagnostic criteria typically emphasize sensitivity, whereas classification criteria emphasize specificity,35 in order to define a homogeneous group of patients for inclusion in research studies and limit the inclusion of patients without the disease in question that might confound the data. The machine learning process employed did not explicitly use sensitivity and specificity; instead it minimized the misclassification rate. Because we were developing classification criteria and because the typical agreement between two uveitis experts on diagnosis is moderate at best,33 the selection of cases for the final database (“case selection”) included only cases which achieved supermajority agreement on the diagnosis. As such, some cases which clinicians would diagnose with ARN may not be so classified by classification criteria.

In conclusion, the criteria for ARN outlined in Table 2 appear to perform sufficiently well for use as classification criteria in clinical research.35

Grant support:

Supported by grant R01 EY026593 from the National Eye Institute, the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; the David Brown Fund, New York, NY, USA; the Jillian M. And Lawrence A. Neubauer Foundation, New York, NY, USA; and the New York Eye and Ear Foundation, New York, NY, USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Young NJA, Bird AC. Bilateral acute retinal necrosis. Br J Ophthalmol 1978;62:581–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willerson D, Aaberg TM, Reeser FH. Necrotizing vaso-occlusive retinitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1977;84:2014–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urayama A, Yamada N, Sasaki T, et al. Unilateral acute uveitis with retinal periarteritis, and detachment. Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol 1971;25:607–19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rm Brown, Mendis U. Retinal arteritis complicating herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Br J Ophthalmol 1973;57:344–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duker JS, Blumenkrantz MS. Diagnosis and management of the acute retinal necrosis (ARN) syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol 1991;35:327–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Culbertson WW, Blumenkrantz MS, Haines H, Gass DM, Mitchell KB, Norton EW. The acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Part 2: histopathology and etiology. Ophthalmology 1982;89:1317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peyman GA, Goldberg MF, Uninsky E, tessler H, Pulido J, Hendricks R. Vitrectomy and intravitreal antiviral drug therapy in acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102:1618–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culbertson WW, Blumenkrantz MS, Pepose JS, Stewart JA, Curtin VT. Varicella zoster virus is a cause of the acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Ophthalmology 1986;93:559–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis ML, Culbertson WW, post MJ, Miller D, Kokame GT, Dix RD. Herpes simplex virus type 1. A cause of the acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Ophthalmology 1989;96:875–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minoda H, Usui N, Goto H et al. ;. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method in the diagnosis of Kirisawa-Urayama type uveitis. Folia Ophthalmol Jpn 1992;433:1323–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishi M, Hanashiro R, Mori S, et al. ;. Polymerase chain reaction for the detection of Varicella-zoster genome in ocular samples form patients with acute retinal necrosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1992;114:603–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganatra JB, Chandler D, Santos C, Kupperman B, Margolis TP. Viral causes of acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;129:166–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Gelder RN, Willig JL, Holland GN, Kaplan HJ. Herpes simplex virus type 2 as a cause of the acute retinal necrosis syndrome in young patients. Ophthalmol 2001;108:869–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Boer H, Luyendijk L, Rothova A, et al. Detection of intraocular antibody production to herpesviruses in acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;117:201–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Usui Y, Takeuchi M, Goto H, et al. Acute retinal necrosis in Japan. Ophthalmol 2008;115:1632–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cochrane TF, Silvestri G, McDowell C, Foot B, McAvoy CE. Acute retinal necrosis in the United Kingdom: results of a prospective surveillance study. Eye 2012:26:370–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muthiah MN, Michaelides M, Child CS, Mitchell SN. Acute retinal necrosis: a national population-based study to assess the incidence, methods of diagnosis, treatment strategies and outcomes in the UK. Br. J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1452–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandercam T, Hintzen RG, de Boer JH, Van der Lelij A. Herpetic encephalitis is a risk factor for acute retinal necrosis. Neurology 2008;71:1268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Todokoro D, Kamel S, Goto H, Ikeda Y, Koyama H, Akiyama H. Acute retinal necrosis following herpes simplex encephalitis, a nationwide survey in Japan. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2019; ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casanova JL. Severe infectious diseases of childhood as monogenic inborn errors of immunity. Proc Nat Acad Sci 2015;112:E7128–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mogensen TH. IRF and STAT transcription factors from basic biology to roles in infection, protective immunity and primary immunodeficiencies. Front. Immunol 2019; January 8;9:3047. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter-Timofte J, Hansen AF, Christinasen M, Paludan SR, Mogensen TH. Mutations in RNA polymerase III genes and defective DNA sensing in adults with Varicella-zoster CNS infection. Genes and Immunity 2019;20:214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland GN, Cornell PH, Park MS, et al. An association between acute retinal necrosis syndrome and HLA-DQw7 and phenotype Bw62 DR4. Am J Ophthalmol 1989;108:370–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumenkranz MS, Culbertson WW, Clarkson JG, Dix R. Treatment of acute retinal necrosis wit intravenous acyclovir. Ophthalmology 1986;93:296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palay DA, Sternberg P Jr, Davis J, et al. Decrease in the risk of bilateral acute retinal necorisi by acyclovir therapy. Am J Ophthalmol 1991;112:250–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong R, Pavesio CE, Laidlaw DA, Williamson TH, Graham EM, Stanford MR. Acute retinal necrosis: the effects of intravitreal foscarnet and virus type on outcome. Ophthalmology 2010;117:556–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baltinas J, Lightman S, Tomkins-Netzer O. Comparing treatment of acute retinal necrosis with either oral valacyclovir or intravenous acyclovir. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;188:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoenberger SD, Kim SJ, Thorne JE, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute retinal necrosis: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2017;124:382–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Nussenblatt RB, the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Report of the first international workshop. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;140:509–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jabs DA, Busingye J. Approach to the diagnosis of the uveitides. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:228–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trusko B, Thorne J, Jabs D, et al. Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group. The SUN Project. Development of a clinical evidence base utilizing informatics tools and techniques. Methods Inf Med 2013;52:259–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okada AA, Jabs DA. The SUN Project. The future is here. Arch Ophthalmol 2013;131:787–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jabs DA, Dick A, Doucette JT, Gupta A, Lightman S, McCluskey P, Okada AA, Palestine AG, Rosenbaum JT, Saleem SM, Thorne J, Trusko, B for the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group. Interobserver agreement among uveitis experts on uveitic diagnoses: the Standard of Uveitis Nomenclature experience. Am J Ophthalmol 2018; 186:19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Development of classification criteria for the uveitides. Am J Ophthalmol 2020;volume:pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aggarwal R, Ringold S, Khanna D, et al. Distinctions between diagnostic and classification criteria. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:891–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holland GN, Executive Committee of the American Uveitis Society. Standard diagnostic criteria for the acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;117:663–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takase H, Okada AA, Goto H, et al. Development and validation of new diagnostic criteria for acute retinal necrosis. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2015;59:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jabs DA, Schachat AP, Liss R, Know DL, Michels RG. Presumed varicella zoster retinitis in immunocompromised patients. Retina 1987;7:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jabs DA. Ocular complications of HIV infection. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1995;93:623–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forster DJ, Dugel PU, Frangieh GT, Liggett PE, Rao NA. Rapidly progressive outer retinal necrosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1990;110:341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Margolis TP, Lowder CY, Holland GN, et al. Varicella-zoster virus retinitis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1991;112:119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Engstrom RE Jr., Holland GN, Margolis TP, et al. The progressive outer retinal necrosis syndrome. A variant of necrotizing herpetic retinopathy in patients with AIDS. Ophthalmology 1994;101:1488–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gangaputra S, Drye L, Vaidya V, Thorne JE, Jabs DA, Lyon AT for the Studies of the Ocular Complications of AIDS Research Group. Non-cytomegalovirus ocular opportunistic infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;155:206–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bodaghi B, Rozenberg F, Cassoux N, Fardeau C, Le Hoang P. Nonnecrotizing herpetic retinopathies masquerading as severe posterior uveitis. Ophthalmology 2003;110:1737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wensing B, de Groot-Mijnes JD, Rothova A. Necrotizing and non-necrotizing variants of herpetic uveitis with posterior segment involvement. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:403–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Classification criteria for cytomegalovirus retinitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2020;vol:pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]