Abstract

A recent case report of a child infected with enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) of serotype O118:H16 in Bavaria, in association with the isolation of a bovine O118 strain on the same farm (A. Weber, H. Klie, H. Richter, P. Gallien, M. Timm, and K. W. Perlberg, Berl. Muench. Tieraerztl. Wochenschr. 110:211–213, 1997), prompted us to investigate the relationship between bovine and human strains of serogroup O118. A total of 29 human O118 E. coli strains from Europe (21), Canada (4), and Peru (4) were compared by virulence typing and macrorestriction analysis with 7 bovine O118 EHEC strains isolated in Bavaria. Twenty-five of the human strains were characterized as EHEC. By serotyping and determination of the virulence-associated factors Shiga toxin (stx1 stx2 stx2 variants), intimin (eae), and EHEC hemolysin (HlyEHEC), three distinctive groups of O118 human pathogens were identified. Most of the strains belonged to serotype O118:H16, displaying the virulence traits Stx1, intimin, HlyEHEC, and EspP/PssA (group 1). In addition, we identified strains of serotype O118:H12 (Stx2d only; group 2) and of serotype O118:H30 (Stx2 and intimin; group 3). Macrorestriction analysis with BlnI and XbaI revealed that all strains with a single O118 serotype profile (O118:H12, O118:H16, and O118:H30) belonged to one clonal cluster, irrespective of their origin. Group 1 strains clustered in the same clonal group as the bovine O118:H16 strains. Moreover, four pairs of strains of different origins and indistinguishable by all other methods applied were identified as group 1 strains. Our data support the direct transmission of an EHEC O118:H16 strain from a calf to a 2-year-old boy in the above-mentioned case report. Since bovine and human O118:H16 strains represent the same clones, they must be considered zoonotic EHEC pathogens. In contrast, EHEC strains of serotypes O118:H12 and O118:H30 have been isolated only from humans, indicating a reservoir for certain human O118 EHEC strains other than bovines.

Cases of hemorrhagic colitis (HC) and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) are due to infections with enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC). While numerous outbreaks have been attributed to EHEC strains of serotype O157:H7, other serotypes also play an important role in human disease (1, 10). So far, the intestinal tract of ruminants is the only known reservoir of EHEC. In order to evaluate the potential health threat of ruminants for humans, it is mandatory to further explore the characteristics of EHEC strains circulating in cattle. It was recently shown that strains of serotype O118:H16 are the most prevalent EHEC in calves in Germany and Belgium and that these strains harbor virulence traits which make them indistinguishable from typical EHEC strains (33, 35). Strains of this serotype have previously been implicated in cases of HUS, HC, and diarrhea in humans (5, 25). A recent case report from Bavaria describing the isolation of an EHEC O118:H16 strain from a 2-year-old child with diarrhea and a calf with which the child had contact (31) prompted our detailed study of O118 EHEC strains reported here. As these pathogens have not been thoroughly or systematically characterized for virulence genes and clonality, we characterized 29 O118 E. coli strains from humans from different geographical locations and 7 bovine O118 EHEC strains from Bavaria by identification of the EHEC virulence-associated factors Shiga toxin (Stx), locus of enterocyte effacement, EHEC hemolysin (HlyEHEC), and the secreted protease EspP/PssA. We also analyzed the clonal relationship of the strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

The results presented in this study indicate that bovines are the reservoir of O118:H16 EHEC strains but not of serotypes O118:H12 and O118:H30. Our data provide further insight into the high genetic variability of E. coli strains, even within a single serogroup, and indicate that the role of bovines as the exclusive reservoir for all EHEC should be reconsidered.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Three E. coli O118 strains were isolated from three different diarrheic calves in Bavaria between 1989 and 1997 (33). Fecal specimens were cultured on the following types of agar: Gassner, sorbitol-MacConkey, BPLS (E. Merck AG, Darmstadt, Germany), and sheep blood (blood agar base supplemented with 10% [vol/vol] defibrinated sheep blood [Merck]). Putative E. coli colonies (6 to 35 colonies/sample) were randomly selected, subcultured on nutrient agar slants, and biochemically confirmed to be E. coli. Another four bovine strains, isolated from two nonsymptomatic calves, were kindly provided by M. Bülte, Tierärztliche Nahrungsmittelkunde, Giessen, Germany. O serotyping of E. coli was performed by standard methods (22). E. coli reference strains for PCR and DNA-DNA hybridization were O26:NM strain 413/89-1 (stx1 eae espP/pssA) (36), O128:H2 strain T4/97 (stx2f [see below]) (29), O138:K81 strain E57 (stx2e [see below]) (8), O157:NM strain E32511 (stx2 stx2c [see below]) (30), O157:H7 strain EDL933 (stx1 stx2 eae espP/pssA hlyEHEC) (A. D. O'Brien, T. A. Lively, M. E. Chen, S. W. Rothman, and S. B. Formal, Letter, Lancet i:702, 1983), and H12 (O not typed) strain EH250 (stx2d [see below]) (24).

Human O118 E. coli strains were kindly provided by S. Aleksic, Hygiene Institut, Hamburg, Germany; F. Allerberger, Institut für Hygiene, Innsbruck, Austria; J. Blanco, Laboratorio de Referencia de E. coli, Lugo, Spain; A. Caprioli, Laboratorio di Medicina Veterinaria, Rome, Italy; R. Johnson, Health of Animals Laboratory, Guelph, Ontario, Canada; D. Pierard, Academisch Ziekenhuis, Vrije Universiteit, Brussels, Belgium; H. Smith, Public Health Laboratory Service, London, United Kingdom; and H. Tschäpe, Referenzzentrum für Enterobacteriaceae, Wernigerode, Germany. The 29 strains had been isolated from 27 different individuals with clinical diagnoses of diarrhea, bloody diarrhea, vomiting, HUS, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. In addition, the serogroup O118 type strain 31W/Orskov, which had been isolated from a septicemic calf in 1948 (21), was also included in this study.

PCR analyses.

Primers used for the detection of stx1 were SK1 (5′-GAC TAC TTC TTA TCT GGA TTT-3′) and SK2 (5′-AAC GAA AAA TAA CTT CGC TG-3′); stx2-specific primers were SK3 (5′-CCG GGC GTT TAC GAT AGA CTT-3′) and SK4 (5′-TGC AGC TGT ATT ACT TTC CC) (S. Franke, S. Klein, T. Schlapp, R. Bauerfeind, L. H. Wieler, and G. Baljer, unpublished data). The degenerate primers MK1 and MK2 were used for the detection of both stx1 and stx2 (13). stx2 variants stx2, stx2c, stx2d, stx2e, and stx2f were differentiated by the application of previously published PCR and restriction endonuclease digestion methods. Briefly, stx2 and stx2c were identified by generating amplicons using primers GK3 (5′-CCC GGA TCC ATG AAG AAG ATG TTT ATG GCG-3′) and GK4 (5′-CCC GAA TTC TCA GTC ATT ATT AAA CTG CAC-3′) following digestion with FokI and HaeIII (Gibco BRL, Karlsruhe, Germany) (27). stx2d was identified by PCR with primers VT2-cm (5′-AAG AAG ATA TTT GTA GCG G-3′) and VT2-f (5′-TAA ACT GCA CTT CAG CAA AT-3′) (25), while primers FK1 (5′-CCC GGA TCC AAG AAG ATG TTT ATA G-3′) and FK2 (5′-CCC GAA TTC TCA GTT AAA CTT CAC C-3′) (8) were used to detect the edema disease toxin gene stx2e. In addition, the recently described stx2f gene of E. coli strains from pigeons was detected with primers 128-1 (5′-AGA TTG GGC GTC ATT CAC TGG TTG-3′) and 128-2 (5′-TAC TTT AAT GGC CGC CCT GTC TCC-3′) (29). Plasmid-encoded HlyEHEC and EspP/PssA were identified with primers Ehly1 (5′-GAG CGA GCT AAG CAG CTT G-3′) and Ehly5 (5′-CCT GCT CCA GAA TAA ACC ACA-3′) (36) and with primers PssA1 (5′-TTG CGA AAA ATG GCG GAA CTC-3′) and PssA3 (5′-CGG AGT CGT CAG TCA GTA GA-3′) (6), respectively. Primers ECW1 (5′-TGC GGC ACA ACA GGC GGC GA-3′) and ECW2 (5′-CGG TCG CCG CAC CAG GAT TC-3′) were specific for the eae gene (37). The gene encoding H antigen (fliC) was identified with primers F-FLIC1 (5′-ATG GCA CAA GTC ATT AAT ACC CAA C-3′) and R-FLIC2 (5′-CTA ACC CTG CAG CAG AGA CA-3′) (7). fliC-specific amplicons were digested with RsaI (Gibco BRL) as recommended by the manufacturer.

PCR mixtures contained 5.0 μl of template DNA (50 μl of overnight bouillon plus 100 μl of distilled water at 100°C for 10 min), 1.25 μl of 20× PCR buffer (TFL-Puffer; Biozym, Hessisch-Oldendorf, Germany), 1.25 μl (10 ng/μl) of each primer, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 0.25 U of DNA polymerase (TFL; Biozym). Amplification was performed on a Thermocycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 30 cycles.

DNA-DNA hybridization.

DNA probes ECW1-ECW2 (eae), SK1-SK2 (stx1), SK3-SK4 (stx2), and PssA1-PssA3 (espP/pssA) were labeled during PCR amplification with a nonradioactive Dig-Oxigenin-11-dUTP Kit (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The specific washing step was performed twice with SSC buffer (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate.

CHEF-PFGE.

Preparation of genomic DNA for contour-clamped homogeneous electric field (CHEF)-PFGE was done by following the protocol of Liebisch and Schwarz (15). Slices of DNA containing agarose plugs were incubated for 4 h with 20 U of XbaI (Gibco BRL) or BlnI (Amersham-Pharmacia-Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). The respective DNA fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (Molecular Biology Certified Agarose; Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) in a CHEF-DRII system (Bio-Rad) at 5.5 V/cm with 0.5% Tris-borate-EDTA as a running buffer. The pulsed-field times for XbaI were increased from 7 to 12 s during the first 11 h and from 20 to 40 s for the next 13 h. Those for BlnI digests were increased from 7 to 12 s during the first 11 h and from 20 to 65 s for the next 11 h. Polymerized phage DNA served as a size standard (48.5 to 1,018.5 kb). CHEF-PFGE patterns between these sizes were analyzed with GelCompar (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium).

RESULTS

PCR and DNA-DNA hybridization assays.

Twenty-nine human E. coli O118 strains and 7 bovine O118 strains were analyzed for EHEC virulence-associated factors. Twenty-five of the human strains harbored stx genes (16 stx1 only and 9 stx2 only). All seven bovine strains were positive for stx1. Two of the latter contained stx2 in addition to stx1. Characterization for further virulence traits led us to subdivide the isolates into three distinctive groups. As shown in Table 1, 23 strains that displayed all features of typical EHEC were designated group 1. All strains in this group were stx1 positive and harbored eae and the large virulence-associated plasmid, as confirmed by the detection of hlyEHEC and espP/pssA. The seven bovine E. coli O118 strains belonged to this group. Group 2 contained 10 human strains only, 4 of which were enterotoxigenic E. coli. The six stx2d-positive strains displayed no additional virulence factors. The three strains lacking the large virulence-associated plasmid were placed into group 3, representing the human strains positive for stx2. The distinctive features of each group were further strengthened by the fact that they consisted of a unique serotype. While strains of group 1 displayed serotypes O118:H16 (17 of 23) and O118:NM (6 of 23) only, group 2 strains displayed serotype O118:H12 only and group 3 strains displayed serotype O118:H30 only.

TABLE 1.

Serotypes, sources of isolation, and virulence traits of human and bovine strains of serogroup O118a

| Serotype | Strain | Age group | Source (area) | Clinical status | stx gene(s) | eae gene | hlyEHEC gene | HlyEHEC | espP/pssA gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O118:H16 | CB5482b | Adult | Germany (North Rhine-Westphalia) | Diarrhea, HUS, HIV | stx1 | + | + | + | + |

| CB5483b | Adult | Germany (North Rhine-Westphalia) | Diarrhea, HUS, HIV | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| CB6175 | Child | Germany (Bavaria) | Diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| CB6236 | Adult | Germany | Diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| CB6365c | Adult | Germany (Lower Saxony) | Diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| CB6366c | Adult | Germany (Lower Saxony) | Diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| EH78 | Child | Belgium | Not known | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| E-D143 | Child | Italy | HUS | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| T17968 | Adult | Austria | Diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| VTH28 | Child | Spain | Vomiting | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| VTH62 | Adult | Spain | Vomiting, diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| EC970130 | Child | Switzerland | Diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| 98-08665 | Adult | Germany (Bavaria) | Diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| 98-10617-1 | Adult | Germany (Schleswig-Holstein) | Diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| 98-12039 | Adult | Germany (North Rhine-Westphalia) | Not known | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| D1154/10 | Calf | Germany (Bavaria) | No diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| 666/89 | Calf | Germany (Bavaria) | Diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| O118:NMd | 98-08935 | Child | Germany (Schleswig-Holstein) | HUS | stx1 | + | + | + | + |

| 557/89 | Calf | Germany (Bavaria) | Diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| 173a103531-1e | Cow | Germany (Bavaria) | No diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| 173a103531-7e | Cow | Germany (Bavaria) | No diarrhea | stx1 | + | + | + | + | |

| 173a433917-1f | Cow | Germany (Bavaria) | No diarrhea | stx1 and stx2 | + | + | + | + | |

| 173a433917-2f | Cow | Germany (Bavaria) | No diarrhea | stx1 and stx2 | + | + | + | + | |

| 31W/Orskovg | Calf | Sweden | Septicemia | − | − | − | − | + | |

| O118:H12 | CB6069 | Adult | Germany (North Rhine-Westphalia) | Diarrhea | stx2d | − | − | − | − |

| EH101 | Adult | Belgium | Diarrhea | stx2d | − | − | − | − | |

| E25702/0 | Adult | United Kingdom | Diarrhea | stx2d | − | − | − | − | |

| E29558/0 | Adult | United Kingdom | Bloody diarrhea | stx2d | − | − | − | − | |

| E40841/0 | Adult | United Kingdom | Diarrhea | stx2d | − | − | − | − | |

| E40829/0 | Child | United Kingdom | Blood diarrhea | stx2d | − | − | − | − | |

| 489-36/84h | Child | Peru | Diarrhea | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 488-36/84h | Child | Peru | Diarrhea | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 490-36/84h | Child | Peru | Diarrhea | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 492-36/84h | Child | Peru | Diarrhea | − | − | − | − | − | |

| O118:H30 | E-D27 | Not known | Canada | HUS | stx2 | + | − | − | − |

| E355 | Not known | Canada | Diarrhea | stx2 | + | − | − | − | |

| EC930540 | Adult | Canada | Diarrhea | stx2 | + | − | − | − |

+, present; −, absent.

Strains CB5482 and CB5483 are from the same patient.

Strains CB6365 and CB6366 are from the same patient.

NM, nonmotile.

Strains 173a103531-1 and 173a103531-7 are from the same animal.

Strains 173a433917-1 and 173a433917-2 are from the same animal.

O118 serogroup type strain.

Enterotoxigenic E. coli.

Identification of fliC genes.

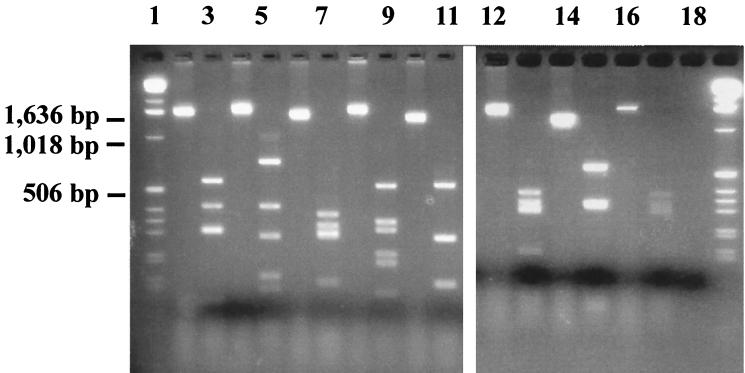

The fact that six strains of group 1 were negative in H typing but showed the same virulence features as all other O118:H16 strains of that particular population prompted us to investigate the presence of the fliC gene, encoding the H antigen. As presumed, specific fliC amplicons could be generated from each of the O118:NM strains investigated. The representative restriction patterns are illustrated in Fig. 1. Digestion with RsaI yielded a distinct restriction pattern for each H type tested (H7, H11, H12, H16, and H30). All fliC amplicons from the O118:NM strains yielded the same restriction pattern as the O118:H16 strains, while the pattern was clearly distinct from those of H7, H12, and H30 strains.

FIG. 1.

PCR analysis of eight representative E. coli strains with various H types. Amplicons were size fractionated by electrophoresis through 3.0% agarose gels. Amplicons obtained with primer pair F-FLIC1–R-FLIC2 indicate the existence of fliC. PCR amplicons are depicted in lanes with even numbers; the respective RsaI-generated restriction patterns are depicted in lanes with odd numbers. Lanes: 1 and 19, 1-kb DNA ladder (Gibco BRL); 2 and 3, E-D27 (O118:H30); 4 and 5, CB6069 (O118:H12); 6 and 7, CB6175 (O118:H16); 8 and 9, EDL933 (O157:H7); 10 and 11, 413/89-1 (O26:H−); 12 and 13, 173a433917-2 (O118:H−); 14 and 15, 31W/Orskov (O118:H−); 16 and 17, CB6175 (O118:H16); 18, double-distilled water (negative control).

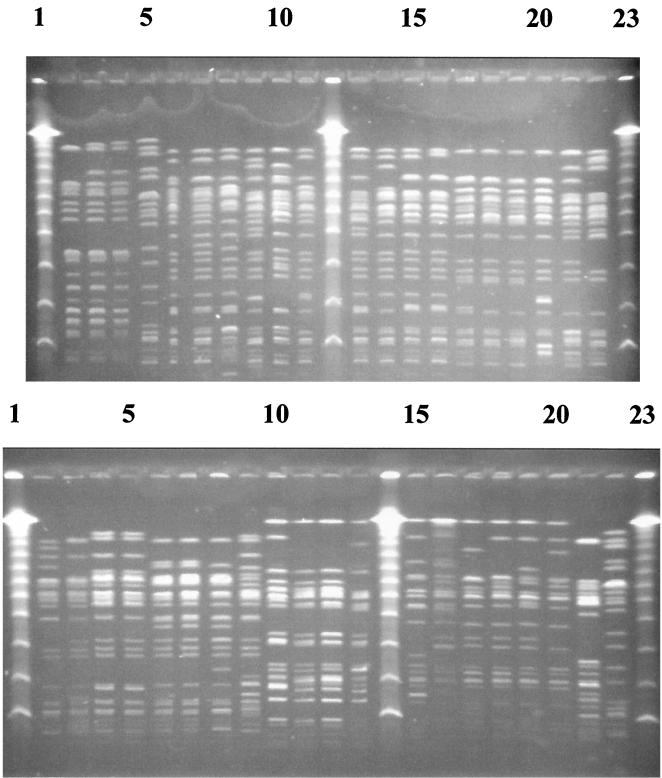

Macrorestriction analysis.

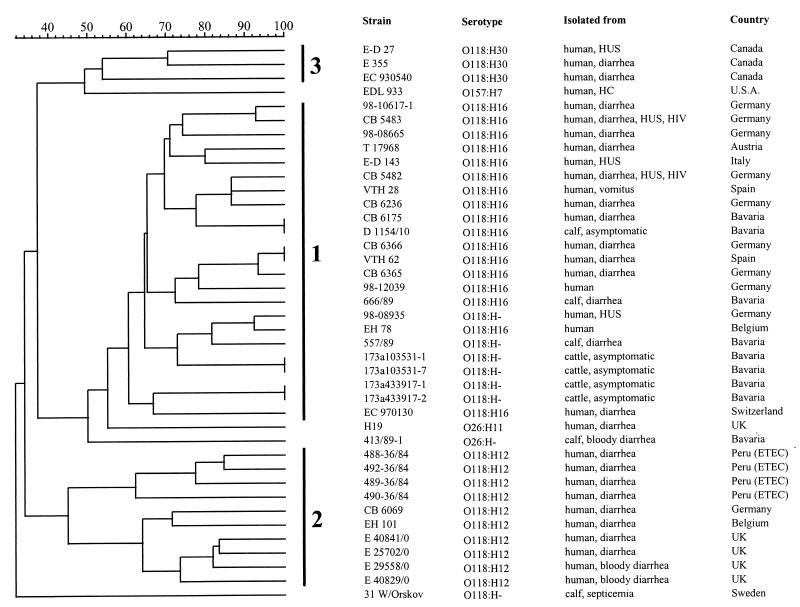

To identify their clonal relationship, the strains were analyzed by CHEF-PFGE (using restriction endonucleases XbaI and BlnI) (Fig. 2 and 3). Restriction with XbaI led to 15 to 21 fragments, while BlnI generated between 12 and 15 fragments. Three clusters were obtained by the Jaccard product-moment correlation coefficient method after the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic average clustering (Fig. 4). Each cluster represented exactly the three groups identified through virulence typing and serotyping. In cluster 1, harboring 23 strains, four pairs were identified which were indistinguishable from each other. One pair consisted of the human (CB 6175) and calf (D 1154/10) strains reported previously by Weber et al. (31). A second pair was formed by two human strains (one isolated in Germany [CB6366] and the other from Spain [VTH62]). The other two pairs originated from cattle, each pair from one animal.

FIG. 2.

CHEF-PFGE electropherogram of XbaI-restricted genomic DNA from E. coli strains (angle, ±60°; voltage, 5.5 V/cm; pulsed-field times, 7 to 12 s for the first 11 h and 20 to 65 s for the next 13 h; ramping, linear). (Top) Lanes: 1, 12, and 23, lambda DNA concatemers (Gibco BRL); 2, E-D27; 3, E355; 4, EC930540; 5, EDL933; 6, CB5483; 7, 98-10617-1; 8, 98-08665; 9, E-D143; 10, T17968; 11, VTH28; 13, CB5482; 14, CB6236; 15, CB6175; 16, D1154/10; 17, VTH62; 18, CB6366; 19, CB6365; 20, 98-12039; 21, 666/89; 22, EH78. (Bottom) Lanes: 1, 14, and 23, lambda DNA concatemers (Gibco BRL); 2, 98-08935; 3, 557/89; 4, 173a103531-1; 5, 173a103531-7; 6, 173a433917-1; 7, 173a433917-2; 8, EC970130; 9, H19; 10, 488-36/84; 11, 492-36/84; 12, 489-36/84; 13, 490-36/84; 15, EH101; 16, CB6069; 17, E40841/0; 18, E25702/0; 19, E29558/0; 20, E40829/0; 21, 31W/Orskov; 22, EDL933.

FIG. 3.

CHEF-PFGE electropherogram of BlnI-restricted genomic DNA from E. coli strains (angle, ±60°; voltage, 5.5 V/cm; pulsed-field times, 7 to 12 s for the first 11 h and 20 to 65 s for the next 11 h; ramping, linear). Panels and lanes are as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

FIG. 4.

Dendrogram outlining the clonal relationship of bovine and human E. coli strains of serogroup O118, determined by macrorestriction analysis of genomic DNA with BlnI. See the text for details. U.S.A., United States; UK, United Kingdom. ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli.

DISCUSSION

Ruminants, especially bovines, are considered the primary reservoir for human infections with EHEC (14). For EHEC strains of serogroup O118, this fact seems to apply only to strains of serotype O118:H16. We and others have previously shown that O118:H16 and O118:NM EHEC strains are highly prevalent in bovines (4, 26, 34, 35, 37); during the last decade, however, we have not been able to isolate any bovine strains of serotype O118:H12 or O118:H30. We previously noted that bovine O118:H16 strains are a possible health threat for humans, since they carry the same virulence traits as typical EHEC strains (35). Sporadic cases of human infections with O118:H16 and O118:NM EHEC in Europe and Canada (2, 5, 11, 31) confirmed that notion. However, our data show that these findings are valid only for strains of serotypes O118:H16 and O118:NM and not for strains of serotypes O118:H12 and O118:H30.

To our knowledge, EHEC strains of serotypes O118:H12 and O118:H30 have been isolated only from humans. Previous studies reported the isolation of O118:H16 and O118:NM EHEC strains from bovines at distant geographical locations worldwide (2, 16–18, 20, 28), with the highest prevalence in Germany and Belgium (26, 35). This finding indicates that bovines are the main reservoir for these strains. In addition, clonal analysis of 52 bovine strains of these serotypes revealed that the strains are endemic in cattle (4). Such strains were also isolated sporadically from pigs (9). In contrast to that of strains of serotypes O118:H16 and O118:NM, the origin of strains of serotypes O118:H12 and O118:H30 remains obscure.

It is noteworthy that such a wide spectrum of different EHEC strains can exist within a single serogroup. While O118:H16 and O118:NM strains harbor all the virulence factors (stx1, eae, hlyEHEC, and espP/pssA) typical for EHEC (19), detection of the intimin structural gene eae revealed that strains of serotype O118:H30 possess stx2 and the locus of enterocyte effacement, while strains of serotype O118:H12 carry stx2d only. All O118:NM strains harbor the fliC gene, encoding the H antigen; this gene was indistinguishable from that detected in O118:H16 strains. Taken together, the results of clonal analysis, virulence typing, and O and H typing justify the designation of three distinctive O118 EHEC serotypes.

Only three of the human O118 strains characterized were isolated from patients with HUS, and this association was not restricted to stx2-positive strains only. These findings are in contrast to the situation for the most intensively studied EHEC serotype, O157:H7, in which the occurrence of stx2 is associated with a higher likelihood of HUS (23). The stx2d variant has only recently been reported to be associated with strains less frequently isolated from patients with EHEC-associated symptoms (24). Thus, our findings also have implications for defining the role of specific virulence factors in different serotypes.

The first EHEC epidemic including HC associated with yet another EHEC O118 serotype, O118:H2, was reported in Japan (12), where a total of 241 (43%) out of 561 persons were defined as being infected. While the authors were not able to identify the precise source of infection, a statistical analysis revealed that different salads (coleslaw salad, chicken and cucumber salad with cold mustard sauce, sour sauce salad, egg salad, and corn salad) in the school lunches that the 561 persons had eaten were the high-risk food items, while there was no indication that any food of bovine origin was involved. All O118:H2 strains isolated were positive for stx1 only. We therefore assume that four unique EHEC serotypes exist in the O118 serogroup.

Our results reflect the clonal spread of E. coli pathogens and have implications for understanding bacterial evolution in general and the pathogenesis of diarrheagenic E. coli. The different clustered CHEF-PFGE patterns displayed by EHEC serotypes O118:H16, O118:H12, and O118:H30 imply close and unique clonal relationships among the pathogens of each specific serotype. The data strongly support the theory that pathogenic E. coli strains occur in clonal populations with broad host ranges and a wide geographical distribution (32). On the other hand, such clonal relationships contrast with the findings for EHEC strains of serogroup O157. The EHEC strains of this serogroup isolated so far are of serotypes O157:H7 and O157:NM only. Like O118:H16 and O118:NM (see Results), O157 serotypes share identical flagellin genes (7). They are therefore closely related and were derived from an enteropathogenic E. coli-like O55:H7 ancestor that carried eae and acquired the stx2 gene, if the evolutionary model developed by Whittam (32) applies. According to this model, the stx2 gene was acquired in one step at an early stage. Clearly, the evolution of EHEC strains of serogroup O118 is more complex, since the three different serotypes display unique patterns of virulence traits, rendering this serogroup particularly interesting for studies of bacterial evolution.

The espP/pssA gene, which was only recently reported for EHEC strains of serotypes O26:NM (6) and O157:H7 (3), is also present in the O118 type strain 31W/Orskov, isolated from a septicemic calf in 1948 in Sweden (20). This result emphasizes the impressive geographical and temporal spread of this virulence-associated factor. In O26:NM and O157:H7 EHEC strains, this gene is located within remnants of different insertion sequences on the large virulence-associated plasmid. Analysis of the DNA region in the neighborhood of espP/pssA in strain 31W/Orskov could yield clues about the evolution of this particular gene.

On a technical note, the results obtained for O118 strains with PFGE after digestion with restriction endonucleases BlnI and XbaI revealed that XbaI generated so many bands that the analysis was too discriminative. Thus, in future studies of clonal relationships in EHEC strains, investigators might consider testing BlnI as an alternative restriction endonuclease.

We believe that our studies contribute to the definition of virulence traits necessary for a particular pathogenic E. coli type to cause a certain disease. They should also deepen insight into the evolution and host adaptation of these highly variable pathogens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. F. G. Schmidt for suggestions on the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants Wi 1436/3-1 and Ka 717/3-1 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bockemühl J, Karch H. Zur aktuellen Bedeutung der enterohämorrhagischen Escherichia coli (EHEC) in Deutschland (1994–1995) Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 1996;39:290–296. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boerlin P, McEwen S A, Boerlin-Petzold F, Wilson J B, Johnson R P, Gyles C L. Associations between virulence factors of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and diseases in humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:497–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.497-503.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunder W, Schmidt H, Karch H. EspP, a novel extracellular serine protease of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7, cleaves human coagulation factor V. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:767–778. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3871751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busse B, Franke S, Steinrück H, Schwarz S, Harmsen D, Karch H, Baljer G, Wieler L H. Clonal analysis of Shigatoxin-producing E. coli (STEC) of serogroup O118 reveals these strains to be zoonotic EHEC pathogens. Acta Clin Belg. 1999;54:47. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caprioli A, Luzzi I, Rosmini F, Resti C, Edefonti A, Perfumo F, Farina C, Goglio A, Gianviti A, Rizzoni G. Communitywide outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome associated with non-O157 verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:208–211. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.1.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Djafari S, Ebel F, Deibel C, Krämer S, Hudel M, Chakraborty T. Characterization of an exported protease from Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:771–784. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5141874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fields P I, Blom K, Hughes H J, Helsel L O, Feng P, Swaminathan B. Molecular characterization of the gene encoding H antigen in Escherichia coli and development of a PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism test for identification of E. coli O157:H7 and O157:NM. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1066–1070. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1066-1070.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franke S, Gunzer F, Wieler L H, Baljer G, Karch H. Construction of recombinant Shiga-like toxin-IIv (SLT-IIv) and its use in monitoring the SLT-IIv antibody response of pigs. Vet Microbiol. 1995;43:41–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garabal J I, Gonzales E A, Vazques F, Blanco J, Blanco M, Blanco J E. Serogroups of Escherichia coli isolated from piglets in Spain. Vet Microbiol. 1996;48:113–123. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldwater P N, Bettelheim K A. New perspectives on the role of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other enterohaemorrhagic E. coli serotypes in human disease. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:1039–1045. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-12-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gyles C, Johnson R, Gao A, Ziebell K, Pierard D, Aleksic S, Boerlin P. Association of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli hemolysin with serotypes of Shiga-like-toxin-producing Escherichia coli of human and bovine origins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4134–4141. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4134-4141.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto H, Mizukoshi K, Nishi M, Kawakita T, Hasui S, Kato Y, Ueno Y, Takeya R, Okuda N, Takeda T. Epidemic of gastrointestinal tract infection including hemorrhagic colitis attributable to Shiga toxin 1-producing Escherichia coli O118:H2 at a junior high school in Japan. Pediatrics. 1999;103:E2. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karch H, Meyer T. Single primer pair for amplifying segments of distinct Shiga-like toxin genes by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2751–2757. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.12.2751-2757.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karmali M A. Infection by verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:15–38. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liebisch B, Schwarz S. Evaluation and comparison of molecular techniques for epidemiological typing of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Dublin. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:641–646. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.641-646.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louie M, de Azavedo J, Clarke R, Borczyk A, Lior H, Richter M, Brunton J. Sequence heterogeneity of the eae gene and detection of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli using serotype-specific primers. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:449–461. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800051153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mainil J G, Jacquemin E R, Kaeckenbeeck A E, Pohl P H. Association between the effacing (eae) gene and the Shiga-like toxin-encoding genes in Escherichia coli isolates from cattle. Am J Vet Res. 1993;54:1064–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohammad A, Peiris J S M, Wijewanta E A. Serotypes of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from cattle and buffalo calf diarrhoea. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;35:261–265. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nataro J P, Kaper J B. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orksov F. Antigenic relationship between H antigens 1-22 of E. coli and Wramby's H antigens 23W-36W. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1952;32:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orskov F. Antigenic relationships between O groups 1-112 of E. coli and Wramby's O groups 26w-43w. 10 new O groups: 114-123. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1952;31:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orskov F, Orskov I. Serotyping of Escherichia coli. Methods Microbiol. 1984;14:43–112. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostroff S M, Tarr P I, Neill M A, Lewis J H, Hargrett B N, Kobayashi J M. Toxin genotypes and plasmid profiles as determinants of systematic sequelae in Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:994–998. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.6.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piérard D, Muyldermans G, Moriau L, Stevens D, Lauwers S. Identification of new verocytotoxin type 2 variant B-subunit genes in human and animal Escherichia coli isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3317–3322. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3317-3322.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piérard D, Stevens D, Moriau L, Lior H, Lauwers S. Isolation and virulence factors of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli in human stool samples. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:531–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pohl P, Daube G, Lintermans P, Kaeckenbeeck A, Mainil J. Description de 70 souches d'Escherichia coli d'origine bovine possédant les gènes des vérotoxines. Ann Med Vet. 1991;135:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rüssmann H, Kothe E, Schmidt H, Franke S, Harmsen D, Caprioli A, Karch H. Genotyping of Shiga-like toxin genes in non-O157 Escherichia coli strains associated with haemolytic uraemic syndrome. J Med Microbiol. 1995;42:404–410. doi: 10.1099/00222615-42-6-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandhu K S, Clarke R C, McFadden K, Brouwer A, Louie M, Wilson J, Lior H, Gyles C L. Prevalence of the eaeA gene in verotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains from dairy cattle in southwest Ontario. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;116:1–7. doi: 10.1017/s095026880005888x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt H, Scheef J, Morabito S, Caprioli A, Wieler L H, Karch H. A new Shiga toxin 2 variant (Stx2f) from Escherichia coli isolated from pigeons. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1205–1208. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.3.1205-1208.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitt C K, McKee M L, O'Brien A D. Two copies of Shiga-like toxin II-related genes common in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli strains are responsible for the antigenic heterogeneity of the O157:H− strain E32511. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1065–1073. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.1065-1073.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber A, Klie H, Richter H, Gallien P, Timm M, Perlberg K W. Über die derzeitigen Probleme zum Auffinden von Infektionsquellen und Infektionsketten beim enterohämorrhagischen E. coli (EHEC) Berl Muench Tieraerztl Wochenschr. 1997;110:211–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whittam T S. Evolution of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. In: Kaper J B, O'Brien A D, editors. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. pp. 195–209. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wieler L H. Inaugural thesis. Giessen, Germany: Justus Liebig University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wieler L H, Bauerfeind R, Baljer G. Characterization of Shiga-like toxin producing Escherichia coli (SLTEC) isolated from calves with and without diarrhoea. Int J Med Microbiol Virol Parasitol Infect Dis. 1992;276:243–253. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wieler L H, Schwanitz A, Vieler E, Steinrück H, Kaper J B, Baljer G. Virulence properties of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains of serogroup O118, a major group of STEC pathogens in calves. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1604–1607. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1604-1607.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wieler L H, Tigges M, Schäferkordt S, Ebel F, Djafari S, Schlapp T, Chakraborty T. The enterohemolysin phenotype of bovine Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli (SLTEC) is encoded by the EHEC-hemolysin gene. Vet Microbiol. 1996;52:153–164. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(96)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wieler L H, Vieler E, Erpenstein C, Schlapp T, Steinrück H, Bauerfeind H, Byomi A, Baljer G. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) from bovines: association of adhesion with the carriage of eae and other genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2980–2984. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.2980-2984.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]