Abstract

Using of targeted contrast agents in X‐ray imaging of breast cancer can improve the accuracy of diagnosis, staging, and treatment planning by providing early detection and superior definition of tumour volume. This study demonstrates a new class of X‐ray contrast agents based on gold nanoparticles (GNPs) and bombesin (BBN) for imaging of breast cancer in radiology. GNPs were synthesised in spherical shape in the size range of 15 ± 2 nm and conjugated with BBN followed by coating with polyethyleneglycol (PEG). The in vitro and in vivo behaviour of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate was investigated performing cytotoxicity, binding, and internalisation assays as well as biodistribution and X‐ray imaging studies in mouse bearing breast tumour. Cytotoxicity study showed biocompatibility of the prepared bioconjugate. The binding and internalisation studies using T47D cell line approved the targeting ability of new agent. The biodistribution study showed the considerable accumulation of prepared conjugate in breast tumour in mouse model. The breast tumour was clearly visualised in X‐ray images taken from the mouse model. The results showed the potential of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate as a contrast agent in X‐ray imaging of breast tumour in humans that need further investigations.

Inspec keywords: diagnostic radiography, cancer, tumours, radiology, gold, nanoparticles, nanomedicine, polymers, coatings, toxicology, cellular biophysics

Other keywords: bombesin conjugated gold nanoparticles, breast cancer, radiology, targeted contrast agents, X‐ray imaging, X‐ray contrast agents, spherical shape, polyethyleneglycol, coating, in vitro behaviour, in vivo behaviour, cytotoxicity, internalisation assays, biodistribution, mouse bearing breast tumour, biocompatibility, bioconjugate, T47D cell line, Au

1 Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the leading causes of death in women today [1]. Many research are ongoing to develop more effective nanoprobes with a targeting capability for efficient molecular imaging to early detection of breast cancer [2, 3]. Of the various medical imaging systems, X‐ray imaging is among the most convenient imaging/diagnostic tools in hospitals in terms of availability, efficiency, and cost [4]. Current contrast agents for X‐ray imaging were based on iodinated small molecules because, among non‐metal atoms, iodine has a high X‐ray absorption coefficient [5]. Iodinated compounds however impose serious limitations on medical imaging including: short imaging times, the need for catheterisation in many cases, occasional renal toxicity, and poor contrast in large patients. With advances in the synthesis of a variety of nanomaterials, there has been a surge of interest in the use of nanoparticles as imaging probes for in vivo biomedical applications [6]. Cai et al. [7] used colloidal gold (Au) nanoparticles (GNPs) as a blood‐pool contrast agent for X‐ray computed tomography in mice in 2007. Then, Popovtzer et al. [8] reported that targeted GNPs enable molecular computed tomography imaging of cancer in 2008. In a recent study, Kandil et al. [9] evaluated the imaging efficiency of GNPs and iodine encapsulated in polymer nanocapsules as X‐ray contrast agents’. The research performed by Hainfeld et al. [10] in 2014 was the first demonstration that reported Au nanoparticles (GNPs) may overcome the limitations caused by iodinated compounds as a contrast agent in X‐ray imaging. Au has higher absorption than iodine (2.7 times greater attenuation per unit weight than iodine) with less bone and tissue interference achieving better contrast with lower X‐ray dose. Nanoparticles clear the blood more slowly than iodine agents, permitting longer imaging times. Au's physical properties also allow good contrast in higher X‐ray photon energies (80–100 keV) which exhibit lower soft tissue absorption and thus lower radiation toxicity to patients. Nevertheless, the use of free GNPs leads to rapid clearance from the bloodstream due to uptake by reticular endothelial system including macrophages in the liver and spleen [11]. Also, plasma proteins and salts in blood non‐specifically adsorb onto the surface of bare GNPs, which cause the production of large aggregates [12].

The synthesis, physical and biological properties, and surface chemistry of GNPs have been intensively studied [13]. The size and shape of GNPs can be easily controlled, and they possess easily controllable surface chemistry allowing functionalisation with various biologically useful molecules to help evade immune detection and improve stability. In the previous report, we modified the surfaces of GNPs with polyethyleneglycol (PEG) and studied the biodistribution of PEG‐coated GNPs in mouse model bearing breast tumour [14]. The study showed that PEGylation can improve the stability and persistence of GNPs in blood‐circulation, and consequently allowing greater accumulation in breast tumour tissue and longer imaging times, but the induced contrast was not enough to visualise the tumour clearly.

It has a great potential for early detection of breast cancer using molecular targeting of nanoparticles, because aberrations at the cellular and molecular levels occur much earlier than anatomic changes [12]. In addition, imaging based on molecular‐specific targets allows real‐time in vivo monitoring of the treatment course and can provide fundamental insights into cancer biology. Bombesin (BBN) and its human counterpart gastrin‐releasing peptide (GRP), a family of brain‐gut peptides, have shown to play an important role in cancer growth [15]. GRP receptors are over‐expressed in many cancers including breast, prostate, and small cell lung cancer [16]. The low expression of BBN/GRP receptors in normal tissues and relatively high expression in a variety of human tumours can, therefore, be of biological importance and form a molecular basis for targeting X‐ray imaging. In this paper, we used a BBN analogue derived from the universal binding sequence (KGGCDFQWAV‐bAla‐HF‐NIe) known to bind to all four receptor subtypes [17]. This property may overcome some problems related to receptor heterogeneity in breast tumours. Furthermore, it has a hydrophilic and negatively charged aspartic acid residue that enhances its renal clearance and may solve the kidney retention problem. At first, Okarvi et al. used this BBN analogue labelled with 99m Tc for scintigraphy of breast cancer in 2010 (17). In another study, this analogue conjugated with super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles was used successfully as a targeting contrast agent in Magnetic resonance imaging of breast cancer in 2015 [3], but our study is the first to develop a targeting contrast agent specific to GRP receptors for early diagnosis of breast tumour in radiology based on GNPs and BBN.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Material

Chloroauric acid (HAuCl4. 3H2 O), foetal bovine serum (FBS), Roswell Park Memorial Institute‐1640, streptomycin, penicillin, trypsin–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, analytical grade nitric (HNO3), hydrochloric acid (HCl), 4‐(2‐hydroxyethyl)‐1‐piperazine‐ethanesulphonicacid (HEPES) buffer and trypan blue were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Trisodium citrate and polyethylene glycol (mPEG‐SH 5000) were purchased from Merck, Germany. Human breast cancer cell line (T47D) and human skin cancer cell line, E8 (AG01522), were purchased from Pasteur Institute, Tehran, Iran. BBN peptide synthesis (KGGCDFQWAV‐bAla‐HF‐NIe) was ordered to Gen Script Company, USA.

2.2 Synthesis of GNPs

The GNPs in spherical shape with a peak absorption wavelength at 515 nm were synthesised by the citrate reduction of HAuCl4 [18]. A 25 ml tri‐neck round bottom bottle was washed in aqua regia (three parts HCl, one part HNO3) and rinsed with distilled deionised water. About 100 ml of 1 mM HAuCl4 solution was heated and refluxed while being stirred. Then, 10 ml of a 38.8 mM trisodium citrate solution was added to the solution quickly. After the colour changing from yellow to black and finally to deep red colour, the solution was refluxed for 15 min and then cooled at room temperature. The particles were then characterised by ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) light absorption. The size and morphology of produced GNPs were analysed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a Hitachi HF‐2000 field emission high‐resolution operating at 200 kV.

2.3 Biofunctionalisation of GNPs

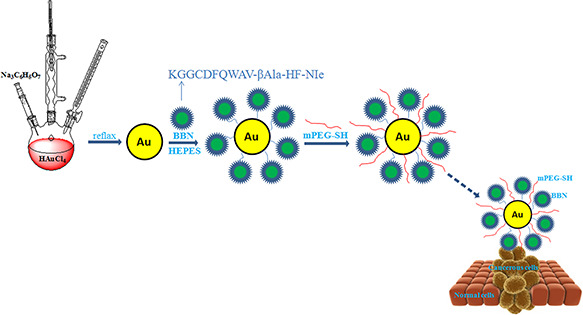

The conjugation of BBN with GNPs was performed using the method described by El‐Sayed et al. [18]. Basically, the GNPs were diluted in 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) to the final concentration with optical density of 0.8 at 515 nm. About 40 µl (6 mg/ml) BBN were added to 960 µl of the same HEPES buffer to form 1 ml dilute solution. Then, 10 ml of the Au solution was added dropwise to the dilute peptide solution while being stirred. After stirring for 5 min, the solution was left to react for 20 min. 0.5 ml of 1% mPEG‐SH was added to the mixture to prevent aggregation and the solution was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 30 min. The BBN/Au pellet was redispersed in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) buffer (pH = 7.4) and stored at 4 °C (Fig. 1). For comparison study, bare GNPs were reacted with mPEG‐SH directly to produce PEGylated GNPs as the passive targeting agent.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of bioconjugation of GNPs in spherical shape with BBN and the PEGylation process

2.4 PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate characterisation

UV–vis spectroscopy (Cary 100 Bio, Varian, USA) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT‐IR) (Nicolet Magna 560 IR, USA) were performed to confirm the binding of GNPs with BBN peptide and its PEGylation [19, 20, 21].

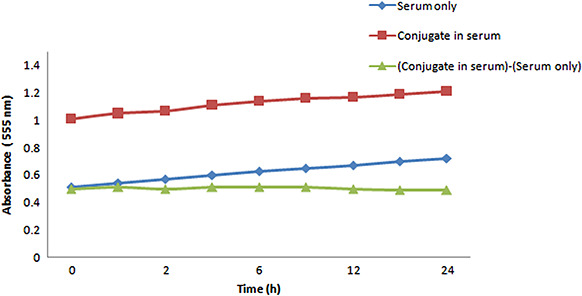

2.5 Optical stability of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate in human blood serum

Blood is a very complex tissue and many of its compounds such as hydrogen, Na, Cl, Ca as well as proteins, lipids, hydrocarbons, and multiple cellular components could interfere with the proper functioning of injected nanoparticles. To verify the stability of the prepared bioconjugate in human blood serum, it was added to 1/1 ratio of serum/PBS [22]. The optical absorbance of solution at 530 nm was monitored at multiple time points for 12 h. The control solution was included human blood serum and PBS only (1/1 ratio). Subtracting the ‘serum’ absorbance from the ‘bioconjugate in serum’ absorbance showed the conjugate absorbance. If the conjugate absorbance remained intact around 530 nm, it was indicated that the new agent was stable in human blood serum.

2.6 Cytotoxicity study

The cell viability was examined by MTT assay [12]. Briefly, T47D cells were planted into a 96‐well plate with 200 μl of RPMI medium and incubated at 37 °C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h. The cell plate was rinsed with PBS to remove unattached cells and 1 ml fresh culture medium was added to each well. The medium of each well was then replaced with 100 µl of fresh medium containing various concentrations of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate (10, 20, 40, 80, and 100 µg/ml). After 24 h, the cells were treated with 10 μl MTT solution (5 mg ml−1 in PBS) and incubated for 4 h. Finally, the wells were evacuated and 100 μl dimethyl sulphoxide was added to each well. The cell viability was quantified by measuring the optical absorbance (630 nm) by an enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay plate reader. The cell viability was expressed as the percentage of survival compared with the untreated cells (incubated just with RPMI medium) as control. In addition, the similar protocol was performed for determining the cell cytotoxicity of PEGylated GNPs for comparison study.

2.7 Binding study

The selective binding of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate was investigated using T47D cell line (over expressing GRP receptors) and E8 (AG01522) cell line (not expressing GRP receptors) as control [11, 18]. Both cell lines were cultivated in RPMI‐1640 with 10% (w/v) FBS and 1% (w/v) penicillin. PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN and PEGylated GNPs conjugates were added to the cell plates separately and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Then, the cell plates were rinsed in PBS twice to remove the unattached bioconjugate molecules. The samples were finally stained using silver enhancement kit (Life Technologies, L‐24919, USA) to visualise the conjugates using a Micros Model IX70 microscope equipped with a Lumenera digital camera.

2.8 Internalisation study

About 1 × 105 T47D cells were added to each well of a 24‐well plate including RPMI medium. After 24°h, the cells were incubated with PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate [12, 19]. At various time points (1, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h), the medium was removed and the cells (in half of wells) were exposed to 1 ml of 1 M NaOH and the rest of cells were exposed to 1 ml of acetic acid with pH 4. The resulted solutions were digested in 500 µl of aqua regia (HCl: HNO3 = 3:1 v/v) at 60 °C for 5 h. The concentration of GNPs in each well was determined using atomic absorbance spectroscopy (AA240FS, Varian, USA), separately. Actually, NaOH solution destructs whole of T47D cells and the resulted solution is considered as the internalised, bound, and dissociated bioconjugate molecules. Acetic acid dissociates interaction between PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate molecules and GRP receptors in the surface of cells and GNPs concentration of this solution is considered as the bound and dissociated bioconjugate. The difference between these two concentrations was considered as the internalised bioconjugate into the cells. The same procedure was repeated for PEGylated GNPs for comparison study.

2.9 Biodistribution study

The tumour had been originally established from a spontaneous breast tumour from an inbred female BALB/c mouse. The breast tumour was xenografted by subcutaneous implantation of tumour fragments (3 × 3 × 3 mm3) on the left‐hand side of abdominal region of 30 normal inbred female BALB/c mice (25–35 g, 6–7 weeks old) [3]. Biodistribution study was performed when the xenograft volume reached 10 × 10 × 10 mm3. The mice were injected via tail vein with 200 µl of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN (the active targeting agent, 20 mg Au kg−1) and sacrificed at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h post injection (five mice for each time point). The blood was collected by cardiac puncture and the liver, heart, intestines, kidneys, stomach, pancreas; muscle and tumour tissues were dissected, weighted, and dissolved completely by adding 9 ml of HCl and 3 ml of HNO3 at 70 °C for 30 min. The solution was diluted with deionised water and filtered with 0.45 ml teflon filter. The solution was evaporated, a necessary amount of 0.5 N HCl was added and the sample was analysed for Au by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) using a standard curve spanning 0–100 µg/l [12, 22]. The uptake of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate in each organ was calculated as the mean percentage of injected dose per gram of organ tissues (%ID/g). For comparison study, 30 BALB/c mice with subcutaneous breast‐tumour xenograft were injected via tail vein with 200 µl of PEGylated GNPs (the passive targeting agent) for analysing Au concentration according to the described method. All the animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Tarbiat Modares University.

2.10 X‐ray imaging

For X‐ray imaging, five BALB/c mice bearing xenografted breast tumour were injected with 200 μl of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN solution (20 mg Au kg−1) via the tail vein [11]. Prior to X‐ray imaging, the animals were anesthetised with the combination of xylazine hydrochloride and ketamine hydrochloride. The imaging was performed using a clinical mammography unit (MAMMO X‐ray Unit 100 kHz, Payamed Electronic Industries Co., Iran) before the injection of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate (the active targeting agent) and at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h post injection (exposure parameters: 22 kV and 10 mAs). For comparison study, five BALB/c mice with subcutaneous tumour xenograft were injected via tail vein with 200 µl of PEGylated GNPs (the passive targeting agent) according to the described method.

2.10.1 Statistical analysis

All the experiments were repeated five times and the results were expressed as mean ± Standrsd Deviatiuon. Analysis of variance test was used to compare the accumulation of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN and PEGylated GNPs conjugates in vital organs and tumour tissue of mouse model in different time points (P < 0.05).

3 Results

3.1 Characterisation of synthesised GNPs

According to the UV–vis absorbance spectrum (Fig. 2), the synthesised GNPs had λ max at 515 nm. The transmission electron micrograph showed the spherical shape of produced GNPs with the diameter size of 15 ± 2 nm (Fig. 2, inset image).

Fig. 2.

UV–vis spectrum of synthesised GNPs with the λmax at 515 nm. Inset image: TEM micrograph of produced GNPs in spherical shape with the diameter size of 15 ± 2 nm (scale line = 50 nm)

3.2 Characterisation of PEG‐coated GNPS‐BBN conjugate

3.2.1 UV–vis spectroscopy

On surface modification, the optical resonance peak of GNPs was slightly red‐shifted (5 nm) due to a minor change in the refractive index on the surface. The red shift indicated the successful binding of BBN molecules to GNPs surfaces (Fig. 3) [21]. Then, the UV–vis spectrum of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate showed a red shift of 10 nm in the absorbance peaks between GNPs‐BBN (520 nm) and PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugates (530 nm). The PEGylation changes the local environment and thus the surface plasmon absorption of GNPs‐BBN is changed.

Fig. 3.

UV–vis spectra of free GNPs, GNPs‐BBN, and PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugates. The red shifting occurred during each step of the bioconjugate synthesis further indicated the successful fabrication of GNPs (a red shift of 5 nm in the absorbance peaks between GNPs (515 nm) and GNPs‐BBN (520 nm) and a red shift of 10 nm in the absorbance peaks between GNPs‐BBN (520 nm) and PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugates (530 nm)

3.2.2 FT‐IR spectroscopy

To confirm the binding of BBN to GNPs, the FT‐IR analysis was performed on BBN before and after the conjugation process. The NH2 stretching frequency of the amine group observed at 3423 cm−1 was shifted to the higher wavelength at 3430 cm−1 after the conjugation reaction that meant direct binding of nitrogen atoms of free amino group to GNPs (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

FT‐IR spectra of

(a) BBN conjugate, (b) GNPs‐BBN conjugate. The NH2 stretching frequency of the amine group observed at 3423 cm−1 was shifted to the higher wavelength at 3430 cm−1 after the conjugation reaction. The red shifting shows direct binding of nitrogen atoms of free amino group to GNPs

3.3 Optical stability

Over the course of 24 h, the absorbance of serum (Fig. 5, the curve with ▲ symbol) and serum plus the conjugate (Fig. 5, the curve with ■ symbol) were monitored. The curve with ♦ symbol represents the subtraction of ‘serum’ from ‘PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN’ absorbance that is a stable and consistent absorbance curve. This result indicated that PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate had a high level of optical stability when exposed to the blood serum. The curves show a slight increase of absorbance over time, an effect which is likely due to the evaporation of water from the samples thereby increasing the concentration of serum in the sample [19].

Fig. 5.

Optical serum stability of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate. The new bioconjugate showed a high level of optical stability when exposed to the blood serum up to 24 h

3.4 Cytotoxicity study

The cytotoxicities of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate and PEGylated GNPs were determined by evaluating the viability of breast cancer cells (T47D) using MTT assay (Fig. 6). The evaluation showed both agents have no toxicity to the cells up to the concentration of ∼100 μg/ml after incubation for 24 h (more than 80% viability).

Fig. 6.

Viability of T47D cells after 24 h incubation with PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate (black bars) and PEGylated GNPs (grey bars) at 10–100 µg/ml concentrations (P < 0.05)

3.5 Binding study

When PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate was incubated with T47D and E8 (AG01522) cells for the same time, the T47D cell surfaces were heavily labelled with functionalised GNPs due to the specific binding of BBN to GRP receptors on the surface of the carcinoma cells. This specific interaction between the new bioconjugate and the cells were stained using the silver staining kit to visualise GNPs as dark spots under conventional bright field microscopy (Fig. 7 a). There is not seen any dark spot in Fig. 7 c as E8 (AG01522) cells have no GRP receptors to be attached when incubated with PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate. For comparison study, free GNPs (in PEGylated form) were incubated with T47D and E8 (AG01522) cells. There was no evidence of cell binding that showed non‐selective activity of untargeted GNPs toward breast cancer cells (Fig. 7 b and d). These results indicated that selective binding to cancer cells can be achieved by utilising the BBN as a targeting ligand.

Fig. 7.

Selective binding of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate to T47D cells (scale bar: 100 µm). Silver staining was performed to enable visualisation during bright field microscopy to study the fate of GNPs in their interaction with the T47D and E8 (AG01522) cells

(a) T47D cells incubated with PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate, (b) T47D cells incubated with PEGylated GNPs, (c) E8 (AG01522) cells incubated with PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate, (d) E8 (AG01522) cells incubated with PEGylated GNPs

3.6 Internalisation study

The cellular uptake of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate was estimated by measuring GNPs concentration within T47D cells using AAS. The results showed that GNPs concentration increased in T47D cells significantly after being decorated with BBN in comparison with free GNPs in PEGylated form (79% versus 18%, respectively, up to 24 h). This finding implied that peptide–receptor‐mediated endocytosis was helpful for cellular uptake of functionalised GNPs (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Quantification of GNPs uptake (in conjugation with BBN and in free form) by T47D cells using AAS. The analysis revealed that the cellular uptake of new bioconjugate by T47D cells was more than %50 after 6 h (in comparison with %12 uptake for free GNPs). This study showed that peptide–receptor‐mediated was helpful for cellular uptake of functionalised GNPs

3.7 Biodistribution study

Fig. 9 a shows the biodistribution of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate in BALB/c mice bearing breast cancer at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h after IV administration expressed as %ID/g. This paper revealed the considerable localisation of the prepared conjugate at the site of tumours at all the measured times. The uptake of bioconjugate by the tumour tissue increased gradually as time increased, reaching a maximum at 6 h (P < 0.05). To confirm the role of BBN as a targeting ligand, free GNPs (in PEGylated form) were injected via the tail vein in breast‐tumour‐bearing mice. As it can be seen, the amount of free GNPs in tumour location (Fig. 9 b) was significantly less than the GNPs in conjugation with BBN (Fig. 9 a), which fully suggests that the new conjugate has ability to target tumour tissue selectively (P < 0.05).

Fig. 9.

Biodistribution data of

(a) PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN, (b) Free GNPs (in PEGylated form) in breast‐tumour‐bearing BALB/c mice at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h after IV administration expressed as %ID/g measured by AAS (n = 5). The uptake of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN bioconjugate by the tumour tissue increased gradually as time increased, reaching a maximum at 6 h (P < 0.05)

3.8 X‐ray imaging

X‐ray images of a representative BALB/c mouse with breast tumour at different time intervals after IV administration of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate were shown in Figs. 10 b –g. The tumour was visualised properly as early as 6 h after the injection of bioconjugate as a contrast agent (Fig. 10 d). The imaging study approved the capability of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN as a contrast agent for detection of breast cancer in mouse model. Fig. 10 a shows the X‐ray image of the same BALB/c mouse with breast tumour before the bioconjugate injection.

Fig. 10.

X‐ray images of a representative BALB/c mouse bearing

(a) Breast tumour before injection, At different time intervals (b) 2 h, (c) 4 h, (d) 6 h, (e) 8 h, (f) 12 h, and (g) 24 h post injection of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate (exposure parameters: 22 kV and 10 mAs was the same for all images). The marker ‘L’ was used as an unified X‐ray intensity bar

4 Discussion

The development of targeting contrast agents for X‐ray imaging can be efficient in detecting tumours and metastases that are smaller than 0.5 cm and in distinguishing between benign and cancerous tumours [1]. This study takes the advantages of high X‐ray absorption of GNPs in spherical shape and their high cellular uptake by breast tumour cells in conjugation with BBN.

The uniform GNPs were prepared in the size of 15 ± 2 nm in diameter by general reduction of HAuCl4 using sodium citrate [20]. It has been shown that the C‐terminal amino acid sequence of BBN is necessary for retaining receptor binding affinity and preserving the biological activity of BBN‐like peptide [18]. Hence, the N ‐terminal region of the peptide was used for conjugation with GNPs. GNPs have affinity to attach to amine and thiol groups. In addition, they have negative charge on its surface. Then, GNPs‐BBN was coated with PEG to impart antibiofouling properties, which extends their lifetime in bloodstream [23]. PEGylation helps in providing a stealth character when administered in the blood stream of living organisms that allows them to evade the immune response [12, 23]. Then, the stability of bioconjugate in human blood serum was studied. The results indicated that PEG molecules on the surface of the bioconjugate were enough to prevent interaction between serum proteins and the GNPs, which is particularly important for achieving their lengthy blood‐circulation in vivo and in subsequent receptor‐targeting applications [12, 23].

With all newly developed bioconjugate preparations, the potential of toxicity remains an important factor in determining their medical applications [20]. Although GNPs were known to be biocompatible and non‐toxic [10, 13], we performed MTT assay to determine the toxicity of the new bioconjugate in vitro. Fig. 6 shows cell viability data for T47D cells after 24 h of incubation with 10–100 µg/ml of the prepared bioconjugate. As expected, the nanoparticles did not show any appreciable toxicity, even at 100 µg/ml, which is probably much higher concentration than encounters in vivo. We next examined whether PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate could preferentially bind to target T47D breast cancer cells or not? So, T47D cells (over‐expressing GRP receptors) and E8 cells (as a negative control) were incubated with the bioconjugate at 37 °C for 1 h and then washed with PBS to remove unbound GNPs [12, 18]. To visualise GNPs, we stained treated cells using silver enhancement kit. Figs. 7 a and c show silver‐stained optical images of T47D and E8 cells incubated with the bioconjugate, respectively. As it can be seen in Fig. 7 a, numerous black spots representing aggregated silver metal deposited on GNPs are clearly identifiable on T47D cells after treatment with the new conjugate. In contrast, no or few such silver‐enhanced spots are detectable in E8 cells treated with the prepared conjugate (Fig. 7 c). Furthermore, T47D and E8 cells were incubated with free GNPs (in PEGylated form) to double check the targeting characteristic of the bioconjugate. There was not seen any (or few) black spots in the microscopic images in both cell types (Figs. 7 b and d). Actually, the receptor specific interaction of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate provides a realistic opportunity in design and development of in vivo molecular imaging of breast cancer.

Next, the internalisation study was performed to quantify the uptake of new conjugate by breast cancer cells in vitro [12]. The results showed that, within 6 h, the intracellular uptake of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate increased significantly in comparison with free GNPs (in PEGylated form). This behaviour was expected because the BBN sequence, chosen in the present study, has agonist properties, which means they have specific receptors (in this case, GRP receptors) to internalise within the cells [17]. It can be seen that the bioconjugate exhibits time‐dependent taken‐up by T47D cells (Fig. 8). These findings further suggested that the designed bioconjugate can be used as a promising contrast agent for in vivo targeted X‐ray imaging of breast tumour.

Then, the biodistribution study was performed to evaluate the localisation of new conjugate in tumour as well as in vital organs in mouse model. Fig. 9 a shows the considerable accumulation of new conjugate in tumour tissue. The low concentration of free GNPs (unbound) in tumour tissue (Fig. 9 b) in comparison with the new bioconjugate approved the targeting ability of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate toward the breast cancer cells. The accumulation of BBN is always high in pancreas due to the high GRP receptors in this organ as compared with other vital organs according to the available information in the literature about the BBN‐like peptides [16, 24]. Our results clearly demonstrated that the biodistribution of prepared conjugate follows the similar trend with other studies. These results provide unequivocal evidence that the significant uptake of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate in pancreatic acini and within the tumour in breast‐tumour‐bearing BALB/c mice (Fig. 9 a) are indeed mediated through GRP receptors, and consequently it implies that the new contrast agent is a reliable vector for targeted GRP receptors that are over expressed in breast cancer cells. For comparison study, we investigated the localisation of free GNPs (in PEGylated form) in tumour tissue in the similar way to confirm the specificity of the prepared conjugate into the target cells. As we expected, the accumulation of free GNPs in tumour tissue was not as much as the functionalised GNPs (<65%). However, the presence of free GNPs in tumour tissue was due to the enhanced permeability and retention effect.

After demonstrating the targeted localisation of PEG‐coated GNPs‐BBN conjugate in breast tumour in mouse model, we monitored the ability of new preparation as an X‐ray contrast agent to visualise the breast tumour in radiology. The mice with xenografted breast cancer were injected subcutaneously with the bioconjugate and repeatedly imaged from 2 up to 24 h post injection. Figs. 10 a –g show the serial X‐ray images of a representative BALB/c mice bearing breast cancer before injection and at different time intervals post injection. The tumour could be seen easily as early as 6 h after IV administration of the new contrast agent. The imaging study approved the results of biodistribution study.

5 Conclusion

The findings demonstrated the potential of prepared bioconjugate as an X‐ray targeted contrast agent for breast cancer imaging in human beings that needs further investigations such as X‐ray computed tomography. GNPs can be used as X‐ray contrast agent with properties that overcome some significant limitations of iodine‐based agents.

6 Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Zanjan Branch, Islamic Azad University for valuable support. We acknowledge Dr. Zahra Heidari for her technical support.

7 References

- 1. Libson S. Lippman M.: ‘A review of clinical aspects of breast cancer’, Int. Rev. Psychiatry, 2014, 26, pp. 4 –15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee S. Kang S.W. Ryu J.H. et al.: ‘Tumor‐homing glycol chitosan‐based optical/PET dual imaging nanoprobe for cancer diagnosis’, Bioconjug. Chem., 2014, 25, pp. 601 –610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jafari A. Salouti M. Shayesteh S.F. et al.: ‘Synthesis and characterization of Bombesin‐superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as a targeted contrast agent for imaging of breast cancer using MRI’, Nanotechnology, 2015, 26, p. 075101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chien C.C. Chen H.H. Lai S.F. et al.: ‘Gold nanoparticles as high‐resolution X‐ray imaging contrast agents for the analysis of tumor‐related micro‐vasculature’, J. Nanobiotechnol., 2012, 10, pp. 1 –12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li X. Anton N. Zuber G. et al.: ‘Contrast agents for preclinical targeted X‐ray imaging’, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev, 2014, 76, pp. 116 –133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. He X. Liu F. Liu L. et al.: ‘Lectin‐conjugated Fe2 O3 @ Au core@ shell nanoparticles as dual mode contrast agents for in vivo detection of tumor’, Mol. Pharm., 2014, 11, pp. 738 –745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cai Q.Y. Kim S.H. Kim C.K. et al.: ‘Colloidal gold nanoparticles as a blood‐pool contrast agent for X‐ray computed tomography in mice’, Invest. Radiol., 2007, 42, (12), pp. 797 –806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Popovtzer R. Agrawa A. Kotov N.A. et al.: ‘Targeted gold nanoparticles enable molecular CT imaging of cancer’, Nano Lett.., 2008, 8, (12), pp. 4593 –4596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kandil B. Shalaby T. Fekry N. et al.: ‘Evaluation of the imaging efficiency of gold nanoparticles and iodine encapsulated in polymer nanocapsules as X‐ray contrast agents’, Int. J. Chem. Appl. Biol. Sci., 2014, 1, p. 18 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hainfeld J.F. Slatkin D. Focella T. et al.: ‘Gold nanoparticles: a new X‐ray contrast agent’, Br. J. Radiol., 2014, 79, pp. 248 –253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sun I.C. Na J.H. Jeong S.Y. et al.: ‘Biocompatible glycol chitosan‐coated gold nanoparticles for tumor‐targeting CT imaging’, Pharm. Res., 2014, 31, pp. 1418 –1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heidari Z. Sariri R. Salouti M.: ‘Gold nanorods‐bombesin conjugate as a potential targeted imaging agent for detection of breast cancer’, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B, 2014, 130, pp. 40 –46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jain S. Hirst D. O'sullivan J.: ‘Gold nanoparticles as novel agents for cancer therapy’, Br. J. Radiol., 2014, 85, pp. 101 –113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salouti M. Heidari Z. Saghatchi F.: ‘PEGylated gold nanoparticles as a biocompatible contrast agent in X‐ray imaging of breast tumor in mouse model’, Greener J. Biol. Sci., 2014, 4, pp. 146 –153 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chanda N. Shukla R. Katti K.V. et al.: ‘Gastrin releasing protein receptor specific gold nanorods: breast and prostate tumor avid nanovectors for molecular imaging’, Nano Lett.., 2009, 9, pp. 1798 –1805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chanda N. Kattumuri V. Shukla R. et al.: ‘Bombesin functionalized gold nanoparticles show in vitro and in vivo cancer receptor specificity’, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2010, 107, pp. 8760 –8765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Okarvi S.M. Al Jammaz I.: ‘Synthesis and evaluation of a technetium‐99m labeled cytotoxic bombesin peptide conjugate for targeting bombesin receptor‐expressing tumors’, Nucl. Med. Biol., 2010, 37, pp. 277 –288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. El‐Sayed I.H. Huang X. El‐Sayed M.A.: ‘Selective laser photo‐thermal therapy of epithelial carcinoma using anti‐EGFR antibody conjugated gold nanoparticles’, Cancer Lett., 2006, 239, pp. 129 –135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eghtedari M. Liopo A.V. Copland J.A. et al.: ‘Engineering of hetero‐functional gold nanorods for the in vivo molecular targeting of breast cancer cells’, Nano Lett., 2008, 9, pp. 287 –291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nghiem T.H.L. Nguyen T.T. Fort E. et al.: ‘Capping and in vivo toxicity studies of gold nanoparticles’, Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol., 2012, 3, p. 015002 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rostro‐Kohanloo B.C. Bickford L.R. Payne C.M. et al.: ‘The stabilization and targeting of surfactant‐synthesized gold nanorods’, Nanotechnol. J., 2009, 20, p. 434005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kircher M.F. De la Zerda A. Jokerst J.V. et al.: ‘A brain tumor molecular imaging strategy using a new triple‐modality MRI‐photoacoustic‐Raman nanoparticle’, Nat. Med., 2012, 18, pp. 829 –834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lipka J. Semmler‐Behnke M. Sperling R.A. et al.: ‘Biodistribution of PEG‐modified gold nanoparticles following intratracheal instillation and intravenous injection’, Biomaterials, 2010, 31, pp. 6574 –6581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heidari Z. Salouti M. Sariri R.: ‘Breast cancer photothermal therapy based on gold nanorods targeted by covalently‐coupled bombesin peptide’, Nanotechnology, 2015, 26, p. 195101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]