Abstract

Despite the unique properties, application of garlic essential oil (GEO) is too limited in food and drugs, due to its low water solubility, very high volatility and unpleasant odour. In this work, a nanoemulsion containing GEO was formulated to cover and protect the volatile compounds of GEO. The encapsulation efficiency of formulated nanoemulsions was measured by gas chromatography and obtained encapsulation efficiency ranged from 91 to 77% for nanoemulsions containing 5–25% GEO, respectively. The 2,2‐diphenyl‐1‐picrylhydrazyl method for antioxidant activity measurement showed that free radical scavenging capacity of nanoemulsions intensified during storage time. The electrical conductivity of the samples was constant over storage time while linearly increased by raising the temperature. Thermogravimetric analysis was used to determine the thermal resistance of nanoemulsions and their ingredients. Interestingly, microbial tests cleared that the control nanoemulsion with a particle size below 100 nm (nanoemulsion without GEO) also showed antimicrobial activity. Disk diffusion method showed that pure GEO and also formulated nanoemulsions had a stronger effect against Gram‐positive bacterium (Staphylococcus aureus) than Gram‐negative bacterium (Escherichia coli).

Inspec keywords: emulsions, nanostructured materials, antibacterial activity, microorganisms, electrical conductivity, thermal analysis, thermal resistance, oils, nanobiotechnology, food safety, cellular biophysics

Other keywords: garlic oil‐in‐water nanoemulsion; antimicrobial aspects; physicochemical aspects; garlic essential oil; GEO; volatile compounds; encapsulation efficiency; gas chromatography; 2,2‐diphenyl‐1‐picrylhydrazyl method; antioxidant activity measurement; free radical scavenging capacity; storage time; electrical conductivity; thermogravimetric analysis; thermal resistance; antimicrobial activity; disk diffusion method; Gram‐positive bacterium; Staphylococcus aureus; Gram‐negative bacterium; Escherichia coli

1 Introduction

Garlic (Alluim sativum) belongs to Alliaceae family and has 1–2% (dry basis) essential oil. It is known for medical properties such as lowering blood cholesterol, anti‐inflammatory and anticancer activity and also antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral and antioxidant properties [1]. Essential oils are the mixture of low molecular weight components with some functional properties which produced by various parts of plants [2]. They contain various components such as terpene hydrocarbons and oxygenated derivatives (alcohol, aldehyde, ketones, acids and esters) [1]. Also, their characteristic aroma and biological properties are attributed to terpenoids and phenylpropanoids [2]. Especially, garlic essential oil (GEO) has shown a great potential for insecticidal, antimicrobial [1] and powerful antioxidant activity [1, 3].

In the recent years, food scientists have discovered a new type of oil in water nanoemulsion namely antimicrobial nanoemulsions. The particle size of antimicrobial nanoemulsions ranged from 200 to 600 nm and they are formed by oil, water and surfactant without the addition of any natural and synthetic antimicrobial material. They are active against Gram‐positive and negative bacteria, mould, yeast, fungi, viruses and spores [4]. Recently, Donsì et al. [5] fabricated nanoemulsion‐based delivery systems of two essential oils, a terpenes mixture extracted from Melaleuca alternifolia and D‐limonene. They reported that the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) values of the nanoencapsulated terpenes, tested on three different microorganisms (Escherichia coli (E. coli), L. delbrueckii and S. cerevisiae), were lower than or equal to the MIC and MBC values of the unencapsulated mixture. Also, nanoencapsulation of D‐limonene reduced the MIC values significantly while not changed MBC values compared to the unencapsulated D‐limonene. Guarda et al. [6] formulated a nanoemulsion of thymol and carvacrol by using Tween 20 and Gum Arabic as the surfactant, and evaluated their antimicrobial activity against pathogenic fungi (A. niger) and food borne microbes like Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), E. coli, L. innocua and S. cerevisiae. They reported that Thymol microcapsules inhibited the growth of bacteria with the MIC value of 250 ppm while a MIC value of carvacrol was 225 ppm.

Nowadays, regarding the side effects of chemical preservatives used in food formulation on human health, incorporating essential oils in foods as preservatives (as safe natural compounds) creates a great potential to produce foods free from synthetic additives [7, 8]. However, use of antimicrobial essential oils in foods still associated with several drawbacks like their poor water solubility, toxicological and economical aspects [9, 10]. Moreover, application of essential oil in food formulation makes problems in some food products in particular at high doses due to their strong odour and flavour. Consequently, the investigation of new delivery systems and controlled release of essential oil is severely required [11]. This research was aimed to encapsulate the GEO and cover its objectionable odour while protecting its unique properties. In addition, the effect of nanoencapsulation on the antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of GEO was also evaluated.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Materials

The essential oil of garlic was purchased from Zardband Co (Tehran, Iran). Tween 80, DPPH (2, 2‐diphenyl‐1‐picrylhydrazyl) and citric acid were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich Co. Mueller–Hinton agar was purchased from Merck Co. All used materials were analytical grade. Bacteria strains of E. coli and S. aureus were prepared from Artimia Institute of Urmia University, Iran.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Nanoemulsion preparation

Essential oil of garlic and Tween 80 were mixed by magnetic stirrer for 5 min at 500 rpm and then the mixed oil phase (Tween 80 and essential oil of garlic mixture) was added slowly to the aqueous phase (distilled water containing 0.8% citric acid) while mixing by magnetic stirrer for 15 min at 700 rpm (25 ± 3). Then, the premixed emulsions transferred to the ultrasonic water bath (100 W and 40 kHz) for 15 min (25 ± 3). The ratio of surfactant to oil was fixed at (1:1) for all of the nanoemulsions and oily phase content was varied from 5 to 25% [12].

2.2.2 Particle size determination

Dynamic light scattering (Malvern Instruments Ltd with a precision range of measurement 0.6 nm–6 μm) was used to determine the particle size. All of the nanoemulsions diluted with distilled water with a ratio of 1:50 in orders to prevent multi‐scattering during the particle size measurement. Experiments were carried out at 25°C and with a 90° angle of refraction [13].

2.2.3 Encapsulation efficiency measurement

Gas chromatography (Agilent Technologies) equipped with flame ionisation detector (FID) and HP5 column (50 m × 0.32 mm × 25 μm) was used to measure encapsulation efficiency by Talou et al. [14] with modifications. Nitrogen was used as carrier gas with a flow rate of 0.7 ml/min. Injection inlet and detector temperatures were 120 and 300°C, respectively. Also, oven temperature increased at a rate of 5°C/min from 40°C to 90°C and maintained for 2 min at this temperature. Before injection, the samples were heated to 40°C and then sampling was carried from the headspace. The encapsulation efficiency was determined by comparing the total area under the peaks obtained from the headspace of the nanoemulsions and non‐emulsified mixtures

| (1) |

2.2.4 Measuring antioxidant activity

DPPH free radical scavenging activity was calculated for the samples. At first, 60 μM solution of DPPH in the methanol was prepared. Then, 0.5 ml of samples added to the 3 ml of prepared solutions and after stirring for 2 min, the mixture transferred to the dark for 30 min. Finally, after centrifuging at 6000 for 5 min, the absorbance of the samples was measured at 517 nm by a spectrophotometer (Pharmacia Nova spec II). The absorbance of the DPPH solution without sample after maintaining for 30 min in the dark place was considered as a control [15]. Free radical scavenging percent calculated as follows:

| (2) |

2.2.5 Electrical conductivity measurement

The conductometer (Metrohm, Swiss made) was calibrated using various concentrations of KCl solution (0.01, 0.1 and 1 normal) with the known conductivity. Then the conductivity of the samples was measured at 25°C [16]. Then, in order to the calculation of kinetic parameters, data of the electrical conductivity versus temperature were fitted to the Arrhenius equation (1) and the kinetic parameters such as activation energy as well as a fitting parameter (σ 0) of nanoemulsion samples were calculated

| (3) |

where is the electrical conductivity at temperature T (K), σ 0 is the fitting parameter, E a is the activation energy for the changes in electrical conductivity affected by temperature, and R is the ideal gas constant.

2.2.6 Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

TG/DTG analyses were performed simultaneously by a thermogravimetric analyser (STA PT‐1000) from Linseis Co. Data was recorded in the temperature range from 25 to 600°C with the heating rate of 10°C/min. Dry nitrogen was used as a purge gas at a flow rate of 50 ml/min. The sample weight was 40.0 mg [17].

2.2.7 Microbial test by disk diffusion

The studied bacteria including S. aureus (25923 ATCC) and E. coli H7 O157 (700728 ATCC) were cultured on Mueller–Hinton agar and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Then the dilution of 0.5 McFarland was prepared from the colonies of this environment by saline for each bacteria separately, which their absorption was equal to 0.08–0.1 at a wavelength of 620 nm (the number of bacteria in this amount of absorbance is equal to 1.5 × 108 CFU/ml). The bacteria spread on the Mueller–Hinton agar with sterile swab and then paper discs (which immersed in the prepared nanoemulsion for 1 h before) were placed on plates. Finally, the plates were incubated at 37°C and the diameter of inhibition zone was measured using a millimetre rule after 24 h [18].

2.2.8 Statistical analysis

All of the experiments were carried out in duplicate or triplicate at least for mean and standard deviation calculation. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine significant differences between treatments and Duncan's multiple range tests were used for treatments mean comparison.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Particle size analysis

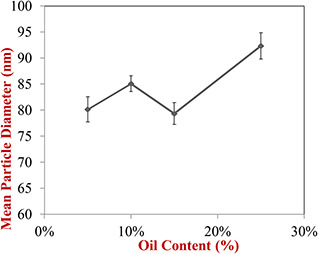

Statistical analysis showed that the particle size of nanoemulsions was significantly affected by the dispersed phase ratio in nanoemulsions formulation (p < 0.05). As shown in Fig. 1, with the increase of the dispersed phase proportion in nanoemulsion formulations, the particle size has also increased. Although changing in particle size was no outstanding in lower dispersed phase ratio but particle size of nanoemulsions was increased significantly in higher dispersed phase ratio that it seems to be due to the fact that there was an equal content of essential oil of garlic and surfactant in nanoemulsion formulation and the surfactant molecules were able to surround the encapsulated material.

Fig. 1.

Influence of oily phase content on mean particle diameter of prepared nanoemulsions

Also based on the obtained results, the type of oil used in nanoemulsion formulation had a significant effect on the particle size at a fixed ratio of the dispersed phase and replacing essential oil of garlic with sunflower oil increased the particle size. In recognition of these results, Ziani et al. [19] encapsulated the functional lipophilic compounds such as vitamin D, vitamin E and lemon oil in the surfactants based on colloidal delivery systems and they reported that the type of oil and surfactant significantly affected the characteristics colloidal dispersions. Also, Saberi et al. [20] fabricated oil in water nanoemulsions containing vitamin E and optimised particle size of nanoemulsions by some factors. They also reported that the type of oil used in nanoemulsion formulation affected the size of particles.

3.2 Encapsulation efficiency

Results showed that dispersed phase ratio was significantly affected encapsulation efficiency (p < 0.05). As shown in Table 1, the encapsulation efficiency was decreased significantly from 91 to 77% by increasing of dispersed phase ratio from 10 to 25%. It may be attributed to the fact that surfactant molecules were not well able to surround the oil molecules in the higher dispersed phase ratios. This study results were similar to Mazloom and Farhadyar [21] results; they reported that encapsulation efficiency decreased by rising of essential oil content of blueberries in the nanoemulsions formulation. Also, Rachmadi et al. [22] encapsulated silymarin and curcumin by ultrasonic emulsification method and they reported that the encapsulation efficiency decreased with increasing oil phase percent in nanoemulsion formulation so that increasing the content of silymarin and curcumin from 5 to 35 mg in oil phase (10% w/w) decreased the encapsulation efficiency from 99 to 75% for curcumin and 80% for silymarin.

Table 1.

Encapsulation efficiency (%) for produced nanoemulsions determined by gas chromatography

| Nanoemulsion type | Encapsulation efficiency | |

|---|---|---|

| nanoemulsions containing 5% GEO | 91.63 ± 1.15 | a |

| nanoemulsions containing 10% GEO | 86.33 ± 1.25 | b |

| nanoemulsions containing 15% GEO | 84.96 ± 0.47 | c |

| nanoemulsions containing 25% GEO | 77.46 ± 0.65 | d |

Similar letters show no significant difference in (α = 0.05).

According to the previous researches, allicin (Allyltrisulphide) accounts for 25% of all garlic volatile components [23], so the indicative peak can attribute to the allicin which appears about 10 min. By comparison of the obtained chromatograms from head space of nanoemulsions and non‐emulsified mixture (GEO + water + surfactant), it can be found that the trace volatile components of GEO (they have shown peaks at 3–5 min) were covered more than major volatile components (allicin). The peak height for allicin decreased from 5500 pA in the not emulsified mixture to 3000 pA in nanoemulsions. Although the peaks of trace volatile components of GEO were approximately disappeared in nanoemulsions, it can be stated that the encapsulation efficiency of nanoemulsions was more dependent on the covering of the major component of garlic (allicin) compared to other minor components.

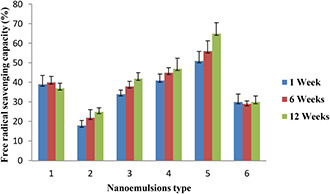

3.3 Antioxidant activity

The results of experiments carried out with the DPPH method showed that by increasing the percentage of a GEO in the formulation of nanoemulsions, their antioxidant activity increased and the effect of the dispersed phase ratio on antioxidant activity was significant (p < 0.05). As shown in Fig. 2, the antioxidant activity of nanoemulsions prepared by GEO was relatively higher than those prepared by sunflower oil, which can be attributed to the higher content of natural antioxidant compounds in GEO compared to the sunflower oil. Zorzi et al. [24] formulated the nanoemulsions of Achyroclines atureioides containing quercetin and reported that there was no significant difference between the antioxidant activity of nanoemulsion containing quercetin and nanoemulsions without it.

Fig. 2.

Antioxidant activity of formulated nanoemulsions at various interval times. 1: pure GEO, 2: nanoemulsion containing 5% GEO, 3: nanoemulsion containing 10% GEO, 4: nanoemulsion containing 15% GEO, 5: nanoemulsion containing 25% GEO, 6: nanoemulsion containing 10% sunflower oil

Ha et al. [25] evaluated the antioxidant activity and bioavailability of nanoemulsions formulated with tomato extract enriched with lycopene and they reported that nanoemulsions with particle sizes between 100 and 200 nm showed the highest antioxidant activity. The high antioxidant activity of lycopene nanoemulsions was associated with particle size. As shown in Fig. 2, the nanoemulsions containing 25% GEO demonstrated the higher antioxidant activity in comparison with the pure GEO that it may be attributed to the nanoscale size (<200 nm) of nanoemulsions.

3.4 Electrical conductivity

Measuring the electrical conductivity of the nanoemulsions can have utilities, for instance, it can be used to determine the type of emulsion, phase inversion temperature and probably instability phenomena of nanoemulsions such as coagulation and flocculation [26, 27].

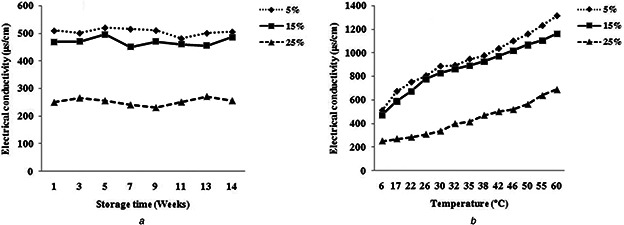

3.4.1 Effect of storage time on the electrical conductivity of nanoemulsion

The results of the electrical conductivity of nanoemulsion containing GEO showed that the electrical conductivity decreased by increasing of GEO (oily phase) percentage in the formulation of nanoemulsions (Fig. 3 a). As the mentioned above, oils have too lower electrical conductivity compared to the water and it leads to reduce electrical conductivity of nanoemulsions. Also, the electrical conductivity changes of nanoemulsions were observed at ambient temperature during storage time but this change was not significant (Fig. 3 a).

Fig. 3.

Change of the electrical conductivity of various nanoemulsions as a function of

(a) Storage time at 25°C, (b) Temperature

Bernardi et al. [16] studied the electrical conductivity's changes during the 90 days of storage at different temperatures. They reported that changes in electrical conductivity was not considerable and was not associated with particle size and so stated that the study on the stability of nanoemulsion exclusively based on electrical conductivity changes appears to be difficult because there is no linear relationship between them. Pereira et al. [27] also evaluated changes in electrical conductivity of the nanoemulsion containing lanolin derivatives during the storage time and observed that little change has occurred in the electrical conductivity of samples and there was no relation between electrical conductivity and instability of nanoemulsion.

3.4.2 Effect of temperature on the electrical conductivity of nanoemulsion

Results showed that the electrical conductivity of all nanoemulsions increased with increasing temperature (Fig. 3 b). High temperature leads to a reduction in viscosity and the enhancement of ions mobility and consequently intensifying the electrical conductivity of nanoemulsions. Also, the rising temperatures likely cause a dissociation of the molecules and increase the number of ions in solution and this can cause increased electrical conductivity in turn [28]. Obtained results from this work were consistent with the results of other researchers. Corach et al. [29] examined the electrical conductivity of mixtures of fatty acid methyl ester from several vegetable oils and temperature effects on their electrical conductivity and reported that with increasing temperature, electrical conductivity also rapidly increased. Also, Pereira et al. [27] evaluated the electrical conductivity of nanoemulsions prepared from vegetable oils and confirmed the increasing of electrical conductivity as a result of raising the temperature.

3.4.3 Kinetics parameters from electrical conductivity

As discussed in the previous section, with increasing temperature, electrical conductivity also increased in a linear way in all nanoemulsion samples. Data of the electrical conductivity versus temperature were fitted to the Arrhenius equation (1) and the kinetic parameters such as activation energy as well as a fitting parameter (σ 0) of nanoemulsion samples were calculated with R 2 higher than 0.90 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Kinetics parameters of nanoemulsions samples by fitting to Arrhenius model

| Nanoemulsions type | Kinetic parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| , μs/cm | ΔE, kJ/mol | R 2 | |

| NE 5% | 15.40 ± 0.9 | 13.10 ± 1.6 | 0.9890 |

| NE 15% | 13.63 ± 1.3 | 13.00 ± 1.8 | 0.9649 |

| NE 25% | 26.82 ± 1.5 | 16.57 ± 2.1 | 0.9490 |

As shown in Table 2, with increasing the GEO percentage (oily phase) from 15 to 25%, the activation energy has also increased in the nanoemulsion formulation. Activation energy defined as the least required energy to perform a reaction or process and higher amounts of activation energy, meaning that it must expend more energy on the process or reaction. By increasing the percentage of the oily phase in the nanoemulsion formulation, they will be also more viscous and thus more attraction between the molecules and this causes slow down the ions mobility and consequently lead to a reduction in sensitivity of electrical conductivity to the temperature.

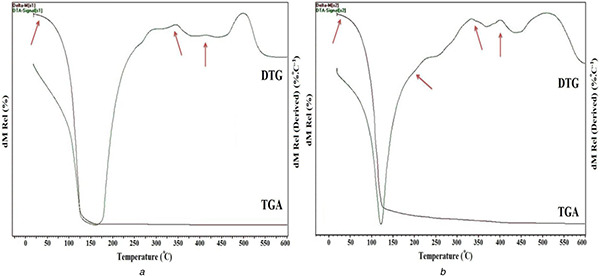

3.5 Thermogravimetric analysis

TGA is used in the research and development of various substances and engineering materials (solid or liquid) in order to obtain knowledge about their thermal stability and composition [30]. The TGA/DTG analysis was used to investigate the degradation temperature of the prepared nanoemulsions under a nitrogen atmosphere from 25 to 600°C. Figs. 4 a and b show the TGA/DTG thermograms of nanoemulsions A (containing 5% essential oil, 5% emulsifier and 90% water) and nanoemulsion B (containing 25% essential oil, 25% emulsifier and 50% water), respectively. Fig. 4 a demonstrates one main degradation step which corresponds to the loss of water from the surface. The following steps were negligible due to the low content of essential oil and emulsifier. Fig. 4 b (DTG curve) indicates four distinct transformation regions with a mass loss in the system. For nanoemulsions B, the first step in the range of 40–190°C can be attributed to the loss of water from the surface. Then that is followed by the second step at 190–340°C that can be related to loss of water [31] and volatile portions of garlic essential oil in the micelles structure. The third step at the range of 340–400°C can correspond to the degradation of residual macromolecules of garlic essential oil. The next step at high temperatures between 400 and 520°C are related to Tween 80 as an emulsifier. Consequently, preparation of nanoemulsions containing GEO, Tween 80 and water were confirmed by TGA/DTG analysis.

Fig. 4.

TGA/DT Gthermograms for

(a) Nanoemulsion A (containing 5% essential oil, 5% emulsifier and 90% water) and (b) nanoemulsion B (containing 25% essential oil, 25% emulsifier and 50% water)

3.6 Microbial test by disk diffusion method

The obtained results from disk diffusion method cleared that all of the produced formulations of nanoemulsions showed antimicrobial activity and have distinctive effects against Gram‐positive (S. aureus) and Gram‐negative (E. coli) bacteria (Table 3). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the antimicrobial activity of garlic. Prevention of DNA, RNA and protein synthesis are among the proposed mechanisms [32]. It was stated that the most antimicrobial activity of garlic is referred to allicin and its metabolites. These compounds play their antimicrobial activities by specific inhibiting the enzyme acetyl coenzyme A‐synthetase, which inhibits the synthesis of lipids and fatty acids and ultimately impairs the viability of the cell [33]. In addition, one of the most important features of organosulfur compounds of garlic is permeability and passing through the membrane phospholipids. Microbial cells due to lack of sufficient quantities of intracellular thiols to neutralise or balance the oxidation of thiols created by organosulfur derivatives and allicin are more sensitive to GEOs compared to the human cells [34].

Table 3.

Average of inhibition zone diameter (mm) for tested bacteria affected by produced nanoemulsions and pure GEO

| Type of bacteria | Nanoemulsion type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE 0 | NE 1 | NE 2 | NE 3 | NE 4 | GEO | |

| S. areus | 13.45 ± 0.3a | 17.66 ± 0.5b | 19.7 ± 0.7c | 22.5 ± 0.7d | 19.65 ± 0.4c | 32.5 ± 0.7e |

| E. coli | 9.1 ± 0.4A | 11.26 ± 0.4B | 12.5 ± 1.2B | 10.33 ± 0.57B | 10.46 ± 0.5A | 12.43 ± 0.4C |

NE 0: nanoemulsion without GEO, NE1: nanoemulsion containing 5% GEO, NE 2: nanoemulsion containing 10% GEO, NE 3: nanoemulsion containing 15% GEO, NE 4: anoemulsion containing 25% GEO.

Note: For each row, similar letters show no significant difference in (α = 0.05).

In general, all of nanoemulsions formulation and also pure GEO have stronger microbial effects against E. coli compared to S. aureus which indicate the more sensitivity of Gram‐positive bacteria to the GEO and produced nanoemulsions in comparison with Gram‐negative bacteria. Although the reason of more sensitivity of Gram‐positive bacteria to EOs is not exactly clear it may be due to the outer membrane of Gram‐negative bacteria which lead to promote hydrophilicity of the external surface of bacteria and acts as a strong barrier against penetration of external components [35].

The majority of the previous researches about the effect of EOs on food born pathogen and food spoilage indicates that Gram‐positive bacteria are more sensitive to the EOs in comparison with Gram‐negative bacteria. However, all studies on the antimicrobial activity of EOs do not indicate more susceptibility of Gram‐positive. For instance, Aeromonas hydrophila, a Gram‐negative bacterium, is one of the most sensitive bacterial species in the EOs. In addition, among Gram‐negative bacteria, Pseudomonas, especially P. aeruginosa has the lowest susceptibility to the EOs [9].

Recently, a lot of works were carried out on this issue and conflicting results have been reported. Semeniuc et al. [36] investigated the antimicrobial effects of several EOs against Gram‐negative and Gram‐positive bacteria and reported that all of the tested EOs have the strongest effect against E. coli compared to S. aureus. In contrast, Hasimi et al. [37] reported that E. coli was more resistant to the anise oil (Pimpinella anisum L.) in comparison with S. aureus.

As shown in Table 3, pure GEO has a stronger microbial effect compared to the nanoemulsions against the tested bacteria. It should be noted that although the inhibition zone diameter of nanoemulsions was lower than pure GEO, but in fact, according to much smaller proportion of GEO in formulation of nanoemulsions compared to the pure GEO and also significant covering the active components of GEO during emulsification, it can be concluded that generally the antimicrobial effect of GEO has increased by emulsification methods (may be due to the protection of active components of GEO and their slow and steady release). Several reports in order to confirm or disapprove this result have been reported by other investigators, which can be implied to enhance the antimicrobial activity of thyme EO after encapsulation by sodium caseinate [38] as well as increasing antimicrobial activity of Lemongrass EO emulsified with Tween 80 and sodium alginate [11]. While the antimicrobial activity of essential oil emulsified by modified starch [39] and eugenol nanodispersed by conjugated maltodextrins and whey proteins has decreased after encapsulation [40]. Generally, the antimicrobial activity of EOs nanoemulsion highly depends on the composition of EOs, tested microbial species, particle size and formulation of nanoemulsions [41].

4 Conclusion

In general, it can be stated that the emulsification of GEO as a feasible method can easily cover and protect (not eliminate) the active volatile components of garlic essential oil. All of the formulated nanoemulsions have antimicrobial activity against bacteria, specifically stronger effect against Gram‐positive bacteria. Interestingly, the formulated nanoemulsions without the addition of GEO have also shown antimicrobial activity and it verifies the previous claims of the researchers about antimicrobial activity of nanoemulsions. Moreover, the enhancement of free radical scavenging activity of the nanoemulsions during storage time was an indicator of the controlled release of entrapped volatile compounds from the inner phase to the outer phase of the nanoemulsion.

5 References

- 1. Lawrence R. Lawrence K.: ‘Antioxidant activity of garlic essential oil (Allium sativum) grown in north Indian plains’, Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed., 2011, 1, (Suppl. 1), pp. S51 –S54 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raut J.S. Karuppayil S.M.: ‘A status review on the medicinal properties of essential oils’, Ind. Crops Prod., 2014, 62, pp. 250 –264 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meriga B. Mopuri R. MuraliKrishna T.: ‘Insecticidal, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of bulb extracts of Allium sativum ’, Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med., 2012, 5, (5), pp. 391 –395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NIMBS‐Website: ‘Michigan Nanotechnology Institute for Medicine and Biological Sciences’, available at http://Nano.Med.Umich.Edu/Platforms/Antimicrobial‐Nanoemulsion.Html, accessed 21 October 2009

- 5. Donsì F. Annunziata M. Sessa M. et al.: ‘Nanoencapsulation of essential oils to enhance their antimicrobial activity in foods’, LWT – Food Sci. Technol., 2011, 44, (9), pp. 1908 –1914 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guarda A. Rubilar J.F. Miltz J. et al.: ‘The antimicrobial activity of microencapsulated thymol and carvacrol’, Int. J. Food Microbiol., 2011, 146, (2), pp. 144 –150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. El Asbahani A. Miladi K. Badri W. et al.: ‘Essential oils: from extraction to encapsulation’, Int. J. Pharm., 2015, 483, (1), pp. 220 –243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seow Y.X. Yeo C.R. Chung H.L. et al.: ‘Plant essential oils as active antimicrobial agents’, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., 2014, 54, (5), pp. 625 –644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burt S.: ‘Essential oils: their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods – a review’, Int. J. Food Microbiol., 2004, 94, (3), pp. 223 –253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sánchez‐González L. Vargas M. González‐Martínez C. et al.: ‘Use of essential oils in bioactive edible coatings: a review’, Food Eng. Rev., 2011, 3, (1), pp. 1 –16 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Salvia‐Trujillo L. Rojas‐Graü A. Soliva‐Fortuny R. et al.: ‘Physicochemical characterization and antimicrobial activity of food‐grade emulsions and nanoemulsions incorporating essential oils’, Food Hydrocolloids, 2015, 43, pp. 547 –556 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ghosh V. Mukherjee A. Chandrasekaran N.: ‘Ultrasonic emulsification of food‐grade nanoemulsion formulation and evaluation of its bactericidal activity’, Ultrason. Sonochem., 2013, 20, (1), pp. 338 –344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ali A. Mekhloufi G. Huang N. et al.: ‘Β‐lactoglobulin stabilized nanemulsions – formulation and process factors affecting droplet size and nanoemulsion stability’, Int. J. Pharm., 2016, 500, (1), pp. 291 –304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Talou T. Delmas M. Gaset A.: ‘Analysis of headspace volatiles from entire black truffle (Tuber melanosporum)’, J. Sci. Food Agric., 1989, 48, (1), pp. 57 –62 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brand‐Williams W. Cuvelier M.E. Berset C.: ‘Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity’, LWT – Food Sci. Technol., 1995, 28, (1), pp. 25 –30 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernardi D.S. Pereira T.A. Maciel N.R. et al.: ‘Formation and stability of oil‐in‐water nanoemulsions containing rice bran oil: in vitro and in vivo assessments’, J. Nanobiotechnol., 2011, 9, (1), p. 44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mendelson‐Mastey C. Larush L. Danino D. et al.: ‘Synthesis of magnesium chloride nanoparticles by the water/oil nanoemulsion evaporation’, Colloids Surf. A, Physicochem. Eng. Aspects, 2017, 529, (Suppl. C), pp. 930 –935 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lu W.‐C. Huang D.‐W. Wang C.‐C.R. et al.: ‘Preparation, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of nanoemulsions incorporating citral essential oil’, J. Food Drug Anal., 2018, 26, (1), pp. 82 –89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ziani K. Fang Y. McClements D.J.: ‘Fabrication and stability of colloidal delivery systems for flavor oils: effect of composition and storage conditions’, Food Res. Int., 2012, 46, (1), pp. 209 –216 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Saberi A.H. Fang Y. McClements D.J.: ‘Fabrication of vitamin E‐enriched nanoemulsions: factors affecting particle size using spontaneous emulsification’, J. Colloid Interface Sci., 2013, 391, pp. 95 –102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mazloom A. Farhadyar N.: ‘Producing oil in water nano‐emulsion by ultrasonication for spray drying encapsulation’, Researcher, 2014, 6, (4), pp. 32 –36 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rachmadi U.W. Permatasari D. Rahma A. et al.: ‘Self‐nanoemulsion containing combination of curcumin and silymarin: formulation and characterization’, Res. Dev. Nanotechnol. Indonesia, 2015, 2, (1), pp. 37 –48 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shan C. Wang C. Liu J. et al.: ‘The analysis of volatile flavor components of Jin Xiang garlic and Tai'an garlic’, Agric. Sci., 2013, 4, (12), pp. 744 –748 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zorzi G.K. Caregnato F. Moreira J.C.F. et al.: ‘Antioxidant effect of nanoemulsions containing extract of Achyrocline satureioides ’, AAPS PharmSciTech., 2016, 17, (4), pp. 844 –850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ha T.V.A. Kim S. Choi Y. et al.: ‘Antioxidant activity and bioaccessibility of size‐different nanoemulsions for lycopene‐enriched tomato extract’, Food Chem., 2015, 178, pp. 115 –121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ribeiro R.C.d.A. Barreto S.M.A.G. Ostrosky E.A. et al.: ‘Production and characterization of cosmetic nanoemulsions containing Opuntia ficus‐indica (L.) mill extract as moisturizing agent’, Molecules, 2015, 20, (2), pp. 2492 –2509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pereira T.A. Guerreiro C.M. Maruno M. et al.: ‘Exotic vegetable oils for cosmetic o/w nanoemulsions: in vivo evaluation’, Molecules, 2016, 21, (3), p. 248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barron J.J. Ashton C.: ‘The effect of temperature on conductivity measurement’, TSP, 2005, 7, (3) [Google Scholar]

- 29. Corach J. Sorichetti P. Romano S.: ‘Electrical properties of mixtures of fatty acid methyl esters from different vegetable oils’, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy, 2012, 37, (19), pp. 14735 –14739 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arrieta M.P. López J. Ferrándiz S. et al.: ‘Characterization of PLA‐limonene blends for food packaging applications’, Polym. Test., 2013, 32, (4), pp. 760 –768 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Che Sulaiman I.S. Basri M. Fard Masoumi H.R. et al.: ‘Design and development of a nanoemulsion system containing extract of Clinacanthus nutans (L.) leaves for transdermal delivery system by D‐optimal mixture design and evaluation of its physicochemical properties’, RSC Adv., 2016, 6, (71), pp. 67378 –67388 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feldberg R.S. Chang S.C. Kotik A.N. et al.: ‘In vitro mechanism of inhibition of bacterial cell growth by allicin’, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 1988, 32, (12), pp. 1763 –1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hann G.: ‘History, folk medicine and legendary uses of garlic’ (Williamsand Wilkins Press, A Waverly company, 1996, 2nd edn.), pp. 1 –24 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harris J.C. Cottrell S.L. Plummer S. et al.: ‘Antimicrobial properties of Allium sativum (garlic)’, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 2001, 57, (3), pp. 282 –286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smith‐Palmer A. Stewart J. Fyfe L.: ‘Antimicrobial properties of plant essential oils and essences against five important food‐borne pathogens’, Lett. Appl. Microbiol., 1998, 26, (2), pp. 118 –122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Semeniuc C.A. Pop C.R. Rotar A.M.: ‘Antibacterial activity and interactions of plant essential oil combinations against Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria’, J. Food Drug Anal., 25, (2), 2017, pp. 402 –408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hasimi N. Tolan V. Kizil S. et al.: ‘Determination of essential oil composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) and Cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) seeds’, Tarim Bilimleri Derg. J. Agric. Sci., 2014, 20, (1), pp. 19 –26 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xue J.: ‘Essential oil nanoemulsions prepared with natural emulsifiers for improved food safety’. PhD, University of Tennessee, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liang R. Xu S. Shoemaker C.F. et al.: ‘Physical and antimicrobial properties of peppermint oil nanoemulsions’, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2012, 60, (30), pp. 7548 –7555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shah B. Davidson P.M. Zhong Q.: ‘Nanodispersed eugenol has improved antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Listeria monocytogenes in bovine milk’, Int. J. Food Microbiol., 2013, 161, (1), pp. 53 –59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Donsì F. Ferrari G.: ‘Essential oil nanoemulsions as antimicrobial agents in food’, J. Biotechnol., 2016, 233, pp. 106 –120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]