Abstract

In the present study Delftia sp. Shakibaie, Forootanfar, and Ghazanfari (SFG), was applied for preparation of biogenic Bi nanoparticles (BiNPs) and antibacterial and anti‐biofilm activities of the purified BiNPs were investigated by microdilution and disc diffusion methods. Transmission electron micrographs showed that the produced nanostructures were spherical with a size range of 40–120 nm. The measured minimum inhibitory concentration of both the Bi subnitrate and BiNPs against three biofilms producing bacterial pathogens of Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Proteus mirabilis were found to be above 1280 µg/ml. Addition of BiNPs (1000 µg/disc) to antibiotic discs containing tobramycin, nalidixic acid, ceftriaxone, bacitracin, cefalexin, amoxicillin, and cefixime significantly increased the antibacterial effects against methicillin‐resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in comparison with Bi subnitrate (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the biogenic BiNPs decreased the biofilm formation of S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and P. mirabilis to 55, 85, and 15%, respectively. In comparison to Bi subnitrate, BiNPs indicated significant anti‐biofilm activity against P. aeruginosa (p < 0.05) while the anti‐biofilm activity of BiNPs against S. aureus and P. mirabilis was similar to that of Bi subnitrate. To sum up, the attained results showed that combination of biogenic BiNPs with commonly used antibiotics relatively enhanced their antibacterial effects against MRSA.

Inspec keywords: nanoparticles, bismuth, nanofabrication, antibacterial activity, microorganisms, biomedical materials, toxicology, nanomedicine, transmission electron microscopy, biochemistry, drugs

Other keywords: Bi, size 40.0 nm to 120.0 nm, mass 1000.0 mug, Delftia sp. SFG, Staphylococcus aureus, antibiofilm mechanisms, antibiofilm effect, antibiofilm activity, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, purified biogenic BiNPs, antibacterial biofilm mechanisms, Bi subnitrate, antibacterial effects

1 Introduction

Biofilm formation which is defined as a dense pack of microbial communities surrounded by extracellular substances such as polysaccharides, proteins, and extracellular DNA is a critical strategy for protecting bacterial communities from harsh environmental conditions and enhancing the resistance to antibiotics [1, 2, 3]. These aggregated communities are responsible for various human infections including a dental plaque of Streptococcus sp. [4], hospital acquired an infection of Staphylococcus epidermidis [5], and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [6], skin infection of Staphylococcus aureus [7] and urinary tract infection caused by Escherichia coli [8]. Despite great progress in pharmaceutical industries, development of microorganisms resistant to common antibiotics has become a challenge for current medicine [9, 10]. Deep understanding of the mechanisms, which microorganisms used against antibiotics, can help scientists for developing new more effective compounds with lower resistance and side effects [9].

Nanotechnology is a promising field for eliminating global healthcare concerns associated with microorganisms’ biofilm formation [11, 12]. Nanoparticles (NPs) with an approximate diameter of 1–100 nm produced via chemical, physical, or biological methods showed extraordinary physiochemical and biological properties [13].

Biological methods because of low production costs and almost zero toxic and harmful materials production preferred compared with those of other physicochemical methods [14, 15, 16, 17, 18]. Application of different biogenic metal and metalloid NPs such as silver nanostructures (AgNPs) [19], tellurium (Te) nanorods [16], selenium NPs (SeNPs) [20, 21], and Fe3 O4 –AgCl nanocomposites [22] as novel antimicrobial and anti‐biofilm agents have been previously reported.

Bismuth (Bi) is a pnictogen element which is typically found in forms of oxide (bismite), sulphide (bismuthinine), and carbonate (bismuthate) [23]. In addition, there are also several organic forms of Bi (such as Bi subnitrate, Bi subcitrate, and Bi subsalicylate), which were used for the treatment of duodenal ulcers, and traveller's diarrhoea [24]. Antimicrobial effect of Bi salts usually occurs at high concentrations because of their low solubility and dispersibility [25]. Production of BiNPs not only resulted in significant solubility enhancement but also provides a large surface to volume ratio which eventuates antibacterial potency enhancement. There are few studies on Bi‐derived NPs as an antibacterial and anti‐biofilm agents. Jassim et al. [25] reported no antibacterial properties for pulsed laser ablation produced Bi oxide NPs against P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, and E. coli while (Te) NPs showed reasonable antibacterial effects against mentioned bacterial species. In another study, the antibacterial properties of Bi2 O3 NPs against S. aureus were studied and it was revealed that 1.5 mg/ml of Bi oxide NPs reduced 45% of bacterial colonies compared with control Bi2 O3 [26].

In the present paper, the antibacterial activity of biogenic BiNPs against methicillin (ME)‐resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was first investigated in comparison with Bi subnitrate. In addition, in order to find if there is any rational relation between the combination of BiNPs and different antibiotics, 18 antibiotic discs were mixed with BiNPs and used for disc diffusion test. In another part of this work, the effect of BiNPs on biofilm formation by clinical isolates of S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and Proteus mirabilis was evaluated.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals and microorganisms

Nutrient broth (NB), Muller–Hinton broth (MHB), sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), n‐octyl alcohol, 2, 3, 5‐triphenyl‐2H‐tetrazolium chloride (TTC), sodium dihydrogen phosphate, dibasic sodium phosphate (Na2 HPO4), Bi subnitrate [Bi5 O(OH)9 (NO3)4], and Tris HCl were purchased from Merck Chemicals (Darmstadt, Germany). Standard antibiotic discs including tobramycin (TOB), nalidixic acid (NA), ceftriaxone (CRO), bacitracin (BAC), vancomycin, cefalexin (CN), cefixime (CFM), gentamicin, tetracycline, amikacin (AN), streptomycin, amoxicillin (AMX), cloxacillin (CX), erythromycin, ME, imipenem (IPM), azithromycin (AZM), and kanamycin were purchased from Mast Company (Merseyside, UK). All other chemicals and solvents were of analytical grade. The BiNPs producing bacterial strain used in the present paper were previously isolated from salty marsh land around Shahr‐e Babak (30°08'00’ N, 55°04'00’), Kerman, Iran and identified as Delftia sp. Shakibaie, Forootanfar, and Ghazanfari (SFG) (16 SrDNA gene was deposited in GenBank under the accession number of KT719174). Delftia sp. SFG was constantly conserved on the MHA plates containing Bi subnitrate (2 mg/ml) using continuous weekly sub‐culturing. Furthermore, the clinical isolates of MRSA, P. aeruginosa, and P. mirabilis were used as the test organisms.

2.2 Biosynthesis and purification of BiNPs

For the preparation of BiNPs, Delftia sp. SFG strain was inoculated aerobically (30°C, 150 rpm) in 100 ml of sterile NB medium supplemented by Bi subnitrate (2 mg/ml). After 72 h, the obtained cell mass containing BiNPs was collected by centrifugation (4000g, 10 min) and it was disrupted by a pestle after freezing by liquid nitrogen in a mortar. The resulting slurry was ultrasonicated (100 W, 5 min) and it was washed three times by sequential centrifugation (10,000g, 5 min) with 1.5 M Tris‐HCl buffer (pH 8.3) containing 1% SDS and deionised water, respectively. Afterwards, by adding n‐octyl alcohol, an organic‐aqueous two partitioning system was used for the isolation of biogenic BiNPs [1].

2.3 Characterisation of biogenic BiNPs

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) apparatus (KYKY‐EM3200) equipped with an energy dispersive X‐ray (EDX) micro‐analyser was employed to study the shape and elemental composition of the purified BiNPs. In addition, a transmission electron microscope (TEM) apparatus (Zeiss 902A) operated at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV was used for obtaining the TEM micrographs and the related size distribution pattern of NPs was plotted by manual counting of 350 individual particles from different TEM images.

2.4 Evaluating the antimicrobial effects

2.4.1 Microdilution method

Minium inhibitory concentrations of BiNPs and Bi subnitrate were determined by conventional microplate method [27]. Briefly, the 96‐well round‐bottom sterile microplates were separately filled with 180 µl of MHB supplemented with different concentrations of BiNPs (0.625–1280 µg/ml) and Bi subnitrate (0.625–1280 µg/ml) and 20 µl of the freshly prepared cultures of MRSA, P. aeruginosa, and P. mirabilis to obtain the final inoculums of 105 CFU/ml into each well. After overnight incubation at 37°C, 20 µl of the sterile TTC solution (0.5 mg/ml) was added to each well and incubated for an additional 2 h. The lowest concentration of the samples at which no visible red colour (due to the reduction of tetrazolium indicator into the related formazan) observed, was considered as MIC. The antibiotic ciprofloxacin (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was included in each assay as the positive control, while sterile MHB was applied as a negative control. All the experiments were repeated three times on different days and their means were reported.

2.4.2 Disc diffusion assay

Disc diffusion susceptibility test was carried out on MHA plates in order to examine the antibacterial activity of the BiNPs and Bi subnitrate, in combination with the selected antibiotics (as described in Section 2.1) against the clinical isolate of MRSA. Briefly, a single colony of MRSA was first grown overnight in MHB medium in a shaker incubator (37°C, 150 rpm) and the obtained culture was diluted (using sterile normal saline) to reach the 0.5 McFarland standard followed by its application on the surface of MHA plates using a swab to ensure the uniform distribution of MRSA. The standard antibiotic discs, blank discs containing only BiNPs (1000 µg/disc), or Bi subnitrate (1000 µg/disc), and antibiotic discs loaded with BiNPs (1000 µg/disc) or Bi subnitrate (1000 µg/disc) were then separately overlaid on the surface of the inoculated media followed by an overnight incubation at 37°C and measurement of the inhibition zones. The above‐mentioned disc diffusion method was performed in triplicate and the mean of the determined inhibition zones was reported.

2.4.3 Biofilm inhibition assay of biogenic BiNPs

The biofilm formed by the above‐mentioned strains (MRSA, P. aeruginosa, and P. mirabilis) was quantified by the microtitre method as described previously [28] with some modification. Briefly, one loopful of each strain was inoculated into sterile tryptic soy broth (TSB) medium (2 ml) containing glucose (1% w/v). Optical density (OD650) was then adjusted to 0.13 to reach 0.5 McFarland standard (1.5 × 108 CFU/ml) followed by further dilution of the prepared bacterial suspension to reach –106 CFU/ml and the addition of 100 µl of each prepared inoculums to 96‐well flat bottom tissue culture microplate. Similarly, 100 µl of the TSB medium containing BiNPs and Bi subnitrate was separately added to reach a concentration of 0.625 µg/ml and the microplate was then incubated at 37°C. After 24 h incubation, non‐adherent cell suspensions were aseptically removed, washed, and replaced with 10 µl of sterile phosphate‐buffered solution (pH 7.2) to remove any remaining suspended cells. To fix the biofilm, 150 µl of methanol was added to each well and kept at room temperature (25°C) for 20 min. Methanol was then removed and replaced with 200 µl of crystal violet solution (1% w/v). The wells containing biofilm matrix were slowly washed with sterile deionised water and kept at room temperature until drying. Thereafter, 200 µl of glacial acetic acid (33% v/v) was added to each well and the OD of each well was measured at 570 nm using Synergy2 multi‐mode microplate reader (BioTek, USA). All the experiments were carried out in triplicate and mean of the obtained results was reported.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The software SPSS 15 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago) was used for the statistical analysis and the differences between the groups were determined using one‐way analysis of variance. The p ‐values of <0.05 were considered as significant.

3 Results

3.1 Biosynthesis and characterisation of BiNPs

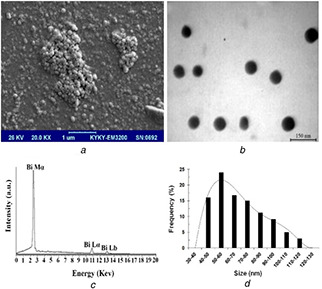

The culture medium of Delftia sp. SFG exhibited a gradual change in colour toward dark brown during 72 h incubation in the presence of Bi subnitrate (2 mg/ml), which indicated the reduction of Bi3+ ions to Bi0 NPs. The SEM image of biogenic BiNPs represented in Fig. 1 a revealed dispersion of nanostructures with some aggregation. The prepared TEM image showed spherical nanostructures (Fig. 1 b). Microanalysis of the purified BiNPs using EDX method represented Bi absorption peaks (BiMα, BiLα, and BiLb at 2.4, 10.8, and 13 keV, respectively) with weight per cent equal to 100 without other atom signals (Fig. 1 c). Also, BiNPs size distribution pattern was in size range of 40–120 nm and the most frequent particles were 59 nm (Fig. 1 d).

Fig. 1.

SEM image of biogenic BiNPs

(a) Scanning electron micrograph, (b) transmission electron micrograph, (c) energy dispersive X‐ray spectrum, (d) particle size distribution pattern of Bi NPs biosynthesized by Delftia sp. SFG

3.2 Antimicrobial activity of the BiNPs

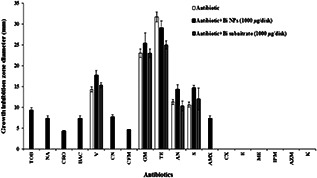

The serial dilution method was used to determine the MICs of the BiNPs and Bi subnitrate against different microbial pathogens. It was found that the MICs of BiNPs and Bi subnitrate against P. mirabilis, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa strains were above 1280 µg/ml. However, in the case of ciprofloxacin (CP), MIC was determined to be 0.125, 1, and 0.5 µg/ml for P. mirabilis, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa, respectively. Furthermore, the antibacterial activity of different antibiotics alone or in combination with a sub‐MIC amount of BiNPs (1000 µg/disc) or Bi subnitrate (1000 µg/disc) was investigated by disc diffusion method against the clinical isolate of MRSA (Fig. 2). The discs containing only the sub‐MIC amount of BiNPs or Bi subnitrate did not exhibit any inhibition zones against the MRSA. Among the tested antibiotics, only vancomycin, gentamicin (GM), tetracycline (TE), AN, and streptomycin were shown antibacterial effects against the tested MRSA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Antibacterial effect of different antibiotics alone and in combination with biogenic BiNPs or Bi subnitrate against MRSA. [TOB 10 µg/disc, NA 30 µg/disc, CRO 30 µg/disc, CP 5 µg/disc, BAC 0.04 unit/disc, vancomycin (V 30 µg/disc), CN 30 µg/disc, CFM 5 µg/disc, GM 10 µg/disc, TE 30 µg/disc, AN 30 µg/disc, streptomycin (S 10 µg/disc), AMX 25 µg/disc, CX 5 µg/disc, erythromycin (E 15 µg/disc), ME 5 µg/disc, IPM 10 µg/disc, AZM 15 µg/disc, kanamycin (K 30 µg/disc)]

3.3 Effect of BiNPs and Bi subnitrate on biofilm formation

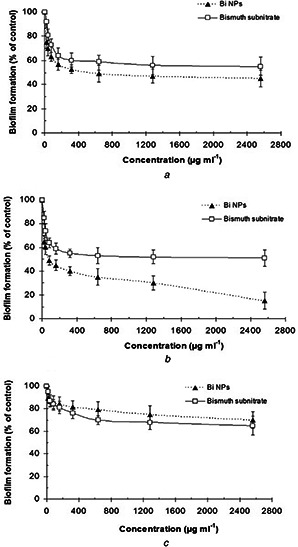

The anti‐biofilm activities of BiNPs and Bi subnitrate against S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and P. mirabilis species are summarised in Fig. 3. The biofilm formation by S. aureus was sharply decreased by increasing BiNPs and Bi subnitrate up to 2560 µg/ml and reached to 45 ± 6.9 and 55 ± 7.3%, respectively (Fig. 3 a). For P. aeruginosa, the amount of biofilm formation was dropped to 15 ± 2.9 and 51 ± 3.8% in the presence of BiNPs and Bi subnitrate (0–16 µg/ml), respectively (Fig. 3 b). In the case of P. mirabilis treated with BiNPs and Bi subnitrate, biofilm formations were decreased to 85 ± 6.3 and 84 ± 4.2%, respectively, and remained constant at the concentration above 80 µg/ml (Fig. 3 c). Fig. 4 compared the biofilm formations by S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and P. mirabilis strains treated with BiNPs and Bi subnitrate.

Fig. 3.

Anti‐biofilm activity of BiNPs and Bi subnitrate against

(a) S. aureus, (b) P. aeruginosa, (c) P. mirabilis. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3). Wells containing above bacteria in the absence of BiNPs and Bi subnitrate were designed as a control

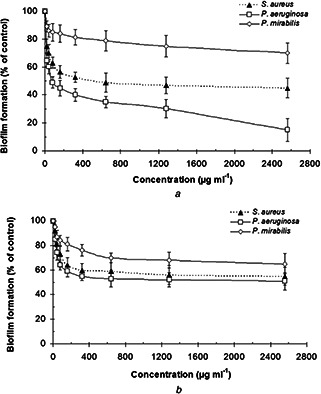

Fig. 4.

Biofilm formation by S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and P. mirabilis treated with different concentrations (0.625–2560 µg/ml) of

(a) Biogenic BiNPs, (b) Bi subnitrate. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Wells containing above bacteria in the absence of BiNPs and Bi subnitrate were designed as a control

4 Discussion

Nowadays, using the nanostructures holds much promise for biomedical applications and overcoming the microbial resistance [28]. In this work, we studied compelling evidence of the ability of biogenic BiNPs prepared by Delftia sp. SFG as a new antibacterial and anti‐biofilm agents. The inhibitory effect of the prepared biogenic BiNPs (40–120 nm) and Bi subnitrate on clinical strains of P. mirabilis, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa was not different from each other and the measured MICs were above 1280 µg/ml. Reviewing the literature has revealed that biosyntheses of Te NPs and SeNPs by microbial reduction of potassium Te and sodium selenite led to toxicity decrease of the produced NP. For example, in the study of Shakibaie et al. [16], the toxic effect of biogenic Te NPs prepared by P. pseudoalcaligenes Te on P. mirabilis, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa was reported lower than potassium Te. In the study of Forootanfar et al. [29], the cytotoxicity of SeNPs prepared by Bacillus sp. MSh‐1 was significantly lower than selenium dioxide on MCF‐7 cell line (p < 0.05). In contrast, Nazari et al. [30] previously reported that the MICs of biogenic BiNPs (<5 nm) prepared by Serratia marcescens against different clinical isolates of H. pylori ranged from 60 to 100 μg/ml, and at concentrations <280 μg/ml of Bi subnitrate no antibacterial effect was observed. They concluded that the antibacterial effect of BiNPs against H. pylori was higher than the anti‐H. pylori effect of Bi subnitrate. It seems that sensitivity of facultative anaerobe bacteria such as H. pylori to BiNPs and Bi compounds was more than other bacterial strains such as P. mirabilis, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa. Furthermore, Flores‐Castañeda et al. [31] reported that better antibacterial properties of Bi subsalicylate NPs (20–60 nm) produced by laser ablation could be achieved with the smaller size of Bi subsalicylate NPs (below 20 nm). It seems that the higher size of Bi containing NPs, the lower antibacterial activity could be observed.

In the present paper, the discs containing only BiNPs or Bi subnitrate (1000 µg/disc) did not exhibit any inhibition zones against the MRSA (Fig. 2). It might be attributed to the low solubility of the BiNPs or Bi subnitrate and as a result limitation of diffusion of this Bi containing compound through the culture media and exhibition of antimicrobial activity. One way to overcome the microbial resistance to antibiotics is the usage of antibiotics in combination with various nanostructures [30]. As an instance, Shahverdi et al. [32] reported the enhancement effect of AgNPs on the antibacterial activity of different antibiotics against S. aureus and E. coli. Furthermore, zinc oxide NPs enhanced the antibacterial activity of CP against S. aureus and E. coli [33]. The obtained results of the present paper revealed no considerable change of antibacterial activity of Bi subnitrate in combination with vancomycin, GM, AN, and streptomycin against the tested MRSA (Fig. 2). In addition, Bi subnitrate significantly decreased the antibacterial effect of TE against the tested MRSA (p < 0.05). In contrast to Bi subnitrate–antibiotics combination effects, the combination of BiNPs with TOB, NA, CRO, BAC, CN, CFM, gentamycin, TE, and AMX revealed enhancement in antibacterial properties of mentioned antibiotics against the tested MRSA (Fig. 2). Growth inhibition zone diameter of vancomycin, AN, and streptomycin discs containing BiNPs was significantly higher than each antibiotic alone (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Interestingly, BiNPs enhanced the effect of antibiotics that interfere with cell wall and peptidoglycan synthesis (CRO, CN, CFM, AMX, and BAC) which did not show inhibitory effect on MRSA alone. Furthermore, BiNPs significantly increased the growth inhibition zone of TOB (a protein synthesis inhibitor) and NA (a DNA gyrase inhibitor) against MRSA (p < 0.05). Growth inhibition zone diameter of vancomycin or AN disc containing BiNPs was significantly higher than disc containing vancomycin or AN and Bi subnitrate or vancomycin and AN disc (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Using nanostructures is one way for inhibition of biofilm formation and destruction of biofilm which is one of the most important causes of developing resistant microbial strains to common antibiotics [1]. For example, AgNPs (50 µg/ml) completely inhibited biofilm formation of E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae [34]. Furthermore, biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa and S. epidermidis was reduced to 2–5% in the presence of AgNPs (100 nM) [35]. Hernandez‐Delgadillo et al. [36] reported that chemically synthesised zerovalent BiNPs (3.3 nm) completely prevented biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans. A literature review revealed no reports on the anti‐biofilm activity of biogenic BiNPs. Results of the present paper showed that the effect of zerovalent biogenic BiNPs on biofilm formation by S. aureus and P. mirabilis was not significantly higher than that of Bi subnitrate (as Bi3+ ion source) at a concentration of 0.625–1280 µg/ml (p > 0.05) (Figs. 3 a and c). However, the anti‐biofilm activities of biogenic BiNPs on P. aeruginosa were significantly higher than that of Bi subnitrate at a concentration above 80 µg/ml (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3 b). Previously, Shakibaie et al. [1] reported similar effects of biogenic zerovalent SeNPs on biofilm formation by P. mirabilis, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa which was not significantly higher than that of Se dioxide (as Se+4 ion source) (p > 0.05). Hernandez‐Delgadillo et al. [36] reported that the antifungal effect of chemically synthesised Bi2 O3 NPs (77 nm) against Candida albicans was two‐fold better when compared with the bulk Bi2 O3 and Bi nitrate pentahydrate. Furthermore, Bi2 O3 NPs have an anti‐biofilm activity similar to those of chlorhexidine and terbinafine which completely inhibit biofilm formation of C. albicans. They suggested that most of C. albicans cells were inactivated during inoculation with Bi2 O3 NPs and surviving treated cells which were into planktonic and stress states were not sufficient for biofilm formation [36]. In contrast, the biogenic BiNPs prepared in the present paper was not completely inhibited biofilm formation in the culture media of P. mirabilis, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa (Fig. 3). It seems that the chemical composition of Bi containing nanostructures and type of treated pathogen have a critical role for inhibition of biofilm formation.

In this paper, the anti‐biofilm activity of biogenic BiNPs at a sub‐MIC concentration (80–1280 µg/ml) on biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa was higher than that of P. mirabilis and S. aureus; and this effect was significant (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4 a). The anti‐biofilm effect of Bi subnitrate on P. aeruginosa was higher than P. mirabilis and S. aureus but this was not a significant effect (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4 b). Furthermore, the anti‐biofilm activity of BiNPs on biofilm formation by S. aureus was significantly higher than P. mirabilis (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4 a). The effect of Bi subnitrate on biofilm formation by S. aureus was higher than P. mirabilis but this was not a significant effect (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4 b). Usually, the similar antimicrobial concentration of common antimicrobial agents requires for anti‐biofilm effects against planktonic culture [37]. However, Huang and Stewart [38] suggested it might be possible that Bi containing compounds such as Bi dimercaprol (BisBAL) adsorbed by biofilms and local concentration that lead to bactericidal and anti‐biofilm effect was higher than MIC. Domenico et al. [39] reported that capsular polysaccharide expression by P. aeruginosa and K. pneumonia was inhibited by Bi compounds at sub‐MIC concentration. It has been reported that the MIC concentration of BisBAL was not sufficient to kill all attached cells but it was enough for inhibition of polysaccharide expression and biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa ERC1. Badireddy et al. [4] reported that chemically synthesised BisBAL NPs significantly inhibited S. mutans growth at a concentration of 10 µM. They suggested that based on lipophilic nature of BisBAL NPs, it is possible that they interact with the plasma membrane and causing cellular lysis by alteration of the permeability of the bacteria. Furthermore, BisBAL NPs might modify protein expression, altering cell metabolism, and damage the genomic DNA [4]. However, the anti‐biofilm mechanism of the biogenic BiNPs prepared in the present paper was not clear and merits further studies.

5 Conclusion

The obtained results of disc diffusion method revealed valuable coordinative enhancement in antibacterial activity of different commonly used antibiotics against MRSA by biogenic BiNPs. This combination was significantly higher than Bi subnitrate–antibiotics combination. In the cases of seven antibiotics including TOB, NA, CRO, BAC, CN, AMX, and CFM addition of BiNPs resulted in the appearance of antibacterial effects. According to the obtained results, biogenic BiNPs indicated remarkable anti‐biofilm activity against P. aeruginosa. Also, the anti‐biofilm activities of BiNPs against two other species were approximately as same as Bi subnitrate. Although, this work showed the potency of BiNPs prepared by Delftia sp. SFG for using as an anti‐biofilm agent, further studies are needed for finding the action mechanism of these NPs against microbial biofilms.

6 Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by Elite Researcher Grant Committee under award number from the National Institutes for Medical Research Development (NIMAD, 977612), Tehran, Iran. Deputy of Research, Kerman University of Medical Sciences (Kerman, Iran) has also supported this work (Grant no. 94/387). We thank the Herbal and Traditional Medicines Research Center, Kerman University of Medical Sciences (Kerman, Iran), and Iranian Nanotechnology Initiative Council for their admirable participation in this paper.

7 References

- 1. Shakibaie M. Forootanfar H. Golikari H. et al.: ‘Anti‐biofilm activity of biogenic selenium nanoparticles and selenium dioxide against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Proteus mirabilis ’, J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol., 2014, 29, pp. 235 –241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Qayyum S. Sharma D. Bisht D. et al.: ‘Protein translation machinery holds a key for transition of planktonic cells to biofilm state in Enterococcus faecalis: a proteomic approach’, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 2016, 474, (4), pp. 652 –659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coenye T.: ‘In vitro and in vivo model systems to study microbial biofilm formation’, J. Microbiol. Methods, 2010, 83, (2), pp. 89 –105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Badireddy A.R. Hernandez‐Delgadillo R. Sánchez‐Nájera R.I. et al.: ‘Synthesis and characterization of lipophilic bismuth dimercaptopropanol nanoparticles and their effects on oral microorganisms growth and biofilm formation’, J. Nanoparticle Res., 2014, 16, (6), pp. 24 –56 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mack D. Davies A.P. Harris L.G. et al.: ‘Staphylococcus epidermidis in biomaterial‐associated infections’. In (Eds.): ‘Biomaterials associated infection’, (Springer, New York, USA, 2013), pp. 25 –56 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fazeli H. Akbari R. Moghim S. et al.: ‘ Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in patients, hospital means, and personnel's specimens’, J. Res. Med. Sci., 2012, 17, (4), pp. 332 –337 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olaniyi R. Pozzi C. Grimaldi L. et al.: ‘ Staphylococcus aureus ‐associated skin and soft tissue infections: anatomical localization, epidemiology, therapy and potential prophylaxis’, Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol., 2016, 409, pp. 199 –227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hannan T. Totsika M. Mansfiels K.J. et al.: ‘Host–pathogen checkpoints and population bottlenecks in persistent and intracellular uropathogenic Escherichia coli bladder infection’, FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 2012, 36, (3), pp. 616 –648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moshafi M.H. Forootanfar H. Ameri A. et al.: ‘Antimicrobial activity of Bacillus sp. strain FAS1 isolated from soil’, Pak. J. Pharm. Sci., 2011, 24, (3), pp. 269 –275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Falagas M.E. Fragoulis K.N. Karydis I. et al.: ‘A comparative study on the cost of new antibiotics and drugs of other therapeutic categories’, PLoS One, 2006, 1, (1), pp. 11 –16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mu H. Tang J. Liu Q. et al.: ‘Potent antibacterial nanoparticles against biofilm and intracellular bacteria’, Sci. Rep.UK, 2016, 6, pp. 18 –31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Forootanfar H. Amirpour‐Rostami S. Jafari M. et al.: ‘Microbial‐assisted synthesis and evaluation the cytotoxic effect of tellurium nanorods’, Mater. Sci. Eng. C, Mater. Biol. Appl., 2015, 49, pp. 183 –189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Soflaei S. Dalimi A. Abdoli A. et al.: ‘Anti‐leishmanial activities of selenium nanoparticles and selenium dioxide on Leishmania infantum ’, Comparative Clin. Pathol., 2014, 23, pp. 15 –20 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hosseini M. Mashreghi M. Eshghi H.: ‘Biosynthesis and antibacterial activity of gold nanoparticles coated with reductase enzymes’, IET Microw. Nano Lett., 2016, 11, (9), pp. 484 –489 [Google Scholar]

- 15. González F. Blázquez M.L. Muñoz J.A. et al.: ‘Biological synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using algae’, IET Nanobiotechnol., 2013, 7, (3), pp. 109 –116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shakibaie M. Adeli‐Sardou M. Mohammadi‐Khorsand T. et al.: ‘Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of the biologically synthesized tellurium nanorods; a preliminary in vitro study’, Iran. J. Biotechnol., 2017, 15, (4), pp. 268 –276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soflaei S. Dalimi A. Ghaffarifar F. et al.: ‘In vitro antiparasitic and apoptotic effects of antimony sulfide nanoparticles on Leishmania infantum ’, J. Parasitol. Res., 2012, 2012, p. 756568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shakibaie M. Mohazab N.S. Ayatollahi Mousavi S.A. et al.: ‘Antifungal activity of selenium nanoparticles synthesized by Bacillus species Msh‐1 against Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans ’, Jundishapur J. Microbiol., 2015, 8, p. e26381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Le O.B. Ouay F.S.: ‘Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: a surface science insight’, Nanotoday, 2015, 10, (3), pp. 339 –354 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nguyen T. Vardhanabhuti B. Lin M. et al.: ‘Antibacterial properties of selenium nanoparticles and their toxicity to CaCO‐2 cells’, Food Control, 2017, 77, pp. 17 –24 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shoeibi S. Mashreghi M.: ‘Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using Enterococcus faecalis and evaluation of their antibacterial activities’, J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol., 2017, 39, pp. 135 –139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bahri‐Kazempour Z. Abdi K. Shakibaie M. et al.: ‘Synthesis and antibacterial activity of a Fe3 O4 –AgCl nanocomposite against Escherichia coli ’, Toxicol. Environ. Chem., 2012, 95, (1), pp. 118 –126 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chagnon M.J.: ‘Bismuth and bismuth alloys’, Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2010), pp. 1 –14 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diemert D.J.: ‘Prevention and self‐treatment of travelers’ diarrhea’, Prim. care, 2002, 29, (4), pp. 843 –855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jassim A. Farhan S. Salman J. et al.: ‘Study the antibacterial effect of bismuth oxide and tellurium nanoparticles’, Int. J. Chem. Biomol. Sci., 2015, 1, pp. 81 –84 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ding L. Zhao Q. Zhu J. et al.: ‘The preparation and property research of bismuth oxide nanospheres’, International Conference on Materials Chemistry and Environmental Protection (MEEP 2015), Lanzhou, China, 2015, pp. 17 –20 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pitz A. Park G. Lee D. et al.: ‘Antimicrobial activity of bismuth subsalicylate on Clostridium difficile, Escherichia coli O157:H7, norovirus, and other common enteric’, Gut Microbes, 2015, 6, (2), pp. 93 –100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hernandez‐Delgadillo R. Velasco‐Arias D. Diaz D. et al.: ‘Zerovalent bismuth nanoparticles inhibit Streptococcus mutans growth and formation of biofilm’, Int. J. Nanomed., 2012, 7, pp. 2109 –2113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Forootanfar H. Adeli‐Sardou M. Nikkhoo M. et al.: ‘Antioxidant and cytotoxic effect of biologically synthesized selenium nanoparticles in comparison to selenium dioxide’, J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol., 2014, 28, (1), pp. 75 –79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nazari P. Dowlatabadi‐Bazaz R. Mofid M.R. et al.: ‘The antimicrobial effects and metabolomic footprinting of carboxyl‐capped bismuth nanoparticles against Helicobacter pylori ’, Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol., 2014, 172, (2), pp. 570 –579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Flores‐Castañeda M. Vega‐Jiménez A.L. Almaguer‐Flores A. et al.: ‘Antibacterial effect of bismuth subsalicylate nanoparticles synthesized by laser ablation’, J. Nanoparticle Res., 2015, 17, (11), p. 431 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shahverdi A. Fakhimi A. Shahverdi H.R et al.: ‘Synthesis and effect of silver nanoparticles on the antibacterial activity of different antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli ’, Nanomedicine, 2007, 3, (2), pp. 168 –171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Banoee M. Seif S. Nazari Z.E. et al.: ‘ZnO nanoparticles enhanced antibacterial activity of ciprofloxacin against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli ’, J. Biomed. Mater. Res., 2010, 93B, (2), pp. 557 –561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ansari M.A. Khan H.M. Khan A.A. et al.: ‘Antibiofilm efficacy of silver nanoparticles against biofilm of extended spectrum β ‐lactamase isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae ’, Appl. Nano Sci., 2014, 4, (7), pp. 859 –868 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kalishwaralal K. BarathManiKanth S. Pandian S.R. et al.: ‘Silver nanoparticles impede the biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus epidermidis ’, Colloids Surf. B, Biointerfaces, 2010, 1, (79), pp. 340 –344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hernandez‐Delgadillo R. Velasco‐Arias D. Martinez‐Sanmiguel J.J. et al.: ‘Bismuth oxide aqueous colloidal nanoparticles inhibit Candida albicans growth and biofilm formation’, Int. J. Nanomed., 2013, 8, pp. 1645 –1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim J. Pitts B. Stewart P.S. et al.: ‘Comparison of the antimicrobial effects of chlorine, silver ion, and tobramycin on biofilm’, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 2008, 52, (4), pp. 1446 –1453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huang C.T Stewart P.S.: ‘Reduction of polysaccharide production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms by bismuth dimercaprol (BisBAL) treatment’, J. Antimicrob. Chemother., 1999, 44, (5), pp. 601 –605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Domenico P. Landolphi D.R. Cunha B.A.: ‘Reduction of capsular polysaccharide and potentiation of aminoglycoside inhibition in gram‐negative bacteria by bismuth subsalicylate’, J. Antimicrob. Chemother., 1991, 28, (6), pp. 801 –810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]