Abstract

Based on the enhancement of synergistic antitumour activity to treat cancer and the correlation between inflammation and carcinogenesis, the authors designed chitosan nanoparticles for co‐delivery of 5‐fluororacil (5‐Fu: an as anti‐cancer drug) and aspirin (a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug) and induced synergistic antitumour activity through the modulation of the nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐κB)/cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) signalling pathways. The results showed that aspirin at non‐cytotoxic concentrations synergistically sensitised hepatocellular carcinoma cells to 5‐Fu in vitro. It demonstrated that aspirin inhibited NF‐κB activation and suppressed NF‐κB regulated COX‐2 expression and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) synthesis. Furthermore, the proposed results clearly indicated that the combination of 5‐Fu and aspirin by chitosan nanoparticles enhanced the intracellular concentration of drugs and exerted synergistic growth inhibition and apoptosis induction on hepatocellular carcinoma cells by suppressing NF‐κB activation and inhibition of expression of COX‐2.

Inspec keywords: proteins, molecular biophysics, cellular biophysics, biomedical materials, cancer, nanoparticles, drug delivery systems, enzymes, tumours, nanomedicine, drugs

Other keywords: chitosan nanoparticles, aspirin, 5‐fluororacil, synergistic antitumour activity, anticancer drug, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug, hepatocellular carcinoma cells, NF‐κB activation, NF‐κB regulated COX‐2 expression, PGE2, synergistic growth inhibition, apoptosis induction, prostaglandin E2 synthesis, intracellular concentration, noncytotoxic concentrations, NF‐κB‐cyclooxygenase‐2 signalling pathways, cyclooxygenase‐2, nuclear factor kappa B

1 Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents the most highly angiogenic solid tumours in the world. From a molecular standpoint, it is characterised molecularly by cell‐cycle dysregulation, aberrant angiogenesis, and the evasion of apoptosis [1, 2, 3, 4]. As HCC development is distinct from other types of cancer, hepatic cirrhosis postoperative recurrence and metastasis are often induced after liver resection. Therefore, one or more anti‐cancer drugs (chemotherapeutic agents) are typically applied to damage or stress HCC cells, which may then lead to cell death [5, 6, 7]. However, due to poor selectivity and drug resistance, the sensitivity to anti‐mitotic drugs in HCC cells was highly reduced following a period of drug exposure and the effective dosage had to be amplified to attain the desired treatment effect, thus causing highly a series of serious side effects, including myelosuppression, mucositis, and alopecia [8, 9, 10]. Therefore, it was urgent to explore a measure to inhibit the resistance of drug and synergistically sensitise the cells to drugs while attenuating side effects.

It is well recognised that inflammation plays an important role in cancer occurrence and metastasis of cancer [11, 12, 13]. One of the possible links between inflammation and malignancy might be cyclooxygenase 2 (COX‐2) which is highly expressed in a number of human malignancies including lung, colorectal, prostate, and breast cancer, as well as HCC [14, 15, 16]. COX‐2 converts arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), thus contributing to promotion of cell proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis [17, 18, 19, 20]. Furthermore, COX‐2 inhibitor was reported to inhibit the cell migration and induce cell apoptosis in human HCC cells by downregulating its levels of COX‐2. The addition of PGE2, a major product of COX‐2, might abrogate the anti‐tumour effects [21]. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been reported to inhibit the activation of the NF‐κB pathway. Additionally, NF‐κB has been shown to regulate the expression of COX‐2 in cancer cells [22]. It was reported that transcription factor NF‐κB was suppressed by NSAIDs and controlled the expression of genes of COX‐2 leading to inhibition of proliferation of tumour cells [23]. Herein, it indicated that NSAIDs may potentiate anti‐tumour effect by regulating NF‐κB/COX‐2/PGE2.

In modern medicine, especially in the treatment of cancer, combination therapy is now a trend in cancer treatment [24, 25, 26, 27]. In virtue of the occurrence of acquired drug resistance, it is inevitable to increase drug efficacy by infinitely increasing their doses, thereby, a considerable amount of anti‐cancer drugs would cause serious toxic side effects and even endanger the patient's life. Combined administration of two or more drugs aims to investigate the possible applications of traditional anti‐cancer drugs and non‐toxic chemical substances could act on multiple therapeutic targets to treat cancer, thus reducing the drug resistance level and enhancing synergistic antitumour efficacy.

Nanoparticles (NPs) have been used as a novel drug and gene delivery system for the targeted therapy of human cancers [28, 29]. Compared with traditional drug delivery system, NPs are more likely to accumulate in the interior of solid tumour for a longer time and encapsulate more drugs or different kinds of drugs at the same time, thus improving synergistic antitumour activity of drugs. In this study, we used the combination of the NSAID aspirin and the anticancer drug 5‐Fluorouracil (5‐Fu) to exert the synergistic antitumour efficacy. Both drugs were well encapsulated in chitosan NPs (CNs) to obtain 5‐Fu/aspirin‐loaded CNs (5‐FACN). These drug‐loaded CNs were delivered into HCC cells to evaluate the synergistic antitumour effects of 5‐Fu and aspirin. The inhibition rates of 5‐Fu and aspirin on HCC cell lines (HepG2 and SMMC‐7721) were determined by MTT method. The cell‐cycle behaviour of SMMC‐7721 cell lines was analysed by fluorescent‐activated cell sorting application, while the expressions of apoptosis‐related proteins, COX‐2 and NF‐κB were detected by western blotting method.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

5‐Fu was obtained from Jinghua Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd (Nantong, People's Republic of China). Chitosan (CS) of medium molecular weight (deacetylation degree, 80%; molecular weight, 400,000) was purchased from Haixin Biological Product Co., Ltd. (Zhejiang, People's Republic of China). Aspirin and rhodamine B (RhB) were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). HCC cell lines (HepG2 and SMMC‐7721) were purchased from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, People's Republic of China).

2.2 Preparation and characterisation of 5‐FACN

According to our previous reports [30, 31], 5‐Fu and aspirin‐loaded CNs (5‐FACN) were prepared by the ion‐crosslinking method. A certain amount of 5‐Fu and aspirin were pre‐dissolved in CS solution and the pH level was adjusted to 4 with 0.01 mol/l of NaOH solution under stirring at a certain speed. Sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) solution as an ionic polymerisation agent was dropped slowly into CS under stirring until obvious opalescence appeared. The obtained NPs were purified by double washing and centrifugation, and they were further freeze dried to powders. The shape of NPs was observed using a JEM‐1200EX transmission electron microscope (TEM) and their particle size and zeta potential were also determined by the help of a Nano Zetasizer 90. The encapsulation efficiency of drugs in CNs was determined by measuring the difference between the initially added drug amount and drug amount in the supernatant. The release properties of drugs from CNs were investigated on the basis of a dialysis method in vitro. Accurate weighed dried free drugs and drug‐loaded NPs were wrapped in a dialysis bag (spectrum, USA) with 1000 molecular weight and immersed into 100 ml phosphate buffer solution (pH = 5.8, 7.4) at 37.0±0.5°C under gentle agitation. About 5 ml of release medium was withdrawn at each specified time point, and the same volume of fresh buffer solution was added into the release medium to maintain the constant volume. Samples were filtered through 0.45 μm filter and the content of aspirin and 5‐Fu was further determined spectrophotometrically.

2.3 Distribution of NPs in cells

RhB as a fluorescent marker showed a red fluorescent colour and was encapsulated in CNs. About 2 mg of RhB powder was mixed into the CS solution followed by the slow addition of TPP to obtain RhB‐labelled NPs. Free RhB absorbing at the surface of RhB‐labelled NPs was removed by washing with distilled water. Confluent SMMC‐7721 cells and HepG2 cells (5 × 104 /ml) were added onto a confocal microscopic dish for continuous culture for 24 h. Next, RhB‐labelled NPs were inserted into the cell dish for incubating cells. The intracellular distribution of RhB‐labelled NPs was observed with aid of confocal laser scanning microscopy at different time points. The uptake rate of NPs was represented by checking the emitting fluorescence intensity of RhB and the uptake ratio (UR, %) was calculated using the equation below with a microplate reader

| (1) |

FItotal is initial intensity of fluorescence emitted by free RhB or RhB‐labelled NPs, FIinternalised is intensity of fluorescence emitted by intracellular free RhB or RhB‐labelled NPs.

2.4 MTT assay

HepG2 and SMMC‐7721 cells were seeded in 96‐well plates at 100 μl cells/well and maintained to adherence at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, 95% air. The suspensions of free 5‐Fu, free aspirin, 5‐Fu‐loaded CNs (5‐FCN), and 5‐FACN were added into the well, respectively, for co‐incubation with cells. After 48 h, the culture medium was removed followed by the addition of 200 μl MTT (0.2 mg/ml). Following this, 100 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide was added into each well to dissolve the crystals. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader (Synery‐2; BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). All experiments were performed thrice.

2.5 Cell‐cycle analysis by flow cytometry

Based on the previous study [32], drug‐loaded NPs mediated cell progression was explored using flow cytometry. Cells (5 × 105 cells/well) were incubated into a six‐well plate for 24 h. With the removal of original culture medium, serum‐free medium containing free aspirin at 0.5 mM, 5‐FCN, 5‐FACN and the combination of 5‐FCN and free aspirin having the same amount of 5‐Fu at 20 μg/ml was added into the wells, respectively. After 24 h, the cells were harvested and resuspended at 5 × 105 cells in 1 ml of ice‐cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) in an eppendorf tube followed by the slow addition of 3 ml of ice‐cold 100% ethanol while gently vortexing the sample. Finally, cells were collected and the phase progression in cells cycle was evaluated by flow cytometry.

2.6 Western blot assay

According to our previous study [30], free 5‐Fu, 5‐FCN, free aspirin, and 5‐FCN having the same dose of 5‐Fu were used to treat SMMC‐7721 cells for 48 h and western blot assay was performed. The relative band density (RBD) of target protein in test groups was calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

RRt is relative ratio of target protein to internal reference protein in test groups, RRC is relative ratio of target protein to internal reference protein in untreated cells as the control group.

3 Results

3.1 Preparation and characteristics determination of NPs

Two drops of suspensions containing CN and 5‐FACN were placed on the carbon film with a copper grid and naturally dried for 3–5 min. The morphology of NPs was observed using a JEM‐1200EX TEM. As can be seen in Fig. 1, CN and 5‐FACN showed uniform particle size distribution and regular spherical or sphere‐like shapes. The average particle sizes of CN and 5‐FACN were 104.7 ± 3.2 and 109.2 ± 5.2 nm, respectively. The average zeta potentials were 13.9 ± 3.2 and 14.2 ± 3.7 mV. The drug encapsulation efficiencies of 5‐Fu and aspirin were 88.6 and 91.0%, respectively. 5‐FACN showed a prolonged biphasic release pattern. The release rates of free 5‐Fu and aspirin were faster and most of free drugs were almost completely released within 4 h. CNs as a drug carrier controlled the drug‐release rate characterised by the initial rapid burst release and a sustained release. The release percentages of aspirin and 5‐Fu in 5‐FACN were 28.5 and 29.8% within the first 4 h, and those of aspirin and 5‐Fu were 77.5 and 75.4% within 24 h in PBS (pH 7.4), respectively. We also investigated the accumulative release of 5‐FACN and free drugs in tumour acidic condition (pH 5.8). We found that there was no significant change on the release rate of free 5‐Fu and aspirin under different pH conditions (pH 5.8 and 7.4). On the contrary, drug‐loaded CNs showed a pH‐dependent release pattern and was released rapidly at lower pH conditions but slowly at physical condition. This would be a benefit for smart release of drugs in normal physical condition and acidic condition around tumour cells.

Fig. 1.

Characterisation of 5‐FACN

(a) TEM images of CN and 5‐FACN, (b) DLS analysis of NPs, (c) Accumulative release of 5‐FACN and free drugs in PBS (pH 7.4 and 5.8), mean ± SD (n = 3). Scale bar: 100 nm

3.2 Distribution of NPs in cells

The results showed that when incubated with SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells, RhB‐labelled NPs (red spots) were primarily accumulated in the cytoplasm surrounding the nucleus, and over time, the cell uptake of NPs was gradually increased (Figure 2). This inferred that NPs could be transferred into cells and mainly distributed in the cytoplasm. Free RhB as a substitute of free drug may cross cell membrane to penetrate into the cells by passive diffusion, and the uptake ratio was limited by the concentration gradient, thus resulting in a lower uptake. The uptake ratio of free RhB observed in the cells ranged gradually from 30.4 and 24.3% at 3 h to about 52.3% and 50.3 at 9 h in SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells. In contrast, more RhB could be delivered into the cells upon mediation of the cellular internalisation of NPs, thus showing higher uptake. The uptake ratio of RhB‐labelled NPs was enhanced from 50.2 and 46.5% in the initial 3 h to over 80.2 and 73.4% at 9 h in SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells.

Fig. 2.

Confocal images of RhB‐labelled NPs at 6 h and uptake ratio of free RhB and RhB‐labelled NPs in SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells. Results are expressed as means ± standard deviation (n = 3). *P < 0.05

3.3 MTT assay

The MTT results shown in Fig. 3 a demonstrated that the viability ratios of cells treated with naked CNs at 70–840 μg/ml were over 90% within 48 h, indicating that naked CNs did not induce the obvious effect on the cell viability and showed negligible cytotoxicity. We also detected the effect of different concentrations of aspirin (0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10.0 mM) on the proliferation of HCC cells. Aspirin was added into the cultures of SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells for 48 h and MTT was used to determine its cytotoxicity. As shown in Fig. 3 b, aspirin concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 2 mM did not exhibit obvious inhibitory effects on the proliferation of cells, therefore we chose non‐cytotoxic concentrations of aspirin (0.1 and 0.5 mM) and combined with 5‐Fu to evaluate its synergistic antitumour activity. The inhibiting effect of different concentrations of 5‐Fu (5.0, 10.0, 20.0, 40.0, 60.0 μg/ml) and 5‐FCN on the proliferation of SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells was investigated by MTT assay. Fig. 3 b also showed that 5‐FCN and free 5‐Fu inhibited the growth of SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells. With increased drug concentrations, the inhibitory effect of 5‐FCN and 5‐Fu was enhanced. When compared with free 5‐Fu, the inhibitory effect of 5‐FCN on SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells was stronger after 48 h of drug treatment. The half‐maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 5‐Fu and 5‐FCN on HCC SMMC‐7721 cells for 48 h were 36.05 and 24.82, 28.96 μg/ml for 5‐Fu and 21.38 μg/ml for 5‐FCN on HCC HepG2 cells.

Fig. 3.

Viability of SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells treated by different formulations

(a) Viability of CNs treated SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells, (b) Viability of SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells treated with 5‐FCN, 5‐Fu and free aspirin, (c) Viability of SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells treated with 5‐FCN and the combination of 5‐FCN and aspirin. Results are expressed as means ± standard deviation (n = 3), *P < 0.05, (d) Viability of SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells after incubation with 5‐FACN and the combination of 5‐FCN and aspirin with the same concentration of aspirin at 0.1 and 0.5 mM. Results are expressed as means ± standard deviation (n = 3). *P < 0.05, # P < 0.05, comparing with control. & P < 0.05

The results in Fig. 3 c show that when compared with 5‐FCN alone, the combination of 5‐FCN and aspirin (0.1, 0.5 mM) for 48 h had a higher inhibitory rate on the cell growth of SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells, indicating that the addition of aspirin synergistically enhanced the antitumour effects of 5‐Fu; moreover, the cytotoxicity of 5‐Fu was significantly improved on aspirin‐dosage dependent pattern. Finally, the inhibiting rate of HCC SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells treated with 5‐FACN and the combination of 5‐FCN and free aspirin for 48 h were compared. As shown in the results of Fig. 3 d, the inhibitory rates of SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells treated with the combination of 5‐FCN and free aspirin at 0.5 mM were 51.24 and 63.01%. The inhibitory rates of SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells treated with 5‐FACN were 66.02 and 75.17%. The results showed that NPs packed with 5‐Fu and aspirin showed the highest cytotoxicity and induced cell apoptosis.

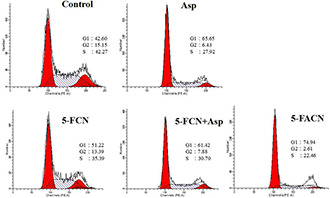

3.4 Cell‐cycle analysis

It is well known that the cell cycle arrest may affect the cell proliferation. On this context, we investigated whether 5‐FACN could regulate cell cycle progression by flow cytometry. The results in Fig. 4 showed that aspirin changed the phase progression of SMMC‐7721 cells and maintained cell stagnation in the G1 phase. Compared with 5‐FCN group, the addition of aspirin significantly led to G1‐phase arrest and decreased cell percentage of S‐phase and G2‐phase in 5‐FCN + Asp and 5‐FACN groups. The cell percentage in G1‐phase was markedly increased in 5‐FCN + Asp and 5‐FACN groups compared with 5‐FCN group (61.42 and 74.94% compared with 51.22%). On the other hand, compared with the percentages of S‐phase and G2‐phase (35.39 and 13.39%) in 5‐FCN group, cell population of S‐phase and G2‐phase were significantly decreased in 5‐FCN + Asp (30.70 and 7.88%) and 5‐FACN groups (22.46 and 2.61%). Cell‐cycle analysis suggested that aspirin arrested the cell cycle in phase G1 and it also strengthened the 5‐Fu‐mediated G1‐phase accumulation and reduced cells proportions in S‐phase and G2‐phase. It proved that aspirin can produce a strong synergistic effect on the growth inhibition of cells when administered in combination with 5‐Fu.

Fig. 4.

Cell cycle progression in SMMC‐7721 cell lines treated with free aspirin, 5‐FCN, 5‐FACN and the combination of 5‐FCN and free aspirin for 24 h by flow cytometry

3.5 Western blot assay

Result in Fig. 5 a showed that after treated with free aspirin at the concentrations of 0.1 and 0.5 mM, the expression levels of NF‐κB p65 were significantly down‐regulated, indicating that NF‐κB activation was inhibited by aspirin in a dose‐dependent manner. We also further determined whether aspirin inhibited NF‐κB ‐regulated COX‐2 expression and found that aspirin blocked NF‐κB‐regulated COX‐2 expression in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 5 b). As PGE2 as the main product of arachidonic acid catalysed by COX‐2 was closely related to the expression and activity of COX‐2, we investigated the correlation between the blocking of COX‐2 and suppression of PGE2 synthesis. When SMMC‐7721 cells were treated with free aspirin at concentrations of 0.1 and 0.5 mM for 48 h, the level of PGE2 in the supernatant of the cells was determined by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Fig. 5 c showed that when compared with the control group, aspirin reduced the content of PGE2 and the concentration of PGE2 gradually decreased with increasing concentrations of aspirin. It was found in Fig. 5 c that aspirin suppressed PGE2 secretion in a dose‐dependent manner. These results thus suggested that aspirin inhibited COX‐2 protein expression as well as its enzymatic activity.

Fig. 5.

Western blot analysis and ELISA analysis

(a) Determination of NF‐κB p65 levels in SMMC‐7721 cells treated with free aspirin. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3), # P < 0.05, (b) Determination of COX‐2 level in SMMC‐7721 cells treated with free aspirin. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3), # P < 0.05, (c) Determination of PGE2 levels in the supernatant of SMMC‐7721 cells treated with free aspirin by ELISA. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3), # P < 0.05

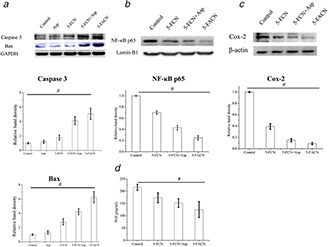

To further investigate 5‐FACN induced apoptosis, the apoptosis related protein expressions such as caspase‐3 and Bax were detected by western blot. From Fig. 6, we can see that comparing with groups treated with 5‐FCN, the expression of NF‐κB p65 and COX‐2 levels were significantly down‐regulated, and the higher expressions of caspase‐3 and Bax were also induced by the addition of aspirin in a dose‐dependent manner in SMMC‐7721 cells treated with 5‐FACN and the combination of 5‐FCN and free aspirin. It demonstrated that the addition of aspirin enhanced cell's sensitivity to 5‐Fu by promoting cell apoptosis effects. Herein, a combination of 5‐Fu and aspirin contributed to tumour cell apoptosis induction, while aspirin produced synergistic antitumour activity by inhibiting NF‐κB activation and further reducing the NF‐κB‐regulated COX‐2 expression. This suggested that the NPs could transport more 5‐Fu and aspirin into cancer cells, and their high intracellular concentrations significantly enhanced the synergistic anti‐tumour effects.

Fig. 6.

Western blot analysis and ELISA analysis

(a) Determination of caspase‐3 and Bax levels treated with aspirin, 5‐FCN, 5‐FACN and the combination of 5‐FCN and free aspirin. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3), # P < 0.05. The determination of NF‐κB p65 levels, (b) COX‐2 levels, (c) PEG2 levels, (d) Treated with 5‐FCN, 5‐FACN and the combination of 5‐FCN and free aspirin. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3), # P < 0.05

4 Discussion

Various studies have shown that as patients diagnosed with cancer took regular aspirin, tumour‐related mortality and overall mortality were significantly reduced, especially among patients bearing tumours with high COX‐2 expression; these individuals benefited most from the daily administration of aspirin [33, 34, 35]. A large number of studies confirmed that aspirin has a potential anti‐tumour effect; however, the application mechanisms underlying the application of aspirin combined with nano‐agents containing anti‐tumour drugs is not yet clear. Compared with the closest work related with aspirin in anti‐cancer treatment [36, 37], we used a novel nano‐drug delivery system to encapsulate both drugs and enhanced the cellular internalisation of drugs, thus showing higher uptake and increasing the therapeutic efficacy. In addition, we selected a non‐cytotoxic concentrations of aspirin (0.1 and 0.5 mM) to combine with 5‐Fu to evaluate its synergistic antitumour activity. In this experiment, we observed that 5‐Fu and aspirin‐loaded CNs were used in the treatment of liver cancer. This study first investigated the cytotoxic effects of aspirin on hepatoma cells, SMMC‐7721 and HepG2. It was found that free aspirin showed a certain level of cytotoxicity at concentration greater than 2 mM, which was also harmful to normal cells and even led to severe side effects. Therefore, we chose non‐cytotoxic concentration of aspirin at 0.1 and 0.5 mM to evaluate its synergistic antitumour activity. We also found that blank CNs had no effect on the growth of cells within 48 h, indicating that there was no obvious cytotoxic side effect, and that the prepared NPs were safe and non‐toxic in the dose range. The effects of 5‐Fu, 5‐FCN, 5‐FACN and the combination of 5‐FCN and free aspirin on the proliferation of hepatocarcinoma SMMC‐7721 and HepG2 cells were investigated by MTT and cell‐cycle experiments. The results showed that when compared with free 5‐Fu and 5‐FCN, 5‐FACN and the combination of 5‐FCN and free aspirin caused an obvious decrease in cell viability, indicating that aspirin synergistically enhanced the anti‐tumour effect of 5‐Fu. Furthermore, 5‐FACN induced the highest cell apoptosis and strengthened 5‐Fu‐mediated G1‐phase accumulation. We also confirmed that aspirin inhibited NF‐κB activation and further reduced NF‐κB‐regulated COX‐2 and PGE2 expression, thus promoting 5‐Fu mediated apoptosis.

5 Conclusion

Overall, we had demonstrated that aspirin was capable of regulating the NF‐κB/COX‐2 signalling pathway in HCC cells, raising the possibility of using selected NSAIDs as therapeutic agents to enhance the anti‐tumour effects of anti‐cancer drugs. Aspirin and the anticancer drug 5‐Fu were well encapsulated in CNs to obtain 5‐Fu/aspirin‐loaded CN (5‐FACN). The results showed that 5‐FACN produced a strong synergistic effect on the growth inhibition of HCC cells through the aspirin‐induced suppression of NF‐κB and inhibition of COX‐2.

6 Acknowledgment

P. Wang and Y. Shen contributed equally to this work. This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (no. 201602337). The authors thank the above funding. The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

7 References

- 1. Salgia R. Singal A.G.: ‘Hepatocellular carcinoma and other liver lesions’, Med. Clin. North Am., 2014, 98, (1), pp. 103 –118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Farazi P.A. DePinho R.A.: ‘Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment’, Nat. Rev. Cancer, 2006, 6, pp. 674 –687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang H. Chen L.: ‘Tumor microenviroment and hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis’, J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 2013, 1, (28 Suppl), pp. 43 –48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kerr S.H. Kerr D.J.: ‘Novel treatments for hepatocellular cancer’, Cancer Lett., 2009, 286, (1), pp. 114 –120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lopez P.M. Villanueva A. Llovet J.M.: ‘Systematic review: evidence‐based management of hepatocellular carcinoma‐‐an updated analysis of randomized controlled trials’, Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther., 2006, 23, (11), pp. 1535 –1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hsu Y.C. Ho H.J. Wu M.S. et al.: ‘Postoperative peg‐interferon plus ribavirin is associated with reduced recurrence of hepatitis C virus‐related hepatocellular carcinoma’, Hepatology, 2013, 58, (1), pp. 150 –157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu T.J. Chang S.S. Li C.W. et al.: ‘Severe hepatitis promotes hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence via NF‐κB pathway‐mediated epithelial‐mesenchymal transition after resection’, Clin. Cancer. Res., 2016, 22, (7), pp. 1800 –1812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuczynski E.A. Lee C.R. Man S. et al.: ‘Effects of sorafenib dose on acquired reversible resistance and toxicity in hepatocellular carcinoma’, Cancer Res., 2015, 75, (12), pp. 2510 –2519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen J. Jin R. Zhao J. et al.: ‘Potential molecular, cellular and microenvironmental mechanism of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma’, Cancer. Lett., 2015, 367, (1), pp. 1 –11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhu Y.J. Zheng B. Wang H.Y. et al.: ‘New knowledge of the mechanisms of sorafenib resistance in liver cancer’, Acta. Pharmacol. Sin., 2017, 38, (5), pp. 614 –622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gomes M. Teixeira A.L. Coelho A. et al.: ‘The role of inflammation in lung cancer’, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol., 2014, 816, pp. 1 –23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu Q. Tan Q. Zheng Y. et al.: ‘Blockade of Fas signaling in breast cancer cells suppresses tumor growth and metastasis via disruption of Fas signaling‐initiated cancer‐related inflammation’, J. Biol. Chem., 2014, 289, (16), pp. 11522 –11535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13. Elinav E. Nowarski R. Thaiss C.A. et al.: ‘Inflammation‐induced cancer: crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms’, Nat. Rev. Cancer., 2013, 13, (11), pp. 759 –771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wilson K.T. Fu S. Ramanujam K.S. et al.: ‘Increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase‐2 in barrett's esophagus and associated adenocarcinomas’, Cancer Res., 1998, 58, (14), pp. 2929 –2934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zimmermann K.C. Sarbia M. Weber A.A. et al.: ‘Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in human esophageal carcinoma’, Cancer Res., 1999, 59, (1), pp. 198 –204 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kern M.A. Schöneweiss M.M. Sahi D. et al.: ‘Cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors suppress the growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma implants in nude mice’, Carcinogenesis, 2004, 25, (7), pp. 1193 –1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Larkins T.L. Nowell M. Singh S. et al.: ‘Inhibition of cyclooxygenase‐2 decreases breast cancer cell motility, invasion and matrix metalloproteinase expression’, BMC Cancer, 2006, 6, p. 181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Banu S.K. Lee J. Speights V.O. Jr et al.: ‘Cyclooxygenase‐2 regulates survival, migration, and invasion of human endometriotic cells through multiple mechanisms’, Endocrinology, 2008, 149, (3), pp. 1180 –1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ali‐Fehmi R. Morris R.T. Bandyopadhyay S. et al.: ‘Expression of cyclooxygenase‐2 in advanced stage ovarian serous carcinoma: correlation with tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and survival’, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol., 2005, 192, (3), pp. 819 –825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rizzo M.T.: ‘Cyclooxygenase‐2 in oncogenesis’, Clin. Chim. Acta., 2011, 412, (9–10), pp. 671 –687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dong X. Li R. Xiu P. et al.: ‘Meloxicam executes its antitumor effects against hepatocellular carcinoma in COX‐2‐ dependent and ‐independent pathways’, PLOS One, 2014, 9, (3), p. e92864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jana N.R.: ‘NSAIDs and apoptosis’, Cell Mol. Life Sci., 2008, 65, (9), pp. 1295 –1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takada Y. Bhardwaj A. Potdar P. et al.: ‘Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory agents differ in their ability to suppress NF‐kappaB activation, inhibition of expression of cyclooxygenase‐2 and cyclin D1, and abrogation of tumor cell proliferation’, Oncogene, 2004, 23, (57), pp. 9247 –9258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yhee J.Y. Son S. Lee H. et al.: ‘Nanoparticle‐based combination therapy for cancer treatment’, Curr. Pharm. Des., 2015, 21, (22), pp. 3158 –3166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ge Y. Ma Y. Li L.: ‘The application of prodrug‐based nano‐drug delivery strategy in cancer combination therapy’, Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces, 2016, 146, pp. 482 –489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang T. Narayanaswamy R. Ren H. et al.: ‘Combination therapy targeting both cancer stem‐like cells and bulk tumor cells for improved efficacy of breast cancer treatment’, Cancer Biol. Ther., 2016, 17, (6), pp. 698 –707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin J. Wu L. Bai X. et al.: ‘Combination treatment including targeted therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma’, Oncotarget, 2016, 7, (43), pp. 71036 –71051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ke F. Zhang M. Qin N. et al.: ‘Synergistic antioxidant activity and anticancer effect of green tea catechin stabilized on nanoscale cyclodextrin‐based metal–organic frameworks’, J. Mater. Sci., 2019, 54, pp. 10420 –10429 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ke X. Song X. Qin N. et al.: ‘Rational synthesis of magnetic Fe3O4@MOF nanoparticles for sustained drug delivery’, J. Porous Mater., 2019, 26, pp. 813 –818 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yu X. Yang G. Shi Y. et al.: ‘Intracellular targeted co‐delivery of shMDR1 and gefitinib with chitosan nanoparticles for overcoming multidrug resistance’, Int. J. Nanomed., 2015, 10, pp. 7045 –7056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhao L. Yang G. Shi Y. et al.: ‘Co‐delivery of Gefitinib and chloroquine by chitosan nanoparticles for overcoming the drug acquired resistance’, J. Nanobiotechnology, 2015, 13, p. 57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu X.L. Yang Z.W. He L et al.: ‘RRS1 silencing suppresses colorectal cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenesis by inhibiting G2/M progression and angiogenesis’, Oncotarget, 2017, 8, (47), pp. 82968 –82980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moysich K.B. Menezes R.J. Ronsani A. et al.: ‘Regular aspirin use and lung cancer risk’, BMC Cancer, 2002, 2, p. 31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van Dyke A.L. Cote M.L. Prysak G. et al.: ‘Regular adult aspirin use decreases the risk of non‐small cell lung cancer among women’, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 2008, 17, (1), pp. 148 –157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cuzick J. Otto F. Baron J.A. et al.: ‘Aspirin and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for cancer prevention: an international consensus statement’, Lancet Oncol., 2009, 10, (5), pp. 501 –507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fu J. Xu Y. Yang Y. et al.: ‘Aspirin suppresses chemoresistance and enhances antitumor activity of 5‐Fu in 5‐Fu‐resistant colorectal cancer by abolishing 5‐Fu‐induced NF‐κB activation’, Sci. Rep., 2019, 9, (1), p. 16937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Olejniczak‐Kęder A. Szaryńska M. Wrońska A. et al.: ‘Effects of 5‐FU and anti‐EGFR antibody in combination with ASA on the spherical culture system of HCT116 and HT29 colorectal cancer cell lines’, Int. J. Oncol., 2019, 55, (1), pp. 223 –242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]