Abstract

Excessive use of antibiotics has posed two major challenges in public healthcare. One of them is associated with the development of multi‐drug resistance while the other one is linked to side effects. In the present investigation, the authors report an innovative approach to tackle the challenges of multi‐drug resistance and acute toxicity of antibiotics by using antibiotics adsorbed metal nanoparticles. Monodisperse silver nanoparticles (SNPs) have been synthesised by two‐step process. In the first step, SNPs were prepared by chemical reduction of AgNO3 with oleylamine and in the second step, oleylamine capped SNPs were phase‐transferred into an aqueous medium by ligand exchange. Antibiotics – tetracycline and kanamycin were further adsorbed on the surface of SNPs. Antibacterial activities of SNPs and antibiotic adsorbed SNPs have been investigated on gram‐positive (Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus subtilis), and gram‐negative (Proteus vulgaris, Shigella sonnei, Pseudomonas fluorescens) bacterial strains. Synergistic effect of SNPs on antibacterial activities of tetracycline and kanamycin has been observed. Biocidal activity of tetracycline is improved by 0–346% when adsorbed on SNPs; while for kanamycin, the improvement is 110–289%. This synergistic effect of SNPs on biocidal activities of antibiotics may be helpful in reducing their effective dosages.

Inspec keywords: silver, silver compounds, nanomedicine, nanoparticles, drug delivery systems, drugs, antibacterial activity, microorganisms, nanofabrication, materials preparation, reduction (chemical), adsorption, surface chemistry, surface treatment

Other keywords: public healthcare, multi‐drug resistance, side effect, acute antibiotic toxicity, antibiotic adsorbed metal nanoparticle, monodisperse silver nanoparticle, two‐step SNP synthesis, SNP preparation, AgNO3 chemical reduction, oleylamine capped SNP phase‐transfer, aqueous medium, ligand exchange, tetracycline, kanamycin, antibacterial activity, antibiotic adsorbed SNP, gram‐positive bacterial strain, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus megaterium, Bacillus subtilis, gram‐negative bacterial strain, Proteus vulgaris, Shigella sonnei, Pseudomonas fluorescens, SNP synergistic effect, effective dosage reduction, Ag, AgNO3

1 Introduction

Antibiotics are widely used to treat infectious diseases caused by pathogenic microorganisms [1]. In recent years, serious concerns have been raised by medical professionals towards the widespread development of pathogenic organisms, which are resistant to multiple antibiotics [2, 3, 4]. Another critical concern is serious side‐effects associated with antibiotic drugs [5]. Non‐target effects of antibiotics can cause a range of illnesses like nausea, diarrhoea, allergic reactions, fever to life threatening diseases like formation of kidney stones, abnormal blood clotting, liver transplantation, death from acute liver failure, etc. [6, 7]. In order to overcome these limitations of antibiotics, pharmacologists are working on alternate medicines, which are neither prone to the development of drug resistance nor suffer from serious side‐effects associated with traditional antibiotics [8, 9].

Antibacterial properties of metals are well known since ancient times [10]. They were widely used in preventive healthcare in the history of human civilisation [11]. Amongst noble metals, silver has shown a wide range of biocidal activities [12, 13]. Recent development in nanoparticle technology has further enhanced biocidal activities of noble metal nanoparticles [10]. Amongst noble metals, silver has the highest antibacterial activity [14]. Due to this reason, silver nanoparticles (SNPs) are now widely used as antibacterial agents in a range of products like wound dressing, urinary track catheters, cardiac devices, topical gels, endotracheal breathing tubes, dental implants and so on [15].

There are several reports on the size and dose dependent toxicity of SNPs in human cells [16, 17, 18, 19]. In a recent review, Hadrup and Lam [17] have explained various pathways of SNPs’ toxicity in human normal cells. Park et al. [18] and AshaRani et al. [19] have found that SNPs induced cellular toxicity in human cells by DNA damage and chromosomal aberrations. Toxicity of SNPs to human cells is contentious and hence at present, SNPs are administrated by topical means only in the form of ointments below a critical threshold concentration.

There are few reports on synergistic effect of conventional antibiotics on biocidal activities of SNPs [20, 21, 22]. Filgueiras et al. [20] have reported adsorption strategies of antibiotics levofloxacin, tetracycline and benzyl penicillin on SNPs. Ghosh et al. [21] have demonstrated synergistic antibacterial activities of cinnamaldehyde adsorbed SNPs. Hwang et al. [22] have also reported adsorption of ampicillin, chloramphenicol and kanamycin on SNPs. These reports have demonstrated that adsorption of conventional antibiotics have synergistic effect on antimicrobial activities of SNPs.

Amongst conventional antibiotics, tetracycline and kanamycin are extensively used for the treatment of various infections [6, 23, 24]. The use of antibiotics is on decline because of the widespread development of drug resistance in causative organisms [25, 26]. To overcome these drawbacks of narrow targeting antibiotics, in this paper, we propose new formulations of these antibiotic drugs whose pharmacokinetic and toxicological effects are already known. In this study, we report synthesis of uniform, monodispersed water‐dispersible SNPs and antibiotic (tetracycline/kanamycin) adsorbed SNPs and their bactericidal activities against pathogenic and non‐pathogenic strains and tried to understand the synergy between conventional and nanoantibiotics.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Silver nitrate (AgNO3) (99.8%) and diphenyl ether were procured from S D Fine‐Chem Limited. Oleylamine (70%) and pluronic F‐127 were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Absolute ethanol, n‐hexane (95%) and HPLC grade water were purchased from Merck. All chemicals were used as received without further purification. Mueller Hinton Agar (MM019) and nutrient broth (NM019) were purchased from Sisco Research Laboratories. The gram‐positive {[Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (MTCC No. 9760)], [Bacillus megaterium (B. megaterium) (MTCC No. 428)], Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis) (MTCC No. 441)}, and gram‐negative {[Proteus vulgaris (P. vulgaris) (MTCC No. 426], [Shigella sonnei (S. sonnei) (MTCC No.2957), [Pseudomonas fluorescens (P. fluorescens) (MTCC No. 1749)]} bacterial cultures were obtained from IMTECH, Chandigarh, India. Antibiotics tetracycline and kanamycin were purchased from Himedia.

2.2 Synthesis of SNPs

In this study, we report synthesis of uniform, monodisperse SNPs by slow and controlled reduction of AgNO3 with oleylamine [27]. Diphenyl ether (20 mL) was mixed with 15 mM oleylamine in a 100 mL round bottom flask, equipped with a magnetic stirrer, condenser and a thermometer. The mixture was heated to 200°C at 3°C/min. 3 mM AgNO3 was added into the preheated diphenyl ether–oleylamine under continuous magnetic stirring. Colour of the mixture immediately turned blue when AgNO3 was added into diphenyl ether–oleylamine. Strong surface plasmon resonance (SPR) was observed, indicating the nucleation of SNPs. It was refluxed for 30 min followed by ripening at 150°C for 4 h. The colloidal solution was then cooled down to room temperature, precipitated by ethanol and purified by precipitation–redispersion [27].

Oleylamine coating on SNPs surface renders them hydrophobic. For biomedical applications, SNPs must be water dispersible. To obtain water dispersible SNPs, in the second step, as‐synthesised hydrophobic SNPs were phase transferred from n‐hexane to water by the facile phase transfer protocols [28]. In brief, equal volume of aqueous pluronic F‐127 was mixed with n‐hexane solution of SNPs. Concentration of pluronic F‐127 was kept such that the Ag:pluronic F‐127 weight ratio was 1:0.5. Initially the organic phase of SNPs was well separated from the aqueous phase of pluronic. Upon magnetic stirring, both immiscible phases mixed with each other. The beaker was covered with a perforated aluminium foil to control the evaporation of organic phase. It was stirred until the organic phase evaporated completely. To confirm the phase transfer of SNPs, n‐hexane was poured into the aqueous solution of SNPs. On successful phase transfer, both aqueous and n‐hexane phases would remain immiscible.

Antibiotic adsorbed SNPs were prepared by vortex mixing of 10 mL aqueous colloidal dispersion of SNPs with desired quantity of tetracycline or kanamycin for 12 h. The final concentration of SNPs in antibiotic adsorbed SNPs was adjusted to 250 ppm. The colloid was centrifuged at 12,000 RPM and supernal was removed. The final volume of nanoparticle suspension was readjusted to 10 mL by addition of ultrapure water. These stock solutions of antibiotic adsorbed SNPs were further used for the antibacterial activity test.

2.3 Characterisation of SNPs

Growth of SNPs was monitored by UV–visible spectroscopy. UV–visible spectra of as‐synthesised (in n‐hexane) and phase transferred (in water) SNPs were recorded on Hitachi U‐3900H double beam UV–visible spectrophotometer. Hydrodynamic size and size distribution of SNPs was obtained by dynamic light scattering. The measurements were carried out on Brookhaven 90Plus Particle Size Analyser at 25°C. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed on Philips CM200 TEM at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Sample for TEM was prepared by placing a drop of the colloidal dispersion of SNPs in n‐hexane onto an amorphous carbon‐coated copper grid. n‐Hexane was allowed to evaporate slowly at 25°C. The size‐distribution histogram was prepared by measuring the diameter of 100 particles from TEM micrograph. To understand the surface functionalisation of antibiotics on SNPs, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was used. FTIR spectra of antibiotics and antibiotics adsorbed SNPs were recorded on Bruker Vertex 80 FTIR spectrophotometer in the mid infrared region (4000–400 cm−1) by using diamond attenuated total reflection (ATR) accessory. Concentration of silver in aqueous dispersion was measured by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP‐AES). The measurements were performed on Spectro's ARCOS ICP‐AES.

2.4 Antibiotic content

Antibiotic content and antibiotic loading of antibiotics in antibiotic adsorbed SNPs were determined by UV–visible spectroscopy. Optical density of antibiotics that remained unincorporated (supernal) with SNPs was measured at 276 nm for tetracycline and at 256 nm for kanamycin and its concentration was determined by Beer–Lambert law, A = εcl; where A is the optical density at sample concentration c, l is the path length of sample cell (10 mm) and ε is the molar absorptivity (ε for tetracycline is 14.58 × 106 M−1 cm−1 and for kanamycin is 143.40 M−1 cm−1) of the drug. Antibiotic content and antibiotic loading efficiency were determined by using the following expressions [29]

where W 1 is the total weight of antibiotic and W 2 is the weight of free antibiotic, which did not adsorb on nanoparticles.

2.5 Antibacterial activity of SNPs

Antimicrobial activities of SNPs were evaluated in terms of MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) and ZIH (zone of inhibition) measurements. MIC was measured by micro‐dilution method, while ZIH was obtained from Kirby–Bauer (disk diffusion) assay. Both micro‐dilution and disk diffusion tests were performed on clinically important pathogenic (S. aureus, B. megaterium, P. vulgaris and S. sonnei) and non‐pathogenic (B. subtilis and P. fluorescens) strains.

In the micro‐dilution test, six sets of 10 mL nutrient broth medium containing SNPs with effective silver concentration of 0–200 μg/mL were prepared. Each set was inoculated aseptically with 108 CFU/mL of the respective bacterial suspension. The inoculated sets were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. MIC was measured by visual inspection of growth or no growth of bacterial strain in the test tubes containing different concentrations of SNPs. The lowest concentration of SNPs that inhibited bacterial growth was taken as the MIC for that particular bacterium. Control experiments were also run parallel to investigate the antibacterial activities of nutrient broth medium.

ZIH was measured for each bacterial strain by the Kirby–Bauer method. ZIH is the area on the agar plate where the bacterial growth was prevented by antibacterial agent. Equal volume of Mueller–Hinton agar medium was poured into a disposable petri dish. The medium was allowed to solidify. The bacterial strain was inoculated onto the entire surface of a Mueller–Hinton agar plate with the help of sterile cotton‐tipped swab to form an even lawn. The sample disk containing 30 μg of antibacterial agent (SNPs/tetracycline/kanamycin/tetracycline adsorbed SNPs/kanamycin adsorbed SNPs) was put on every plate. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate and results were statically averaged. Each set was incubated at 37°C for 24 h and ZIH was measured after the incubation period.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Investigation of SNPs

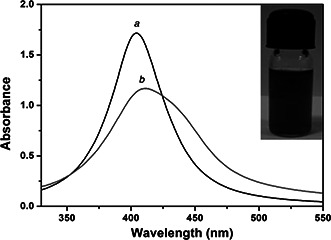

UV–visible spectra of SNPs recorded before and after the phase transfer are shown in Fig. 1. A single plasmon band was observed both before and after the phase transfer. Observation of single SPR band in the UV–visible spectra of phase transferred SNPs indicates that the particle morphology is not affected by the phase transfer. The SPR band after the phase transfer shows a red shift. This might be due to the difference in surface adsorbed species on SNPs and medium of dispersion before and after the phase transfer [30].

Fig. 1.

UV–visible spectra of SNPs (a) before and (b) after phase transfer. Single SPR peak centred at 404 nm indicating the spherical geometry of nanoparticles. The SPR band is red shifted to 413 nm after phase transfer. Inset of the figure depicts photographic view of aqueous colloidal dispersion of SNPs after the phase transfer

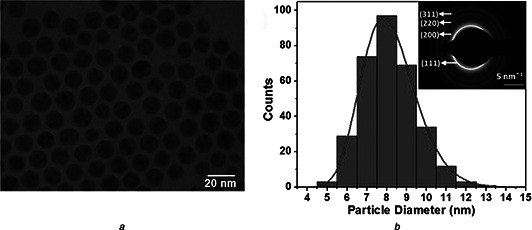

Fig. 2 a shows the TEM micrograph of as‐synthesised SNPs. Nanocrystals of silver self‐assembled into the regular hexagonal closed pack lattice. Each particle has spherical morphology. No aggregation was observed. Size distribution histogram (Fig. 2 b) was prepared by measuring the diameter of at least 100 particles. The histogram was fitted with lognormal particle size distribution function [31]. The average physical size and polydispersity index obtained from the fit are 8.07 ± 0.2 nm and 0.17 ± 0.03, respectively. Low value of polydispersity index confirms that the synthesised SNPs are monodisperse in size. Selected area electron diffraction pattern of SNPs is also shown as an inset in Fig. 2 b. Four well resolved diffraction rings corresponding to (111), (200), (220) and (311) lattice planes of FCC crystal were observed.

Fig. 2.

TEM of SNPs

a TEM micrograph of as‐synthesised SNPs

b Size distribution histogram fitted with lognormal particle size distribution function

Inset shows the specific area electron diffraction pattern corresponding to FCC structure of silver

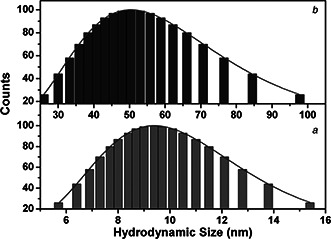

The hydrodynamic particle size distribution of SNPs recorded before and after the phase transfer is shown in Fig. 3. Each histogram was fitted with lognormal particle size distribution function [31]. The mean hydrodynamic size was 10.2 ± 0.2 nm (before the phase transfer) and 59 ± 0.14 nm (after the phase transfer), respectively. An increase in the hydrodynamic size of SNPs after their phase transfer is because of the difference in the hydrodynamic size of surface adsorbed species [32]. The mean hydrodynamic size (10.2 nm) of as‐synthesised SNPs (in n‐hexane) is greater than its physical size (8.07 nm) obtained from transmission electron microscopy. This is obvious as hydrodynamic size accounts for both the core and the coating. The chain length of a monomer of oleylamine is 1.9 nm, which accounts for the difference between the physical size and hydrodynamic size of SNPs (before phase transfer) obtained from TEM and dynamic light scattering, respectively. To understand the effect of growth media on the aggregation characteristics of SNPs, their hydrodynamic size and polydispersity was measured for 20 min. It has been found that the hydrodynamic size of SNPs in the growth media increases significantly with reference to their hydrodynamic size in water. The hydrodynamic size after 20 min increases to 91.5 nm (in growth media) from 59 nm (in water) with increased polydispersity from 0.13 of 0.34. These changes in the size and size distribution of SNPs are because of the modification of the surface properties of SNPs in the growth medium, which leads to their aggregation.

Fig. 3.

Hydrodynamic size distribution histograms of SNPs (a) before and (b) after phase transfer. Each histogram is fitted with lognormal particle size distribution function

3.2 Antibiotics adsorption on SNPs

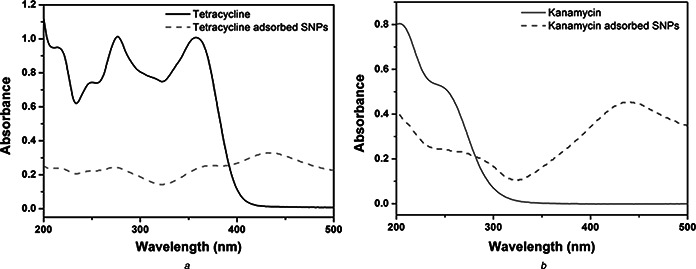

Interaction of antibiotics with SNPs was studied by UV–visible and FTIR spectroscopy. UV‐visible absorption spectra of tetracycline, tetracycline adsorbed SNPs and kanamycin, kanamycin adsorbed SNPs are shown in Fig. 4. Tetracycline has three characteristics absorption bands in its UV–visible spectrum at 250, 275 and 357 nm. They correspond to π→π* transitions of C=C. Kanamycin has no characteristic absorption band in the UV–visible region, but its complex with copper shows characteristics absorption at 256 nm. To monitor kanamycin, we have prepared solution of kanamycin in copper containing aqueous medium. UV–visible spectrum of this is shown in Fig. 4. In case of tetracycline adsorbed SNPs, multiplets of tetracycline are shifted to 252, 272 and 374 nm. The SPR due to SNPs has been red shifted from 428 to 435 nm. In case of kanamycin adsorbed SNPs, the characteristic absorption of kanamycin at 256 nm has been shifted to 252 nm while the SPR band of SNPs is shifted to 430 nm. Slight blue shifts in the spectral signatures of tetracycline, kanamycin and SNPs indicate the physisorption of antibiotics on SNPs.

Fig. 4.

UV–visible spectra of

a Tetracycline (line) and tetracycline adsorbed SNPs (small dashed line);

b Kanamycin (line) and kanamycin adsorbed SNPs (small dashed line).

Slight blue shift in the characteristics absorption peaks of tetracycline adsorbed SNPs and kanamycin adsorbed SNPs shows that antibiotics are physisorbed on the surface of SNPs

Physisorption of antibiotics on SNPs is further confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy. It is a powerful technique used to understand surface functionalisation of nanoparticles. In Fig. 5, FTIR spectra of tetracycline, tetracycline adsorbed SNPs, kanamycin and kanamycin adsorbed SNPs are shown. No major peak shift in the fingerprint region of the FTIR spectra of tetracycline or kanamycin has been observed when they adsorbed on the surface of SNPs, which further strengthen our claim that the antibiotics are physisorbed on nanoparticles’ surface.

Fig. 5.

FTIR spectra of tetracycline, tetracycline adsorbed SNPs, kanamycin and kanamycin adsorbed SNPs

3.3 Antibiotic content and antibacterial activity

Antibiotic content and antibiotic loading were determined from UV–visible spectroscopy. The loading efficiency of tetracycline was 15.3% and drug content was 40.56%. For kanamycin, the loading efficiency was 6.44% and the drug content was 90.40%. Antibacterial activity of SNPs was evaluated against four pathogenic (S. aureus, B. megaterium, P. vulgaris and S. sonnei) and two non‐pathogenic (B. subtilis and P. fluorescens) strains by micro‐dilution and Kirby–Bauer tests. From micro‐dilution method, the MIC values of pluronic F‐127 stabilised SNPs were determined. To further understand the effectiveness of antibacterial agents on pathogenic microorganisms, the ZIH was measured by Kirby–Bauer test. The MIC values of SNPs for the bacterial strains under investigation are reported in Table 1. The MIC value of SNPs is 75 µg/mL for B. megaterium followed by 100 µg/mL for P. vulgaris and S. sonnei and 150 µg/mL for S. aureus. For non‐pathogenic strains, these MIC values are 25 µg/mL each for B. subtilis and P. fluorescens.

Table 1.

Synergistic effect of SNPs on antibacterial activities of commercial antibiotics

| Strains | MIC, µg/mL | ZIH, mm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Tetracycline | Kanamycin | SNPs | Tetracycline adsorbed SNPs | Kanamycin adsorbed SNPs | ||

| S. aureus | 150 | 0 | 29 | 22 | 11 | 34 | 26 |

| B. megaterium | 75 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 7 | 7 | 31 |

| P. vulgaris | 100 | 0 | 26 | 24 | 7 | 27 | 27 |

| S. sonnei | 100 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 8 | 8 | 24 |

| B. subtilis | 25 | 0 | 34 | 29 | 6 | 50 | 20 |

| P. fluorescens | 25 | 0 | 22 | 11 | 7 | 40 | 30 |

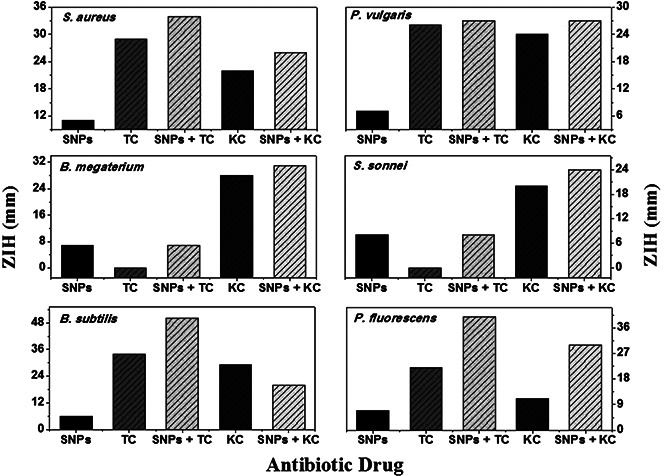

Results of antimicrobial tests of SNPs by Kirby–Bauer method are shown in Fig. 6 and summarised in Table 1. To understand the synergistic effect of SNPs on antibacterial activities of commercial antibiotics, the Kirby–Bauer test was also performed on tetracycline adsorbed SNPs and kanamycin adsorbed SNPs. An increase in the inhibition zone was found to be in the range of 0–346% for microorganisms under investigation when tetracycline was adsorbed on SNPs. The ZIH increases by 110–289% when kanamycin adsorbed on SNPs. The % increase in ZIH values was determined by applying the correction for effective antibiotic content (15.3% for tetracycline and 6.44% for kanamycin) in antibiotic adsorbed SNPs. The synergistic effect of SNPs is clearly evidenced by the percentage increase in ZIH for antibiotic adsorbed SNPs with respect to the inhibition zone found for antibiotic.

Fig. 6.

ZIH of SNPs, antibiotics and antibiotics adsorbed nanoparticles against S. aureus, B. megaterium, B. subtilis, P. vulgaris, S. sonnei and P. fluorescens

Results of micro‐dilution and Kirby–Bauer tests show strong biocidal activities of SNPs and antibiotic adsorbed SNPs. The exact mechanism responsible for this bactericidal action of SNPs and its synergistic effect on commercial antibiotics is not well understood. Various possible modes of biocidal action of metal nanoparticles were proposed in the literature [33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38]. Poisoning of bacterial cell by antibiotic adsorbed SNPs is a multi‐step process. In the first step, antibacterial agent internalises into the bacterial cell. Nanoparticles diffuse into the bacterial cell by ion‐transport proteins [34]. Some nanoparticles also enter into the bacterial cell by endocytosis [35]. The bacterial cell wall is composed of thick peptidoglycan layer linked to teichoic acid that gives negative charge to the cell wall. The negative charge facilitates the interaction between the cell wall and positively charged metal. Interaction between metal ion and bacterial cell wall causes the loss of membrane integrity. The damaged membrane allows the entry of substances from the environment (traditional antibiotics in our case), which causes osmotic imbalance. The damaged cell membrane also allows the leakage of minerals and genetic materials. The leakage of cytoplasmic content and consequent rupture of the cell leads to its death.

In the second step, internalised nanoparticles and antibiotics induce toxicity by reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediated cellular damage or because of the metal catalysed oxidation reaction that could underline specific proteins, membrane or DNA damage. Increasing ROS level in the cellular environment leads to the rapid degradation of cellular contents that eventually leads to the cell death [35]. Another possibility is the formation of protein disulphides and depletion of antioxidant reserves [36]. This is because of the formation of covalent bonds between metal ions and S. This depletion in antioxidant reserves can leave protein targets vulnerable to attack by metal ions or ROS. It also prevents repair of oxidised protein and thus enhances the possibility of oxidative stress induced cellular damaged in bacteria [36]. Metal nanoparticles can induce toxicity to bacterial cells by protein dysfunction. Amino acid residue in proteins is susceptible to metal‐catalysed oxidation [37]. Oxidation of amino acid side chains in proteins can cause loss of catalytic activity and trigger protein degradation [37]. This degradation might also be responsible for the nanoparticle toxicity.

The observed toxicity is also linked to starvation‐induced growth arrest. SNPs inhibit the uptake of sulphate and deplete intracellular S metabolite pool [38]. Due to supplementation with sulphate and other S sources mitigates toxicity in a concentration dependent manner, it has been suggested that SNPs starve cells of S by interfering with its sulphate uptake and thus induce cell apoptosis. The presence of metal nanoparticles and conventional antibiotics in bacterial medium execute these modes simultaneously. The growth inhibition and cellular death of bacterial cells are due to combination of these mechanisms.

4 Conclusions

Antibiotic adsorption on SNPs enhances the biocidal activities of conventional antibiotics. The antimicrobial efficiency of tetracycline increases by 0–346% when adsorbed on SNPs, while for kanamycin; the increase is in the range of 110–289%. The observed synergies between conventional antibiotics and SNPs in their biocidal activities against pathogenic and non‐pathogenic microorganisms are because of execution of various modes of biocidal action of metal nanoparticles and conventional antibiotics, simultaneously.

5 Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to University Grants Commission, New Delhi (scheme no. F. no. 42‐850/2013 (SR)) for financial support. They also acknowledge SAIF, IITB for extending transmission electron microscopy and ICP‐AES facilities.

6 References

- 1. Reese R.E. Betts R.F. Gumustop B.: ‘Handbook of antibiotics’ (The Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Handbook Series, 1993, 3rd edn.) [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moran L.F. Aronsson B. Manz C. et al.: ‘Critical shortage of new antibiotics in development against multidrug‐resistant bacteria‐Time to react is now’, Drug Resist. Updat., 2011, 14, pp. 118 –124 (doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2011.02.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Batabyal P. Mookerjee S. Sur D. et al.: ‘Diarrheogenic Escherechia coli in potable water sources of West Bengal, India’, Acta Trop., 2013, 127, pp. 153 –157 (doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.04.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hui C. Lin M.C. Jao M.S. et al.: ‘Previous antibiotic exposure and evolution of antibiotic resistance in mechanically ventilated patients with nosocomial infections’, J. Crit. Care, 2013, 28, pp. 728 –734 (doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.04.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Granowitz E.V. Brown R.B.: ‘Antibiotic adverse reactions and drug interactions’, Crit. Care Clin., 2008, 24, pp. 421 –442 (doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2007.12.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tan H. Ma C. Song Y. et al.: ‘Determination of tetracycline in milk by using nucleotide/lanthanide coordination polymer‐based ternary complex’, Biosens. Bioelectron., 2013, 50, pp. 447 –452 (doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.07.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grill M.F. Maganti R.K.: ‘Neurotoxic effects associated with antibiotic use: management considerations’, Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol., 2011, 72, pp. 381 –393 (doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03991.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Varkey A.J.: ‘Antibacterial properties of some metals and alloys in combating coliforms in contaminated water’, Sci. Res. Essays, 2010, 5, pp. 3834 –3839 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rizzo L. Sannino D. Vaiano V. et al.: ‘Effect of solar simulated N‐doped TiO2 photocatalysis on the inactivation and antibiotic resistance of an E. coli strain in biologically treated urban waste water’, Appl. Catal. B, Environ., 2014, 144, pp. 369 –378 (doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.07.033) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yasuyuki M. Kunihiro K. Kurissery S. et al.: ‘Antibacterial properties of nine pure metals: a laboratory study using Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli ’, Biofouling, 2010, 26, pp. 851 –858 (doi: 10.1080/08927014.2010.527000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Loomba L. Scarabelli T.: ‘Metallic nanoparticles and their medicinal potential. Part II: aluminosilicates, nanobiomagnets, quantum dots and cochleates’, Ther. Deliv., 2013, 4, pp. 1179 –1196 (doi: 10.4155/tde.13.74) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shanmugasundaram T. Radhakrishnan M. Gopikrishnan V. et al.: ‘A study of the bactericidal, anti‐biofouling, cytotoxic and antioxidant properties of actinobacterially synthesised silver nanoparticles’, Colloids Surf. B, Biointerfaces, 2013, 111, pp. 680 –687 (doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.06.045) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao X. Toyooka T. Ibuki Y.: ‘Synergistic bactericidal effect by combined exposure to Ag nanoparticles and UVA’, Sci. Total Environ., 2013, 458–460, pp. 54 –62 (doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.03.098) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morones J.R. Elechiguerra J.L. Camacho A. et al.: ‘The bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles’, Nanotechnology, 2005, 16, pp. 2346 –2353 (doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/16/10/059) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kvitek L. Panacek A. Prucek R. et al.: ‘Antibacterial activity and toxicity of silver–nanosilver versus ionic silver’, J. Phys., Conf. Series, 2011, 304, pp. 012029 –012036 (doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/304/1/012029) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martínez‐Gutierrez F. Thi E.P. Silverman J.M. et al.: ‘Antibacterial activity, inflammatory response, coagulation and cytotoxicity effects of silver nanoparticles’, Nanomed., Nanotechnol. Biol. Med., 2012, 8, pp. 328 –336 (doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.06.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hadrup N. Lam H.R.: ‘Oral toxicity of silver ions, silver nanoparticles and colloidal silver – a review’, Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 2014, 68, pp. 1 –7 (doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2013.11.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park M.V.D.Z. Neigh A.M. Vermeulen J.P. et al.: ‘The effect of particle size on the cytotoxicity, inflammation, developmental toxicity and genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles’, Biomaterials, 2011, 32, pp. 9810 –9817 (doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.085) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. AshaRani P.V. Mun G.L.K. Hande M.P. et al.: ‘Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human cells’, ACS Nano, 2009, 3, pp. 279 –290 (doi: 10.1021/nn800596w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Filgueiras A.L. Paschoal D. Santos H.F.D. et al.: ‘Adsorption study of antibiotics on silver nanoparticle surfaces by surface‐enhanced Raman scattering spectroscopy’, Spectrochim. Acta A, Mol. Biomol. Spectros., 2015, 136, pp. 979 –985 (doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.09.120) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ghosh I.N. Patil S.D. Sharma T.K. et al.: ‘Synergistic action of cinnamaldehyde with silver nanoparticles against spore‐forming bacteria: a case for judicious use of silver nanoparticles for antibacterial applications’, Int. J. Nanomed., 2013, 8, pp. 4721 –4731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hwang I. Hwang J.H. Choi H. et al.: ‘Synergistic effects between silver nanoparticles and antibiotics and the mechanisms involved’, J. Med. Microbiol., 2012, 61, pp. 1719 –1726 (doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.047100-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sina H. Ahoyo T.A. Moussaoui W. et al.: ‘Variability of antibiotic susceptibility and toxin production of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from skin, soft tissue, and bone related infections’, BMC Microbiol., 2013, 13, pp. 188 –196 (doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-188) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yu S. Wei Q. Du B. et al.: ‘Label‐free immunosensor for the detection of kanamycin using Ag@Fe3 O4 nanoparticles and thionine mixed grapheme sheet’, Biosens. Bioelectron., 2013, 48, pp. 224 –229 (doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.04.025) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jugheli L. Bzekalava N. Rijk P.D. et al.: ‘High level of cross‐resistance between kanamycin, amikacin, and capreomycin among mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Georgia and a close relation with mutations in the rrs gene’, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., 2009, 53, pp. 5064 –5068 (doi: 10.1128/AAC.00851-09) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sullivan B.A. Gentry T. Karthikeyan R.: ‘Characterization of tetracycline‐resistant bacteria in an urbanizing subtropical water shed’, J. Appl. Microbiol., 2013, 115, pp. 774 –785 (doi: 10.1111/jam.12283) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guzman M. Dille J. Godet S.: ‘Synthesis and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles against gram‐positive and gram‐negative bacteria’, Nanomed., Nanotechnol. Biol. Med., 2012, 8, pp. 37 –45 (doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.05.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chandni Andhariya N. Pandey O.P. et al.: ‘A growth kinetic study of ultrafine monodispersed silver nanoparticles’, RSC Adv., 2013, 3, pp. 1127 –1136 (doi: 10.1039/c2ra21912c) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang J. Misra R.: ‘Magnetic drug‐targeting carrier encapsulated with thermosensitive smart polymer: core‐shell nanoparticle carrier and drug release response’, Acta Biomater., 2007, 3, pp. 838 –850 (doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.05.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chudasama B. Vala A.K. Andhariya N. et al.: ‘Highly bacterial resistant silver nanoparticles: synthesis and antibacterial activities’, J. Nanoparticle Res., 2010, 12, pp. 1677 –1685 (doi: 10.1007/s11051-009-9845-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Parekh K. Upadhyay R.V. Mehta R.V.: ‘Magnetocaloric effect in temperature sensitive magnetic fluids’, Bull. Mater. Sci., 2000, 23, pp. 91 –95 (doi: 10.1007/BF02706548) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khurana C. Vala A.K. Andhariya N. et al.: ‘Antibacterial activity of silver: The role of hydrodynamic particle size at nanoscale’, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A, 2014, 102A, pp. 3361 –3368 (doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lemire J.A. Harrison J.J. Turner R.J.: ‘Antimicrobial activity of metals: mechanisms, molecular targets and applications’, Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 2013, 11, pp. 371 –384 (doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3028) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lok C.N. Ho C.M. Chen R. et al.: ‘Proteomic analysis of the mode of antibacterial action of silver nanoparticles’, J. Proteome Res., 2006, 5, pp. 916 –924 (doi: 10.1021/pr0504079) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Valko M. Morris H. Cronin M.T.D.: ‘Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress’, Curr. Med. Chem., 2005, 12, pp. 1161 –1208 (doi: 10.2174/0929867053764635) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Helbig K. Grosse C. Nies D.H.: ‘Cadmium toxicity in glutathione mutants of Escherichia coli ‘, J. Bacteriol., 2008, 190, pp. 5439 –5454 (doi: 10.1128/JB.00272-08) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stadtman E.R.: ‘Oxidation of free amino acids and amino acid residues in proteins by radiolysis and by metal‐catalysed reactions’, Ann. Rev. Biochem., 1993, 62, pp. 797 –821 (doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.004053) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pereira Y. Lagniel G. Godat E. et al.: ‘Chromate causes sulfur starvation in yeast’, Toxicol. Sci., 2008, 106, pp. 400 –412 (doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn193) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]