Abstract

The focus of this study is on a rapid and cost‐effective approach for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using Artemisia quttensis Podlech aerial parts extract and assessment of their antioxidant, antibacterial and anticancer activities. The prepared AgNPs were determined by ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy, X‐ray diffraction, Fourier transform infra‐red spectroscopy, transmission electron microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, energy‐dispersive spectroscopy, and dynamic light scattering and zeta‐potential analysis. The AgNPs and A. quttensis extract were evaluated for their antiradical scavenging activity by 2, 2‐diphenyl, 1‐picryl hydrazyl assay and anticancer activity against colon cancer (human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line 29) compared with normal human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells. Also, the prepared AgNPs were studied for its antibacterial activity. The AgNPs revealed a higher antioxidant activity compared with A. quttensis extract alone. The phyto‐synthesised AgNPs and A. quttensis extract showed a dose–response cytotoxicity effect against HT29 and HEK293 cells. As evidenced by Annexin V/propidium iodide staining, the number of apoptotic HT29 cells was significantly enhanced, following treatment with AgNPs as compared with untreated cells. Besides, the antibacterial property of the AgNPs indicated a significant effect against the selected pathogenic bacteria. These present obtained results show the potential applications of phyto‐synthesised AgNPs using A. quttensis aerial parts extract.

Inspec keywords: nanoparticles, silver, nanomedicine, cancer, transmission electron microscopy, ultraviolet spectroscopy, visible spectroscopy, X‐ray diffraction, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, electrokinetic effects, kidney, cellular biophysics, antibacterial activity, toxicology, patient treatment

Other keywords: anticancer properties; antibacterial properties; antioxidant properties; phytosynthesised Artemisia quttensis Podlech extract mediated AgNP; ultraviolet‐visible spectroscopy; X‐ray diffraction; Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy; transmission electron microscopy; scanning electron microscopy; energy‐dispersive spectroscopy; dynamic light scattering; zeta‐potential analysis; antiradical scavenging activity; 2,2‐diphenyl; 1‐picryl hydrazyl assay; anticancer activity; HT29 colon cancer; human embryonic kidney cells; HEK293 cells; A. quttensis extract; dose‐response cytotoxicity effect; Annexin V staining; apoptotic HT29 cells; pathogenic bacteria; propidium iodide staining; Ag

1 Introduction

Metallic nanoparticles (NPs) such as those of silver (Ag), gold, copper, zinc, platinum etc. has received promising attention in different applications in biotechnology, nanobiotechnology, and medical purposes and the synthesis of novel NPs for various applications is an area of continued interest. Among the various metallic NPs, AgNPs are applied in several fields especially in medicine with the potential for utilisation as biosensors, photonics, pharmaceuticals, anticancer agents, anti‐microbial, and therapeutic compounds [1, 2, 3]. AgNPs exhibit strong toxicity to a wide variety of microorganisms by a destructive effect on DNA, disturb its vital functions such as respiration, and produce oxidative stress. Several established strategies are used for fabricating of AgNPs [4] such as chemical reduction [5], electro‐irradiation [6], photochemical reduction [7], ultraviolet (UV) irradiation [8], laser‐mediated synthesis [9], and microwave‐assisted synthesis [10]. Biological method is the most preferred approach as compared with other strategies for the preparation of NPs, because it is found to be eco‐friendly, less bio hazard, and it is one‐step method for large‐scale production of NPs synthesis [11]. In this way, phyto‐synthesis of AgNPs is novel and provides a cost‐effective alternative to physical and chemical strategies [12]. Thus, several plant‐mediated approach and their extracts have exhibited considerable attention to phyto‐synthesis of AgNPs, e.g. Achillea biebersteinii [13], Eucalyptus leucoxylon [14], Chrysanthemum indicum L [15], Acacia leucophloea [16] etc. Among the various plant extracts have been utilised for the phyto‐synthesis of AgNPs, and there was no study available on the phyto‐synthesis of AgNPs using the Artemisia quttensis Podlech ethanol and analysis of their biological effects. This plant is a well‐known traditional Iranian medicinal plant growing in southeast of Iran. The genus Artemisia belongs to Asteraceae family, and commonly found in North America, Asia, and Europe. Several species of Artemisia has long been utilised in the treatment of diuretic, anti‐allergy, anthelmintic, invigorating blood, relieving cough, stopping pain, and anti‐toxic properties [17, 18]. Nowadays, a few investigations have been reported on different plant extracts of Artemisia species as phyto‐reductants for the synthesis of AgNPs. As described by Basavegowda et al. [19], a green synthesis of Ag and gold NPs prepared by using A rtemisia annua leaves extract and their antibacterial and tyrosinase inhibitory activities have been reported. Also, Khatoon et al. [20] have reported the fluorescence and antibacterial activity of synthesised AgNPs mediated A. annua leaf extract as a stabilising and reducing agent.

The main goal of this paper is to develop a simple and reliable phyto‐synthesis of AgNPs using A. quttensis Podlech aerial parts ethanolic extract and to evaluate their biomedical properties. The phyto‐synthesised AgNPs mediated A. quttensis were determined by different physical techniques. Moreover, antioxidant assay and anti‐proliferative properties of AgNPs were measured in cancer human colon cancer (HT29) and normal human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cell lines. The ability of AgNPs to induce apoptotic cell death was evaluated by Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining. In addition, its efficacy to inhibit different pathogenic bacteria was also evaluated.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Synthesis and purification of AgNPs using A. quttensis

A. quttensis Podlech was collected from Taftan, Sistan, and Baluchestan province, Iran. The plant was recognised by Mr. Dolatyari at the Herbarium of Iranian Biological Resources Center, Tehran, Iran (Voucher specimens no. IBRCP1006608). The aqueous extract of A. quttensis was prepared by mixing 20 g of dry aerial parts plant sample with 200 ml of 50% ethanol at 60°C for 10 min. The solution was filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper and then the extract was kept in a refrigerator at 4°C for future experiments. Aqueous solution of Ag nitrate (AgNO3) (Merck, Germany) at a concentration of 0.01 mM was prepared and utilised for the synthesis of AgNPs. About 12 mm of ethanolic extract was added into 180 ml of aqueous solution of AgNO3 for reduction into Ag+ ions and was followed by the colour change of the solution to dark brown.

2.2 Characterisation of AgNPs

The synthesised AgNPs was monitored by using UV–visible (vis) spectrophotometer (UV 1601, Shimadzu), at the wavelength range of 250–700 nm. Powder X‐ray diffraction (XRD) measurements of the AgNPs solution drop‐coated on glass were done on Rigaku Miniflex X‐ray diffractometer with Cu kα radians at 2θ angle. XRD is a rapid analytical technique primarily used for phase identification of a crystallographic material. The size determination and morphology of AgNPs were analysed by employing field emission‐scanning electron microscope (FE‐SEM) instrument (Society Of Independent Gasoline Marketers Of America; Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) on Japan Electron Optics Laboratory, model 1200EX at desired magnification. In addition, the elemental composition of AgNPs was obtained via energy‐dispersed spectroscopy (EDS) analysis system. The average particle size distribution and net surface charge of NPs were confirmed by Malvern Zeta sizer (Nano ZS90, UK) instrument, which is an indicator of dispersion and stability of the fabricated NPs. The AgNPs and plant extract were recorded to check the presence of functional biomolecules by using Fourier transform infra‐red (FT‐IR) spectrometer (spectrum RX 1 instrument) within the range of 400–4000 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.3 2, 2‐Diphenyl, 1‐picryl hydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay

The antioxidant effects of the A. quttensis extract and prepared AgNPs were quantitatively measured using the DPPH assay. The reaction mixture contained 3 ml methanolic solution of DPPH (final concentration was 0.1 mM), different concentrations (50–450 μg/ml) of A. quttensis extract, AgNPs, and vitamin C (positive control). After 30 min of incubation at dark room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. The free radical scavenging activity (SA) of A. quttensis ethanol extract and AgNPs was measured by using the following equation:

The corresponding inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were measured by the linear regression analysis of dose–response curve plotted between concentration and percentage of inhibition. The experiments were carried out in triplicates.

2.4 Antibacterial assay of synthesised AgNPs

The AgNPs that were synthesised using A. quttensis extract were tested for antibacterial property against three types of pathogenic bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus (American Type Culture Collection 6538), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 15442), and E scherichia coli (ATCC 6633). The antibacterial efficacy was examined by the standard Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion procedure. Briefly, the bacterial suspension (108 colony‐forming units) was swabbed on the Mueller‐Hinton Agar (Merck, Germany) plates utilising sterile cotton swabs. The sterile disc (Hi‐Media Laboratories Pvt. Ltd.) was saturated with the following different concentrations (10, 20, 30, and 40 μg/ml). After 24 h of incubation, the plates calculated for zone of bacterial inhibition in the diameter of each disc was calculated in millimetres and was recorded as mean±standard deviation (SD) of the duplicate. Ampicillin was used as a positive control.

2.5 Anticancer activity

2.5.1 Cell line and culture medium expression

The HT29 and HEK293 cell lines were obtained from the Pasteur Institute cell bank in Tehran, Iran. The cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium with 10% (foetal bovine serum), 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 100 International Unit/ml of penicillin (Gibco, Scotland) at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide (CO2).

2.5.2 In vitro cell cytotoxicity

Cell cytotoxicity effect of prepared AgNPs and A. quttensis extract in cancer HT29 and normal HEK293 cell lines were determined by Microculture Tetrazolium [3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay. Approximately, 1 × 104 (cells/well) cells were cultured in 96‐well culture plates followed by overnight incubation. The cells were then treated with series of 3.125–100 µg/ml concentrations of AgNPs and extract for 24 h. The cells were stained with 20 μl of MTT (SIGMA, USA) dye, followed by incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 4 h. The insoluble purple formazan formed within the living cells was solubilised by the addition of dimethyl sulphoxide [21, 22] and read at 570 nm using a multi‐well enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay plate reader. The optical density value was calculated as the percentage of cell viability by using the following equation:

2.5.3 In vitro apoptosis/necrosis assay

Apoptosis/necrosis cells were stained using fluorescein‐conjugated‐Annexin V/PI assay (apoptosis detection kit, Roch, Germany) and examined by flow cytometry, according to the manufacturer's instructions. At >90% confluence, the HT29 cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were incubated with prepared AgNPs for 24 h, with untreated HT29 cells as a positive control. The numbers of apoptosis and necrosis tumour cells were eventually determined by flow cytometry.

2.6 Data analysis

All measurements were performed by using one‐way analysis of variance with Statistical Package For Social Sciences/22 software for expressing the significance of the present paper. The values were expressed as the means±SD and P values <0.05 were considered as significant.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis and characterisation of AgNPs

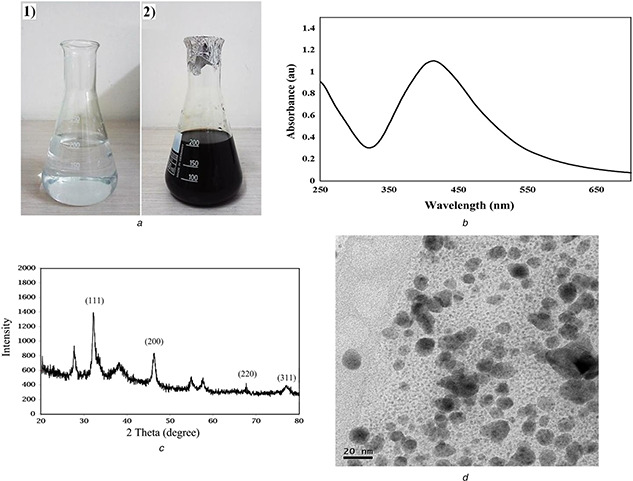

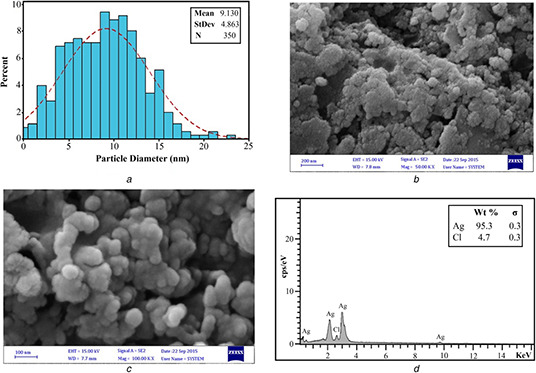

In the current paper, AgNPs were synthesised from the ethanolic extract of A. quttensis which acts as a capping and reducing agent. A. quttensis plant is cheap, easily available, and so far there is no report demonstrating the use of A. quttensis for the synthesis of AgNPs. It was demonstrated that the reduction of Ag+ ions into AgNPs was confirmed by the change of the AgNO3 solution to a dark brown colour within 2 min at room temperature, whereas the control AgNO3 solution (without the aqueous extract) showed no change in colour (Fig. 1 a). This characteristic difference in colour is due to the excitation of the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) in the metal NPs. In previous studies on the phyto‐synthesis of AgNPs using Artemisia species, the rate of the reaction is low and it may take several hours to complete the reaction. In 2014, Basavegowda et al. [19] reported the preparation of Ag and gold NPs using A. annua extract within 10 min at room temperature. In this paper, it was reported that the rate of the reaction for the synthesis was increased and it was completed within 2 min. Furthermore, it can be assumed that the flavonoid acids and phenolic acids existing in the A. quttensis extract may play a role as reducing and capping agents. The formation and stability of AgNPs in an aqueous solution was monitored using UV–vis spectroscopy analysis. The extract, when reacted with Ag+ ions, reduces the precursor solution and lead to the synthesis of NPs as monitored by using UV–vis spectral analysis. The absorption spectra of the NPs were observed close to 437 nm based on SPR of AgNPs (Fig. 1 b). The XRD pattern of the prepared Ag nanostructure produced by the A. quttensis extract was further displayed and approved by the characteristic peaks monitored in the XRD analysis (Fig. 1 c). The XRD pattern demonstrated four intense peaks at 38, 46, 67.4, and 78 corresponding to 111, 200, 220, and 311 in the whole spectrum of 2θ value ranging from 20 to 80 and indicating the face‐centred cubic nature of AgNPs. This pattern clearly revealed that the AgNPs by green method are nanocrystalline in nature. In present paper, the results are in agreement with different reports that investigated the cubic nature of phyto‐synthesised AgNPs [23]. The prepared AgNPs were characterised using TEM. Fig. 1 d illustrates TEM micrographs, which demonstrates that the AgNPs formed are spherical and were in the range of 5–25 nm. The histogram size of AgNPs (illustrated in Fig. 2 a) indicated that the particles have an average size of 9.13 ± 4.86 nm. The SEM images of AgNPs are depicted in Figs. 2 b and c. The fabricated AgNPs are in the nano range with spherical shapes. Fig. 2 d demonstrates the elemental composition profile of the AgNPs by energy‐dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) spectrum analysis.

Fig. 1.

Characterisation of prepared AgNPs

(a) Photograph showing colour change in aqueous solution of AgNO3 with A. quttensis extract: (1) before adding the extract and (2) after addition of extract at 2 min, (b) UV–vis spectra peak of prepared AgNPs from aqueous A. quttensis extract, (c) XRD patterns of AgNPs synthesised by A. quttensis extract, (d) TEM image of AgNPs synthesised from aqueous extract of A. quttensis

Fig. 2.

Determination of AgNPs

(a) Particle size distribution of AgNPs synthesised by A. quttensis extract, (b), (c) FE‐SEM images of synthesised AgNPs using extract of A. quttensis, (d) Energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectrum of AgNPs

The intense peak at ∼3 keV strongly indicates that metallic Ag was the major element of these NPs, as it has optical absorption in this range due to the SPR [24]. The other signals such as chlorine indicate the existence of plant extract, which corresponds to the biomolecules that were capping over the AgNPs.

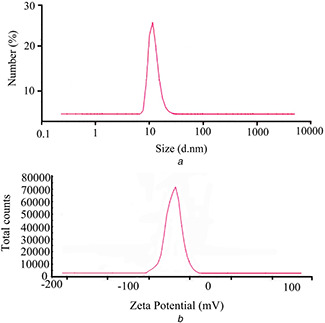

The average size distribution of AgNPs in solution was determined as 10.89 ± 8.09 nm (Fig. 3 a). Also, the surface charges of AgNPs were calculated by zeta‐potential value. A negative zeta potential of about −20.6 ± 0.89 mV was recorded in our paper which suggests higher stability of synthesised AgNPs (Fig. 3 b).

Fig. 3.

Dynamic light scattering analysis

(a) Particle size distribution measurements, (b) Zeta‐potential micrograph of AgNPs synthesised using A. quttensis extract

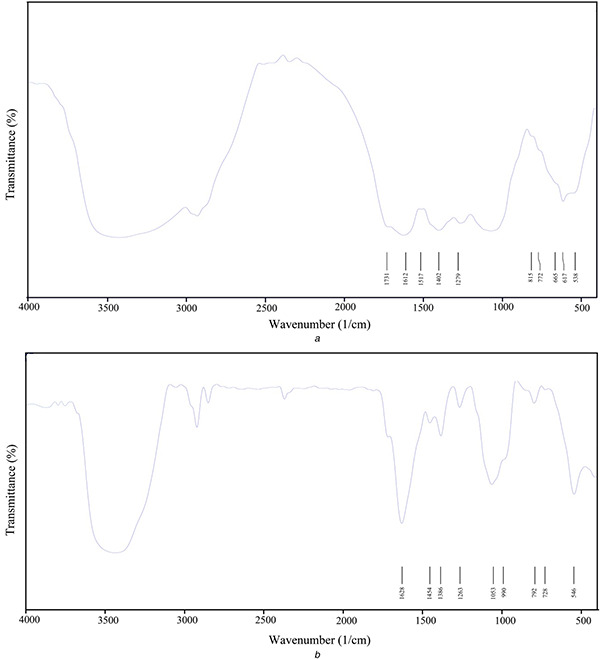

The FT‐IR measurement of both the aqueous A. quttensis aerial parts extract and prepared AgNPs were recorded to identify potential biomolecules involved in stabilising and capping the AgNPs. The spectrum of aqueous A. quttensis aerial parts extract (Fig. 4 a) and AgNPs (Fig. 4 b) reveals shift in the following peaks 3446–3463, 2981–2929, 1612–1628, 1402–1386, 1089–1053, 628–792, and 538–546 cm−1. The band 3446 observed in the extract was as a result of the O–H stretching vibration of phenols and alcohols which shifted to higher‐frequency regions (3463 cm−1) in AgNPs. The absorption peak at 2981 cm−1 observed in the extract was attributed to the alkane C–H stretching vibrations which shifted to lower frequency (2929 cm−1) in AgNPs. The band 1612 cm−1 in the extract was attributed to the presence of amide I vibrations and was shifted to 1628 cm−1 in AgNPs due to proteins that might possibly bind to AgNPs through the amine groups [25, 26]. The band observed at 1402 cm−1 indicates C–H stretching of aldehydic and was shifted to lower frequency (1386 cm−1) in AgNPs, when compared with the A. quttensis extract. The intense band shift at 1053 cm−1 is because of the C–O stretching vibration in functional group with AgNPs. The result clearly suggests that the observation peaks could be attributed to phytochemical constituents, phenolic, alkaloids compounds, carbohydrates, and amino acids present in A. quttensis extract, which might play an effective role in phyto‐synthesis and long‐term stability of AgNPs.

Fig. 4.

FT‐IR spectrum

(a) A. quttensis extract, (b) Phyto‐synthesised AgNPs

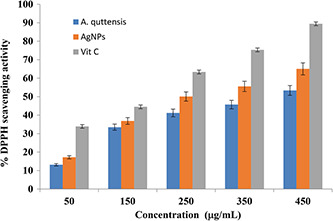

3.2 DPPH free radical scavenging assay

Antioxidants have a pivotal role in protecting the cell from damage leading to oxidative stress produced by free radical. The antioxidant capacity of the AgNPs and A. quttensis ethanolic extract was evaluated using DPPH scavenging assay. The effect of various concentrations of plant extract and AgNPs on DPPH radical SA is illustrated in Fig. 5. The free radical scavenging assay results indicated that the percentage of inhibition increases with enhances in concentration of A. quttensis extract and produced AgNPs. The IC50 values of prepared AgNPs, aqueous extract, and vitamin C are shown in Table 1. There was a dose‐dependent increase in the percentage inhibition of prepared AgNPs and aqueous extract.

Fig. 5.

DPPH radical SA of A. quttensis, AgNPs, and vitamin C

Table 1.

Quantitative screening of antioxidant activity of AgNPs and A. quttensis extract by DPPH assay

| Compound | Absorbance | Absorbance at 517 nm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 μg/ml | 150 μg/ml | 250 μg/ml | 350 μg/ml | 450 μg/ml | IC50 (μg/ml) | ||

| control | (AbsControl) | 1.422 ± 0.03 | 1.422 ± 0.03 | 1.422 ± 0.03 | 1.422 ± 0.03 | 1.422 ± 0.03 | |

| extract | (AbsSample) | 1.228 ± 0.02 | 0.939 ± 0.01 | 0.829 ± 0.07 | 0.772 ± 0.02 | 0.663 ± 0.01 | |

| SA% | 13.15 | 33.47 | 41.20 | 45.71 | 53.37 | 386 μg | |

| AgNPs | (AbsSample) | 1.17 ± 0.02 | 0.891 ± 0.01 | 0.703 ± 0.05 | 0.632 ± 0.03 | 0.497 ± 0.03 | |

| SA% | 17.22 | 36.84 | 50.07 | 55.56 | 65.04 | 294 μg | |

| vitamin C | (AbsSample) | 0.94 ± 0.03 | 0.789 ± 0.05 | 0.521 ± 0.07 | 0.351 ± 0.01 | 0.150 ± 0.03 | |

| SA% | 33.89 | 44.51 | 63.36 | 75.31 | 89.45 | 170 μg | |

Each value represents the mean±standard error (SE) of the mean.

SA%: scavenging activity.

The percentage inhibition value for the lowest concentration (50 μg/ml) of the aqueous extract was 13.15% and this value was increased to 53.37% when the concentration was increased to 450 μg/ml. However, for AgNPs, the recorded values (percentage inhibition) were 17.22 and 65.04 for the concentration of 50 and 450 μg/ml, respectively.

Although the DPPH radical SA of A. quttensis aqueous extract and AgNPs were comparable, the synthesised AgNPs was indicated as 65% higher activity at 450 μg/ml and it was lower than that of vitamin C at 450 μg/ml (89.45%). Therefore, the synthesised AgNPs revealed better antioxidant activity in comparison with aqueous extract of A. quttensis. Since the intercalation of bio‐extract compounds was present in A. quttensis aqueous extract. It has been reported that the possible mechanism of antioxidant activity of AgNPs includes electron donating ability, reductive ability, and scavengers of radicals [27]. Similar reports with enhanced antiradical agents of AgNPs from leaves extract have been investigated, and also enhanced DPPH scavenging properties by selenium, torolex, platinum, and chitosan‐coated gold NPs [28, 29, 30] have been reported.

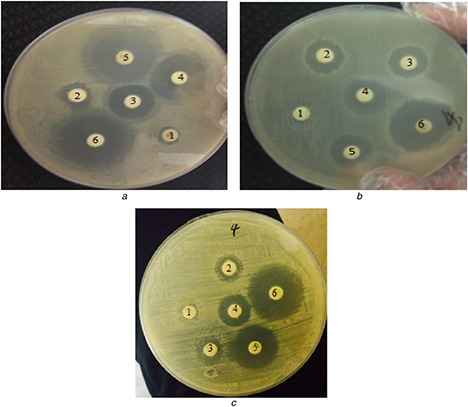

3.3 Antibacterial activity of AgNPs

Owing to increase in antibiotic and metal ions resistance in bacteria, scientists have focused on the development of other methods such as NPs for killing the pathogenic bacteria [24]. In this report, the anti‐microbial property of AgNPs against different pathogenic organisms including S. aureus, P. aeroginosa, and E. coli was studied. Compared with the control (distillated water), the diameters of inhibition zones increased for the test organisms. The Gram negative bacteria (P. aeruginosa and E. coli) showed larger zones of inhibition, compared with the Gram positive bacteria (S. aureus) (Fig. 6), which maybe due to the differences in cell wall composition. Also, the data of inhibition properties are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 6.

Antibacterial activity of synthesised AgNPs against bacteria

(1) Negative control (distiled water as control), (2) 10 µg Ag, (3) 20 µg Ag, (4) 30 µg Ag, (5) 40 µg Ag, and (6) ampicillin

(a) P. aeroginosa, (b) S. aureus, (c) E. coli

Table 2.

Disc diffusion assay of AgNPs against pathogenic bacteria and ampicillin as a positive control

| AgNPs concentration, μg/ml | Zone of inhibition (mm±SE) against human pathogenic bacteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeroginosa | S. aureus | E. coli | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 2.6 ± 0.28 | 4.3 ± 0.22 | 3.5 ± 0.89 |

| 20 | 5.3 ± 0.76 | 5.1 ± 0.64 | 5.2 ± 0.72 |

| 30 | 9.8 ± 0.56 | 5.8 ± 0.79 | 6.3 ± 0.38 |

| 40 | 13.7 ± 0.66 | 7.1 ± 0.49 | 10.4 ± 0.65 |

| ampicillin | 15.6 ± 0.32 | 14.2 ± 0.98 | 15.8 ± 0.71 |

SE = standard error. Each value represents the mean±SE of three replicates.

It can be inferred from the antibacterial activity data that it was dose dependent and the highest antibacterial action was observed against P. aeroginosa. In general, the antibacterial mechanism of the AgNPs is still unknown. However, more studies have suggested that, when bacteria are treated with Ag ions, DNA replication, respiratory function, and permeability of the bacterial cells become unstable. The results reflect that AgNPs fabricated using A. quttensis have excellent antibacterial activity which leads to defecating of protein and DNA synthesis process in bacterial cells [31, 32]. In addition, the cell wall structure of Gram negative bacteria facilitates Ag+ transfer to the cytoplasmic membrane compared with the Gram positive bacteria.

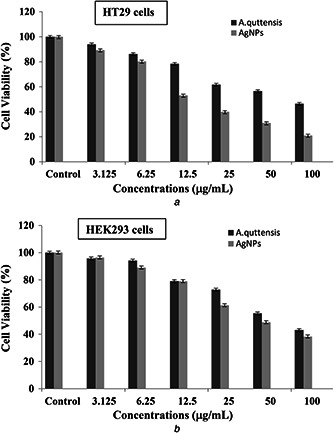

3.4 Determination of cytotoxic effect of synthesised AgNPs

MTT assay was performed to investigate the in vitro cytotoxic property of A. quttensis aqueous extract and AgNPs (Figs. 7 a and b). Both the HT29 and HEK293 cells were treated with a concentration of 3.125–100 μg/ml of the A. quttensis and synthesised AgNPs for 24 h to determine the inhibitory percentage against cancer treated and untreated cell lines. Our results indicated that the cancerand normal cell viability was clearly proportional to the concentration of the AgNPs and A. quttensis aqueous extract.

Fig. 7.

Cytotoxicity effects of A. quttensis extract and synthesised AgNPs against HT29 and normal HEK293 cell line after 24 h treatment

(a) Cytotoxic effect of AgNPs and A. quttensis aqueous extract on cancer cell line (HT29), (b) Cytotoxic effect of AgNPs and A. quttensis aqueous extract on normal HEK293 cell line. Data are expressed as means±SD of three experiments. Percentages of inhibitions are expressed relative to untreated controls

The relevant IC50 values of the HT29 cells and HEK293 cells were 58.18; 38.55 and 59.97; 54.61 μg/ml for A. quttensis extract and prepared AgNPs, respectively. When the IC50 of the AgNPs and extract was compared, the synthesised AgNPs demonstrated higher percentage of cell growth inhibition at lower concentration against the HT29 cancer cells than the A. quttensis extract. At lower concentrations the extract did not display significant toxicity on the growth of HT29 cells but the cell viability significantly decreases with high concentrations at 50–100 μg/ml. Data obviously reveals that the cytotoxicity analysis of AgNPs shows a dose–response relationship and cytotoxicity increased at higher concentrations. Once the concentration of NPs was up to 100 μg/ml, there were 54% dead cells. Among the NP and extract tested, AgNPs were found to be best for high cell growth inhibition percentage. It might be due to the synergetic properties of bio‐molecular groups derived from A. quttensis that adhered in the process of NP synthesis. This is the first comparative investigation to introduce the cytotoxicity of phyto‐synthesised AgNPs using aqueous ethanolic extract of A. quttensis against HT29 and normal HEK293 cells. Further reports have clarified that AgNPs were taken up by mammalian cells by utilising various mechanisms including pinocytosis, phagocytosis, and endocytosis and interact with the cellular material [33, 34, 35, 36]. The size, shape, and charge of metallic NPs are respective significant aspects that impact the cytotoxicity of NPs by enhancing the key events in activation of pivotal step of apoptosis [37]. From our results, it is recommended that phyto‐synthesis of AgNPs could have damaged the DNA and/or mitochondria‐dependent (intrinsic) apoptosis pathway and changed in the cell morphology, which is one of the critical suggested mechanisms of cell death.

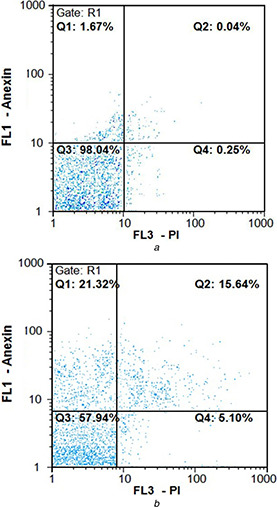

3.5 In vitro apoptosis/necrosis assay

To determine the apoptosis induced by AgNPs in HT29 cells, they were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate Annexin V with PI, followed by flow cytometry. A representative result of flow cytometry is illustrated in Fig. 8. The upper left quadrant (Q 1) represents the percentage of late apoptotic cells (Annexin V‐FITC stained cells) and the Q 4 (lower‐right quadrant) depicts the percentage of early apoptotic cells (Annexin V‐FITC and PI stained cells). The upper right and left quadrants have totally apoptotic cells. According to Annexin V/PI assay results, many number of apoptotic cells were observed in the HT29 cells treated with IC50 concentration (38.55 μg/ml) of AgNPs, demonstrating the distribution of cells in early and late stages of apoptosis. Figs. 8 a and b reveal that there are about 2.13 and 36.96% increase in early and late apoptotic cell population in treated HT29 cells, respectively, compared with untreated ones in HT29 cell line. These results demonstrated that phyto‐synthesised AgNPs toward HT29 cells was mainly achieved by its ability to induce apoptosis pathway rather than necrosis.

Fig. 8.

Flow cytometric analysis by Annexin V‐fluorescein (fluorescence 1) in the y‐axis and PI (FL3) in the x‐axis double staining of HT29 cell line treated with green synthesised AgNPs after 24 h exposure. Dot plots of Annexin V/PI staining are shown in

(a) Untreated HT29 cells, (b) HT29 cells treated with IC50 concentration of AgNPs exhibited 15.64% early stage apoptosis and 21.32% late stage apoptosis

4 Conclusions

This is the first study to develop cost‐effective, simple, and eco‐friendly approach for phyto‐synthesis of AgNPs using A. quttensis Podlech aerial parts ethanol extract as a capping and reducing agent. Interestingly, AgNPs were prepared rapidly with 2 min of incubation period making it one of the fastest bioreducing methods for synthesis of AgNPs. The characterisation of phyto‐synthesised AgNPs were determined using UV–vis spectroscopic, XRD analysis, FE‐SEM, EDS, TEM, Dynamic Light Scattering, zeta potential, and FT‐IR; these procedures proved the presence of AgNPs with an average size of 5–25 nm. The prepared AgNPs demonstrated better promising antiradical potential than the A. quttensis ethanol extract alone and can be used in nutraceutical and biopharmaceutical industries. The AgNPs showed considerable antibacterial property against both Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. However, stronger inhibition was monitored in P. aeruginosa as Gram negative bacteria compared with Gram positive bacteria. The phyto‐synthesised AgNPs possessed powerful cytotoxic effect against HT29 cell line compared with A. quttensis aqueous extract. Furthermore, the Annexin V/PI staining results demonstrated that the cytotoxicity of AgNPs toward HT29 cells was mainly achieved through its ability to induce apoptosis pathway rather than necrosis. Therefore, further investigations are needed to completely elucidate the toxicity and the mechanisms involved in the anti‐microbial and anticancer properties of AgNPs.

5 Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Mehdi Shafiee Ardestani from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences and facilities received in support for carrying out this research on phyto‐synthesis of silver nanoparticles in simple and an eco‐friendly route for adding value to its biomedical utilities.

6 References

- 1. Gurunathan S. Lee K.J. Kalishwaralal K. et al.: ‘Anti angiogenic properties of silver nanoparticles’, Biomaterials, 2009, 30, pp. 6341 –6350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oei J.D. Zhao W.W. Chu L. et al.: ‘Antimicrobial acrylic materials with in situ generated silver nanoparticles’, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B, Appl. Biomater., 2012, 100, pp. 409 –415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kalishwaralal K. Banumathi E. Pandian S.R.K. et al.: ‘Silver nanoparticles inhibit VEGF induced cell proliferation and migration in bovine retinal endothelial cells’, Colloids Surf. B, Biointerfaces, 2009, 73, pp. 51 –57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ezzatzadeh E. Farjam M.H. Rustaiyan A.: ‘Comparative evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of crude extract and secondary metabolites isolated from Artemisi kulbadic ’, Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis., 2012, 2, pp. 431 –434 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tao A. Sinsermsuksaku P. Yang P.: ‘Polyhedral silver nanocrystals with distinct scattering signatures’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2006, 45, pp. 4597 –4601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li K. Zhang F.S.: ‘A novel approach for preparing silver nanoparticles under electron beam irradiation’, J. Nanoparticle Res., 2010, 12, pp. 1423 –1428 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Malice K. Witcombb M.S. Scurrella M.S.: ‘Self‐assembly of silver nanoparticles in a polymer solvent: formation of a nano chain through nanoscale soldering’, Mater. Chem. Phys., 2005, 90, pp. 221 –224 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Le A.T. Tam L.T. Tam P.D. et al.: ‘Synthesis of oleic acid‐stabilized silver nanoparticles and analysis of their antibacterial activity’, Mater. Sci. Eng. C, 2010, 30, pp. 910 –916 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zamiri R. Zakaria A. Abbastabar H. et al.: ‘Laser‐fabricated cost or oil‐capped silver nanoparticles’, Int. J. Nanomed., 2011, 6, pp. 565 –568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nadagouda M.N. Speth T.F. Varma R.S.: ‘Microwave‐assisted green synthesis of silver nanostructures’, Acc. Chem. Res., 2011, 44, pp. 469 –478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hutchison J.E.: ‘Greener nanoscience: a proactive approach to advancing applications and reducing implications of nanotechnology’, ACS Nano, 2008, 2, pp. 395 –402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mervat F. Zayed W.H. Eisa W.H. et al.: ‘ Malva parviflora extract assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles’, Spectrochim. Acta, Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc., 2012, 98, pp. 423 –428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baharara J. Namvar F. Ramezani T. et al.: ‘Silver nanoparticles biosynthesized using Achillea biebersteinii flower extract: apoptosis induction in MCF‐7 cells via caspase activation and regulation of bax and Bcl‐2 gene expression’, Molecules, 2015, 20, pp. 2693 –2706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nasrabadi M.R. Pourmortazavi S.M. Shandiz S.A.S. et al.: ‘Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Eucalyptus leucoxylon leaves extract and evaluating the antioxidant activities of extract’, Nat. Prod. Res., 2014, 28, pp. 1964 –1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rokiyaraj S.A. Arasu M.V. Vincent S. et al.: ‘Rapid green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Chrysanthemum indicum L and its antibacterial and cytotoxic effects: an in vitro study’, Int. J. Nanomed., 2014, 9, pp. 379 –388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Murugan K. Senthilkumar B. Senbagam D. et al.: ‘Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Acacia leucophloea extract and their antibacterial activity’, Int. J. Nanomed., 2014, 9, pp. 2431 –2438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salehi S. Mirzaie A. Shandiz S.A.S. et al.: ‘Chemical composition, antioxidant, antibacterial and cytotoxic effects of Artemisia marschalliana Sprengel extract’, Nat. Prod. Res., 2016, 4, pp. 469 –472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nahrevanian H. Milan B.S. Kazemi M. et al.: ‘Antimalarial effects of Iranian flora Artemisia sieberi on Plasmodium berghei in vivo in mice and phytochemistry analysis of its herbal extracts’, Malar. Res. Treat., 2012, 2012, 727032, doi: 10.1155/2012/727032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Basavegowda N. Idhayadhulla A. Lee Y.R.: ‘Preparation of Au and Ag nanoparticles using Artemisia annua and their in vitro antibacterial and tyrosinase inhibitory activities’, Mater. Sci. Eng. C, 2014, 43, pp. 58 –64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khatoon N. Ahmad R. Sardar M.: ‘Robust and fluorescent silver nanoparticles using Artemisia annua: biosynthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity’, Biochem. Eng. J., 2015, 102, pp. 91 –97 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shandiz S.A.S. Shafiee Ardestani M. Irani S.H. et al.: ‘Imatinib induces down regulation of Bcl‐2 an anti‐apoptotic protein in prostate cancer PC‐3 cell line’, Adv. Stud. Biol., 2015, 7, pp. 17 –27 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shandiz S.A.S. Khosravani M. Mohammadi S. et al.: ‘Evaluation of imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) on KAI1/CD82 gene expression in breast cancer MCF‐7 cells using quantitative real‐time PCR’, Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed., 2016, 2, pp. 159 –163 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ghorbani P. Soltani M. Homayouni‐Tabrizi M. et al.: ‘Sumac silver novel biodegradable nano composite for bio‐medical application: antibacterial activity’, Molecules, 2015, 20, pp. 12946 –12958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Puiso J. EJonkuviene D. Macioniene I. et al.: ‘Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using lingonberry and cranberry juices and their antimicrobial activity’, Colloids Surf. B, Biointerfaces, 2014, 121, pp. 214 –221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salehi S. Shandiz S.A.S. Ghanbar F. et al.: ‘Phyto‐synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Artemisia marschalliana Sprengel aerial parts extract and assessment of their antioxidant, anticancer, and antibacterial properties’, Int. J. Nanomed., 2016, 11, pp. 1835 –1846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sharbidre A.A. Kasote D.M.: ‘Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using flaxseed hydroalcoholic extract and its antimicrobial activity’, Curr. Biotechnol., 2013, 2, pp. 162 –166 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sivanandam V. Purushothaman M. Karunanithi M.: ‘Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plant leaf extract and evaluation of their antibacterial and in vitro antioxidant activity’, Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed., 2012, 1, pp. 1 –8 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gao X.Y. Zhang J. Zhang L.: ‘Hollow sphere selenium nanoparticles: their in vitro anti hydroxyl radical effect’, Adv. Mater., 2002, 14, pp. 290 –293 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saikia J.P. Paul S. Konwar B.K. et al.: ‘Nickel oxide nanoparticles: a novel antioxidant’, Colloids Surf. B, Biointerfaces, 2010, 15, pp. 146 –148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nie Z. Liu K.J. Zhong C.J. et al.: ‘Enhanced radical scavenging activity by antioxidant‐functionalized gold nanoparticles: a novel inspiration for development of new artificial antioxidants’, Free Radic. Biol. Med., 2007, 9, pp. 1243 –1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sondi I. Salopek‐Sondi B.: ‘Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: a case study on E. coli as a model for Gram‐negative bacteria’, J. Colloid Interface Sci., 2004, 275, pp. 177 –182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feng Q.L. Wu J. Chen G.Q. et al.: ‘Mechanistic study of the antibacterial effect of silver ions on Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus’ , J. Biomed. Mater. Res., 2000, 52, pp. 662 –668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patel B. Shah V.R. Bavadekar S.A.: ‘Anti‐proliferative effects of carvacrol on human prostate cancer cell line, LNCaP’, FASEB J., 2012, 26, pp. 1037 –1035 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vivek R. Thangam R. Muthuchelian K. et al.: ‘Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Annona squamosa leaf extract and it's in vitro cytotoxic effect on MCF‐7 cells’, Process. Biochem., 2012, 47, pp. 2405 –2410 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sankar R. Karthik A. Prabu A. et al.: ‘ Origanum vulgare mediated biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles for its antibacterial and anticancer activity’, Colloids Surf. B, Biointerfaces, 2013, 108, pp. 80 –84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tiwari D.K. Jin T. Behari J.: ‘Dose‐dependent in‐vivo toxicity assessment of silver nanoparticle in Wistar rats’, Toxicol. Mech. Methods, 2011, 21, pp. 13 –24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang G. Gurtu V. Kain S.R. et al.: ‘Early detection of apoptosis using a fluorescent conjugate of annexin V’, Biotechniques, 1997, 23, pp. 525 –531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]