Abstract

The present study reports on biogenic‐synthesised silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) derived by treating Ag ions with an extract of Cassia fistula leaf, a popular Indian medicinal plant found in natural habitation. The progress of biogenic synthesis was monitored time to time using a ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy. The effect of phytochemicals present in C. fistula including flavonoids, tannins, phenolic compounds and alkaloids on the homogeneous growth of AgNPs was investigated by Fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy. The dynamic light scattering studies have revealed an average size and surface Zeta potential of the NPs as, −39.5 nm and −21.6 mV, respectively. The potential antibacterial and antifungal activities of the AgNPs were evaluated against Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Candida kruseii and Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Moreover, their strong antioxidant capability was determined by radical scavenging methods (1,1‐diphenyl‐2‐picryl‐hydrazil assay). Furthermore, the AgNPs displayed an effective cytotoxicity against A‐431 skin cancer cell line by 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay, with the inhibitory concentration (IC50) predicted as, 92.2 ± 1.2 μg/ml. The biogenically derived AgNPs could find immense scope as antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer agents apart from their potential use in chemical sensors and translational medicine.

Inspec keywords: antibacterial activity, biomedical materials, cancer, cellular biophysics, electrokinetic effects, Fourier transform infrared spectra, light scattering, microorganisms, nanomedicine, nanoparticles, silver, skin, spectrochemical analysis, toxicology, ultraviolet spectra, visible spectra

Other keywords: Ag; voltage ‐21.6 mV; size ‐39.5 nm; A‐431 skin cancer cell line; cytotoxicity; 1,1‐diphenyl‐2‐picryl‐hydrazil assay; radical scavenging methods; Trichophyton mentagrophytes; Candida kruseii; Staphylococcus aureus; Bacillus subtilis; surface zeta potential; dynamic light scattering studies; Fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy; alkaloids; phenolic compounds; tannins; flavonoids; phytochemical effect; ultraviolet‐visible spectroscopy; Cassia fistula leaf extract; biogenic‐synthesised silver nanoparticles; cytotoxic activities; antimicrobial activities; antioxidant activities

1 Introduction

In the recent past, metallic nanoparticles (NPs) have received significant attention by the scientific community due to their ever‐emerging, multifaceted and fascinating applications in diverse fields including biomedical sciences and engineering [1, 2, 3, 4]. For instance, the unique optoelectronic and physicochemical properties of noble metal NPs have already been exploited for the purpose of drug delivery [5], tissue/tumour imaging [6], biosensing [7] and catalysis [8] as well as in biosensors based on surface‐enhanced Raman scattering [9]. The conventional methods that are in practice for synthesising NPs involve toxic chemicals, hazardous conditions and costly apparatus. In contrast, green synthesis of metallic NPs normally involves biocompatible ingredients in physiological environment at ambient temperature and pressure. Moreover, the bioactive molecules found in the green route act as functionalising ligands, thereby making these NPs more appropriate to meet biomedical standards [10].

Plants have potential to overcome the inherent problem of toxicity associated with most of the traditional routes. It is worth mentioning here that different‐shaped polyol and water‐soluble heterocyclic components of the plant biomolecules, while possessing both protective and reductive activities, can be responsible for the reduction of Ag+ and Au+ while undertaking processing through chemical and radiation treatments [4, 11].

Cassia fistula is widely used in Indian literature in the treatment of common and acute diseases. The leaves are laxative and used externally as emollient, a poultice is used for chilblains, in insect bites, swelling, rheumatism and facial paralysis [12]. Leaves are used in jaundice, piles, rheumatism, ulcers and also externally skin eruptions, ring worms and eczema. The leaves and bark mixed with oil are applied to pustules, burns and insect bites [13]. The leaves and the flowers are both purgative like the pulp [13]. In the Indian literature, this plant also offers proven remedial measures against skin diseases, liver troubles, tuberculous glands and its use in the treatment of haematemesis, pruritus, leucoderm and diabetes [14, 15]. The leaf extract is also recommended for its antitussive and wound healing capabilities [16, 17]. The plant has diverse ethnomedicinal uses by the tribal of Similipal biosphere reserve (SBR). While the leaf paste is orally taken to purify blood, roots can be consumed to combat common cold [18]. To cure the area of insect bite, the bark paste is normally applied externally 2 to 3 times a day in regular intervals for 3 days. Similarly, to cure jaundice a half teaspoon juice extract is taken orally thrice a day. The leaf paste along with neem is applied externally over all types of skin infections [19]. To get relief from snakebite, decoction of mixture containing roots along with equal quantity of roots of Stereospermum chelonoides, latex of Calotropis gigantea and stem juice of Musa paradisiaca are carefully mixed with black pepper and is prescribed twice a day for 2 to 3 days [20]. Leaves are even used to cure dysentery with absolute certainty [21].

In the present paper, C. fistula extract is shown to act as a facilitator for reducing silver (Ag) ions and form AgNPs. These biogenic‐synthesised AgNPs were examined by a number of spectroscopy tools and techniques in order to extract information with respect to (w.r.t.) absorption and molecular vibrational features. Finally, antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic potentials were evaluated on a qualitative basis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Synthesis of AgNPs using plant extracts

2.1.1 Collection and identification of plants

Fresh leaves of C. fistula were collected from the SBR in the year 2013 during the months of September–December. The SBR (21°‐28′ and 22°‐08′ North latitude and 86°‐04′ and 86°‐37′ East longitude) is stretched over an approximate area of 5569 km2, geographically located in the central part of Mayurbhanj district of the Odisha state and known for its natural flora and fauna [21]. The identified plant specimen (NOU 425) was registered in the Department of Botany, North Orissa University (NOU). The healthy leaves were shade dried, powdered mechanically by a grinder followed by sieving in order to get uniform size.

2.1.2 Preparation of plant extract

About 5 g of leaf powder was added to 50 ml of sterile distilled water and sonicated for 20 min. The sonicated extracts were purified by centrifugation (∼5000 rpm). The purified extracts were filtered through Whatman filter® paper and the filtrate were stored at 4°C.

2.1.3 Biosynthesis of AgNPs

The reaction mixture was prepared in a clean glass test tube, by adding 0.5 ml of the aqueous extract and 4.5 ml of 1 mM aqueous Ag nitrate (AgNO3) solution. On the contrary, 0.5 ml of aqueous leaf extracts with 4.5 ml distilled water (as control), both the mixtures were kept under dark overnight at room temperature. On completion of the biogenic reaction, the precursor was subjected to continuous centrifugation with sterile distilled water. The AgNPs were separated from the mixture and purified through repeated centrifugation. The AgNPs were characterised through different techniques for their assessment w.r.t. antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities.

2.2 Characterisation of AgNPs

2.2.1 Ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy

Regarding synthesis of AgNPs, the absorbance response of the bioreduction of the Ag+ ions in aqueous solution was monitored by a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Lambda 35® Perkin Elmer, USA). The response was noted in the wavelength range of 400–600 nm, operated at room temperature (25°C).

2.2.2 Dynamic light scattering (DLS) spectroscopy

The particle size and Zeta potential of the AgNPs were analysed by a Zetasizer (Zs 90, Malvern, UK) working at room temperature. The dried samples were adequately diluted with phosphate buffer saline (0.15M, pH 7.2). The aliquots were then sampled for further experimentation with the DLS instrument. The particle size distribution was assessed at a scattering angle of 90°.

2.2.3 Fourier‐transform infra‐red spectroscopy

The vibrational spectra of the AgNPs precursors were obtained by using a Fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (8400S, Shimadzu) and acquiring data in transmission (%) mode. The AgNPs were first pelletised with KBr and having 1% sample concentration (w/w), and then analysed against the background of pure KBr pellet.

2.2.4 Field emission scanning electron microscopy

The nano‐dimensional feature of the synthesised AgNPs was ensured by employing a field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE‐SEM) (INSPECT F50, FEI, The Netherlands) operated at potential difference of 20 kV and with an emission current of ∼210 μA.

2.2.5 Qualitative phytochemical analysis

Qualitative phytochemical analyses were carried out following the procedure of Trease and Evans [22] and Panda and Dutta [23].

2.2.6 Quantitative phytochemical analysis and antioxidant properties

Total phenolics content (TPC) determination: The total amount of phenolics in the extract was determined by using popular Folin–Ciocalteu method and with suitable modification [24]. All estimates were carried out in triplicates. The TPC was expressed as gallic acid equivalent (GAE) in milligram/gram (mg/g) sample.

Total flavonoids content (TFC) determination: The amounts of total flavonoids were determined by a modified aluminium chloride method [25]. All determinations were carried out in triplicates. The TFC was expressed as GAE in mg/g sample.

Quantification of radical scavenging activity [1, 1‐diphenyl‐2‐picryl‐hydrazil (DPPH)]: The antioxidant activity was determined by DPPH radical scavenging assay with adequate modification wherever found necessary [24]. The results were expressed in percentage of radical scavenging activity using butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) as standard.

2.2.7 Antimicrobial activity

Microbial strains: Bacterial strains: namely, Bacillus subtilis [microbial type culture collection (MTCC) 736], Staphylococcus aureus (MTCC 737), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MTCC 424) and Escherichia coli (MTCC 443) and fungal strains such as Candida albicans (MTCC 227), Candida kruseii (MTCC 9215), Candida viswanathii (MTCC 1929), and Trichophyton mentagrophytes (MTCC 8476) were used for the antibacterial and antifungal tests. For bacteria, colonies were inoculated on Mueller–Hinton (MH) agar plates while for fungi colonies were inoculated on potato dextrose agar (PDA), and after growth both were stored in a cold room (∼4°C).

Preparation of pre‐culture: A single colony of each test strains was inoculated from PDA (10% potato and 2% dextrose; PDA) for fungus and MH agar (0.2% beef extract, 1.75% casamino acids and 0.015% soluble starch) for bacteria in two different reaction tubes containing 1 ml of respective broth under aseptic conditions. The reaction tubes were incubated overnight with 200 rpm at 37°C for bacteria and 32°C for fungi.

Agar‐cup method: The agar‐cup method was used to study antimicrobial activity of the synthesised AgNPs following standard protocols [26]. To test antimicrobial activity, MH broth culture (100 µl) of each test bacteria was seeded over the Muller Hinton Agar (MHA) plates, whereas for fungus 200 µl of overnight PD broth were seeded over PDA plates. Wells of ∼6 mm in diameter and 2.5 mm deep were made on the surface of the solid medium using a sterile borer. Each well was filled with 40 µl of biogenically synthesised AgNPs. Equal amount of AgNO3 solution without plant extracts served as the control while standard antibiotics – gentamicin and clotrimazole were kept as respective reference controls for bacteria and fungi. All the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After proper growth, the plates were removed and zones of inhibition were measured with Himedia antibiotic scale and subsequent results were tabulated. AgNPs with zones of inhibition ≥8 mm diameter were regarded as positive and further studied with broth dilution test. Each experiment was carried out in triplicates. The mean±SD of the zone of inhibitions were taken for calculating the antimicrobial activity of the extracts.

Antibacterial activity test (broth microdilution) protocol: The AgNPs that were stored at 4°C are brought to the ambient temperature prior to the experiment. Two‐fold serial dilutions of the agents were prepared with sterile Millipore water using sterile 96 flat‐bottom well microdilution plates. A standardised inoculum was obtained by growing the test organisms overnight in MH broth and diluting the suspension with MH broth to a turbidity of OD = 0.003 at 600 nm on a Perkin Elmer UV/Vis spectrometer (typically approximately hundred‐fold) (Fig. 1). Each well of a microdilution plate was inoculated with 190 µl of the inoculum and 10 µl of the AgNPs was added. The control wells were prepared with 190 µl MH broth and 10 µl AgNPs in order to correct any absorption due to extract components. After mixing, the plates were properly sealed with parafilms.

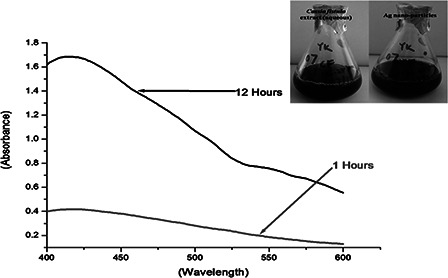

Fig. 1.

UV–Vis spectra of AgNPs synthesised by C. fistula with a processing time

The microdilution trays were placed in a shaker‐incubator at 37°C for 24 h, and then read on a Biorad Microplate Reader at 590 nm. The extent of growth in the wells containing the test sample was compared with the extent of growth in the control. For test validity, acceptable growth (≥0.5 OD) must occur in the positive control well and none (OD < 0.05) in the negative control well (medium only). Tests were carried out in duplicate. The relative inhibition (%) of the test sample was calculated by dividing the OD value of the test sample minus that of the non‐inoculated extract control by the average OD of the solvent control, and multiplying by 100.

Antifungal test: Antifungal activity was tested against Candida species and T. mentagrophytes in a similar way as in bacteria. Instead of MH broth, PD broth was used with a smaller quantity of AgNPs. For antifungal activity, each well of a microdilution plate was inoculated with 190 µl of the inoculum and 10 µl of the test solution. Control wells were loaded with 190 µl PD broth and 10 µl AgNPs to correct any absorption due to extract components.

2.2.8 Cytotoxicity study by 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

The cytotoxic effect of AgNPs synthesised by C. fistula leaf extract was determined by cell viability study with the conventional MTT reduction assay with little modifications [4]. Epidermal carcinoma cells (A‐431, National Center for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India) were seeded in 96 well plates at the density of 3000 cells/well in presence of 200 μl Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution and incubated for 24 h in incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. After 24 h of seeding, the existing media was removed and replaced by fresh media along with different concentrations of AgNPs: namely, 10, 20, 50, 100, 150, 200 and 250 μg/ml and incubated for 48 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. To detect the cell viability, MTT working solution was prepared from a stock solution of 5 mg/ml in a growth medium without FBS to the final concentration of 0.8 mg/ml. About 100 μl of MTT solution was added and incubated for 4 h. After 4 h of incubation, the MTT solution was discarded and 100 μl of Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) solvent was added in each well under dark followed by an incubation of 15 min and the optical density of the formazan product was read at 595 nm in a microplate reader (Biorad, USA).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Optical and microscopic analysis of biogenically derived AgNPs

The as grown AgNPs exhibited a characteristic absorption peak at ∼421 nm. The AgNPs would give an absorption band in the range of ∼420–430 nm due to its surface plasmon resonance character in consistency with others work [4]. The absorption response was found to be much stronger for a longer duration of processing time. The digital image of aqueous C. fistula extract and the AgNP precursor are highlighted as inset.

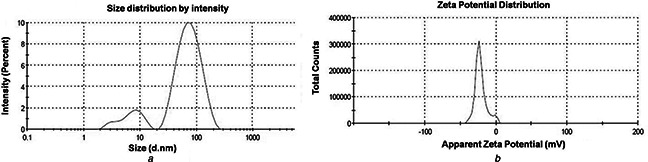

The size distribution and surface Zeta potential analysis were performed on DLS equipment. As regard to size, a bimodal distribution with average sizes ∼10 and ∼65 nm can be found (Fig. 2 a). While low‐end size distribution is relatively asymmetric, the peak representing particles of larger dimension resumes a normal distribution. As evident from Fig. 2 b, the surface Zeta potential stands at −21.6 mV. A small asymmetric peak near zero potential can be assigned to the offset made by electric double layer created by surface adsorbed hydroxyl radicals. The magnitude Zeta potential gives incipient instability condition of the particles in the media; however, the value is good enough to avoid aggregation.

Fig. 2.

a DLS spectra on hydrodynamic size distribution of synthesised AgNPs. The x ‐axis and y ‐axis represents size (nanometres) and intensity (%), respectively

b Characteristic response of Zeta potential (millivolts)

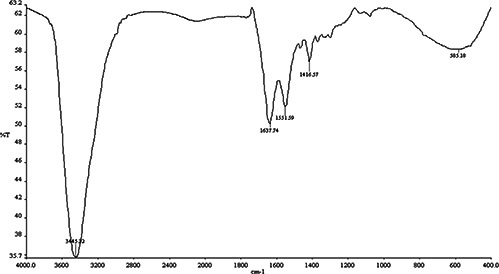

The FTIR spectrum of the AgNPs was acquired in order to reveal the nature of functional groups involved in the biogenic process. In the spectrum, as shown in Fig. 3, five important peaks could be found which are located at ∼3445, 1638, 1552, 1417 and 585 cm−1. A strong absorption peak at ∼3445 cm−1 is assigned to the stretching vibration of hydroxyl group attached to the NP surfaces or present in the ambient environment. The other three bands ∼1637, ∼1552 and ∼1417 cm−1 are due to stretching vibrations of C=O, C–C, C–N and –OH functional groups. The C=O and C–N stretching are generally found in the proteins that participate in the reduction of the metal ions [27]. We speculate that the hydroxyl and carbonyl groups are mainly responsible for synthesising AgNPs.

Fig. 3.

FTIR spectrum of AgNPs synthesised by using C. fistula leaf

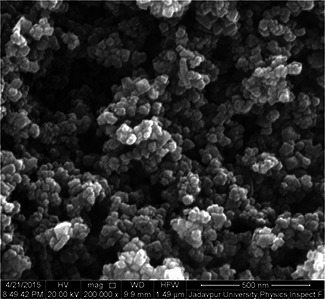

The field emission scanning electron micrograph of the AgNPs can be found in Fig. 4. Nearly spherical morphology with monodispersity nature of the AgNPs and capped with biomoities can be evident from the micrograph. The average size of the particles is found to be in the range of ∼40–50 nm. Note that, hydrodynamic size always overestimates the particle size in view of NP attachment with the surface water, and accordingly we predicted a relatively large particle size through DLS measurements.

Fig. 4.

FE‐SEM image of biogenically derived AgNPs

3.2 Analysis of phytochemicals and antioxidant activity

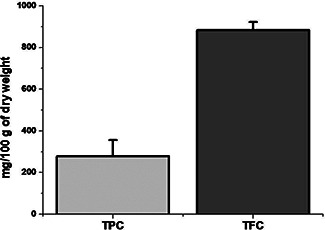

Qualitative and quantitative phytochemical screening of the aqueous extract of C. fistula leaves has been summarised in Fig. 5, Tables 1 and 2. Phytochemical evaluation revealed the presence of alkaloids, proteins, tannins and phenolic compounds, flavonoids while presence of glycoside, steroids and sterols and triterpenoids were believed to be unlikely.

Fig. 5.

Comparative bar diagram showing total TPC and TFC contents of C. fistula

Table 1.

Qualitative phytochemical screening of aqueous extract of C. fistula

| Name of the phytoconstituents | Observation |

|---|---|

| alkaloids | ++ |

| tannins and phenolic compounds | ++ |

| glycoside | − |

| flavonoids | +++ |

| proteins and amino acids | ++ |

| steroids and sterols | − |

| triterpenoids | − |

Table 2.

Quantitative phytochemical constituents of aqueous extract of C. fistula

| Phytochemical constituent | mg/100 g Dry weight (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| TPC | 278.33 ± 77.60 |

| TFC | 883.83 ± 38.86 |

It is worth mentioning here that, the C. fistula is extensively used throughout the world against a wide range of ailments. Being a valuable medicinal plant, its therapeutic uses and phytochemical investigations are noteworthy. Earlier studies on the phytochemistry of C. fistula leaves suggest the presence of phytoconstituents: namely, Rhein and its glycosides – sennosides A and B; hentriacontanoic, triacontanoic, nonacosanoic and heptacosanoic acids; anthraquinone, tannin, oxyanthraquinone, (‐) epiafzelechin, (‐) epiafzelechin‐3‐oglucoside, (‐) epicatechin, procyanidin B2, biflavonoids, triflavonoids, chrysophenol physcion [12, 28, 29, 30, 31] etc. Our study does not confirm the presence of glycosides, steroids and sterols which may be due to selective qualitative test performed or/and the conditions from where the samples collected. As per the hypothetical mechanism of biosynthesis of AgNPs, there could be involvement of adequate complex antioxidant enzyme networks [32]. In the present paper, the results of antioxidant potential of C. fistula offer a positive response toward hypothetical mechanism, in which antioxidant molecules from the leaf extract would involve in the biogenic synthesis of AgNPs. It is known that plants have a huge pile of phenolic and flavonoids which can have very high antioxidant capabilities. It is also believed that while plant is largely responsible for major antioxidant activity AgNPs do not contribute much [33].

3.3 Mechanism of biosynthesis of AgNPs

Several reports are available on existence of hypothetical mechanisms, where complex enzymes networks are believed to reduce the AgNO3 into AgNPs indicating that plant extracts are rich source of nitrate ions [34]. So far no mechanism is believed to be exact. Plants composed of complex network of antioxidant metabolites as well as enzymes that work together to prevent oxidative damage to cellular components [32]. Extracts from plants contain dissimilar biomolecules such as, alkaloids, ascorbic acid, flavonoids, polyphenols, polysaccharides, sterols, saponins, triterpenes and proteins/enzymes which could be used as reductant to react with Ag ions to help growing AgNPs in the solution [34, 35, 36, 37]. It was reported that the presence of terpenoids in neem are responsible for stabilising the NPs and reducing sugars thereby facilitating the reaction with the metal ions [38]. Moreover, the proteins having amine groups from the extract of Capsicum annuum showed a reducing feature in the formation of AgNPs in solutions [26]. In the present paper, the leaf extract of C. fistula encompasses the existence of alkaloids, proteins, tannins, phenolic compounds and flavonoids. Additionally, the aqueous extracts of plants exhibit the potential antioxidant properties. After conducting FTIR study, we observed three different bands located at ∼1637, ∼1552 and ∼1417 cm−1 and assigned to the respective stretching vibrations of C=O, C–N and O–H functional groups. The C=O and C–N stretching bands are generally found in the proteins involved in the reduction of the metal ions. Apparently, the presence of proteins could be responsible for the bioreduction of metal ions, yielding nano‐dimensional particles. Similar results were also obtained by another group during their investigation on biosynthesis of AgNPs using Cassia fistula flower extract [39].

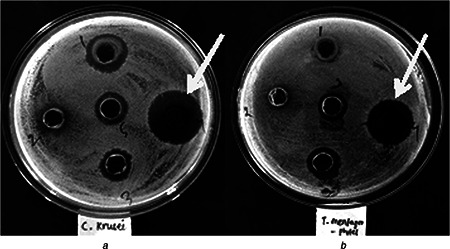

3.4 Antimicrobial activity of AgNPs

Preliminary screening of the antimicrobial activity was evaluated by agar‐cup methods against four pathogenic bacteria and four pathogenic fungi enlisted in Tables 3 and 4. In agar‐cup method, zone of inhibition was seen to be maximum against Gram positive bacteria B. subtilis and S. aureus, but no zone was evident against Gram‐negative bacteria (E. coli, P. aeruginosa). Similarly zone of inhibition was recorded against C. kruseii and T. mentagrophytes (Fig. 6), whereas no zone of inhibition could be found against C. albicans and C. viswanathii.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activity by agar‐cup method

| Name of the test strain | Mean zone of inhibition ± SD (in millimetres) |

|---|---|

| B. subtilis | 16.6 ± 1.4 |

| S. aureus | 18.6 ± 1.1 |

| E. coli | – |

| P. aeruginosa | – |

| C. albicans | – |

| C. kruseii | 23.3 ± 1.1 |

| C. viswanathii | – |

| T. mentagrophytes | 21.6 ± 1.1 |

Table 4.

Antimicrobial activity in broth dilution method

| Name of the test strain | Growth of inhibition (%) as compared with AgNPs (OD at 590 nm) |

|---|---|

| B. subtilis | 99.2 |

| S. aureus | 95.4 |

| E. coli | 18.4 |

| P. aeruginosa | – |

| C. albicans | 26 |

| C. kruseii | 99.47 |

| C. viswanathii | 64.4 |

| T. mentagrophytes | 98.24 |

Fig. 6.

Antifungal activity of AgNPs synthesised by C. fistula against

a C. kruseii

b T. mentagrophytes

It is important to note that strains such as B. subtilis, S. aureus, C. kruseii and T. mentagrophytes were found to get inhibited >95%. However, the Gram‐negatives, E. coli and P. aeruginosa were susceptible to AgNPs as evident from its present growth >80%. Interestingly, C. viswanathii was inhibited up to 65% in broth dilution method, whereas this strain did not display any zone of inhibition in the agar‐cup assay. It may be due to the limitation of agar‐cup method w.r.t. the inoculum size, incubation temperature and most likely differential diffusion of AgNPs component in the aqueous, broth medium [40].

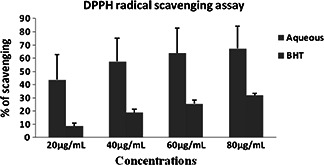

3.5 Antioxidant activity of C. fistula

Significant antioxidant activity was also noted by DPPH radical scavenging assay (Fig. 7) taking BHT as standard. Siddhuraju et al. [41] investigated the antioxidant properties of bark, pulp and flowers with both methanol and ethanol extracts. The antioxidant activity was found in descending order as we go from the bark, the leaves, the flowers and to the pulp, which were also well correlated with the total polyphenolic content of the extracts. Luximon‐Ramma et al. [31] have also studied the total phenolic, proanthocyanidin, flavonoid contents and the antioxidant activities of both fresh vegetative and reproductive parts. The antioxidant activities were strongly correlated with total phenols. However, their results showed that the antioxidant activities of the reproductive parts were higher than those of the vegetative organs, with the pods having highest total phenolic and flavonoid contents. Similar findings were also ascertained in the current study.

Fig. 7.

DPPH radical scavenging assay by aqueous extract of C. fistula

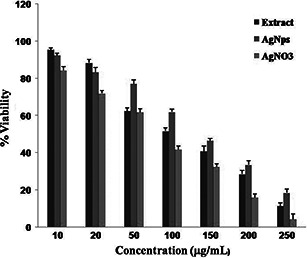

3.6 Cytotoxicity study of biogenically derived AgNPs

Owing to depletion of stratospheric ozone layer, the incidence of skin cancer is now on the rise, particularly in the Indian scenario. In this cytotoxicity study, epidermal carcinoma cell lines (A‐431) were taken for assessing anticancer activity of AgNPs. The A‐431 cells were seeded with various concentrations of leaf extract, AgNPs and aq. AgNO3 followed by evaluation of percentage cell viability using the MTT dye (Fig. 8). Earlier it was predicted that the Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Hydrogen (NADPH)‐dependent cellular oxidoreductase enzyme in the mitochondria has the ability to reduce the MTT to insoluble formazan [42]. In fact, the rate of cellular metabolism is directly proportional to the formation of formazan. The MTT assay is a convenient approach to study the effect of test samples on the cellular metabolism. After the treatment of cells with test sample, the IC50 values of 96.36 ± 1.01, 92.207 ± 1.24 and 84.246 ± 2.41 μg/ml are predicted for the leaf extract, AgNPs and AgNO3. The percentage cell viability clearly shows the dose‐dependent toxicity generated by the synthesised AgNPs on the cancer cell line (Fig. 8). Our results are also consistent to the works reported by Prabhu et al. [43] and Vasanth et al. [44]. Very recently, a similar study was conducted by Remya et al. [39] on cytotoxic effect of biosynthesised AgNPs using C. fistula flower extract on breast cancer and Vero cell line in a dose‐dependent manner. The authors have noted, after the incubation period, 90.5 and 89.7% cell death against MCF‐7 and Vero cell lines at 1000 µg/ml. The inhibitory concentration 50% (IC50) against MCF‐7 and Vero cell lines were observed at 7.19 and 66.34 µg/ml, respectively. As they used the same plants, though the parts and geographic location were different, we speculate that our synthesised AgNPs also have toxicity effect in normal cell line, but relatively less as compared with the effect on skin cancer cell line A‐431. However, further study in this direction is required to evaluate the extent of cytotoxicity in normal cell line as well as in in vivo model, which needs to be carried out.

Fig. 8.

Cytotoxic effect of AgNPs from the leaf extracts of C. fistula against A‐431 epidermal carcinoma cells

4 Conclusion

Silver NPs have been derived biogenically in a controlled environment of C. fistula and Ag+ rich media. The evaluation of toxic properties of synthesised AgNPs, using C. fistula is crucial when considering public health protection because exposure to Ag can result in undesirable effects on consumers. Few reports suggest that oral administration of C. fistula extract did not produce any significant toxicity relating to several biochemical analysis and histopathological examination in mice model. In the present paper, AgNPs were characterised using physical techniques: namely, UV–vis spectroscopy, DLS, FTIR, FE‐SEM and the potential antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities proposed to use for pharmaceutical formulations. The DLS data revealed that synthesised AgNPs can also be used in conjunction with the standard drugs to enhance their efficacy.

5 Acknowledgments

North Orissa University, M.P.C. Autonomous College, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology, Jadavpur University and Tezpur Central University are highly acknowledged for providing research facilities.

6 References

- 1. Arvizo R.R. Bhattacharyya S. Kudgus R.A. et al.: ‘Intrinsic therapeutic applications of noble metal nanoparticles: past, present and future’, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2012, 41, (7), pp. 2943 –2970 (doi: 10.1039/c2cs15355f) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dykman L. Khlebtsov N.: ‘Gold nanoparticles in biomedical applications: recent advances and perspectives’, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2012, 41, (6), pp. 2256 –2282 (doi: 10.1039/C1CS15166E) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Otsuka H. Nagasaki Y. Kataoka K.: ‘PEGylated nanoparticles for biological and pharmaceutical applications’, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., 2012, 64, pp. 246 –255 (doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nayak D. Ashe S. Rauta P.R. et al.: ‘Bark extract mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: evaluation of antimicrobial activity and antiproliferative response against osteosarcoma’, Mater. Sci. Eng. C, 2016, 58, pp. 44 –52 (doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.08.022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Doane T.L. Burda C.: ‘The unique role of nanoparticles in nanomedicine: imaging, drug delivery and therapy’, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2012, 41, (7), pp. 2885 –2911 (doi: 10.1039/c2cs15260f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dreaden E.C. El‐Sayed M.A.: ‘Detecting and destroying cancer cells in more than one way with noble metals and different confinement properties on the nanoscale’, Acc. Chem. Res., 2012, 45, (11), pp. 1854 –1865 (doi: 10.1021/ar2003122) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bedford E.E. Spadavecchia J. Pradier C.M. et al.: ‘Surface plasmon resonance biosensors incorporating gold nanoparticles’, Macromol. Biosci., 2012, 12, (6), pp. 724 –739 (doi: 10.1002/mabi.201100435) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. An K. Somorjai G.A.: ‘Size and shape control of metal nanoparticles for reaction selectivity in catalysis’, Chem. Cat. Chem., 2012, 4, (10), pp. 1512 –1524 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baruah B. Craighead C. Abolarin C.: ‘One‐phase synthesis of surface modified gold nanoparticles and generation of SERS substrate by seed growth method’, Langmuir, 2012, 28, (43), pp. 15168 –15176 (doi: 10.1021/la302861b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lu A.H. Salabas E.L. Schüth F.: ‘Magnetic nanoparticles: synthesis, protection, functionalization, and application’, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 2007, 46, (8), pp. 1222 –1244 (doi: 10.1002/anie.200602866) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mohanta Y.K. Behera S.K.: ‘Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles by Streptomyces sp.SS2’, Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng., 2014, 37, (11), pp. 2263 –2269 (doi: 10.1007/s00449-014-1205-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gupta R.K.: ‘Medicinal and aromatics plants’ (CBS Publisher and Distributor, India, 2010, 1st edn.) [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kirtikar K.R. Basu B.D. An I.C.G.: ‘Indian medicinal plants’, in Blatter E. Caius J.F. Mhaskar K.S. (Eds.): ‘International book distributors’ (Dehradun, India, 2006, 2nd edn.), vol. II [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alam M.M. Siddiqui M.B. Hussian W.: ‘Treatment of diabetes through herbal drugs in rural India’, Fitoterapia, 1990, 61, pp. 240 –242 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Asolkar L.V. Kakkar K.K. Chakre O.J.: ‘Second supplement to glossary of Indian medicinal plant with active principles’ (Publication and Information Directorate, CSIR, New Delhi, 1992), p. 414 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bhakta T. Mukherjee P.K. Mukherjee K. et al.: ‘Studies on in vivo wound healing activity of Cassia fistula Linn. Leaves (Leguminosae) in rats’, Nat. Product Sci., 1998, 4, pp. 84 –87 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bhakta T. Mukherjee P.K. Pal M. et al.: ‘Studies on antitussive activity of Cassia fistula (Leguminosae) leaf extract’, Pharm. Biol., 1998, 36, pp. 140 –143 (doi: 10.1076/phbi.36.2.140.4598) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thatoi H.N. Panda S.K. Rath S.K. et al.: ‘Antimicrobial activity and ethnomedicinal uses of some medicinal plants from Similipal biosphere reserve, Orissa’, Asian J. Plant Sci., 2008, 7, (3), pp. 260 –267 (doi: 10.3923/ajps.2008.260.267) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Panda S.K. Padhi L.P. Mohanty G.: ‘Antibacterial activities and phytochemical analysis of Cassia fistula (Linn.) leaf’, J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res., 2011, 2, (1), pp. 62 –67 (doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.79814) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Panda S.K. Brahma S. Dutta S.K.: ‘Selective anti‐candidal action of crude extracts of Cassia fistula L.: a preliminary study on Candida and Aspergillus species’, Malaysian J. Microbiol., 2010, 6, (1), pp. 62 –68 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Panda S.K. Patro N. Sahoo G. et al.: ‘Anti‐diarrheal activity of medicinal plants of Similipal biosphere reserve, Odisha, India’, Int. J. Med. Aromatic Plants, 2012, 1, (2), pp. 123 –134 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trease G.E. Evans W.C.: ‘Pharmocognosy’, 11th Edition, Braillier Tiridel and Macmillan Publishers, London, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Panda S.K. Dutta S.K.: ‘Antibacterial activity from bark extracts of Pterospermum acerifolium (L.) Willd’, Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res., 2011, 2, (3), pp. 584 –595 [Google Scholar]

- 24. McDonald S. Prenzler P.D. Antolovich M. et al.: ‘Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of olive extracts’, Food Chem., 2001, 73, pp. 73 –84 (doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00288-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chang C. Yang M. Wen H. et al.: ‘Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colorimetric methods’, J. Food Drug Anal., 2002, 10, pp. 178 –182 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Panda S.K.: ‘Ethnomedicinal uses and screening of plants for antibacterial activity from Similipal biosphere reserve, Odisha, India’, J. Ethnopharmacol., 2014, 151, pp. 158 –175 (doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.10.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li S. Shen Y. Xie A. et al.: ‘Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Capsicum annuum L. extract’, Green Chem., 2007, 9, (8), pp. 852 –858 (doi: 10.1039/b615357g) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Asseleih L.M.C. Hernandez O.H. Sanchez J.R.: ‘Seasonal variation in the content of sennosides in leaves and pods of two Cassia fistula populations’, Phytochemistry, 1990, 29, pp. 3095 –3099 (doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(90)80164-C) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chowdhury S.A. Mustafa Kamal A.K.M. Alam M.N. et al.: ‘Sennoside B rich active concentrate from Cassia fistula ‘, Bangladesh J. Sci. Res., 1996, 31, pp. 91 –97 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dutta A. De B.: ‘Seasonal variation in the content of sennosides and Rhein in leaves and pods of Cassia fistula ‘, Ind. J. Pharm. Sci., 1998, 60, pp. 388 –390 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luximon‐Ramma A. Bahorun T. Soobrattee M.A. et al.: ‘Antioxidant activities of phenolic, proanthocyanidins, and flavonoid components in extracts of Cassia fistula ‘, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2002, 50, pp. 5042 –5047 (doi: 10.1021/jf0201172) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Prasad R.: ‘Synthesis of silver nanoparticles in photosynthetic plants’, J. Nanoparticles, 2014, Article ID 963961, 8 pages [Google Scholar]

- 33. Abdel‐Aziz M.S. Shaheen M.S. El‐Nekeety A.A. et al.: ‘Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized using Chenopodium murale leaf extract’, J. Saudi Chem. Soc., 2014, 18, (4), pp. 356 –363 (doi: 10.1016/j.jscs.2013.09.011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sharma N.C. Sahi S.V. Nath S. et al.: ‘Synthesis of plant‐mediated gold nanoparticles and catalytic role of biomatrix‐embedded nanomaterials’, Environ. Sci. Technol., 2007, 41, (14), pp. 5137 –5142 (doi: 10.1021/es062929a) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mohanpuria P. Rana N.K. Yadav S.K.: ‘Biosynthesis of nanoparticles: technological concepts and future applications’, J. Nanoparticle Res., 2008, 10, (3), pp. 507 –517 (doi: 10.1007/s11051-007-9275-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chandran S.P. Chaudhary M. Pasricha R. et al.: ‘Synthesis of gold nanotriangles and silver nanoparticles using Aloe vera plant extract’, Biotechnol. Prog., 2006, 22, (2), pp. 577 –583 (doi: 10.1021/bp0501423) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saxena A. Tripathi R.M. Zafar F. et al.: ‘Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous solution of Ficus benghalensis leaf extract and characterization of their antibacterial activity’, Mater. Lett., 2012, 6, (1), pp. 91 –94 (doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2011.09.038) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shankar S.S. Rai A. Ahmad A. et al.: ‘Rapid synthesis of Au, Ag, and bimetallic Au core‐Ag shell nanoparticles using Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf broth’, J. Colloid Interface Sci., 2004, 275, (2), pp. 496 –502 (doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.03.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Remya R. Rajasree S.R.R. Aranganathan L.: ‘An investigation on cytotoxic effect of bioactive AgNPs synthesized using Cassia fistula flower extract on breast cancer cell MCF‐7’, Biotechnol. Rep., 2015, 8, pp. 110 –115 (doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2015.10.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Panda S.K. Rath C.C.: ‘Phytochemicals as natural antimicrobials: Prospects and challenges’, in Gupta V.K. (Ed.): ‘Bioactive phytochemicals: perspectives for modern medicine vol.‐ 1’ (Daya Publisher, New Delhi, 2012), pp. 329 –389 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Siddhuraju P. Mohan P.S. Becker K.: ‘Studies on the antioxidant activity of Indian laburnum (Cassia fistula L.): a preliminary assessment of crude extracts from stem bark, leaves, flowers and fruit pulp’, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2002, 79, pp. 61 –67 (doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00179-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Berridge M.V. Herst P.M. Tan A.S.: ‘Tetrazolium dyes as tools in cell biology: new insights into their cellular reduction’, Biotechnol. Annu. Rev., 2005, 11, pp. 127 –152 (doi: 10.1016/S1387-2656(05)11004-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Prabhu D. Arulvasu C. Babu G. et al.: ‘Biologically synthesized green silver nanoparticles from leaf extract of Vitex negundo L. induce growth‐inhibitory effect on human colon cancer cell line HCT15’, Process Biochem., 2013, 48, (2), pp. 317 –324 (doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.12.013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vasanth K. Ilango K. MohanKumar R. et al.: ‘Anticancer activity of Moringa oleifera mediated silver nanoparticles on human cervical carcinoma cells by apoptosis induction’, Colloids Surfaces B, Biointerfaces, 2014, 117, pp. 354 –359 (doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.02.052) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]