Abstract

A procedure that uses an original molecular marker (IS200-PCR) and that is based on the amplification of DNA with outward-facing primers complementary to each end of IS200 has been evaluated with a collection of 85 Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates. These strains were isolated from a group of 10 cows at different stages: during transportation between the farm and the slaughterhouse, on the slaughter line, from the environment, and from the final product (ground beef). The 85 isolates were characterized by their antibiotic resistance patterns and were compared by IS200-PCR and by use of four other genotypic markers. Those markers included restriction profiles for 16S and 23S rRNA (ribotypes) and amplification profiles obtained by different approaches: random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis, enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR, and PCR ribotyping. The results of the IS200-PCR were in accordance with those of other molecular typing methods for this collection of isolates. Five different genotypes were found, which made it possible to refine the hypotheses on transmission obtained from phenotypic results. The genotyping results indicated the massive contamination of the whole group of animals and of the environment by one clonal strain originally recovered from one cow that excreted the strain. On the other hand, a few animals and their environment appeared to be simultaneously contaminated with genetically different strains.

Salmonella spp. are some of the most serious contaminants of food products and are the main bacterial agent responsible for food-borne outbreaks of human gastroenteritis in France (16). Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium is of particular clinical importance and is also the serotype most frequently isolated from bovine pathology material and products (5). Bovine products are often suspected sources of human gastroenteritis when serotype Typhimurium strains are isolated. A great deal of research has been done on the contamination of meat products by Salmonella spp. However, the relationship between the contamination of the animal before slaughter and the quality of the final product is poorly understood. The development of molecular markers to trace clonal Salmonella strains in order to relate outbreaks with bovine sources is therefore important. It will also help to trace precisely the diffusion of strains and to identify the origins of herd contamination and therefore the origins of the contamination of bovine products.

Numerous phenotypic and genotypic methods have thus been developed and used in order to subtype Salmonella serotypes, particularly serotype Typhimurium isolates. Phage typing is of great usefulness for the description of important pandemic clones, for instance, S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 (2, 36). Plasmid profiling has proved useful in various epidemiological studies (24, 41). Chromosomal characterization by ribotyping, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis for IS200, or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis has been evaluated for the more precise subtyping of Salmonella strains (3, 8, 14, 24). The use of PCR with different complementary approaches has been considered recently for Salmonella isolates, either a random approach named random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis (or arbitrarily primed PCR) (7, 13, 18, 19, 25) or methods based on repetitive elements present in several copies on the chromosome, for example, PCR with enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC) sequences (ERIC-PCR) (7, 19, 25) and PCR ribotyping (21, 22, 27).

A procedure for the amplification of DNA fragments with outward-facing primers complementary to each end of IS200 (IS200-PCR) has been designed and evaluated in our laboratory. We hypothesized that the number of copies of IS200 as well as the IS200 insertion positions would be strain specific and that these copies would be spaced close enough to allow amplification of polymorphic inter-IS200 element sequences. Thus, these variations would allow different sizes and numbers of DNA fragments to be amplified, yielding unique banding patterns for different Salmonella strains.

IS200 is a short insertion sequence (IS) of about 708 bp that was first described in Salmonella. It is related to other ISs found in several other genera such as Yersinia (IS1541) (30) and Clostridium (IS1469) (6). IS200 has been extensively used for the typing of Salmonella isolates of numerous serotypes by RFLP analysis (8, 14, 24), an approach that could be called IS200 typing (9). Similarly, molecular typing by RFLP analysis for IS1541 of isolates of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis has been described (29).

The aims of the present investigation were first to evaluate IS200-PCR for the tracing of bovine Salmonella isolates and second to investigate more precisely the relationship between contamination of cows and the resulting contamination of the carcasses and ground meat produced from these animals. Eighty-five strains of S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolated from animals and from their environment were characterized by phenotypic methods as well as by chromosomal fingerprinting. IS200-PCR was compared with PCR with other molecular markers. Ribotyping was considered the reference method in our study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The reference strains used in our experiments are presented in Table 1. F98 was kindly provided by P. A. Barrow (Houghton Laboratory, Institute for Animal Health, Agriculture and Food Research Council, Huntingdon, United Kingdom), and strains BN8301, BN8501, BN91A1, and BN91C1 were kindly provided by E. Chaslus-Dancla (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Tours, France). Strains IP5210, IP5858, and IP6062 are serotype Typhimurium isolates from the reference collection of the Institut Pasteur (Paris, France).

TABLE 1.

Source and PCR types of the S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium strains studied

| Strain | Source | IS200-PCR type | RAPD profilea | ERIC-PCR type | PCR ribotype | PCR type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference strains | ||||||

| F98 | Chicken, pathology | A | 11111 | I | a | A |

| BN8301 | Pigeon, septicemia, France | A | 11221 | I | b | B |

| BN8501 | Duck, carriage, France | A | 11331 | I | b | C |

| BN91A1 | Turkey, litter, France | A | 21332 | I | c | D |

| BN91C1 | Duck, carriage, France | A | 11431 | I | c | E |

| IP5210 | A | 12521 | I | b | F | |

| IP5858 | B | 12531 | I | d | G | |

| IP6062 | B | 22531 | I | d | H | |

| Bovine study strains | ||||||

| LV1, LV2 | Lorry after transport | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV3 | Feces before transport (cow no. 3) | C | 34643 | III | e | K |

| LV4 | Feces before transport (cow no. 5) | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV5 | Hair before transport (cow no. 5) | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV6 | Bars of cubicle before animal waiting period | B | 17511 | II | a | L |

| LV7 | Bars of cubicle before animal waiting period | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV8 to LV11 | Feces after transport | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV12 to LV20 | Hair after transport | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV21 to LV25, LV27 to LV30 | Floor of cubicle after animal waiting period | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV26 | Floor of cubicle after animal waiting period | D | 45754 | IV | f | M |

| LV31 to LV32, LV34 to LV39 | Bars of cubicle after animal waiting period | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV33 | Bars of cubicle after animal waiting period | D | 56865 | II | g | N |

| LV40 to LV43 | Feces after staying in cubicle | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV44 to LV52 | Hair after staying in cubicle | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV53 | Loading corridor before animal passage | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV54 | Loading corridor after animal passage | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV55 | Stunning area after animal passage | D | 45754 | IV | f | M |

| LV56 to LV64 | Hair before skinning | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV65 | Carcass after skinning | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV66 to LV68 | Hepatic lymph nodes | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV69 to LV70 | Retropharyngeal lymph nodes | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV71 | Carcass after chilling | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV72 to LV81 | Ears | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

| LV82 to LV85 | Ground meat | B | 13511 | II | d | J |

Combined results with primers OPF08, OPF13, OPG04, OPG10, and OPH04.

We also studied 85 serotype Typhimurium strains isolated from bovine sources in 1995 in France in an experiment conducted to evaluate the influence of animal contamination with Salmonella on the contamination of the final product (35). In this experiment, a group of 10 cows from an eastern region of France was studied during transportation between the farm and the slaughterhouse and on the slaughter line. Two cows which had been clinically affected by salmonellosis and which had been shown to excrete serotype Typhimurium 1 or 2 weeks before the experiment were included in the experiment. Isolates were obtained from the animals, from their environment, and from the final product, ground meat. An effort was made to sample the 10 animals studied equally. Animal and environmental sampling procedures as well as bacteriological examination protocols and the serotyping method have been presented in a previous paper (35). The characteristics and the origins of the strains are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Table 2 underlines, when possible, which animal excreted or was contaminated with any isolate.

TABLE 2.

Origins of the strains isolated from animals or the environment

| Origin ofisolation | Strain no. |

|---|---|

| Cow no. 1 | LV12, LV21, LV31, LV44, LV56, LV72 |

| Cow no. 2 | LV13, LV22, LV32, LV40, LV45, LV57, LV73 |

| Cow no. 3 | LV3a, LV8, LV14, LV23, LV33, LV41, LV46, LV58, LV65, LV66, LV69, LV71, LV74 |

| Cow no. 4 | LV9, LV15, LV24, LV34, LV42, LV47, LV59, LV75 |

| Cow no. 5b | LV4, LV5, LV10, LV25, LV35, LV48, LV60, LV67, LV70, LV76 |

| Cow no. 6 | LV11, LV16, LV26, LV36, LV49, LV61, LV77 |

| Cow no. 7 | LV17, LV27, LV50, LV62, LV68, LV78 |

| Cow no. 8 | LV18, LV28, LV37, LV43, LV51, LV63, LV79 |

| Cow no. 9 | LV19, LV29, LV38, LV52, LV64, LV80 |

| Cow no. 10 | LV20, LV30, LV39, LV81 |

| Environment | LV1, LV2, LV6, LV7, LV53, LV54, LV55 |

| Ground beef | LV82 to LV85 |

Isolates designated in boldface belonged to minor clones.

Carrier animal; excretion was confirmed before the experiment.

Resistance to antibiotics.

The strains were screened for their resistance to 16 antibiotics (Sanofi-Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) by the standardized disk diffusion technique (4): amoxicillin (25 μg), florfenicol (30 μg), apramycin (10 IU), cefalexin (30 μg), ceftiofur (30 μg), cefquinome (30 μg), colistin (50 μg), enrofloxacin (5 μg), flumequine (30 μg), gentamicin (10 IU), neomycin (30 IU), oxolinic acid (10 μg), spectinomycin (100 μg), streptomycin (10 IU), tetracycline (30 IU), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 μg).

Restriction profiles for rDNA.

To obtain restriction profiles, total DNA was extracted from the bacteria after an 18-h culture at 37°C either by a modified version of the salting-out technique described by Miller et al. (26) or as described by Wilson (40). Two to 5 μg of DNA was digested with 10 U of a restriction endonuclease (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). Four different endonucleases were chosen for ribotyping after preliminary experiments: HindIII, PstI, PvuII, and SmaI. Genomic restriction digests were electrophoresed on 0.8% horizontal agarose gels and were visualized with shortwave UV light. The Raoul marker (Appligène, Illkirch, France) was used as a molecular weight standard. Afterward, the digestion products were vacuum blotted (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) onto Hybond-N nylon membranes (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Blots of digested electrophoresed DNA were hybridized with the p14b1 plasmid containing a Bacillus subtilis ribosomal DNA (rDNA) insert (17). Probes were digoxigenin labeled by using the DIG high prime labeling and detection starter kit I (Boehringer Mannheim). Hybridization was conducted at 65°C in a hybridization oven (Techne, Cambridge, United Kingdom). The filters were stringently washed. Homologous bands were visualized after revelation with nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (Boehringer Mannheim).

PCR methods. (i) DNA extraction.

For amplification profiles, DNA was extracted by a boiling method as follows: 1.5 ml of an overnight broth culture was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended twice in 100 μl of sterile ultrapure water and was then boiled for 10 min. After a final centrifugation at the speed mentioned above, the supernatant was gently recovered.

(ii) Primer design.

For IS200-PCR, we used the PileUp program of the GCG package. A multiple alignment was performed with a set of Salmonella IS200 sequences found in the GenBank database (accession numbers X56834, Y09564, U44749, Z54217, Y09991, Y09990, Y09989, X91136, L25848, M57304, M57306, X03452, and X03451). Primers corresponding to the most conserved regions were designed to be outward facing and complementary to each end of the consensus sequence of IS200. Primers and primer sequences were as follows: IS1R, 5′-AGGCGCATCTGAAAAACCTCGG-3′ (nucleotides 667 to 688), and IS2, 5′-CGGAACCCCCAGCCTAGCTGGG-3′ (nucleotides 35 to 14).

For RAPD analysis, preliminary assays were conducted with 60 decanucleotides from F, G, and H kits (Operon Technologies, Alameda, Calif.) with the eight reference strains. Five primers were chosen among the 60 decanucleotides for subsequent studies because of the clear and distinct banding patterns obtained: OPF08 (5′-GGGATATCGG-3′), OPF13 (5′-GGCTGCAGAA-3′), OPG04 (5′-AGCGTGTCTG-3′), OPG10 (5′-AGGGCCGTCT-3′), and OPH04 (5′-GGAAGTCGCC-3′). The primers used for ERIC-PCR are based on ERIC sequences and have been described by Versalovic et al. (38). When performing PCR-ribotyping, we used the primers described by Kostman et al. (20) in order to amplify 16S-23S intergenic sequences.

(iii) PCR conditions.

PCR conditions were as follows. Each set of reactions included a control tube without template DNA. For each method used, the amplification conditions (deoxynucleoside triphosphate concentration, annealing temperature, duration of extension, DNA concentration) have been varied in order to obtain reproducible banding patterns. For all methods used in this study, we chose to add 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Bioprobe Systems, Montreuil, France) in a 25-μl reaction volume and to work with a final deoxynucleotide triphosphate concentration of 0.2 mM (Bioprobe Systems) in the recommended reaction buffer containing 20 mM Tris HCl, 16 mM (NH4)2SO4, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.2 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml. In all cases, 10 ng of genomic DNA was added to each tube. All amplifications were performed in a PHC-3 thermal cycler (Techne Instruments, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

For the IS200-PCR, 20 pmol of each outward-facing primer, IS1R and IS2, was added to the 25-μl reaction volume. The optimal amplification cycles for IS200-PCR were as follows: 94°C for 3 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 4 min for the first cycle and then 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 4 min for the other 45 cycles. The final cycle included 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1 min of annealing at 55°C, and a final extension at 72°C for 20 min.

For the RAPD technique, 15 pmol of one primer was added to the reaction volume. Amplification cycles for RAPD analysis were as follows: 94°C for 3 min, 35°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min 30 s for the first cycle and 94°C for 40 s, 35°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min 30 s for the other 35 cycles. The final extension at 72°C lasted 10 min.

For performance of the ERIC-PCR, 12.5 pmol each of ERIC1R and ERIC2 primers was added to the reaction volume. Amplifications cycles for ERIC-PCR were as follows: 94°C for 3 min, 51°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 4 min for the first cycle and then 94°C for 1 min, 51°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 4 min for the other 35 cycles. The final cycle included 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1 min of annealing at 51°C, and a final extension at 72°C for 20 min.

For PCR ribotyping, 25 pmol each of primers SP1 and SP2 was added in a 25-μl reaction volume. Amplification cycles for PCR-ribotyping were as follows: 94°C for 3 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min for the first cycle and then 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min for the other 29 cycles. The final cycle included 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1 min of hybridization at 55°C, and a final extension at 72°C for 4 min.

Amplification products were separated by horizontal electrophoresis through 2% agarose gels. Marker VIII (Boehringer Mannheim) was used as a molecular weight standard.

Reproducibility.

The reproducibilities of the fingerprints were assessed with successive runs with the same samples and also with different DNA samples extracted from a single isolate.

Data analysis.

The rDNA patterns and PCR types were analyzed as described previously (24, 25), except that agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis was performed by using the commercial software program SAS (1996; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.).

RESULTS

Resistance to antibiotics.

All 85 strains isolated in the field study harbored the same antibiotype, being resistant only to amoxicillin and tetracycline. They were sensitive to all the other 14 antibiotics tested.

Comparison of methods of S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium typing.

A number of different fingerprints were obtained by each method used (Table 1).

Reference strains of different geographical and animal origins could be separated by three of the four PCR methods evaluated. Two patterns were obtained by IS200-PCR, with strains IP5858 and IP6062 being differentiated from the others. RAPD analysis proved to be the most discriminative and allowed assignment of a distinct pattern to each strain, after combination of the results obtained with the five primers retained after preliminary assays. Primer OPG04 was the most discriminative, allowing the observation of five distinct profiles, while OPG10 provided three patterns. Only two patterns were obtained with each primer OPF08, OPF13, or OPH04, but a different pattern was discriminated by each primer. Four different PCR ribotypes were identified. ERIC-PCR provided only one profile for the eight reference strains used in this study.

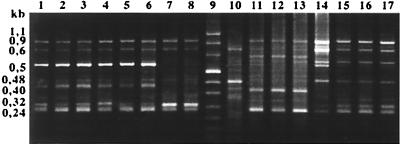

In our study with field isolates, IS200 PCR resulted in three different fingerprints. They exhibited six to eight bands whose molecular sizes were between 240 bp and 1 kb (see Fig. 1, which presents the fingerprints observed among the 85 isolates studied by IS200-PCR). LV3 had a unique pattern (profile C), while LV26, LV33, and LV55 shared profile D. All other isolates studied exhibited profile B.

FIG. 1.

IS200-PCR amplification profiles of S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates. Lanes 1 to 8, reference strains F98, BN8301, BN8501, BN91A1, BN91C1, IP5210, IP5858, and IP6062, respectively; lane 9, molecular size Marker VIII (Boehringer Mannheim); lanes 10 to 17, isolates LV3, LV26, LV33, LV55, LV30, LV40, LV50, and LV60, respectively.

The combination of the results obtained with the five primers resulted in five RAPD types. With the chosen primers, 5 to 14 bands with molecular sizes between 180 and 1,100 bp were detected. Interestingly, the same discrimination was achieved with four primers (OPF08, OPG04, OPG10, and OPH04), leading to the separation of isolates LV3, LV26, LV33, and LV55 from the other bovine isolates. Primer OPF13 was the most discriminative, allowing us to distinguish between isolate LV6 and the other isolates. LV26 and LV55 shared the same pattern. Isolates LV3, LV33, and LV6 had unique profiles.

Three different ERIC-PCR profiles were observed among the 85 isolates studied. They exhibited 7 to 12 bands whose molecular sizes were between 160 and 1,220 bp. Eighty-two isolates shared profile II, isolate LV3 presented a unique pattern (profile III), and isolates LV26 and LV55 shared profile IV.

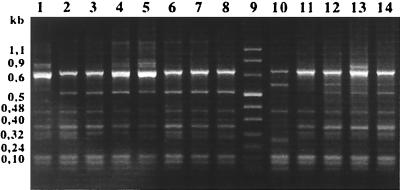

Four PCR ribotypes were obtained among the 85 isolates (Fig. 2). The major pattern, pattern d, was observed for 81 isolates, while pattern e was observed for LV3 and pattern g was observed for LV33. LV26 and LV55 shared pattern f.

FIG. 2.

PCR-ribotypes of the Salmonella strains studied. Lanes 1 to 8, reference strains F98, BN8301, BN8501, BN91A1, BN91C1, IP5210, IP5858, and IP6062, respectively; lane M, molecular weight Marker VIII (Boehringer Mannheim); lanes 10 to 14, isolates LV3, LV6, LV26, LV33, and LV55, respectively.

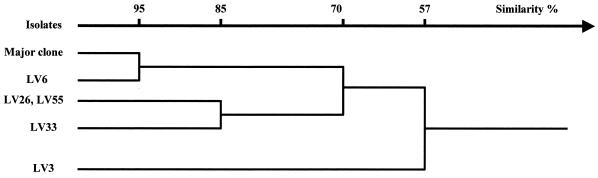

The combination of the results obtained by the four rapid methods that used PCR led to the definition of five PCR types among the 85 bovine isolates studied, i.e., the grouping of isolates that shared the same amplification profiles. The five PCR types, types J to N, are presented in Table 1. Only five isolates could be discriminated, with two of them (LV26 and LV55) being of the same PCR type. The three other isolates each had unique PCR types. The analysis of the results allowed the construction of a dendrogram (Fig. 3), with the constitution of two groups and with an unique isolate (LV3) being clearly separated from the other isolates studied.

FIG. 3.

Dendrogram showing the results of the ascending hierarchical classification based on PCR types of the 85 bovine S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates presented in Table 1.

For ribotyping, five enzymes have been chosen after preliminary assays: BglII, HindIII, PstI, PvuII, and SmaI. Four distinct rDNA profiles were obtained among the five reference strains either with BglII or with PvuII, but with different grouping, for each endonuclease (Table 3). With SmaI, three different patterns were observed, while PstI ribotyping produced a unique profile for BN91C1 (profile Ps2). All eight strains gave identical fingerprints when HindIII was used. The combined rDNA patterns obtained with the five endonucleases allowed the definition of a unique ribotype for each of the five reference strains tested.

TABLE 3.

Ribotypes of the S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates

| Strain | rDNA pattern

|

Ribotype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BglII | HindIII | PstI | PvuII | SmaI | ||

| F98 | B1 | H1 | Ps1 | Pv1 | S1 | R1 |

| BN8301 | B2 | H1 | Ps1 | Pv2 | S2 | R2 |

| BN91C1 | B3 | H1 | Ps2 | Pv3 | S3 | R3 |

| IP5210 | B2 | H1 | Ps1 | Pv4 | S2 | R4 |

| IP6062 | B4 | H1 | Ps1 | Pv1 | S1 | R5 |

| LV3 | B5 | H2 | Ps1 | Pv5 | S1 | R6 |

| LV6 | B6 | H1 | Ps3 | Pv1 | S5 | R7 |

| LV26 | B6 | H1 | Ps3 | Pv1 | S6 | R8 |

| LV33 | B6 | H1 | Ps3 | Pv1 | S6 | R8 |

| LV55 | B6 | H1 | Ps3 | Pv1 | S6 | R8 |

| LV1, LV2, LV4, LV5, LV7 to LV25, LV27 to LV32, LV34 to LV54, LV56 to LV85 | B6 | H1 | Ps3 | Pv6 | S6 | R9 |

Among the 85 bovine isolates, two patterns were observed with BglII, HindIII, and PstI, which all separated LV3 from all other isolates (Table 3). SmaI ribotyping gave three profiles, with the separation of LV3 and LV6. PvuII ribotyping also led to the observation of three patterns, but the discrimination achieved was different: LV3 had pattern Pv5, while LV6, LV26, LV33, and LV55 shared pattern Pv1. The combination of these results led to the determination of four ribotypes. Again, five isolates that had already been discriminated by PCR typing methods were separated: LV3, LV6, LV26, LV33, and LV55.

DISCUSSION

The use of PCR-based methods for the typing of bacterial isolates is promising because they are simple to carry out and provide a rapid answer which is easy to interpret. They are generally considered to be able to provide a high degree of discrimination at a low cost (31). By contrast, ribotyping, which is generally considered a reference technique, remains a time-consuming and expensive method.

PCR amplification of segments located between distinct repetitive DNA elements allows the development of rapid methods useful for the subtyping of bacteria. For instance, ERIC-PCR relies on PCR amplification of fragments located between ERIC sequences with outward-facing primers complementary to each end of the ERIC sequences (38). A similar approach named “inter-IS256 spacer analysis” has been developed for the typing of Staphylococcus isolates, which led to results similar to those obtained by other molecular typing methods (11). Several related methods have been evaluated for the subtyping of Mycobacterium isolates. Ross and Dwyer (37) used the terminal regions of IS6110 to divergently amplify DNA segments between copies of this insertion sequence. Similarly, Mycobacterium avium isolates have been typed by a rapid technique based on PCR amplification of genomic sequences located between two related insertion sequences: IS1245 and IS1311 (33). This technique has been evaluated by Yoder et al. (43) for the comparison of levels of relatedness of M. avium isolates found in patients and foods. Those investigators concluded that this PCR typing method was a rapid, inexpensive method for the typing of M. avium, possibly replacing pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. While the latter rapid method used two primers, Otal et al. (32) proposed the use of only one primer for the amplification of segments located between IS6110 copies and compared this technique, called “IS6110-PCR,” to “IS6110-inverse-PCR,” in which amplification followed digestion and ligation. They compared IS6110-inverse-PCR and IS6110-PCR to IS6110-RFLP analysis and found concordant results: they recommended IS6110-PCR as a screening method for the quick differentiation between M. tuberculosis strains. Plikaytis et al. (34) developed a method called “ampliprinting,” based on PCR amplification of spacers between IS6110 elements and copies of a major polymorphic tandem repeat sequence (related to repetitive extragenic palindromic sequences of Escherichia coli) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The double-repetitive-element PCR based on amplification of spaces between IS6110 copies and the polymorphic GC-rich repetitive sequence, as well as RFLP methods, has been shown to be able to differentiate M. tuberculosis isolates (15).

A method for the amplification of DNA fragments with outward-facing primers complementary to each end of IS200 (IS200-PCR) has been designed and evaluated in our laboratory. In our field study, the results of IS200-PCR corroborated the results obtained with the other markers assayed and thus reinforced the proposed epidemiological hypotheses. It can be noted that in our work the number of bands amplified by IS200-PCR (six to eight) is compatible with the number of IS200 copies generally found on the chromosomes of S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates (24). IS200-PCR appears to be a novel and rapid method which discriminates among bovine field isolates in accordance with the discriminatory abilities of other markers. It must be underlined that the results obtained by PCR typing methods were consistent with those of ribotyping, with the latter method being considered the reference method. IS200-PCR provided a rapid answer, at a low cost, and patterns that were easy to read, without a preliminary search for oligonucleotides, in contrast to RAPD assays (22, 25). Thus, we suggest that IS200-PCR could provide a rapid and simple means of typing Salmonella isolates for epidemiological studies.

Yet, IS200-PCR will be applicable only to epidemiological studies with Salmonella strains which harbor copies of the IS200 element on their chromosomes. For instance, it will not be applicable to S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Hadar isolates because of the lack of such elements in isolates of this serotype (39). However, a comparative study was carried out with five S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Dublin isolates from our collection. Three specific fingerprints were generated by IS200-PCR, which allowed differentiation among serotype Dublin isolates. The fingerprints of serotype Dublin and Typhimurium strains were easily distinguished, although they shared three bands of similar molecular weights (data not shown).

The results of typing of 85 bovine S. enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium isolates led us to propose epidemiological hypotheses concerning the contamination of animals during transport and before slaughter as well as the contamination of the final product.

Initially, phenotypic characterization was achieved by serotyping and determination of resistance to antibiotics. Only one antibiogram could be detected, with resistance to amoxicillin and tetracycline. Resistance to these antibiotics is widely encountered in bovine serotype Typhimurium isolates. No clear conclusion could be drawn on the basis of these homogenous phenotypic characteristics.

The molecular characterization refined the results and discriminated five isolates according to their PCR types. This grouping was thereafter confirmed by classical ribotyping (considered a reference method). On the basis of these results, it appears that the major clone had initially been recovered on the farm and was harbored by animal 5. Thereafter, 79 other isolates were isolated from the 10 animals and from the environment. This led to the hypothesis of contamination, probably at a high level, of the whole group with a single major clone.

Moreover, four minor clones were recovered at different steps and/or were excreted by different animals (Tables 1 and 2). Knowledge of their precise sources with the help of the analysis of the dendrogram (which showed clonal ties between isolates) allows us to formulate some hypotheses. Isolate LV3 was isolated in the feces of animal 3. It was very different from the major clone (the genetic distance between them is large). This particular clone has been isolated only once. It is possible that it was excreted at a low concentration, preventing widespread diffusion. The LV6 strain is genetically closely related to the major clone, although it was isolated in the environment of the abattoir before the arrival of the animals. It may have been brought to the abattoir by animals of the same geographical origin. LV26 was isolated on the ground of the cubicle with animal 6, LV33 was isolated from the environment of animal 3, and LV55 was isolated in the stunning area after animal passage. LV26, LV33, and LV55 isolates share 85% similarity. As they were recovered in the environment of the abattoir, all three isolates could be resident strains of the abattoir.

Finally, numerous strains have been isolated during the experiment: this suggests that the excreting animal contaminated its environment as well as the other animals to a large extent. It may be hypothesized that this animal excreted a large amount of salmonellae: this could be related to transport-related stress. The transportation period is in fact considered to be important for the amplification of Salmonella excretion and dissemination (10, 42). As the same clone was isolated starting from the farm up to the final meat product, the risk of meat contamination is underlined, and therefore the risk of human food-borne disease not only from a Salmonella carrier animal but also from animals that were transported with this carrier is increased. This potential excretion of Salmonella by cattle must be considered, for instance, in order to reorganize slaughtering to limit the risk of contamination. It could be suggested that potential Salmonella excretors be slaughtered at the end of the day or, better, be removed from the production of ground meat.

A difficulty of epidemiological typing is the choice of a “gold standard” that may take into account the evolution of the strains. For instance, although RFLP analysis with IS6110 has been shown to be stable in vitro and in vivo, Alito et al. (1) recently described nine M. tuberculosis isolates from related subjects with slightly different RFLP patterns. Thus, they concluded that the IS6110 RFLP in particular multidrug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains may evolve too fast for reliable use when studying outbreaks.

It could be interesting to locate on the genome the regions in which the epidemiological markers used have detectable differences. In fact, genetic rearrangements that are responsible for the evolution of chromosomal fingerprints can occur. Such rearrangements between rrn operons that result in modifications of the ribotype have been demonstrated in Salmonella serovar Typhi (28) as well as in other serotypes including Typhimurium (23). In fact, chromosomal rearrangements have also been shown to occur during the emergence of an outbreak, affecting molecular typing of Salmonella serovar Typhi strains (12). A better understanding of the consequences of such modifications must be achieved in order to evaluate more objectively and more precisely the genetic relationships between isolates for epidemiological purposes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Ministry of Agriculture with the financial support of ARCADIE SA funded the work.

We thank D. Marc, whose help in conceiving primers IS1 and IS2R was accurate, and R. Aufrere, who kindly provided plasmid p14b1. O. Cerf and P. Pardon are gratefully acknowledged for advice. M. Cance (APAVE) and A. Laval (ENV Nantes) are gratefully acknowledged for collaboration. We also thank Andrew Ponter (ENV Alfort) and Mark Tepfer (INRA Versailles) for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alito A, Morcillo N, Scipioni S, Dolmann A, Romano M I, Cataldi A, van Soolingen D. The IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism in particular multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains may evolve too fast for reliable use in outbreak investigation. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:788–791. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.788-791.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arcangioli M-A, Leroy-Sétrin S, Martel J-L, Chaslus-Dancla E. A new chloramphenicol and florfenicol resistance gene flanked by two integron structures in Salmonella typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:327–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggesen D L, Aarestrup F M. Characterisation of recently emerged multiple antibiotic-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium DT104 and other multiresistant phage types from Danish pig herds. Vet Rec. 1998;143:95–97. doi: 10.1136/vr.143.4.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer A, Kirby W M M, Cherris J C, Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brisabois A, Fremy S, Moury F, Oudart C, Piquet C, Pires Gomes C. L'inventaire des Salmonellas 1994–1995. Maisons-Alfort, France: CNEVA; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brynestad S, Granum P E. Evidence that Tn5565, which includes the enterotoxin gene in Clostridium perfringens, can have a circular form which may be a transposition intermediate. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;170:281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burr M D, Josephson K L, Pepper I L. An evaluation of ERIC PCR and AP PCR fingerprinting for discriminating Salmonella serotypes. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1998;27:24–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1998.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casin I, Breuil J, Brisabois A, Moury F, Grimont F, Collatz E. Multidrug-resistant human and animal Salmonella typhimurium isolates in France belong predominantly to a DT104 clone with the chromosome- and integron-encoded beta-lactamase PSE-1. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1173–1182. doi: 10.1086/314733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaslus-Dancla E, Millemann Y. Rational approach to the choice of molecular markers applicable to the tracing of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. In: Saeed A M, Gast R K, Potter M E, Wall P G, editors. Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in humans and animals. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1999. pp. 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corrier D E, Purdy C W, Deloach J R. Effects of marketing stress on fecal excretion of Salmonella spp. in feeder calves. Am J Vet Res. 1990;51:866–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deplano A, Vaneechoutte M, Verschraegen G, Struelens M J. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis strains by PCR analysis of inter-IS256 spacer length polymorphisms. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2580–2587. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2580-2587.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Echeita M A, Usera M A. Chromosomal rearrangements in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi affecting molecular typing in outbreak investigations. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2123–2126. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.2123-2126.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fadl A A, Nguyen A V, Khan M I. Analysis of Salmonella enteritidis isolates by arbitrarily primed PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:987–989. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.987-989.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frech G, Weide-Botjes M, Nussbeck E, Rabsch W, Schwarz S. Molecular characterization of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium DT009 isolates: differentiation of the live vaccine strain Zoosaloral from field isolates. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;167:263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman C R, Stoeckle M Y, Johnson W D, Jr, Riley L W. Double-repetitive-element PCR method for subtyping Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1383–1384. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1383-1384.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haeghebert S, Le Querrec F, Vaillant V, Delarocque Astagneau E, Bouvet P. Les toxi-infections alimentaires collectives en France en 1997. Bull Epidémiol Hebdomadaire. 1998;41:177–181. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henckes G, Vannier F, Seiki M, Ogasawara N, Yoshikawa H, Seror-Laurent S J. Ribosomal RNA genes in the replication origin region of Bacillus subtilis chromosome. Nature. 1982;299:268–271. doi: 10.1038/299268a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilton A C, Penn C W. Comparison of ribotyping and arbitrarily primed PCR for molecular typing of Salmonella enterica and relationships between strains on the basis of these molecular markers. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;85:933–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1998.tb05256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerouanton A, Brisabois A, Grout J, Picard B. Molecular epidemiological tools for Salmonella Dublin typing. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;14:25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kostman J R, Alden M B, Mair M, Edlind T D, LiPuma J J, Stull T L. A universal approach to bacterial molecular epidemiology by polymerase chain reaction ribotyping. J Infect Dis. 1992;171:204–208. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagatolla C, Dolzani L, Tonin E, Lavenia A, Di Michele M, Tommasini T, Monti-Bragadin C. PCR ribotyping for characterizing Salmonella isolates of different serotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2440–2443. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2440-2443.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landeras E, Mendoza M C. Evaluation of PCR-based methods and ribotyping performed with a mixture of PstI and SphI to differentiate strains of Salmonella serotype Enteritidis. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:427–434. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-5-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu S L, Sanderson K E. Homologous recombination between rrn operons rearranges the chromosome in host-specialized species of Salmonella. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;164:275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Millemann Y, Lesage M-C, Chaslus-Dancla E, Lafont J-P. Value of plasmid profiling, ribotyping and detection of IS200 for tracing avian isolates of Salmonella typhimurium and enteritidis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:173–179. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.173-179.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Millemann Y, Lesage-Descauses M-C, Lafont J-P, Chaslus-Dancla E. Comparison of random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus-PCR for epidemiological studies of Salmonella. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;14:129–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller S A, Dykes D D, Polesky H F. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nastasi A, Mammina C. Epidemiological evaluation by PCR ribotyping of sporadic and outbreak-associated strains of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. Res Microbiol. 1995;146:99–106. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)80274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng I, Liu S L, Sanderson K E. Role of genomic rearrangements in producing new ribotypes of Salmonella typhi. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3536–3541. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3536-3541.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Odaert M, Berche P, Simonet M. Molecular typing of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis by using an IS200-like element. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2231–2235. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2231-2235.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odaert M, Devalckenaere A, Trieu-Cuot P, Simonet M. Molecular characterization of IS1541 insertions in the genome of Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:178–181. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.178-181.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olive D M, Bean P. Principles and applications of methods for DNA-based typing of microbial organisms. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1661–1669. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1661-1669.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otal I, Samper S, Asensio M P, Vitoria M A, Rubio M C, Gómez-Lus R, Martín C. Use of a PCR method based on IS6110 polymorphism for typing Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from BACTEC cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:273–277. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.273-277.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Picardeau M, Vincent V. Typing of Mycobacterium avium isolates by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:389–392. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.389-392.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plikaytis B B, Crawford J T, Woodley C L, Butler W R, Eisenach K D, Cave M D, Shinnick T M. Rapid, amplification-based fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1537–1542. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-7-1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puyalto C, Colmin C, Laval A. Salmonella typhimurium contamination from farm to meat in adult cattle. Descriptive study. Vet Res. 1997;28:449–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridley A, Threlfall E J. Molecular epidemiology of antibiotic resistance genes in multiresistant epidemic Salmonella typhimurium DT104. Microb Drug Resist. 1998;4:113–118. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ross B C, Dwyer B. Rapid, simple method for typing isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by using the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:329–334. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.329-334.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Lupski J R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application of fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weide-Botjes M, Kobe B, Lange C, Schwarz S. Molecular typing of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Hadar: evaluation and application of different typing methods. Vet Microbiol. 1998;61:215–227. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(98)00181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson K. Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, et al., editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Son, Inc.; 1987. pp. 2.4.1–2.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wray C, McLaren I M, Jones Y E. The epidemiology of Salmonella typhimurium in cattle: plasmid profile analysis of definitive phage type (DT) 204c. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:483–487. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-6-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wray C, Todd N, McLaren I M, Beedell Y E. The epidemiology of salmonella in calves: the role of markets vehicle. Epidemiol Infect. 1991;107:521–525. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800049219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoder S, Argueta C, Holtzman A, Aronson T, Berlin O G W, Tomasek P, Glover N, Froman S, Stelma G., Jr PCR comparison of Mycobacterium avium isolates obtained from patients and foods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2650–2653. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2650-2653.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]