Abstract

The objective of this study is to develop resveratrol (RES) loaded polyethylene glycols (PEGs) modified chitosan (CS) nanoparticles (NPs) by ionic gelation method for the treatment of glaucoma. While increasing the concentration of PEG, the particle size and polydispersity index of the formulations increased. Entrapment efficiency and RES loading (RL) of NPs decreased while increasing PEG concentration. The in vitro release of NPs showed an initial burst release of RES (45%) followed by controlled release. Osmolality of formulations revealed that the prepared NPs were iso‐osmolar with the tear. Ocular tolerance of the NPs was evaluated using hen's egg test on the chorioallantoic membrane and it showed that the NPs were non‐irritant. RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs shows an improved corneal permeation compared with RES dispersion. Fluorescein isothiocyanate loaded CS NPs accumulated on the surface of the cornea but the PEG‐modified CS NPs crossed the cornea and reached retinal choroid. RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs reduced the intra‐ocular pressure (IOP) by 4.3 ± 0.5 mmHg up to 8 h in normotensive rabbits. These results indicate that the developed NPs have efficient delivery of RES to the ocular tissues and reduce the IOP for the treatment of glaucoma.

Inspec keywords: conducting polymers, nanoparticles, nanomedicine, drug delivery systems, particle size, nanofabrication, organic compounds, biomembranes, cellular biophysics, eye, vision defects, biological tissues

Other keywords: RES‐loaded pegylated CS NP, efficient ocular delivery, resveratrol loaded polyethylene glycol modified chitosan nanoparticles, ionic gelation method, glaucoma treatment, particle size, polydispersity index, entrapment efficiency, RES loading, PEG concentration, in vitro release, osmolality formulations, ocular tolerance, hen egg testing, chorioallantoic membrane, improved corneal permeation, RES dispersion, fluorescein isothiocyanate loaded CS NP, cornea surface, reached retinal choroid, intraocular pressure, normotensive rabbits, RES delivery, ocular tissues

1 Introduction

Glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide. Over 8.4 million people were affected by primary glaucoma in 2010 and it might rise up to 11.1 million by 2020 [1, 2]. In our day‐today life, eyes are being continuously exposed to the light and its internal tissues generate large number of free radicals. These unfavourable intra‐cellular concentration of free radicals are key for various diseases associated with eye such as cataract [3, 4], uveitis [5, 6], retrolental fibroplasias [7], glaucoma [8, 9] and age‐related macular degeneration [10, 11]. Anti‐oxidants are present naturally in the ocular tissues but these concentrations are not enough to neutralise the free radicals that fail to control the damages of cellular macromolecules [12, 13, 14, 15].

Generally, excessive free radicals and oxidative stress cause apoptosis in retinal ganglion cell (RGC) and damage the trabecular meshwork (TM). RGC apoptosis leads to glaucomatous optic neuropathy and oxidative stress damage of TM cells causes blockage of aqueous humour outflow. These are the main causes of glaucoma caused by increase in intra‐ocular pressure (IOP) [16, 17, 18]. Moreover, endothelin (ET) is the most potent vasoactive peptide present in ocular tissues that plays a potential role in the pathogenesis of glaucoma. ET levels increased in the TM cells causes TM channel contraction that reduce the aqueous humour outflow. In addition, ET‐1 evokes apoptosis of RGC by reducing the blood flow to the RGC [19]. Earlier reports state that oxidative stress mediated by reactive oxygen species induces ET‐1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. They found that the reactive oxygen species can increase ET‐1 production in cultured endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells. Its interaction with vasoconstrictive oxygen derived radicals such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anions (O2 −) and hydroxyl radicals (OH−) has been investigated and the maximum results are positive [20]. By literatures, these problems are able to control by potent anti‐oxidants.

Resveratrol (RES) is a potent drug present in many plants such as grapes, berries, nuts red wine etc. Owing to its vascular enhancing properties and free radical neutralising property, the RES prevents ocular diseases such as age‐related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma [21, 22, 23, 24]. Besides, RES significantly decreases the ET‐1 secretion and ET‐1 messenger RNA levels in human [25]. Recent studies focused the RES for prevention and treatment of glaucoma due to effectively decreased production of intra‐cellular reactive oxygen species and inflammatory markers such as interleukin‐1 α (IL‐1), IL‐6, IL‐8 and endothelial‐leukocyte adhesion molecule‐1. In addition, RES treatment has been reducing the expression of the cellular senescence markers sa‐β‐galactosidase, lipofuscin, lipid peroxidation end products and other carbonylated proteins. RES has reported that to have significant effect on prevention of the TM cells damage in primary open angle glaucoma patients [26]. Prihan et al. demonstrated that significant neuroprotective effect of the both RES and riluzole alone or in combination on RGC survival in the experimental model of glaucoma. The topical application of multiple administrations of RES showed lowering of IOP which was associated with increased levels of aqueous matrix metalloproteinase‐2, normalisation of TM morphology (significantly reduced TM thickness and increased number of TM cells), improved retinal morphology and restoration of retinal redox status [27, 28].

Nanoparticles (NPs) as a carrier provide numerous advantages over the conventional ocular drug delivery systems because of their ability to protect the entrapped drug molecule while transporting to various compartments of the ocular tissues. NPs containing chitosan (CS) form a strong electrostatic interaction with sialic acid groups of mucus or with the negatively charged epithelial surfaces that helps to prolong the delivery of the loaded drugs [29, 30]. However, CS has some drawbacks such as it is only soluble in acetic aqueous medium and its mechanical properties are not so good for some biomedical application. Therefore, many researchers tried to modify/link CS with other polymers [31]. CS NPs reported increased delivery of cyclosporin A to the corneal and conjunctival surfaces, providing long‐term drug levels but did not enhance the penetration of the drug into the inner part of the eye [32]. The food and drug administration approved polyethylene glycol (PEG) with CS combination plays a major role in ocular delivery. PEG is water soluble polymer, available with various molecular weights that show many useful properties such as protein resistance and immunogenicity. PEG has been frequently chosen as ocular drug carrier due to their potential to cross the ocular barriers and minimal toxicity [33]. PEG on the surface of CS NPs can modulate the interfacial properties of the carrier, influence on drug absorption and increase the permeability of the loaded drug(s) across the cellular membranes through transcellular pathway [34]. So, we aim to develop RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs prepared by the ionic gelation method for improved delivery of RES to the cornea and efficiently reduce the IOP for the treatment of glaucoma.

2 Materials and method

2.1 Materials

RES and CS were received as gift sample from Safetabe life sciences, Pondicherry and Cognis, Mumbai, India, respectively. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA. PEG (2000, 4000 and 6000) was purchased from Merck Life Sciences Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India. Dimethylsulphoxide, acetonitrile, other reagents and solvents used were of analytical grade.

2.2 Preparation of RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs

PEG‐modified CS NPs were prepared by the ionic gelation method using CS and TPP solutions. CS was dissolved in 20 ml of acetic aqueous solution (2% v/v). TPP and different concentrations of PEG (2.5, 5 and 7.5 mg/ml) with various molecular weights (2000, 4000 and 6000) were dissolved in double distilled water. Accurately weighed RES was dissolved in ethanol and the RES solution was added dropwise into the CS solution, followed by addition of TPP: PEG solution under constant magnetic stirring. The formed opalescent suspensions were subjected to centrifugation at 15,000 rpm to collect the NPs and dried under vacuum [35]. Nine formulations (FR1–FR9) were prepared by the above procedure and the compositions were given in Table 1. The formulation without PEG (FR) was prepared in a similar method.

Table 1.

Composition of RES‐loaded CS NPs and PEG‐modified CS NPs

| Formulation code | PEG (molecular weight) | PEG concentration, % | CS: TPP | RES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR | — | — | 1 mg/ml | 1 mg/ml |

| FR1 | 2000 | 0.25 | ||

| FR2 | 0.5 | |||

| FR3 | 0.75 | |||

| FR4 | 4000 | 0.25 | ||

| FR5 | 0.5 | |||

| FR6 | 0.75 | |||

| FR7 | 6000 | 0.25 | ||

| FR8 | 0.5 | |||

| FR9 | 0.75 |

2.3 Particle size, charge, polydispersity index and morphology

Mean particle size, charge and polydispersity index of the formulations (FR1–FR9) and FR were determined by Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The samples were diluted with distilled water and particle size was analysed using the software. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to examine the shape and morphology of NPs. FR and FR1 NPs were examined for a qualitative assessment of shape and morphology using TEM (Philips EM430 TEM, USA). NPs were fixed on the copper (Cu) grids with 0.5% (w/v) phosphotungstic acid staining for TEM analysis.

2.4 Determination of RES loading (RL) and encapsulation efficiency

RES content in CS NPs and PEG‐modified CS NPs were determined by dissolving accurately weighed NPs in aqueous acetic acid solution and further diluting with freshly prepared phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS). The absorbance of the solution was measured at 320 nm for RES by using ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometer (1700, Shimadzu, Japan) [36]. The equivalent RES concentration was determined using the calibration curve. Calibration curve for RES was linear from 1 to 5 µg/ml and the R 2 value was 0.998. Experiments were carried out in triplicates for each formulation and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviations. The percentage of RL (% RL) and the encapsulation efficiency (% EE) of the NPs were calculated using equations indicated below

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

2.5 In vitro RES release studies

In vitro release of RES from the NPs was determined by dialysis bag method using PBS (pH 7.4) as a dissolution medium. NPs (10 mg) were dispersed in 2 ml PBS and transferred into dialysis bag (12–14 kDa cut‐off, Himedia Labs, India) which is placed in a beaker containing 40 ml of PBS under magnetic stirring at 600 rpm at 37°C [37]. At predetermined time intervals, aliquots of samples were withdrawn and replaced with same amount of fresh PBS to maintain the sink condition of dialysis bag. The aliquots were analysed for RES release from the NPs by UV spectrophotometer at 320 nm.

2.6 Fourier‐transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis

FTIR spectra were recorded to investigate the possibility of chemical interactions between the RES and the polymers in the NPs. Samples were crushed with potassium bromide to get the pellets and the spectra of RES, PEG, CS and formulated NPs were recorded from 4000 to 400 cm−1 using FTIR spectrometer (6300 series, Shimadzu, Japan) with 32 scans and resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.7 Powder X‐ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis

PXRD of CS, PEG, RES and NPs were obtained using powder X‐ray diffractometer (JEOL, JDX 8030, DX‐MAP2, Tokyo, Japan) using Ni filtered Cu K‐α radiation (40 kV, 20 mA) to determine the nature of the sample (amorphous/crystalline).

2.8 Osmolality and pH measurement study

Osmolality of FR1 NPs, FR NPs and RES dispersion with corresponding vehicle were measured using single sample freezing point osmometer (OSMOMAT 3000, Gonotech GmbH, Germany). After calibration of the osmometer with reference standards (300 and 500 mOsm/kg H2 O), the osmolality of the samples were measured (50 µl samples were used) [38]. The pH of the NPs with corresponding vehicle was measured using a calibrated pH meter (PB‐11 model, Sartorius Corporation, USA).

2.9 Ocular irritation potential test

Hen's egg test method on the chorioallantoic membrane (HET‐CAM) was described by Luepke to determine the corrosive and irritant nature of the formulated NPs [39, 40]. For this paper, fresh fertile hen's eggs were collected and placed in an incubator at 37 ± 0.2°C and the relative humidity of 58 ± 2% was maintained for 8 days. On day 9, eggs were collected from the incubator and the air cells of the eggs were cut without disturbing the CAM. NPs were loaded in the discs and placed directly onto the CAM and observed for different time intervals for the symptoms of chorioallantoic blood vessels haemorrhage or lysis occurrence on the CAM [41, 42]. The scores were recorded according to the scoring schemes shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Ocular irritation potential – scoring method for HET‐CAM test

| Effect | Score | Inference |

|---|---|---|

| no visible haemorrhage | 0 | non‐irritant |

| just visible membrane discolouration | 1 | mild‐irritant |

| partially membrane haemorrhage or discolouration | 2 | moderately irritant |

| totally membrane haemorrhage or discolouration | 3 | severe‐irritant |

2.10 Ex vivo transcorneal permeation study

Ex vivo rabbit transcorneal permeation study of the formulated NPs was approved by Institutional animal ethical committee and it was carried out using modified side‐by‐side franz diffusion cell. The rabbit cornea was carefully separated along with 2–4 mm of surrounding scleral tissue. The excised cornea was placed between the donor and receptor cells. Both the cells were stirred using magnetic stirrer at 150 rpm. NPs and RES dispersion were placed in donor cell containing PBS and the samples were withdrawn from the receptor cell at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120 and 180 min and replaced with fresh PBS. The withdrawn samples were analysed using reversed‐phase high‐performance liquid chromatography at 320 nm [43].

2.11 FITC loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs ocular permeation study

FR and FR1 NPs were labelled by adding FITC [0.03% (w/v)] in dimethylsulphoxide and then processed the same RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs synthesis method to determine the efficiency of NPs crossing the ocular barriers. FITC was dissolved in PBS to a concentration of 0.03% (w/v) and taken as reference. Rabbits were placed in restraint boxes and 15 μl instillations of the FITC and RES‐loaded NPs were topically administered in the inferior conjunctival cul‐de‐sac of the right eye for four times, while FITC solution was instilled in the left eye as the control. After 2 h of the instillation, the eyes were washed with PBS and the rabbits were sacrificed. The corneas were excised and fixed in optimal cutting temperature medium and frozen at −22°C, then sectioned into 8 µm and observed using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan) [44].

2.12 IOP lowering effect of NPs in normotensive rabbits

RES dispersion, RES‐loaded CS NPs and RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs were tested for their IOP lowering efficiency in normotensive rabbits (2–2.5 kg) and the results were compared with marketed eye drops (0.5% timolol maleate). In general, IOP could not be lowered below the episcleral venous pressure (10 mmHg) while doing IOP reducing efficiency in normotensive rabbits [45]. Institutional animal ethics committee has approved to study the IOP reducing efficacy of NPs in widely accepted animal model normotensive rabbits. Rabbits were maintained with a light–dark cycle (12/12 h) in a controlled temperature and humidity. Six groups of animals with three in each group received control, RES, FR1 (0.5, 1.0, and 1.5%), FR (0.5%) and marketed eye drops. For analysing the IOP, cornea of each rabbit was anaesthetised by instilling 50 μl of lidocaine before test formulations being applied. All the right eye of the rabbit's received 50 μl (single dose) of test samples. After instillation of samples, the IOP reducing efficacy was measured at predetermined time interval (15, 30 and 45 min) over the period of 8 h by tonometer (Reichert, USA) [46, 47].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Ionic gelation method, particle size and polydispersity index

The characteristics of the PEG‐modified CS/TPP particles prepared with different concentrations and molecular weights of PEG were studied. Chemical modifications of CS under diverse conditions are usually accompanied by different problems including poor reaction, difficulty in specific substitution and structural non‐uniformity of the outcomes [48]. So, we had chosen the ionic gelation method of CS with TPP for RES encapsulation without major alteration. NPs are formed immediately on mixing of the two phases through inter‐ and intra‐molecular linkages created between TPP phosphates and CS amino groups [49, 50]. We prepared the PEG‐modified CS NPs with varying concentration and molecular weight of PEG (Fig. 1). PEGylation on CS NPs refers to the decoration of a particle surface by covalent grafting, entrapping or adsorbing of PEG chains [51]. Association of PEG in the CS NPs formulation increased the particle size to 129.8 nm (Table 3) compared with the without PEG loaded formulation (14 nm) and these findings are similar with the previous report [52]. The result indicates that the PEG is bound/trapped in CS‐TPP matrix. Unlike TPP, PEG cannot gelate with CS, which may compete with TPP in their interaction with the amine groups of CS. Consequently, increase in the concentration and molecular weight of PEG leads to an increase in size and polydispersity index and a decrease of the positive charge of the NPs. PEG decreases the positive charge of NPs and thus improves the biocompatibility of the NPs [53, 54].

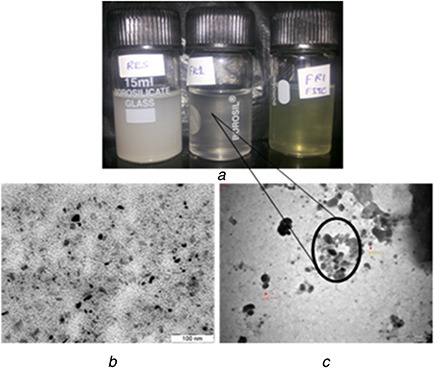

Fig. 1.

PEG‐modified CS NPs with varying concentration and molecular weight of PEG

(a) Images of RES NPs formulation: RES‐RES in distilled water, FR1‐RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs and FR1‐FITC – RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs containing FITC, (b) TEM image of FR, (c) TEM image of FR1

Table 3.

Particle size, polydispersity index, RL, and entrapment efficiency of the NPs

| Formulation code | Average particle size, nm | Polydispersity index | RES loadinga, % | EE of RESa, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR | 14 | 0.231 | 7.48 ± 0.12 | 92.08 ± 1.50 |

| FR1 | 129.8 | 0.351 | 8.04 ± 0.09 | 91.89 ± 1.11 |

| FR2 | 167.9 | 0.334 | 5.18 ± 0.06 | 86.87 ± 1.08 |

| FR3 | 173.9 | 0.305 | 4.91 ± 0.11 | 86.52 ± 1.94 |

| FR4 | 183.1 | 0.367 | 7.52 ± 0.14 | 82.77 ± 1.59 |

| FR5 | 467.4 | 0.459 | 7.18 ± 0.08 | 72.83 ± 0.87 |

| FR6 | 499.1 | 0.771 | 6.96 ± 0.21 | 62.96 ± 1.89 |

| FR7 | 565.7 | 0.485 | 8.02 ± 0.13 | 89.60 ± 1.47 |

| FR8 | 671.8 | 0.488 | 5.30 ± 0.10 | 83.68 ± 1.59 |

| FR9 | 755.3 | 0.623 | 4.27 ± 0.12 | 62.25 ± 1.75 |

a Results are depicted as mean ± SD (n = 3).

EE – Entrapment efficiency and nm – nanometer.

Earlier study indicated that the uptake of 100 nm sized particles in rabbit conjunctival epithelial cells was higher compared with larger sized particles. Lower sized particles were able to cross the cornea and corneal barriers effectively [55]. At the same time very small sized particles (<20 nm) are cleared by blood and lymphatic system without achieving any ocular effect [56].

3.2 EE, RL and TEM analyses of the formulated NPs

In most of the NPs delivery systems, the drug carrying capacity is defined in terms of the EE. The % relative standard deviation of five replicate analysis for method precision, system precision, intra–inter day and analyst variations are found to be <1.0% in the validation study. Increasing the concentration of PEG in ionic gelation method leads to decrease in the EE and loading of RES in CS‐TPP matrix which is shown in Table 3. Hence, the PEG has highly competed with the RES during the ionic gelation method of CS NPs formulation. Fig. 1 shows that CS NPs are smaller in shape compared with the PEG‐modified CS NPs and it confirms the PEG loading in the formulations and maintains regular shape of the particles.

3.3 In vitro RES release studies

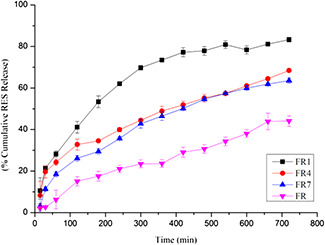

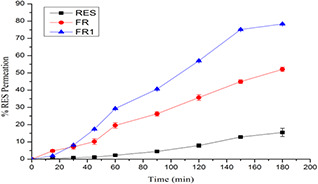

The polymeric NPs system showed initial rapid release of the RES and followed by slow release up to 12 h. This burst release indicated that the RES are adsorbed on the surface of NPs. The release medium diffuses into the NPs and releases the RES slowly. The release was slow because of the degradation rate and time of CS and various molecular weight of PEG. Fig. 2 shows the cumulative release of the RES from different molecular weight PEG and without PEG NPs. The initial release of RES from the lower molecular mass PEG was rapid than large molecular weight and it is similar to the previous report [21]. From the result, the higher molecular weight PEG releases the RES slowly compared with the lower molecular weight due to RES entrapment in the higher molecular chain. FR1 shows better controlled release pattern (81%) than the FR4 and FR7. The CS NPs release RES very slowly compared with the PEG‐coated NPs, because of tight junction between the CS and TPP. RES carried by CS NPs can be released through degradation and corrosion of CS leading to a clear sustained release effect.

Fig. 2.

In vitro RES release from FR NPs and PEG‐modified CS NPs (FR1, FR4 and FR7)

From the particle size (129 nm), entrapment efficiency (91.89 ± 1.11%), RL (8.04 ± 0.09%) and RES release (81%) studies, FR1 is the better formulation for the further evaluation.

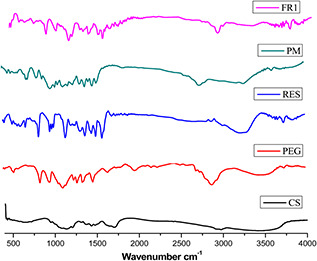

3.4 FTIR analysis

FTIR studies of RES, PEG, CS, physical mixture of excipients and formulated NPs were shown in Fig. 3. RES has a peak at 3232 cm−1 indicating typical O–H strong stretching, 1587 cm−1 points out to C–C stretching aromatic double bond and 1382 cm−1 specifies the C–O stretching. The typical trans‐olefinic band was also observed at 987 cm−1 [57].

Fig. 3.

FTIR spectra of CS – chitosan, PEG – polyethylene glycol, RES – resveratrol, PM – physical mixer of excipients and FR1‐NP formulation

Strong C–O–C stretching and the N–H primary amine of CS were confirmed at 1243 and 1612 cm−1, respectively. PEG was confirmed by the O–H stretch at 3459 cm−1 and the characteristic C–O–C stretching vibration was confirmed by the repeated –OCH2 CH2 – units of the PEG backbone at 1170 cm−1. PEG also showed distinct peaks at 1280, 960 and 842 cm−1 [58]. Physical mixer of excipients shows no changes in the functional groups. NPs formulation with 3421 cm−1 peak may have hydrogen bond formed between the polymer and RES. The peak at 1747 cm−1 in NPs conformed that the C–O–C stretching of the repeated –OCH2 CH2 – units of the PEG backbone and it also contains the distinct PEG peaks at 1257 and 952 cm−1. These results indicate that the PEG and RES were incorporated in the CS NPs formulation. All the characteristic IR peaks (1587 and 1382 cm−1) related to RES were also appearing in the IR spectrum of NPs.

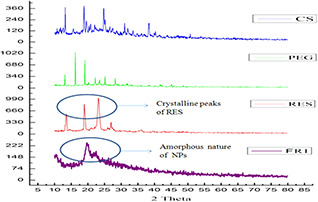

3.5 PXRD analysis

PXRD pattern of polymers, RES and PEG‐modified CS NPs are shown in Fig. 4. The PXRD pattern of CS showed no sharp peak, indicating its amorphous nature. Crystalline structure of RES shows peaks at 13.11°, 16.24°, 19.07°, 20.20°, 22.22°, 23.46°, 25.13° and 28.22°. PXRD pattern of RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs revealed remarkable decrease of the crystalline diffraction peaks of RES and indicates its amorphisation in FR1 NPs. From the free energy concept, the dissolution process of amorphous form is more soluble than the crystalline form. Moreover, also low energy is required to separate the randomly arranged amorphous form compared with the crystalline form.

Fig. 4.

PXRD spectra of CS – chitosan, PEG – polyethylene glycol, RES – resveratrol and FR1‐NP formulation (amorphous nature)

3.6 Osmolality and pH

The osmolality of the normal tear film equals 310–350 mOsm/kg and is changed by the major inorganic ions such as Na+, K+, Cl−, HCO3− and proteins. The mean pH value of normal tears is about 7.4. The pH is altered by age and disease (between 5.2 and 9.3). Osmolality is determining the function of the number of solute present in the solution [59]. Osmolality of the prepared NPs were evaluated by micro‐osmometer. The hypertonic or hypotonic solution can cause pain or irritation to the eye. Therefore, it is important to check the osmolality and pH of the NPs with the corresponding vehicles. The eye has a large tonicity tolerance ranging from 0.7 to 1.4% sodium chloride solution, and within these limits there is no pain to be expected. The results showed that the osmolality of the NPs are within the acceptable range (321 ± 20–324 ± 40 mOsm). It concludes that the prepared NPs were iso‐osmolar with the tear and pH value (6.9 ± 0.20–7.3 ± 0.40) almost near to the tear pH range [60].

3.7 Ocular irritation potential

The CAM is a tissue containing arteries, veins and capillaries and it is technically uncomplicated to study the ocular irritation property of the test samples. The well‐developed CAM vascularisation provides an ideal model for ocular irritation studies [61]. The irritation effect of NPs and control sample on the fertile egg's CAM are determined. The samples were placed on the CAM at the 9th day of incubated fertile egg and the temperature and relative humidity were maintained at 37 ± 0.2°C and 58 ± 2%, respectively [39]. A mean score of 0 was obtained for normal saline. RES‐loaded CS NPs were non‐irritant up to 8 h (mean score 0) while the mean score was found to be 1 up to 24 h but RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs were non‐irritant up to 24 h. These results show that the RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs are non‐irritant and well tolerated than the CS NPs.

3.8 Ex vivo RES‐loaded NPs transcorneal permeation study

For the external ocular diseases such as eye infection and keratitis sicca is in the ocular mucosa the drug permeation has not much attention. However, corneal permeation for the targeting intra‐ocular diseases such as glaucoma or uveitis is desirable [62]. From the corneal permeation study, higher amount of RES is permeated across the excised rabbit cornea from the PEG‐modified CS NPs (78.34 ± 0.39) than the CS NPs (52.07 ± 1.24) and RES dispersion (Fig. 5). The higher order of permeation was observed due to permeation enhancement characteristics of CS and PEG in the NPs. Improved permeation can be attributed to prolonged retention owing to mucoadhesion of NPs because of ionic interaction between positively charged amino group of CS and negatively charged mucin available at the surface of the cornea [30]. The amphiphilic nature with lower particle size of the PEG containing FR1 NPs are distributed throughout the cornea and it assists in permeation of incorporated RES. CS improves the RES corneal permeation due to the endocytic uptake and para‐cellular transport by widening of tight junction [63] and adhesive nature of CS is strengthened under neutral or the corneal pH. Hence, it has a better adhesive property in the tear film (pH 7.4) [64]. Even a long time retention of CS NPs in the cornea does not show any destructive effect in the mucin layer [65].

Fig. 5.

Ex‐vivo trans corneal permeation of RES dispersion (RES), RES‐loaded CS NPs (FR) and PEG modified CS NPs (FR1)

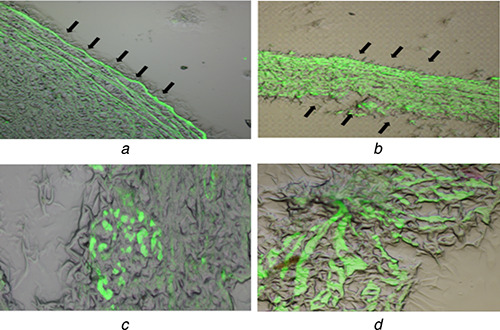

3.9 FITC and RES‐loaded NPs ocular permeation study

NPs were labelled with FITC to study the ability to transport the NPs containing RES into the cornea which is shown in Fig. 6. From fluorescence microscopy, it can be seen that both CS and PEG‐modified CS of FITC loaded NPs can reach the cornea after instillation to inferior conjunctival cul‐de‐sac. For CS NPs, fluorescence could only be detected at the superficial epithelium of the cornea. However, PEG‐modified CS NPs has increased fluorescence signal at the inner site of the cornea. This result indicates that the PEG‐modified CS NPs have the ability to enhance penetration of the RES into the cornea. PEG‐modified CS NPs provide an adequate penetration and constant release of RES. We find that the PEG‐modified CS NPs reached vitreous network components and accumulated in the retinal choroid due to the amphiphilic nature of NPs and this matched with earlier findings [66, 67, 68, 69]. Earlier study found that PEG chains attached to the surface or corona of NPs exhibit rapid motion in an aqueous medium, which may lead to the crossing of NPs into ocular barriers [70].

Fig. 6.

Ocular permeation of NPs using FITC (a) FITC‐RES‐CS NPs in surface of the cornea, (b) FITC‐RES‐PEG‐CS NPs in both inside and outside of the cornea, (c) FITC‐RES‐CS NPs in retinal choroid, (d) FITC‐RES‐PEG‐CS NPs in retinal choroid

PEG coating in the CS NPs does not have a role in enhancing interaction with corneal epithelium but it facilitates the transcellular transport of the incorporated drugs. PEGylated CS NPs have strong hydrophilicity and neutral charge provided by PEG coating, which helps the diffusion of NPs. PEGylation was also demonstrated to improve cytoplasmic transport of NPs and penetration into vitreous gel. The results of permeability studies with rabbit conjunctiva indicate that the neutral, hydrophilic low molecular weight molecules were able to permeate efficiently. Furthermore, the vitreous gel is composed of more than 98% water and the pore size does not exceed 575 nm. Hence, the lower nanosized non‐adhesive hydrophilic PEG NPs are able to penetrate in the sclera and vitreous gel. Earlier study found that the efficient uptake of PEGylated CS NPs with higher transfection efficacy was compared with that of CS NPs [52, 71, 72].

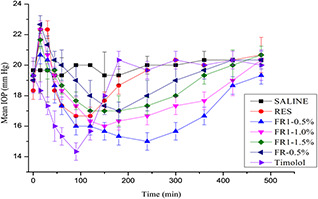

3.10 IOP lowering effect of NPs in normotensive rabbits

We examined the IOP lowering effects of the RES‐loaded NPs in normotensive rabbits and notified the values after instillation of a 50 μl dose of FR, FR1, 0.5% timolol maleate, RES dispersion and control. Though experimental models of ocular hypertension can be achieved by several methods including water loading [73], intravenous glucose administration [74] and chymotrypsin induced ocular hypertension [75], these models have some drawbacks such as complicated procedures, short duration of ocular hypertension and variability in the extend or occurrence of ocular hypertension [76]. So, we chose the widely accepted normotensive rabbit models for the study.

From this paper, we observed maximum IOP lowering level of 5.5 ± 0.5 mmHg within 2 h for 0.5% timolol maleate and RES dispersion attained maximum value of 3.5 ± 0.5 mmHg within 90 min. This effect quickly decreased and stopped completely within 4 h, whereas NPs produced a remarkable and sustained reduction of IOP. FR1 (0.5%) showed better pharmacological effect compared with the FR (0.5%) and the peak effect was noted at 4 h of FR1 (0.5%) with reduction of IOP value up to 4.3 ± 0.5 mmHg, which delayed decrease of IOP than RES, owing to slow release of RES from NPs compared with RES dispersion. The other concentration of FR1 (1 and 1.5%) showed pharmacological effect value of 4 ± 0.5 and 3.5 ± 0.5 mmHg, which was sustained up to 8 h (Fig. 7). RES dispersion showed pulse effect of 2.5 ± 0.5 mmHg within 60 min due to higher concentration of RES immediately available. However, in the case of NPs, RES was entrapped/cross‐linked in polymer (PEG‐CS) matrix. The prolonged duration of action was due to increased mucoadhesion of CS that interacts with mucin effectively. In addition, the PEG‐CS hybrid has an influence on the reduction of reactive oxygen spices generation [77]. Hence, developed formulation of FR1 NPs (0.5%) was found to be effective for lowering IOP in normotensive rabbit eye when compared with FR NPs and RES dispersion.

Fig. 7.

IOP reducing efficiency of the topically applied FR, FR1, RES dispersion, marketed formulation and control in normotensive rabbits. Data represent the IOP value changes from 0 min to 8 h and expressed as the mean ± SD

4 Conclusion

Ionic gelation method can be used for the safest preparation of RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS‐NPs. Particle size and polydispersity index of the formulations increased on increasing the concentration of PEG and it indicates that PEG and RES occupies the CS‐TPP complex. Also increasing concentration of PEG in the NPs reduces the RL because it highly competes with RES. XRD confirms that the crystalline nature of the RES is changed into partially amorphous in the PEG‐modified CS NPs. From the in vitro study, RES released from the PEG‐modified CS NPs was in a sustained manner than the RES‐loaded CS NPs. PEG‐modified CS NPs is non‐irritant due to its iso‐osmolar and low‐irritant effects in the CAM. Ex vivo corneal permeation study including FITC loaded NPs reveal that the RES‐loaded PEG‐modified CS NPs is more permeable than the RES‐loaded CS NPs and RES dispersion. Animal studies using PEG‐modified CS NPs exhibited a promising level of IOP reduction without pulse effect as compared with RES dispersion. Developed RES‐loaded PEG‐modified RES‐loaded CS NPs has sustained RES release, crossed the ocular barriers, reached up to retinal choroid and reduced the IOP effectively for the treatment of glaucoma.

5 Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India, New Delhi for financial support under the project no. BT/PR3804/MED/32/220/2011. We acknowledge National Facility for Drug Development (NFDD), Bharathidasan Institute of Technology Campus, Anna University, Tiruchirappalli for providing the facilities (Particle size analysis and Florescence microscope study).

6 References

- 1. Medeiros F.A. Weinreb R.N.: ‘Medical backgrounders: glaucoma’, Drugs Today (Barc), 2002, 38, (8), pp. 563 –570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Susanna R. Jr. De Moraes C.G. Cioffi G.A. et al.: ‘Why do people (still) go blind from glaucoma?’, Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol., 2015, 4, (2), p. 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doganay S. Borazan M. Iraz M. et al.: ‘The effect of resveratrol in experimental cataract model formed by sodium selenite’, Curr. Eye Res., 2006, 31, (2), pp. 147 –153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thiagarajan R. Manikandan R.: ‘Antioxidants and cataract’, Free Radic. Res., 2013, 47, (5), pp. 337 –345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yadav U.C. Kalariya N.M. Ramana K.V.: ‘Emerging role of antioxidants in the protection of uveitis complications’, Curr. Med. Chem., 2011, 18, (6), pp. 931 –942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Selvi R. Angayarkanni N. Biswas J. et al.: ‘Total antioxidant capacity in Eales’ disease, uveitis & cataract’, Indian J. Med. Res., 2011, 134, (1), pp. 83 –90 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson L. Schaffer D. Boggs T.R. Jr.: ‘The premature infant, vitamin E deficiency and retrolental fibroplasia’, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 1974, 27, (10), pp. 1158 –1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Erdurmus M. Yagcı R.O. Karadag R. et al.: ‘Antioxidant status and oxidative stress in primary open angle glaucoma and pseudoexfoliative glaucoma’, Curr. Eye Res., 2011, 36, (8), pp. 713 –718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kang J.H. Pasquale L.R. Willett W. et al.: ‘Antioxidant intake and primary open‐angle glaucoma: a prospective study’, Am. J. Epidemiol., 2003, 158, (4), pp. 337 –346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johnson E.J.: ‘Age‐related macular degeneration and antioxidant vitamins: recent findings’, Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care, 2010, 13, (1), pp. 28 –33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fletcher A.E. Bentham G.C. Agnew M. et al.: ‘Sunlight exposure, antioxidants and age‐related macular degeneration’, Arch. Ophthalmol., 2008, 126, (10), pp. 1396 –1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tanito M. Kaidzu S. Takai Y. et al.: ‘Correlation between systemic oxidative stress and intraocular pressure level’, PLoS One, 2015, 10, (7), p. e0133582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rahman K.: ‘Studies on free radicals, antioxidants and co‐factors’, Clin. Interv. Aging., 2007, 2, (2), pp. 219 –236 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tanito M. Kaidzu S. Takai Y. et al.: ‘Status of systemic oxidative stresses in patients with primary open‐angle glaucoma and pseudoexfoliation syndrome’, PLoS One, 2012, 7, (11), p. e49680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hammond B.R. Johnson B.A. George E.R.: ‘Oxidative photodegradation of ocular tissues: beneficial effects of filtering and exogenous antioxidants’, Exp. Eye Res., 2014, 129, pp. 135 –150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Munemasa Y. Kitaoka Y.: ‘Molecular mechanisms of retinal ganglion cell degeneration in glaucoma and future prospects for cell body and axonal protection’, Front. Cell. Neurosci., 2012, 6, p. 60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goel M. Picciani R.G. Lee R.K. et al.: ‘Aqueous humor dynamics: a review’, Open Ophthalmol. J., 2010, 4, pp. 52 –59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ammar D.A. Hamweyah K.M. Kahook M.Y.: ‘Antioxidants protect trabecular meshwork cells from hydrogen peroxide‐induced cell death’, Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol., 2012, 1, (1), p. 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yorio T. Krishnamoorthy R. Prasanna G.: ‘Endothelin: is it a contributor to glaucoma pathophysiology?’, J. Glaucoma, 2002, 11, (3), pp. 259 –270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kahler J. Ewert A. Weckmuller J. et al.: ‘Oxidative stress increases endothelin‐1 synthesis in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells’, J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol., 2001, 38, (1), pp. 49 –57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hooper A. Cassidy A.: ‘A review of the health care potential of bioactive compounds’, J. Sci. Food Agric., 2006, 86, (12), pp. 1805 –1813 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pandey K.B. Rizvi S.I.: ‘Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease’, Oxidative Med. Cell. Longevity, 2009, 2, (5), pp. 270 –278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anisimova N.Y. Kiselevsky M.V. Sosnov A.V. et al.: ‘Trans‐, cis‐ and dihydro‐resveratrol: a comparative study’, Chem. Cent. J., 2011, 20 (5), p. 88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bola C. Bartlett H. Eperjesi F.: ‘Resveratrol and the eye: activity and molecular mechanisms’, Graefes. Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol., 2014, 252, (5), pp. 699 –713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Song B.J. Caprioli J.: ‘New directions in the treatment of normal tension glaucoma’, Indian J. Ophthalmol., 2014, 62, (5), pp. 529 –537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Katas H. Alpar H.O.: ‘Development and characterisation of chitosan nanoparticles for siRNA delivery’, J. Control Release, 2006, 115, (2), pp. 216 –225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luna C. Li G. Liton P.B. et al.: ‘Resveratrol prevents the expression of glaucoma markers induced by chronic oxidative stress in trabecular meshwork cells’, Food Chem. Toxicol., 2009, 47, (1), pp. 198 –204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pirhan D. Yuksel N. Emre E. et al.: ‘Riluzole and resveratrol‐induced delay of retinal ganglion cell death in an experimental model of glaucoma’, Curr. Eye Res., 2016, 41, (1), pp. 59 –69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Razali N. Agarwal R. Agarwal P. et al.: ‘Role of adenosine receptors in resveratrol‐induced intraocular pressure lowering in rats with steroid‐induced ocular hypertension’, Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol., 2015, 43, pp. 54 –66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Casettari L. Vllasaliu D. Castagnino E. et al.: ‘PEGylated chitosan derivatives: synthesis, characterizations and pharmaceutical applications’, Prog. Polym. Sci., 2012, 37, (5), pp. 659 –685 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang M. Li X.H. Gong Y.D. et al.: ‘Properties and biocompatibility of chitosan films modified by blending with PEG’, Biomaterials, 2002, 23, (13), pp. 2641 –2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Campos A. Sanchez A. Alonso M.J.: ‘Chitosan nanoparticles: a new vehicle for the improvement of the ocular retention of drugs. Application to cyclosporin A’, Int. J. Pharm., 2001, 224, pp. 159 –168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bhattarai N. Ramay H.R. Gunn J. et al.: ‘PEG‐grafted chitosan as an injectable thermosensitive hydrogel for sustained protein release’, J. Control Release, 2005, 103, (3), pp. 609 –624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Quellec P. Gref R. Dellacherie E. et al.: ‘Protein encapsulation within poly(ethylene glycol)‐ coated nanosphere. II. Controlled release properties’, J. Biomed. Mater. Res., 1999, 47, pp. 388 –395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chuah L.H. Billa N. Roberts C.J. et al.: ‘Curcumin‐containing chitosan nanoparticles as a potential mucoadhesive delivery system to the colon’, Pharm. Dev. Technol., 2013, 18, (3), pp. 591 –599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Biasutto L. Marotta E. Garbisa S. et al.: ‘Determination of quercetin and resveratrol in whole blood‐implications for bioavailability studies’, Molecules, 2010, 15, (9), pp. 6570 –6579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sanna V. Siddiqui I.A. Sechi M. et al.: ‘Resveratrol‐loaded nanoparticles based on poly (epsilon‐caprolactone) and poly (D,L‐lactic‐co‐glycolic acid)‐poly(ethylene glycol) blend for prostate cancer treatment’, Mol. Pharm., 2013, 10, (10), pp. 3871 –3881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hippalgaonkar K. Adelli G.R. Hippalgaonkar K. et al.: ‘Indomethacin‐loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for ocular delivery: development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation’, J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther., 2013, 29, (2), pp. 216 –228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Luepke N.P.: ‘Hen's egg chorioallantoic membrane test for irritation potential’, Food Chem. Toxicol., 1985, 23, (2), pp. 287 –291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Steiling W. Bracher M. Courtellemont P. et al.: ‘The HET‐CAM, a useful in vitro assay for assessing the eye irritation properties of cosmetic formulations and ingredients’, Toxicol. In Vitro, 1999, 13, (2), pp. 375 –384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Krenn L. Paper D.H.: ‘Inhibition of angiogenesis and inflammation by an extract of red clover (Trifoliumpratense L.)’, Phytomedicine, 2009, 16, (12), pp. 1083 –1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Abdelkader H. Ismail S. Kamal A. et al.: ‘Design and evaluation of controlled‐release niosomes and discomes for naltrexone hydrochloride ocular delivery’, J. Pharm. Sci., 2011, 100, (5), pp. 1833 –1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rathore M.S. Majumdar D.K.: ‘Effect of formulation factors on in‐vitro transcorneal permeation of gatifloxacin from aqueous drops’, AAPS Pharm. Sci. Tech., 2006, 7, (3), p. 57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhou W. Wang Y. Jian J. et al.: ‘Self‐aggregated nanoparticles based on amphiphilic poly(lactic acid)‐grafted‐chitosan copolymer for ocular delivery of amphotericin B’, Int. J. Nanomed., 2013, 8, pp. 3715 –3728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kaur I.P. Garg A. Singla A.K. et al.: ‘Vesicular systems in ocular drug delivery: an overview’, Int. J. Pharm., 2004, 269, (1), pp. 1 –14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ammar H.O. Salama H.A. Ghorab M. et al.: ‘Nanoemulsion as a potential ophthalmic delivery system for dorzolamide hydrochloride’, AAPS Pharm. Sci. Tech., 2009, 10, (3), pp. 808 –819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Winum J.Y. Casini A. Mincione F. et al.: ‘Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: N‐(p‐sulfamoylphenyl)‐훼‐D‐ glycopyranosylamines as topically acting antiglaucoma agents in hypertensive rabbits’, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 2004, 14, (1), pp. 225 –229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hu Y.Q. Jiang H.L. Xu C.N. et al.: ‘Preparation and characterization of poly (ethylene glycol)‐g‐chitosan with water‐ and organosolubility’, Carbohydr. Polym., 2005, 61, (4), pp. 472 –479 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bodmeier R. Chen H. Paeratakul O.: ‘A novel approach to the delivery of microparticles or nanoparticles’, Pharm. Res., 1989, 6, pp. 413 –417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Janes K.A. Calvo P. Alonso M.J.: ‘Polysaccharide colloidal particles as delivery systems for macromolecules’, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., 2001, 47, (1), pp. 83 –97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Veronese F.M. Pasut G.: ‘Pegylation, successful approach for drug delivery’, Drug Discov. Today, 2005, 10, pp. 1451 –1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Malhotra M. Lane C. Tomaro‐Duchesneau C. et al.: ‘A novel method for synthesizing PEGylated chitosan nanoparticles: strategy, preparation, and in vitro analysis’, Int. J. Nanomed., 2011, 6, pp. 485 –494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wu Y. Yang W. Wang C. et al.: ‘Chitosan nanoparticles as a novel delivery system for ammonium glycyrrhizinate’, Int. J. Pharm., 2005, 295, (12), pp. 235 –245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Quellec P. Gref R. Perrin L. et al.: ‘Protein encapsulation within polyethylene glycol‐coated nanospheres. I. Physicochemical characterization’, J. Biomed. Mater. Res., 1998, 42, (1), pp. 45 –54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mendes J.B. Riekes M.K. de Oliveira V.M. et al.: ‘PHBV/PCL microparticles for controlled release of resveratrol: physicochemical characterization, antioxidant potential, and effect on hemolysis of human erythrocytes’, Sci. World J., 2012, 2012, p. 542937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Amrite A.C. Edelhauser H.F. Singh S.R. et al.: ‘Effect of circulation on the disposition and ocular tissue distribution of 20 nm nanoparticles after periocular administration’, Mol. Vis., 2008, 14, pp. 150 –160 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nagarwal R.C. Kant S. Singh P.N. et al.: ‘Polymeric nanoparticulate system: a potential approach for ocular drug delivery’, J. Control Release, 2009, 136, pp. 2 –13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Parveen S. Sahoo S.K.: ‘Long circulating chitosan/PEG blended PLGA nanoparticle for tumor drug delivery’, Eur. J. Pharmacol., 2011, 30, (23), pp. 372 –383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bayens V. Gurny R.: ‘Chemical and physical parameters of tears relevant for the design of ocular drug delivery formulations’, Pharm. Acta Helvetiae, 1997, 72, pp. 191 –202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Abelson M.B. Udell I.J. Weston J.H.: ‘Normal human tear pH by direct measurement’, Arch. Ophthalmol., 1981, 99, (2), p. 301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vasconcelos A. Vega E. Perez Y. et al.: ‘Conjugation of cell‐penetrating peptides with poly (lactic‐co‐glycolic acid)‐polyethylene glycol nanoparticles improves ocular drug delivery’, Int. J. Nanomed., 2015, 10, pp. 609 –631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ludwig A.: ‘The use of mucoadhesive polymers in ocular drug delivery’, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., 2005, 57, (11), pp. 1595 –1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shi S. Zhang Z. Luo Z. et al.: ‘Chitosan grafted methoxy poly (ethylene glycol)‐poly (ε‐caprolactone) nanosuspension for ocular delivery of hydrophobic diclofenac’, Sci. Rep., 2015, 5, p. 11337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lehr C.M. Bouwstra J.A. Schacht E.H. et al.: ‘In vitro evaluation of mucoadhesive properties of chitosan and other natural polymers’, Int. J. Pharm., 1992, 78, pp. 43 –48 [Google Scholar]

- 65. De Campos A.M. Sanchez A. Gref R. et al.: ‘The effect of a PEG versus a chitosan coating on the interaction of drug colloidal carriers with the ocular mucosa’, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci., 2003, 20, (1), pp. 73 –81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kim H. Robinson S.B. Csaky K.G.: ‘Investigating the movement of intravitreal human serum albumin nanoparticles in the vitreous and retina’, Pharm. Res., 2009, 26, pp. 329 –337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Koo H. Moon H. Han H. et al.: ‘The movement of self‐assembled amphiphilic polymeric nanoparticles in the vitreous and retina after intravitreal injection’, Biomaterials, 2012, 33, pp. 3485 –3493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Peeters L. Sanders N.N. Braeckmans K. et al.: ‘Vitreous: a barrier to nonviral ocular gene therapy’, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci., 2005, 46, pp. 3553 –3561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sanders N.N. Peeters L. Lentacker I. et al.: ‘Wanted and unwanted properties of surface PEGylated nucleic acid nanoparticles in ocular gene transfer’, J. Control Release, 2007, 122, pp. 226 –235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hamalainen K.M. Kananen K. Auriola S. et al.: ‘Characterization of paracellular and aqueous penetration routes in cornea, conjunctiva, and sclera’, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci., 1997, 38, (3), pp. 627 –634 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Xu Q. Boylan N.J. Suk J.S. et al.: ‘Nanoparticle diffusion in, and microrheology of, the bovine vitreous ex vivo’, J. Control Release, 2013, 167, (1), pp. 76 –84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Otsuka H. Nagasaki Y. Kataoka K.: ‘PEGylated nanoparticles for biological and pharmaceutical applications’, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., 2003, 55, pp. 403 –419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Thorpe R.M. Kolker A.E.: ‘A tonographic study of water loading in rabbits’, Arch. Ophthalmol., 1967, 77, pp. 238 –243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bonomi L. Tomazzoli L. Jaria D.: ‘An improved model of experimentally induced ocular hypertension in the rabbit’, Invest. Ophthalmol., 1976, 15, pp. 781 –784 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sears D. Sears M.: ‘Blood‐aqueous barrier and alpha‐chymotrypsin glaucoma in rabbits’, Am. J. Ophthalmol., 1974, 77, (3), pp. 378 –383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Orihashi M. Shima Y. Tsuneki H. et al.: ‘Potent reduction of intraocular pressure by nipradilol plus latanoprost in ocular hypertensive rabbits’, Biol. Pharm. Bull., 2005, 28, (1), pp. 65 –68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Muslim T. Morimoto M. Saimoto H. et al.: ‘Synthesis and bioactivities of poly (ethylene glycol)‐chitosan hybrids’, Carbohydr. Polym., 2001, 46, pp. 323 –330 [Google Scholar]