Abstract

Considering that parents are one of the key figures in their child’s participation in physical activity, it is extremely important to examine parents’ perceptions and experiences of physical activity in order to protect children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) from the inactive life during the novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak and to include them in physical activities in the home environment. Although it is still a new subject, there is no research that addresses parents’ physical activity knowledge, needs and recommendations for the physical activity experiences of children with ASD during the COVID-19 outbreak, and offers solutions accordingly. Considering this gap in the literature, the aim of this qualitative study is to explore parents’ perceptions on physical activity for their children with ASD. Participants of the study were 10 parents with children with ASD, who participated in one-to-one semi-structured phone calls. Interview data were analyzed thematically. The analysis of the data revealed three main themes: 1) Possible benefits of physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak, 2) Physical activity barriers during the COVID-19 outbreak, and 3) Recommendations for physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak. The results revealed that parents thought that physical activities had a positive effect on the development areas of their children with ASD. It was determined that parents want to involve their children in physical activities in the home environment, but they have barriers that they need to overcome.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorders, physical activity, parents’ perceptions, COVID-19, stay at home

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, which is rapidly spreading around the world, has now become the most important agenda of the world (Yarımkaya and Esentürk 2020). Various preventive measures have been taken by the World Health Organization (WHO) and governments of countries to prevent the disease that turns into a global pandemic. Some of these measures are people paying attention to social distance and staying at home. For instance, Turkey has taken some measures after the identification of the first national COVID-19 case on 11 March 2020. These preventive measures include reduction of public transport, closure of all schools, cancellation of arts and sports events, mandatory quarantine for the people who travelled from abroad, closure of public places such as cafes/cinemas/the mall, curfews for the citizens over 65, under 20 and those with chronic illnesses. With the increasing number of COVID-19 cases, curfews were extended in metropolitan cities, as well as intercity travel restrictions. In addition, the authorities often state that they do not go out onto the streets unless it is mandatory. Although staying at home prevents the spread of the disease, this poses a number of challenges, especially for children with special needs like Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD), and their families. The concept of ASD is expressed as a neurobiological developmental disorder characterized by social interaction, verbal and non-verbal communication, limited and repetitive interests and behavioral patterns (American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2013). ASD has effects that have a great deal of behavioral, cognitive and mental functions on individuals with this diagnosis (Newschaffer et al. 2007). In order to eliminate these negative effects, children with ASD participate in special education practices that include physical activities on certain days of the week. However, the closure of schools due to the COVID-19 emergency caused children with special needs such as ASD and their families to experience serious educational problems (Kohli and Writer 2020). Therefore, children with ASD are deprived of their education processes (intervention programs, special education, physical therapy) that they have for their main characteristics (social interaction, communication and limited behavior patterns) that affect their quality of life. It is anticipated that this can make children with ASD vulnerable to difficulties in the COVID-19 crisis. However, the Covid 19 outbreak also led to changes in the daily routines of children with ASD. This process, which is also difficult for individuals with typical development, has unfortunately caused much more difficulties for individuals with ASD (APA 2013) who are extremely dependent on routines and are immensely sensitive to changes in the environment. These changes in the routines of children with ASD due to the COVID-19 outbreak revealed risks that could affect them from different perspectives (Narzisi 2020).

European WHO (EWHO) recommends physical activity and relaxation techniques to protect individuals from possible risks to physical health, quality of life and mental health and to remain calm due to sedentary life and low physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak (EWHO 2020). Physical activity is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure ( WHO 2008). Participation in physical activities can provide a number of advantages for children with ASD in terms of physical and mental health (Healy et al. 2018; Lang et al. 2010; Petrus et al. 2008). Studies examining physical activities in children with ASD (Lalonde et al. 2014; Lochbaum and Crews 2003; Menear and Neumeier 2015; Sowa and Meulenbroek 2012) revealed that physical activities can have a positive effect on the manipulative skills, locomotor skills and skill-related fitness of children with ASD. In addition, studies have suggested that physical activities can help improve the self-confidence and self-efficacy of children with ASD (Lang et al. 2010; Sowa and Meulenbroek 2012). Participation in physical activity can also contribute to reducing the stress and anxiety levels of individuals with ASD (Hillier et al. 2011). Regarding the basic characteristics of children with ASD, participation in physical activities can improve the social behavior (Gregor et al. 2018) and communication skills of children with ASD (Yarımkaya et al. 2017), and reduce self-stimulating/self-injurious behavior (Sorensen and Zarrett 2014).

Despite the numerous health and social benefits of regular physical activity, children with ASD are said to have less physical activity levels than their normally developing peers (Corvey et al. 2016; Pan et al. 2016). It has been suggested that there are many possible barriers in children with ASD that lead to a lack of physical activity (Healy et al. 2018). To explain barriers that cause physical activity deficiencies of children with ASD, some studies focus on below-optimal motor skills and fitness (joint flexibility, balance, speed etc.), bio-physical behaviors (carelessness/hyperactivity) and communication disorders, which are characteristic features of ASD (Bandini et al. 2013; MacDonald et al. 2011; Pan and Frey 2006). While examining the physical activity deficiencies of children with ASD, some studies draw attention to the barriers reported by parents (child’s need for supervision, parental time restrictions, behavioral problems, etc.) (Healy et al. 2013; Must et al. 2015; Obrusnikova and Cavalier 2011). Considering that parents are one of the main factors for children to participate in physical activity (Baranowski 1997; Sallis et al. 2000), researchers emphasize the importance of parents knowing physical activity values, knowledge and preferences in order to provide a better physical activity experience to children with ASD (Gregor et al. 2018).

As can be seen in the literature, research investigating barriers to the participation of children with ASD from the parents’ perspective has been carried out in the absence of any outbreak or abnormal condition. However, in recent days, a COVID-19 outbreak has emerged as a possible barrier for children with ASD that can lead to a lack of physical activity. Children with ASD faced risk of low level of physical activity due to the sedentary lifestyle, closed training centers and often inappropriate online learning environments during the COVID-19 crisis. Although it is still a new subject, there is no research that addresses parents’ physical activity knowledge, needs and recommendations for the physical activity experiences of children with ASD during the COVID-19 outbreak, and offers solutions accordingly. Considering this gap in the literature, the aim of this qualitative study is to explore parents’ perceptions on physical activity for their children with ASD. In line with the interviews with parents, the study focused on parental perspectives on factors that increase or decrease the physical activity experiences of children with ASD during the COVID-19 outbreak. This study aimed to answer the following research questions:

What are parents’ perceptions on the benefits of physical activity for their children with ASD?

What are parents’ perceptions on the barriers to physical activity for their children with ASD?

What support do parents need to include their child with ASD in physical activities?

Methods

Study design

In this study, a descriptive qualitative methodology was used to examine the perceptions on parents in Turkey on the participation of their children with ASD in physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak. Descriptive qualitative methodology is the interpretative way of study that forms the basis of a thorough understanding of a phenomenon (Creswell 2009) and provides insight into perspectives and life experiences of participants (Sandelowski 2000). This research model often gives insight into how individuals experience the social world and it can be a valuable resource in areas, which have not been adequately researched and do not have an experimental or theoretical basis on scientific grounds. As a matter of fact, considering that we are at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, it is seen that there are not enough studies on children with ASD in the quarantine process. Therefore, it is foreseen that the use of a descriptive qualitative methodology can contribute to the preparation of a conceptual infrastructure in this field.

Participants

Criterion sampling, which is one of the purposeful sampling methods, was used to determine the possible participants of the study. The criterion sampling model includes the selection of participants according to the predefined criteria in line with the aim of the study (Creswell 2009; Merriam 2015). The criteria in the study were determined as follows: a) accepting to participate in the study voluntarily, b) having a child diagnosed with ASD according to DSM-5 criteria, and c) accepting to conduct interviews on the phone. A total of 10 parents (6 mothers, 4 fathers) living in Erzincan, one of the cities in the eastern region of Turkey, participated in the study in line with the determined criteria. The aim and participation process of the study by the primary researcher was explained to the parents on the phone. Then, parents filled out consent forms via email and it was planned when to make phone calls with each parent. Parents who participated in the study were between 35 and 54 years old and their children were between 9 and 16 years old (see Table 1). All parents stated that their children participated in physical activities at school, special education center or hospital before the COVID-19 crisis. Given the decisive roles of parents in the participation of their children in physical activity (Sallis et al. 2000), parents were selected as the study group for this study, which examined the physical activity participation of children with ASD during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Parents |

|

Children |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of parent | Gender | Age | Perceived income | Education | Gender | Age | Diagnosis | Additional Comorbidities | |

| Ali | Male | 54 | Middle | University | Male | 14 | ASD | ID | |

| Ayşe | Female | 48 | High | University | Female | 16 | ASD | ID, Asthma | |

| Kadir | Male | 51 | Middle | High School | Female | 15 | ASD | ADHD | |

| Aslı | Female | 39 | Middle | University | Male | 12 | ASD | ID | |

| Hakan | Male | 36 | Middle | High School | Male | 11 | ASD | N | |

| Seray | Female | 37 | Middle | High School | Male | 11 | ASD | ID | |

| Ceren | Female | 35 | Middle | University | Female | 10 | ASD | ADD | |

| Gökhan | Male | 37 | Middle | University | Male | 12 | ASD | N | |

| Berna | Female | 41 | Middle | High School | Female | 11 | ASD | ADHD | |

| Kader | Female | 43 | Middle | University | Female | 9 | ASD | ID | |

Note: All names are pseudonyms. ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorders; ID: Intellectual Disability; ADHD; Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: N: None.

Whether the number of participants in the research was sufficient or not was decided by data saturation. Guest, Bunce and Johnson (2006) stated that data saturation can be achieved by 6 interviews depending on the sample size of the population. Thus, interviews were conducted with 10 parents in the research. In addition, frequent repetition of parental opinions and the inability to create more new themes and sub-themes were seen as evidence of very high saturation.

In the study, it was determined that children with ASD may have additional comorbidities. Five children with ASD were also found to have mental disabilities. In addition, while Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder was detected in 3 children with ASD, it was seen that one child has Asthma and two children have no comorbidities.

Data collection

In the study, personal information forms and semi-structured interview forms were used to collect data. Demographic information about parents (gender, age, income level and educational background) and their children (gender, age and diagnosis) were collected with the personal information form. With the semi-structured interview form, the parents’ perceptions about the participation of their children with ASD in physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak were examined. Qualitative interviewing is one of the qualitative data collection tools used to determine individuals’ experiences, knowledge, attitudes and feelings through open-ended questions (Fraenkel et al. 2012; Lodico et al. 2010; Patton 2014). In the preparation of the interview questions, the relevant literature was examined and draft questions were created that could reveal the participants’ perceptions about the participation of their children with ASD in physical activity. For the content validity of the draft questions, opinions were received from five experts (2 Professors, 1 Associate Professor, and 2 Dr. Lecturer) who have many publications in the fields of adapted physical activity, physical education pedagogy and qualitative study. According to the feedback from the experts, the interview form was finalized (see Table 2). Later, interview questions were directly applied to a similar parent to the participants considered to be applied, and were tested with a pilot study for clarity. All the interviews conducted in the study were made on the basis of the phone, as required by the social distance proposed by WHO. Each interview lasted approximately 20-25 min. In addition, sound was recorded for all interviews. Every effort was made to make the participants feel comfortable.

Table 2.

Sample interview questions.

| Sample interview questions |

|---|

| 1- What do you think about the importance of physical activities and the importance of physical activity in your child's life? |

| How many hours a day would your child spend on physical activities before the COVID-19 outbreak? How many now? How many meals a day would your child eat before the COVID-19 outbreak? How many now? How can the participation in physical activities during the COVID-19 crisis affect your child positively or negatively? |

| 2- What are the barriers to your child's participation in physical activities during the COVID-19 outbreak, can you explain them? |

| 3- What kind of support do you need to ensure your child continues to participate in physical activity during the COVID-19 epidemic? |

Data analysis

In the study, thematic analysis method was used to analyze the data obtained from the participants. According to Liamputtong (2009), thematic analysis is the process of establishing a thematic framework for analysis and defining the data in the light of this framework, investigating the cause-effect relationship between the findings based on the data identified and interpreting the observed relations by the researcher. In this type of analysis, the process begins within the framework of defined or possible themes. However, the analysis process that starts with the existing themes continues with the creation of new themes (Merriam 2015). In the analysis of the study data, first of all, the sound recordings collected from the participants through interviews were converted into writing. Then primary and secondary researchers independently read and analyzed the data many times. Then, the researchers came together to discuss whether the themes and sub-themes created were appropriate. After each interview completed in this analysis process, the above processes were repeated and similar sub-themes were combined and new themes were created. After analyzing the data obtained from all participants, the determined themes and sub-themes were presented to the opinions of a specialist not included in the study.

Results

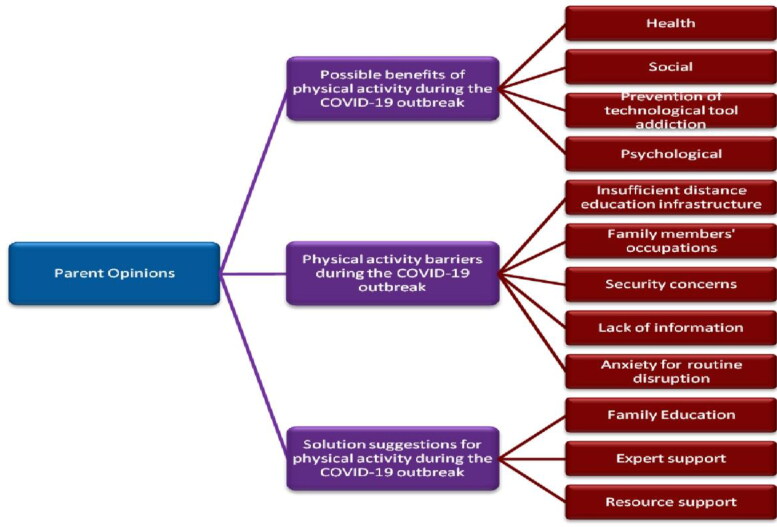

In the study, three themes were reached by analyzing the data collected from the parents: possible benefits of physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak, physical activity barriers during the COVID-19 outbreak, and solution suggestions for physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak. Within the scope of the theme of possible benefits of physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak, four sub-themes were obtained: health, social, psychological and prevention of technological tool addiction. Under the theme of physical activity barriers during the COVID-19 outbreak, there were five sub-themes: family members’ occupations, safety concerns, insufficient distance education infrastructure, anxiety for routine disruption and lack of knowledge. In the theme of solution suggestions for physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak, three sub-themes were identified: family education, expert support and resource support (book, brochure, handbook, etc.) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summaries of the themes and sub-themes.

Theme 1: possible benefits of physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak

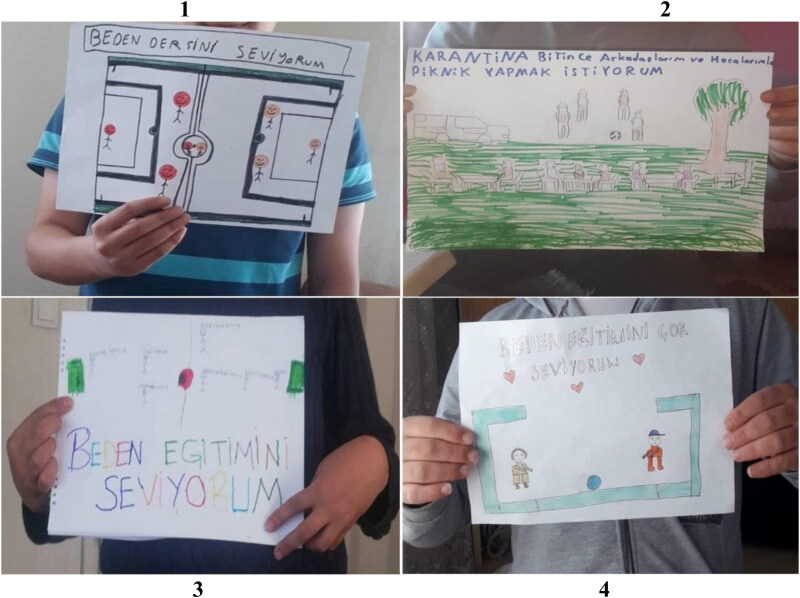

Parents stated that their children with ASD are very happy to participate in physical activities based on physical education, sports and games, and that their children with ASD participate excitedly and eagerly, especially in outdoor physical activities (garden, park, etc.). However, the parents stated that they faced some problems (closed education centers, curfew etc.) that they did not experience in normal daily life during the outbreak, and therefore their children could not participate in physical activities. Parents said that their children with ASD are upset about this situation, they occasionally ask when they will participate in physical activities, and that in their pictures, they include drawings that reflect their desire to participate in physical activity (see Figure 2). In Figure 2, it was seen that children with ASD want to participate in outdoor physical activities (football, rope jumping, walking etc.) rather than in the home environment. This situation is thought to reflect the physical activity preferences of children with ASD, who have to stay at home due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Figure 2.

Pictures of children with ASD for physical activity requests (They say they like physical education).

1: He says “I like physical education classes”; 2: He says “When the quarantine process is over, I want to have a picnic with my friends and teachers; 3: He says “I like physical education course”; 4: He says “I like physical education course very much”

Parents stated that physical activity levels of their children with ASD should always be increased, taking into account their interest in physical activity. They frequently addressed the benefits of physical activity in eliminating the problems that may arise as a result of long-term stay in the quarantine process. Parents reported positive opinions about the potential benefits of physical activity, primarily health, social and psychological aspects. Therefore, this theme includes the benefits provided by physical activity to children with ASD during the COVID-19 outbreak, according to parental opinions.

Health

In the study, parents expressed a lot of opinion on the contribution of physical activity to the health aspect of children with ASD. In particular, the parents stated that their children had a lot of problems due to weight control during the quarantine process. They mentioned the importance of physical activity in controlling weight and reducing the risk of obesity. Ali’s opinion on this matter is as follows:

“My child normally eats a lot of food. However, when he goes to special education or sports, he spends a little time at home. So he doesn’t have the opportunity to eat much. But we are in quarantine right now, we are always at home. He wants to eat all the time. The only thing that will prevent this is that he moves”.

Parents generally stated that physical activity will contribute to their children with ASD in terms of weight control. However, in some parents’ opinions, body posture disorder due to constant sitting and standing still was mentioned. Ayşe’s opinion on this matter is as follows:

“I have my daughter doing gymnastics with shadow teacher (teacher for students with special needs), but now we are living in a time where no one can come home, I would watch them with different eyes if I knew this would happen. After the gym class, my daughter started walking more smoothly and she was moving upright. In this process, I want to get her make these movements as much as I can to protect her body posture”.

Social

In the study, parents stated that physical activity contributes significantly to the social skills of children with ASD. It was stated that this group, which also shows great deficiencies in social skills apart from the quarantine process, exhibits more asocial features with this process. It was found that the common anxiety that parents have towards their children is that their children may go back socially after the quarantine process. Parents stated that physical activity has an important role in removing such anxieties. It was stated that through physical activities, family-child interactions become more efficient, children are more compliant, house rules are more complied with and positive contributions are made to the social development of children with ASD like increased quality time. Almost all of the parents whose opinions were consulted emphasized the relationship between physical activity and social skill development. Example parental opinions are as follows:

“…One of the things that I know best is that physical activity is very good for my son, and the moments when he communicates best with me are the moments when we play games” (Kadir).

“Whatever activity we do at home right now, there is no quality time as much as physical action” (Hakan).

“In this process, we had to work from home and bring work to the home. Both my wife and I work, the time we devote to him has decreased because we get tired. And he is making many objections to us at this time. When we play a match with him, when he shoots with a ball or when we play while he sits on my back, harmony between us increases after the activity is over” (Hakan).

During the interviews, the parents stated that their children could interact online only with their families and relatives during the quarantine period. However, parents stated that they had the opportunity to interact with many characters with the virtual world created by physical activities. A parental opinion regarding this situation is as follows:

“We always watched women’s volleyball with my son. And we even learned their names. In this process, this situation relieves us. Even for a while, he gets his attention. We stretched a rope between the two chairs and we congratulate each other by playing with the names of the players, we joke, we object to our referee father, we feel like as if it has created another environment for us” (Aslı).

Decrease in technological tool addiction

During the interviews with parents, it was stated that the most controversial issue in the quarantine process was experienced in the use of technological devices such as mobile phones, tablets etc. It was stated that at times other than quarantine, their daily occupations reduce leisure time at home and limit the use of technological tools. However, it was reflected in the opinions of the parents that the quarantine process created by the outbreak disease spread the use of technological tools. In addition, according to the parents’ opinions, it was argued that physical activities in the home environment can replace technological tools. A parental opinion supporting this situation is given below:

“He spends so much time on the tablet at home, shouts if I take it from him and cries for minutes. Especially after the activities with the ball, he forgets the tablet and tries to say that he wants to take the ball and play” (Seray).

Psychological

During the interviews, parents expressed a large number of opinions on the contribution of physical activity to the psychological dimension. Especially, t was determined that the level of conflict increased between parents and their children during the quarantine process. Parents stated that they provide the most suitable environment for their children to discharge their energy with physical activities. Selen stated that physical activity is a tool for psychological relaxation in children with ASD with her opinions on this issue “their duration of staying at home has increased, their movements have been limited and they have to spend their energy somehow. I think the most suitable are physical activities that relax my daughter and help her to be calmer at the end”. In addition, as a result of other parents’ opinions, they stated that through physical activity, their children become more compatible, they are open to learning, their stress and anxiety levels decrease and their problem behaviors decrease. Similarly, Rüya interpreted the contribution of physical activity to the psychological characteristics of children with ASD as “very important (physical activity)”. In addition, Ceren emphasized the integrative aspect of physical activity and expressed their sense of comfort as follows:

“Physical activity is the only way to get us all together in one room. I always think while watching TV or surfing on computer that if we were at normal times, my child would be in education right now. And the feeling to make him do something engages my attention and it drives me crazy to think that he will regress. Physical activity is both easiest for me and something that makes us very comfortable”.

Theme 2: physical activity barriers during the COVID-19 outbreak

Although all the parents interviewed in the study stated that their children’s physical activity level should be increased, they mentioned some of the barriers experienced in COVID-19. With the addition of the stay at home process to the situations that prevent participation in pre-outbreak physical activity, different problems have emerged. By analyzing the data obtained from the parents, the theme of physical activity barriers during the COVID-19 outbreak was obtained. Under this theme, five sub-themes were included: family member occupations, safety concerns, insufficient distance education infrastructure, anxiety for routine disruption and lack of knowledge.

Occupation of family members

Some parents stated that they switched to the home work system in accordance with the measures taken in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. They stated that the process of working from home reduced the time they devote to their children with ASD both qualitatively and quantitatively. Gökhan stated this situation as follows:

“During the outbreak, many people lost their jobs, we are lucky, we work from home. In normal times, we used to do movements with my son for almost 1 hour a day, and he got used to do that. I cannot explain why we are in quarantine, nor can I explain why I work from home. When he comes to me with a ball in his hand, I can’t spare time for him as much as I want and we can’t have a good fun time”.

Some of the parents also stated that they also had children without additional support needs and that they also had to take care of them during the quarantine process. Berna expressed with the following statements the fact of they always had to deal with such a situation, but a bigger problem emerged in the quarantine process:

“Since we are in quarantine, we must have two separate parent characteristics. For example, I have to be mother to my daughter and to my son separately. It is very difficult for me to engage both of them in physical activity at home at the same time, because one likes the ball while the other wants to roll over, jump”.

During the interviews, the parents said that they had some financial losses during the outbreak and that such thoughts engage constantly their attention. Kadir expressed the reflection of his financial concerns on physical activities with his child as “I can never abandon myself to practices”.

Security concerns

Parents stated in the interviews that the home environment is not suitable for participating in physical activities, and therefore they could not apply them during the quarantine process because of the concern that their children could be harmed. Although it appeared as the least repeated opinion by parents in the interviews, it was seen as an element that prevented children with ASD from participating in physical activities. Kader explained this situation and what she meant by the concept of security as follows:

“We are in quarantine, at home; houses can only allow simple games. It is because we have many items to break and topple over. These items can harm the child in movements”.

Insufficient distance education infrastructure

As a result of the interviews, all parents stated that the system developed by the Ministry of National Education and implemented as a distance education model (Education Information Network: EBA) in the quarantine process can also help families with children with special needs like ASD. Thanks to the EBA in Turkey, millions of students do not lag behind in distance education. However, the concerns of the families on this issue showed that their concerns are on the principle of working, not on the system itself. Ayşe expressed her concern on this issue as follows:

“We’re at home right now; we don’t know how long it will last. My other daughter follows her classes and does her homework on EBA. But my daughter with additional support needs shouldn’t be deprived of them. Families like us must also be considered by the state. The only thing I’m afraid of is that the skills we have provided to my child have been regressed so far, but I think that this should change: video should not be prepared for children with ASD, video that educates families should be prepared so that I can get my daughter doing physical activity correctly”.

Anxiety for routine disruption

Parents stated that they were anxious to have their children perform physical activity during the quarantine process, worrying that their children’s routines might be disrupted. In other words, it was a habit for children to do physical activity outside the home. Parents stated that after the quarantine process is over, their children can see physical activity at home as a routine and the education they receive outside the home may be disrupted. A parental opinion that emphasizes this situation is as follows:

“For my son, the house is a place to rest, eat and sleep while outdoor environments are a place to play, move, and walk. These have now gained a seat in him. I think this process will take a long time and life will not easily return to normal. These ideas prevent me from doing activities that would disrupt home routine” (Hakan).

Lack of knowledge

In the study, some parents stated that if they had sufficient knowledge, they would have the opportunity to offer much more physical activity to their children. Parents stated that they were particularly afraid of injury and wrong movements and were reluctant to practice because they did not know which movement operated which region. A parent briefly explained this situation with the phrase “make matters worse while trying to be helpful”. At this point, parents who saw the lack of knowledge as an obstacle to the opportunity to offer physical activity to their children argued that this deficit should be met.

“Let’s say we have started the game and the move, done 10 seconds, then 30 seconds, well, I don’t know how much more we will do next. I will make him run in the house to lose weight, but how long will this be, should he stop if he sweats, I don’t know this things” (Kadir).

Some parents stated that their child had challenging behaviour issues and did not know how to prepare appropriate physical activities. A parental opinion summarizing this situation is presented below:

“My son gets very angry and shouts so badly when he loses; I do not know how to prepare an activity for this child. I would go to the park or go down to the garden if there was no quarantine, but I really have no idea how to get the physical activity done at home” (Seray).

Theme 3: solution suggestions for physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak

During the interviews with parents, some solutions were offered to increase the physical activity levels of children in the quarantine process. Within the scope of this theme, three sub-themes are identified: Family education, Expert support and Resource support (Book, brochure, handbook etc.).

Family education

During the interviews, parents stated that they wanted to receive education by specialist educators during the quarantine process. It was determined that especially parents who have children with special needs like ASD want to learn how to behave in application processes as well as getting the knowledge about physical activity. Families, who lead an isolated lifestyle in the quarantine process, think that they can overcome this process more easily with the trainings to be held. A parent who advocates that family education can be done easily through national channels and the Internet expressed her opinion on this issue as follows:

“I think it shouldn’t be too hard, if we should have physical activity for our children without leaving home, then there are many channels and internet for this. Both families and children will relieve if they train us well” (Berna).

Expert support

Parents think that they can make a lot of mistakes by watching videos on their own. Therefore, they stated that there is a need for expert support in physical activity. A parental opinion on this matter is as follows:

“I am a textile consultant in a private company. Even though I work from home, my phone rings 100 times a day and everyone can consult me since I am an expert. The state can establish such a system and guide me on how to make my child do movements in quarantine” (Aslı).

Resource support

Parents stated that with the start of the outbreak-related quarantine process in other countries, Turkey should begin resource preparation for children with special needs like ASD. It is stated that one of these sources should be about physical activities that directly contribute to all areas of development of children with ASD. The opinion of a parent, who argues that resources related to physical activity for children with special needs remain in the background due to medical priorities, is as follows:

“Perhaps it would be possible to see this outbreak in other countries and start resource preparation, but health was outweighed and such preparations could not be made to prevent deaths. In all advertisements, it is said that children should do physical activity, but how to make them do it is not explained especially for families like us” (Kader).

Considering the findings obtained according to the parents’ opinions, it was determined that after the COVID-19 outbreak, children with ASD spend more time at home, they can do less physical activity compared to normal times, their levels of inactivity has increased, their interest in technological devices has increased, their diet is impaired and they tend to gain weight. Therefore, the parents stated that the development aspects of their children were negatively affected in the quarantine process that occurred after the epidemic. Parents specified that with the addition of the quarantine process to situations that prevent participation in pre-epidemic physical activity, different problems have arisen.

Discussion

This article is the first study to examine the perceptions of parents who have children with ASD in the quarantine process due to the COVID-19 outbreak. In the current precarious environment where it is not known how long the quarantine process will continue, this study will contribute significantly to the understanding of how physical activity is perceived among parents who have children with ASD. In the interviews conducted in the study, it was determined that parents who have children with ASD have awareness of the positive effects of physical activities and they strive to increase the physical activity level of their children. In addition, parents’ opinions showed that physical activity provides significant benefits to children with ASD during the quarantine process. However, in interviews with parents, findings related to the factors preventing their children with ASD from participating in physical activity were reached and solution suggestions were developed to eliminate these factors. Since there is no literature regarding the quarantine process in the discussion of the findings obtained in this study, the results of the research in the normal process were used. Although the quarantine process has created a different subject area alone, it is considered that the evaluations to be made according to the results of the research under normal conditions are important. In addition, in the study, the possible contribution of physical activity to the development levels of children with ASD was examined within the framework of the quarantine process according to parental opinions, and these opinions were compared with the findings of normal time. This section was created using the themes reached as a result of interviews with parents.

Theme 1: possible benefits of physical activity in the COVID-19 process

In the study, parents stated that physical activities to be performed during the COVID-19 outbreak may have a positive effect on the development areas of their children with ASD. Parents also mentioned the importance of physical activity, especially in controlling weight and reducing the risk of obesity. Considering that a sedentary lifestyle has increased in the quarantine process, it is not surprising that parents expressed this opinion. There are research results in the literature that support or reject the results of this research. For example, studies by An and Goodwin (2007), Columna et al. (2011), and Perkins et al. (2013) revealed that parents who have children with special needs are aware of the positive contribution of physical activities to the health aspect. On the other hand, studies conducted among families of Spanish disabled children in the United States (Columna et al. 2008) and Guatemala (Columna et al. 2013) revealed that Spanish families are unaware of the health benefits of physical activities, and that parents focus on the physical and psychological benefits of being active.

In the study, parents stated that physical activities to be performed in the quarantine process can contribute to the social and psychological development of their children with ASD. Social isolation measures have been taken in accordance with the quarantine process due to the COVID-19 outbreak. In this context, there is only an interaction between family members in the home environment, and the relationships with friends and relatives are established through internet-based applications. It was stated that this situation negatively affects the social development of children with ASD and causes an increase in their stress and anxiety levels. It was stated that increased stress and anxiety level increased children’s problem behaviors. It was determined that parents think that family-child interactions become efficient, children with ASD are more compliant and house rules are more followed through physical activities. According to parents, quality time spent through physical activities supports the social development of their children with ASD and contributes to decrease in their levels of stress, anxiety and behavioral problems. It was revealed in the research by Columna et al. (2008) that parents stated that their children made new friends through physical activities and their socialization levels increased. Similarly, Shapiro et al. (2005) and Goodwin et al. (2011) reveal that children with special needs felt more competent and their feelings of social acceptance developed after the summer sports camp. Sorensen and Zarrett (2014) reported that the social skills and communication skills of children with ASD who participated in physical activities increased. Moreover, in a study by Hillier et al. (2011), it was found that the level of stress and anxiety decreased significantly in children with ASD who participated in physical activity. In this process, where social distance is maintained with other people, the positive effect of physical activities that can be performed in a quarantine environment on the social and psychological skills of children with ASD can be explained by the increased and stronger family interaction and increased compliance with home rules through physical activities.

The COVID-19 outbreak has made the use of internet-based electronic devices very common around the world. As a result of social isolation, all needs, especially shopping, have been met on the Internet. In the quarantine process, apart from basic needs, playing games, reading books and watching movies have become daily routines. Therefore, the increase in the time spent at home significantly increased the time spent with technological tools. Parents stated that in the quarantine process, children with ASD are glued to the technological tools (tablet, computer, phone, etc.), which they spend a lot of time even in the normal period. Parents who stated that they managed to attract the attention of their children with ASD through physical activities, argued that physical activities in the home environment can replace technological tools. Thus, the parents stated that the issue of the most important discussion and unrest in their homes decreased.

Theme 2: physical activity barriers in the COVID-19 process

All parents interviewed in the study stated that although they had the desire to include their children with ASD in the physical activity during the quarantine process, they faced some barriers. The quarantine process, especially from the outbreak of COVID-19, has created some unique barriers. One of these barriers is the insufficient distance education infrastructure. Parents stated that the institutions in which they received education were closed in this process and that physical activities should be continued through distance education. Parents who have children with normal development also stated that the educational infrastructure offered to them throughout the country should be offered to other children with ASD. It is thought that this finding, which is needed in the normal life cycle to a certain extent, will shed light on the potential barriers that children with ASD can experience during the quarantine process.

Each parent may have their own personal priorities, basic routines, or occupations that they consider to take precedence over physical activity. Particularly, the parents who are included in the system of working at home during the quarantine process stated that they mostly experienced these occupations. Therefore, the parents stated that their workload increased and this was an obstacle to their children’s participation in physical activities. In the studies conducted (Njelesani et al. 2015; Perkins et al. 2013; Schleien et al. 2014), parents who have children with special needs stated that their personal priorities are a barrier to their children’s participation in physical activity.

In the study, some parents expressed their safety concerns as a factor limiting their children’s participation in physical activity during the quarantine process. Parents who stated that the home environment is not suitable for physical activities, in particular, stated that the objects to be broken and toppled can harm their children. In some studies (Columna et al. 2011; Schleien et al. 2014), it was seen that parents associated the inability of their children with special needs to participate in physical activity for architectural reasons.

In the study, parents stated that if they had sufficient knowledge, they would have the opportunity to offer their children much more physical activity. When parental opinions, which may differ according to demographic variables, are examined, the lack of knowledge in almost all participants is stated as a barrier. Parents stated that they do not have the knowledge to support and increase the physical activity level of their children with ASD, and they lack knowledge about how intensely, how long and how often they will apply physical activities to their children with ASD. Parents, who thought that they had a more limited environment and resource shortage during the quarantine process, said that their knowledge level was not sufficient to overcome this issue. In the study by Lieberman et al. (2002), it was determined that the lack of knowledge experienced by the parents about the application of physical activity led to the perception that their children could be injured and the practices would not contribute to their children.

Theme 3: solution suggestions for physical activity during the COVID-19 outbreak

Parents who participated in the study have offered some solution suggestions to overcome the barriers they encounter while including their children with ASD in physical activities. Considering that the society has not experienced such a quarantine process for a long time, it is an undeniable fact that the solution suggestions expressed by the parents should be taken into consideration. In the study, parents stated that they need family education in order to pass the quarantine process in the most efficient way in terms of physical activity level of their children with ASD. In line with the intervention programs offered to children with special needs, the importance of this recommendation will be understood, considering that the goals set for both the child and the family cannot be achieved without the active participation of parents (Diken 2009; Sameroff and Fiese 2000). Parents stated that the quarantine process created an environment of uncertainty for them, which increased their anxiety levels. Therefore, it was stated that in such an outbreak environment, especially parents who have children with special needs need family education. In the study, parents stated that they need expert and resource support in order to actively include their children with ASD in physical activities. Regardless of the quarantine process, parents said that they did not receive adequate support to offer their children appropriate physical activities, even under normal circumstances. However, some parents stated that they did not rely on physical education teachers, who they considered as experts to increase their children’s physical activity levels.

Limitations of the study

Since the study includes a sample of 10 parents, the transferability of the obtained results to the perceptions of other parents may be limited. In addition, the results obtained in the research are limited to the perceptions of parents who have children with ASD with or without additional support needs. The results may not represent the whole country since all participants live in Erzincan.

Implications for practice and future research

Considering the increasing spread rate of COVID-19, quarantine rules must be followed to control the outbreak. Furthermore, attention should be paid to the effects of sedentary life caused by prolonged stay at home ( Chen et al. 2020). A sedentary life and low physical activity level during the COVID-19 outbreak can have adverse effects, especially on the health and quality of life of children with ASD. Staying at home can also turn into a source of stress for these children, leading to a number of problems with mental health (Yarimkaya and Esentürk 2020).

The findings provided important information regarding the participation of children with ASD in physical activity from the perspective of parents in Turkey during the quarantine process. As a matter of fact, until this date, the studies investigating the perceptions of parents on the participation of children with ASD in physical activity have been carried out in the absence of any outbreak disease or abnormal condition. Therefore, considering the uncertainty of how long the quarantine measure will last, it is anticipated that this study will make significant contributions to the relevant literature. In the study, it was seen that parents brought various solutions to overcome the barriers they encounter during the quarantine process. It is thought that future research should be planned by taking into consideration the barriers and solution suggestions stated in the current research. As a result, it was observed that parents were aware of the positive contributions of physical activity on the development of their children with ASD and made efforts to increase the physical activity level of their children. However, it was determined that the parents encountered many barriers in an extraordinary situation like quarantine and brought different solutions for the removal of these barriers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- An, J. and Goodwin, D. L.. 2007. Physical education for students with spina bifida: mothers' perspectives. Adapted physical activity quarterly, 24, 38–58. 10.1123/apaq.24.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandini, L. G., Gleason, J., Curtin, C., Lividini, K., Anderson, S. E., Cermak, S. A., Maslin, M. and Must, A.. 2013. Comparison of physical activity between children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children. Autism, 17, 44–54. 10.1177/1362361312437416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski, T. 1997. Families and health actions. In: Gochman D. S. (Ed.). Handbook of health behavior research I: Personal and social determinants. New York: Plenum Press, pp.179–206. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P., Mao, L., Nassis, G. P., Harmer, P., Ainsworth, B. E. and Li, F.. 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): The need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. Journal of Sport and Health Science, J. Sport Health Sci., 9, 103–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.02.001. 32099716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Columna, L., Fernandez-Vivo, M., Lieberman, L. and Arndt, K.. 2013. Physical recreation constraints among Guatemalan families with children with visual impairments. The Global Journal of Health and Physical Education Pedagogy, 2, 205–220. Available at: <http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1113&context=pes_facpub> [Accessed 3 March 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Columna, L., Pyfer, J. and Senne, T. A.. 2011. Physical recreation among immigrant Hispanic families with children with disabilities. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 45, 214–233. Available at: <http://js.sagamorepub.com/trj/article/view/2228> [Accessed 3 March 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Columna, L., Pyfer, J., Senne, T. A., Velez, L., Bridenthrall, N. and Canabal, M. Y.. 2008. Parental expectations of adapted physical educators: A Hispanic perspective. Adapted physical activity quarterly : APAQ, 25, 228–246. 10.1123/apaq.25.3.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corvey, K., Menear, K. S., Preskitt, J., Goldfarb, S. and Menachemi, N.. 2016. Obesity, physical activity and sedentary behaviors in children with an autism spectrum disorder. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20, 466–476. 10.1007/s10995-015-1844-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. 2009. Research design: Qualitative and mixed methods approaches. London and Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Diken, I. H. 2009. Turkish mothers’ self-efficacy beliefs and styles of interactions with their children with language delays. Early Child Development and Care, 179, 425–436. 10.1080/03004430701200478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- European World Health Organization. 2020. Stay physically active during self-quarantine. Available at: <http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-COVID-19/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-technical-guidance/stay-physically-active-during-self-quarantine> [Accessed 7 March 2020].

- Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E. and Hyun, H. H.. 2012. How to design and evaluate research in education. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, D. L., Lieberman, L. J., Johnston, K. and Leo, J.. 2011. Connecting through summer camp: Youth with visual impairments find a sense of community. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 28, 40–55. 10.1123/apaq.28.1.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor, S., Bruni, N., Grkinic, P., Schwartz, L., McDonald, A., Thille, P., Gabison, S., Gibson, B. E. and Jachyra, P.. 2018. Parents’ perspectives of physical activity participation among Canadian adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 48, 53–62. 10.1016/j.rasd.2018.01.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G., Bunce, A. and Johnson, L.. 2006. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, S., Marchand, G. and Williams, E.. 2018. “I'm not in this alone” the perspective of parents mediating a physical activity intervention for their children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in developmental disabilities, 83, 160–167. 10.1016/j.ridd.2018.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy, S., Msetfi, R. and Gallagher, S.. 2013. Happy and a bit Nervous’: The experiences of children with autism in physical education. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41, 222–228. 10.1111/bld.12053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, A., Murphy, D. and Ferrara, C.. 2011. A pilot study: Short-term reduction in salivary cortisol following low level physical exercises and relaxation among adolescents and young adults on the autism spectrum. Stress and Health, 27, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, S. and Writer, S.. 2020. Students with disabilities deprived of crucial services because of coronavirus closures, 395–402. Available at: <http://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-03-25/coronavirus-school-special-education> [Accessed 6 March 2020]. 10.1002/smi.1391 [DOI]

- LaLonde, K. B., MacNeill, B. R., Eversole, L. W., Ragotzy, S. P. and Poling, A.. 2014. Increasing physical activity in young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8, 1679–1684. 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, R., Koegel, L. K., Ashbaugh, K., Regester, A., Ence, W. and Smith, W.. 2010. Physical exercise and individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 565–576. 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liamputtong, P. 2009. Qualitative research methods. South Melbourne, VIC: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, L. J., Houston-Wilson, C. and Kozub, F. M.. 2002. Perceived barriers to including students with visual impairments in general physical education. Adapted physical activity quarterly : APAQ, 19, 364–377. 10.1123/apaq.19.3.364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochbaum, M. and Crews, D.. 2003. Viability of cardiorespiratory and muscular strength programs for the adolescent with autism. Journal of Evidenced-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 8, 225–233. 10.1177/1076167503252917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lodico, M. G., Spaulding, D. T. and Voegtle, K. H.. 2010. Methods in educational research: From theory to practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, M., Esposito, P. and Ulrich, D.. 2011. The physical activity patterns of children with autism. BMC research notes, 4, 422. 10.1186/1756-0500-4-422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menear, K. S. and Neumeier, W. H.. 2015. Promoting physical activity for students with autism spectrum disorder: Barriers, benefits, and strategies for success. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 86, 43–48. 10.1080/07303084.2014.998395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. B. 2015. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey- Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Must, A., Phillips, S., Curtin, C. and Bandini, L. G.. 2015. Barriers to physical activity in children with autism spectrum disorders: Relationship to physical activity and screen time. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 12, 529–534. 10.1123/jpah.2013-0271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narzisi, A. 2020. Handle the autism spectrum condition during Coronavirus (COVID-19) stay at home period: Ten tips for helping parents and caregivers of young children. Brain Sciences, 10, 207–204. 10.3390/brainsci10040207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newschaffer, C. J., Croen, L. A., Daniels, J., Giarelli, E., Grether, J. K., Levy, S. E., Mandell, D. S., Miller, L. A., Pinto-Martin, J., Reaven, J., Reynolds, A. M., Rice, C. E., Schendel, D. and Windham, G. C.. 2007. The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Annual review of public health, 28, 235–258. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njelesani, J., Leckie, K., Drummond, J. and Cameron, D.. 2015. Parental perceptions of barriers to physical activity in children with developmental disabilities living in Trinidad and Tobago. Disability and rehabilitation, 37, 290–295. 10.3109/09638288.2014.918186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrusnikova, I. and Cavalier, A.. 2011. Perceived barriers and facilitators of participation in after school physical activity by children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 23, 195–211. 10.1007/s10882-010-9215-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C. Y. and Frey, G. C.. 2006. Physical activity patterns in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 36, 597–606. 10.1007/s10803-006-0101-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C. Y., Tsai, C. L., Chu, C. H., Sung, M. C., Ma, W. Y. and Huang, C. Y.. 2016. Objectively measured physical activity and health-related physical fitness in secondary school-aged male students with autism spectrum disorders. Physical therapy, 96, 511–520. 10.2522/ptj.20140353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Q. 2014. Nitel araştırma ve değerlendirme yöntemleri. Ankara: Pegem Akademi. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, K., Columna, L., Lieberman, L. and Bailey, J.. 2013. Parents’ perceptions of barriers and solutions for their children with visual impairments toward physical activity. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 107, 131–142. 10.1177/0145482X1310700206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrus, C., Adamson, S. R., Block, L., Einarson, S. J., Sharifnejad, M. and Harris, S. R.. 2008. Effects of exercise interventions on stereotypic behaviours in children with autism spectrum disorder. Physiotherapy Canada. Physiotherapie Canada, 60, 134–145. 10.3138/physio.60.2.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis, J. F., Prochaska, J. J. and Taylor, W. C.. 2000. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 32, 963–975. Available at: <http://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/Fulltext/2000/05000/A_review_of_correlates_of_physical_activity_of.14.aspx> [Accessed 6 March 2020] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff, A. J. and Fiese, B. H.. 2000. Transactional regulation: The developmental ecology of early intervention, handbook of early childhood intervention. In: Shonkoff J. P. & Meisels S. J., eds. Handbook of early childhood intervention. New York: Cambridge University, pp.135–159. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. 2000. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23, 334–340. Available at: <http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.461.4974&rep=rep1&type=pdf> [Accessed 8 March 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleien, S. J., Miller, K. D., Walton, G. and Pruett, S.. 2014. Parent perspectives of barriers to child participation in recreational activities. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 48, 61–73. Available at: <http://js.sagamorepub.com/trj/article/view/3656> [Accessed 7 March 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, D. R., Moffett, A., Lieberman, L. and Dummer, G. M.. 2005. Perceived competence of children with visual impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 99, 15–25. 10.1177/0145482X0509900103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, C. and Zarrett, N.. 2014. Benefits of physical activity for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1, 344–353. 10.1007/s40489-014-0027-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sowa, M. and Meulenbroek, R.. 2012. Effects of physical exercise on autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 46–57. 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2008. The world health report 2008 - Primary health care (Now more than ever ). Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: [Accessed 8 March 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Yarımkaya, E. and Esentürk, O. K.. 2020. Promoting physical activity for children with autism spectrum disorders during Coronavirus outbreak: Benefits, strategies, and examples. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 10.1080/20473869.2020.1756115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarımkaya, E., İlhan, E. L. and Karasu, N.. 2017. An investigation of the changes in the communication skills of an individual with autism spectrum disorder participating in peer mediated adapted physical activities. Ankara Üniversitesi Eğitim Bilimleri Fakültesi Özel Eğitim Dergisi, 18, 225–252. 10.21565/ozelegitimdergisi.319423 [DOI] [Google Scholar]