ABSTRACT

Eukaryotic mRNAs are modified by several chemical marks which have significant impacts on mRNA biology, gene expression, and cellular metabolism as well as on the survival and development of the whole organism. The most abundant and well-studied mRNA base modifications are m6A and ADAR RNA editing. Recent studies have also identified additional mRNA marks such as m6Am, m5C, m1A and Ψ and studied their roles. Each type of modification is deposited by a specific writer, many types of modification are recognized and interpreted by several different readers and some types of modifications can be removed by eraser enzymes. Several works have addressed the functional relationships between some of the modifications. In this review we provide an overview on the current status of research on the different types of mRNA modifications and about the crosstalk between different marks and its functional consequences.

KEYWORDS: Inosine, m6A, m6Am, m5C, m1A, pseudouridine, epitranscriptome, ADAR

Introduction

Currently, over 170 RNA modifications have been documented across all domains of life [1]; a few modifications are universal while many are specific to prokaryotes, eukaryotes or archea. Some RNAs such as rRNA and tRNA are universally highly modified, containing many different types of modification. Both rRNA and tRNA are very abundant in the cell so it has been possible to isolate sufficient quantities to identify the RNA modifications and their locations precisely. However, when investigating other heterogeneous cellular RNAs such as mRNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) or circular RNAs (cirRNAs) it is difficult to obtain sufficient quantities of the required purity to study RNA modification by classical methods such as mass spectrometry (MS) or thin layer chromatography (TLC). For these other RNAs such as mRNA and lncRNAs, we often do not know the frequencies at which modifications occur at each position. Researchers are hoping that new technical developments, such as direct nanopore sequencing of individual RNA molecules, will allow all RNA modifications to be identified, mapped and quantitated [2].

In mRNAs, adenosine is the base that can obtain the most diverse spectrum of modifications, such as m1A, Am, m6A, m6Am methylations or deamination to inosine. In addition, cytosines can be either or methylated to form m5C or m3C or deaminated to uridines. Uridines can be converted to pseudouridines (Ψ). Some of the different modification types appear to have similar roles in mRNA metabolism. It is therefore important to study the possible coregulation, cooperativity, or competition between the individual mechanisms. Here, we aim to summarize the current status of the field and point to interesting new directions of research.

m6A and inosine, two types of modification at the N6 position of the adenosine ring

In metazoans, two of the most abundant RNA modifications in mRNA both target the amino group on adenosine. These are N6-methyladenosine (m6A) and deamination of adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) editing by adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs) (for reviews [3,4]).

ADARs bind to double-stranded (ds)RNA and deaminate adenosine to inosine. Inosine forms a Watson-Crick base pair with cytosine so cDNA generated from edited RNA shows a change at the edited position from the genomic adenosine to a guanosine (G). This replacement of A in the genomic sequence by G in the cDNA is the hallmark of A-to-I editing. During translation inosine is also usually recognized as guanosine; therefore, editing in an exon can lead to recoding, i.e. a different amino acid can be inserted in the encoded protein at the edited position [5].

A-to-I editing involves two enzymes; ADAR1 and ADAR2 (for review [6]) whereas the m6A methylation involves a larger cast of players. The m6A methyltransferase complex containing METTL3, METTL14 and Wilms’ tumour associated protein (WTAP) binds single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) and methylates the A in the middle of an RRACH consensus sequence (for review [4]). The m6A methyltransferase complex is termed the ‘writer complex’. Proteins that bind to m6A and mediate its function are termed ‘reader’ proteins; they contain a well conserved YT521-B homology (YTH) domain. In mammals there are five members of the YTH family. Other RNA binding proteins can also bind to m6A, such as Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), so the list of potential interactors is extensive. Finally, m6A, unlike A-to-I editing, is a potentially reversible process; to date there are two demethylases that can remove it, fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) and alkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5). ALKBH3 demethylases tRNA [7], so it is possible that other RNA demethylases exist whose function on mRNA is currently unknown.

Both ADAR RNA editing and adenine N6-methylation occur co-transcriptionally: they are both widespread and are expected to often occur in the same transcripts. Therefore, the question arises: is there interplay between these two modifications? In this review we will discuss the few investigations of this that have been published to date and also evaluate the effects of these modifications on dsRNA structure. To elucidate the pathways where these two RNA modifications may intersect, we will focus on A-to-I editing and then examine if there is evidence for a similar outcome due to m6A modification. We have chosen this approach due to the simplicity of the A-to-I editing in comparison to the complexity of the numerous players involved in m6A modification.

m6A modification and A-to-I editing do not compete for the same adenosines

At a first glance one would predict that the enzymes that catalyse these two modifications would not compete for the same adenosine residues as they have different target RNA structure and sequence specificities; ADAR enzymes deaminate adenosines in dsRNA regions whereas methyltransferases prefer the RRACH motif in ssRNA [8]. It was shown many years ago that m6A is a slow substrate for deamination by ADAR2 and its rate is 2% of that of adenosine [9]. Therefore, these modifications are effectively mutually exclusive on an individual adenosine i.e. an individual adenosine can undergo one or other of these modifications but not both. In addition, ADARs and the m6A methyltransferase complex have incompatible preferences for the sequence context around the targeted adenosine. ADARs prefer a guanosine 3′ of the edited A and UAG in dsRNA is a favourable site for ADAR editing [10]; this preference is not compatible with the RRACH consensus for the m6A methyltransferase complex. No instance is known where the two modifications compete for the same adenosine residue.

The predominant locations of inosines and m6A in mRNAs are also different. A-to-I editing occurs primarily in introns and in the 3′UTRs of pre-mRNA [11] whereas m6A has a peak around the stop codon [12]. In human pre-mRNAs ADAR1 predominantly edits sites within head-to-head or tail-to-tail copies of Alu elements located within a 1.5 kilobases of each other that base pair to form an Alu inverted repeat (Alu IR) duplex [13] . The level of this type of promiscuous editing at any individual adenosine in the Alu inverted copy duplex is very low, approximately ≤1%. However, Alu elements are very abundant in the human genome and there are over a hundred million different editing sites in the human transcriptome [14]. Many other mammals and animals as simple as corals, also have ongoing expansions of parasitic elements like the Alu expansion in primates and have ADAR editing levels similar to humans [15], but other mammals such as mice and rats do not have such a current, ongoing repeat expansion and are exceptional, with about tenfold lower transcriptome-wide ADAR editing levels. It has been estimated that m6A is present on 0.2%–0.6% of all adenosines in mammalian transcripts [16]. ADAR2 edits specific sites within transcripts encoding proteins, many of which are CNS-expressed, ADAR2 editing can result in recoding [11]. These editing events are relatively few, only about 60 are known in mammals; however, very accurate measurements of A-to-I editing can be obtained and the editing efficiencies at these specific sites are often very high and can reach 100%. m6A, on the other hand, is enriched around stop codons, both in the coding sequence and in the 3ʹ UTRs. However, obtaining accurate measurements of the m6A modification efficiency at each site is not trivial and the methylation is also potentially reversible. One of the most popular techniques to identify m6A sites is immunoprecipitation with specific anti-m6A antibodies, followed by next-generation sequencing (MeRIP-seq) [17]. The inclusion of crosslinking with the immunoprecipitation can give individual nucleotide resolution [18]. The critical factors in this technique are the specificities of the antibodies used and the subsequent analysis. The level of m6A can vary significantly due to the influence of many competing effects.

A-to-I editing occurs in the 3ʹUTR and can effect miRNA binding [19]. In addition, m6A sites also occur in the 3ʹUTR and effect miRNAs [20]. To date there has been no study to see the effect of both modifications on miRNA binding in the 3ʹUTR.

The effect of inosine or m6A modification on RNA structure

The m6A modification has been shown to strongly destabilize dsRNA [21]. In this case, a structural clash of the m6A methyl group with the N7 hydrogen arises when the methyl group is forced to adopt the anti conformation to allow formation of the m6A:U Watson-Crick base pair in dsRNA [21]. The methyl group on m6A in the anti orientation, is energetically unfavourable compared to the usual syn confirmation of the methyl group (Fig. 1A). The m6A tends to act as a dsRNA helix terminator, rather like proline does in protein alpha-helices. If the m6A:U base pair is in a weaker stretch of dsRNA it may cause melting to form a shorter duplex with the unpaired m6A, now back in the relaxed syn conformation, stacked on the end of the shorter dsRNA duplex, often over the next 3ʹ C:G base pair in the RRACH consensus. Therefore, m6A both weakens the longer dsRNA duplex in which the m6A:U base pair is destabilizing and also favours the shorter dsRNA duplex by the improved base stacking of the unpaired m6A onto the end of the dsRNA. Thus, m6A has been described as causing structural switches in RNA. Certainly, the presence of methylation on a particular adenosine may determine where short dsRNA structures terminate locally or might lead to formation of an alternative preferred dsRNA structure where different structures have similar energies. However, these alternative dsRNA structures may not literally switch back and forth at a single m6A site unless demethylation occurs. Since ADARs require their editing sites to be located within 17 base pairs or more of dsRNA, a single m6A site could therefore tend to lead to loss of ADAR RNA editing sites nearby, i.e. the two modifications mostly compete and inactivation of METTL3 would lead to increased editing at nearby sites and possibly to gain of new sites in longer dsRNA duplexes (Fig. 1). A cluster of m6A might affect ADAR RNA editing on a larger scale by preventing dsRNA structures from forming within the cluster region or allowing formation of an alternative dsRNA structure; the enrichment of m6A sites near stop codons may also reduce RNA structures there to benefit translation.

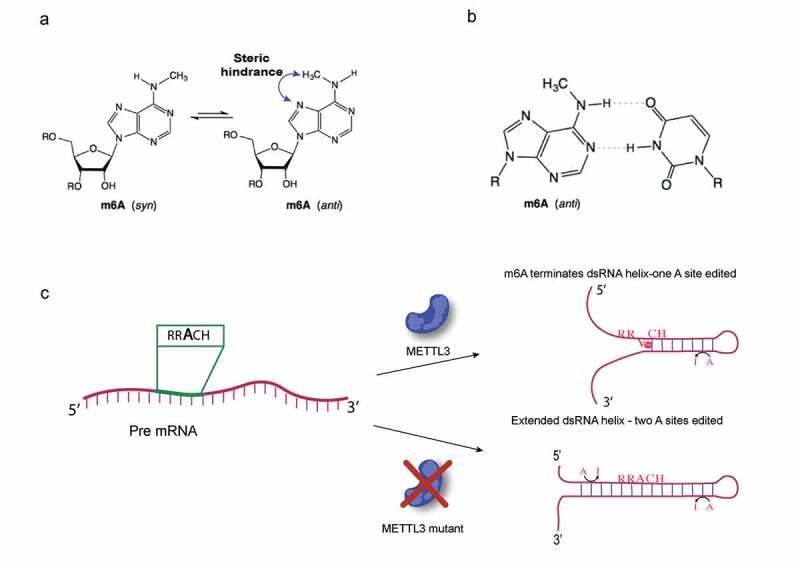

Figure 1.

m6A disrupts dsRNA duplex and favours formation of a shorter duplex with m6A stacked on the 5ʹ end of the dsRNA; m6A reduces dsRNA structure and thereby reduces ADAR RNA editing. A. In free nucleotide m6A, the methyl group adopts the relaxed syn conformation to avoid a steric clash with the N7 hydrogen that occurs in the anti conformation of the methyl group. B. In the m6A:U Watson-Crick base pair in dsRNA, the m6A methyl group is forced into the unfavourable, high energy, anti conformation having the steric clash. C. If local dsRNA structure is sufficiently weak, part of the dsRNA melts and m6A, now at the end of a shorter dsRNA duplex, relaxes to the syn conformation. m6A with the methyl in the syn conformation also base stacks on the end of the duplex more favourably than a G would, helping to stabilize the shorter dsRNA. In the presence of the METTL3 writer complex, m6A weakens dsRNA duplexes, either making them shorter or disrupting them entirely if the residual paired stretches are too short. In a Mettl3 mutant or knockdown the unmethylated RRACH sequence can become part of a more stable extended dsRNA helix, increasing the efficiency of ADAR editing at sites already edited in METTL3 wildtype; also, the extended dsRNA may make new sites available for ADAR RNA editing. ADARs require at least 17 base pairs of dsRNA for editing activity

ADAR RNA editing also weakens dsRNA structures although the effect of single inosines appears much weaker than the effect of single m6A bases. ADAR enzymatic activity was first identified by its ability to unwind dsRNA that had been injected into fertilized Xenopus eggs, which release ADARs from the nucleus during cell division, at germinal vesicle breakdown [22,23]. Up to half of all the adenosines were edited and the inosine modification forms a wobble base-pair with uracil (U), which is weaker a than an A:U base pair. Expression of proteins from synthetic mRNAs is helped by even surprisingly high levels of GC-richness and predicted dsRNA structure in UTRs and even in open reading frames which increase mRNA stability [24]. Both m6A and inosine, by reducing dsRNA structure, may help balance a tendency to evolve more stable mRNA sequences, perhaps especially in 3ʹ UTRs.

The direct consequence of m6A on A-to-I editing

The main study that has investigated the co-occurrence of these two modifications suggested that there is a mainly negative correlation between m6A and A-to-I editing [25]. The authors focused on m6A-positive and m6A-negative transcripts from individual genes and found a slight increases in A-to-I editing efficiencies and some additional weak sites in the m6A-negative transcripts. In addition, they performed knockdowns (KD) of both METTL3, the m6A writer, and of METTL14 in HEK 293 cells and found that in the METTL3 KD more A-to-I editing sites (8,587 out of 32,019 total sites) showed increased editing efficiency; 4,609 sites showed decreased editing efficiencies. This suggests that there is cross-talk between these two modifications and the relationship between them may not be straightforward (Fig. 1). One caveat about this study is that it is not fully quantitative, within the sequencing data, A-to-I editing levels change at one site from 8% to 10%, which is a 25% change but there is no measurement if there is twice, three times or more overall inosine present in the KD cells versus controls.

The ADAR1/METTL3 axis in cancer

There have been many studies relating to the role of m6A in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) patients [26,27,28]. Tumour biopsies from patients show that high levels of METTL3 correlate with poor patient survival [28]. METTL3 has been shown to regulate transcripts related to oncogenic signalling in GBM, including the ADAR (ADAR1) transcript [29]. A recent elegant study by Tassinari and colleagues demonstrated that METTL3 methylates the ADAR transcript near the stop codon in glioblastoma and this is one of the main targets of METTL3 involved in cell proliferation [30]. The methylation of ADAR mRNA results in the binding of YTHDF1 to the transcript and the subsequent upregulation of ADAR1 expression. This explains the previously observed discrepancy between mRNA levels and high protein expression of ADAR1 in glioblastoma, which is predictive of poor patient survival. Subsequently, when ADAR was silenced in different glioblastoma cell lines, there was a decrease in cell proliferation. By performing ADAR1-RNA coimmunoprecipitation it was demonstrated that ADAR1 binds to CDK2 mRNA and stabilizes it and increases its protein expression. ADAR1 does not require deaminase activity for this effect on the stability of CDK2 mRNA, illustrating that ADAR1 has important editing-independent activities [31]. Thus, methylation of the 3ʹUTR of ADAR mRNA by METTL3 results in the upregulation of ADAR1 protein that binds to and stabilizes CDK2 mRNA resulting in a boost to cell proliferation in glioblastoma. This study illustrates the interplay of these two RNA modification processes.

RNA modification, RNA structure and effects on innate immunity and antiviral sensing pathways

A seminal paper by Kariko and colleagues demonstrated that RNA modifications, including m6A and pseudouridine prevent activation of innate immune sensors by mRNA in dendritic cells [32]. They postulated that nucleoside modification suppresses the immune-stimulatory effect of RNA. This ground-breaking study laid the foundation for the RNA vaccines that are successful against the SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Toll-like receptors (TLRs) were presumed to be the targets originally. There has been no report of ADARs or inosines requiring the TLRs to evade the innate immune response.

Later experiments showed that ADARs and inosines are critical suppressors of aberrant innate immune responses to endogenous cellular dsRNAs. Adar mutant mice lacking ADAR1 are embryonic lethal and die by E12.5 [33,34]. These mice have high interferon (IFN) levels and elevated IFN stimulated gene (ISG) transcripts as well as problems with haemopoiesis. This complete Adar null mutation can be rescued to birth by generating an Adar, Mavs double mutant also lacking the mitochondrial antiviral-signalling protein (Mavs) [35] which is an essential adaptor for the activated RIG-I like receptors (RLRs). The authors postulated that inosine in dsRNA can help the cell discriminate ‘self’ from ‘non-self’ RNA and when ADAR1 is lacking then an IFN response is triggered as the dsRNAs lack inosine. In agreement with this, mutations in human ADAR cause Aicardi-Goutières syndrome (AGS) which is an interferonopathy. Children affected by ADAR mutant AGS6 display an aberrant high IFN response analogous to a viral infection; elevated IFN leads to calcification of the brain [36]. Another study demonstrated that AdarE861A embryos encoding a deamination-inactive Adar1 E861A protein die later than the Adar null mutant, at day E14.5, with a similar phenotype to the Adar null embryos [37]. Melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) is another RLR and AdarE861A, Ifih1 (gene name for MDA5) double mutants are completely rescued and live a normal life. This demonstrates that the ADAR1 E861A protein retains some important function in suppressing aberrant innate immune responses, probably by acting as a dsRNA-binding protein or through interactions with other proteins. Experiments performed in cell culture identify other innate immune proteins such as dsRNA-activated protein kinase R (PKR) [38] and the oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS)-RNase L pathway [39] that are involved in the innate immune response when ADAR1 is not present. In summary, when ADAR1 is not present, dsRNA lacking inosine binds to and activates MDA5 which is part of the RLR innate immune pathway; however, the ADAR1 protein also has an unknown editing-independent function that can supress early death of AdarE861A,Ifih1 double mutant pups.

Disruption of dsRNA structures as a result of A-to-I editing may contribute to preventing aberrant innate immune responses to cellular dsRNA. Mannion and colleagues also demonstrated that the heightened innate immune response in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Adar null mice was significantly reduced by transfecting a dsRNA oligonucleotide containing four I:U base pairs in the middle. ADAR RNA editing could destabilize such RNA duplexes that would otherwise could activate the dsRNA sensors; retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and MDA5 [40]. These dsRNA sensors bind dsRNA and oligomerize on it via their CARD domains. They may sense inosine in dsRNA by the weakening of dsRNA structure by I:U wobble base pairs. Molecular dynamics simulations show that replacing a single A·U with an I·U is stable in different sequence contexts [41] but two or more adjacent inosines do reduce dsRNA stability.

The idea that ADAR RNA editing prevents endogenous dsRNA from activating dsRNA sensors mainly by weaking the dsRNA pairing may be too simple. It is worth remembering that the majority of A-to-I editing occurs within transcripts containing embedded Alu sequences in humans [13] at individual adenosines that are edited at low percentage efficiencies. In the original publication where the Xenopus ADAR ‘RNA unwinding’ activity was described [22], the dsRNAs used were 800 nucleotides long [42]. Such long dsRNAs in mRNAs are very rare and have been evolutionarily selected against in Metazoa as presumably they would aberrantly activate the innate immune response [43]. Thus, with the exception of certain hyperedited sequences where multiple nearby adenosines are edited at high efficiencies, it is unlikely that A-to-I editing has a huge impact on structures of dsRNAs that would activate the dsRNA sensors. Also, the duplexes which can form between the, always slightly different, copies of repeats such as Alus are already imperfectly paired. Similarly, adenosines opposite an unpaired cytosine in imperfect dsRNA duplexes are commonly edited and the resulting I·C (cytosine) base-pairing after editing is more, rather than less, stable. An alternative idea for how RLR sensors detect I·U wobble base pairs in dsRNA is based on evidence that RLR do not melt dsRNA, instead they translocate along dsRNA and disassociate when they detect unpaired RNA bulges. We proposed that the translocating RLRs are even more discriminating; RLRs may sense the minor groove as they scan along dsRNA and disassociate when they reach a non-Watson-Crick structure, such as an I·U wobble base pair [35], or perhaps other modified bases such as m6A.

Since m6A affects dsRNA structure even more potently than inosine it may also affect innate immune activation by antiviral dsRNA sensors. There have been many publications on the role of m6A in the innate immune response, particularly in the response to viral infection (for review [44,45,46,47]). There has been a report on how human Metapneumovirus (HMPV) RNA that lacks m6A causes a higher IFN response [48]. The authors demonstrate that this heightened IFN response is dependent on the RLRs; on RIG-I but not on MDA5. RIG-I senses short dsRNA as well as 5ʹtriphosphate whereas MDA5 senses long dsRNA. The m6A deficient viral RNA enhances RIG-I binding and facilitates a conformational change in RIG-I which enhances downstream IFN induction. The authors suggest that m6A, similarly to inosine, acts as a molecular mark on the RNA and helps the cell distinguish self from non-self RNA. Thus, the data suggests that the RLRs which are cytoplasmic dsRNA sensors are sensitive to the presence of m6A and inosine in dsRNA, RIG-I is responsive to m6A in these experiments whereas inosine containing dsRNA inhibits MDA5. An interesting question is: what happens when both modifications are present on the same dsRNA?

m6A and inosine in circular RNAs

Circular RNAs (circRNAs), are generated by back-splicing and analysis of their biogenesis revealed the presence of complementary intronic Alu elements in successive introns that can pair to promote the back-splicing [49]. However complementary inverted Alu elements that form a dsRNA duplexes are also substrates for ADAR enzymes. Thus, it was not surprising when Rybak-Wolf and colleagues demonstrated that circRNA levels correlated negatively with expression of ADAR1 in mammalian brains [50]. Knockdown of ADAR1 in cell culture induced the elevated expression of specific neuronal circRNAs [50].

CircRNAs can also induce an innate immune response that is RIG-I-dependent [51] It was observed thatm6A in circRNAs strongly affects their ability to induce innate immune responses. Studies show that RIG-I binds to both unmodified and m6A-modified circRNAs. However, the conformational change in RIG-I that is required for downstream IFN activation occurs only on the unmodified circRNAs. This activation of RIG-I involves extrusion of the CARD domains followed by addition of lysine 63 (K63)-linked polyubiquitin chains that interact and stabilize the RIG-I 2-CARD domain oligomers. The YTHDF2 reader protein can additionally suppress innate immune responses to circRNA.

Roles of ADAR RNA editing and m6A in haemopoietic, myeloid and lymphoid cells

ADAR1 is essential for the maintenance of haematopoiesis but is dispensable for the myeloid lineage [52]. In the erythroid lineage Adar1 is required for both foetal and adult erythropoiesis, in a cell autonomous manner [53]. Extracellular fluid of Adar null embryos had 13-fold more IFN-α and over 80-fold more IFN-β than wildtype whereas IFN-γ was not detected [52]. When ADAR1 was lacking, an upregulation of ISGs was observed across multiple haematopoietic cell lines but not in B-lymphocytes and granulocytes. However, what was very striking was the magnitude of upregulation of the ISGs (up to 508-fold) [53]. This increased innate immune response is likely due to the increase in unedited dsRNA that is a viral mimicry. Again, the key innate immune receptor involved in this response is MDA5. Analysis of RNA editing by ADAR1 comparing erythrocytes and B lymphocytes revealed that 94/664 sites were differentially edited, with the average difference in editing efficiencies across different sites being ≤7%. The authors of this study hypothesized that the difference in response to the lack of ADAR1 between erythroid and myeloid cells is that the erythroid lineage does not have cell surface MHC. Therefore, erythrocytes may be more prepared to initiate an innate immune response and cell death against a viral infection, whereas B-cells are key effector immune cells that need to be kept alive.

It is more difficult to study haematopoiesis in mutants lacking m6A since m6A is required for embryonic stem cell differentiation and mice lacking m6A die at an earlier stage in development [12]. To circumvent this, haematopoiesis-specific Vav-Cre+-Mettl3fl/fl (vcMettl3−/–) mice were generated [54]. Cre induction leads to generation of vcMettl3−/- mutant mice which die predominantly at late embryonic stages and rarely were observed at birth. In the vcMettl3−/- foetal livers, which are the main sites of haematopoiesis in early foetuses, dsRNA was found to be enriched and embryos showed upregulation of ISGs and downstream activation of 2ʹ-5ʹ-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS), PKR and RLR pathways that function in the detection of dsRNAs. Thus, loss of m6A also results in defective foetal haematopoiesis. However, the major difference between the Adar and the vcMettl3−/- mutants is thatm6A is important for the myeloid lineage and vcMettl3−/-mutants have a skewing from differentiated granulocytes to immature monocytes with an accumulation of a population of phenotypically immature, functionally impaired, haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

Surprisingly, when analysing the dsRNA in vcMettl3−/- mutant foetal liver it was found not to be enriched in short interspersed nuclear elements (SINES) which are the substrates of ADAR1. Instead, most of the ninety-four RNAs isolated by immunoprecipitation with anti-dsRNA antibodies encoded proteins. Another one of these RNAs is the long noncoding RNA Malat1 which was previously shown to be highly m6A-modified. Another difference between vcMettl3 −/- mutants and Adar mutants is that no induction of type I IFN in foetal livers was observed in vcMettl3−/- but rather Ifnl3, a type III IFN, was increased. A deletion of Mavs, which is downstream in the RLR pathway, partially rescued the observed vcMettl3−/-haematopoietic defects, indicating that the RLRs activated by endogenous dsRNA contribute to Ifnl3 induction, although some other pathway may also be aberrantly activated. What is interesting is that a significant increase in Adar expression was observed in the vcMettl3−/- mutant; however, the increased Adar expression did not prevent activation of the innate immune response, consistent with m6A and inosine mainly affecting different cellular dsRNAs. All the information on m6A suppressing the activation of antiviral dsRNA sensors appear consistent with m6A acting rather similarly to inosine as an RNA mark of innate immune self.

m5Cand m6A coregulate mRNA export to the cytoplasm

The 5-methylcytosine modification (m5C) was one of the first described tRNA modifications [55]. The methodological development during the past 40 years, and the technological progress in nucleic acid sequencing over the past ten years enabled transcriptome-wide identification of m5C in other classes of RNAs, such as mRNA, rRNA and other non-coding RNAs [56,57,58]. In mRNA,m5C modifications is introduced either by members of the NOL1/NOP2/SUN domain (NSUN) protein family or by the DNA methyltransferase homologue 2 (DNMT2) [59]. NSUN2 targets both coding and noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) [57,60] (reviewed in [59]). In a seminal study, Yang X. and colleagues examined the m5C distribution within mRNAs [57]. By using bisulphite sequencing (BiSeq) analysis of RNAs isolated from HeLa cells and different mouse tissues they demonstrated that m5C marks occur preferentially in mRNAs, at CG-rich regions in downstream proximity to the translation start site. They found that the m5C pattern changes during animal development, independently of the transcript’s abundance in the cell. The study opened up new avenues of investigation on the potential roles of m5C modifications in mRNAs. In their pursuit of the role of m5C in mRNAs they identified ALYREF (THOC4) acting as an m5C-specific reader. NSUN2 knockdown by RNAi not only affected ALYREF binding to m5C target sites but also inhibited the export of NSUN2-modified mRNAs from the nucleus (Fig. 2). This suggested that NSUN2-mediated m5C modification in mRNA plays a role in ALYREF-dependent mRNA export to the cytoplasm.

Figure 2.

Model for crosstalk between m5C and m6A for mRNA export

A model of putative cooperation of m5C and m6A marks and their specific readers in the regulation of mRNA export. NSUN2 mediated m5C methylation occurs in the proximity of translation start site. It likely facilitates binding of the export factor and m5C reader ALYREF. ALYREF directly interacts with the m6A-demethylase ALKBH5 to induce m6A removal. Herein m5C-ALYREF mediated demethylation of m6A in 5ʹ mRNA region by ALKBH5 may be a prerequisite for the formation of an export competent mRNP.

A recent report by Li Q. and colleagues provided the first insights into the potential crosstalk between m5C and m6A [61]. The analysis revealed the presence of m5C and m6A modifications in the 3′ UTR of p21 mRNA, which were dependent on NSUN2 and METTL-3/METTL-14 activities, and found at AAmC and GAmC motifs, respectively [61]. Silencing of either of these enzymes dramatically downregulated both modifications concomitantly, and over-expression of NSUN2 and METTL-3/METTL-14 enhanced p21 mRNA translation [61]. Even though the study did not address the mechanisms of m5C and m6A crosstalk, the results for the first time indicated their synergistic effect on mRNA biology. It is possible that the presence of both modifications in the same mRNA enhances affinity to particular reader proteins. In another study, Dai X. and colleagues uncovered binding of m6A reader proteins to m5C modified RNA [62]. They applied stable isotope labelling using amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)-based quantitative proteomics in combination with electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs), to resolve the interactome of m5C in cell lysates. They observed that YTHDF1-3, particularly YTHDF2, interacted withthe m5C-modified RNA bait. Genetic ablation of YTHDF2 lead to substantial elevations in the levels of m5C at multiple loci in rRNA and affected rRNA maturation in human cells [62]. Even though evidence for a potential crosstalk between m5C and m6A via YTHD-protein was provided only for rRNA, the study of Dai X. and colleagues suggested that a similar interplay could also exist in mRNAs.

Importantly, the study of Yang X. and colleagues in which the authors showed that ALYREF is acting as a new m5C reader protein [57] is interesting in respect to our own recent results. We used BioID proximity labelling to identify interaction partners of m6A writer and eraser proteins in HEK293T cells (Covelo-Molares H. personal communication). We identified ALYREF as a genuine interaction partner of the m6A demethylase ALKBH5. ALKBH5 was previously linked to mRNA export because its depletion led to accumulation of polyadenylated RNAs in the cytoplasm [63]. It will be interesting to see whether loss of ALKBH5 activity in the cell will have a similar effect on ALYREF RNA binding as seen for NSUN2 or whether ALYREF and ALKBH5 interaction is the cause or the consequence of ALYREF m5C binding. These observations suggested the existence of m5C and m6A crosstalk and its role in mRNA export to the cytoplasm (Fig. 2). Further studies will be needed to investigate the orchestration mechanism underlying this crosstalk.

m6A and m1A mRNA marks are recognized by the same readers proteins

Apart from N6 methylation and deamination, adenosines in mRNAs can also be methylated at the N1 position [64]. m1A is prevalent in noncoding RNAs such the tRNAs, rRNAs, ncRNAs and mitochondrial RNAs [65,66,67,68,69] and its functions are dependent on the RNA class. For instance, m1A stabilizes tertiary conformation of tRNAs and rRNAs [70,71]. In tRNAs m1A typically enhances translation [70] whereas loss of m1A645 of 25S rRNA in yeast and m1A1322 methylation of 28S rRNA in humans impacts translation of a specific subset of mRNAs [71]. Similar to m6A, the m1A pathway is composed of reader, writer, and eraser proteins. Insights into a possible crosstalk of m6A and m1A came from a study which focused on the definition of m1A-binding proteins in HEK293T and HeLa cells [72]. Similar to their study on m5C, Dai X. and colleagues applied SILAC-based quantitative proteomics in combination with EMSA binding assays, to resolving the interactome of m1A, m6A and unmodified RNA oligonucleotides in cell lysates, respectively. The authors observed, that particular m6A readers from the known YTH domain containing protein family (YTHDF1-3 and YTHDC1) show binding affinity to m1A-modified RNAs [72]. The YTH domains however displayed 4–20 times stronger affinity binding to m6A RNA than to m1A RNA. Utilizing publicly available data on transcriptome-wide m1A-mapping and YTHD protein-specific RNA binding sites, Dai X. and colleagues discovered that binding sites of the YTHDF1-3 and YTHDC1 proteins comprise only 4.5% (YTHDF3) to 24.4% (YTHDF1) of all annotated m1A sites. Analysis of data on ribosome profiling and mRNA half-life from YTHD knockdown cells suggested that YTHDF1 may promote translation whereas YTHDF2 regulates stability of m1A-containing mRNAs [72]. However, they did not validate these observations experimentally. The recent study of Lao and Barron shared on bioRxiv indicated that GFP mRNA is decorated by m1A and m6A marks when expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-K1) [73]. They used a GFP reporter to tackle the interplay between various m1A and m6A readers and erasers in CHO-K1 cells [73]. They observed that the well-established m6A reader YTHDF2 targets m1A sites and facilitates GFP mRNA destabilization. This effect was further enhanced in combination with downregulation of m1A eraser ALKBH3, but not with by KD of m6A erasers FTO nor ALKBH5. In summary, YTHDF2 appeared to facilitate mRNA degradation through binding to m1A sites. However, mechanisms of chemical mark selectivity and the relevance of the same readers binding to the three different modifications (m6A, m1A and m5C) still remains to be addressed in detail [74] (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

A model for crosstalk of m6A and other mRNA modifications at mRNA

Some readers show ability to recognize more than one chemical mark in mRNA (on the left). This can have different consequences (on the right), such as: A. Competitive binding. B. Counter regulation by modifications. In this way RNA-modification-reader complex may act as a recruitment platform for other factors and/or can facilitate deposition/recognition of other modifications in the RNA molecule. C. Cooperative reader recruitment: Different modification at the same template act synergistically in cooperative manner to increase or manifest the load of common reader proteins at given mRNA template. Herein multi-readerassembly may facilitate events essential for mRNP packaging, remodelling, export or surveillance.

Not only the reader proteins but also some erasers possess activity at more than one chemical mark. FTO targets m6Am, m6A in mRNAs and snRNAs and m1A in tRNAs [75]. ALKBH1 shows demethylation activity on m3C mRNA and m1A in tRNAs [76,77,78]. The m1A eraser ALKBH3 can remove m6A marks from tRNAs [79]. Future studies will address whether targeting different modifications in mRNA and tRNA is a mechanism that allows some of these enzymes to coregulate gene expression, e.g. in stress conditions via targeting simultaneously translation and mRNA stability (see below).

m7G facilitates m6Am modification within the extended RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcript cap structure

N6,2-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am) is the second most abundant internal chemical modification of Pol II transcripts [80]. It is found directly downstream to the m7G cap, forming the extended cap structure [81,82]. If the 2′-O-methyladenosine (Am) is the first nucleotide to follow the m7G cap, the Pol II C-terminal domain-interacting methyltransferase (phosphorylated CTD-interacting factor 1, PCIF1) further methylates the adenosine at the N6 position to form m6Am [81,82]. PCIF1 activity has been studied mostly in the context of protein-coding transcripts. Due to the direct PCIF interaction with Pol II [83], it is likely that PCIF also modifies the ncRNA Pol II products, however this activity has not yet been assessed. PCIF1 activity requires the presence of the m7G cap and the 2ʹ-O methylation at the target adenosine ribose [84]. Both m6A and m6Am can be erased by the demethylase FTO [75]. Interestingly, the demethylation of m6Am demands multilevel crosstalk. Similar to PCIF1 activity, FTO m6Am demethylation is enhanced in the presence of the 5ʹ proximal m7G cap 75 .

m6A and m6Am are involved in common mechanisms of mRNA processing, stability and translation

m6A and m6Am methylations are both deposited on mRNAs and lncRNAs cotranscriptionally [81,84,85,86]. Although the direct crosstalk between m6A and m6Am was not identified so far, both modification were linked to the regulation of common mechanisms such as transcription, pre-mRNA splicing, stability and translation [81,84] (reviewed in [87]). Several studies revealed the role of m6A in the regulation of pre-mRNA constitutive and alternative splicing. The m6A reader protein YTHDC1 recruits SRSF3 (pre-mRNA splicing factor) to pre-mRNAs to promote exon inclusion by inhibiting the binding of SRSF10 [88]. This interaction, in turn, has prominent roles in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay during foetal development [28,88,89]. Despite certain scepticism about the extent of dynamics of m6A methylation, mutation or dysregulation of either FTO or ALKBH5 also lead to splicing defects [90,91]. FTO is particularly interesting as it has the potential to regulate pre-mRNA splicing by altering the m6A pattern on pre-mRNAs as well as affecting the spliceosome via targeting m6Am and m6A in snRNAs [82,90,92,93,94]. Reduction of FTO leads to elevation of m6A, which promotes inclusion of dependent on SRSF2 (acting as an m6A reader) [95]. Similarly, to FTO, METTL16 revealed prevalently intronic binding in pre-mRNAs and its depletion led to an altered splicing pattern [96]. Currently, it is not known whether FTO targets m6As deposited by enzymes other than METTL3/14 and PCIF1 enzymes.

The role of the 5ʹcap- m6Am and its removal by FTO still remains enigmatic. Stabilization of m6Am in snRNA caps by FTO depletion does not impair their assembly into snRNPs but m6Am in snRNP caps appears to affect alternative splicing [82]. Furthermore, the splicing efficiency and specificity also depend on the internal m6A and m6Am marks in snRNAs. The methyltransferase METTL16 deposits m6A within U6 snRNA and U2 snRNA contains internal m6Am modifications introduced by METTL4 [93,96]. In both cases, the modifications appear important for the regulation of pre-mRNA splicing of a specific subset of exons [93,96]. Crosslinking immunoprecipitation with high-throughput sequencing (CLIP-seq) analyses showed FTO binding to both U6 and U2 snRNAs which could further explain the FTO-dependent alternative splicing phenotypes [90,96].

Whereas m6A modification in mRNAs has been linked to a number of steps in mRNA metabolism [reviewed in [87,97]) the role of m6Am in mRNA biology is rather controversial. Mauer et al. reported that m6Am and PCIF1 show positive regulation of mRNA stability and translation [98]. Akichika et al., reported m6Am- and PCIF1-mediated positive regulation of cap-dependent translation but questioned their involvement in mRNA stability [81]. On the contrary, Sendinc et al. concluded that PCIF1 activity negatively influences cap-dependent translation, because m6Am antagonized interaction with the cap binding and translation factor eIF4E [99]. Boulias et al., showed m6Am or PCIF1 has a more prominent role in mRNA stability than in translation [84]. Recently, FTO depletion was shown to lead to mRNA destabilization due to increased m6A and thus YTHDF2 recruitment and subsequent mRNA decay [100]. On the other hand, regulation of the cap-linked m6Am by FTO in the cytoplasmic pool of mRNAs appears important in cancer development. Relier et al. reported that FTO downregulation leads to in vivo tumorigenicity and increased chemoresistance of colon cancer stem cells [101].

It is possible that, to a certain extent, the mRNA stability is also regulated by FTO targeting m6Am in mRNAs. Because of the many open questions and contradictory reports, we await thorough analyses to better understand the role of m6Am and any potential coregulation between m6A and m6Am.

Pseudouridylation in mRNAs and its potential interplay with RNA methylation

Pseudouridine (Ψ) is a well-studied and understood RNA modification, that for decades was considered to be restricted to non-coding RNAs, such as tRNAs, rRNAs, snoRNAs and snRNAs [102]. With the development of Ψ-seq, which allows transcriptome-wide definition of Ψ sites at nucleotide resolution, detection of Ψ was recently expanded to include sites in protein coding mRNAs in yeast as well as in humans [103,104]. Both studies uncovered that pseudouridinylation in mRNAs can be mediated either by non-essential, consensus-motif binding pseudouridine synthases (PUSs) or by the essential PUS; Cbf5 in yeast and by its orthologue DKC1/Dyskerin in humans, which modify mRNA target sites complementary to the PUS-bound H/ACA snoRNA.

The impact of Ψ on RNA structure, stability and RNA base pairing [102], implies that, besides its potential roles in mRNA regulation, Ψ in mRNAs could potentially cooperate, regulate or be regulated by other mRNA modifications such as RNA methylation. A support for this concept, derives from a study on mRNAs coding for Yamanaka factors, which induce cellular pluripotency [105]. Herein, L. Warren and colleagues revealed already 10 years ago that modifications of these exogenous mRNAs by Ψ and m5C increased their efficacy in cellular reprogramming compared to unmodified mRNAs [105]. Similarly, Andries et al. showed that simultaneous modification by Ψ and m5C greatly enhanced reporter gene expression in mice and multiple cell lines [106]. Interestingly, dependent on the combination of and extent of the marks, they had distinct consequences. Compared to m5C or Ψ mRNA, mRNA containing both m1-pseudouridine and m5C showed a higher translational rate in in vivo [106]. The mechanism of the combinatorial effect of the different marks is not known and will be an interesting question to tackle in the future.

Our current knowledge in the field of epitranscriptomics is expanding nearly on a monthly basis. It will be interesting to see which study will provide mechanistic insights to address how modifications might affect each other and how these modifications may cooperate in regulation of cellular programs essential for development and cancer progression. At this stage however, we are missing information about the underlying molecular mechanisms for the cross talks between individual modifications.

Acknowledgments

This paper was based upon work from COST Action CA16120 EPITRAN, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology)“ and Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports within programme INTER-COST (LTC18052).(MOC and SV).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- [1].Boccaletto P, Machnicka MA, Purta E, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D303–D7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Xu L, Seki M.. Recent advances in the detection of base modifications using the Nanopore sequencer. J Hum Genet. 2020;65:25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hogg M, Paro S, Keegan LP, et al. RNA editing by mammalian ADARs. Adv Genet. 2011;73:87–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zaccara S, Ries RJ, Jaffrey SR. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:608–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Licht K, Hartl M, Amman F, et al. Inosine induces context-dependent recoding and translational stalling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gallo A, Vukic D, Michalik D, et al. ADAR RNA editing in human disease; more to it than meets the I. Hum Genet. 2017;136:1265–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chen Z, Qi M, Shen B, et al. Transfer RNA demethylase ALKBH3 promotes cancer progression via induction of tRNA-derived small RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:2533–2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fu Y, Dominissini D, Rechavi G, et al. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m(6)A RNA methylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Veliz EA, Easterwood LM, Beal PA. Substrate analogues for an RNA-editing adenosine deaminase: mechanistic investigation and inhibitor design. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10867–10876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Eggington JM, Greene T, Bass BL. Predicting sites of ADAR editing in double-stranded RNA. Nat Commun. 2011;2:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tan MH, Li Q, Shanmugam R, et al. Dynamic landscape and regulation of RNA editing in mammals. Nature. 2017;550:249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Batista PJ, Molinie B, Wang J, et al. m(6)A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:707–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bazak L, Levanon EY, Eisenberg E. Genome-wide analysis of Alu editability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:6876–6884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bazak L, Haviv A, Barak M, et al. A-to-I RNA editing occurs at over a hundred million genomic sites, located in a majority of human genes. Genome Res. 2014;24:365–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Porath HT, Schaffer AA, Kaniewska P, et al. A-to-I RNA editing in the earliest-diverging eumetazoan phyla. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:1890–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, et al. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell. 2017;169:1187–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Meng J, Lu Z, Liu H, et al. A protocol for RNA methylation differential analysis with MeRIP-Seq data and exomePeak R/bioconductor package. Methods. 2014;69:274–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chen K, Lu Z, Wang X, et al. High-resolution N(6) -methyladenosine (m(6) A) map using photo-crosslinking-assisted m(6) A sequencing. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:1587–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Borchert GM, Gilmore BL, Spengler RM, et al. Adenosine deamination in human transcripts generates novel microRNA binding sites. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4801–4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Das Mandal S, Ray PS. Transcriptome-wide analysis reveals spatial correlation between N6-methyladenosine and binding sites of microRNAs and RNA-binding proteins. Genomics. 2021;113:205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Roost C, Lynch SR, Batista PJ, et al. Structure and thermodynamics of N6-methyladenosine in RNA: a spring-loaded base modification. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2107–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bass BL, Weintraub H. A developmentally regulated activity that unwinds RNA duplexes. Cell. 1987;48:607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rebagliati MR, Melton DA. Antisense RNA injections in fertilized frog eggs reveal an RNA duplex unwinding activity. Cell. 1987;48:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mauger DM, Cabral BJ, Presnyak V, et al. mRNA structure regulates protein expression through changes in functional half-life. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2019;116:24075–24083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Xiang JF, Yang Q, Liu CX, et al. N(6)-methyladenosines modulate A-to-I RNA editing. Mol Cell. 2018;69:126–35 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chai RC, Wu F, Wang QX, et al. m(6)A RNA methylation regulators contribute to malignant progression and have clinical prognostic impact in gliomas. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11:1204–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wang W, Li J, Lin F, et al. Identification of N(6)-methyladenosine-related lncRNAs for patients with primary glioblastoma. Neurosurg Rev. 2021;44:463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li F, Yi Y, Miao Y, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine modulates nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2019;79:5785–5798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Visvanathan A, Patil V, Abdulla S, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine landscape of glioma stem-like cells: METTL3 is essential for the expression of actively transcribed genes and sustenance of the oncogenic signaling. Genes (Basel). 2019;10:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tassinari V, Cesarini V, Tomaselli S, et al. ADAR1 is a new target of METTL3 and plays a pro-oncogenic role in glioblastoma by an editing-independent mechanism. Genome Biol. 2021;22:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Heale BS, Keegan LP, McGurk L, et al. Editing independent effects of ADARs on the miRNA/siRNA pathways. Embo J. 2009;28:3145–3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kariko K, Buckstein M, Ni H, et al. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005;23:165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hartner JC, Schmittwolf C, Kispert A, et al. Liver disintegration in the mouse embryo caused by deficiency in the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4894–4902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang Q, Miyakoda M, Yang W, et al. Stress-induced apoptosis associated with null mutation of ADAR1 RNA editing deaminase gene. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4952–4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mannion NM, Greenwood SM, Young R, et al. The RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1 controls innate immune responses to RNA. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1482–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Rice GI, Kasher PR, Forte GM, et al. Mutations in ADAR1 cause Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome associated with a type I interferon signature. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1243–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Liddicoat BJ, Piskol R, Chalk AM, et al. RNA editing by ADAR1 prevents MDA5 sensing of endogenous dsRNA as nonself. Science. 2015;349:1115–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chung H, Calis JJA, Wu X, et al. Human ADAR1 prevents endogenous RNA from triggering translational shutdown. Cell. 2018;172:811–24.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Li Y, Banerjee S, Goldstein SA, et al. Ribonuclease L mediates the cell-lethal phenotype of double-stranded RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 deficiency in a human cell line. eLife. 2017;6:e25687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Quin J, Sedmik J, Vukic D, et al. ADAR RNA modifications, the epitranscriptome and innate immunity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021;46(9):758–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Spackova N, Reblova K. Role of inosine(-)Uracil Base Pairs in the canonical RNA duplexes. Genes (Basel). 2018;9:324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Harland R, Weintraub H. Translation of mRNA injected into Xenopus oocytes is specifically inhibited by antisense RNA. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1094–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Barak M, Porath HT, Finkelstein G, et al. Purifying selection of long dsRNA is the first line of defense against false activation of innate immunity. Genome Biol. 2020;21:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Tang L, Wei X, Li T, et al. Emerging Perspectives of RNA N (6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) modification on immunity and autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2021;12:630358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Shulman Z, Stern-Ginossar N. The RNA modification N6-methyladenosine as a novel regulator of the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lou X, Wang JJ, Wei YQ, et al. Emerging role of RNA modification N6-methyladenosine in immune evasion. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chen J, Sun Y, Ou Z, et al. Androgen receptor-regulated circFNTA activates KRAS signaling to promote bladder cancer invasion. EMBO Rep. 2020;21:e48467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Lu M, Zhang Z, Xue M, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine modification enables viral RNA to escape recognition by RNA sensor RIG-I. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:584–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Jeck WR, Sorrentino JA, Wang K, et al. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA. 2013;19:141–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Rybak-Wolf A, Stottmeister C, Glazar P, et al. Circular RNAs in the mammalian brain are highly abundant, conserved, and dynamically expressed. Mol Cell. 2015;58:870–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chen YG, Chen R, Ahmad S, et al. N6-methyladenosine modification controls circular RNA immunity. Mol Cell. 2019;76:96–109 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Hartner JC, Walkley CR, Lu J, et al. ADAR1 is essential for maintenance of hematopoiesis and suppression of interferon signaling. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Liddicoat BJ, Hartner JC, Piskol R, et al. Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing by ADAR1 is essential for normal murine erythropoiesis. Exp Hematol. 2016;44:947–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Gao Y, Vasic R, Song Y, et al. m(6)A modification prevents formation of endogenous double-stranded RNAs and deleterious innate immune responses during hematopoietic development. Immunity. 2020;52:1007–21 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Gambaryan AS, Venkstern TV, Bayev AA. On the mechanism of tRNA methylase-tRNA recognition. Nucleic Acids Res. 1976;3:2079–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Tang H, Fan X, Xing J, et al. NSun2 delays replicative senescence by repressing p27 (KIP1) translation and elevating CDK1 translation. Aging (Albany NY). 2015;7:1143–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Yang X, Yang Y, Sun B-F, et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes mRNA export — NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m5C reader. Cell Res. 2017;27(5):606–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hussain S, Sajini AA, Blanco S, et al. NSun2-mediated cytosine-5 methylation of vault noncoding RNA determines its processing into regulatory small RNAs. Cell Rep. 2013;4:255–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Bohnsack KE, Hobartner C, Bohnsack MT. Eukaryotic 5-methylcytosine (m(5)C) RNA methyltransferases: mechanisms, cellular functions, and links to disease. Genes (Basel). 2019;10:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Squires JE, Patel HR, Nousch M, et al. Widespread occurrence of 5-methylcytosine in human coding and non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5023–5033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Li Q, Li X, Tang H, et al. NSUN2-mediated m5C methylation and METTL3/METTL14-mediated m6A methylation cooperatively enhance p21 translation. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118:2587–2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Dai X, Gonzalez G, Li L, et al. YTHDF2 binds to 5-methylcytosine in RNA and modulates the maturation of ribosomal RNA. Anal Chem. 2020;92:1346–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49:18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Dominissini D, Nachtergaele S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, et al. The dynamic N(1)-methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature. 2016;530:441–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Safra M, Sas-Chen A, Nir R, et al. The m1A landscape on cytosolic and mitochondrial mRNA at single-base resolution. Nature. 2017;551:251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Salmon-Divon M, et al. Transcriptome-wide mapping of N(6)-methyladenosine by m(6) A-seqbased on immunocapturing and massively parallel sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:176–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Peifer C, Sharma S, Watzinger P, et al. Yeast Rrp8p, a novel methyltransferase responsible for m1A 645 base modification of 25S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1151–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Sharma S, Lafontaine DLJ. ‘View From A Bridge’: a new perspective on eukaryotic rRNA base modification. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40:560–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].RajBhandary UL, Stuart A, Faulkner RD, et al. Nucleotide sequence studies on yeast phenylalanine sRNA. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1966;31:425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Pan T. Modifications and functional genomics of human transfer RNA. Cell Res. 2018;28:395–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Sharma S, Hartmann JD, Watzinger P, et al. A single N(1)-methyladenosine on the large ribosomal subunit rRNA impacts locally its structure and the translation of key metabolic enzymes. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Dai X, Wang T, Gonzalez G, et al. Identification of YTH domain-containing proteins as the readers for N1-methyladenosine in RNA. Anal Chem. 2018;90:6380–6384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Lao N, Barron N. Cross-talk between m6A and m1A regulators, YTHDF2 and ALKBH3 fine-tunes mRNA expression. bioRxiv. 2019. 10.1101/589747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Khoddami V, Yerra A, Mosbruger TL, et al. Transcriptome-wide profiling of multiple RNA modifications simultaneously at single-base resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:6784–6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wei J, Liu F, Lu Z, et al. Differential m(6)A, m(6)Am, and m(1)A demethylation mediated by FTO in the cell nucleus and cytoplasm. Mol Cell. 2018;71:973–85 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Ma CJ, Ding JH, Ye TT, Yuan BF, Feng YQ. AlkB homologue 1 demethylates N(3)-methylcytidine in mRNA of mammals. ACS Chem Biol. 2019;14:1418–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Liu F, Clark W, Luo G, et al. ALKBH1-mediated tRNA demethylation regulates translation. Cell. 2016;167:816–28 e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Westbye MP, Feyzi E, Aas PA, et al. Human AlkB homolog 1 is a mitochondrial protein that demethylates 3-methylcytosine in DNA and RNA. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25046–25056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Ueda Y, Ooshio I, Fusamae Y, et al. AlkB homolog 3-mediated tRNA demethylation promotes protein synthesis in cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Wei C, Gershowitz A, Moss B. N6, O2ʹ-dimethyladenosine a novel methylated ribonucleoside next to the 5ʹ terminal of animal cell and virus mRNAs. Nature. 1975;257:251–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Akichika S, Hirano S, Shichino Y, et al. Cap-specific terminal N (6)-methylation of RNA by an RNA polymerase II-associated methyltransferase. Science. 2019;363:eaav0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Mauer J, Sindelar M, Despic V, et al. FTO controls reversible m(6)Am RNA methylation during snRNA biogenesis. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15:340–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Fan H, Sakuraba K, Komuro A, et al. PCIF1, a novel human WW domain-containing protein, interacts with the phosphorylated RNA polymerase II. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Boulias K, Toczydlowska-Socha D, Hawley BR, et al. Identification of the m(6)Am methyltransferase PCIF1 reveals the location and functions of m(6)Am in the transcriptome. Mol Cell. 2019;75:631–43 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Darnell RB, Ke S, Darnell JE Jr. Pre-mRNA processing includes N6 methylation of adenosine residues that are retained in mRNA exons and the fallacy of “RNA epigenetics”. RNA. 2018;24:262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Ke S, Pandya-Jones A, Saito Y, et al. m(6)A mRNA modifications are deposited in nascent pre-mRNA and are not required for splicing but do specify cytoplasmic turnover. Genes Dev. 2017;31:990–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Covelo-Molares H, Bartosovic M, Vanacova S. RNA methylation in nuclear pre-mRNA processing. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2018;9:e1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Xiao W, Adhikari S, Dahal U, et al. Nuclear m(6)A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2016;61:507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Kasowitz SD, Ma J, Anderson SJ, et al. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates alternative polyadenylation and splicing during mouse oocyte development. Plos Genet. 2018;14:e1007412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Bartosovic M, Molares HC, Gregorova P, et al. N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO targets pre-mRNAs and regulates alternative splicing and 3ʹ-end processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:11356–11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Tang C, Klukovich R, Peng H, et al. ALKBH5-dependent m6A demethylation controls splicing and stability of long 3ʹ-UTR mRNAs in male germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E325–E33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Chen H, Gu L, Orellana EA, et al. METTL4 is an snRNA m(6)Am methyltransferase that regulates RNA splicing. Cell Res. 2020;30:544–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Goh YT, Koh CWQ, Sim DY, et al. METTL4 catalyzes m6Am methylation in U2 snRNA to regulate pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:9250–9261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Mendel M, Delaney K, Pandey RR, et al. Splice site m(6)A methylation prevents binding of U2AF35 to inhibit RNA splicing. Cell. 2021;184:3125–42 e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Chao Y, Jiang Y, Zhong M, et al. Regulatory roles and mechanisms of alternative RNA splicing in adipogenesis and human metabolic health. Cell Biosci. 2021;11:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Warda AS, Kretschmer J, Hackert P, et al. Human METTL16 is a N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) methyltransferase that targets pre-mRNAs and various non-coding RNAs. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:2004–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Lee Y, Choe J, Park OH, et al. Molecular mechanisms driving mRNA degradation by m(6)A modification. Trends Genet. 2020;36:177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Mauer J, Luo X, Blanjoie A, et al. Reversible methylation of m(6)Am in the 5ʹ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature. 2017;541:371–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Sendinc E, Valle-Garcia D, Dhall A, et al. PCIF1 catalyzes m6Am mRNA methylation to regulate gene expression. Mol Cell. 2019;75:620–30 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Wang F, Liao Y, Zhang M, et al. N6-methyladenosine demethyltransferase FTO-mediated autophagy in malignant development of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2021;40:3885–3898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Relier S, Ripoll J, Guillorit H, et al. FTO-mediated cytoplasmic m(6)Am demethylation adjusts stem-like properties in colorectal cancer cell. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Charette M, Gray MW. Pseudouridine in RNA: what, where, how, and why. IUBMB Life. 2000;49:341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Carlile TM, Rojas-Duran MF, Zinshteyn B, et al. Pseudouridine profiling reveals regulated mRNA pseudouridylation in yeast and human cells. Nature. 2014;515:143–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Schwartz S, Bernstein DA, Mumbach MR, et al. Transcriptome-wide mapping reveals widespread dynamic-regulated pseudouridylation of ncRNA and mRNA. Cell. 2014;159:148–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, et al. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:618–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Andries O, Mc Cafferty S, De Smedt SC, et al. N(1)-methylpseudouridine-incorporated mRNA outperforms pseudouridine-incorporated mRNA by providing enhanced protein expression and reduced immunogenicity in mammalian cell lines and mice. J Control Release. 2015;217:337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]