Abstract

Using broad-spectrum primers, we have amplified, cloned, and sequenced a 620-bp fragment of the “Tropheryma whippelii” heat shock protein 65 gene (hsp65) from the heart valve of a patient with Whipple's endocarditis. The deduced amino acid sequence shows high similarity to those from actinobacteria, confirming that “T. whippelii” is indeed a member of this phylum. Based on the nucleotide sequence, we have developed a “T. whippelii”-specific seminested PCR. Seventeen patients shown to be positive by 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) PCR and/or internal transcribed spacer (ITS) PCR were also positive by hsp65 PCR. All 33 control specimens from patients without Whipple's disease and negative for “T. whippelii” by both seminested 16S rDNA and ITS PCR remained negative. All amplicons digested with XhoI revealed an identical restriction pattern. Eight of the 17 hsp65 amplicons representing all three previously described ITS types were sequenced. Three of the amplicons showed slight differences, but none of the mutations detected affected the amino acid sequence of the corresponding protein. We conclude that the hsp65 gene is a suitable target for the specific detection of “T. whippelii.” Its product represents a putative antigen for a future serodiagnostic assay.

Whipple's disease is an infectious illness associated with a wide variety of intestinal and extraintestinal manifestations (5). Since untreated disease leads to death and because adequate antimicrobial therapy for diseases with similar clinical presentations differs significantly in the duration and choice of drugs, a reliable laboratory diagnosis is of considerable interest. The causative agent has been propagated in human macrophages deactivated with interleukin-4 (20), but stable subcultures have been established only very recently (15). Consequently, only limited information is available about its genome. Based on its 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequence, it was classified as a member of the gram-positive bacteria with high G+C content and named “Tropheryma whippelii” (16, 25). Since then, several PCR systems have been developed to identify parts of its 16S rDNA (1, 4, 18), of the 16S-23S internal transcribed spacer (ITS) (12, 14), or of the 23S rDNA (13).

Recently, “T. whippelii” DNA has been found in duodenal biopsy tissue, gastric juice, and saliva specimens but not in dental stone, of patients without Whipple's disease (7, 22; F. Dutly, H. P. Hinrikson, T. Seidel, S. Morgenegg, M. Altwegg, and P. Bauerfeind, submitted for publication). These findings are to be confirmed using a target completely different from the rRNA genes used in all these studies. For this purpose, the heat shock protein 65 gene (hsp65) was considered, as it contains, like 16S rDNA, conserved and variable regions which allow the use of both broad-range and genus-specific primers for amplification (8, 23). This gene may be used not only as the target of a diagnostic PCR assay but also as the basis for a recombinant antigen. Such an antigen could be a very valuable tool for the noninvasive serodiagnosis of Whipple's disease as previously shown for other organisms (26).

Using both broad-range and specific approaches, we have amplified, cloned, and sequenced a 620-bp fragment of the hsp65 gene of “T. whippelii.” Based on this fragment, a seminested PCR was developed and evaluated with clinical specimens previously analyzed by PCR using the 16S rDNA as the target.

(Different parts of this study were presented at the Annual Meeting of the German Society for Hygiene and Microbiology [DGHM], Regensburg, Germany, 11 to 14 October 1999 and at the 100th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Los Angeles, Calif., 21–25 May 2000.).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and specimens.

DNA extracted from the heart valve of a patient with confirmed Whipple's endocarditis (patient 16 [Table 1]) was used for cloning and sequencing of the hsp65 fragment. Clinical specimens from 17 patients with or without confirmed Whipple's disease previously shown to be positive for “T. whippelii” 16S rDNA by seminested PCR using primer pair TW-1 and TW-2 followed by TW-4 and TW-2 (2) or by 16S-23S internal transcribed spacer (ITS) PCR (12) were investigated (Table 1). They included seven gastric aspirates, seven intestinal tissue specimens from biopsies, one cerebrospinal fluid specimen, one heart valve specimen, and one saliva specimen. One of the intestinal tissue specimens from biopsies, was embedded in paraffin.

TABLE 1.

Clinical specimens used to analyze the hsp65 region of “T. whippelii”

| Patient

|

Specimen

|

PCR results

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | WDa | Origin | Code | Histology or stainingb | 16S rDNA fragmentc | 16S-23S rDNA spacer typed |

hsp65 fragment with the following no. of cyclese:

|

|

| 30 | 40 | |||||||

| 1 | − | Small intestine | 5996/96 | Normal | + | 2 | + | + |

| 2 | − | Gastric aspirate | V/99 | NDf | + | 3 | + | + |

| 3 | − | Gastric aspirate | III/99 | ND | + | ND | + | + |

| 4 | − | Gastric aspirate | X/99 | ND | + | ND | + | + |

| 5 | − | Gastric aspirate | XI/99 | ND | + | ND | + | + |

| 6 | + | Duodenum | 5713/96 | Normal | + | 1 | + | + |

| 7 | − | Gastric aspirate | 761/97 | ND | + | ND | + | + |

| 8 | − | Gastric aspirate | 1124II/97 | ND | + | 1 | + | + |

| 9 | + | Small intestine | 5766/96 | Normal | +g | 1 | + | + |

| 10 | − | Duodenum | 604/97 | PAS neg. | + | 2 | + | + |

| 11 | + | Ileum | 2249/96 | Normal | + | 2 | + | + |

| 12 | + | Small intestine | 368/97 | Normal | + | 1 | + | + |

| 13 | − | Gastric aspirate | 672/97 | ND | + | 3 | + | + |

| 14 | − | Saliva | 1/97 | ND | + | ND | + | + |

| 15 | + | PEh duodenum | 459/98 | ND | + | 1 | + | + |

| 16 | + | Heart valve | 724/98 | Gram pos. | + | 1 | + | + |

| 17 | + | Cerebrospinal fluid | 14/98 | ND | − | 2 | + | + |

Presence (+) or absence (−) of Whipple's disease (WD) based on overall assessment of the patient including clinical and laboratory data. Specimens of most patients without WD are from a previous prospective study (7).

Overall histologic assessment or result (positive [pos.] or negative [neg.]) of Gram or periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain.

Species-specific seminested PCR with primers TW-1 and TW-2 followed by TW-4 and TW-2 (2).

By means of “T. whippelii” spacer type-specific nested PCR assays (12).

Cycles used for reamplification.

ND, no data available.

Primers TW1 and TW3 (1).

PE, paraffin-embedded.

Controls.

Clone pTWhsp-3 containing the partial hsp65 fragment flanked by primers uni-f and hgc-r (see below) was used as a positive control. Negative controls included 17 intestinal tissue specimens from biopsies, 14 gastric aspirates, one cerebrospinal fluid specimen, and one sample of rinse fluid of a knee. These specimens were all from patients without Whipple's disease (not shown in Table 1) and were negative for “T. whippelii” by both seminested 16S rDNA PCR using primers TW-1 and TW-2 followed by TW-4 and TW-2 (2) and by type-specific PCR targeting the 16S-23S ITS (12). Additional controls included one isolate each of “Corynebacterium aquaticum” and Escherichia coli grown aerobically on Columbia agar (Becton Dickinson) with 5% sheep blood at 37°C for 1 to 3 days, molecular grade H2O (LAL Reagent water (BioWhittaker, Europe, Verviers, Belgium), and human DNA (Sigma Chemie, Buchs, Switzerland).

Extraction of DNA.

The paraffin-embedded tissue (two to five 5- to 10-μm-thick sections per specimen) was suspended in 200 μl of digestion buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.5], 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate) without proteinase K. Mixtures were incubated at 95°C for 10 min with moderate agitation in a thermomixer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) followed by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 30 min at room temperature. The resulting paraffin layers were removed with sterile pipette tips. Proteinase K (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) was then added to a final concentration of 200 μg per ml for further processing as described below for tissue specimens. Saliva (300 μl) was first liquified with 300 μl of 3% NALC (N-acetyl-l-cysteine; Sigma) followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 14,000 × g. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was then treated exactly as described below for tissue specimens. Cerebrospinal fluid specimens, gastric aspirates, and a sample of rinse fluid of a knee were centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g. These pellets and biopsy specimens were suspended in 200 μl of digestion buffer containing 200 μg of proteinase K per ml and incubated at 55°C for 1.5 h with agitation. DNA was extracted with QIAamp DNA binding columns (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol except that in the final step only 100 μl (instead of 200 μl) of elution buffer AE was used. Five microliters of the eluate was used for PCR. “C. aquaticum” and E. coli DNA were obtained by suspending one loop of bacterial biomass in 200 μl of 4% CHELEX 100 (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). After incubation at 95°C for 15 min and centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min, 1 μl of the supernatant was used for PCR.

PCR assays.

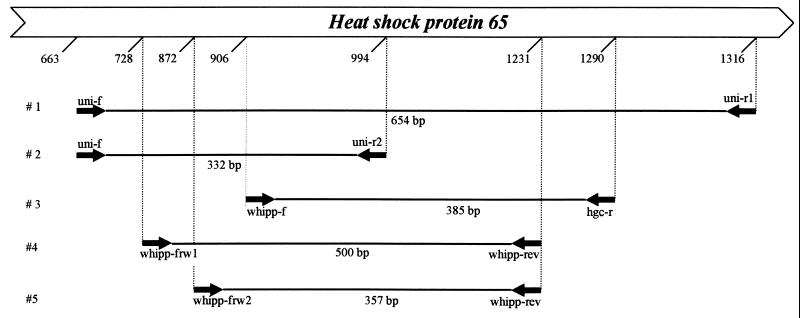

All PCRs were performed on a Gene Amp PCR System 9600 (Perkin-Elmer) and included an initial activation-denaturation step of 12 min at 95°C and a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C. Amplification and reamplification were both done in a final volume of 50 μl containing dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dUTP at a concentration of 200 μM each, 25 pmol of the corresponding primers, and 2.5 U of AmpliTaqGold polymerase including the appropriate amount of optimized buffer (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). For reamplification of fragments to be characterized by restriction enzyme analysis, dTTP was used instead of dUTP. For all reamplifications, 1 μl of the first amplification mixture was used as the template. For amplifications, but not for reamplifications, 2% Tween 20 (12) and uracil N-glycosylase (0.25 U/50 μl; Inotech, Dottikon, Switzerland) were added to prevent carryover contamination from previous amplifications (9). PCR products (10 μl) were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light. Primers used for PCR are listed in Table 2. Broad-range (uni-f, uni-r1, and uni-r2) and actinobacterium-specific (hgc-r) primers were derived from hsp65 consensus regions based on sequences deposited in GenBank/EMBL databases. The “T. whippelii”-specific primers (whipp-frw1, whipp-frw2, and whipp-rev) were chosen from the partial hsp65 gene sequence determined in this study. Amplifications with systems 1 and 2 (Fig. 1) consisted of 40 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C. Reamplification with system 3 was performed for 30 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C. Amplification with system 4 consisted of 40 cycles with 1 cycle consisting of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 57°C, and 1 min at 72°C. Reamplification with system 5 was performed for 30 and 40 cycles with 1 cycle consisting of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for amplification of partial hsp65 genes of “T. whippelii” and “C. aquaticum”

| Sense and primer | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Positionb | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | |||

| uni-f | CCGTACGAGAABATBGGHGC | 663–682 | Bacteriac |

| whipp-f | GCCTGCGCCTCGATCTCTGC | 906–925 | “T. whippelii”d |

| whipp-frw1 | TGACGGGACCACAACATCTG | 728–747 | “T. whippelii” |

| whipp-frw2 | CGCGAAAGAGGTTGAGACTG | 872–881 | “T. whippelii” |

| Reverse | |||

| uni-r1 | RCCRAAGCCMGGRGCYTT | 1316–1299 | Bacteria |

| uni-r2 | ATGACGCCTTCNTTDCCNAC | 994–975 | Bacteria |

| hgc-r | CCGACTTGAAGGTGCCRCGG | 1290–1271 | Actinobacteriac |

| whipp-rev | ACATCTTCAGCAATGATAAGAAGTT | 1231–1207 | “T. whippelii” |

Ambiguous base symbols indicate the presence of the following deoxynucleotides at equivalent ratios: B = C, G, and T; D = A, G, and T; H = A, C, and T; M = A and C; N = A, C, G, and T; R = A and G; Y = C, T, and U.

Position according to the corresponding E. coli sequence (GenBank accession no. X07850).

Primer derived from bacterial consensus regions according to GenBank/EMBL searches.

Primer derived from the sequence of “T. whippelii” determined in this work.

FIG. 1.

Primers and amplification systems used to analyze partial hsp65 genes of “T. whippelii” and “C. aquaticum.” The positions and expected product sizes are given according to the E. coli reference sequence (accession no. X07850).

Restriction enzyme analysis.

Based on the determined 620-bp sequence of the hsp65 gene of “T. whippelii,” endonuclease XhoI (Roche Diagnostics) was selected for the characterization of PCR-amplified fragments by using the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) software package version 8.1 (University of Wisconsin, Madison) and the command mapsort. XhoI is an endonuclease with a unique restriction pattern for the “T. whippelii” fragment amplified. The enzyme is supposed not to cut the corresponding fragment of gram-negative bacteria and to have a different restriction pattern for other actinobacteria. Reamplification products (system 5) were purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Samples (3 μl each) were added to 5 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 1 mM EDTA [pH 8]) and 1 μl of endonuclease XhoI (10 U in buffer H; Roche Diagnostics). Digestion was performed at 37°C overnight. The undigested (2-μl) and digested (3-μl) products were electrophoresed on a 3% agarose gel (2% NuSieveGTPAgarose [FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine] and 1% UltraPure agarose [Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland]), stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed under UV light.

Cloning and plasmid preparation of the “T. whippelii” products.

Products of “T. whippelii” obtained with amplification systems 2 and 3 were ligated into plasmid vector pCR 2.1 and cloned in E. coli INVaF′ cells as described in the instruction manual of the Original TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands). Clones negative for β-galactosidase activity and positive for insert 2 (pTWhsp-1) or insert 3 (pTWhsp-2) by PCR were selected. In addition, a plasmid (pTWhsp-3) containing an insert corresponding to the hsp gene fragment flanked by primers uni-f and hgc-r was constructed. After overnight culture in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth containing 50 μg of ampicillin per ml, plasmid DNA was extracted using DNA binding columns as outlined in the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit protocol (QIAGEN).

Sequence analysis.

PCR products purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN) were sequenced in both directions using the Thermo Sequenase Kit with 7-deaza-dGTP (Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, England) followed by analysis on an ALFexpress DNA Sequencer (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). Four individual “C. aquaticum” amplicons (system 1 [Fig. 1]), eight hsp65-positive clinical specimens (system 5), and five individual clones of each plasmid with inserts 2 and 3, respectively, were analyzed. The sequencing reaction was performed using the appropriate 5′ fluorescence-labeled primers (uni-f or uni-r1 for “C. aquaticum” amplicons, M13 forward or M13 reverse for plasmid DNA, whipp-frw2 or whipp-rev for the amplicons of the clinical specimens). Cycling with M13 primers was done according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). Sequencing conditions for primers uni-f or uni-r1 and whipp-frw2 or whipp-rev were as described above for the amplification of “C. aquaticum” and clinical specimens, except for an initial denaturation step of only 5 min. Raw sequencing data were processed automatically with ALFwin version 1.1 (Pharmacia Biotech).

Sequence comparisons.

The sequences of “T. whippelii” and “C. aquaticum” were compared to entries in GenBank/European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) databases using the GCG software package version 8.1. Comparisons were performed on the amino acid level using the command BESTFIT as described in the GCG program manual.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the “T. whippelii” and “C. aquaticum” hsp65 sequences determined in this study are AF184091 and AF184092, respectively.

RESULTS

Amplification, cloning, and sequencing of a part of the hsp65 gene.

No band of the expected size (654 bp) was visible on the agarose gel when DNA extracted from the heart valve was amplified with broad-spectrum PCR system 1. However, “C. aquaticum” showed the expected band. With system 2, bands of the expected size (332 bp) were visible with DNA extracted from both the heart valve and “C. aquaticum.” Water and human DNA remained negative. The PCR product of “T. whippelii” obtained with system 2 was cloned and sequenced, whereas the PCR products of “C. aquaticum” obtained with system 1 were sequenced without cloning. From these sequences, the “T. whippelii”-specific primer whipp-f was derived and then used in combination with primer hgc-r. With this system 3, direct amplification of heart valve DNA showed only a very weak band which was not the expected size (approximately 300 bp instead of 385 bp). However, nested amplification with system 1 followed by system 3 showed the expected 385-bp band, while water and human DNA remained negative. This PCR product of “T. whippelii” was also cloned and sequenced.

Analysis of the two “T. whippelii” plasmid inserts revealed an identical overlapping fragment of 95 nucleotides between primers whipp-f and uni-r2 (Fig. 1). The entire sequence determined spans 620 nucleotides, which corresponds to the 623 nucleotides between positions 668 and 1290 of the E. coli sequence with accession number X07850 (gram-positive species lack a single amino acid at nucleotide positions 927 to 929 compared to the corresponding E. coli groEL sequence) (11). The “C. aquaticum” hsp65 sequence determined comprises 540 nucleotides corresponding to positions 729 to 1271 (543 nucleotides) of the E. coli groEL sequence. For both species, the corresponding amino acid sequences were deduced and compared to those of related bacteria. “T. whippelii” Hsp65 showed similarities of 87.8% to Hsp65 of “C. aquaticum,” 86.7% to Hsp65 of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (accession number X74518), 86.1% to the 65-kDa antigen of Mycobacterium leprae (accession number M14341), 86.7% to GroEL2 of Streptomyces albus (accession number M76658), 87.8% to Hsp60 of Tsukamurella tyrosinosolvens (accession number U90204), and 70.0% to GroEL of E. coli (accession number X07850).

“T. whippelii”-specific PCR.

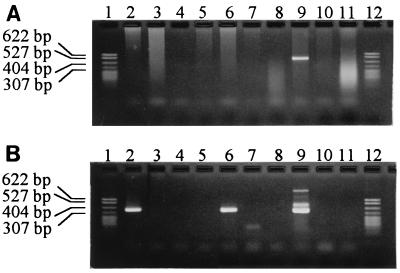

“T. whippelii”-specific primers whipp-frw1, whipp-frw2 and whipp-rev (Table 2) were derived from the above determined nucleotide sequences. DNA extracts from clinical specimens were then amplified with system 4 followed by seminested reamplification with system 5 (Fig. 2). When reamplification was done with 30 cycles, all 17 specimens previously shown to harbor “T. whippelii” 16S rDNA showed the expected reamplification product of 357 bp on the agarose gel. Three of these specimens had an additional band of approximately 500 bp, which corresponds to the primary amplification product. No products were obtained for all negative controls including the 33 negative patient specimens, E. coli, human DNA, and water. Reamplification with 40 cycles again showed a positive result for all 17 specimens previously shown to harbor “T. whippelii” 16S rDNA, whereas E. coli, human DNA, and water always remained negative. However, 3 of the 33 negative patient specimens now showed a very weak band on the agarose gel.

FIG. 2.

Detection of the “T. whippelii” hsp65 gene by PCR directly from representative human clinical specimens. Amplification using “T. whippelii”-specific primers whipp-frw1 and whipp-rev (A), generating a 500-bp product, followed by reamplification using “T. whippelii”-specific primers whipp-frw2 and whipp-rev (B), generating a 357-bp product. Lanes 2, 6, and 9, specimens from patients positive for “T. whippelii” hsp65 amplicons; lanes 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10 and 11, specimens from patients negative for “T. whippeli” hsp65 DNA; lanes 1 and 12, molecular size markers (MspI digestion of pBR322 DNA; fragment sizes from top to bottom are 622, 527, 404, 307, and ≤240 bp).

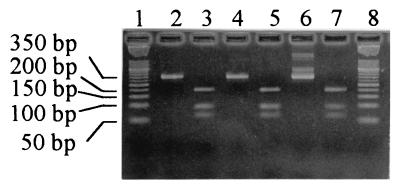

Restriction enzyme and sequence analyses of PCR products.

All reamplification products except for one from a control patient that became very weakly positive only after 40 reamplification cycles were digested with XhoI. All restriction patterns were identical and yielded the three expected fragments of 202, 92, and 63 bp on the agarose gel (Fig. 3). PCR products from 8 of the 17 patients listed in Table 1 representing all three previously described ITS types (12) and including one from patient 16 from whom the reference sequence had been derived were sequenced. The amplicon of patient 16 perfectly matched the reference sequence (GenBank accession no. AF184091). Five amplicons (2 ITS type 1 and 3 ITS type 2) were identical with the reference sequence except for an A instead of a G at position 232. The amplicons of both ITS type 3 patients differed significantly from the reference sequence (Table 3).

FIG. 3.

Representative XhoI restriction patterns of PCR-amplified sequences of the hsp65 gene of “T. whippelii.” Lanes 2, 4, and 6, undigested reamplification products of patients positive for “T. whippelii” hsp65 amplicons; lanes 3, 5, and 7, the corresponding XhoI-digested reamplification products; lanes 1 and 8, molecular size marker XIII (50-bp ladder; Roche Diagnostics).

TABLE 3.

Differences in partial hsp65 sequences of eight “T. whippelii”-positive patients

DISCUSSION

Despite recent success in culturing “T. whippelii” (15, 20), the clinical suspicion of Whipple's disease is usually confirmed by periodic acid-Schiff staining of inclusions in macrophages or by electron microscopy showing the characteristic trilamellar membrane of “T. whippelii” (6). When PCR systems targeting parts of the 16S rDNA were established, it became clear that molecular tests are significantly more sensitive than histopathology for intestinal and extraintestinal specimens (1, 4, 10, 18). On the other hand, DNA of Whipple's disease bacilli was also found in duodenal tissue specimens from biopsies, gastric juice, and saliva specimens of patients without Whipple's disease (7, 22; Dutly et al., submitted). Because the 16S rDNA is rather conserved and therefore not suitable for the identification and differentiation of closely related species (19) or for the investigation of intraspecies variation, the 16S-23S ITS has been chosen as a more variable target (12). Based on this region, three different “T. whippelii” ITS types have been found by sequence analysis, single-strand conformation polymorphism, and type-specific PCR.

We have looked at the more variable hsp65 gene of “T. whippelii” not only to confirm previous findings with a target entirely different from the rRNA operon but also because this gene might prove useful for the production of a recombinant antigen to be used in a serodiagnostic assay. Analysis of the hsp65 gene has previously been used for the identification and differentiation of various mycobacteria (21, 23). Based on PCR, restriction fragment analysis, and sequencing of the hsp65 gene and the ITS sequence, Richter et al. (17) described a new subspecies of Mycobacterium kansasii. In this study, we have amplified, cloned, and sequenced two overlapping fragments of the hsp65 gene directly from the heart valve of a patient with confirmed Whipple's endocarditis. Based on the sequence determined, a specific seminested PCR was developed and evaluated with clinical specimens of patients previously shown to harbor “T. whippelii” DNA by PCR targeting the 16S rDNA. In addition, PCR fragments of some patients were sequenced to assess the variability of heat shock proteins.

Initial attempts to amplify a 654-bp fragment with system 1 failed. However, amplification of a smaller fragment (332 bp, system 2) with the same DNA showed the expected band, confirming that amplification of small fragments results in a higher sensitivity (1). The sequence derived from the cloned fragment was then used to design primer whipp-f which is considered “T. whippelii” specific. This primer, in combination with the actinobacterium-specific primer hgc-r (system 3), allowed the amplification of a 385-bp fragment. This fragment was also cloned and sequenced. As expected, the two fragments overlapped by 95 nucleotides, indicating that both are indeed derived from the same organism. This is in agreement with previous amplifications of the same specimen by broad-range PCR targeting the 16S rRNA gene that had suggested the presence of a single type of organism (9).

The “T. whippelii”-specific seminested PCR assay designed on the basis of the partial hsp65 gene sequence determined (system 4 followed by system 5) revealed a sensitivity of 100% compared to the amplification of a 16S rRNA gene fragment irrespective of the number of cycles used for reamplification (Table 1). No false-positive results were observed with 30 reamplification cycles. Upon reamplification with 40 cycles, 3 of 33 negative-control specimens became positive. However, one of these three specimens, a cerebrospinal fluid specimen from a patient with Whipple's disease had been referred to us as being PCR positive. Thus, this specimen may be considered a true positive which gave a false-negative result by the 16S rDNA PCR rather than false positive by the hsp65 assay. This result suggests that the hsp65 PCR might be somewhat more sensitive than the 16S rDNA PCR. The other two presumably false-positive samples were duodenal tissue samples biopsied from two men aged 37 and 38 referred for elective gastroscopy without clinical signs of Whipple's disease (7). In view of the fact that carriage of “T. whippelii” in such patients does not seem uncommon, it remains to be shown whether these two specimens are true false positives related to carryover contamination or whether they also represent carriage that has not been detected by 16S rDNA-based PCR due to a somewhat lower sensitivity of that assay. However, for the time being, reamplification for 30 cycles seems superior to reamplification for 40 cycles.

The specificity of the “T. whippelii”-specific PCR assay was further assessed by digesting amplicons with XhoI in order to confirm that the amplified products indeed showed the restriction pattern which, according to available hsp65 sequences of other organisms, is unique to “T. whippelii”. The expected fragments were obtained for all 17 reamplification products from specimens known to harbor “T. whippelii” 16S rDNA, for one false-positive specimen, and for the specimen referred to us as being positive. The amplicon from the second false-positive specimen was too weak for further analysis. Based on the available data, it cannot be decided whether the false-positive results are due to laboratory contamination, to the existence of a closely related organism with a similar hsp65 gene, or to the presence of very small numbers of “T. whippelii” that can be detected only after reamplification for 40 cycles as suggested by the one presumably positive sample that gave negative results by all other assays. We conclude that amplification of the hsp65 gene is a sensitive and specific approach for the detection of “T. whippelii” in clinical specimens.

To evaluate the homogeneity of hsp65 sequences among different “T. whippelii” strains, 8 of the 17 true-positive amplicons were sequenced. The fact that the specimen of patient 16 (Table 1) perfectly matched the reference sequence was not surprising, because the reference sequence deposited in the database had been derived from this patient. However, one minor difference was observed for five other specimens representing ITS types 1 and 2, while considerable differences were found for the two specimens of ITS type 3 (Table 3). These sequence variations indicate that the positive results are not the result of amplicon carryover. None of the mutations affected the corresponding amino acid sequences, indicating that the Hsp65 of “T. whippelii” is conserved and might thus provide a suitable antigen for a future serodiagnostic assay. Specific antibody responses against Hsp65 have previously been reported for Chlamydia trachomatis (3) and Mycobacterium leprae (24) which are, like “T. whippelii,” intracellular bacteria. In addition, our data confirm that “C. aquaticum” is indeed the closest known relative of “T. whippelii” as has previously been suggested based on comparative 16S rDNA analysis (14).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 32-50790.97) to M. Altwegg.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altwegg M, Fleisch-Marx A, Goldenberger D, Hailemariam S, Schaffner A, Kissling R. Spondylodiscitis caused by Tropheryma whippelii. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1996;126:1495–1499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brändle M, Ammann P, Spinas G A, Dutly F, Galeazzi R L, Schmid C, Altwegg M. Relapsing Whipple's disease presenting with hypopituitarism. Clin Endocrinol. 1999;50:399–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerrone M C, Ma J J, Stephens R S. Cloning and sequence of the gene for heat shock protein 60 from Chlamydia trachomatis and immunological reactivity of the protein. Infect Immun. 1991;59:79–90. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.79-90.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dauga C, Miras I, Grimont P A. Strategy for detection and identification of bacteria based on 16S rRNA genes in suspected cases of Whipple's disease. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:340–347. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-4-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobbins W O., III . Whipple's disease. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobbins W O., III The diagnosis of Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:390–392. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502093320611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehrbar H U, Bauerfeind P, Dutly F, Koelz H R, Altwegg M. PCR-positive tests for Tropheryma whippelii in patients without Whipple's disease. Lancet. 1999;353:2214. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01776-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goh S H, Potter S, Wood J O, Hemmingsen S M, Reynolds R P, Chow A W. HSP60 gene sequences as universal targets for microbial species identification: studies with coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:818–823. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.818-823.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldenberger D, Künzli A, Vogt P, Zbinden R, Altwegg M. Molecular diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis by broad-range PCR amplification and direct sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2733–2739. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2733-2739.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gubler J G H, Kuster M, Dutly F, Bannwart F, Krause M, Vögelin H P, Garzoli G, Altwegg M. Whipple endocarditis without gastrointestinal disease: report of four cases. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:112–116. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-2-199907200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta R S. Evolution of the chaperonin families (Hsp60, Hsp10 and Tcp-1) of proteins and the origin of eukaryotic cells. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinrikson H P, Dutly F, Nair S, Altwegg M. Detection of three different types of “Tropheryma whippelii” directly from clinical specimens by sequencing, single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis and type-specific PCR of their 16S-23S ribosomal intergenic spacer region. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:1701–1706. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-4-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinrikson H P, Dutly F, Altwegg M. Evaluation of a specific nested PCR targeting domain III of the 23S rRNA gene of “Tropheryma whippelii” and proposal of a classification system for its molecular variants. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:595–599. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.595-599.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maiwald M, Ditton H J, von Herbay A, Rainey F A, Stackebrandt E. Reassessment of the phylogenetic position of the bacterium associated with Whipple's disease and determination of the 16S-23S ribosomal intergenic spacer sequence. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:1078–1082. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raoult D, Birg M L, La Scola B, Fournier P E, Enea M, Lepidi H, Roux V, Piette J-C, Vandenesch F, Vital-Durand D, Marrie T J. Cultivation of the bacillus of Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:620–625. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Relman D A, Schmidt T M, MacDermott R P, Falkow S. Identification of the uncultured bacillus of Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:293–301. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207303270501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richter E, Niemann S, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Hoffner S. Identification of Mycobacterium kansasii by using a DNA Probe (AccuProbe) and molecular techniques. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:964–970. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.964-970.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rickman L S, Freeman W R, Green W R, Feldman S T, Sullivan J, Russack V, Relman D A. Brief report: uveitis caused by Tropheryma whippelii (Whipple's bacillus) N Engl J Med. 1995;322:363–366. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502093320604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth A, Fischer M, Hamid M E, Michalke S, Ludwig W, Mauch H. Differentiation of phylogenetically related slowly growing mycobacteria based on 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:139–147. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.139-147.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoedon G, Goldenberger D, Forrer R, Gunz A, Dutly F, Höchli M, Altwegg M, Schaffner A. Deactivation of macrophages with interleukin-4 is the key to the isolation of Tropheryma whippelii. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:672–677. doi: 10.1086/514089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steingrube V A, Wilson R W, Brown B A, Jost K C, Jr, Blacklock Z, Gibson J L, Wallace R J., Jr Rapid identification of clinically significant species and taxa of aerobic actinomycetes, including Actinomadura, Gordona, Nocardia, Rhodococcus, Streptomyces, and Tsukamurella isolates, by DNA amplification and restriction endonuclease analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:817–822. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.817-822.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Street S, Donoghue H D, Neild G H. Tropheryma whippelii DNA in saliva of healthy people. Lancet. 1999;354:1178–1179. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)03065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Telenti A, Marchesi F, Balz M, Bally F, Böttger E C, Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:175–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkinson K A, Katoch K, Sengupta U, Singh M, Sarin K K, Ivanyi J, Wilkinson R J. Immune responses to recombinant proteins of Mycobacterium leprae. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1034–1037. doi: 10.1086/314669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson K H, Blitchington R, Frothingham R, Wilson J A P. Phylogeny of the Whipple's disease-associated bacterium. Lancet. 1991;338:474–475. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90545-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zügel U, Kaufmann S H E. Role of heat shock proteins in protection from and pathogenesis of infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:19–39. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]