Abstract

Cadmium (Cd) is a well-known lung carcinogen. However, the mechanism of Cd carcinogenesis remains to be clearly defined. Cd has been shown to act as a weak mutagen, suggesting that it may exert tumorigenic effect through nongenotoxic ways, such as epigenetic mechanisms. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) refer to RNA molecules that are longer than 200 nucleotides in length but lack protein-coding capacities. Regulation of gene expressions by lncRNAs is considered as one of important epigenetic mechanisms. The goal of this study is to investigate the mechanism of Cd carcinogenesis focusing on the role of lncRNA dysregulations. Cd-induced malignant transformation of human bronchial epithelia BEAS-2B cells was accomplished by a 9-month low-dose Cd (CdCl2, 2.5 µM) exposure. The Cd-exposed cells formed significantly more colonies in soft agar, displayed cancer stem cell (CSC)-like property, and formed tumors in nude mice. Mechanistically, chronic low-dose Cd exposure did not cause significant genotoxic effects but dysregulated lncRNA expressions. Further Q-PCR analysis confirmed the significant upregulation of the oncogenic lncRNA DUXAP10 in Cd-transformed cells. DUXAP10 knockdown in Cd-transformed cells significantly reduced their CSC-like property. Further mechanistic studies showed that the Hedgehog pathway is activated in Cd-transformed cells and inhibition of this pathway reduces Cd-induced CSC-like property. DUXAP10 knockdown caused the Hedgehog pathway inactivation in Cd-transformed cells. Furthermore, Pax6 expression was upregulated in Cd-transformed cells and Pax6 knockdown significantly reduced their DUXAP10 levels and CSC-like property. In summary, these findings suggest that the lncRNA DUXAP10 upregulation may play an important role in Cd carcinogenesis.

Keywords: cadmium, cancer stem cell-like property, long noncoding RNA, DUXAP10, Hedgehog pathway, Pax6

Cadmium (Cd) is a naturally occurring toxic metal. It has been widely used in industries for productions of, for example, batteries, cell phones, and computer circuit boards. Occupational exposure via inhalation is the major route for the first-line workers during these manufacturing processes. Several studies have revealed elevated levels of Cd contamination in the workers’ blood and urine (Akerstrom et al., 2013; Baloch et al., 2020). For the general population, the Cd exposure could occur via consuming Cd-contaminated water or food or cigarette smoking. With its long biological half-life of 15–20 years, Cd toxicity is considered cumulative and Cd exposure poses a great health risk. Cd is listed as a class I carcinogen by International Agency for Research on Cancer. It is a known lung carcinogen (Huff et al., 2007). Many studies have also reported its association with other types of cancer, including breast cancer (Song et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2018), liver cancer (Ali et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2015), prostate cancer (Achanzar et al., 2001; Dasgupta et al., 2020; Golovine et al., 2010), melanoma (Venza et al., 2015), and lymphoma (Yuan et al., 2013). However, the exact carcinogenic mechanism of Cd remains unclear.

Cd has only minor genotoxicity, especially at low dose, and has been considered a weak mutagen (Misra et al., 1998; Waalkes, 2000). It has been proposed that Cd exerts its oncogenic effect more likely through epigenetic nongenotoxic ways. Regulations of gene expression by noncoding RNAs such as microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are considered as important epigenetic mechanisms (Dykes and Emanueli, 2017; Humphries et al., 2016; Mercer and Mattick, 2013; Wang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2019b). LncRNAs refer to RNA molecules that are longer than 200 nucleotides in length but lack protein-coding capacities. Studies have shown that lncRNA dysregulations are critically involved in cancer initiation and progression (Chi et al., 2019; Li et al., 2016). Although emerging evidence suggests that lncRNA dysregulations may play important roles in environmental carcinogenesis (Wang et al., 2021), how Cd exposure dysregulates lncRNA expression and whether lncRNA dysregulations play a role in Cd carcinogenesis remain largely unknown.

Although the mortality rate of lung cancer has dropped since 2017 due to improved treatment, lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related death in U.S. males and females (Siegel et al., 2020, 2021). Lung cancer cells can metastasize at early stage even before lung cancer can be detected, which complicates the prognosis, diagnosis, and the therapy. Eventually the hindered therapeutic efficiency leads to low overall survival (OS) rate of lung cancer patients (Cheng et al., 2021; Cui et al. 2021.; Rudin et al., 2021). The presence of cancer stem cells (CSCs) has been considered the driven force for such metastasis and tumor relapse after the therapy (Perona et al., 2011). Previously, others and our studies have reported that exposure to metal carcinogens induces CSC-like properties (Chandrasekaran et al., 2020; Clementino et al., 2020; Dai et al., 2017; Qu et al., 2012; Tokar et al., 2010a,b; Wang et al., 2016, 2018, 2019b). However, the mechanism of how metal carcinogen exposure produces CSC-like cells has not been well understood. In the present study, human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) were exposed to Cd at a low dose for 9 months, mimicking chronic exposure of heavy metal to humans. The goal of this study is to investigate the mechanism of Cd carcinogenesis focusing on the role of lncRNA dysregulations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and chemical treatments

Immortalized human bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cell line was purchased from America Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia). BEAS-2B cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Thermo Fisher, Massachusetts) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P/S).

Cell transformation by chronic exposure to cadmium (CdCl2)

BEAS-2B cells were first treated with different doses of CdCl2 (2.5, 5, and 10 µM) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h. The morphology of control- and Cd-treated cells were observed under the microscope to determine the cytotoxic effect of Cd. It was found that 5 and 10 µM of CdCl2 had toxic effects on the viability and proliferation of BEAS-2B cells, whereas 2.5 µM of CdCl2 had no obvious cytotoxic effects. This dose was then chosen for chronic cell transformation experiment following our published protocol (Wang et al., 2011). Briefly, BEAS-2B cells were continuously exposed to a vehicle control (H2O) or 2.5 µM of CdCl2. When reaching about 80%–90% confluence after exposure, cells were subcultured. Cd was freshly added to cells each time after overnight cell attachment. Soft agar colony formation assay was performed after every 4-week Cd exposure to assess cell transformation. This process was repeated for 38 weeks.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was extracted from passage-paired BEAS-2B control and Cd-transformed cell pellets by the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, California). The RNA samples were then sent to Arraystar Inc. (Rockville, Maryland) for lncRNA microarray analysis. The array raw data was further analyzed by Arraystar Inc. and the microarray raw data were deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)’s data repository (access ID: GSE175472).

Soft agar colony formation assay

The soft agar colony formation assay was carried out in 60 mm cell culture dishes for each group as described previously (Yang et al., 2005). Briefly, cultured cells were collected by trypsinization and suspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS at density of 0.25 × 104 cells/ml. Normal melting point agarose (4 ml of 0.6% agarose in DMEM containing 10% FBS) was placed into each 60 mm cell culture dish as the bottom layer. After solidification, 4 ml of cell mixture consisting of 2 ml of cell suspension and 2 ml of 0.8% low melting point agarose in DMEM containing 10% FBS were poured over the bottom layer agarose. After solidification of the upper layer, 3 ml of DMEM containing 10% FBS was added, and dishes were incubated at 37°C in cell incubator with 5% CO2. After 4-week incubation, colonies formed in the agarose dishes were stained with 0.003% crystal violet, photographed, and counted.

Suspension culture spheroid formation assay

The spheroid formation assay was performed following the published protocol (Dontu et al., 2003) with minor modifications. Briefly, single cells were plated in ultralow attachment 48-well culture plates (Corning, New York) at a density of 2 × 103 cells per well suspended in serum-free DMEM containing human recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (20 ng/ml) (R&D, Minneapolis, Minnesota), human recombinant epidermal growth factor (20 ng/ml) (R&D, Minneapolis, Minnesota), B27 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California), and heparin (4 µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich). Plates were incubated at 37°C in cell incubator with 5% CO2. Spheres > 50 µm were viewed, photographed, and counted under a phase-contrast microscope after 10-day culture. For the secondary sphere formation assay, the primary spheres were first collected and dissociated by trypsin. The single cells were then plated in ultralow attachment culture plates (Corning, New York) at a density of 1 × 103 cells per well suspended in serum-free DMEM containing the same nutritional supplements as for the primary sphere culture.

Nude mouse xenograft tumorigenesis study

Passage-matched control and Cd-transformed cells (1.5 × 106 cells in 0.1 ml of 1:1 growth factor-reduced Matrigel and serum-free DMEM) were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of female nude mice (Nu/Nu, Charles River Laboratories, 10 mice in each group). Animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions, and animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All mice were euthanized 12 weeks after injection, and the xenograft tumors were harvested and photographed.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed using lysis buffer following our published protocol (Wang et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2006). The cell lysates were then applied to the bicinchoninic acid assay (Bio-Rad) to determine protein concentrations, followed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (20–30 µg of protein/lane). The separated proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (PVDF, Millipore, Massachusetts). Five percent milk in PBS was applied for the blocking step before primary antibody incubation. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-KLF4, anti-KLF5, anti-Nanog, anti-GLI1, anti-SHH, anti-PTCH2, anti-Pax6 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, Massachusetts) (dilution 1:1000), anti-phospho-histone H2A.X (Ser139) (γH2AX) (dilution 1:1000), and anti-β-actin (Millipore Sigma, St Louis, Missouri) (dilution 1:8000). After overnight primary antibody incubation at 4°C, the membranes were washed and then incubated with HRP-conjugated antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Images were developed by Amersham Imager 680 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Massachusetts). The collected results were quantified by ImageJ software and presented as ratio of the specific protein band density to the β-actin band density.

Kaplan-Meier plotter survival analysis

The Kaplan-Meier (KM) plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis/, last accessed July 20, 2021) was utilized to analyze the correlation between levels of Pax6/DUXAP10 and OS/recurrence-free survival (RFS) in 1144 lung cancer patients.

Flow cytometry analysis of CD133+ cells

Cells were detached from the culture dishes with Versene solution (Gibco). After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in DMEM with 2% FBS and 1% PS. A portion (0.25 µg) of PE-anti CD 133 (Promini-1) (Biolegend, California) was added to the cells. After 40 min of incubation, cells were washed and stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylinodole (DAPI). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting was carried out by using the flow cytometer BD LSR II (Becton Dickinson). Raw data were analyzed by using Flowjo software (Becton Dickinson).

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA extraction was performed by using the TRIzol reagent following the manufacturer’s instruction (Invitrogen, California). Quality and quantity of extracted RNA was determined by NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, Massachusetts) before applying to TaqMan gene expression assays. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed by ABI QuantStudio 3 qPCR System (Applied Biosystems). The 2-ΔΔct analysis method was utilized to quantify relative RNA expression levels of each gene, with human 18S RNA as the internal control.

Immunofluorescence staining of cultured cells

Cells were seeded on cover glass placed in 6-well plates and cultured for 48 h (including the inhibitor treatment or RNA interference) before the antibody staining. For the staining process, cells were first washed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. Cell permeabilization was performed by the use of 1% Triton X-100 in PBS and incubated for 1.5 min at room temperature, followed by blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min. The primary antibodies, phospho-histone H2A.X (Ser139) (γH2AX) (Santa Cruz) and GLI1 (Cell Signaling Technology), were diluted in PBS with 1% BSA at a ratio of 1:200. Following the primary antibody incubation for overnight at 4°C, cells were washed before the secondary antibody incubation (Alexa 546 goat antimouse/rabbit IgG, 1:300, Invitrogen). After 1 h of incubation at room temperature, cells were washed again and stained with DAPI for 10 min before mounting. IF staining pictures taken under a Nikon fluorescent microscope are presented as the overlaid images of γH2AX or GLI1 staining in red fluorescence with nuclear DAPI staining in blue fluorescence. The image overlay was done using Nikon NIS-Elements software.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation-qPCR assay

The chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR assay was utilized to detect the abundance of transcription factor Pax6 in the promoter region of DUXAP10. The ChIP assay was performed by using the Pierce Agarose ChIP kit (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde, followed by Micrococcal Nuclease digestion. The fragmented DNA samples were applied to immunoprecipitation with 5 µg of anti-Pax6 antibody (no. sc-32766, Santa Cruz) per reaction. The precipitated DNA was then examined by qPCR for the enrichment of the target protein at the promoter region of interest. The percent input method was adopted to present the ChIP-qPCR results.

RNA interference by transient transfection

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates or 60 mm dishes (Corning) 24 h before transfection in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and 1% P/S. Before transfection, the culture medium was refreshed with serum-free DMEM. Small-interfering RNA (siRNA) was then transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 4 h incubation, an equal volume of DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% P/S was added to the plates/dishes. The cells would be ready for further analysis in 48 h.

Plasmid construction

The sequence of DUXAP10 was submitted to GenScript Biotech (New Jersey) for the synthesis and subcloning of DUXAP10 into the vector pBluescript II SK(+). The DUXAP10 antisense (DUXAP10-AS) fragment was the PCR product using the DUXAP10 plasmid as the template. The amplified DUXAP10-AS was digested with restriction enzymes KpnI and XhoI (BioLabs, New England) and then subcloned into vector pBluescript II SK(+). Both plasmids-bearing sense and antisense DUXAP10 were introduced into competent cells DH5α, followed by plasmid extraction using ZymoPURE II Plasmid Midiprep Kit (Zymo Research). The extracted plasmids from DH5α-DUXAP10 -sense and -antisense strains were evaluated by restriction enzyme PstI (BioLabs, New England) before proceeding to RNA pulldown assay.

RNA pulldown assay

The plasmids pBluescript-DUXAP10 and pBluescript-DUXAP10-AS were linearized by restriction enzyme EcoRI-HF (BioLabs, New England), followed by in vitro transcription for synthesis of biotinylated RNA and RNA pulldown described in the study of Feng et al. (2014). In brief, 4 µg of linearized plasmids was added to the mixture of 10× Biotin mix (Roche), T7 RNA polymerase (Promega), 5× Transcription buffer (Promega), and DNAse/RNase-free water, incubated at 37°C for 3 h, and proceeded to DNase I digestion at 37°C for 15 min. Biotinylated RNA was purified using G-50 Sephadex Columns (Roche). RNA pulldown was then carried out by incubating 20 µg of the biotinylated RNA with total protein lysates from Cd-T cells on a rotator at 4°C for 1 h, followed by repeated washing and centrifugation steps. Finally, the precipitated protein-beads complexes were resuspended with protein-loading buffer and boiled for 10 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant containing the pulled-down proteins were applied to Western blot analysis.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses for the significance of differences in presented numerical data (mean ± SD) were carried out by testing different treatment effects using 2-tailed t tests for comparison of two data sets. A p value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

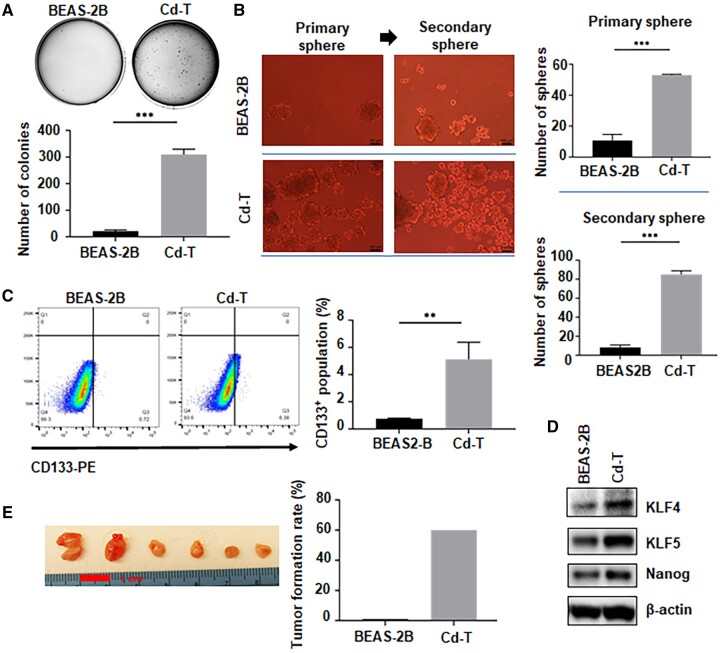

Chronic Low Dose of Cd Exposure Induces CSC-Like Property and Tumorigenesis

To establish a Cd-induced cell transformation model, we treated immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) to Cd at the concentration of 2.5 µM twice a week. The transformation process was monitored by the soft agar colony formation assay monthly. After 9 months of exposure, the Cd-treated cells displayed more than 50 times of colony formation, compared with the passage-matched control-treated cells (Figure 1A), suggesting that cell transformation by Cd was achieved. Meanwhile, Cd-induced cell transformation was further analyzed by determining the CSC-like property and tumorigenicity of Cd-exposed cells (Cd-T). The suspension culture sphere formation assay showed that Cd-T cells form significantly more suspension spheres than the passage-matched control cells (Figure 1B). Furthermore, the first-generation sphere cells from Cd-transformed cells formed significantly more secondary spheres (Figure 1B), demonstrating the self-renewal capacity of this distinct population within the transformed cells. CD133 (Prominin-1), a transmembrane glycoprotein, has been used as a CSC surface marker in many cancer types, including lung adenocarcinoma (Miyata et al., 2017). As shown in Figure 1C, the number of CD133-positive cells in Cd-transformed cells is 5 times more than that in control cells, providing another evidence that chronic Cd exposure induces CSC-like property. Moreover, Cd-transformed cells were further sorted into CD133 positive and negative populations and applied to suspension sphere formation. It was found that CD133+ cells displayed a much stronger sphere-forming capacity than the CD133- cells (Supplementary Figure 1), suggesting that CD133 could serve as one of the cell surface markers of the CSC-like population induced by chronic Cd exposure. Moreover, we further examined several stemness-related markers at their protein levels. Elevated expressions of KLF4, KLF5, and Nanog were observed in Cd-transformed cells (Figure 1D and Supplementary Figure 2). Because CSCs or CSC-like cells are considered as tumor initiating cells, we also determined the tumor forming capability of Cd-transformed cells. To study tumorigenic capacity of Cd-transformed cells, we injected Cd-T cells, as well as the passage-matched control group cells, into the right flank of nude mice. Comparing to the control group which had no tumor formed, 60% of tumor incidence in the Cd-T group was observed (Figure 1E). Together, these results demonstrated that long-term exposure to a low dose of Cd causes cell malignant transformation, along with the induction of CSC-like property and tumorigenesis.

Figure 1.

Chronic exposure to a low dose of Cd induces CSC-like property and tumorigenesis. A, Representative images of soft agar colonies formed from the passage-paired BEAS-2B cells and the Cd transformed BEAS-2B cells (Cd-T) (means ± SD, n = 3), ***p < .001. B, Representative images of the first and the second generation of suspension spheres formed from the passage-paired BEAS-2B cells and Cd-T cells. Scale bar: 100 µm. The bar graph represents the average numbers of the spheres formed in the repeated assays (means ± SD, n = 3), ***p < .001. C, Representative images of flow cytometry analysis of CD133 positive cells in the control BEAS-2B cells and Cd-T cells. The bar graph shows the average percentage of CD133+ population in each group (means ± SD, n = 3), **p < .01. D, Representative Western blot analysis images of stemness marker levels in the control BEAS-2B and Cd-T cells. E, Nude mouse xenograft tumorigenesis study as described in Materials and Method (n = 10).

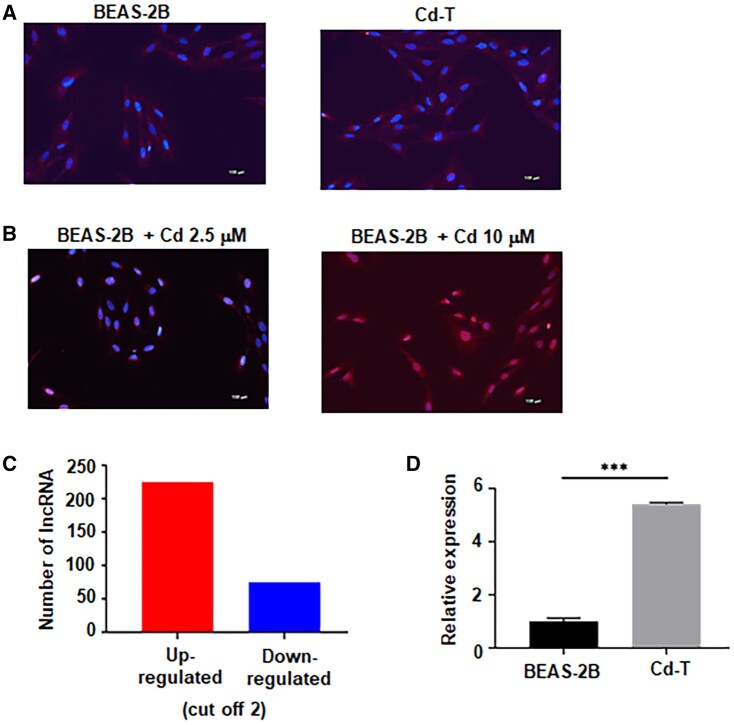

Chronic Exposure to a Low Dose of Cd Does Not Induce Significant DNA Damages, but Causes Long Noncoding RNA Dysregulations

Next, we set to determine the mechanism by which chronic low dose of Cd exposure induces CSC-like property. We first determined whether chronic low dose of Cd exposure causes a significant genotoxicity in BEAS-2B cells. We performed immunofluorescence (IF) staining to examine the presence of a DNA damage marker phospho-histone H2A.X (γH2AX) in passage-matched control BEAS-2B cells and Cd-T cells. Figure 2A shows that no significant amount of γH2AX is present in the control cells and Cd-transformed cells. We next determined the genotoxic effect of acute low and high doses of Cd exposure on control BEAS-2B cells. While treating control BEAS-2B cells with Cd 2.5 µM, no significant γH2AX formation was detected, treating control BEAS-2B cells with 10 µM of Cd significantly induced γH2AX formation (Figure 2B), indicating a large amount of DNA damages. These results suggested that the Cd exposure concentration of 2.5 µM is not genotoxic and that the cell malignant transformation could be the result of other nongenotoxic effects such as epigenetic modifications. To further determine the mechanism of Cd-inducing CSC-like property, we performed lncRNA microarray analysis and the results were deposited to the NCBI data repository (access ID: GSE175472). The lncRNA microarray results revealed that 225 lncRNAs were upregulated in Cd-T cells, whereas 75 were downregulated (with a cut-off of 2-fold changes) (Figure 2C). Among the upregulated lncRNAs, there were 4 lncRNAs identified as oncogenic by other studies (Supplementary Table 1) and the expression levels were 2.5 times or higher in Cd-transformed cells than the control cells: LUCAT1, LINC00473, HOTAIRM1, and DUXAP10 (Supplementary Figure 3). Further qPCR analysis confirmed the upregulation of the 4 oncogenic lncRNAs: DUXAP10 was upregulated around 5.6-fold, whereas HOTAIRM1 and LINC00473 were upregulated around 3-fold, and LUCAT1 was upregulated less than 2-fold. As DUXAP10 was confirmed with the highest expression level in Cd-transformed cells (Figure 2D), we decided to focus on DUXAP10.

Figure 2.

Chronic exposure to Cd does not induce significant DNA damage but cause long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) dysregulations. A, Representative IF staining overlaid images of γH2A.X in red fluorescence and DAPI in blue fluorescence from control BEAS-2B and Cd-T cells. Scale bar: 100 µm. B, Representative IF staining overlaid images of γH2A.X in red fluorescence and DAPI in blue fluorescence from the BEAS-2B treated with Cd 2.5 or 10 µM, respectively. Scale bar: 100 µm. C, Microarray result shows 225 lncRNA upregulated and 75 lncRNA downregulated (cut-off 2). D, Quantitative PCR analysis of the relative DUXAP10 level in control BEAS-2B and Cd-T cells. The RNA level in the Cd-T is expressed relative to control BEAS-2B cells (means ± SD, n = 3), ***p < .001.

Knockdown of DUXAP10 in Cd-T Cells Significantly Reduces Their CSC-Like Property

The lncRNA DUXAP10 has been shown oncogenic in various cancer models, including nonsmall cell lung cancer (Wei et al., 2017). Our bioinformatics analysis shown in Figure 3A demonstrated that its overexpression is associated with significantly worse OS for lung cancer patients, further confirming its oncogenic role in lung cancer. To perform functional studies, we knocked down DUXAP10 by siRNAs and the knockdown efficiency was around 50% (Figure 3B). After the knockdown, the stemness markers, which were shown upregulated in Cd-T cells decreased at the protein levels, including KLF4, KLF5, and Nanog (Figure 3C and Supplementary Figure 4). Furthermore, the number of suspension spheres formed by Cd-T cell with DUXAP10 knockdown dropped by 50%, compared with the Cd-T-control siRNA cells (Figure 3D). In addition, we examined the stem cell surface marker CD133 by the flow cytometry analysis. In Cd-T cells with DUXAP10 knockdown, CD133 positive population decreased 60% (Figure 3E). These results demonstrate the importance of DUXAP10 in maintaining CSC-like property of Cd-transformed cells.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of DUXAP10 in Cd-T cells significantly reduces their CSC-like property. A, Kaplan-Meier plotter survival analysis revealed negative correlation between DUXAP10 level and the overall survival rate, relapse-free survival rate in lung cancer patients. B, Quantitative PCR analysis of the relative DUXAP10 level in Cd-T cells transfected with control siRNA and the siRNA targeting DUXAP10. The RNA level in the Cd-T with DUXAP10 knockdown is expressed relative to the control group (means ± SD, n = 3), **p < .01. C, Representative Western blot images of stemness marker levels in Cd-T cells transfected with control siRNA or the siRNA targeting DUXAP10. D, Representative images of suspension spheres formed from Cd-T cells transfected with control siRNA or DUXAP10 siRNA. Scale bar: 100 µm. The bar graph represents the average numbers of the spheres formed in the repeated assays (means ± SD, n = 3), **p < .01. E, Representative images of flow cytometry analysis of CD133 levels in the Cd-T cells transfected with control siRNA or DUXAP10 siRNA. The bar graph shows the average percentage of CD133+ population in each group (means ± SD, n = 3), **p < .01.

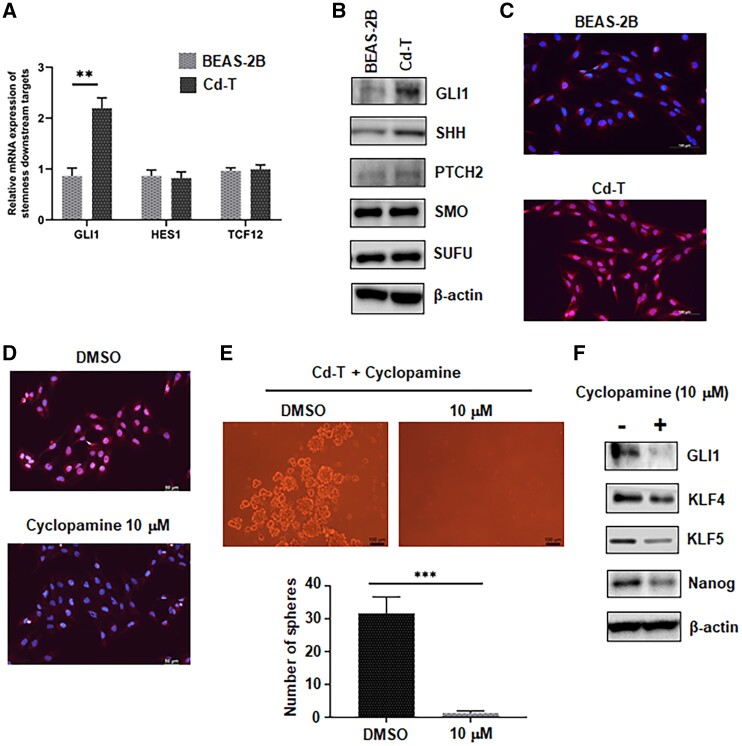

The Hedgehog Pathway Is Highly Activated in Cd-T Cells and Inhibition of This Pathway Reduces Their CSC-Like Property

As the above results revealed the induced CSC-like property in Cd-T cells, we next set to explore the pathways associated with this property. Downstream targets of 3 stemness-related pathways were screened first, including the Hedgehog pathway, Notch pathway, and Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 (GLI1) acts as the effector of the Hedgehog pathway and is also one of the downstream targets of this pathway. Transcription factor HES1 plays an important role during embryogenesis and is the downstream target of the Notch signaling pathway. The transcription factor 12 (TCF12) is one of important target genes of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. The qPCR results showed 2.3-fold increase in GLI1 expression, whereas the levels of HES1 and TCF12 showed no changes between the control cells and Cd-T cells (Figure 4A). Important proteins involved in the Hedgehog pathway were then checked by Western blot. We found upregulated levels of GLI1, protein-patched homolog 2 (PTCH), and Sonic hedgehog protein (SHH) in Cd-T cells, whereas the levels of Smoothened (SMO) and Suppressor of fused homolog (SUFU) remained unchanged between control and Cd-T cells (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure 5). Translocation of GLI1 from cytoplasm to nucleus is essential to activate the transcription of Hedgehog downstream target genes. Here, we checked the cellular localization of GLI1 in the control BEAS-2B and Cd-T cells by IF staining. In Cd-T cells, GLI1 is mostly localized in the nucleus as indicated by the pink color resulting from the overlapping of nuclear DAPI staining in blue and GLI1 staining in red (Figure 4C). On the contrary, in the BEAS-2B control cells, the nuclear color remained blue, which demonstrates no significant amount of GLI1 nuclear translocation (Figure 4C). Cyclopamine, an inhibitor of the Hedgehog pathway (Incardona et al., 1998), was then utilized to determine whether the Hedgehog pathway activity plays a critical role in the CSC-like property of Cd-T cells. IF staining showed no significant GLI1 nuclear translocation under the treatment of cyclopamine at 10 µM (Figure 4D). At the same time, treatment of 10 µM of cyclopamine abolished the sphere-forming capability of Cd-T cells (Figure 4E). Furthermore, protein levels of stemness markers KLF4, KLF5, and Nanog, as well as GLI1 in Cd-T cells, were downregulated by the cyclopamine treatment (Figure 4F and Supplementary Figure 6). Together, these results indicate that the Hedgehog pathway activity is essential in maintaining the CSC-like properties in Cd-T cells.

Figure 4.

The Hedgehog pathway is highly activated in Cd-T cells and inhibition of this pathway reduces their CSC-like property. A, Quantitative PCR analysis of the relative levels of GLI1, HES1, TCF12 mRNA in control BEAS-2B and Cd-T cells. The mRNA levels in the Cd-T are expressed relative to the control group (means ± SD, n = 3), **p < .01. B, Representative Western blot images of the levels of GLI1, SHH, PTCH2, SMO, SUFU in control BEAS-2B and Cd-T cells. C, Representative IF staining overlaid images of GLI1 in red fluorescence and DAPI in blue fluorescence from control BEAS-2B and Cd-T cells. Scale bar: 100 µm. D, Representative IF staining overlaid images of GLI1 in red fluorescence and DAPI in blue fluorescence from Cd-T cells treated with DMSO (vehicle control) and cyclopamine (10 µM), respectively. Scale bar: 100 µm. E, Representative images of suspension spheres formed from Cd-T cells treated with DMSO (vehicle control) or cyclopamine (10 µM), respectively. Scale bar: 100 µm. The bar graph represents the average numbers of the spheres formed in the repeated assays (means ± SD, n = 3), ****p < .0001. F, Representative Western blot images of the levels of GLI1, KLF4, KLF5, Nanog in Cd-T cells treated with DMSO (vehicle control) or cyclopamine (10 µM).

Knockdown of DUXAP10 Inactivates the Hedgehog Pathway in Cd-T Cells

We next determined whether DUXAP10 regulates the Hedgehog pathway activity in Cd-transformed cells. Results presented in Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure 7 show that knockdown of DUXAP10 leads to decreased levels of GLI1, SHH, and PTCH2 in the Cd-T cells. IF staining revealed no significant presence of GLI1 in the nucleus while DUXAP10 was knocked down (Figure 5B). These results suggest that DUXAP10 plays an important role in maintaining the Hedgehog signaling pathway activity in Cd-transformed cells. We then further determined how DUXAP10 may regulate the Hedgehog pathway activity. Modes of lncRNA actions in tumor cells could be: (1) mediating transcription by binding with proteins such as transcription factors; (2) acting as scaffold molecules to assemble protein complexes; (3) acting as a decoy or guide molecule to regulate functions of DNA, mRNA, and miRNA (Gao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019a; Zhang et al., 2019a). Though little evidence is currently available regarding the regulatory role of DUXAP10, the previous studies hinted a higher chance of DUXAP10 interacting with proteins (Wei et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2018). We next proceeded to predict the interaction between DUXAP10 and the proteins in the Hedgehog pathway by RPIseq (RNA-Protein Interaction Prediction, powered by Iowa State University). The prediction outcome indicated that the interaction probability between DUXAP10 and GLI1 is 0.9, whereas it is 0.7 between DUXAP10 and SHH (Supplementary Table 2). The RNA pulldown assay was then performed to determine the interactions between the lncRNA DUXAP10 and these proteins. The results showed that DUXAP10 sense strand binds to GLI1, with its antisense as the negative control (Figure 5C and Supplementary Figure 8). However, the RNA pulldown assay revealed no interaction between DUXAP10 and SHH (Figure 5C and Supplementary Figure 8). As the interaction of DUXAP10 and GLI1 was confirmed, we next study the impact of this interaction on GLI1 protein levels. Previously, a study suggested that destruction of GLI1 is regulated by proteosome degradation (Huntzicker et al., 2006). Here, we treated the cells with a proteosome inhibitor MG132 (10 µM), and observed increased levels of GLI1 in Cd-T cells (Figure 5D and Supplementary Figure 9), which confirmed that GLI1 protein levels could be regulated by the proteosome mechanism. MG132 (10 µM) treatment also increased GLI1 protein levels in the Cd-T with DUXAP10 knockdown (Figure 5D). Together, these results suggest that DUXAP10 may regulate the Hedgehog pathway activity through increasing the GLI1 protein stability.

Figure 5.

Knockdown of DUXAP10 inactivated the Hedgehog pathway in Cd-T cells. A, Representative Western blot images of the levels of GLI1, SHH, PTCH2 in Cd-T cells transfected with control siRNA or DUXAP10 siRNA. The assay was repeated, and similar results were obtained. B, Representative IF staining overlaid images of GLI1 in red fluorescence and DAPI in blue fluorescence from the Cd-T cells transfected with control siRNA or DUXAP10 siRNA. Scale bar: 100 µm. C, Representative Western blot images of the levels of GLI1 and SHH in the Cd-T protein lysates applied to DUXAP10-sense and DUXAP10-antisense biotinylated RNA pull down, respectively. D, Representative Western blot images of the level of GLI1 in Cd-T cells transfected with control siRNA or DUXAP10 siRNA and treated with 10 µM MG132 or a vehicle control DMSO, respectively.

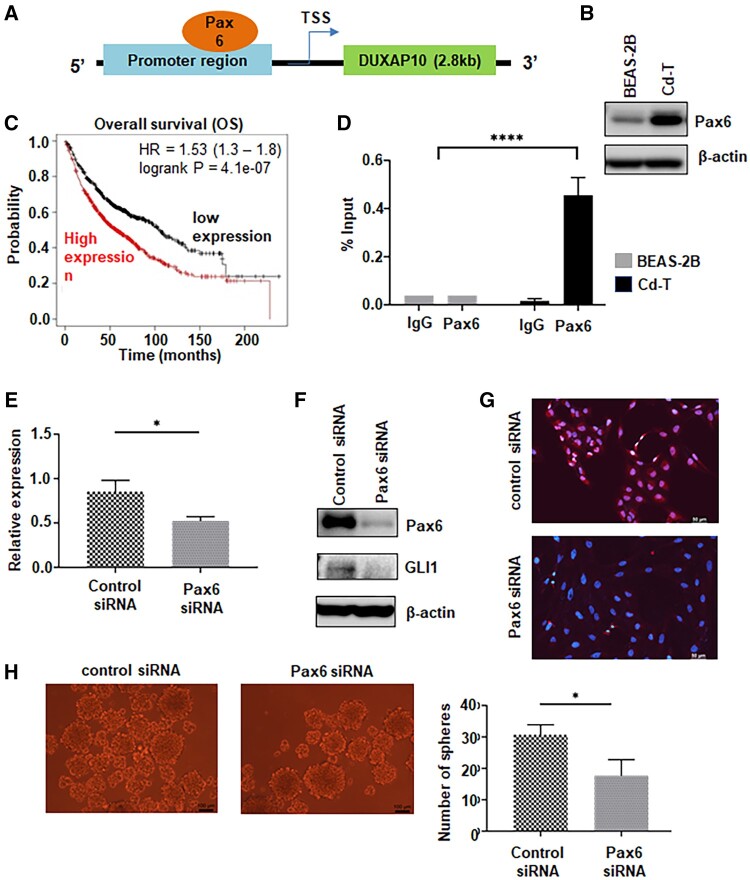

Chronic Cd Exposure Increases the Expression of Pax6 and Knockdown of Pax6 Reduces DUXAP10 Levels in Cd-T Cells

We next explored the mechanism of how the level of DUXAP10 is upregulated in Cd-transformed cells. Pax6 has been inferred as a putative transcription factor for DUXAP10. The predicting binding site of Pax6 locates at the end of DUXAP10 promoter region (Figure 6A). In Cd-T cells, we observed significantly elevated expression level of Pax6 (Figure 6B and Supplementary Figure 10). This is the first study to show that Cd exposure induces the expression of Pax6. Further bioinformatics analysis shows that the expression level of this transcription factor is negatively corelated to the OS rate of lung cancer patients (Figure 6C). ChIP-qPCR analysis revealed that Pax6 binds to DUXAP10 promoter region (Figure 6D). Furthermore, knockdown of Pax6 decreased the expression of DUXAP10 by 50% (Figure 6E), as well as downregulating GLI1 level (Figure 6F and Supplementary Figure 11). IF staining also shows decreased nuclear localization of GLI1 in the Cd-T with knockdown of Pax6 (Figure 6G). Finally, the knockdown of Pax6 also led to reduced sphere formation by 50% (Figure 6H) in Cd-T cells.

Figure 6.

Chronic Cd exposure increases the expression of Pax6 and knockdown of Pax6 reduces DUXAP10 levels in Cd-T cells. A, Schematic map shows that the putative binding site of Pax6 locates 3 kb upstream of the DUXAP10 transcription start site, close to the 3′ end of the promoter region. B, Representative Western blot images of Pax6 level in control BEAS-2B and Cd-T cells. C, Kaplan-Meier plotter survival analysis revealed negative correlation between the expression level of Pax6 and the overall survival rate in lung cancer patients. D, ChIP qPCR analysis of relative level of DUXAP10 promoter bound by Pax6 in control BEAS-2B and Cd-T cells. Rabbit IgG was used as negative control. Percentage of input method was adopted to analyze the raw data. The repeated results are presented as means ± SD (n = 3), ****p < .0001. E, Quantitative PCR analysis of the relative level of DUXAP10 in Cd-T cells transfected with control siRNA or siRNA targeting Pax6, respectively. The RNA level in the Cd-T with Pax6 knockdown is expressed relative to the control group (means ± SD, n = 3), *p < .05. F, Representative Western blot images of levels of Pax6 and GLI1 in Cd-T cells transfected with control siRNA or Pax6 siRNA, respectively. G, Representative IF staining overlaid images of GLI1 in red fluorescence and DAPI in blue fluorescence from the Cd-T cells transfected with control siRNA or Pax6 siRNA. Scale bar: 100 µm. H, Representative images of suspension spheres formed from the Cd-T cells transfected with control siRNA or Pax6 siRNA. Scale bar: 100 µm. The bar graph represents the average numbers of the spheres formed in the repeated assays (means ± SD, n = 3), *p < .05.

DISCUSSION

Cd is a known lung carcinogen; however, the exact mechanism of Cd carcinogenesis remains to be clearly defined. CSCs or CSC-like cells play important roles in cancer initiation and progression (Ayob and Ramasamy, 2018; Bajaj et al., 2020; Economopoulou et al., 2012; Oshimori, 2020). Others and our studies showed that CSC-like cells may play critical roles in metal carcinogenesis (Dai et al., 2017; Qu et al., 2012; Tokar et al., 2010a,b; Wang and Yang, 2019; Wang et al., 2016, 2018). However, how Cd induces CSC-like population remains unknown. In the present study, immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells were exposed to Cd at a low dose for 9 months and utilized for studying the mechanism of how chronic Cd exposure induces CSC-like property. Our results suggest that the lncRNA DUXAP10 upregulation and the Hedgehog pathway activation are critically involved in chronic Cd exposure-induced CSC-like property (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

A schematic summary of the mechanism of Cd-induced CSC-like property and tumorigenesis.

It is generally accepted that Cd is relatively low genotoxic. Most studies thus focused more on the nongenotoxic effects caused by Cd exposure, especially DNA methylation. Venza et al. and Yuan et al. found that Cd contributes to silencing of tumor suppressor p16 through DNA hypermethylation in melanoma and lymphoma cells (Venza et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2013). Aberrant DNA methylation profiles have also been shown in breast cancer cells exposed to Cd (Liang et al., 2020, 2021). On the other hand, little is known about the role of noncoding RNA(s) in Cd oncogenic effect. Huang et al. and Zhou et al. reported overexpression of lncRNA MALAT1 and lncRNA-ENST00000446135 in the Cd-transformed 16HBE cells and the lungs of Cd-exposed rats, as well as in the blood of the workers exposed to Cd (Huang et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2020). However, no study has reported the role of lncRNAs in CSC-like populations induced by this heavy metal.

The findings from this study suggested a potential role of the oncogenic lncRNA DUXAP10 in the induced CSC-like property of Cd-T cells. DUXAP10 was first identified oncogenic in the study of Wei et al. in 2017, in which the results demonstrated DUXAP10 inhibited the expression of tumor suppressors: large tumor suppressor 2 (LATS2) and Ras-related associated with diabetes (Wei et al., 2017). In addition, it has been shown that DUXAP10 enhances cell proliferation and metastasis through activating the PI3K/AKT pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma (Han et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2019; Yue et al., 2019) and AKT/mTOR pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma (Li et al., 2020). Our study provides the first evidence to show that DUXAP10 contributes to CSC-like property. Furthermore, our mechanistic studies delineated that DUXAP10 contributes to Cd-induced CSC-like property likely by regulating the sonic hedgehog pathway.

It has been shown that lncRNAs could interact with various macromolecules, including DNA, RNA, and protein, to exert their biological functions (Jiang et al., 2021; Ming et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021). DUXAP10 has been shown to interact with histone demethylase lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) in nonsmall cell lung cancer cells (Wei et al., 2017). The interaction between DUXAP10 and LSD1 was also reported by Lian et al. later, which suppressed the expression of p21 and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) in colorectal cancer cells (Lian et al., 2017). Our study showed that DUXAP10 interacts with GLI1 protein and stabilizes GLI1 to regulate the Hedgehog pathway. We identified a new protein-binding partner for DUXAP10, offering a new mechanism for understanding the oncogenic role of DUXAP10.

In addition, DUXAP10 knockdown also reduced the levels of SHH and PTCH in Cd-T cells. As the driving force of the Hedgehog pathway, upregulated SHH and its receptor PTCH would further enforce the downstream signaling. The facts that DUXAP10 stabilizes GLI1 and that DUXAP10 enhances the level of SHH and PTCH altogether presented a novel oncogenic function of DUXAP10 contributing not only to the initiation of the Hedgehog pathway but also augmenting the positive feedback loop within the pathway. Our RNA pull-down studies did not detect the interaction between DUXAP10 and SHH, further studies are needed to determine the mechanism by which DUXAP10 regulates the protein levels of SHH and PTCH.

CD133 has been regarded as one of the stemness markers for various cancers, including lung cancer (Alama et al., 2015; Bertolini et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2014). In addition, CD133 is also one of the downstream targets of the Hedgehog pathway. Cd is a known lung carcinogen, yet there is no study discussing the relationship of Cd carcinogenesis and CD133 in lung cancer. In the present study, we first demonstrated that chronic Cd exposure increases the number of CD133 positive cells and knockdown of DUXAP10 in Cd-transformed cells reduces the number of CD133 positive cells. Moreover, CD133 positive cells among Cd-T cells could form significantly more spheres in the suspension culture than CD133 negative cells, suggesting that CD133 may potentially serve as a cell surface marker of the Cd-induced CSC-like population.

Although the studies of DUXAP10 all focused on its oncogenic regulations, little is known about how DUXAP10 expression level is upregulated. Pax6 is predicted as one of the putative transcription factors for DUXAP10. Here we provided the first evidence showing that Pax6 serves as a potential transcription factor for DUXAP10. Pax6 has been shown indispensable for neurodevelopmental processes, particularly for neuroectodermal epithelial tissues (Duan et al., 2013; López et al., 2020; Tao et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2010). Aberrant expression of Pax6 has been reported in various cancer types, including colon cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and lung cancer (Li et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2019; Xia et al., 2015). However, the oncogenic role of Pax6 is debatable. Downregulation of Pax6 due to its promoter hypermethylation was found significantly correlated to poorer prognosis and lower OS rate of NSCLC patients (Zhang et al., 2015). Kiselev et al. reported that Pax6 acts as a tumor suppressor, given the significant correlation between high Pax6 level and longer disease-specific survival in NSCLC patients (Kiselev et al., 2018). On the contrary, several studies provided an opposite view toward the role of Pax6 in cancer. There were studies revealing that the level of Pax6 is positively correlated to tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion (Jiang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Qian et al., 2018). In addition, Ooki et al. reported that Pax6 is responsible for the CSC characteristics (Ooki et al., 2018). Although these studies investigated the role of Pax6 in cancer cells, its role in heavy metal carcinogenesis has not been reported yet. The present study is the first one to show that the expression of Pax6 is elevated in the Cd-transformed cells and that Pax6 regulates DUXAP10 expression in Cd-transformed cells. The mechanism of how chronic Cd exposure increase Pax expression needs to be further examined.

In summary, long-term exposure to a low dose of Cd induces cell malignant transformation and CSC-like property. The upregulation of Pax6 and the oncogenic lncRNA DUXAP10 levels along with the activation of the Hedgehog signaling pathway are critically involved in chronic Cd-exposure-induced CSC-like property.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

FUNDING

National Institute of Health (R01ES026151, R01ES029496, R01ES029942).

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Achanzar W. E., Diwan B. A., Liu J., Quader S. T., Webber M. M., Waalkes M. P. (2001). Cadmium-induced malignant transformation of human prostate epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 61, 455–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerstrom M., Barregard L., Lundh T., Sallsten G. (2013). The relationship between cadmium in kidney and cadmium in urine and blood in an environmentally exposed population. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 268, 286–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alama A., Gangemi R., Ferrini S., Barisione G., Orengo A. M., Truini M., Bello M. G., Grossi F. (2015). CD133-positive cells from non-small cell lung cancer show distinct sensitivity to cisplatin and afatinib. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 63, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali I., Damdimopoulou P., Stenius U., Halldin K. (2015). Cadmium at nanomolar concentrations activates Raf-MEK-ERK1/2 MAPKs signaling via EGFR in human cancer cell line. Chem. Biol. Interact. 231, 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayob A. Z., Ramasamy T. S. (2018). Cancer stem cells as key drivers of tumour progression. J. Biomed. Sci. 25, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj J., Diaz E., Reya T. (2020). Stem cells in cancer initiation and progression. J. Cell Biol. 219, e201911053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloch S., Kazi T. G., Baig J. A., Afridi H. I., Arain M. B. (2020). Occupational exposure of lead and cadmium on adolescent and adult workers of battery recycling and welding workshops: Adverse impact on health. Sci. Total Environ. 720, 137549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini G., Roz L., Perego P., Tortoreto M., Fontanella E., Gatti L., Pratesi G., Fabbri A., Andriani F., Tinelli S., et al. (2009). Highly tumorigenic lung cancer CD133+ cells display stem-like features and are spared by cisplatin treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16281–16286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran B., Dahiya N. R., Tyagi A., Kolluru V., Saran U., Baby B. V., States J. C., Haddad A. Q., Ankem M. K., Damodaran C. (2020). Chronic exposure to cadmium induces a malignant transformation of benign prostate epithelial cells. Oncogenesis 9, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W.-C., Chang C.-Y., Lo C.-C., Hsieh C.-Y., Kuo T.-T., Tseng G.-C., Wong S.-C., Chiang S.-F., Huang K. C.-Y., Lai L.-C., et al. (2021). Identification of theranostic factors for patients developing metastasis after surgery for early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Theranostics 11, 3661–3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y., Wang D., Wang J., Yu W., Yang J. (2019). Long non-coding RNA in the pathogenesis of cancers. Cells 8, 1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementino M., Xie J., Yang P., Li Y., Lin H.-P., Fenske W. K., Tao H., Kondo K., Yang C., Wang Z. (2020). A positive feedback loop between c-Myc upregulation, glycolytic shift, and histone acetylation enhances cancer stem cell-like property and tumorigenicity of Cr(VI)-transformed cells. Toxicol. Sci. 177, 71–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Wang W., Yao S., Qiu Z., Cong L. (2021). Relationship between circulating lung-specific X protein messenger ribonucleic acid expression and micrometastasis and prognosis in patients with early-stage nonsmall cell lung cancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_1007_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J., Ji Y., Wang W., Kim D., Fai L. Y., Wang L., Luo J., Zhang Z. (2017). Loss of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase induces glycolysis and promotes apoptosis resistance of cancer-stem like cells: An important role in hexavalent chromium-induced carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 331, 164–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta P., Kulkarni P., Bhat N. S., Majid S., Shiina M., Shahryari V., Yamamura S., Tanaka Y., Gupta R. K., Dahiya R., et al. (2020). Activation of the Erk/MAPK signaling pathway is a driver for cadmium induced prostate cancer. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 401, 115102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D., Fu Y., Paxinos G., Watson C. (2013). Spatiotemporal expression patterns of Pax6 in the brain of embryonic, newborn, and adult mice. Brain Struct. Funct. 218, 353–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dontu G., Abdallah W. M., Foley J. M., Jackson K. W., Clarke M. F., Kawamura M. J., Wicha M. S. (2003). In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 17, 1253–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykes I. M., Emanueli C. (2017). Transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene regulation by long non-coding RNA. Genom. Proteom. Bioinformatics 15, 177–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economopoulou P., Kaklamani V. G., Siziopikou K. (2012). The role of cancer stem cells in breast cancer initiation and progression: Potential cancer stem cell-directed therapies. Oncologist 17, 1394–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Hu X., Zhang Y., Zhang D., Li C., Zhang L. (2014). Methods for the study of long noncoding RNA in cancer cell signaling. Methods Mol. Biol. 1165, 115–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao N., Li Y., Li J., Gao Z., Yang Z., Li Y., Liu H., Fan T. (2020). Long non-coding RNAs: The regulatory mechanisms, research strategies, and future directions in cancers. Front. Oncol. 10, 598817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovine K., Makhov P., Uzzo R. G., Kutikov A., Kaplan D. J., Fox E., Kolenko V. M. (2010). Cadmium down-regulates expression of XIAP at the post-transcriptional level in prostate cancer cells through an NF-kB-independent, proteome-mediated mechanism. Mol. Cancer 9, 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K., Li C., Zhang X., Shang L. (2019). DUXAP10 inhibition attenuates the proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by regulation of the Wnt/b-catenin and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Biosci. Rep. 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Lu Q., Chen B., Shen H., Liu Q., Zhou Z., Lei Y. (2017). LncRNA-MALAT as a novel biomarker of cadmium toxicity regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis. Toxicol. Res. 6, 361–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff J., Lunn R., Waalkes M., Tomatis L., Infante P. (2007). Cadmium-induced cancers in animals and in humans. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 13, 202–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzicker E. G., Estay I. S., Zhen H., Lokteva L. A., Jackson P. K., Oro A. E. (2006). Dual degradation signals control Gli protein stability and tumor formation. Genes Dev. 20, 276–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona J. P., Gaffield W., Kapur R. P., Roelink H. (1998). The teratogenic veratrum alkaloid cyclopamine inhibits sonic hedgehog signal transduction. Development 125, 3553–3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q., Xing W., Cheng J., Yu Y. (2020). Knockdown of lncRNA XIST suppresses cell tumorigenicity in human non-small cell lung cancer by regulating miR-142-5p/Pax6 axis. OncoTragets Ther. 13, 4919–4929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N., Zhang X., Gu X., Li X., Shang L. (2021). Progress in understanding the role of lncRNA in programmed cell death. Cell Death Discov. 7, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselev Y., Andersen S., Johannessen C., Fjukstad B., Standahl Olsen K., Stenvold H., Al-Saad S., Donnem T., Richardsen E., Bremnes R. M., et al. (2018). Transcription factor Pax6 as a novel prognostic factor and putative tumor suppressor in non small cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 8, 5059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Jiang L., Liu Z., Li Y., Xu Y., Liu H. (2020). Oncogenic pseudogene DUXAP10 knockdown suppresses proliferation and invasion and induces apoptosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells by inhibition of Akt/mTOR pathway. Clin. Exp. Pharm. Physiol. 47, 1473–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Meng H., Bai Y., Wang K. (2016). Regulation of lncRNA and its role in cancer metastasis. Oncol. Res. 23, 205–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li Y., Liu Y., Xie P., Li F., Li G. (2014). PAX6, a novel target of microRNA-7, promotes cellular proliferation and invasion in human colorectal cancer cells. Dig. Dis. Sci. 59, 598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian Y., Xu Y., Xiao C., Xia R., Gong H., Yang P., Chen T., Wu D., Cai Z., Zhang J., et al. (2017). The pseudogene derived from long non-coding RNA DUXAP10 promotes colorectal cancer cell growth through epigenetically silencing of p21 and PTEN. Sci. Rep. 7, 7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Pi H., Liao L., Tan M., Deng P., Yue Y., Xi Y., Tian L., Xie J., Chen M., et al. (2021). Cadmium promotes breast cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion by inhibiting ACSS2/ATG5-mediated autophagy. Environ. Pollut. 273, 116504.DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z., Zhu R., Li Y., Jiang H., Li R., Tang L., Wang Q., Ren Z. (2020). Differential epigenetic and transcriptional profile in MCF-7 breast cancer cells exposed to cadmium. Chemosphere 261, 128148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Han L., Yu H., Gao N., Xin H. (2020). LINC01619 promotes non-small cell lung cancer development via regulating Pax6 by suppressing microRNA-129-5p. Am. J. Transl. Res. 12, 2538–2553. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López J. M., Morona R., Moreno N., Lozano D., Jiménez S., González A. (2020). Pax6 expression highlights regional organization in the adult brain of lungfishes, the closest living relatives of land vertebrates. J. Comp. Neurol. 528, 139–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer T. R., Mattick J. S. (2013). Structure and function of long noncoding RNAs in epigenetic regulation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming H., Li B., Zhou L., Goel A., Huang G. (2021). Long non-coding RNAs and cancer metastasis: Molecular basis and therapeutic implications. BBA Rev. Cancer 1875, 188519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra R. R., Smith G. T., Waalkes M. P. (1998). Evaluation of the direct genotoxic potential of cadmium in four different rodent cell lines. Toxicology 126, 103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata T., Oyama T., Yoshimatsu T., Higa H., Kawano D., Sekimura A., Yamashita N., So T., Gotoh A. (2017). The clinical significance of cancer stem cell markers ALDH1A1 and CD133 in lung adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 37, 2541–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooki A., Dinalankara W., Marchionni L., Tsay J.-C., Goparaju C., Maleki Z., Rom W. N., Pass H. I., Hoque M. O. (2018). Epigenetically regulated Pax6 drives cancer cells toward a stem-like state via GLI-SOX2 signaling axis in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene 37, 5967–5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshimori N. (2020). Cancer stem cells and their niche in the progression of squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 111, 3985–3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perona R., Lopez-Ayllon B. D., de Castro Carpeno J., Belda-Iniesta C. (2011). A role for cancer stem cells in drug resistance and metastasis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 13, 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z., Zhang Q., Hu Y., Zhang T., Li J., Liu Z., Zheng H., Gao Y., Jia W., Hu A., et al. (2018). Investigating the mechanism by which SMAD3 induces Pax6 transcription to promote the development of non-small cell lung cancer. Respir. Res. 19, 262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu W., Tokar E. J., Kim A. J., Bell M. W., Waalkes M. P. (2012). Chronic cadmium exposure in vitro causes acquisition of multiple tumor cell characteristics in human pancreatic epithelial cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 1265–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudin C. M., Brambilla E., Faivre-Finn C., Sage J. (2021). Small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 7, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Fuchs H. E., Jemal A. (2021). Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Jemal A. (2020). Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 70, 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Wei Z., Shaikh Z. (2015). Requirement of Era and basal activities of EGFR and Src kinase in Cd-induced activation of MAPK/ERK pathway in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 287, 26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Wang L., Chen T., Yao B., Wang Y., Li Q., Yang W., Liu Z. (2019). MicroRNA-1914, which is regulated by lncRNA DUXAP10, inhibits cell proliferation by targeting the GPR39-mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in HCC. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 23, 8292–8304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y., Cao J., Li M., Hoffmann B., Xu K., Chen J., Lu X., Guo F., Li X., Phillips M. J., et al. (2020). PAX6D instructs neural retinal specification from human embryonic stem cell-derived neuroectoderm. EMBO Rep. 21, e50000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokar E. J., Diwan B. A., Waalkes M. P. (2010a). Arsenic exposure transforms human epithelial stem/progenitor cells into a cancer stem-like phenotype. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 108–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokar E. J., Qu W., Liu J., Liu W., Webber M. M., Phang J. M., Waalkes M. P. (2010b). Arsenic-specific stem cell selection during malignant transformation. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 102, 638–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venza M., Visalli M., Biondo C., Oteri R., Agliano F., Morabito S., Teti D., Venza I. (2015). Epigenetic marks responsible for cadmium-induced melanoma cell overgrowth. Toxicol. In Vitro 29, 242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waalkes M. P. (2000). Cadmium carcinogenesis in review. J. Inorg. Chem. 79, 241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Fan J., Hitron J. A., Son Y. O., Wise J. T., Roy R. V., Kim D., Dai J., Pratheeshkumar P., Zhang Z., et al. (2016). Cancer stem-like cells accumulated in nickel-induced malignant transformation. Toxicol. Sci. 151, 376–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. S., Wang Z., Yang C. (2021). Dysregulations of long non-coding RNAs - The emerging “lnc” in environmental carcinogenesis. Semin. Cancer Biol. S1044-579X, 00079–00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Li X. D., Fu Z., Zhou Y., Huang X., Jiang X. (2019a). Long non-coding RNA LINC00473/miR-195-5p promotes glioma progression via YAP1-TEAD1-Hippo signaling. Int. J. Oncol. 56, 508–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Humphries B., Xiao H., Jiang Y., Yang C. (2014). MicroRNA-200b suppresses arsenic-transformed cell migration by targeting protein kinase Ca and Wnt5b-protein kinase Ca positive feedback loop and inhibiting Rac1 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 18373–18386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Lin H.-P., Li Y., Tao H., Yang P., Xie J., Maddy D., Kondo K., Yang C. (2019b). Chronic hexavalent chromium exposure induces cancer stem cell-like property and tumorigenesis by increasing c-Myc expression. Toxicol. Sci. 172, 252–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Wu J., Humphries B., Kondo K., Jiang Y., Shi X., Yang C. (2018). Upregulation of histone-lysine methyltransferases plays a causal role in hexavalent chromium-induced cancer stem cell like property and cell transformation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 342, 22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Yang C. (2019). Metal carcinogen exposure induces cancer stem cell-like property through epigenetic reprograming: A novel mechanism of metal carcinogenesis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 57, 95–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Zhao Y., Smith E., Goodall G. J., Drew P. A., Brabletz T., Yang C. (2011). Reversal and prevention of arsenic-induced human bronchial epithelial cell malignant transformation by microRNA-200b. Toxicol. Sci. 121, 110–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C.-C., Nie F.-Q., Jiang L.-L., Chen Q.-N., Chen Z.-Y., Chen X., Pan X., Liu Z.-L., Lu B.-B., Wang Z.-X. (2017). The pseudogene DUXAP10 promotes and aggressive phenotype through binding with LSD1 and repressing LATS2 and RRAD in non small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 8, 5233–5246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z., Shan Z., Shaikh Z. (2018). Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast epithelial cells treated with cadmium and the role of Snail. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 344, 46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D. M., Zhang T., Liu Y. B., Deng S. H., Han R., Liu T., Li J., Xu Y. (2019). The PAX6-ZEB2 axis promotes metastasis and cisplatin resistance in non-small cell lung cancer through PI3K/AKT signaling. Cell Death Dis. 10, 349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Qi X. W., Yan G. N., Zhang Q. B., Xu C., Bian X. W. (2014). Is CD133 expression a prognostic biomarker of non-small-cell lung cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 9, e100168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., Yin W., Zhang X., Yu X., Wang C., Xu S., Feng W., Yang H. (2015). PAX6 overexpression is associated with the poor prognosis of invasive ductal breast cancer. Oncol. Lett. 10, 1501–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C., Liu Y., Xie C., Tu W., Xia Y., Costa M., Zhou X. (2015). Cadmium induces histone H3 lysine methylation by inhibiting demethylase activity. Toxicol. Sci. 145, 80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Jiang E., Shao Z., Shang Z. (2021). Long noncoding RNAs in the metastasis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 10, 616717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Yu X., Wei C., Nie F., Huang M., Sun M. (2018). Over-expression of oncogenic pseudogene DUXAP10 promotes cell proliferation and invasion by regulating LATS1 and b-catenin in gastric cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 37, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Liu Y., Lemmon M. A., Kazanietz M. G. (2006). Essential role for Rac in Heregulin b1 mitogenic signaling: A mechanism that involves epidermal growth factor receptor and is independent of ErbB4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 831–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Wu J., Zhang R., Zhang P., Eckard J., Yusuf R., Huang X., Rossman T. G., Frenkel K. (2005). Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) prevents transformation of human cells by arsenic (As) and suppresses growth of As-transformed cells. Toxicology 213, 81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan D., Ye S., Pan Y., Bao Y., Chen H., Shao C. (2013). Long-term cadmium exposure leads to the enhancement of lymphocyte proliferation via down-regulating p16 by DNA hypermethylation. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 757, 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C., Liang C., Ge H., Yan L., Xu Y., Li G., Li P., Wei Z., Wu J. (2019). Pseudogene DUXAP10 acts as a diagnostic and prognostic marker and promotes cell proliferation by activating PI3K/AKT pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Targets Ther. 12, 4555–4566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Wang G., Xu L., Yao Z., Song L. (2019a). Long non-coding RNA LIN00473 promotes glioma cells proliferation and invasion by impairing miR-637/CDK6 axis. Artificial Cells. Nanomed. Biotechnol. 47, 3896–3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Huang C. T., Chen J., Pankratz M. T., Xi J., Li J., Yang Y., Lavaute T. M., Li X. J., Ayala M., et al. (2010). Pax6 is a human neuroectoderm cell fate determinant. Cell Stem Cell 7, 90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Wang W., Zhu W., Dong J., Cheng Y., Yin Z., Shen F. (2019b). Mechanisms and Functions of Long Non-Coding RNAs at Multiple Regulatory Levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Yang X., Wang J., Liang T., Gu Y., Yang D. (2015). Down-regulation of Pax6 by promoter methylation is associated with poor prognosis in non small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 8, 11452–11457. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Huang Z., Chen B., Lu Q., Cao L., Chen W. (2020). LncRNA-ENST00000446135 is a novel biomarker of cadmium toxicity in 16HBE cells, rats, and Cd-exposed workers and regulates DNA damage and repair. Toxicol. Res. 6, 823–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.