Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study is to examine the extent to which numeric rating scale (NRS) scores collected during usual care are associated with more robust and validated measures of pain, disability, mental health, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

Design

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from a prospective cohort study.

Subjects

We included 186 patients with musculoskeletal pain who were prescribed long-term opioid therapy.

Setting

VA Portland Health Care System outpatient clinic.

Methods

All patients had been screened with the 0–10 NRS during routine outpatient visits. They also completed research visits that assessed pain, mental health and HRQOL every 6 months for 2 years. Accounting for nonindependence of repeated measures data, we examined associations of NRS data obtained from the medical record with scores on standardized measures of pain and its related outcomes.

Results

NRS scores obtained in clinical practice were moderately associated with pain intensity scores (B’s = 0.53–0.59) and modestly associated with pain disability scores (B’s = 0.33–0.36) obtained by researchers. Associations between pain NRS scores and validated measures of depression, anxiety, and health related HRQOL were low (B’s = 0.09–0.26, with the preponderance of B’s < .20).

Conclusions

Standardized assessments of pain during usual care are moderately associated with research-administered measures of pain intensity and would be improved from the inclusion of more robust measures of pain-related function, mental health, and HRQOL.

Keywords: Pain Intensity, Numeric Pain Rating Scale, Electronic-Health Record Data, Pain-Related Outcomes

Introduction

In the mid-1990s, measuring pain as the “fifth vital sign” was introduced as a strategy to improve quality of pain management [1]. Since that time, there has been widespread utilization of pain screening tools as a part of usual care across many health care settings [2]. The numeric rating scale (NRS) is a pain screening tool, commonly used to assess pain severity at that moment in time using a 0–10 scale, with zero meaning “no pain” and 10 meaning “the worst pain imaginable” [3]. In many clinical settings, pain is assessed regularly in outpatient care using the NRS; these scores are recorded in the patient’s electronic health record (EHR), allowing researchers and clinicians to track pain intensity over time.

There are, however, limitations to the clinical administration of the NRS. First, inconsistencies with clinical administration can lead to over- or underestimation of pain [4]. In addition, there are concerns about the accuracy of NRS scores collected in clinical settings for identifying patients with clinically important pain, defined as pain that interferes with functioning or motivates a physician visit [5]. There are also limitations of the NRS collected during clinical visits for use in research, including non-normal distribution, inconsistent time intervals between measurements, and variation of NRS scores within subjects over brief time periods [6, 7].

Despite these limitations, longitudinal pain intensity EHR data are used by researchers to examine the effectiveness of different interventions on pain intensity in pragmatic trials and observational research [8, 9]. As such, demonstrating the utility of these data for understanding health outcomes is imperative. Some prior research has examined the extent to which NRS scores administered for clinical purposes compare to NRS scores administered for research purposes. For example, among a sample of 528 outpatient clinical encounters for chronic pain, moderate correlations were found between research-administered NRS score and clinically administered NRS score (r = 0.63), and the Brief Pain Inventory severity subscale (r = 0.61) [10]. Although these findings provide some support for the use of administrative NRS data, unidimensional pain scores solely focused on pain intensity may not give the full picture of the pain experience [11]. It has been recommended that additional facets of the pain experience besides pain intensity be assessed, including pain-related function, depression, and quality of life [12]. The relationships between the NRS scores administered as part of usual care and these other pain related factors (e.g., depression, quality of life) as well as the measurement tools used to assess these other pain related factors have not been elucidated. The present study expands upon the current literature by investigating associations of NRS scores with a broader range of pain-related outcomes than have previously been examined, such as pain disability, health-related quality of life (HRQOL), anxiety, and depression. This information provides additional context for the strengths and weaknesses of the NRS score for clinical pain assessment and re-use of NRS EHR data for research.

The purpose of this study is to examine the extent to which NRS scores collected during usual care are associated with more robust and validated measures of pain, mental health, and HRQOL. We sought to understand how closely NRS scores obtained during usual care both at a single point in time and over several weeks to months associate with (1) a research-administered measure of pain intensity and (2) measures of pain disability, mental health, and HRQOL. We hypothesized that clinically collected NRS scores would have higher association with pain intensity and lower association with pain disability, mental health, and HRQOL. Findings may inform the utility of administrative NRS scores for examining the quality of pain-related interventions on important clinical outcomes.

Methods

Participants

All participants were receiving care at the VA Portland Health Care System, a Department of Veterans Affairs hospital and clinic system in Portland, OR. Participants were recruited from December 2013 to October 2015. Participants were enrolled in a larger study examining the correlates and outcomes of prescription opioid dose escalation for the treatment of chronic pain [13]. Patients included in the larger study (as well as this secondary analysis) were eligible to enroll if they were prescribed a stable dose of opioid therapy of at least 3 months duration for musculoskeletal pain and could read and write in English. Patients were excluded if they received prescription opioids for cancer treatment or palliative care, had pending litigation or disability claims for pain, were less than 18 years old, had enrolled in an opioid substitution program in the past year, lacked reliable telephone access, had a current prescription opioid dose > 120 mg morphine equivalents, or received an opioid prescription consisting only of tramadol or buprenorphine.

Procedures

Research visits were conducted at baseline and 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-baseline either face-to-face or via telephone. NRS scores administered during outpatient care either prior to or after each of the five research visits were extracted from the EHR. For our primary analysis, we included NRS scores that were administered 2 weeks before and after research assessments (4-week interval). For each of these intervals, in instances in which multiple outpatient NRS scores were available, NRS scores were averaged using methods consistent with prior research [7, 14]. In cases when only one recorded NRS score was available during the time interval, the single score was used as the NRS pain score for that participant.

In a series of secondary analyses, we examined relationships between research visit data and NRS scores obtained from longer time periods in proximity to research assessments. For example, in addition to examining only NRS scores available 2 weeks prior to and after research assessments (4-week interval), we examined scores available 4 weeks prior to and after assessments (8-week interval), 8 weeks prior to and after assessments (16-week interval), and 12 weeks prior to and after assessments (24-week interval). Again, if multiple NRS scores were present, the average of these scores was used.

All study procedures were reviewed, approved, and monitored by the Institutional Review Board at the VA Portland Health Care System. All participants provided informed consent to complete study procedures and permit data extraction from the EHR.

Measures

EHR Data

The NRS is commonly used for measuring pain intensity and is well validated. It is scored from 0–10 (0 meaning no pain and 10 meaning the worst pain imaginable) [15, 16]. NRS scores are recorded as structured vital sign data in the VA EHR; they were extracted from the EHR through the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which combines EHR data for all VA patients into a relational database.

Survey Data

The Chronic Pain Grade (CPG) is a 7-item self-report measure that includes scales for pain intensity and pain disability [17] .The CPG assesses current pain and pain over a 3-month period and is commonly used and well validated.

Depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) [18, 19]. This is an 8-item self-report measure, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms and scores of 10 or greater indicating moderate depression [18, 19]. Anxiety in the past two weeks was assessed with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale (GAD-7) [20]. This is a brief self-report measure designed to assess the severity of anxiety symptoms. It has been validated as a robust predictor of the different anxiety disorders and scores of 10 or greater indicate moderate anxiety [20]. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in the past 4 weeks was measured with the Short-Form Health Survey, Version 2 (SF-12v2) [21]. This is a 12-item well-validated self-report measure of physical and mental health functioning. Higher scores are associated with better functioning.

Demographic data were collected as part of self-administered surveys. Data collected included age, gender, race, marital status, employment status, socioeconomic status, and disability status.

Statistical Analyses

Data were assessed for completeness and accuracy. Patient data were available for up to 5 assessment periods. The numbers of unique patients completing assessments at each time point for the self-reported outcome measures were as follows: Baseline: n = 184, 6 months: n = 171, 12 months: n = 167, 18 months: n = 162, 24 months: n = 154. All available data were utilized in analyses. Generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with model-based variance estimation and unstructured correlation matrices were used to examine bivariate associations of NRS data obtained from the medical record with patient-reported outcomes—pain intensity and disability as measured by the Chronic Pain Grade, depression as measured by the PHQ-8, anxiety as measured by the GAD-7, and mental and physical functioning as measured by the SF-12v2. GEEs controlled for longitudinal associations of patient-reported outcomes from individual patients who completed 2 or more assessments. In the primary model, we examined the association between patient reported outcomes and NRS scores available 2 weeks before and after the research assessments (4-week interval). Subsequent models characterized associations between patient-reported outcomes and NRS scores from the EHR averaged over 8-, 16-, and 24-week intervals surrounding the study visit. All inferential analyses used two-tailed tests and alpha = 0.05. Associations are reported using standardized beta coefficients that range from −1 to 1.

Results

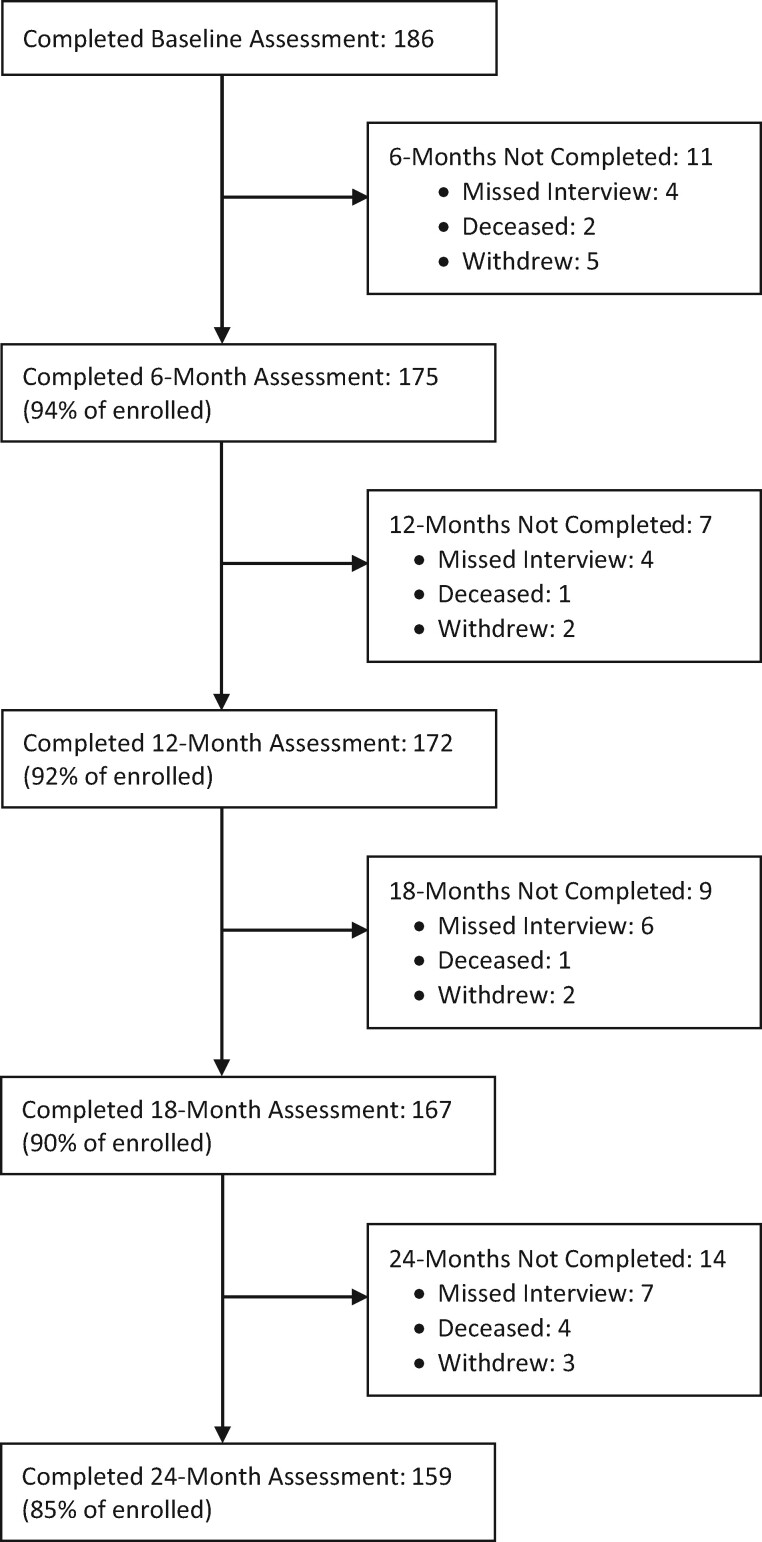

Figure 1 displays the study retention and reasons for missing data over all five time points for the sample. The overall sample comprised 186 patients with a mean age of 59.9 years (SD = 11.9 years). The majority of the sample identified as male (89.8%), white, non-Hispanic (76.9%) and had attended some college (60.2%). The most common musculoskeletal pain conditions included back pain (63%), neck or joint pain (53%), and arthritis (50%). The average daily opioid dose at baseline was 33.8 mg morphine equivalents (SD = 24.7). An overview of the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics can be found in Table 1. Table 1 also contains an overview of the average score for each of the self-reported outcomes aggregated across all five time points. Table 2 includes the summary scores of the clinical measures obtained at each time point.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram.

Table 1.

Sample sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

| Demographic Variables | M (SD) | % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 59.9 (11.9) | |

| Male | 89.8 (167) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 76.9 (143) | |

| Native American, Non-Hispanic | 11.8 (22) | |

| Hispanic, any race | 6.9 (13) | |

| African American, Non-Hispanic | 4.3 (8) | |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 16.1 (30) | |

| Some college | 60.2 (112) | |

| College or graduate school | 23.7 (44) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living with partner | 52.7 (98) | |

| Separated/divorced | 34.9 (65) | |

| Widowed | 7.5 (14) | |

| Never married | 4.8 (9) | |

| Employment | ||

| Disabled | 37.6 (70) | |

| Retired | 31.2 (58) | |

| Working/homemaker | 30.1 (56) | |

| Other | 1.1 (2) | |

| Clinical variables | ||

| Opioid dose in MME | 33.8 (24.7) | |

| Arthritis | 50.0 (93) | |

| Back pain | 61.8 (115) | |

| Neck or joint pain | 53.2 (99) | |

| Nicotine use | 37.6 (70) | |

| Self-reported outcome measures | ||

| Pain intensity (CPG) | 64.53 (15.37) | |

| Pain disability (CPG) | 50.06 (27.65) | |

| Depression severity (PHQ-8) | 9.13 (6.06) | |

| Proportion with moderate depression | 48.5 (90) | |

| Anxiety severity (GAD-7) | 6.82 (6.17) | |

| Proportion with moderate anxiety | 33.9 (63) | |

| Physical functioning (SF-12) | 37.71 (33.21) | |

| Mental functioning (SF-12) | 58.82 (25.43) | |

| NRS scores | ||

| 4-week interval | 4.91 (2.75) | |

| 8-week interval | 4.86 (2.61) | |

| 16-week interval | 4.85 (2.59) | |

| 24-week interval | 4.64 (2.47) |

N = 186. MME = morphine milligram equivalent; CPG = Chronic Pain Grade; PHQ-8 = Patient Health Questionnaire- 8 item; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder- 7 item; SF-12 = Short Form-12 item.

Table 2.

Scores of self-reported pain, mental health and quality of life outcomes

| Self-Report Variable | Baseline M (SD) N = 184 | 6 Months M (SD) N = 171 | 12 Months M (SD) N = 167 | 18 Months M (SD) N = 162 | 24 Months M (SD) N = 154 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity (CPG) | 65.63 (13.38) | 64.58 (15.41) | 64.19 (16.47) | 64.30 (16.24) | 63.77 (15.55) |

| Pain disability (CPG) | 53.19 (24.54) | 48.42 (28.57) | 48.98 (28.46) | 49.69 (28.90) | 48.62 (27.96) |

| Depression severity (PHQ-8) | 9.84 (9.03) | 9.23 (5.90) | 9.08 (6.00) | 8.77 (6.16) | 8.57 (6.23) |

| Anxiety severity (GAD-7) | 7.23 (6.28) | 7.29 (6.33) | 6.71 (6.26) | 6.55 (6.11) | 6.23 (5.79) |

| Physical functioning (SF-12) | 35.19 (25.00) | 36.37 (32.80) | 39.07 (31.23) | 39.20 (35.01) | 38.80 (33.95) |

| Mental functioning (SF-12) | 57.13 (25.79) | 58.70 (25.69) | 58.83 (25.68) | 59.95 (25.24) | 59.74 (24.89) |

As shown in Table 3, the 4-week interval NRS pain intensity score obtained in clinical practice within 2 weeks prior to or after the research assessment was moderately associated with pain intensity as measured by the CPG (B = 0.59). Associations were similar in magnitude when EHR-derived NRS pain scores were averaged over 4-, 8-, 16-, and 24-week intervals. Similar patterns of stability over time were observed for associations between EHR-derived NRS pain scores and all of the other patient-reported outcomes, though the magnitude of these associations was less than that observed between EHR-derived NRS pain scores and patient-reported pain intensity. Specifically, the 4-week interval NRS association with each of the patient-reported outcomes were: pain disability, B = 0.33; depression, B = 0.26; anxiety, B = 0.26; Physical functioning (SF-12v2), B = −0.15; and mental functioning (SF-12v2), B = −0.13. The weakest associations were observed between EHR-derived NRS pain scores and patient-reported physical and mental health related functioning, with the 16-week NRS scores failing to reach statistical significance with SF-12 mental functioning.

Table 3.

Associations between NRS scores and clinical variables

| Clinical Variable | 4-week Avg NRS | 8-week Avg NRS | 16-week Avg NRS | 24-week Avg NRS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity | 0.59*** | 0.54*** | 0.56*** | 0.53*** |

| (n = 232) | (n = 375) | (n = 531) | (n = 628) | |

| Pain disability | 0.33*** | 0.35*** | 0.34*** | 0.36*** |

| (n = 231) | (n = 373) | (n = 528) | (n = 622) | |

| Depression severity | 0.26*** | 0.20*** | 0.21*** | 0.26*** |

| (n = 230) | (n = 372) | (n = 528) | (n = 625) | |

| Anxiety severity | 0.26*** | 0.19*** | 0.19*** | 0.23*** |

| (n = 232) | (n = 375) | (n = 529) | (n = 625) | |

| Physical functioning | −0.15* | −0.16* | −0.16*** | −0.16*** |

| (n = 232) | (n = 374) | (n = 530) | (n = 626) | |

| Mental functioning | −0.13* | −0.14* | −0.09+ | −0.12* |

| (n = 232) | (n = 375) | (n = 531) | (n = 626) |

n in parentheses denotes number of observations for the specified correlation. Each participant could contribute up to five observations spread over a 24-month period to the generalized estimating equation models. Unique observations at each time point for the self-reported outcome measures were as follows: Baseline: n = 184; 6 months: n = 171; 12 months: n = 167; 18 months: n = 162; 24 months: n = 154.

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001.

Not significant at P < .05.

Discussion

We found that NRS scores obtained during routine clinical care and extracted from the EHR are moderately associated with a standardized measure of pain intensity. In addition, EHR NRS scores have modest associations with pain disability scores, and low associations with validated measures of depression, anxiety, and health related quality of life administered during a clinical research study. We examined this association with NRS scores documented within 4-, 8-,16-, and 24-week intervals around each research-administered assessment over the course of a 2-year prospective cohort study. The association of pain intensity with NRS had limited variation over the four-time intervals, providing evidence of consistency in patients’ experiences of pain intensity over time, similar to what other researchers have observed [9].

We found that associations between pain NRS scores and other validated measures of depression, anxiety, and quality of life were low. A takeaway from this finding is that health care systems might better capture constructs germane to patients’ pain experiences by implementing standardized multidimensional brief assessments in routine clinical care and documenting their results in the EHR. Brief measures could provide an opportunity to capture a broader range of the pain experience while minimizing additional burden during a clinical encounter. Examples of such measures include the Patient Health Questionaire-2 item scale (PHQ-2), which is a validated 2-item measure of depression [22] or the Pain, Enjoyment, General Activity (PEG) scale which is a three item questionnaire assessing pain intensity, interference with enjoyment of life, and interference with general activity [23]. Brief measures such as these, as well as measures of quality of life, can be increasingly administered prior to clinical appointments (using electronic or web-based devices) [24] and subsequently made available to the clinicians and populated into the EHR [25]. Another approach for clinical use of the NRS is a two-step screening process, whereby a score greater than or equal to 5 on the NRS would flag a patient for more thorough assessment of the pain experience, including function, mood, and quality of life, while lower scores would not result in additional assessment [26].

Our finding of a moderate association between clinically administered NRS score and research-administered pain intensity scores is similar in magnitude to a prior study that compared clinically administered NRS scores to (a) research-administered NRS scores (r = 0.63), (b) research-administered Brief Pain Inventory, severity ratings in the last 24 hours (r = 0.61), and (c) Brief Pain Inventory, severity ratings in the last week (r = 0.59) [10]. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that using EHR-derived NRS scores from administrative data can provide important information in the context of comparative effectiveness research. Specifically, well-controlled observational studies using administrative data could provide preliminary evidence of intervention effectiveness on pain intensity, particularly in contexts where it would be too expensive or ethically questionable to conduct large RCTs. However, findings from this study support the augmentation of NRS scores with additional measures of disability, mental health symptoms, and quality of life, which are recommend outcomes in pain trials [9, 12].

There are, however, limitations to using NRS scores collected for clinical purposes in the context of comparative effectiveness studies. These include variation in clinical administration, which may reduce NRS accuracy [4–7], and incomplete or missing data (not at random) for people who are not receiving care. Some of these issues can be mitigated via the use of statistical techniques and rigorous selection of cases from EHR data. More broadly, the use of administrative data has been associated with issues of incompleteness and inconsistencies [27]. Thus, it is important for research projects using EHR data to consider these challenges, as well as methods to overcome them, when possible. In addition, for those using the NRS solely for research purposes, it is important to acknowledge that an EHR NRS may not extrapolate to other pain-related outcomes [28]. Learning health care system infrastructure such as the Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry (CHOIR) may provide a platform to bridge EHR NRS scores with more robust pain outcomes that are regularly documented in the EHR and can be leveraged for research purposes [29]. For example, one study embedded patient reported outcomes, such as pain and quality of life, which allowed researchers to compare retrospective outcomes across several health care system mental health clinics [30].

It is important to note some limitations to this study. The sample comprised patients seeking outpatient care in a single VA medical center who were prescribed long-term opioid therapy and enrolled in a clinical research study, which may not generalize to other pain populations. In addition, the sample was predominantly male and White, Non-Hispanic, potentially reducing generalizability to more diverse populations. The EHR and research administered tools were collected at asynchronous time points, and the NRS and research-administered measures also have differing recall periods. The strength of associations between these variables may be attenuated if patients experienced variable pain, mood, and functioning over recall windows that span several weeks. Finally, we included some validated measures of pain related outcomes, but findings may differ with other measures.

Conclusion

There is a moderate association between EHR-derived NRS scores with pain intensity, modest association with pain disability, and low association with other pain-related outcomes such as mood and quality of life. Our findings may support conducting retrospective studies that examine changes in pain intensity, though not other pain-related outcomes. This study advances our understanding of the associations between clinically collected NRS scores and a broader range of pain-related variables than have previously been examined, including pain disability, mental health, and mental and physical functioning. Clinicians and researchers using EHR data for comparative effectiveness purposes would benefit from the inclusion of more robust measures of pain-related function, mood, and quality of life during routine patient care.

Disclosures and Funding Sources: This work was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant number 034083, PI: Morasco). The work was also supported by resources from the VA Health Services Research and Development-funded Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care at the VA Portland Health Care System (CIN 13-404, PI: Dobscha) and an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant (132817 MSRG-18-216-01-CPHPS, PI: Nugent). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or NIDA.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1. Max M, Donovan M, Maiskowski CA, et al. Quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. American Pain Society Quality of Care Committee. JAMA 1995;274(23):1874–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baker DW. The Joint Commission’s Pain Standards: Origins and Evolution. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2017.

- 3. Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth 2008;101(1):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shugarman LR, Goebel JR, Lanto A, et al. Nursing staff, patient, and environmental factors associated with accurate pain assessment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40(5):723–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krebs EE, Carey TS, Weinberger M.. Accuracy of the pain numeric rating scale as a screening test in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22(10):1453–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goulet JL, Brandt C, Crystal S, et al. Agreement between electronic medical record-based and self-administered pain numeric rating scale: Clinical and research implications. Med Care 2013;51(3):245–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prokosch HU, Ganslandt T.. Perspectives for medical informatics. Methods Inf Med 2009;48(1):38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dobscha SK, Lovejoy TI, Morasco BJ, et al. Predictors of improvements in pain intensity in a National Cohort of Older Veterans with Chronic Pain. J Pain 2016;17(7):824–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McPherson S, Lederhos Smith C, Dobscha SK, et al. Changes in pain intensity after discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain. Pain 2018;159(10):2097–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lorenz KA, Sherbourne CD, Shugarman LR, et al. How reliable is pain as the fifth vital sign? J Am Board Fam Med 2009;22(3):291–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Levy N, Sturgess J, Mills P.. “Pain as the fifth vital sign” and dependence on the “numerical pain scale” is being abandoned in the US: Why? Br J Anaesth 2018;120(3):435–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9(2):105–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morasco BJ, Smith N, Dobscha SK, Deyo RA, Hyde S, Yarborough BJH.. Outcomes of prescription opioid dose escalation for chronic pain: Results from a prospective cohort study. Pain 2020;161(6):1332–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dobscha SK, Morasco BJ, Kovas AE, Peters DM, Hart K, McFarland BH.. Short-term variability in outpatient pain intensity scores in a national sample of older veterans with chronic pain. Pain Med 2015;16(5):855–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S.. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: A comparison of six methods. Pain 1986;27(1):117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jensen MP, Karoly P, O'Riordan EF, Bland F Jr., Burns RS.. The subjective experience of acute pain: An assessment of the utility of 10 indices. Clin J Pain 1989;5(2):153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF.. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain 1992;50(2):133–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL.. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Ann 2002;32(9):509–15. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB.. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9):606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB.. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. Jama 1999;282(18):1737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ware J Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD.. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34(3):220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB.. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41(11):1284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24(6):733–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Falchook AD, Tracton G, Stravers L, et al. Use of mobile device technology to continuously collect patient-reported symptoms during radiation therapy for head and neck cancer: A prospective feasibility study. Adv Radiat Oncol 2016;1(2):115–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoang NS, Hwang W, Katz DA, Mackey SC, Hofmann LV.. Electronic patient-reported outcomes: Semi-automated data collection in the interventional radiology clinic. J Am Coll Radiol 2019;16(4 Pt A):472–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kroenke K, Stump TE, Kean J, et al. PROMIS 4-Item measures and numeric rating scales effeciently assess SPADE symptoms compared to legacy measures. J Clin Epidemiol 2019;115:116–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Botsis T, Hartvigsen G, Chen F, Weng C.. Secondary use of EHR: Data quality issues and informatics opportunities. Summit Transl Bioinform 2010:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dworkin RH, Kerns RD, McDermott MP, Turk DC, Veasley C.. The ACTTION guide to clinical trials of pain treatments: Standing on the shoulders of giants. Pain Rep 2019;4(3):e757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanford University. CHOIR. Available at: https://choir.stanford.edu/. 2020. (accessed May 11, 2020).

- 30. Gillman A, Zhang D, Jarquin S, Karp JF, Jeong JH, Wasan AD.. Comparative effectiveness of embedded mental health services in pain management clinics vs standard care. Pain Med 2019;21:978–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]