Abstract

Tracking longitudinal tau tangles accumulation across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum is crucial to better understand the natural history of tau pathology and for clinical trials. Although the available first-generation tau PET tracers detect tau accumulation in symptomatic individuals, their nanomolar affinity offers limited sensitivity to detect early tau accumulation in asymptomatic subjects.

Here, we hypothesized the novel subnanomolar affinity tau tangles tracer 18F-MK-6240 can detect longitudinal tau accumulation in asymptomatic and symptomatic subjects. We studied 125 living individuals (65 cognitively unimpaired elderly amyloid-β-negative, 22 cognitively unimpaired elderly amyloid-β-positive, 21 mild cognitive impairment amyloid-β-positive and 17 Alzheimer’s disease dementia amyloid-β-positive individuals) with baseline amyloid-β 18F-AZD4694 PET and baseline and follow-up tau 18F-MK-6240 PET. The 18F-MK-6240 standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) was calculated at 90–110 min after tracer injection and the cerebellar crus I was used as the reference region. In addition, we assessed the in vivo18F-MK-6240 SUVR and post-mortem phosphorylated tau pathology in two participants with Alzheimer’s disease dementia who died after the PET scans.

We found that the cognitively unimpaired amyloid-β-negative individuals had significant longitudinal tau accumulation confined to the PET Braak-like stage I (3.9%) and II (2.8%) areas. The cognitively unimpaired amyloid-β-positive individuals showed greater tau accumulation in Braak-like stage I (8.9%) compared with later Braak stages. The patients with mild cognitive impairment and those who were Alzheimer’s dementia amyloid-β-positive exhibited tau accumulation in Braak regions III–VI but not I–II. Cognitively impaired amyloid-β-positive individuals that were Braak II–IV at baseline displayed a 4.6–7.5% annual increase in tau accumulation in the Braak III–IV regions, whereas those who were cognitively impaired amyloid-β-positive Braak V–VI at baseline showed an 8.3–10.7% annual increase in the Braak regions V–VI. Neuropathological assessments confirmed PET-based Braak stages V–VI in the two brain donors.

Our results suggest that the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR is able to detect longitudinal tau accumulation in asymptomatic and symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. The highest magnitude of 18F-MK-6240 SUVR accumulation moved from the medial temporal to sensorimotor cortex across the disease clinical spectrum. Trials using the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR in cognitively unimpaired individuals would be required to use regions of interest corresponding to early Braak stages, whereas trials in cognitively impaired subjects would benefit from using regions of interest associated with late Braak stages. Anti-tau trials should take into consideration an individual’s baseline PET Braak-like stage to minimize the variability introduced by the hierarchical accumulation of tau tangles in the human brain. Finally, our post-mortem findings supported use of the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR as a biomarker to stage tau pathology in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: neurofibrillary tangles, tau pathology, Braak stages, Alzheimer’s disease, positron emission tomography

Pascoal et al. show that 18F-MK-6240, a second-generation PET tracer with submolar affinity for tau tangles, can reveal longitudinal tau accumulation in individuals in early and late Braak stages of tau accumulation. Post-mortem examination confirmed 18F-MK-6240 as a robust marker to stage in vivo tau pathology.

Introduction

Tau neurofibrillary tangles accumulation is a key neuropathological feature of Alzheimer’s disease.1 Post-mortem studies suggest that tau tangles follow a stereotypical pattern of deposition known as Braak stages that suggest that early stages of tau accumulation can occur even in the absence of prominent amyloid-β pathology.2,3 Cross-sectional tau PET studies have shown high performance in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and revealed patterns of tracer uptake similar to those reported in post-mortem series.4-6 Tracking longitudinal tau accumulation in living people is crucial for a better understanding of the dynamic interactions of tau accumulation with amyloid-β, neurodegeneration and cognitive decline and for testing drug effects on tau deposition over time.7–9

Using post-mortem data, Braak proposed a framework in which tau accumulation begins in the transentorhinal cortex, spreads to the entorhinal and hippocampal cortices, the temporal neocortex, and finally association and sensorimotor cortices.2,10,11 Based on these cross-sectional post-mortem observations, one may hypothesize that longitudinal tau accumulation in living people would follow these same stages in a hierarchical fashion, with predominant tau deposition in the transentorhinal/entorhinal cortices in cognitively unimpaired individuals and in association and sensorimotor neocortices in cognitively impaired individuals. Some previous longitudinal studies using the first-generation tau tracer 18F-flortaucipir showed negligible tau accumulation in early Braak stages in the cognitively unimpaired and relatively homogeneous tau accumulation across the brain cortex in cognitively impaired individuals.12–15 However, recent 18F-flortaucipir studies suggest significant tau accumulation in regions comprising late Braak stages in cognitively impaired subjects,16 as well as the possibility of tau accumulation in the absence of preeminent amyloid-β pathology.15

Recently, second-generation tau imaging agents were developed to minimize brain off-target binding and increase sensitivity to tau neurofibrillary tangles. PET imaging agents with greater affinity to their targets are expected to present a higher dynamic range and, consequently, a higher rate of longitudinal progression compared with those with lower affinity. 18F-MK-6240 is a second-generation tau imaging agent with subnanomolar affinity,17 favourable kinetics18 and high sensitivity to tau neurofibrillary tangles in clinical populations.5 In the present study, we aimed to assess the longitudinal progression of tau pathology measured using the 18F-MK-6240 standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) in ageing and across the clinical spectrum of Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, we measured post-mortem tau pathology in two patients with dementia who underwent 18F-MK-6240 scans before death. Because of its high affinity to tau tangles, we hypothesized that 18F-MK-6240 can detect longitudinal tau deposition from the early PET Braak-like stages in the transentorhinal/entorhinal cortices in cognitively unimpaired individuals to the late Braak stages in the sensorimotor neocortex in cognitively impaired individuals. Moreover, we hypothesized that in vivo18F-MK-6240 SUVR and post-mortem tau neuropathology measurements show similar regional distributions.

Materials and methods

Participants

We longitudinally assessed 87 cognitively unimpaired elderly subjects, 21 with mild cognitive impairment and amyloid-β pathology (MCI Aβ+) and 17 patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia and were amyloid-β-positive, who were either from the community or outpatients at the McGill University Research Centre for Studies in Ageing enrolled in the Translational Biomarkers of Aging and Dementia (TRIAD) cohort with amyloid-β PET and 18F-AZD4694 at baseline and MRI and tau PET with 18F-MK-6240 at baseline and follow-up visits. The participants undertook detailed cognitive and clinical and cognitive assessments, including the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and neuropsychological tests for memory, attention, executive function, visuospatial processing, psychomotor speed processing and language. Taking into account the clinical presentation, physical examination and aforementioned tests, a multidisciplinary team, including physicians, nurses and neuropsychologists, provided a consensus diagnosis for all participants. Cognitively unimpaired individuals showed no objective cognitive impairment, had a CDR score of 0 and were asked to report any subjective cognitive decline in a questionnaire given during screening.19 Patients with MCI had subjective and objective cognitive impairment, relatively preserved activities of daily living and a CDR score of 0.5. Patients with mild-to-moderate sporadic Alzheimer’s disease dementia had a CDR score of between 0.5 and 2 and met the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association criteria for probable Alzheimer’s disease as determined by a physician.20 As the purpose of the present study was to assess cognitive impairment in the Alzheimer’s disease continuum, cognitively impaired participants (with MCI or Alzheimer’s disease dementia) were required to have an abnormal amyloid-β PET scan, similar to previous studies.12 Participants were not enrolled in the present study if they had other neurological, psychiatric or systemic conditions, which were not adequately controlled through a stable medication regimen, active substance abuse, recent head trauma or major surgery or if they had MRI or PET safety contraindications. The participants did not discontinue any medication to participate in this study. Although neurological and psychiatric comorbidities are exclusion criteria for the TRIAD cohort, participants who were cognitively unimpaired or had MCI or Alzheimer’s disease dementia and took selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors without a current diagnosis of depression were enrolled. Cholinesterase inhibitors were the most prescribed medications in our mild/moderate Alzheimer’s disease dementia population. Almost no patients were on memantine or antipsychotics. The study was approved by the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) PET working committee and the Douglas Mental Health University Institute Research Ethics Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Imaging methods

Study participants had a T1-weighted MRI (3 T, Siemens), and 18F-AZD4694 PET and 18F-MK-6240 PET scans were acquired using the same brain-dedicated Siemens high resolution research tomograph. 18F-MK-6240 PET images were acquired at 90–110 min after intravenous bolus injection of the radiotracer and reconstructed using an ordered subset expectation maximization (OSEM) algorithm on a 4D volume with four frames (4 × 300 s) as previously described.1818F-AZD4694 PET images were acquired at 40–70 min after the intravenous bolus injection of the radiotracer and reconstructed with the same OSEM algorithm on a 4D volume with three frames (3 × 600 s).18 A 6-min transmission scan with a rotating 137Cs point source was conducted at the end of each PET acquisition for attenuation correction. Images were corrected for motion, decay, dead time and random and scattered coincidences. Briefly, PET images were automatically registered to a T1-weighted image space and were linearly and non-linearly registered to the MNI reference space.21 Importantly, 18F-MK-6240 images were meninges stripped in native space before transformations or blurring to minimize the influence of meningeal spillover in adjacent brain regions as described elsewhere.5 PET images were linearly and non-linearly registered to the MNI space using the transformations from the T1-weighted image to MNI space and from the PET image to T1-weighted image space. The 18F-MK-6240 SUVR and 18F-AZD4694 SUVR used the cerebellar crus I grey matter derived from the SUIT cerebellum atlas22 and the whole cerebellum grey matter as the reference regions, respectively.23 The cerebellar crus was used for longitudinal analyses in previous tau PET studies.12 PET images were spatially smoothed to achieve an 8-mm full-width at half-maximum resolution. The transentorhinal cortex was segmented in the stereotaxic space on 1 mm isotropic voxels5 using a well-validated MRI segmentation technique and identifiable anatomical landmarks.24–26 The transentorhinal region of interest was segmented in the medial bank of the rhinal sulcus, which is the topography of the transition area between the entorhinal and perirhinal cortices.27 There was no overlap between transentorhinal and entorhinal regions of interest and the peak of their probabilistic distributions were 14 mm apart, which corresponds to approximately 2 full-width at half-maximum of the resolution of the PET scanners. However, as their edges were as close as 2 mm in some slices, we expected some underestimation of differences in tau accumulation between these two regions due to the limited spatial resolution of PET (Supplementary Fig. 1). PET Braak-like region segmentation was previously described elsewhere.5 PET Braak-like stages were defined based on previous post-mortem observations2,3 and PET studies5,6 as follows: Braak I (transentorhinal), Braak II (entorhinal and hippocampus), Braak III (amygdala, parahippocampal gyrus, fusiform gyrus and lingual gyrus), Braak IV (insula, inferior temporal, lateral temporal, posterior cingulate and inferior parietal), Braak V (orbitofrontal, superior temporal, inferior frontal, cuneus, anterior cingulate, supramarginal gyrus, lateral occipital, precuneus, superior parietal, superior frontal and rostro medial frontal) and Braak VI (paracentral, postcentral, precentral and pericalcarine) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The Desikan-Killiany-Tourville atlas was used to define the regions of interest for the PET Braak-like stages.28 We also assessed 18F-MK-6240 progression in previously defined meta-regions of interest.12 The early Alzheimer’s disease (fusiform gyrus and posterior cingulate), late Alzheimer’s disease (inferior temporal, superior orbital frontal, basal frontal and middle occipital), temporal lobe composite and whole brain composite meta-regions of interest used brain regions derived from the MCALT_ADIR122 atlas as previously described.12 The global 18F-AZD4694 SUVR composite included the precuneus, prefrontal, orbitofrontal, parietal, temporal and cingulate cortices.2918F-AZD4694 SUVR positivity was determined as an SUVR > 1.55 (centiloid30 22) as detailed elsewhere.31 A baseline Braak stage was defined hierarchically for each subject, where each individual had one Braak stage corresponding to the latest stage, and a later stage was achieved if the individual was positive for the previous stages. Tau positivity in Braak regions was defined using cutoffs determined as 2.5 standard deviations (SD) higher than the mean SUVR of cognitively unimpaired young individuals as previously described.5 The data presented in this manuscript were not corrected for partial volume effects.

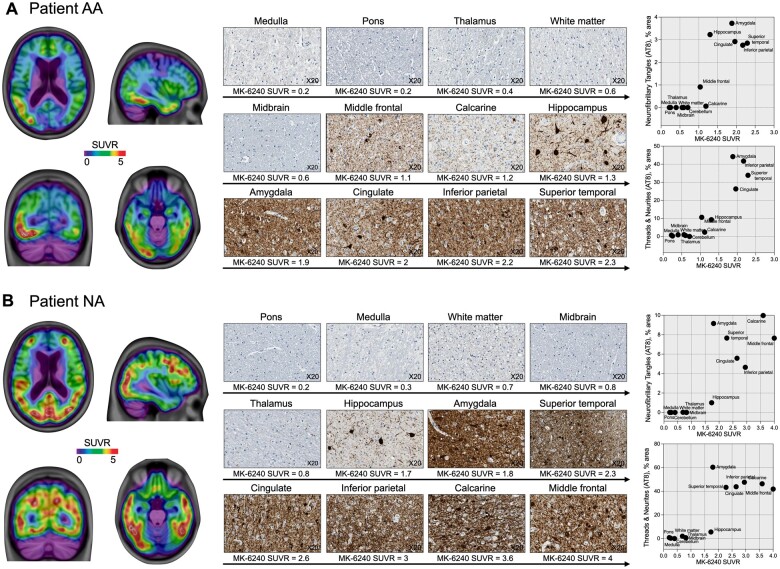

In vivo–in vitro analysis of 18F-MK-6240 SUVR and phosphorylated tau

We performed a post-mortem analysis of phosphorylated tau (AT8) pathology in two brain donors who had 18F-MK-6240 scans prior to death. Patient AA was 85-years-old, APOE ε4-negative (ε3/ε3), male, with no parental family history of dementia, who had received a clinical diagnosis of sporadic late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (MMSE score of 12 and CDR score of 1) and had a Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) C1 score. Patient AA died 12 months after the 18F-MK-6240 scan. Patient NA was 63-years-old, APOE ε4 positive (ε3/ε4), female, with no parental family history of dementia, who had received a clinical diagnosis of sporadic early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (MMSE score of 12 and CDR score of 1). Patient NA died 22 months after the 18F-MK-6240 scan and had a CERAD C3 score. Both study participants had their brains examined by experienced neuropathologists, were Braak staged and received the neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease.32 The neuroanatomical regions used in the analysis [hippocampus (Braak II), amygdala (Braak III), cingulate and inferior parietal (Braak IV), superior temporal and middle frontal (Braak V) and calcarine (Braak VI) cortices as well as pons, midbrain, medulla, cerebellum vermis, thalamus and white matter] were based on the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease.33 Based on previous literature,34 to ensure accurate positioning of these brain regions to measure the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR, we indicated the areas to be assessed simultaneously in the patients’ structure MRI and post-mortem brain tissue. Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded 5-µm sections using a Ventana Discovery Ultra automatic stainer. The Ventana staining protocol included a 24-min pretreatment with Cell Conditioner 1 (Ventana), followed by incubation with the primary antibody for 60 min. The antibody was diluted in Ventana dilution buffer as follows: AT8 (phosphor-Tau Ser202, Thr205, Invitrogen) 1/1000.35 Detection was performed using Discovery OmniMap DAB anti Ms RUO (Ventana). The slides were scanned at ×20 on an Aperio ScanScope XP and captured using AperioImageScope software. One section per region was analysed for tau density. The images were converted to 8-bit greyscale [1–255] using ImageJ software version 1.52k (https://imagej.nih.gov; accessed 22 November 2021). The threshold to eliminate background was determined based on the cerebellar cortex, including a greyscale intensity <110 for total tau AT8 positivity. Tau tangles were identified with a greyscale threshold of <30 and visually expected to identify tangles and pretangles.36 Then, the images were binarized, and the percent area immunostained was assessed. Additionally, ET3 antibody (Dr Peter Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NY) was used to detect four-repeat (4R) tau, anti-phospho TDP-43 pS409/410–2 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Cosmo-Bio) to detect TDP-43 and clone LB509 mouse monoclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher) to detect α-synuclein.

Statistical methods

The statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software version 3.1.2 (http://www.r-project.org/; accessed 22 November 2021). We used voxel-wise paired t-test, family-wise error (FWE) rate corrected for multiple comparisons at P < 0.05, to test the presence of significant longitudinal changes in 18F-MK-6240 SUVR at every brain voxel in the clinical groups. We measured the annual change in 18F-MK-6240 SUVR as the difference between the follow-up and baseline uptakes divided by the time duration between scans (Equation 1):

| (1) |

and the annual percentage of change in 18F-MK-6240 uptake as the difference between the follow-up and baseline uptakes divided by the baseline uptake and time duration between scans (Equation 2):

| (2) |

We calculated the mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) of the annual change in the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR in the clinical groups. The coefficient of variation was calculated as the group standard deviation divided by the mean. A generalized linear mixed effect repeated measures analysis was performed with one fixed factor, Braak stage region and a random subject effect to account for within-subject correlation. The response variable was the annual percentage of change in 18F-MK-6240 SUVR. We present bar plots with the mean percentage of change in 18F-MK-6240 SUVR across Braak stages and indicated the statistical significance derived from the paired differences tests from the repeated measures model. The effects of age and sex were tested by comparing the models with and without these variables via chi-square likelihood ratio tests.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon request.

Results

Participants

We studied 125 individuals [65 cognitively unimpaired elderly patients without amyloid-β pathology (CU Aβ−), 22 cognitively unimpaired elderly with amyoid-β pathology (CU Aβ+), 21 MCI amyloid-β-positive (MCI Aβ+) and 17 Alzheimer’s disease dementia amyloid-β-positive (AD Aβ+) participants] with baseline and 1-year (mean = 1.16, SD 0.33) follow-up visits. Fifty-one per cent (33/65) of elderly CU Aβ− and 68% (15/22) of elderly CU Aβ+ subjects had subjective cognitive decline. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the population. Two participants with Alzheimer’s disease dementia who died during the study donated their brains for the in vivo post-mortem analysis.

Table 1.

Demographics and key characteristics of the population

| Characteristic | CU Aβ− | CU Aβ+ | MCI Aβ+ | AD Aβ+ | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 65 | 22 | 21 | 17 | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 70.7 (6.5) | 72.8 (6.2)# | 74 (5.4)# | 68 (7.4) | 0.008 |

| Male, number (%) | 22 (34) | 6 (28) | 15 (71)*,† | 10 (59) | 0.004 |

| Education, years, mean (SD) | 15.3 (3.7) | 15 (3.9) | 14.4 (3.8) | 15.2 (3.8) | 0.840 |

| MMSE score, mean (SD) | 29.1 (1.3) | 28.8 (1.3)# | 26.8 (3.7)*,# | 20.7 (6.5)* | <0.001 |

| APOE ε4, number (%) | 20 (31) | 6 (27) | 9 (43) | 7 (41) | 0.599 |

| Amyloid-β PET, SUVR, mean (SD) | 1.24 (0.08) | 1.82 (0.32)*,# | 2.02 (0.5)*,# | 2.58 (0.43)* | <0.001 |

| Scan interval, years, mean (SD) | 1.12 (0.2) | 1.08 (0.2) | 1.25 (0.3) | 1.31 (0.5) | 0.054 |

The P-values indicate the results of the ANOVA testing significant differences between groups for continuous variables, except for sex and APOE ε4, where a contingency chi-square was performed. Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis provided significant differences between groups.

P < 0.05 compared with CU Aβ−.

P < 0.05 compared with CU Aβ+.

P < 0.05 compared with AD Aβ+.

Voxel-wise longitudinal 18F-MK-6240 accumulation

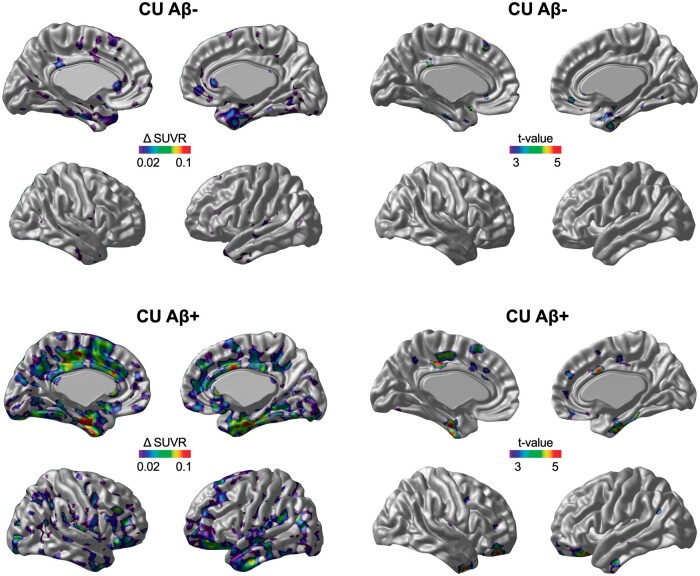

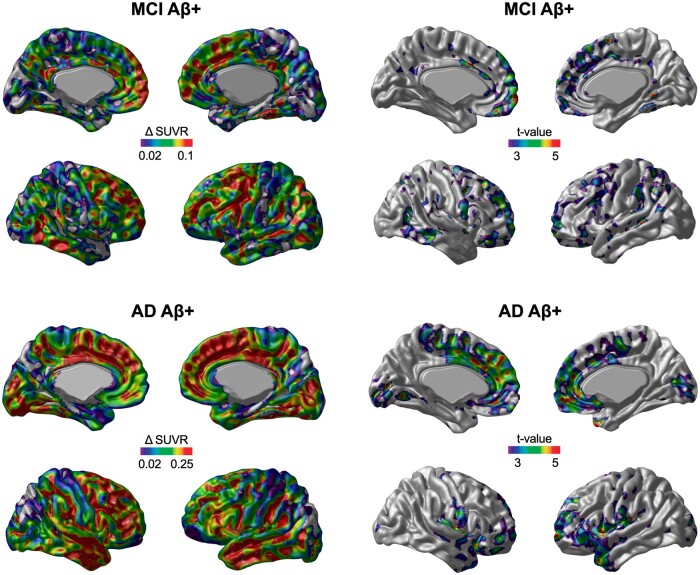

The voxel-wise annual rate of tau accumulation and t statistical maps revealed 18F-MK-6240 SUVR deposition in CU Aβ− individuals in the transentorhinal and entorhinal cortices (Fig. 1). CU Aβ+ individuals showed tau accumulation in the transentorhinal and entorhinal cortices and exhibited tau accumulation in clusters in the posterior cingulate, precuneus and basal and lateral temporal cortices (Fig. 1). MCI Aβ+ subjects presented significant tau deposition in the lateral temporal, posterior cingulate, lateral occipital and frontal cortices but not in the medial temporal cortex (Fig. 2). AD Aβ+ subjects showed significant tau accumulation in the temporal pole, frontal and medial occipital cortices but not in the medial temporal, posterior cingulate and precuneus cortices (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

The area and magnitude of longitudinal 18F-MK-6240 SUVR accumulation in cognitively unimpaired individuals segregated by amyloid-β status. The brain images (left) show the mean annual rate (Δ) of change in the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR overlaid on a structural MRI template. The brain images (right) show the results of the voxel-wise paired t-test comparison (FWE rate corrected for multiple comparisons at P < 0.05) between the baseline and follow-up 18F-MK-6240 SUVR scans.

Figure 2.

The area and magnitude of longitudinal 18F-MK-6240 SUVR accumulation in MCI and patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia. The brain images (left) show the mean annual rate (Δ) of change in the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR overlaid on a structural MRI template. The brain images (right) show the results of the voxel-wise paired t-test comparison (FWE rate corrected for multiple comparisons at P < 0.05) between the baseline and follow-up 18F-MK-6240 SUVR scans.

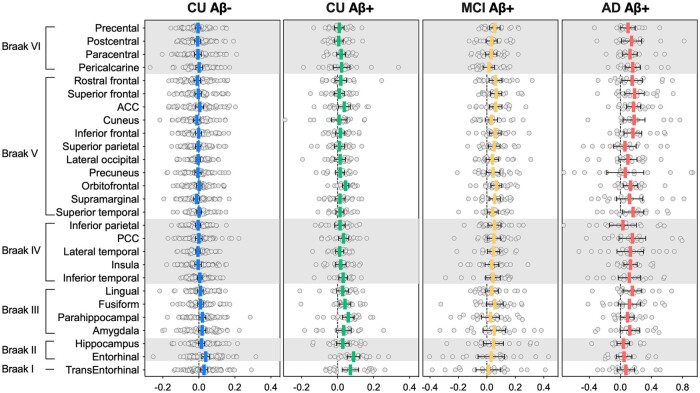

Region of interest-wise longitudinal 18F-MK-6240 accumulation

Using anatomically defined regions of interest, we found that CU Aβ−, CU Aβ+, MCI Aβ+ and AD Aβ+ individuals showed a tendency for a longitudinal increase in the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR mainly in the regions of PET Braak-like stages I–II, I–III, IV–V and V–VI, respectively (Fig. 3). Using composite regions of interest indicating Braak stages, cognitively unimpaired subjects showed a significant annual increase in the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR in regions comprising PET Braak-like stages I and II (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). MCI Aβ+ and AD Aβ+ patients showed a significant annual increase in Braak regions III–VI (Table 2). Using meta-regions of interest defined in previous studies, CU Aβ− subjects showed no significant tau accumulation, whereas CU Aβ+ individuals showed significant tau accumulation in early and late Alzheimer’s disease and temporal meta-regions of interest (Table 2). MCI Aβ+ and AD Aβ+ patients showed significant tau accumulation in late Alzheimer’s disease meta-regions of interest but not in early Alzheimer’s disease and temporal meta-regions of interest (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Annual rates of 18F-MK-6240 SUVR accumulation in clinical groups. The horizontal bars show the mean annual rate of change in the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR with a 95% confidence intervalCI in individuals segregated by amyloid-β status and clinical diagnosis. CU Aβ−, CU Aβ+, MCI Aβ+ and AD Aβ+ individuals showed an increase in 18F-MK-6240 SUVR regions of interest mainly confined to PET Braak-like stages I–II, I–III, IV–V and V–VI, respectively. ACC = anterior cingulate cortex; PCC = posterior cingulate cortex.

Table 2.

Annual rate of change in 18F-MK-6240 SUVR across regions of interest and clinical groups

| Region | CU Aβ− |

CU Aβ+ |

MCI Aβ+ |

AD Aβ+ |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ SUVR mean (SD) | 95% CI | CV | Δ SUVR mean (SD) | 95% CI | CV | Δ SUVR mean (SD) | 95% CI | CV | Δ SUVR mean (SD) | 95% CI | CV | ||

| PET Braak-like stages | |||||||||||||

| Braak I | 0.028 (0.085)a | 0.008, 0.050 | 3 | 0.071 (0.103)a | 0.026, 0.117 | 1.4 | 0.011 (0.194) | −0.076, 0.099 | 18 | 0.072 (0.218) | −0.040, 0.184 | 3 | |

| Braak II (Entorhinal) |

0.038 (0.088)a | 0.016, 0.060 | 2.3 | 0.089 (0.079)a | 0.054, 0.124 | 0.9 | 0.031 (0.204) | −0.062, 0.124 | 6.6 | 0.048 (0.195) | −0.052, 0.148 | 4 | |

| Braak II (Hippocampus) |

0.015 (0.070) | −0.003, 0.032 | 4.7 | 0.029 (0.079) | −0.006, 0.064 | 2.7 | 0.047 (0.153) | −0.033, 0.117 | 3.3 | 0.038 (0.160) | −0.044, 0.121 | 4.2 | |

| Braak III | 0.008 (0.063) | −0.007, 0.024 | 7.9 | 0.034 (0.069) | 0.003, 0.065 | 2.0 | 0.044 (0.095) | 0.000, 0.087 | 2.2 | 0.139 (0.234) | 0.020, 0.260 | 1.7 | |

| Braak IV | 0.001 (0.058) | −0.013, 0.015 | 58 | 0.026 (0.055) | 0.002, 0.051 | 2.2 | 0.049 (0.092) | 0.006, 0.090 | 1.9 | 0.141 (0.271) | 0.001, 0.280 | 1.9 | |

| Braak V | −0.003(0.062) | −0.019, 0.012 | −20 | 0.020 (0.047) | −0.001, 0.040 | 2.3 | 0.060 (0.08)* | 0.021, 0.098 | 1.4 | 0.142 (0.268) | 0.004, 0.279 | 1.9 | |

| Braak VI | −0.006(0.066) | −0.022, 0.010 | −11 | 0.015 (0.050) | −0.007, 0.037 | 3.3 | 0.038 (0.081) | 0.001, 0.075 | 2.1 | 0.133 (0.19)* | 0.04, 0.228 | 1.4 | |

| Meta-ROIs | |||||||||||||

| Early AD | 0.012 (0.063) | −0.003, 0.028 | 5.3 | 0.045 (0.061) | 0.019, 0.072 | 1.4 | 0.050 (0.132) | −0.009, 0.111 | 2.6 | 0.123 (0.269) | −0.015, 0.262 | 2.2 | |

| Late AD | 0.002 (0.064) | −0.008, 0.018 | 32 | 0.029 (0.058) | 0.003, 0.055 | 2 | 0.059 (0.096) | 0.029, 0.092 | 1.6 | 0.154 (0.256) | 0.023, 0.287 | 1.7 | |

| Temporal | 0.007 (0.061) | −0.008, 0.022 | 8.7 | 0.034 (0.060) | 0.006, 0.013 | 1.8 | 0.051 (0.124) | −0.006, 0.107 | 2.4 | 0.144 (0.303) | −0.012, 0.299 | 2.1 | |

| Whole brain | −0.001(0.055) | −0.014, 0.013 | −55 | 0.019 (0.044) | −0.000, 0.039 | 2.3 | 0.047 (0.073) | 0.015, 0.080 | 1.6 | 0.122 (0.222) | 0.007, 0.236 | 1.8 | |

The mean and standard deviation (SD) of the annual rate (Δ) of change in the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR with the respective 95% confidence interval (CI) and changes in non-partial volume corrected 18F-MK-6240 SUVR values quantified at 90–100 min post-injection using the cerebellar crus I as the reference region. The coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated as the ratio of the SD to the mean. The lower the CV, the smaller the variability of the measure, which indicates a more precise estimate. AD = Alzheimer’s disease; ROIs = regions of interest.

Regions that tau change survived Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison.

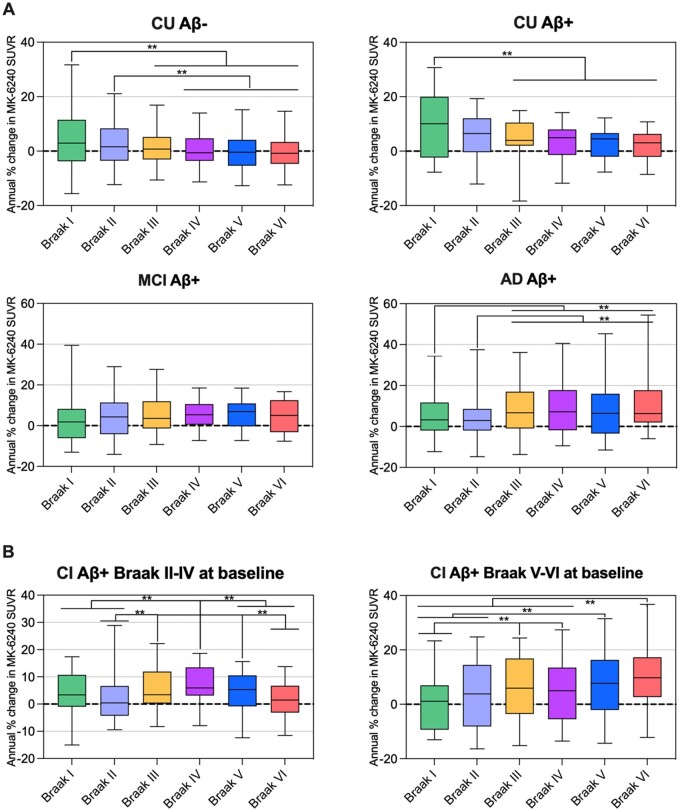

CU Aβ− and CU Aβ+ individuals showed an average annual percentage of increase in tau accumulation in the Braak I region of 4% and 9%, respectively, which was higher than the changes in the latest Braak stages (Fig. 4). Cognitively impaired (CI) Aβ+ Braak II–IV patients (at baseline) presented higher annual tau deposition in Braak regions III–V (4.6–7.5%) than in Braak regions II (3%) and VI (1.6%) (Fig. 4). CI Aβ+ Braak V–VI patients (at baseline) showed higher tau accumulation in Braak regions V (8.3%) and VI (10.7%) than in Braak regions I (0.4%) and II (3.4%) (Fig. 4). The derived plots from the estimated differences with the respective 95% confidence interval obtained from the repeated measure analysis are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. Age and sex were not significant in the models aforementioned. Estimated differences corrected for age and sex as well as a more conservative 99% confidence interval are shown in Supplementary Tables 2–7.

Figure 4.

Longitudinal patterns of 18F-MK-6240 SUVR accumulation in individuals across the ageing and Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Box plots showing the quartiles, 5th and 95th percentiles (whiskers) of the annual percentage of change in 18F-MK-6240 SUVRs in different Braak-related areas in individuals segregated based on their baseline cognition, amyloid-β status and Braak stage [CU Aβ− (n = 65), CU Aβ+ (n = 22) and MCI Aβ+ (n = 21), AD Aβ+ (n = 17), CI Aβ+ and Braak II–IV (n = 20) and CI Aβ+ and Braak V–VI (n = 18)]. Statistical differences between groups were derived from the estimated differences between the means from the repeated measures analysis and the significant differences are indicated with **P < 0.05. The comparisons that survived a strict Bonferroni correction considering all the comparisons shown in the figure were: CU Aβ− (Braak I–IV, I–V and I–VI), CU Aβ+ (Braak I–IV), AD Aβ+ (Braak I–VI and II–VI), CI Aβ+ and Braak II–IV at baseline (Braak II–IV and IV–VI), CI Aβ+ and Braak V–VI at baseline (Braak I–III, I–V, I–VI and II–VI). (A) Cognitively unimpaired participants showed higher 18F-MK-6240 SUVR accumulation in PET Braak-like stage I than in the latest PET Braak-like stages, MCI Aβ+ individuals did not present differences in the rates of progression across Braak regions and AD Aβ+ patients showed lower tau increases in Braak regions I–II than in the later Braak regions. (B) We also assessed cognitively impaired individuals segregated based on their baseline Braak stage. CI Aβ+ Braak II–IV individuals at baseline showed higher tau accumulation in Braak regions III–V than in regions II and VI, whereas CI Aβ+ Braak V–VI individuals at baseline showed higher tau accumulation in Braak VI than in Braak regions I–IV. CI = cognitively impaired with MCI or Alzheimer’s disease dementia.

In vivo 18F-MK-6240 SUVR and post-mortem tau pathology

Both patients showed a similar regional distribution of tau pathology using in vivo PET and post-mortem neuropathology assessments. Specifically, Patient AA (85 years old) presented tau tangles pathology classified as Braak stage V using both an in vivo PET scan and post-mortem AT8 antibody test (Fig. 5A). Similarly, Patient NA (63 years old) was tau tangles-positive and Braak stage VI using PET and post-mortem data (Fig. 5B). In Patient AA, we also found intraneuronal accumulation of 4R tau in rare neurons in the frontal cortex and cingulate gyrus and in numerous neurons in the entorhinal cortex and subiculum. Patient NA showed focal intraneuronal accumulation of 4R tau in neurons in the frontal, inferior parietal and occipital cortices, and numerous positive neurons in the entorhinal cortex and subiculum. The post-mortem distribution of 4R tau pathology did not resemble the in vivo distribution of 18F-MK-6240 SUVR in either case. We did not observe α-synuclein and TDP-43 pathologies in the amygdala, dentate gyrus, subiculum, entorhinal cortex or neocortex in either patient.

Figure 5.

In vivo 18F-MK-6240 SUVR and post-mortem tau neuropathology in two patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia. 18F-MK-6240 SUVR images acquired prior to the patients’ deaths (left), immunohistochemistry panels with AT8 staining (middle) and plots (right) with 18F-MK-6240 SUVR. AT8 staining density of neurofibrillary tangles (top) and the combination of neuropil threads and dystrophic neurites surrounding amyloid-β plaques (bottom). (A) Patient AA (MMSE = 12, CDR = 1, male, 85 years- old, late-onset sporadic Alzheimer’s disease) had an 18F-MK-6240 scan 12 months prior to death. Immunohistochemistry showed relevant tau tangles pathology in the hippocampus (Braak II), amygdala (Braak III), cingulate and inferior parietal (Braak IV) and superior temporal (Braak V) cortices but not in the calcarine cortex (Braak VI). Patient AA was classified as Braak stage V using both PET and post-mortem data. (B) Patient NA (MMSE = 12, CDR = 1, female, 63 years old, early-onset sporadic Alzheimer’s disease) had an 18F-MK-6240 scan 22 months prior to death. Immunohistochemistry showed tau tangles pathology across the brain cortex. Patient AA was classified as Braak stage VI using PET and post-mortem data.

Discussion

The 18F-MK-6240 SUVR detected longitudinal tau accumulation in early PET Braak-like regions in asymptomatic subjects and late Braak regions in symptomatic individuals. Our results suggested that the longitudinal patterns of 18F-MK-6240 accumulation hierarchically follow similar stages to those precited by Braak in cross-section autopsies across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Post-mortem data collected from two participants with Alzheimer’s disease who died during the study provided insights into the similarities between tau accumulation patterns assessed antemortem with 18F-MK-6240 PET and post-mortem with neuropathology.

The pattern of the longitudinal accumulation of 18F-MK-6240 SUVRs demonstrated in this study is consistent with that postulated by previous cross-sectional autopsies.2 We found that cognitively unimpaired individuals had an increase in tracer uptake in regions corresponding to PET Braak-like stages I–II, whereas patients with MCI or Alzheimer’s disease dementia showed significant tau deposition in regions comprising Braak III–VI. Individuals with MCI did not exhibit significant difference in the rates of progression through the Braak stages. This was likely due to the fact that this was a heterogeneous group in terms of tau deposition, with individuals in the early and late stages. Individuals with MCI showed no significant differences in the rates of tau accumulation across the different PET Braak-like regions. This more uniform pattern of tau accumulation across Braak regions was likely because the MCI group was heterogeneous, with some individuals in the early stages and others in the late stages of tau deposition. When we segregated the cognitively impaired individuals based on their baseline Braak stage of tau deposition, we found that CI Aβ+ Braak II–IV patients at baseline showed tau accumulation in Braak regions III–V, whereas CI Aβ+ Braak V–VI patients at baseline showed tau accumulation in Braak regions V–VI. Taken together, these results support that the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR longitudinally accumulates in a pattern similar to the stereotypical spread proposed by Braak in a post-mortem series.2 Our longitudinal results are also in line with cross-sectional tau PET studies suggesting that tau pathology accumulates in a Braak stage-like pattern.5,37–39 The above-mentioned results contrast with some previous 18F-flortaucipir findings suggesting negligible tau accumulation in the transentorhinal, entorhinal or hippocampal cortices in cognitively unimpaired individuals and relatively homogeneous tau accumulation across the brain cortex in cognitively impaired individuals.12 Still, one may argue that 18F-flortaucipir studies showing that low global tracer uptake is associated with tau accumulation predominantly in temporal regions14 that regions comprising different Braak stages show different rates of tracer accumulation16 and that tau accumulation may be present in the absence of preeminent amyloid-β pathology support our findings.15

18F-MK-6240 detected significant longitudinal tau accumulation in asymptomatic and symptomatic subjects. Specifically, we found that CU Aβ− and CU Aβ+ individuals showed 2–4% and 5–9% annual rates of tau accumulation in early PET Braak-like regions, respectively, whereas individuals with cognitive impairment that were amyloid-β-positive and Braak stage II–IV and IV–V at baseline showed 5–7% and 8–11% annual increases in the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR in late Braak regions, respectively. Partial volume correction of the SUVR estimates invariably increased the longitudinal rates of tau accumulation in previous tau PET studies,12,15,16 because it adjusted the SUVR values for a possible artefactual reduction in tracer uptake associated with a longitudinal reduction in brain volume. Since there is no gold standard method for partial volume correction, we presented SUVR estimates without adjustment for volume effects. Some previous longitudinal studies using 18F-flortaucipir suggested negligible 1-year tau deposition in CU Aβ− individuals and ∼0.5% and ∼3% increase in tracer uptake in CU Aβ+ and CI Aβ+ individuals, respectively.12,14 Recently, Cho and colleagues,16 measuring a 2-year change in 18F-flortaucipir SUVR estimates uncorrected for partial volume effects with the cerebellar crus as the reference, found negligible accumulation in CU Aβ− patients, a 2.1% increase in Braak I–II in CU Aβ+ patients and 4.1% and 6.9% increases in Braak III–IV in MCI and AD Aβ+ patients, respectively. Using 18F-flortaucipir SUVR values adjusted for partial volume effects, they found that CU Aβ− and CU Aβ+ patients showed 1.8% and 6.6% increases over a 2-year period in Braak regions I––II, respectively. MCI Aβ+ individuals showed a 9.3% increase in Braak regions I–II, whereas AD Aβ+ individuals showed an 11.2% increase in Braak regions III–IV over 2 years.16 Furthermore, Harrison and colleagues15 showed with partial volume corrected data that cognitively unimpaired individuals had similar annual rates of 18F-flortaucipir SUVR accumulation across cortical regions, with the highest numerical value in the retrosplenial cortex (4.45%), whereas AD Aβ+ individuals had the highest numerical increase in the inferior frontal gyrus (7.34%). The fact that no difference was found between the rates of tau deposition in CU Aβ− and CU Aβ+ individuals in this study supported that the 18F-flortaucipir SUVR was able to detect tau accumulation in the absence of brain amyloidosis.15 Together, these results support use of the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR as an option for research cohorts and clinical trials designed to capture longitudinal changes in tau accumulation in asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals.

Our results suggest that the presence of prominent amyloid-β deposition potentiates longitudinal 18F-MK-6240 accumulation. The fact that CU Aβ− and CU Aβ+ individuals had similar longitudinal patterns of tau accumulation but distinct magnitudes of deposition in the transentorhinal, entorhinal and hippocampal cortices suggests that amyloid-β pathology potentiates age-related tau accumulation in these regions. This supports the notion that amyloid-β pathology has an upstream effect on tau accumulation leading to Alzheimer’s disease progression.8 Tau accumulation in CU Aβ− individuals was confined to temporal regions, supporting that the propagation of tau outside the temporal lobe is generally associated with the presence of amyloid-β pathology.40,41

The results presented here have implications for clinical trials. The longitudinal hierarchical accumulation of tau in Braak-like stages reported here suggests that the optimization of current strategies to quantify tau progression using PET could improve the accuracy of the assessment of drug effects in clinical trials. For example, our results suggested that if two CI Aβ+ individuals with baseline PET Braak stages II–IV and V–VI are enrolled in a 1-year trial using changes in 18F-MK-6240 SUVR in a region of interest in Braak region VI as the surrogate, the cognitively impaired Braak II–IV individual would present negligible tau deposition in this region, which could be confused with a drug effect. These findings highlight that trials should take into account patients’ baseline Braak stages in their tau progression models in order not to confuse hierarchical tau accumulation with a successful end point. The selection of individuals with a similar baseline Braak stage could minimize the bias introduced by the regional variability in tau deposition that is inherently presented by individuals who are in different stages of tau accumulation. The Braak-like progression of the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR also suggests that the selection of stage-specific regions of interest to measure tau accumulation could maximize the rates of tau deposition in clinical groups. For instance, trials using the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR as a surrogate in cognitively unimpaired individuals would benefit from using target regions of interest in Braak regions I–II, whereas trials in cognitively impaired individuals should avoid Braak regions I–II and consider target regions in later Braak stage areas.

The in vivo18F-MK-6240 SUVR and post-mortem phosphorylated tau pathology showed comparable regional distributions in the two patients with sporadic Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Both individuals had the same Braak-like stages assessed with in vivo PET and post-mortem neuropathology. The in vivo18F-MK-6240 SUVR resembled the post-mortem distribution of both tau neurofibrillary tangles (tangles and pretangles) and neuropil threads and dystrophic neurites surrounding amyloid-β plaques.1,42 Neuropil threads are the primary constituents of the total tau burden in the brain, and other tau forms also play an important role.43 Thus, future post-mortem studies with a larger number of individuals should further address the contributions of other tau forms such as neuropil threads, dystrophic neurite and aging-related tau astrogliopathy for the 18F-MK-6240 signal. Our results are in line with 18F-MK-6240 autoradiography observations44 and with results previously reported for 18F-flortaucipir.34 These findings support use of the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR as an in vivo measurement of tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease.

A strength of this study is that we measured tau accumulation in established anatomical brain regions and composites of regions derived from post-mortem observations, rather than using tracer optimized meta-regions of interest. This study, however, has limitations. Our post-mortem analysis showed disproportionately higher levels of AT8 tau pathology in the amygdala in relation to the in vivo18F-MK-6240 SUVR in Patient NA. This can be explained in several ways. For example, it is possible that during the period (22 months) between the patient’s 18F-MK-6240 scan and death, rapid deposition of tau in the amygdala occurred. Also, it may indicate the presence of large amounts of tau deposits that can be detected by the AT8 antibody but not by the 18F-MK-6240 tracer in this region. It is important to emphasize that our post-mortem study was conducted in two individuals in the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Thus, it would be highly desirable to expand our results to a larger in vivo post-mortem cohort using a greater number of tau antibodies across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum to elucidate the association of in vivo18F-MK-6240 uptake and post-mortem tau pathology in individuals in the early stages of tau accumulation. The final resolution of our PET images was 8-mm full-width at half maximum, which limited the quantification of small regions such as the transentorhinal cortex. Thresholds are subject to conceptual and analytical idiosyncrasies and may change depending on the method used in the analysis. We anchored our thresholds in cognitively unimpaired young individuals; thus, the use of a more conservative threshold anchored in cognitively unimpaired elderly individuals could change some of our results. Although a large number of cognitively unimpaired participants had subjective cognitive complaints, we did not consider subjective cognitive decline in our models. To increase similarities between the voxel- and region of interest-wise results, we performed region of interest segmentation in stereotaxic space using non-linearly transformed images for the MNI reference space. In our experience, the 2 mm Jacobian field (deformation) used in our image transformations mitigates some of the well-known anatomical variabilities between subjects such as the one found in the rhinal sulcus. Although brain regions were non-linearly transformed to normalize to the anatomical variabilities, it is possible that analytical methods segmenting each individual in native space can better address these anatomical variabilities providing robust estimates.45 It would be also desirable to replicate our in vivo results using a larger multicentre design with longer follow-up intervals to determine the performance of the tracer in large populations and its sensitivity in detecting subtle increase in tau pathology. However, based on the relatively recent development of 18F-MK-6240, it is likely that the availability of the aforementioned large-scale post-mortem and in vivo data will require more time. Previous studies have shown a higher proportion of APOE ε4 carriers in CU Aβ+ than CU Aβ− individuals.46 Here, we showed a similar proportion of APOE ε4 carries in the above-mentioned groups. In addition, our study had a high proportion of individuals with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease dementia (7/17). These might be explained by the fact that our study included subjects motivated to participate in a study of dementia conducted in a memory clinic environment; therefore, due to the self-selection bias and characteristics of recruitment, our subjects may not represent general populations. The results presented here showed that 18F-MK-6240 longitudinally accumulates in a pattern resembling the topographical distributions proposed by Braak and do not intend to recapitulate Braak histopathological staging, which is a cross-sectional neuropathological construct. Also, our conclusions were based on group-level analysis and do not exclude that some individuals in these groups present different patterns of tau progression unrelated to the Braak stages. Regions showing apparent off-target signals with 18F-MK-6240 included the retina, ethmoid sinus and meninges.18 We cannot entirely exclude some influence of changes in the off-target signals in our results. Also, we cannot exclude that partial volume effects played a role in our results. Some cognitively impaired individuals presented important decreases in the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR over time. Decreases in tau load have been reported using CSF phosphorylated tau47 and in previous longitudinal studies using 18F-flortaucipir.12–16 Although we cannot exclude that the decline in the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR presented here represented a real decline in tau load, we interpreted these results as most likely representing measurement errors associated with the method such as an increase in off-target uptake in the reference region over time. Future studies should address the reasons associated with the decrease in the 18F-MK-6240 SUVR over time presented by some individuals in our population.

To conclude, 18F-MK-6240 showed the ability to detect longitudinal increments of tau tangles pathology in asymptomatic Aβ− and Aβ+ individuals, as well as symptomatic patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Our results provide evidence that tau progresses over time in vivo following the patterns suggested by autopsy studies from the transentorhinal/entorhinal cortices to the sensorimotor neocortex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants of the study and staff of the McGill Center for studies in Aging. We thank Dean Jolly, Alexey Kostikov, Monica Samoila-Lactatus, Karen Ross, Mehdi Boudjemeline and Sandy Li for assisting in the radiochemistry production. We also thank Richard Strauss, Edith Strauss, Guylaine Gagne, Carley Mayhew, Tasha Vinet-Celluci, Karen Wan, Sarah Sbeiti, Meong Jin Joung, Miloudza Olmand, Rim Nazar, Hung-Hsin Hsiao, Reda Bouhachi and Arturo Aliaga for obtaining subject consent and/or helping with data acquisition. We thank Cerveau Technologies for the use of the MK6240.

Funding

This research is supported by the Weston Brain Institute, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) [MOP-11-51-31; RFN 152985, 159815, 162303], Canadian Consortium of Neurodegeneration and Aging (CCNA; MOP-11-51-31 -team 1), Weston Brain Institute, the Alzheimer’s Association [NIRG-12-92090, NIRP-12-259245], Brain Canada Foundation (CFI Project 34874; 33397), the Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS; Chercheur Boursier, 2020-VICO-279314). T.A.P., P.R.-N. and S.G. are members of the CIHR-CCNA Canadian Consortium of Neurodegeneration in Aging. T.A.P. is supported by the Alzheimer's Association (AACSF-20–648075) and National Institute of Aging (R01AG073267).

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Glossary

- AD Aβ+

Alzheimer’s disease dementia with amyloid-β pathology

- CDR

Clinical Dementia Rating; CI Aβ+ = cognitively impaired with MCI or Alzheimer’s disease dementia and amyloid-β pathology; CU Aβ+/− = cognitively unimpaired elderly patients with/without amyloid-β pathology

- MCI Aβ+

mild cognitive impairment with amyloid-β pathology

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- SUVR

standardized uptake value ratio

References

- 1. Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT.. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1(1):a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Braak H, Braak E.. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Braak H, Braak E.. Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18(4):351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schwarz AJ, Yu P, Miller BB, et al. Regional profiles of the candidate tau PET ligand 18F-AV-1451 recapitulate key features of Braak histopathological stages. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 5):1539–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pascoal TA, Therriault J, Benedet AL, et al. 18F-MK-6240 PET for early and late detection of neurofibrillary tangles. Brain. 2020;143(9):2818–2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schöll M, Lockhart SN, Schonhaut DR, et al. PET imaging of tau deposition in the aging human brain. Neuron. 2016;89(5):971–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, Mohades S, et al. ; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Amyloid-beta and hyperphosphorylated tau synergy drives metabolic decline in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(2):306–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jack CR Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: An updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, Shin M, et al. ; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Synergistic interaction between amyloid and tau predicts the progression to dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(6):644–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K.. Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70(11):960–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K.. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112(4):389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jack CR Jr, Wiste HJ, Schwarz CG, et al. Longitudinal tau PET in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2018;141(5):1517–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hanseeuw BJ, Betensky RA, Jacobs HIL, et al. Association of amyloid and tau with cognition in preclinical Alzheimer disease: A longitudinal study. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(8):915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pontecorvo MJ, Devous MD, Kennedy I, et al. A multicentre longitudinal study of flortaucipir (18F) in normal ageing, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease dementia. Brain. 2019;142(6):1723–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harrison TM, La Joie R, Maass A, et al. Longitudinal tau accumulation and atrophy in aging and alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2019;85(2):229–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cho H, Choi JY, Lee HS, et al. Progressive tau accumulation in Alzheimer disease: 2-year follow-up study. J Nucl Med. 2019;60(11):1611–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hostetler ED, Walji AM, Zeng Z, et al. Preclinical characterization of 18F-MK-6240, a promising PET tracer for in vivo quantification of human neurofibrillary tangles. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(10):1599–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pascoal TA, Shin M, Kang MS, et al. In vivo quantification of neurofibrillary tangles with [(18)F]MK-6240. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel M, et al. ; Subjective Cognitive Decline Initiative (SCD-I) Working Group. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(6):844–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mazziotta JC, Toga AW, Evans A, Fox P, Lancaster J; The International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM). A probabilistic atlas of the human brain: Theory and rationale for its development. Neuroimage. 1995;2(2):89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Diedrichsen J, Balsters JH, Flavell J, Cussans E, Ramnani N.. A probabilistic MR atlas of the human cerebellum. Neuroimage. 2009;46(1):39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cselenyi Z, Jonhagen ME, Forsberg A, et al. Clinical validation of 18F-AZD4694, an amyloid-beta-specific PET radioligand. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(3):415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tward DJ, Sicat CS, Brown T, et al. Entorhinal and transentorhinal atrophy in mild cognitive impairment using longitudinal diffeomorphometry. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017;9:41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kulason S, Tward DJ, Brown T, et al. ; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Cortical thickness atrophy in the transentorhinal cortex in mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;21:101617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Insausti R, Juottonen K, Soininen H, et al. MR volumetric analysis of the human entorhinal, perirhinal, and temporopolar cortices. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19(4):659–671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Braak H, Braak E.. On areas of transition between entorhinal allocortex and temporal isocortex in the human brain. Normal morphology and lamina-specific pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1985;68(4):325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Klein A, Tourville J.. 101 labeled brain images and a consistent human cortical labeling protocol. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, Shin M, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Amyloid and tau signatures of brain metabolic decline in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45(6):1021–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Klunk WE, Koeppe RA, Price JC, et al. The Centiloid Project: Standardizing quantitative amyloid plaque estimation by PET. Alzheimer's Dement. 2015;11(1):1-15.e1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Therriault J, Benedet A, Pascoal TA, et al. Determining amyloid-beta positivity using [(18)F]AZD4694 PET imaging. J Nucl Med. 2020;62(2):247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National institute on aging-Alzheimer's association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Association. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathologica. 2012;123(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith R, Wibom M, Pawlik D, Englund E, Hansson O.. Correlation of in vivo [18F]Flortaucipir with postmortem Alzheimer disease tau pathology. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(3):310–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goedert M, Jakes R, Vanmechelen E.. Monoclonal antibody AT8 recognises tau protein phosphorylated at both serine 202 and threonine 205. Neurosci Lett. 1995;189(3):167–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lauckner J, Frey P, Geula C.. Comparative distribution of tau phosphorylated at Ser262 in pre-tangles and tangles. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(6):767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lowe VJ, Wiste HJ, Senjem ML, et al. Widespread brain tau and its association with ageing, Braak stage and Alzheimer's dementia. Brain. 2018;141(1):271–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(1):110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pontecorvo MJ, Devous MD Sr, Navitsky M, et al. ; 18F-AV-1451-A05 investigators. Relationships between flortaucipir PET tau binding and amyloid burden, clinical diagnosis, age and cognition. Brain. 2017;140(3):748–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Villemagne VL, Dore V, Burnham SC, Masters CL, Rowe CC.. Imaging tau and amyloid-beta proteinopathies in Alzheimer disease and other conditions. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(4):225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jagust W. Imaging the evolution and pathophysiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19(11):687–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. He Z, Guo JL, McBride JD, et al. Amyloid-beta plaques enhance Alzheimer's brain tau-seeded pathologies by facilitating neuritic plaque tau aggregation. Nat Med. 2018;24(1):29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mitchell TW, Nissanov J, Han LY, et al. Novel method to quantify neuropil threads in brains from elders with or without cognitive impairment. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48(12):1627–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aguero C, Dhaynaut M, Normandin MD, et al. Autoradiography validation of novel tau PET tracer [F-18]-MK-6240 on human postmortem brain tissue. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yushkevich PA, Pluta JB, Wang H, et al. Automated volumetry and regional thickness analysis of hippocampal subfields and medial temporal cortical structures in mild cognitive impairment. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36(1):258–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, Kang MS, et al. Abeta-induced vulnerability propagates via the brain's default mode network. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fagan AM, Xiong C, Jasielec MS, et al. ; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. Longitudinal change in CSF biomarkers in autosomal-dominant Alzheimer's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(226):226ra30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon request.