Radiologic imaging is a diagnostic tool that greatly affects patient outcomes,[1] and with the recent development of imaging technology, advanced imaging tests such as computed tomography (CT) have gained widespread accessibility in hospitals. In particular, CT is essential in the evaluation of patients in low-level emergency departments (EDs) because of its ability to answer clinical questions accurately and quickly.[2] Therefore, the frequency of patients who are transferred to high-level EDs for treatment after performing CT in a low-level ED is increasing.[3] Thus, it has become important for the patient’s treatment plan to immediately reconfirm the CT image of a transferred patient in the referred ED.[4]

However, previous studies conducted on patients visiting EDs reported significant discrepancies of interpretations between EDs for the same CT image.[3-6] If such a discrepancy is found in the ED, the clinical process could change, and the performance of additional imaging may be required, resulting in unnecessary radiation exposure and an increased cost burden on patients.[7] Moreover, additional imaging studies may lead to prolonged ED length of stay (LOS), in turn causing ED crowding, which can adversely affect the patient’s clinical results and reduce the patient’s satisfaction level.[8,9] Therefore, if the risk factors for discrepancies in the interpretation of CT images of transferred patients are identified in advance, the emergency physicians of the referred hospital could prepare for the changes in the treatment plan caused by the discrepancy. However, previous studies have not been able to reach a clear consensus on the risk factors for discrepancies in the interpretation of CT of transferred patients.[6,7,10,11] Several such risk factors have been recently reported, but systematic results on their identification are lacking.[12-15] Furthermore, no studies have identified how inconsistencies in outside image interpretation affect patient outcomes.[16,17]

Our tertiary ED has an emergency transfer coordination center (ETCC) which coordinates inter-hospital transfers. It provides an appropriate setting for research on the issue of discrepancies in the interpretation of CT. In this setting, the present study aims to identify the risk factors for discrepancies in the interpretation of CT images in patients transferred to a high-level ED and investigate their effects on ED clinical processes.

METHODS

This is a cross-sectional study based on prospectively collected data from an ETCC data bank at an urban tertiary teaching hospital in the Republic of Korea. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.

Our government health authorities designate EDs as level 1, level 2, or level 3, depending on the availability of medical human resources, emergency equipment, and medical services. By law, level 1 and level 2 EDs must have 24-hour emergency medical doctors.[18] The ETCC at our hospital is in a level 1 ED. This ED is located in northwest Seoul (capital of the Republic of Korea) and is responsible for the management of severe patients in its catchment area. Of the approximately 90,000 annual visits to this ED, about 4,000 are patients transferred from other hospitals by emergency medical service (EMS). Approximately 25% of all patients who visit the ED are admitted to our hospital.[19]

In this study, all patients aged 19 years or older who were transferred through the ETCC with CT images obtained from other hospitals between June 2018 and December 2018, were included.

The following cases were excluded: (1) those with CT images (obtained from other hospitals) not transferred to our picture archiving and communication system (PACS); (2) those who were not transferred through the ETCC.

The ETCC is developed to coordinate all emergency transfers to our ED. The ETCC has 6 coordinators and 12 board-certified emergency physicians, and operates 24 hours a day. Using a computerized system, the coordinator continuously monitors the hospital ward capability status, the availability of operating rooms, and the equipment needed for emergency treatment. Based on these data, the ETCC approves patient transfers and manages the related database as a single cohort, recording diagnosis, medical conditions, examination records, and basic information for all patients requested to be transferred from the primary hospital. In addition, for patients who undergo CT, scan time, modality subtype, contrast medium use, and interpretation of CT images from the referring ED are collected prospectively. Our ED has an external image interpretation system in which all external images are immediately sent to the PACS on patient arrival and interpreted by certified radiologists. Therefore, it is possible to immediately detect discrepancies and analyze how they affect the ED clinical process.

For a patient to be transferred to our ED, the coordinator collects the patient’s information, including CT results according to standard protocols, and shares this information, as well as that regarding availability of equipment and hospital bed space, with the emergency medical staff to obtain approval for the transfer. If the input of other departments is needed, the coordinator includes their feedback in the decision-making process. Once approved, the patient is sent to the ED by ambulance or other available means of transportation. The ETCC protocol mandates the approval of transfer provided there is sufficient capacity in the ED; the transfer is denied only when there is overcrowding in the ED or ICU or lack of the required specialist. If primary stabilization is considered a top priority, emergency transfers from catchment areas are approved regardless of the ED capacity.[19]

The study data were extracted from the ETCC transfer registry, which contained prospectively collected data regarding patient age, sex, ED visit time and date, transfer reasons, stage at the referring facility, and CT scan status (CT subtype, CT contrast, reader specialty, and time elapsed from CT scan to ED arrival). In addition, information after arrival at the referred ED was automatically collected through a clinical research analysis portal developed by the medical information department in our hospital.[20] All data were collected by authorized researchers and fed into the hospital information system; they were processed anonymously, with no missing data.

The primary outcome is the presence of discrepancies between the external interpretation and our hospital’s interpretation. A major discrepancy was defined as any disagreement with clinical significance and potential change to the patient treatment plan; a minor discrepancy as any disagreement with no clinical significance; no discrepancy was defined as the absence of disagreement in interpretation according to previous literature.[16] The classification of discrepancies was conducted by two board-certified emergency physicians blinded to the study by reviewing the interpretation records and the patient’s clinical course from medical records. Differences in opinions between the two reviewers (14 cases of inconsistency) were determined through discussion until consensus was reached. In modeling, both minor and major discrepancies were classified as discrepancies. To confirm the effect of discrepancies on the ED clinical process, the present study investigated the time from ED presentation to the disposition of the enrolled patients.

Categorical variables are reported as number and percentage, and continuous variables as mean±standard deviation. Differences between groups were assessed by the Student’s t-test for normally distributed variables and by the Mann-Whitney U-test for the other variables. The Chi-squared test was used to analyze categorical variables. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the risk factors for the primary outcome. Since this study was designed retrospectively and was an exploratory study analyzed using logistic regression, the post power calculation was not performed. The determination of clinically significant factors was based on previous studies.[3,4,5] Analysis of the collected data was performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Inc., USA) and R (version 3.6.3, http://www.R-project.org).

RESULTS

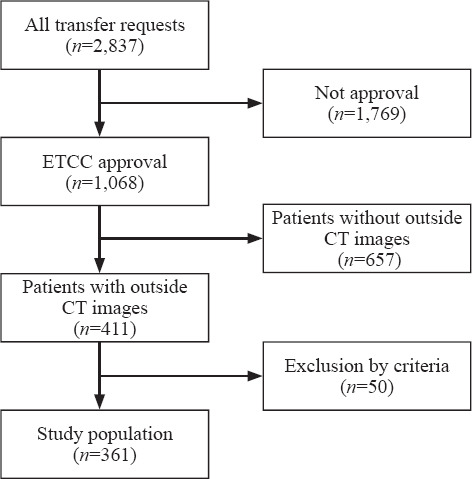

During the study period, 1,068 transfer requests out of a total of 2,837 were approved by the ETCC. There were 411 patients with outside CT images. Among them, 50 were excluded based on the exclusion criteria, resulting in the enrollment of 361 patients (Figure 1). A total of 107 (29.6%) cases were classified as discrepancies, among which 55 (15.24% of the total cases) were major discrepancies. Major discrepancies were present in 10 (11.36%) patients from high-level hospitals and 45 (16.48%) patients from low-level hospitals. Major discrepancies were found in 40 (23.95%) abdominal CT images and 3 (3.09%) brain CT images. The other baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Patient inclusion flowchart. ETCC: emergency transfer coordination center; CT: computed tomography.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics according to discrepancy, n (%)

In univariable analyses, the presence of trauma, CT subtype, and use of contrast were identified as factors affecting discrepancies of interpretation, while in the multivariable model, the CT subtype was the only independent risk factor. In the univariable analyses, the odds ratio of non-trauma for discrepancies was 2.308 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.118–3.714), and that of use of contrast was 2.101 (95% CI 1.249–3.535); these odds ratios changed to 1.643 (95% CI 0.727–3.715) and 0.957 (95% CI 0.501–1.829), respectively, in the multivariable logistic regression (Table 2). As part of the sensitivity analysis, we performed the multivariable logistic modeling of non-brain cases. In this analysis, no variable showed a significant effect on the discrepancy of CT image interpretation (supplementary file 1).

Table 2.

Odds ratios for the discrepancy of CT interpretation

Figure 2 shows how the discrepancy of interpretation influenced the time to disposition in the ED. The present study confirmed that the discrepancy of interpretation was significantly associated with the prolonged time to disposition in ED (P=0.005).

Figure 2.

Clinical effects of CT interpretation discrepancy.

DISCUSSION

Recently, due to the development of imaging technology, more patients are referred to high-level EDs after CT scans have been performed at primary medical institutions.[17] CT is a practical diagnostic tool, but is known to be affected by frequent interpretation discrepancies.[14] Accordingly, discrepancies in CT readings are of interest for many medical professionals. A previous study has shown that CT images are more consistent when the radiologist reads them, and that abdominal CT images can be read more accurately by radiologists.[15] Factors such as trauma image, age, and multiple CTs, which were assumed to be risk factors for discrepancies in CT image interpretation, were analyzed in previous studies. However, none of these studies were designed to target the discrepancy of interpretation of CT images performed on patients transferred between EDs, and were not performed using systematic methods.[7,11-14,17] In the present study, the interpretation of brain CT images was found to be relatively less inconsistent than that of other CT subtypes. The lower discrepancy rate of brain CT was in agreement with the results of a previous study.[13] It is believed that brain CT has lower discrepancy rates because the spectrum required to cover ED practice is narrow compared to other CT subtypes. Acute lesions, which can be detected using brain CT in EDs, do not have a broad spectrum of interpretation and do not involve various organs and anatomical structures like abdominal or chest CT scans. In our study, trauma and the absence of contrast medium were associated with low discrepancies. However, among the cases where brain CT was taken, the proportion of trauma and non-contrast cases was high. Therefore, contrast agents and trauma might have acted as confounders in the relationship between CT subtype and discrepancy.

The present study found that the time to disposition was prolonged in the discrepancy group. The disagreement in CT interpretation of transferred patients can cause the performance of additional CT in the clinical process, lengthening the patient’s ED LOS. Therefore, it may be helpful to evaluate the related risk factors during the transfer coordination process, so that CT image discrepancies can be predicted in advance. Based on the results of the present study, outside abdominal or chest CT images should be interpreted through a secondary reading system in the ED. Moreover, the results suggest the need of a system for immediate inter-hospital image transmission and interpretation by qualified radiologists before patient arrival. These efforts may also contribute to the rapid and accurate ED process of emergent transferred patients and alleviate ED crowding.

The present study has several strengths over previous studies of similar topics. It features a homogenous study population that was consecutively extracted thanks to a systematic emergency transfer system.[19] This allowed the standardized collection of known data to be associated with discrepancies of CT interpretation in patients transferred from various medical institutions, thus allowing the collection of variables that were difficult to identify in previous studies. In addition, our radiologic interpretation system allowed external images to be quickly moved to the internal PACS, allowing them to be interpreted more effectively,[2] the qualified radiologists being able to confirm discrepancies 24 hours/day in our ED. The results of the secondary interpretation were immediately reflected in the clinical process of the ED, which was an optimal place to achieve the study objectives.

This study has several limitations. First, although a prospectively collected registry was used, there was a possibility of bias due to the retrospective design of the study. In addition, it is difficult to generalize the study results because of its single-center nature. Finally, the clinical outcomes evaluated in our study did not include those related to patient safety, such as mortality or complications related to discrepancies. Therefore, additional studies to verify the association between inconsistencies in CT interpretation and patient outcome should be considered.

CONCLUSIONS

The CT subtype is the strongest risk factor for discrepancies of outside CT interpretation in patients urgently transferred to a high-level ED. Our study results can be used as practical evidence to prepare for secondary interpretation of CT images and clinical planning in EDs when there is a request for emergency transfer from other facilities.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: This study adhered to the STROBE statement and was approved by the institutional review board (approval number 44-2020-0458).

Conflicts of interests: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Contributors: HSL and JM contributed equally to this work. All authors approved the final version.

The supplementary file in this paper is available at http://wjem.com.cn/EN/10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2022.001.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yang S, Lee JM, Hoshino M, Murai T, Choi KH, Hwang D, et al. Prognostic implications of comprehensive whole vessel plaque quantification using coronary computed tomography angiography. JACC:Asia. 2021;1(1):37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jacasi.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sodickson A, Opraseuth J, Ledbetter S. Outside imaging in emergency department transfer patients:CD import reduces rates of subsequent imaging utilization. Radiology. 2011;260(2):408–13. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson JD, Linnau KF, Hippe DS, Sheehan KL, Gross JA. Accuracy of outside radiologists'reports of computed tomography exams of emergently transferred patients. Emerg Radiol. 2018;25(2):169–73. doi: 10.1007/s10140-017-1573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalilzadeh O, Rahimian M, Batchu V, Vadvala HV, Novelline RA, Choy G. Effectiveness of second-opinion radiology consultations to reassess the cervical spine CT scans:a study on trauma patients referred to a tertiary-care hospital. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2015;21(5):423–7. doi: 10.5152/dir.2015.15003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sung JC, Sodickson A, Ledbetter S. Outside CT imaging among emergency department transfer patients. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009;6(9):626–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abujudeh HH, Boland GW, Kaewlai R, Rabiner P, Halpern EF, Gazelle GS, et al. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) interpretation:discrepancy rates among experienced radiologists. Eur Radiol. 2010;20(8):1952–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1763-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eakins C, Ellis WD, Pruthi S, Johnson DP, Hernanz-Schulman M, Yu C, et al. Second opinion interpretations by specialty radiologists at a pediatric hospital:rate of disagreement and clinical implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(4):916–20. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turgut K, Yavuz E, Yıldız MK, Poyraz MK. Violence toward emergency physicians:A prospective-descriptive study. World J Emerg Med. 2021;12(2):111–6. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2021.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun BC, Adams J, Orav EJ, Rucker DW, Brennan TA, Burstin HR. Determinants of patient satisfaction and willingness to return with emergency care. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(5):426–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thornburg DA, Paulson WE, Thompson PA, Bjordahl PM. Pretransfer CT scans are frequently performed, but rarely helpful in rural trauma systems. Am J Surg. 2017;214(6):1061–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Issa G, Taslakian B, Itani M, Hitti E, Batley N, Saliba M, et al. The discrepancy rate between preliminary and official reports of emergency radiology studies:a performance indicator and quality improvement method. Acta Radiol. 2015;56(5):598–604. doi: 10.1177/0284185114532922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes JF, Siglock BG, Corwin MT, Johnson MA, Salcedo ES, Espinoza GS, et al. Rate and reasons for repeat CT scanning in transferred trauma patients. Am Surg. 2017;83(5):465–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomich J, Retrouvey M, Shaves S. Emergency imaging discrepancy rates at a level 1 trauma center:identifying the most common on-call resident “misses”. Emerg Radiol. 2013;20(6):499–505. doi: 10.1007/s10140-013-1146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu MZ, McInnes MD, Macdonald DB, Kielar AZ, Duigenan S. CT in adults:systematic review and meta-analysis of interpretation discrepancy rates. Radiology. 2014;270(3):717–35. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13131114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindgren EA, Patel MD, Wu Q, Melikian J, Hara AK. The clinical impact of subspecialized radiologist reinterpretation of abdominal imaging studies, with analysis of the types and relative frequency of interpretation discrepancies. Abdom Imaging. 2014;39(5):1119–26. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0140-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howlett DC, Drinkwater K, Frost C, Higginson A, Ball C, Maskell G. The accuracy of interpretation of emergency abdominal CT in adult patients who present with non-traumatic abdominal pain:results of a UK national audit. Clin Radiol. 2017;72(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guérin G, Jamali S, Soto CA, Guilbert F, Raymond J. Interobserver agreement in the interpretation of outpatient head CT scans in an academic neuroradiology practice. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(1):24–9. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahn KO, Shin SD, Hwang SS, Oh J, Kawachi I, Kim YT, et al. Association between deprivation status at community level and outcomes from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest:a nationwide observational study. Resuscitation. 2011;82(3):270–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim EN, Kim MJ, You JS, Shin HJ, Park IC, Chung SP, et al. Effects of an emergency transfer coordination center on secondary overtriage in an emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(3):395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho A, Kim MJ, You JS, Shin HJ, Lee EJ, Park I, et al. Postcontrast acute kidney injury after computed tomography pulmonary angiography for acute pulmonary embolism. J Emerg Med. 2019;57(6):798–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]