Abstract

The molecular mechanisms regulating monocyte differentiation to macrophages remain unknown. Although the transcription factor NF-κB participates in multiple cell functions, its role in cell differentiation is ill defined. Since differentiated macrophages, in contrast to cycling monocytes, contain significant levels of NF-κB in the nuclei, we questioned whether this transcription factor is involved in macrophage differentiation. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-induced differentiation of the promonocytic cell line U937 leads to persistent NF-κB nuclear translocation. We demonstrate here that an increased and persistent IKK activity correlates with monocyte differentiation leading to persistent NF-κB activation secondary to increased IκBα degradation via the IκB signal response domain (SRD). Promonocytic cells stably overexpressing an IκBα transgene containing SRD mutations fail to activate NF-κB and subsequently fail to survive the PMA-induced macrophage differentiation program. The differentiation-induced apoptosis was found to be dependent on tumor necrosis factor alpha. The protective effect of NF-κB is mediated through p21WAF1/Cip1, since this protein was found to be regulated in an NF-κB-dependent manner and to confer survival features during macrophage differentiation. Therefore, NF-κB plays a key role in cell differentiation by conferring cell survival that in the case of macrophages is mediated through p21WAF1/Cip1.

The molecular mechanisms regulating cell differentiation involve a fine and complex balance of proteins and signal transduction pathways that modulate the progression through the cell cycle and control of cell survival (11, 48). Human macrophages are differentiated noncycling cells arrested at the G1 checkpoint that derive from peripheral blood cycling human monocytes. These cells are present in multiple body tissues and play a key role in various immune functions and thus are relevant to a number of human diseases (26, 45). Unlike the well-characterized process of B-lymphocyte differentiation, little is known regarding the molecular mechanisms governing the monocyte differentiation to macrophage, Promonocytic human cell lines, like human primary monocytes, can be triggered to differentiate to human macrophages by defined stimuli (45). Agents such as phorbol esters (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate [PMA]) induce their exit from the cell cycle at G1, leading to their differentiation, which is characterized by the appearance of macrophage-like features such as cell surface integrins, adherence to plastic, and the production of reactive oxygen intermediates (4, 8, 21).

A number of transcription factors such as PU.1 have been implicated in monocyte differentiation, as have other proteins, including p21WAF1/Cip1 (21, 32, 43, 44, 48, 60). p21WAF1/Cip1 is a nuclear protein of the family of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors (17) which functions to inhibit CDK1, -2, -4, and -6 (9) and, hence, its induction by a number of stimuli causes cell cycle arrest at the G1/S boundary (8, 20, 37, 51, 57), allowing the cell to exit the cell cycle and differentiate. Interestingly in differentiated human macrophages, p21WAF1/Cip1 is predominantly located in the cytosol where it exerts an antiapoptotic function by means of inhibiting the proapoptotic kinase Ask1 (1). Whether the critical role that p21WAF1/Cip1 plays in macrophage differentiation is dependent on its ability to inhibit the cell cycle or protect the cell from death while it is undergoing differentiation is unclear.

Members of the NF-κB/Rel family of transcription factors are key regulators of a variety of genes involved in cell growth and survival (3, 4, 6). NF-κB is generally found as an inactive dimer sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitor proteins termed IκB. However, in a few exceptions, such as terminally differentiated B lymphocytes and plasma cells, as well as human macrophages, NF-κB is constitutively present at very high levels in the nuclei of these cells (7, 35, 40). At least two potential mechanisms involving IκB regulation can result in the nuclear translocation of NF-κB. Acute stimuli such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) lead to the rapid proteolysis of IκB molecules via a common, terminal transduction pathway leading to the rapid phosphorylation of IκB by two highly related serine kinases, IKK1 and IKK2. These kinases phosphorylate IκB on critical serine residues, such as Ser32 and Ser36, within the N-terminal signal response domain (SRD) of IκBα (31, 61). In addition, IκB molecules have a C-terminal PEST domain, which is a highly negative charged region conferring protein instability and hence favoring a slow but continuous level of IκB degradation (55, 56). Cycling primary human monocytes have no NF-κB in their nuclei. However, their differentiation to macrophages triggered by plastic adherence or phorbol esters leads to a progressive and significant degree of NF-κB nuclear translocation, a hallmark of differentiated macrophages. The molecular mechanisms regulating NF-κB translocation to the nucleus during macrophage differentiation and the role NF-κB plays in the relevant cellular processes is unknown (24, 25, 34, 53).

The distinct changes in the cellular localization observed for p21WAF1/Cip1 and NF-κB during macrophage differentiation and their potential influence in cell survival and cell cycle control raise the possibility that these key proteins may regulate each other, leading to a coordinated process of differentiation. Likewise, previous observations in a number of systems suggest that NF-κB may regulate p21WAF1Cip1 expression (5, 29, 49). The recent availability of genetic tools to inhibit the expression or function of such proteins has enabled us to address their role in macrophage differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, cell culture, and induction of differentiation.

The human promonocytic cell line U937 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and grown in RPMI 1640 (BioWhitaker) plus 5% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Intergen), penicillin and streptomycin (100 U/ml; Gibco-BRL), and glutamine (0.3 mg/ml; Gibco-BRL). U937 clones expressing FLAG-IκBα transgenes were previously described (2). Results shown herein were similar for each of three separate clones. U937 cells stably expressing either empty vector (pREP4) or p21(AS) constructs (F4 and B8) were previously described (60) and were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin-streptomycin, glutamine, minimal essential medium (MEM) nonessential amino acids (0.1 mM; Gibco-BRL), MEM sodium pyruvate (1 mM; Gibco-BRL), and 200 μg of hygromycin B (Sigma) per ml. All cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/ml and induced to differentiate with PMA (2 ng/ml; Sigma) or treated with vehicle control (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]). TNF (10 ng/ml; Genzyme) was used at the indicated times as a positive control for IκBα degradation and subsequent NF-κB activation.

For the inhibition of differentiation-induced apoptosis, cells were seeded as described above and induced to differentiate with PMA. At time of culture initiation, TNF receptor (TNFR)-Fc (5.5 ng/ml; Immunex Corp., Seattle, Wash.) was added. An equivalent quantity of IL-4 receptor (IL4R)-Fc was added to parallel cultures as a control.

Evaluation of differentiation and survival.

Cells were seeded and induced to differentiate with PMA as described above. At the indicated time points, cells were evaluated for differentiation markers. Cells were examined microscopically for differentiation morphology such as increased cell volume, granularity, and the appearance of irregularly shaped cellular processes. Adherence was determined by gently rocking the plates and by collecting nonadherent cells in the culture supernatant. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added back to the culture flasks, and adherent cells were lifted by gentle scraping. Viable cells were scored by trypan blue exclusion. Surface expression of CD11c was determined by staining with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated CD11c antibody (BioSource) detected by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) and analyzed with CellQuest Software (Becton Dickinson). The cell cycle profile was determined by propidium iodide (PI) staining. In brief, cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS and resuspended in approximately 100 μl of PBS. Cells were fixed and permeabilized with ice-cold 70% ethanol at least overnight. Fixed cells were pelleted by cold centrifugation and resuspended in sample buffer containing 50 μg of PI and 100 Kunitz U of RNase A per ml. Cells were analyzed by FACS and CellQuest Software. The sub-G0 population was scored as apoptotic.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic extract preparation, immunoprecipitations, and in vitro kinase assays.

Nuclear and cytosolic extracts were prepared by a modification of the method of Dignam et al. (14). Briefly, cells were washed twice in buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl). Cells were lysed two times for 5 min on ice in buffer A containing 0.1% NP-40; 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT); 0.5 mM phenylmethlysulfonyl fluoride (PMSF); 2 μg each of aprotonin, leupeptin, and pepstatin per ml; and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. After centrifugation, the cells were washed twice in buffer A, and the nuclei were collected by centrifugation. Pelleted nuclei were lysed in 10 to 15 μl of buffer C (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 25% glycerol, 0.42 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], DTT, PMSF, aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin, and sodium orthovanadate) by rotation at 4°C for 30 min. After centrifugation, the supernatants were diluted in 2× volumes of buffer D (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 20% glycerol, 50 mM KCl, 0.2 M EDTA, DTT, PMSF, aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin, and sodium orthovanadate).

For immunoprecipitations, cells were washed twice in 50 mM Tris-HC (pH 7.5) and 150 mM NaCl and then lysed for 5 min on ice in wash buffer plus 0.1% Trition X-100; 2 μg each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin per ml; and 0.5 mM PMSF. Following clarification by centrifugation, cytoplasmic extracts (50 μg) were rotated at 4°C for 1 to 2 h in the presence of antibodies to the N and C termini of RelA (Santa Cruz) and 10 μl of protein A-conjugated agarose beads (Gibco-BRL). Precipitates were washed three times with lysis buffer and eluted with 2× Laemmli sample buffer at 95°C. Subsequent immunoprecipitations on supernatants demonstrated complete precipitation of all RelA. Eluted proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore).

For in vitro kinase assays, whole-cell extracts were prepared by washing the cells twice in ice-cold PBS, followed by lysis for 5 min on ice with 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.3 M NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 6 mM EDTA, 6 mM EGTA, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate (P-NPP), 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.3 mM sodium orthovanadate, DTT, PMSF, aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation. Then, 100 μg of total cell extract was used in subsequent kinase assays. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibody to the IKK complex (IKKα or MKP1; Santa Cruz) for 1 h, after which protein A-agarose was added for 1 h. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, followed by one wash with buffer A. Beads were incubated in 15 μl of kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4]; 2 mM MgCl2; 2 mM MnCl; 10 mM ATP; 10 mM NaF; 10 mM P-NPP; 10 mM β-glycerophosphate; 0.3 mM sodium orthovanadate; PMSF; 2 μg each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin per ml; 1 mM DTT) with 2 μg of glutathione S-transferase (GST)–IκBα1–53 and 0.1 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP. The kinase reaction was carried out for 30 min at 30°C, and samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE.

EMSA, Northern, and Western analyses.

For electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs), 4 μg of nuclear extract was incubated with a [γ-32P]ATP-labeled double-stranded probe as previously described (2). Components of the probe binding complex were identified by preincubation of the extract with antibodies to specific components of NF-κB (Santa Cruz) prior to probe exposure. DNA-protein complexes were resolved on a 6% polyacrylamide gel, dried, and visualized by autoradiography. Western blotting was performed as recommended by the ECL Kit (Amersham) package insert. Antibodies to p21WAF1/Cip1 (Transduction Laboratories), IκBα (Santa Cruz), FLAG (Sigma), β-actin (Sigma), and IKKα and IKKβ (Santa Cruz) were used. Where indicated, the intensities of the bands were quantified by densitometry and analyzed by using the Ambis software package. For Northern analysis, cells were treated with either DMSO, PMA, or TNF for 6 h. Total RNA was isolated by RNAzol B (TelTest) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was resolved on an agarose-formamide gel and transferred to a HyBond-N+ membrane (Amersham) p21WAF1/Cip1 cDNA, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probes were prepared by using the Random Primed DNA Labeling Kit (Roche) as described in the package insert and then hybridized to membrane in RapidHyb Buffer (Amersham) and washed in sequentially more stringent SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) washes. Results were visualized by autoradiographyand quantified by densitometry using the Ambis software package.

Adenoviral transduction.

Peripheral blood lymphocytes were obtained from buffy coats using a Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient. Mononuclear cells were washed extensively and incubated with neuraminadase-treated sheep red blood cells to rosette T cells. CD14+ monocytes were then isolated from the resulting mononulear cell population by negative depletion using the StemSep (StemCell) system according to the manufacturer's instructions. Enriched CD14+ cells were typically found to be 80 to 86% pure by FACS analysis. An aliquot of cells was lysed with whole-cell lysis buffer as above. CD14+ cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum. Cells were allowed to plastic adhere for 30 h, and then washed gently with fresh media. Cells were fed with one-half conditioned medium plus fresh AB media. Five days after isolation, The cells were washed to remove nonadherent cells and transduced with adenovirus (100 PFU/cell) expressing HA-IκBα Ser 32/36 Ala or alkaline phosphatase. The transduction efficiency was monitored by nitroblue tetrazolium-BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate) staining (Roche) and typically was 90 to 95% efficient. Two days after harvest, cells were lysed in whole-cell lysis buffer as described above.

RESULTS

Persistent activation of NF-κB correlates with cell differentiation and is dependent on the IKK complex kinase activity.

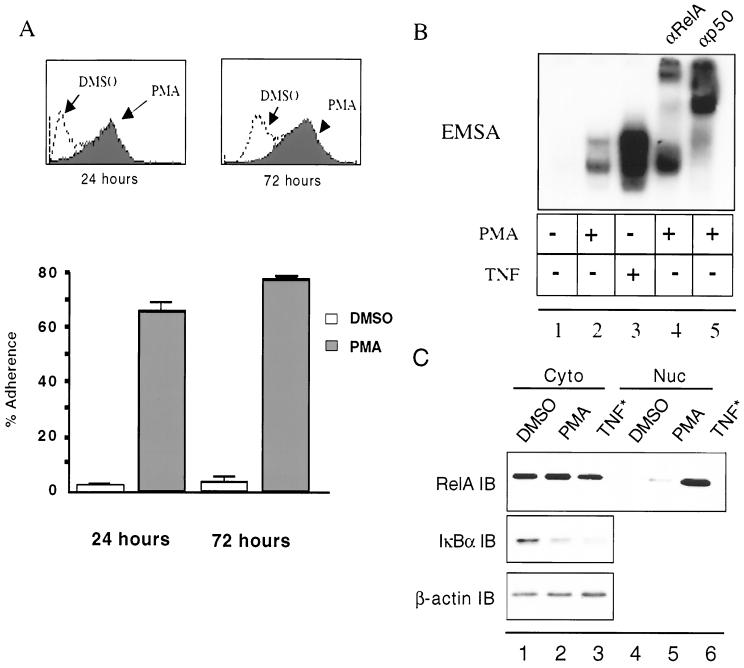

To address the role of NF-κB on monocyte differentiation, we first sought to characterize a model of monocyte differentiation in which NF-κB activation is observed in the context of differentiation (24, 25) and which is amenable to genetic inhibition following identification of the mechanism regulating NF-κB nuclear translocation. Using the human promonocytic U937 cell line, it is demonstrated that these cells become adherent to plastic and express CD11c integrin, a cell surface marker of differentiated macrophages, by 24 h following exposure to low-dose (2 ng/ml) PMA (Fig. 1A). As has been previously reported (24, 25), the differentiation program initiated by PMA correlates with the progressive nuclear localization of NF-κB by 24 h posttreatment (compare lanes 1 and 2 in Fig. 1B with lanes 4 and 5 in Fig. 1C). EMSA analysis demonstrates that the nuclear complex of NF-κB is composed mainly of RelA-p50 dimers (Fig. 1B, lanes 4 and 5). EMSA analysis shows that c-Rel or RelB antibodies fail to appreciably shift either NF-κB activity, while the lower activity can be completely shifted with p50 antibodies (data not shown). Nuclear localization of NF-κB correlates with a marked reduction in IκBα steady-state protein levels (Fig. 1C), as well as of IκBβ and p105 (data not shown). Therefore, PMA-induced differentiation of the U937 promonocytic cell line to a macrophage phenotype is accompanied by a progressive and persistent nuclear translocation of NF-κB resulting from constitutively decreased IκB protein.

FIG. 1.

U937 promonocytic cells differentiate into a macrophage-like phenotype following exposure to phorbol esters. (A) U937 cells grown in suspension become adherent following exposure to PMA (2 ng/ml) by 24 h with persistence of the phenotype for up to 3 days after the first appearance the PMA differentiation signal. FACS profiles of CD11c expression following treatment with PMA or DMSO vehicle are inset. (B) Differentiation leads to the nuclear translocation of prototypic NF-κB heterodimers at 24 h post-PMA exposure. c-Rel and RelB antibodies had minimal effect on the mobilities of either NF-κB complex (data not shown). TNF-α treatment lasted 8 min and served as a positive control. (C) IκBα steady-state levels are markedly reduced at 24 h posttreatment with PMA and correlate with the presence of nuclear RelA. TNF-α treatment was for 8 min and served as a positive control.

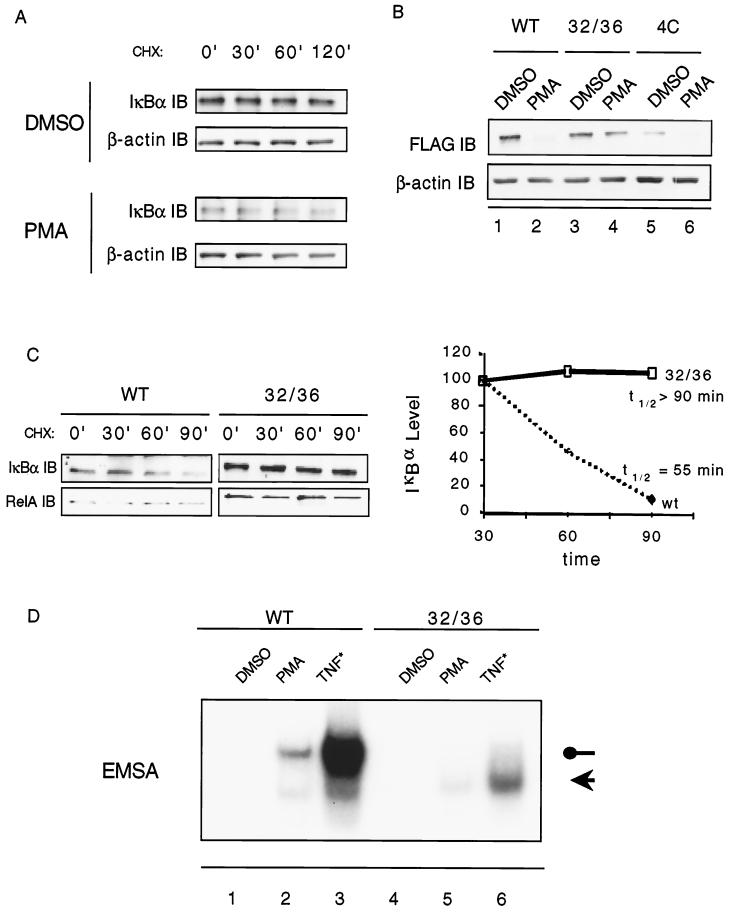

The decreased steady-state protein level of IκBα observed in PMA-differentiated U937 cells is secondary to a decrease in the protein's half-life (Fig. 2A). The decrease in IκBα protein half-life could potentially arise from activation signals targeting the SRD. Alternately, the C-terminus PEST domain, previously shown to confer instability to a host of proteins, could be targeted during differentiation in order to further decrease the IκBα half-life. Using U937 cells stably expressing either a wild-type FLAG-tagged IκBα (WT) or FLAG-tagged IκBα in which either the SRD or the C-terminal PEST domain are mutated (32/36 or 4C, respectively), we observed that PMA-induced cell differentiation targets the SRD but not the PEST domain of IκBα, as demonstrated by a decrease in the steady-state protein levels of FLAG-IκBα WT and FLAG-IκBα 4C (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 1 to 2 and lanes 5 to 6) but not of FLAG-IκBα 32/36 (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4). The functional relevance of this observation is demonstrated by the fact that RelA-associated IκB is targeted by the PMA-induced differentiation process (Fig. 2C) and by the lack of nuclear translocation of NF-κB in PMA-stimulated FLAG-tagged 32/36 IκBα cells (Fig. 2D, compare lanes 2 and 5).

FIG. 2.

IκBα in differentiated U937 cells has a shorter half-life than in undifferentiated cells, and the half-life is dependent upon the SRD. (A) U937 cells differentiated by exposure to PMA (2 ng/ml) for 24 h were lysed at different points following treatment with cycloheximide and analyzed for IκBα levels by Western blot. β-Actin was probed as a gel loading control. (B) To determine which region of IκBα mediates reduced IκBα steady-state levels, U937 clones stably expressing FLAG-tagged IκBα transgenes were induced to differentiate by PMA (2 ng/ml) and lysed at 6 h into the differentiation program. WT, FLAG-IκBα; 32/36, FLAG-IκBα 32/36Ser-to-Ala; 4C, FLAG-IκBα 283/288/293/291Ser/Thr-to-Ala. IκBα levels were determined by Western blot. Similar results were seen at 12 and 24 h postdifferentiation (data not shown). (C) In order to address the direct role of IκBα in cytosolic retention of NF-κB, clones expressing either the FLAG-tagged WT IκBα or FLAG-IκBα 32/36 were differentiated for 24 h and then treated with cycloheximide (50 μg/ml). Treated cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-RelA. Immunoprecipitates were then analyzed for RelA-associated IκBα levels by Western blot. Gels were analyzed by densitometry, and the half-life was plotted as a function of IκBα levels over time. (D) Gel shift analysis demonstrates that mutation of the SRD of IκBα abrogates differentiation-induced activation of NF-κB by PMA. WT or 32/36 cells were treated with PMA for 24 h. TNF treatment was for 4 h and serves as a control. The identity of the upper band (filled circle) was confirmed by supershift analysis as RelA/p50. The lower band (arrow) was confirmed as p50 homodimers (data not shown). The results are representative of three independent clones.

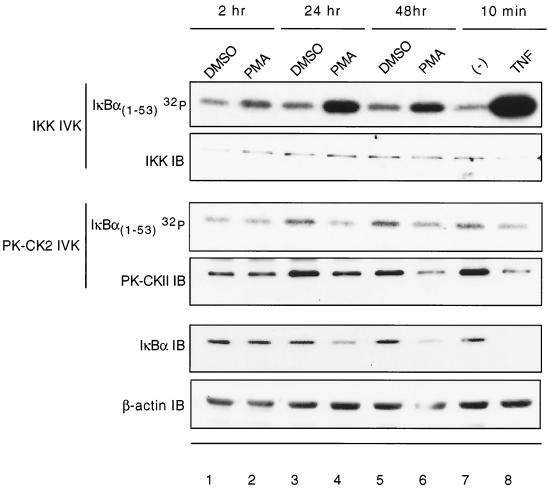

The SRD of IκBα is targeted by a number of kinases, including the IKK complex, pp90rsk, and PK-CK2 (23, 31, 52). While IKK is well characterized to mediate IκBα phosphorylation by punctual and rapid stimuli such as TNF or IL-1, we questioned whether it could also be involved in targeting the IκBα SRD as a result of monocyte differentiation. The kinase activity of the IKK complex was analyzed at different time points along the cell differentiation program. As seen in Fig. 3, an increase in IKK activity toward the SRD of the IκBα substrate is detected as early as 2 h following PMA, with further increases at 24 and 48 h. The persistent and heightened IKK activity further correlates with reduced steady-state levels of IκBα (Fig. 3, compare panels 1 and 5). In contrast, the kinase activity of PK-CK2, previously shown to directly phosphorylate the PEST (39) and SRD domain of IκBα (52), is not observed during the same time points. Therefore, the persistent decrease in IκBα levels observed during monocyte differentiation correlates with persistent and increased activity of the IKK complex. This is notable in demonstrating that the IKK complex is not only punctually activated by defined inflammatory stimuli such as TNF or IL-1 but also in a persistent manner by processes such as cell differentiation.

FIG. 3.

IKK activity is increased in differentiated U937 cells. The differentiation program of U937 cells was initiated by treatment with PMA (2 ng/ml). Cells were collected and lysed at 2, 24, or 48 h after PMA treatment. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibody to either PK-CK2 or the IKK complex. The resulting immunocomplex was used to radiolabel GST-IκBα1–53 in an immunokinase assay. IKKβ or PK-CK2 levels were detected by immunoblotting to ensure that there were equal levels of kinase in each sample. Membrane was Coomassie blue stained to ensure the presence of equal amounts of substrate in each reaction (data not shown). IκBα levels at the indicated time points were detected by Western blot. β-Actin was probed as a gel loading control. TNF-α treatment was for 8 min and served as a positive control.

Activation of NF-κB is necessary for surviving the monocyte differentiation program.

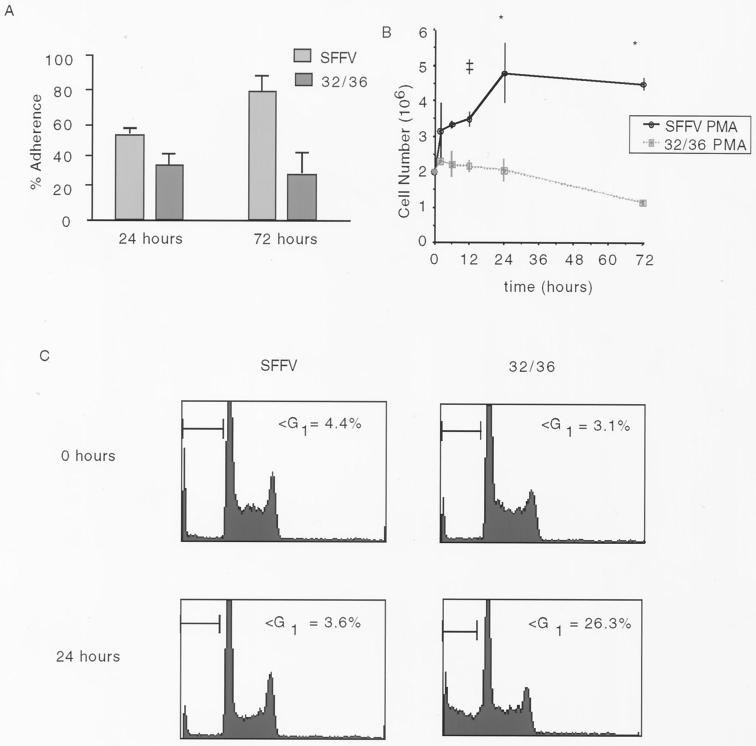

Although it is well established that NF-κB is activated during monocyte differentiation, little is known about the functional relevance of this activation. Identification of the IKK complex and the SRD domain of IκBα as targets of signaling pathways triggered by PMA-induced monocyte differentiation enables us to test the role of NF-κB in this process by inhibiting its activation using genetic approaches. U937 clones stably expressing FLAG-tagged IκBα containing mutations of the key SRD serines (32/36) or empty vector (SFFV) were treated with PMA and evaluated thereafter for differentiation markers as in Fig. 1. As early as 24 h and as late as 72 h post-PMA treatment, a marked reduction in the number of U937 cells expressing the SRD IκBα mutant (32/36) which become plastic adherent is observed. Following the initiation of the differentiation program, both SFFV and 32/36 cells can complete at least one turn of the cell cycle, as evidenced by the cell cycle profile in Fig. 4C and the increase in cell numbers for SFFV cells (Fig. 4B). However, there is a marked decrease in viable 32/36 cells following PMA-induced monocyte differentiation compared to SFFV control cells (Fig. 4B). That the decreased cell survival observed in the PMA-treated 32/36 U937 cells is apoptotic in nature is demonstrated by the increase of subdiploid DNA in the PI cell cycle profile shown in Fig. 4C. From these data it is inferred that the persistent nuclear translocation of NF-κB confers a protection to promonocytic cells undergoing the differentiation process.

FIG. 4.

Activation of NF-κB is necessary for surviving the differentiation program in U937 cells. (A) U937 cells induced to differentiate with PMA (2 ng/ml) were scored for adherence at 24 or 72 h post-PMA treatment, and values are expressed as in Fig. 1. (B) Vector control (SFFV) or cells stably expressing an SRD mutant IκBα (32/36) were treated with either PMA or DMSO and harvested at 2, 6, 12, 24, or 72 h posttreatment. Only viable cells were scored. No differences were seen in vehicle control SFFV or 32/36 cells. Only PMA-treated points are shown (∗, P < 0.05; ‡ P < 0.10; Student's t test). (C) SFFV and 32/36 cells treated for 0, 24, or 72 h with PMA were collected, fixed, and DNA stained with PI. The Cell cycle distribution is shown. The apoptotic population was scored as the sub-G1 DNA fraction by FACS analysis.

Differentiation-induced cell death of monocytes is triggered by TNF.

The novel observation that NF-κB is necessary to survive the differentiation process led us to examine what NF-κB opposed factors may be initiating differentiation-induced apoptosis. It is well established that NF-κB protects a number of cells from TNF-induced apoptosis (3, 6, 53, 59). In addition, several studies have shown that TNF is involved in a number of hematopoeitic cell differentiation models (16, 18, 38, 62). We asked, therefore, whether endogenous production of TNF is mediating the apoptosis seen during differentiation. U937 clones stably expressing mutant FLAG-tagged IκBα (32/36) or empty vector (SFFV) were treated with PMA and evaluated for apoptosis using PI staining as described above. Selected wells were also treated with a TNFR-Fc protein to block binding of endogenous TNF to native TNF receptors. IL4R-Fc was used as a control. As seen in Fig. 5, a relatively low dose of TNFR-Fc blocked nearly half of the differentiation-induced cell death in 32/36 U937 cells, while the IL4R-Fc fusion protein had no effect. From these data, it can be inferred that endogenously produced TNF by differentiating monocytes triggers apoptosis. Whether this TNF elicited during differentiation (following PMA treatment) itself is a differentiation signal is unknown.

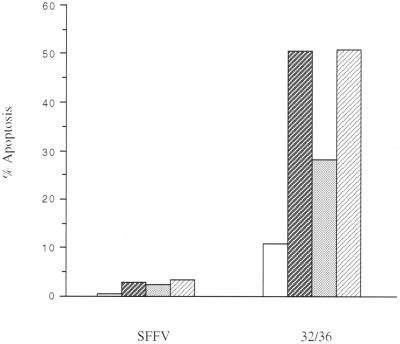

FIG. 5.

TNF-α-mediated differentiation-induced apoptosis. U937 cells stably transfected with either empty vector (SFFV) or the IκBα SRD mutant (32/36) were induced to differentiate with PMA (2 ng/ml) for 24 h. DMSO served as a vehicle control. At the initiation of differentiation, cells were treated with TNFR-Fc or IL4R-Fc. Apoptotic cells were scored by FACS analysis as the sub-G1, DNA fraction following PI staining as in Fig. 4. columns: □, DMSO;  , PMA;

, PMA;  , PMA plus TNFR-Fc;

, PMA plus TNFR-Fc;  , PMA plus IL4r–Fc.

, PMA plus IL4r–Fc.

NF-κB regulates p21WAF1/Cip1 expression which is required for monocyte survival during the differentiation process.

The antiapoptotic characteristics of NF-κB are presumed to be mediated by a number of known and yet-to-be-identified survival genes (3, 10, 12, 19). Several studies have previously reported a link between NF-κB activation and p21 expression in a number of cell systems (see the introduction). Because of the p21WAF1/Cip1 upregulation observed during monocyte differentiation and the ability of this protein to confer resistance to apoptosis in cells of monocytic origin (1, 9, 29, 60), we hypothesized that the requirement of NF-κB to protect the cell from death during monocyte differentiation may be through the upregulation of p21WAF1/Cip1. To test this, we first analyzed whether there exists a direct correlation between levels of p21WAF1/Cip1 and nuclear translocation of NF-κB during the process of macrophage differentiation. PMA-induced differentiation of SFFV vector control U937 cells correlated with the upregulation of cytosolic p21WAF1/Cip1 in the absence of cell death. By contrast, PMA treatment of 32/36 U937 cells did not result in the upregulation of p21WAF1/Cip1 expression and, as expected, resulted in cell death in the absence of NF-κB activation (Fig. 6A and B). Northern analysis of mRNA from SFFV vector control and 32/36 U937 cells verifies the role of NF-κB in regulating p21WAF1/Cip1 transcription. Interestingly, TNF is unable to induce p21WAF1/Cip1 expression, despite being a potent inducer of NF-κB activity, in direct contrast to observations in Ewing sarcoma cells (29). Therefore, the inability of 32/36 U937 cells to survive the differentiation program may be due to their inability to induce expression of p21WAF1/Cip1, which we infer is an NF-κB-dependent process. To formally address this issue, we utilized U937 cells stably expressing or not antisense constructs for p21WAF1/Cip1. While PMA-induced differentiation of p21(AS) and control U937 cells induces NF-κB nuclear translocation in both cells types, p21WAF1/Cip1 expression is, as expected, not observed in the p21(AS) U937 cells, indicating that NF-κB is upstream of p21WAF1/Cip1. Moreover, the fact that p21(AS) U937 cells die following PMA-induced cell differentiation despite the induction of NF-κB nuclear translocation (Fig. 7), supports the role of p21WAF1/Cip1 as an NF-κB-dependent survival gene required for macrophage differentiation.

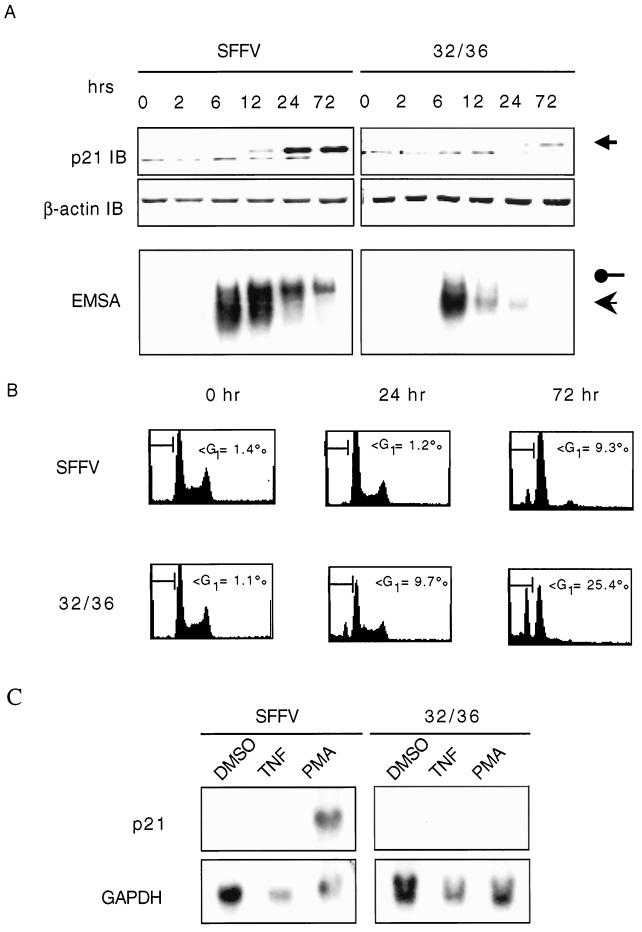

FIG. 6.

Activation of NF-κB is necessary for expression of p21WAF1/Cip1. (A) U937 cells induced to differentiate were lysed at the indicated times after PMA treatment, and cytosolic and nuclear extracts were collected. Cytosols were probed for p21WAF1/Cip1 expression by Western blot (small arrow). β-Actin was blotted as a loading control. Similar results were seen with whole-cell extracts (data not shown). Nuclear NF-κB activity was detected by EMSA, and the identity of the NF-κB components was confirmed by supershift assay as for Fig. 1 (data not shown). RelA-p50 and p50-p50 complexes are indicated by filled circles and arrows, respectively. (B) Vector control (SFFV) or cells stably expressing an SRD mutant IκBα (32/36) were treated with PMA and harvested at various times posttreatment. The cell cycle distribution is shown. The apoptotic cells were scored by FACS analysis as the sub-G1 DNA fraction following fixation and PI staining as for Fig. 4. (C) U937 cells stably transfected with either empty vector (SFFV) or the IκBα SRD mutant (32/36) were treated with PMA (2 ng/ml) or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 6 h, and the total RNA was harvested. p21WAF1/Cip1 mRNA levels was determined by Northern analysis, as were the GADPH levels as a loading control. p21WAF1/Cip1 mRNA levels were enhanced only following PMA treatment despite the activation of NF-κB with both TNF-α and PMA treatments (data not shown).

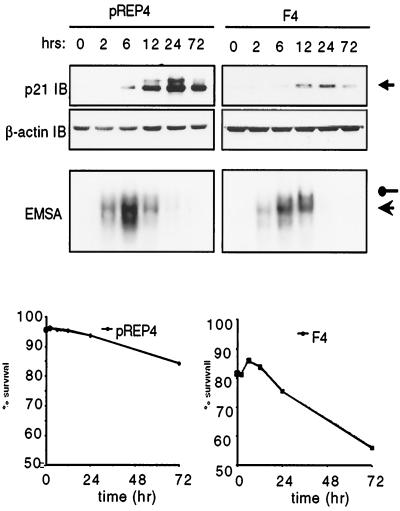

FIG. 7.

Ablation of p21WAF1/Cip1 expression results in failure to survive the differentiation program, even in the presence of NF-κB activation. U937 cells stably transfected with either empty vector (pREP4) or an antisense p21WAF1/Cip1 construct (F4) were treated with 2 ng of PMA per ml to initiate the differentiation program. pREP4 or F4 cells were collected at the indicated time points post-PMA treatment, and nuclear and cytosolic fractions were collected as for Fig. 6. F4 cells demonstrate a marked reduction in p21WAF1/Cip1 expression. β-Actin detection was included as a control for loading. EMSA analysis reveals roughly equivalent levels of nuclear NF-κB dimers. RelA-p50 and p50-p50 complexes are indicated by filled circles and arrows, respectively. Viable cells were detected by PI staining as for Fig. 5 and are expressed as the percent survival over time. A representative experiment is shown. Similar results were obtained with a second p21(AS) clone.

Inhibition of NF-κB reduces p21WAF1/Cip1 expression in primary macrophages.

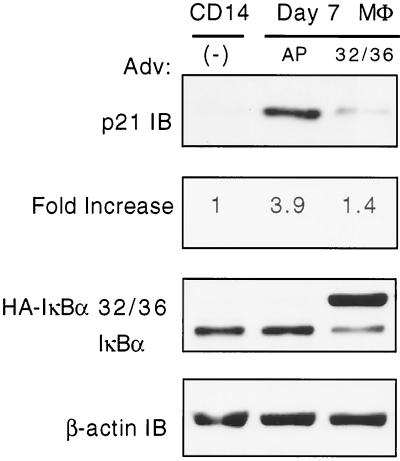

To investigate whether the NF-κB-dependent upregulation of p21WAF1/Cip1 in monocytic cells undergoing macrophage differentiation is also present in primary human cells, we optimized an adenovirus transduction model through which NF-κB could be inhibited by genetic approaches during the process of differentiation form monocytes to macrophages. Highly purified primary CD14+ peripheral human blood monocytes were isolated by negative selection and separated into two aliquots, one of which was lysed. The remaining cells were allowed to differentiate in tissue culture to macrophages for 5 days. At this time point adherent macrophages were transduced with adenovirus expressing either alkaline phosphatase (control) or HA-IκBα 32/36A. After 48 h the cells were harvested, lysed, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE in parallel with lysates obtained upon initial monocyte isolation for p21WAF1/Cip1 levels. As shown in Fig. 8, a small amount of p21WAF1/Cip1 is present in freshly isolated monocytes compared to that observed following their differentiation to macrophages. More importantly, transduction and expression of HA-IκBα 32/36A but not of alkaline phosphatase reduces the level of p21WAF1/Cip1 in differentiated macrophages, once more supporting the regulatory role of NF-κB on p21WAF1/Cip1 during macrophage differentiation.

FIG. 8.

NF-κB activation is necessary for p21WAF1/Cip1 expression in differentiated human monocytes. CD14+ cells were isolated from the buffy coat by negative depletion. FACS analysis indicated 84% enrichment. Cells were either lysed immediately after isolation or differentiated by plastic adherence. At day 5 postadherence, cells were transduced with adenovirus (Adv) expressing either HA-IκBα 32/36 (32/36) or alkaline phosphatase (AP). Cells were lysed 48 h posttransduction and analyzed for p21WAF1/Cip1 by immunoblotting. IκBα levels are included to show the relative expression of endogenous versus transduced protein. β-Actin was included as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides a number of novel observations pertaining to the regulation and functional role of NF-κB in cell differentiation. First, we have documented that the persistent activation of NF-κB that ensues following the initiation of monocyte differentiation is dependent on the continuous activation of the IKK complex and hence The phosphorylation and/or degradation of IκB molecules. Second, we have demonstrated the necessary role of NF-κB in allowing the cell to survive the differentiation process. Finally, we have shown that p21WAF1/Cip1 is indeed regulated by IKK-dependent NF-κB activation of p21WAF1/Cip1 in differentiating monocytes and may be the effector protein required to protect the cell from differentiation-induced cell death.

Several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that persistent NF-κB activation in a defined cell in the absence of punctual stimuli is in part due to a continued degradation of IκB molecules (35, 55). B cells at different stages of differentiation exhibit a structured sequence of NF-κB activation as they progress through the various steps of B-cell differentiation, ultimately leading to mature B cells and plasma cells which contain significant levels of NF-κB in the nucleus in a constitutive manner (3, 22). Our results suggest a key role for the IKK complex in mediating this continuous level of NF-κB translocation. Therefore, the IKK complex can be in a continuous state of activation, separate from the well-characterized punctual inducibility and rapid regression of activity seen with activators such as TNF or IL-1. In addition to the process of cell differentiation, pathological conditions such as cell transformation are also associated with a continuous and persistent level of NF-κB in the nucleus (12, 19, 36, 41). Whether the IKK complex is persistently activated in cells undergoing transformation such as shown in this study is unknown and deserves to be addressed in future studies since the persistent levels of NF-κB in the nuclei of cancer cells impact the response to chemotherapeutic and ionizing agents.

It should be noted that it is unlikely in this model that PMA itself acts directly upon signal transduction pathways converging on the IKK complex. First, in contrast to the case of TNF, IKK activity is not upregulated immediately following the treatment of monocytic cells with relatively low doses (2 ng/ml) of PMA. Second, IKK activation, as well as differentiation, is seen within 24 h and peaks at 3 to 5 days following a single treatment dose of PMA, time points in which it is unlikely that significant levels of PMA remain in the culture media. Lastly, cells extensively washed after the initial PMA treatment and recultured in PMA free media proceed with the differentiation program (data not shown). The identity of the PMA-dependent stimulus or stimuli which drives chronic IKK activation allowing macrophage differentiation is unknown. However, it is possible that different cytokines produced as a result of PMA treatment may act in an autocrine fashion on the cells to reinforce and perpetuate the differentiation program. This possibility is supported by the observation that monocyte differentiation induces TNF production which, in turn, drives apoptosis in the absence of NF-κB. However, it should be noted that a single dose of TNF in the absence of PMA minimally upregulates p21WAF1/Cip1 expression (Fig. 6). Therefore, it is likely that additional differentiation-inducing signals are initiated by PMA independent of TNF production. Although not exclusive of autocrine factors, it is also possible that internal perturbations initiated by PMA treatment may increase IKK activity. For example, treatment of U937 cells with okadaic acid, an inhibitor of phosphatases 1 and 2A, induces differentiation, cell cycle arrest, and eventual cell death (28, 42, 50). It has previously been suggested that phosphatase 2A may play a role in inhibiting basal IKK activity (13).

The necessary role of NF-κB in macrophage differentiation is relevant and justifies at a functional level the long-term observations that NF-κB is activated during the differentiation of macrophages and that it is present at very high levels in the nuclei of fully differentiated macrophages (24). While we cannot exclude that NF-κB is also influencing specific steps of the cell differentiation process, such as promoting exit from the cell cycle, its role in protecting the cell from undergoing death is clearly highlighted. Overexpression of certain transcription factors alone can be sufficient to drive cell differentiation in a number of cell models (21, 26, 32, 33). During the differentiation of promonocytic cells, NF-κB is potently and persistently activated. Whether this activation is driving differentiation or merely a consequence thereof was unknown. Our data suggest that NF-κB may not be driving differentiation but rather is necessary for surviving the differentiation program. Abundant information supports the role of NF-κB as an antiapoptotic molecule following cell stimulation with apoptosis-inducing ligands such as TNF or chemotherapeutic and ionizing agents (6, 10, 54, 58, 59). However, to our knowledge this study provides the first evidence that the cell differentiation process triggered by chemical agents such as phorbol esters is a significant cell injury that leads to cell death unless NF-κB is concomitantly activated. It remains to be seen whether constitutive, forced activation of NF-κB in promonocytes, in the absence of PMA, alone is sufficient to either force differentiation or confer resistance to subsequent apoptotic stimuli. These experiments are currently under way.

It is unclear whether NF-κB knockouts have an impairment in macrophage differentiation since RelA animals are nonviable. Further, double knockouts of the p50 and p52 NF-κB components, which theoretically would render RelA inactive, have other deficiencies which could impose upon a dificiency in macrophage development (27). Our data, however, suggest that NF-κB activity is important for macrophage development and raise the question as to whether NF-κB activity is involved in differentiation of other specific cell lineages. Knockout experiments, although a valuable tool, may be unable to completely address this issue (26, 33). In vivo, it is possible that other members of the Rel family may compensate for the differentiation of specific cell lineages. Overlying mortalities and morbidities such as seen with the nonviable RelA knockout could make observations difficult and confusing. Finally, NF-κB activity may be important for discrete steps in cell-lineage-specific development. For example, PU.1 knockout mice lack both mature macrophages and granulocytes since PU.1 expression is necessary for myeloid lineage commitment of pluripotent progenitors (47). However, overexpression of PU.1 in cells cannot drive further differentiation of myeloblasts to monocytes (43, 48), suggesting that PU.1 has a distinct role at a specific stage of the differentiation program of pluripotent progenitors. Knockout experiments may therefore mask the specific cell type and cell stage requirements of a gene because of underlying pathologies.

A most intriguing observation is the fact that p21WAF1/Cip1, generally considered a protein restricted to the nuclear compartment in which it exerts its inhibition of CDK and thus regulates cell cycle progression, is in the unique case of macrophages, predominantly located in the cytosol, where it exerts antiapoptotic functions (1). Based on our results demonstrating that NF-κB is required for cell survival, the link confirmed in this study between NF-κB and p21WAF1/Cip1 during the process of macrophage differentiation is noteworthy for several reasons. First and foremost, our results support that, in cells of monocytic lineage, including primary macrophages, p21WAF1/Cip1 is an NF-κB-dependent gene and thus a potential effector of the antiapoptotic effects of NF-κB. The mechanism whereby NF-κB ultimately leads to p21WAF1/Cip1 upregulation is unknown. NF-κB may directly drive the transcription of p21WAF1/Cip1, as suggested by Fig. 6, or have other effects on p21WAF1/Cip1 expression, such as on protein or mRNA stability. Experiments are currently under way to explore the link of NF-κB to p21WAF1/Cip1. Likewise, it will be of interest to investigate whether cells with constitutive levels of NF-κB in the nuclei, such as mature B lymphocytes or transformed cancer cells, also demonstrate upregulation of p21WAF1/Cip1. If this were the case, it could be postulated that under certain conditions, beyond those of macrophage differentiation, p21WAF1/Cip1 may exert important apoptotic functions relevant to, e.g., oncogenic processes.

The observation that endogenously produced TNF triggers the apoptosis seen during monocyte differentiation (Fig. 5), coupled with the need for p21WAF1/Cip1 expression for survival, suggests that NF-κB-dependent p21 expression directly opposes TNF-induced apoptosis. This observation agrees with a number of previous reports demonstrating that p21WAF1/Cip1 opposes TNF-induced apoptosis (15, 29, 30). How this mechanism occurs is unknown and warrants further investigation. It should be noted that PMA fails to induce apoptosis in fully differentiated primary human macrophages even when NF-κB is inhibited (data not shown). This implies that the sensitivity to TNF-induced apoptosis is unique to cells actively undergoing differentiation and is not seen in cells that have completed the maturational process. Alternatively, fully differentiated macrophages may have additional antiapoptotic mechanisms such as the upregulation of FLIP (46). Previous studies have suggested that TNF plays an active role in the differentiation of a number of hematopoietic cells. Whether this is true also in monocytes remains unclear. One possibility is that it is the careful balance of TNF-induced apoptosis versus direct differentiation signals which mediate the final maturational outcome.

In summary, we have shown that constitutive activation of NF-κB is required for surviving the monocyte differentiation program and is dependent on the chronic activation of IKK targeting the IκBα SRD. Based on our data with cells stably expressing transdominant IκBα, we propose that the maturation of monocytes involves two distinct signals. The first signal drives the differentiation of the cell and may be independent of NF-κB activity. The second signal, mediated by TNF-α, initiates a death signal in the differentiation monocyte. This death signal is directly opposed by NF-κB activity. Finally, persistent NF-κB activation induces the expression of p21WAF1/Cip1, which may be the critical protein which protects the monocyte from differentiation-induced cell death.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Steven Grant for the p21(AS) U937 cell lines, Christian Rust and Robert Simari for the HA-IκBα 32/36 and AP adenoviruses, Susana Asin for generation of the IκBα U937 cell lines, Hiroko Miyoshi for RNA preparation, David Lynch (Immunex Corporation) for the TNFR-Fc and IL4R-Fc reagents, and Teresa Hoff for assistance in preparing the manuscript. In addition, we thank members of C. V. Paya's laboratory for many thoughtful and stimulating discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asada M, Yamada T, Ichijo H, Delia D, Miyazono K, Fukumuro K, Mizutani S. Apoptosis inhibitory activity of cytoplasmic p21(Cip1/WAF1) in monocytic differentiation. EMBO J. 1999;18:1223–1234. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asin S, Taylor J A, Trushin S, Bren G, Paya C V. Iκκ mediates NF-κB activation in human immunodeficiency virus-infected cells. J Virol. 1999;73:3893–3903. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3893-3903.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baeuerle P A, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baeuerle P A, Henkel T. Function and activation of NF-kappa B in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:141–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bash J, Zong W X, Gelinas C. c-Rel arrests the proliferation of HeLa cells and affects critical regulators of the G1/S-phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6526–6536. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beg A A, Baltimore D. An essential role for NF-kappaB in preventing TNF-alpha-induced cell death. Science. 1996;274:782–784. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beg A A, Sha W C, Bronson R T, Baltimore D. Constitutive NF-kappa B activation, enhanced granulopoiesis, and neonatal lethality in I kappa B alpha-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2736–2746. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casini T, Pelicci P G. A function of p21 during promyelocytic leukemia cell differentiation independent of CDK inhibition and cell cycle arrest. Oncogene. 1999;18:3235–3243. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chellappan S P, Giordano A, Fisher P B. Role of cyclin-dependent kinases and their inhibitors in cellular differentiation and development. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;227:57–103. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71941-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu Z L, McKinsey T A, Liu L, Gentry J J, Malim M H, Ballard D W. Suppression of tumor necrosis factor-induced cell death by inhibitor of apoptosis c-IAP2 is under NF-kappaB control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10057–10062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cory S. Regulation of lymphocyte survival by the bcl-2 gene family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:513–543. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Martin R, Schmid J A, Hofer-Warbinek R. The NF-kappaB/Rel family of transcription factors in oncogenic transformation and apoptosis. Mutat Res. 1999;437:231–243. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiDonato J A, Hayakawa M, Rothwarf D M, Zandi E, Karin M. A cytokine-responsive IkappaB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-kappaB. Nature. 1997;388:548–554. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dignam J D, Lebovitz R M, Roeder R G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–89. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donato N J, Perez M. Tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis stimulates p53 accumulation and p21WAF1 proteolysis in ME-180 cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5067–5072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehinger M, Nilsson E, Persson A M, Olsson I, Gullberg U. Involvement of the tumor suppressor gene p53 in tumor necrosis factor-induced differentiation of the leukemic cell line K562. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.el-Deiry W S, Tokino T, Velculescu V E, Levy D B, Parsons R, Trent J M, Lin D, Mercer W E, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fahlman C, Jacobsen F W, Veiby O P, McNiece I K, Blomhoff H K, Jacobsen S E. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) potently enhances in vitro macrophage production from primitive murine hematopoietic progenitor cells in combination with stem cell factor and interleukin-7: novel stimulatory role of p55 TNF receptors. Blood. 1994;84:1528–1533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foo S Y, Nolan G P. NF-kappaB to the rescue: RELs, apoptosis and cellular transformation. Trends Genet. 1999;15:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01719-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freemerman A J, Vrana J A, Tombes R M, Jiang H, Chellappan S P, Fisher P B, Grant S. Effects of antisense p21 (WAF1/CIP1/MDA6) expression on the induction of differentiation and drug-mediated apoptosis in human myeloid leukemia cells (HL-60) Leukemia. 1997;11:504–513. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freytag S O. Enforced expression of the c-myc oncogene inhibits cell differentiation by precluding entry into a distinct predifferentiation state in G0/G1. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1614–1624. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.4.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman A D, Krieder B L, Venturelli D, Rovera G. Transcriptional regulation of two myeloid-specific genes, myeloperoxidase and lactoferrin, during differentiation of the murine cell line 32D C13. Blood. 1991;78:2426–2432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghoda L, Lin X, Greene W C. The 90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase (pp90rsk) phosphorylates the N-terminal regulatory domain of IkappaBalpha and stimulates its degradation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21281–21288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin G E, Leung K, Folks T M, Kunkel S, Nabel G J. Activation of HIV gene expression during monocyte differentiation by induction of NF-kappa B. Nature. 1989;339:70–73. doi: 10.1038/339070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffin G E, Leung K, Folks T M, Kunkel S, Nabel G J. Induction of NF-kappa B during monocyte differentiation is associated with activation of HIV-gene expression. Res Virol. 1991;142:233–238. doi: 10.1016/0923-2516(91)90062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henkel G W, McKercher S R, Leenen P J, Maki R A. Commitment to the monocytic lineage occurs in the absence of the transcription factor PU.1. Blood. 1999;93:2849–2858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iotsova V, Caamano J, Loy J, Yang Y, Lewin A, Bravo R. Osteopetrosis in mice lacking NF-kappaB1 and NF-kappaB2. Nat Med. 1997;3:1285–1289. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishida Y, Furukawa Y, Decaprio J A, Saito M, Griffin J D. Treatment of myeloid leukemic cells with the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid induces cell cycle arrest at either G1/S or G2/M depending on dose. J Cell Physiol. 1992;150:484–492. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041500308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Javelaud D, Wietzerbin J, Delattre O, Besancon F. Induction of p21Waf1/Cip1 by TNFalpha requires NF-kappaB activity and antagonizes apoptosis in Ewing tumor cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:61–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang Y, Porter A G. Prevention of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-mediated induction of p21WAF1/CIP1 sensitizes MCF-7 carcinoma cells to TNF-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:691–697. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karin M. The beginning of the end: IkappaB kinase (IKK) and NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27339–27342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly L M, Englmeier U, Lafon I, Sieweke M H, Graf T. MafB is an inducer of monocytic differentiation. EMBO J. 2000;19:1987–1997. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kowenz-Leutz E, Herr P, Niss K, Leutz A. The homeobox gene GBX2, a target of the myb oncogene, mediates autocrine growth and monocyte differentiation. Cell. 1997;91:185–195. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lernbecher T, Muller U, Wirth T. Distinct NF-kappa B/Rel transcription factors are responsible for tissue-specific and inducible gene activation. Nature. 1993;365:767–770. doi: 10.1038/365767a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liou H C, Sha W C, Scott M L, Baltimore D. Sequential induction of NF-κB/Rel family proteins during B-cell terminal differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5349–5359. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luque I, Gelinas C. Rel/NF-kappa B and I kappa B factors in oncogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 1997;8:103–111. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1997.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macleod K F, Sherry N, Hannon G, Beach D, Tokino T, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, Jacks T. p53-dependent and independent expression of p21 during cell growth, differentiation, and DNA damage. Genes Dev. 1995;9:935–944. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mak N K, Leung K N, Fung M C, Hapel A J. Augmentation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced monocytic differentiation of a myelomonocytic leukemia (WEHI-3B JCS) by pertussis toxin. Immunobiology. 1994;190:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(11)80279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McElhinny J A, Trushin S A, Bren G D, Chester N, Paya C V. Casein kinase II phosphorylates IκB α at S-283, S-289, S-293, and T-291 and is required for its degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:899–906. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyamoto S, Seufzer B J, Shumway S D. Novel IκB α proteolytic pathway in WEHI231 immature B cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:19–29. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mosialos G. The role of Rel/NF-kappa B proteins in viral oncogenesis and the regulation of viral transcription. Semin Cancer Biol. 1997;8:121–129. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1997.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakajima K, Yamanaka Y, Nakae K, Kojima H, Ichiba M, Kiuchi N, Kitaoka T, Fukada T, Hibi M, Hirano T. A central role for Stat3 in IL-6-induced regulation of growth and differentiation in M1 leukemia cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:3651–3658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nerlov C, Graf T. PU.1 induces myeloid lineage commitment in multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2403–2412. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen H Q, Hoffman-Liebermann B, Liebermann D A. The zinc finger transcription factor Egr-1 is essential for and restricts differentiation along the macrophage lineage. Cell. 1993;72:197–209. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90660-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oberg F, Botling J, Nilsson K. Macrophages and the cytokine network. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:2044–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perlman H, Pagliari L J, Georganas C, Mano T, Walsh K, Pope R M. FLICE-inhibitory protein expression during macrophage differentiation confers resistance to fas-mediated apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1679–1688. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scott E W, Fisher R C, Olson M C, Kehrli E W, Simon M C, Singh H. PU.1 functions in a cell-autonomous manner to control the differentiation of multipotential lymphoid-myeloid progenitors. Immunity. 1997;6:437–447. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scott E W, Simon M C, Anastasi J, Singh H. Requirement of transcription factor PU.1 in the development of multiple hematopoietic lineages. Science. 1994;265:1573–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.8079170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seitz C S, Deng H, Hinata K, Lin Q, Khavari P A. Nuclear factor kappaB subunits induce epithelial cell growth arrest. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4085–4092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sherr C J, Roberts J M. Inhibitors of mammalian G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1149–1163. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stein G H, Dulic V. Molecular mechanisms for the senescent cell cycle arrest. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1998;3:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor J A, Bren G D, Pennington K N, Trushin S A, Asin S, Paya C V. Serine 32 and serine 36 of IkappaBalpha are directly phosphorylated by protein kinase CKII in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:839–850. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Antwerp D J, Martin S J, Kafri T, Green D R, Verma I M. Suppression of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis by NF-kappaB. Science. 1996;274:787–789. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Antwerp D J, Martin S J, Verma I M, Green D R. Inhibition of TNF-induced apoptosis by NF-kappa B. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:107–111. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(97)01215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Antwerp D J, Verma I M. Signal-induced degradation of IκBα: association with NF-κB and the PEST sequence in IκBα are not required. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6037–45. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verma I M, Stevenson J K, Schwarz E M, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Rel/NF-kappa B/I kappa B family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2723–35. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vrana J A, Saunders A M, Chellappan S P, Grant S. Divergent effects of bryostatin 1 and phorbol myristate acetate on cell cycle arrest and maturation in human myelomonocytic leukemia cells (U937) Differentiation. 1998;63:33–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1998.6310033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang C Y, Cusack J C, Jr, Liu R, Baldwin A S., Jr Control of inducible chemoresistance: enhanced anti-tumor therapy through increased apoptosis by inhibition of NF-kappaB. Nat Med. 1999;5:412–417. doi: 10.1038/7410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang C Y, Mayo M W, Baldwin A S., Jr TNF- and cancer therapy-induced apoptosis: potentiation by inhibition of NF-kappaB. Science. 1996;274:784–7. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Z, Su Z Z, Fisher P B, Wang S, VanTuyle G, Grant S. Evidence of a functional role for the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21(WAF1/CIP1/MDA6) in the reciprocal regulation of PKC activator-induced apoptosis and differentiation in human myelomonocytic leukemia cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;244:105–116. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zandi E, Chen Y, Karin M. Direct phosphorylation of IkappaB by IKKalpha and IKKbeta: discrimination between free and NF-kappaB-bound substrate. Science. 1998;281:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zuniga-Pflucker J C, Di J, Lenardo M J. Requirement for TNF-alpha and IL-1 alpha in fetal thymocyte commitment and differentiation. Science. 1995;268:1906–1909. doi: 10.1126/science.7541554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]