Abstract

Background:

Hospitals are closing after poor financial performance leaving many patients without access to medical care. Identifying the factors associated with financial distress offers hospitals avenues for potential intervention to avoid bankruptcy and closure.

Materials and Methods:

We performed a retrospective analysis of private U.S. hospitals’ financial information from 2011 to 2018. A mixed effects logistic regression model was used with the primary outcome as hospital financial distress (based on the Altman Z-score).

Results:

Our sample included 2,720 private hospitals contributing a total of 20,022 hospital-year observations. The proportion of hospitals experiencing financial distress each year ranged from 22.0% to 24.3%. For-profit status was associated with an increased odds of financial distress (adjusted odds ratio (aOR), 4.36 [95% Confidence Interval (CI) 3.05 – 6.24]) as compared to non-profit status. A higher share of hospital revenue from Medicaid was also associated with increased odds of financial distress (aOR for the highest quartile, 2.28 [95% CI 1.73 – 3.00]) as compared to the lowest quartile. A higher case mix index (aOR for the highest quartile, 0.32 [95% CI 0.23 – 0.46]) and an increased share of hospital revenue from outpatient services (aOR for the highest quartile, 0.34 [95% CI 0.23 – 0.49]) were associated with decreased odds of financial distress as compared to their respective lowest quartiles.

Conclusions:

A significant proportion of private U.S. hospitals experience financial distress. Increasing case complexity and the proportion of patient revenue from outpatient services may represent avenues to avoid financial distress.

Keywords: financial distress, bankruptcy, financial management, hospital administration, Medicaid

Introduction

In 2019, twenty-two hospitals declared bankruptcy.1 Hospitals face a rapidly changing financial environment with frequent modifications to payment processes, market forces, insurance coverage, and reimbursement, and evolutions in medical and surgical care require increasingly large amounts of financial investment from hospitals to consistently deliver high quality care. Given these challenges, many hospitals struggle to generate enough income to sustain and improve their operations. While health care broadly represents an economically stable industry on a national scale, local market forces and changes in regulation and reimbursement can quickly move hospitals from financial stability to financial distress.

Financial distress does not have a precise definition but broadly indicates that an organization is unable to meet its financial obligations.2 When faced with financial distress, organizations aim to identify and execute strategies that avoid sustained insolvency and subsequent bankruptcy. These measures often include eliminating services (e.g. specialty care), reducing the employee workforce, and cutting investment in existing or planned projects. Both the direct costs (e.g. legal and management fees) and indirect costs (e.g. higher interest rates, negatively impacted bond ratings) of financial distress can lead to additional financial problems and can occur even if bankruptcy is avoided. If a hospital’s efforts are unsuccessful in reversing the downward trend in financial performance, bankruptcy becomes a likely outcome, and many hospitals eventually close.3

Between 2011 and 2019, more hospitals closed than opened.4,5 Of the sixty-nine hospitals that ceased providing inpatient services during fiscal years 2018 and 2019, a majority claimed financial reasons as a main cause for closure.5 Unfortunately, evidence suggests that the rate of hospital closure is rising.6 Hospital closures leave many patients without access to essential health care services.7–9 The individual and economic impacts of hospital closures offer evidence that the consequences of closure can be catastrophic for many communities.10

While recent studies offer insight into rural hospital financial distress,11–14 less is known about the financial challenges facing private for-profit and non-profit hospitals. An understanding of the factors associated with hospital financial distress may help managers and policymakers identify at-risk hospitals and adjust management practice and health policy provisions to reduce the likelihood of hospital bankruptcy and closure. While financial distress from poor financial performance may drive many hospital closures, the specific factors associated with financially distressed private hospitals and the differences between for-profit and non-profit hospitals are less well known. The objective of this study was to identify associations between financial distress and the hospital characteristics of private U.S. hospitals.

Methods

Data

We used the Medicare Cost Reports from the Healthcare Cost Report Information System (HCRIS) for years 2011 to 2018 extracted from the RAND Corporation Hospital Data Tool.15–17 Additionally, we used the Dartmouth Atlas to link the hospital zip code to the hospital referral region.18 Our population included general private short-term acute care hospitals. We excluded federal and state government hospitals. We excluded long-term, psychiatric, and pediatric hospitals. We excluded critical access hospitals as these represent small (less than 25 acute care inpatient beds) rural hospitals that receive a different cost-based reimbursement from CMS.19 To avoid the spillover effect of inconsistent ownership status, only hospitals that kept the same ownership (―for-profit‖ or ―non-profit‖) throughout the entire study period were included in the analysis. Details of the exclusion criteria and number of missing values are included in the Appendix (see Figure A.1).

Variables

Financial distress, based on the modified annual Altman Z-score, was the main dependent variable. Financial distress represents a state of poor financial health and indicates that an organization is at risk of default and unable to meet its financial obligations. The Altman Z-score is a common tool that has been used across multiple industries to predict the likelihood of financial distress and bankruptcy.20,21 A modified version of Altman Z-score was validated in the health care industry to predict the likelihood of bankruptcy filing for hospitals.22–24 While previous research focused on a negative operating margin as an indicator of poor financial health,25 the modified Altman Z-score offers a more complete picture of an organization’s financial health than revenue or operating margins alone by incorporating four financial ratios: liquidity, profitability, efficiency, and leverage. The modified Altman Z-score formula for financial distress is: Z = 6.56*X1 + 3.26*X2 + 6.72*X3 + 1.05*X4 where X1 = working capital / total assets, X2 = retained earnings / total assets, X3 = earnings before interest and taxes / total assets, and X4 = total equity / total liabilities.26 An annual Z-score measure was calculated based on the yearly information in each cost report (see Additional Methods in the Appendix). Consistent with previous literature, hospitals were defined as financially distressed if the Altman Z-score was less than 1.8 and healthy if the Z-score greater than or equal to 1.8.24

The main independent variables included ownership, occupancy, case mix index, Medicaid payor mix, and outpatient mix. Ownership was defined as for-profit or non-profit. Occupancy was defined as total inpatient days divided by the bed-days available during the cost period. The case mix index is a CMS reported measure of clinical complexity and resource needs of all discharges.27 Medicaid revenue was defined as the sum of Medicaid reimbursement revenue and Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments. Medicaid payor mix was constructed by dividing Medicaid revenue by operating revenue. Outpatient mix was constructed by dividing outpatient revenue by total patient revenue. Additional covariates included rurality, teaching hospital status, bed size, and the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index. Rurality was constructed as a binary variable from the core based statistical area codes. Teaching status was coded as a binary variable, and a hospital was classified as a ―teaching hospital‖ if it was involved in training residents in an approved Graduate Medical Education program. Based on the number of beds, hospitals were grouped into one of four categories (1–99, 100–199, 200–299, or ≥ 300 beds). Since competitive market dynamics may affect hospital financial performance, we included the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a measure of market concentration, as a covariate. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index was calculated by squaring the share of each hospital discharge-equivalents by year and hospital referral region and then summing these results.28 Each hospital was placed into one of three HHI groups with increasing degrees of market concentration: Unconcentrated (0 – 0.15), Moderately Concentrated (0.16 – 0.25), and Highly Concentrated (0.26 – 1.0).29

For financial metrics, the annual operating revenue, operating expenses, and net profit were extracted. Operating profit was calculated by subtracting operating expenses from operating revenue. We adjusted these financial variables by dividing their values by the discharge equivalents for each year. Discharge equivalents are a measure of hospital output that incorporates both inpatient and outpatient care.30 Operating margin was calculated by dividing operating profit by operating revenue. Total margin was extracted as a comprehensive measure of profitability that includes revenue from core operations as well as other income (e.g. investments, non-patient care activities). Total margin was defined as net profit divided by total revenue. All dollar values were converted to 2018 U.S. dollars.31

Statistical Analysis

We compared unadjusted hospital characteristics by for-profit status. For categorical variables, we used Pearson’s chi-square test. For continuous variables, we performed quantile regression analysis of both financial and non-financial variables to test the equality of median values.32 As previously described for hospital financial data, quantile regression does not assume normal distribution of the variable or equal variance between groups and allows for accurate estimation of the absolute difference in median values between groups with untransformed values (e.g. hospital finances).33

For the regression analysis, a mixed model was used because the panel dataset includes annual sampling from a nearly identical set of hospitals, and observations are not independent of each other. Our mixed effects logistic regression model focused on all private hospitals with financial distress as the dependent variable. We included fixed year effects to account for time-varying trends. We included random hospital effects to account for the correlation between observations from the same hospital across different years. We included random state effects to account for correlated factors (e.g. similar geographic markets and state reimbursement policies) among hospitals from the same state. Random slopes were not included. For the independent variables, the reference groups were as follows: non-profit ownership, urban location, non-teaching hospital, bed group (1–99 beds), unconcentrated HHI, and the lowest quartiles of case mix index, occupancy, Medicaid payor mix, and outpatient mix. Additional regressions were performed post-hoc for sub-populations of for-profit and non-profit hospitals. The Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board did not require review of this study because the research did not involve personally identifiable information from human participants. A two-tailed p value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

A total of 20,022 hospital-years from 2,720 unique hospitals were included with 84.1% of hospitals contributing data in all eight years (see Table A.1 in the Appendix). For calendar year 2018, the general hospital characteristics are included in Table 1. In 2018, a higher proportion of for-profit hospitals experienced financial distress as compared to non-profit hospitals (32.3% vs. 18.1%, p < .001). For-profit hospitals received a smaller share of their revenue from Medicaid services as compared to non-profit hospitals (7.5% vs. 8.5%, p = .003). Between 2011 and 2018, the proportion of distressed hospitals ranged from 22.0% to 24.3% (see Figure A.2 in the Appendix). Regarding the components of financial distress, the median values for X1 (working capital to total assets) and X3 (earnings before interest and taxes to total assets) ratio were higher for for-profit hospitals as compared to non-profit hospitals (X1: 0.17 vs. 0.12, p < .001; X3: 0.13 vs. 0.04, p < .001). The median X4 ratio (total equity to total liability) was lower within for-profit hospitals as compared to non-profit entities (0.02 vs. 1.39, p < .001).

Table 1:

Characteristics of For-Profit and Non-Profit U.S. Hospitals in 2018

| For-Profit | Non-Profit | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Hospitals | 702 | 1730 | |||

| General Characteristics | No. | Summary | No. | Summary | |

| Rural, no. (%) | 702 | 44 (6.3) | 1730 | 92 (5.3) | .36 |

| Teaching Hospital, no. (%) | 702 | 165 (23.5) | 1730 | 757 (43.8) | < .001 |

| Hospital Bed Size, no. (%) | 702 | 1729 | < .001 | ||

| 1 – 99 | 341 (48.6) | 521 (30.1) | |||

| 100 – 199 | 193 (27.5) | 488 (28.2) | |||

| 200 – 299 | 91 (13.0) | 291 (16.8) | |||

| ≥ 300 | 77 (11.0) | 429 (24.8) | |||

| Case Mix Index (median, IQR) | 697 | 1.57 (1.32 – 1.84) | 1725 | 1.55 (1.38 – 1.74) | .02 |

| Occupancy (median, IQR) | 698 | 41.3 (25.4 – 61.8) | 1727 | 58.2 (42.9 – 70.4) | < .001 |

| Medicaid Payor Mix (median, IQR) | 673 | 7.5 (3.5 – 12.6) | 1713 | 8.5 (5.4 – 12.9) | .003 |

| Outpatient Mix (median, IQR) | 700 | 53.4 (40.9 – 67.5) | 1722 | 57.1 (46.6 – 68.5) | < .001 |

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, no. (%) | 700 | 1729 | .67 | ||

| Unconcentrated | 383 (54.7) | 912 (52.8) | |||

| Moderate Concentration | 147 21.0) | 375 (21.7) | |||

| High Concentration | 170 (24.3) | 442 (25.6) | |||

| Financially Distressed, no. (%) | 702 | 227 (32.3) | 1730 | 313 (18.1) | < .001 |

| X1: Working Capital / Total Assets (median, IQR) | 702 | 0.17 (0.03 – 0.31) | 1730 | 0.12 (0.04 – 0.26) | < .001 |

| X2: Retained Earnings / Total Assets (median, IQR) | 702 | 0.64 (0.15 – 1.19) | 1730 | 0.60 (0.39 – 0.79) | .12 |

| X3: Earnings Before Interest and Taxes / Total Assets (median, IQR) | 702 | 0.13 (−0.02 – 0.31) | 1730 | 0.04 (−0.01 – 0.09) | < .001 |

| X4: Total Equity / Total Liabilities (median, IQR) | 702 | 0.02 (−1.25 – 1.38) | 1730 | 1.39 (0.56 – 3.25) | < .001 |

Source: Authors’ analysis of Healthcare Cost Reports, 2011–2018

Notes:

Represents the p value of chi-square tests for categorical variables and the p values of quantile regressions to test the equality of medians for continuous variables. Abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range. Medicaid Payor Mix represents Medicaid revenue as a percentage of operating revenue. Outpatient Mix represents outpatient revenue as a percentage of total patient revenue. Herfindahl-Hirschman Index represents the sum of the square of each hospital’s share of discharges in the hospital referral region. The categories were unconcentrated (0 – 0.15), moderate (0.15 – 0.25), and high (0.26 – 1.0).

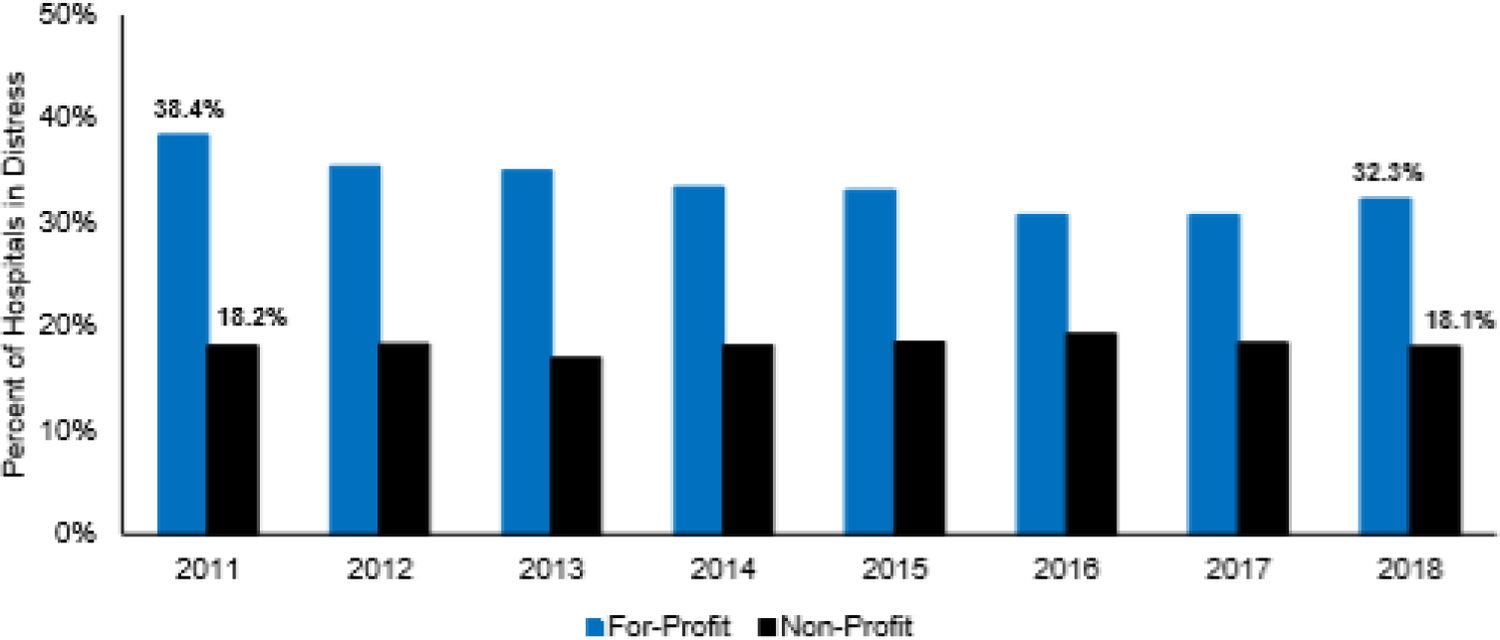

During the study period, the proportion of distressed for-profit hospitals ranged from 30.7% to 38.4% whereas the proportion of distressed non-profit hospitals ranged from 17.0% to 19.3% (Figure 1). Between 2011 and 2018, the median annual operating revenue per discharge equivalent ranged from $14,096 to $15,391 among for-profits and from $14,611 to $15,818 among non-profits, and the median annual operating expense per discharge equivalent ranged from $12,925 to $13,985 among for-profits and from $13,814 to $14,921 among non-profits (see Figure A.3 in the Appendix). The median annual operating profit per discharge equivalent ranged from $1,022 to $1,336 among for-profits and from $577 to $760 among non-profits (see Figure A.4). The median annual operating margin ranged from 6.9% to 8.6% among for-profits and from 4.0% to 4.6% among non-profits, and the median annual total margin ranged from 6.7% to 8.6% among for-profits and from 4.0% to 5.1% among non-profits (Figure A.5 in the Appendix).

Figure 1: Proportion of For-Profit and Non-Profit Hospitals Experiencing Financial Distress.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Healthcare Cost Reports, 2011–2018.

Notes: Chi-square tests were performed comparing the proportion of distressed hospitals in each year by ownership status, and comparisons were statistically significant (p < .001) in each year demonstrating a higher proportion of for-profit hospitals in distress as compared to non-profit hospitals.

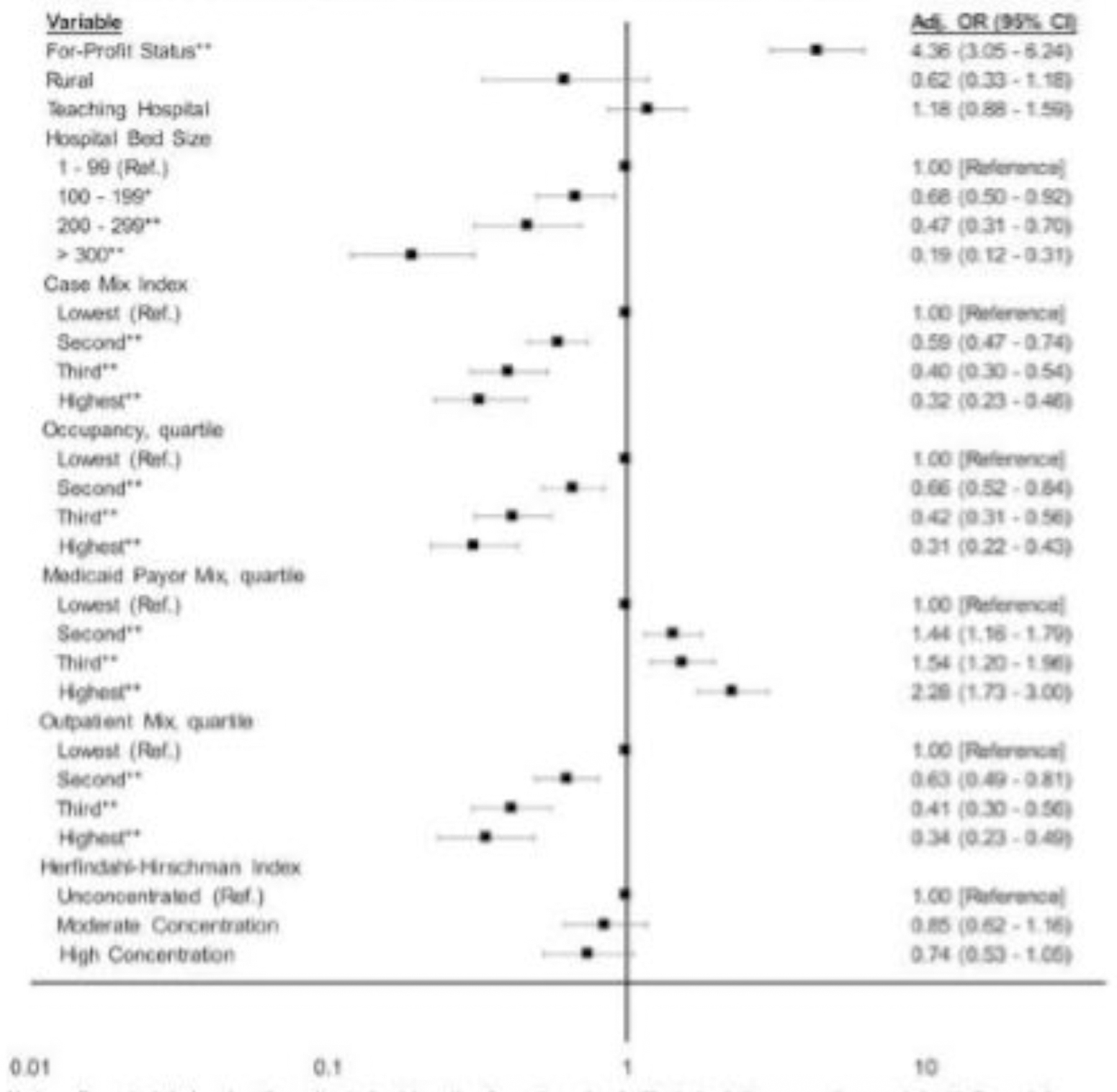

Three generalized linear mixed models were created for (1) all hospitals, (2) for-profit hospitals, and (3) non-profit hospitals with financial distress as the dependent binary outcome variable. In the first model of all hospitals, for-profit status was independently associated with increased odds of financial distress as compared to non-profit status (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.36 [95% CI 3.05 – 6.24], Figure 2, see Appendix Table A.2 for full model). A higher share of hospital revenue from Medicaid was also associated with increased odds of financial distress (aOR for the highest quartile, 2.28 [95% CI 1.73 – 3.00]). In contrast, a higher number of hospital beds (aOR for hospitals with ≥ 300 beds, 0.19 [95% CI 0.12 – 0.31]), a higher case mix index (aOR for the highest quartile, 0.32 [95% CI 0.23 – 0.46]), higher occupancy (aOR for the highest quartile, 0.31 [95% CI 0.22 – 0.43]), and increased outpatient mix (aOR for the highest quartile, 0.34 [95% CI 0.23 – 0.49]) were associated with decreased odds of financial distress as compared to their respective reference groups.

Figure 2: Factors Associated with Financial Distress in Private Hospitals.

Source: Authors’ analysis of Healthcare Cost Reports, 2011–2018.

Notes: Forest plot showing the adjusted odds ratios from the mixed effects logistic regression model with financial distress as the dependent variable. For Case Mix Index, the median value in each quartile was 1.23 (lowest), 1.46 (second), 1.64 (third), 1.94 (highest). For occupancy, the median value in each quartile was 27% (lowest), 46% (second), 61% (third), and 75% (highest). For Medicaid Payor Mix, the median value in each quartile was 3.1% (lowest), 7.2% (second), 11.1% (third), and 19.2% (highest). For Outpatient Mix, the median value in each quartile was 35% (lowest), 48% (second), 59% (third), and 72% (highest). For Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, unconcentrated was 0.00 – 0.15 [reference], moderate was 0.15 – 0.25, and high was 0.26 – 1.00.

* p < .05

** p < .001

Among for-profit hospitals, a higher number of hospital beds (aOR for hospitals with ≥ 300 beds, 0.15 [95% CI 0.06 – 0.37]), a higher case mix index (aOR for the highest quartile, 0.17 [95% CI 0.10 – 0.29]), and higher occupancy (aOR for the highest quartile, 0.38 [95% CI 0.21 – 0.67]) were associated with decreased odds of financial distress as compared to their respective reference groups (Table 2). A larger share of hospital revenue from Medicaid services was associated with increased odds of financial distress as compared to the lowest quartile of Medicaid mix (aOR, 1.62 [95% CI 1.04 – 2.54]).

Table 2:

Factors Associated with Financial Distress: For-Profit and Non-Profit Hospitals

| For-Profit | Non-Profit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Hospitals | 789 | 1,844 | ||

| No. Hospital-Years | 5,517 | 13,847 | ||

| Variable | aOR (95% CI) | P Value | aOR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Year | ||||

| 2012 | 0.81 (0.58 – 1.15) | .24 | 1.05 (0.8 – 1.37) | .72 |

| 2013 | 0.84 (0.60 – 1.19) | .33 | 0.91 (0.69 – 1.19) | .49 |

| 2014 | 0.71 (0.50 – 1.02) | .06 | 1.08 (0.82 – 1.43) | .57 |

| 2015 | 0.74 (0.52 – 1.06) | .10 | 1.23 (0.93 – 1.62) | .15 |

| 2016 | 0.65 (0.45 – 0.94) | .02 | 1.42 (1.06 – 1.89) | .02 |

| 2017 | 0.72 (0.50 – 1.04) | .08 | 1.36 (1.01 – 1.82) | .04 |

| 2018 | 0.87 (0.60 – 1.27) | .47 | 1.47 (1.09 – 1.98) | .01 |

| Rural | 1.43 (0.52 – 3.95) | .49 | 0.32 (0.14 – 0.74) | .01 |

| Teaching Hospital | 1.03 (0.62 – 1.71) | .91 | 1.21 (0.83 – 1.75) | .33 |

| Hospital Bed Size | ||||

| 1 – 99 | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | ||

| 100 – 199 | 0.97 (0.59 – 1.6) | .90 | 0.53 (0.36 – 0.79) | .002 |

| 200 – 299 | 1.11 (0.57 – 2.15) | .77 | 0.27 (0.16 – 0.45) | < .001 |

| ≥ 300 | 0.15 (0.06 – 0.37) | < .001 | 0.15 (0.08 – 0.27) | < .001 |

| Case Mix Index, quartile † | ||||

| Lowest | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | ||

| Second | 0.45 (0.30 – 0.67) | < .001 | 0.71 (0.52 – 0.95) | .02 |

| Third | 0.32 (0.20 – 0.51) | < .001 | 0.49 (0.33 – 0.72) | < .001 |

| Highest | 0.17 (0.10 – 0.29) | < .001 | 0.47 (0.29 – 0.76) | .002 |

| Occupancy, quartile ‡ | ||||

| Lowest | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | ||

| Second | 0.86 (0.60 – 1.23) | .42 | 0.54 (0.39 – 0.75) | < .001 |

| Third | 0.48 (0.30 – 0.77) | .002 | 0.36 (0.24 – 0.53) | < .001 |

| Highest | 0.38 (0.21 – 0.67) | .001 | 0.26 (0.17 – 0.40) | < .001 |

| Medicaid Payor Mix, quartile § | ||||

| Lowest | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | ||

| Second | 1.40 (0.97 – 2.01) | .07 | 1.39 (1.05 – 1.84) | .02 |

| Third | 1.29 (0.86 – 1.92) | .22 | 1.62 (1.19 – 2.21) | .002 |

| Highest | 1.62 (1.04 – 2.54) | .03 | 2.65 (1.87 – 3.77) | < .001 |

| Outpatient Mix, quartile ¶ | ||||

| Lowest | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | ||

| Second | 0.91 (0.61 – 1.35) | .64 | 0.48 (0.35 – 0.66) | < .001 |

| Third | 0.68 (0.42 – 1.10) | .12 | 0.29 (0.19 – 0.43) | < .001 |

| Highest | 0.75 (0.43 – 1.32) | .32 | 0.19 (0.12 – 0.32) | < .001 |

| Herfindahl-Hirschman Index | ||||

| Unconcentrated | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | ||

| Moderate Concentration | 1.38 (0.84 – 2.27) | .20 | 0.62 (0.41 – 0.92) | .02 |

| High Concentration | 0.90 (0.52 – 1.58) | .73 | 0.67 (0.44 – 1.07) | .07 |

| Intercepts | ||||

| Random Intercept Variance: Hospital | 7.86 (6.57 – 9.40) | 9.27 (8.16 – 10.52) | ||

| Random Intercept Variance: State | 0.58 (0.17 – 1.99) | 0.49 (0.25 – 0.97) | ||

| Overall Wald Chi-Square Test | 133.73** | 203.29** | ||

Abbreviations: aOR = adjusted odds ratio, CI = confidence interval

The median value in each quartile was 1.18 (lowest), 1.46 (second), 1.64 (third), and 2.14 (highest) in for-profits and 1.25 (lowest), 1.46 (second), 1.64 (third), 1.89 (highest) in non-profits.

Measured as inpatient days divided by bed days available. The median value in each quartile was 24% (lowest), 45% (second), 60% (third), and 75% (highest) within for-profits and 29% (lowest), 46%, 61%, and 75% (highest) within non-profits.

Measured as Medicaid revenue divided by operating revenue. The median value in each quartile was 2.1% (lowest), 7.2% (second), 11.1% (third), and 19.8% (highest) within for-profits and 3.4% (lowest), 7.2%, 11.1%, and 18.9% (highest) within non-profits.

Measured as outpatient revenue divided by total patient revenue. The median value in each quartile was 33% (lowest), 48% (second), 59% (third), and 73% (highest) within for-profits and 36% (lowest), 48%, 59%, and 72% (highest) within non-profits.

p value ≤ .001

Among non-profit hospitals, hospitals with ≥ 300 beds (aOR, 0.15 [95% CI 0.08 – 0.27]), a higher case mix index (aOR for the highest quartile, 0.47 [95% CI 0.29 – 0.76]), higher occupancy (aOR for the highest quartile, 0.26 [95% CI 0.17 – 0.40]), increased outpatient mix (aOR for the highest quartile, 0.19 [95% CI 0.12 – 0.32]), and moderate market concentration (aOR, 0.62 [95% CI 0.41 – 0.93]) were associated with decreased odds of financial distress as compared to their respective reference groups. A larger share of hospital revenue from Medicaid services was associated with increased odds of financial distress as compared to the lowest Medicaid mix quartile (aOR, 2.65 [95% CI 1.87 – 3.77]).

Discussion

Our study reveals that nearly one-fourth of private hospitals experience financial distress each year, and for-profit private hospitals are at even greater risk of financial distress than their non-profit counterparts. Our analysis suggests that for-profit status is independently associated with hospital financial distress.

Our findings are consistent with prior literature. A previous study demonstrated that 27% of all U.S. acute care hospitals experience negative operating margins.34 Our analysis suggests that a narrow focus on profit margins may provide an incomplete picture of a hospital’s financial health. While for-profit hospitals had higher margins than their non-profit counterparts in our study, a higher proportion of for-profit hospitals experienced financial distress. The increased probability of for-profit hospitals experiencing financial distress may be related to higher levels of debt relative to equity given the lower equity to debt ratio within for-profits compared to non-profits. For-profit entities may not have access to certain sources of capital (e.g. endowments) that are available to non-profit hospitals, and for-profit entities may increase their debt burden to compensate. Our overall findings are consistent with other recent studies on predictors of financial distress in rural13 and acute care23 hospitals. A recent study of 310 public and private acute care hospitals in Texas demonstrated that 14% to 16% of acute care hospitals experienced financial distress, and distressed hospitals had fewer beds, less outpatient revenue, and lower patient acuity. Our study focused exclusively on private hospitals, included a larger sample size of hospitals across the U.S., and more years of data sampling, and these differences may explain why our proportion of distressed hospitals is higher.

Our findings that a higher case mix index, higher occupancy, and a higher outpatient mix protect against financial distress are consistent with previous literature.4,5,13 Hospitals that provide more complex and resource-intensive care may capture reimbursement opportunities that other hospitals miss. Hospitals that consistently maintain higher levels of occupancy would have a higher likelihood of receiving and forecasting consistent revenue. Hospitals with a greater share of outpatient services may gain financial stability through improved efficiency. In contrast, an increased risk of financial distress was seen among hospitals with a higher proportion of operating revenue from Medicaid payments, and this finding is not surprising given that Medicaid and Medicare reimbursements are generally below private insurance rates.35,36

Stratifying the private hospital population by for-profit and non-profit status revealed that case mix index and occupancy remained drivers of decreased odds of distress in both groups, but differences emerged regarding market competition. A protective effect of decreased market competition was evident for non-profit hospitals in moderate concentration settings, but these findings were not seen among for-profit hospitals. Previous work identified that hospitals in increasing competitive environments had higher risks of closure.37,38 As hospitals open, close, and merge with larger health systems, hospitals—particularly non-profits—may need to constantly re-evaluate their local market competition to better assess their financial health and long-term outlook.

Our study includes notable limitations. First, this study was retrospective and limited to hospitals that report data to the HCRIS, and sampling bias may be present. Our study did not include the private hospitals that did not submit Medicare Cost Reports. Second, there may be multiple years of data from certain hospitals and only limited years of data from other hospitals with variation among these groups in the spectrum of financial performance creating the possibility of skewed findings. We acknowledge that hospitals could have either not reported or closed, and our data do not provide sufficient granularity to determine different closure rates among for-profit and non-profit entities. Reassuringly, most hospitals (84%) provided data for all eight years. Third, HCRIS has the known limitation of incomplete data. However, the percent of missing data was low for the variables included in the analysis. Fourth, our analysis was limited to private hospitals and may not be generalizable. Previous studies of hospital financial distress often included government, critical access hospitals, or rural hospitals, and our findings may not be generalizable to these other hospital populations. Fifth, data were not consistently available regarding hospitals’ interest expenses related to their liabilities. Interest expense would offer insight into the annual financial burden associated with existing liabilities. Unfortunately, more than 50% of values were missing for interest expense payments in the database. Given the large degree of missing data, we were unable to include this variable as a potential covariate in our financial distress model.

Our findings have important research and policy implications. Future research should expand on the types of services and interventions that may help hospitals avoid financial distress. Certain service lines and health system affiliation may offer different financial advantages among certain hospital environments, and further clarification on the type and degree of financial protection provided may help hospital managers identify strategies for financial solvency. Our findings highlight how occupancy plays an outsized role in the financial viability of our health care system. Policy leaders may need to consider introducing legislation that decouples a hospital’s financial vulnerability from its occupancy. Additionally, policymakers should consider legislative measures to support financially struggling hospitals by increasing Medicaid’s baseline reimbursement rates and by avoiding cuts to DSH payments. Over the past decade, government policy aimed to reduce Medicaid DSH payments.39 However, research suggests that substantial variability exists across states in the degree to which these reimbursements cover costs. After accounting for DSH payments, hospitals in high-paying states received reimbursement at 130% of costs, but hospitals in low-paying states only received 81% of Medicaid costs.40 Additional analysis suggests that Medicaid reimbursement with DSH payments may only cover 94% of Medicaid costs,41 which leaves many hospitals without financial incentives to provide care for this vulnerable population. Additional government support may not only help increase access to care for Medicaid patients,42 but also may help hospitals—particularly those providing care to underserved populations—avoid financial distress and closure.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a higher proportion of for-profit hospitals experience financial distress as compared to non-profit hospitals. Across multiple systems and geographies, hospitals remain at risk for financial failure and subsequent bankruptcy and closure. The evolving landscape of financial reimbursement for health care services creates uncertainty around which hospitals will be able to survive any significant stress to the health care system. Additional models to identify factors associated with financial distress may allow for hospitals to detect evolving risks in their financial position and to intervene before insolvency arises.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A significant proportion of private hospitals experience financial distress

For-profit status was associated with an increased risk of financial distress

A higher share of Medicaid revenue was associated with increased odds of distress

Funding:

This work was supported by the Research Training in Alimentary Tract Surgery T32 Fellowship Award (T32DK007754) and the Association for Academic Surgery Resident Research Fellowship Award.

Role of Funder/Sponsor:

The funders and sponsors did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors do not have any conflict of interests.

Contributor Information

Samuel J. Enumah, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 75 Francis Street, CA-034, Boston, MA 02115.

David C. Chang, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Codman Center for Clinical Effectiveness in Surgery, 165 Cambridge Street, Suite 403, Boston, MA 02114.

References

- 1.Ellison A. 22 Hospital bankruptcies in 2019. Becker’s Healthcare. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/22-hospital-bankruptcies-in-2019.html. Accessed March 29, 2020.

- 2.Agostini M. Corporate Financial Distress: Going Concern Evaluation in both International and U.S. Contexts. In: 1st ed. Palgrave Pivor, Cham; 2018:5–47. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-78500-4_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landry AY, Landry RJ 3rd. Factors associated with hospital bankruptcies: a political and economic framework. J Healthc Manag. 2009;54(4):252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MedPac. Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy 2018.; 2018. http://medpac.gov/docs/defaultsource/reports/mar18_medpac_entirereport_sec_rev_0518.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 5.MedPac. Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy 2020.; 2020. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/defaultsource/reports/mar20_entirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 6.Kaufman BG, Thomas SR, Randolph RK, et al. The Rising Rate of Rural Hospital Closures. J Rural Health. 2016;32(1):35–43. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou S, Deily ME, Li S. Travel distance and health outcomes for scheduled surgery. Med Care. 2014;52(3):250–257. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozhimannil KB, Hung P, Henning-Smith C, Casey MM, Prasad S. Association Between Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services and Birth Outcomes in Rural Counties in the United States. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1239–1247. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsia RY-J, Shen Y-C. Rising closures of hospital trauma centers disproportionately burden vulnerable populations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(10):1912–1920. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes GM, Slifkin RT, Randolph RK, Poley S. The effect of rural hospital closures on community economic health. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(2):467–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00497.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pink GH, Holmes GM, D’Alpe C, Strunk LA, McGee P, Slifkin RT. Financial indicators for critical access hospitals. J Rural Health. 2006;22(3):229–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes GM, Pink GH, Friedman SA. The financial performance of rural hospitals and implications for elimination of the Critical Access Hospital program. J Rural Health. 2013;29(2):140–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2012.00425.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes GM, Kaufman BG, Pink GH. Predicting Financial Distress and Closure in Rural Hospitals. J Rural Health. 2017;33(3):239–249. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai G, Yehia F, Chen W, Anderson GF. Varying Trends In The Financial Viability Of US Rural Hospitals, 2011–17. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(6):942–948. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.RAND Corporation. RAND Corporation Data Tool. https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL303.html. Accessed March 31, 2020.

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Healthcare Provider Cost Reporting Information System. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Downloadable-Public-Use-Files/Cost-Reports. Accessed March 31, 2020.

- 17.RAND Corporation. RAND Hospital Data. https://www.hospitaldatasets.org/faq. Published 2019. Accessed March 31, 2020.

- 18.The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. Dartmouth Atlas. https://atlasdata.dartmouth.edu/. Accessed June 15, 2020.

- 19.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Critical Access Hospitals: Medicare Learning Network Booklet. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/CritAccessHospfctsht.pdf. Published 2019.

- 20.Altman E. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and prediction of corporate bankruptcy. J Finance. 1968;23(4):589–609. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altman EI. Applications of Distress Prediction Models : What Have We Learned After 50 Years from the Z-Score Models ? 2018. doi: 10.3390/ijfs6030070 [DOI]

- 22.Ramamonjiarivelo Z, Weech-Maldonado R, Hearld L, Menachemi N, Epane J, OConnor S. Public hospitals in financial distress : Is privatization a strategic choice ? Heal Care Manag Rev. 2015;40(4):337–347. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langabeer JR 2nd, Lalani KH, Champagne-Langabeer T, Helton JR. Predicting Financial Distress in Acute Care Hospitals. Hosp Top. 2018;96(3):75–79. doi: 10.1080/00185868.2018.1451262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puro N, Borkowski N, Hearld L, et al. Financial Distress and Bankruptcy Prediction : A Comparison of Three Financial Distress Prediction Models in Acute Care Hospitals. J Health Care Finance. 2019;(Fall 2019):1–15. http://healthfinancejournal.com/index.php/johcf/article/view/199/202.

- 25.Ly DP, Jha AK, Epstein AM. The association between hospital margins, quality of care, and closure or other change in operating status. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1291–1296. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1815-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altman E. Predicting Financial Distress Of Companies: Revisiting The Z-Score And Zeta. Handb Res Methods Appl Empir Financ. 2000;5. doi: 10.4337/9780857936097.00027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Case Mix Index. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Acute-Inpatient-Files-for-Download-Items/CMS022630. Accessed March 31, 2020. [PubMed]

- 28.United States Department of Justice. Herfindahl-Hirschman Index. https://www.justice.gov/atr/herfindahl-hirschman-index. Published 2018. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- 29.Health Care Cost Institute. Healthy Marketplace Index.; 2019. https://healthcostinstitute.org/research/hmi-interactive#HMI-Concentration-Index.

- 30.Cleverley WO. Time to replace adjusted discharges. J Healthc Financ Manag Assoc. 2014;68(5):84–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed June 18, 2020.

- 32.Conroy R What hypotheses do ―nonparametric‖ two-group tests actually test. Stata J. 2012;12(2):182–190. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsen CS, Clark AE, Thomas AM, Cook LJ. Comparing least-squares and quantile regression approaches to analyzing median hospital charges. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(7):866–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayford T, Nelson L Diorio A. Projecting Hospitals’ Profit Margins under Several Illustrative Scenarios: Working Paper 2016–04.; 2016. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/51920.

- 35.Lopez E, Neuman T, Jacobson G. How Much More than Medicare Do Private Insurers Pay? A Review of the Literature.; 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/how-much-more-than-medicare-do-private-insurers-pay-a-review-of-the-literature/.

- 36.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Medicaid Hospital Payment: A Comparison across States and to Medicare.; 2017. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Medicaid-Hospital-Payment-A-Comparison-across-States-and-to-Medicare.pdf.

- 37.Kim TH. Factors associated with financial distress of nonprofit hospitals. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2010;29(1):52–62. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0b013e3181cca2c5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Succi MJ, Lee SY, Alexander JA. Effects of market position and competition on rural hospital closures. Health Serv Res. 1997;31(6):679–699. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Department of Health and Human Services. Medicaid Program: State Disproportionate Share Hospital Allotment Reductions.; 2019. https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2019-20731.pdf.

- 40.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Chapter 3: Improving Data as the First Step to a More Targeted Disproportionate Share Hospital Policy.; 2016. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/improving-data-as-the-first-step-to-a-more-targeted-disproportionate-share-hospital-policy/.

- 41.Cunningham P, Rudowitz R, Young K, Garfield R, Foutz. Understanding Medicaid Hospital Payments and the Impact of Recent Policy Changes.; 2016. http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-understanding-medicaid-hospital-payments-and-the-impact-of-recent-policy-changes.

- 42.Decker SL. In 2011 nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Medicaid patients, but rising fees may help. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1673–1679. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.