Abstract

Background:

Surgeons make important contributions to basic science research and are in a unique position to innovate scientifically. The number of surgeons pursuing basic science research has been declining over the past two decades. We sought to describe perceived barriers to surgeons’ pursuit of basic science research and identify interventions that mitigate these obstacles.

Materials & Methods:

An online survey was sent to chairs of academic surgery departments and practicing surgeons involved in basic science research. A subset of these participants were interviewed about their experiences. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and uploaded to NVivo. Two coders developed a codebook using inductive content analysis to identify relevant themes.

Results:

97 people responded to the survey, 27 (29%) were department chairs. Major barriers to basic science research for all respondents were lack of funding, clinical duties and lack of dedicated time for research. Nine surgeons and three departmental chairs were subsequently interviewed. The importance of having clear research goals and timetables with specific plans for attaining funding were mentioned by all. Chairs described the usefulness of embedding early surgeon scientists in their scientific mentors’ labs in a post-doctoral model. Additionally, departmental leaders must actively work to protect surgeon scientists from encroaching clinical and administrative demands.

Conclusions:

While barriers to surgeons’ pursuit of basic science research exist, the surgeon scientist is a phenotype that can be fostered with the dedication and commitment of surgeons to continue to pursue basic science research and active support of departmental leadership.

Keywords: Surgeon scientist, surgery research, basic science research

Introduction

Surgeons participating in basic science research have made enormous contributions to medicine and science extending beyond the surgical field. The discovery of insulin by Frederick Banting,1 the identification of the hormone responsiveness of some cancers by Charles Huggins,2 and Joseph Murray’s work on solid organ transplantation3 are just three, Nobel-winning,4 examples of many. Due to their extensive medical training and intimate hands-on experience with human physiology and pathology, surgeons are in a unique position to develop and pursue basic science research projects that may lead to eventual translation to clinical applications.5 Despite this, the participation of surgeons in basic science research has been declining. The proportion of NIH funding, a commonly used benchmark for scientific success, going to surgery departments has declined 27% between 2007 and 2014 relative to total NIH funding.6 While the number of applications for NIH funding from non-surgical specialties has gone up during this time period, surgeons are submitting fewer grant applications.7 When surgeons do submit grants, their success in obtaining funding is lower than that of other specialties8 and they take longer to obtain it.9 These all contribute to the growing feeling among many surgeons that pursuit of a career encompassing both basic science research as well as a surgical practice is almost impossible.6

The barriers confronting surgeons pursuing basic science research have been evaluated by several groups across surgical disciplines.6,10–14 There are several common barriers that have been identified in these studies: length of training for surgeons, difficulty obtaining funding when competing with full-time non-clinical researchers, need to balance clinical and administrative responsibilities on top of research, lack of mentorship or guidance and the desire for work-life balance. A recent white paper from the Basic Science Committee of the Society of University Surgeons15 suggested a road map for early career faculty interested in pursuing basic science research. They identified four areas that were needed for burgeoning surgeon scientists: a supportive academic environment, initial departmental financial support with specific achievable benchmarks, access to committed mentors and strong social support outside of work. In this paper they provide a generic timeline for the first five years of practice for surgeon scientists.

Research examining surgeons pursuing basic science research has focused on identifying barriers with few studies identifying interventions to overcome them. Interventions presented in the literature are primarily based on recommendations and personal experience rather than qualitative data.15,16 We sought to identify specific interventions that have been successful in fostering surgeon scientist development at the levels of the individual surgeon and the surgery department. We used an initial online survey targeting surgeon scientists and general surgery departmental chairs to develop interview questions and identify respondents who would be willing to share their experiences. Respondents were then interviewed, and qualitative research methods were used to analyze the interviews and identify interventions that promote surgeon scientist development.

Methods

Survey Design and Administration

An online survey was developed to evaluate participants’ perceptions of barriers to surgeons pursuing basic science research. There were two separate question blocks for participants who self-identified as chairs of surgical departments and those who identified as surgeons who had participated in basic science research (henceforth referred to as faculty). The chair question block included queries about what qualifications chairs looked for when recruiting surgeon scientists. The faculty question block included queries about the surgeons’ independent research funding and research experience including how they identified mentors. Participants willing to be contacted for an additional interview were asked to provide an email address for follow up.

Surveys were sent via email to members of the Society of University Surgeons (SUS) (n=502), institutional representatives from the Association for Academic Surgery (n=56), practicing surgeons who were in the top 100 individual recipients of NIH grants to surgical departments (n=64), and United States members of the Society for Surgical Chairs (n=178). To increase the number of responses, participants were encouraged to forward the survey link to other surgeons who they felt would be interested in participating. Additionally, the SUS sent our survey out to their members and did not provide us with a membership roster, there likely was overlap between SUS members and the other groups we sent the survey to. Due to these methods, we are unable to calculate a response rate. Data was collected anonymously (except for participants who volunteered for additional interviews) via Qualtrics17 between August and December of 2017. Survey results were analyzed in STATA.18

The survey and study design were evaluated by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board (IRB) and found to be exempt from IRB approval.

Interviews and Qualitative analysis

The online survey results identified three primary themes that were further explored in interviews: mentorship, funding, and dedicated research time. Separate scripts for faculty and chair interviews were developed (supplemental material). Effort was made to interview faculty across all stages of their careers with the initial goal to interview two or three surgeons at each career stage (<5 years in practice, 5–10 years, 11–20 years, 21–30 years and >30 years) and five departmental chairs. Out of the 43 surgeon faculty participants who volunteered to be interviewed, six had never participated in basic science research as attendings and were excluded from consideration for interviews as we were unsure how their experiences outside of basic science research would be helpful to surgeons pursuing basic science. Twenty-five faculty were contacted and of those the nine who responded were interviewed, two from each career stage except for the 6–10 year category, which had one faculty interviewed. During the interviews, it was discovered that two of the faculty interviewed were former chairs of surgical departments. The data from these two individuals was included in the faculty analysis. The 19 chairs who volunteered for follow up in the initial survey were all contacted and the three who responded were interviewed.

All interviews were conducted by one author via phone or in person based on convenience. Verbal consent was obtained and the interviews were recorded, transcribed and uploaded into NVivo for data management and content analysis.19 Two coders iteratively developed a codebook using inductive content analysis to identify relevant themes including both emergent codes and a priori codes based on our research question and independently analyzed all interviews.20 Theme matrices were tabulated by code and used to generate higher level analysis and identify representative quotes which were evaluated by discussion among all authors.

Results

Online survey

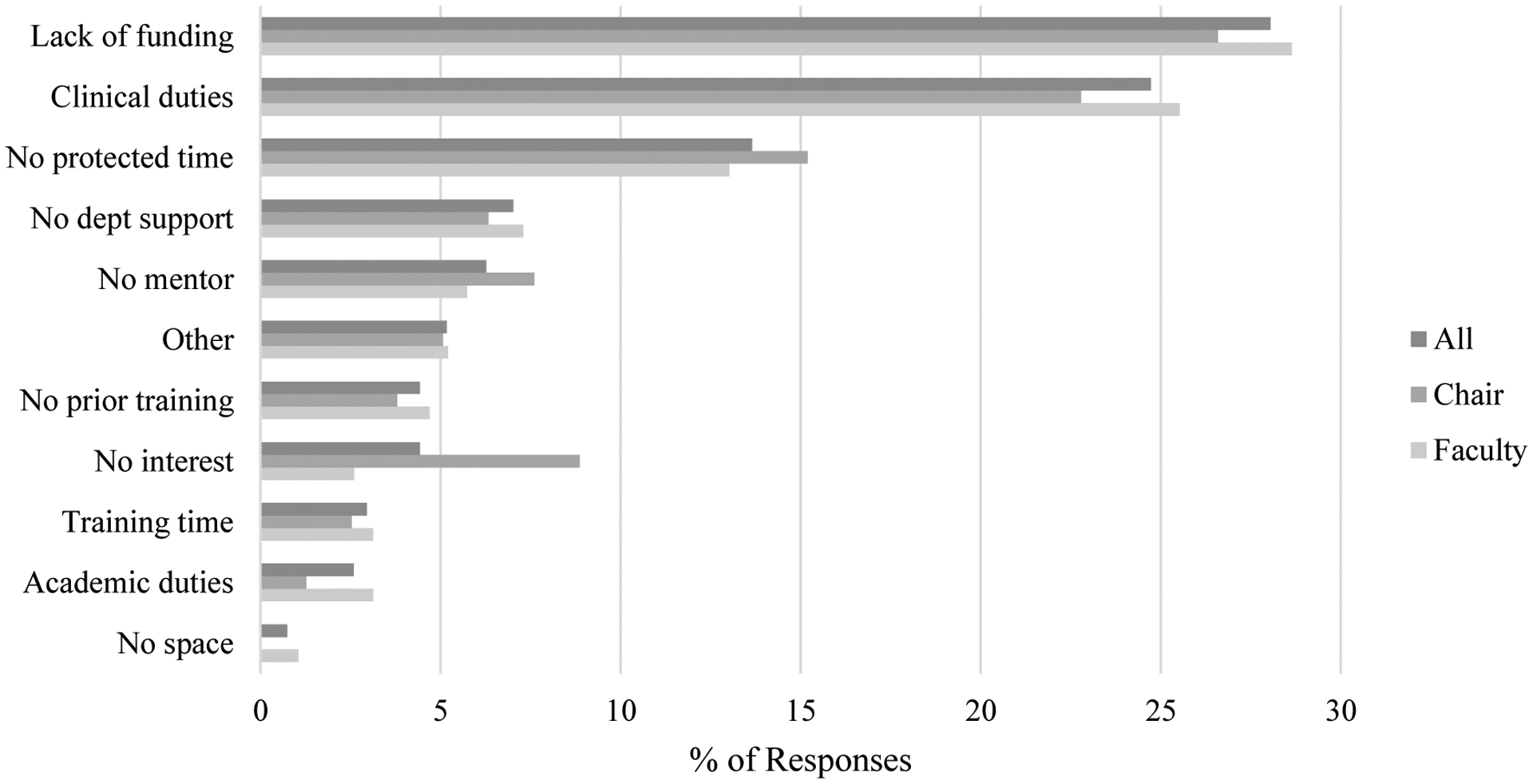

A total of 93 people responded to the online survey. Their demographics are described in Table 1. Almost a third of the respondents (29%) were departmental chairs; the remaining were faculty. The overwhelming majority of all respondents were male (84%) and Caucasian/white (78%) with higher representation of both of these groups in the chair participants (89% and 85% respectively). Faculty respondents came from all career stages from less than five to over 30 years in practice, while all of the chairs had been practicing surgeons for at least 11 years. Participants were located throughout the United States and the majority of faculty and chairs were actively participating in basic science research at the time of survey (74% and 52% respectively). Lack of funding, clinical duties and lack of protected time for research were the top three obstacles to surgeons pursuing basic science by both faculty and chairs (Fig. 1).

Table 1:

Demographics of study participants

| All (n=93) | Faculty (n=66) | Chair (n=27) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age | |||

| ≤40 | 6 (6) | 5 (8) | 0 (0) |

| 41–50 | 29 (30) | 24 (36) | 3 (11) |

| 51–65 | 48 (50) | 28 (42) | 20 (74) |

| >65 | 14 (14) | 9 (14) | 4 (15) |

| Male | 80 (84) | 52 (81) | 24 (89) |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian/White | 74 (78) | 51 (76) | 23 (85) |

| Asian | 15 (16) | 11 (16) | 3 (11) |

| Af Am/Black | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| Hispanic | 3 (3) | 3 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Native American | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Years as faculty | |||

| 0–5 | 6 (6) | 6 (9) | 0 (0) |

| 6–10 | 10 (11) | 9 (14) | 0 (0) |

| 11–20 | 35 (37) | 30 (46) | 5 (19) |

| 21–30 | 27 (29) | 11 (17) | 16 (59) |

| >30 | 16 (17) | 10 (15) | 6 (22) |

| Current location | |||

| West | 12 (13) | 11 (17) | 1 (4) |

| SW | 7 (8) | 4 (6) | 3 (12) |

| Midwest | 29 (32) | 25 (39) | 4 (15) |

| NE | 28 (31) | 15 (23) | 12 (46) |

| SE | 15 (17) | 9 (14) | 6 (23) |

| Basic sci * | 64 (68) | 49 (74) | 14 (52) |

Respondents who were participating in basic science research at the time of survey

Figure 1: Obstacles to basic science research.

Survey participants were asked to select three obstacles they perceived to be the biggest in surgeons pursuing basic science research.

Faculty interviews

All faculty mentioned the importance of surgeon scientists knowing their specific career and scientific goals so that they can know what to look and ask for when pursuing new jobs and mentorship (Table 2). Identifying multiple mentors with proven track records for success in different areas (clinical, scientific, academic) and with success in mentoring others was cited by all as crucial for success as a surgeon scientist: “Everyone has their strengths, and you need to know like who to go to for what if you want a piece of advice.” Once mentors have been identified, having specific goals and timelines for expected accomplishments was important, as one faculty stated “And I also told [my division chair] when I was recruiting to put me on a very short leash. Three years, if I don’t get [extramural funding]…Then I’m done. I’m a pretty good surgeon, I’m happy to operate”. Working to obtain funding early by applying often and using departmental or society grants as steppingstones to larger NIH funding were cited as strategies to overcome the funding obstacle. Utilizing institutional grant writing support (classes, grant offices, etc), and seeking grant feedback from other researchers were also highlighted as ways to improve grant writing skills and funding success: “at least my first probably three or four Rs and K I sent out to other people. Initially people I didn’t know and then to people I did know”. Having support from departmental leaders as well as surgical partners was also cited by faculty as important for scientific success, specifically in being able to limit clinical and administrative responsibilities to have more time to focus on research: “I was fortunate enough to have a group that supports me, and understands that that’s a piece that we wanted to grow and that they took a gamble on me…but hey lets shoulder some of this…clinical duty and still provide me adequate exposure across the academic clinical side.” With regards to the specifics of lab management, many faculty mentioned the benefit of partnering with a lab manager or another researcher to keep up the day to day progress. Finally, planning for failure, learning how to say no to non-essential requests, and having several people working on multiple ongoing projects were given as examples of how to maintain productivity: “I think you need a certain number of people…there’s nothing that guarantees success with grant writing, but guarantees success in terms of productivity is having a certain number of people…When you have one person that if this project fails or if the two projects fail, you’re screwed. Once you pass four or five people the projects can’t all fail and everybody has two or three different projects. There’s a pipeline of things going on”.

Table 2:

Faculty interview responses

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Setting specific goals | “My priority for fellowship was actually science and scientific mentorship…and I said you know, I’m going to take a shift on the clinical front potentially and you know, not necessarily subscribe to a high-volume center that has ten thousand patients a year…And went into a program that was committed towards developing me in some broad way and that was retooling my science toolbox” |

| Identifying mentors | “I took a lot of pain to really kind of

set potential mentors when I chose a lab as a fellow. You kind of learn

some of those lessons to make sure that I had a mentor who was on the

same page as me and, you know, knew what my goals were. And also knew of

my goals which, as a resident, maybe I didn’t as

much.” “my mentor from the research side of things is an endocrinologist. I’m not gonna go to him to talk about a tough potential surgery…neither my research mentor nor my medical mentor may not be the same mentorship that I would want to get as opposed to someone who’s maybe more prominent from a national standpoint in terms of getting involved with national societies, things like that.” |

| Funding | “You’ve gotta get that funding that’s continuing. And just know that if that funding dries up, then that support’s probably gonna dry up too. And especially when you have that skill of being able to generate RVUs to make hospitals money, then it’s very easy for leadership to be…like, “Well, you’re gonna need to chip in and start, you know, generating RVUs and operating two days a week instead of one and having two days in clinic instead of one.”” |

| Departmental support | “there was a high emphasis on academic

productivity and academic recognition that would be equivalent to the

more conventional performance measures of number of cases or revenue

generated. And so that created an opportunity to demonstrate

productivity and success to decision-makers that allowed you to be

academically successful and, you know, share equally in the departmental

rewards, although you may not provide the same clinical service or

educational services that others did. So I think the composite of the

department has to include academic excellence as a essential

element.” “the division chairs that [say], “Listen, we need more coverage than, you know, we need more coverage that we have an outlier clinic. And [Name 1], he just spends two days in the laboratory. He needs to go out there. And to have the department chair say no, [research is their] job.” |

| Day to day running a lab | “you have to partner with a PhD who

will run the laboratory, then I had fellows, research fellows, surgical

fellows, and said, “Here’s my

laboratory.” “You have to plan for failure. You can’t have an expectation that everything you’re gonna do is gonna be successful.” “I think it really is about priorities and scheduling. And a line of just saying, “I can’t do it. I’m not gonna do it. Here’s what I’m gonna do today.” And of course, the higher you get on the hierarchy within the department, the easier that is.” |

Chair interviews

All of the chairs who were interviewed said that in order for surgeon scientists to be successful, supporting basic science research needs to be a stated priority of the department, “We put a certain amount of money into people that we think are good because the department recognizes that having bright, new people in discovery helps everyone”. Having research funding explicitly written into the departmental budget and understanding that clinical revenue from higher volume/more established senior faculty will subsidize junior faculty as they start their research and clinical careers was cited as the primary way that departments funded new surgeon scientists (Table 3). Setting expectations with specific goals and timelines was cited as the first step to success when hiring new faculty. Ensuring good mentorship is critical for scientific success, “I think you can throw all the money, weapons, space, and time at someone, but if they don’t have the right mentor, I don’t think they’ll be successful. So, I work hard to make sure that we have the right mentoring situation for everybody who has an interest in basic science research”. All of the chairs mentioned the importance of having multiple mentors and that they specifically work to have their faculty set up mentoring committees that meet regularly. The chairs periodically check in with these committees to make sure goals are progressing. Using a post-doctoral model where the surgeon is set up within the lab of their primary scientific mentor was mentioned as another way they foster scientific success. Chairs also mentioned the importance of utilizing institutional and departmental resources when it comes to grant writing, “we put a lot of effort into grant development so we have several people that their only job in the department is to help other people write grants. They don’t write the science, but they help them, you know, assemble it and think strategically and … build budgets so that they’re not under-budgeting themselves or something like that.” In addition to meeting with mentorship committees, chairs meet regularly with all surgeon scientists to evaluate progress, “I meet with all new faculty that are being invested in quarterly and make sure that they are not becoming overly clinically busy or underly academically aspirational and redirect as necessary.” Finally, all of the chairs mentioned using a timed trial (an agreed upon amount to time to achieve specific goals) to identify surgeons with not only an interest in basic science research, but an aptitude for it, “And I try to push all of the logistical problems out of their way for a period of about three years to give them the opportunity for success. And if they are unable to demonstrate a modicum of success in that period, it is not out of some problem with logistics or barriers but it’s, it’s just innate capability.”

Table 3:

Chair interview responses

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Funding | “some of that money comes from philanthropy, some of it comes from clinical margins, some of it comes from indirect cost recovery. It can come from lots of different places and for very junior people we know that they’re gonna be in deficit for three years or so. That mid-level people need to be holding their own, but we don’t expect them to give up much and more senior faculty have to be so good that they’re making more than they need.” |

| Expectations | “Everybody that we recruit has to sign some sort of a contract. And really in that we outline how the commitments are and how the time is projected, and it is a two-way commitment that both will be, you know, both have to be obligated to. And again, I think establishing that up front with a realistic expectation works.” |

| Setting up for success | “so we are very explicit about forcing

new faculty to have a mentoring committee, not just a mentor…

they have to organize within three months of arrival [and] that within

six months of arrival they have to have an NIH-styled specific aim page

vetted and have met with their mentoring committee multiple times and

that the committee cannot be people within their own division, you can

have one or two people from the department but it needs to be the

subject matter experts, not just people that are friends.

And…those people on the mentoring committee need to be approved

as being successful researchers themselves.” “So that’s one thing and the junior people when they come here are also assigned very specifically a single mentor, and typically that mentor will be part of that committee. And more- they generally work in their lab or are committed to their lab for two or three years before getting their own space, and you know, as you know a junior faculty, much more often than not, they have a decent background in basic science than typically you know, two or three years since they’ve been in the lab and finishing residency and or fellowship and so I think it makes sense at a lot of levels to sort of embed them in an established lab at the start and as they work toward independence.” |

| Aptitude vs interest in basic science | “I’ve had a couple of faculty that desperately thought that they wanted to be scientists, but when you really got down to it, they really didn’t want to be scientists, they wanted to think of themselves as scientists. But they didn’t want to actually do it.” |

Discussion

The road of a surgeon pursuing basic science is difficult, but it can be traversed. This study provides some guideposts on how to best direct these careers at both the individual faculty and departmental levels. Similar to many other studies,6,10–14 respondents to our survey identified lack of funding, clinical duties, and lack of dedicated research time as the three largest barriers to surgeon scientists. There were some interesting differences in faculty and chairs’ perceived barriers with more chairs feeling that lack of interest was a contributing factor. This may reflect the broader focus of departmental chairs on the overall field of surgical research rather that the individual faculty members’ focus on specific barriers that they have faced individually. However, our interviews with faculty and departmental chairs demonstrated that these barriers are not insurmountable. Both groups mentioned the importance of having specific career goals with timetables that are discussed and agreed upon in advance. Having several mentors for different areas of the surgeon scientist’s career was also cited as being critical for success. Utilizing institutional resources for help in grant writing as well as the standard advice of applying early and often were also mentioned by both groups. Regarding the day to day management of a basic science lab, faculty cited the importance of having someone full time in the lab to keep things on track and making sure that there are multiple ongoing projects at any one time. Learning to say no to outside pressures that are not aligned with one’s research goals, whether they be clinical or administrative, is a skill that surgeons pursuing basic science must develop. The faculty also pointed to the importance of having a supportive department or division in their success. Not surprisingly, the chairs had a higher-level focus of how to keep surgeon scientists progressing along a productive path. This included regular meetings and making sure that clinical and administrative responsibilities are appropriately assigned to give surgeon scientists the time they need to work on research. Finally, all of the chairs mentioned that not all surgeons who want to pursue basic science research will have the aptitude for it. It is the chair’s job to evaluate whether the faculty member is likely to be successful in this career choice and if not, work to redirect faculty to a career path more in line with their strengths.

Setting up specific goals with long and short-term timelines for which progress can be easily assessed were mentioned by almost everyone who was interviewed as being important for success. Prior studies hint at the importance of goals with timelines, but they tend to focus on broad statements such as having your first grant application submitted in the first year on faculty.15,21 This type of goal is non-specific (what type of grant needs to be submitted? Institutional? NIH?) and lacks a roadmap of how to achieve this goal within the desired timeline. An example of specific goals and timelines given by one of the chairs interviewed was making sure that new faculty members have their mentorship committee set up and complete at least one meeting within the first three months and have an NIH-style aims page completed and reviewed by the committee within six months of hire. These goals are all within the broader goal of grant submission within the first year but allow for progress evaluation and interventions at points of difficulty prior to the one-year deadline. Setting specific goals with timelines and writing them down gives junior surgeon scientists a roadmap to highlight what they should be focusing on during the very busy initial startup period while they establish their lab and clinical practice. These initial discussions then set the stage for regular check-ins by the chairs to evaluate progress.

The chairs who were interviewed all mentioned the utility of placing junior surgeon scientists within the lab of their primary scientific mentor in a quasi-post-doctoral fellowship model. Post-doctoral training is traditionally completed by persons who have obtained PhDs and who are continuing their training prior to independent investigator/faculty status, where they work with successful faculty to further develop the researcher’s scientific skills and aid them as they move towards independence. This step is generally required for researchers making the transition between training (graduate school) and independent investigation as junior faculty, yet it is often skipped for surgeon scientists. Embedding early surgeon scientists in the lab of their primary scientific mentor allows the surgeon to receive constant feedback and mentorship with graduated scientific independence and puts them on more even footing with their non-clinical research colleagues who have completed post-doctoral training.

Basic science research requires a significant time investment and a lack of dedicated research time was cited in our study as well as many others6,10–14 as a major barrier to surgeons pursuing basic science. Thoughtful contract negotiation and supportive clinical partners/administration have all been proposed as mechanisms to achieve success.15 To our knowledge, this is the first study to highlight how administration can support surgeon scientists. Every chair who was interviewed stated that one of their most important jobs is to ensure that surgeon scientists have the opportunity to spend a significant amount of time on research – this can mean reducing their call or clinical responsibilities as well as being a gatekeeper for administrative obligations. At the same time, the faculty interviewed in this study did discuss the importance of learning to say no to activities that will not further their scientific or clinical careers. In order to make progress in research while the surgeon scientist is performing their clinical or administrative responsibilities, several faculty members described the importance of having a fulltime lab manager or scientist devoted to keeping experiments and data generation on track. While the initial cost of such a position may seem extravagant given limited start-up funds, every person who mentioned this called it money well spent and felt that it helped them to make progress faster and more efficiently than if they had been trying to manage their lab completely on their own.

In casual conversation and in the literature, difficulty obtaining NIH funding is always listed as one of the major barriers to surgeons or anyone pursuing basic science research.6,7,10–14,22 The general advice given to overcome these barriers is apply early, apply often, and apply for smaller stepping stone grants to move up to R level funding. While this advice is accurate, it is rather generalized and doesn’t focus on specific difficulties surgeon scientists face. In our interviews, faculty and chairs mentioned the importance of utilizing the institutional resources available to surgeon scientists. Specific examples included having grant offices to assist with budgets and taking grant writing courses with the goal of having a K-level NIH style grant proposal completed at the end of the course. Several faculty mentioned the importance of having mentors and collaborators read over all of their grants prior to submission. Often this involves sending grant applications to individuals that the surgeon scientist does not personally know; this is where having engaged scientific mentors and chairs can help to provide these introductions or identify potential grant reviewers. In the end, the surgeon scientist is responsible for writing and submitting grants. However, both faculty and chairs stated that it should be considered part of the chair’s job to make sure that grants are being submitted and progress is being made. If this isn’t happening the chair should find out why and offer assistance as indicated. Finally, young surgeon scientists will be a net loss of revenue to a surgery department until they have established strong clinical and research careers. With that in mind, departmental chairs need to plan for this and have a line item in their budgets to account for how this will be paid for, either by taking revenue from more productive and established surgeons, private endowments, or the like.

This study has several limitations. Due to the nature of the study design, all of the data is self-reported and there may be unappreciated biases inherent in the responses. This study is likely not representative of all surgeon scientist experiences as less than 100 people responded to the online survey and fewer still were interviewed. Additionally, there may be a selection bias in the people who volunteered to participate in this study. While there are important questions related to underrepresented groups in surgery and basic science research, we were unable to evaluate any of them in this study due to small numbers. Our study did not address work-life integration, another large barrier to surgeons pursuing basic science research that has been previously published.6,15 This study was conducted from 2017–2019, and therefore we were unable to make any conclusions about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on funding opportunities or the care giver associated stressors that may contribute to the challenges already present for surgeon scientists. Finally, surgeon scientists beginning their careers need to develop both their research interests as well as their surgical practice, pursuits that both require significant time investments and have steep learning curves. Our survey and interviews did not address how to ensure that enough time and energy is devoted to a faculty’s surgical practice to develop confidence early in a surgeon’s career.

Conclusions

Not everyone who sets out to be a surgeon scientist with independent funding can or will be successful in achieving that goal. However, those that have both the passion and the aptitude for basic science research should be encouraged and fostered. Departmental chairs should work to identify and support these individuals but should also be prepared to help surgeons redirect their career if research is not the appropriate pathway to success. Frequent and open discussions about progress and the surgeon scientists’ overall goals help to keep everyone on track. The path of a surgeon scientist can be challenging, but it is a rewarding path that can be traversed with the appropriate planning and support. We hope that this study provides some concrete examples of ways to approach this career path.

Supplementary Material

Table 4:

Suggestions for promoting surgeons’ pursuit of basic science

|

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [T32 CA090217 and NIH- NIDCD R01-DC004336] and the American College of Surgeons Resident Research Scholarship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Disclosures:

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

This work was presented at the 2018 Clinical Congress in Boston, MA and the 2021 Academic Surgical Congress.

References

- 1.Banting F, Best C. The internal secretion of the pancreas. J Lab Clin Med. 1922;7:251–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huggins C, Hodges CV. Studies on prostatic cancer i. the effect of castration, of estrogen and of androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Res. 1941;1(4):293–297. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.22.4.232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merrill J, Murray J, Harrison J, Guild W. Successful homotransplantations of the human kidney between identical twins. JAMA. 1956;160:277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The official website of the Nobel Prize - NobelPrize.org. https://www.nobelprize.org/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

- 5.More surgeons must start doing basic science. Nature. 2017;544(7651):393–394. doi: 10.1038/544393b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keswani SG, Moles CM, Morowitz M, et al. The future of basic science in academic surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;265(6):1053–1059. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu Y, Edwards BL, Brooks KD, Newhook TE, Slingluff CL. Recent trends in National Institutes of Health funding for surgery: 2003 to 2013. Am J Surg. 2015;209(6):1083–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rangel SJ, Efron B, Moss RL. Recent trends in National Institutes of Health funding of surgical research. In: Annals of Surgery. Vol 236. Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2002:277–287. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200209000-00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hosfield BD, John QE, Seiler KM, Good M, Dunnington GL, Markel TA. Are surgeons behind the scientific eight ball: Delayed acquisition of the NIH K08 mentored career development award. Am J Surg. 2020;219(2):366–371. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.11.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King A, Sharma-Crawford I, Shaaban AF, et al. The pediatric surgeon’s road to research independence: Utility of mentor-based National Institutes of Health grants. J Surg Res. 2013;184(1):66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hait WN. Translating research into clinical practice: Deliberations from the American Association for Cancer Research. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(12):4275–4277. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rangel SJ, Moss RL. Recent trends in the funding and utilization of NIH career development awards by surgical faculty. Surgery. 2004;136(2):232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kodadek LM, Kapadia MR, Changoor NR, et al. Educating the surgeon-scientist: A qualitative study evaluating challenges and barriers toward becoming an academically successful surgeon. Surg (United States). 2016;160(6):1456–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steen EH, Moles CM, Goldstein AM, et al. The Pediatric Surgeon–Scientist: Succeeding in Today’s Academic Environment. J Surg Res. 2019;244:502–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein AM, Blair AB, Keswani SG, et al. A Roadmap for Aspiring Surgeon-Scientists in Today’s Healthcare Environment. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):66–72. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikonomidis JS, Menasché P, Kreisel D, Sellke FW, Woo YJ, Colson YL. Attrition of the cardiothoracic surgeon-scientist: Definition of the problem and remedial strategies. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;158(2):504–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.03.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qualtrics.

- 18.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. 2017.

- 19.NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software. 2019.

- 20.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leeds I, Wick EC. Establishing a Successful Basic Science Research Program in Colon and Rectal Surgery. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2014;27(2):58–64. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1376170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suliburk JW, Kao LS, Kozar RA, Mercer DW. Training future surgical scientists: Realities and recommendations. Ann Surg. 2008;247(5):741–749. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318163d27d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.