Abstract

The increased incidence of nosocomial Legionnaires' disease in two hospitals prompted investigation of possible environmental sources. In the search for an effective DNA-typing technique for use in hospital epidemiology, the performance and convenience of three methods—SfiI macrorestriction analysis (MRA), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), and arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR)—were compared. Twenty-nine outbreak-associated and eight nonassociated strains of Legionella pneumophila with 13 MRA types and subtypes were investigated. These strains comprised isolates from bronchoalveolar lavages, from environmental, patient-related sources, and type strains. All three typing methods detected one predominant genotype associated with the outbreaks in both hospitals. All of them correctly assigned epidemiologically associated, environmental isolates to their respective patient specimens. AP-PCR was the least discriminating and least reproducible technique. In contrast, AFLP was demonstrated as being the method with the best interassay reproducibility (90%) and concordance (94%) in comparison to the genotyping standard of MRA and the epidemiological data. Analysis of AFLP fragments revealed 12 different types and subtypes. Because of its simplicity and reproducibility, AFLP proved to be the most effective technique in outbreak investigation.

Fatality rates of nosocomial pneumonia due to Legionella can be higher than 50%, even when treated appropriately (5). An increased incidence of Legionnaires' disease in a specific setting requires a search for the environmental source. To assess nosocomial infections and their sources, routine methods in hospital epidemiology are to record the length of hospital stay and to determine the serogroup of the Legionella pneumophila isolate. However, determination of the serogroup is of limited value, especially as L. pneumophila serogroup 1 is a common contaminant of the water supply and the most common clinical isolate. Genotyping bacteria has become a helpful tool in hospital epidemiology to establish transmission pathways and to focus expensive prevention measures on the actual reservoir of nosocomial infection.

Macrorestriction analysis (MRA) and serotyping of the subgroups of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 are well-established methods for the typing of L. pneumophila isolates. However, they are often restricted to a few reference laboratories which have the necessary skills, expensive equipment, or access to a collection of monoclonal antibodies. Therefore, numerous PCR-based typing protocols have been introduced, which are based upon random amplification of genomic DNA (36, 37). However, reproducibility of arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) typing methods is reported to be low (18, 29), unless detailed consensus protocols are defined and followed strictly (12). Moreover, they result in complex fingerprinting patterns, which at best have to be analyzed by means of DNA sequencing gels, using automated laser fluorescence analysis systems, and compared unambiguously with specialized software (11, 35). Another principle of PCR-based typing relies on restriction site-directed procedures (17, 34). Yet, the value of genotyping is reduced by the lack of consensus protocols and of commonly accepted criteria for the analysis of the typing data of L. pneumophila for outbreak investigation or even for epidemiological surveillance.

This report describes for the first time the use of genotyping by means of amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) (30) in comparison to the “gold standard” of MRA (24) and a protocol based on the widespread principle of AP-PCR (9) in the reality of ongoing outbreaks in two hospitals. A common, predominant genotype L. pneumophila serogroup 1 found in the isolates of patients and the isolates of patient-related water sources suggests the hospital water supply as being the source of an increased incidence of nosocomial infection. These techniques, which are known to differ in terms of equipment, time, and skill required, were studied in terms of reproducibility, concordance with the epidemiological data, and their simplicity in obtaining and interpreting the DNA fingerprint data. These are evaluation criteria for both categories, i.e., the performance and convenience of typing systems (26).

(Parts of this work were presented at the 14th Meeting of the European Working Group for Legionella Infections, Dresden, Germany, 27 to 29 June 1999 [D. Jonas, D. Hartung, B. Jahn, B. Jansen, H. G. Meyer, and F. D. Daschner, Abstr. 14th Meet. Eur. Working Group Legionella Infect. 1999, abstr. 24, 1999]).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

This study investigated 37 isolates of L. pneumophila serogroup 1, of which 29 were related to Legionella infection at two hospitals, one in Mainz (M), central Germany, and the other in Freiburg (F), south Germany (Table 1). Strains of L. pneumophila were coded with a number preceded by the letter M or F to indicate the hospital from which they originated. Patients were suspected of having contracted a nosocomial infection (i) if they had been hospitalized for more than 2 days before the onset of illness or (ii) if they had been discharged from the hospital and readmitted soon after with signs and symptoms of Legionnaires' disease and (iii) if the L. pneumophila strain's serogroup causing the infection was isolated from the hospital's water supply system. The association of isolates with an outbreak was originally defined on the basis of these epidemiological investigations in the hospital. Additionally, this study included five isolates from community-acquired pneumonia and three type strains of L. pneumophila serogroup 1.

TABLE 1.

Epidemiologic data of the outbreak-associated isolates from patients and drinking water

| Source of isolate | Strain designation | Date of isolation (mo-yr) | Serogroup | Source of materiala | Length of stay before diagnosis (days)b | Epidemiologic linkc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | ||||||

| Hospital M | M2 | 1-96 | 1 | BAL | 9 | |

| M3 | 9-95 | 1 | TS | 8 | ||

| M6 | 9-97 | 1 | BAL | 16 | M8 | |

| M7 | 10-97 | 1 | BAL | 28 | ||

| M15 | 11-97 | 1 | BAL | 47 | ||

| M16 | 2-98 | 1 | BAL | 22 | ||

| M20 | 2-98 | 1 | Sp | —d | M36 | |

| M29 | 11-94 | 1 | RTS | 22 | ||

| M30 | 11-94 | 1 | RTS | 8 | ||

| M31 | 6-94 | 1 | Sp | 13 | ||

| M32 | 8-96 | 1 | BAL | —d | ||

| M33 | 10-92 | 1 | RTS | 15 | ||

| M39 | 3-98 | 1 | BAL | 21 | M41, M42 | |

| M52 | 4-98 | 1 | BAL | 19 | ||

| Hospital F | F131 | 8-98 | 1 | BAL | 35d | F134–F136 |

| F132 | 9-98 | 1 | BAL | 30 | F133 | |

| F141 | 3-99 | 1 | BAL | 60 | F142 | |

| Drinking water | ||||||

| Hospital M | M8 | 9-97 | 1 | Faucet | M6 | |

| M17 | 2-98 | 1 | Shower | |||

| M18 | 2-98 | 1 | Faucet | |||

| M36 | 3-98 | 1 | Shower | M20 | ||

| M41, M42 | 3-98 | 1 | Faucet | M39 | ||

| M44 | 4-98 | 1 | Faucet | |||

| Hospital F | F133 | 10-99 | 1 | Faucet | F132 | |

| F134, F135, F136 | 10-99 | 1 | Faucet | F131 | ||

| F142 | 3-99 | 1 | Faucet | F141 |

Clinical isolates were obtained from bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL), tracheal secretion (TS), sputum (Sp), or undefined respiratory tract specimens (RTS).

—, length of hospital stay before diagnosis could not be stated precisely.

Strain designations refer to organisms from patients and their direct environment.

Patient received continuous treatment as an outpatient before the onset of illness.

Environmental isolates were obtained after concentrating 1 liter of drinking water. After filtration through polycarbonate membranes (0.2-μm pore size), bacteria were detached by sonicating and vortexing the membrane in 30 ml of water and were then pelleted at 4,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was removed until 1 ml remained. Two aliquots of 100 μl were plated onto BCYEα and modified Wadowsky-Yee medium agar (Heipha, Heidelberg, Germany). Legionella organisms from respiratory tract specimens were isolated and cultured on BCYEα agar (Heipha). All specimens were grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 10 days. The genus Legionella was identified by standard microbiological methods and PCR as described elsewhere (15). Species were identified by direct immunofluorescence testing with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-Legionella monoclonal antibodies (Gull Laboratories, Bad Homburg, Germany). Serogroups were determined by agglutination with specific monoclonal rabbit antibodies (21).

MRA of genomic DNAs by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

MRA patterns were obtained by SfiI digestion employing either the GenePath group 5 reagent kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) or self-made reagents produced by modifying a published protocol (24). Briefly, bacteria resuspended in suspension buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 900 mM NaCl, 25 mM EDTA) were embedded in agarose and lysed in lysis buffer (6 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 1 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA) containing 1 mg of lysozyme (Boehringer Mannheim) per ml, 0.06 mg of DNase-free RNase A (Sigma) per ml, 0.5% Brij 58, 0.2% deoxycholate, and 0.5% N-laurosylsarkosine for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequently, proteins were removed in proteinase K buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 0.5 M EDTA) containing 2 mg of proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim) per ml and 1% N-laurosylsarkosine. After extensive washing and equilibration in SfiI buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl), DNA in each plug was restricted with 25 U of SfiI (Boehringer Mannheim) for 16 h at 50°C and overlaid with 250 μl of mineral oil (Sigma).

Plugs containing cleaved DNA were loaded into slots of a 1% agarose gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. Lambda concatemers (Bio-Rad) were used as size markers. Separation was accomplished with the contour-clamped homogeneous electric field (CHEF DR II) system (Bio-Rad). Running conditions were 200 V for 19.3 h at 14°C with switch times of 5.3 s (initial) and 49.9 s (final). After ethidium bromide staining, the gels were photographed with a UV light source.

The macrorestriction fragments of all 37 strains were compared visually. A new PFGE type was assigned a capital letter if the pattern differed by more than three bands. If the difference was three bands or less, then a numerical suffix was allocated. To give a conclusive picture of the different macrorestriction patterns, a gel displaying all 13 different PFGE types and subtypes was photographed. This image was recorded with a Scan IIP (Hewlett-Packard Co., Vancouver, Wash.) and analyzed by means of GelCompar software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). A similarity matrix was created by using the band-based Dice similarity coefficient. The unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages was used to cluster the strains on the basis of the SfiI macrorestriction patterns.

AP-PCR.

Colonies (three to five) from a freshly grown culture were resuspended in 100 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1 mM EDTA) in a microcentrifuge tube and incubated for 15 min at 95°C. After chilling on ice, bacterial debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 20 s. The supernatant was transferred into a fresh microcentrifuge tube.

The AP-PCR was essentially performed as described previously (9, 22). The M13 primer (5′ TTA TGT AAA ACG ACG GCC AGT 3′) used for typing was fluorescently labelled with Cy-5 during manufacture (Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 μl, with 1 μl of the bacterial lysate being added to a PCR mix comprising 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 3 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Pharmacia Biotech), and 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim). The PCR comprised 45 cycles of 60 s at 94°C, 60 s at 36°C, and 120 s at 72°C and a final extension step at 72°C for 2 min. PCR products were detected by analysis of a 1.2-μl portion on an ALF Express DNA Sequencer (Pharmacia) as described previously (12).

Fingerprints in the range of 120 to 1,000 nucleotides (nt) were analyzed by means of GelCompar software. After conversion, normalization, and background subtraction with mathematical algorithms, the degree of similarity between fingerprints was calculated with the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient. Cluster analysis was performed with the unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages.

AFLP.

Typing of Legionella isolates by AFLP was performed according to a previously described protocol (30) except that Cy-5 fluorescently labeled PstI-G primers were used for DNA amplification. Briefly, purified DNA was prepared by digesting half a loop of bacteria resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM EDTA with 50 μg of proteinase K per ml and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and subsequent extraction of potential inhibitors with 1% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide, chloroform, and phenol-chloroform-isoamylalcohol. After ethanol precipitation, DNA was resolved in 20 μl of 1 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 0.1 mM EDTA.

Restriction and ligation was performed simultaneously in 20 μl of ligase buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 10 mM magnesium acetate, 50 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM ATP) containing 2 μl of the DNA, 0.2 μg of each adapter oligonucleotide (5′-CTC GTA GAC TGC GTA CAT GCA and 5′-TGT ACG CAG TCT AC), 20 U of PstI, and 1 U of T4 DNA ligase (both from Boehringer Mannheim). After incubation for 3 h at 37°C, ammonium acetate was added to a final molarity of 2.5 M. Ligated DNA was selectively precipitated with 1 volume of ice-cold 98% ethanol for 5 min at ambient temperature. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g and washing with 75% ethanol, the dried pellet was dissolved in 20 μl of 1 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 0.1 mM EDTA. Before PCR, this DNA was diluted 1:100 with 1 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0).

The amplification reaction was performed in a final volume of 25 μl containing 1 μl of the diluted DNA, 75 ng of the Cy-5 fluorescently labeled PstI-G primer (5′-GAC TGC GTA CAT GCA GG), 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (both from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 50 mM KCl, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim). The PCR comprised 33 cycles of 60 s at 94°C, 60 s at 60°C, and 150 s at 72°C and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min.

Detection of the fluorescent AFLP (fAFLP) products was performed by automated laser fluorescence analysis as described above for the AP-PCR. The lengths of different PCR products smaller than 1,000 nt in size were determined by means of the Fragment Manager software V1.2 (Pharmacia). In a second approach, PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (1% agarose, 1× TBE buffer, 1 μg of ethidium bromide/ml, 140 V for 3 h). Fragment lengths in the range of 500 to 1,636 bp were calculated by determination of the electrophoretic mobility in comparison to fragments of strains which were previously exactly determined by sequencing gels and in comparison to the size marker X (Boehringer Mannheim). Each isolate was characterized by the presence or absence of defined fragments in a fragment size table, and the number of band differences was counted. A new AFLP type was assigned a lowercase letter if the pattern differed by more than one band. If the pattern differed by one band, a numerical suffix was allocated to designate a subtype.

RESULTS

Epidemiology of outbreaks.

At hospital M, reexamination of clinical microbiology reports revealed repeated nosocomial infection between 1992 and 1998. Of 14 patients, eight had been hospitalized for at least 2 weeks prior to diagnosis (Table 1). At hospital F, an increase in the incidence of Legionnaires' disease was observed over a period of half a year. L. pneumophila serogroup 1 organisms were found in patients and their direct drinking water supply. As indicated in Table 1, in the case of three infections, the length of hospital stay before diagnosis could not be stated precisely. Two patients had been treated daily as outpatients at the hospital before onset of illness (M20, M32). Another patient (F131), though hospitalized for more than a month, spent every second night at a boardinghouse outside the hospital. Table 1 lists 21 strains isolated during the ongoing outbreak in hospital M and eight strains related to the increased incidence observed over 7 months at hospital F. In five cases, isolates of serogroup 1 were obtained directly from the faucets or showers in sickrooms soon after the onset of illness.

Patients with nosocomial Legionnaires' disease were either transplant recipients or had underlying diseases, such as myasthenia gravis, neurofibromatosis, forms of leukemia, or nonhematologic malignancies. Patients with community-acquired pneumonia had predisposing factors, such as leukemia, smoking, diabetes mellitus, or advanced age. The occurrence of nosocomial legionellosis ceased at both hospitals after 0.2-μm-pore-size filter units were installed on the faucets in rooms occupied by patients at risk.

Additionally, eight isolates of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 which were not associated with the outbreaks were included to cover a greater number of different genotypes in this study. These consisted of three type strains and five isolates from patients with community-acquired pneumonia (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Molecular characterization of the clinical isolates and reference strainsa

| Strain designation(s) of outbreak-related strains | SfiI MRA | AP-PCR | fAFLP | AFLP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outbreak M | ||||

| M2, M3, M6, M7, M8, M15, M17, M29, M30, M31, M32, M39, M41, M42, M52 | A | 1 | 1 | a1 |

| M16, M18, M44 | C | 2 | 2 | b1 |

| M20, M36 | D | 3 | 3 | c1 |

| M33 | E1 | 2 | 4 | d1 |

| Outbreak F | ||||

| F131 | F | 2 | 5 | e |

| F132, F133, F134, F135, F136 | B1 | 1 | 1 | a2 |

| F141, F142 | B2 | 1 | 1 | a2 |

| Community-acquired cases | ||||

| M1 | G | 6 | 6 | f |

| M5 | E2 | 5 | 7 | d2 |

| F64 | E3 | 4 | 8 | d3 |

| F65 | E4 | 4 | 9 | g |

| F137 | H | 2 | 2 | b2 |

| Type strainsb | ||||

| ATCC 33152 | I | 7 | 3 | c2 |

| RIVM 83-147 | A | 1 | 1 | a1 |

| ATCC 43111 | E1 | 2 | 4 | d1 |

SfiI MRA was performed by PFGE. AP-PCR and fAFLP were performed with DNA sequencing gels, and AFLP was performed with agarose gels.

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; RIVM, Rijkinstituut voor volksgezondheid en milieuhygiene.

Macrorestriction analysis.

The SfiI macrorestriction analysis of the predominant clones causing the outbreaks in the two hospitals are shown in Fig. 1. Remarkably, though some 300 km apart, isolates from the two hospitals showed some degree of similarity. There were two-fragment differences between the various isolates from hospital F. Comparison of these prevailing types, B1 and B2, with the predominant type A from hospital M showed only four and six different bands, respectively.

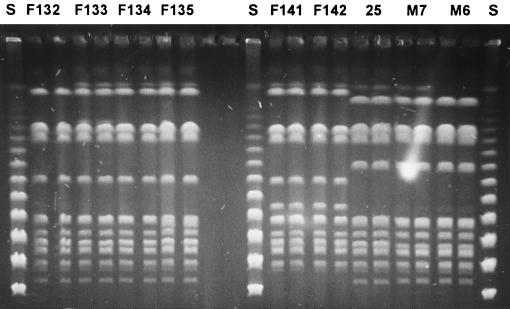

FIG. 1.

PFGE of the predominant strains in both hospitals. Numbers refer to strains described in Table 1. Each isolate was run in duplicate in neighboring lanes. Lane S, 48.5-kb bacteriophage lambda concatemers ladder; lane 25, RIVM 83-147.

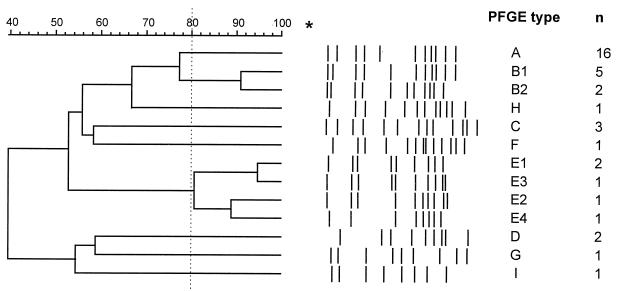

Analysis of all 37 isolates revealed 13 different PFGE types and subtypes (Table 2). Figure 2 depicts conclusively and schematically all the different PFGE types. The patterns of the same type showed 80 to 100% similarity.

FIG. 2.

Classification and schematic representation of the 13 different SfiI patterns obtained from the 37 strains included this study. The asterisk indicates the top of the gel. Numbers (n) of isolates found with each PFGE type are on the right.

AP-PCR typing.

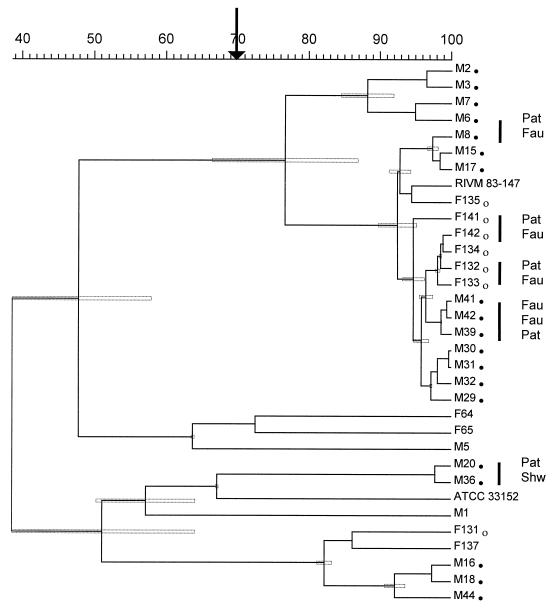

Typing results for 33 strains by means of AP-PCR cluster analysis are shown in Fig. 3. Cophenetic correlation of the dendrogram was 95%. All five epidemiologically linked isolates from patients and their immediate environment had a similarity of >75%. All isolates from both outbreaks with the predominant PFGE types A and B were grouped together in a cluster. A similarity of ≥77% ± 10% (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) was measured.

FIG. 3.

Dendrogram of cluster analysis of 33 isolates typed by AP-PCR. The dendrogram is based on Pearson product moment correlation. Strains are designated with the code given in Table 2. Strains associated with the outbreaks of nosocomial legionellosis in hospital M (●) and hospital F (○) are marked. Isolates of the same genotype, which were epidemiologically linked, i.e., organisms from patients (Pat) and their immediate environment (such as faucets [Fau] or showers [Shw]), are indicated by vertical bars at the right site of the dendrogram. The arrow denotes the cutting level for separation clusters and single strains. Stippled boxes in the dendrogram indicate SDs with respect to the similarity matrix for every branch of the dendrogram.

From this, it was deduced that a similarity of less than 70% was indicative of different genotypes. In this way, seven different types were determined (Table 2).

Due to the limited number of geltracks, the remaining four strains from the strain collection were investigated in a different experiment together with strains representing all of the seven different AP-PCR genotypes (data not shown). The remaining strains M33 and ATCC 43111 were grouped in the same cluster as strain M18 (type 2), and strains M52 and F136 were in the cluster with RIVM 83-147 (type 1).

Interassay reproducibility of PCR-based typing.

All AP-PCR experiments were performed with one lot of reagents. However, the interassay reproducibility of AP-PCR proved to be low. Fingerprints of the same strains generated in four independent experiments were compared for similarity (Table 3). The Pearson correlation coefficient might be as low as 57 or 54% (ATCC 33152 and RIVM 83-147, respectively), which is below the cutoff value indicating different AP-PCR genotypes. This actually implies that a comparison of new isolates with previous ones requires a reanalysis of all isolates—the new ones and the strains already typed—within a single experiment. In contrast, reanalysis experiments with AFLP demonstrated an interassay reproducibility of at least 84% (ATCC 33152), a value also useful for discrimination between related and unrelated strains.

TABLE 3.

Interassay reproducibility of PCR-based typing methods

| Strain | Mean correlation coefficients ± SDa

|

|

|---|---|---|

| AP-PCR (n = 4) | AFLP (n = 3) | |

| M1 | 80.8% ± 4.5% | 90.6% ± 1.0% |

| ATCC 33152 | 69.2% ± 13.6% | 91.3% ± 5.4% |

| RIVM 83-147 | 75.5% ± 12.3% | 94.7% ± 1.3% |

| M31 | 81.2% ± 10.3% | 90.6% ± 5.0% |

Average similarities were expressed in percentages as the means of Pearson correlation coefficients obtained by typing the same strain in n independent experiments.

Fluorescent AFLP typing using ALF Express.

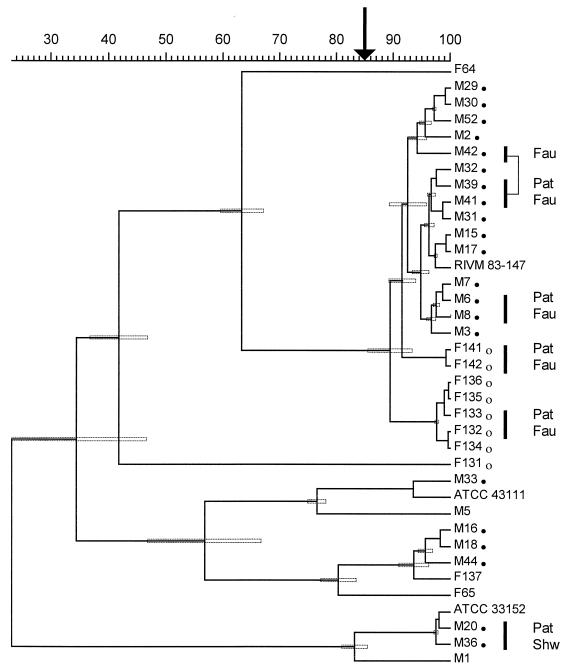

All strains were typed by means of fAFLP and analyzed in the same manner as the AP-PCR fingerprints (Fig. 4). Due to the high interassay reproducibility, data from two gels comprising all the 37 isolates were combined for a single cluster analysis. Cophenetic correlation of the dendrogram was 97%. All five epidemiologically related isolates from patients and their direct drinking water source had a similarity of >92%. The isolates from outbreak M with PFGE type A were grouped in a cluster with a similarity of >90%. Yet, these results were not statistically significant, as indicated by the error bars (Fig. 4). Isolates from the two outbreaks with the predominant PFGE type A and B were grouped in a cluster. A similarity of ≥89% ± 4% (mean ± SD) was measured. On this basis, a cutoff of 85% similarity was taken to discriminate nine different genotypes by cluster analysis (Table 2).

FIG. 4.

Fluorescent AFLP analysis of all isolates of L. pneumophila investigated by means of automated laser fluorescence analysis. Strains are designated with the code given in Table 2. For further details, see the legend of Fig. 3.

AFLP typing by means of agarose gel.

Since the protocol of AFLP typing by means of agarose gel employs just one restriction enzyme, the fingerprints are less complex. Therefore, it was investigated next whether similar typing results might be obtained by the use of ordinary agarose gel electrophoresis available in any PCR laboratory.

The AFLP products were separated on agarose gels. The fragment sizes, in the range 500 to 1,636 bp, were estimated in comparison with data defined by the previous sequencer-based analysis (500 to 1,000 nt) and in comparison to DNA size standards (1,000 to 1,636 bp). A fragment size table representing all the different types of fingerprints is shown in Table 4. These data proved to be at least as useful as the even more convenient computer-based analysis of fAFLP fingerprints. Moreover, additional differences within three fAFLP types could be demonstrated, since fragments larger than 1,000 bp in size, which cannot be separated under the denaturing sequencing gel conditions used, were taken into account.

TABLE 4.

Polymorphism of AFLP fingerprints resolved on agarose gels

| Fragment size (bp)a | Fragment typeb

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | a2 | b1 | b2 | c1 | c2 | d1 | d2 | d3 | e | f | g | |

| 1,635 | + | |||||||||||

| 1,550 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 1,480 | + | |||||||||||

| 1,415 | + | |||||||||||

| 1,350 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| 1,200 | + | |||||||||||

| 1,150 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| 920 | + | + | + | |||||||||

| 795 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 775 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| 720 | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| 710 | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| 575 | + | + | + | |||||||||

| 536 | + | + | + | |||||||||

Size of fragments smaller than 1,000 bp were taken as calculated by the Fragment Manager software from the respective automated laser fluorescence analysis data. Fragments larger than 1,000 bp in size were estimated in comparison to the electrophoretic mobility of DNA size markers.

The presence of fragments of distinct size is shown. +, a fragment characteristically present in that AFLP profile.

There were minor differences in MRA between the predominant types in hospital F (types B1, B2) and hospital M (type A), which were mirrored by one additional PCR fragment in AFLP type a2 compared to the number in type a1. As far as concordance between this technique and MRA is concerned, only two isolates (F141, F142) of the PFGE subtype B2 were indistinguishable from the strains of subtype B1.

DISCUSSION

The increased incidence of Legionnaires' disease required clarification of a possible nosocomial mode of transmission. The length of hospital stay before onset of clinical signs or even diagnosis could not prove a hospital-acquired infection in all the cases presented because the incubation period varies from 2 to 10 days (38) and three patients were not hospitalized continuously. In the case of one patient (F131), no corresponding environmental isolate could be found, though all conceivable water sources (F134, F135, F136) were investigated. It might be that the patient acquired the infectious strain outside the hospital during overnight stays in the nearby boardinghouse. Water samples outside the hospital were not investigated. However, in the case of two other patients treated continuously as outpatients (M20, M32), a clear link to the hospital water supply could be shown.

The predominance of one genotype in patient specimens seemed to suggest transmission from common sources. Since L. pneumophila is also ubiquitously found in water supplies without history of any cases, the actual causative, infectious reservoir should be demonstrated by means of typing methods to enforce allocation of financial resources for prevention measures.

The importance of this issue in hospital epidemiology is reflected by the multitude of techniques proposed for the last 15 years, such as plasmid typing (19), serotyping (14), multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (25), or different restriction enzyme-based methods, such as restriction fragment length polymorphism (33), Southern hybridization (23), ribotyping (1), and MRA by means of PFGE (20, 24). In general, the latter is considered to be a gold standard, especially when combined with serotyping. However, the use of MRA is confined to specialized centers, because expensive equipment and special skills are required. Monoclonal antibodies for serotyping are not available commercially and antibody-producing hybridoma cell lines are maintained in only a few reference centers.

Therefore, multiple, simple PCR-based approaches for the typing of Legionella organisms have been proposed, such as AP-PCR (2, 9, 10, 22) or rep-PCR (7, 31).

In this study, we report the suitability of applying two variably demanding PCR-based DNA typing techniques and MRA in hospital epidemiology during two nosocomial outbreaks of Legionnaires' disease. Working on the premise that an outbreak constitutes at least two cases of nosocomial infection occurring at one institution within a half-year period, we found one outbreak at hospital M involving 11 patients with prevailing PFGE type A and one outbreak at hospital F involving two patients with the predominant subtypes B1 and B2. All three genotyping methods revealed the predominant genotypes in both hospitals.

In five cases, isolates were obtained from the direct faucets or the shower in sickrooms soon after the onset of illness. In these cases all three genotyping methods established an unambiguous link between the strains isolated from the patients and the ones isolated from their immediate drinking water supply.

Use of SfiI MRA resulted in the largest number of genotypes. This was the only technique to reveal minor genetic differences between isolates of outbreak F. However, even employment of this expensive equipment was found to have limitations. One clinical isolate (M33) could not be distinguished from the Bellingham I type strain (ATCC 43111), even by MRA. Yet, it is unreasonable to assume an epidemiologic relation between these two strains. Several isolates showed a banding pattern similar to that of type E, though they originated from entirely different European regions, such as Crete (F64) and central (M5) and southern (F65) Germany. Thus, even typing by means of MRA can suggest epidemiologic links erroneously. Apart from the technical demands and the workload, an unambiguous, visual interpretation and comparison of a larger number of PFGE patterns is rather tedious.

On the other hand, AP-PCR, the simplest technique employed here, is suitable for processing isolates within a short time, particularly if the fingerprints are resolved by means of automated laser fluorescence analysis and the primarily digitized data are interpreted with the help of computer programs. However, only seven different genotypes were distinguished here. As reported by others (18, 29), reproducibility of AP-PCR is low, which renders comparison of new fingerprints in ongoing or repeated outbreaks with previous ones more difficult. Typing data cannot be stored in a database for future comparison. All previous strains representing the different genotypes have to be reanalyzed together with the new isolate in the same experiment. Therefore, the number of isolates which can be analyzed ultimately depends on the number of gel lanes available.

AP-PCR experiments in this report were not performed using strictly standardized manufactured reagents (e.g., Ready-To-Go RAPD beads supplied by Pharmacia). If they had been, reproducibility might have improved, but it was not considered prudent to rely on a continuous supply of special PCR reagents and polyacrylamide formulations from one manufacturer. Even more demanding typing approaches have shown the limitations of this general idea (32). Moreover, AP-PCR patterns are too complex to be described in detail and to be exchanged between different laboratories without the aid of special software. This sort of exchange may be of interest, e.g., in travel-associated legionellosis (16).

In contrast, the more recently introduced technique of AFLP features a high degree of reproducibility (13). This study proved AFLP to have an interassay reproducibility of 90%, which is high enough for comparing fingerprints from different experiments at different times. This is particularly effective in cases of continuous or repeated outbreaks when the fingerprints of new isolates can be compared with previous ones and then deposited in fingerprint pattern databases. Therefore, this method is suitable as a library typing system (27). An epidemiological surveillance of environmental spread and association with disease might show that strains with a certain genotype are more often associated with disease. In principle, this was already suggested by serotyping results 1 decade ago (4).

The AFLP technique, as described initially, includes two restriction enzymes and results in complex patterns of 30 to 50 different fragment sizes (34). Unlike these fingerprints, which have to be resolved by means of sequencing gels, less complex patterns are obtained by AFLP protocols employing just one restriction enzyme, which can be analyzed by simple agarose gels. This has been demonstrated for Chlamydia psittaci, Helicobacter pylori, and L. pneumophila (3, 8, 30).

In a basic approach in this study, AFLP fragments were also analyzed by means of agarose gels. Accordingly, it was possible to discriminate 12 types and subtypes; 35 of 37 isolates (94%) were typed in concordance with MRA.

In interpreting MRA patterns, it is assumed that one genetic difference will result in three PFGE fragment differences (28). Similarly, in terms of this AFLP method we assumed just one difference in PCR fragments because rearranged PstI fragments would most probably be too large for amplification by PCR. Therefore, isolates with one fragment difference were designated as subtypes. Interestingly, the fragment differences in MRA between isolates of outbreak F and M were mirrored by just one additional fragment in the outbreak F strains 1,415 bp in size. Patterns could even be interpreted in a simple fragment size table. They might be communicated between laboratories, provided fragment length can be precisely defined. This could be achieved by means of a small panel of well-chosen type strains representing most, if not all, AFLP fragment sizes.

Yet, analysis of AFLP patterns by means of automated laser fluorescence provides a more accurate definition of fragment sizes, an improved resolution of similarly large fragments, e.g., 710 and 720 bp, and a superior detection of smaller fragments, which are only faintly stained with ethidium bromide on agarose gels.

During investigation of different ongoing outbreaks of nosocomial Legionnaires' disease, we demonstrated that in terms of technical demands, reproducibility, and simplicity of the patterns, AFLP is the most effective typing method for application in standard hospital epidemiology laboratories. These findings correspond to a recently presented study employing a European strain collection (6). Using nosocomial Legionella infections as an example, this report once again demonstrates the impact of appropriate molecular typing in hospital infection control and prevention measures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to T. Harrison and N. Fry, Respiratory and Systemic Infection Laboratory, PHLS Central Public Health Laboratory, London, United Kingdom, and to C. Valsangiacomo, Laboratorio Cantonale, Lugano, Switzerland.

Parts of this study were supported by the Robert Koch-Institut, Berlin, Germany.

We thank Deborah Lawrie-Blum for assistance with the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bangsborg J M, Gerner-Smidt P, Colding H, Fiehn N E, Bruun B, Hoiby N. Restriction fragment length polymorphism of rRNA genes for molecular typing of members of the family Legionellaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:402–406. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.402-406.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bansal N S, McDonell F. Identification and DNA fingerprinting of Legionella strains by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2310–2314. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2310-2314.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boumedine K S, Rodolakis A. AFLP allows the identification of genomic markers of ruminant Chlamydia psittaci strains useful for typing and epidemiological studies. Res Microbiol. 1998;149:735–744. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)80020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dournon E, Bibb W F, Rajagopalan P, Desplaces N, McKinney R M. Monoclonal antibody reactivity as a virulence marker for Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 strains. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:496–501. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelstein P H. Antimicrobial chemotherapy for Legionnaires' disease: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(Suppl. 3):5265–5276. doi: 10.1093/clind/21.supplement_3.s265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fry N K, Alexion-Daniel S, Bangsborg J M, Bernander S, Castellani-Pastoris M, Etienne J, Forsblom B, Gaia V, Helbig J H, Lindsay D, Luck P C, Pelaz C, Uldum S A, Harrison T G. A multicenter evaluation of genotypic methods for epidemiologic typing of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1: results of a pan-European study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1999;5:462–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1999.tb00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Georghiou P R, Doggett A M, Kielhofner M A, Stout J E, Watson D A, Lupski J R, Hamill R J. Molecular fingerprinting of Legionella species by repetitive element PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2989–2994. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2989-2994.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson J R, Slater E, Xerry J, Tompkins D S, Owen R J. Use of an amplified-fragment length polymorphism technique to fingerprint and differentiate isolates of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2580–2585. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2580-2585.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez-Lus P, Fields B S, Benson R F, Martin W T, O'Connor S P, Black C M. Comparison of arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction, ribotyping, and monoclonal antibody analysis for subtyping Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1940–1942. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1940-1942.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grattard F, Berthelot P, Reyrolle M, Ros A, Etienne J, Pozzetto B. Molecular typing of nosocomial strains of Legionella pneumophila by arbitrarily primed PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1595–1598. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1595-1598.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grundmann H, Schneider C, Tichy H V, Simon R, Klare I, Hartung D, Daschner F D. Automated laser fluorescence analysis of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA: a rapid method for investigating nosocomial transmission of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:446–451. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-6-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grundmann H J, Towner K J, Dijkshoorn L, Gerner-Smidt P, Maher M, Seifert H, Vaneechoutte M. Multicenter study using standardized protocols and reagents for evaluation of reproducibility of PCR-based fingerprinting of Acinetobacter spp. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3071–3077. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3071-3077.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janssen P, Coopman R, Huys G, Swings J, Bleeker M, Vos P, Zabeau M, Kersters K. Evaluation of the DNA fingerprinting method AFLP as a new tool in bacterial taxonomy. Microbiology. 1996;142:1881–1893. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joly J R, McKinney R M, Tobin J O, Bibb W F, Watkins I D, Ramsay D. Development of a standardized subgrouping scheme for Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 using monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23:768–771. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.4.768-771.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonas D, Rosenbaum A, Weyrich S, Bhakdi S. Enzyme-linked immunoassay for detection of PCR-amplified DNA of legionellae in bronchoalveolar fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1247–1252. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1247-1252.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph C, Morgan D, Birtles R, Pelaz C, Martin-Bourgon C, Black M, Garcia-Sanchez I, Griffin M, Bornstein N, Bartlett C. An international investigation of an outbreak of Legionnaires' disease among UK and French tourists. Eur J Epidemiol. 1996;12:215–219. doi: 10.1007/BF00145408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazurek G H, Reddy V, Marston B J, Haas W H, Crawford J T. DNA fingerprinting by infrequent-restriction-site amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2386–2390. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2386-2390.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meunier J R, Grimont P A. Factors affecting reproducibility of random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:373–379. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nolte F S, Conlin C A, Roisin A J, Redmond S R. Plasmids as epidemiological markers in nosocomial Legionnaires' disease. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:251–256. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ott M, Bender L, Marre R, Hacker J. Pulsed field electrophoresis of genomic restriction fragments for the detection of nosocomial Legionella pneumophila in hospital water supplies. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:813–815. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.4.813-815.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pietsch M. Ph.D. thesis. Greifswald, Germany: Ernst Moritz Arndt-Universität Greifswald; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pruckler J M, Mermel L A, Benson R F, Giorgio C, Cassiday P K, Breiman R F, Whitney C G, Fields B S. Comparison of Legionella pneumophila isolates by arbitrarily primed PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: analysis from seven epidemic investigations. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2872–2875. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.2872-2875.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saunders N A, Harrison T G, Haththotuwa A, Kachwalla N, Taylor A G. A method for typing strains of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 by analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphisms. J Med Microbiol. 1990;31:45–55. doi: 10.1099/00222615-31-1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoonmaker D, Heimberger T, Birkhead G. Comparison of ribotyping and restriction enzyme analysis using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for distinguishing Legionella pneumophila isolates obtained during a nosocomial outbreak. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1491–1498. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1491-1498.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selander R K, McKinney R M, Whittam T S, Bibb W F, Brenner D J, Nolte F S, Pattison P E. Genetic structure of populations of Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:1021–1037. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.1021-1037.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Struelens M J, Bauernfeind A, Van Belkum A, Blanc D, Cookson B D, Dijkshoorn L, El Solh N, Etienne J, Garaizar J, Gerner-Smidt P, Legakis N, de Lencastre H, Nicolas M H, Pitt T L, Romling U, Rosdahl V, Witte W. Consensus guidelines for appropriate use and evaluation of microbial epidemiologic typing systems. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996;2:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1996.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Struelens M J, De Gheldre Y, Deplano A. Comparative and library epidemiological typing systems: outbreak investigations versus surveillance systems. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1998;19:565–569. doi: 10.1086/647874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tyler K D, Wang G, Tyler S D, Johnson W M. Factors affecting reliability and reproducibility of amplification-based DNA fingerprinting of representative bacterial pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:339–346. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.339-346.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valsangiacomo C, Baggi F, Gaia V, Balmelli T, Peduzzi R, Piffaretti J C. Use of amplified fragment length polymorphism in molecular typing of Legionella pneumophila and application to epidemiological studies. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1716–1719. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1716-1719.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Belkum A, Struelens M, Quint W. Typing of Legionella pneumophila strains by polymerase chain reaction-mediated DNA fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2198–2200. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2198-2200.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Belkum A, van Leeuwen W, Kaufmann M E, Cookson B, Forey F, Etienne J, Goering R, Tenover F, Steward C, O'Brien F, Grubb W, Tassios P, Legakis N, Morvan A, El Solh N, de Ryck R, Struelens M, Salmenlinna S, Vuopio-Varkila J, Kooistra M, Talens A, Witte W, Verbrugh H. Assessment of resolution and intercenter reproducibility of results of genotyping Staphylococcus aureus by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of SmaI macrorestriction fragments: a multicenter study. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1653–1659. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1653-1659.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Ketel R J, ter Schegget J, Zanen H C. Molecular epidemiology of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:362–364. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.3.362-364.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vos P, Hogers R, Bleeker M, Reijans M, van de Lee T, Hornes M, Frijters A, Pot J, Peleman J, Kuiper M. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Webster C A, Towner K J, Humphreys H, Ehrenstein B, Hartung D, Grundmann H. Comparison of rapid automated laser fluorescence analysis of DNA fingerprints with four other computer-assisted approaches for studying relationships between Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:185–194. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-3-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welsh J, McClelland M. Fingerprinting genomes using PCR with arbitrary primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7213–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams J G, Kubelik A R, Livak K J, Rafalski J A, Tingey S V. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6531–6535. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu V L. Legionella pneumophila (Legionnaires' disease) In: Mandell G L, Bennet J E, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious disease. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. pp. 2087–2097. [Google Scholar]