Abstract

Objectives

To examine the mediation role of self-care between stress and psychological well-being in the general population of four countries and to assess the impact of sociodemographic variables on this relationship.

Design

Cross-sectional, online survey.

Participants

A stratified sample of confined general population (N=1082) from four Ibero-American countries—Chile (n=261), Colombia (n=268), Ecuador (n=282) and Spain (n=271)—balanced by age and gender.

Primary outcomes measures

Sociodemographic information (age, gender, country, education and income level), information related to COVID-19 lockdown (number of days in quarantine, number of people with whom the individuals live, absence/presence of adults and minors in charge and attitude towards the search of information related to COVID-19), Perceived Stress Scale-10, Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale-29 and Self-Care Activities Screening Scale-14.

Results

Self-care partially mediates the relationship between stress and well-being during COVID-19 confinement in the general population in the total sample (F (3,1078)=370.01, p<0.001, R2=0.507) and in each country. On the other hand, among the evaluated sociodemographic variables, only age affects this relationship.

Conclusion

The results have broad implications for public health, highlighting the importance of promoting people’s active role in their own care and health behaviour to improve psychological well-being if stress management and social determinants of health are jointly addressed first. The present study provides the first transnational evidence from the earlier stages of the COVID-19 lockdown, showing that the higher perception of stress, the less self-care activities are adopted, and in turn the lower the beneficial effects on well-being.

Keywords: COVID-19, mental health, preventive medicine, primary care, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study explores the role of the adoption of self-care activities in the relationship between perceived stress and psychological well-being in a general population of four countries at the beginning of the COVID-19 lockdown, while considering the influence of sociodemographic, socioeconomic and COVID-19-related factors.

Data are derived from a well-balanced sample by gender and age.

A large part of the sample consisted of university population and front-line COVID-19 workers with high income, which may bias the interpretation of the results as they cannot be representative of the more disadvantaged or vulnerable social groups.

The cross-sectional design precludes the demonstration of a causal relationship between stress, self-care and psychological well-being.

Self-reported outcome variables can be inherently biased and confounding.

Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak has forced many countries to separate, isolate and restrict the mobility of their citizens to reduce potential contact with the infection. The coronavirus outbreak and its subsequent mitigation measures have had mental health consequences for the world’s population.1–3 Measures such as confinement have led to social isolation, increased telework, increased time spent caring for dependent people such as children and elders, and negative socioeconomic consequences, among other aspects. These changes have had an impact on people’s lifestyles during and after the lockdown. The major negative psychological outcome of the COVID-19 lockdown is the anxiety and distress caused by it.4 5 An interesting study developed in the Italian population evaluated the differences in stress, anxiety and depression in two time frames during confinement (between 28 April and 3 May 2021), finding a causal relationship between the pandemic situation and the manifestation of negative psychological outcomes in anxiety and anguish.6 Likewise, other physical and mental health problems such as increased feelings of loneliness, exacerbated fear of the coronavirus, panic responses, sleep disturbances and symptoms of post-traumatic stress, among others, have been reported in the literature.7–11

In contrast, the adoption of self-care activities and health behaviours could play a critical role in the prevention of immediate and subsequent complications.12 However, its role has been especially studied in patients with chronic conditions, women and healthcare professionals,13–18 and none in the general population or in extraordinary situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Relationship between stress, self-care and psychological well-being

According to Antonovsky,19 salutogenesis is defined as the concept of stress oriented to coping resources. The author questions and explains why some people may remain healthy despite the influence of many stressful situations and risk factors.20 21 In this regard, the model argues that both health and illness can be the result of stressors. Consequently, in this salutogenic model, health is understood as a dynamic self-regulation process21 that allows us to face everyday situations, understanding that the absolute control that the person can have over its determinants is unfeasible. Still, this model assumes that people are capable of improving their health.22

Taking into account that stress can be the result of situations such as the potential risk of contagion by COVID-19 as well as the personal repercussions that confinement has, it can drive changes in the way people implement self-care activities (such as physical activity, an adequate diet or a support network) as a coping mechanism, and as a result influence on their well-being. Thus, self-care could explain in part the effects of stress on psychological well-being. On one hand, less perceived stress is related to higher satisfaction with life and happiness.23 Likewise, psychological well-being is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease24 25 and protects against mental illness through components such as positive relationships with others, autonomy, environmental mastery and psychological flexibility.26 27 On the other hand, two proposals have recently provided evidence of how the assessment that the person makes of stressor experiences can influence the implementation of effective coping strategies.28 In this line, the influence of stress perception on self-care behaviours has been considered as a driver that explains gender differences of health promotion behaviour adoption; that is, women with higher levels of stress refrain more often from healthy behaviours than men, which could lead to worse levels of health and well-being.29 30 This has been supported by a recent study that showed that self-care mediates the negative relationship between stress and self-rated health status (understood as the experimentation of well-being) in a sample of 223 black women.31

This process can be explained by the theory of mentality32 and the biopsychosocial model of challenge and threat,33 which propose that when making assessments of the functionality of the stress, people can interpret stressful situations as challenges or threats and therefore they implement effective behaviours to keep or improve their well-being depending on their stress appraising. From Orem’s perspective, self-care is defined as a practice that has therapeutic effects on the development and functioning of people.34 For this reason, self-care is the result of the configuration of agency capacity, which requires awareness, detection and interpretation of psychological, emotional and physical problems that give rise to the achievement of an appropriate repertoire of behaviours.35

All the above leads to the question: what is the potential role of self-care during the COVID-19 lockdown in the already known negative relationship between stress and well-being? Although it is widely known that self-care involves various activities that potentially influence the health and well-being of people, as far as is known, the research exploring its role as a mechanism that explains the effects of stress on psychological well-being in the general population is scarce, and much more in a situation of confinement.

Moreover, considering the influence of some cultural and socioeconomic factors on this relationship, addressing these variables in that relationship can be critical to effectively promote people’s healthy behaviours.

Therefore, this study seeks to address knowledge gaps that may positively benefit understanding how changes in people’s psychological well-being can be explained by the joint effect of stress perception in self-care activities adoption. Understanding the mediation role of self-care activities in this relationship during the COVID-19 pandemic and across four different countries may clarify how far promoting healthy behaviours can serve as a worldwide critical strategy to keep people’s optimal well-being levels when experiencing a stressful event such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Purpose of the present study

First, this study aimed to investigate whether psychological well-being can be predicted by people’s stress perception, which other sociodemographic variables can be implied in this relationship and are common in four Ibero-American countries: Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Spain. Second, it seeks to determine whether the adoption of self-care activities mediates the relationship between stress and well-being, and lastly if this mediation role remains similar across these four countries.

Methods

Sample

This study obtained 3452 records of participants from the general population of four countries (Ecuador, Spain, Chile and Colombia) with different average days of confinement (25, 21, 17.5 and 17 days, respectively). Baseline data collection took place between 31 March 2020 and 14 April 2020. After reviewing the correct registration of data for all the participants, a stratified sample (N=1082 participants) was extracted by randomising cases from the four countries by gender and age.

Instruments

Sociodemographic questionnaire

This questionnaire is composed of several questions regarding sociodemographic information, such as age, gender, country, socioeconomic status, level of studies completed, professional group, adults and minors in charge, and employment situation both before and after the COVID-19 lockdown, along with information related to the COVID-19 lockdown, such as the number of days in quarantine, the number of people with whom the individuals live, attitude towards the search of information related to COVID-19, and health status including past psychological and physical illnesses and substance use.

Perceived Stress Scale

The Spanish version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10)36 was employed to assess individuals’ perceived stress. The PSS-10 is a self-report instrument that consists of 10 items ranging from 0=never to 4=very often. Subjects are asked to rate statements such as ‘In the past month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?’ or ‘In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way?’ A higher score on this scale corresponds to a higher level of perceived stress. Regarding its psychometric properties, the Spanish version of the PSS-10 showed adequate reliability (internal consistency, α=0.82; test–retest, r=0.77) and sensitivity. Concurrent validity was measured between the PSS and anxiety and distress scores with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (the anxiety subscale and the depression and anxiety combined scales, respectively) in a clinical sample, finding a positive correlation between variables.37 A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 was obtained in our sample for the PSS-10.

Self-Care Activities Screening Scale

The Self-Care Activities Screening Scale (SASS-14)38 was administered to assess self-care. This tool is composed of four dimensions (health consciousness, nutrition and physical activity, sleep quality, and interpersonal and intrapersonal coping strategies) with 14 items ranging from 1=never to 6=always, giving a score per dimension scale and a total score. Subjects are asked to rate statements such as ‘I reflect about my health a lot’ or ‘I actively participate in the initiatives of my community (eg, clapping, singing, playing music, offering my support in what I could help, etc.)’. The higher the total score, the greater the level of self-care activities in which the person engages. The scale has shown good psychometric properties, with good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.80) and convergent validity with stress and well-being measures. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77 was obtained in our sample for the SASS-14.

Psychological well-being

The Spanish version39 of the Ryff Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWBS)40 41 was administered to assess well-being. The PWBS has 29 items ranging from 1 to 6, with a minimum score of 29 and a maximum score of 174. Subjects are asked to rate statements such as ‘Some people wander aimlessly through life, but I am not one of them’ or ‘When I look at the story of my life, I am pleased with how things have turned out so far’. This scale is grouped into six subscales: self-acceptance, positive relationships with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life and personal growth. The scale showed an excellent level of fit to the theoretical model proposed by D van Dierendonck, with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.71–0.84).41 A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 was obtained for the PWBS in our sample.

Procedure

The sample data were obtained on the basis of an online survey shared on social media in each of the countries (taking approximately 15–20 min) by snowball sampling. Participants first received both written consent and study instructions. Participation in the study was anonymous, voluntary and without economic compensation. Considering that the countries evaluated were at the beginning of the pandemic, the psychological instruments asked the subjects about the assessment of the items in the last month.

Statistical analysis

SPSS V.24 was used for data entry and analyses. Descriptive statistics analysis was used to summarise the sociodemographic data (age, gender, country, educational level and income level) and the COVID-19 variables (confinement days, front-line workers, health risk, employment changes, accompanied during lockdown, community resources and absence/presence of being in charge of children or elderly people). Four analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were carried out separately to compare differences in relation to age, stress, well-being and self-care between countries.

First, a three-step procedure was conducted to determine whether socioeconomic variables associated with confinement would significantly predict the levels of stress, well-being and self-care. In order to do so, three separate multiple linear regression analyses were performed using the stepwise method (three-step hierarchical). Step 1 included the sociodemographic variables (age as continuous, gender and country as nominals, and education and income levels as ordinals) as predictors, with the country included as a dummy variable; step 2 included the COVID-19 variables (accompaniment in confinement and work situation changes as nominals) as predictors; and in step 3 stress, self-care or well-being were included as predictors according to the respective regression analysis. Once the common variables that significantly predict stress, well-being and self-care had been identified, a fourth multiple regression analysis was conducted on well-being, with stress, self-care and their common predictors as independent variables. Finally, the relationship between stress, well-being, self-care and their common predictors was evaluated using bivariate Pearson’s correlations in order to check for significant associations between them.

Lastly, mediation analyses were performed for each country and for the total sample in order to examine the mediation role of self-care in the relationship between perceived stress and psychological well-being, where stress was included as the independent variable (X), well-being as the dependent variable (Y) and self-care was added between them as a mediating variable (M). Additionally, the covariates that significantly alter this relationship were considered in this model to account for confounding effects. The bias correction bootstrap method was used to verify the mediating effect of self-care on the relationship between stress and well-being (a total of 5000 bootstrap samples were extracted from the original data for indirect estimation). In all statistical tests, a p value of 0.05 was considered. Finally, we used PROCESS V.3.4.1 software42 43 to perform the mediation analysis (model 4).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Data of 1082 participants from four countries were obtained: Chile (n=261), Colombia (n=268), Ecuador (n=282) and Spain (n=271). The mean age of the participants was 43.8 years old (SD=15.1; age ranged from 18 to 95) and 49% (551) of the participants were female (table 1). With regard to educational level, 73.6% (796) of the participants had university education, 11.3% (122) technical studies, 14.1% (153) secondary education and 1% (11) elementary education. In addition, a high percentage of participants were found to have medium-income and high-income levels (measured in statutory minimum monthly wage (mmw) in American dollars; 1=US$300) in all countries: 30.3% (328) earned more than five times the mmw; 16.2% (175) earned four times the mmw; 17.5% (189) earned three times the mmw; 13.4% (145) earned two times the mmw; 8% (87) earned less than the mmw; and 14.6% (158) of the sample had no income. The highest percentages of income in the four countries were reported for men.

Table 1.

Descriptive values of the sociodemographic variables, stress, well-being and self-care scores in the four countries and of the total sample

| Spain | Chile | Colombia | Ecuador | Total | ANOVA p value | |

| Sample size | 271 | 261 | 268 | 282 | 1082 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 43.8 (15.7) | 43.9 (14.5) | 44 (14.8) | 44 (14.8) | 43.8 (15.1) | 0.99 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Female | 136 (50.2) | 127 (48.7) | 131 (48.9) | 137 (48.6) | 531 (49.1) | |

| Male | 135 (49.8) | 134 (51.4) | 137 (51.1) | 145 (51.4) | 551 (50.9) | |

| Psychological variables, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Stress | 17.0 (6.1) | 17 (6.2) | 15.3 (6.3) | 16.2 (6.3) | 16.4 (6.4) | 0.001 |

| Well-being | 30.6 (5.8) | 31.5 (5.9) | 32.6 (5.4) | 32.2 (5.7) | 31.7 (5.7) | 0.33 |

| Self-care | 58.5 (9.1) | 58.2 (11) | 59.9 (9.3) | 59.1 (10.1) | 58.9 (9.9) | 0.22 |

| Income level, n (%) | ||||||

| No salary | 45 (16.6) | 27 (10.3) | 43 (16) | 43 (15.2) | 158 (14.6) | |

| One mw | 9 (3.3) | 22 (8.4) | 37 (13.8) | 19 (6.7) | 87 (8) | |

| Two mw | 30 (11) | 36 (13.8) | 37 (13.8) | 42 (15) | 145 (13.4) | |

| Three mw | 50 (18.5) | 35 (13.4) | 68 (25.3) | 36 (12.7) | 189 (17.5) | |

| Four mw | 59 (21.7) | 34 (13) | 30 (12) | 52 (18.4) | 175 (16.2) | |

| Five mw | 78 (28.8) | 107 (41) | 53 (19.7) | 90 (32) | 328 (30.3) | |

| Educational level, n (%) | ||||||

| Elementary | 4 (1.48) | 4 (1.53) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 11 (1) | |

| High school | 42 (15.5) | 28 (7.0) | 35 (13.5) | 48 (17.0) | 153 (14.1) | |

| Technical | 37 (13.7) | 33 (12.7) | 40 (15.3) | 12 (4.3) | 122 (11.3) | |

| University | 188 (69.3) | 196 (75.1) | 192 (74.5) | 220 (78) | 796 (73.6) | |

| COVID-19 variables, n (%) | ||||||

| Confinement days | 21 (4.6) | 17.5 (6.5) | 17 (4.0) | 25 (0.6) | 20.24 (5.51) | |

| Front-line workers (yes) | 80 (29.5) | 80 (30.7) | 131 (48.9) | 76 (27) | 367 (33.9) | |

| Health risk (yes) | 89 (32.8) | 84 (32.2) | 77 (28.7) | 87 (30.9) | 337 (31.1) | |

| Employment changes (yes) | 46 (17) | 51 (19.5) | 87 (32.4) | 87 (31) | 271 (25) | |

| Accompanied during lockdown (yes) | 231 (85.2) | 237 (91) | 266 (99.2) | 248 (88) | 982 (90.8) | |

| Community resources (yes) | 245 (90.4) | 233 (89.2) | 225(84) | 251 (89) | 936 (85.5) | |

| Children in charge (yes) | 63 (23.2) | 86 (33) | 93 (34.7) | 95 (33.6) | 337 (31.1) | |

| Older people in charge (yes) | 29 (10.5) | 57 (22) | 106 (39.5) | 95 (33.6) | 287 (26.5) | |

Age, stress, well-being and self-care were coded as continuous variables, gender was coded as nominal variable, and income and educational levels were coded as ordinal variables. All COVID-19 variables were nominal with the exception of the number of confinement days, which was continuous.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; mw, minimun wage.

As for the sociodemographic factors associated with COVID-19, the average number of days of confinement was higher in Ecuador and Spain, with 25 (SD=4.5) and 21 (SD=1.0) days, respectively. Meanwhile, Chile and Colombia, with 17.5 (SD=6.5) and 17 (SD=4.0) days, respectively, presented a similar period of confinement. For the total sample, 90.8% (982) of the participants were accompanied during the lockdown, and 26.5% (287) and 31.1% (337) had elderly people and children in charge, respectively. In total, 86.5% (936) reported having community support resources. Finally, 33.9% (367) of the total sample considered themselves front-line workers and 31.1% (337) expressed a potential risk of contagion from SARS-CoV-2 in the last month, while 25% (271) had suffered negative changes in their employment conditions.

The results of the ANOVA did not show differences between countries for the variables age, well-being and self-care. However, there were differences between countries for stress. Post-hoc analyses indicated that Chile and Spain had higher stress in comparison with Colombia (table 1).

Predictive value of sociodemographic factors, stress and self-care in psychological well-being

Multiple linear regression analyses on stress, well-being and self-care contemplated nominal variables such as gender, work situation changes and accompaniment in confinement; the country variable was coded as a dummy, and education and income levels were treated as ordinals. The multiple linear regression on stress showed that age, gender, educational level, income level, country, work situation changes and accompaniment in confinement were statistically significant (F7,1080=15.379, p<0.001), predicting 9.1% of stress variability. The multiple linear regression analysis on well-being indicated that age, gender, educational level, income level and accompaniment in confinement were statistically significant (F6,1074=12.021, p<0.001), predicting 6.3% of well-being variability. The multiple linear regression analysis on self-care showed that age, gender, country and income level were statistically significant (F6,1074=4.335, p<0.001), predicting 2.4% of self-care variability. Thus, the three previous multiple regression analyses indicated that age, gender and income level commonly and significantly predict the three main variables: stress, well-being and self-care. In consequence, a multiple regression analysis performed on well-being while including age, gender, income level, stress and self-care as independent variables resulted in statistical significance (F5,1075=221.42, p<0.001), and only demonstrated significance with age, stress and self-care, predicting 50% of well-being variability. Therefore, age was the only sociodemographic variable included as a covariate in the mediation models (see table 2).

Table 2.

Data on the multiple linear regression models of stress, well-being and self-care based on sociodemographics and COVID-19-related variables

| Variable | 1. Stress | 2. Well-being | 3. Self-care | ||||||||||||

| ß | SE | 95% CI | P value | ß | SE | 95% CI | P value | ß | SE | 95% CI | P value | ||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | ||||||||||

| Age | −0.134 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.03 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.42 | 0.05 | 0.21 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 | <0.02 |

| Educational level | −0.107 | 0.27 | 1.42 | −0.35 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.87 | 0.30 | 3.7 | <0.01 | |||||

| Income level | −0.114 | 0.12 | −0.66 | −0.16 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.91 | 2.48 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.77 | <0.02 |

| b | P value | b | P value | b | P value | ||||||||||

| Gender | 0.91 | <0.01 | 2.47 | <0.01 | −1.84 | <0.002 | |||||||||

| Country | −0.169 | <0.001 | 1.52 | <0.02 | |||||||||||

| Accompaniment in confinement | −2.042 | <0.001 | 5.21 | <0.01 | |||||||||||

| Work situation changes | 0.99 | <0.01 | |||||||||||||

| 4. Well-being | |||||||||||||||

| ß | SE | LL | UL | P value | |||||||||||

| Age | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.30 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Stress | −0.62 | 0.07 | −2.12 | −1.84 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Self-care | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.54 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

ß: standardised coefficients are reported for continuous and ordinal variables; b: unstandardised coefficients are reported for nominal variables.

LL, lower limit CI; UL, upper limit CI.

Table 3 shows the pairwise correlations between the variables included in the mediation analyses: perceived stress, self-care, psychological well-being and age.

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlations between the variables included in the mediation analyses

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1. Stress | r | ||||

| P value | |||||

| 2. Well-being | r | −0.677 | |||

| P value | <0.001 | ||||

| 3. Self-care | r | −0.213 | 0.359 | ||

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| 4. Age | r | −0.182 | 0.153 | 0.092 | |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.014 | ||

Mediating role of self-care activities between stress and well-being

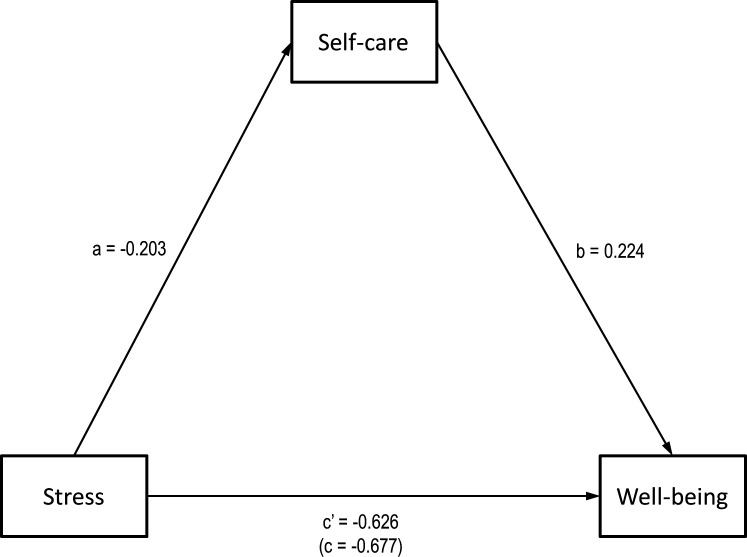

Results from the mediation model assessing the explanatory role of self-care in the relationship between stress and well-being with age as a covariate showed that a higher level of perceived stress is significantly associated with a lower level of self-care, which in turn is significantly associated with lower levels of well-being (F(3,1078)=370.01, p<0.001, R2=0.507). The indirect effect of perceived stress on well-being through self-care is negative and statistically different from zero (a*b=−0.144, p<0.001, with a 95% bootstrap CI of −0.20 to −0.095). The direct effect is weaker than it was prior to this control in the negative direction (c=−0.672) but remained statistically significant (c’=−0.626, p<0.001). These results indicate that self-care partially mediates the effect of perceived stress on well-being (see figure 1 with standardised coefficients). Regarding the age covariate, the mediation analysis showed non-significant effects on self-care nor well-being. Thus, stress, self-care and age variables predict 50.7% of well-being variability (see table 4).

Figure 1.

Mediation model of self-care in the relationship between stress and well-being controlled with standardised coefficients.

Table 4.

Data on the estimated mediation models (corresponding to the indirect and direct paths) for the total sample and differentiated by country

| Variables | Stress (X) and self-care (M) | Self-care (M) and well-being (Y) | Stress (X) and well-being (Y) | |||||||||

| Coef* | SE | 95% CI | P value | Coef* | SE | 95% CI | P value | Coef* | SE | 95% CI | P value | |

| Total sample | ||||||||||||

| a | −0.32 | 0.05 | −0.41 to −0.22 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| b | 0.46 | 0.04 | 0.37 to 0.55 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| c | −1.98 | 0.07 | −2.13 to −1.85 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| c’ | −2.13 | 0.07 | −2.27 to −1.99 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Age | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.01 to 0.08 | <0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 to 0.08 | <0.39 | ||||

| Stress and self-care as predictors of well-being, R2/F | 0.51/370.01 | Stress as a predictor of well-being, R2/F | 0.46/223.34 | |||||||||

| Spanish sample | ||||||||||||

| a | −0.21 | 0.09 | −0.39 to −0.34 | <0.01 | ||||||||

| b | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.14 to 0.53 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| c | −1.73 | 0.14 | −2.02 to −1.45 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| c’ | −1.81 | 0.14 | −2.10 to −1.52 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Age | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.10 to 0.04 | <0.34 | −0.04 | 0.65 | −0.15 to 0.07 | <0.49 | ||||

| Stress and self-care as predictors of well-being, R2/F | 0.39/56.6 | Stress as a predictor of well-being, R2/F | 0.36/75.76 | |||||||||

| Chilean sample | ||||||||||||

| a | −0.48 | 0.09 | −0.67 to −0.28 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| b | 0.50 | 0.08 | 0.33 to 0.67 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| c | −1.84 | 0.07 | −2.12 to −1.56 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| c’ | −2.08 | 0.14 | −2.37 to −1.80 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Age | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03 to 0.20 | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.08 to −0.15 | <0.59 | ||||

| Stress and self-care as predictors of well-being, R2/F | 0.52/96.45 | Stress as a predictor of well-being, R2/F | 0.46/112.47 | |||||||||

| Colombian sample | ||||||||||||

| a | −0.25 | 0.08 | −0.43 to −0.07 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| b | 0.55 | 0.09 | 0.36 to 0.74 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| c | −2.16 | 0.14 | −2.44 to −1.88 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| c’ | −2.30 | 0.14 | −2.60 to −2.01 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Age | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.01 to 0.14 | <0.09 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.09 to −0.15 | <0.61 | ||||

| Stress and self-care as predictors of well-being, R2/F | 0.54/105.09 | Stress as a predictor of well-being, R2/F | 0.48/125.88 | |||||||||

| Ecuadorian sample | ||||||||||||

| a | −0.26 | 0.09 | −0.45 to −0.06 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| b | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.29 to 0.60 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| c | −2.25 | 0.13 | −2.51 to −1.98 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| c’ | −2.36 | 0.13 | −2.63 to −2.09 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Age | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.05 to 0.10 | <0.55 | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.06 to 0.15 | <0.43 | ||||

| Stress and self-care as predictors of well-being, R2/F | 0.58/131.12 | Stress as a predictor of well-being, R2/F | 0.54/163.78 | |||||||||

X= Independent variable; M= mediator; Y= Dependent variable.

*Unstandardised coefficients.

These results were replicated in the four participant countries, given those self-care activities operated in the same way as a mediator of the relationship between perceived stress and psychological well-being in the samples from Spain, Colombia, Chile and Ecuador (see table 4).

Discussion

The aims of this study were to identify the role of self-care activities in the relationship between stress and well-being in the general population in a situation of COVID-19 confinement and to assess the impact of sociodemographic and COVID-19 variables on this relationship. The results described above indicate that self-care activities significantly operate as a mediating mechanism in the association between perceived stress and psychological well-being in a confinement situation, regardless of the country and other sociodemographic variables. These findings indicate that people’s stress perception across different countries during COVID-19 lockdown has compromised their self-care activities adoption, therefore reducing its potential beneficial effect as a strategy to keep their psychological well-being.

Therefore, our results suggest that adopting self-care activities can improve people’s well-being during the COVID-19 lockdown, but the higher the perceived stress of the situation, the more difficult it is to engage in self-care activities, resulting in a lower perception of psychological well-being. The present results are in line with those studies conducted in psychology students16 or professionals13 which have shown a relationship between personal care and well-being. In the same way, in the context of COVID-19 pandemic, improvement in personal resources seems to be relevant to overcome stress and its associated health problems.44 These results highlight the essential role of people in creating their own health and well-being since self-care can be considered an important individual health asset for the maintenance of one’s own health and that of society in general.45 46 However, none of these studies has considered this influence of self-care on well-being depending on a causal driver, such as the stress perception related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

One possible explanation of the mediation role of self-care is that the manifestation of self-care activities is linked to the adoption of healthy habits in the general population, which is associated with cognitive, emotional and behavioural processes.47 48 These processes are also significantly involved in stress and well-being perception.49–52 From a theoretical perspective, it may imply that a person who makes use of these types of activities when perceiving a stressful situation might use it as a strategy to take control over the situation51 and play an active role in the maintenance of their health and in the recovery of their well-being.52 However, this study might suggest that when the situation is perceived as a threat as the perception of stress is high, the cognitive, emotional and behavioural resources involved could determine the availability of resources that are needed to adopt healthy behaviours. As a result, implementing those behaviours could be seen by the person as an additional source of stress and reduce their engagement with health promotion behaviours, which in turn lower the levels of well-being.

This would be in line with recent research that has highlighted that it is not the type or amount of stress that determines its impact, but rather the mindset used to appraise the situation of perceived stress,46 which is congruent with the theory of mentality32 and with the biopsychosocial model of challenge and threat.33 Therefore, depending on a person’s mindset, a stressful situation can increase her/his physiological response and compromise her/his coping skills or use it as a personal growth opportunity.

In line with the above, the border between normative, tolerable and toxic stress is highly subjective, and the way in which a person interprets reality is crucial. Thus, certain self-care resources, such as a healthy diet, sleep or exercise, do not have an automatic beneficial lasting effect, but rather it is also necessary to work on other personal aspects, such as how the events experienced are meant and understood. It would therefore be worthwhile to support self-care resources with a process of personal resignification as well as explore other potentially beneficial effects from external resources such as social support,38 which have not been explored in this study.

Additionally, an optimal level of self-care has implications not only for personal growth and stress management but also to improve public health guidelines adherence and reduce SARS-CoV-2 comorbidities. It is due to the fact that being involved in self-care activities implies a certain level of health consciousness, which facilitates the adoption of health-protective measures (eg, using a mask or taking social distance) and in turn conduct healthy behaviours (eg, diet, adequate levels of vitamin D and exercise). These factors could serve as important health protectors for SARS-CoV-2 contagion and health complications.53 54 However, we should not overestimate the effect of the population’s self-care on health and well-being without taking into consideration its negative relationship with stress perception and thus the importance to deal first with this psychological appraisal process.

Nevertheless, we need to take into account some considerations related to the mediation of self-care in the relationship between stress and well-being in the general population. First, a partial mediation indicates that self-care does not explain the totality of the perceived stress effect on well-being. Although recent works claim that partial mediation has little value and should be abandoned,55 56 others support that a more realistic goal in psychological studies dealing with phenomena that have multiple causes may be to seek mediators that significantly decrease the direct path rather than eliminating the relation between the independent and dependent variables altogether.57 From a theoretical point of view, a significant reduction demonstrates that a given mediator is indeed potent, although not both a necessary and a sufficient condition for an effect to occur.

Although the PSS is the most widely used psychological instrument for measuring the perception of stress, most of its items associate stress with negative emotions and ‘threat’ characterised by situational demands exceeding coping resources.58 Moreover, despite the SASS considering four important dimensions of self-care (health consciousness, nutrition and physical activity, sleep, and intrapersonal and interpersonal coping skills) and being validated on the general population at the beginning of the COVID-19 context (when coping strategies were not probably fully established), it is supposed that psychological, emotional, professional and spiritual components may also participate in the mediating effect between stress and well-being. Furthermore, considering that not all stressors that explain well-being can be explained by self-care, it is not surprising that self-care cannot explain the totality of such a relationship by itself. For this reason, it is crucial to identify the factors that can act as promoters and maintainers of well-being.

Regarding the contributions of the present study, it should be highlighted that it is the first research to explore the mediating role of self-care activities between stress and well-being in the general population during COVID-19 lockdown. However, the present study presents some limitations. First, our sample was composed of people with a similar high socioeconomic situation in the four countries. Therefore, these findings may not be representative of the more disadvantaged or vulnerable social groups. Second, the use of self-report instruments and social desirability may have influenced the results. Third, the study has a cross-sectional design and thus it is not possible to conclude causal relations between the assessed variables.

As future lines of research, it would be of great value to continue this research line to understand better which specific dimensions of self-care are the most important mechanisms to explain the relationship between stress and psychological well-being. Furthermore, it would be critical to conduct longitudinal studies to ascertain cause–effect relationships between the measured variables and explore differences in self-care, stress and well-being at different measurement times. Based on this, it would be appropriate to design intervention programmes or strategies aimed at reducing stress perception and promoting self-care strategies as a possible pathway to keep healthy during extraordinary situations such as a lockdown. Lastly, it is worth noting that our general population sample was confined in their respective countries at the time of data collection, but one-third were workers of health and basic services (ie, front-line COVID-19 workers). Considering that some front-line workers, while confined, worked longer hours than usual (eg, health workers) or fewer hours (eg, supermarket workers) and that they could be exposed to a greater risk of contagion, it would be interesting to address the impact of self-care on the relationship between stress and well-being in this population in future research.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EL, EB-M, AS and PF-B: contributed to the conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology and writing - original draft. EL, EB-M and PF-B: supervision. MM: data curation, formal analysis and methodology. AS, EYO, CC, MSG and JVO: investigation, methodology and resources. EL is responsible for the overall content as the guarantor. All authors contributed to reviewing and editing the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was partially supported by the following projects: PSI2017–84170–R to PF-B and UMA18–FEDERJA–114 to PF-B.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in this work with human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Navarra (Spain; project ID: 2020.058) and the University of San Francisco de Quito (Ecuador; P2020-024M) for Latin-American samples. In the case of groups from Colombia, Ecuador and Chile, approval was given by their local ethics committee.

References

- 1.Vindegaard N, Benros ME, Eriksen Benros M. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun 2020;89:531–42. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sibley CG, Greaves LM, Satherley N, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. Am Psychol 2020;75:618. 10.1037/amp0000662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zacher H, Rudolph CW. Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol 2021;76:50–62. 10.1037/amp0000702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:817–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimhi S, Eshel Y, Marciano H, et al. Distress and resilience in the days of COVID-19: comparing two ethnicities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3956. 10.3390/ijerph17113956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roma P, Monaro M, Colasanti M, et al. A 2-month follow-up study of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 lockdown. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:8180. 10.3390/ijerph17218180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo Coco G, Gentile A, Bosnar K, et al. A Cross-Country examination on the fear of COVID-19 and the sense of loneliness during the first wave of COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:2586. 10.3390/ijerph18052586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020;395:912–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos Miguel Ángel, et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:172–6. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:901–7. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Ma ZF,. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:2381. 10.3390/ijerph17072381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unadkat S, Farquhar M. Doctors’ wellbeing: Self-care during the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020;368:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayala EE, Ellis M, Grudev N, et al. Women in health service psychology programs: stress, self-care, and quality of life. Train Educ Prof Psychol 2017;11:18. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buck HG, Shadmi E, Topaz M, et al. An integrative review and theoretical examination of chronic illness mHealth studies using the middle-range theory of self-care of chronic illness. Res Nurs Health 2021;44:47–59. 10.1002/nur.22073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riegel B, Dunbar SB, Fitzsimons D, et al. Self-Care research: where are we now? where are we going? Int J Nurs Stud 2021;116:103402. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rupert PA, Dorociak KE. Self-Care, stress, and well-being among practicing psychologists. Prof Psychol 2019;50:343–50. 10.1037/pro0000251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shepherd MA, Newell JM. Stress and health in social workers: implications for self-care practice. Best Pract Ment Health 2020;16:46–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haley WE, Roth DL, Coleton MI, et al. Appraisal, coping, and social support as mediators of well-being in black and white family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996;64:121–9. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.1.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonovsky A. Health, stress and coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-bass, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antonovsky A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot Int 1996;11:11–18. 10.1093/heapro/11.1.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mittelmark MB, Bull T, Bouwman L. Emerging ideas relevant to the salutogenic model of health. In: Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al., eds. The Handbook of Salutogenesis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2017: 45–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schiffrin HH, Nelson SK. Stressed and happy? investigating the relationship between Happiness and perceived stress. J Happiness Stud 2010;11:33–9. 10.1007/s10902-008-9104-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubzansky LD, Huffman JC, Boehm JK, et al. Positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1382–96. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. The heart's content: the association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychol Bull 2012;138:655–91. 10.1037/a0027448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keyes CLM. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: a complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am Psychol 2007;62:95. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wersebe H, Lieb R, Meyer AH, et al. Relación entre estrés, bienestar Y flexibilidad psicológica durante una intervención de autoayuda de Terapia de Aceptación Y Compromiso. Int J Clin Heal Psychol 2018;18:60–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jamieson JP, Crum AJ, Goyer JP, et al. Optimizing stress responses with reappraisal and mindset interventions: an integrated model. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 2018;31:245–61. 10.1080/10615806.2018.1442615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.García-Tascón M, Sahelices-Pinto C, Mendaña-Cuervo C, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 confinement on the habits of PA practice according to gender (male/female): Spanish case. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:6961. 10.3390/ijerph17196961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bermejo-Martins E, Luis EO, Sarrionandia A, et al. Different responses to stress, health practices, and self-care during COVID-19 Lockdown: a stratified analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:2253. 10.3390/ijerph18052253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adkins-Jackson PB, Turner-Musa J, Chester C. The path to better health for black women: predicting self-care and exploring its mediating effects on stress and health. Inquiry 2019;56:0046958019870968. 10.1177/0046958019870968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farberman HA. Mannheim, Cooley, and mead: toward a social theory of mentality. The sociological Quarterly. 11, 1970: 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seery MD. The biopsychosocial model of challenge and threat: using the heart to measure the mind. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2013;7:637–53. 10.1111/spc3.12052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Denyes MJ, Orem DE, Bekel G, et al. Self-care: a foundational science. Nurs Sci Q 2001;14:48–54. 10.1177/089431840101400113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banko T. Social work students, self-care, compassion fatigue, and burnout. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perera MJ, Brintz CE, Birnbaum-Weitzman O, et al. Factor structure of the perceived stress Scale-10 (PSS) across English and Spanish language responders in the HCHS/SOL sociocultural ancillary study. Psychol Assess 2017;29:320–8. 10.1037/pas0000336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Remor E. Psychometric properties of a European Spanish version of the perceived stress scale (PSS). Span J Psychol 2006;9:86–93. 10.1017/S1138741600006004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li F, Luo S, Mu W, et al. Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21:1–14. 10.1186/s12888-020-03012-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Díaz D, Rodríguez-Carvajal R, Blanco A, et al. [Spanish adaptation of the Psychological Well-Being Scales (PWBS)]. Psicothema 2006;18:572–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;57:1069–81. 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryff CD, Keyes CL. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995;69:719–27. 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayes AF. Process: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper], 2012. Available: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

- 43.Hayes AF. Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. second ed. New York: Guilford Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Werner A, Kater M-J, Schlarb AA, et al. Sleep and stress in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of personal resources. Appl Psychol Health Well Being 2021;13:1–17. 10.1111/aphw.12281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matarese M, Lommi M, De Marinis MG, et al. A systematic review and integration of concept analyses of self-care and related concepts. J Nurs Scholarsh 2018;50:296–305. 10.1111/jnu.12385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mittelmark MB, Bull T. The salutogenic model of health in health promotion research. Glob Health Promot 2013;20:30–8. 10.1177/1757975913486684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graybiel AM. Habits, rituals, and the evaluative brain. Annu Rev Neurosci 2008;31:359–87. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graybiel AM, Smith KS. Good habits, bad habits. Sci Am 2014;310:38–43. 10.1038/scientificamerican0614-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crum AJ, Jamieson JP, Akinola M. Optimizing stress: an integrated intervention for regulating stress responses. Emotion 2020;20:120. 10.1037/emo0000670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dienstbier RA. Arousal and physiological toughness: implications for mental and physical health. Psychol Rev 1989;96:84–100. 10.1037/0033-295X.96.1.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bavel JJV, Baicker K, Boggio PS, et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav 2020;4:460–71. 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, et al. How should we define health? BMJ 2011;343:d4163. 10.1136/bmj.d4163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gulia KK, Kumar VM. Importance of sleep for health and wellbeing amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Vigil 2020;4:49–50. 10.1007/s41782-020-00087-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamer M, Kivimäki M, Gale CR, et al. Lifestyle risk factors, inflammatory mechanisms, and COVID-19 hospitalization: a community-based cohort study of 387,109 adults in UK. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.059. [Epub ahead of print: 23 May 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rucker DD, Preacher KJ, Tormala ZL, et al. Mediation analysis in social psychology: current practices and new recommendations. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2011;5:359–71. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res Ther 2017;98:39–57. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51:1173–82. 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blascovich J, Mendes WB, Hunter SB, et al. Social "facilitation" as challenge and threat. J Pers Soc Psychol 1999;77:68–77. 10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.