Abstract

Objective

Informal caregiving may likely increase as the number of cancer survivors grows. Caregiving responsibilities can impact caregivers’ quality of life (QoL). Understanding the current state of the science regarding caregiving QoL could help inform future research and intervention development.

Methods

A systematic literature review in PubMed/Medline examined research on QoL among informal cancer caregivers and related psychosocial health outcomes. Original research articles in English, published between 2007 and 2017 about caregivers (aged ≥18 years) of adult cancer patients in the United States were included. Abstracted articles were categorized according to caregiving recipient’s phase of survivorship (acute, middle to long-term, end of life/bereavement).

Results

Of 920 articles abstracted, 60 met inclusion criteria. Mean caregiver age ranged from 37 to 68 with the majority being female, non-Hispanic white, with at least a high school degree, and middle income. Almost half of the studies focused on caregivers who provided care for survivors from diagnosis through the end of active treatment. Studies examined physical health, spirituality, psychological distress, and social support. Differences in QoL were noted by caregiver age, sex, and employment status.

Significance of Results

Additional research include the examination of the needs of diverse cancer caregivers and determine how additional caregiver characteristics (e.g., physical functioning, financial burden, etc.) affect QoL, including studies examining caregiver QoL in the phases following the cessation of active treatment and assessments of health systems, support services, and insurance to determine barriers and facilitators to meeting the immediate and long-term needs of cancer caregivers.

Keywords: informal caregivers, cancer, quality of life, social support, spirituality

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 25% of adults over the age of 18 years in the United States are currently serving as informal caregivers at any given time (Anderson et al. 2013). In this role, spouses or partners, family members, or friends provide “unpaid care, out of love, respect, or friendship, to assist with simple and occasional tasks and/or full-time care needs” (“Who are caregivers,” 2016). Approximately 10% of caregivers report caring for a person with cancer (Trivedi et al. 2014) and 37% of cancer survivors (“Basic Information About Cancer Survivorship,” 2016) report having an informal caregiver (de Moor JS et al. 2016). With more than 15 million cancer survivors currently (“United States Cancer Statistics,” n.d.) and a projected 20 million by 2026 in the United States (US) (Bluethmann, Mariotto, and Rowland 2016), informal caregiving for cancer survivors may likely increase.

Quality of life (QOL) consist of a range of domains to measure an individual’s overall health. Common dimensions of health used to measure QOL are physical, psychological, social and spiritual components (Post 2014). The demands of informal cancer caregiving can affect caregivers’ overall quality of life (QoL) and demands are associated with higher rates of poor physical (Grant et al. 2013, Harden et al. 2013, Kim, van Ryn, et al. 2015, Kim, Wellisch, and Spillers 2008) and mental health (Harden et al. 2013, Kim, van Ryn, et al. 2015, Langer, Brown, and Syrjala 2009, Lichtenthal et al. 2011, Kim, Kashy et al. 2008), psychological distress (Kim, Baker, and Spillers 2007, Kim et al. 2007, Kim and Spillers 2010), and feelings of life dissatisfaction (Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007, Kim, Carver, Deci, and Kasser 2008) (compared with non-caregivers) (Anderson et al. 2013). In addition, studies have shown that informal cancer caregivers may be responsible for performing technical tasks usually rendered by medical/nursing professionals (e.g., injections, tube feeding, etc.) (Teschendorf et al. 2007), which can result in increased emotional stress and physical strain (“2015 Report: Caregiving In The US,” 2015). Caregivers often felt unprepared to perform these tasks (Teschendorf et al. 2007) and identified education, communication, and resource needs to promote QoL (Tamayo, Broxson, Munsell, and Cohen 2010). The volume of caregiving responsibilities and length of time caring for a cancer survivor has also been associated with caregiver QoL (“2015 Report: Caregiving In The US,” 2015, Given BA, Given CW, and Sherwood 2012). For example, hours spent caregiving were negatively correlated with mental and psychological well-being (Ross, Mosher, Ronis-Tobin, Hermele, and Ostroff 2010). Additionally, social support (Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007, Milbury, Badr, Fossela, Pisters, and Carmack 2013, Siefert, Williams, Dowd, Chappel-Aiken, and McCorkle 2008, Spillers, Wellisch, Kim, Matthews, and Baker 2008) and the interpersonal relationship between caregiver and cancer survivor (Kershaw et al. 2008, Kim, Kashy et al. 2008, Porter, Keefe, Garst, McBride, and Baucom 2008) can impact caregivers’ QoL. Studies have demonstrated that lack of social support is related to difficulties in maintaining good physical and mental health (Mazanec, Daly, Douglas, and Lipson 2011, Milbury et al. 2013, Pawl, Lee, Clark, and Sherwood 2013).

To better understand the impact of caregiving it is important to identify the caregiving recipient’s phase of survivorship, which include acute, middle to long-term, and end of life/bereavement (Kim and Given 2008). For this purpose, we conducted a systematic review of the published literature to examine cancer caregiver QoL in which we characterized each study according to the phase of cancer survivorship to better understand caregiver concerns related to physical health, psychological distress, spirituality, and social support throughout the cancer experience. Findings from this review can help to identify research gaps and highlight opportunities for interventions to improve cancer caregiver QoL across the cancer experience.

METHODS

Search strategy

Our systematic literature review of PubMed/Medline articles examined research on QoL among informal cancer caregivers to improve their psychosocial health outcomes. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used to design and perform the literature review (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, and Altman 2009). The search was limited to English language studies, published between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2017, with adult caregivers of cancer patients (≥ 18 years) in the United States. Search terms used included cancer OR carcinoma AND caregiver OR carer AND “quality of life”, which were previously utilized in a literature review (Kim and Given 2008).

Eligibility Criteria

Studies met the following inclusion criteria: (1) a sample size over 50, (2) studies were conducted in the US, (3) results on informal cancer caregiver’s QoL, and (4) report on data from a quantitative study published in peer reviewed journals. Studies that had sample size of <50, were not specific to informal cancer caregivers, reported on the evaluation of assessment tools exclusively, were literature reviews, or were conducted outside of the US were excluded. Articles were also excluded if the results described only patients QoL. We also excluded studies of caregivers of pediatric cancer survivors due to unique burden placed on caregivers (usually the parents of pediatric cancer survivors), which increases their decision making responsibility compared with caregivers for adult cancer survivors (Jones and Barbara 2012). Additionally, case reports, commentaries, and studies where only clustered analyses with both patients and caregivers were reported were also excluded. Finally, qualitative and intervention studies were excluded from this review because the differences in study design makes it difficult to compare the findings.

Data Extraction

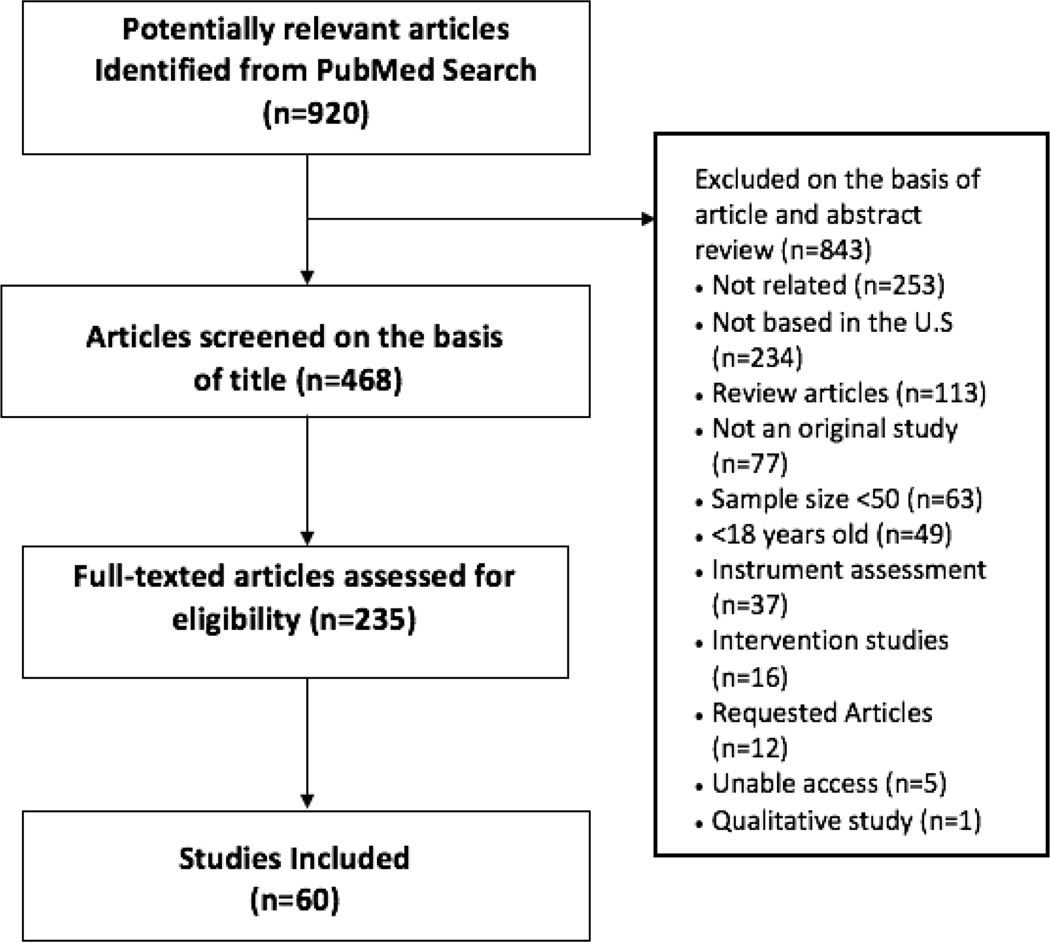

A total of 920 articles were identified, 685 of which did not meet study criteria on the basis of a title and abstract review. Two researchers reviewed titles and abstracts for all articles and classified abstracts as “relevant (R),” “needs more information (NMI),” or “not relevant (NR).” A full text paper review was conducted for 235 articles that were classified as “R” and “NMI.” From this review, 60 articles were determined to be relevant. To reduce reviewer bias, the reviewers tested for quality assurance and accuracy (reliability rate ≥75%). Figure 1 provides a flowchart of the article selection process with reasons for study exclusion.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart of studies selection process

Data Synthesis

For each study, the following information was abstracted: PubMed ID, title, author(s), year of publication, sample size, study population characteristics (age, type of cancer, gender, and relationship to cancer survivor), study design, measures used for outcomes of interest, and significant findings. All studies were categorized according to the caregiving recipient’s phase of survivorship (acute, middle to long-term, end of life/bereavement). Studies were classified in the “acute survivorship phase” when caregiving occurred from the point of diagnosis through the end of active treatment. Studies in the “middle to long-term phase” described outcomes related to post-treatment caregiving for survivors who were not on active treatment and/or had no evidence of disease (NED). The “end of life/bereavement phase” included studies reporting outcomes for caregivers of survivors who were experiencing metastatic or recurrent disease, at the end of life, in hospice care, or passed away due to cancer related illness. Studies were classified as “cross-listed” when findings were described across multiple phases (i.e., middle to long-term and bereavement phases). Additionally, studies that looked at post-diagnostic cancer caregiving without stratifying findings by acute, middle to long-term, or end of life/bereavement phases were identified as cross-listed.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

Among 60 relevant research articles, 38% (n=23) described caregiving QoL characteristics during the acute phase, 7% (n=4) during the middle to long-term phase, 12% (n=7) were during the bereavement phase, and 43% (n=26) across multiple phases of the survivorship trajectory (cross-listed). The majority of studies reported findings for non-Hispanic white, middle-income females with at least a high school education. Studies largely examined overall physical and mental health, psychological distress, spirituality and social support, with some studies reporting on multiple dimensions of psychosocial health. The sample sizes ranged from 54 (Siefert et al. 2008) to 1,666 (Kim, Kashy, Spillers, and Evans 2010) caregivers in studies examining outcomes among caregivers only. In studies examining convergence/ divergence among caregivers and patients dyads, studies ranged from 56 (Cooke, Grant, Eldredge, Maziarz, and Nai 2011) to 1820 dyads (Litzelman, Green, and Yabroff 2016). While most studies described spousal/significant other/partner caregiver-survivor relationships (N=54), other relationship types included adult children, parents, other family members (nieces, nephews, and grandchildren), and unrelated friends. About half of the articles used a cross-sectional study design (N=32) and a third of the articles used a longitudinal study design (n=23) to assess caregiving QoL from the point of patient diagnosis through 8 years post-diagnosis. Forty-five studies provided data on mean caregiver age, which ranged from 37 to 68 years. The majority of findings described caregivers who were female, with the exception of two studies (Mezue, Draper, Watson, and Mathew 2011, Siefert et al. 2008). Nationally representative findings on caregivers’ QoL were largely collected as a part of Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (“CANCORS”, n.d.) and the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (“MEPS”, n.d.) datasets.

Measures Used to Assess Concepts of QoL

All included studies used self-reported measures to assess differing concepts of QoL. Thirty-eight unique measures were identified (Table 1), including three developed or adapted for their respective studies to measure HRQOL (Prosser et al. 2015), psychological distress (Litzelman, Kent, and Rowland 2016, Parvataneni et al. 2011), and spirituality (Garrido and Prigerson 2014). Twenty-eight studies used the 12 and 36 item Medical Outcomes Study Index Short-form (MOS-SF) to assess the physical and mental health of caregivers. The most widely used assessments of psychological distress included: the Profile Mood State (POMS; 15 studies), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale (CES-D; 13 studies), and the Pearlin Stress Scale (PSS; 7 studies). The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp) was the most widely used scale to measure spiritual well-being as a domain of quality of life (10 studies). Caregivers perception of social support was assessed using the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) (Boehmer, Tripodis, Bazzi, winter, and Clark 2016, Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007, Kim, Shaffer, Carver, and Cannady 2014, Pawl et al. 2013, Sumner, Wellisch, Kim and Spillers 2015, Wright et al. 2010), Caregiver Reaction assessment (CRA) (Adams, Mosher, Cannady, Lucette and Kim 2014, Gaugler et al. 2008, Mazanec et al. 2011, Milbury et al. 2013, Siefert et al. 2008, Spillers et al. 2008, Washington, Pike, Demiris, and Oliver 2015), the Personal Resources Questionnaire (PRQ) (Kershaw et al. 2008, Northouse et al. 2007), the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Boehmer et al. 2016), the Medical Outcomes Social Support Survey (MOS-SS) (Mazanec et al. 2011), and the Linear Analog Self-Assessment (LASA) (Shahi et al. 2014).

TABLE 1.

STUDY CHARACTERISTICS BY ACUTE, MIDDLE-LONG TERM, BEREAVEMENT AND CROSS LISTED

| First Author, Year (Sample Sizea) | Study Design | Type of Cancer | Caregiver Characteristics (mean age; gender; relationship to patient) | Phase of Illness | Variables used in Analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbott, 2014 (127) | Longitudinal | Not specified | 53 y; 74% Female; 51% Spouse, 49% Other | Bereavement | Suicidal ideation |

| Adams, 2014 (70) | Longitudinal | Digestive system (21%), Genital system (16%), Breast (12%), Brain & other nervous system (9%), Respiratory system (7%), Lymphoma (7%); Other (20%) | 59 y (range: 24–79 y); 74% Female; 87% Spouse/Partner, 6% Child, 3% Parent, 4% Other | Acute | Spirituality Social Support |

| Boehmer, 2016 (167*) | Cross-sectional | Breast | HSWc: 62 y; 84% Male; 84% Spouse/Partner, 7% Child, 5% Sibling, 2% Parent, 2% Friend SMWd: 56 y; 94% Female; 86% Spouse/Partner, 2% Sibling, 2% Parent, 10% Friend | Cross-Listed | Fear of recurrence Social support |

| Clark, 2014 (131) | Longitudinal | Not specified | ≥ 18 y; 79% Significant other, 21% Family or friend | Acute | HRQOLb |

| Colgrove, 2007 (403) | Longitudinal | Prostate (26%), Breast (23%), Colorectal (15%), Lung (8%), Ovarian (7%), Kidney (7%), Other (≤ 5% each NHL, skin, or uterine) | 59 y (range: 29–88 y); 54% Female; Spouse | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Stress Spirituality |

| Cooke, 2011 (56*) | Correlational | Acute leukemia (45%), Myelodysplasia (33%), Chronic leukemia (7%), Other (14%) | ≥ 18 y; 76% Female | Acute | HRQOL |

| Deatrick, 2014 (186) | Cross-Sectional | Brain | 52 y (range: 30–69 y); 100% Female; Mother | Middle-Long | HRQOL Psychological distress Anxiety Posttraumatic stress |

| Douglas, 2013 (226*) | Prospective Longitudinal | GI (47%), Lung (29%), Gynecological (24%) | 58 y; 66% Female; 69% Spouse, 19% Child, 12% Other | Acute | Depressive symptoms HRQOL Spirituality |

| Fletcher, 2008 (60) | Correlational | Prostate | 64 y; 100% Female; Family | Acute | Functional status HRQOL Depressive symptoms Anxiety |

| Fujinami, 2015 (163) | Cross-Sectional | Non-small cell lung | 57 y (range: 21–88 y);64% Female;68% Spouse/Partner, 16% Daughter, 4% Son, 2% Parent, 9% Other | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Distress |

| Garrido, 2014 (245) | Longitudinal | Not specified | 52 y (range: 20–86 y); 76% Female; 57% Spouse | Bereavement | HRQOL Psychiatric disorders Depressive symptoms Anxiety Regret |

| Gaugler, 2008 (183) | Cross-Sectional | Stomach, Intestinal, colorectal; Head & neck; Pancreas, liver; Gynecological; Lung; Bone, leukemia; Breast; Prostate; Brain; Skin | 52 y (employed female), 60 y (not employed female), 53 y (employed male), 67 y (not employed-male); 72% Female; Spouse, Not Spouse | Acute | HRQOL Depressive symptoms Distress |

| Grant, 2013 (163) | Longitudinal | Non-small cell lung | 57 y (range: 21–88 y); 64% Female; 68% Spouse/Partner, 16% Daughters, 4% Son, 3% Parent, 9% Other | Acute | HRQOL Psychological distress |

| Harden, 2013 (95) | Longitudinal | Prostate | 61 y; 100% Females; 100% Spouse | Middle-Long | HRQOL Sexual satisfaction Stress |

| Kershaw, 2008 (121*) | Longitudinal | Prostate | >21 y; Spouses/Partners | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Psychological distress Social Support |

| Kershaw, 2015 (484*) | Longitudinal | Lung (24%), Colorectal (23%), Breast (37%), Prostate (16%) | 57 y (range: 26–95 y); 57% Female; 74% Spouse/Partner, 19% Relatives, 7% Other | Acute | HRQOL |

| Kim, 2007a (448) | Cross-Sectional | Prostate (21%), Breast (21%), Colorectal (15%), Lung (10%), Kidney (8%), Ovarian (7%), NHL (5%), Bladder (5%), Skin (5%), Uterine (5%) | 55 y; 62% Female; 78% Spouse, 22% Child | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Psychological distress Stress Spirituality |

| Kim, 2007b (252) | Cross-Sectional | Breast (56%), Ovarian (15%), Kidney (6%), Lung (18%), NHL (4%), Skin melanoma (3%) | 48 y; 100% Female; 44% Daughter, 24% Sister, 11% Mother, 8% Friend, 4% Daughters-in-law, 3% Partner, 5% Others, 2% Other in-laws | Cross-Listed | Psychological distress Stress Spirituality |

| Kim, 2007c (779) | Cross-Sectional | Breast (28%), Prostate (20%), Colorectal (13%), Lung (10%), NHL (8%), Ovarian (6%), Skin (5%), Bladder (5%), Kidney (5%), Uterine (5%) | 55 y (range: 19–90 y); 65% Female; 66% Spouse, 17% Child, 7% Sibling, 4% Parents, 4% Friends | Cross-Listed | Stress Depressive symptoms Spirituality Social support |

| Kim, 2008a (321) | Cross-Sectional | Breast (25%), Prostate (24%), Colorectal (11%), NHL (11%), Lung (9%), Bladder (5%), Kidney (5%), Ovarian (5%), Skin (5%), Uterine (5%) | 57 y; 51% Female; Spouse | Cross-Listed | Depressive symptoms Life satisfaction |

| Kim, 2008b (168*) | Cross-Sectional | Breast (49%), Prostate (51%) | 60 y; 100% Spouse | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Psychological distress |

| Kim, 2008c (98*) | Cross-sectional | Breast (25%), Colorectal (15%), Ovarian (13%), Lung (12%), Kidney (8%), Uterine (5%), NHL (2%), Skin melanoma (2%) | 41 y (range: 18–73 y); 100% Female; 100% Daughter | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Psychological distress |

| Kim, 2010a (1,666) | Cross-Sectional | Cohort 1: Colorectal Cohort 2: Breast (27%), Colorectal (14%), Lung (11%), NHL (9%), Prostate (18%), Ovarian (6%) Cohort 3: Breast (25%), Colorectal (16%), Lung (8%), NHL (4%), Prostate (20%), Ovarian (8%) | Cohort 1: 53 y (range: 19–94); 79% Female; 32% Spouse, 68% Other; Cohort 2: 54 y (range: 19–90 y); 65% Female; 66% Spouse, 34% Other Cohort 3: 59 y (range: 26–99 y); 64% Female; 66% Spouse, 34% Other | Cross-Listed | HRQOL |

| Kim, 2010b (1,358) | Cross-Sectional | Breast (26%), Colorectal (15%), Kidney (6%), Lung (11%), NHL (7%), Ovarian (7%), Prostate (18%), Other (each <5% Bladder, Skin melanoma, Uterine) | 55 y (range: 18–90 y); 65% Female; 66% Spouse, 18% Child, 7% Sibling, 4% Parent, 3% Friend | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Psychological distress Spirituality |

| Kim, 2011 (361*) | Cross-Sectional | Breast (25%), Colorectal (14%), Kidney (8%), Lung (6%), Prostate (26%), Ovarian (7%), Bladder (5%), Skin melanoma (5%), NHL (5%), Uterine (5%) | 59 y; 52% Female; Spouse | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Spirituality |

| Kim, 2012a (1,218) *Middle-Long Term and Bereaved Phase* | Longitudinal | Breast, Colorectal, Kidney, Lung, NHL, Ovarian, Prostate, Other (bladder, skin melanoma, uterine) | FCRe: 59 y; 63% Female; 71% Spouse, 14% Child, 6% Sibling, 4% Parent, 4% Friend, 2% Other FCBf: 60 y; 79% Female; 63% Spouse, 22% Child, 7% Sibling, 3% Parent, 3% Friend, 2% Other CCg: 60 y; 62% Female; 68% Spouse, 12% Child, 7% Parent, 7% Sibling, 2% Friend, 3% Other | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Stress Psychological distress Spirituality |

| Kim, 2012b (455*) | Cross-Sectional | Breast (30%), Prostate (22%), Colorectal (15%), Lung (8%), Ovarian (6%), Kidney (7%), Uterine (5%), Other (<5% bladder, NHL and skin melanoma) | ≥ 18 y; 63% Female; 67% Spouse, 19% Child, 14% Other | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Fear of recurrence Anxiety |

| Kim, 2014 (416) *Middle-Long Term and Bereaved Phase* | Longitudinal | Breast (26%), Colorectal (14%), Lung (12%), NHL (8%), Prostate (19%), Ovarian (5%), Skin (4%), Other (11%, Bladder, Kidney, Uterine) | 55 y;65% Female;72% Spouse, 28% Other | Cross-Listed | Depressive symptoms Stress Social Support |

| Kim, 2015a (369) | Longitudinal | Breast (30 %), Prostate (22%), Colorectal (13 %), NHL (8 %), Lung (8 %), Other (<5%) | Range: 19–90 y; 63% Female; 73% Spouses, 14% Child, 6% Sibling | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Spirituality |

| Kim, 2015b (1,517) *Middle-Long Term and Bereaved Phase* | Longitudinal | Breast (27%), Colorectal (14%), Lung (11%), NHL (8%), Prostate (18%), Other (each <5% Bladder, Kidney, Skin & Uterine) | 55 y; 65% Female; 67% Spouse, 18% Child, 7% Sibling, 4% Parent, 3% Friend, 2% Other | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Stress |

| Kim, 2015c (398*) | Cross-Sectional | Lung (47%), Colorectal (53%) | ≥ 21 y; 78% Female; 64% Spouse, 15% Child, 9% Parent, 5% Sibling, 7% Other | Acute | HRQOL Depressive symptoms |

| Langer, 2009 (80*) | Prospective Longitudinal | Acute Leukemia (45%), Myelodysplasia (28%), Lymphoma (6%), Chronic myeloid leukemia (5%), Multiple Myeloma (5%), Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (5%), Aplastic Anemia (3%), Other (4%) | 55 y (range: 26–78 y); 68% Female; 100% Spouse/Partner | Acute | HRQOL Protective buffering h Relationship satisfaction |

| Lichtenthal, 2011 (86) | Longitudinal | Not specified | ≥ 20y; 84% Female; 46% Spouse/Partner, 25% Child, 29% Other | Bereavement | HRQOL Suicidality Psychiatric disorders Grief |

| Litzelman, 2015 (1,820*) *Majority post-treatment* | Longitudinal | Blood (8%), Breast (20%), Colorectal (5%)), Prostate (20%), Multiple (10%), Other (36%) | HCi Wife 63 y, WCj Husband 58 y;53% Female;100% Spouse | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Depressed mood |

| Litzelman, 2016a (1,500) | Cross-sectional | Lung (47%), Colorectal (53%) | ≥ 20 y;76% Female;63% Spouse/Partner, 15% Child, 15% Parent/ Sibling, 7% Other | Acute | Social stressors Relationship quality Family functioning |

| Litzelman, 2016b (689*) | Cross-sectional | Lung (51%), Colorectal (49%) | ≥ 20 y; 79% Female; 62% Spouse/Partner, 15% Child, 15% Parent, 8% Other | Acute | Self-rated health Depressive symptoms |

| Mazanec, 2011 (70) *Majority treatment* | Cross-Sectional | Colorectal (15%), Gastrointestinal (6%), Gynecologic (28%), Lung (32%), Pancreas (16%), Other (4%) | 57 y; 70% Female; 63% Spouse, 16% Daughter, 4% Friend, 4% Sibling, 3% Partner, 1% Son, 9% Other | Cross-Listed | Self-rated health Depressive symptoms Anxiety Social support |

| Mezue, 2011 (117*) | Cross-sectional | Brain | Range: 23–85 y; 48% Female; 88% Spouse/Partner, 6% Offspring, 6% Other | Acute | HRQOL |

| Milbury, 2013 (158*) | Longitudinal | Lung | 61 y (range: 31–86 y);67% Female;100% Spouse | Acute | Psychological distress Social support |

| Morgan, 2011 (177*) *Acute, Middle-Long* | Cross-Sectional | Lung (26%), Head & neck (13%), Breast (11%), Colorectal (8%), Gynecological (7%), Hematologic (7%), Pancreatic (5%), Sarcoma (5%), Other (18%) | 56 y (range: 22–79 y); 58% Female; 100% Spouse/Partner | Cross-Listed | HRQOL POMS |

| Northouse, 2007 (263*) | Cross-Sectional | Prostate | 59 y; 100% Spouse | Cross-Listed | Relationship quality Psychological distress HRQOL |

| Parvataneni, 2011 (83*) | Cross-Sectional | Brain | Range: 23–78 y; 73% Female; 80% Spouse/Partner, 20% Other | Cross-Listed | Psychological distress |

| Pawl, 2013 (133*) | Cross-Sectional | Brain | 52 y (Range: 21–77 y); 69% Female; 75% Spouse/Significant other, 25% Other | Acute | HRQOL Depressive symptoms Spirituality Social support |

| Porter, 2008 (152*) | Correlational | Lung | 60 y; 67% Female; 76% Spouse, 14% Child, 8% Sister, Brother & Friend | Cross-Listed | Psychological distress |

| Porter, 2012 (127*) | Cross-Sectional | Lung | 63 y;62% Female;100% Spouse | Acute | Psychological distress |

| Prosser, 2015 (166) | Cross-Sectional | Not specified | ≥ 11 y; Child, Spouse, Parent | Cross-Listed | HRQOL |

| Ross, 2010 (89) *6–24 months post treatment* | Cross-Sectional | Head & Neck | 55 y (range: 33–85 y); 73% Female; 81% Spouse/Partner, 12% Child, 7% Sibling | Middle-Long | HRQOL |

| Shaffer, 2017 (275*) | Cross-Sectional | Lung (54 %), Non-Colorectal GI (pancreatic, hepatobiliary, esophageal, gastric) (46%) | 57 y (range: 19–86 y); 69% Female; Relative or Friend | Acute | HRQOL |

| Shahi, 2015 (131*) | Cross-Sectional | Brain, Head & Neck, Lung, GI, Other | 75% Spouse, 10% Child, 4% Significant other, 5% Parent, 2% Friend, 5% Other | Acute | HRQOL Mood state Spirituality Social support |

| Siefert, 2008 (54) | Cross-sectional | Gynecologic; Not Gynecologic | 55 y; 37% Female; 54% Spouse, 47% Not Spouse | Acute | HRQOL Depressive symptoms Social support |

| Spillers, 2008 (635) | Longitudinal | Breast (25%), Prostate (20%), Colorectal (13%), Lung (11%), Ovarian (7%), Kidney (6%), Other (each <5% bladder, skin, NHL, and uterine) | Range: 18–89 y 67% Female; 67% Spouse, 19% Child, 14% Other | Cross-Listed | HRQOL Psychological distress Social support |

| Sumner, 2015 (59) | Cross-Sectional | Breast | Community group: 37 y, clinic group 40 y;100% Female;Daughter or family member | Acute | Depressive symptoms Psychological distress Spirituality Social support |

| Tamayo, 2010 (194) | Cross-Sectional | Leukemia | 55 y (Range: 20–88 y); 76% Female; 80% Spouse, 11% Daughter, 9% Other | Acute | HRQOL |

| Trevino, 2015 (68) | Longitudinal | Not specified | 54 y; 77% Female; 46% Spouse/Partner, 54% Other | Bereavement | HRQOL |

| Washington, 2015 (139) | Cross-Sectional | Not specified | 59 y; 71% Female; 40% Child, 40% Spouse/ Partner, 21% Other | Bereavement | HRQOL Social support |

| Weaver, 2011 (637*) | Cross-Sectional | Lung (52%), Colorectal (48%) | ≥ 21 y; 79% Female; 58% Spouse, 42% Other | Acute | HRQOL Depressive symptoms |

| Winters-Stone, 2014 (59*) | Cross-Sectional | Prostate | 68 y; 100% Female; 100% Spouse | Middle-Long | Depressive symptoms |

| Wright, 2008 (332) | Prospective, longitudinal | Breast (12%), Colorectal (15%), Pancreatic (9%), Another GI (12%), Lung (23%), Other (30%) | 51y; 77% Female; 51% Spouse, 24% Child, 14% Other relative, 7% Friend, 4% Parent | Bereavement | HRQOL Psychiatric disorders |

| Wright, 2010 (333) | Prospective, longitudinal | Breast (12%), GI (38%), Lung (21%), Other (30%) | 51 y; 75% Female; 55% Spouse, 23% Child, 21% Other relative/ friend | Bereavement | HRQOL Psychiatric morbidities |

| Zhang, 2010 (171) | Cross-sectional (semi-structure questionnaire) | Lung | 56 y; 75% Female; 58% Spouse, 42% Child, Parents or Significant other | Acute | Depressive symptoms |

Sample size for cancer caregivers with valid/completed data

(indicates sample size includes patient-caregiver as dyads)

HRQOL = physical and mental health

HSW = heterosexual women

SMW = sexual minority women

FCR= Former caregivers-remission

FCB= Former caregivers-bereaved

CC=Current Caregivers

Protective buffering – a form of social support in which one dyad member attempts to minimize the stress of the situation for the other

HC=Husband cancer

WC=Wife Cancer

Major Findings

Overall, study findings identified poor cancer caregiver QoL across all phases of survivorship for physical and mental health, psychological distress, social support and spirituality (Table 2). Perceived physical and mental health were the most frequently examined QoL characteristics across all survivorship phases. Across the included studies, depression (Litzelman, Green, and Yabroff 2016, Weaver, Rowland, Augustson, and Atienza 2011, Winters-Stone, Lyons, Bennett, and Beer 2014, Wright et al. 2008, Wright et al. 2010), anxiety (Pawl et al. 2013, Deatrick et al. 2014, Washington et al. 2015, Kim, Carver, Spillers, Love-Ghaffari, and Kaw 2012), grief (Lichtenthal et al. 2011, Wright et al. 2010), and overall distress (Kim and Spillers 2010, Spillers et al. 2008, Northouse et al. 2007, Wright et al. 2008) were components of caregiver psychological functioning that impacted overall QoL. Some studies also reported the negative effects of suicidal ideation on overall QoL (Lichtenthal et al. 2011, Abbott, Prigerson, and Maciejewski 2014). The most common measures of psychological distress were depression (23 articles; 38%), anxiety (10 articles; 17%), and mood state (e.g., anxiety, depression, hostility) (6 articles; 10%). The role of social support and spirituality in relation to physical and mental health was only examined in the acute, bereavement and cross-listed phases. Spirituality and religion were described as protective factors or buffers that mediate or moderate the relationship between life stressors and QoL (Culliford 2002, Miller and Thoresen 2003).

TABLE 2.

METHODOLOGICAL AND SIGNIFICANT FINDINGS OVERVIEW OF INCLUDED STUDIES

| Author (year) | RECRUITMENT STRATEGY | SIGNIFICANT FNDINGSa |

|---|---|---|

| Abbott (2014) | Recruited as part of the Coping with Cancer (CwC) study, from 2002 to 2008 at seven comprehensive cancer centers across the U.S. | Caregivers’ perception of patients’ quality of life at the end of life, spousal relationship, and baseline suicidal ideation predicted suicidal ideation in bereavement. After adjusting for those variables, caregivers’ perception of patients’ quality of life at the end of life predicted suicidal ideation in bereavement. |

| Adams, (2014) | Recruited at least two days prior to scheduled move into American’s Cancer Society’s Hope Lodge houseb in Rochester, Minnesota. | At 4-month follow-up, lack of family support predicted lower levels of meaning in life and peace in multivariate general linear modeling analysis after controlling for caregiver age, gender, and education. |

| Boehmer (2016) | Recruited from May to July 2012, from an earlier comparative study of HSW and SMW (used cancer registry) and community-based (used Love/AVON Army of Women). | SMW were more likely to report greater support from friends and their significant other compared to HSW. Greater social support was related to decrease in fear of recurrence. Higher caregiver fear of recurrence increased survivor fear of recurrence. |

| Clark (2014) | Recruited from a randomized, two-group, controlled clinic trial. | Fatigue scores were below normal at baseline and at four-week follow-up. |

| Colgrove (2007) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors who participated in the ACS Study of Cancer Survivors who were identified by state cancer registries. | High levels of caregiver stress were associated with poorer mental and physical health. High levels of spirituality were associated with better mental health whereas the female gender was associated with poorer mental health. High levels of spirituality had a stress-buffering effect on better caregiver mental health and a stress-aggravating effect on poorer physical functioning. |

| Cooke (2011) | Convenience sample from two regional transplant programs on the west coast of the United States. | Predictability of caregiving was a predictor of QOL. |

| Deatrick (2014) | Recruited from a children’s hospital database and neuro-oncology and survivorship outpatient institutions in mid-Atlantic. | Caregiver and survivor health were moderately correlated. Better caregiver health predicted better caregiver perception about the manageability of the survivors’ condition. |

| Douglas, (2013) | Recruited from university cancer center from 2007 to 2010. | There was a consistent relationship between patient physical QOL and caregiver depression at baseline and three-months follow-up which was mediated by the patient’s spirituality. |

| Fletcher (2008) | Recruited from radiation therapy department in a comprehensive center and a community hospital. | Older age, lower levels of anxiety, higher levels of depression and morning fatigue predicted poorer caregiver functional status. Being younger, working, higher levels of depression, evening fatigue (p=.034) and sleep disturbance predicted poorer QOL. |

| Fujinami (2015) | Recruited from medical oncology adult ambulatory care clinic at an NCI-comprehensive cancer center. | Inadequate self-care and subjective stress burden were associated with high distress. Higher distress levels were associated with poorer physical, psychological, social, and spiritual QOL. |

| Garrido, (2014) | Recruited from outpatient clinics in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York and Texas 2002–2008. | Controlling for sociodemographic, better baseline mental health predicted lower incidence of depression/anxiety. Patients do not resuscitate (DNR) order and patient panic disorder predicted improved caregiver mental health. Patient quality of death and caregiver lower levels of depression/anxiety at baseline predicted improved HRQOL. |

| Gaugler (2008) | Recruited from radiation oncology clinics of a university-based cancer center in the northeastern USA from 2002 to 2005. | Employed female were more likely to indicate care-related fatigue and exhaustion when compared to employed male. |

| Grant (2013) | Recruited from medical oncology adult ambulatory care clinic at NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center in Southern California. | Decrease in caregiver psychological well-being, social well-being, spiritual well-being, physical well-being, and overall QOL in over a 24-week time period. |

| Harden (2013) | Not available. | There was a decrease in physical QOL from 24 to 36 months. Perceived bother related to patient sexual and hormone function, perceptions of stress, threat, and benefit associated with caregiving were predictors of QOL. Caregiver perceptions of threat and stress and perception of bother with hormone function were related to poor MH QOL. |

| Kershaw (2008) | Recruited from a randomized clinical trial. | Better mental QOL was associated with less avoidant coping, less negative appraisal of caregiving, and less baseline current concerns. Patients’ and spouses’ mental QOL were correlated. Less caregiver symptoms, more self-efficacy, and less concerns had indirect effects on caregiver mental quality of life through negative appraisal of caregiving. Better physical QOL was associated with fewer symptoms of their own and being younger. Less self-efficacy, less communication, more current concerns at baseline had more subsequent hopelessness and having a husband in later phase of illness (recurrent or advanced) had more psychological distress (hopelessness and uncertainty). |

| Kershaw (2015) | Recruited from a multisite randomized clinical trial. | Caregiver higher self-efficacy predicted better mental and physical health. Better caregiver and patient mental and physical health were associated with each other longitudinally. Higher patients’ self-efficacy predicted caregivers’ physical health. |

| Kim (2007a) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Daughters reported higher level of caregiving stress compared to sons and spouses. Caregivers that were highly stressed or cared for their parents (compared to spousal) reported greater levels of psychological distress, poorer mental functioning and spiritual adjustment. Highly stressed caregivers also had poorer physical functioning. Male caregivers (compared to female caregiver) and having higher caregiver esteem was associated with lower levels of psychological distress and better mental functioning. Higher caregiver esteem was also associated with better spiritual adjustment. |

| Kim (2007b) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Being younger, having lower income, not having gender-specific type of cancer, greater levels of caregiving stress, and lower levels of spirituality was associated with higher psychological distress. Higher levels of caregiving stress related to lower psychological distress among caregivers with high spirituality. The effect of low spirituality on higher psychological distress was stronger among the GTC- group than the GTC+ group. |

| Kim (2007c) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Using religion or spirituality to cope with caregiver stress and having greater social support was associated with greater benefit finding. Higher caregiving stress, poorer survivor mental functioning, lower levels of education, income, religious coping and social support were predictors of depressive symptoms. Lower levels of stress, caring for survivors with better mental and physical functioning, utilizing more religious coping and greater social support were predictors of caregiver life satisfaction. |

| Kim (2008a) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Spousal attachment anxiety was related to depression. Among husbands, there was a relationship between autonomous reasons for caregiving and lower depression while introjected motives for caregiving was associated with higher depression and less life satisfaction. Among wives, attachment anxiety was also related to less life satisfaction. |

| Kim (2008b) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Higher psychologically distressed was related to poorer physical and mental health. Older caregivers had poorer physical health. Caregiver distress was associated with worse survivor’s physical health and vice versa. Greater dissimilarity in psychological distress between the prostate cancer couple was associated with poorer mental health of wife-caregivers, while it was associated with better physical health for breast cancer husband-caregivers. |

| Kim (2008c) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Caregiver and survivors psychological distress predicted caregiver mental health. Older caregivers reported poorer physical health. |

| Kim (2010a) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Age, ethnicity, household income, and employment status were predictors of caregiver mental health. Age, gender, education, household income, employment and spousal status were predictors of physical health. Controlling for demographic factors: unmet psychosocial needs, financial needs and daily activity needs was related to poorer mental health; while only unmet financial needs was related to poorer physical health. |

| Kim (2010b) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Predictors of better mental health were: Older age, being a male and relatively affluent caregiver, and providing more frequent instrumental care. Also, caring for survivor who had less severe cancer and better mental and physical functioning. Predictors of better physical health were: Being younger, higher education levels, employed and relatively affluent caregivers, caring for non-spousal survivor who had higher physical functioning. Predictors of higher levels of psychological distress were: younger age, female gender, being less educated and less affluent. Also, being an active provider, caring for a relative with severe cancer, that had poorer mental and physical functioning, providing care to other family members (non-cancer patient) and providing less frequent instrumental care. Predictors of higher levels of spirituality: Older age, female gender, and caring for survivor better mental functioning. |

| Kim, (2011) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Older age and higher levels of spiritual well-being (specifically, finding meaning and peace) were predictors of reported better mental health. Older age and higher levels of faith were related to poorer physical health. Survivors higher levels of SWB (meaning and peace) was related to caregiver better physical health and caregiver higher levels of SWB (peace) was related to survivor better physical health. |

| Kim (2012a) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Current caregivers had poorer mental health compared to former caregivers. Predictors of mental health: All caregivers – older age and less stress FCRd – female gender, self-esteem, and less severe cancer FCBe – higher education CCf– non-spousal Predictors of physical health: All caregiver – younger age FCR – being employed and lower levels of earlier caregiving stress FCB – higher income CC – higher education, being spousal caregivers, and lower levels of earlier caregiving stress Bereaved and current caregivers reported higher levels of psychological distress compared to FCR. Predictors of psychological distress: All caregivers – younger age and higher levels of earlier caregiving stress FCB – lower education and income levels CC – being spousal caregiver FCR had higher levels of spirituality compared to FCB and CC. Predictors of Spirituality: All caregivers – older age FCR – female gender, being employed, lower levels of earlier caregiving stress, and higher levels of caregiving esteem FCB – higher education CC – higher levels of caregiver esteem |

| Kim (2012b) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Anxiety and fear of recurrence were predictors of poorer mental health. Anxiety and older age were predictor of poorer physical health. Greater patient cancer severity was a predictor of caregiver anxiety and fear of recurrence. Anxiety mediated the relationship between cancer severity and caregivers’ mental and physical health. |

| Kim (2014) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Bereaved caregivers had the highest prevalence of depression. Greater caregiving stress, less social support and being either an active or bereaved caregiver were predictors for depression. |

| Kim (2015a) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Older caregivers had poorer physical health. Greater levels of peace were strongly related to better mental health. Among women, having a patient with more severe cancer predicted poorer mental and physical health and greater caregiving stress predicted poorer physical health. Among men, autonomous motives for providing care were predictors for peace, meaning, and faith and greater faith was associated with poorer physical health. The relationship between autonomous reasons for caregiving and mental health was fully mediated by peace and partially mediated by meaning for men. |

| Kim (2015b) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Older age was correlated with physical impairments. Greater levels of stress were related to an increase risk for heart disease, arthritis, and chronic back pain. Spousal caregivers were more likely to develop arthritis and chronic pain. Bereaved caregivers were more likely to have arthritis and heart disease at the same time. |

| Kim, (2015c) | Caregivers were nominated by cancer survivors that participated in the Study of Cancer Survivors, who were identified by state cancer registries. | Older caregivers, depressive symptoms of caregiver and female patients, more comorbidity was related to poorer physical health. Caregiver depressive symptoms and greater male depressive symptoms was related to poorer mental health; while caregivers’ older age was related to better mental health. |

| Langer (2009) | Recruited from the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance. | Caregivers who felt bufferedc had lower relationship satisfaction and worse mental health. |

| Lichtenthal (2011) | Recruited as part of multi-institutional Coping with Cancer Study from 2005–2006. | Grief before the patient’s death was significantly associated with prolonged grief disorder. The presence of prolonged grief disorder was related with poorer overall HRQOL and mental health, lower levels of social functioning and energy, and suicidality. Discussing psychological concerns with a professional after the patients’ cancer diagnosis but before their death was associated with use of mental health services. |

| Litzelman (2015) | MEPS data, a household-based national sample from 2004 and 2012. | Regardless of gender, better patient physical and mental health was associated with better caregiver physical and mental health. Depressed mood of husband-patient was associated with wife-caregiver worse physical health. Depressed mood of wives-caregivers was associated with worse husband-patient mental and physical health; while depressed mood of husbands-caregivers was associated with worse wife-patient mental health. |

| Litzelman (2016a) | Part of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) consortium which recruited five cancer registry sites and two health care system sites. | Older age caregivers (>50 years) reported less social stress and better family functioning but had worse relationship quality. Caregivers of spouse/partner reported worse relationship quality and caregivers of a family member or friend reported better family functioning. Caring for female patient was associated with less social stress, better relationship quality but worse family functioning. After controlling for sociodemographic, cancer and caregiving characteristics having a good current relationship quality and family functioning was associated with less social stress. |

| Litzelman (2016B) | Part of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) consortium which recruited from seven sites between 2003 and 2006. | Higher caregiver depressive symptoms were associated with an increased likelihood that patients would report poor quality of care. |

| Mazanec (2011) | Convenience sample recruited from a palliative care clinical trial at a Midwestern NCI-Comprehensive Cancer Center from 2009 to 2010. | Greater physical activity was associated with male gender, better health ratings, low perceptions of burden related to family support and health problems. Higher levels of anxiety among caregivers was associated with greater work productivity loss. Greater activity impairment was associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression, lack of family and less social support, and with greater perceived caregiver burden related to financial and health problems. |

| Mezue (2011) | Recruited from hospital in hull royal informatory in 2015. | Caregivers ability to cope positively correlates with caregiver’s mental quality of life and with their psychological morbidity. |

| Milbury (2013) | Recruited during appointments in the Thoracic clinic. | Higher caregiving burden, low levels of caregiving esteem, higher number of health problems and financial strain at baseline, and a lack of family support predicted higher levels of distress. |

| Morgan (2011) | Recruited during outpatient appointments at cancer center. | Greater levels of coping style, better relationship quality, less financial concerns, and patient QOL predicted better QOL. |

| Northouse (2007) | Recruited from three cancer centers in the Midwest. | Newly diagnosed dyads reported better QOL across all dimensions than all other dyads; while spouses of advanced dyads had the lowest emotional QOL and highest risk for distress. Across all phases of illness, spouses reported less self-efficacy and social support in managing the effects of prostate cancer compared with patients. |

| Parvataneni (2011) | Recruited from Neuro-Oncology clinic at the University of California, San Francisco. | Females caregivers placed higher importance on obtaining support to deal with their anxiety and stress, compared to male caregivers. |

| Pawl (2013) | Recruited from urban tertiary medical center in the eastern U.S. between 2005 and 2011. | Less comorbidities and older age were predictors of physical health and of IL-1ra and IL-6 level. Sleep quality and gender were predictors of QOL. Fatigue and spirituality were negatively correlated with anxiety. Depressive symptoms were positively correlated with anxiety. Sleep quality was a predictor of social support. |

| Porter (2008) | Recruited from larger program between 2002 and 2005. | Caregivers and patient high self-efficacy was associated with lower levels of mood disturbance and caregiver strain. |

| Porter (2012) | Recruited from Duke Thoracic Oncology program and community oncology clinics in North Carolina. | Spouses high in avoidant attachment, had lower levels of marital quality, higher levels of caregiver strain, anger and depression. Spouses high in anxious attachment had higher levels of anxiety. |

| Prosser (2015) | Recruited using an internet panel between 2011 and 2012. | Survivors HRQOL effects caregivers HRQOL. |

| Ross (2010) | Not available. | Greater hours spent caregiving was correlated with poorer mental wellbeing and worse psychological well-being. Spouses and partners reported worse financial well-being than other caregivers. |

| Shaffer (2016) | Recruited from the outpatient clinics at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center from 2011 to 2015. | Being young, female, the survivors spouse, and caring for a patient with poor emotional well-being were risk factors for caregiver poor mental health. In the final model, only caregiver younger age and being the patients’ spouse remained were related to worse caregiver mental health. Being older, having low education attainment, and caring for patients reporting low social well-being were risk factors for caregiver poor physical health. |

| Shahi (2015) | Part of randomized control trial. | Caregiver QOL was influenced by the patient age, existence of head & neck tumor site, and mood state. Caregivers of older survivors (>65 years) reported better mental, emotional, spiritual, social support, QOL, and mood well-being. |

| Siefert (2008) | Recruitment from a large academic urban cancer treatment center and a larger home intervention between 2004 and 2006. | Regardless of gender, spousal caregivers reported less burden related to family support. Being a female caregiver and longer time caregiving was associated with worse functionality (QOL) while working full-or part-time was associated with higher QOL. African American and Hispanic caregivers were more likely to express depressive symptoms, report an increase burden related to lack of family support, and the impact caregiving had on their finances than Caucasian caregivers. |

| Spillers | Not available. | Caregivers who were older, employed, currently providing care, cared for survivor with poor QoL, and had greater guilt feelings were more likely to report poorer physical functioning. Being female caregiver, younger age, currently providing care, reporting lack of family support, impact on schedule, caregiver competence, caring for survivor with higher levels of mental/social functioning, and having greater guilt feelings was associated with caregiver mental health. Being a female and younger caregiver and having greater guilt feelings were more likely to report higher levels of psychological distress. |

| Sumner (2015) | Recruited from UCLA High Risk Clinic and also included participants from the American Cancer Society’s National Quality of life Survey (recruited based on patients’ nomination). | Clinic caregiver reported higher emotional and tangible support than the community caregiver sample. The community sample had higher scores in spirituality (faith, meaning, and peace) than the clinic sample. |

| Tamayo (2010) | Recruited from ambulatory treatment center from comprehensive cancer center in southern U.S. | No bivariate or multivariate analysis conducted |

| Trevino (2015) | Recruited from four different sites from 2002 to 2008. | Caregiver emotional well-being was correlated with mental health. Strong patient oncologist therapeutic alliance was associated with better mental and general HRQoL, and better social function and emotional well-being. Controlling for baseline HRQoL and confounding factors: Strong patient-oncologist therapeutic alliance was a predictor for better mental health and well-being post loss. |

| Washington (2015) | Recruited from two community hospice agencies in the US Pacific northwestern region between 2011 and 2014. | Co-residing cancer caregivers reported greater financial, physical, and overall quality of life compared with non-cancer caregivers. |

| Weaver (2011) | Part of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) consortium which recruited five cancer registry sites and two health care system sites between 2004 and 2005. | Controlling for socio-demographic and cancer specific characteristics: Colorectal cancer caregivers who smoked reported greater depression and greater anxiety while lung cancer caregivers that smoked reported greater anxiety. Colorectal caregivers who smoked, when their patients did not report worse physical QOL. Colorectal cancer caregivers in mismatched dyads reported greater depression and anxiety scores compared to nonsmoking dyads. Lung cancer caregivers in mismatched dyads reported greater anxiety scores compared to nonsmoking dyads. Both lung and colorectal caregivers in dyads where one or both members continued to smoke, reported worse MH QOL compared to non-smoking dyads. Lung cancer caregivers whose care recipient continued to smoke reported greater financial strain due to caregiving. |

| Winters-stone (2014) | Recruited to participate in a randomized trial. | Time since diagnosis and caregiver strain were positively correlated with depressive symptoms. Prostate cancer survivors (PCS) and spouse depressive symptoms were moderately correlated. PCS symptom severity as reported by PCS and spouse was correlated with spouse depressive symptoms. |

| Wright (2008) | Recruited from seven outpatient sites between 2002 and 2008. | Controlling for sociodemographic and baseline QOL: Caregivers of patients who received any aggressive care were at higher risk for developing a Major Depressive Disorder, experiencing regret, and feeling unprepared for the patient’s death, compared to caregivers of patients who did not receive aggressive care. They also had overall worse QOL, self-reported health, and increased role limitations. High patient QOL was associated with better caregiver overall QOL, self-reported health, physical functioning, mental health, and improvements in self-rated change in health. |

| Wright (2010) | Recruited from seven outpatient sites between 2002 and 2008. | Controlling for baseline psychiatric illness and cofounders: Bereaved caregivers of patients who died in ICU had a heightened risk for PTSD compared with caregivers of patients who died with home hospice. Bereaved caregivers of patients who died in hospital had heightened risk for prolonged grief disorder, compared with home hospice deaths. |

| Zhang (2010) | Recruited at Comprehensive Cancer Center, Clinic, and medical center between 2001 and 2004. | Fewer family members being informed about treatment and care decisions, exclusion of any family member in decision-making, doctor’s recommending a treatment that was unwanted by either patient or caregiver, caregivers preference to stop a treatment, and less willingness to discuss hospice care at home were predictors of depression. |

N=60 studies.

Based on bivariate and multivariate analyses in the final model; results not listed were nonsignificant.

ACS’s Hope Lodge house (free stay if patient is undergoing outpatient cancer treatment at least three times weekly and reside greater than 40 miles away from cancer treatment facility)

Protective buffering – a form of social support in which one dyad member attempts to minimize the stress of the situation for the other

FCR= Former caregivers-remission

FCB= Former caregivers-bereaved

CC=Current Caregivers

Acute Phase (Diagnosis through active treatment).

Most acute phase studies reported poor caregiver QoL, including physical and mental health constructs. Factors associated with poor caregiver physical health including low education attainment (Shaffer et al. 2017), having any comorbidities (Pawl et al. 2013, Kim, van Ryn, et al. 2015), being female (Siefert et al. 2008), reported history of depressive symptoms (Kim, van Ryn, et al. 2015), caring for a female patient (Kim, van Ryn, et al. 2015), and caring for patients with low reported social well-being (Shaffer et al. 2017). Partner effects were also found to impact caregivers’ mental and physical health. Among lung and colorectal cancer patient-caregiver dyads, where one or both members reported being current smokers, smoking was associated with poorer caregiver mental and physical health (Weaver et al. 2011). Caregivers experienced increased depressive symptoms and poorer mental health if they were the patients’ spouse (Shaffer et al. 2017), cared for a male patient that demonstrated depressive symptoms (Kim, van Ryn, et al. 2015), or cared for patients with self-reported poor QoL. Concealing concerns about the patient’s cancer diagnosis, was negatively associated with relationship satisfaction (Hagedoorn et al. 2000) and the mental health for both patients and caregivers (Langer, Brown, and Syrjala 2009).

Factors that were positively associated with higher overall QoL among caregivers included predictability pertaining to caregiver routine (Cooke et al. 2011), caregiver sleep quality (Pawl et al. 2013), and working full-or-part time (Siefert et al. 2008). Caregiver and/or patient self-efficacy or perceived ability to manage the illness was also related to better caregiver physical health (Kershaw et al. 2015). Compared with younger cancer patients, caring for an older patient was associated with higher levels of mental and emotional well-being (Shahi et al. 2014).

Psychological distress.

Depression was found to negatively impact caregiver mental and physical health and overall QoL (Kim, van Ryn, et al. 2015). Studies found that depression impacted caregivers’ functional status and QoL (Fletcher et al. 2008) and was positively correlated with anxiety (Pawl et al. 2013). Higher depression scores in caregivers of survivors being seen in clinical treatment settings were associated with family disagreement about treatment recommendations from doctors and discussions regarding transitioning from active cancer treatment to hospice care (Zhang, Zyzanski, and Siminoff 2010). Among spousal cancer caregivers, those who were high in avoidant attachment (less sensitive and responsive to their partner’s needs) reported higher levels of caregiver strain, anger, and depression; while those who were high in anxious attachment (tendency to engage in overinvolved and controlling forms of caregiving) reported higher levels of anxiety (Porter, Keefe, Davis, Scipio, and Garst 2012). Among those with advanced cancer, patients’ physical health had a direct effect on caregiver depression with caregivers reporting higher levels of depression concomitant with the decline in patients’ physical health (Douglas and Daly 2013).

A sub-set of the studies (N=9) examined caregivers’ anxiety (Fletcher et al. 2008, Mezue et al. 2011, Pawl et al. 2013, Porter et al. 2012, Weaver et al. 2011) and mood state (anxiety, depression, hostility) (Douglas and Daly 2013, Gaugler et al. 2008, Porter et al. 2012, Shahi et al. 2014) in the acute phase. Among caregivers of head and neck cancer survivors, the patient mood state influenced caregivers’ overall QoL(Shahi et al. 2014). Colorectal and lung cancer caregivers who smoked or were in mismatched dyads (where either cancer patient or caregiver smoked) reported greater anxiety (Weaver et al. 2011). Caregiving burden (i.e., lack of family support, financial strain, schedule disruptions, and health problems) was positively associated with distress (Milbury et al. 2013). Better relationship quality, family function and caring for a female patient was associated with less stress (Litzelman, Kent, and Rowland 2016).

Social Support.

Perceived social support was related to caregivers and cancer survivor’s QoL. Caregivers that reported high levels of social support were caring for older patients (>65 years) (Shahi et al. 2014) and patients treated in clinical (vs. community settings) (Sumner et al. 2015). Lower levels of caregiver social support were associated with lower levels of spirituality (Adams et al. 2014), increased fatigue and lack of sleep (Pawl et al. 2013), and distress between spouses (Milbury et al. 2013). Differences by race/ethnicity were noted in one study, where African American and Hispanic caregivers reporting an increased QoL burden related to a lack of family support and the impact that caregiving had on their finances (Siefert et al. 2008).

Social well-being, including the overall perception of relationship quality, was a less explored domain of QoL. Caregivers responsible for a spouse or partner reported worse mental health (Shaffer et al. 2017) and relationship quality than those who cared for other family members (not spouse/partner) or friends reported better family functioning (Litzelman, Kent, and Rowland 2016). Spousal caregivers high in avoidant attachment characteristics reported significantly lower levels of marital quality (Porter et al. 2012). Regardless of the gender of the caregiver, the type of relationship between caregiver and the care recipient, and other elements of the caregiving relationship, caring for a female patient was also associated with better relationship quality but worse family functioning (Litzelman, Kent, and Rowland 2016).

Spirituality.

Patient spiritual well-being mediated the relationship between patient physical health and caregiver depression (Douglas and Daly 2013). Findings from this study suggest that a low-level of spiritual well-being in patients may be a risk factor for depression among caregivers. Higher levels of spirituality were also positively correlated with sleep quality and negatively with anxiety among caregivers (Pawl et al. 2013). Caregivers of older cancer patients who reported higher QoL reported higher levels of spiritual well-being (Shahi et al. 2014).

Middle to Long-term Phase (Post-treatment care).

Among the middle to long-term phase survivorship studies, caregivers’ QoL was related to survivor health (Deatrick et al. 2014) and caregiver perceptions of stress, threat and benefit associated with caregiving (Harden et al. 2013). No studies were identified that examined social support and spirituality. One study identified a positive reciprocal relationship with higher survivor QoL equating to better caregiver QoL (Deatrick et al. 2014). Perceived stressfulness and lack of perceived benefit associated with caregiving were found to negatively affect caregivers’ QoL over time and impact intimacy between spousal caregivers and prostate cancer survivors (Harden et al. 2013).

Psychological distress.

Middle to long-term phase studies examined depression, anxiety, and stress related to QoL. Studies examining prostate cancer caregivers found that patient symptom severity was correlated with caregiver depression (Winters-Stone et al. 2014) and perceived caregiver stress was also a predictor for caregivers overall QoL and mental health (Harden et al. 2013). Among caregivers of brain cancer survivors, better caregiver health, including both lower psychological distress and higher QoL, was associated with fewer perceived caregiver demands and better family functioning (Deatrick et al. 2014). Additionally, among caregivers of head and neck cancer survivors, increased time spent caregiving was also associated with worse psychological well-being (Ross et al. 2010).

End of life/ Bereavement Phase.

Bereavement phase studies reported that good caregiver mental and physical health was associated with several patient characteristics and outcomes including: high patient QoL (Wright et al. 2008), strong patient relationship with doctors (Trevino et al. 2015), and better patient quality of end of life experience (caregivers or clinicians assessed patients QoL in week before death) (Garrido and Prigerson 2014). A patient’s death in a hospital (versus home) (Garrido and Prigerson 2014), presence of prolonged grief disorder (Lichtenthal et al. 2011), and caring for a patient who received any aggressive care (Wright et al. 2008) were associated with poor caregiver QoL outcomes. Among informal hospice caregivers, cancer caregivers were more likely to co-reside (live in the same house) with the patient and this resulted in better overall QoL compared with co-residing non-cancer caregivers (Washington et al. 2015). Similarly, caregivers reported better mental health outcomes when they perceived that their loved ones with cancer experienced less pain upon death and had a completed “do not resuscitate” (DNR) order (Garrido and Prigerson 2014).

Psychological distress.

The majority of the studies classified in the bereavement phase examined QoL outcomes related to psychological distress including depression (Garrido and Prigerson 2014, Lichtenthal et al. 2011, Wright et al. 2008, Wright et al. 2010), grief (Lichtenthal et al. 2011, Wright et al. 2010), anxiety (Washington et al. 2015), overall distress (Wright et al. 2008), and suicidal ideation (Abbott, Prigerson, and Maciejewski 2014, Lichtenthal et al. 2011). Some of the risk factors for poor QoL among caregivers in this phase included married caregivers negative perception of patients’ QoL and impact on spousal relationship (Abbott, Prigerson, and Maciejewski 2014), quality of death (Garrido and Prigerson 2014), patient receiving aggressive care at the end of life (Wright et al. 2008), location of death (hospital vs. home hospice) and pre-existing self-reported psychiatric morbidities among caregivers (Wright et al. 2010). The presence of prolonged grief disorder (Lichtenthal et al. 2011) and caregivers’ negative perception of patients’ QoL at end of life (Abbott, Prigerson, and Maciejewski 2014) was associated with suicidal thoughts or gestures among bereaved caregivers. Bereaved caregivers of patients who died in a hospital ICU were more likely to experience a heightened risk for prolonged grief disorder, compared with home hospice deaths (Wright et al. 2010).

Social Support and Spirituality.

Three studies examined caregivers’ social support (Washington et al. 2015, Wright et al. 2010) and religious coping style (Garrido and Prigerson 2014, Wright et al. 2010). There was no significant difference in levels of support among bereaved cancer and non-cancer caregivers (Washington et al. 2015) and caregivers who cared for a patient who died at home versus at the hospital (Wright et al. 2010). These studies also found no association between social support and religious coping style with caregiver physical or mental health.

Cross-Listed Studies (Multiple phases or studies lacking phase distinction).

Among studies which examined caregiving across multiple phases of the survivorship experience, age (Kim, Wellisch, and Spillers 2008, Kim et al. 2010, Kim and Spillers 2010, Spillers et al. 2008, Shaffer et al. 2017), gender (Kim, Baker, and Spillers 2007, Kim and Spillers 2010, Kim, Spillers, and Hall 2012, Kim, Carver, and Cannady 2015, Litzelman, Green, and Yabroff 2016, Spillers et al. 2008), duration of caregiving responsibilities (Ross et al. 2010), and caregiver guilt (Spillers et al. 2008) were predictors of physical and mental health. Older caregivers reported better mental health (Kim, van Ryn, et al. 2015, Shahi et al. 2014, Shaffer et al. 2017) but worse physical health (Kim and Spillers 2010, Kim, Spillers, and Hall 2012, Kim et al. 2012, Kim, Wellisch, and Spillers 2008, Kim, Carver, Spillers, Crammer, and Zhou 2011, Kershaw et al. 2008, Shaffer et al. 2017). Male caregivers reported lower levels of psychological distress and better mental functioning (Kim, Baker, and Spillers. 2007), whereas female gender was associated with poorer mental health for caregivers (Colgrove, Kim, and Thompson 2007). Other factors associated with QoL included; unmet psychosocial needs (resulting in poorer mental health) and unmet financial needs (resulting in poorer mental and physical health) (Kim et al. 2010). Across phases, caregivers’ perceived ability to cope with caregiving demands and responsibilities, was also correlated with better mental health (Mezue et al. 2011) and physical health (Kershaw et al. 2008, Kershaw et al. 2015). Studies also found a reciprocal relationship between patients and spouses’ mental health across multiple phases and spousal caregivers’ had better mental health when they used less avoidant coping strategies (e.g., denial, self-distraction, and behavioral disengagement) (Kershaw et al. 2008, Kershaw et al. 2015).

Negative appraisal of caregiving was associated with worse mental health outcomes among spouses of prostate cancer survivors across several phases (Harden et al. 2013, Kershaw et al. 2008). Caregiver-patient dyads coping with advanced stages of prostate cancer who had clinical evidence of metastatic disease at diagnosis or experienced a progression of the disease during treatment had poorer physical, emotional, functional, and total QoL compared with newly diagnosed earlier stage dyads (Northouse et al. 2007). Long-term caregivers, at 5-years post-diagnosis, reported poorer mental health than caregivers of survivors who had gone into remission and bereaved caregivers (Kim, Spillers, and Hall 2012).

Numerous studies demonstrated that caregiver-patient dyads may be particularly vulnerable to QoL spillover effects (Litzelman, Green, and Yabroff 2016, Prosser et al. 2015) in which the patient’s health condition can have implications on the caregiver health outcomes (Kim et al. 2012, Kim et al. 2011, Kim, Kashy et al. 2008, Litzelman, Green, and Yabroff 2016, Prosser et al. 2015). For example, some studies found that greater patient psychological distress was related to poorer caregiver physical health (Kim, Kashy et al. 2008, Kim, Wellisch, and Spillers 2008). Better patient physical and mental health was also associated with better caregiver physical and mental health; while worse depressed mood among patients was associated with worse physical health among caregivers (Litzelman, Green, and Yabroff 2016). However, there were some differences by gender in one study. Patient psychological distress was associated with poorer mental health for wife caregivers of prostate cancer survivors but better physical health for husbands of breast cancer survivors (Kim, Kashy et al. 2008).

Psychological distress.

Approximately one-third of cross-listed studies examined overall caregivers’ psychological distress. Higher levels of distress and resultant lower QoL were associated with younger age (Kim and Spillers 2010, Kim, Spillers, and Hall 2012, Kim, Wellisch, Spillers, and Crammer 2007, Spillers et al. 2008), female gender (Kim and Spillers 2010, Spillers et al. 2008), lower income (Kim and Spillers 2010, Kim, Spillers, and Hall 2012, Kim, Wellisch, Spillers, and Crammer 2007), greater levels of stress (Kim, Baker, and Spillers 2007, Kim, Spillers, and Hall 2012, Fujinami et al. 2015), inadequate self-care (Fujinami et al. 2015), lower levels of caregiving self-esteem (the extent to which caregiving imparts individual self-esteem) (Milbury et al. 2013, Kim, Baker, and Spillers 2007), and lower levels of spirituality Kim, Wellisch, Spillers, and Crammer 2007). Caregivers with higher levels of psychological distress had poorer physical health (Colgrove 2007, Kim, Kashy et al. 2008, Kim, Baker, and Spillers 2007), suboptimal mental health (Kim, Kashy et al. 2008, Kim, Spillers, and Hall 2012, Kim, Wellisch, and Spillers 2008), more depressive symptoms (Kim, Shaffer, Carver, and Cannady 2014, Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007), and greater physical impairments (Kim, Carver, et al. 2015). Adult children caregivers reported higher levels of psychological distress and lower levels of mental function compared to spousal caregivers; however, daughters reported the highest level of caregiving stress compared to sons and spouses (Kim, Baker, and Spillers 2007). Factors associated with other psychological distress outcomes such as depression and anxiety included lower levels of education (Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007), lower income (Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007), greater caregiving stress (Kim et al. 2014, Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007), poorer care recipient mental function (Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007), cancer severity (Kim et al. 2012), limited social support (Kim et al. 2014, Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007), and lack of religious coping (Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007). Caregivers and/or patients with high self-efficacy for managing illness symptoms had lower reported levels of mood disturbance (e.g., anxiety, depression, hostility) (Porter et al. 2008). Bereaved caregivers and long-term caregivers reported higher levels of psychological distress (Kim, Spillers, and Hall 2012) and elevated depressive symptoms (Kim et al. 2014). Spousal caregivers attachment style impacted their psychological adjustment as it was found that anxiously attached caregivers had introjected motives (i.e., feeling guilty or ashamed if they did not provide care) and more depression, which was stronger for wives than for husbands (Kim, Carver, Deci, and Kasser 2008). Female and younger caregivers were more likely to report higher levels of psychological distress (Spillers et al. 2008).

Social Support.

In the cross-listed studies, lack of social support was related to caregiving stress (Kim et al. 2014, Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007) and elevated depression or depressive symptoms (Kim et al. 2014, Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007, Spillers et al. 2008). Lack of social support was also related to caregiver difficulties in managing the effects of cancer (Northouse et al. 2007). Caregivers with greater social support were more likely to report greater benefit finding in caregiving (e.g., personal growth or positive changes from the challenges of dealing with cancer in a loved one) and life satisfaction (Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007) and decreased fear of recurrence, or worry and cancer about cancer recurrence (Boehmer et al. 2016). Compared to male caregivers, females caregivers placed a higher importance on obtaining support to deal with their anxiety and stress (Parvataneni et al. 2011). Furthermore, male caregivers had fewer health problems when they had lower perceived burden due to a perception of higher family support (Mazanec et al. 2011). Different sources of social support were found among caregivers-patient dyads in one study of breast cancer survivors based on their sexual orientation, where sexual minority caregivers (women report being lesbian, bisexual, or have a preference for a female partner) reported greater support from significant others and friends than heterosexual caregivers (Boehmer et al. 2016).

Spirituality.

In cross-listed studies, there was a positive reciprocal relationship with higher levels of spiritual well-being among survivors or caregivers equating to better physical health (Kim et al. 2011) and mental health (Colgrove 2007, Kim et al. 2007) of their caregivers or survivors (Douglas and Daly 2013). Factors associated with higher levels of spirituality include older age (Kim, Spillers, and Hall 2012), female gender, caring for patient with better mental functioning (Kim and Spillers 2010), and caring for a survivor with a non-gender specific type of cancer (Kim, Wellisch, Spillers, and Crammer 2007). Overall, spirituality was positively associated with mental health (Colgrove 2007, Kim, Carver, and Cannady 2015, Kim et al. 2011, Kim and Spillers 2010). High levels of spirituality buffered the adverse impact of caregiving stress on the caregivers’ mental health but had the opposite effect on physical functioning (Colgrove 2007). Family members who used spirituality to cope with the stress and were more likely to report greater benefit finding and life satisfaction (Kim, Schulz, and Carver 2007). Whereas, poor spiritual adjustment, which was measured by the degree to which caregivers reported finding meaning/peace and faith, was related to higher levels of caregiving stress (Kim, Baker, and Spillers 2007). However, among highly spiritual female caregivers, higher levels of stress were related to lower psychological distress, which supports the stress-buffering hypothesis of spirituality (Kim, Wellisch, Spillers, and Crammer 2007). Other studies found that higher levels of faith were related to poorer physical health (Kim et al. 2011) and that caregiving stress was associated with poorer physical functioning among caregivers with a high level of spirituality (Colgrove 2007). Differences by caregiver relationship to patient were noted, where adult children caregiver reported the lowest spiritual adjustment (Kim, Baker, and Spillers 2007). Caregivers of survivors who had gone into remission had higher levels of spirituality and bereaved and long-term caregivers had more difficulties with spiritual adjustment (Kim, Spillers, and Hall 2012).

DISCUSSION