Abstract

H2S is a toxic and corrosive gas, whose accurate detection at sub-ppm concentrations is of high practical importance in environmental, industrial, and health safety applications. Herein, we propose a chemiresistive sensor device that applies a composite of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and brominated fullerene (C60Br24) as a sensing component, which is capable of detecting 50 ppb H2S even at room temperature with an excellent response of 1.75% in a selective manner. In contrast, a poor gas response of pristine C60-based composites was found in control measurements. The experimental results are complemented by density functional theory calculations showing that C60Br24 in contact with SWCNTs induces localized hole doping in the nanotubes, which is increased further when H2S adsorbs on C60Br24 but decreases in the regions, where direct adsorption of H2S on the nanotubes takes place due to electron doping from the analyte. Accordingly, the heterogeneous chemical environment in the composite results in spatial fluctuations of hole density upon gas adsorption, hence influencing carrier transport and thus giving rise to chemiresistive sensing.

Keywords: H2S gas sensor, ppb, brominated fullerene, C60Br24/SWCNT composite, carrier doping

1. Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a corrosive, toxic, and colorless gas, which accompanies several industrial and natural processes, and may pose health risks upon extended exposure even at sub-ppm concentrations. The acceptable ambient concentration of H2S for humans shall be below 100 ppb.1 On the other hand, as a biomarker, the detection of H2S has also been applied in the early diagnosis of lung diseases.2,3 Therefore, sensors that can detect H2S rapidly and selectively at the ppb level are of great significance. In recent years, H2S sensors with different detection modalities have been developed, including chemiresistive,4,5 electrochemical,6,7 and surface acoustic wave devices.8−10 Among these, chemiresistive sensors have attracted great attention due to their remarkable advantages including low cost, simple fabrication and operation, high response, and easy integration with electronics.11−13

A typical chemiresistive sensor is composed of electrodes (either coplanar or interdigitated) defined on a substrate and a sensing material layer that bridges the gap between them. The resistance of chemiresistive gas sensors changes in the presence of gases and the magnitude of change is related to the gas concentration as well as to the strength of gas–surface interactions. The change of resistance is a consequence of (partial) electron transfer or polarization in the sensing material induced by the adsorbed molecules. Typically, the effect on the conductivity is high when the interaction is strong, for example, upon the adsorption of molecules with highly reducing or oxidizing properties, which may facilitate strong dipole attraction or bonds with ionic or covalent character.14−17 The drawback of such strong interactions is the poor reversibility, that is, after gas exposure, the analyte cannot desorb quickly, thus compromising sensor recovery. Conversely, weak interactions (e.g., by dispersion forces) generally accompany only small charge transfer between the sensing material and the analyte, which results in minute changes in the carrier concentration and thus a small sensory signal, although often with good desorption and sensor recovery.18−20 Hence, it is a plausible strategy to find a medium interaction strength between analytes and sensing materials to ensure optimal sensing performance of chemiresistive gas sensors. While several studies have dealt with optimizing the interaction between analytes and sensing materials,14−16 halogen bonding has not received the attention it deserves, despite having similar characters to hydrogen bonding exploited widely for gas sensing due to its moderate strength.17−20

In the last few decades, a variety of materials including semiconducting metal oxides, transition metal sulfides, carbon nanomaterials, conducting polymers and organic materials, and their composites were explored for the detection of H2S gas at low concentrations.21−25 While semiconducting metal oxide-based sensors show good sensitivity, their typical major limitations are high operating temperatures and poor selectivity. In the case of organic semiconducting sensors, their poor conductivity, which originates from the charge-hopping mechanism, limits the overall performance.26 Therefore, current efforts aim at combining several different functional materials together to simultaneously address challenges related to good electrical conductivity and gas-sensing capability at room temperature.27−31

In this work, we report on nanocomposites of brominated fullerene (C60Br24) and single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) as promising sensing media, which were immobilized on interdigital electrodes of chips using a simple brush-coating method to obtain chemiresistive sensor devices. The sensor exhibits a high response, good repeatability, and selectivity for H2S with a measured detection limit of a 25 ppb concentration. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicate that adsorption of H2S on C60Br24 has a medium bond strength and it increases the hole density in CNTs near the contact. On the other hand, direct adsorption of H2S on SWCNTs causes electron doping and thus results in a spatial fluctuation of the carrier concentration along the nanotubes giving rise to local barriers and scattering centers that limit carrier transport therein. Accordingly, our study shows a feasible approach to sensitize CNTs with halogenated carbon nanomaterials having ideal properties for gas-sensing applications.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Materials Properties

C60Br24 was synthesized by the reaction of fullerene (C60) with the Br2 liquid in the presence of a FeBr3 catalyst at room temperature as described earlier by Djordjević and co-workers.32 Composites of C60Br24/SWCNTs were prepared by blending C60Br24 with SWCNTs in different mass ratios. Scanning and transmission electron microscopy images (Figure 1a,b) show good uniformity of fullerenes on the nanotubes. Peaks in the Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum of C60Br24 (Figure 1c) are nearly identical to those reported earlier.33 Peaks at 603 and 545 cm–1 originate from radial motions of carbon skeletons partially localized on the functionalized fragments of C60Br24. The peak at 848 cm–1 is due to C=C–Br–C and C=C–Br deformations. The peaks at 1118 and 1224 cm–1 indicate the C–C–Br and C–C stretching vibrations, respectively.34−36 In addition, compounding C60Br24 with SWCNTs does not seem to change the chemical structure according to the FTIR spectrum of C60Br24 in the C60Br24/SWCNT composite. To get further insights into the chemistry of the brominated fullerenes, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was carried out. The Br 3d peak (Figure 1d) can be deconvoluted into two peaks corresponding to two components with energies typical for covalent C–Br bonds.37 The Raman spectrum of C60Br24 is very similar to that of C60 (Figure S1a). The X-ray diffraction pattern of C60Br24 (Figure S1b) is consistent with the literature32 and shows a series of additional reflections compared to pristine C60 indicating that packing of the crystals is different after bromination. The presence of side groups leading to a less dense packing38 is supported by the lower intensity and a shift of the main reflections to lower angles, when comparing the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of C60Br24 to that of pristine C60. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of C60Br24 indicates its high thermal stability with an onset of 5% weight loss at 151 °C (Figure S1c).

Figure 1.

(a) SEM and (b) TEM images of C60Br24; (c) FTIR spectra of C60Br24, C60, and the C60Br24/SWCNT composite; and (d) resolved XPS Br 3d peak of C60Br24.

2.2. Gas-Sensing Behavior

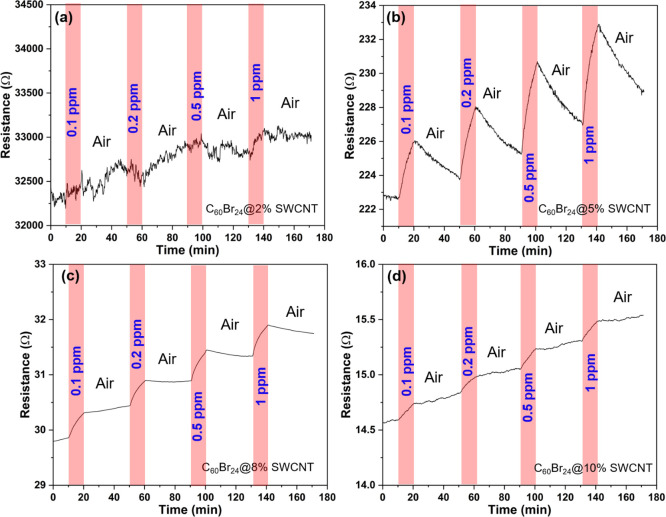

C60Br24/SWCNT composites having different nanotube loadings (from 2 to 10 wt %) were prepared and then deposited onto ceramic chips having printed Ag–Pd interdigital electrodes to find the optimum composition for H2S detection (Figure 2). The high conductance and the fairly linear I–V characteristics of the fabricated sensors indicate good percolation of the metallic SWCNTs in the network and suggest ohmic contact between the sensing film and the electrodes (Figure S2). At SWCNT concentrations of 5% or higher, the resistance of the sensor devices is well below 1 kΩ and the noise of the real-time response curves is visibly low in contrast to the composite with a 2% SWCNT content. Although the composites with 8 and 10 wt % nanotube contents have a lower resistance than that with a 5 wt % composite, the sensor response of those devices is clearly inferior, which is due to the highly percolated metallic SWCNTs in the network, which practically shunt the semiconducting elements and junctions (that eventually play the main role in sensing with SWCNTs).39 As expected, in the extreme condition of having only SWCNTs in the sensor, the response (displayed in Figure S3) is rather poor, in contrast to the best performing C60Br24/SWCNT composites with a 5 wt % SWCNT loading, which has been selected for further analysis in this work.

Figure 2.

Real-time response–recovery curves of sensors based on C60Br24/SWCNT composites having different SWCNT loadings: (a) 2, (b) 5, (c) 8, and (d) 10 wt %.

First, to evaluate the selectivity of the sensor, the response in six different gases including H2, CO, CH4, NO, NH3, and H2S was measured. As shown in Figure 3a, H2S induces the highest increase of resistance among all gases even though its concentration was the lowest, which indicates very good selectivity to this analyte. Due to the insignificant response of sensors to H2 and CH4 (even at high gas concentrations), we selected CO, NO, and NH3 as the main interference gas to further explore the cross-selectivity of the sensor in gas mixtures (Figure S4). The results show that the presence of CO or NO does not influence the sensor response to H2S. Contrarily, when a pulse of 10 ppm NH3 is introduced to the measurement chamber, the response of the sensor to it is superposed on the original response to H2S, which indicates that the composite cannot distinguish these two gases from each other. Gas concentration-dependent real-time resistance curves from 50 ppb to 1 ppm are plotted in Figure 3b, from which we calculate the responses of the sensor with and without considering the baseline drift as shown in Figure S5. By plotting both sets of response data as a function of H2S concentrations, we obtain the sensor calibration curves, which follow power functions with fractional exponents similar to those typical for heterogeneous adsorption according to the Freundlich model (Figure 3c). The sensor exhibited a good response of 1.75% at as low as 50 ppb H2S. It is important to note that the true response of the sensors is actually higher than the values we calculated because the gas pulse durations (10 min) we applied are not long enough to reach sensor saturation. Experiments with extended pulses of 1 h and an even longer duration as shown in Figures S6 and S4, respectively, indicate that the saturation requires ∼1 h and the response ∼2–3 times higher than that measured after 10 min. On the other hand, the extended gas pulse measurements result in a limited recovery (and maybe partial poisoning) of the sensors because the measured response for subsequent gas pulses with gradually increased H2S concentrations is decreased (Figure S6).

Figure 3.

(a) Gas response of the C60Br24/SWCNT composite (5 wt % SWCNTs) to various analytes in air buffer. (b) Transient response curves measured for H2S at concentrations from 50 ppb to 1 ppm. (c) Gas response vs H2S concentration (black) and calibration curves (red) of the C60Br24/SWCNT composite (5 wt % SWCNTs). (d) Real-time device resistance for repeated pulses of 25 ppb H2S.

Repeatability of sensor data is a critical key performance indicator for applications. As shown in Figures 3d and S7, repeated gas pulses produce nearly identical responses. It is also worth mentioning that based on the noise and the eventual response of the devices, the estimated detection limit of H2S with the C60Br24/SWCNT composite (5 wt %) is 1 ppb (Figure S8).

To study the effect of operating temperature on the sensing performance, we analyze the response for 100 ppb H2S at 50, 70, and 100 °C (Figure 4a). The response of the sensor is lower at higher working temperatures, which can be attributed to the reduced adsorption and enhanced desorption of the analyte at the active sites.40,41 On the other hand, humidity significantly increases the response of the sensor (measured in 100 ppb H2S) from 2.9% at 23 RH % (relative humidity) to 10.9% at 55 RH % (Figure 4b). Interestingly, the increase stops at RH 68% and is reduced at 80% RH, which may be attributed to the buildup of a physisorbed water film on the sensing composite hindering the adsorption of H2S molecules.42,43 In addition, an excess amount of surface-adsorbed water can lead to the deprotonation of H2S resulting in ionic moieties on the surface (H3O+, HS–, and S2–), which reduce the increase of sensor resistance.44

Figure 4.

Effects of temperature (a) and humidity (b) on the sensing performance for 100 ppb H2S. (c) Repeated real-time sensor resistance curve for H2S detection after 1 month.

Furthermore, we assessed the stability of sensors by performing new measurements after storing the devices in a laboratory atmosphere for up to a month (Figure 4c). Upon one month of storage, the base line resistance of the device increased to about twice of its original value (Figures 4c, see S9 for the results after 1, 7, and 10 days) and it also showed a slightly higher drift during the real-time measurement. However, the magnitude of response to H2S pulses remains quite similar, although with the signal less dependent on the gas concentration than earlier. It is also worth noting that the color of the C60Br24/SWCNT composite transformed from yellow into brown. The change of the color and base line resistance might be caused by the presence of moisture in the air, which may promote partial decomposition of the C–Br bonds in C60Br24.45−47 These aging effects will be analyzed in further studies.

2.3. Mechanism of Sensing

To understand the advantage of halogen bonds in the sensing process, we performed the same experiments with the C60/SWCNT composite (Figure 5) as with its C60Br24/SWCNT counterparts (displayed in Figure 2). While the C60/SWCNT composites show a clear response for H2S gas pulses, with the highest response of 0.90% at 0.1 ppm observed from the C60@10 wt % SWCNT composite, the corresponding response of the C60Br24/SWCNT composite is approximately two times higher even at a lower concentration (1.75% at 0.05 ppm). The transient response curve of the sensor based on C60@10 wt % SWCNTs for H2S sensing in the concentration range from 50 ppb to 1 ppm is shown in Figure S10. The results indicate that the presence of the C–Br and consequently the formation of a halogen bond with the analyte improve the sensing performance.

Figure 5.

Sensing performance of composites based on pristine C60 with (a) 2, (b) 5, (c) 8, and (d) 10 wt % SWCNTs.

To elaborate on the sensing mechanism, we have performed DFT calculations. In order to model the C60Br24/SWCNT interface, we placed a single C60Br24 molecule on the surface of a (10,10) SWCNT (which is metallic and has a diameter corresponding to the experimental values). The atomic structure and the resulting charge transfer upon joining the two constituents are illustrated in Figure 6a. The charge transfers and binding energies are also listed in Table 1. A remarkable transfer of 0.62 electrons from SWCNT to C60Br24 is found, owing to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital of C60Br24 falling close to the Fermi level of the metallic SWCNTs (cf. the energy level diagram in Figure S11). Thus, SWCNTs interfaced with C60Br24 become hole-doped. Next, we considered H2S adsorption on SWCNTs, C60Br24, and in the vicinity of the C60Br24/SWCNT interface. The binding energy is moderately large at the SWCNTs and near the C60Br24/SWCNT interface, suggesting that those are the dominant adsorption sites (cf. adsorption geometries in Figure S12). When H2S adsorbs on the nanotubes, it acts as an electron donor leading to local electron doping (Figure 6b). Such a spatial modulation of the hole concentration along the SWCNTs results in potential barriers (and scattering centers) in the longitudinal direction, which inherently causes a reduced conductivity of the SWCNTs and also their percolated network.

Figure 6.

Atomic structure of the interface between C60Br24 and SWCNTs (a) without analytes, and with several adsorbed (b) H2S and (c) NO molecules. The charge transfer upon joining is indicated by red and blue isosurfaces, with an isovalue of 0.0002 e/bohr3 used in all panels.

Table 1. Charge Transfer and Binding Energy Upon Joining CNTs and C60Br24 or Upon Adsorption of Gas Moleculesa.

| structure (A@B) | charge transfer (e) | binding energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| C60Br24@SWCNT | 0.616 | –1.126 |

| SWCNT@H2S | 0.011 | –0.274 |

| C60Br24@H2S | 0.037 | –0.014 |

| SWCNT/C60Br24@H2S | 0.004 (0.642) | –0.352 |

| C60@H2S | 0.004 | –0.001 |

| SWCNT@NO | 0.014 | –0.061 |

| C60Br24@NO | 0.137 | –0.113 |

| SWCNT/C60Br24@NO | 0.066 (0.831) | –0.524 |

| C60@NO | 0.068 | –0.030 |

For structure A@B, charge transfer is defined as electrons transferred from B to A. The value in parentheses refers to charge transfer in C60Br24@CNT in the presence of H2S or NO. Binding energy is defined as EB = ESens+Mol – (ESens + EMol), where ESens+Mol is the total energy of the sensor with the adsorbed molecule, ESens is the energy of the sensor, and EMol is the energy of molecules.

It is worth noting that in our experiments, exposure of the sensor to NO molecules (known to have a typically oxidizing character) has shown an increase of the resistance (Figure 3a), which is counterintuitive, as one may expect to see its opposite effect. Therefore, we performed calculations also for the interaction of NO with the sensing material to understand the underlying causes. Interestingly, the simulations indicate that also NO behaves as a weak electron donor (Figure 6c, Table 1 and Figure S13). The binding energy was the largest at the interface, highlighting the importance of the C60Br24/SWCNT interface for sensing. In the end, conductivity is expected to change in the same direction as for H2S, in agreement with our experimental observations.

While semiconducting tubes are also present in the sensor composites, only metallic nanotubes were considered in the calculations. Due to the very good percolation of nanotubes in the composite and very low resistance of the sensors (Figure 2b–d), most of the current in such sensors is expected to flow across the metallic nanotubes and little (if any) through the semiconducting ones. Moreover, the I–V curves in Figure S2 show Ohmic contacts, which also supports that the conduction occurs through metallic CNTs and junctions.

Furthermore, although we have not performed calculations for semiconducting CNTs (known to exhibit a p-type character), intuitively the mechanism of sensing shall be very similar to the one described above. Because the presence of a band gap is known to result in reduced conductivity, the overall transport is expected to be even more sensitive to inhomogeneous electron and hole doping by the analyte than that in the metallic nanotubes.

Furthermore, bromination of SWCNTs alone (i.e., without applying C60Br24) cannot effectively improve the sensing performance of SWCNTs (Figure S14) for H2S detection because the structure lacks spatial modulation of electron-rich and depleted regions along the nanotubes necessary for sensing as described by our model.

3. Conclusions

In our study, we reported a new type of sensing medium to detect gaseous analytes at room temperature. C60Br24 synthesized by the bromination of C60 in the presence of a FeBr3 catalyst was mixed with (SWCNTs) to achieve conductive composites. Because of Br in C60Br24, the material might be capable of forming halogen bonds of medium strength with H atoms of various gas molecules thereby yielding sensors with good gas adsorption, a high response, and reasonable recovery properties at room temperature. As we found, non-halogenated fullerenes mixed with SWCNTs were poor sensing materials, whereas devices based on the composites of C60Br24 and SWCNTs exhibited excellent sensing properties. In particular, high selectivity with excellent response (1.75% at 50 ppb) and a low experimental detection limit (25 ppb) for H2S was measured in contrast to other analytes (H2, CO, CH4, NO, and NH3). According to DFT simulations, the carrier transport in the CNTs is influenced by the modulation of carrier density along the nanotubes. Namely, the CNTs at the C60Br24 contact are p-doped, whereas locations at which H2S adsorbs directly on the CNTs are less positive due to the electron doping from H2S. Therefore, the spatial fluctuation of the hole concentration along the CNTs is amplified upon gas adsorption, which results in the formation of potential barriers (and scattering centers) in the longitudinal direction leading to reduced conductivity of the CNTs together with their percolated network.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials and Characterization

SWCNTs (diameter: 1.2–1.5 nm, length: 2–5 μm, and ID/IG = 0.02), fullerene, Br2 liquid, FeBr3, and ethanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. XRD measurements were carried out using a Multiple Crystals X-ray Diffractometer (XRD, Siemens D5000, Cu Kα radiation) with a step of 0.02°. XPS measurements were performed with a Kratos Axis Supra equipped with an Al Kα source. The microstructure of the synthesized material was studied using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Zeiss ULTRA plus). The TGA (Setaram Labsys) was conducted with air as the carrier gas at a heating rate of 10 °C/min from room temperature to 800 °C. The Raman spectra were recorded using a confocal microscope (Bruker Sentera II, λ = 532 nm excitation). The infrared spectra were collected using a Bruker Vertex 70 FT-IR unit in transmission mode with pure KBr as the background.

4.2. Synthesis of C60Br24 and Br-SWCNT

The procedure similar to that described by Djordjević and co-workers was adopted.32 In short, 300 mg (0.42 mmol) fullerene and 2 mL bromine liquid were stirred in the presence of 10 mg FeBr3 for 2 h at room temperature. After completing the reaction, the mixture was poured into a mixture of ethanol and H2O (1:2), vacuum filtered, and washed with the same mixture of ethanol and H2O. The obtained C60Br24 was dried in an oven at 80 °C for 24 h. Br-SWCNT was synthesized with the same method as that used for C60Br24. To prove that Br-SWCNT was synthesized successfully, FTIR and Raman spectra were collected (Figure S15).

4.3. Preparation of C60Br24/SWCNT Composites

SWCNTs and C60Br24 with different mass ratios of 2, 5, 8 and 10 wt % were dispersed in 5 mL chloroform separately using ultrasonication for 30 min, and the composite was collected by vacuum filtration.

4.4. Sensor Preparation

The process for fabricating sensors is as follows: 20 mg of composite was mixed with 0.5 mL of chloroform to form a paste, which was then brush-coated onto an Al2O3 substrate printed with five pairs of Ag–Pd interdigitated electrodes (IDES, electrode distance and width were both 200 μm) (14 mm × 7 mm) to form a sensitive film and dried at 70 °C for 20 min.

4.5. Sensing Measurements

The performance of the sensor based on C60Br24/SWCNT was characterized by measuring the resistance of the sensor exposed to different concentrations of the gas. The changes in the resistance were monitored through a Linkam THMS600 heating and freezing stage connected to an Agilent 3458A multimeter at a constant bias of 5 V, and different concentrations of H2S, NH3, NO, CH4, CO, and H2 were prepared using a dilution system controlled by a computer. Commercial dry synthetic air was used as the carrier to dilute these gases to the desired concentrations, and room temperature (∼25 °C) was maintained to be the operating temperature in this work. Specifically, the sensor was placed on the heating and freezing stage in a sealed chamber with an electric feed-through between a gas inlet and a gas outlet. To carry out measurements and compare the response in a convenient way, the exposure time was chosen as 10 min and the purging time was fixed at 30 min per pulse. To exclude the interference on the resistance from the different gas flow rates, in this work, the total flow of gas into the chamber was controlled at a rate of 500 mL/min. To add water vapor to the test gas, an additional air flow was bubbled through a water-containing flask and mixed to the analyte stream before inserting to the test chamber. The relative humidity was controlled by adjusting the carrier gas flow rates. The final humidity of the test gas was calibrated using a commercial humidity sensor.

4.6. DFT Calculations

All the calculations are carried out using DFT as implemented in the CP2K software.48−51 The PBE functional52 is used with Goedecker–Teter–Hutter (GTH) pseudopotentials53,54 and Gaussian-type MOLOPT basis sets (DZVP-MOLOPT-GTH).55 The D3 correction is used to describe vdW interactions56 and a cutoff energy of 800 Ry is set for the plane-wave expansion of the electron density. Comparison of the calculated bond lengths in C60 and C60Br24 to those reported in the literature is listed in Tables S1 and S2. The threshold for energy convergence is set to 10–12 Ha and the one related to SCF cycles is set to 10–6 Ha. A Fermi–Dirac smearing with an electronic temperature of 2000 K of the occupation number at the Fermi level is used except for NO that was 0 K. For SWCNTs, we use (10,10) chirality and a 12× supercell in the longitudinal direction. The Brillouin zone is sampled using the sole Γ-point. Charge transfer is determined using Mulliken population analysis.57 For finding the structure of both H2S and NO on both SWCNTs and C60Br24, we selected nine initial configurations with different positions and molecule orientations. In the case of the SWCNT/C60Br24 model, we considered the same nine configurations and two additional (11 total). The atom positions were then optimized, but not lattice constants. The bond lengths for the lowest energy structures were then compared to previous computational and experimental results, where available, and were found to agree with them. Binding energy and charge transfer for three other configurations of H2S and NO adsorbed on SWCNT/C60Br24 are listed in Table S3 and the atomic structures are shown in Figures S12 and S13.

Acknowledgments

We thank the personnel of the Centre for Material Analysis at the University of Oulu for providing us with technical assistance. We also would like to thank Prof. Csaba Visy for the valuable discussion on the effect of surface-adsorbed water on the sensing model. The authors thank CSC Finland for the generous grants of computer time. J.Z. is thankful for the grant received from the China Scholarship Council.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.1c16807.

XRD, TGA, repeatability, and sensing performance of pure SWCNTs and C60/SWCNTs; two definitions of response applied in the article; the measurements of noise and the calculation method of LOD; simulation information including the energy level diagram of each material; and adsorption model of H2S and NO and bond length in C60Br24 (PDF)

Author Contributions

J.Z. conducted the XRD, TGA, SEM, and electrical and sensor measurements and analyzed/plotted the data. C.P.B. measured the IR and Raman spectra. M.B. performed the DFT calculations. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J.Z. and H.-P.K. The manuscript was discussed and revised by J.Z., H.-P.K., T.J., K.K., and A.K. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kaur M.; Jain N.; Sharma K.; Bhattacharya S.; Roy M.; Tyagi A. K.; Gupta S. K.; Yakhmi J. V. Room-Temperature H2S Gas Sensing at Ppb Level by Single Crystal In2O3 Whiskers. Sens. Actuators, B 2008, 133, 456–461. 10.1016/j.snb.2008.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Na H.-B.; Zhang X.-F.; Deng Z.-P.; Xu Y.-M.; Huo L.-H.; Gao S. Large-Scale Synthesis of Hierarchically Porous ZnO Hollow Tubule for Fast Response to Ppb-Level H2S Gas. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 11627–11635. 10.1021/acsami.9b00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y.; Saito J.; Munakata M.; Shibata Y. Hydrogen Sulfide as a Novel Biomarker of Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Allergol. Int. 2021, 70, 181–189. 10.1016/j.alit.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramgir N.; Pathak A.; Sinju K. R.; Bhangare B.; Debnath A. K.; Muthe K. P.; Chemiresistive Sensors for H2S Gas: State of the Art In Recent Adv. Thin Film. Kumar S.; Aswal D. Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020, pp 625−663 10.1007/978-981-15-6116-0_19. [DOI]

- Jha R. K.; D’Costa J. V.; Sakhuja N.; Bhat N. MoSe2 Nanoflakes Based Chemiresistive Sensors for ppb-Level Hydrogen Sulfide Gas Detection. Sens. Actuators, B 2019, 297, 126687. 10.1016/j.snb.2019.126687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Yang Y.; Cui L.; Zheng F.; Song Q. Electroactive Au@Ag Nanoparticles Driven Electrochemical Sensor for Endogenous H2S Detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 117, 53–59. 10.1016/j.bios.2018.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.; Rao M.; Li Q. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Sensors for Detecting Toxic Gases: NO2, SO2 and H2S. Sensors 2019, 19, 905. 10.3390/s19040905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.; Wu W.; Wang B.; Dai X.; Xie W.; Yang Y.; Zhang R.; Shi X.; Zhu H.; Luo J.; Guo Y.; Xiang X.; Zu X.; Fu Y. H2S Gas Sensing Performance and Mechanisms Using CuO-Al2O3 Composite Films Based on Both Surface Acoustic Wave and Chemiresistor Techniques. Sens. Actuators, B 2020, 325, 128742. 10.1016/j.snb.2020.128742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali F. I. M.; Awwad F.; Greish Y. E.; Mahmoud S. T. Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) Gas Sensor: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 2394–2407. 10.1109/JSEN.2018.2886131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.; Xu X.; Han S.; Cai C.; Du H.; Zhu H.; Zu X.; Fu Y. ZnO-Al2O3 Nanocomposite as a Sensitive Layer for High Performance Surface Acoustic Wave H2S Gas Sensor with Enhanced Elastic Loading Effect. Sens. Actuators, B 2020, 304, 127395. 10.1016/j.snb.2019.127395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. G.; Shim Y. S.; Suh J. M.; Noh M. S.; Kim G. S.; Choi K. S.; Jeong B.; Kim S.; Jang H. W.; Ju B. K.; Kang C. Y. Ionic-Activated Chemiresistive Gas Sensors for Room-Temperature Operation. Small 2019, 15, 1902065. 10.1002/smll.201902065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.-J.; Choi Y.-K. Chemical Sensors Based on Nanostructured Materials. Sens. Actuators, B 2007, 122, 659–671. 10.1016/j.snb.2006.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schierbaum K.-D. Engineering of Oxide Surfaces and Metal/Oxide Interfaces for Chemical Sensors: Recent Trends. Sens. Actuators, B 1995, 24, 239–247. 10.1016/0925-4005(95)85051-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Zhang G.; Luo H.; Yao J.; Liu Z.; Zhang D. Highly Sensitive Thin-Film Field-Effect Transistor Sensor for Ammonia with the DPP-Bithiophene Conjugated Polymer Entailing Thermally Cleavable Tert-Butoxy Groups in the Side Chains. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 3635–3643. 10.1021/acsami.5b08078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panes-Ruiz L. A.; Shaygan M.; Fu Y.; Liu Y.; Khavrus V.; Oswald S.; Gemming T.; Baraban L.; Bezugly V.; Cuniberti G. Toward Highly Sensitive and Energy Efficient Ammonia Gas Detection with Modified Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes at Room Temperature. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 79–86. 10.1021/acssensors.7b00358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrin R.; Shah N. A. Room Temperature Gas Sensors Based on Carboxyl and Thiol Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes Buckypapers. Diamond Relat. Mater. 2015, 60, 42–49. 10.1016/j.diamond.2015.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di C.-a.; Zhang F.; Zhu D. Multi-Functional Integration of Organic Field-Effect Transistors (OFETs): Advances and Perspectives. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 313–330. 10.1002/adma.201201502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Someya T.; Dodabalapur A.; Huang J.; See K. C.; Katz H. E. Chemical and Physical Sensing by Organic Field-Effect Transistors and Related Devices. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 3799–3811. 10.1002/adma.200902760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis J. G.; Ravnsbæk J. B.; Mirica K. A.; Swager T. M. Employing Halogen Bonding Interactions in Chemiresistive Gas Sensors. ACS Sens. 2016, 1, 115–119. 10.1021/acssensors.5b00184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hines D.; Rümmeli M. H.; Adebimpe D.; Akins D. L. High-Yield Photolytic Generation of Brominated Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and Their Application for Gas Sensing. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11568–11571. 10.1039/c4cc03702b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhail M. H.; Abdullah O. G.; Kadhim G. A. Hydrogen Sulfide Sensors Based on PANI/f-SWCNT Polymer Nanocomposite Thin Films Prepared by Electrochemical Polymerization. J. Sci.: Adv. Mater. Devices 2019, 4, 143–149. 10.1016/j.jsamd.2018.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shirsat M. D.; Bangar M. A.; Deshusses M. A.; Myung N. V.; Mulchandani A. Polyaniline Nanowires-Gold Nanoparticles Hybrid Network Based Chemiresistive Hydrogen Sulfide Sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 083502. 10.1063/1.3070237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Järvinen T.; Lorite G. S.; Peräntie J.; Toth G.; Saarakkala S.; Virtanen V. K.; Kordas K. WS2 and MoS2 Thin Film Gas Sensors with High Response to NH3 in Air at Low Temperature. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 405501. 10.1088/1361-6528/ab2d48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asres G. A.; Baldoví J. J.; Dombovari A.; Järvinen T.; Lorite G. S.; Mohl M.; Shchukarev A.; Pérez Paz A.; Xian L.; Mikkola J.-P.; Spetz A. L.; Jantunen H.; Rubio Á.; Kordás K. Ultrasensitive H2S Gas Sensors Based on P-Type WS2 Hybrid Materials. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 4215–4224. 10.1007/s12274-018-2009-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.; Järvinen T.; Pitkänen O.; Kónya Z.; Kukovecz A.; Kordas K. Composites of Ion-in-Conjugation Polysquaraine and SWCNTs for the Detection of H2S and NH3 at ppb Concentrations. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 185502. 10.1088/1361-6528/abdf06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Huang L.; Zhu X.; Zhou X.; Chi L. An Ultrasensitive Organic Semiconductor NO2 Sensor Based on Crystalline TIPS-Pentacene Films. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1703192. 10.1002/adma.201703192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir M. A.; Bhat M. A.; Naikoo R. A.; Bhat R. A.; khan M.; Shaik M.; Kumar P.; Sharma P. K.; Tomar R. Utilization of Zeolite/Polymer Composites for Gas Sensing: A Review. Sens. Actuators, B 2017, 242, 1007–1020. 10.1016/j.snb.2016.09.152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L.; Wang W.; Guo Y.; Liu G.; Wan P. Flexible Polyaniline/Carbon Nanotube Nanocomposite Film-Based Electronic Gas Sensors. Sens. Actuators, B 2017, 244, 47–53. 10.1016/j.snb.2016.12.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon B.; Choi S.-J.; Swager T. M.; Walsh G. F. Switchable Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube–Polymer Composites for CO2 Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 33373–33379. 10.1021/acsami.8b11689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eising M.; Cava C. E.; Salvatierra R. V.; Zarbin A. J. G.; Roman L. S. Doping Effect on Self-Assembled Films of Polyaniline and Carbon Nanotube Applied as Ammonia Gas Sensor. Sens. Actuators, B 2017, 245, 25–33. 10.1016/j.snb.2017.01.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang R.; Shi Y.; Hou Z.; Wei L. Carbon Nanotube-Based Chemiresistive Sensors. Sensors 2017, 17, 882. 10.3390/s17040882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djordjević A.; Vojinović-Miloradov M.; Petranović N.; Devečerski A.; Lazar D.; Ribar B. Catalytic Preparation and Characterization of C60Br24. Fullerene Sci. Technol. 1998, 6, 689–694. 10.1080/10641229809350229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett P. R.; Hitchcock P. B.; Kroto H. W.; Taylor R.; Walton D. R. M. Preparation and Characterization of C60Br6 and C60Br8. Nature 1992, 357, 479–481. 10.1038/357479a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saeedfar K.; Heng L.; Ling T.; Rezayi M. Potentiometric Urea Biosensor Based on an Immobilised Fullerene-Urease Bio-Conjugate. Sensors 2013, 13, 16851–16866. 10.3390/s131216851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troyanov S. I.; Troshin P. A.; Boltalina O. V.; Kemnitz E. Bromination of [60] Fullerene. II. Crystal and Molecular Structure of [60] Fullerene Bromides, C60Br6, C60Br8, and C60Br24. Fullerenes, Nanotubes, Carbon Nanostruct. 2003, 11, 61–77. 10.1081/fst-120018665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Popov A. A.; Senyavin V. M.; Granovsky A. A. Vibrational Spectra of Chloro-and Bromofullerenes. Fullerenes, Nanotubes, Carbon Nanostruct. 2005, 12, 305–310. 10.1081/fst-120027184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazov I.; Krasnikov D.; Stadnichenko A.; Kuznetsov V.; Romanenko A.; Anikeeva O.; Tkachev E. Direct Vapor-Phase Bromination of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes. J. Nanotechnol. 2012, 2012, 954084. 10.1155/2012/954084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zygouri P.; Spyrou K.; Mitsari E.; Barrio M.; Macovez R.; Patila M.; Stamatis H.; Verginadis I. I.; Velalopoulou A. P.; Evangelou A. M.; Sideratou Z.; Gournis D.; Rudolf P. A Facile Approach to Hydrophilic Oxidized Fullerenes and Their Derivatives as Cytotoxic Agents and Supports for Nanobiocatalytic Systems. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8244. 10.1038/s41598-020-65117-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maity D.; Kumar R. T. R. Polyaniline Anchored MWCNTs on Fabric for High Performance Wearable Ammonia Sensor. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 1822–1830. 10.1021/acssensors.8b00589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assen A. H.; Yassine O.; Shekhah O.; Eddaoudi M.; Salama K. N. MOFs for the Sensitive Detection of Ammonia: Deployment of Fcu-MOF Thin Films as Effective Chemical Capacitive Sensors. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 1294–1301. 10.1021/acssensors.7b00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho B.; Hahm M. G.; Choi M.; Yoon J.; Kim A. R.; Lee Y.-J.; Park S.-G.; Kwon J.-D.; Kim C. S.; Song M. Charge-Transfer-Based Gas Sensing Using Atomic-Layer MoS2. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8052. 10.1038/srep08052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S.; Adak D.; Bhattacharyya R.; Mukherjee N. ZnO/γ-Fe2O3 Charge Transfer Interface toward Highly Selective H2S Sensing at a Low Operating Temperature of 30° C. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 1831–1838. 10.1021/acssensors.7b00636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.; Cheng X. F.; Gao B. J.; Yu C.; He J. H.; Xu Q. F.; Li H.; Li N. J.; Chen D. Y.; Lu J. M. Detection of NO2 Down to One ppb Using Ion-in-Conjugation-Inspired Polymer. Small 2019, 15, 1803896. 10.1002/smll.201803896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriver D. F.; Atkins P. W.; Overton T. L.; Rourke J. P.; Weller M. T.; Armstrong F. A.. Shriver & Atkins Inorganic Chemistry, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2006; p 384. [Google Scholar]

- Khakina E. A.; Troshin P. A. Halogenated Fullerenes as Precursors for the Synthesis of Functional Derivatives of C60 and C70. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2017, 86, 805. 10.1070/rcr4693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Troshin P. A.; Astakhova A. S.; Lyubovskaya R. N. Synthesis of Fullerenols from Halofullerenes. Fullerenes, Nanotubes, Carbon Nanostruct. 2005, 13, 331–343. 10.1080/15363830500237192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Troyanov S. I.; Kemnitz E. Synthesis and Structure of Halogenated Fullerenes. Curr. Org. Chem. 2012, 16, 1060–1078. 10.2174/138527212800564367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kühne T. D.; Iannuzzi M.; Del Ben M.; Rybkin V. V.; Seewald P.; Stein F.; Laino T.; Khaliullin R. Z.; Schütt O.; Schiffmann F.; Golze D.; Wilhelm J.; Chulkov S.; Bani-Hashemian M. H.; Weber V.; Borštnik U.; Taillefumier M.; Jakobovits A. S.; Lazzaro A.; Pabst H.; Müller T.; Schade R.; Guidon M.; Andermatt S.; Holmberg N.; Schenter G. K.; Hehn A.; Bussy A.; Belleflamme F.; Tabacchi G.; Glöß A.; Lass M.; Bethune I.; Mundy C. J.; Plessl C.; Watkins M.; VandeVondele J.; Krack M.; Hutter J. CP2K: An Electronic Structure and Molecular Dynamics Software Package-Quickstep: Efficient and Accurate Electronic Structure Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 194103. 10.1063/5.0007045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter J.; Iannuzzi M.; Schiffmann F.; VandeVondele J. Cp2k: Atomistic Simulations of Condensed Matter Systems. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2014, 4, 15–25. 10.1002/wcms.1159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- VandeVondele J.; Krack M.; Mohamed F.; Parrinello M.; Chassaing T.; Hutter J. Quickstep: Fast and Accurate Density Functional Calculations Using a Mixed Gaussian and Plane Waves Approach. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2005, 167, 103–128. 10.1016/j.cpc.2004.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- VandeVondele J.; Hutter J. An Efficient Orbital Transformation Method for Electronic Structure Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 4365–4369. 10.1063/1.1543154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Burke K.; Ernzerhof M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. 10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedecker S.; Teter M.; Hutter J. Separable Dual-Space Gaussian Pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1996, 54, 1703. 10.1103/physrevb.54.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwigsen C.; Goedecker S.; Hutter J. Relativistic Separable Dual-Space Gaussian Pseudopotentials from H to Rn. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1998, 58, 3641. 10.1103/physrevb.58.3641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VandeVondele J.; Hutter J. Gaussian Basis Sets for Accurate Calculations on Molecular Systems in Gas and Condensed Phases. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 127, 114105. 10.1063/1.2770708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. G. A.; Burns L. A.; Patkowski K.; Sherrill C. D. Revised Damping Parameters for the D3 Dispersion Correction to Density Functional Theory. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 2197–2203. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulliken R. S. Electronic Population Analysis on LCAO–MO Molecular Wave Functions. I. J. Chem. Phys. 1955, 23, 1833–1840. 10.1063/1.1740588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.