Abstract

Background:

The world is currently unprepared to deal with the drastic increase in global migration. There is an urgent need to develop programs to protect the well-being and health of migrant peoples. Increased population movement is already evident throughout the Americas as exemplified by the rising number of migrant peoples who pass through the Darien neotropical moist broadleaf forest along the border region between Panama and Colombia. The transit of migrant peoples through this area has an increase in the last years. In 2021, an average of 9400 people entered the region per month compared with 2000–3500 people monthly in 2019. Along this trail, there is no access to health care, food provision, potable water, or housing. To date, much of what is known about health needs and barriers to health care within this population is based on journalistic reports and anecdotes. There is a need for a comprehensive approach to assess the health care needs of migrant peoples in transit. This study aims to describe demographic characteristics, mental and physical health status and needs, and experiences of host communities, and to identify opportunities to improve health care provision to migrant peoples in transit in Panama.

Study design and methods:

This multimethod study will include qualitative (n = 70) and quantitative (n = 520) components. The qualitative component includes interviews with migrant peoples in transit, national and international nongovernmental organizations and agencies based in Panama. The quantitative component is a rapid epidemiological study which includes a questionnaire and four clinical screenings: mental health, sexual and reproductive health, general and tropical medicine, and nutrition.

Conclusion:

This study will contribute to a better understanding of the health status and needs of migrant peoples in transit through the region. Findings will be used to allocate resources and provide targeted health care interventions for migrant peoples in transit through Darien, Panama.

Keywords: Darien, health equity, Latin America, migrant peoples, tropical medicine

Introduction

Currently, there are 281 million international migrant peoples worldwide, which is three times greater than the number of migrant peoples estimated in 1970. 1 In addition, the number of forcibly displaced people worldwide has risen dramatically in the past decade. 2 The world is currently unprepared to deal with population movement of this scale, and there is an urgent need to develop programs to protect the well-being and health of migrant peoples. A dramatic increase in population movement is evident through the Americas, where migrant peoples from Africa, Asia, South America, and the Caribbean travel through South and Central America en route to North America. Although other portions of the route may involve travel by air, train, or bus, migrants who arrive in South America headed north must travel on foot through the Darien National Forest along the border region between Panama and Colombia.

The Darien Forest (DF), commonly called the ‘Darien Gap’, is a roadless, dense, 106-km long neotropical moist broadleaf forest that interrupts the Pan-American Highway and serves as a natural barrier between Colombia and Panama. The crossing – through what is known to be ‘the most dangerous and inhospitable’ jungle in the world – is a treacherous journey, often taking between 7 and 14 days depending on the route taken, the amount of food carried, and travel group members’ abilities. 3

Migrant peoples who travel this route have no access to potable water or food and must face deadly river crossings, scorching high temperatures, and poisonous animals. Some indigenous communities situated along the dense forest’s outskirts provide a temporary resting place for migrant peoples in transit. Drug traffickers also share the trails, and people who have made the journey have commonly reported human trafficking, smuggling, and violence. Moreover, from May to September 2021, 180 cases of rape were reported to Doctors Without Borders. 4

The National Border Police (SENAFRONT) guides migrant peoples who emerge from the Gap to ‘Migrant Reception Stations’ (MRS), organized by the National Migrant Services. All individuals who enter by foot into Panama, with very few exceptions, pass through these MRS. These posts are part of the international ‘controlled flow’ of migrant peoples in a coordinated effort between the United States and Panama, where biometric measurements are taken of all individuals entering the country to screen for terrorism and keep a document trail of individuals.5,6 Time spent at the MRS depends on several factors including the individual’s nationality, health needs, and demographics. Citizens of some countries are allowed to pass quickly, while others may need to wait months for their migration process in Panama. Individuals from South America and the Caribbean (except Haiti and Cuba) are among those who have nonexpedited processes and these nationals who arrive in Darien must go through lengthy months-long visa processes before continuing. Citizens from other countries often stay in the Darien MRSs for approximately 3–14 days before being transported to another MRS near the Panama–Costa Rica border, where they will remain until initiating their travels north.

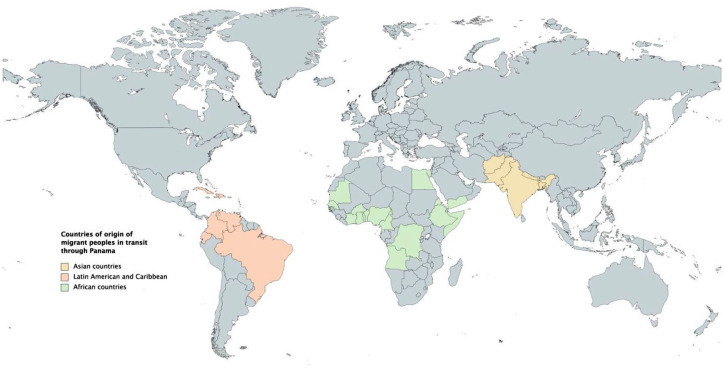

From 2015 to 2021, there has been a steady increase in the number of migrant peoples in transit that pass through the DF at the Colombia–Panama border en route to North America.7–9 Prior to 2020, there were between 2000 and 3000 individuals who crossed into Panama monthly through the DF. These trails have been used for centuries to cross between the two countries; however, from 2016 onward the number of people using this route has increased annually. From January to September 2021, more than 91,000 migrant peoples entered Panama through the DF. 10 This recent increase follows a period early in the COVID-19 pandemic where a large number of people were unable to cross international borders.8,11 In addition, perceptions of the United States’ changes in immigration policies with the Biden administration has been identified as impacting the number of migrant peoples through these routes. 12 Individuals who make this journey come from different countries (Map 1). According to official records from Panama’s National Migration Service, over 70% are Haitian citizens, 20% Cuban citizens, and the remaining 10% originate from sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and South America. 8 Furthermore, from 2018, there has been an increase in children, families, and pregnant women entering Panama on foot through the DF.8,13 Individuals from outside the continent arrive in South America by land or sea, often arriving in Ecuador or Brazil, beginning their journey by land up to the Panama–Colombia border.7–9

Map 1.

Countries of origin of migrant peoples in transit, after crossing the Darien Forest, Migrant Reception Stations in Darien, Panama (documented from data collected by Migration System, Panama, March 2021).

There is no access to health care along the route through the DF and very limited access to needed health services while in the MRSs. During the DF crossing, migrant peoples are exposed to dangerous elements from the days spent in the tropical forest and people encountered during their route. These elements are coupled with increased prevalence of diseases and health conditions common in their countries of origin prior to beginning their route through Darien. In recent years, Panama’s Ministry of Health (MINSA) and some international organizations have provided resources to begin to address the health needs and offer health care to migrant peoples in transit at the MRS. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has reoriented health care service provision, where health care is focused on SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and quarantine; however, other services such as general health, sexual health, mental health, reproductive medicine, and fever management have been left aside.14,15 Pan American Health Organization has recommended in their priority actions a need to strengthen surveillance and monitoring of the prevalence of health conditions through: (1) the development of comprehensive profiles of the health status of migrants, and (2) strengthening of national and decentralized health surveillance systems, especially in the border-transit areas that can capture the health status and needs of migrants. 16 In accordance with these recommendations, this study protocol is intended to be a rapid assessment of migrant peoples’ health status, needs, impact on surrounding communities, and opportunities for improved service provision to this population. Results from the study will inform future health care for migrants in transit in Darien and the region.

Methods

Study design and population

This study will use both qualitative and quantitative cross-sectional methods. We will use qualitative research methods to capture the perspectives and experiences of migrant peoples in transit and stakeholders (Table 1). In addition, we will use qualitative research to learn from the experiences of a variety of stakeholders, including those who provide services, design and allocate resources to programming, and individuals that live in the communities where migrants pass while crossing the DF. Participants within the study’s qualitative component include government health and migration personnel, representatives from international organizations working with migrant populations, community members from surrounding host communities, and migrant peoples.

Table 1.

Study components and activities to be undertaken.

| Qualitative (Component A) | Quantitative (Component B) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative data collection | Quantitative questionnaire | Mental health | Sexual and reproductive health | General and tropical medicine | Nutrition | |

| Target population | Community officials, governmental, and nongovernmental personnel who work with the target population, migrant peoples in transit, people who live in the communities where migrant peoples travel through or live | Migrant peoples in transit | Migrant peoples in transit | Migrant peoples in transit | Migrant peoples in transit | Migrant peoples in transit |

| Activities | Semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and participant observation | Self-administered quantitative questionnaire | Clinical evaluation and screening | Clinical evaluation and screening | Clinical evaluation and screening | Clinical evaluation and screening |

The qualitative component (Component A) will use purposive sampling and undertake semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and select participant observation to assess health needs and service provision to migrant peoples (Table 2). Qualitative data collection tools (i.e. semi-structured interview guides for each stakeholder group) will be designed to capture data to describe divergent health priorities and available health services, evaluate patient barriers for accessing health services, and document needed resources for improving health care provision according to stakeholder perspectives. Through coding and thematic analysis of interviews, results of the qualitative component will allow our research team to contextualize prevalence data from the quantitative study component. The qualitative component will provide insights from key stakeholder groups, in their own words. Interviews will provide rich descriptions of the migrant experience and health needs of migrants in transit through Darien, as well as challenges to health services provision. We will use this information to prioritize needs and identify targets and strategies for future intervention.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study in the rapid evaluation of health among migrant peoples in transit in Migrant Reception Stations (MRS), Darién, Panama.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criterion | |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative study | 1. Aged > 17 years 2. Speak and write at least basic level one of these languages: Spanish, English, Haitian Creole, French, or Portuguese |

Have a planned exit from an MRS the same day the study team has reached the person |

| Quantitative questionnaire | 1. Aged > 17 years 2. Speak and write at least basic level one of these languages: Spanish, English, Haitian Creole, French, or Portuguese |

|

| Mental health | 1. Aged > 12 years 2. Speak and write at least basic level one of these languages: Spanish, English, Haitian Creole, French, or Portuguese |

|

| Sexual and reproductive health | 1. Aged > 12 years 2. Speak and write at least basic level one of these languages: Spanish, English, Haitian Creole, French, or Portuguese |

|

| General and tropical medicine | 1. Speak and write at least basic level one of these languages: Spanish, English, Haitian Creole, French, or Portuguese | |

| Nutrition | 1. Speak and write, or have a guardian if under 12 who speaks and writes at least basic level one of these languages: Spanish, English, Haitian Creole, French, or Portuguese |

MRS, migrant reception stations.

The quantitative component (Component B, Table 1) includes a rapid epidemiological study among migrant peoples in transit. This component will include a self-administered questionnaire, and four clinical screenings: mental health, sexual and reproductive health, general and tropical medicine, and nutrition. Age of inclusion for each subcomponent can be found in Table 2. The self-administered questionnaire (Supplementary material A) includes demographics, migration routes, sexual and reproductive health and behaviors, and self-reported health. This questionnaire was developed from existing instruments (some modified for this population).17–26 For the clinical laboratory components, participants will be asked to provide a mid-stream urine sample and a peripheral blood sample for laboratory point-of-care screenings for the following infections/conditions: hepatitis A, B, C, and E; Chagas disease; malaria; dengue; chikungunya; HIV; syphilis; and pregnancy (Table 3). Further rapid testing will be applied, according to clinical presentations, as indicated in Table 4. Clinical screening will include a review of the present and past medical history, vital signs, body measurements, and a physical examination. On-site treatment (Table 5) and/or referral to primary, secondary, or tertiary centers will be organized (supplementary material B) according to clinical and laboratory findings.

Table 3.

Study activity, target population, and primary outcomes in the rapid evaluation of health among migrant peoples in transit in Migrant Reception Stations (MRS), Darién, Panamá.

| Activity | Target population | Site | Primary outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative component | Focus groups | Host communities | Host communities | Effects of migrant presence on communities, health priorities, and needs. |

| Semi-structured interviews and participant observation | Migrant peoples in transit | MRS | Migration experience, barriers to health access and existing programs, health needs | |

| Semi-structured interviews and participant observation | Public institution and nonprofit national/international organization leaders who work with migrant populations in transit | MRS, health centers, institutional and organization offices | Health services available, barriers to access, needs of institutions and organizations | |

| Quantitative component | Self-administered questionnaire | Migrant peoples in transit | MRS | • Sociodemographic and journey information • Human smuggling and trafficking • Education and employment • Self-rated health status • Sexual biography and sexual experience • Female genital cutting (for some countries) • Pregnancy and fertility • Self-reported Sexually transmitted infections/human immunodeficiency virus (STI/HIV) current and past • Nonconsensual sex • Whereabouts of family members and communication with family • Felt social support |

| Mental health | Migrant peoples in transit | MRS | • Use of Refugee Health Screener to do an initial screen of

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety,

and somatization. • Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Neuropsychiatric International Interview: Diagnosis by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) criteria • 8-item version of WHO Quality of Life Survey (EUROHIS): subjective quality of life |

|

| Sexual and reproductive health | Migrant peoples in transit | MRS | • Screening for vaginal and urethral discharge

disease • Screening for genital ulcer disease • Urine dipstick test (leukocyte esterase and nitrite) • HIV rapid test (4th generation) • Syphilis rapid test, rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titer confirmatory |

|

| General and tropical medicine | Migrant peoples in transit | MRS | • Rapid point-of-care tests for: ○ Hepatitis A virus (HAV) ○ Hepatitis B virus (HBV) ○ Hepatitis C virus (HCV) ○ Hepatitis E virus (HEV)○ Chagas ○ Malaria ○ Dengue ○ Chikungunya ○ Pregnancy ○ Further screening based on clinical presentation (Table 4) • Clinical screening: ○ Review of present and past medical history ○ Vital signs: Blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory frequency, temperature, blood oxygen saturation • Physical examination based on systems: neurological, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, hepato-splenic, skin, and genitourinary |

|

| Nutrition | MRS | • Screening for malnutrition and

undernourishment ○ Height-weight ○ Body mass index (BMI) ○ Mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) ○ Marasmus and Kwashiorkor screening ○ Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) ○ Skinfold test ○ WHO growth charts |

MRS, migrant reception stations.

Table 4.

Further test based on clinical criteria for inclusion.

| Test | Clinical criteria for inclusion |

|---|---|

| COVID-19 (antigen or polymerase chain reaction test (PCR)) | Fever or clinical suspicion |

| Crypto-Giardia-Entamoeba (antigen) | Diarrhea |

| Cytomegalovirus (antibody) | HIV positive, pregnant women with clinical suspicion |

| Yellow fever (PCR) | Fever or clinical suspicion |

| Amsel criteria | Vaginal secretion and suspicion of candidiasis |

| Trypanosoma cruzi detection (blood smear) | Chagas positive test result, presence of acute symptoms, and suspicion based on country of origin |

| Leishmaniasis (tissue Giemsa stain) | Suggestive ulcer and clinical suspicion |

| Mycobacterium leprae (Ziehl-Nielsen stain or Fite-Faraco stain) | Clinical suspicion of hypochromic anesthetic lesion or nodule |

| Leptospira (serum IgG/IgM antibody) | Fever or clinical suspicion |

| Malaria (thick blood smear) | Clinical suspicion and based on country of origin (if endemic) |

| Rota/adenovirus (Stool antigen) | Pediatric age with diarrhea or gastroenteritis, in adults: fever and symptomatic respiratory |

| Measles (antibody) | Fever, malaise rash, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, enanthem, and morbilliform exanthem |

| Toxoplasmosis, Rubeola, cytomegalavirus, Herpes Simplex Types 1 and 2 (TORCH [antibody]) | Pregnant and in 1-month-old babies |

| Toxoplasmosis (antibody IgG) | HIV positive, pregnancy, and clinical suspicion |

| Tuberculosis (sputum bacilloscopy) | Fever, cough, nocturnal sweat, HIV+ |

| Typhus/para-typhus (blood antigen) | Fever and clinical suspicion |

Table 5.

On-site treatment by study subcomponent.

| Study subcomponent | Treatment given on-site for diagnosed etiology or based on clinical and syndromic suspicions |

|---|---|

| Mental health | Distress, psychosis, and/or risk of self or heteroaggressive outburst: Management with verbal containment and, if needed, pharmacologic management with 5 mg of diazepam, repeated up to two times; if not, olanzapine 5 mg PO or haloperidol 5 mg IM. |

| Sexual and reproductive health | 1. Genital Herpes simplex: Acyclovir 400 mg per os (PO) ter

in die (TID) for 7 days. 2. Recurrent genital Herpes Simplex: Acyclovir 800 mg PO TID for 2 days or 400 mg PO TID for 5 days. 3. Syphilis: Benzathine Penicillin 2.4 million international units (IU) single-dose intramuscular injection (IM), once or each consecutive week for 3 weeks depending on patient history/ rapid plasma reagin (RPR) 4. Syphilis in pregnant women: 2.4 million IU IM each week for 3 weeks 5. Chancroid: Azithromycin 1 g PO single dose or Ceftriaxone 250 mg single dose IM or Ciprofloxacin 500 mg bid for 3 days 6. Chancroid in pregnant/lactating women: Erythromycin 500 mg PO QID for 15 days 7. Lymphogranuloma venerum: Doxycycline 100 mg PO daily for 21 days or Erythromycin 500 mg PO QID for 21 days OR Azithromycin 1 g PO each week for 3 weeks 8. Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Ceftriaxone 500 mg IM single dose 9. Chlamydia trachomatis: Azithromycin 1 g PO single dose or Doxycycline 100 mg PO bis in die (bid) for 7 days. 10. Trichomonas vaginalis: Metronidazole 2 g PO single dose 11. Candida albicans: Fluconazole 150 mg PO single dose or Clotrimazole ovules 100 mg intravaginal for 7 days 12. Bacterial vaginosis: Metronidazole 2 g PO single dose |

| General and tropical medicine | 1. Cardiovascular system: Symptoms associated with

myocarditis, endocarditis, pericarditis with clinical

suspicion of: 1.1 Mild leptospirosis: Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for 7 days or Azithromycin 500 mg PO each day for 3 days 1.2 Trypanosoma cruzi: Benznidazole 5–7 mg/kg/day PO divided in two doses: bid for 60 days 1.3 Taenia solium: Praziquantel 10 mg/kg PO single dose 1.4 Ascaris lumbricoides: 400 mg PO single dose 1.5 Strongyloides stercolaris: Ivermectin 200 µg/kg/day PO for 1–2 days 1.6 Paragonimus westermanii: Praziquantel 25 mg/kg PO tid for 2 days 1.7 Mansonella perstans: Doxycycline 200 mg PO each day or 100 mg PO bid for 6 weeks 2. Congestive Heart Failure symptoms that might be due to: 2.1 Schistosoma mansonii: Praziquantel 40 mg/kg PO single dose 3. Loeffler Syndrome that might be due to: 3.1 Ascaris lumbricoides: Albendazole 400 mg PO single Dose 3.2 Strongyloides stercolaris: Ivermectin 200 µg/kg/day PO for 1–2 days 3.3 Ancyslostoma duodenale: Albendazole 400 mg PO for 1–3 days 3.4 Necator americanus: Albendazole 400 mg PO for 1–3 days |

| 4. Dyspnea or Pneumonia suspicion due

to: 4.1 Streptococcus pneumoniae: With recent use of antibiotics and comorbidities: Amoxicillin-Clavulanate 875/125 mg 1 tablet PO bid + Clarithromycin 500 mg PO bid for 7 days OR Azithromycin 500 mg PO in the first dose and then 250 mg PO each day for 4 days With recent use of antibiotics and no comorbidities: Amoxicillin 1 g PO bid for 7 days No recent use of antibiotics: Clarithromycin 500 mg PO bid for 7 days or Azithromycin 500 mg PO in the first dose and then 250 mg PO each day for 4 days. 4.2 Mycoplasma pneumoniae / Chlamydia pneumoniae / Chlamydia psittaci: Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for 7 days 4.3 Haemophilus influenzae: Amoxicillin/Clavulanate 875/125 mg tab one tablet PO bid for 7 days. 4.4 Legionellosis: Levofloxacin 750 mg PO each day for 10 days 4.5 Coccidioidomycosis: Fluconazole 400 mg PO each day for 3–12 months 4.6 Blastomycosis: Itraconazole 200 mg PO tid for 3 days and then each day for 6–12 months 4.7 Schistosoma mansonii: Praziquantel 40 mg/kg PO single dose 4.8 Filariasis: Doxycycline 100 mg PO each day for 6–8 weeks |

|

| 5. Gastrointestinal symptoms – Hepato-splenomegaly by

clinical diagnosis or suspicion of the following

etiologies: 5.1 Schistosoma mansonii / japonicum: Praziquantel 40 mg/kg–60 mg/kg PO single dose (without previous treatment, dependent on country of origin) Suspiacian of acute toxemic shistosomiasis: short course high-dose prednisone + 40 mg/kg-60 mg/kg Praziquantel PO in single dose, repeat Praziquantel in 4–6 weeks. 5.2 Toxocariosis: Albendazole 400 mg PO bid for 5 days + Prednisone (optional) 60 mg each day for 5 days Jaundice (pre-hepatic-post) by clinical diagnosis or suspicion of the following etiologies: 5.3 Bartonella bacilliformis: Doxycycline 100 mg PO each day for 6–8 weeks 5.4 Coxiella burnetti: Doxycycline 100 mg PO each day for 2 weeks 5.5 Chlamydia psittaci: Doxycycline 100 mg PO each day for 7 days 5.6 Salmonella typhi: Levofloxacin 750 mg PO each day for 7 days 5.7 Ascaris lumbricoides: Albendazole 400 mg PO single dose (may also be related to malabsorption syndrome) 5.8 Cryptosporidium parvum/hominis: Nitazoxanide 500 mg PO bid for 3 days 5.9 Giardia lamblia: Tinidazole 2 g PO single dose (may also be related to malabsorption syndrome) 5.10 Strongyloides stercolaris: Ivermectin 200 µg/kg/day for 1–2 days 5.11 Trichinellosis: Albendazole 400 mg bid for 8–14 days + Prednisone 60 mg PO each day |

|

| 6. Cutaneous – by papule / macule (vascular or not

painful) 6.1 Bartonella henselae/bacilliformis: Doxycycline 100 mg PO each day for 7 days 6.2 Human Papillomavirus: Podofilox gel or solution at 0.5% – apply tid for 30 days 6.3 Molluscum contagiosum: Amphotericin B 0.6 mg/kg/day PO for 2 weeks OR Itraconazole 400 mg/day PO for 10 weeks and then 200 mg/day PO till the CD4 count in HIV patients is >100 cells /µL for > 6 months responding to RVT By papule/macule (painful) 6.4 Dermatobia hominis / Cordylobia anthropophaga / Tunga penetrans: Petroleum jelly or an occlusive agent so when the larva moves, a manual extraction is done. By papule/macule that causes itch 6.5 Schistosoma spp: Praziquantel 40 mg/kg single dose PO 6.6 Pediculus humanus corporis/capitis: Ivermectin 12 mg PO each day for 14 days 6.7 Sarcoptes scabiei: Permethrin cream 5% apply on skin for 8–14 h and repeat in 1–2 weeks Vesicles 6.8 Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2: Acyclovir 400 mg PO tid for 7–10 days 6.9 Sporotrichosis: Itraconazole 200 mg PO each day for 2–4 weeks 6.10 Rickettsia akari/prowazekii/typhi / Leptospirosis: Doxycycline100 mg PO bid for 7 days 6.11 Borrelia burgdorferi: Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for 2 weeks Morbilliform exanthem 6.12 Mycoplasma pneumoniae: Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for 7 days 6.13 Ehrlichia chafeensis / Anaplasma phagocytophilum 100 mg PO bid for 2 weeks 6.14 Histoplasma capsulatum: Itraconazole 200 mg TID for 3 days, then 200 mg bid for 12 months 6.15 Coccidioides posadasii: Fluconazole 400 mg PO each day for 3–12 months 6.16 Sporothrix spp.: Itraconazole 200 mg PO each day for 2–4 weeks 6.17 Actinomycetoma: Itraconazole 200 mg PO each day for 2–4 weeks 6.18 Chromoblastomycosis (Fonsacaea pedrosoi): Itraconazole 300 mg PO each day for 3–9 months |

|

| Nutrition | Mild-moderate acute malnutrition in: Children from 0 to 6 months Children from 6 months to 5 years Children 6–17 years old 18 years or above: Men and women Pregnant women |

Sample size calculations

To determine the required sample size for (1) participants aged ⩾18 years, and (2) participants aged <18 years in this cross-sectional, observational study, we used where n is the sample size, Z the confidence statistic, P is expected prevalence and d is the precision. 27 Based on a past survey by the International Migration Organization, we expect 16% of migrant peoples in transit in Panama with gastrointestinal diseases; this prevalence was used for sample size calculation. 28 The sampling frame composed of a total population expected to enter the MRS (2500; 20% of those are <18 years). In total, 120 participants <18 years and 160 participants ⩾18 years will be included. We have a larger planned sample for the questionnaire, as we expect over half of these individuals will consent to filling out the questionnaire but not be willing to participate in the more time-consuming clinical components.

Ethical considerations

This study has approval from the Comité de Bioética de la Investigación del Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud (260/CBI/ICGES/21). Participants 18 years and older will be asked to read a study information sheet and sign the informed consent form. Participants 12–17 years will have their guardian read and sign the guardian information sheet and informed consent form, and the participant will be required to read and sign the informed assent form. Participants <12 years will be required to have a guardian read and sign the informed guardian consent form. Participants will not be offered monetary compensation for their participation. However, a small snack (valued at less than $3.00) will be provided. All participants will be given educational sheets that cover the syndromes and infections tested for, and these sheets will be posted publicly at the MRSs. The consent forms, assent forms, questionnaire, and educational materials will be available in Spanish, English, French, Haitian Creole, and Portuguese languages.

Participant selection

In Component A, we will use purposive sampling. Community leaders will be asked to attend focus group interviews, and institutional, national, and organization leaders will share their perspectives through individual semi-structured interviews. A group of migrant peoples will also be selected to participate in individual semi-structured interviews. Select migrants accessing health services may be accompanied to observe their experiences within available health care providers. A total of 70 participant interviews and focus group discussions are anticipated within the qualitative study component, as this number is expected to allow us to reach saturation in capturing stakeholder perspectives and experiences.

In Component B, participants will be included systematically, where groups of 40–50 individuals arrive at the MRS where the sampling will be undertaken. When lined up to be registered with the Migration Service, small invitation cards will be given to every 1:n person from each stratum. The n will be calculated at the start of each day and depends on the number of expected strata to arrive each day, to include between 30 and 50 participants daily. After the person finalizes the migration registration process, they will be asked to join the study group at the respective study tents. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are dependent on the study component, as outlined in Table 2. As potential participants may be at the MRS for an undetermined amount of time, this study will only include participants who do not have a planned exit from the MRS within 8 h.

Data capture

Data capture will differ by study component and methods employed. Component A will include participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and focus groups captured via ethnographic fieldnotes and recorded on a digital recorder. Interviews and focus groups will be conducted in Spanish and, if needed, interviews with migrant persons will be undertaken in English and through real-time interpreters of French, Portuguese, or Haitian Creole. Component B will include a self-administered questionnaire on a tablet using Kobo Toolbox Software (Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, Cambridge, MA) and will be stored on the device under the participant’s code until Wi-Fi is available. Clinical and laboratory information will be inputted into Kobo Toolbox with a separate entry for each participant.

Pharmacological and psychological treatment and referral

On-site treatment by study subcomponent is found in Table 5. If the participant needs to be referred to primary, secondary, or tertiary facilities for further care (Supplementary Table B), this will be organized by the study team and the participant will be transported with no cost to them.

Pharmacological treatment

On-site pharmacological treatment will be given according to the severity of the affectation. A higher level of care will be arranged if needed to on-site or referral to the nearest health center in the town of Meteti or to the secondary and tertiary hospitals, in Chepo and Panama City, respectively. The field clinic where the study is undertaken is rudimentary and will not attend to all needs. Therefore, some cases will be referred to health centers and hospitals where (a) the condition requires further testing or specialized care, or (b) treatment is intravenous or daily injections, as described in Table 5.

Psychiatric care and treatment

Following the Refugee Health Screener-15 item survey (RHS-15) screening and meeting with the psychiatrist, individuals who would like to participate in group-oriented therapy are welcome to attend language-based sessions. In addition, at any time, if the participant seems in distress, presents with acute psychosis or self/heteroaggression, immediate consultation with an on-site psychiatrist will be done. Treatment protocol is summarized in Table 5 according to syndromic presentations.

On-site management of distress

At any time during the study, if a participant is anxious, depressed, or distressed, the ‘Distress Protocol’ will be activated (Supplementary material C). The ‘Violence Protocol’ will be implemented for individuals who report sexual violence during the qualitative component, questionnaire, or clinical exam (Supplementary material D). These are based on the Ministry of Health procedure for sexual violence, rape, incest, and a previously published protocol for children who report violence that has been used in previous studies in Panama and worldwide.23,29

Lab and clinical results

The laboratory point-of-care (POC) tests and clinical results will be given to every participant in paper format the day they are included in the studies. All results will be explained to the participants at the time results are offered. The results will also be found in a password-protected location on the Gorgas Memorial Institute for Health Studies’ webpage. Each participant will have access to a secure portal for 1 year, which will house their study results and educational sheets. The portal will be accessible from a phone or computer. The participants’ access information and password will be clipped into their passports.

Data analysis plan

Data analysis will depend on the study component.

For Component A, recordings and fieldnotes will be transcribed; all identifying information will be deleted. The recorded files will be destroyed after the transcription. Transcripts will be coded by MB and AG using NVivo software (QSR International Pty, Melbourne, Australia). Both coders will work independently and codes will be compared, discussed, and discrepancies will be resolved. Transcripts will be saved on an encrypted external hard drive. The data will be analyzed with a thematic analysis method and in an essentialist manner, meaning the participant experiences will be revealed. Transcripts will then be coded at a manifestation level to include the main themes. It is also possible that some codes emerge inductively from the data. This hybrid method of analysis from the data has been previously described and demonstrated to be rigorous. 30 A thematic map will be constructed, revised, and altered based on team discussions; contradictions and negative cases will be identified and presented.

For Component B, descriptive and analytical methods will be used to describe the findings of the quantitative questionnaire, including sociodemographic factors, sexual and reproductive biography, sexual behaviors, nonconsensual sexual relations, self-reported health, family whereabouts, and social well-being. In addition, the prevalence of laboratory and clinical diagnoses will be presented for the sample as a whole, as well as for key subgroups, including men, women, adults, and young persons. Quantitative questionnaire responses will be used to describe the epidemiology of test positivity and diagnoses. Sociodemographic and behavioral variables that are significantly associated with health outcomes of interest in bivariable analyses will be included in multivariable regression models to estimate strength of adjusted associations and test their significance.

Discussion

By 2050, the United Nations (UN) estimates that over 1 billion people could be displaced due to climate change alone.1,31 Many others are leaving their country of origin for work, family, conflict, persecution, and natural disasters. 1 This increase in population movement is already evident throughout the Americas, especially in Panama, where migrants from different Caribbean regions, South America, Africa, and Asia, travel through South and Central America en route to North America. Unfortunately, the world and Latin America are not prepared to provide medical care for mass migration.

PAHO has highlighted a need to strengthen both health surveillance and the monitoring of existing programs targeted toward migrant peoples in the region. 16 This rapid evaluation of health status and service provision among migrant peoples in transit aims to respond to this evidence gap. Employing a mixed qualitative and quantitative approach, the study will investigate the health status and needs among migrant peoples in transit passing through the Darien MRSs. Currently, individuals with acute illness or emergency health conditions, such as pregnancy, may be transferred to nearby MINSA health centers. However, the occurrence of other health conditions, such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, genitourinary syndromes, and tropical diseases, as well as mal/under-nutrition, remain largely undetected and ignored; information related to their prevalence among migrant peoples in transit through the region remain widely unknown.

As the demographics of migrants who opt for this perilous route shift, information related to the health needs of this population and opportunities for strengthening service provision at the MRS and regionally for migrant peoples in transit is essential. This study is critical to understand health priorities, especially with infectious and tropical disease, nutrition, mental health, and sexual and reproductive health of those who pass thorough the DF. In addition, findings could be used to optimize scarce resources targeted toward improving the well-being of migrant peoples who pass through this region. Previous research among people in transit in Central America and Mexico has led to recommendations to decriminalize irregular migration; 32 identify and stop human trafficking, particularly of women and children; 32 and expand the number of migrants’ shelters as a way to meet basic needs. 33 Furthermore, studies recommend better coordination and collaboration among governmental and nongovernmental organizations – and across borders – to prevent and control health problems faced by migrant people in transit. 33 Furthermore, researchers recommend improving access to primary health care, including sexually transmitted disease and HIV testing, among this population.33,34 To ensure that the results of this project inform programs and policies for migrants in transit, results and targeted intervention recommendations that will have emerged from the qualitative and quantitative studies will be presented locally to MINSA and international nongovernmental organizations that focus on service provision to migrant peoples.

Access to health care is a human right – increasing migrant health and health literacy translate into future social engagement, citizenship, and productivity. 35 The overarching goal of this project is to document the health needs of migrant peoples in transit who pass through Panama in order to provide initial surveillance information and recommendations for targeted interventions for this mobile population. To do this, the project will use POC testing and a comprehensive, easily deployable package of health services. Strengthening POC diagnosis and service delivery will be essential to address barriers to quality health care for migrant peoples who frequently have insufficient time to receive provider follow-up and continuity of care. The literature from other contexts of migration indicates that strategies to screen and treat migrant populations for transmissible diseases, including tuberculosis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV infection, enteric bacteria, and helminths, can be both impactful and cost-effective 36 in the control of infectious disease. Addressing these unmet health needs and improving service provision can help alleviate the incredibly marked inequities migrant peoples have experienced and sustained in their journey.

The challenges to deploy and deliver a point of health care for migrant peoples in transit are enormous – facing barriers including discrimination, violence, communication, and insufficient access to health care.4,37 Such issues have described a perceived idea of ‘deservingness’ that categorizes patients, particularly migrant peoples, as more or less deserving of access to quality health care. 38 There are few published data on health care needs of migrant peoples in transit through Latin America en route to the United States. Gray literature from UN and other international nongovernmental organizations suggest the greatest health needs include treatment of fever, skin problems, diarrhea and prenatal care. The successful implementation of a health screening protocol like our proposed study may become a platform to scale up in different migratory routes in the Americas and in other regions. Furthermore, the successful conduction of this study may provide crucial information to increase awareness and lead to effective targeted health care services for migrant peoples in transit.

Conclusion

The results of the qualitative and quantitative studies answer the PAHO call to contribute to a better understanding of the health status and health needs of migrant peoples in transit through Panama. It will also serve to strengthen interventions of national and decentralized health and surveillance systems nationally and regionally. Most importantly, the results from this study can be used to develop targeted interventions of health care provision for migrant peoples in transit through the DF and the Americas.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tai-10.1177_20499361211066190 for Rapid health evaluation in migrant peoples in transit through Darien, Panama: protocol for a multimethod qualitative and quantitative study by Amanda Gabster, Monica Jhangimal, Jennifer Toller Erausquin, José Antonio Suárez, Justo Pinzón-Espinosa, Madeline Baird, Jennifer Katz, Davis Beltran-Henríquez, Gonzalo Cabezas-Talavero, Andrés F. Henao-Martínez, Carlos Franco-Paredes, Nelson I. Agudelo-Higuita, Mónica Pachar, José Anel González, Fátima Rodriguez and Juan Miguel Pascale in Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Center for Research and Diagnosis of Emerging and Infectious Diseases, Meteti, Darien of the Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud, Community Development Network of the Americas, UNICEF, Médecins Sans Frontières, Panamás Ministerio de Salud, Servicio Nacional de Fronteras (SENAFRONT), and Servicio Nacional de Migración for their ongoing support. We are additionally thankful to those who have contributed thus far to this project: Acino Swiss Farma, Ann Knudson, and the Oklahoma University’s Physicians Pharmacy, Sagrav SA, and Omega Diagnostics.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Conceptualization: AG, MJ, JTE, JAS, JMP; funding acquisition: AG, FR, JMP, CFP, NAH; methodology: AG, MJ, JTE, JAS, JP, MB, JS, JK, CN, DB, CGT; project administration: AG, FR; supervision: JMP; validation: PM; visualization: AG; writing – original draft preparation: AG, MJ, JTE, AHM, JMP; writing – review & editing: AG, MJ, JTE, JAS, JP, MB, JS, JK, CN, DB, YZ, AHM, CFP, NAH, MP, FR, NG, JAG, GV, GCT, JMP.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding is provided by Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud (Panama), Community Development Network of the Americas, Acino Swiss Farma (donation), Neglected Tropical Diseases Fund and University of Colorado (donation by Mr. Howard Janzen). Additional donations have come from Sagrav SA and Omega Diagnostics, and a large proportion of the diagnostic tests have been donated through individual research funds from the National Research System (‘SNI’ by member Dr José Antonio Suárez).

ORCID iDs: Amanda Gabster  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7712-0444

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7712-0444

Monica Jhangimal  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2470-055X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2470-055X

Jennifer Toller Erausquin  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4271-6077

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4271-6077

José Antonio Suárez  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9407-1624

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9407-1624

Justo Pinzón-Espinosa  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3084-7793

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3084-7793

Madeline Baird  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3490-8722

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3490-8722

Jennifer Katz  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2686-1071

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2686-1071

Davis Beltran-Henríquez  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3183-3753

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3183-3753

Gonzalo Cabezas-Talavero  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0401-4621

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0401-4621

Andrés F. Henao-Martínez  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7363-8652

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7363-8652

Carlos Franco-Paredes  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8757-643X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8757-643X

Nelson I. Agudelo-Higuita  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9363-6280

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9363-6280

Mónica Pachar  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4400-4209

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4400-4209

José Anel González  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4285-2298

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4285-2298

Fátima Rodriguez  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3470-5258

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3470-5258

Juan Miguel Pascale  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3258-1359

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3258-1359

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Amanda Gabster, Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud, Ave Justo Arosemena, Calle 36 Ciudad de Panamá, Panama City, Panamá.

Monica Jhangimal, Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud, Panama City, Panamá.

Jennifer Toller Erausquin, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC, USA; National Research System, Secretariat of Science, Technology and Innovation, Panama City, Panama.

José Antonio Suárez, Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud, Panama City, Panamá.

Justo Pinzón-Espinosa, Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí, Sabadell, Spain.

Madeline Baird, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA.

Jennifer Katz, Community Development Network of the Americas, Panama City, Panamá.

Davis Beltran-Henríquez, Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud, Panama City, Panamá.

Gonzalo Cabezas-Talavero, Community Development Network of the Americas, Panama City, Panamá.

Andrés F. Henao-Martínez, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, USA

Carlos Franco-Paredes, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, USA; Hospital Infantil de Mexico, Federico Gomez, Mexico City, Mexico.

Nelson I. Agudelo-Higuita, The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA

Mónica Pachar, Hospital Santo Tomás, Panama City, Panamá.

José Anel González, Hospital Irma De Lourdes Tzanetatos, Panama City, Panamá.

Fátima Rodriguez, Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud, Panama City, Panamá.

Juan Miguel Pascale, Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud, Panama City, Panamá.

Migrant Peoples in Transit Study Group, Joanne Sánchez, Nathan Gundacker, Candy Nakad, Yamitzel Zaldívar, Fátima Rodriguez, Grace Vistica, Daniel Owen, Thomas Rincón, Máximo Gonzalez, Miliza Peralta, Florence JN Pierre, Stevenson Pierre, Miliza Peralta, Nelsón Cabezón, Eugenia Millender, Daniel Viquez, Anyi Yu Pon.

References

- 1. International Organization for Migration, UN Migration. World migration report 2020, 2020, https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/wmr_2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2. The UN Refugee Agency. Refugee data finder, 2021, https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/

- 3. Agudelo-Higuita NI, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Henao-Martinez AF, et al. The treacherous journey of hundreds of migrants from Cameroon to reach the United States. Travel Med Infect Dis 2021; 44: 102172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vyas K. Rapes of U.S.-bound migrants make a treacherous route even more dangerous. The Wall Street Journal, 6 September 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/rapes-of-u-s-bound-migrants-make-a-treacherous-route-even-more-dangerous-11630956539

- 5. Fitzgerald DS. Refuge beyond reach how rich democracies repel asylum seekers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gilman D. Barricading the border: COVID-19 and the exclusion of asylum seekers at the U.S. southern border. Front Hum Dyn 2020; 2: 595814. [Google Scholar]

- 7. TVN Noticias. Alrededor de 17 mil migrantes han transitado por Panamá en lo que va del 2021, TVN Noticias, 6 June 2021, https://www.tvn-2.com/nacionales/seguridad/Aproximadamente-mil-migrantes-transitado-Panama_0_5869662986.html

- 8. Servicio Nacional de Migración. Estadísticas, 2021, https://www.migracion.gob.pa/inicio/estadisticas

- 9. International Organization for Migration (IOM). Seguimiento a la emergencia: Septiembre 2020-Febrero 2021. IOM, 2021, https://displacement.iom.int/system/tdf/reports/REPORTE%20DE%20SITUACION-%2318-ERMS-COVID%2019%20%281%29.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=11318 [Google Scholar]

- 10. International Organization for Migration. Más de 91.000 migrantes han cruzado el Tapón del Darién rumbo a Norteamérica este año, 2021, https://www.iom.int/es/news/mas-de-91000-migrantes-han-cruzado-el-tapon-del-darien-rumbo-norteamerica-este-ano

- 11. Jaramillo OA. En 12 años, atravesaron la selva de Darién 188 mil 873 migrantes. La Prensa, 4 September 2021, https://www.prensa.com/impresa/panorama/en-12-anos-atravesaron-la-selva-de-darien-188-mil-873-migrantes/

- 12. Bensman T. A United Nations of mass illegal immigration, part 1, 2021, https://cis.org/Bensman/United-Nations-Mass-Illegal-Immigration-Part-1

- 13. UNICEF. Fifteen times more children crossing the Panama jungle towards the USA in the last four years, 2021, https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/fifteen-times-more-children-crossing-panama-jungle-towards-usa-last-four-years

- 14. Pinzón-Espinosa J, Valdés-Florido MJ, Riboldi I, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants. J Affect Disord 2021; 280: 407–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gabster A, Erausquin JT, Michielsen K, et al. How did COVID-19 measures impact sexual behaviour and access to HIV/STI services in Panama? Results from a national cross-sectional online survey. Sex Transm Infect. Epub ahead of print 16 August 2021. DOI: 10.1136/sextrans-2021-054985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Guidance document on migration and health. PAHO, 2019, https://www.paho.org/en/documents/guidance-document-migration-and-health [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kpokiri EE, Wu D, Srinivas ML, et al. Development of an international sexual and reproductive health survey instrument: results from a pilot WHO/HRP consultative Delphi process. Sex Transm Infect. Epub ahead of print 12 April 2021. DOI: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alasagheirin MH, Clark MK. Skeletal growth, body composition, and metabolic risk among North Sudanese immigrant children. Public Health Nurs 2018; 35: 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eurostat. European Health Interview Survey (EHIS wave 3) methodological manual. Publications Office of the European Union, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/8762193/KS-02-18-240-EN-N.pdf/5fa53ed4-4367-41c4-b3f5-260ced9ff2f6

- 20. Last JM, Adelaide DP. The iceberg: ‘completing the clinical picture’ in general practice. 1963. Int J Epidemiol 2013; 42: 1608–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rasmussen S, Søndergaard J, Larsen PV, et al. The Danish symptom cohort: questionnaire and feasibility in the nationwide study on symptom experience and healthcare-seeking among 100 000 individuals. Int J Family Med 2014; 2014: 187280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paik A. The contexts of sexual involvement and concurrent sexual partnerships. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2010; 42: 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gabster A, Pascale JM, Cislaghi B, et al. High prevalence of sexually transmitted infections, and high-risk sexual behaviours among indigenous adolescents of the Comarca Ngäbe-Bugle, Panama. Sex Transm Dis 2019; 46: 780–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gabster A, Mohammed DY, Arteaga GB, et al. Correlates of sexually transmitted infections among adolescents attending public high schools, Panama, 2015. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0163391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Condon S, Lieber M, Maillochon F. Feeling unsafe in public places: understanding women’s fears. Rev Fr Sociol 2007; 48: 101–128. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bellón JA, Delgado A, Luna J, et al. Cuestionario Apoyo Social Funcional de Duke. Med Care 1988; 26: 709–723.3393031 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Khaled Fahim N, Negida A. Sample size calculation guide – part 1: how to calculate the sample size based on the prevalence rate. Adv J Emerg Med 2018; 2: e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. International Organization for Migration. Analysis of flow monitoring surveys, 2019, https://dtm.iom.int/reports/panama-–-analysis-flow-monitoring-surveys-extrarregional-migrants-june-2019

- 29. Devries KM, Child JC, Elbourne D, et al. ‘I never expected that it would happen, coming to ask me such questions’: ethical aspects of asking children about violence in resource poor settings. Trials 2015; 16: 516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 2006; 5: 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 31. The Lancet. Climate migration requires a global response. Lancet 2020; 395: 839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Morales-Hernandes S. Central American migrants in transit through Mexico women and gender violence; challenges for the Mexican state. Procedia 2014; 161: 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lemus-Way MC, Johansson H. Strengths and resilience of migrant women in transit: an analysis of the narratives of Central American women in irregular transit through Mexico towards the USA. J Int Migr Integr 2020; 21: 745–763. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martinez-Donate AP, Verdecias N, Zhang X, et al. Health Profile and health care access of Mexican migration flows traversing the northern border of Mexico. Med Care 2020; 58: 474–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vissandjée B, Short WE, Bates K. Health and legal literacy for migrants: twinned strands woven in the cloth of social justice and the human right to health care. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2017; 17: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Panagiotopoulos T. Screening for infectious diseases in newly arrived migrants in Europe: the context matters. Euro Surveill 2018; 23: 1800283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jackson J. Drugs, migrants and rebels: life along Darién’s Gap. Al Jazeera, 17 May 2015, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2015/5/17/drugs-migrants-and-rebels-life-along-dariens-gap

- 38. Willen SS, Selim N, Mendenhall E, et al. Flourishing: migration and health in social context. BMJ Glob Health 2021; 6(Suppl. 1): e005108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tai-10.1177_20499361211066190 for Rapid health evaluation in migrant peoples in transit through Darien, Panama: protocol for a multimethod qualitative and quantitative study by Amanda Gabster, Monica Jhangimal, Jennifer Toller Erausquin, José Antonio Suárez, Justo Pinzón-Espinosa, Madeline Baird, Jennifer Katz, Davis Beltran-Henríquez, Gonzalo Cabezas-Talavero, Andrés F. Henao-Martínez, Carlos Franco-Paredes, Nelson I. Agudelo-Higuita, Mónica Pachar, José Anel González, Fátima Rodriguez and Juan Miguel Pascale in Therapeutic Advances in Infectious Disease