Abstract

Purpose

The presence of distinct child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and adult mental health services (AMHS) impacts continuity of mental health treatment for young people. However, we do not know the extent of discontinuity of care in Europe nor the effects of discontinuity on the mental health of young people. Current research is limited, as the majority of existing studies are retrospective, based on small samples or used non-standardised information from medical records. The MILESTONE prospective cohort study aims to examine associations between service use, mental health and other outcomes over 24 months, using information from self, parent and clinician reports.

Participants

Seven hundred sixty-three young people from 39 CAMHS in 8 European countries, their parents and CAMHS clinicians who completed interviews and online questionnaires and were followed up for 2 years after reaching the upper age limit of the CAMHS they receive treatment at.

Findings to date

This cohort profile describes the baseline characteristics of the MILESTONE cohort. The mental health of young people reaching the upper age limit of their CAMHS varied greatly in type and severity: 32.8% of young people reported clinical levels of self-reported problems and 18.6% were rated to be ‘markedly ill’, ‘severely ill’ or ‘among the most extremely ill’ by their clinician. Fifty-seven per cent of young people reported psychotropic medication use in the previous half year.

Future plans

Analysis of longitudinal data from the MILESTONE cohort will be used to assess relationships between the demographic and clinical characteristics of young people reaching the upper age limit of their CAMHS and the type of care the young person uses over the next 2 years, such as whether the young person transitions to AMHS. At 2 years follow-up, the mental health outcomes of young people following different care pathways will be compared.

Trial registration number

Keywords: child & adolescent psychiatry, adult psychiatry, international health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The MILESTONE cohort study is the first study to prospectively examine the longitudinal association of service use and mental health outcomes over a 2-year follow-up period using information from young people themselves, their parents and their clinicians.

Recruitment of child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) users within a wide range of services across eight countries resulted in a heterogeneous patient-population, which is very suitable for describing how sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are associated with the type of care young people receive in the 2 years after reaching the upper age limit of their CAMHS, irrespective of culture, mental health systems and transition policy.

Although the representativeness of the cohort may be affected by a selection bias and selective drop-out, it is unlikely that these will affect the validity of regression models investigating relationships between precursors and outcomes.

Introduction

The presence of distinct child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and adult mental health services (AMHS) impacts continuity of mental health treatment for young people.1 2 However, we do not know how many young people experience discontinuity, nor how this discontinuity may affect the mental health of young people reaching the upper age limit of the CAMHS they receive treatment at. Previous research reports a large variation in the proportion of CAMHS users that do not transition to AMHS, ranging from 30% to 84%.3–9 There are a few studies examining how demographic and clinical characteristics of CAMHS users are associated with transitioning to AMHS. These studies are consistent in showing that indicators of severity of psychopathology, such as a clinical classification of a bipolar or psychotic disorder, inpatient care and psychotropic medication use, are associated with a greater likelihood of transition to AMHS.3–5 7 10–12 However, the results are inconsistent with regard to sociodemographic characteristics, such as gender and living situation, or other factors such as the length of CAMHS use.3–5 7 10 11 Most existing studies have been retrospective and used unstandardised information from medical records.3–5 8 10 11 Only few prospective studies have been conducted, mostly in small samples, within one CAMHS or within subsamples such as young people with autism spectrum disorders (ASD).6 7 12 Only 1 study,12 investigating 118 young people with ASD, included self-reported and parent-reported information. To date, no studies have been conducted that compare longitudinal mental health outcomes of young people who transition to AMHS with those who do not.13

The MILESTONE cohort study was designed to prospectively examine service use, mental health and other outcomes over a 2-year follow-up period, in a cohort of 763 young people who have reached the upper age limit of their CAMHS in 8 European countries. The aims of the MILESTONE cohort study are to (1) assess the relationships between demographic and clinical characteristics of young people reaching the upper age limit of their CAMHS, whether the young person is referred from CAMHS to AMHS and the type of care the young person uses over the next 2 years, such as whether the young person transitions to AMHS; (2) determine the mental health outcomes of young people following different care pathways after 2 years follow-up. This cohort profile describes demographic and clinical characteristics of young people at baseline only.

Cohort description

Study design and participants

A cluster randomised trial (NCT03013595) was embedded within the longitudinal cohort study, of which the protocol has been previously described by Singh et al.14 A total of 52 CAMHS in 8 countries (Belgium, Croatia, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK) agreed to participate and fitted the service inclusion criteria: a service delivering medical and psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents with mental health problems or disorders and/or neuropsychiatric/developmental disorders, with a formal upper age limit for providing care and responsible for transfer of care to adult services. Highly specialised services for rare disorders and forensic services were excluded.14 Thirty-nine CAMHS were included in this cohort study (4 in Belgium, 2 in Croatia, 4 in France, 2 in Germany, 2 in Ireland, 8 in Italy, 6 in the Netherlands and 11 in the UK; see online supplemental table 1 for the number of participants recruited per country), which varied in size and types of services offered, including services run by a single psychiatrist/psychologist and services with multiple locations and teams. Thirteen CAMHS were excluded as they were in the trial intervention arm in which ‘managed transition’ was implemented. Managed transition included a structured assessment of young people regarding transition readiness and appropriateness, the results of which were fed back to CAMHS clinicians.14

bmjopen-2021-053373supp001.pdf (140.2KB, pdf)

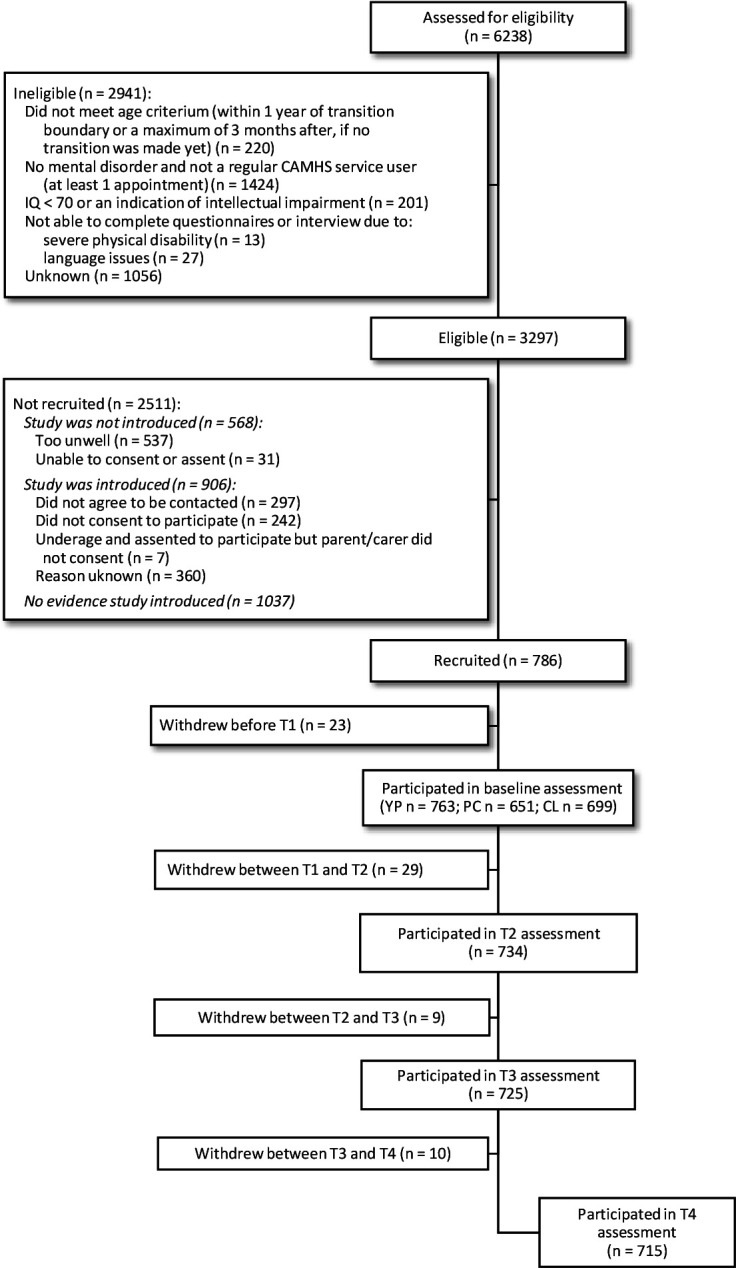

Young people

Figure 1 describes the flow of participants in the process of assessing eligibility, recruitment and follow-up. Between October 2015 and December 2016, CAMHS databases were scanned by local personnel, screening for eligible participants, that is, young people within a year of the upper age limit of the specific CAMHS (or 3 months after, if still in CAMHS) (n=6238). The upper age limit of the participating CAMHS was 18 years for two-thirds of services, or applied flexibly, varying between 16 and 19 years of age. A care coordinator and/or clinician assessed the young people for study inclusion criteria and sought the young person’s consent to be approached by a MILESTONE research assistant. In addition to the age criterion, the following inclusion criteria were applied: eligible young people had a mental disorder or were regular CAMHS service users, had an intelligence quotient (IQ) over 70 or no indication of intellectual impairment and were able to complete questionnaires and interviews (also see figure 1). The research assistant contacted the young person (and their parents, if the young person was legally a minor) with information about the study and consent forms. Country-specific consent procedures were followed, according to national laws as well as medical ethical committee regulations. A parent/carer (referred to as parents from hereon) and the young person’s main CAMHS clinician, or a mental health professional responsible for, or coordinating, the care for the young person, were also asked to participate in the study. The first assessment took place after consent was provided.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participants according to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT). CL, clinician; PC, parent/carer; YP, young person.

All participants in MILESTONE were to be followed up over a period of 2 years, in which three follow-up assessments took place (9, 15 and 24 months after baseline). Before each assessment, the participant was contacted by a research assistant and asked whether they would participate in the next assessment, after which the assessment would be planned (within a month of the calculated assessment timepoint, that is, between 8 and 10 months after baseline for the second assessment). A total of 48 young people (6.3%) withdrew from the study within this 24-month period. In addition, not all participating young people completed all measures at all timepoints: a total of 631 (82.7%) young people completed 1 or more questionnaires or interviews at 9 months follow-up, 573 (75.1%) at 15 months follow-up and 533 (69.9%) at 24 months follow-up.

Parents/carers and clinicians

In addition, a total of 651 parents and 699 CAMHS clinicians were recruited for completion of parent and clinician reported outcome measures. If a young person left CAMHS and moved onto a new service, a clinician from the new service was asked to participate. A total of 492 (reporting on 64.5% of young people) parents completed 1 or more questionnaires or interviews at 9 months follow-up, 473 (62.0%) and 432 (56.6%) parents completed measures at 15 and 24 months follow-up, respectively. The number of young people for whom a clinician provided any clinical information was 429 (56.2%) at 9 months, 222 (29.1%) at 15 months and 183 (24.0%) at 24 months follow-up. Among young people who reported receiving mental healthcare, clinical information was available for 85.0%, 72.6% and 69.5% at 9, 15 and 24 months, respectively.

Measures and procedure

At baseline and 24 months follow-up, assessments took place in the clinic, the participant’s home or other convenient location and lasted approximately 2 hours. To limit the burden on participants, the most important interviews and questionnaires were repeated at 9 and 15 months, most interviews were conducted by phone (some face-to-face) and questionnaires were completed online. Young people and parents were interviewed separately by the local MILESTONE research assistant and asked to complete a set of questionnaires online on the web-based HealthTracker platform.14 Paper and pencil were used when the HealthTracker platform could not be accessed. Measures that were not available in all languages (English, Dutch, Italian, Croatian, French and German) were translated and back translated before use. All research assistants were trained to administer the interviews and questionnaires and attended monthly international research assistant meetings by phone to ensure adherence to standard operating procedures and consistency between sites, countries and over time. Most young people received a gift voucher after completing the assessment (gift vouchers had a maximum value of €25; research ethics committees in Italy and Croatia did not allow gift vouchers) and travel costs were reimbursed.

An overview of the measures used in the MILESTONE cohort study is provided in table 1. The interviews focused on capturing information about the young person and parent’s sociodemographic information and the young person’s mental health in the 2 weeks prior to the assessment. This enabled completion of the Health of the Nation Outcome Scale for Children and Adolescents (HoNOSCA).15 Online questionnaires were used to assess emotional and behavioural problems, need for care, psychotic experiences, quality of life, everyday functional skills, independent behaviour, illness perception, life events and bullying, service and medication use, transition readiness and appropriateness. The clinician provided clinical information (and/or medical notes were reviewed, if accessible) which included clinical classifications registered in the medical records (based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders version IV or 5 and the International Classification of Diseases version 10), the Clinical Global Impression—Severity (CGI-S) and demographic information. The clinician was also asked to provide information for the purpose of rating the HoNOSCA (supplementing information from young person and/or parent interviews), if they had seen the young person within the past 2 weeks.

Table 1.

Measures

| Construct | Informant (method): assessed at m f-u* | Instruments | Description | Psychometrics | Scoring |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | YP (I): 0, 9, 15, 24 PC (I): 0, 24 |

The sociodemographic interview was largely based on the Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory EU version (CSSRI-EU).25 Items on medical history were added. | Assessing sociodemographic variables, such as living situation, education, and medical history. Within the medical history domain of the interview, the RA also assessed lifetime suicide attempt(s), as indicated by the YP with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the question ‘have you ever tried to commit suicide?’. | Psychometric properties of CSSRI-EU for assessing sociodemographic variables are not available, but the instrument has been validated in a large European study on mental health: EPSILON (European Psychiatric Services: Inputs linked to Outcome Domains and Needs).25 | Categorical answer categories |

| Family characteristics | PC (I): 0, 24 | Sociodemographic interview (PC-version) | Highest level of PC education of either parent (‘What is your highest completed level of education?’) and (history of) psychopathology in biological parents (‘Were you ever examined or treated for mental, developmental, language, speech or learning problems?’) was assessed in the sociodemographic interview. | The item on level of education came from the CSSRI-EU (see psychometrics for sociodemographic characteristics). | Categorical answer categories |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Clinical classifications | CL (I): 0, 9, 15, 24 | Clinical classifications (based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version IV or 5 and the International Classification of Diseases, version 10)26 27 | Official clinical diagnosis classifications registered in the medical records (or, if no official diagnosis was registered: the preliminary/working diagnosis registered) | Clinical classifications are dummy coded and indicate presence or absence of a specific clinical classification or category. | |

| Emotional and behavioural problems | YP (OQ: 0, 9, 15, 24 PC (OQ): 0, 9, 15, 24 |

Youth Self-Report (YSR) Adult Self-Report (ASR) Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) Adult Behaviour Checklist (ABCL) |

YP (YSR/ASR) and PC reported (CBCL/ABCL) emotional and behavioural problems in the last 6 months in versions for YP under (YSR/CBCL) or over (ASR/ABCL) 18 years old. | The Achenbach System of Empirically-Based Assessment28 29 (ASEBA) instruments have been used extensively in different contexts and have shown excellent psychometric properties. | Raw scores were converted to t-scores (with a mean of 50 and a SD of 10) to allow comparison between ASEBA measures. Norm scores were used to differentiate between normal, borderline clinical, and clinically scoring young people.28 29. Higher scores indicate more emotional/ behavioural problems. |

| Clinician rated severity of psychopathology | CL (I): 0, 9, 15, 24 | Clinical Global Impression—Severity scale (CGI-S) | CL rated severity of psychopathology over the last week relative to other patients with similar problems. | The CGI-S30 is extensively used in psychiatric research31 and has proven useful in predicting suicidal ideation and behaviours.32. | Single score measuring severity on a 7-point scale (higher scores indicating more severe problems). The CGI-S was used as a categorical variable in the analyses, with the following categories ‘not at all ill’ (score=1), ‘borderline/mildly/moderately ill’ (scores 2–4) and ‘markedly or more severely ill’ (scores 5–7). |

| Need for care | YP (I): 0, 9, 15, 24 PC (I): 0, 9, 15, 24 CL (I): 0, 9, 15, 24 |

The Health of the Nation Outcome Scale for Children and Adolescents (HoNOSCA) | Assesses YP’s health and need for care in the last 2 weeks. In the MILESTONE study, the HoNOSCA is rated by trained research assistants, based on the ‘mental health’-interview with the YP, PCs, the CL and/or medical records. | Good interrater reliability cross-nationally33, face validity and sensitivity to change in clinical use15 in adolescent CAMHS patients specifically. Within MILESTONE, research assistants were trained and regular meetings were held to discuss scoring issues and to improve scoring reliability. | Total score (ranging 0–52) of 13 health related domains ranging 0–4. Higher scores indicate more severe problems. Domains 14 and 15 are related to lack of information and access of services and not used in computing the HoNOSCA total mental health score. |

| Psychotic experiences | YP: 0, 24 | Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) | DAWBA34 assesses a range of psychiatric diagnoses through structured sections of the online questionnaire, among which psychotic experiences. The open sections of the DAWBA were omitted to limit the burden on the participants and to standardise the classification procedure. | The DAWBA psychotic experiences section proved valuable as a screening tool in the youth general population (it has not yet been validated in a clinical sample).35. | Respondents indicated whether the young person experienced a range of psychotic experiences, with response options ‘no’, ‘a little’, and ‘a lot’. The total number of a total of 10 experiences the young person experienced (either a little or a lot) was calculated. |

| Service use | |||||

| Service (& medication) use in the past 6 months | YP (OQ): 0, 9, 15, 24 | CSSRI-EU (amended for use in a psychiatric setting) | Assesses inpatient and outpatient service use over the last 6 months in different settings (hospital, community and informal) and medication use over the last 6 months. | The CSSRI-EU was found to be effective in tracing patterns of service use in an international population and made comparisons between different countries possible.25 | Dichotomous service use score over different service use types and quantity of service use (number of nights spent or number of visits multiplied by their average duration) |

| Current mental healthcare | YP (I): 0, 9, 15, 24 | Part of sociodemographic interview | Current mental healthcare was assessed with the questions ‘Are you currently using a mental health service?’ and ‘What mental health service are you currently accessing?’. The research assistant administering the interview could help the young person identify what type of care the young person was in care at if necessary. | Categorical answer categories | |

| Transition readiness and appropriateness | YP (OQ): 0 PC (OQ): 0 CL (OQ): 0 |

Transition Readiness and Appropriateness Measure (TRAM) | The TRAM assessed the clinician’s transition recommendations and the availability of appropriate services (both in the CL version of the TRAM). The YP-version and PC-version were used to assess young people’s and parents’ need for ongoing treatment. | The TRAM has been established to be a reliable instrument for assessing transition readiness and appropriateness.36 | Categorical answer categories |

| Impairment and functioning | |||||

| Quality of life | YP (OQ): 0, 15, 24 | World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Inventory (WHOQOL-BREF) | YP reports on quality of life in the last 2 weeks. | The WHOQOL-BREF has excellent psychometric properties.37 Internal consistency for assessing quality of life in adolescents is good and the instrument validly discriminated between adolescents with low and high levels of depressive symptoms.38 | To allow comparison to the WHOQOL-10037, mean domain scores were calculated and multiplied by 4, yielding a 4–20 transformed mean score of quality of life score in 4 domains: psychological, physical, social and environmental quality of life. Higher scores indicate a higher quality of life. |

| Everyday functional skills | PC (OQ): 0, 15, 24 | Specific Levels of Functioning (SLOF) | Assesses YP’s everyday functional skills, ‘emphasizing patient’s current functioning and observable behaviour, as opposed to inferred mental or emotional states’.39 | The SLOF domains have acceptable internal consistencies (except for a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.55 for physical functioning) and good concurrent validity.40 | Average everyday functional skill-scores ranging from 1 to 5 on 6 domains: physical functioning, personal care, interpersonal relationships, social acceptability, activities and work skills, with higher scores indicating more everyday functional skills. |

| Independent behaviour | YP (OQ): 0, 9, 15, 24 | The Independent Behaviour During Consultations Scale (IBDCS) | YPs report on their independent behaviour on a 5-point Likert scale. | Independence is a construct sensitive to change at the age of emerging adulthood and closely related to self-efficacy.41 | Average score of 7 items ranging from 0 to 4 (with higher scores indicating more independence). |

| Illness perception | YP (OQ): 0. 24 | Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ) | Assesses the young person’s perception of their disorder. | The B-IPQ has been used extensively in medical research and to a lesser extent in psychiatric research specifically, and has good test-retest reliability and concurrent validity.42 43 | Average score per item ranging from 0 to 10 (higher scores indicating higher perceived threat). |

| Experiences | |||||

| Life events | YP (OQ): 0, 9, 15, 24 | Instrument developed specifically for MILESTONE to assess life events | 13-item scale assessing 13 different life events such as accidents, deaths, separation over the last 9 months. | Total score indicating the number of life events experienced (ranging 0 to 13). | |

| Bullying | YP (OQ): 0, 24 | Adapted from Retrospective Bullying and Friendship Interview Schedule | Assesses the YP’s experiences with bullying in different settings (school, at home, college). | The Retrospective Bullying and Friendship Interview Schedule has previously been used in various populations and was found to be predictive of mental health.44 45 | Bullying experiences were classified in four groups: YP who were the victim of bullying (victim), YP who were both the victim of bullying and bullied themselves as well (bully/victim), YP who bullied (bully) and YP who were not involved in bullying (non-involved). |

*m f-u=months of follow-up.

CAMHS, child and adolescent mental health services; CL, clinician; I, interview; OQ, online questionnaire; PC, parent/carer; YP, young person.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was embedded in the MILESTONE cohort study and trial, by involving 10 young service users and carers from England and Ireland with experience of transition in mental health services from the outset. They provided feedback on the protocol and study documents; reviewed the outcomes measures and other study tools to ensure these were clear and not overly onerous for young people to complete; designed the intervention leaflet and other promotional materials; attended and contributed to project steering committee meetings; advised on recruitment and the engagement of young people; contributed to drafting the manuscripts and made presentations at local and national events. In the later stages of MILESTONE, nine parent/carers from across the north of England advised on the study dissemination outputs.

Missing data

Whether specific measures were administered to participants was dependent on whether or not the young person was using services at the time of assessment, and which type of services. Additionally, clinician participation at a particular assessment was entirely dependent on the young person’s service use. Due to an increasing proportion of young people no longer using services at follow-up assessments, the proportion of missing data at follow-up for measures such as clinician-rated severity of psychopathology (CGI-S) increased from 16.1% at T1, to 50.5% at T2, 76.9% at T3 and 81.1% at T4. Important outcome measures such as self-reported emotional and behavioural problems (Youth Self-Report/Adult Self-Report (YSR/ASR)), parent-reported emotional and behavioural problems (Child Behaviour Checklist/Adult Behaviour Checklist (CBCL/ABCL)) and mental health problems assessed with HoNOSCA were administered at every timepoint. For these measures, the proportions of missing data per timepoint were: 10.5% at T1, 26.9% at T2, 33.2% at T3 and 37.4% at T4 for Y/ASR; 25.0% at T1, 37.5% at T2, 46.0% at T3 and 50.6% at T4 for C/ABCL and; 3.9% at T1, 18.7% at T2, 28.3% at T3 and 31.1% at T4 for HoNOSCA.

Patterns of missing data on severity of psychopathology (CGI-S) and problem levels (Y/ASR and C/ABCL) at baseline are presented in online supplemental table 2. Information from the parent was more frequently missing when young people reported more emotional/behavioural problems and when the clinician reported the young person was either ‘not at all ill’ or ‘markedly ill or more severe’. Missing information on young people’s or clinician’s assessment of severity of psychopathology was not associated with problem levels reported by the other informants.

The 48 young people who withdrew between the first and last assessment at 24 months follow-up had lower Y/ASR mean item scores at baseline (M=0.44, SD=0.25) than young people who did not withdraw (M=0.57, SD=0.28; t(38.915)=−2.910, p=0.006). Young people who withdrew did not differ from young people who did not withdraw on CGI-S scores (t(39.538)=1.339, p=0.188) and mean C/ABCL item scores (t(33.289)=1.112, p=0.274) at baseline. Young people who withdrew during follow-up were more likely to have a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (14.6%) than those who did not withdraw (4.3%; χ2 (1, n=763)=7.934, p=0.005). Young people who withdrew did not differ from those who did not withdraw with regard to clinical classifications of depressive disorders (χ2 (1, n=763)=0.848, p=0.357), anxiety disorders (χ2 (1, n=763)=3.604, p=0.058), ASD (χ2 (1, n=763)=309, p=0.579) or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (χ2 (1, n=763)=2.360, p=0.125). We also did not find differences between young people who withdrew and those who did not with regard to gender (χ2 (1, n=763)=1.017, p=0.313) or parental educational level (χ2 (2, n=569)=4.449, p=0.108) at baseline.

Findings to date

This cohort profile describes the demographic and clinical characteristics of young people in the MILESTONE cohort as they reach the upper age limit of their CAMHS (i.e., results from young people’s baseline assessments only). The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram (figure 1) illustrates recruitment of young people to the cohort study (n=763). Online supplemental table 1 provides an overview of the recruitment process by country. A total of 6238 young people attending CAMHS, approaching the service boundary of their respective service, were assessed for eligibility. During this process, many young people who had been included in the first database screening were found to be ineligible, as they were either no longer under treatment or were now too old to be recruited. A total of 3297 young people was found eligible, of which 568 (17.2%) were considered too unwell or unable to consent by their clinicians during the recruitment period. Care coordinators and clinicians introduced the MILESTONE study to 1692 (51.3% of all eligible) young people. For 1037 (31.5% of all eligible) young people, the research assistant did not have evidence that the study had been introduced and therefore could not contact the young person. Of all young people to which the study was introduced, a total of 297 (17.6%) did not agree to be contacted, 242 young people (14.3%) did not consent to participate and 7 young people (0.4%) were underage and had parents who did not consent. Of all young people to whom the study was introduced, 763 young people (45.1%) consented to participate and completed in the first assessment (before the first assessment, 23 young people withdrew). A total of 651 parents and 318 CAMHS clinicians (linked to 699 young people, as some clinicians treated more than one participant) were also included in the study.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics of the 763 young people in the MILESTONE cohort are presented in table 2. The age of recruited young people ranged from 15.2 to 19.6 years, with a mean of 17.5 years (SD=0.59). This corresponds with the upper age limits of the CAMHS, which ranged from 16 to 19 years, with a median age of 18 years. Demographic characteristics of parents and clinicians are presented in online supplemental table 3.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of young people in the MILESTONE cohort

| n (%) or mean (SD) | |

| Gender (female) | 458 (60.0%) |

| Age | 17.50 (0.59) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 578 (75.8%) |

| Other | 62 (8.1%) |

| Missing | 122 (16.0%) |

| Living situation | |

| With biological parents | 392 (51.4%) |

| With one biological parent | 244 (32.0%) |

| Adoptive/foster parent(s) | 16 (2.1%) |

| Alone/with roommates or partner | 10 (1.3%) |

| Residential | 27 (3.5%) |

| Other | 28 (3.7%) |

| Missing | 46 (6.0%) |

| Current education | |

| Secondary/vocational | 629 (82.4%) |

| Higher (under/postgraduate) | 10 (1.3%) |

| None | 74 (9.7%) |

| Missing | 50 (6.4%) |

Note: percentages are based on n=763 for the total group.

Clinical characteristics

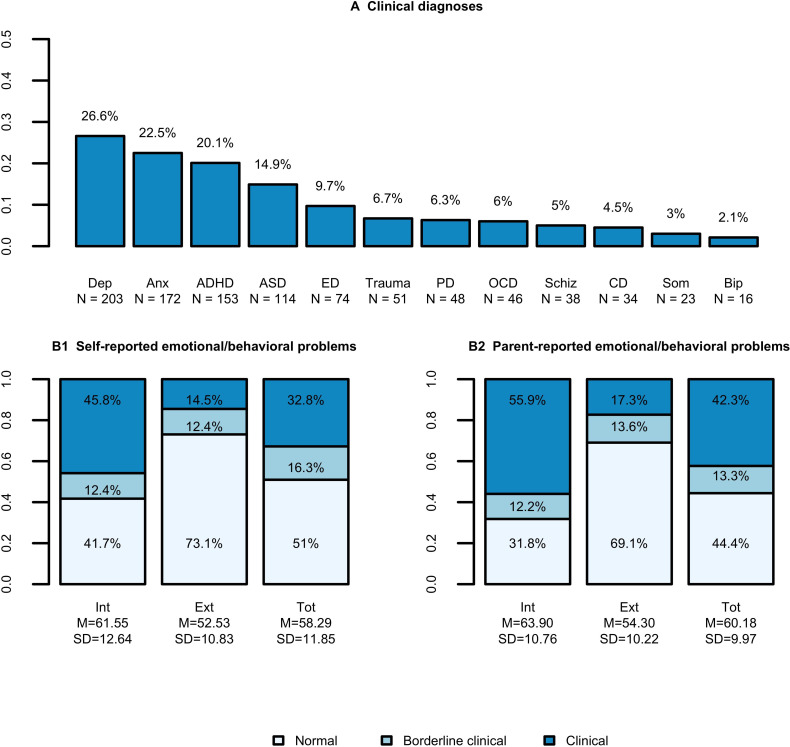

All measures are described in table 3 and figures 2 and 3.

Table 3.

Severity of mental health problems, impairment and functioning and experiences of the MILESTONE cohort

| n | Mean (SD), median (IQR) or n (%)* | |

| Severity of mental health problems | ||

| Clinician rated severity of psychopathology (CGI-S) | 640 | |

| Not at all ill | 60 (7.9%) | |

| Borderline/mildly/moderately ill | 438 (57.4%) | |

| Markedly ill or more severe | 142 (18.6%) | |

| Missing | 123 (16.1%) | |

| Mental health (HoNOSCA; range 0–52) | 734 | 11.65 (6.73) |

| Lifetime suicide attempt | 698 | |

| Yes | 196 (25.7%) | |

| No | 502 (65.8%) | |

| Missing | 65 (8.5%) | |

| Non-accidental self-injury (HoNOSCA domain) | 732 | |

| No problem of this kind | 566 (74.2%) | |

| Occasional thoughts about death, or of self-harm not leading to injury. No self-harm or suicidal thoughts. | 73 (9.6%) | |

| Non-hazardous self-harm whether or not associated with suicidal thoughts | 62 (8.1%) | |

| Moderately severe suicidal intent or moderate non-hazardous self-harm | 21 (2.8%) | |

| Serious suicidal attempt or serious deliberate self-injury | 10 (1.3%) | |

| Missing | 31 (4.1%) | |

| Impairment and functioning | ||

| Quality of life (WHOQOL-BREF; range 4–20) | 692 | |

| Psychological | 12.03 (3.54) | |

| Physical | 14.71 (2.67) | |

| Social | 13.65 (3.27) | |

| Environmental | 15.02 (2.62) | |

| Everyday functional skills (SLOF; range 1–5) | 579 | |

| Physical functioning | 5.00 (4.80, 5.00) | |

| Personal care skills | 5.00 (4.57, 5.00) | |

| Interpersonal relationships | 3.71 (3.00, 4.57) | |

| Social acceptability | 4.57 (4.29, 5.00) | |

| Activities | 4.73 (4.27, 4.91) | |

| Work skills | 4.17 (3.33, 4.67) | |

| Illness perception (B-IPQ; range 0–10) | 610 | 5.47 (1.68) |

| Independent behaviour (IBDCS; range 0–4) | 683 | 1.88 (0.91) |

| Experiences | ||

| Life events (range 0–13) | 684 | 2.00 (1.00, 3.00) |

| Bullying | 685 | |

| Victim | 310 (40.6%) | |

| Bully/victim | 116 (15.2%) | |

| Bully | 24 (3.2%) | |

| Non-involved | 235 (30.8%) | |

| Missing | 78 (10.2%) |

*Percentages are based on n=763 for the total group.

B-IPQ, Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression—Severity; HoNOSCA, Health of the Nation Outcome Scale for Children and Adolescents; IBDCS, Independent Behaviour During Consultations Scale; SLOF, Specific Levels of Functioning; WHOQOL-BREF, World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Inventory.

Figure 2.

Psychopathology. (A) proportions of young people with a specific clinical classification were based on a total n of 763, information on clinical classifications was not available for 29 (3.8%) of young people (either information on clinical classification was missing or the young person (YP) did not have clinical classification registered), only categories with n>10 are presented, comorbid disorders are included (each YP could have more than one diagnosis). (B) The Achenbach System of Empirically-Based Assessment scores reported are t-scores; 60–63=borderline clinical scores, ≥64 = clinical scores; Int=internalising problems, Ext=externalising problems, Tot=total emotional/behavioural problems. ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (/hyperkinetic disorders); Anx, anxiety disorders; ASD, autism spectrum disorders; Bip, bipolar disorders; CD, conduct disorders; Dep, depressive disorders; ED, eating disorders; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorders; PD, personality disorders; Schiz, schizophrenia spectrum disorders; Som, somatic symptom disorders; Trauma, trauma/stressor disorders.

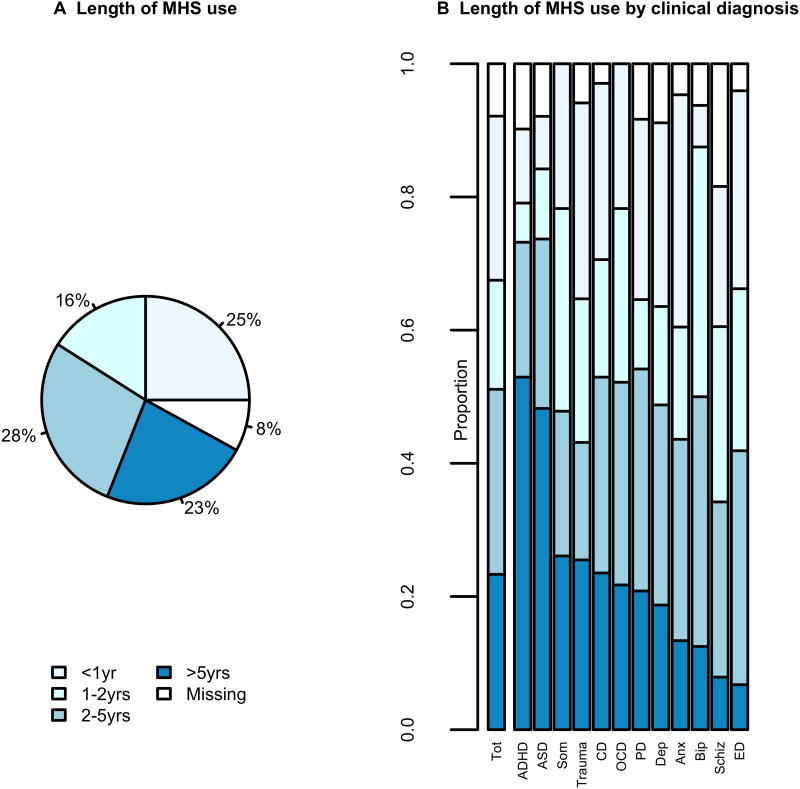

Figure 3.

Mental health service (MHS) use. Note: only diagnosis classifications with n>10 are presented. Anx, anxiety disorders; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (/hyperkinetic disorders); ASD, autism spectrum disorders; Bip, bipolar disorders; CD, conduct disorders; Dep, depressive disorders; ED, eating disorders; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorders; PD, personality disorders; Schiz, schizophrenia spectrum disorders; Som, somatic symptom disorders; Trauma, trauma/stressor disorders.

Clinical classifications

Figure 2A shows the prevalence of clinical classifications of the MILESTONE cohort. The most common clinical classifications were depressive disorders (26.6%) followed by anxiety disorders (22.5%), attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (ADHD; 20.1%) and ASD; 14.9%. Fifty-eight per cent (n=443) of young people had one classification, 27.9% (n=213) had two classifications, and 10.2% (n=78) had three or more classifications. Among those with more than one classification (n=291), the most prevalent comorbidities were depressive disorder and anxiety disorder (n=32, 11.0%), ADHD and ASD (n=19, 6.5%) and ADHD with an anxiety disorder (n=11, 3.8%).

Emotional and behavioural problems

Figure 2B shows the proportion of normal, borderline and clinically scoring young people as well as the mean scores on total, internalising and externalising scales for both self-reported (YSR and ASR) and parent-reported (CBCL and ABCL) problems. About a third (32.8%) of young people and 42.3% of parents reported problems in the clinical range on the total problems scale, with more young people scoring in the clinical range of the internalising scale than in the externalising scale (both self and parent-reported).

Severity of mental health problems

Severity of psychopathology scores provided by the clinician on the CGI-S are presented in table 3. A total of 18.6% (n=142) of young people were rated to be ‘markedly ill’, ‘severely ill’ or ‘among the most extremely ill’ by the clinician over the past week. Lifetime and current suicidality as well as psychotic experiences were assessed as indicators of severity of psychopathology. A quarter of young people (25.7%) reported having tried to commit suicide. Thirty-one (4.1%) young people were rated to have suicidal intent or attempted suicide in the past 2 weeks (assessed with the ‘non-accidental self-injury domain of the HoNOSCA, with a score of 3 indicating ‘moderately severe suicidal intent or moderate non-hazardous self-harm’ and 4 indicating a serious suicidal attempt or serious deliberate self-injury). One in three young people (n=250; 32.8%) reported ever having one or more psychotic experiences, while 330 young people reported never having psychotic experiences (43.3%). Information on psychotic experiences was missing for 183 young people (n=24.0%). The total HoNOSCA score is another method for assessing the severity of mental health problems. Online supplemental figure 1 presents mean scores for the different HoNOSCA items. Young people scored highest (most severe and impairing problems) on ‘problems with emotional and related symptoms’ (M=1.97, SD=1.20) and ‘problems with overactivity, attention or concentration’ (M=1.33, SD=1.12).

Service use

Length of service use

The duration of service use varied from less than 1 year to more than 5 years (figure 3A). Young people with neurodevelopmental disorders had been attending CAMHS longest, with roughly half for more than 5 years (figure 3B). Those with disorders that most frequently emerge in adolescence/young adulthood, such as personality, mood, eating and schizophrenia spectrum disorders were less likely to have been attending CAMHS for more than 5 years, yet a third to more than half of young people with these disorders had been attending CAMHS for 2 years or longer.

Type of service use

Young people who visited mental health professionals in an outpatient setting (n=544; 71.3%; assessed with the Client Sociodemographic and Service Receipt Inventory EU version) visited their clinician with a median of 10 times in the previous half year (IQR=4–21.3). Young people who were admitted to a residential psychiatric facility or a residential rehabilitation setting (n=66, 8.7%) spent a median of 48.5 nights in this facility in the previous 6 months (IQR=12.0–91.8). Thirty-six per cent of young people had visited their general practitioner in the 6 months before baseline assessment (n=277) and 11.1% had visited an emergency department (n=85; whether this visit was for mental health problems or other health problems is unknown). Fifty-seven per cent of young people (n=436) reported having used psychotropic medication in the previous half year. One in three young people used one type of psychotropic medication (n=224, 29.4%), 24.6% (n=188) used two or three different psychotropic medications and 3.1% (n=24) used four to five different psychotropic medications. Antidepressants were taken by almost one in three young people (n=216, 28.3%), psychostimulants by 14.4% of young people (n=110), antipsychotics by 12.1% (n=92), melatonin by 5.5% of young people (n=42) and 5.6% used benzodiazepines (n=43).

Impairment and everyday functional skills

Quality of life

Participants reported lowest on the psychological quality of life domain of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Inventory compared with the other quality of life domains (table 3).

Everyday functional skills and independent behaviour

The level of physical functioning and personal care (measured with the Specific Levels of Functioning) of the majority of young people was assessed as self-sufficient by their parents (table 3). Independent behaviour during clinical consultations (with the Independent Behaviour During Consultations Scale) was also generally rated fairly highly. More than two-thirds of young people (n=500, 65.5%) regularly or more frequently participated in decisions regarding their treatment. Almost half of young people (n=334, 43.8%) attended consultations on their own regularly or more frequently.

Illness perception

Young people scored between 5 and 6 on the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire on average, with scores ranging 0–10 (see table 3). In general, young people were most negative about how long the illness would continue (item mean of 6.89, SD=2.91 on a scale of ‘a very short time’ (0) to ‘forever’ (10)), yet moderately positive with regard to how well they felt they understood their illness (item mean=3.05, SD=2.56 on a scale of ‘very clearly’ (0) to ‘not at all’ (10)).

Experiences

One in five young people (n=160, 21.0%) reported that they had experienced no serious life events in the past 9 months, 41.5% had experienced one or two events (n=317) and 27.0% of young people (n=206) had experienced three life events or more (table 3).

Overall, having been bullied was more prevalent than bullying others: 40.6% of young people had been the victim of bullying in the past and 15.2% of young people had both been victimised and bullied others (table 3). Only 3.2% had bullied others without having been bullied themselves. A third (30.8%) of young people had experienced neither.

Strengths and limitations

The MILESTONE cohort study has a number of strengths, such as its prospective design with a 2-year follow-up, and the recruitment of multiple informants. Standardised assessments were used to collect data on clinical characteristics, impairment and functioning, experiences and sociodemographic information. Additionally, the study had strong patient and public involvement. The 39 participating CAMHS reflect a wide range of services, varying in size and ranging from community to specialist and/or academic hospital-based services in countries with differences in culture, training and concepts of mental health as well as differences in mental health policy and service organisation.

There are also several potential limitations to the MILESTONE cohort study. The first and most important limitation pertains to the representativeness of the MILESTONE cohort, due to potential selection bias. The CAMHS from which young people were recruited were not selected randomly, but affiliated with the MILESTONE consortium and their network of mental health organisations. The second indication of a potential selection bias relates to the response rate of 45.1%. The dependency on medical records and clinicians for determining eligibility, approaching and informing participants, and for gaining consent is known to make the screening and recruitment process ethically, legally and technically challenging.16 This dependency also complicated registration of the recruitment, resulting in missing information. Unfortunately, we were not able to compare participating young people to those who declined participation, for example, on severity of psychopathology, by conducting a non-response analysis. Medical ethical committees reviewing the MILESTONE protocol did not allow collection of data from young people who had not consented to participating in the study, unless written consent was provided. Since only few young people consented to collecting basic medical information, we concluded our non-response analysis would also be biased and was therefore not considered useful. An analysis of missing data among participants indicated a potential bias in participation of parents, with a higher proportion of missing parental information in young people with higher self-reported problems levels and more severe clinician-rated psychopathology.

Ultimately, the response rate of 45.1% in the MILESTONE cohort is similar to response rates in other cohort studies on adolescents with mental health problems.17–19 Additionally, even though there are indications of selective drop-out, the proportion of young people that withdrew in the 24-month follow-up period was low. A possible selection bias and selective drop-out may affect the representativeness of the MILESTONE cohort, but a representative sample may not be required to generalise the findings from the MILESTONE cohort to other clinical populations of young people in the transition age.20 Selection bias and selective drop-out are unlikely to substantially affect the validity of regression models.21 In analyses investigating the longitudinal association between precursors and outcomes, as will be conducted on MILESTONE cohort data, non-representativeness is less relevant, even if the sample is biased at baseline. Drawing conclusions on the relationships between variables is possible when all potential variables on which a selection could have taken place, such as severity of psychopathology or parental educational level, are controlled for in the analyses.22 Future analyses on MILESTONE cohort data will therefore include these variables and potential confounders as covariates. Additionally, we will apply multiple imputation under the assumption of ‘missing at random’, as we hypothesise missingness is primarily related to constructs that we have assessed, such as self-reported problem levels and clinician-rated severity of psychopathology.

Finally, the reliability of clinical diagnostic classifications has been debated because clinicians usually do not obtain their information through standardised assessment procedures.23 Clinical classifications are therefore reported in broader categories (ie, depressive disorders), rather than subtypes (ie, major depressive disorder, single episode).

It is important to note that although the MILESTONE study was conducted in multiple countries, making country comparisons was not the purpose of the study, as they have been described elsewhere.24 Instead, this cohort study aims to describe what type of care young people receive after reaching the upper age limit of their CAMHS independent of site or country-specific factors. Country comparisons cannot be made validly: the subsamples within countries are not representative of the clinical populations of those countries, which limits opportunities to relate our findings to country-specific characteristics such as transition policy and service organisation. This was complicated further by the lack of formally described transition policies within CAMHS and countries.24

Future plans

Recruitment of CAMHS users within this wide range of services across eight countries resulted in a heterogeneous patient-population, which is very suitable for our aim to describe how sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are associated with the type of care young people receive in the 2 years after reaching the upper age limit of their CAMHS, beyond culture, mental health systems and transition policy. Analysis of longitudinal data from the MILESTONE cohort will be used to assess relationships between the demographic and clinical characteristics of young people reaching the upper age limit of the CAMHS they receive treatment at and the CAMHS clinician’s recommendation to transition from CAMHS to AMHS. Additionally, we will assess the relationship between demographic and clinical characteristics and type of care the young person uses over the next 2 years, such as whether the young person transitions to AMHS. Finally, at 2 years follow-up, the mental health outcomes of young people following different care pathways will be compared.

Collaboration

The MILESTONE consortium invites researchers to contact the corresponding author for requests for statistical code used, instruments used and anonymised data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the young people, parents/carers and clinicians for participating in the MILESTONE study. We would also like to extend our thanks to the teams within the collaborating CAMHS and AMHS. We extend a special thanks to the young project advisors and the members of the MILESTONE Scientific Clinical and Ethical Advisory Board and Jane Warwick. We also thank everyone who was temporarily part of the wider MILESTONE team, as well as all the students who contributed to the data-collection. Finally, we thank all members of the wider MILESTONE consortium for their contribution.

Footnotes

Twitter: @segerritsen, @CFerrari

Collaborators: The wider MILESTONE consortium includes the following collaborators (including the members listed as authors): Laura Adams, Giovanni Allibrio, Marco Armando, Sonja Aslan, Nadia Baccanelli, Monica Balaudo, Fabia Bergamo, Jo Berriman, Chrystèle Bodier Rethore, Frédérique Bonnet-Brilhault, Albert Boon, Karen Braamse, Ulrike Breuninger, Maura Buttiglione, Sarah Buttle, Marco Cammarano, Alastair Canaway, Fortunata Cantini, Cristiano Cappellari, Marta Carenini, Giuseppe Carrà, Isabelle Charvin, Krizia Chianura, Philippa Coleman, Annalisa Colonna, Patrizia Conese, Raffaella Costanzo, Claire Daffern, Marina Danckaerts, Andrea de Giacomo, Peter Dineen, Jean-Pierre Ermans, Alan Farmer, Jörg M Fegert, Alessandro Ferrari, Sabrina Ferrari, Giuliana Galea, Michela Gatta, Elisa Gheza, Giacomo Goglia, MariaRosa Grandetto, James Griffin, Elaine Healy, Keith Holmes, Véronique Humbertclaude, Nicola Ingravallo, Roberta Invernizzi, Renaud Jardri, Helen Keeley, Caoimhe Kelly, Meghan Killilea, James Kirwan, Catherine Klockaerts, Vlatka Kovač, Hélène Lida-Pulik, Ashley Liew, Christel Lippens, Fionnuala Lynch, Francesca Macchi, Lidia Manenti, Francesco Margari, Lucia Margari, Paola Martinelli, James McDonald, Leighton McFadden, Deny Menghini, Maria Migone, Sarah Miller, Emiliano Monzani, Giorgia Morini, Todor Mutafov, Renata Nacinovich, Cristina Negrinotti, Emmanuel Nelis, Francesca Neri, Paulina Nikolova, Marzia Nossa, Michele Noterdaeme, Francesca Operto, Vittoria Panaro, Aesa Parenti, Adriana Pastore, Vinuthna Pemmaraju, Ann Pepermans, Maria Giuseppina Petruzzelli, Anna Presicci, Catherine Prigent, Francesco Rinaldi, Erika Riva, Laura Rivolta, Anne Roekens, Ben Rogers, Pablo Ronzini, Vehbi Sakar, Selena Salvetti, Tanveer Sandhu, Renate Schepker, Paolo Scocco, Marco Siviero, Michael Slowik, Courtney Smyth, Maria Antonietta Spadone, Mario Speranza, Paolo Stagi, Pamela Stagni, Fabrizio Starace, Patrizia Stoppa, Lucia Tansini, Cecilia Toselli, Guido Trabucchi, Maria Tubito, Arno van Dam, Hanne Van Gutschoven, Dirk van West, Fabio Vanni, Chiara Vannicola, Cristiana Varuzza, Pamela Varvara, Patrizia Ventura, Stefano Vicari, Stefania Vicini, Carolin von Bentzel, Philip Wells, Beata Williams, Anna Wilson, Marina Zabarella, Anna Zamboni & Edda Zanetti.

Contributors: SEG prepared the first draft and subsequent versions of this manuscript, under supervision of GCD, AM and FCV and in collaboration with LSvB, MMO and DW. SPS, AM, GDG, PS, JM, FM, DP-O, ST, UMES, TF, CS, MP, DW, FCV and GCD conceived the original study design, obtained funding and/or acted as principal investigators. HT was the study coordinator. PT, SEG, LSvB, GS, FR, LO, ND, VR, MM, RA and NH were research assistants who helped set up the study in their countries, gain local ethical approvals and collected data. AS, JS, AB, MGC, PC, KDC, CF, FML, MCS, GH, DDF, KL, OM, ISO, AS, VM, ET and TAMJvA also contributed to local sites set-up and data-collection. CG, AT, AW and LW were young project advisors. AK and FF contributed on behalf of HealthTracker. GCD is responsible for the overall content as the guarantor. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and gave approval for the publication.

Funding: The MILESTONE project was funded by European Commission’s 7th Framework Programme under grant number 602442.

Competing interests: SPS is part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West Midlands (NIHR CLAHRC WM), now recommissioned as NIHR Applied Research Collaboration West Midlands. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. PS is the co-inventor of the HealthTrackerTM and is the Chief Executive Officer and shareholder in HealthTracker Ltd. FF is a Chief Technical Officer and AK is the Chief Finance Officer employed by HealthTracker Ltd respectively. FCV publishes the Dutch translations of ASEBA, from which he receives remuneration. AM was a speaker and advisor for Neurim, Shire, Infectopharm and Lilly (all not related to transition research).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

for the Milestone consortium:

Laura Adams, Giovanni Allibrio, Marco Armando, Sonja Aslan, Nadia Baccanelli, Monica Balaudo, Fabia Bergamo, Jo Berriman, Chrystèle Bodier Rethore, Frédérique Bonnet-Brilhault, Albert Boon, Karen Braamse, Ulrike Breuninger, Maura Buttiglione, Sarah Buttle, Marco Cammarano, Alastair Canaway, Fortunata Cantini, Cristiano Cappellari, Marta Carenini, Giuseppe Carrà, Isabelle Charvin, Krizia Chianura, Philippa Coleman, Annalisa Colonna, Patrizia Conese, Raffaella Costanzo, Claire Daffern, Marina Danckaerts, Andrea de Giacomo, Peter Dineen, Jean-Pierre Ermans, Alan Farmer, Jörg M Fegert, Alessandro Ferrari, Sabrina Ferrari, Giuliana Galea, Michela Gatta, Elisa Gheza, Giacomo Goglia, MariaRosa Grandetto, James Griffin, Elaine Healy, Keith Holmes, Véronique Humbertclaude, Nicola Ingravallo, Roberta Invernizzi, Renaud Jardri, Helen Keeley, Caoimhe Kelly, Meghan Killilea, James Kirwan, Catherine Klockaerts, Vlatka Kovač, Hélène Lida-Pulik, Ashley Liew, Christel Lippens, Fionnuala Lynch, Francesca Macchi, Lidia Manenti, Francesco Margari, Lucia Margari, Paola Martinelli, James McDonald, Leighton McFadden, Deny Menghini, Maria Migone, Sarah Miller, Emiliano Monzani, Giorgia Morini, Todor Mutafov, Renata Nacinovich, Cristina Negrinotti, Emmanuel Nelis, Francesca Neri, Paulina Nikolova, Marzia Nossa, Michele Noterdaeme, Francesca Operto, Vittoria Panaro, Aesa Parenti, Adriana Pastore, Vinuthna Pemmaraju, Ann Pepermans, Maria Giuseppina Petruzzelli, Anna Presicci, Catherine Prigent, Francesco Rinaldi, Erika Riva, Laura Rivolta, Anne Roekens, Ben Rogers, Pablo Ronzini, Vehbi Sakar, Selena Salvetti, Tanveer Sandhu, Renate Schepker, Paolo Scocco, Marco Siviero, Michael Slowik, Courtney Smyth, Maria Antonietta Spadone, Mario Speranza, Paolo Stagi, Pamela Stagni, Fabrizio Starace, Patrizia Stoppa, Lucia Tansini, Cecilia Toselli, Guido Trabucchi, Maria Tubito, Arno van Dam, Hanne Van Gutschoven, Dirk van West, Fabio Vanni, Chiara Vannicola, Cristiana Varuzza, Pamela Varvara, Patrizia Ventura, Stefano Vicari, Stefania Vicini, Carolin von Bentzel, Philip Wells, Beata Williams, Anna Wilson, Marina Zabarella, Anna Zamboni, and Edda Zanetti

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The participant consent forms restrict data sharing on a public repository. Requests for statistical code and anonymised data may be made to the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved (ISRCTN83240263; NCT03013595) by the UK National Research Ethics Service Committee West Midlands – South Birmingham (15/WM/0052) and ethics boards in participating countries.

References

- 1. McGorry PD. The specialist youth mental health model: strengthening the weakest link in the public mental health system. Med J Aust 2007;187:S53–6. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01338.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Singh SP. Transition of care from child to adult mental health services: the great divide. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2009;22:386–90. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832c9221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stagi P, Galeotti S, Mimmi S, et al. Continuity of care from child and adolescent to adult mental health services: evidence from a regional survey in northern Italy. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;24:1535–41. 10.1007/s00787-015-0735-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perera RH, Rogers SL, Edwards S, et al. Determinants of transition from child and adolescent to adult mental health services: a Western Australian pilot study. Aust Psychol 2017;52:184–90. 10.1111/ap.12192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leavey G, McGrellis S, Forbes T, et al. Improving mental health pathways and care for adolescents in transition to adult services (impact): a retrospective case note review of social and clinical determinants of transition. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2019;54:955–63. 10.1007/s00127-019-01684-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Memarzia J, St Clair MC, Owens M, et al. Adolescents leaving mental health or social care services: predictors of mental health and psychosocial outcomes one year later. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:185. 10.1186/s12913-015-0853-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McNicholas F, Adamson M, McNamara N, et al. Who is in the transition gap? Transition from CAMHS to AMHS in the Republic of Ireland. Ir J Psychol Med 2015;32:61–9. 10.1017/ipm.2015.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Islam Z, Ford T, Kramer T, et al. Mind how you cross the gap! Outcomes for young people who failed to make the transition from child to adult services: the track study. BJPsych Bull 2016;40:142–8. 10.1192/pb.bp.115.050690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pontoni G, Di Pietro E, Neri T. Factors associated with the transition of adolescent inpatients from an intensive residential ward to adult mental health services. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021. 10.1007/s00787-020-01717-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Singh SP, Paul M, Ford T, et al. Process, outcome and experience of transition from child to adult mental healthcare: multiperspective study. Br J Psychiatry 2010;197:305–12. 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blasco-Fontecilla H, Carballo JJ, Garcia-Nieto R, et al. Factors contributing to the utilization of adult mental health services in children and adolescents diagnosed with hyperkinetic disorder. Scientific World J 2012;2012:451205 10.1100/2012/451205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Merrick H, King C, McConachie H, et al. Experience of transfer from child to adult mental health services of young people with autism spectrum disorder. BJPsych Open 2020;6:e58. 10.1192/bjo.2020.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Appleton R, Connell C, Fairclough E, et al. Outcomes of young people who reach the transition boundary of child and adolescent mental health services: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019;28:1431–46. 10.1007/s00787-019-01307-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Singh SP, Tuomainen H, Girolamo Gde, et al. Protocol for a cohort study of adolescent mental health service users with a nested cluster randomised controlled trial to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of managed transition in improving transitions from child to adult mental health services (the MILESTONE study). BMJ Open 2017;7:e016055. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gowers SG, Harrington RC, Whitton A, et al. Brief scale for measuring the outcomes of emotional and behavioural disorders in children. health of the nation outcome scales for children and adolescents (HoNOSCA). Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:413–6. 10.1192/bjp.174.5.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Callard F, Broadbent M, Denis M, et al. Developing a new model for patient recruitment in mental health services: a cohort study using electronic health records. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005654. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huisman M, Oldehinkel AJ, de Winter A, et al. Cohort profile: the Dutch ‘TRacking adolescents’ individual lives’ survey’; TRAILS. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:1227–35. 10.1093/ije/dym273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Purcell R, Jorm AF, Hickie IB, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of young people seeking help at youth mental health services: baseline findings of the transitions study. Early Interv Psychiatry 2015;9:487–97. 10.1111/eip.12133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grootendorst-van Mil NH, Bouter DC, Hoogendijk WJG, et al. The iBerry study: a longitudinal cohort study of adolescents at high risk of psychopathology. Eur J Epidemiol 2021;36:453–64. 10.1007/s10654-021-00740-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rothman KJ, Gallacher JEJ, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1012–4. 10.1093/ije/dys223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wolke D, Waylen A, Samara M, et al. Selective drop-out in longitudinal studies and non-biased prediction of behaviour disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2009;195:249–56. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nohr EA, Liew Z. How to investigate and adjust for selection bias in cohort studies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2018;97:407–16. 10.1111/aogs.13319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McClellan JM, Werry JS. Introduction--research psychiatric diagnostic interviews for children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000;39:19–27. 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Signorini G, Singh SP, Marsanic VB, et al. The interface between child/adolescent and adult mental health services: results from a European 28-country survey. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018;27:501–11. 10.1007/s00787-018-1112-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chisholm D, Knapp MRJ, Knudsen HC, et al. Client socio-demographic and service receipt inventory – European version: development of an instrument for international research. British Journal of Psychiatry 2000;177:s28–33. 10.1192/bjp.177.39.s28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edn. Washington, DC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organization . ICD-10 : international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems : tenth revision. 2nd edn. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA Adult Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guy W, Impressions CG. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pinna F, Deriu L, Diana E, et al. Clinical global Impression-severity score as a reliable measure for routine evaluation of remission in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2015;14:6. 10.1186/s12991-015-0042-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Glazer K, Rootes-Murdy K, Van Wert M, et al. The utility of PHQ-9 and CGI-S in measurement-based care for predicting suicidal ideation and behaviors. J Affect Disord 2020;266:766–71. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hanssen-Bauer K, Gowers S, Aalen OO, et al. Cross-National reliability of clinician-rated outcome measures in child and adolescent mental health services. Adm Policy Ment Health 2007;34:513–8. 10.1007/s10488-007-0135-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, et al. The development and well-being assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2000;41:645–55. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2000.tb02345.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gundersen SV, Goodman R, Clemmensen L, et al. Concordance of child self-reported psychotic experiences with interview- and observer-based psychotic experiences. Early Interv Psychiatry 2019;13:619–26. 10.1111/eip.12547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santosh P, Singh J, Adams L, et al. Validation of the transition readiness and appropriateness measure (TraM) for the managing the link and strengthening transition from child to adult mental healthcare in Europe (milestone) study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e033324. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O'Connell KA, et al. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res 2004;13:299–310. 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Skevington SM, Dehner S, Gillison FB, et al. How appropriate is the WHOQOL-BREF for assessing the quality of life of adolescents? Psychol Health 2014;29:297–317. 10.1080/08870446.2013.845668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rocca P, Galderisi S, Rossi A, et al. Disorganization and real-world functioning in schizophrenia: results from the multicenter study of the Italian network for research on psychoses. Schizophr Res 2018;201:105–12. 10.1016/j.schres.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mucci A, Rucci P, Rocca P, et al. The specific level of functioning scale: construct validity, internal consistency and factor structure in a large Italian sample of people with schizophrenia living in the community. Schizophr Res 2014;159:144–50. 10.1016/j.schres.2014.07.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van Staa A, On Your Own Feet Research Group . Unraveling triadic communication in hospital consultations with adolescents with chronic conditions: the added value of mixed methods research. Patient Educ Couns 2011;82:455–64. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, et al. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res 2006;60:631–7. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oexle N, Ajdacic-Gross V, Müller M, et al. Predicting perceived need for mental health care in a community sample: an application of the self-regulatory model. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50:1593–600. 10.1007/s00127-015-1085-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wolke D, Sapouna M. Big men feeling small: childhood bullying experience, muscle dysmorphia and other mental health problems in bodybuilders. Psychol Sport Exerc 2008;9:595–604. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zwierzynska K, Wolke D, Lereya TS. Peer victimization in childhood and internalizing problems in adolescence: a prospective longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2013;41:309–23. 10.1007/s10802-012-9678-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-053373supp001.pdf (140.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The participant consent forms restrict data sharing on a public repository. Requests for statistical code and anonymised data may be made to the corresponding author.