Abstract

Smoking is the most important factor affecting the oral cavity by components born in the tobacco combustion process and acting directly on the oral mucous membranes, dental arch and indirectly on the teeth support. Recent studies show the tobacco action on the oral cavity, manifestations in the form of gingivitis, bacterial plaque, dental plaque, papillary bleeding at drilling, periodontitis. Purpose of the study. In this study, we have set out to assess the macroscopic modifications of oral cavity on smokers. Materials and Methods. The participants in the study were divided into two groups, the first group of smokers with a smoking period over 5 years and the control group of nonsmokers. The patients in the two groups underwent a physical examination and an objective clinical examination, the resulting data being compared with the control group. Results. For the bacterial plaque indicatorin the smoker group there was obtained a mean value of 35.68±12.45, compared to a mean value of 16.32±6.61 for the nonsmoker group, the dental plaque indicatorfor the smoker group had a mean value of 2.24±1.02, higher than the one in the nonsmoker group, namely 0.94±0.68, and for the drilling bleeding indicator we obtained a mean value of 19.54±7.89 in the nonsmoker group, which is lower than that in the smoker group, namely 42.86±14.93. Conclusions. Smoking is a cause that maintains and aggravates the periodontal disease, including the risk of periodontitis, allowing the aggravation of gingivitis, considered a reversible surface inflammation of the gum mucosa which, by accumulation of dental plaque, the dental plaque accompanied by incorrect oral hygiene, favors the progression to periodontitis.

Keywords: Periodontitis, bacterial plaque, dental calculus deposit, local bleeding, smokers

Introduction

The oral cavity is the first segment of the digestive tube, being the entrance gate of food and fluids into the body [1].

The mucosa of the oral cavity is a non-keratinized, paved surface epithelium, lining the soft parts and hard surfaces of the mouth [2].

The localization at the entrance gate of the digestive and respiratory tract, as well as the presence of teeth, make the mouth mucosa subject to different natural or artificial damaging agents [2].

The mouth mucosa is the general term used to describe the soft tissues mucosa of the oral cavity represented by oral and gingival mucosa. As a layered epithelium, most layers help protect against bacterial infections and act to regulate water temperature and water balance [3].

Oral mucosa can often be affected by a variety of conditions, such as periodontitis, gingivitis, melanosis, foot-and-mouth disease, herpes or candidose; the main characteristic is to be more permeable than the skin and the surface epithelial layer of the mucosa represents a significant barrier to permeability [4].

The purpose of the study is to show the effect of tobacco on oral hygiene indicators lead to macrosopic changes in the elements of the oral cavity. The importance of the study is to make adult people aware of the effects of tobacco on the oral cavity. The objective is to minimize changes in oral health in smokers in comparison to nonsmokers.

Matherials and Methods

This study was performed between 2016-2019 in the dental practice S.C. SMILE GABI DENT S.R.L., in Galati and Braila; 100 patients gave their written consent to participate in the study, being divided into two equal groups, made up of patients of both genders, the criterion of differebtiation being tobacco intake.

The control group consisted of nonsmokers, comprising 24 men and 26 women, aged between 19 and 82 years old.

The smoker group was made up of 33 men and 17 women, aged between 23 and 70 years old. The group of smokers was divided according to the duration of smoking period, grouped on time periods of 5-15 years (4 persons), 16-25 years (9 persons), 26-35 years (15 persons), 36-55 years (22 persons), over 55 years (0 persons).

The sam e group of smokers was divided according to the number of cigarettes consumed daily, resulting in 14 patients smoking between 10 and 20 cigarettes per day and 36 patients smoking more than 20 cigarettes per day.

The patients underwent an objective clinical examination and the data collected were used to calculate the the bacterial plaque, dental tartrate and bleeding at drilling indicators.

Bacterial plaque indicator consists of 4 variables (0 plaque free; 1 gingival plaque in upper third part of the tooth; 2 gingival plaque on the middle thrid of the tooth; 3 plaque in the incisional or occlusional thrid of the tooth crown); the dental plaque indicator presents 4 variables (0 plaque free; 1 gingival plaque in upper third part of the tooth; 2 gingival plaque on the middle thrid of the tooth; 3 plaque in the incisional or occlusional thrid of the tooth crown); the papillary bleeding indicator (MUHLEMANN) contains four variables (0 bleeding free; 1 single point blood; 2 multiple point bleeding or on a reduced area; 3 bleeding that fills the entire interdental space; 4 bleeding beyond the free gingival edge.

Results

Figure 1 shows the normal clinical aspect of the oral mucosa which is firm and durable at pressure, with an adherence to the underlying bone plane, fixed to it by the fibers at the chorion level. The buccal surface of the normal gum mucosa has an ‘orange zest’ appearance, with slight depression, pink with whitish tint on its surface, due to the difference in the thickness of the epithelial tissue, but also the degree of keratinization of the superficial skin of the epithelium.

Figure 1.

Normal gingival mucosa aspect Upper and lower dental archway

Our study of the health of the oral cavity in smokers showed that all of these people had clinical changes in chronic gingivitis or periodontitis that were mainly due to the presence of plaque usually associated with dental plaque and papillary bleeding. These macroscopic changes have also occurred due to a poor brushing process that did not completely remove the dental film and the bacterial plaque and the recorded oral hygiene indicators showed higher values for the smoker group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Lower dental archway aspect with soft bacterial deposit and hard dental plaque deposits on a smoking patient

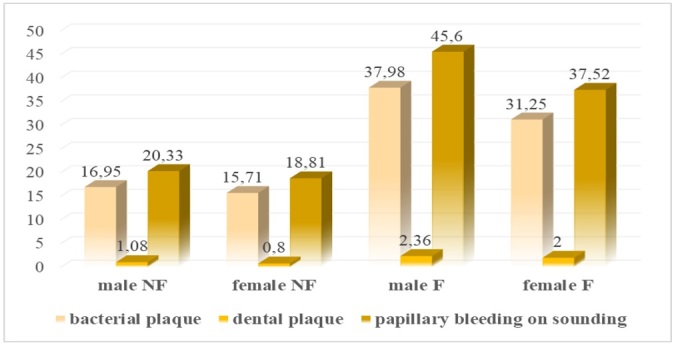

Table 1 shows the mean values together with the standard deviation (SD) for the factors gender two variables (male, female) and age with six variables (18-25 years, 26-35 years, 36-45 years, 46-55 years, 56-65 years, >65 years) for the descriptive indicators for bacterial plaque, dental plaque and papillary bleeding at drilling. The test for single factorial variable analysis showed a bacterial plaque a value of F(1.98)=7.137 and a value p=0.01, for dental plaque a value of F(1.98)=6.563 and p=0.01, for papillary bleeding at drilling value F(1.98)=7.158, p=0.01.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation (SD) for descriptive indicators, bacterial plaque,dental plaque, papillary bleeding when soundings in relation to variable gender factors, age for the two groups (control, working)

|

|

Bacterial plaque |

Dental plaque |

papillary bleeding at drilling |

|

|

Mean±SD |

Mean±SD |

Mean±SD |

||

|

Sex |

Male non-smoken |

16.98±5 |

1.08±0.58 |

20.33±6.05 |

|

Female nonsmoker |

15.71±7.86 |

0.8±0.74 |

18.81±9.34 |

|

|

Male smoker |

37.98±13.95 |

2.36±0.99 |

45.6±16.72 |

|

|

Female smoker |

31.25±7.34 |

2±1.06 |

37.52±8.81 |

|

|

Age |

18-25 years nonsmoker |

7.2±3.81 |

0.33±0.57 |

8.66±4.61 |

|

26-35 years nonsmoker |

12.02±6.87 |

0.86±0.69 |

14.16±8.15 |

|

|

36-45 years nonsmoker |

16.42±3.65 |

1±0.01 |

19.75±4.34 |

|

|

46-55 years nonsmoker |

14.41±6.04 |

0.64±0.7 |

17.35±7.26 |

|

|

56-65 years nonsmoker |

21±3.68 |

1.12±0.64 |

25.25±4.43 |

|

|

> 65 years nonsmoker |

21.03±4.99 |

1.45±0.52 |

25.09±5.8 |

|

|

18-25 years smoker |

25±0.01 |

2.00±0.01 |

30±0.01 |

|

|

26-35 years smoker |

31.26±4.96 |

1.66±0.51 |

37.5±5.96 |

|

|

36-45 years smoker |

29.24±6.16 |

1.71±0.49 |

35.14±7.42 |

|

|

46-55 years smoker |

36.78±10.83 |

2.5±1.16 |

44.16±13 |

|

|

56-65 years smoker |

36.56±14.16 |

2.23±1.09 |

43.93±16.96 |

|

|

> 65 years smoker |

43.45±17.18 |

2.85±1.06 |

52.14±20.62 |

|

The values obtained by the working group were on average 2.2% higher for the indicators of hygiene bacterial plaque, dental plaque and papillary bleeding at drilling compared to the control group for all given descriptive indicators, data supporting the theory that the tobacco factor influences the health of the oral cavity.

The sex factor represented by the two male/female variables, for the variable the age had a mean value of 53.4 with a standard deviation of 14.76 for women and for men a mean value of 50.5 with a 13.95 standard deviation, p=0.32.

The values of the descriptive indicators for bacterial plaque, dental plaque and papillary bleeding at drilling shown in Figure 3 are different according to sex for each group with a mean value of 1.16% higher for the male nonsmokers than the resulting values for the female nonsmokers, the same higher mean values being observed for the male smokers, 1.2% higher than for the female smokers.

Figure 3.

Overall plaque descriptive indicator data for the nonsmoker and smoker groups by gender

The differences in values obtained for oral hygiene indicators in the smoker and nonsmoker groups are 2.2% higher for the male smokers and 2% higher for the female smokers, compared to non-smoking control group values.

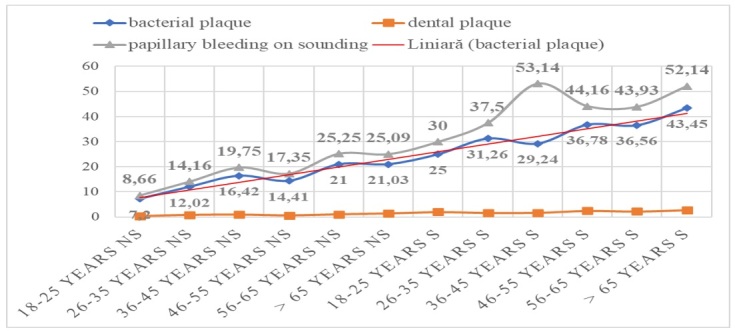

The mean values for the two nonsmoker and smoker groups are shown in Figure 4, in the bacterial plaque oral hygiene indicator, dental plaque, papillary bleeding at drilling, a linear increase being observed for both, the control group and the working group with an increase between 2.66 and 3.4% for the bacterial plaque; for dental plaque the increase is in the range of 1.96-6%, while for papillary bleeding at drilling the increase is in the range of 2.07-3.46%, with a higher value recorded in the smoker group.

Figure 4.

Plaque descriptive indicators for the nonsmoker (NS) and smoker (S) groups according to age groups

For the two groups the data were extracted from the database with the single factorial variant analysis one Way ANOVA to test the significance between the measured mean values-bacterial plaque, plaque and bleeding data associated with the smoker and nonsmoker groups.

In Table 2 below, for the tobacco factor, the ANOVA test shows for variable bacterial plaque test result F(1.98)=94.30, with a p=0.001, for the dental plaque variable test result F(1.98)=55.99 with a p=0.001, for the papillary bleeding at drilling a variable test result F(1.98)=95.26, with a p=0.001. The influence of the tobacco factor is observed for the three oral hygiene indicators, and the theory is also supported in Table 5 with the data containing the mean value and standard deviation.

Table 2.

Single factorial analysis for bacterial plaque, dental plaque, papillary bleeding ast drilling relative to tobacco factor (df=degrees of fredoom, F=Fischer statistics, Sig.=p value)

|

ANOVA | ||||||

|

|

|

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

|

Bacterial plaque |

Between Groups |

9378.179 |

1 |

9378.179 |

94.340 |

.000 |

|

Within Groups |

9742.027 |

98 |

99.408 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

19120.207 |

99 |

|

|

|

|

|

Dental plaque |

Between Groups |

42.250 |

1 |

42.250 |

55.998 |

.000 |

|

Within Groups |

73.940 |

98 |

.754 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

116.190 |

99 |

|

|

|

|

|

Papillary bleeding at drilling |

Between Groups |

13588.565 |

1 |

13588.565 |

95.268 |

.000 |

|

Within Groups |

13978.226 |

98 |

142.635 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

27566.791 |

99 |

|

|

|

|

Table 5.

Single factorial analysis for bacterial plaque, dental plaque, papillary bleeding at drilling related to the smoking period factor (expressed in years) (df=degrees of fredoom, F=Fischer statistics, Sig.=p value)

|

ANOVA | ||||||

|

|

|

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

|

Bacterial plaque |

Between Groups |

10633.33 |

4 |

2658.383 |

29.758 |

.000 |

|

Within Groups |

8486.674 |

95 |

89.333 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

19120.207 |

99 |

|

|

|

|

|

Dental plaque |

Between Groups |

51.442 |

4 |

12.860 |

18.869 |

.000 |

|

Within Groups |

64.748 |

95 |

.682 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

116.190 |

99 |

|

|

|

|

|

Papillary bleeding at drilling |

Between Groups |

15392.494 |

4 |

3848.124 |

30.028 |

.000 |

|

Within Groups |

12174.296 |

95 |

128.150 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

27566.791 |

99 |

|

|

|

|

In Table 3 above, for the cigarette variable, the single factorial analysis test recorded data for bacterial plaque test result F(2.97)=52.06, with a p=0.001, for the dental plaque variable test result F(2.97)=33.69, with a p=0.001, for papillary bleeding at drilling variable test result F(2.97)=52.57, with a p=0.001.

Table 3.

Single factorial analysis for bacterial plaque, dental plaque, papillary bleeding at drilling relative to the tobacco factor (df=degrees of fredoom, F=F statistics, Sig.=p value).

|

ANOVA | ||||||

|

|

|

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

|

Bacterial plaque

|

Between Groups |

9898,960 |

2 |

4949.480 |

52.064 |

.000 |

|

Within Groups |

9221.247 |

97 |

95.064 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

19120.207 |

99 |

|

|

|

|

|

Dental plaque

|

Between Groups |

47.624 |

2 |

23.812 |

33.687 |

.000 |

|

Within Groups |

68.566 |

97 |

.707 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

116.190 |

99 |

|

|

|

|

|

Papillary bleeding at drilling |

Between Groups |

14339.278 |

2 |

7169.639 |

52.576 |

.000 |

|

Within Groups |

13227.513 |

97 |

136.366 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

27566.791 |

99 |

|

|

|

|

The influence of the tobacco factor is noted for the three oral hygiene indicators, which is also supported in Table 5 with the data for the mean value and standard deviation.

In Table 4 below, for the smoking time factor (expressed in years) the ANOVA test shows for the bacterial plaque variable.

Table 4.

Test for homogeneity of variances for bacterial plaque index, dental plaque, papillary blood on spot cigarette factor

|

|

Levene test statistic |

df1 |

Df2 |

Sig. |

|

Bacterial plaque Dental plaque Papillary bleeding when sounding |

8,809 11,966 8,800 |

2 2 2 |

97 97 97 |

,000 ,000 ,000 |

Test result F(4.95)=29.78, with a p=0.001, for the dental plaque variable test result F(4.95)=18.87, with a p=0.001, for papillary bleeding at drlling variable test result F(4.95)=30.03, with a p=0.001.

Oral hygiene indicators (bacterial plaque, dental plaque, papillary bleeding at drilling) are influenced by the tobacco factor and the data in Table 5 containing the mean values and standard deviation supporting the theory.

The mean values and standard deviation for each group are calculated in Table 6 above, depending on the determining factor, in our case tobacco, the number of cigarettes smoked per day, or smoking time (expressed in years), for the bacterial plaque, dental plaque and papillary bleeding at drilling variables.

Table 6.

Mean, standard deviation (SD) for descriptive indicators of bacterial plaque, dental tartrate, papillary bleeding at drilling for the variables tobacco, cigarettes, smoking period (expressed in years) for both groups

|

|

Bacterial plaque |

Dental plaque |

Papillary bleending when sounding |

|

|

Mean±SD |

Mean±SD |

Mean±SD |

||

|

Tobacco |

Nonsmoker |

16.32±6.61 |

0.94±0.68 |

19.54±7.9 |

|

smoker |

35.69±12.43 |

2.24±1.02 |

42.86±14.93 |

|

|

Cigarettes |

Nonsmoker |

16.32±6.61 |

0.94±0.68 |

19.54±7.9 |

|

between 10-20 cigarettes |

30.52±5.04 |

1.71±0.47 |

36.64±6.06 |

|

|

more 20 cigarettes |

37.7±13.9 |

2.44±1.11 |

45.27±16.64 |

|

|

Period of smoking |

Nonsmoker |

16.32±6.61 |

0.94±0.68 |

19.54±7.9 |

|

5-15 years of smoking |

29.8±3.56 |

1.21±0.01 |

35.75±4.27 |

|

|

16-25 years of smoking |

30.8±5.22 |

1.55±0.52 |

37±6.26 |

|

|

26-35 years of smoking |

31.96±10.3 |

2.07±0.88 |

38.4±12.34 |

|

|

35-55 years of smoking |

41.3±14.8 |

2.68±1.17 |

49.58±17.74 |

|

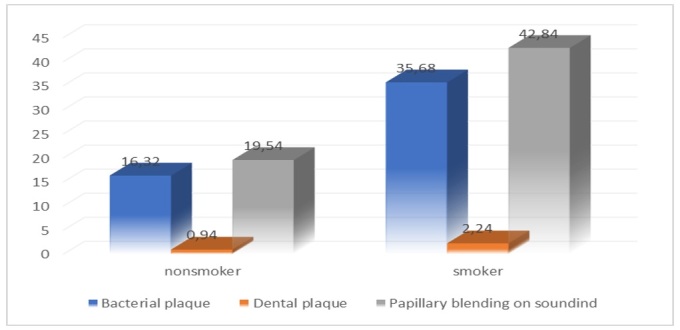

In Figure 5, we observe for each descriptive indicator, namely bacterial plaque, dental plaque, papillary bleeding at drilling, for the mean values calculated using the ANOVA test, the recorded data in the smoker group are 2.2% higher than the data recorded in the control group, this showing the influence of smoking in the damaging of oral health.

Figure 5.

Descriptive indicators for the bacterial plaque, dental calculus, papillary bleeding at drilling for the tobacco consumers group

The Levene Statistical test calculated for the descriptive indicator of the bacterial plaque a value of p=0.06, for the descriptive dental plaque indicator a value of p=0.14, and the descriptive papillary bleeding at drilling indicator with a value of p=0.06.

In all three cases the p-value obtained was less than p=0.5.

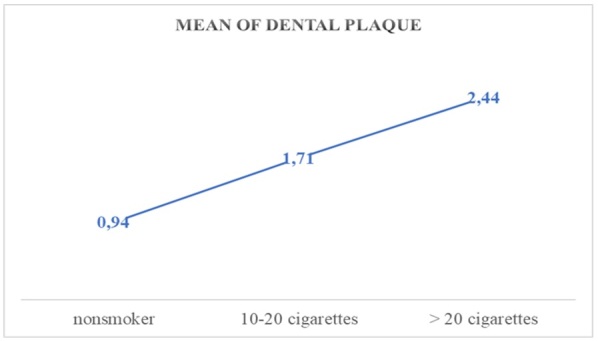

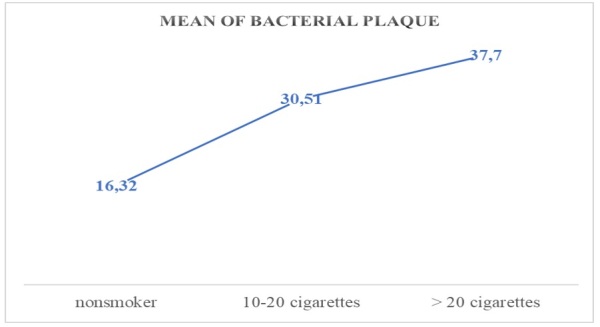

The formation and duration of dental plaque/ bacterial plaque in the oral cavity is influenced by the number of cigarettes consumed, which alter the biotype of the oral cavity by compounds inhaled at tobacco combustion (nicotine, tar, isopotnoids), as shown in Figures 6,7 for the descriptive indicator of dental/bacterial plaque, where the increase in its presence is a mean of 1.81% for those who smoke between 10-20 cigarettes per day compared to the control group, and for those who smoke more than 20 cigarettes a day a mean increase of 1.42% compared to those who smoke between 10-20 cigarettes and 3.38% compared to the control group.

Figure 6.

Mean values of the dental plaque related to the cigarette factor

Figure 7.

Mean values of the bacterial plaque related to the cigarette factor

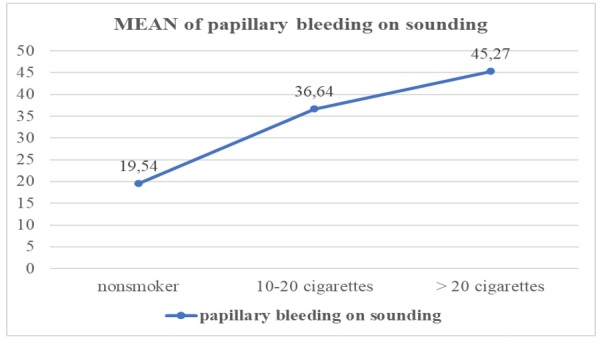

The number of cigarettes influences the maintenance and increase of papillary bleeding at drilling in the oral cavity by the change made to the oral cavity biotype by the compounds inhaled at tobacco combustion, as shown in Figure 8 for the papillary bleeding at drilling descriptive indicator, and the increase is a mean of 1.8% for those who smoke between 10-20 cigarettes per day compared to the control group, and for those who smoke more than 20 cigarettes a day a mean increase of 1.23% compared to those who smoke between 10-20 cigarettes and 2.31% compared to the controlgroup.

Figure 8.

Mean values of the dental plaque related to the papillary bleedings on sounding

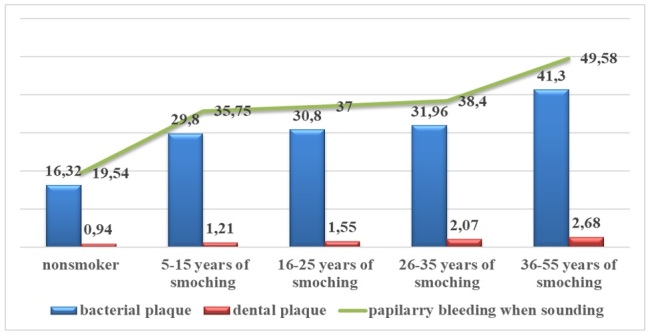

In Figure 9 below, the smoking time variable (expressed in years) in is plotted correlation with descriptive indicators bacterial plaque, dental plaque, papillary bleeding at drilling, mean values which are shown on the graph with a mean increase of 1.28% for the dental plaque indicator and a mean of 1.29% for the bacterial plaque and papillary bleeding at drilling on the percentage of the sample in relation to the control group.

Figure 9.

Descriptive indicators of the bacterial plaque, dental plaque, papillary bleeding at drilling for the variable Smoking period (expressed in years).

Discussion

The dental plaque differs in cigarette smokers and nonsmokers, with a predilection of bacterial plaque accumulation in smokers on the lingual part of anterior teeth, compared to nonsmokers who showed bacterial plaque on the upper buccal part [5].

Lack of hygiene or a superficial oro-dental hygiene corroded by an incorrect technique dental brushing plays an important role in the health of the oral cavity, solid dental plaque deposits with light to brown colorations present in the teeth package or soft yellowish-white deposits due to bacterial plaque accumulation are frequently encountered [6].

Presence of a complex ecosystem of bacteria in the bacterial plaque various stages of development, cells of the exfoliated epithelial test, food debris and salival proteins in the gingival contact area give rise to gingival inflammation, and at dental cervical level a process of enhanced demineralization with a dark yellow-brown erode appearance is developed [7].

Tobacco compounds can also affect the progression of the dental plate through damage direct of normal cells of parodonals. For example, nicotine can be stored and released from parodontic fibroblasts [8].

These fibroblasts exposed to nicotine have a modified morphology and have a weak capacity to attach to radiculars, multiply and produce collagen [9].

Bastiaan (1978) said the plaque levels seemed to be higher in smokers than for nonsmokers, but the differences were not statistically significant [6].

The superficial gum inflammation is triggered by the biotype of micro-organisms found in the acquired film and the dental plaque, which will maintain the inflammatory process with the evolution to the periodontitis [10,11].

Host factors (genetic factors, local risk factors, chronic diseases) which play a determining role in conjunction with the disruptive factor of tobacco should not be excluded from the development of the inflammatory process, thus hampering the curing process [12,13,14].

Several factors can indirectly act upon the formation of the bacterial plaque and one of them is considered to be smoking as a bacterial plaque formation faster in smokers than in nonsmokers [10].

In regard to the degree of gingual inflammation, the clinical appearance was visibly improved after the plate was removed, but tobacco consumption led to a longer time to improve the gum inflammation [15].

The anatomical and physiological characteristics of the teeth crowns are susceptible to a bigger load bacterial count, combined with the number of cigarettes consumed daily [16,17].

The bacterial plaque was frequently observed as initially forming microcolonies that conflugate on the surface of the tooth and the gum mucosa stimulating gum inflammation [18,19].

The major observation in smokers was the higher prevalence and severity for overgum calculus in comparison to nonsmokers [14].

Tobacco consumption is a risk factor for chronic periodontitis and smoking has a blood response gum-based inflammation effect on the bacterial plaque [20].

The extensive analysis of previously published articles and data on parodontal disease has improved the ability to detect new correlations and perspectives on relationships between organisms, cytokines and metabolites in the assessment of the evolution of parodontis [21].

The most important risk factors known today are diabetes mellitus and smoking [22].

In smokers who smoke more than 20 cigarettes per day, the amount of nicotine and metabolites were higher, while increasing the severity of parodonal disease, although this severity of periodontal damaging is observed from more than 10 cigarettes per day smoked [23].

The amount of crevicular liquid in the ditch was in higher quantities in smokers with chronic periodontitis where the presence of bacterial plaque and dental plaque is more significant [24].

Any alternative or classical smoking source which generates nicotine, nitrosamines tobacco specific, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds act negatively on mucous membranes and oral cavity [25].

Smoking tobacco produced in a wide variety of sizes and models contains mixtures which may influence nicotine and their pH, first stating that the smoking does not inhale in the lung, Due to the possibility of nicotine absorption by the initial oral mucosa, it has an alkaline pH which then decreases by reducing the gum absorption with changes in the mucosa [26,27].

The greatest risk of periodontitis is found in people who smoke more than 10 cigarettes per day and having a smoking age in excess of eight years [28,29,30].

Conclusion

Smoking, irrespective of the type of tobacco consumed by the basic components represented nicotine and tar yields associated with a long period of consumption, may induce irreversible changes in the teeth.

From the study, we can conclude on smoking as the time expressed in years of smoking, the number of cigarettes consumed daily has a constant influence on the increase in oral hygiene indicators represented by counting the values for the bacterial plaque, dental tartrate and papillary bleeding at drilling.

The carelessness of a rigorous hygiene, coupled with tobacco consumption, constantly and regularly damages the bacterial balance of the oral cavity, which by bacterial overload or weakening of the immune system becomes a challenge for local or systemic health.

Conflict of interests

None to declare.

References

- 1.Eickolz P. Physiologie der Mundhöhle. Dermatologisch relevante Aspekte [Physiology of the oral cavity. Dermatologic aspects] Hautarzt. 2012;63(9):678–686. doi: 10.1007/s00105-012-2350-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chi AC, Neville BW, Krayer JW, Gonsalves WC. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(11):1381–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephens RG, Kogon SL, Jarvis AM. A study of the reasons for tooth extraction in a Canadian population sample. . J Can Dent Assoc. 1991;5757(6)(8):501–504. 611–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang QZ, Nguyen AL, Yu WH, Le AD. Human oral mucosa and gingiva: a unique reservoir for mesenchymal stem cells. J Dent Res. 2012;91(11):1011–1018. doi: 10.1177/0022034512461016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raja IM, Nadeem M, Zareef U. Pattern of dental plaque distribution and cigarette smoking a cross sectional study. Medical Forum Monthly. 2018;29(2):28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastiaan RJ, Waite IM. Effects of tobacco smoking on plaque development and gingivitis. J Periodontol. 1978;49(9):480–482. doi: 10.1902/jop.1978.49.9.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sreenivasan PK, DeVizio W, Prasad KV, Patil S, Chhabra KG, Rajesh G, Javali SB, Kulkarni RD. Regional differences within the dentition for plaque, gingivitis, and anaerobic bacteria. J Clin Dent. 2010;21(1):13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mubeen K, Chandrashekhar H, Kavitha M, Nagarathna S. Effect of tobacco on oral-health an overview. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences. 2013;2(20):3523–3534. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanagisawa T, Ueno M, Shinada K, Ohara S, Wright FA, Kawaguchi Y. Relationship of smoking and smoking cessation with oral health status in Japanese men. J Periodontal Res. 2010;45(2):277–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2009.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jakubovics NS, Kolenbrander PE. The road to ruin: the formation of disease-associated oral biofilms. Oral Dis. 2010;16(8):729–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsh PD, Devine DA. How is the development of dental biofilms influenced by the host. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(Suppl 11):28–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnea TV, Sava A, Gentimir C, Goriuc A, Boişteanu O, Chelaru L, Iancu RI, Avram CA, Acatrinei DD, Bogza EG, Răducanu OC, Cioloca DP, Vasincu D, Costuleanu M. Genetic polymorphisms of TNFA and IL-1A and generalized aggressive periodontitis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56(2):459–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stratul ŞI, Roman A, Şurlin P, Petruţiu ŞA, Buiga P, Mihu CM. Clinical and histological characterization of an aggressive periodontitis case associated with unusual root canal curvatures. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56(2):589–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akram Z, Abduljabbar T, Abu Hassan MI, Javed F, Vohra F. Cytokine profile in chronic periodontitis patients with and without obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Markers. 2016;2016:4801418–4801418. doi: 10.1155/2016/4801418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabita PV, Bissada NF, Maybury JE. Effectiveness of supragingival plaque control on the development of subgingival plaque and gingival inflammation in patients with moderate pocket depth. J Periodontol. 1981;52(2):88–93. doi: 10.1902/jop.1981.52.2.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sreenivasan PK, Prasad KVV, Javali SB. Oral health practices and prevalence of dental plaque and gingivitis among Indian adults. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2016;28;2(1):6–17. doi: 10.1002/cre2.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sreenivasan PK, Prasad KVV. Distribution of dental plaque and gingivitis within the dental arches. J Int Med Res. 2017;45(5):1585–1596. doi: 10.1177/0300060517705476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizuno H, Takayama E, Satoh A, Into T, Adachi M, Ekuni D, Yashiro K, Mizuno-Kamiya M, Nagayama M, Saku S, Tomofuji T, Doi Y, Murakami Y, Kondoh N, Morita M. Horseradish peroxidase interacts with the cell wall peptidoglycans on oral bacteria. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20(3):2822–2827. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbons RJ, van Houte J. On the formation of dental plaques. J Periodontol. 1973;44(6):347–360. doi: 10.1902/jop.1973.44.6.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergström J. Tobacco smoking and supragingival dental calculus. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26(8):541–547. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buduneli N, Scott DA. Tobacco-induced suppression of the vascular response to dental plaque. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2018;33(4):271–282. doi: 10.1111/omi.12228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sisk-Hackworth L, Ortiz-Velez A, Reed MB, Kelley ST. Compositional Data Analysis of Periodontal Disease Microbial Communities. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:617949–617949. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.617949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Genco RJ. Current view of risk factors for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 1996;67(10 Suppl):1041–1049. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meenawat A, Govila V, Goel S, Verma S, Punn K, Srivastava V, Dolas RS. Evaluation of the effect of nicotine and metabolites on the periodontal status and the mRNA expression of interleukin-1β in smokers with chronic periodontitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015;19(4):381–387. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.157879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodrigues WF, Miguel CB, Mendes NS, Freire Oliveira CJ, Ueira-Vieira C. Association between pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-33 and periodontal disease in the elderly: A retrospective study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2017;21(1):4–9. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_178_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atuegwu NC, Perez MF, Oncken C, Thacker S, Mead EL, Mortensen EM. Association between Regular Electronic Nicotine Product Use and Self-reported Periodontal Disease Status: Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(7):1263–1263. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneller LM, Quiñones Tavárez Z, Goniewicz ML, Xie Z, McIntosh S, Rahman I, O'Connor RJ, Ossip DJ, Li D. Cross-Sectional Association Between Exclusive and Concurrent Use of Cigarettes, ENDS, and Cigars, the Three Most Popular Tobacco Products, and Wheezing Symptoms Among U.S. Adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(Suppl 1):S76–S84. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawler TS, Stanfill SB, deCastro BR, Lisko JG, Duncan BW, Richter P, Watson CH. Surveillance of Nicotine and pH in Cigarette and Cigar Filler. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(Suppl 1):101–116. doi: 10.18001/TRS.3.2(Suppl1).11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Genco RJ, CDC Periodontal Disease Surveillance workgroup: James Beck (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, USA), Gordon Douglass (Past President, American Academy of Periodontology), Roy Page (University of Washin Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012;91(10):914–920. doi: 10.1177/0022034512457373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eke PI, Borgnakke WS, Genco RJ. Recent epidemiologic trends in periodontitis in the USA. Periodontol 2000. 2020;82(1):257–267. doi: 10.1111/prd.12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]