Dear Editor:

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased anxiety and depressive symptoms in the general population.1 Health bodies have recommended several behaviors to cope with them. Still, prospective longitudinal evidence on the efficacy of these behaviors to reduce such symptoms is scarce.

We have followed a population-representative cohort of 1049 Spanish adults for one year to shed light on the subject. We asked participants to rate the frequency of ten coping behaviors and the intensity of anxiety (GAD7)2 and depressive (PHQ9)3 symptoms every two weeks (we detail the procedures elsewhere).4 On December 3, 2021, 946 participants (90.2%) had finished (or were about to finish) the study and 103 (9.8%) had opted out or failed to complete ≥70% questionnaires with <10% missing answers. We used multiple imputation for missing GAD7/PHQ9 items and fitted weighted mixed-effects autoregressive moving average (ARMA2,1) models to assess whether coping behaviors predicted subsequent anxiety and depressive symptoms. These models considered the effect of previous symptoms on posterior symptoms and weighted the observations to ensure the representativity of the sample in population terms.

We will publish the complete analysis results after all participants finish the study. Still, we find it relevant to disseminate without delay the potential utility of one of the coping behaviors assessed -following a healthy/balanced diet- in preventing anxiety and depressive symptoms.

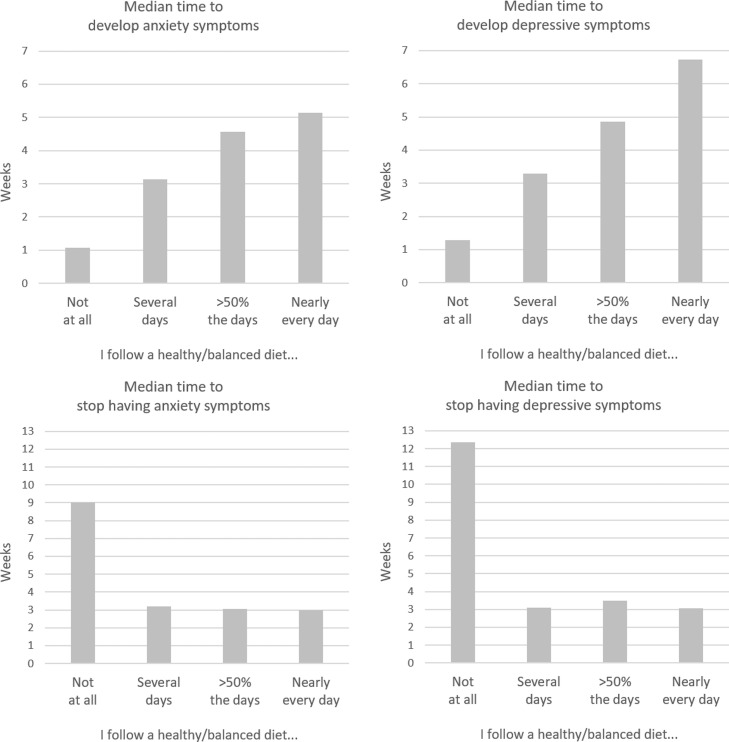

Specifically, we found that following a healthy/balanced diet predicted less future anxiety (b = −0.85, p < 10−13) and depressive (b = −1.27, p < 10−28) symptoms substantially more strongly than other behaviors such as talking with relatives/friends or taking the opportunity to pursue hobbies (b = −0.25 to −0.02, p = 0.045 to 0.86) (b is the difference in GAD-7/PHQ-9 scores when following vs. not following a healthy/balanced diet, considering past GAD-7/PHQ-9 scores). To investigate the potential preventive or therapeutic effects of a healthy/balanced diet, we then fitted ad-hoc weighted mixed-effects Cox regressions to the same data. Following a healthy/balanced diet delayed the emergence of anxiety or depressive symptoms (GAD7/PHQ9 ≥ 5)2, 3 (anxiety: hazard ratio (HR) = 0.41, p < 10−12; depressive: HR = 0.46, p < 10−7). These preventive effects showed a robust dose-response relationship: the more days per week a participant followed a healthy/balanced diet, the less likely he/she was to develop anxiety or depressive symptoms (Fig. 1 ). Moreover, both types of symptoms remitted earlier when following a healthy/balanced diet (anxiety: HR = 1.74, p < 10−4; depressive: HR = 1.65, p < 10−4) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Median time to develop or stop having anxiety and depressive symptoms depending on the reported frequency of following a healthy/balanced diet.

As other coping behaviors assessed (physical exercise, following a routine, and drinking water to hydrate) highly correlated with following a healthy/balanced diet (weighted r = 0.43–0.50), we repeated the ARMA covarying for these behaviors. Overall, the results remained unchanged (anxiety: b = −0.76, p < 10−9; depressive: b = −1.03, p < 10−15). We also obtained similar results when we excluded participants with hazardous alcohol consumption (AUDIT ≥ 8)5 (anxiety: b = −1.03, p < 10−11; depressive: b = −1.53, p < 10−23).

The mechanisms through which a healthy/balanced diet might protect against anxiety and depressive symptoms may vary, ranging from improving the brain's nutritional intake to stabilizing the gut microbiome. Regardless, our study is longitudinal but not interventional. Thus, we cannot rule out that not following a healthy diet is only an early sign of some mechanism that later leads to increased anxiety and depressive symptoms. We also acknowledge that following a healthy/balanced diet was assessed only by self-report. However, previous studies have shown that most individuals in the general population have good practical knowledge about what a healthy/balanced diet means.6

We have known for decades that a healthy diet effectively prevents several illnesses. We provide promising evidence that it might also prevent anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Funding

AXA Research Fund supports this research via a grant from the call “Mitigating risk in the wake of the Covid-19 Pandemic” to J.R. Additionally, the Instituto de Salud Carlos III – Subdirección General de Evaluación y Fomento de la Investigación and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER, “Investing in your future”) supports J.R. (Miguel Servet Research Contract CPII19/00009) and L.F. (PFIS Predoctoral Contract FI20/00047). The funders have no role in the study's design and conduct, collection, management, analysis, interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

None reported.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the individuals who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Schafer K.M., Lieberman A., Sever A.C., Joiner T. Prevalence rates of anxiety, depressive, and eating pathology symptoms between the pre- and peri-COVID-19 eras: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;298(Pt A):364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B., Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fortea L., Solanes A., Pomarol-Clotet E., Garcia-Leon M.A., Fortea A., Torrent C., et al. Study protocol – coping with the pandemics: what works best to reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:642763. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.642763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saunders J.B., Aasland O.G., Babor T.F., de la Fuente J.R., Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption – II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motteli S., Barbey J., Keller C., Bucher T., Siegrist M. Measuring practical knowledge about balanced meals: development and validation of the brief PKB-7 scale. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:505–510. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]