Abstract

Objective:

We evaluated whether interhospital variation in mortality rates for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) was driven by complications and failure to rescue.

Methods:

An observational study was conducted among 83,747 patients undergoing isolated CABG between July 2011 to June 2017 across 90 hospitals. Failure to rescue (FTR) was defined as operative mortality among patients developing complications. Complications included the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) five major (stroke, surgical re-exploration, deep sternal wound infection, renal failure, prolonged intubation) and a broader set of 19 overall complications. After creating terciles of hospital performance (based on observed:expected “O:E” mortality), each tercile was compared based on crude rates of: (i) major and overall complications, (ii) operative mortality and (iii) FTR (among major and overall complications). The correlation between hospital observed and expected (to address confounding) FTR rates was assessed.

Results:

Median STS predicted mortality risk was similar across hospital O:E mortality terciles (p=0.831). Mortality rates significantly increased across terciles (low: 1.4%, high: 2.8%). While small in magnitude, rates of major (low: 11.1%, high: 12.2%) and overall complications (low: 36.6%, 35.3%) significantly differed across terciles. Nonetheless, FTR rates increased substantially across terciles among patients with major (low: 9.2%, high: 14.3%) and overall complications (low: 3.3%, high: 6.8%). Hospital observed and expected FTR rates were positively correlated among patients with major (R-squared=0.14) and overall (R-squared=0.51) complications.

Conclusions:

The reported interhospital variability in successful rescue following CABG supports the importance of identifying best practices at high-performing hospitals, including early recognition and management of complications.

Keywords: coronary artery bypass grafting, mortality, complications

INTRODUCTION

National efforts exist to advance hospital quality and safety. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services now publicly reports hospital performance related to both recommended practices and clinical outcomes for surgical and non-surgical conditions1. While the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) provides cardiac surgeons with benchmarking reports to support hospital-specific quality activities2, interhospital variability in mortality rates3.

Failure to rescue (FTR), defined as death following a complication, has been identified as an important contributor to interhospital variability in mortality. Reddy and colleagues, analyzing 45,904 coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and/or valve operations (2006 – 2010), reported that relative to low mortality tercile hospitals, high tercile hospitals had worse FTR rates (low tercile: 6.6%, high tercile: 13.5%, p<0.001). Overall complications, including 17 events, varied between 19.1% in the low mortality tercile and 22.9% in the high mortality tercile, p<0.001. A national analysis of isolated CABG (2010 – 2014) revealed a 4.3 percentage-point higher complication rate (including four major events) at high mortality tercile hospitals (low: 11.4%, high: 15.7%), although a 7.1 percentage-point higher FTR rate (6.8% versus 13.9%)4. Contemporary evaluations of interhospital FTR are warranted, based on both a broad and narrowly defined set of complications.

Among six cardiac surgical collaboratives, increasing hospital observed-to-expected (O:E) mortality terciles were compared in terms of their complication (broadly and narrowly defined) and FTR rates after isolated CABG.

METHODS

The University of Michigan IRB (HUM00127073) provided a Notice of Not Regulated Determination on 3/8/2017.

This study included 83,747 isolated CABG procedures (July 2011 to June 2017) from 90 hospitals participating in any of six quality collaboratives that in turn are members of the IMPROVE Network, eText 1.

Outcomes

Mortality included deaths within the hospitalization or after discharge but within 30-days of the surgical procedure5.

Failure to rescue (FTR) was defined as mortality among patients developing a postoperative complication.

A narrowly defined measure included STS major complications (stroke, surgical re-exploration, deep sternal wound infection, renal failure, prolonged intubation). A broader “overall complications” measure included STS major complications, sepsis, surgical site infection, coma, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, renal dialysis, dysrhythmia requiring a permanent pacemaker, cardiac arrest, anticoagulation event, tamponade, gastrointestinal event, multi-organ system failure, atrial fibrillation, aortic dissection.

Two FTR measures were calculated: major complications (68.3% of all deaths); overall complications (87.9% of all deaths).

Statistical Analyses

The STS’ approach for addressing missing values was applied, eMethods5.

Hospital-level observed mortality was calculated by summing each hospital’s observed mortality. Hospital-level expected mortality was calculated by summing each hospital’s mortality probability, estimated from logistic regression using STS published preoperative mortality risk model variables5. Hospitals were divided into performance terciles based on their O:E mortality3.

Patients characteristics, risk factors and complication conditions were stratified by hospital O:E mortality terciles, which were used for descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were summarized as median (interquartile range) and compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Categorical variables were summarized as n (%) and compared using Chi-squared tests. Cochran-Armitage Trend tests were used to test the trend of mortality, complication and FTR rates across hospital O:E mortality terciles.

Generalized linear mixed-effects models were used to develop FTR models (for major and overall complications). To address confounding, expected FTR rates were calculated by summing the patient’s probability of FTR within hospitals [accounting for significant preoperative mortality predictors and complication types], assuming an average hospital effect from the FTR models. R-squared was used to associate observed and expected hospital FTR rates. The C-statistic was used to evaluate the addition of cardiopulmonary bypass and crossclamp duration on improving FTR prediction.

Secondarily, Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were used to associate hospital procedural volume with observed and expected FTR (for major and overall complications).

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 and R version 3.5.2.

RESULTS

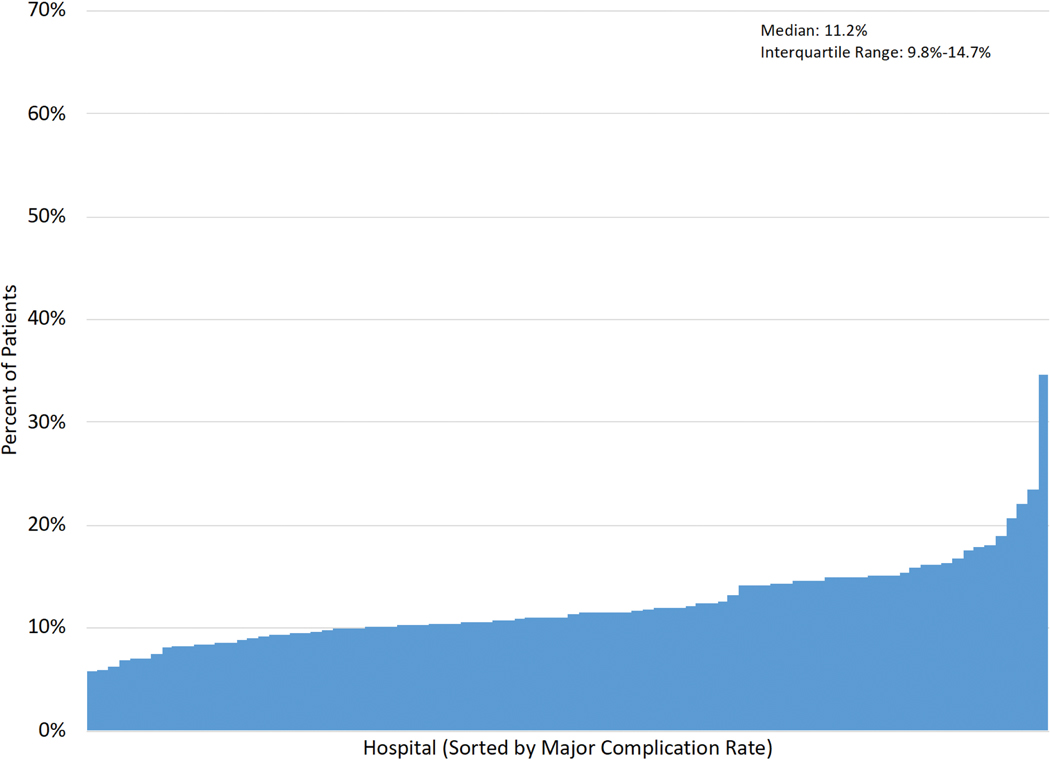

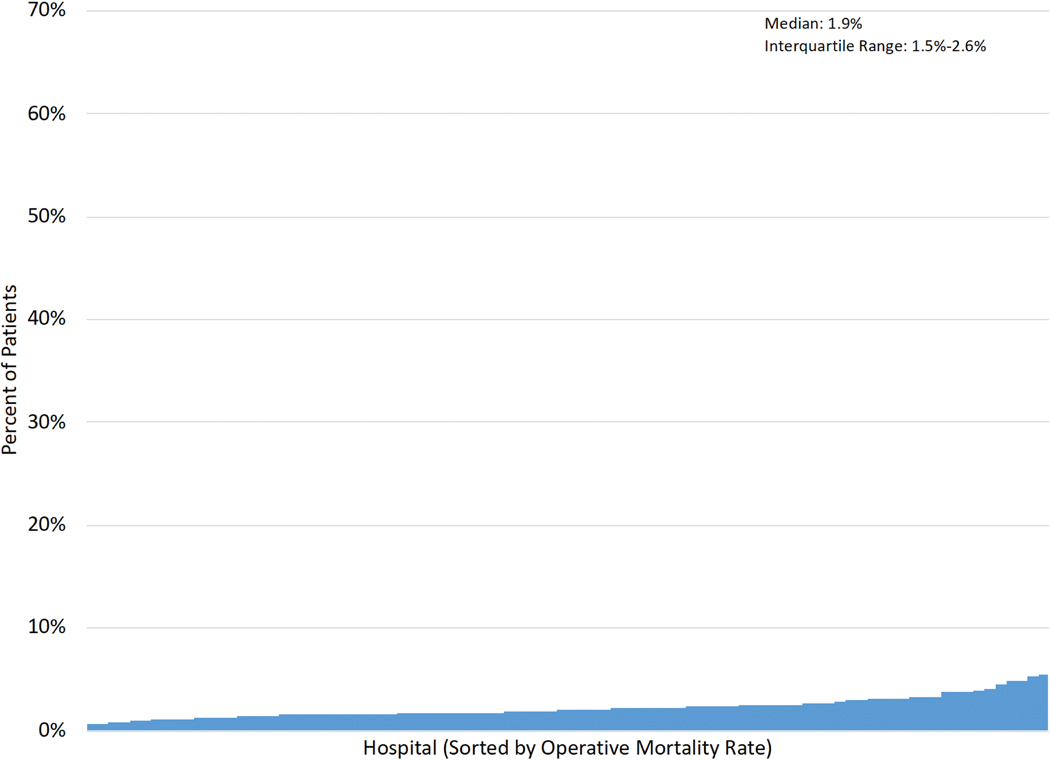

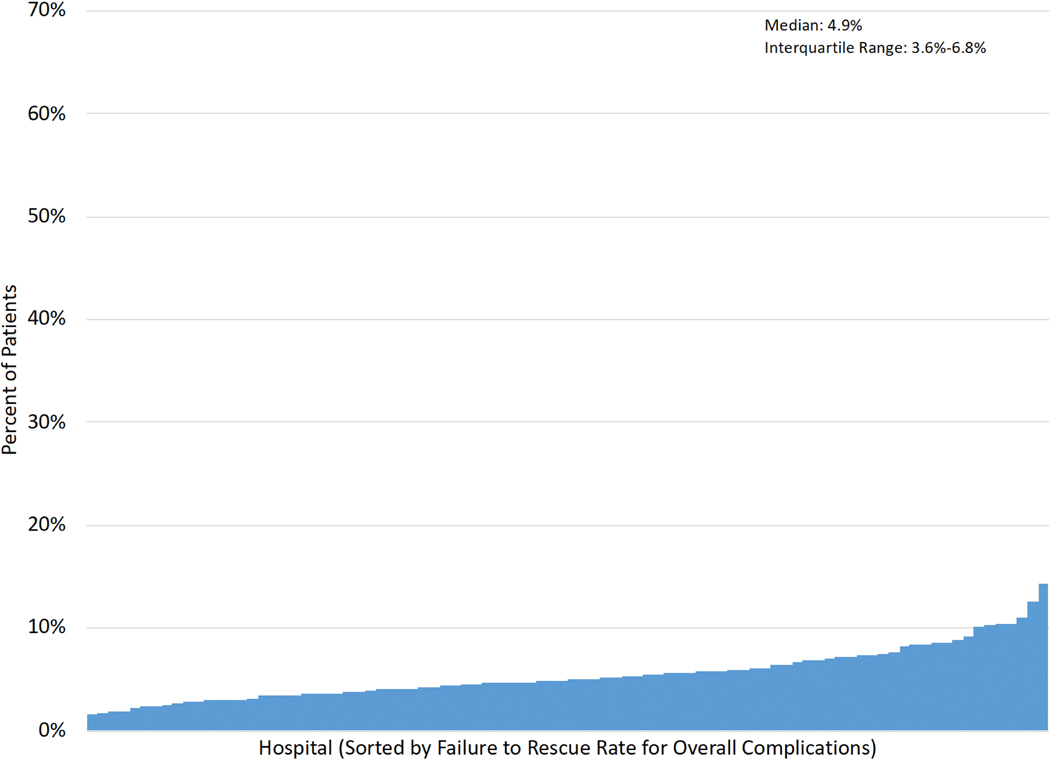

Figure 1A–E displays the distribution of hospital-level rates for complications (min:max. major: 5.7%−34.7%; overall: 21.6%−54.2%), mortality (0.6%−5.4%) and FTR (major: 3.5%−32.3%; overall: 1.5%−14.3%).

Figure 1 (A-E): Histograms of Interhospital Variability in Complication, Mortality and Failure to Rescue Rates.

Each figure is separately sorted by hospital.

A: Major complications; B: Overall complications; C: Operative mortality; D: FTR among major complications; E: FTR among overall complications.

Major complications included five STS-defined major morbidities.

Overall complications included the STS major and 14 additional morbidities.

Failure to Rescue (FTR): death among patients developing a complication.

Median STS predicted mortality risk was similar across O:E mortality terciles (p=0.831), Table 1. Patients at high (versus low) O:E mortality tercile hospitals more likely underwent urgent operations, p<0.001. Differences across O:E mortality terciles for many characteristics were small in absolute magnitude, while statistically significant. Relative to low O:E mortality tercile hospitals, patients in the high tercile hospitals were more likely to experience prolonged ventilation, cardiac arrest and operative mortality, p<0.001.

Table 1.

Overall Cohort by Hospital Observed:Expected Mortality Terciles

| Characteristic | Overall | Low O:E Mortality Tercile | Middle O:E Mortality Tercile | High O:E Mortality Tercile | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observations | 83747 | 33984 | 27864 | 21899 | |

| Preoperative Risk | |||||

| STS PROM (%) | 1.05 (0.58, 2.11) | 1.05 (0.58, 2.13) | 1.05 (0.58, 2.12) | 1.04 (0.58, 2.07) | 0.831 |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | 66.00 [58.00, 73.00] | 66.00 [59.00, 73.00] | 66.00 [58.00, 73.00] | 65.00 [58.00, 72.00] | <0.001 |

| Female | 20424 (24.4) | 7984 (23.5) | 6876 (24.7) | 5564 (25.4) | <0.001 |

| BSA | 2.05 [1.89, 2.23] | 2.06 [1.89, 2.23] | 2.05 [1.89, 2.23] | 2.05 [1.89, 2.23] | 0.079 |

| Caucasian | 71352 (85.2) | 30163 (88.8) | 23046 (82.7) | 18143 (82.8) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac History | |||||

| Angina | 20516 (24.5) | 7697 (22.6) | 7223 (25.9) | 5596 (25.6) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 74199 (88.6) | 29890 (88.0) | 24645 (88.4) | 19664 (89.8) | <0.001 |

| PVD | 12386 (14.8) | 5164 (15.2) | 4103 (14.7) | 3119 (14.2) | 0.008 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | <0.001 | ||||

| Cerebrovascular Disease Alone | 9229 (11.0) | 4174 (12.3) | 2940 (10.6) | 2115 (9.7) | |

| Cerebrovascular Disease and Stroke | 6449 (7.7) | 2456 (7.2) | 2121 (7.6) | 1872 (8.5) | |

| Myocardial Infarction | <0.001 | ||||

| <=6Hrs | 907 (1.1) | 401 (1.2) | 282 (1.0) | 224 (1.0) | |

| >6Hrs but <24Hrs | 1730 (2.1) | 625 (1.8) | 622 (2.2) | 483 (2.2) | |

| 1– 21days | 26594 (31.8) | 10393 (30.6) | 8614 (30.9) | 7587 (34.6) | |

| Arrhythmia | 11841 (14.1) | 4901 (14.4) | 3916 (14.1) | 3024 (13.8) | 0.113 |

| Congestive Heart Failure and NYHA Class | <0.001 | ||||

| had CHF, less than Class IV NYHA | 8244 (9.8) | 3969 (11.7) | 2653 (9.5) | 1622 (7.4) | |

| Class IV NYHA | 2979 (3.6) | 1340 (3.9) | 837 (3.0) | 802 (3.7) | |

| Prior Cardiovascular Intervention | 2202 (2.6) | 924 (2.7) | 782 (2.8) | 496 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Diseased Vessels, Number | <0.001 | ||||

| Two | 16339 (19.5) | 6943 (20.4) | 5536 (19.9) | 3860 (17.6) | |

| Three | 63906 (76.3) | 25623 (75.4) | 21073 (75.6) | 17210 (78.6) | |

| Risk Factors | |||||

| Ejection Fraction | 55.00 [45.00, 60.00] | 55.00 [45.00, 60.00] | 55.00 [45.00, 60.00] | 55.00 [45.00, 60.00] | <0.001 |

| <40 | 12673 (15.1) | 5075 (14.9) | 4158 (14.9) | 3440 (15.7) | <0.001 |

| 40–50 | 13130 (15.7) | 5372 (15.8) | 4250 (15.3) | 3508 (16.0) | |

| 50–60 | 26880 (32.1) | 11066 (32.6) | 8718 (31.3) | 7096 (32.4) | |

| Diabetes Control | <0.001 | ||||

| Insulin Control | 14553 (17.4) | 5684 (16.7) | 4918 (17.7) | 3951 (18.0) | |

| Diabetes with Other Control | 24308 (29.0) | 9929 (29.2) | 7920 (28.4) | 6459 (29.5) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 74945 (89.5) | 30884 (90.9) | 24315 (87.3) | 19746 (90.2) | <0.001 |

| Dialysis | 2259 (2.7) | 841 (2.5) | 764 (2.7) | 654 (3.0) | 0.001 |

| Chronic Lung Disease | <0.001 | ||||

| Mild | 12690 (15.2) | 4901 (14.4) | 4512 (16.2) | 3277 (15.0) | |

| Moderate | 3730 (4.5) | 1396 (4.1) | 1342 (4.8) | 992 (4.5) | |

| Severe | 3045 (3.6) | 1255 (3.7) | 1186 (4.3) | 604 (2.8) | |

| Immunosuppression | 2877 (3.4) | 1231 (3.6) | 929 (3.3) | 717 (3.3) | 0.046 |

| Cardiogenic Shock on Admission | 1493 (1.8) | 653 (1.9) | 513 (1.8) | 327 (1.5) | 0.001 |

| Intra-aortic Balloon Pump | 6125 (5.4) | 2440 (5.0) | 1888 (5.7) | 1797 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Left Main Disease | 28280 (33.8) | 11459 (33.7) | 9291 (33.3) | 7530 (34.4) | 0.05 |

| Laboratory Values | |||||

| Preoperative Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.00 [0.80, 1.20] | 1.00 [0.83, 1.20] | 1.00 [0.80, 1.20] | 1.00 [0.80, 1.20] | <0.001 |

| 0.8–1.0 | 26482 (31.6) | 10575 (31.1) | 8834 (31.7) | 7073 (32.3) | |

| 1.0–1.2 | 21976 (26.2) | 9234 (27.2) | 7128 (25.6) | 5614 (25.6) | |

| >=1.2 | 22192 (26.5) | 9170 (27.0) | 7222 (25.9) | 5800 (26.5) | |

| Acuity | <0.001 | ||||

| Urgent | 48858 (58.3) | 19123 (56.3) | 16018 (57.5) | 13717 (62.6) | |

| Emergent | 2878 (3.4) | 1258 (3.7) | 917 (3.3) | 703 (3.2) | |

| Emergent /Salvage | 91 (0.1) | 34 (0.1) | 43 (0.2) | 14 (0.1) | |

| Complication | |||||

| Major | 9697 (11.6) | 3779 (11.1) | 3245 (11.6) | 2673 (12.2) | <0.001 |

| Overall | 30265 (36.1) | 12442 (36.6) | 10094 (36.2) | 7729 (35.3) | 0.006 |

| Stroke | 1045 (1.2) | 413 (1.2) | 323 (1.2) | 309 (1.4) | 0.033 |

| Sepsis | 697 (0.8) | 266 (0.8) | 225 (0.8) | 206 (0.9) | 0.114 |

| Surgical Site Infection | 1237 (1.5) | 514 (1.5) | 419 (1.5) | 304 (1.4) | 0.445 |

| Deep Sternal Wound Infection | 288 (0.3) | 104 (0.3) | 103 (0.4) | 81 (0.4) | 0.302 |

| Re-operation | |||||

| Overall | 2880 (3.4) | 1123 (3.3) | 1007 (3.6) | 750 (3.4) | 0.109 |

| For Bleeding | 1380 (1.6) | 532 (1.6) | 484 (1.7) | 364 (1.7) | 0.244 |

| For Valve Dysfunction | 8 (0.0) | 4 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) | 0.842 |

| For Graft Occlusion | 163 (0.2) | 55 (0.2) | 62 (0.2) | 46 (0.2) | 0.196 |

| For Other Cardiac Indication | 333 (0.4) | 142 (0.4) | 122 (0.4) | 69 (0.3) | 0.072 |

| For Other Non-Cardiac Indication | 1281 (1.5) | 512 (1.5) | 440 (1.6) | 329 (1.5) | 0.712 |

| Coma | 1993 (2.4) | 793 (2.3) | 636 (2.3) | 564 (2.6) | 0.08 |

| Prolonged Ventilation | 6882 (8.2) | 2658 (7.8) | 2295 (8.2) | 1929 (8.8) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 2027 (2.4) | 750 (2.2) | 704 (2.5) | 573 (2.6) | 0.003 |

| Pulmonary Embolism | 139 (0.2) | 52 (0.2) | 52 (0.2) | 35 (0.2) | 0.574 |

| Renal Failure | 1681 (2.0) | 617 (1.8) | 587 (2.1) | 477 (2.2) | 0.004 |

| Renal Dialysis | 1001 (1.2) | 377 (1.1) | 348 (1.2) | 276 (1.3) | 0.166 |

| Dysrhythmia requiring permanent pacemaker | 1032 (1.2) | 396 (1.2) | 398 (1.4) | 238 (1.1) | 0.001 |

| Cardiac Arrest | 1523 (1.8) | 491 (1.4) | 515 (1.8) | 517 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Anticoagulation Event | 400 (0.5) | 144 (0.4) | 173 (0.6) | 83 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Tamponade | 21 (0.0) | 6 (0.0) | 10 (0.0) | 5 (0.0) | 0.352 |

| Gastrointenstinal Event | 1924 (2.3) | 889 (2.6) | 617 (2.2) | 418 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Multiorgan system failure | 456 (0.5) | 144 (0.4) | 145 (0.5) | 167 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 21536 (25.7) | 9110 (26.8) | 7044 (25.3) | 5382 (24.6) | <0.001 |

| Aortic Dissection | 36 (0.0) | 11 (0.0) | 18 (0.1) | 7 (0.0) | 0.103 |

| Mortality | 1648 (2.0) | 459 (1.4) | 573 (2.1) | 616 (2.8) | <0.001 |

Value is the “n (%)” for categorical data and the median [interquartile] for continuous data.

Abbreviations: NYHA: New York Heart Association Class; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; BSA: Body Surface Area; STS PROM: Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality

Figure 2 displays the differences in complication rates, operative mortality and unadjusted FTR by hospital O:E mortality terciles. Relative to the low hospital O:E mortality tercile, rates of major complications in the high tercile were 1.1 percentage-points greater (12.% versus 11.1%, ptrend<0.0001), overall complications 1.3 percentage-points lower (35.3% versus 36.6%, ptrend=0.002) and mortality 1.4 percentage-points higher (2.8% versus 1.4%, ptrend<0.0001). In contrast, and relative to the low hospital O:E mortality tercile, FTR rates were higher at high tercile hospitals, including 5.2 percentage-points higher for major complications (14.3% versus 9.1%, ptrend<0.0001) and 3.5 percentage-points higher for overall complications (6.8% versus 3.3%, ptrend<0.0001). The FTR rates were highest for cardiac arrest (48.9%), although varied by 15.8 percentage-points across O:E mortality terciles (high: 56.1%, low: 40.3%, p<0.001), Table 2.

Figure 2: Complication, Mortality and Failure to Rescue Rates by Hospital Observed:Expected Mortality Tercile<.

Major complications included five STS-defined major morbidities.

Overall complications included the STS major and 14 additional morbidities.

Failure to Rescue: death among patients developing a complication.

Expected mortality rates were calculated based on the STS mortality models.

O:E -> observed:expected hospital mortality tercile

Table 2.

Unadjusted Failure to Rescue Rates by Complication Type and Stratified by Hospital O:E Mortality Terciles

| Mortality (n) | Complication (n) | Failure to Rescue (FTR) Rates by Hospital O:E Mortality Terciles* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complication Type | Overall | Low Tercile | Middle Tercile | High Tercile | Absolute Difference (High versus Low Tercile) | Cochran-Armitage Trend Test | ||

| Major | 1126 | 9697 | 11.6 | 9.1 | 12.4 | 14.3 | 5.2 | <.0001 |

| Overall | 1448 | 30265 | 4.8 | 3.3 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 3.5 | <.0001 |

| Stroke | 174 | 1045 | 16.7 | 15.5 | 15.5 | 19.4 | 3.9 | 0.18 |

| Sepsis | 199 | 697 | 28.5 | 26.3 | 28.9 | 31.1 | 4.8 | 0.25 |

| Surgical Site Infection | 38 | 1237 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 0.47 |

| Deep Sternal Wound Infection | 22 | 288 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 10.7 | 4.9 | −1.8 | 0.73 |

| Re-operation | ||||||||

| Overall | 430 | 2880 | 14.9 | 14.4 | 15 | 15.6 | 1.2 | 0.48 |

| For Bleeding | 146 | 1380 | 10.6 | 9.8 | 11.4 | 10.7 | 0.9 | 0.59 |

| For Valve Dysfunction | 3 | 8 | 37.5 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 25.0 | 0.51 |

| For Graft Occlusion | 30 | 163 | 18.4 | 16.4 | 20.9 | 17.4 | 1.0 | 0.87 |

| For Other Cardiac Indication | 116 | 333 | 34.8 | 40.9 | 31.2 | 28.9 | −12.0 | 0.059 |

| For Other Non-Cardiac Indication | 216 | 1281 | 16.9 | 15.6 | 16.4 | 19.5 | 3.9 | 0.16 |

| Coma | 263 | 1993 | 13.2 | 10.5 | 13.5 | 16.7 | 6.2 | 0.0008 |

| Prolonged Ventilation | 978 | 6882 | 14.2 | 11.3 | 15.3 | 16.9 | 5.6 | <.0001 |

| Pneumonia | 250 | 2027 | 12.3 | 11.5 | 11.8 | 14.1 | 2.6 | 0.16 |

| Pulmonary Embolism | 13 | 139 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 3.9 | 20 | 12.3 | 0.087 |

| Renal Failure | 427 | 1681 | 25.4 | 19.3 | 27.9 | 30.2 | 10.9 | <.0001 |

| Renal Dialysis | 328 | 1001 | 32.8 | 24.7 | 36.2 | 39.5 | 14.8 | <.0001 |

| Dysrhythmia requiring permanent pacemaker | 39 | 1032 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 0.53 |

| Cardiac Arrest | 745 | 1523 | 48.9 | 40.3 | 49.9 | 56.1 | 15.8 | <.0001 |

| Anticoagulation Event | 99 | 400 | 24.8 | 27.8 | 21.9 | 25.3 | −2.5 | 0.54 |

| Tamponade | 6 | 21 | 28.6 | 16.7 | 20.0 | 60.0 | 43.3 | 0.13 |

| Gastrointenstinal Event | 249 | 1924 | 12.9 | 10.4 | 14.1 | 16.8 | 6.4 | 0.0008 |

| Multiorgan system failure | 353 | 456 | 77.4 | 75 | 77.9 | 79.0 | 4.0 | 0.40 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 543 | 21536 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 1.8 | <.0001 |

| Aortic Dissection | 4 | 36 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 28.6 | 28.6 | 0.06 |

Values represent frequency unless noted.

represent percentage

Major complications include five STS-defined events.

Abbreviation: FTR: Failure to Rescue.

Multivariable modeling estimates are presented for major and overall FTR outcomes in eTable 1. Bypass duration significantly predicted FTR (major complications: p=0.0003; overall: p<0.0001); however, crossclamp duration did not (major complications: p=0.39; overall: p=0.78). The addition of bypass and crossclamp duration did not change the C-statistic for the FTR major complication (0.78) or the overall complication (0.93) models.

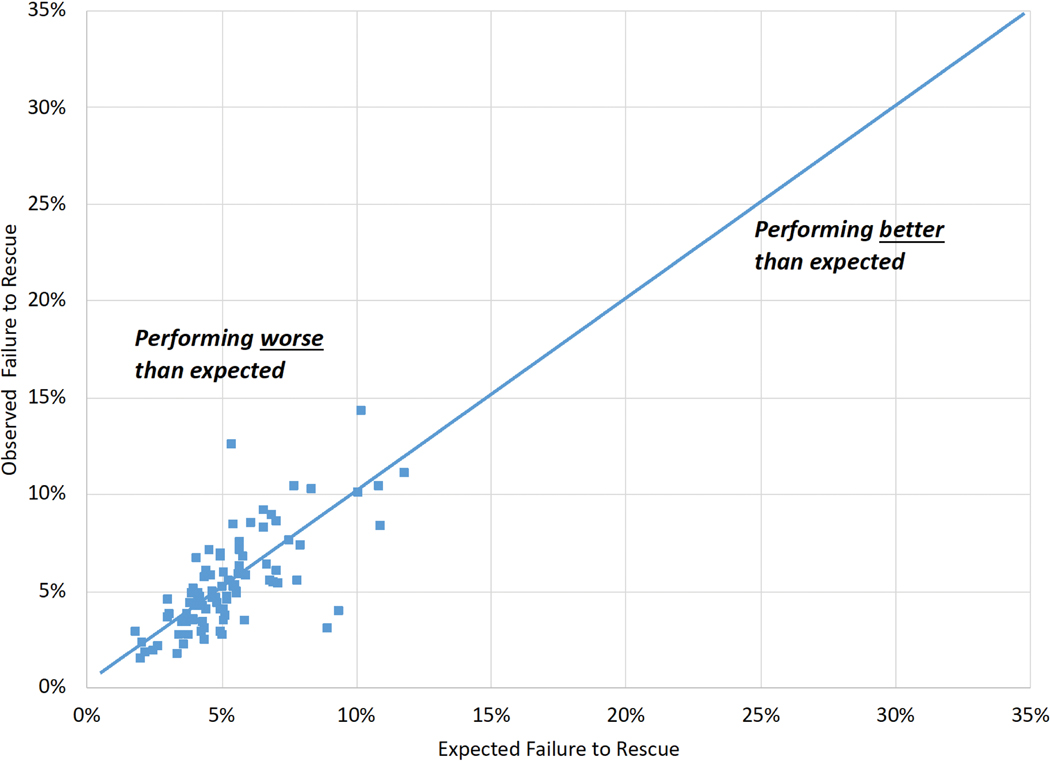

Hospital observed and expected FTR rates were less strongly correlated for patients with major (Figure 3A, R-squared=0.14) than overall complications (Figure 3B, R-squared=0.51).

Figure 3 (A-B). Variability in Observed and Expected Failure to Rescue by Hospital:

A: Failure to rescue among major complications (five STS-defined major morbidities).

B: Failure to rescue among overall complications (STS major and 14 additional morbidities).

Expected values, derived from multivariable regression models, represent the expected hospital failure to rescue rate.

Hospital procedural volume was not significantly associated with observed (r=−0.13, p=0.21) and expected (r=−0.022, p=0.84) FTR rates for major complications. Hospital procedural volume was negatively correlated with observed (r=−0.32, p=0.0023) and expected (r=−0.36, p =0.0005) FTR rates for overall complications.

DISCUSSION

This study yields four distinct findings that establish the importance of identifying and disseminating optimal CABG rescue strategies. First, observed FTR rates varied 28.8 percentage-points across hospitals for major complications and 12.8 percentage-points for a broad set of complications. Second, FTR rates, both for major and overall complications, were greater at high relative to low O:E mortality tercile hospitals. When compared across terciles, there was: (i) no difference in median predicted mortality risk, (ii) small differences in major and overall complications, and (iii) a two-fold increased mortality risk at high versus low O:E mortality tercile hospitals. Third, complication-specific FTR rates varied within and across O:E mortality hospital terciles. Fourth, observed and expected hospital FTR rates were positively correlated although weaker for major complications.

Investigators have evaluated the role of FTR within adult3,4,6 and congenital7 cardiac surgical populations. Ghaferi and colleagues, analyzing national Medicare claims for CABG6, reported 1.1-fold variability in complication rates across mortality quintile hospitals (low: 21.1% versus high quintile: 24.2%) although 3.1-fold (6.2% versus 18.9%) FTR. These findings suggest that interhospital variation in mortality is driven by how a hospital manages complications rather than complication rates themselves.

Reddy and colleagues evaluated interhospital variability in rates of complications, mortality and FTR across terciles of O:E mortality3. In the Reddy study, despite similar complication rates across terciles, mortality rates were 2.1 percentage points higher (3.6% versus 1.5%) and FTR rates 6.9 percentage-points higher (13.5% versus 6.6%) at high versus low tercile hospitals.

Edwards and colleagues compared rates of complications and FTR across terciles of hospital mortality rates among 604,154 patients undergoing isolated CABG4. Complication rates, defined narrowly (stroke, renal failure, reoperation or prolonged ventilation), varied 4.3 percentage-points (high tercile: 15.7%, low tercile: 11.4%) while FTR rates varied 7.1 percentage-points (13.9% versus 6.8%)4. Reddy and Edwards had noteworthy differences in their study sample (e.g., time periods, evaluated surgical procedures) and set of morbid events included within their complication measures.

In our current study, hospital observed and expected FTR rates were weakly correlated, especially among patients developing major complications. Further work is required to identify important organizational and unit-level determinants of hospital FTR. Hospital procedural volume was negatively associated with observed FTR rates for patients developing overall complications although not for major complications. While Gonzalez and colleagues reported a significant 16% increased relative odds of FTR after CABG at low-versus high-volume quintile hospitals8, Edwards and colleagues did not find a significant relationship between volume and FTR4.

Since Silber’s original report9, a number of patient-level risk factors for FTR have been documented10. Potentially modifiable determinants have also been reported (e.g., early recognition of patient deterioration11 and nurse staffing and educational levels12), with many confirmed across a variety of surgical cohorts13,14 and data sources4,6,8,15. Reported interhospital variability in FTR rates has contributed to current public reporting of hospital FTR rates.

Prior reports have identified potential unit- (nurse:patient ratios12,16,17) and hospital (rapid response teams18,19) FTR targets. Ward and colleagues merged survey data reflecting microsystem-level practices with registry data representing general surgery operations at 54 hospitals20. Relative to high FTR tercile hospitals, low tercile hospitals were more likely to have: (i) closed intensive care units, (ii) hospitalists, residents or board-certified intensivists, (iii) advanced practice providers, (iv) overnight coverage and (v) rapid response teams. Our findings of a weak positive correlation between a hospital’s observed and expected FTR rate for major complications suggest the need to identify how institutional resources and practices are differentially employed at high performing hospitals. Reductions in interhospital variability in FTR may result from leveraging collaborative learning21 to reveal currently unexplained modifiable unit- and hospital-level FTR determinants22.

This study has several limitations. First, while not all complications were evaluated, this study focused on both a narrow set of STS-defined and publicly reported major complications23 as well as a broader that are tracked by the STS24. Second, while unmeasured confounding persists, this study accounted for pre-operative factors included in the STS’ risk models5. While the inclusion of cardiopulmonary bypass and crossclamp duration did not appreciably improve our FTR prediction model’s discrimination, we cannot rule out the influence of other intraoperative confounding. Third, while the present findings may not be universally generalizable, our study includes hospitals across the U.S. and low and high-volume hospitals.

CONCLUSIONS

Considerable variation in FTR rates existed across O:E mortality terciles (Figure 4) after isolated CABG despite similar STS predicted mortality risk and small differences in complication rates. Given that existing clinical registry data are limited in their ability to predict observed hospital FTR rates, important modifiable FTR targets may be identified through benchmarking visits to high-performing hospitals.

Figure 4:

Interhospital variability in mortality was attributed to failure to rescue (FTR). FTR rates were higher for patients in high observed:expected (O:E) mortality tercile hospitals. Successful rescue differed by complication type and across O:E terciles. Hospital observed and expected FTR rates were correlated although weaker for major complications.

Supplementary Material

Author Video

Interhospital variability in mortality was attributed to failure to rescue (FTR). FTR rates were higher for patients in high observed:expected (O:E) mortality tercile hospitals. Successful rescue differed by complication type and across O:E terciles. Hospital observed and expected FTR rates were correlated although weaker for major complications.

CENTRAL MESSAGE.

Rescue strategies should be identified and prioritized given interhospital variation in mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting is driven principally by a hospital’s failure to rescue rate.

PERSPECTIVE STATEMENT.

In this multi-collaborative cohort of 83,747 isolated coronary artery bypass procedures, significant interhospital variation in mortality rates was driven principally by failure to rescue rates rather than complication rates. Efforts to reduce mortality should focus on identifying and implementing optimal rescue strategies.

CENTRAL PICTURE.

Variability in mortality is driven by differences in failure to rescue, not complications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Drs. Glenn Whitman and Gaetano Paone for their contributions.

Drs. Likosky, Wu and Zhang had access to all data and take responsibility for data integrity and analytical accuracy. All authors participated in the design, interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the AHRQ, NIH or the DHHS.

Sources of Funding: Drs. Thompson and Likosky receive salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. Donald S. Likosky received extramural support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, R01HS026003) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH, R01HL146619-01A1), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Raymond J. Strobel received funding support from MICHR TL1 Grant Number TL1TR002242. Support for the Michigan Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeons Quality Initiative is provided by Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network as part of the BCBSM Value Partnerships program.

This study was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (HUM00127073) and provided a Notice of Not Regulated Determination on 3/8/2017.

GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS

- CABG

Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

- FTR

Failure to Rescue

- STS

Society of Thoracic Surgeons

Footnotes

Membership of the IMPROVE Network is provided in the Supplemental material.

Conflicts of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Hospital Compare. Medicare.gov | Hospital Compare. Accessed October 16, 2020. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html?

- 2.Homepage | STS. Accessed March 30, 2020. http://www.sts.org

- 3.Reddy HG, Shih T, Englesbe MJ, Shannon FS, Theurer PF, Herbert MA, et al. Analyzing “failure to rescue”: is this an opportunity for outcome improvement in cardiac surgery? Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(6):1976–1981; discussion 1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards FH, Ferraris VA, Kurlansky PA, Lobbdell KW, He X, O’Brien SM, et al. Failure to Rescue Rates After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: An Analysis From The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102(2):458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahian DM, O’Brien SM, Filardo G, Ferraris VA, Haan CK, Rich JB, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 1--coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(1 Suppl):S2–S22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Complications, failure to rescue, and mortality with major inpatient surgery in medicare patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250(6):1029–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasquali SK, He X, Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, O’Brien SM, Gaynor JW. Evaluation of failure to rescue as a quality metric in pediatric heart surgery: an analysis of the STS Congenital Heart Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(2):573–579; discussion 579–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez AA, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer JD, Ghaferi AA. Understanding the volume-outcome effect in cardiovascular surgery: the role of failure to rescue. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(2):119–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silber JH, Williams SV, Krakauer H, Schwartz JS. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with death after surgery. A study of adverse occurrence and failure to rescue. Med Care. 1992;30(7):615–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph B, Zangbar B, Khalil M, Kulvatunyou N, Haider AA, O’Keeffe T, et al. Factors associated with failure-to-rescue in patients undergoing trauma laparotomy. Surgery. 2015;158(2):393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston MJ, Arora S, King D, Bouras G, Almoudaris AM, Davis R, et al. A systematic review to identify the factors that affect failure to rescue and escalation of care in surgery. Surgery. 2015;157(4):752–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Cheung RB, Sloane DM, Silber JH. Educational levels of hospital nurses and surgical patient mortality. JAMA. 2003;290(12):1617–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghaferi AA, Dimick JB. Importance of teamwork, communication and culture on failure-to-rescue in the elderly. British Journal of Surgery. 2016;103(2):e47–e51. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friese CR, Lake ET, Aiken LH, Silber JH, Sochalski J. Hospital nurse practice environments and outcomes for surgical oncology patients. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(4):1145–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghaferi AA, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Hospital characteristics associated with failure to rescue from complications after pancreatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(3):325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987–1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pucher PH, Aggarwal R, Singh P, Darzi A. Enhancing surgical performance outcomes through process-driven care: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2014;38(6):1362–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beitler JR, Link N, Bails DB, Hurdle K, Chong DH. Reduction in hospital-wide mortality after implementation of a rapidresponse team: a long-term cohort study. Critical Care. 2011;15(6):R269. doi: 10.1186/cc10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karpman C, Keegan MT, Jensen JB, Bauer PR, Brown DR, Afessa B. The Impact of Rapid Response Team on Outcome of Patients Transferred From the Ward to the ICU. Critical Care Medicine. 2013;41(10):2284–2291. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e318291cccd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward ST, Dimick JB, Zhang W, Campbell DA, Ghaferi AA. Association Between Hospital Staffing Models and Failure to Rescue. Ann Surg. Published online March 19, 2018. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Likosky DS, Harrington SD, Cabrera L, DeLucia A 3rd, Chenoweth CE, Krein SL, et al. Collaborative Quality Improvement Reduces Postoperative Pneumonia After Isolated Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(11):e004756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGrath SP. Failure to Rescue Event Mitigation System Assessment: A Mixed-methods Approach to Analysis of Complex Adaptive Systems. In: Wells E, ed. Structural Approaches to Address Issues in Patient Safety. Vol 18. Advances in Health Care Management. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2019:119–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Quality Forum. National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Cardiac Surgery. National Quality Forum. Accessed November 13, 2019. https://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/c-d/Cardiac_Surgery/Cardiac_Surgery.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adult Cardiac Surgery Database | STS. Accessed April 5, 2020. https://www.sts.org/registries-research-center/sts-national-database/adult-cardiac-surgery-database.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Author Video

Interhospital variability in mortality was attributed to failure to rescue (FTR). FTR rates were higher for patients in high observed:expected (O:E) mortality tercile hospitals. Successful rescue differed by complication type and across O:E terciles. Hospital observed and expected FTR rates were correlated although weaker for major complications.