Abstract

Cyclospora cayetanensis is an apicomplexan protozoan parasite which has emerged as an important cause of epidemic and endemic diarrhea. Water-borne as well as food-borne outbreaks have occurred, including a large number of U.S. cases associated with raspberries imported from Guatemala. Molecular markers exist for tracing the epidemiology of many of the bacterial pathogens associated with water-borne or food-borne diarrhea, such as serotyping and pulsed-field electrophoresis. However, there are currently no molecular markers available for C. cayetanensis. The intervening transcribed spacer (ITS) regions between the small- and large-subunit rRNA genes demonstrate much greater sequence variability than the small-subunit rRNA sequence itself and have been useful for the molecular typing of other organisms. Thus, ITS1 variability might allow the identification of different genotypes of C. cayetanensis. In order to determine the degree of ITS1 variability among C. cayetanensis isolates, the ITS1 sequences of C. cayetanensis isolates from a variety of sources, including raspberry-associated cases, cases from Guatemala, and pooled and individual isolates from Peru, were obtained. The ITS1 sequences of all five raspberry-associated isolates were identical, consistent with their origin from a single source. In contrast, one of the two Guatemala isolates and two Peruvian isolates contained multiple ITS1 sequences. These multiple sequences could represent multiple clones from a single clinical source or, more likely, variability of the ITS1 region within the genome of a single clone.

Cyclospora cayetanensis is an apicocomplexan protozoan organism which has recently been documented as a cause of human diarrhea. The organism was initially thought to be a coccidian parasite (2), a cyanobacterium-like body (11, 17), or a coccidian-like body (3). The organism was confirmed to be a coccidian parasite in the genus Cyclospora when the oocysts were induced to sporulate, yielding two sporocysts, each containing two sporozoites (15, 16). Numerous mammalian and avian species have been evaluated for the presence of C. cayetanensis oocysts. The human is the only host identified to date, although a closely related Cyclospora species has been isolated from baboons (12). Efforts to grow the organism in vitro or in animal models have not yet been successful. Therefore, the only DNA available for experimental use is that obtained from human fecal specimens, and relatively little is known regarding the genome organization or gene sequences of C. cayetanensis. However, the small-subunit rRNA (SSrRNA) sequence was obtained by PCR amplification using primers based on the highly conserved regions of the SSrRNA. Analysis of the SSrRNA sequence obtained by PCR revealed that C. cayetanensis is closely related to Eimeria spp. (18).

The SSrRNA sequence is very useful for phylogenetic analysis but is less useful for molecular typing within a single species because it is so highly conserved. However, the ITS1 (internal transcribed sequence 1) region between the SSrRNA and 5.8S rRNA is not as highly conserved because it does not have the same structure-function constraints and might provide a tool for molecular typing. rRNA coding regions frequently exist as a tandem array of repeats that each contain the SSrRNA, ITS1, 5.8S rRNA, ITS2, large-subunit rRNA, and the intergenic region. When the ribosomal region exists as a tandem array, the copies will all be identical or nearly identical because the mutations are homogenized by frequent crossing-over within the tandem array. Therefore, these ribosomal DNA (rDNA) units remain identical or nearly identical in sequence within cloned populations. The SSrRNA sequences are highly conserved, limiting their discriminatory power for closely related organisms. However, the ITS1 regions have less functional constraint than the SSrRNA in terms of sequence and therefore demonstrate much greater variability between species and between clones within species. Because of these features, ITS1 regions have been useful for molecular typing of a variety of organisms, such as the fungi Torulaspora and Zygosaccharomyces (8). However, certain other apicocomplexa, such as Plasmodium falciparum (5, 20) and Cryptosporidium parvum (10), have been found to have more than one sequence type of the ribosomal gene. Expression of the different rRNA genes is developmentally regulated in P. falciparum.

In 1996, an outbreak of 1,465 reported cases of diarrhea due to C. cayetanensis occurred in North America, with a predominance of cases in the eastern United States and Canada (6). This outbreak was initially thought to be from strawberries, but subsequently was attributed to raspberries imported from Guatemala. In this paper, we present the ITS1 sequences of five isolates associated with the 1996 epidemic as well as two endemic isolates from Guatemala and four from Peru. The data suggest that C. cayetanensis contains multiple copies of the ribosomal gene that vary in their ITS1 sequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. cayetanensis oocysts.

Samples containing unsporulated C. cayetanensis oocysts were obtained from infected individuals living in a region of Peru where it is endemic. They were screened for the presence of C. cayetanensis oocysts by light microscopy, autofluorescence, and acid-fast staining. The Guatemalan isolates were provided by Caryn Bern from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and isolates from the 1996 outbreak were provided by Marek Pawlowicz, from the Florida Department of Health. Samples containing C. cayetanensis oocysts were transported to the University of Arizona for further purification and DNA isolation. Samples were passed through gauze to remove large pieces of fecal material. Oocysts were concentrated by sequential differential centrifugation steps using a modified Ritchie method, followed by sucrose flotation in Sheather's solution (1).

Modified ethyl acetate (Ritchie) method.

Fecal matter was diluted in a volume of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) that would liquefy the specimen to allow purification of the oocysts. This was typically about 10 g per 25 ml. Twenty-five milliliters of the diluted fecal matter was then mixed with 5 ml of ethyl acetate and vortexed well for 1 min followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 960 × g. The supernatant and the thick top layer and middle layer were poured off. Pellets from each sample were resuspended in 0.1 M PBS, combined, and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 25 min. Before incubation in potassium dichromate, samples were treated with diluted bleach (1.75% sodium hypochlorite) for 10 min. Pellets were resuspended in 2.5% potassium dichromate and stored at 4°C.

Discontinuous sucrose gradients.

Sucrose gradients were prepared using a Sheather's solution (500 g of sucrose, 320 ml of water, and 9 ml of phenol). Ten milliliters of 1:4 sucrose (200 ml of Sheather's, 800 ml of 0.25 M PBS, and 9 ml of Tween 80; density = 1.064 g/liter) was placed into 50-ml tubes. The 1:4 layer was underlayered carefully with 10 ml of 1:2 sucrose (300 ml of Sheather's, 600 ml of 0.25 M PBS, 9 ml of Tween 80; density = 1.103 g/liter). Five milliliters of the sample was placed on top of the gradient. Tubes were centrifuged for 25 min at 960 × g. The supernatant and interphase were transferred into clean, labeled tubes and centrifuged for 10 min at 1,500 × g. Pellets were resuspended in 2.5% potassium dichromate. The number of C. cayetanensis oocysts was recorded, and samples were then refrigerated at 4°C.

Oocyst lysis.

Oocysts were washed twice with distilled water and PCR buffer. The samples were resuspended in 40 μl of 1× PCR buffer and 20 μl of Instagene gel matrix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.), added with constant stirring. Oocysts were lysed with six freeze/thaw cycles by exposing them to liquid nitrogen followed by boiling water. The adequacy of the disruption of the oocyst wall was monitored by microscopy. Samples were vortexed and centrifuged, and the supernatant was used for DNA extraction.

PCR and sequence analysis.

The initial PCR primers were based on the known sequence of the 3′ end of the SSrRNA sequence (18) and the conserved regions of the 5.8S rRNA gene (Table 1). Subsequent C. cayetanensis ITS1 primers were constructed based on the sequence obtained with the initial primers. The amplified products were cloned into pBlueScriptII plasmid vectors and sequenced using an ABI 377 sequencer. All clones were sequenced in both directions with the exception of two clones each from isolates 5427 and 5436 because of the presence of multiple inserts in these clones. Only those clones sequenced in both directions are included in the data presented in Fig. 1 and 2. Discrepancies between the two strands as well as differences among clones were clarified by careful manual examination of the tracings. Sequence alignments were performed using the Clustal method (7).

TABLE 1.

Conserved portion of 5.8S rRNA sequences

| Organism | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| Toxoplasma gondii | CGA TGA AGG ACG CAG CGA ACT GCG A |

| Trypanosoma brucei | TGA AGA ACG CAG CAA AGT GCG A |

| Plasmodium falciparum | CGA TGA AGG CCG CAG CAA AAT GCG A |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | CGA TGA AGA ACG CAG CGA AAT GCG A |

| Candida albicans | CGA TGA AGA ACG CAG CGA AAT GCG A |

| “Conserved” sequence | CGA TGA AGA ACG CAG CAA AAC GCG A |

| Cyclospora Cyc58r2b | CGA TGA AGG ACG CAG CGA ACT GCG |

| Cyclospora cayetanensis | CGA TGA AGG ACG CAG CGA AAT GCG A |

Nucleotides that differ from the experimentally determined Cyclospora sequence are underlined.

Shown here as the forward sequence.

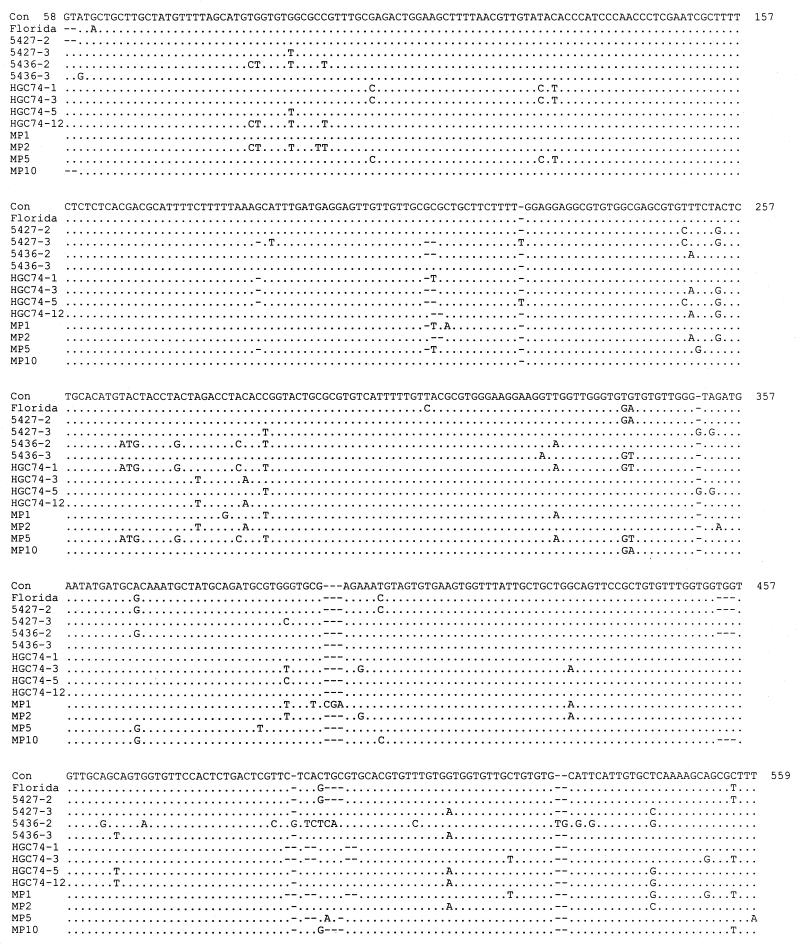

FIG. 1.

Clustal alignment of each of the distinct sequences from nucleotides 58 to 559. When two or more sequences are identical, only one sequence is shown. For example, HCG73, HGC74-2, C561, 5399, and all the Florida sequences were identical. Only the Florida sequence is shown. (However, all are shown in the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 2.) Nucleotides 1 to 57 and 560 to 609 were identical for all clones sequenced and are not shown. (Even though the maximum ITS1 length was 604 bp, the gaps introduced in the alignments resulted in numbering through 609.) The dots indicate identity with the consensus sequence (Con), and dashes indicate gaps. The isolate name or number is on the left. The consensus sequence is not weighted for the numerous sequences that were identical to the Florida sequence. G as the first letter indicates Guatemalan isolates, P indicates Peruvian isolates, and MP indicates the mixed Peruvian isolates. The number following the dash represents the specific cloned PCR product of the ITS1 region of that isolate.

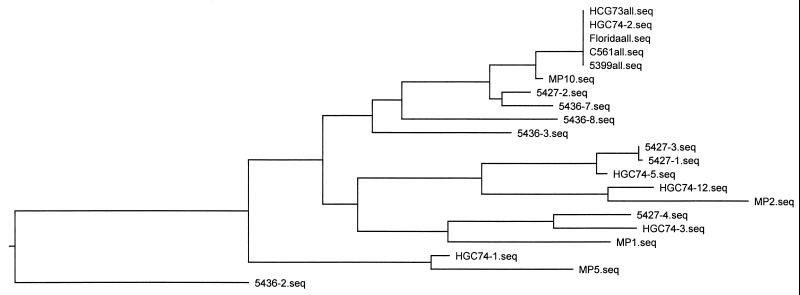

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the ITS1 sequences from Fig. 1.

RESULTS

The ITS1 sequence.

The initial ITS1 sequence was obtained by PCR amplification of DNA from pooled Peruvian Cyclospora isolates. The forward primer was derived from the 3′ end of the SSrRNA sequence (18), called Cycssf1 (Table 2). Since specific sequence was not available for the ITS1 region, the reverse primer was derived from the conserved region of the 5.8S rRNA sequence (Cyc58r1). The 5.8S rRNA sequences of Toxoplasma gondii, Trypanosoma brucei, P. falciparum, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Candida albicans were aligned, and the most conserved region was chosen for designing the primer (Table 1). At the sites where differences were present, the Toxoplasma sequence was chosen. The sequence data from the initial Cyclospora amplified ITS1 product was used to design a reverse primer based on specific Cyclospora sequence rather than the conserved 5.8S sequence. The 5′ and 3′ regions of ITS1 were identical for all the mixed Peruvian (and subsequent) isolates; therefore, internal primers were constructed so that nested reactions could be performed.

TABLE 2.

C. cayetanensis primers

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Cyc58r2 | CGC AGT TCG CTG CGT CCT TCA TCG |

| Cycssf1 | GCA AAA GTC GTA ACA CGG TTT CC |

| ITS1f1-20 | GTA GGT GAA CCT GCG GAA GG |

| ITS1f23-42 | CAT TCA CAC ATT CTG TGT CG |

| ITS1f27-45 | CAC ACA TTC TGT GTC GAG C |

| ITS1r630-611 | CGA GCC AAG ACA TCC ATT GC |

| ITS1r581-561 | GGA GTG TCG CGC GAC AAA CAC |

Variability of the ITS1 sequence in C. cayetanensis DNA from pooled Peruvian isolates.

The initial step for determining the degree of genetic heterogeneity among C. cayetanensis isolates was to determine the ITS1 sequences present in DNA from a pooled set of Peruvian C. cayetanensis isolates. The presence of multiple distinct sequences would suggest substantial variability among the multiple isolates present in the pooled sample, while a lack of variability would indicate a lack of sequence variability among isolates. Differences were identified among each of eight sequences determined, suggesting that this technique would have good discriminatory power. Four of the sequences are shown in Fig. 1 (MP 1, 2, 5, and 10).

ITS1 sequence from epidemic-associated isolates.

The ITS1 sequence was then determined from five different isolates obtained from the 1996 outbreak. The expectation was that if these isolates were epidemiologically related, the ITS1 sequences would be identical. In order to evaluate the possibility of intraisolate variability and to rule out the possibility of errors introduced by PCR amplification, multiple clones were sequenced for each of the isolates (from 2 to 12 clones for each isolate; Table 3). Indeed, the sequences of all the clones from each of the five isolates were identical and are shown as Florida in Fig. 1.

TABLE 3.

Cyclospora clones and isolates sequenced

| Source and isolate | No. of clones sequenced | Intra-isolate variabilitya (no. of variants) |

|---|---|---|

| Peru | ||

| Pooled isolates | 8 | NA (4) |

| PC561 | 3 | No |

| P5399 | 2 | No |

| P5427 | 4 | Yes (2) |

| P5436 | 4 | Yes (4) |

| Guatemala | ||

| GHCG73 | 4 | No |

| GHCG74 | 11 | Yes (5) |

| Florida | ||

| 10859 | 4 | No |

| 9703 | 12 | No |

| 17182 | 4 | No |

| 9444 | 4 | No |

| 17428 | 12 | No |

NA, not applicable.

Variability of the ITS1 sequence in Guatemalan and Peruvian isolates.

Subsequently, the ITS1 sequence was obtained for other isolates, including two Guatemalan isolates collected near the raspberry-growing area and four isolates from Peru, again sequencing several clones from each isolate. The epidemic isolates were identical to one of the Guatemalan isolates (HGC73) and two of the Peruvian isolates (C561 and 5399). In addition, one of the clones from the other Guatemalan isolate (HGC74) was identical to the epidemic isolates.

In contrast, multiple different ITS1 sequences were obtained from the other Peruvian and Guatemalan isolates. Seven of the 11 clones from HCG74 (Guatemala) were identical to each other and to the Florida isolates. The remaining four HGC74 clones were all distinct from each other (Fig. 1 and 2). Four clones each were sequenced from the Peruvian isolates, 5427 and 5436; all were different (Fig. 1 and 2).

The starting point of the ITS1 sequence was considered to be the first nucleotide after the end of the published SSrRNA sequence, while the end was considered to be the last nucleotide before the beginning of the 5.8S rRNA sequence, as determined by alignment with the Saccharomyces and Candida sequences. The ITS1 sequences varied by additions and deletions up to 3 nucleotides in length as well as nucleotide substitutions. They varied from 596 to 604 bp in length.

DISCUSSION

The finding of four distinct ITS1 sequences in the pooled Peruvian isolates from a total of eight sequences suggested the likelihood of variability of this region among isolates. In comparison, the uniformity of the isolates associated with the Florida epidemic is consistent with a clonal source for the outbreak.

However, the finding of multiple ITS1 sequences from isolates from infected humans in Guatemala and Peru has made the interpretation of these results less straightforward. We propose three possible explanations for the variability of ITS1 sequences from individual isolates. (i) The differences are a PCR artifact. However, infidelity due to Taq polymerase is usually less than 10−3 and most often consists of single-nucleotide substitutions. Indeed, no substitutions were detected in the 36 clones sequenced from the Florida isolates (>20 kb of sequence), consistent with an infidelity rate of <10−4. For comparison, the differences among the variant clones were typically 1 to 2% and included insertions or deletions of up to 3 nucleotides, changes that would be very unusual from infidelity of the Taq polymerase. (ii) Each of the subjects from whom fecal specimens were obtained had a mixture of isolates from different sources. The finding of four or five different ITS1 sequences in several isolates suggests that this explanation is statistically unlikely because of the low likelihood of multiple distinct isolates from multiple patients. This is generally true in the case of a low-prevalence infection (1.1% in children in a shantytown in Peru) (13) because of the low likelihood that any specific patient will develop simultaneous infections with multiple organisms. (Of course, an exception to this likelihood would occur if there was a selective advantage for the coexistence of two genotypes in a single host.) (iii) Cyclospora organisms have multiple divergent copies of the rRNA genes. Indeed, variability of the rRNA genes has been documented within single isolates for a variety of other organisms, including other apicocomplexa. Perhaps the most notable example of rRNA heterogeneity is that found in several of the Plasmodium species. These organisms have three distinct sets of rDNA genes that are expressed during different stages in the life cycle (14, 19). A number of other apicocomplexan organisms, including Cryptosporidium parvum (10), Babesia bovis (4), and Theileria parva (9), also demonstrate divergence of the rDNA units. The ITS1 variability in Cyclospora suggests the possibility that the rDNA units may be dispersed within the genome so that complete homogenization of the units does not occur.

We believe this third explanation is the most likely reason for the ITS1 variability in Cyclospora. However, the major deficiency of this latter explanation is its inability to explain why only a single ITS1 sequence was detected in the epidemic-associated isolates. Alternatively, it remains possible that many human Cyclospora infections are characterized by multiclonality of the infecting organisms. These potential explanations can be tested by sequence comparisons of single-copy genes from isolates obtained from a variety of epidemic and endemic infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Lynda Schurig and Stephanie Jones for technical assistance and to Bill Birky for helpful comments.

This work has been supported by NIH grant RO3AI41631 to R.D.A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arrowood M J, Sterling C R. Isolation of Cryptosporidium oocysts and sporozoites using discontinuous sucrose and isopycnic Percoll gradients. J Parasitol. 1987;73:314–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashford R W. Occurrence of an undescribed coccidian in man in Papua New Guinea. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1979;73:497–500. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1979.11687291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendall R P, Lucas S, Moody A, Tovey G, Chiodini P L. Diarrhoea associated with cyanobacterium-like bodies: a new coccidian enteritis of man. Lancet. 1993;341:590–592. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90352-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalrymple B P. Cloning and characterization of the rRNA genes and flanking regions from Babesia bovis: use of the genes as strain discriminating probes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;43:117–124. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90136-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunderson J H, Sogin M L, Wollett G, Hollingdale M, de la Cruz V, Waters A P, McCutchan T F. Structurally distinct, stage-specific ribosomes occur in Plasmodium. Science. 1987;238:933–937. doi: 10.1126/science.3672135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herwaldt B L, Ackers M L. An outbreak in 1996 of cyclosporiasis associated with imported raspberries. The Cyclospora Working Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1548–1556. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705293362202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins D G, Sharp P M. Fast and sensitive multiple sequence alignments on a microcomputer. Comput Appl Biosci. 1989;5:151–153. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James S A, Collins M D, Roberts I N. Use of an rRNA internal transcribed spacer region to distinguish phylogenetically closely related species of the genera Zygosaccharomyces and Torulaspora. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:189–194. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kibe M K, K. ole-MoiYoi O, Nene V, Khan B, Allsopp B A, Collins N E, Morzaria S P, Gobright E I, Bishop R P. Evidence for two single copy units in Theileria parva ribosomal RNA genes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;66:249–259. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Blancq S M, Khramtsov N V, Zamani F, Upton S J, Wu T W. Ribosomal RNA gene organization in Cryptosporidium parvum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;90:463–478. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long E G, White E H, Carmichael W W, Quinlisk P M, Raja R, Swisher B L, Daugharty H, Cohen M T. Morphologic and staining characteristics of a cyanobacterium-like organism associated with diarrhea. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:199–202. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez F A, Manglicmot J, Schmidt T M, Yeh C, Smith H V, Relman D A. Molecular characterization of Cyclospora-like organisms from baboons. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:670–676. doi: 10.1086/314645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madico G, McDonald J, Gilman R H, Cabrera L, Sterling C R. Epidemiology and treatment of Cyclospora cayetanensis infection in Peruvian children. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:977–981. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCutchan T F, Li J, McConkey G A, Rogers M J, Waters A P. The cytoplasmic ribosomal RNAs of Plasmodium spp. Parasitol Today. 1995;11:134–138. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(95)80132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortega Y R, Gilman R H, Sterling C R. A new coccidian parasite (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from humans. J Parasitol. 1994;80:625–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ortega Y R, Sterling C R, Gilman R H, Cama V A, Diaz F. Cyclospora species—a new protozoan pathogen of humans. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1308–1312. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305063281804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollok R C, Bendall R P, Moody A, Chiodini P L, Churchill D R. Traveller's diarrhoea associated with cyanobacterium-like bodies. Lancet. 1992;340:556–557. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91759-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Relman D A, Schmidt T M, Gajadhar A, Sogin M, Cross J, Yoder K, Sethabutr O, Echeverria P. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Cyclospora, the human intestinal pathogen, suggests that it is closely related to Eimeria species. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:440–445. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers M J, McConkey G A, Li J, McCutchan T F. The ribosomal DNA loci in Plasmodium falciparum accumulate mutations independently. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:881–891. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waters A P, Syin C, McCutchan T F. Developmental regulation of stage-specific ribosome populations in Plasmodium. Nature. 1989;342:438–440. doi: 10.1038/342438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]