Li et al. show that the transcriptional repressor DREAM regulates neutrophil adhesion and recruitment to sites of TNF-α–induced inflammation, providing a potential mechanism underlying heterogeneity in neutrophil function.

Abstract

Neutrophil functions and responses are heterogeneous, and the nature and categorization of this heterogeneity is achieving considerable interest. Work by Li et al. in this issue of JEM (2021. J. Exp. Med. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20211083) identifies how a transcriptional repressor, DREAM, regulates adhesion of neutrophils to endothelial cells and their transmigration into tissue. This study offers a mechanism for heterogeneity in this critical response of neutrophils to inflammatory stimuli.

Neutrophils develop primarily in the bone marrow. Once mature and released into the circulation, they patrol the vasculature looking for pathogens and other stimuli. Their circulating half-life in the absence of an encounter is short, less than 24 h. They undergo changes as they age in the circulation and in the tissue, which is one source of heterogeneity. The paradigm for neutrophil emigration from postcapillary venules includes selectin-mediated rolling, activation by locally produced chemokines and other mediators, adhesion to the endothelium, crawling to endothelial cell junctions (or a point in endothelial cells through which they can pass), and transmigration into tissue parenchyma (Sun et al., 2021). However, there are many exceptions to this paradigm. Neutrophil migration through the capillary bed of the lungs or through the sinusoids of the liver can occur through selectin-independent pathways that do not require rolling (Lee and Kubes, 2008; Doerschuk, 2001). Neutrophil adhesion and migration into the lungs can occur through either β2 integrin–independent or –dependent adhesion (Lee and Kubes, 2008; Doerschuk, 2001; Grönloh et al., 2021). For example, Streptococcus pneumoniae and N-formyl-l-methionyl-l-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) elicit neutrophil emigration that does not require β2, whereas Escherichia coli, TNF-α, and lipopolysaccharide induce emigration that is primarily β2 dependent (Doerschuk, 2001). Thus, heterogeneity in neutrophil responses also results from the particular stimulus and the microenvironment created by tissue structure and the response to the stimulus.

Insights from John C. Gomez and Claire M. Doerschuk.

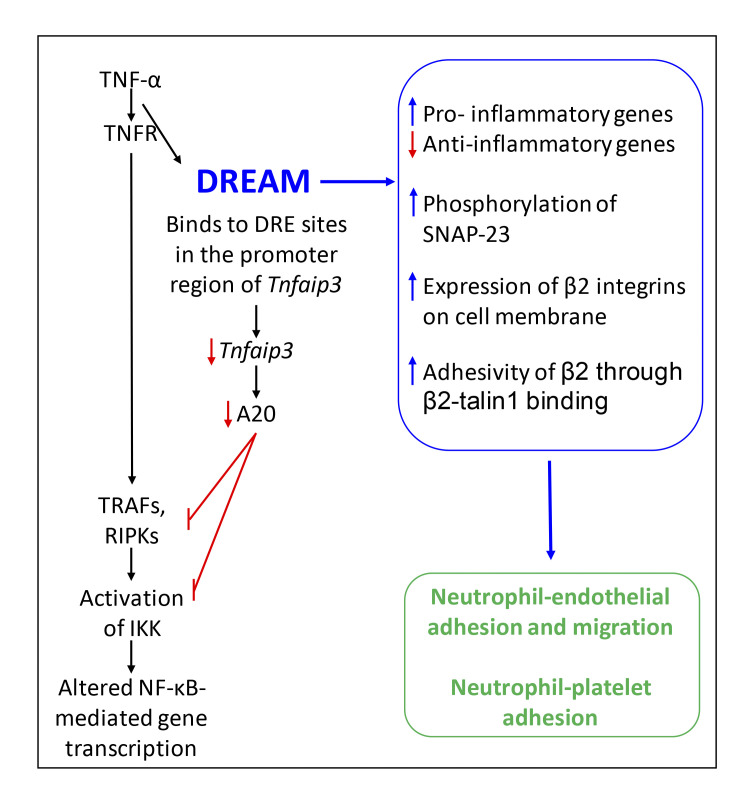

In this issue of JEM, Li et al. (2021) elegantly show that DREAM (downstream regulatory element antagonist modulator) is expressed by both endothelial cells and neutrophils and that DREAM regulates neutrophil adhesion, crawling, and transmigration (see figure). They use many approaches to evaluate these functions, and in each, neutrophil DREAM is required. Rolling is actually increased in the absence of DREAM, presumably because neutrophils are still attracted to the endothelium but cannot adhere. Most remarkably, neutrophil DREAM regulates changes in adhesion induced by TNF-α, but not by either MIP-2 (CXCL2) or fMLP, suggesting a mechanism for heterogeneity of neutrophil responses.

The functions of DREAM in neutrophils following exposure to TNF-α. TNF-α binds to its receptor, initiating binding of DREAM to the promoter region of the gene coding for A20. A20 expression is then less, resulting in less inhibition of TRAF/RIPK and IKK signaling. DREAM contributes to the functions shown in the blue box, resulting in enhanced neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells and to platelets.

The authors searched for the functions of DREAM in neutrophils. They found that DREAM transcriptionally enhances expression of many pro-inflammatory genes and suppresses anti-inflammatory genes, including Tnfaip3 that codes for the protein A20. Through binding to Tnfaip3’s promoter region (DRE1-2), DREAM suppresses expression of A20. A20 negatively regulates NF-κB through inhibition of the TRAFs and RIPKs downstream of TNF receptors and prevention of IKKβ phosphorylation. DREAM-deficient neutrophils have greater A20 expression, reduced IKKα/β phosphorylation, and impaired IκB degradation after TNF-α stimulation. Thus, in neutrophils, as in other cell types (Tiruppathi et al., 2014), DREAM functions to enhance activation of IKKβ and NF-κB.

Searching for DREAM’s mechanism of action in the process of adhesion and migration, the authors found that DREAM is important in both up-regulating the expression of the adhesion integrin, β2, on the neutrophil’s surface and activating β2 to become pro-adhesive in response to TNF-α, but not fMLP (Li et al., 2021). β2’s increased expression occurs through degranulation of specific and gelatinase granules (Sun et al., 2021). In the absence of DREAM, TNF-α–induced phosphorylation of SNAP-23, a member of the complex important in granule fusion to membranes, was less, and degranulation was partially prevented. The adhesivity of β2 requires interaction between the cytoplasmic tail of β2 and talin1, a protein that links membrane proteins to the cytoskeleton, and DREAM is required for this process. Outside–in signaling through β2 also requires DREAM for the generation of reactive oxygen species. Inhibition of IKKβ activation using TPCA-1 or Bay 11–7082 mimicked the effects of DREAM deficiency on both β2 expression and adhesivity, suggesting that IKKβ may again be in this DREAM pathway. The investigators suggest that IKKβ may be regulating SNAP-23 phosphorylation.

Furthermore, DREAM was also required in both neutrophils and platelets for neutrophil–platelet adhesion and aggregation during TNF-α–induced vascular inflammation (Li et al., 2021). Importantly, when mice with sickle cell disease and deficiency of DREAM were challenged with TNF-α, platelet–neutrophil interactions in lung microvessels were inhibited, blood flow was higher, and there was a small improvement in survival compared with mice with DREAM, suggesting that DREAM was required for full manifestation of vaso-occlusive events.

This paper makes major inroads into understanding the function of DREAM in neutrophils and to our understanding of the signaling mechanisms through which important neutrophil functions occur. As with all exciting studies, their observations bring new questions. An important one asks how IKKβ acts to mediate the effects of DREAM, particularly when NF-κB–mediated gene expression is unlikely to be required, for example, in the movement of β2 from granules to the neutrophil surface and the increase in β2 adhesivity (Sun et al., 2021). First, one must think carefully about the use of soluble IKK inhibitors to identify critical functions, which often requires confirmation through other approaches when possible. Second, when the effect of two interventions, DREAM knockout/knockdown and inhibitor-induced IKK inhibition, produces the same effect and are not additive, it is tempting to conclude that they are in the same pathway, which is not necessarily true. These observations raise a third point: how is IKKβ acting in these two events? The authors provide evidence that IKKβ phosphorylates SNAP-23, but its actions in both this process and in regulating β2 adhesivity remain critical questions.

A second question arising from this work is, how is DREAM activated? The concentration of Ca2+ is an important regulator, but other signals are likely important. The observation that TNF-α, but not fMLP or MIP-2, results in DREAM-mediated suppression of A20 may provide a clue. How the gene coding for DREAM is regulated in neutrophils is also an interesting question. Expression of mRNA for this gene is not changed during S. pneumoniae pneumonia at 24 h (Gomez et al., 2017). Finally, whether DREAM is acting in ways other than through suppression of A20 expression is a critical question. Other signaling molecules suggested to be regulated by DREAM include MAP kinases and class 1β phosphoinositide 3-kinase (Tiruppathi et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2017), but whether directly and through what pathways is not clear.

Third, the observation that the DREAM-induced changes in pro- and anti-inflammatory genes lasted less than 2 h suggests that turning off DREAM may be part of the process of resolution. Neutrophils are beneficial and required for host defense but also can induce parenchymal cell injury. Perhaps turning off DREAM may be a means of preventing the injury that can accompany neutrophil function. The fact that A20 expression remained elevated for 3 h after TNF-α suggests that the effects of DREAM may last longer than suggested by gene expression but may nevertheless be important in quieting neutrophils. The mechanism through which DREAM is turned off also remains an important question. Whether DREAM facilitates or delays aging of neutrophils is also an interesting question, particularly since aging is a source of heterogeneity in neutrophil function.

A fourth exciting question relates to the difference in signaling induced by TNF-α receptors compared with that initiated by either fMLP receptors or MIP-2 receptors (and CXCR2). TNFR1 and R2 are members of the TNFR superfamily, whereas fMLP receptors, CXCR1, and R2 are members of the G protein–coupled receptor family, which initiate quite different signaling pathways, including phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase-γ (PI3Kγ)/Akt, MAP kinases, or phospholipase-β (PLCβ) signaling pathways (Waters et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2017; Rajarathnam et al., 2019). The work by Li et al. (2021) indicates that DREAM acts quite differently when cell signaling is initiated by TNF receptors compared with fMLP or MIP-2 receptors. Understanding how these signaling pathways result in such different roles for DREAM will inform our understanding of neutrophil biology and the basis for heterogeneity in neutrophil responses.

Finally, although the authors present an interesting model of pulmonary intravascular inflammation, the function of neutrophil DREAM in neutrophil transmigration into alveoli induced by pathogens may provide additional insight into neutrophil heterogeneity. For example, one focused study might test the functions of DREAM in neutrophil recruitment to S. pneumoniae or E. coli, stimuli that induce β2-independent and β2-dependent adhesion and migration, respectively. Interestingly, neutrophils isolated from S. pneumoniae pneumonias express sixfold more Tnfaip3 mRNA (coding for A20) than neutrophils from uninfected lungs (Gomez et al., 2017). The expression of Tnfaip3 in neutrophils of DREAM-deficient mice may be exciting to pursue, as well as other neutrophil functions. Importantly, numerous inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and other mediators are expressed within an inflammatory site, including both TNF-α and MIP-2. The function of DREAM may depend on which mediator(s) an individual neutrophil encounters as it travels from capillary to alveoli. The microenvironment may thus contribute to the transcriptomic and proteomic profile of a neutrophil, including the expression of Tnfaip3 and A20, and the heterogeneity of neutrophil responses.

Therapeutic intervention to modify DREAM or A20 may result in beneficial alterations in inflammatory process. Whether inhibition or augmentation of DREAM is beneficial is likely to depend on the disease process. Sickle cell disease may benefit from inhibition of DREAM or augmentation of A20. Alternatively, inhibition of A20 may be beneficial acutely during pneumonia or other infections. Enhancing the resolution and repair of inflamed tissue may require the opposite intervention. Lessons may be learned from the numerous trials of IKK inhibitors and other modulators of the NF-κB pathway (Ramadass et al., 2020; https://clinicaltrials.gov).

Thus, these investigators are commended for their detailed and thoughtful studies of neutrophil functions and their mechanisms and for their focus on DREAM. Their work provides important insights into neutrophil biology and leads to critically important new questions.

References

- Chen, K., et al. 2017. J. Autoimmun. 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerschuk, C.M. 2001. Microcirculation. 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2001.tb00159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, J.C., et al. 2017. Sci. Rep. 10.1038/s41598-017-11638-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grönloh, M.L.B., et al. 2021. J. Cell Sci. 10.1242/jcs.255653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K., et al. 2017. Blood. 10.1182/blood-2016-07-724419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.Y., and Kubes P.. 2008. J. Hepatol. 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., et al. 2021. J. Exp. Med. 10.1084/jem.20211083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajarathnam, K., et al. 2019. Cell. Signal. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadass, V., et al. 2020. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 10.3390/ijms21145164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H., et al. 2021. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 10.1152/ajpcell.00560.2020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiruppathi, C., et al. 2014. Nat. Immunol. 10.1038/ni.2823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters, J.P., et al. 2013. J. Pathol. 10.1002/path.4187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]