Abstract

Purpose:

Energy and fatigue are thought to improve after bariatric surgery. Such improvements could be related to weight loss and/or increased engagement in day-to-day health behaviors, such as moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA). This study used ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to evaluate several aspects of energy/fatigue in real-time in patients’ natural environment during the first year after surgery and assessed the associations of percent total weight loss (%TWL) and daily MVPA with daily energy/fatigue levels.

Methods:

Patients (n=71) undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy rated their energy, alertness and attentiveness (averaged to create an “attentiveness” rating), and tiredness and sleepiness (averaged to create a “fatigue” rating) via smartphone-based EMA at 4 semi-random times daily for 10 days at pre-surgery and 3-, 6-, and 12-mos. post-surgery. Daily MVPA minutes were assessed via accelerometry. Weight was measured in clinic.

Results:

Energy ratings initially increased from pre- to post-surgery, before leveling off/decreasing by 12-month (p<.001). Attentiveness and fatigue ratings did not change over time. %TWL was unrelated to any ratings, while MVPA related to both energy and attentiveness but not fatigue. Participants reported more energy on days with more total MVPA min (p=.03) and greater attentiveness on days with more total (p<.001) and bouted (p=.02) MVPA.

Conclusion:

While more research is needed to confirm causality, results suggest greater daily MVPA is associated with increased daily energy and attentiveness among bariatric surgery patients, independent of %TWL. Findings add to growing evidence of MVPA’s potential benefits beyond energy expenditure in the context of bariatric surgery.

Energy and fatigue are key aspects of vitality, defined as physical or mental vigor and stamina [1]. Vitality is an important concept that reflects both physical and mental components of health and is commonly measured in health-related quality of life surveys [2,3].

Low energy and fatigue are frequently reported among patients with chronic diseases including obesity [4]. Patients undergoing bariatric surgery consistently report fatigue and low energy levels [5–7]. Patients report improved energy/fatigue levels post-surgery; one meta-analysis found that patients who had surgery reported greater long-term improvements in energy/fatigue compared to controls who did not have surgery [8,9]. However, a limitation of past research on energy/fatigue in this population is reliance on retrospective questionnaires (e.g., the Vitality domain of the 36-item Short Form Survey [SF-36] [2]). These measures are prone to multiple recall biases [10,11] and cannot provide information on energy/fatigue levels from day-to-day nor associations with important lifestyle factors that may influence these levels, such as daily physical activity (PA).

Additionally, while previous research has associated post-surgical improvements in energy/fatigue with percent total weight loss (%TWL) and PA, understanding of the relative importance of each is lacking. Some studies have observed a positive relationship between %TWL and increased energy/decreased fatigue [12,13], while others have not shown this relationship [9,14,15]. Regarding PA, greater improvements in energy/fatigue have been observed among surgery patients with higher moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA (MVPA) levels across several samples [16–19], and a recent study of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) patients showed greater MVPA related to better mental health-related quality of life, which included ratings of energy/fatigue, independent of %TWL [20]. Additionally, the broader PA literature shows positive effects of MVPA on energy/fatigue [21–24]. Evaluating the associations of day-to-day perceived energy/fatigue with both %TWL and daily MVPA among bariatric surgery patients can help to elucidate the extent to which reductions in excess weight versus lifestyle factors like MVPA relate to changes in energy/fatigue. This has potentially important clinical implications. For example, if greater MVPA relates to improved energy/fatigue independent of %TWL, informing patients of this may help increase motivation to engage in regular MVPA to achieve these benefits. Improvements in energy/fatigue could, in turn, reinforce long-term adherence to MVPA and other weight management behaviors [25].

The present study aimed to evaluate: (1) changes in energy/fatigue during the first year after bariatric surgery; (2) associations of %TWL with energy/fatigue, and (3) associations of daily MVPA with energy/fatigue, controlling for %TWL. Advancing prior research, we used smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment (EMA) and accelerometry in combination to: (1) assess several aspects of energy/fatigue (i.e., feeling energetic, attentive and alert, sleepy and tired) multiple times per day in participants’ natural environments, and (2) evaluate associations of MVPA with energy/fatigue ratings at the daily level at pre-surgery and 3-, 6-, and 12-months post-surgery. We hypothesized that energy/fatigue would improve post-surgery; greater %TWL would relate to greater improvements in energy/fatigue; and daily MVPA would be significantly associated with daily energy/fatigue ratings, such that participants would report more favorable energy/fatigue levels on days they performed more MVPA.

Methods

Participants.

The present study is a secondary analysis of data collected for a prospective cohort study that sought to evaluate psychosocial and behavioral predictors of surgical outcomes [26]. Inclusion criteria for the parent study were as follows: 18 years old, body mass index (BMI) of 35.0 kg/m2, and being scheduled to undergo RYGB or sleeve gastrectomy at one of two academic medical center-affiliated bariatric surgery centers in the Northeastern U.S. Patients were excluded if they were receiving weight management intervention outside the scope of standard surgical care or endorsed presence of a situation/condition (e.g., plans to move) that could interfere with protocol adherence.

Procedure.

The parent study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Miriam Hospital and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and was registered at clinicaltrials.gov. Study protocol details are available in Goldstein et al. [26]. Recruitment occurred between May 2016 and April 2018. Clinic staff provided patients with a recruitment brochure at a regularly scheduled clinic visit 3 to 8 weeks pre-surgery. Interested participants provided their contact information to clinic staff and were contacted by the research team to complete an initial phone screen of eligibility. Those appearing eligible then completed an in-person eligibility/baseline visit at the clinic or research center during which they provided informed consent, had their height and weight measured, completed questionnaires, and were provided devices and training to complete the MVPA and EMA assessment protocols.

For MVPA assessment, participants were provided with a wrist-worn accelerometer to wear 24 hours/day for 10 days. They were also given a smartphone (Samsung Galaxy S7; Samsung Electronics, South Korea) equipped with an EMA app (PiLR HealthTM; MEI Research, Ltd, Edina, MN) to complete 10 days of EMA. For the EMA, participants received four semi-random prompts daily assessing energy/fatigue. Prompts were randomly dispersed around anchors of 11:00am, 2:00pm, 5:00pm, and 8:00pm. However, as part of the parent study’s protocol, participants also received an EMA survey with questions specific to their exercise (e.g., location) when the accelerometer detected sustained MVPA. To reduce burden, if participants received an MVPA-prompted EMA survey within 2 hours of a scheduled prompt, energy/fatigue questions were administered at that time. Participants could view their EMA survey adherence and earned compensation in real time on the smartphone. While all participants were asked to wear the accelerometer and complete EMA for 10 days, participants were allowed to proactively extend the EMA/accelerometry assessment period or to make up wear/survey days if they experienced adherence difficulties to ensure at least 10 days with adequate compliance. Participants were compensated $75 for completing the baseline assessment, plus $0.50 per completed EMA survey. These procedures were repeated at 3-, 6-, and 12-months post-surgery.

Measures.

EMA.

Energy/fatigue was assessed at each of the four daily EMA surveys using 5 items from the PANAS-X [27]. Participants rated how energetic (from the joviality scale of the PANAS-X), attentive and alert (from the attentiveness scale), and sleepy and tired (from the fatigue scale) they felt from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). We included attentive and alert ratings given that past research [6] has included mental/cognitive dimensions in fatigue measures (e.g., the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory [28]). Based on each item’s assigned subscale on the PANAS-X, theoretical similarities between the attentive/alert and sleepy/tired items, and confirmation of similar trajectories in change for attentive/alert and sleepy/tired items through visual graphing of means, we averaged the attentive and alert (Cronbach’s α = 0.82) and sleepy and tired (Cronbach’s α = 0.91) responses at the survey level, resulting in three energy/fatigue variables per EMA survey: (1) Energy, (2) Attentiveness, and (3) Fatigue. Survey responses were then averaged within-day to create daily Energy, Attentiveness, and Fatigue variables.

MVPA.

MVPA was assessed with an ActiGraph GT9X Link wrist-worn accelerometer (ActiGraph, LLC, Pensacola, FL). Non-wear time (defined as ≥90 min. without movement using vector magnitude counts, with allowance of interruptions of up to 2 min. of non-zero counts) and sleep time were determined using validated algorithms in ActiLife and were removed [29, 30]. At least 10 hours of valid wear was required for a valid wear day. Minutes of MVPA were determined by classifying 60-second epochs using cutpoints previously shown to minimize the differences in MVPA estimates between wrist- and hip-worn ActiGraph devices (≥7,500 vector magnitude counts/min) [31, 32]. Bouted daily MVPA was determined by summing all MVPA accrued in 10 consecutive minutes with a 2-minute drop allowance per day. Total daily MVPA was determined by summing all MVPA minutes (bouted and unbouted) per day.

%TWL and Sociodemographic Characteristics.

At each assessment, participants’ weight was measured (to the nearest 0.1 kg) by research staff in clinic using a calibrated digital scale. %TWL was calculated at each assessment point as follows: ([baseline weight – follow-up weight (i.e., 3-, 6-, or 12-month weight)] baseline weight) * 100%. Participants self-reported their age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Statistical Approach.

Prior to analyses, data were screened to ensure sufficient availability for analyses. Participants were required to have 10 EMA responses for each energy/fatigue variable [33] and 4 days of valid Actigraphy data for their data to be included in the analysis from any given assessment period. Participants were also required to complete the baseline self-report questionnaires for inclusion of demographic covariates in all models. All analyses were conducted in R v. 3.6.0. [34] Baseline participant characteristics and EMA/accelerometry compliance were examined using the mean, standard deviation, and skewness/kurtosis for continuous variables, and counts/percentages for categorical variables. Each of the three outcomes/dependent variables (i.e., Energy, Attentiveness, and Fatigue) were modeled separately in a series of 2-level mixed effects linear models, with day-level mean EMA ratings (level 1) nested within participants (level 2) over time, using the lme4 package [35]. To model change in each outcome variable over time (Aim 1), fixed linear and quadratic effects of time (months since surgery) on outcome were evaluated using the Satterthwaite formula and the lmerTest package [36]. Random intercepts were included in all models, and random linear slopes were included if they significantly improved model fit per maximum likelihood ratio test results. Covariates of age, sex, and identification with a racial/ethnic minority group were included in each model. To evaluate the association of %TWL with each energy/fatigue outcome (Aim 2), we then added %TWL to each model. Next, to evaluate the association of total MVPA with each energy/fatigue outcome when controlling for %TWL (Aim 3), we added total daily MVPA minutes to each model. We also added accelerometer wear time as a covariate. Lastly, to evaluate the association of bouted MVPA with each energy/fatigue outcome (Aim 3), we removed total daily MVPA minutes from the model and added bouted daily MVPA minutes as a predictor.

Results

Enrollment, EMA and Accelerometry Adherence, and Participant Characteristics.

Of 170 participants screened, 92 consented, 77 completed the baseline assessment, and 71 had surgery and provided sufficient EMA and actigraphy data for analysis at baseline. The number of participants providing sufficient data for inclusion in analysis at follow-up visits was: 59 (83%) at 3-months, 51 (72%) at 6-months, and 46 (65%) at 12-months. The average number of EMA ratings provided per energy/fatigue variable was as follows: 36.4 (SD=15.0) at baseline, 38.6 (SD=16.6) at 3-months, 41.5 (SD=14.4) at 6-months, and 38.6 (14.6) at 12-months. Participants had an average of 11.7 (SD=1.8) valid days of accelerometer wear time at baseline, 12.4 (SD=3.2) at 3-months, 12.7 (SD=3.0) at 6-months, and 11.8 (SD=2.0) at 12-months. Most participants were female (90%). Approximately half (48%) self-identified with a racial or ethnic minority group. The average pre-surgical BMI was 45.9 kg/m2 (SD=7.0) and the average %TWL at 12 months was 27.6% (SD=8.2).

Energy/Fatigue Over Time.

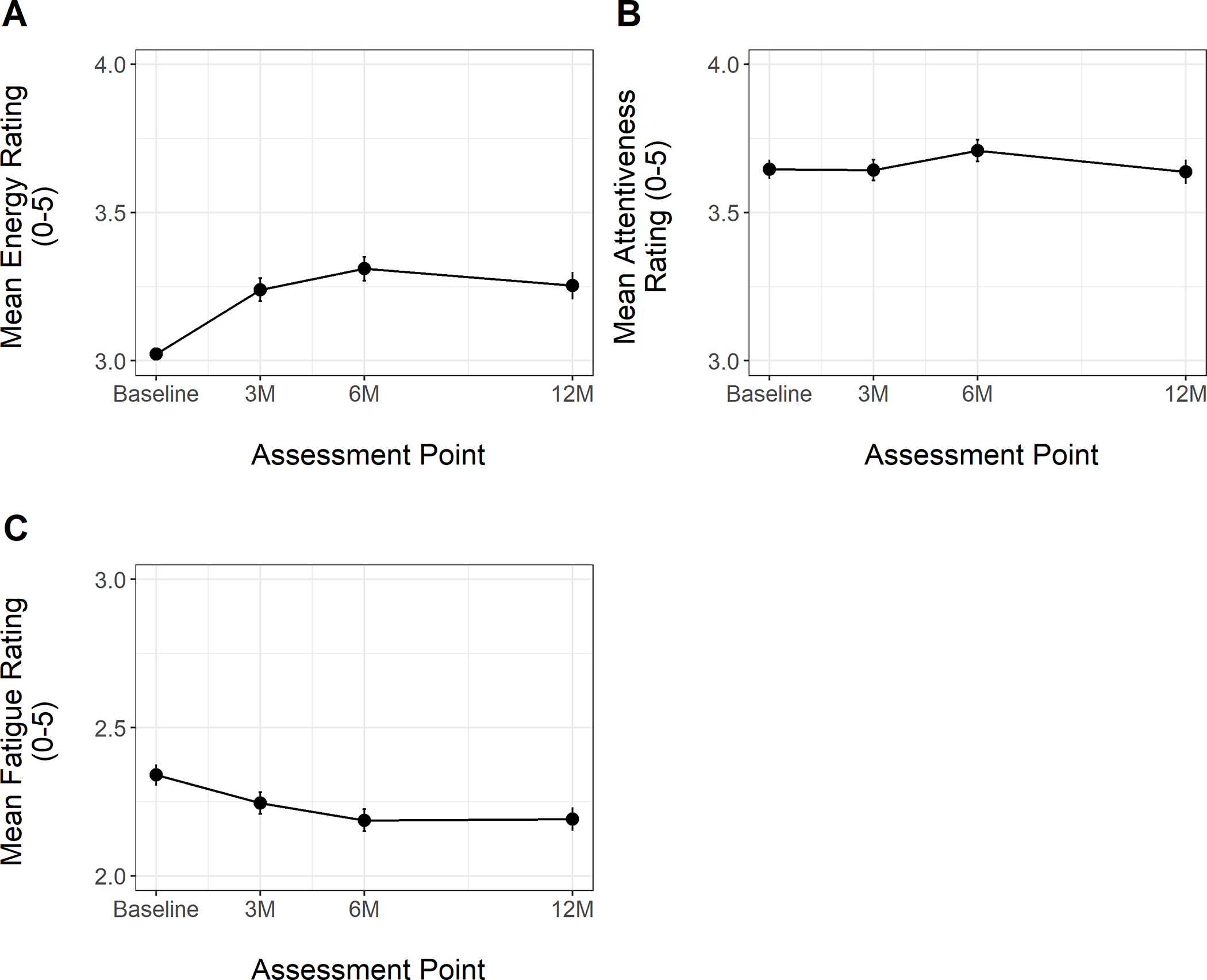

Figure 1 depicts mean ratings of the three outcome variables of interest from baseline to 12-months. Parameter estimates for linear mixed effects models are shown in Tables 1, 2, and 3, for Energy, Attentiveness, and Fatigue, respectively. For Energy, results from the base longitudinal model revealed significant linear and quadratic fixed effects of time on ratings, indicating that energy increased initially post-surgery, and the rate of change slowed over time (Table 1). Results for the Attentiveness model indicated no significant effect of time on the outcome (Table 2). Thus, on average, participant ratings of Attentiveness remained stable from pre- to 12-months post-surgery. A similar pattern was observed for Fatigue, with no significant fixed effect of time on outcome (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Energy, Attentiveness, and Fatigue Ratings from Baseline (Pre-Surgery) to 12-Month Post-Surgery Assessment

Table 1.

Fixed Parameter Estimates for Prediction of Energy Ratings Post-Bariatric Surgery

| Model 1: Effect of Time on Energy B (SE) |

Model 2: Effect of %TWL on Energy B (SE) |

Model 3: Effect of Total MVPA on Energy B (SE) |

Model 4: Effect of Bouted MVPA on Energy B (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept± | 2.489 (0.459)*** | 2.541 (0.460)*** | 2.386 (0.468)*** | 2.464 (0.490)*** |

| Linear Time (Months)± | 0.068 (0.011)*** | 0.101 (0.036)** | 0.114 (0.038)*** | 0.113 (0.027)*** |

| Quadratic Time (Months) | −0.005 (0.0008)*** | −0.006 (0.002)** | −0.007 (0.002)*** | −0.007 (0.002)*** |

| Sexϕ | −0.076 (0.286) | −0.109 (0.287) | −0.120 (0.288) | −0.152 (.301) |

| Age | 0.018 (0.008)* | 0.018 (0.008)* | 0.019 (0.008)* | −0.018 (0.008)* |

| Race/Ethnicity¥ | −0.494 (0.175)** | −0.492 (0.175)** | −0.476 (0.176)** | −0.467 (0.184)* |

| Wear Time | -- | -- | 0.00008 (0.0008) | 0.00009 (0.00008) |

| %TWL ^ | -- | 0.004 (0.006) | .006 (.006) | .006 (.004) |

| MVPA^ | -- | -- | 0.001 (0.0004)* | -- |

| Bouted MVPA^ | -- | -- | -- | 0.0003 (0.0006) |

Note:

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Entered as fixed and random effect in the model, with slope and intercept uncorrelated to facilitate convergence

Non-White is reference

Male is reference

Time-varying covariate; ICC null model = 0.61

Table 2.

Fixed Parameter Estimates for Prediction of Attentiveness Ratings Post-Bariatric Surgery

| Model 1: Effect of Time on Attentiveness B (SE) |

Model 2: Effect of %TWL on Attentiveness B (SE) |

Model 3: Effect of Total MVPA on Attentiveness B (SE) |

Model 4: Effect of Bouted MVPA on Attentiveness B (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept± | 3.150 (0.490)*** | 3.198 (0.500)*** | 3.102 (0.495)*** | 3.094 (0.497)*** |

| Linear Time (Months)± | −0.007 (0.007) | −0.003 (0.004) | 0.001 (0.009) | 0.002 (0.009) |

| Sexϕ | −0.173 (0.306) | −0.196 (0.312) | −0.153 (0.307) | −0.105 (0.307) |

| Age | 0.016 (0.008) | 0.016 (0.009) | 0.015 (0.008) | 0.014 (0.008) |

| Race/Ethnicity¥ | −0.211 (0.187) | −0.249 (0.191) | −0.192 (0.188) | −0.181 (0.188) |

| Wear Time | -- | -- | 0.0000003 (0.00007) | 0.00005 (0.00007) |

| %TWL | -- | 0.001 (0.002) | .003 (.002) | .003 (.002) |

| MVPA | -- | -- | 0.002 (0.0004)*** | -- |

| Bouted MVPA | -- | -- | -- | 0.001 (0.0005)* |

Note:

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Entered as fixed and random effect in the model

Non-White is reference; ϕMale is reference

Time-varying covariate; ICC null model = 0.71

Table 3.

Fixed Parameter Estimates for Prediction of Fatigue Ratings Post-Bariatric Surgery

| Model 1: Effect of Time on Fatigue B (SE) |

Model 2: Effect of %TWL on Fatigue B (SE) |

Model 3: Effect of Total MVPA on Fatigue B (SE) |

Model 4: Effect of Bouted MVPA on Fatigue B (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept± | 2.339 (0.442)** | 2.339 (0.442)** | 2.511 (0.453)*** | 2.518 (0.452)*** |

| Linear Time (Months) | − 0.003 (0.004) | 0.004 (0.007) | 0.004 (0.007) | 0.005 (0.007) |

| Sexϕ | 0.166 (0.276) | 0.164 (0.276) | 0.186 (0.276) | 0.171 (0.275) |

| Age | −0.004 (0.008) | −0.005 (0.008) | −0.005 (0.008) | −0.004 (0.008) |

| Race/Ethnicity¥ | 0.119 (0.169) | 0.134 (0.169) | 0.102 (0.169) | 0.106 (0.168) |

| Wear Time | -- | -- | −0.0001 (0.0001) | −0.0002 (0.0001) |

| %TWL | -- | 0.003 (0.003) | .003 (.003) | .004 (.003) |

| MVPA | -- | -- | −0.0006 (0.0005) | -- |

| Bouted MVPA | -- | -- | -- | 0.0008 (0.0007) |

Note:

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Entered as fixed and random effect in the model

Non-White is reference

Male is reference

Time-varying covariate; ICC null model = 0.46

Effects of %TWL and MVPA on Energy/Fatigue Ratings.

%TWL was not significantly associated with any of the outcome variables of interest. In the model evaluating Energy over time, a significant time-varying effect of total MVPA indicated that participants tended to report higher energy on days when they engaged in more overall MVPA. No significant effect was detected for bouted MVPA. For Attentiveness, significant effects were detected for both total and bouted MVPA, indicating that participants reported greater feelings of attentiveness on days they engaged in more MVPA, regardless of the duration of each MVPA episode. No significant association was present between bouted or total MVPA and Fatigue.

Discussion

Previous research indicates that energy/fatigue levels tend to improve after bariatric surgery. However, because previous studies have relied on retrospective questionnaires, understanding of energy/fatigue levels day-to-day and associations with lifestyle behaviors (i.e., MVPA) is lacking. We thus used smartphone EMA and accelerometry in combination to assess pre- to post-surgery energy/fatigue and associations with %TWL and daily MVPA levels. Overall, results showed that energy increased in the initial months after surgery before leveling off, while attentiveness and fatigue on average did not change. Importantly, MVPA, but not %TWL, related to energy/fatigue levels. Specifically, participants reported greater energy on days with more total MVPA and greater attentiveness on days with more total and bouted MVPA.

Our finding that energy improved after surgery is consistent with several prior studies observing increased vitality after surgery [8]. This study also extends prior work by using EMA to evaluate changes in energy and fatigue separately and in daily life. While measures like the SF-36 combine ratings of energy and fatigue, some research suggests energy and fatigue are actually independent unipolar states with unique underlying biological mechanisms, rather than being opposite ends of a single continuum [37]. When assessed separately, several studies, especially those looking at the associations between changes in lifestyle factors like PA and energy/fatigue, have commonly observed changes in energy but not fatigue, which is consistent with our findings [37]. Although some prior studies have shown improvements in attention and other aspects of mental/cognitive functioning after surgery [38,39], participants in the current study on average did not report improvements in attentiveness post-surgery. One possible explanation for this is that our items tapped into different constructs than those assessed in past research (e.g., our study assessed perceived attentiveness vs. attention as measured via cognitive functioning batteries). Additional research evaluating distinct physical and psychological aspects of energy/fatigue after surgery using multiple methods of assessment is warranted.

While we did not observe improvements in attentiveness overall, participants did report higher levels of both attentiveness and energy on days they performed more MVPA. By contrast, %TWL did not relate to energy/fatigue levels. These findings align with recent work showing that MVPA but not %TWL related to mental aspects of health-related quality of life (including vitality) among patients receiving RYGB [20], as well as experimental work from the exercise literature showing that bouts of exercise improve energy but not fatigue [22]. While we cannot draw causal conclusions given our study’s design, MVPA could potentially provide a boost in energy and attentiveness, as demonstrated in prior work [22,40]. If confirmed in future research, stronger effects of MVPA on energy and attentiveness than fatigue may be at least partially due to biological mechanisms; for example, exercise triggers an increase in dopamine [41], and dopamine affects cognitive functioning [41] and appears to influence energy more strongly than fatigue [37]. Conversely, it is possible that participants opted to engage in more MVPA when feeling more energetic and attentive. Our finding that total MVPA, not just that accumulated in sustained bouts, relates to energy and attentiveness is also consistent with the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, which emphasize that MVPA bouts of any length can provide benefits [42].

Strengths of the current study include evaluation of day-to-day associations between energy/fatigue and MVPA, use of EMA and accelerometers to measure outcomes of interest, and assessment across four timepoints from pre- to 12 months post-surgery. Limitations include a predominantly female sample, inability to determine the directionality of MVPA’s association with energy/fatigue, and use of a fairly rigorous protocol for the parent study, which may have resulted in selection of participants with certain characteristics (e.g., high motivation or energy levels) that might limit generalizability to the wider bariatric population. Generalizability is also limited by participant attrition over time. While this concern is partially offset by use of modeling approaches that made use of all available data, additional research is needed to develop and test new strategies to improve adherence in bariatric studies, especially those involving intensive daily measurement protocols. There are also other factors, such as improvement in sleep apnea [43], that could affect energy/fatigue that were not accounted for in the models and should be considered in future work. Future studies should also assess changes in energy/fatigue and their associations with both MVPA and %TWL: (1) for longer follow-up periods, and (2) among individuals receiving additional types of bariatric surgery (e.g., mini-gastric bypass).

In conclusion, this study suggests that daily energy increases on average after surgery and that energy and attentiveness are greater on days when individuals report more MVPA, independent of %TWL. While replication with larger samples and analyses on a finer time scale are needed to confirm findings and determine causality, results suggest that improvements in daily energy levels may be yet another positive consequence of bariatric surgery [44] and that MVPA may play an important role in improving energy and attentiveness among bariatric surgery patients. If the latter is confirmed, this finding could serve as a valuable clinical tool to increase motivation for engaging in regular MVPA. This in turn could create a positive feedback loop by which increased MVPA levels contributes to increased energy, and increased energy reinforces long-term adherence to MVPA and enhanced weight management.

Key Points.

Energy increased after surgery while attentiveness and fatigue did not improve

Patients reported more energy on days they accrued more total MVPA minutes

Patients reported greater attentiveness on days with more total and bouted MVPA

Percent total weight loss was unrelated to perceived energy, attentiveness, and fatigue

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to acknowledge Jennifer Webster (BA) for her assistance in conducting the study. We would also like to thank all study participants.

Grant support: This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK108579; principal investigators: Dale S. Bond & J. Graham Thomas) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (T32 HL076134; principal investigator: Rena Wing; recipients: Leah Schumacher and Hallie Espel-Huynh).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Drs. Schumacher, Espel-Huynh, Thomas, Vithiananthan, Jones, and Bond have received grant funding from the NIH. Dr. Thomas reports board membership, consultancy, and stock ownership for Lumme Heatlh Inc.

Ethics Statement: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Lavrusheva O The concept of vitality. Review of the vitality-related research domain. New Ideas Psychol. 2020;56:100752. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swain MG. Fatigue in chronic disease. Clin Sci. 2000;99(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Nunen AM, Wouters EJ, Vingerhoets AJ, Hox JJ, Geenen R. The health-related quality of life of obese persons seeking or not seeking surgical or non-surgical treatment: A meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2007;17(10):1357–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gletsu-Miller N, Shevni N, Manatunga A, Lin E, Musselman D. A multidimensional analysis of the longitudinal effects of roux en y gastric bypass on fatigue: An association with visceral obesity. Physiol Behav. 2019;209:112612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anandacoomarasamy A, Caterson ID, Leibman S, Smith GS, Sambrook PN, Fransen M, et al. Influence of BMI on health-related quality of life: Comparison between an obese adult cohort and age-matched population norms. Obesity. 2009;17(11):2114–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driscoll S, Gregory DM, Fardy JM, Twells LK. Long-term health-related quality of life in bariatric surgery patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity. 2016;24(1):60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolotkin RL, Andersen JR. A systematic review of reviews: Exploring the relationship between obesity, weight loss and health-related quality of life. Clin Obes. 2017;7(5):273–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmier JK, Halpern MT. Patient recall and recall bias of health state and health status. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2004;4(2):159–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smyth JM, Stone AA. Ecological momentary assessment research in behavioral medicine. J Happiness Stud. 2003;4(1):35–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Moore RH, Eisenberg MH, Raper SE, Williams NN. Changes in quality of life and body image after gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(6):608–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swencionis C, Wylie-Rosett J, Lent MR, Ginsberg M, Cimino C, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. Weight change, psychological well-being, and vitality in adults participating in a cognitive–behavioral weight loss program. Health Psychol. 2013;32(4):439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strain G, Kolotkin R, Dakin G, Gagner M, Inabnet W, Christos P, et al. The effects of weight loss after bariatric surgery on health-related quality of life and depression. Nutr Diabetes. 2014;4(9):e132–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroes M, Osei-Assibey G, Baker-Searle R, Huang J. Impact of weight change on quality of life in adults with overweight/obesity in the United States: A systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(3):485–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nuijten MA, Tettero OM, Wolf RJ, Bakker EA, Eijsvogels TM, Monpellier VM, et al. Changes in physical activity in relation to body composition, fitness and quality of life after primary bariatric surgery: A two-year follow-up study. Obes Surg. 2021;31(3):1120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sellberg F, Possmark S, Willmer M, Tynelius P, Persson M, Berglind D. Meeting physical activity recommendations is associated with health-related quality of life in women before and after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(6):1497–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bond DS, Thomas JG, King WC, Vithiananthan S, Trautvetter J, Unick JL, et al. Exercise improves quality of life in bariatric surgery candidates: Results from the Bari-Active trial. Obesity. 2015;23(3):536–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bond DS, Phelan S, Wolfe LG, Evans RK, Meador JG, Kellum JM, et al. Becoming physically active after bariatric surgery is associated with improved weight loss and health-related quality of life. Obesity. 2009;17(1):78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King WC, Hinerman AS, White GE, Courcoulas AP, Belle SH. Associations between physical activity and changes in depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life across 7 years following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: A multicenter prospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2021. Advanced online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puetz TW, O’Connor PJ, Dishman RK. Effects of chronic exercise on feelings of energy and fatigue: a quantitative synthesis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(6):866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loy BD, O’Connor PJ, Dishman RK. The effect of a single bout of exercise on energy and fatigue states: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fatigue. 2013;1(4):223–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bize R, Johnson JA, Plotnikoff RC. Physical activity level and health-related quality of life in the general adult population: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45(6):401–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dennett AM, Peiris CL, Shields N, Prendergast LA, Taylor NF. Moderate-intensity exercise reduces fatigue and improves mobility in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-regression. J Physiother. 2016;62(2):68–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitzpatrick SL, Appel LJ, Bray B, Brooks N, Stevens VJ. Predictors of long-term adherence to multiple health behavior recommendations for weight management. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(6):997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldstein SP, Thomas JG, Vithiananthan S, Blackburn GA, Jones DB, Webster J, et al. Multi-sensor ecological momentary assessment of behavioral and psychosocial predictors of weight loss following bariatric surgery: study protocol for a multicenter prospective longitudinal evaluation. BMC Obesity. 2018;5(1):1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form. 1994. University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smets E, Garssen B, Bonke Bd, De Haes J. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):315–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole RJ, Kripke DF, Gruen W, Mullaney DJ, Gillin JC. Automatic sleep/wake identification from wrist activity. Sleep. 1992;15(5):461–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tudor-Locke C, Barreira TV, Schuna JM Jr, Mire EF, Katzmarzyk PT. Fully automated waist-worn accelerometer algorithm for detecting children’s sleep-period time separate from 24-h physical activity or sedentary behaviors. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;39(1):53–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamada M, Shiroma EJ, Harris TB, Lee I-M. Comparison of physical activity assessed using hip-and wrist-worn accelerometers. Gait Posture. 2016;44:23–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wennman H, Pietilä A, Rissanen H, Valkeinen H, Partonen T, Mäki-Opas T, et al. Gender, age and socioeconomic variation in 24-hour physical activity by wrist-worn accelerometers: The FinHealth 2017 Survey. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bond DS, Thomas JG, Jones DB, Schumacher LM, Webster J, Evans EW, et al. Ecological momentary assessment of gastrointestinal symptoms and risky eating behaviors in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17(3):475–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 3.6.0 ed. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. 1.1–7 ed2015. p. R package. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. lmerTest: tests in linear mixed effects models. R package version 2.0–20. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loy BD, Cameron MH, O’Connor PJ. Perceived fatigue and energy are independent unipolar states: Supporting evidence. Med Hypotheses. 2018;113:46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alosco ML, Galioto R, Spitznagel MB, Strain G, Devlin M, Cohen R, et al. Cognitive function after bariatric surgery: evidence for improvement 3 years after surgery. Am J Surg. 2014;207(6):870–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Handley JD, Williams DM, Caplin S, Stephens JW, Barry J. Changes in cognitive function following bariatric surgery: A systematic review. Obes Surg. 2016;26(10):2530–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandes M, de Sousa A, Medeiros AR, Del Rosso S, Stults-Kolehmainen M, Boullosa DA. The influence of exercise and physical fitness status on attention: A systematic review. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2019;12(1):202–34. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basso JC, Suzuki WA. The effects of acute exercise on mood, cognition, neurophysiology, and neurochemical pathways: A review. Brain Plast. 2017;2(2):127–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2020–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Wang W, Yang C, Shen J, Shi M, Wang B. Improvement in nocturnal hypoxemia in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea after bariatric surgery: A meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2019;29(2):601–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arterburn DE, Telem DA, Kushner RF, Courcoulas AP. Benefits and risks of bariatric surgery in adults: A review. JAMA. 2020;324(9):879–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]