Abstract

Microfluidic tumors-on-chips models have revolutionized anticancer therapeutic research by creating an ideal microenvironment for cancer cells. The tumor microenvironment (TME) includes various cell types and cancer stem cells (CSCs), which are postulated to regulate the growth, invasion, and migratory behavior of tumor cells. In this review, the biological niches of the TME and cancer cell behavior focusing on the behavior of CSCs are summarized. Conventional cancer models such as three-dimensional cultures and organoid models are reviewed. Opportunities for the incorporation of CSCs with tumors-on-chips are then discussed for creating tumor invasion models. Such models will represent a paradigm shift in the cancer community by allowing oncologists and clinicians to predict better which cancer patients will benefit from chemotherapy treatments.

Keywords: Cancer stem cells, tumor microenvironment, tumors-on-chips, microfluidics

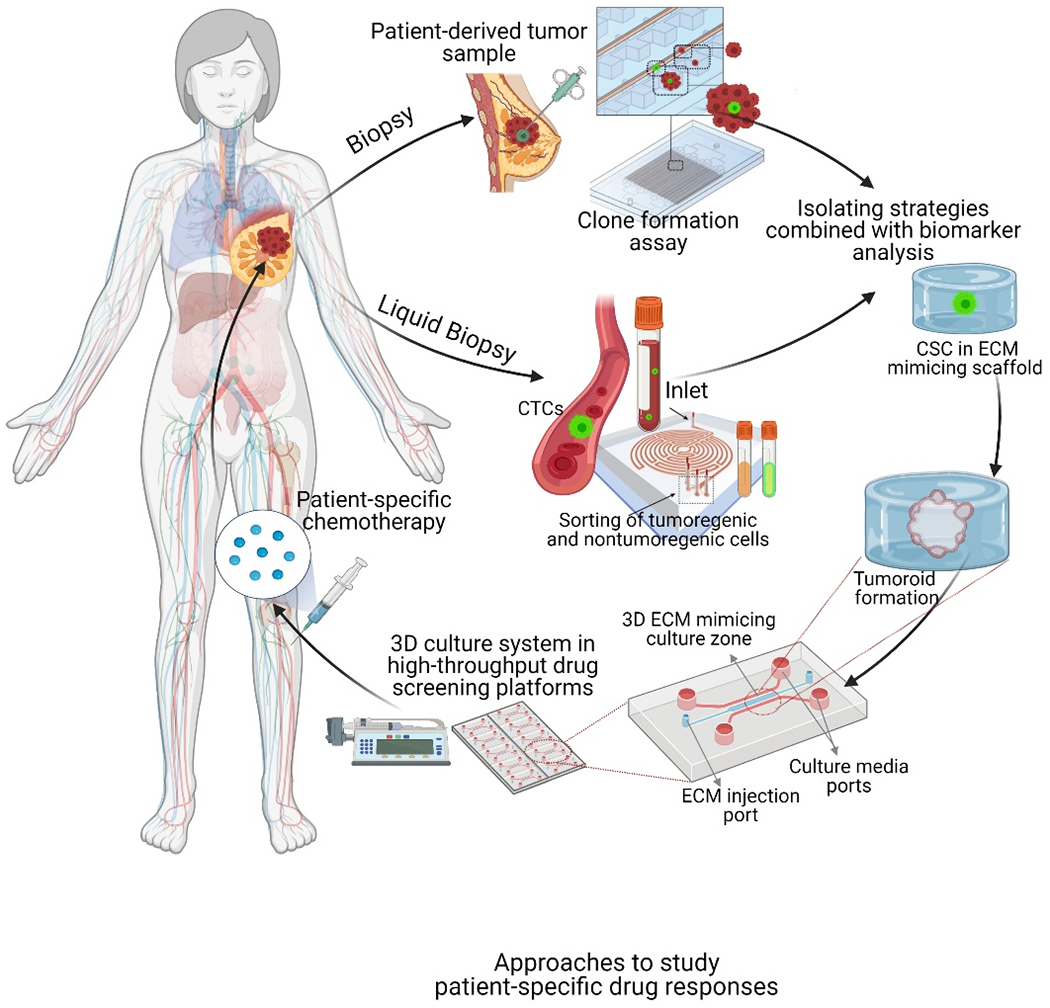

Graphical Abstract

Microfluidic tumors-on-chips have revolutionized anticancer therapeutic research by creating an ideal microenvironment for cancer cells. In this review, opportunities for the incorporation of cancer stem cells with tumors-on-chips are discussed for tumor invasion models. Such models represent a paradigm shift in the cancer community by allowing oncologists and clinicians to predict better which cancer patients can benefit from chemotherapy.

1. Introduction

Cancer stem (or stem-like) cells (CSCs)1 show distinctive properties such as self-renewal, the capability to differentiate into multiple lineages, and extensive proliferation.2 Malignant features have been observed in primary tumors during the conversion of tumor cells into CSCs, resulting in distant metastases. The role of CSCs in tumor progression, metastasis, and drug resistance has been postulated by several researchers.3–5 Welch and Hurst defined the hallmarks of metastasis by four distinguished features, including motility and invasiveness, ability to modulate microenvironments, plasticity, and ability to colonize secondary sites.6 The metastatic cascade’s multistep process begins with the development of metastatic cells and uncontrolled cell proliferation, followed by angiogenesis, motility and invasion, intravasation, dissemination and transport, cellular arrest, vascular adhesion, and extravasation, and colonization in distant organs within the body.6–8 Considering these steps at the cellular and tissue levels is critical for developing diagnostic tools and effective cancer treatments. The early CSC-based models for studying the response of cancers to systemic anticancer drugs have been two-dimensional (2D) culture models. Engineered 3D culture models have addressed a few of the challenges in using 2D models; however, they still lack some features of the tumor microenvironment (TME)9 and proper control over cell-cell interactions.10 Biomimetic platforms can process and manipulate small volumes of fluid through channels to support tumor growth.11,12 They provide spatial and temporal control at the micrometer and millimeter scales resulting in different ECMs, various types of cells, and fluids, which can be arranged to mimic the TME better and replicate the in vivo growth behavior of tumor cells.13

Microfluidic platforms support small sample sizes, low reagent consumption, short processing times, enhanced sensitivity, real-time analysis, and automation together in one unit.14 The delivery of nutrients and maintenance of physiological stresses in the micro-reactor enables cells to transform into tissue-like structures.15 Many microfluidic platforms use polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as the framework, in which the PDMS substrate provides simple fabrication, optical transparency, tunable elasticity, gas permeability, and cost-effectiveness.16 Some examples have been used for manipulating proteins and biological cells via biosensors, single-cell assays for disease diagnosis and modeling, organs-on-chips, and other applications.17,18 Microfluidic platforms can be used to study tumor progression in unconventional, radical ways with high-throughput screening potentials.19 However, they have been unable to capture and replicate extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness, proper conditioning of tumor cells, and ECM-cell interactions.

To tackle the challenges associated with conventional microfluidic devices in mimicking TMEs, tumors-on-chips have been introduced.20,21 Tumors-on-chips have been used to model oxygen and nutrient gradients,22,23 cell signaling and migration,24,25 proliferation behavior,26–30 protein and gene expression,31,32 morphological and organizational changes,29,33 and drug responses.34,35 They are composed of microfluidic channels in which media with nutrients are supplied to the surrounding cells,36 and the presence of multiple cell types in tumors-on-chips has been shown to mimic the key factors of the TME and the progression of tumor cells.37 These models allow us to simulate cell-cell signaling and the physical cues in the TME, such as hypoxia and physical forces. Therefore, these models can influence cancer cell growth.

CSCs contribute to anticancer therapeutic resistance, and patient survival depends on our ability to target CSCs in the treatments.38–41 The level of spatial and temporal control provided by microfluidics incorporating 3D cell culture has opened up new avenues for research on cancer invasion, extravasation42, and drug response.43 Not only have tumors-on-chips reduced drug development time and cost, but they have also eliminated ethical issues related to animal studies44 and are compatible with CSC research.45 The authors anticipate that the inclusion of CSCs into tumors-on-chips will provide novel insights into the metastatic behavior of the tumor cells and other key responses. In this review, the authors discuss the biological cues of the TME and how they are modeled by engineering technologies. Then, some approaches are proposed to tackle the challenges associated with incorporation of CSCs into tumors-on-chips.

2. Cancer Stem Cells and Tumor Microenvironment

Tumors exhibit significant interpatient and intrapatient heterogeneity. Even if individual cells within a tumor all share a common genetic reflection of their clonal origin, single-cell analysis has shown the existence of variations in genetics and epigenetics between different cells or locations within a tumor.46 One possible approach for explaining the heterogeneity is the clonal evolution model (i.e., stochastic model), which is based on the accumulation of mutations that leads to tumorigenic potentials in time via genetic and epigenetic changes. A second common approach includes the hierarchical conversion of stem cells to CSCs (i.e., hierarchy model) with malignant features associated with stem-cell niches. The first approach differs from the second because the mutation hypothesis in the clonal model cannot explain carcinogenesis, abnormal divisions, and epigenetic changes.47 Genetic and cell biology studies support the hypothesis that tumors contain more than the monoclonal growth of cells, and they should have CSCs. The inclusion of CSCs may ensure the invasion of malignant cells with its TME with myeloid cells, phagocytose, immune cells, and tumor-associated fibroblasts.48,49 Phenotypic plasticity of cancer cells denotes their capacity to interconvert between stem-like and differentiated states, which correlates with the hierarchical and evolution models.50 In this perspective, contingent on the genotype and the TME signals, cancer cells may return to the CSC pool to redeem long-standing tumor repopulation.51 This differentiation capacity is inherited (or the hierarchical model) or via mutations to a stem-cell-like permissive epigenome (or the stochastic model). The cell plasticity is thus considered as a third model that combines the first two models to provide the reversible transformation of cancer cells between stem-like and differentiated states.

The presence of CSCs has been a subject of controversy in the literature.46 Recent studies in stem cell biology have supported the CSC hypothesis.52 Wicha et al. explained the role of accumulated multiple mutations in normal stem cells for carcinogenesis. For example, the women exposed to radiation during their late adolescence in Hiroshima and Nagasaki showed the highest susceptibility of developing breast cancer.53 This is substantial as the mammary glands have the highest number of stem cells in the late adolescents period. In the case of carcinogenesis, tumor-initiating cells are the first mutated cells in the bulk that promote cancer origin to more mutagenic properties, but CSCs have a higher self-renewing capacity.54 Also, native stem cells can differentiate to mature cells for a specific tissue while using common signaling pathways (such as Wnt/β-catenin, Hh, Notch), similar to those of CSCs. Their self-renewability is processed by asymmetric replication and stochastic differentiation.

The kinetic properties of native stem cells include slow growth rate, residing in a specific niche, and short frequency of abundance. The CSC pools carry specific surface biomarkers and have short telomeres that can initiate a rapid tumor growth.55 When healthy stem cells transform to CSCs evading from immune surveillance and dysfunctional cell divisions can be observed. Differentiated cells can transform the other cells by their cancerous components. In a heterogeneous microenvironment, communications between native stem cells and CSCs promote malignancy.

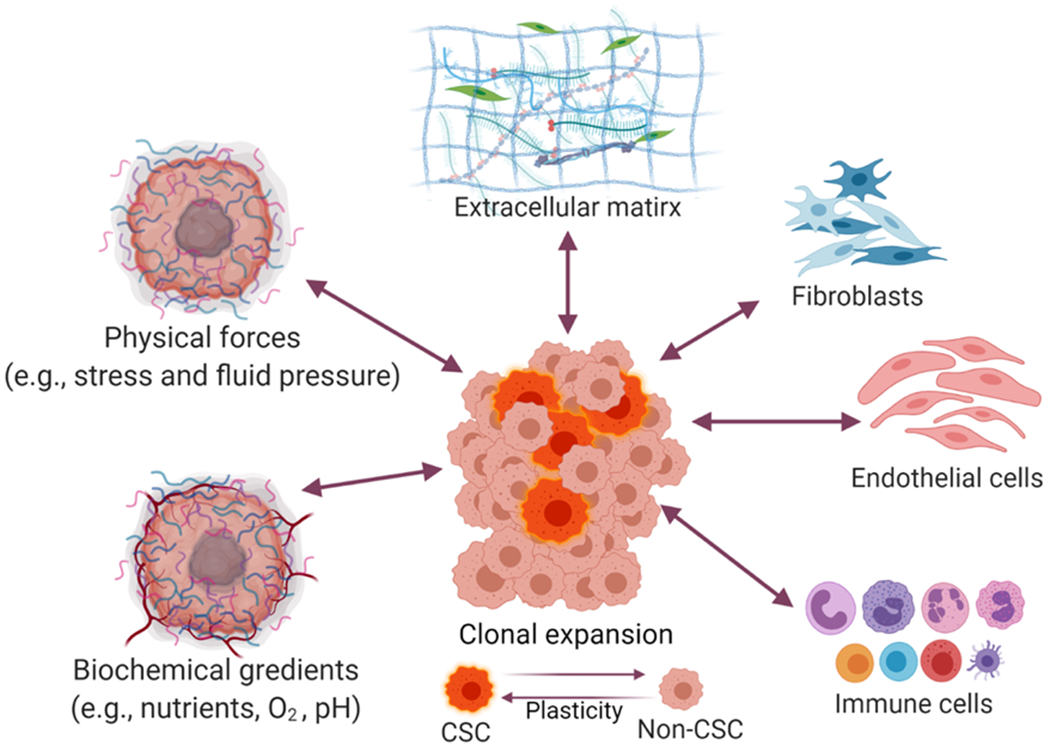

The TME includes biochemical or signaling molecules, different cell types, the ECM, and some biophysical cues.56 The specific features consist of fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells. The secreting factors and receptors control the signaling cascades for self-renewal and differentiation.57 In addition to these key factors, there is hypoxia induced by a lack of oxygen, as well as elevated solid stress and interstitial fluid pressure, all of which promote cell proliferation and resistance to drug transport (as summarized in Figure 1). Tumor-associated hypoxia promotes uncontrolled proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis of tumor cells. Hypoxic regions occur at the center of the tumor, and the ALDH+ population of CSCs stimulates the mesenchymal-like nature of cells and gains a high proliferative rate as well as their resistance to death. In one study, hypoxic effects in the TME, including CSCs were evaluated in a study for glioma related to rapid tumor growth.58

Figure 1.

Schematics of tumor microenvironment (TME) factors

Solid stress was shown to impact gene expression of tumor cells and trigger the potential invasiveness of cancer cells.59 Among TME factors, the CSC niche contributes to the invasion, metastasis, and promotion of angiogenesis. The following factors play critical roles in cell-cell communication: cancer-associated fibroblasts, tumor-associated macrophages, tumor-associated neutrophils, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), cell-mediated adhesion, and soluble factors.60 It is difficult to distinguish the TME factors associated with the biological activity of CSCs, and further research is required to study the contribution of each factor into CSCs activities.

The identification and characterization of the new CSC biomarkers are important in selecting proper treatments. They can include miRNAs (miR-34a, miR-199a, miR-181, miR-125b-2, and miR-128), cluster of differentiation (CD) biomarkers (CD44, CD34, CD38, and CD133), enzymatic activity of some markers (such as ALDH1), and other kinetics measurements of CSCs. Since CD biomarkers seem to be insufficient to characterize the CSC, cancer-specific surface biomarkers seem necessary to identify the CSCs.61 In a heterogeneous tumor bulk, each cell has different kinetics ranging from a quiescent state to aggressive growth and invasion. Poleszczuk et al. indicated that migration rate, proliferation potential, spontaneous cell death, and symmetric CSC division show behavior of cells and differences between the stem cells and CSCs. Cell proliferation rate is a good indicator of the cell behavior; for instance, some CSCs can cause rapid growth in the tumor while other CSCs remain dormant for a prolonged period.62

CD44 is a phenotypic marker that is expressed in various cell types, and overexpressing of this marker is recognized in the tumor state. CD44 has isoforms which are named CD44v, and CD44s play roles in the pathogenesis of cancer and EMT. Initiation of EMT begins with the expression of CD44v to CD44s, and it was shown that the process of EMT required upregulation of CD44 in pancreatic cancer cells. The biomarker CD44 and its isoforms have multi-functional properties in the activation of cell signaling pathways and cancer pathways.63

A minor population of tumor cells was originally found to be clonogenic and metastatic, for in vitro and in vivo, suggesting the existence of CSCs.64–69 Al-Hajj et al. isolated tumorigenic and nontumorigenic subsets of cancer cells from breast tumor biopsies as the first evidence of CSCs in solid tumors. They have serially passaged these tumorigenic cells and observed each in vitro model exhibited elevated CD44+CD24−/low. These biomarkers are maybe insufficient to identify CSCs because human breast CSCs and normal stem cells express these biomarkers. They suggested epithelial-specific antigen +CD44+CD24−/low Lineage− and observed that CD44+CD24−/low Lineage− tumorigenic cancer cells can undergo processes analogous to the self-renewal and differentiation of normal stem cells.70 Traditional CSC identification protocols have been based on surface biomarkers and self-renewal capacity and propagating into the tissue. Some functional biomarkers have been recently introduced to improve CSC identifications, such as ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity, the activation of some key signaling pathways, live-cell inter-cellular molecules, and single-cell detections.71 For example, Ginestier et al. isolated normal and malignant breast stem cells utilizing the enzymatic activity of ALDH1.72

Biomimetic cancer models may include one or several TME factors. These can be introduced through a pre-conditioned cell culture medium.73 For example, in one study, a group of injected pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), regulated by epigenetic effects, was injected into a mouse model while DNA hypomethylation was postulated simultaneously to cause the conversion of iPSCs into CSCs.74,75 External modulators can also be introduced to induce stemness in different types of cancers.76 Some examples of external modulators are extracellular such as ATP, metabolite lactate and ketones, hypoxia, and hepatocyte growth factor. Stem cell signaling pathways provide developmental homeostasis, and their dysfunction can cause the transformation of stem cells to CSCs.77 These pathways include Janus-activated kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT), Hedgehog, Wnt, Notch, and others. These pathways each play a role in many biological processes and also support CSC function.78 For example, JAK/STAT related genes were found to be overexpressed in stem-like cells isolated from prostate cancer cells.79

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a key step in metastatic progression that triggers the transformation of the normal to cancer cells in the TME. A large number of transcription factors (e.g., Snail, Slug, deltaEF1, Zeb1, and Bmi-1) induce and regulate the EMT.80 Following the EMT process, the tumor cells are disseminated from primary regions, thus migrating into the circulatory system. Known signaling pathways of EMT regulation are hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), Wnt/β-catenin, notch, and hedgehog.81,82 Human healthy mammary epithelial cells were found to express stem cell markers associated with the induction of the EMT process. Induction of EMT increased overexpression of transcription factors like Slug and Sox9 cause stem-like state. Low expression of E-Cadherin, high levels of vimentin, and quiescent state can be observed in the CD44+/CD24− population, and the ALDH+ population shows a high expression of E-Cadherin and low expression of vimentin. The TMEs are regulated by CSCs population and states throughout transcriptional switch from MET to EMT or vice versa.83

In addition, the expression of E-cadherin (as an epithelial biomarker) was increased while MMP2 expression was decreased in the stem cells of glioblastomas.84 In another case, the role of CSCs in EMT-mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) was observed in breast cancer patients whose bone marrow samples had a large population of CSC biomarkers.85 TME’s acidic environment around the tumor cells further inhibits nutrients and oxygen. It results in further tumor progression and increased drug resistance due to proteases breaking down in tumor adaptation. Another difficulty involving TME, which has been associated with impaired vascularization and triggered stem cell dysregulation, is hypoxia.86 In addition, in the mesenchymal-like CSCs and epithelial-like CSCs show proliferative properties while ALDH+ cells create more hypoxic conditions at the center. The presence of ALDH+ cells can lead to ineffective treatment of antiangiogenic agents (making hypoxic and acidic conditions).87 The acidic condition induces stem cell transformation to CSCs, which can change the tumor microenvironment by transforming neighbor fibroblasts into cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs).88 TME’s hypoxic-affected cells reduce the uptake of chemotherapeutic agents that eventually leads to multidrug resistance. All these factors can control the behavior of tumor cells, in particular for CSCs, and researchers need to consider them in their solutions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected TME models based on various ECM composition for cancer modeling

| Cancer type | Model | ECM and Cellular Composition | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain | Spheroid culture | GBM, tMVECs, bFGF and EGF, collagen, HA, Matrigel | 89 |

| Tumor-on-chip | GB3, HUVECs, VEGF, Matrigel, Fibrin | 90 | |

| Hydrogel-based organoid | SU3, U87, bFGF, EGF, gelatin, alginate, fibrinogen mixed hydrogel | 91 | |

| Breast | Spheroid culture | MDA-MB-231, MCF7, collagen, Matrigel, FGF, EGF | 92 |

| 2D Microfluidics | MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, T47D | 93 | |

| Liver | Spheroid culture | HePG2, HCSC, PLC/PRF/5, Matrigel | 94 |

| 2D Microfluidics | HePG2, HeP3B, PLC/PRF/5, | 95 | |

| Lung | Spheroid culture | A549, NCI-H1395, NCI-H1650, NCI-H1975, NCI-H1993, NCI-H2228, NCI-H23, NCI-H358, NCI-H460, HCC827, PC9, and SW900, EGF, bFGF, Matrigel | 96 |

| 2D Microfluidics | LCSC, dLCSC, EGF, bFGF | 97 | |

| Ovarian | Spheroid culture | OVCAR3, U937, CSC/M2-macrophage, PBMCs, Cytokines | 98 |

| Bone | Spheroid culture | MNNG/HOS, bFGF, EGF, | 99 |

3. Culture Models for the Tumor Microenvironment

3.1. 3D Culture Models

Traditional 3D culture models have been established to mimic tissue-specific TME, where tumor cells can proliferate and differentiate.100 The culture models can be categorized into non-scaffold, anchorage-independent, and scaffold-based systems in which formed spheroids are integrated into a biomaterial scaffold.101 These methods may differ in terms of cell sources, protocols for cell preparation, and the time periods necessary for the creation of 3D culture models. Some detailed summaries of 3D culture methods can be found in the literature.102–104 One well-known approach for the creation of 3D culture models includes causing floating conditions for tumor cells.

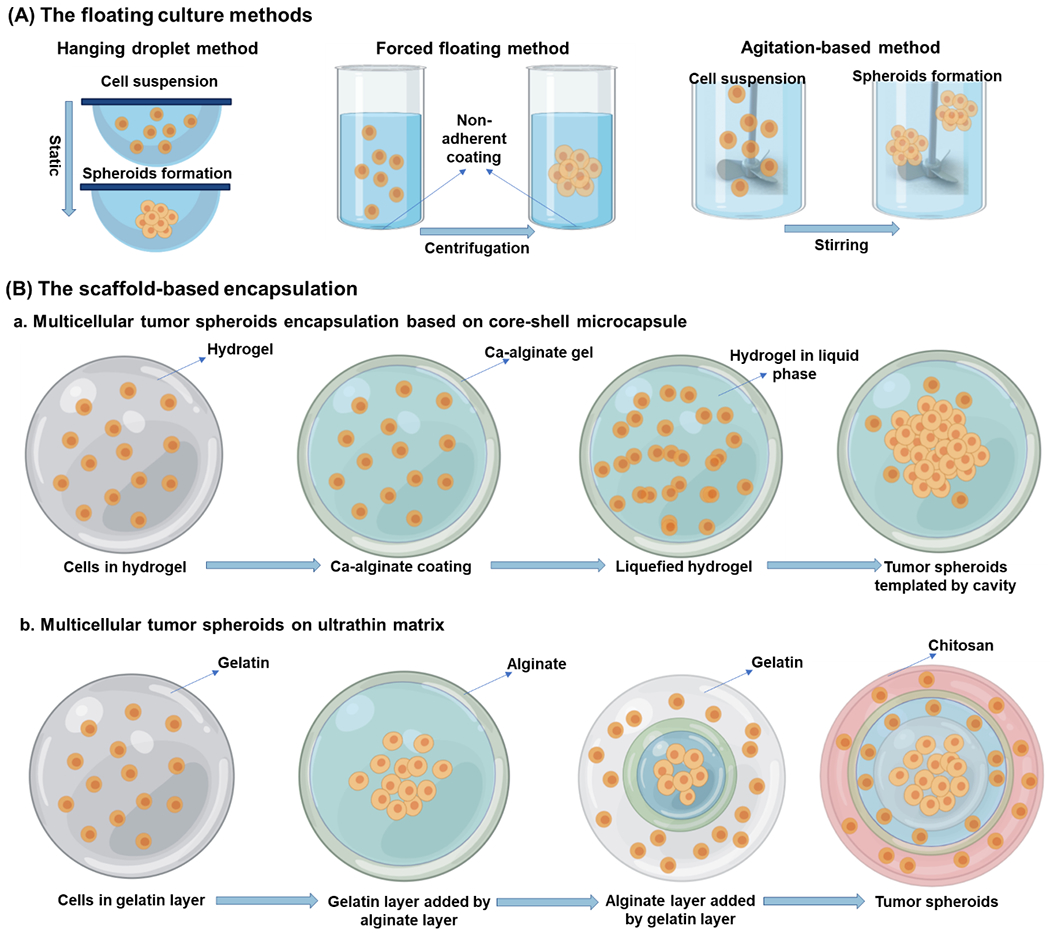

The floating culture method works based on non-adherent surfaces of plates. There are three main floating models, named as I) hanging drop method, II) the forced floating method and III) the agitation-based method (as illustrated in Figure 2A).35,105 In the hanging drop method, medium-based cell suspension droplets are first created in well plates. The well plates are then inverted; thus, the droplets hang due to surface tension. The forced floating method prevents the adhesion of cells to any substrate by using a non-adhering coating; therefore, cells are able to float. In the agitation method, cells in the suspension are stirred gently to prevent the attaching of the cells to the substrates. Recently, a low-cost and efficient method was developed for CSC prostate cancer cells enrichment culturing using a hydrophilic filter paper. Hydrophilic filter paper allows the spontaneous formation of tumor spheroids while the expression of CSC biomarkers is elevated. This spontaneous formation was found to be associated with increased hydrophilicity of cellulose fibers. Cell aggregation is promoted through limited space and niche between the fibers.106

Figure 2.

(A) An illustration of floating sphere culture systems; these systems provide cell-cell interaction in the absence of matrix using the suspension in container walls; (B) The scaffold-based encapsulation a. Multicellular tumor spheroids based on various matrix milieu; b. Multicellular tumor spheroids are based on the layer-by-layer ultrathin matrix. These structures allow the formation of the niche-like matrix for the generation of tumor spheroid microenvironment. (modified from He et al.119)

Stem cell-based spheroids provide cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, tissue-specific conditions, biological functions, a controlled TME, and in vivo-like physiology.107 An initial spheroid tissue model was created using a soft hydrogel.108 The differentiated tumor cells and stromal cells were not able to grow into a spheroid formation. Their material model was used to form new colonies in the absence of cell adhesion peptides.109 The limited throughput ability of CSCs (representing only ~ 0.4% of the tumor cells) has hampered their use for further processing.110

Multicellular spheroid tumor models have also been developed to investigate the interactions between cells and microenvironments.111 A cell spheroid can be defined as compact and well-rounded (Figure 2B). These aggregated cells can interact with each other and behave similarly to analogous in vivo tissues.112,113 The spheroid model has many advantages compared to 2D cultures, such as recreating hypoxia-induced angiogenesis normally observed in tumor spheroids with diameters more than 500 μm,114,115 as well as reduced gas,116 nutrient,117 and drug exchange.118 Different ECM mimicking hydrogels were used to investigate the effect of ECM properties on the migratory response of GSCs in a spheroid culture model. Results indicated that GSCs exhibited different single and collective migratory responses related to hydrogel porosity and stiffness values.89 In another study, the interactions between ovarian CSCs and macrophages of hanging-drop-made spheroids were investigated. The results showed that CSCs upregulated the key macrophage biomarkers significantly compared to other ovarian cancer cells.98

The effect of pluripotency properties of 3D culture models on drug response was explored by comparing 2D monolayers with dispersed 3D cultures. It was found that the 2D monolayer culture and dispersed 3D culture models were not adequate to evaluate drug response and pluripotency of tumors.92 They showed that better recreations of in vivo tumor conditions, such as chemoresistance, metastasis, and recurrence, were successfully represented in a 3D spheroid model by including the role of CSCs. Tumor spheroids of a hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG2),94 human osteosarcoma cell line (MNNG/HOS),99 and primary cultures from early-stage lung carcinoma patients96 with enriched CSC potential were established through spheroid formation assays. Generated spheroid subclones displayed aggressive characteristics of tumor-initiating cells such as exponential growth (the passage number > 30), drug resistance, and high invasion capacity, which is related to tumor progression and metastasis-association of aggressive phenotypes of CSCs. More recent culture models are adaptable with microscale technologies that are compatible with automated high-throughput screening.100

3.2. Organoids

Cancer tissue samples can be obtained from patients’ primary tumors, patient-derived xenografts, or genetically and chemically induced animal tumors. Such samples can be used to generate organoids and provide a better understanding of the tumor bulk behavior and characteristics in their natural microenvironment. Better tumor models are created through morphology, cell-cell interactions, and gene and protein expression. These models result in a tumor bulk which more closely resembles the original tumor.120 In addition to patient samples, adult stem cells, embryonic stem cells, or induced pluripotent stem cells can also be used by reprogramming them into an embryonic-like pluripotent state. The use of stem cell-based organoids assists in the development of unique characteristics of organs, the modeling of diseases at different stages, regenerative therapy, and the testing of many parameters at a developmental level.121

Stem cell properties are required to supply both intrinsic and extrinsic signals in cell autonomy and self-organization. Bioengineering approaches are used to manage the physiological control of organoids.122 Improving the bioengineering approaches and creating complex niches are significant for downstream applications, elucidating the mechanisms of diseases and progressing towards regenerative medicine. The stem cell niche requires niche-related signals to support physiochemical conditions for differentiation; therefore, a specialized microenvironment should be created with required components for targeted tissues or organs. Growth factors or other components are used to create tissue-specific signaling pathways that play crucial roles in cell survival, self-renewal, and differentiation. Cell-cell communication is the main process for stem cell niche, and ECM components take part in this signaling cascade with laminin, fibronectin, and collagen, where they integrate with integrins.123 The most commonly used ECM model is Matrigel, which provides a scaffold structure and allows important signaling cues to activate cell-cell communication.121 Matrigel can also be used to modulate neural stem cell and hematopoietic stem cell behavior. Synthetic polymers (such as polyacrylamide and polyethylene glycol) or natural macromolecules (for instance, agarose or collagen) have also been used. Here, the hydrogel was combined with collagen to generate the epidermal niche ECM to induce vascularization and healing for mesenchymal stem cells’ function.124

Modeling the heterogeneous cell colonies in TME creates an in vivo-like environment. Thus, reprogramming the different types of cancer cells seems crucial for modeling the disease. Reprogramming cancer cells by using induced pluripotent stem cells from the somatic cell method is important to mimic the dynamic structure and to understand the tumorigenesis. In the past ten years, many studies showed that the characterization of tumorigenic properties was assessed using induced pluripotent cancer cells (iPCCs).125 For instance, Chao et al. demonstrated that myeloid monocytic leukemia cells were reprogrammed and became acute myeloid leukemia (AML)-induced pluripotent cancer cells, which stimulate epigenetic and gene expression alterations, thus approaching an in vivo-like environment. Genetic alterations in the AML-iPCCs were used to predict the response of clinical chemotherapeutic drugs.126

Myeloid malignancy was reprogrammed using iPSCs and iPCCs at different stages of the disease (low risk, high risk, and AML) and correlated with the observed prognosis.127 This provided observation of the prognosis and facilitated the administration of the drug at the right time. In contrast, reprogramming of the melanoma using iPCCs caused drug resistance.128 Additionally, imatinib resistance was developed in imatinib-sensitive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) due to iPCCs reprogramming129 while reprogrammed cells from colorectal cancer develop sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs.130 All these results show that iPCCs reprogramming is dependent on the cancer cell type and its origin. In CSC-based platforms, the prognosis is better controlled in every stage of the disease and epigenetic alteration.

Microcapsules are defined as a consistent microenvironment that provides autoimmune protection and long-term stability for enclosed cells. The microcapsule-based 3D structure is created using alginate or other hydrogels, and this structure allows the interaction of the biological cues between cells.131 Because stem cells secrete various trophic factors to avoid immune rejection, a controlled microenvironment should be created with biocompatible material. Encapsulation of stem cells prevents immunological rejection and enhances the permeability of essential nutrients, oxygen, and most cellular secreted factors. It also restricts the passage of larger molecules, such as antibodies and immune cells.132 For example, human MSCs were modified to express hemopexin-like proteins to inhibit angiogenesis in glioblastoma. Alginate microcapsules were designed next to these microcapsules and were transplanted subcutaneously into nude mice. Both the tumor volume and the weight of the mice reduced significantly compared to the control group.133

3.3. Microfluidic Models

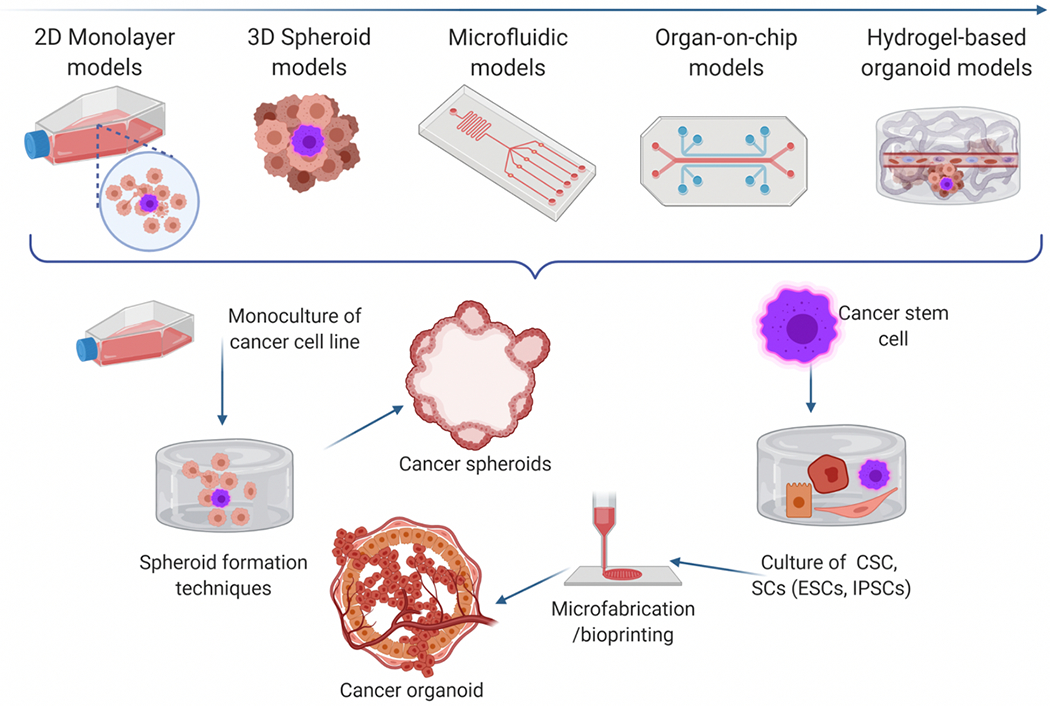

Conventional 3D culture and organoid models have some limitations, such as geometrical and visual inspection throughout the migration process and quantifying the invasion of 3D spheroid models.134 These limitations have led researchers to focus on microfluidic devices that allow controlled delivery of reagents and placement of tumor cells in desired patterns.135 One key development of microfluidic devices is their integration with organs-on-chips (Figure 3); this has opened new horizons in the field of cancer research.136

Figure 3.

a) Evolution of cancer modeling from simple 2D cultures to cancer-on-chip and organoid.

Organs-on-chip is a top emerging technology with the potential to reduce drug development time and cost and to alleviate ethical considerations related to animal studies.44 When compared to the conventional in vitro 2D cell cultures and in vivo animal models, 3D models have a better capacity to mimic and replicate human pathophysiology.137 Organs-on-chips can be defined as 3D organotypic devices; they can accommodate 3D cultures of multiple cell types and provide flow and mechanical input.15 Tumors-on-chips are thus microfluidic devices developed to replicate tumors through physiological mimicry that allows continuous perfusion of nutrients gasses and testing pharmaceutical agents.138 As an experimental approach, cancer modeling through microfluidics has great potential to improve our understanding of cancer behavior and effective drug development.139 Cancer cell motility is more sensitive to surrounding stimulations due to ECM components compared to noncancerous cells.140 Many studies have hypothesized that the CSC phenomenon might be the key reason for anticancer therapeutic resistance, and patient survival may ultimately depend on the elimination of CSCs.38–40,81 Therefore, recently emerged microfluidics models, tumors-on-chips, could have revolutionary and novel contributions to CSC research.45

Conventional microfluidics involves the use of lithography-based molding and casting processes. One of the most critical requirements of microfluidic devices is optical transparency; this restricts the available materials and manufacturing techniques that can be used. The processes such as replica molding, injection molding, and embossing assist in the fabrication of conventional organs-on-chips. Silicon, glass, and plastic materials are mostly used during these fabrication methods.12 Microfluidics technology has advanced, other functionalities, such as gas permeability and biocompatibility, researchers working especially in pharmaceutical, biochemistry, and biomedical fields have asked for this technology. As a result, much of the microfluidics in this field use crosslinked polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), an elastomeric material that provides optical transparency, biocompatibility, flexibility, and gas permeability, all of which are required for microfluidic devices used in successful cell culture processes.141 An early example of microfluidic devices was developed for real-time tracking of the migration of hundreds of cancer cells inside mechanically constrained microchannels.142 They used time-lapse images for quantifying the cell migration through microchannels, observing continuous and persistent motility in one direction for several hours in the absence of an external gradient. This work also examined the migration behavior of the cancer cells in the presence of drugs. The results showed that the increased concentration of nocodazole caused a reduction in the speed of cancer cell migration.

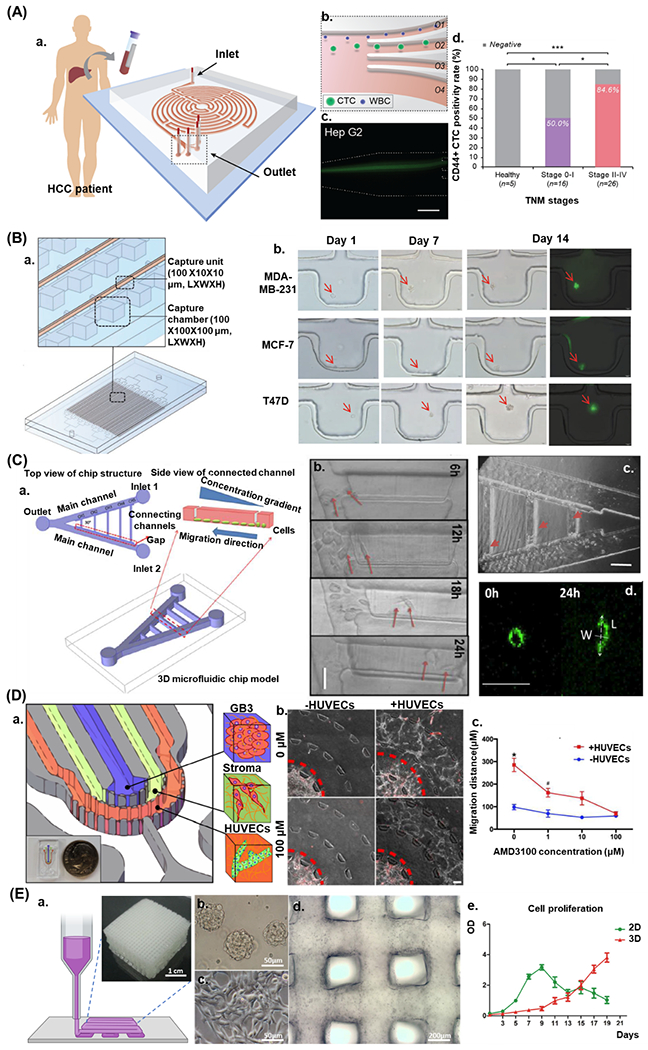

To screen CSC-specific biomarkers in a single-cell assay, Lin et al.93 fabricated a high-throughput PDMS chip containing single-cell capturing units, using the advantage of the single-cell clone-forming capability of CSCs, to investigate specific therapeutic agents on breast CSCs (Figure 4B). The chip allows cell capturing, CSC identification, and clone-forming inhibition assays to be conducted on the same device using cell retentions within the upper outlet channel. After perfusing cell suspensions through the channel, single cells are trapped by the top layer intersections. This is associated with open-outlet and size retention effects. Trapped cells would lead to increased flow resistance, thus preventing other cells from passing the channel. After flushing out the residuals, the chip is rotated to place the trapped cells inside the culture chambers. The results showed that only a few cells in single-cell arrays survived and were able to form tumor spheroid. Tumor sphere formation rates of microfluidic assays were slightly lower than the conventional multi-well plate method, allowing for both cell-cell interactions and cell aggregation.

Figure 4.

A) Characterization of the Labyrinth device with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): a. Circulating tumor cell (CTC) isolation workflow using the Labyrinth device, b. CTC separation from white blood cells (WBCs) by differential inertial focusing and collection, c. Fluorescent microscope image of differentially focused cell streaks by inertial focusing and migration for cell separation and CD44 biomarker analyses (scale bar is 100 μm);95 B) Schematic of the microfluidic chip and continuous cell survival of the single-cell array (MCF7 cells), a. Schematic of the single-cell array microfluidic chip and the cell-capturing unit, b. Single-cell-derived clone formation rate of MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, and T47D cells (n = 3, p < 0.0001), c. Consecutive microscopic pictures showing the formation of single-cell-derived tumor spheres on-chip (scale bar is 50 μm);93 C) 3D schematic illustration of microfluidic chip design for multiple gradients generation: a. The microfluidic chip consists of two main channels forming a 30° V-shaped structure and five parallel connecting channels with different lengths, b. Image of dLCSC migration in the CH1 in normal condition (scale bar is 50 μm). c. The LCSC migration locations in channels at time point 18h (scale bar is 100 μm). d. Graphical description of aspect ratio (L/W) of the LCSC in CH1 during chemotactic migration (0 h and 24 h; scale bar is 50 μm);97 D) Schematic of GSC-EC interaction. a. Schematic of the vascular niche within the GBM tumor microenvironment. b. CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling in GSC-EC interaction. Phase-contrast image of GSC (red) invading in the presence of HUVECs in different concentrations of AMD3100. The red dashed line delineates the average migration boundary (scale bar is 100 μm). c. Quantification of invasion distance for each condition;90 E) a. The schematic of the printing process of in vitro brain tumor model and 3D bioprinted GAF hydrogels mixed with glioma stem cells SU3. b. SU3 grown in spheres in stem cell medium. c. SU3 grown on a 2D substrate in complete medium. d. 3D bioprinted SU3 at day 1 of culturing. e. Cell proliferation of SU3 in a 2D environment and GAF hydrogels (3D) 91. Reprinted and modified by permission of Elsevier, John Wiley, and Sons, Springer Nature, American Chemical Society, IOP Publishing.

Zou et al. developed a V-shaped microfluidic network to study gradient-induced chemotaxis of lung cancer stem cells (LCSCs) and differentiated LCSTs (dLCSCs) in real-time. They trapped the cells by a gap between main and connecting channels after loading cell suspension droplets with different densities. (Figure 4C). They showed that the β-catenin dependent Wnt signaling pathway regulates the chemotaxis behavior of both LCSCs and dLCSCs. This study also showed the importance of cell heterogeneity, observing both cell types behaved differently to the same external stimuli. They further observed the acceleration of dLCSC to be more sensitive for gradient stimulation in comparison to LCSCs, and the application of XAV-939 inhibited the β-catenin signaling, thus leading to the suppression of chemotactic migration rates.97 Another PDMS microfluidic device was developed for the detection of CD44, a potential CSC biomarker. Labyrinth microfluidic devices can isolate circulating tumor cells in blood samples obtained from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients. HCC cells were collected and labeled with a fluorescent dye. Then labeled cells were diluted into non-HCC subject blood samples or a buffer solution before loading the suspension into labyrinth microfluidic device. Labyrinth device separates CTCs from white blood cells through differential inertial sorting and collecting principle (Figure 4A). A correlation between circulating tumor cell rates and different tumor stages in patients was shown. They also revealed that the majority of the HCC patients tested positive for CD44, a pluripotency biomarker, in circulating tumor cells that could indicate the relation between pluripotency properties and dissemination 95. While microfluidics-based single-cell assays are generally used for CSC studies, microfluidic assays accommodating 3D cell cultures are rare.

More recent microfluidic chip designs have comprised cell-embedded 3D ECM hydrogel organs-on-chips. Hydrogel microfluidic systems have numerous advantages in replicating an organotypic model due to their high permeability and biocompatibility.143 For example, hydrogels enable the diffusion of solute molecules (e.g., nutrient, oxygen, growth factors); they are optically transparent, thus providing an observable microenvironment for cells, and most hydrogels have comparable stiffness and tunable mechanical properties for better replicating the ECM.144,145 Some of these models have used direct bioprinting through cell-laden hydrogels or using sacrificial hydrogels for post cell seeding processes, while others have used hybrid techniques, including casting cell-laden hydrogels into a lithography-based PDMS mold.146–148 For example, Baker et al. showed that locations of the strongest gradients define positions of angiogenic sprouting within a 3D ECM model.146 They proposed a lithography-based hybrid technique, using sacrificial microchannels patterned and molded-in sacrificial gelatin, to generate temporally and spatially defined soluble gradients. In another study, Meng et al.149 used a hybrid bioprinting technique to recreate a TME while modeling the metastatic cancer steps such as invasion, intravasation, and angiogenesis in order to explore the molecular mechanism of tumor progression. They used a custom-built extrusion-based bioprinter to place tumor, stromal, and vascular cells precisely according to their physiological functions in a hydrogel-based chip that can serve as a high-throughput anticancer drug screening tool. They also printed stimuli-responsive core/shell capsules carrying growth factors that can be manipulated through programmable laser-triggered sources. These capsules are released using a GelMA/Gelatin combination as the core and use an AuNR-functionalized poly-(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) film as shell ink. To prepare the metastatic model, designed culture chambers were printed in the glass bottoms of the Petri dishes using room-temperature-vulcanized silicon. To create vascular cavities, they first used a pin-molding technique, then they bioprinted a droplet of A549-laden fibrin for simulating a primary tumor, placed 1 mm away from the vessel, and printed microcapsule arrays while fibroblasts were integrated into the surrounding hydrogel as supporting stromal cells. This combination promoted the remodeling of the ECM. Zhang et al.150 combined inkjet printing with a lithography-based PDMS chip to investigate drug metabolism and the diffusion of an anticancer drug, Tegafur, on co-cultured human hepatoma (HepG2) and glioma cell lines (U251). They encapsulated cells into 0.5% alginate sodium hydrogel with 106 cells/ml cell density to bioprint cell-laden hydrogel precisely onto a glass substrate via inkjet printer and then integrated the hydrogel with an oxygen plasma-treated PDMS layer with microchannels. After chip integration, they injected the CaCl2 solution into the chip at the flow rate of 20 ml/min to crosslink the cell-laden alginate.

Dai et al. bioprinted a 3D glioma stem cell model using a modified porous gelatin/alginate/fibrinogen (GAF) hydrogel to mimic the ECM. They crosslinked the GAF hydrogel system by adding transglutaminase as a crosslinker, targeting the gelatin component of the hydrogel (the main component of the GAF hydrogel). They then bioprinted glioma stem cell-laden GAF to observe the growth characteristics, stemness, and differentiation potential of the cells (Figure 4E). Finally, they evaluated the results comparing the cells in the 3D printed GAF with the 2D culture condition using a chemotherapeutic drug.91 Truong et al. developed a hydrogel-based organotypic microfluidic model to investigate the interaction of glioma stem cell (GSC) vascular niche and endothelial cells (ECs) and to identify the signaling cues which play crucial roles in invasiveness and phenotype (Figure 4D). The organotypic platform consisted of three concentric semicircles of tumor, stromal, and vascular regions embedded in a micropatterned PDMS chip. Trapezoidal microposts were placed at the boundaries of the semicircles to allow mass transfer throughout the layers. They coated 3D cell culture regions on the chip by injecting poly-D-lysine to enhance the surface attachment of cell-laden hydrogels. HUVECs were encapsulated in a fibrin solution with a cell density of 20x106 cells/ml to model vasculogenesis, and then the solution was injected into the vascular cavity of the chip. GB3-RFP cells (15x106 cells/ml) were encapsulated in Matrigel and injected in the tumor region, then Matrigel was directly injected in the stroma region and incubated to allow hydrogel polymerization. They showed that CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling was involved in promoting GSC invasion in a 3D vascular microenvironment.90

4. Key Lessons and Future Directions

4.1. Governing Factors

CSC research is still in the early stage of development. The key challenge is to isolate CSCs to increase our understanding of their new pathways and specific roles in the well-known drug resistance.151 The isolation strategies should be based on some vital rules, such as the isolated cells should not contain any nontumorigenic cells,152 because CSCs and normal stem cells can express the same biomarkers.70 Microfluidic devices can be used to overcome the limitations of biomarkers with strategies to isolate cancer cells from nontumorigenic cells. For example, labyrinth microfluidic device can separate CTCs from white blood cells through differential inertial sorting and collecting principle.95 Microfluidics has been a radical solution for resolving limitations of culture methods through the development of well-controlled fluid delivery to cells. The key parameters in the fabrication of proper microfluidic tumors-on-chips are summarized in Table 2. The range of parameters shows the flexibility in our preparation of tumors-on-chips with potential tuning towards CSCs. The feasibility of culturing CSCs in microfluidic devices has been tested and validated by some recent studies, such as improving the diagnosis of CSC-related biomarkers. In addition, microfluidics is well supported by computer-based modeling, in which simulations can be applied in such devices for in-depth analysis in contrast to most conventional methods. Despite these advancements in microfluidics, CSCs are used most commonly in drug screening platforms but are rarely used in cancer models. The challenges associated with isolating CSCs and the need for special culture conditions for both proliferation and differentiation might have slowed down their incorporation in 3D and microfluidic models. The presence and usage of TME attributes are likely to remove such limitations.

Table 2.

Different considerations in selecting microfluidic tumors-on-chips

| Parameter | Options | Selection Criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Geometrical features | Length, height, width of channels, patterns | Biological questions |

| 2D or 3D modeling | ||

| Long term cell culture, intact geometry, cell aggregation in spherical form | ||

| Perfusable for biochemical gradient, tailorable stiffness for migratory response | ||

| Encasement materials | Silicon, glass, polymer | Cost, biocompatibility, chemical inert, imaging, robustness, surface coating, optical transparency, stability, permeability |

| Manufacturing & assembly | Cast molding, scale of fabrication, UV lithography, 3D printers | Microinjection, cost of fabrication, prototype, mass production |

| ECM material | Matrigel, fibrin, collagen, hyaluronan, decellularized ECM, alginate | Sample type, duration of cultivation |

Clinical applications of microfluidic platforms depend on several practical considerations, particularly for precision medicine (Figure 5). The complexity in patient samples may require a high level of customization in the model. The small number of CSCs that can be isolated and kept functional may limit high-throughput screening in tumors-on-chips. Further additions, such as an increased number of cell types and proper vasculature networks that mimic the TME, should be added to engineered models.153 The CSC niche can be introduced into new technologies, including tumors-on-chips and 3D bioprinting. Recent advancements in improving the versatility of these techniques have made them attractive choices for tumor modeling and therapeutic developments. Well-controlled studies and analysis of cell-cell interactions, CSC behavior, and CSC-specific biomarkers are now possible through microfluidics. The response of CSCs to cancer drugs is also crucial because of its pivotal role in resistance to cancer therapy as well as being the prime source of tumor recurrence. The inclusion of CSC into tumors-on-chips is needed for future cancer modeling.

Figure 5.

Proposed strategy in personalized medicine for CSC-based drug resistance

4.2. Clinical outlooks

One of the current limitations in the field of oncology is predicting which patients will respond to which therapy. For example, in patients with incurable lung cancer, the response rates to chemotherapy vary, but the typical response rate for first-line chemotherapy is between 7% and 40%. This means that up to 93% of patients who receive the therapy will suffer the toxicities of therapy without any benefit.154 Other types of cancer can have even lower median response rates: sarcomas, for example, have a response rate of less than 20%.155 In addition, some patients who have no response at all, even the patients whose cancer does respond to treatment, cancer may respond better to one type of chemotherapy than another. In both situations, there is a limited ability to predict which patient will respond and which chemotherapy will produce the best response. Chemotherapy can be very toxic and also expensive to both the patient and the healthcare system. To remedy this, CSC-based models seem promising in analyzing the tumor resistance to chemotherapy agents. This could lead to the ability of clinicians to develop personalized medicine and give chemotherapy primarily to patients who will benefit from such. If tumor samples or primary cells that were collected at the time of diagnosis could be placed into a chip and tested in a lab, clinicians could test which chemotherapy agents would give the best result and avoid those treatments that would not benefit the patients. The successful development of such models will represent a paradigm shift in the cancer community by improving patient’s quality of life, potentially prolonging survival, and opening up new clinical trials to test various new drug formulations.

4.3. Drug screening platforms

A potential CSC-specific therapeutic targets the CSC and bulk tumor cells at the same time due to plasticity ability of the CSCs.151 The use of organotypic microfluidic models allows mimicking the cellular composition in the TME, and the dynamic flow provides biomimetic body fluid;156 they maintain the phenotypes of tumor cells and the tumor grade for applications in personalized therapeutics.157 Advancements in organ-on-a-chip platforms can be combined with the high-throughput capacity and reproducible drug screening by adding parallel cell encasements and chemical gradients of circulating drugs in a single platform.157 In addition, the creation of micro-tissue models at high structural complexity158 and control over composition will lead to a very functional drug screening platform.159 The authors believe that by harvesting patient tumor cells and placing them into the micro-tissue, it will be possible to precisely reproduce an organotypic model while creating a vascular system using advanced manufacturing,159 clinicians will be able to monitor the behavior of embedded tumor cells and CSCs. This will allow further studies on the role of CSCs and their interactions with drug candidates; thus, it will reveal a new standard in the cancer society.

Acknowledgments

Elvan Dogan, Dr. Asli Kisim, and Dr. Gizem Bati-Ayaz have equal contributions. A.K.M. acknowledges the receipt of R21-DC18818 from the National Institutes of Health, Camden Health Initiative, and Seed Funding from Rowan University. D.P.O. acknowledges the receipt of 1001-119Z109 from The Technological and Scientific Research Council of Turkey. G. Bati-Ayaz acknowledges the receipt of Ph.D. Fellowship from the YOK 100/2000 program. The authors thank all lab members for their valuable feedback and comments on this manuscript. A.K.M. acknowledges Dr. Larry Honaker (Wageningen University, The Netherlands) for his valuable comments and suggestions on the writing.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

Contributor Information

Elvan Dogan, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Rowan University, Glassboro, NJ 08028.

Dr. Asli Kisim, Department of Molecular Biology & Genetics, Izmir Institute of Technology, Gulbahce Kampusu, Urla, Izmir, 35430, Turkey

Dr. Gizem Bati-Ayaz, Biotechnology and Bioengineering, Izmir Institute of Technology, Izmir, Turkey

Dr. Gregory J. Kubicek, Department of Radiation Oncology, MD Anderson Cancer Center at Cooper, 2 Cooper Plaza, Camden, NJ 08103

Prof. Devrim Pesen-Okvur, Department of Molecular Biology & Genetics, Izmir Institute of Technology, Gulbahce Kampusu, Urla, Izmir, 35430, Turkey; Biotechnology and Bioengineering, Izmir Institute of Technology, Izmir, Turkey.

Prof. Amir K. Miri, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Rowan University, Glassboro, NJ 08028; School of Medical Engineering, Science, and Health, Rowan University, Camden, NJ 08103.

References

- 1.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF & Weissman IL Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 414, 105–111, doi: 10.1038/35102167 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan CT, Guzman ML & Noble M Cancer stem cells. New England Journal of Medicine 355, 1253–1261 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang JC Cancer stem cells: Role in tumor growth, recurrence, metastasis, and treatment resistance. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, S20–25, doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000004766 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu H, Fang X, Luo Q & Ouyang G Cancer stem cells: a potential target for cancer therapy. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 72, 3411–3424, doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1920-4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vidal SJ, Rodriguez-Bravo V, Galsky M, Cordon-Cardo C & Domingo-Domenech J Targeting cancer stem cells to suppress acquired chemotherapy resistance. Oncogene 33, 4451–4463, doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.411 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welch DR & Hurst DR Defining the hallmarks of metastasis. Cancer research 79, 3011–3027 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bati-Ayaz G & Pesen-Okvur D Invadopodia: Proteolytic feet of cancer cells. Turkish Journal of Biology 38, 740–747, doi: 10.3906/biy-1404-110 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanahan D & Weinberg RA Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plaks V, Kong N & Werb Z The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell 16, 225–238, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatia SN & Ingber DE Microfluidic organs-on-chips. Nat Biotech 32, 760–772, doi: 10.1038/nbt.2989 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rapp BE in Microfluidics: Modelling, Mechanics and Mathematics (ed Bastian E. Rapp) 3–7 (Elsevier, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Convery N & Gadegaard N 30 years of microfluidics. Micro and Nano Engineering 2, 76–91, doi: 10.1016/j.mne.2019.01.003 (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao SS, Kondapaneni RV & Narkhede AA Bioengineered models to study tumor dormancy. Journal of Biological Engineering 13, 3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araci IE & Brisk P Recent developments in microfluidic large scale integration. Current opinion in biotechnology 25, 60–68 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatia SN & Ingber DE Microfluidic organs-on-chips. Nat Biotechnol 32, 760–772, doi: 10.1038/nbt.2989 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren K, Zhou J & Wu H Materials for microfluidic chip fabrication. Accounts of chemical research 46, 2396–2406 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du G, Fang Q & den Toonder JMJ Microfluidics for cell-based high throughput screening platforms—A review. Analytica Chimica Acta 903, 36–50, doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.11.023 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park S, Zhang Y, Lin S, Wang T-H & Yang S Advances in microfluidic PCR for point-of-care infectious disease diagnostics. Biotechnology advances 29, 830–839 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caballero D, Blackburn SM, de Pablo M, Samitier J & Albertazzi L Tumour-vessel-on-a-chip models for drug delivery. Lab on a Chip 17, 3760–3771, doi: 10.1039/C7LC00574A (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sung JH in Methods in Cell Biology Vol. 146 (eds Junsang Doh, Daniel Fletcher, & Matthieu Piel) 183–197 (Academic Press, 2018).30037461 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang M & Duan B in Encyclopedia of Biomedical Engineering (ed Roger Narayan) 135–152 (Elsevier, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lesher-Pérez SC et al. Dispersible oxygen microsensors map oxygen gradients in three-dimensional cell cultures. Biomaterials science 5, 2106–2113, doi: 10.1039/c7bm00119c (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta G, Hsiao AY, Ingram M, Luker GD & Takayama S Opportunities and challenges for use of tumor spheroids as models to test drug delivery and efficacy. Journal of Controlled Release 164, 192–204, doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.045 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ilhan M et al. Pro-metastatic functions of Notch signaling is mediated by CYR61 in breast cells. European Journal of Cell Biology, 151070 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onal S, Turker-Burhan M, Bati-Ayaz G, Yanik H & Pesen-Okvur D Breast Cancer Cells and Macrophages in a Paracrine-Juxtacrine Loop. bioRxiv, 2020.2006.2016.154294, doi: 10.1101/2020.06.16.154294 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim BJ et al. Cooperative Roles of SDF-1α and EGF Gradients on Tumor Cell Migration Revealed by a Robust 3D Microfluidic Model. PLOS ONE 8, e68422, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068422 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weaver VM et al. Reversion of the Malignant Phenotype of Human Breast Cells in Three-Dimensional Culture and In Vivo by Integrin Blocking Antibodies. Journal of Cell Biology 137, 231–245, doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.231 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada KM & Sixt M Mechanisms of 3D cell migration. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 20, 738–752, doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0172-9 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedl P & Wolf K Plasticity of cell migration: a multiscale tuning model. Journal of Cell Biology 188, 11–19, doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909003 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu W, Holmes B, Glazer RI & Zhang LG 3D printed nanocomposite matrix for the study of breast cancer bone metastasis. Nanomedicine 12, 69–79, doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.09.010 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ridky TW, Chow JM, Wong DJ & Khavari PA Invasive three-dimensional organotypic neoplasia from multiple normal human epithelia. Nature Medicine 16, 1450–1455, doi: 10.1038/nm.2265 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosh S et al. Three-dimensional culture of melanoma cells profoundly affects gene expression profile: A high density oligonucleotide array study. Journal of Cellular Physiology 204, 522–531, doi: 10.1002/jcp.20320 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shield K, Ackland ML, Ahmed N & Rice GE Multicellular spheroids in ovarian cancer metastases: Biology and pathology. Gynecol Oncol 113, 143–148, doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.032 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edmondson R, Broglie JJ, Adcock AF & Yang L Three-dimensional cell culture systems and their applications in drug discovery and cell-based biosensors. Assay and drug development technologies 12, 207–218, doi: 10.1089/adt.2014.573 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breslin S & O’Driscoll L Three-dimensional cell culture: the missing link in drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today 18, 240–249, doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.10.003 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miri AK et al. Bioprinters for organs-on-chips. Biofabrication 11, 042002, doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/ab2798 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mofazzal Jahromi MA et al. Microfluidic Brain-on-a-Chip: Perspectives for Mimicking Neural System Disorders. Mol Neurobiol 56, 8489–8512, doi: 10.1007/s12035-019-01653-2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franco S, S. et al. In vitro models of cancer stem cells and clinical applications. BMC Cancer 16, 738, doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2774-3 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allegra A et al. The Cancer Stem Cell Hypothesis: A Guide to Potential Molecular Targets. Cancer Investigation 32, 470–495, doi: 10.3109/07357907.2014.958231 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ciurea ME et al. Cancer stem cells: biological functions and therapeutically targeting. International journal of molecular sciences 15, 8169–8185, doi: 10.3390/ijms15058169 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vermeulen L et al. Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nat Cell Biol 12, 468–476, doi: 10.1038/ncb2048 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Firatligil-Yildirir B et al. Homing Choices of Breast Cancer Cells Revealed by Tissue Specific Invasion and Extravasation Lab-on-a-chip Platforms. bioRxiv, 2020.2009.2025.312793, doi: 10.1101/2020.09.25.312793 (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gokce B, Akcok I, Cagir A & Pesen-Okvur D A new drug testing platform based on 3D tri-culture in lab-on-a-chip devices. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 155, 105542 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu Q et al. Organ-on-a-chip: recent breakthroughs and future prospects. BioMedical Engineering OnLine 19, 9, doi: 10.1186/s12938-020-0752-0 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van de Stolpe A On the origin and destination of cancer stem cells: a conceptual evaluation. Am J Cancer Res 3, 107–116 (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dick JE Stem cell concepts renew cancer research. Blood 112, 4793–4807, doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-077941 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Afify SM & Seno M Conversion of Stem Cells to Cancer Stem Cells: Undercurrent of Cancer Initiation. Cancers (Basel) 11, doi: 10.3390/cancers11030345 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF & Weissman IL Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 414, 105–111, doi: 10.1038/35102167 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Du S & Barcellos-Hoff MH Tumors as organs: biologically augmenting radiation therapy by inhibiting transforming growth factor β activity in carcinomas. Semin Radiat Oncol 23, 242–251, doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2013.05.001 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.F Quail D, J Taylor M & Postovit L-M Microenvironmental regulation of cancer stem cell phenotypes. Current stem cell research & therapy 7, 197–216 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chaffer CL & Weinberg RA How does multistep tumorigenesis really proceed? Cancer discovery 5, 22–24 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanahan D & Weinberg Robert A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 144, 646–674, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wicha MS, Liu S & Dontu G Cancer stem cells: an old idea--a paradigm shift. Cancer Res 66, 1883–1890; discussion 1895–1886, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-05-3153 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chatterji P, Douchin J & Giroux V Demystifying the Differences Between Tumor-Initiating Cells and Cancer Stem Cells in Colon Cancer. Current Colorectal Cancer Reports 14, 242–250, doi: 10.1007/s11888-018-0421-x (2018). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rahman M et al. Stem cell and cancer stem cell: a tale of two cells. Progress in Stem Cell 3, 97–108 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sleeboom JJF, Eslami Amirabadi H, Nair P, Sahlgren CM & den Toonder JMJ. Metastasis in context: modeling the tumor microenvironment with cancer-on-a-chip approaches. Dis Model Mech 11, doi: 10.1242/dmm.033100 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greenbaum A et al. CXCL12 in early mesenchymal progenitors is required for haematopoietic stem-cell maintenance. Nature 495, 227–230, doi: 10.1038/nature11926 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Najafi M et al. Hypoxia in solid tumors: a key promoter of cancer stem cell (CSC) resistance. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 146, 19–31, doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-03080-1 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stylianopoulos T, Munn LL & Jain RK Reengineering the Physical Microenvironment of Tumors to Improve Drug Delivery and Efficacy: From Mathematical Modeling to Bench to Bedside. Trends Cancer 4, 292–319, doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.02.005 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nair N et al. A cancer stem cell model as the point of origin of cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumor microenvironment. Sci Rep 7, 6838, doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07144-5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klonisch T et al. Cancer stem cell markers in common cancers - therapeutic implications. Trends Mol Med 14, 450–460, doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.08.003 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poleszczuk J, Hahnfeldt P & Enderling H Evolution and Phenotypic Selection of Cancer Stem Cells. PLOS Computational Biology 11, e1004025, doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004025 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen C, Zhao S, Karnad A & Freeman JW The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: therapeutic implications. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 11, 64, doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0605-5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Southam CM & Brunschwig A Quantitative studies of autotransplantation of human cancer. Preliminary report. Cancer 14, 971–978, doi: (1961). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bergsagel DE & Valeriote FA Growth characteristics of a mouse plasma cell tumor. Cancer Res 28, 2187–2196 (1968). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamburger AW & Salmon SE Primary bioassay of human tumor stem cells. Science 197, 461, doi: 10.1126/science.560061 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ozols RF et al. Inhibition of human ovarian cancer colony formation by adriamycin and its major metabolites. Cancer Res 40, 4109–4112 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weisenthal LM & Lippman ME Clonogenic and nonclonogenic in vitro chemosensitivity assays. Cancer Treat Rep 69, 615–632 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al-Hajj M & Clarke MF Self-renewal and solid tumor stem cells. Oncogene 23, 7274–7282, doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207947 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ & Clarke MF Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 3983–3988, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sun H-R et al. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Cancer Stem Cells and Their Microenvironment. Frontiers in Oncology 9, doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01104 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ginestier C et al. Retinoid signaling regulates breast cancer stem cell differentiation. Cell Cycle 8, 3297–3302, doi: 10.4161/cc.8.20.9761 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Afify SM et al. Abstract 3055: A model of CSC converted from iPSC in the conditioned medium of HCC paving the way to establish HCC CSC. Cancer Research 78, 3055–3055, doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.Am2018-3055 (2018). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen L et al. A model of cancer stem cells derived from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One 7, e33544, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033544 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yan T et al. Characterization of cancer stem-like cells derived from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells transformed by tumor-derived extracellular vesicles. J Cancer 5, 572–584, doi: 10.7150/jca.8865 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cruz MH, Sidén A, Calaf GM, Delwar ZM & Yakisich JS The stemness phenotype model. ISRN oncology 2012, 392647–392647, doi: 10.5402/2012/392647 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ajani JA, Song S, Hochster HS & Steinberg IB Cancer stem cells: the promise and the potential. Semin Oncol 42 Suppl 1, S3–17, doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.01.001 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen K, Huang YH & Chen JL Understanding and targeting cancer stem cells: therapeutic implications and challenges. Acta Pharmacol Sin 34, 732–740, doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.27 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Birnie R et al. Gene expression profiling of human prostate cancer stem cells reveals a pro-inflammatory phenotype and the importance of extracellular matrix interactions. Genome Biol 9, R83, doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-r83 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li F, Tiede B, Massagué J & Kang Y Beyond tumorigenesis: cancer stem cells in metastasis. Cell Research 17, 3–14, doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310118 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vermeulen L et al. Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nature Cell Biology 12, 468–476, doi: 10.1038/ncb2048 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moustakas A & Heldin CH Signaling networks guiding epithelial-mesenchymal transitions during embryogenesis and cancer progression. Cancer Sci 98, 1512–1520, doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00550.x (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu S et al. Breast cancer stem cells transition between epithelial and mesenchymal states reflective of their normal counterparts. Stem Cell Reports 2, 78–91, doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.11.009 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang L et al. Gastric cancer stem-like cells possess higher capability of invasion and metastasis in association with a mesenchymal transition phenotype. Cancer Letters 310, 46–52, doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.06.003 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Balic M et al. Most Early Disseminated Cancer Cells Detected in Bone Marrow of Breast Cancer Patients Have a Putative Breast Cancer Stem Cell Phenotype. Clinical Cancer Research 12, 5615, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0169 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carnero A & LLeonart ME The hypoxic microenvironment: A determinant of cancer stem cell evolution. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology 38 Suppl 1, S65–74 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Conley SJ et al. Antiangiogenic agents increase breast cancer stem cells via the generation of tumor hypoxia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 2784, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018866109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kalluri R & Zeisberg M Fibroblasts in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 6, 392–401, doi: 10.1038/nrc1877 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Herrera-Perez M, Voytik-Harbin SL & Rickus JL Extracellular Matrix Properties Regulate the Migratory Response of Glioblastoma Stem Cells in Three-Dimensional Culture. Tissue Eng Part A 21, 2572–2582, doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2014.0504 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Truong D et al. A three-dimensional (3D) organotypic microfluidic model for glioma stem cells - Vascular interactions. Biomaterials 198, 63–77, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.07.048 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dai X, Ma C, Lan Q & Xu T 3D bioprinted glioma stem cells for brain tumor model and applications of drug susceptibility. Biofabrication 8, 045005, doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/8/4/045005 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reynolds DS et al. Breast Cancer Spheroids Reveal a Differential Cancer Stem Cell Response to Chemotherapeutic Treatment. Sci Rep 7, 10382, doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10863-4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lin D et al. Screening Therapeutic Agents Specific to Breast Cancer Stem Cells Using a Microfluidic Single-Cell Clone-Forming Inhibition Assay. Small 16, 1901001, doi: 10.1002/smll.201901001 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Muenzner JK et al. Generation and characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines with enhanced cancer stem cell potential. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 22, 6238–6248, doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13911 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wan S et al. New Labyrinth Microfluidic Device Detects Circulating Tumor Cells Expressing Cancer Stem Cell Marker and Circulating Tumor Microemboli in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Scientific Reports 9, 18575, doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54960-y (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Herreros-Pomares A et al. Lung tumorspheres reveal cancer stem cell-like properties and a score with prognostic impact in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. Cell Death & Disease 10, 660, doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1898-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zou H et al. Microfluidic Platform for Studying Chemotaxis of Adhesive Cells Revealed a Gradient-Dependent Migration and Acceleration of Cancer Stem Cells. Anal Chem 87, 7098–7108, doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00873 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Raghavan S, Mehta P, Xie Y, Lei YL & Mehta G Ovarian cancer stem cells and macrophages reciprocally interact through the WNT pathway to promote pro-tumoral and malignant phenotypes in 3D engineered microenvironments. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 7, 190, doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0666-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Martins-Neves SR et al. Therapeutic implications of an enriched cancer stem-like cell population in a human osteosarcoma cell line. BMC Cancer 12, 139, doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-139 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Langhans SA Three-Dimensional in Vitro Cell Culture Models in Drug Discovery and Drug Repositioning. Frontiers in Pharmacology 9, doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00006 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ho WJ et al. Incorporation of multicellular spheroids into 3-D polymeric scaffolds provides an improved tumor model for screening anticancer drugs. Cancer science 101, 2637–2643 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pampaloni F, Reynaud EG & Stelzer EH The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 8, 839–845 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ham SL, Joshi R, Thakuri PS & Tavana H Liquid-based three-dimensional tumor models for cancer research and drug discovery. Experimental Biology and Medicine 241, 939–954 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stadler M et al. in Seminars in Cancer Biology. 107–124 (Elsevier; ). [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stadler M et al. Increased complexity in carcinomas: Analyzing and modeling the interaction of human cancer cells with their microenvironment. Semin Cancer Biol 35, 107–124, doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.08.007 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fu JJ et al. Spontaneous formation of tumor spheroid on a hydrophilic filter paper for cancer stem cell enrichment. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 174, 426–434, doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.11.038 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yin X et al. Engineering Stem Cell Organoids. Cell Stem Cell 18, 25–38, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.12.005 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tveit KM, Endresen L, Rugstad HE, Fodstad Ø & Pihl A Comparison of two soft-agar methods for assaying chemosensitivity of human tumours in vitro: Malignant melanomas. British Journal of Cancer 44, 539–544, doi: 10.1038/bjc.1981.223 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fiebig HH, Maier A & Burger AM Clonogenic assay with established human tumour xenografts: correlation of in vitro to in vivo activity as a basis for anticancer drug discovery. European Journal of Cancer 40, 802–820, doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.01.009 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sant S & Johnston PA The production of 3D tumor spheroids for cancer drug discovery. Drug Discov Today Technol 23, 27–36, doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2017.03.002 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sutherland RM Cell and environment interactions in tumor microregions: the multicell spheroid model. Science 240, 177–184, doi: 10.1126/science.2451290 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hirschhaeuser F et al. Multicellular tumor spheroids: An underestimated tool is catching up again. Journal of Biotechnology 148, 3–15, doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.01.012 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Weiswald LB, Bellet D & Dangles-Marie V Spherical cancer models in tumor biology. Neoplasia 17, 1–15, doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.12.004 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mehta G, Hsiao AY, Ingram M, Luker GD & Takayama S Opportunities and challenges for use of tumor spheroids as models to test drug delivery and efficacy. J Control Release 164, 192–204, doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.045 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Santo VE et al. Adaptable stirred-tank culture strategies for large scale production of multicellular spheroid-based tumor cell models. J Biotechnol 221, 118–129, doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.01.031 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Curcio E et al. Mass transfer and metabolic reactions in hepatocyte spheroids cultured in rotating wall gas-permeable membrane system. Biomaterials 28, 5487–5497, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.033 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Walenta S, Doetsch J, Mueller-Klieser W & Kunz-Schughart LA Metabolic imaging in multicellular spheroids of oncogene-transfected fibroblasts. J Histochem Cytochem 48, 509–522, doi: 10.1177/002215540004800409 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ruppen J et al. A microfluidic platform for chemoresistive testing of multicellular pleural cancer spheroids. Lab Chip 14, 1198–1205, doi: 10.1039/c3lc51093j (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.He J et al. 3D modeling of cancer stem cell niche. Oncotarget 9, 1326–1345, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19847 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kondo J et al. Retaining cell-cell contact enables preparation and culture of spheroids composed of pure primary cancer cells from colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 6235–6240, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015938108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Xu C et al. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nature Biotechnology 19, 971–974, doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-971 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lancaster MA & Knoblich JA Organogenesis in a dish: Modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science 345, 1247125, doi: 10.1126/science.1247125 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]