Abstract

Objective:

To prospectively evaluate the impact of a multidisciplinary lymphoma virtual tumor board.

Background:

The utility of multi-site interactive lymphoma-specific tumor boards has not been reported. The Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Tumor Board is a component of the International Mayo Clinic Care Network (MCCN). The format includes the clinical case presentation, presentation of radiology and hematopathology findings by the appropriate subspecialist, proposed treatment options, review of the literature pertinent to the case, pharmacy contributions, and discussion followed by recommendations.

Patients and Methods:

309 consecutive highly selected real-time cases with a diagnosis of lymphoma were presented at the Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Tumor Board from January 2014 to June 2018 and decisions were prospectively tracked to assess its impact on the treatment decisions.

Results:

A total of 309 cases were prospectively evaluated. 140 (45.3%) cases had some changes made or recommended. The total changes suggested were 179, as some cases had more than one recommendation. There were 93 (30%) clinical management recommendations, 45 (14.6%) additional testing recommendations, 29 (9.4%) pathology changes, and 6 (1.9%) radiology changes. In an electronic evaluation process, 93% of the responders reported an improvement in knowledge and competence, and 100% recommended no change in format of the board.

Conclusion:

A multidisciplinary lymphoma tumor board approach was found to have a meaningful impact on lymphoma patients while enhancing interdisciplinary interactions and education for multiple levels of the clinical care team.

Introduction:

Management of cancer patients is becoming increasingly complex with ongoing advances in drug development, diagnostic approaches, local therapy options, emerging clinical data from multiple trials and constantly evolving clinical practices and guidelines. Furthermore, a wide range of health-care professionals involved in patient care creates room for miscommunication and arduous care coordination issues. Multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) or tumor boards are commonly conducted in oncology to implement evidence-based recommendations, providing opinions for complex cases, and conducting patient-centered care in a time-effective manner by bringing various specialists together.1 MDT based care is becoming a standard practice worldwide. Typical method entails a description of the patient’s presentation, a review of relevant radiologic and histopathologic data, and then a discussion of treatment strategies by relevant disciplines. Several single-center studies have investigated the impact of an MDT based approach in various solid tumor malignancies.2,3 Effective implementation of MDT requires a regular schedule and a team comprising of medical hematology-oncology, radiation oncology, pathology, radiology, and surgical specialists. Depending on the tumor type and institutional setting, tumor boards may also include palliative medicine, research coordinators, clinical research nurses and pharmacists with each providing their unique inputs based on circumstance.4 The American College of Surgeon’s Commission on Cancer Program accreditation, in fact, requires cancer programs to have multidisciplinary cancer conference that routinely reviews cases and discusses management options.6 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) also promotes tumor boards that are integrated into multidisciplinary cancer management courses. Attendees of these courses, especially in the middle- and low-income countries, have reported starting new MDT based patient approach in their own countries.7

Evaluation of the impact of MDTs for cancer patients suggest changes made to staging/diagnosis, management plans, higher rates of surgical resection, and adherence to evidence-based guidelines.8,9,10,11,12 While some show an overall improvement in meaningful patient outcomes, including survival, other more extensive studies contradict this observation.13,14,15,16,3 MDTs are resource-intensive and thus it is essential to assess their impact. It is an arduous and complicated task which is currently under debate. It requires incorporation of measures of structure, adherence to recommendations, processes to provide feedback and to assess the patient-reported quality of care.17 Solid tumors such as lung, breast, and colon cancer have MDTs established more commonly, while hematologic malignancies are either discussed in general tumor boards or have disease-specific tumor boards in larger academic centers. A systematic review conducted by Pillay et al. evaluated the impact of MDTs on patient assessment, management, and patient outcomes, screened 1067 articles of which 27 met the inclusion criteria. Of these only two studies recruited patients with a range of oncologic diagnosis, the remainder were specific to solid tumors only.3 Lymphoma-specific tumor board outcomes have not been reported in recent years. In addition, the utility of multi-site, interactive tumor boards using videoconference technology is not widely reported. We prospectively evaluated the outcomes of a multidisciplinary multi-site lymphoma tumor board that included a change in the revision of the World Health Organization Classification first published in 2016, new genomic observations, and reports of new therapeutic interventions.18

PATIENTS AND METHODS

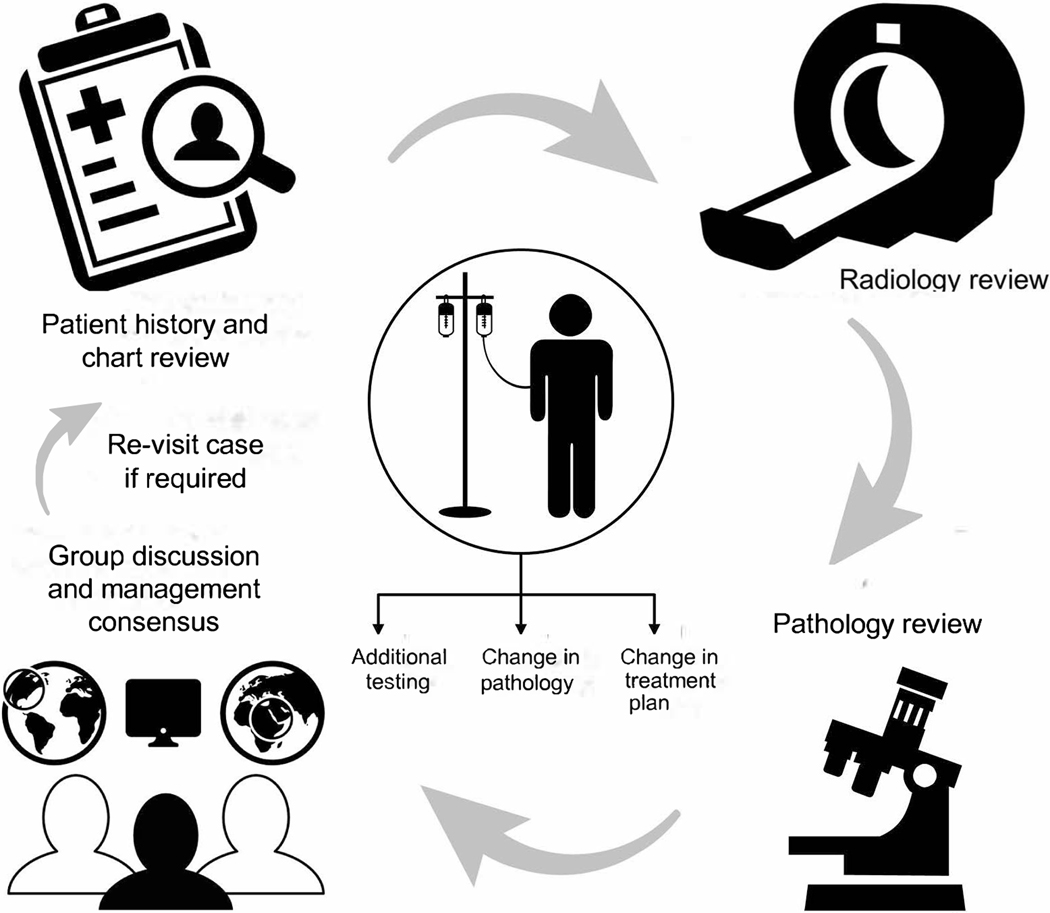

The Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Tumor Board is a component of the International Mayo Clinic Care Network (MCCN). This comprises of over 40 hospitals both nationally and internationally. The format is comprised of a clinical case presentation, radiology review of images, presentation of hematopathology findings by the appropriate subspecialist, proposed treatment options, review of the literature pertinent to the case, discussion and recommendations (see Figure 1). The requirement for presentation involved having an established or suspected diagnosis of lymphoma with pathology reviewed at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN (MCR). Relevant pathology and radiology materials were required to be reviewed at MCR and presented by MCR hematopathologists and radiologists. Patients were presented prospectively with active clinical issues or questions to be addressed. Four cases were presented at each 60-minute meeting. Case selection was based on the managing physicians’ discretion both from MCR, and its affiliate centers when there was a clinical question that needed to be addressed. This could be related to clinical management such as next treatment of choice, exploring clinical trial possibilities when all the approved or standard treatment options had been exhausted, confirmation or clarification of the diagnosis, or discussion and management of unusual patient presentation. The referring physicians were provided the knowledge that at least 2 weeks was required for acquisition and review of the pathology material and radiological images. We ensured that the managing physicians were aware of this requirement via email notifications that were sent out once a week for request of cases so as not to delay patient care where urgent management was needed. Meeting was conducted every 2 weeks except for holidays, and during annual hematology-oncology meetings such as American Society of Hematology, and ASCO when the staff is limited.

Figure 1.

Illustration depicting the workflow of our multidisciplinary tumor board meeting.

309 consecutive highly selected cases with an established or suspected diagnosis of lymphoma at the Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Tumor Board were presented from 2014 to 2018. The pathology material was independently reviewed by the presenting hematopathologists and radiology material by the presenting radiologist. Participants outside of Mayo Clinic were office-based or hospital-based, and included multiple members of the health care team which included pharmacists, clinical research associates, and physicians-in-training. Recommendations were prospectively tracked for changes in radiology interpretation, pathologic diagnosis, and treatment approaches. Actual follow-up of all patients after the meeting was not allowed in the MCCN; therefore, the data on actual patient treatment and survival is not available. Participation in the meeting was either via in-room attendance at MCR, video conference at a participating MCCN site, or via non-participatory live-stream online. Video was available internally for fourteen days for review. Approval for this study was obtained from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. To acquire feedback from the participants, an anonymous online survey was conducted annually from 2017 onwards.

RESULTS

A total of 309 cases were presented from January 2014 to June 2018. 258 (83%) cases were from MCR, and 51 (17%) were not physically evaluated at MCR. Sixteen cases were presented at a subsequent meeting for further recommendations in the course of their disease after the initial presentation and discussion. Cases presented included a mix of new diagnosis, relapsed and refractory disease. 45% (140/309) of the cases presented had changes in some aspect of their care resulting in a total of 179 overall changes owing to the MDTs discussions. Clinical management changes comprised 30% (n = 93) of the changes, 14.6% (n = 45) for additional testing recommendations, 9.4% (n = 29) had pathology changes, and 1.9% (n = 6) had radiology changes (see Table 1). Of the cases that required change in care, 68.5% (n = 96) were newly diagnosed and 31.5% (n = 44) had relapsed/refractory disease (Figure 2). The clinical management changes suggested included one systemic treatment to another regimen, change in diagnosis based on the pathology review, both change in diagnosis based on pathology review and change in systemic treatment, the recommendaton of autologous stem cell transplant for consolidation and the addition of radiation to the systemic treatment (see Table 2).

Table 1:

Categories of changes recommended based on tumor board discussion.

| Category | Number | % of 309 Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Radiologic Interpretation | 6 | 1.9% |

| Pathologic Diagnosis | 29 | 9.4% |

| Additional testing Recommended | 45 | 14.6% |

| Clinical Management | 93 | 30% |

No consensus was reached: 6 (1.9%)

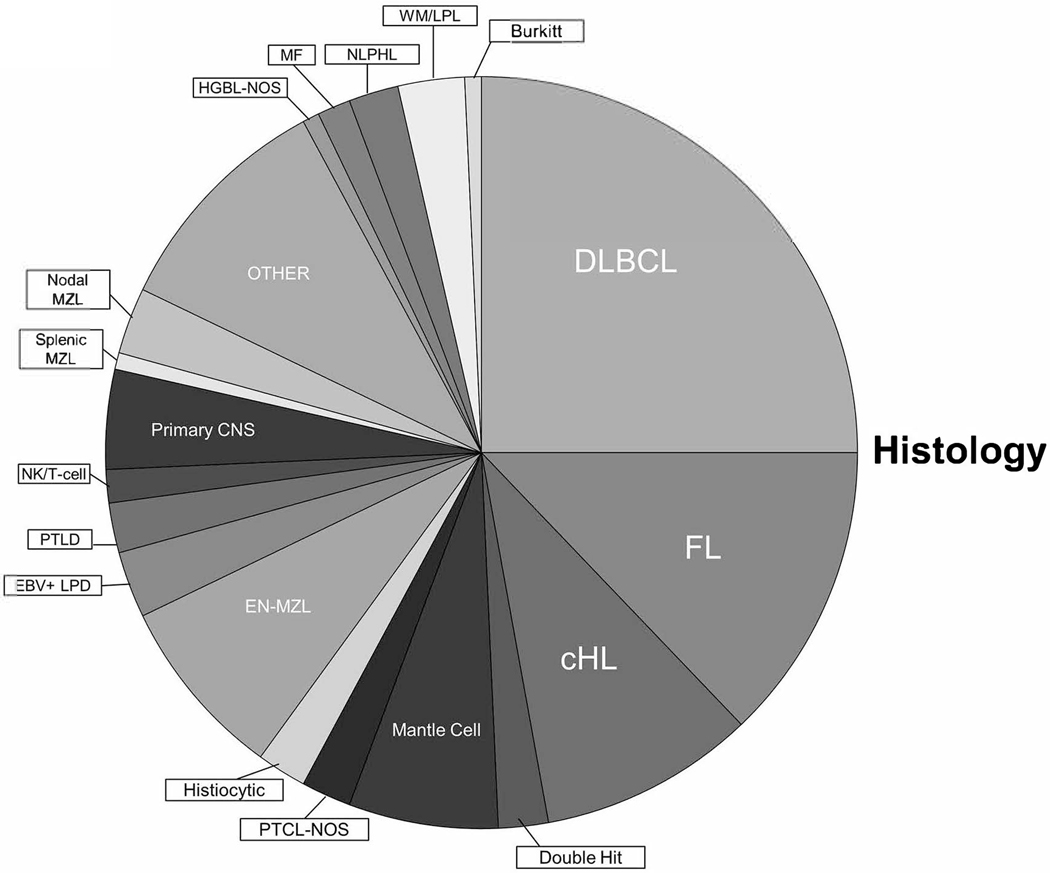

Figure 2.

Pie chart showing distribution of various lymphoma types presented in the lymphoma tumor board during the study period.

Table 2:

Different types of clinical management changes suggested during tumor board discussion

| Category | Number | % of 309 Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic treatment to different systemic treatment | 11 | 3.6% |

| Pathology Change with No Change in Management | 11 | 3.6% |

| Pathology Change with Treatment Change | 11 | 3.6% |

| Systemic Treatment Alone to Systemic Treatment Plus Radiation Therapy | 5 | 1.6% |

| Observation to More Testing | 7 | 2.3% |

| Systemic Treatment to Autologous Stem Cell Rescue | 5 | 1.6% |

| Other | 43 | 14% |

Various lymphoma types were discussed over this time period (Figure 3). Of these, the most common was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), followed by follicular lymphoma (FL). We further categorized the cases presented based on year and classification, which demonstrates the diversity of cases presented (see Table 3). Average site in-room average attendance (internal/external) was 16.8/8.6. The non-participatory live-stream presence was not possible to track.

Table 3:

Different case diagnoses discussed with changes suggested from 2014–2018 based on lymphoma classification and disease status (new vs. relapsed/refractory disease)

| Year | Number of Cases with change | Lymphoma classification | New/Relapsed diagnosis | Site of origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 10 | DLBCL- 3 FL- 3 cHL – 1 Mantle cell – 1 PTCL NOS – 1 Histiocytic disorder – 1 |

New – 4 Relapsed/Refractory - 6 |

MCR – 7 Outside - 3 |

| 2015 | 34 | DLBCL – 9 EN- MZL – 5 FL – 2 cHL – 3 High-grade B cell- DHT – 2 EBV + LPD – 2 PTCL NOS – 1 PTLD – 2 NK/T Cell, nasal type – 1 Primary CNS – 1 Splenic MZL – 1 Nodal MZL – 1 Mantle cell - 1 Other - 3 |

New - 23 Relapsed/Refractory - 11 |

MCR - 30 Outside - 4 |

| 2016 | 33 | DLBCL – 8 Mantle cell – 4 FL – 3 Primary CNS – 2 Other – 3 High-grade B cell NOS – 1 MF with large cell trans – 1 EN – MZL – 1 cHL – 1 HGBL – DHT – 1 EBV+ LPD – 1 Histiocytic disorder – 1 Nodal MZL – 3 NLPHL – 1 WM/LPL - 2 |

New – 23 Relapsed/Refractory - 10 |

MCR – 22 Ouside 11 |

| 2017 | 42 | DLBCL – 10 cHL – 6 FL – 6 Other – 6 EN – MZL – 3 Primary CNS – 2 Mantle cell – 2 Burkitt’s – 1 PTCL NOS – 1 Mycosis fungoides – 1 Histiocytic disorder – 1 PTLD – 1 NLPHL – 1 WM/LPL - 1 |

New – 30 Relapsed/Refractory - 12 |

MCR-30 Outside −12 |

| 2018 | 21 | DLBCL – 5 FL – 4 cHL – 2 EN MZL – 2 Other – 2 NLPHL – 1 Primary CNS – 1 Mantle cell – 1 WM/LPL – 1 EBV + LPD – 1 NK/T- cell, nasal - 1 |

New – 16 Relapsed/Refractory - 5 |

MCR – 17 Outside - 4 |

Abbreviations: DLBCL – Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL- Follicular lymphoma; cHL- classical hodgkin’s lymphoma; PTCL-NOS – Peripheral T-cell lymphoma- not otherwise specified; EN-MZL – Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma; EBV+ LPD – EBV+ lymphoproliferative disorder; PTLD – post transplant lymphoproliferative disorder; HGBL NOS – High grade B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified; MF- mycosis fungoides; NLPHL – nodular lymphocyte predominant hodgkin’s lymphoma; WM/LPL – waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia/lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma

To evaluate the MTDs further, annual feedback surveys were incorporated in 2017. Anonymous online surveys were sent out to gauge the perception of the participants and to attain any feedback for improvement in the team structure, process, and outcomes. This was a 15-questions online survey which was distributed to all the attendees of the MDTs including clinicians, nurse practitioners, research staff, clinical nursing staff, and learners (lymphoma and general hematology-oncology fellows). On a 5-point rating scale, overall activity was rated excellent by 100% of participants both in 2017 and 2018. All participants responded that the objectives of the meeting were met, the tumor board was free of commercial bias, and that appropriate references and teaching slides were included for educational purposes. 93% of attendees perceived improvement in their overall knowledge, competence, performance, and patient outcomes (see Figure 4). 100% recommended no changes to the format of the conference. Optional fields were left in the survey to obtain general comments for feedback. Based on the feedback provided, enhancements over time included Continuous Medical Education (CME) credit, an in-room microscope, and real-time radiology images.

DISCUSSION

The disease-specific histology-based tumor board provided for a rich, in-depth review of the full context of the patient’s care that included regional and international input. The review of the history, physical examination, radiology findings, pathology findings, unique aspects of the individual case resulted in changes and recommendations in 45% of patients. The environment provides for broad educational opportunities and participation for all involved including individuals at different aspects of training; visiting fellows, pharmacists, clinical research associates involved in the University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) program and the Lymphoma Epidemiology Outcomes (LEO) Consortium. New data from studies from these federally funded grants were included regularly into the discussion, applied to cases and incorporated into clinical decisions. Therapeutic options were vetted, including level of evidence supporting different treatment approaches, comorbidities, dosing considerations in hepatic or renal insufficiency, blood brain barrier access, drug-drug interactions, patient’s access to therapy and pharmaco-economic impact in the presence of a multi-disciplinary team to determine the optimal diagnosis and most effective and appropriate treatment approaches.

Several single centers have investigated the impact of MDTs on patient outcomes. Between 4 and 45% of patients with malignancies discussed at MDTs experience changes in the diagnosis or staging (including pathologic grade, the primary site of the tumor, histology, and extent of disease spread).3, 19, 20 Brannstrom et al. reported that rectal cancer patients discussed in MDT meetings had complete pre-operative staging in 96% of the cases compared to 63% not presented.21 Similar studies in other solid tumors (esophageal, lung, gynecological and prostate) suggest more accurate and complete staging and changes in surgical strategies after discussion in MDTs.22,23,24 Recommendations for chemotherapy, radiation, and surgical resection were also reported to be impacted. Prospective and retrospective studies reported changes in the management plan in the range of 4.5–52% of cases.25,26,8,27 Newman et al. showed that 17% of management plans changed in breast cancer patients due to review of pathology and radiology, as compared to 34% made only based on the discussion in MDT.28 Additional testing and consultations ordered after case review in MDT meeting have been reported.29 More patients received neo-adjuvant or adjuvant treatments, and even had more downstaging of their tumors, resulting in curative surgeries.16,24,30,21 Greater adherence to clinical practice guidelines was noted in MDTs based care, along with fewer mean days from diagnosis to treatment and increased referral to palliative care.24,31 Similar to the mentioned data, our study highlights changes in all aspects of care in the lymphoma patients presented which has not been previously described. About 45% of patients had changes in their management after discussion in this virtual tumor board. Our lymphoma MDT’s construct is unique in that it also included cases from low volume centers and was both regional and international. In concert with this, our format also necessitated a review of literature or evidence-based guidelines in a powerpoint based presentation with the goal of education for all the team members. The specifics of change in management included the transition from one systemic treatment to another, the incorporation of radiation therapy, the recommendation for transplant or cell therapy approaches and change in pathological diagnosis leading to change in systemic treatment. Since the cases were selected and likely more complex it provided for an exceptional environment which had an educational impact on all involved especially the learners. Further more, when the cases are challenging to diagnose, have rare presentations or issues in management not commonly encountered in daily practice, it generates enthusiasm to learn. Tumor boards are usually implemented in one of two ways. First, all patients with a new diagnosis of a particular malignancy are discussed or second, only selected, more complex, and high-yield cases are presented. MDTs provide second or expert opinion regarding complex cases and potentially screen patients for clinical trial enrollment. MDTs also provide evidence-based recommendations to satellite sites or lower volume centers through virtual tumor boards or a venue for education regarding new developments and guidelines for tumor type. We chose to implement our MDT in the latter manner for 2 reasons. One this provided more educational value to the participants, and two it gave the opportunity to the lower volume centers to discuss their most complex cases at such a venue and seek expert opinion. This process has demonstrated that three to four cases can be presented efficiently with appropriate discussion resulting in recommendations within 60 minutes with respect to the time of all participants. These cases were also generalizable since they represented genuine questions in the diagnosis, complications and management of lymphoma that are encountered by physicians routinely in practice. Lymphomas are a heterogenous group of disorders, and the variety of the cases discussed in the tumor board is consistent with the prevalence of various lymphoma types in the United States. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma were the most common lymphoma types that were discussed

Change in the management can be attributed to a certain extent to the emergence of new data from clinical trials. For instance, in Hodgkin lymphoma, clinical trial results emerged over our study period for both limited-stage disease and advanced-stage disease. In limited-stage disease, the German Hodgkin Study Group had reported a 90% disease-free survival with ABVD (Adriamycin, bleomycin, Velban®, and DTIC) for two cycles followed by 20Gy radiation therapy.32 The UK RAPID trial randomized negative PET patients after three cycles of ABVD to 20Gy radiation therapy versus observation and despite not being able to show non-inferiority of the observation approach, showed very good outcomes in PET negative cohort.33 In advanced-stage disease, PET-based de-escalation of bleomycin chemotherapy to mitigate pulmonary toxicity was adopted based on results from RATHL study.34 New laboratory assessments such as the TP53 mutation status in mantle cell lymphoma were routinely incorporated in our laboratory after a tumor board presentation.35 New understanding of the natural history of follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and other subtypes were incorporated.36,37,38,39,40,41,42 New insights into treatment approaches, unusual lymphomas, rare presentations and management, the influence of physical activity, new biology and therapeutic approaches were reviewed.43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51 National and Mayo Clinic practice guidelines were incorporated into the discussions as many of these expert participants serve on the panel of these guidelines.52,53,54,55

Effects of MDT based care on patient outcomes such as survival is complex. Several single-institution studies support its benefit, and positive impact, however larger studies and systematic reviews challenge this notion.3,16 Keating et al. expanded the evaluation to a large integrated health system, the Veterans Health Administration (VA). They surveyed all of the 138 VA medical centers on the availability of MDTs for discussion of patients diagnosed in 2001–2004. The study inferred that the mere existence of tumor boards did not correlate with improvement in survival outcome measures.16 There was also little association between the MDTs and measures of utilization and quality of care. While several limitations of this study were emphasized after its publication, the authors stated their research did not imply that tumor boards had no benefits. Furthermore, it was suggested that tumor boards might provide limited benefit when performance is assessed using general measures of guideline-recommended care, but may be helpful to more complex patients. It also may be necessary for centers with limited resources and a low volume of physicians. Extensive debates since then have contemplated changing the tumor board conduct and improving measures of structure, process, and outcomes of tumor boards.17 A limitation of our study is that it did not allow for follow-up on the implementation of recommendations or assess survival metrics for patients. In addition, the majority of patients returned to their local facilities for treatment and detailed follow-up is not available. On the other hand, a strength of our tumor board is that there was representation from lower volume centers (17% of the cases presented were from outside MCR).

Process adherence measures are designed to predict future outcomes after the application of the process. The association between process adherence and better outcomes is yet to be proven in oncologic settings. Data remain scarce on actual adherence of the recommendations from the MDTs and its impact on outcomes. One study suggested that MDT consensus may be perceived as a validation of management plan even if no changes are made.29 While we did not assess whether or not the recommendations made during MDTs were implemented or not, feedback on the conduct of our MDT meetings was obtained and changes were implemented. Participants in the online survey consistently reported the incorporation of evidence-based guidelines, significant improvement in knowledge of the most updated treatment strategies, change in treatment plans due to discussion in MDTs improved and efficient communication between clinicians, increased clinical trial participation evaluations and improved professional relationships between all team members (Figure 4).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our study assessed a selected group of real-time suspected or established lymphoma cases from multiple sites over four and one-half years, and noted new recommendations made in 45% of the cases presented. A multidisciplinary lymphoma tumor board approach was of value and substantially enhanced interdisciplinary interactions and education at multiple levels of clinical care. Lower volume centers benefitted from re-review of diagnosis and radiologic data, along with recommendations on most complex and rare diagnoses, and discussion of emerging data. Cost and time-effectiveness of MDTs are issues which may be overcome by selecting particularly controversial and complex cases for discussion rather than all new diagnoses as in our study. Future directions consist of appraising the impact of our MDT on patient outcomes, quality of life and experience, and process adherence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support: Supported by National Health Grants No. P50-CA97274 and U01-CA195568.

Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- MDTs

Multidisciplinary teams

- MCR

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

- MCCN

Mayo Clinic Care Network

- DLBCL

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- FL

follicular lymphoma

- CME

Continuous Medical Education

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest in submitting this article for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taylor C, Munro AJ, Glynne-Jones R, et al. Multidisciplinary team working in cancer: what is the evidence? BMJ. 2010;340:c951. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Kahn KL, Gray SW, Chen AB, Keating NL. Tumor Board Participation Among Physicians Caring for Patients With Lung or Colorectal Cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):e267–e278. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.003673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pillay B, Wootten AC, Crowe H, et al. The impact of multidisciplinary team meetings on patient assessment, management and outcomes in oncology settings: A systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;42:56–72. doi: 10.1016/J.CTRV.2015.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright FC, De Vito C, Langer B, Hunter A. Multidisciplinary cancer conferences: A systematic review and development of practice standards. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(6):1002–1010. doi: 10.1016/J.EJCA.2007.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryce AH, Egan JB, Borad MJ, et al. Experience with precision genomics and tumor board, indicates frequent target identification, but barriers to delivery. Oncotarget. 2017;8(16):27145–27154. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cancer Program Standards (2016 Edition). https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/standards. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- 7.Multidisciplinary Cancer Management Courses (MCMC) | ASCO. https://www.asco.org/international-programs/international-meetings-educational-opportunities/multidisciplinary-cancer. Accessed September 20, 2019.

- 8.Sundi D, Cohen JE, Cole AP, et al. Establishment of a new prostate cancer multidisciplinary clinic: Format and initial experience. Prostate. 2015;75(2):191–199. doi: 10.1002/pros.22904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pawlik TM, Laheru D, Hruban RH, et al. Evaluating the Impact of a Single-Day Multidisciplinary Clinic on the Management of Pancreatic Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(8):2081–2088. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9929-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forrest L, McMillan D, … CM-B journal of, 2005. undefined. An evaluation of the impact of a multidisciplinary team, in a single centre, on treatment and survival in patients with inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. nature.com. https://www.nature.com/articles/6602825. Accessed September 18, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Tyler KH, Haverkos BM, Hastings J, et al. The Role of an Integrated Multidisciplinary Clinic in the Management of Patients with Cutaneous Lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2015;5:136. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korman H, Lanni T, Shah C, et al. Impact of a Prostate Multidisciplinary Clinic Program on Patient Treatment Decisions and on Adherence to NCCN Guidelines. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36(2):121–125. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318243708f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yopp AC, Mansour JC, Beg MS, et al. Establishment of a Multidisciplinary Hepatocellular Carcinoma Clinic is Associated with Improved Clinical Outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(4):1287–1295. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3413-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lordan JT, Karanjia ND, Quiney N, Fawcett WJ, Worthington TR. A 10-year study of outcome following hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases – The effect of evaluation in a multidisciplinary team setting. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35(3):302–306. doi: 10.1016/J.EJSO.2008.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephens MR, Lewis WG, Brewster AE, et al. Multidisciplinary team management is associated with improved outcomes after surgery for esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19(3):164–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, Bozeman SR, Shulman LN, McNeil BJ. Tumor Boards and the Quality of Cancer Care. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(2):113–121. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blayney DW. Tumor Boards (Team Huddles) Aren’t Enough to Reach the Goal. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(2):82–84. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–2390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen P, Tan AL, Penman A. The multidisciplinary tumor conference in gynecologic oncology-does it alter management? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(9):1470–1472. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181bf82df [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang JH, Vines E, Bertsch H, et al. The impact of a multidisciplinary breast cancer center on recommendations for patient management: The university of Pennsylvania experience. Cancer. 2001;91(7):1231–1237. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brännström F, Bjerregaard JK, Winbladh A, et al. Multidisciplinary team conferences promote treatment according to guidelines in rectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(4):447–453. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.952387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wille-Jørgensen P, Sparre P, Glenthøj A, et al. Result of the implementation of multidisciplinary teams in rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(4):410–413. doi: 10.1111/codi.12013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davies AR, Deans DAC, Penman I, et al. The multidisciplinary team meeting improves staging accuracy and treatment selection for gastro-esophageal cancer. Dis esophagus Off J Int Soc Dis Esophagus. 2006;19(6):496–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00629.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman RK, Van Woerkom JM, Vyverberg A, Ascioti AJ. The effect of a multidisciplinary thoracic malignancy conference on the treatment of patients with lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.01.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wheless SA, McKinney KA, Zanation AM. A prospective study of the clinical impact of a multidisciplinary head and neck tumor board. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2010;143(5):650–654. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Hagen P, Spaander MCW, van der Gaast A, et al. Impact of a multidisciplinary tumour board meeting for upper-GI malignancies on clinical decision making: a prospective cohort study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18(2):214–219. doi: 10.1007/s10147-011-0362-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gatcliffe T, Coleman R. Tumor Board: More Than Treatment Planning—A 1-Year Prospective Survey. J Cancer Educ. 2008;23(4):235–237. doi: 10.1080/08858190802189014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newman EA, Guest AB, Helvie MA, et al. Changes in surgical management resulting from case review at a breast cancer multldisciplinary tumor board. Cancer. 2006;107(10):2346–2351. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao K, Manya K, Azad A, et al. Uro-oncology multidisciplinary meetings at an Australian tertiary referral centre--impact on clinical decision-making and implications for patient inclusion. BJU Int. 2014;114 Suppl 1:50–54. doi: 10.1111/bju.12764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer G, Martling A, Cedermark B, Holm T. Preoperative tumour staging with multidisciplinary team assessment improves the outcome in locally advanced primary rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(12):1361–1369. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02460.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freeman RK, Ascioti AJ, Dake M, Mahidhara RS. The effects of a multidisciplinary care conference on the quality and cost of care for lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(5):1834–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasse S, Bröckelmann PJ, Goergen H, et al. Long-term follow-up of contemporary treatment in early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma: Updated analyses of the German Hodgkin Study Group HD7, HD8, HD10, and HD11 trials. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(18):1999–2007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.9410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radford J, Illidge T, Counsell N, et al. Results of a trial of PET-directed therapy for early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1598–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson P, Federico M, Kirkwood A, et al. Adapted treatment guided by interim PET-CT scan in advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(25):2419–2429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eskelund CW, Dahl C, Hansen JW, et al. TP53 mutations identify younger mantle cell lymphoma patients who do not benefit from intensive chemoimmunotherapy. Blood. 2017;130(17):1903–1910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-779736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarkozy C, Maurer MJ, Link BK, et al. Cause of Death in Follicular Lymphoma in the First Decade of the Rituximab Era: A Pooled Analysis of French and US Cohorts. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(2):144–152. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bachy E, Maurer MJ, Habermann TM, et al. A simplified scoring system in de novo follicular lymphoma treated initially with immunochemotherapy. Blood. 2018;132(1):49–58. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-11-816405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maurer MJ, Bachy E, Ghesquières H, et al. Early event status informs subsequent outcome in newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(11):1096–1101. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maurer MJ, Ghesquières H, Jais JP, et al. Event-free survival at 24 months is a robust end point for disease-related outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(10):1066–1073. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.5866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maurer MJ, Jais J-P, Ghesquières H, et al. Personalized risk prediction for event-free survival at 24 months in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(2):179–184. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maurer MJ, Habermann TM, Shi Q, et al. Progression-free survival at 24 months (PFS24) and subsequent outcome for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) enrolled on randomized clinical trials. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2018;29(8):1822–1827. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farooq U, Maurer MJ, Thompson CA, et al. Clinical heterogeneity of diffuse large B cell lymphoma following failure of front-line immunochemotherapy. Br J Haematol. 2017;179(1):50–60. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kahl BS, Hong F, Williams ME, et al. Rituximab extended schedule or re-treatment trial for low-tumor burden follicular lymphoma: Eastern cooperative oncology group protocol E4402. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(28):3096–3102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.5853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Advani RH, Hong F, Fisher RI, et al. Randomized Phase III Trial Comparing ABVD Plus Radiotherapy With the Stanford V Regimen in Patients With Stages I or II Locally Extensive, Bulky Mediastinal Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Subset Analysis of the North American Intergroup E2496 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1936–1942. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.8138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordon LI, Hong F, Fisher RI, et al. Randomized phase III trial ofabvdversus stanfordvwith or without radiation therapy in locally extensive and advanced-stage hodgkin lymphoma: An intergroup study coordinated by the eastern cooperative oncology group (E2496). J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(6):684–691. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.4803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dierickx D, Habermann TM. Post-Transplantation Lymphoproliferative Disorders in Adults. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):549–562. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1702693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kenderian SS, Habermann TM, Macon WR, et al. Large B-cell transformation in nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma: 40-year experience from a single institution. Blood. 2016;127(16):1960–1966. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-665505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evens AM, Advani R, Press OW, et al. Lymphoma occurring during pregnancy: antenatal therapy, complications, and maternal survival in a multicenter analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(32):4132–4139. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.8220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pophali PA, Ip A, Larson MC, et al. The association of physical activity before and after lymphoma diagnosis with survival outcomes. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(12):1543–1550. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McPhail ED, Maurer MJ, Macon WR, et al. Inferior survival in high-grade B-cell lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements is not associated with MYC/IG gene rearrangements. Haematologica. 2018;103(11):1899–1907. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.190157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chapuy B, Stewart C, Dunford AJ, et al. Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B cell lymphoma are associated with distinct pathogenic mechanisms and outcomes. Nat Med. 2018;24(5):679–690. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0016-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zelenetz AD, Gordon LI, Abramson JS, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: B-Cell Lymphomas, Version 3.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(6):650–661. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zelenetz AD, Gordon LI, Wierda WG, et al. Diffuse large b-cell lymphoma version 1.2016: Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. JNCCN J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2016;14(2):196–231. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horwitz SM, Zelenetz AD, Gordon LI, et al. NCCN Guidelines® insights: Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, version 3.2016 featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. JNCCN J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2016;14(9):1067–1079. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kapoor P, Ansell SM, Fonseca R, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Waldenström Macroglobulinemia: Mayo Stratification of Macroglobulinemia and Risk-Adapted Therapy (mSMART) Guidelines 2016. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(9):1257–1265. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.