Abstract

Background

Influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) against a spectrum of severe disease, including critical illness and death, remains poorly characterized.

Methods

We conducted a test-negative study in an intensive care unit (ICU) network at 10 US hospitals to evaluate VE for preventing influenza-associated severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) during the 2019–2020 season, which was characterized by circulation of drifted A/H1N1 and B-lineage viruses. Cases were adults hospitalized in the ICU and a targeted number outside the ICU (to capture a spectrum of severity) with laboratory-confirmed, influenza-associated SARI. Test-negative controls were frequency-matched based on hospital, timing of admission, and care location (ICU vs non-ICU). Estimates were adjusted for age, comorbidities, and other confounders.

Results

Among 638 patients, the median (interquartile) age was 57 (44–68) years; 286 (44.8%) patients were treated in the ICU and 42 (6.6%) died during hospitalization. Forty-five percent of cases and 61% of controls were vaccinated, which resulted in an overall VE of 32% (95% CI: 2–53%), including 28% (−9% to 52%) against influenza A and 52% (13–74%) against influenza B. VE was higher in adults 18–49 years old (62%; 95% CI: 27–81%) than those aged 50–64 years (20%; −48% to 57%) and ≥65 years old (−3%; 95% CI: −97% to 46%) (P = .0789 for interaction). VE was significantly higher against influenza-associated death (80%; 95% CI: 4–96%) than nonfatal influenza illness.

Conclusions

During a season with drifted viruses, vaccination reduced severe influenza-associated illness among adults by 32%. VE was high among young adults.

Keywords: influenza, vaccine effectiveness, critical illness, vaccination, immunization

During the 2019–2020 influenza season, characterized by circulation of drifted viruses with limited antigenic similarity to administered vaccines, influenza vaccination was moderately effective in preventing severe influenza disease, with 32% vaccine effectiveness in this multicenter study in the United States.

In the United States, influenza vaccination is recommended annually for everyone at least 6 months old without a contraindication to vaccination [1–3]. Because influenza viruses continue to evolve, influenza disease burden and the effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccination vary from season to season [4]. Prior studies have consistently demonstrated the effectiveness of influenza vaccination for preventing influenza infection among ambulatory and hospitalized patients [3, 5–8]. Previous reports from small studies suggest that seasonal influenza vaccination may provide greater protection against intensive care unit (ICU) admissions than non-ICU hospital admissions, as well as shorten the length of ICU stay [9–11]. However, the effectiveness of influenza vaccination for preventing the most severe manifestations of influenza infection remains poorly characterized.

The 2019–2020 US influenza season started earlier than usual, was severe, and was characterized by intense early circulation of influenza B-Victoria lineage viruses, with cocirculation of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses [12, 13]. Studies have reported limited antigenic similarity (ie, “drift”) between the seasonal vaccine viruses used during the 2019–2020 season and the circulating influenza B and some subclades of A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses [14–16]. Available estimates suggest modest vaccine effectiveness (VE) (~39%) for prevention of ambulatory visits and hospitalizations in this season with circulation of 2 drifted viruses, but the VE for prevention of critical influenza illness has not been explored [16]. In an ICU network of 10 US hospitals, we evaluated the effectiveness of influenza vaccination for the prevention of severe influenza-associated illness among adults during the 2019–2020 influenza season.

METHODS

We conducted a prospective observational study using a test-negative design to estimate influenza VE for preventing severe influenza-associated illness, including hospitalization, ICU admission, acute organ failure, and death [17–21]. The study was conducted by the Influenza and Other Viruses in the Acutely Ill (IVY) Network, a multicenter network funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient or a legally authorized representative.

Study Population

We enrolled hospitalized adults with signs and symptoms of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) from 10 October 2019 to 28 February 2020 at 10 hospitals in 9 US states. Detailed eligibility criteria are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The enrollment strategy, which is detailed in Supplementary Table 2, prioritized enrollment of critically ill influenza cases and test-negative controls, while also enrolling representative samples of hospitalized, non–critically ill cases and controls.

Study Procedures

After enrollment, trained study personnel interviewed patients (or surrogate informants if the patient was unable to answer questions) to collect data, including self-report of influenza vaccination for the current (2019–2020) and prior (2018–2019) season. Study personnel collected a midturbinate nasal and oropharyngeal swab for viral testing. Study personnel also abstracted data from the medical record, including death, ICU admission, and development of acute organ failure, defined as receipt of invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, new renal replacement therapy, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Test-Positive Cases and Test-Negative Controls

The results of all clinically obtained influenza reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests completed between 72 hours before and 72 hours after hospital presentation were recorded. Additionally, all respiratory samples collected for the study were shipped to the study laboratory at Vanderbilt for RT-PCR influenza testing using CDC primers and protocols. Test results with a cycle threshold of 40 or less were considered positive for influenza and with a cycle threshold of 40 or greater were considered indeterminate. Influenza-positive specimens were further tested to determine A subtypes (H1N1pdm09 and H3N2) and B lineages (Victoria and Yamagata).

Study patients with SARI who tested positive for influenza by either a clinically obtained RT-PCR or central laboratory RT-PCR test were classified as cases. Patients with SARI who tested negative for influenza by all tests were classified as controls. Patients with indeterminate influenza status (cycle threshold ≥40) by RT-PCR were not included in VE analyses.

Genetic Characterization of Detected Influenza Viruses

Influenza-positive specimens with a cycle threshold value of less than 30 underwent further genetic characterization at CDC, including whole-genome sequencing [22]. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted to determine hemagglutinin (HA) genetic clades and subclades in sequenced influenza A viruses [12, 13, 23].

Influenza Vaccination Verification

Research personnel conducted a systematic search of electronic medical records and state vaccination registries, and contacted relevant pharmacies, clinics (eg, primary care providers), payors, and other venues for evidence of influenza vaccination. Research personnel called patients/surrogates to clarify discordant information between initial self/surrogate-report of vaccination and results of systematic searches. Patients with verified receipt of an influenza vaccine more than 13 days prior to illness onset for the current season were classified as vaccinated. Patients without verified receipt of vaccination or vaccination after illness onset for the current season were classified as unvaccinated. Patients who had verified vaccination 0–13 days prior to illness onset were excluded from the VE analyses.

Study Covariates

Covariates, identified a priori, included study site, age, sex, race/ethnicity, calendar time (categorized as tertiles generated based on site-specific influenza activity using disease-onset dates of influenza cases) [24], insurance status, enrollment location (ICU vs non-ICU), days from illness onset to specimen collection for influenza testing, chronic medical conditions (including cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases; kidney and gastrointestinal diseases; neurological, psychiatric, and gastrointestinal diseases; malignancies; and hematological, autoimmune, and other immunosuppressive conditions), and frailty (assessed using a questionnaire derived from Fried and colleagues [25]) [7, 26].

Statistical Analyses

We summarized patients’ characteristics by influenza infection status (influenza cases vs test-negative controls) and verified vaccination status (vaccinated vs unvaccinated). Influenza VE within the full study population (ie, for the prevention of influenza-associated SARI) was calculated as follows: (1 − adjusted odds ratio of cases compared with controls for being vaccinated) × 100%. The adjusted odds ratio was calculated using multivariable unconditional logistic regression that modeled the association between vaccination and influenza status, while adjusting for the study covariates listed above. Vaccine effectiveness was reported in percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Missing data for covariates (including 4 variables with up to 13 missing values, ~2% of total observations) were imputed using multiple imputation with chained equations and 20 imputed datasets were generated for multivariable regression analyses [27].

Several planned secondary analyses were conducted to estimate influenza VE in prespecified subgroups, including the following: (1) age groups (18–49, 50–64, and ≥65 years), (2) influenza-associated ICU admission, (3) influenza-associated acute organ failure, and (4) influenza-associated death. For these assessments, we added corresponding interaction terms with vaccination status to the main regression model, and VE estimates were derived from the multivariable regression coefficients. A post hoc subgroup assessment of VE by race/ethnicity was also conducted. Vaccine effectiveness was also estimated by influenza virus type (A and B) and the most common subtype/lineage by restricting influenza cases to those from the specific type/lineage [5]. Exploratory VE estimates by the most common vaccine types (quadrivalent and trivalent high-dose) were provided.

Because previous reports suggest that vaccination in previous years could influence VE for the current season, we also conducted separate estimates incorporating verified vaccination information for the previous season (2018–2019) [5, 28]. This and other sensitivity analyses are detailed in Supplementary Table 3.

Statistical significance for effectiveness estimates was defined as a 95% CI excluding the null value. For assessing differences in VE by subgroups, we considered P values less than .15 as statistically significant, which is sufficient for interpreting interaction between 2 dichotomous variables when effect size is expected to be moderate to high (eg, absolute difference in VE >25%) [29, 30]. Analyses were conducted in R version 4.0.3 (http://www.r-project.org) and Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study Patients

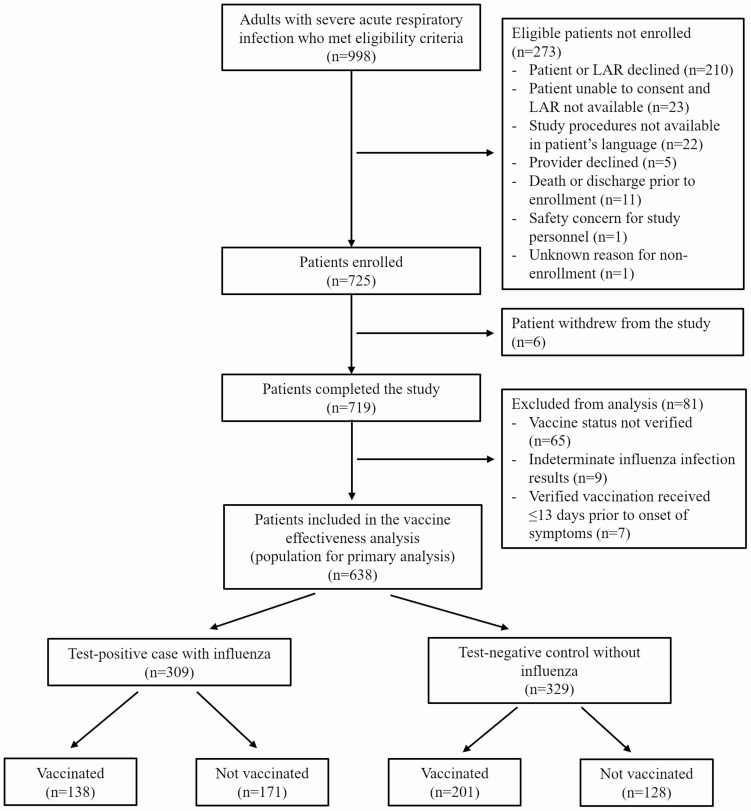

From 10 October 2019 through 28 February 2020, 998 eligible patients were approached for participation in the study; 725 of these patients consented for participation and 6 later withdrew from the study. Of the 719 enrolled patients who did not withdraw from the study, 81 were excluded from primary analysis due to indeterminate influenza infection status (n = 9), inability to verify vaccination status (n = 65), or verified vaccination within 13 days prior to symptom onset (n = 7) (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). Among 638 patients included in the primary analysis, the median (interquartile range) age was 57 years (44–68 years) and 336 (52.7%) were female. In this study sample enriched with ICU patients, 286 (44.8%) patients were treated in the ICU, 254 (39.8%) experienced acute organ failure, and 42 (6.6%) died during hospitalization.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient enrollment. Abbreviation: LAR, legally authorized representative.

Among the 638 patients included in the analyses, 309 (48.4%) were influenza cases, including 207 influenza A cases [166 A(H1N1)pdm09, 14 A(H3N2), 27 A without a subtype determined], 100 influenza B cases (77 B/Victoria, 3 B/Yamagata, 20 B without lineage determined), and 2 influenza cases with co-detections of A(H1N1)pdm09 and B/Victoria. A total of 339 (53.1%) patients were vaccinated for the current (2019–2020) season, including 138 (44.7%) of 309 influenza cases and 201 (61.1%) of 329 controls.

Compared with controls, influenza cases were younger, more likely to be Hispanic, and had fewer healthcare encounters during the prior year, lower frailty scores, and fewer comorbidities (Table 1). Compared with unvaccinated patients, patients who were vaccinated were older, more likely to be White non-Hispanic, more likely to have government insurance, and had more healthcare encounters during the prior year, higher frailty scores, and more comorbidities.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants by Case-Control and Vaccination Status

| Characteristic | Casesa (n = 309) | Controlsa (n = 329) | Vaccinatedb (n = 339) | Not Vaccinatedb (n = 299) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated for influenza,b n (%) | 138 (45) | 201 (61) | … | … |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 56 (41–65) | 59 (46–70) | 62 (52–72) | 51 (36–62) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||

| 18–49 years | 117 (38) | 95 (29) | 71 (21) | 141 (47) |

| 50–64 years | 109 (35) | 99 (30) | 113 (33) | 95 (32) |

| ≥65 years | 83 (27) | 135 (41) | 155 (46) | 63 (21) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 152 (49) | 150 (46) | 152 (45) | 150 (50) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Black non-Hispanic | 76 (25) | 84 (26) | 78 (23) | 82 (27) |

| White non-Hispanic | 170 (55) | 206 (63) | 222 (65) | 154 (52) |

| Hispanic | 46 (15) | 30 (9) | 33 (10) | 43 (14) |

| Other race, non-Hispanic | 17 (6) | 9 (3) | 6 (2) | 20 (7) |

| Site, n (%) | ||||

| Baystate Medical Center | 23 (7) | 22 (7) | 27 (8) | 18 (6) |

| Beth Israel Deaconess | 11 (4) | 9 (3) | 12 (4) | 8 (<1) |

| Hennepin County Medical Center | 21 (7) | 23 (7) | 23 (7) | 21 (7) |

| Intermountain Medical Center | 24 (8) | 16 (5) | 19 (6) | 21 (7) |

| Montefiore Medical Center | 36 (12) | 45 (14) | 35 (10) | 46 (15) |

| Ohio State Medical Center | 22 (7) | 20 (6) | 23 (7) | 19 (6) |

| Oregon Health and Sciences | 34 (11) | 35 (11) | 32 (9) | 37 (12) |

| University of Colorado | 29 (9) | 28 (9) | 27 (8) | 30 (10) |

| Vanderbilt University | 76 (25) | 101 (31) | 100 (29) | 77 (26) |

| Wake Forest | 33 (11) | 30 (9) | 41 (12) | 22 (7) |

| Insurance, n (%) | ||||

| Government | 185 (60) | 214 (65) | 230 (68) | 169 (57) |

| Private | 98 (32) | 102 (31) | 106 (31) | 94 (31) |

| None | 26 (8) | 13 (4) | 3 (<1) | 36 (12) |

| Healthcare visits in past year, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 43 (14) | 29 (9) | 17 (5) | 55 (19) |

| 1 | 20 (7) | 25 (8) | 22 (6) | 23 (8) |

| ≥2 | 237 (79) | 271 (83) | 294 (88) | 214 (73) |

| ED visits past year, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 106 (35) | 99 (30) | 95 (28) | 110 (38) |

| 1 | 58 (19) | 71 (22) | 72 (21) | 57 (20) |

| ≥2 | 136 (45) | 155 (48) | 168 (50) | 123 (42) |

| Hospital admissions in past year, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 141 (47) | 125 (38) | 122 (36) | 144 (49) |

| 1 | 57 (19) | 73 (22) | 73 (22) | 57 (20) |

| ≥2 | 103 (34) | 128 (39) | 140 (42) | 91 (31) |

| Frailty score,c median (IQR) | 1 (0–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 1 (0–3) |

| Time between symptom onset and first | ||||

| RT-PCR influenza test, median (IQR), days | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) |

| Smoking/vaping history, n (%) | 181 (59) | 192 (58) | 192 (57) | 181 (61) |

| Tertile of seasonal influenza Activityd | ||||

| 1 (Initial one-third of season) | 105 (34) | 88 (27) | 91 (27) | 102 (34) |

| 2 (Middle one-third of season) | 97 (31) | 87 (26) | 99 (29) | 85 (28) |

| 3 (Last one-third of season) | 107 (35) | 154 (47) | 149 (44) | 112 (37) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Cardiovascular/pulmonary | 218 (71) | 266 (81) | 289 (85) | 195 (65) |

| Endocrine/kidney | 130 (42) | 183 (56) | 207 (61) | 106 (35) |

| Immunosuppressive condition | 100 (32) | 163 (50) | 158 (47) | 105 (35) |

| Neurologic/psychiatric/gastrointestinal | 126 (41) | 136 (41) | 159 (47) | 103 (34) |

| Enrollment in ICU, n (%) | 129 (42) | 157 (48) | 150 (44) | 136 (45) |

| Influenza infection,a n (%) | 309 (100) | - | 171 (57) | 138 (41) |

| Influenza A,a n (%) | 207 (67) | 99 (30) | 108 (36) | |

| A(H1N1)pdm09 | 166 (54) | 83 (24) | 83 (28) | |

| H3N2 | 14 (5) | 4 (1) | 10 (3) | |

| Influenza B,a n (%) | 100 (32) | 38 (12) | 62 (21) | |

| Victoria | 77 (25) | 30 (9) | 47 (16) | |

| Yamagata | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

aParticipants who tested positive for influenza by RT-PCR were classified as cases, while those who tested negative were classified as controls. Counts may not add up to totals due to incomplete typing or subtyping.

bParticipants who had verified receipt of an influenza vaccine for the 2019–2020 season at least 13 days before illness onset were classified as vaccinated, while those who did not have verified receipt of an influenza vaccine for the 2019–2020 season were classified as unvaccinated. Patients with vaccine receipt 0–13 days prior to illness onset were excluded from the analysis.

cThe frailty score ranged from 0 (not frail) to 5 (very frail) according to the classification described by Fried and colleagues [25].

dTertile of seasonal influenza activity divided the 2019–2020 influenza season into the initial one-third of the season, middle one-third of the season, and last one-third of the season for each site based on local influenza activity [4].

Genetic Characterization of Influenza Viruses

Among 309 influenza cases, 120 had viruses characterized by whole-genome sequencing, including 70 A(H1N1)pdm09, 4 A(H3N2), 43 B/Victoria, and 3 B/Yamagata. All sequenced A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses belonged to the hemagglutinin 6B.1A group. Eighteen A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses belonged to subclade 5A viruses with additional amino acid changes in K130N, N156K, L161I, V250A, and E506D (5A + 156K viruses); 43 belonged to subclade 5A viruses with additional amino acid substitutions D187A and Q189E in the HA protein (5A + 187A, 189E viruses); and 9 belonged to other subclades. All sequenced A(H3N2) viruses belonged to the 3C.2a1b group. Of the 43 B/Victoria viruses sequenced, 42 viruses belonged to clade V1A.3 and 1 belonged to clade V1A.1. All sequenced B/Yamagata viruses belonged to clade Y3 [14, 15, 31]. Recent assessments have shown that A(H1N1)pdm09 5A + 156K viruses were poorly matched by the 2019–2020 influenza vaccine formulation. Moreover, the V1A.3 B/Victoria viruses showed limited similarity with the vaccine formulation components [1, 12, 13].

Vaccine Effectiveness

In the primary multivariable analytical model, VE for the prevention of influenza-associated SARI was 32% (2% to 53%). Vaccine effectiveness was higher among adults aged 18–49 years old (62%; 95% CI: 27% to 81%) than those aged 50–64 years old (20%; 95% CI: −48% to 57%) and those aged 65 years or older (−3%; 95% CI: −97% to 46%) (P value for interaction = .0789) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Vaccine Effectiveness for the Prevention of Influenza-Associated Severe Outcomes, Including Severe Acute Respiratory Infection, Intensive Care Unit Admission, Organ Failure, and Death

| Influenza Cases, n [n Vaccinated (% Vaccinated)] | Noninfluenza Controls, n [n Vaccinated (% Vaccinated)] | Unadjusted OR for Vaccination (95% CI)a | Adjusted OR for Vaccination (95% CI)b | Vaccine Effectiveness,c % (95% CI) | P Value for Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe acute respiratory infection (full population) | 309 [138 (44.7%)] | 329 [201 (61.1%)] | .51 (.37–.7) | .68 (.47–.98) | 32 (2–53) | |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||

| 18–49 | 117 [26 (22.2%)] | 95 [45 (47.4%)] | .32 (.18–.57) | .38 (.20–.73) | 62 (27–81) | .0789 |

| 50–64 | 109 [53 (48.6%)] | 99 [60 (60.6%)] | .62 (.35–1.07) | .8 (.43–1.48) | 20 (−48 to 57) | |

| ≥65 | 83 [59 (71.1%)] | 135 [96 (71.1%)] | 1 (.55–1.83) | 1.03 (.54–1.97) | −3 (−97 to 46) | |

| Race/ethnicityd | ||||||

| Black non-Hispanic | 76 [32 (42.1%)] | 84 [46 (54.8%)] | .6 (.32–1.12) | .67 (.34–1.33) | 33 (−33 to 66) | .9083 |

| White non-Hispanic | 170 [86 (50.6%)] | 206 [136 (66%)] | .53 (.35–.8) | .7 (.44–1.12) | 30 (−12 to 56) | |

| Other race/Hispanic | 63 [20 (31.7%)] | 39 [19 (48.7%)] | .49 (.22–1.11) | .56 (.23–1.38) | 44 (− 38 to 77) | |

| ICU admission | ||||||

| Non-ICU admission | 180 [79 (43.9%)] | 172 [110 (64%)] | .44 (.29–.68) | .54 (.33–.87) | 46 (13–67) | .1612 |

| ICU admission | 129 [59 (45.7%)] | 157 [91 (58%)] | .61 (.38–.98) | .88 (.51–1.51) | 12 (−51 to 49) | |

| Acute organ failuree | ||||||

| No acute organ failure | 199 [87 (43.7%)] | 185 [118 (63.8%)] | .44 (.29–.66) | .59 (.37–.94) | 41 (6–63) | .3582 |

| Acute organ failure | 110 [51 (46.4%)] | 144 [83 (57.6%)] | .64 (.39–1.05) | .82 (.47–1.43) | 18 (−43 to 53) | |

| In-hospital death | ||||||

| No death | 288 [135 (46.9%)] | 308 [188 (61.0%)] | .56 (.41–.78) | .73 (.5–1.07) | 27 (−7 to 50) | .1136 |

| Death | 21 [3 (14.3%)] | 21 [13 (61.9%)] | .10 (.02–.46) | .20 (.04–.97) | 80 (4–96) | |

| Virus type and main subtype/lineage | ||||||

| Influenza A | 207 [99 (47.8%)] | 329 [201 (61.1%)] | .58 (.41–.83) | .72 (.48–1.09) | 28 (−9 to 52) | … |

| A(H1N1)pdm09 | 166 [83 (50%)] | 329 [201 (61.1%)] | .64 (.44–0.93) | .83 (.53–1.31) | 17 (−31 to 47) | … |

| Influenza B | 100 [38 (38%)] | 329 [201 (61.1%)] | .39 (.25–0.62) | .48 (.27–.87) | 52 (13–74) | … |

| Victoria | 77 [30 (39%)] | 329 [201 (61.1%)] | .41 (.24–.68) | .55 (.28–1.09) | 45 (−9 to 72) | … |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio.

aThe unadjusted OR was calculated with a logistic regression model with influenza case vs noninfluenza control status as the dependent variable and vaccination status (vaccinated vs unvaccinated) as the independent variable.

bThe adjusted OR was calculated with a multivariable logistic regression model with influenza case vs noninfluenza control status as the dependent variable, vaccination status (vaccinated vs unvaccinated) as the primary independent variable, and the following covariates: study site, age in years, sex, race/ethnicity, calendar time (categorized as tertiles generated based on site-specific influenza activity using disease-onset dates of influenza cases), insurance status, enrollment location (ICU vs outside the ICU), days from illness onset to specimen collection for influenza testing, chronic medical conditions (including [a] cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, [b] kidney and gastrointestinal diseases, [c] neurological, psychiatric and gastrointestinal diseases, and [d] hematological, malignancies, autoimmune, and other immunosuppressive conditions), and frailty score (which ranged from 0 [not frail] to 5 [very frail]).

cVaccine effectiveness, reported as a percentage, was calculated as follows: (1 − adjusted OR for vaccination) × 100.

dThe “Other race” group was combined with the Hispanic group because of low counts in these groups.

eAcute organ failure was defined as receipt of any of the following during the hospitalization in which the patient was enrolled: noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, acute renal replacement therapy, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

In subgroup analysis, VE was higher for the prevention of influenza-associated death than for prevention of nonfatal influenza (P = .1136). The estimated VE for the prevention of influenza-associated death was 80% (4% to 96%). Most of the 21 patients with influenza who died were young or middle-aged adults (median age: 53 years) as compared with the 21 test-negative control patients who died (median age: 68 years) (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). No significant differences in VE were observed among subgroups defined by race/ethnicity, ICU admission, or acute organ failure (Table 2).

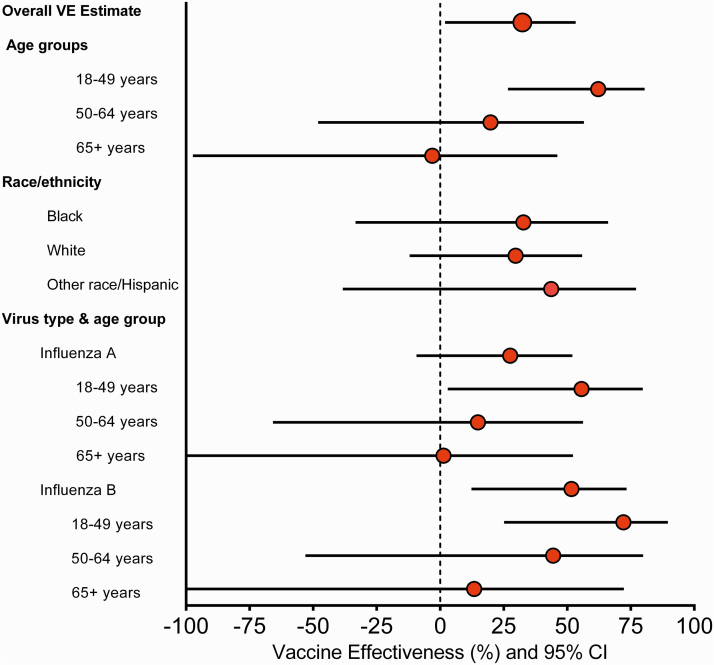

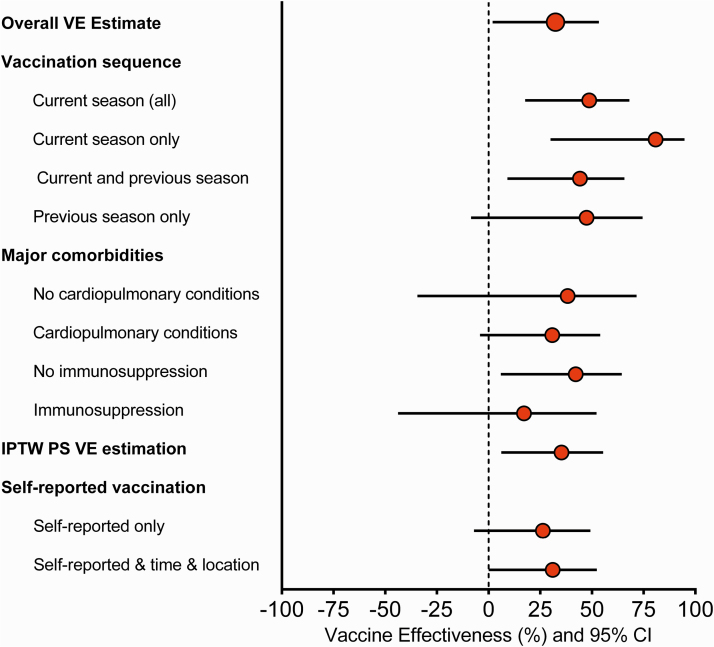

Vaccine effectiveness for preventing SARI caused by influenza A was 28% (−9% to 52%) and by influenza B was 52% (13% to 74%), with similar estimates for the most frequently detected subtype/lineage. Similar to the pattern observed in the main analysis, VE against influenza A and B estimates tended to be higher, but not significantly different, among younger compared with older adults (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 6); VE estimates by vaccine types were consistent with the main findings (Supplementary Table 6). Compared with patients who were not vaccinated in either the current or previous influenza season, patients vaccinated only during the current season or during both current and previous season had similar VE estimates—49% (19% to 67%) and 44% (9% to 66%), respectively (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 2.

Secondary analyses of influenza VE for the prevention of influenza-associated severe acute respiratory infection. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; VE, vaccine effectiveness.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analyses for the assessment of influenza vaccine effectiveness for the prevention of influenza-associated severe acute respiratory infection. These secondary estimates evaluating vaccine sequence were restricted to the subset of patients with verified vaccination for the current and previous season. Note all comparisons used those patients who were not vaccinated in either season as reference. Current season estimates included all participants vaccinated during the current season. Current season only estimates include participants vaccinated during the current season who were not vaccinated during the previous season. Current and previous season estimates include participants who were vaccinated during both seasons. Previous season only estimates include participants who were vaccinated during the previous season; patients vaccinated in the current season were not included in this estimation. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting; PS, propensity scores; VE, vaccine effectiveness.

Sensitivity Analyses

When age was modeled with a flexible spline function, VE for the prevention of SARI varied significantly with age (P = .0242), with higher VE again observed among younger adults (Supplementary Figure 2A). Higher VE among younger adults was also observed for the prevention of ICU admission and acute organ failure (Supplementary Figure 2B, 2C). There were no significant differences in estimates based on presence of cardiopulmonary or immunosuppressive conditions, although the VE estimates for patients with immunosuppressive conditions was only 17% (−44% to 52%) (Supplementary Table 7).

The alternate analysis that summarized relevant covariates through calculation of vaccination propensity scores and stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting yielded VE results for the prevention of SARI (35%; 6% to 55%) that were nearly identical to those from the primary analysis (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 7). Supplementary Figure 3 displays the standardized mean differences between cases and controls before and after weighting, indicating that the distribution of covariates was well balanced after weighting. Last, influenza vaccination was not significantly associated with lower odds of death among influenza-negative controls, but it was associated with lower odds of death among influenza-positive cases (P-interaction = .035) (Supplementary Table 7).

DISCUSSION

During the 2019–2020 influenza season in the United States, characterized by unusually early and intense influenza B activity as well as circulation of drifted A(H1N1)pdm and B/Victoria viruses [12, 13], influenza vaccination was associated with a 32% reduction in the odds of severe, hospitalized, laboratory-confirmed influenza disease. Vaccine effectiveness against influenza A was 28% (−9% to 52%) and against influenza B was 52% (13% to 74%). In a season with a relatively poor match between vaccine strains and circulating viruses [12, 13], influenza vaccination was modestly protective against the most severe manifestations of influenza infection.

Influenza VE varied with age, with high effectiveness against severe outcomes among young adults. Although this study was designed to enroll patients with SARI, and included a large subset of patients who were treated in an ICU, the median age of influenza-positive cases was only 56 years. Furthermore, among patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza infection who died, the median age was only 53 years. The vast majority of those fatal cases had no major underlying comorbidities, suggesting that their outcome could have been prevented if they did not develop influenza disease. Compared with previous VE studies [6, 7, 9], this study included younger patients with a higher mortality rate, suggesting that the effort to target enrollment of severely ill patients with critical illness caused by influenza was successful.

Although VE for the prevention of influenza-associated death was based on only 42 deaths, it is noteworthy that the estimated VE point estimate was higher (~80%) than the effectiveness estimates against other study outcomes. The higher level of protection against deaths when adjusted for age and other potential confounders reflected the markedly lower vaccination rates (14%) among patients with influenza-associated death than test-negative controls overall (61%) and test-negative controls who died (62%). Thus, we suspect that the observed influenza-associated deaths were potentially preventable with vaccination. Additional studies of severe influenza illness, possibly combining data across multiple seasons to increase sample size, will be important to conclusively estimate VE against death. These observations contribute to the accumulating body of evidence supporting the effectiveness of influenza vaccines for the prevention of influenza-associated death [32, 33].

Results of this study build upon the findings of previous, smaller studies that have also demonstrated influenza VE for preventing severe influenza illness. Among 101 adults hospitalized in the ICU at 2 New Zealand hospitals during 3 consecutive influenza seasons, influenza vaccines were 82% effective in preventing ICU admissions [9]. Similarly, a study conducted among children admitted to the pediatric ICU during 2 consecutive influenza seasons in the United States reported an influenza VE of 74% for the prevention of ICU admission when cases were compared with ICU controls and 82% when compared with community controls [34]. Furthermore, VE for the prevention of influenza-associated ICU admission was 81% among 227 US adult patients during the 2015–2016 season [7]. A recent study from Australia using hospital surveillance data for children and adults from 2010 through 2017 and a test-negative design reported 31% effectiveness in preventing influenza-associated mortality [32].

Acknowledging the widespread use of reliable molecular diagnostics for accurate clinical identification of influenza infections, the current study applied a test-negative design that takes advantage of the rapid availability of clinical test results. This approach, referred to as the “real-time test negative design,” can be useful to optimize the case-to-test-negative control ratio and increase study efficiency by supervising the number of enrolled controls [21]. Importantly, all study patients needed to satisfy a clear operational definition of compatible disease (ie, SARI) and have an influenza test performed before they could be enrolled [19, 20, 35]. Although the test-negative design is considered the referent approach for determinations of influenza VE, some elements require careful consideration to ensure the validity of the estimates. As factors that may lead to differential healthcare utilization and influenza testing, we specifically accounted for cardiopulmonary and immunosuppressive conditions in our main analysis and prespecified sensitivity analyses [18, 35].

This study had limitations. First, despite this being the largest US study to date evaluating influenza VE in critically ill ICU patients, the modest sample size resulted in limited precision of some results. Second, although the analysis accounted for several confounding factors identified a priori, and our findings were robust in several prespecified secondary and sensitivity analyses, residual confounding is possible. Other factors, such as the prevaccination immunological status of participants, were not directly measured and accounted for. To examine potential residual confounding in the death analysis, we examined the association between vaccination and death among influenza-negative controls. There was no association between vaccination and death among controls, increasing confidence that the observed association between vaccination and lower odds of influenza-associated death was due to vaccine effects and not residual confounding. Third, viral detections were identified from both clinical and research testing and viral loads were not evaluated. Fourth, while viral sequencing revealed the circulation of drifted strains, only a fraction of influenza detections were successfully sequenced. Last, although patients were enrolled from 10 locations dispersed across the United States, enrollment occurred at academic medical centers and findings may not be directly applicable to other settings.

In summary, this large, prospective multicenter study demonstrated that during the 2019–2020 influenza season, influenza vaccination was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of hospitalization with severe influenza disease, especially among younger adults. These findings suggest that vaccination decreases the risk of the most severe manifestations of influenza infection.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. C. G. G., L. R. F., H. K. T., M. P., and W. H. S. conceptualized the study. W. H. S. acquired funding for the study. All authors contributed to the development of data collection forms. M. A., A. H. B., S. M. B., J. D. C., H. L. E., M. C. E., D. C. F., K. W. G., A. A. G., M. N. G., A. K., I. D. P., M. E. P., T. W. R., N. I. S., J. S., W. B. S., and W. H. S. led patient enrollment and data and sample collection. A. H. B., C. J. L., and W. H. S. supervised data and biological sample collection. C. G. G., L. R. F., and S. K. N. conducted data analyses. C. G. G., L. R. F., M. P., and W. H. S. prepared the manuscript draft. All authors critically revised, edited and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval. The conduct of this study was approved by the institutional review board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, which served as the single institutional review board for the multicenter network.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support. This work was supported by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through contract 75D30119C05670 to W. H. S. Investigators from the CDC participated in the study design, analysis, and interpretation.

Potential conflicts of interest. C. G. G. reports consultation fees from Pfizer, Merck, and Sanofi-Pasteur and grants from Sanofi, Campbell Alliance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Food and Drug Administration, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, outside the submitted work. S. M. B. reports grants from CDC for the submitted work; grants from the NIH, Department of Defense, Janssen, Faron, and Sedana; personal fees to chair a Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) for Hamilton; and book royalties from Oxford University and Brigham Young University, outside the submitted work. J. D. C. reports grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), outside the submitted work. M. C. E. reports grants from NIH, outside submitted work. D. C. F. reports grants from CDC during the conduct of this study and personal fees from Cytovale and Medpace, outside this work. A. A. G. reports grants from CDC during the conduct of the study, and grants from NHLBI, NCATS, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), Department of Defense (DoD), CDC, and AbbVie Inc, outside the submitted work. M. N. G. reports receiving research funding from NHLBI, AHRQ, and Regeneron to conduct research; funding from CDC for this work; fees for serving on DSMBs for trials sponsored by Regeneron. N. H. reports grant support from Sanofi, Quidel, CDC, the NIH, and an educational grant supported by Genetech for speaker fees, and hemagglutination inhibition/microneutralization (HAI/MN) testing and vaccine donation by Sanofi. A. K. reports grants from United Therapeutics, Reata Pharmaceuticals, and Jansen Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. C. J. L. reports support from CDC for the submitted work; grants from the NIH, CDC, and the DoD; and other support from Marcus Foundation, Endpoint Health, Entegrion, bioMerieux, and Bioscape Digital, outside the submitted work. S. K. N. reports support from CDC for the submitted work, and grants from the NIH and the Marcus Foundation, outside the submitted work. I. D. P. reports grants from National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), CDC, NHLBI, and Immuneexpress Inc, outside this work, and support to his institution from Regeneron and Janssen Pharmaceutical, outside this work. T. W. R. reports grants from NHLBI, NCATS, and AbbVie Inc, outside the submitted work, and consulting for Cytovale Inc and Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Inc, outside the submitted work. W. H. S. reports receiving research funding from the CDC for the submitted work; consulting fees from Merck & Co Inc, Pfizer, Aerpio Pharmaceuticals, and Baxter, outside the submitted work; and research funding from Merck & Co Inc, Pfizer, and Gilead Sciences, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, Walter EB, Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices—United States, 2019–20 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2019; 68:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chung JR, Rolfes MA, Flannery B, et al. ; US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network; Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network; Assessment Branch, Immunization Services Division, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Effects of influenza vaccination in the United States during the 2018–2019 influenza season. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:e368–76.31905401 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rolfes MA, Flannery B, Chung JR, et al. ; US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness (Flu VE) Network; Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network; Assessment Branch, Immunization Services Division, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Effects of influenza vaccination in the United States during the 2017–2018 influenza season. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:1845–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biggerstaff M, Kniss K, Jernigan DB, et al. Systematic assessment of multiple routine and near real-time indicators to classify the severity of influenza seasons and pandemics in the United States, 2003–2004 through 2015–2016. Am J Epidemiol 2018; 187:1040–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jackson ML, Chung JR, Jackson LA, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during the 2015–2016 season. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:534–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tenforde MW, Chung J, Smith ER, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in inpatient and outpatient settings in the United States, 2015–2018. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:386–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferdinands JM, Gaglani M, Martin ET, et al. ; HAIVEN Study Investigators . Prevention of influenza hospitalization among adults in the United States, 2015-2016: results from the US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (HAIVEN). J Infect Dis 2019; 220:1265–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, Williams DJ, et al. Association between hospitalization with community-acquired laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia and prior receipt of influenza vaccination. JAMA 2015; 314:1488–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thompson MG, Pierse N, Sue Huang Q, et al. ; SHIVERS Investigation Team . Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza-associated intensive care admissions and attenuating severe disease among adults in New Zealand 2012–2015. Vaccine 2018; 36:5916–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arriola C, Garg S, Anderson EJ, et al. Influenza vaccination modifies disease severity among community-dwelling adults hospitalized with influenza. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:1289–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Castilla J, Godoy P, Domínguez A, et al. ; CIBERESP Cases and Controls in Influenza Working Group Spain . Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing outpatient, inpatient, and severe cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tenforde MW, Kondor RJG, Chung JR, et al. Effect of antigenic drift on influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States—2019–2020. Clin Infect Dis 2020:ciaa1884; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tenforde MW, Talbot HK, Trabue CH, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization in the United States, 2019–2020. J Infect Dis 2020:jiaa800; doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization. Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2020–2021 Northern Hemisphere influenza season. Available at: https://www.who.int/influenza/vaccines/virus/recommendations/202002_recommendation.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 20 October 2020.

- 15. Skowronski DM, Zou M, Sabaiduc S, et al. Interim estimates of 2019/20 vaccine effectiveness during early-season co-circulation of influenza A and B viruses, Canada, February 2020. Euro Surveill 2020; 25:2000103. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dawood FS, Chung JR, Kim SS, et al. Interim estimates of 2019-20 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:177–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Foppa IM, Haber M, Ferdinands JM, Shay DK. The case test-negative design for studies of the effectiveness of influenza vaccine. Vaccine 2013; 31:3104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vandenbroucke JP, Pearce N. Test-negative designs: differences and commonalities with other case-control studies with “other patient” controls. Epidemiology 2019; 30:838–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sullivan SG, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Cowling BJ. Theoretical basis of the test-negative study design for assessment of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Am J Epidemiol 2016; 184:345–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lewnard JA, Tedijanto C, Cowling BJ, Lipsitch M. Measurement of vaccine direct effects under the test-negative design. Am J Epidemiol 2018; 187:2686–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Feldstein LR, Self WH, Ferdinands JM, et al. ; Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in the Critically Ill (IVY) Investigators and the Pediatric Intensive Care Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness (PICFLU-VE) Investigators . Incorporating real-time influenza detection into the test-negative design for estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness: the Real-time Test-negative Design (rtTND). Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72:1669–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Flannery B, Kondor RJG, Chung JR, et al. Spread of antigenically drifted influenza A(H3N2) viruses and vaccine effectiveness in the United States during the 2018–2019 season. J Infect Dis 2020; 221:8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Types of influenza viruses. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/types.htm. Accessed 21 July 2020.

- 24. McLean HQ, Thompson MG, Sundaram ME, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during 2012-2013: variable protection by age and virus type. J Infect Dis 2015; 211:1529–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group . Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56:M146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sullivan SG, Cowling BJ, Greenland S. Frailty and influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine 2016; 34:4645–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med 2011; 30:377–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Foppa IM, Ferdinands JM, Chung J, Flannery B, Fry AM. Vaccination history as a confounder of studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine X 2019; 1:100008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Durand CP. Does raising type 1 error rate improve power to detect interactions in linear regression models? A simulation study. PLoS One 2013; 8:e71079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marshall SW. Power for tests of interaction: effect of raising the type I error rate. Epidemiol Perspect Innov 2007; 4:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Owusu D, Hand J, Tenforde MW, et al. Early season pediatric influenza B/Victoria virus infections associated with a recently emerged virus subclade–Louisiana, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:40–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nation ML, Moss R, Spittal MJ, Kotsimbos T, Kelly PM, Cheng AC. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza-related mortality in Australian hospitalized patients: a propensity score analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Flannery B, Reynolds SB, Blanton L, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against pediatric deaths: 2010–2014. Pediatrics 2017; 139:e20164244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ferdinands JM, Olsho LE, Agan AA, et al. ; Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network . Effectiveness of influenza vaccine against life-threatening RT-PCR-confirmed influenza illness in US children, 2010–2012. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:674–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Foppa IM, Ferdinands JM, Chaves SS, et al. The case test-negative design for studies of the effectiveness of influenza vaccine in inpatient settings. Int J Epidemiol 2016; 45:2052–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.