Abstract

Patients with autosomal dominant SPECC1L variants show syndromic malformations, including hypertelorism, cleft palate and omphalocele. These SPECC1L variants largely cluster in the second coiled-coil domain (CCD2), which facilitates association with microtubules. To study SPECC1L function in mice, we first generated a null allele (Specc1lΔEx4) lacking the entire SPECC1L protein. Homozygous mutants for these truncations died perinatally without cleft palate or omphalocele. Given the clustering of human variants in CCD2, we hypothesized that targeted perturbation of CCD2 may be required. Indeed, homozygotes for in-frame deletions involving CCD2 (Specc1lΔCCD2) resulted in exencephaly, cleft palate and ventral body wall closure defects (omphalocele). Interestingly, exencephaly and cleft palate were never observed in the same embryo. Further examination revealed a narrower oral cavity in exencephalic embryos, which allowed palatal shelves to elevate and fuse despite their defect. In the cell, wild-type SPECC1L was evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm and colocalized with both microtubules and filamentous actin. In contrast, mutant SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein showed abnormal perinuclear accumulation with diminished overlap with microtubules, indicating that SPECC1L used microtubule association for trafficking in the cell. The perinuclear accumulation in the mutant also resulted in abnormally increased actin and non-muscle myosin II bundles dislocated to the cell periphery. Disrupted actomyosin cytoskeletal organization in SPECC1L CCD2 mutants would affect cell alignment and coordinated movement during neural tube, palate and ventral body wall closure. Thus, we show that perturbation of CCD2 in the context of full SPECC1L protein affects tissue fusion dynamics, indicating that human SPECC1L CCD2 variants are gain-of-function.

Introduction

Many embryonic tissue morphogenetic events require movement and fusion events. Examples include neural tube, palate, ventral body wall and optic fissure closure (1,2). These processes require a precise sequence of remodeling events in a narrow and time-sensitive window of embryogenesis. Incorrect movement or incomplete fusion in the three examples described above leads to structural birth defects of anencephaly/exencephaly (1/4000 live births), cleft palate (1/1700), omphalocele (1/4000) and coloboma (1/2000), respectively (3).

We are studying the cytoskeletal protein sperm antigen with calponin homology and coiled-coil domains 1-like (SPECC1L) that is proposed to associate with both actin filaments and microtubules via its calponin homology domain (CHD) and coiled coil domain 2 (CCD2), respectively (4–6). We and others have shown that patients with autosomal dominant SPECC1L variants manifest a range of structural birth defects, including hypertelorism (97%), omphalocele (45%) and cleft palate (24%) (4,7–9). Interestingly, all SPECC1L variants in these patients with syndromic manifestation cluster largely in CCD2 and to a lesser extent in CHD, indicating a critical role for these domains.

To understand the function of SPECC1L in the etiology of these structural defects, we generated and evaluated several different mouse alleles, including a C-terminal truncation that also removed the CHD (Specc1lΔC510) (6) and null allele lacking any protein (Specc1lΔEx4, Fig. 1). Homozygous mutants for these alleles exhibited perinatal lethality but did not show cleft palate or omphalocele (6). We did observe a delay in palatal shelf elevation in Specc1lΔC510 compound heterozygotes with Specc1l genetrap alleles (Specc1lgt/ΔC510). These compound heterozygous mutants were also perinatal lethal and showed both palatal shelf epithelial (6) and mesenchymal defects (10). Thus, due to the lack of cleft palate or omphalocele occurrence in null mutants, we hypothesized that patient phenotypes of cleft palate and omphalocele were due to gain-of-function CCD2 variants.

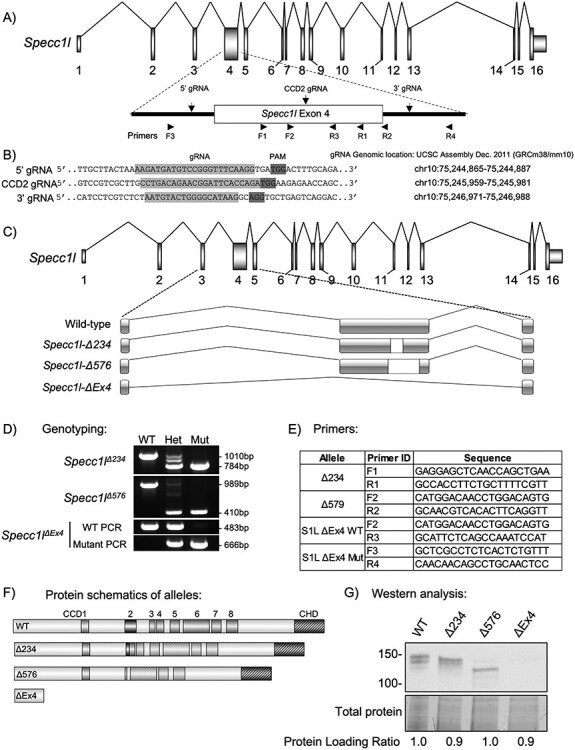

Figure 1 .

Generation of Specc1l null and CCD2 deletion alleles. (A) Schematic of Specc1l locus. The largest exon 4, which also encodes the coiled-coil domain 2 (CCD2), is highlighted. The locations of the two guide RNAs (5′ and 3′ gRNAs) used to delete exon 4 as well as the gRNA used to introduce deletions in CCD2 (CCD2 gRNA) are indicated. Also shown are the approximate locations of the sequencing primers used for genotyping in D and E. (B) Sequences and genomic locations of the gRNAs used in A. PAM, protospacer adjacent motif. (C) Schematic representation of the genomic deletions created by the two CCD2 in-frame (Δ234, Δ576 base pairs) and the null exon 4 deletion (ΔEx4). (D) Genotyping analysis of the three alleles, showing heterozygous and homozygous occurrence of the slower migrating band corresponding to deletion. Please note that the third hybrid band visible in heterozygous samples with small deletions are heteroduplexes—an expected PCR artifact. Due to the large deletion in ΔEx4, wild-type and mutant alleles are genotyped separately. (E) Sequence for primer pairs used for genotyping shown in D. Primer locations are also shown in the schematic of exon 4 in A. (F) SPECC1L protein schematics resulting from the CCD2 deletions and the null allele. CCD, coiled-coil domain; CHD, calponin homology domain. (G) Western blot analysis of tissue from wild-type (WT) and homozygous mutants for the four alleles. WT SPECC1L band migrates at ~150 KDa. For the two in-frame CCD2 deletion alleles (Δ234, Δ576), corresponding faster migrating bands are visible. There are no bands visible for the ΔEx4 null allele. Total protein and comparative ratio are shown as loading control.

To test this hypothesis, we targeted CCD2 with clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based genome editing. Here, we report two alleles with in-frame genomic deletions removing portions of CCD2 (collectively termed Specc1lΔCCD2). Homozygous mutants for both alleles showed either cleft palate or exencephaly and omphalocele at high penetrance. In contrast, homozygous mutants for Specc1lΔEx4 null allele showed none at birth. In addition, we observed significantly higher penetrance of cleft palate in female Specc1lΔCCD2/+ heterozygotes than male counterparts. We also provide cellular and molecular evidence for a role of SPECC1L in regulating actomyosin organization during tissue morphogenesis.

Results

Specc1l null mutants show perinatal lethality with no defects of fusion events

We previously generated three different mouse alleles for Specc1l deficiency using a genetrap-based knockdown strategy (5,6). Homozygous mutants for all three genetrap alleles showed early embryonic lethality with a neural tube closure defect (5,6). We also generated an allele (Specc1lΔC510) with a C-terminal truncation that deleted 510 amino acids including the CHD (6). Homozygous mutants for this allele were perinatal lethal but did not show exencephaly or cleft palate; however, the truncated protein was still expressed (6). To determine the true Specc1l null phenotype, we have now used CRISPR guide RNAs (gRNAs) flanking exon 4 (Fig. 1A and B) to generate a knockout allele lacking exon 4 (Specc1lΔEx4, Fig. 1C) that does not show any SPECC1L protein product (Fig. 1F and G). Homozygous mutants for Specc1lΔEx4 are also perinatal lethal and do not show exencephaly or cleft palate (Fig. 2). Thus, we hypothesized that the human CCD2 variants resulting in cleft palate and omphalocele were gain-of-function.

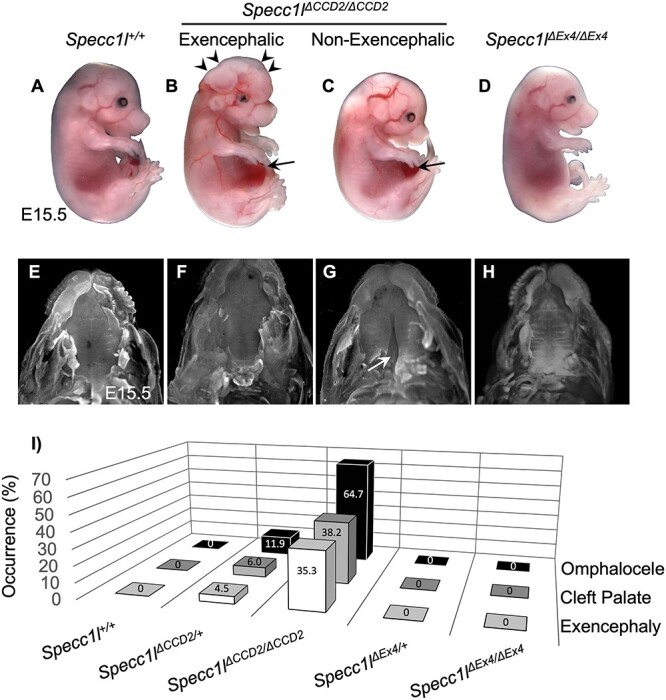

Figure 2 .

Homozygous mutants with in-frame CCD2 deletions show omphalocele, cleft palate and exencephaly. (A–D) Gross images of wild-type (A, Specc1l+/+), Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2, with (B) or without (C) exencephaly, and Specc1lΔEx4/ΔEx4 null embryos at embryonic day (E) 15.5. Exencephaly is indicated in B with arrowheads. Omphalocele is indicated in B and C with arrows. (E–H) The palates are shown for E15.5 embryos with the jaws removed for the genotypes in A–D. The Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant with exencephaly (F) and the Specc1lΔEx4/ΔEx4 null (H) embryos do not show cleft palate, whereas the Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant without exencephaly does (G, white arrow). (I) The prevalence (%) of omphalocele, cleft palate and exencephaly is shown in Specc1lΔCCD2 and Specc1lΔEx4 heterozygous and homozygous mutants. For this analysis, data from the two in-frame CCD2 deletion alleles (Δ234, Δ576) were combined as ΔCCD2. The Specc1l+/+, Specc1lΔEx4/+ and Specc1lΔEx4/ΔEx4 embryos did not show any occurrence of omphalocele, cleft palate or exencephaly.

Specc1l mutants with in-frame deletion of CCD2 result in exencephaly, cleft palate and ventral body wall closure defects

To test this hypothesis, we targeted CCD2 with a CRISPR guide RNA (CCD2 gRNA; Fig. 1A and B) and identified alleles with both out-of-frame and in-frame deletions. Two alleles with in-frame deletions (Specc1lΔ234, Specc1lΔ576) were further characterized. Genomic changes were confirmed (Fig. 1C), and genotyping protocols were created (Fig. 1D and E). Predicted protein level changes in ΔCCD2 proteins (Fig. 1F) were validated for expression with western blot analysis using an N-terminal α-SPECC1L antibody (Fig. 1G). Homozygous mutants for all alleles with out-of-frame deletions were perinatal lethal and showed no exencephaly, cleft palate or omphalocele at birth (data not shown), similarly to homozygous mutants for Specc1lΔC510 (6) and Specc1lΔEx4 (Fig. 2). However, homozygous mutants for all alleles with an in-frame deletion in CCD2—Specc1lΔ234 and Specc1lΔ576 are collectively referred to as Specc1lΔCCD2—showed ~ 43% anterior neural tube closure defect (exencephaly, Fig. 2B, arrowheads; Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A–H), ~ 43% cleft palate (Fig. 2G) and ~60% ventral body wall closure defect (omphalocele, Fig. 2B and C, arrows; Supplementary Material, Fig. S2A–F). Embryonic penetrance values for all Specc1lΔCCD2 alleles are graphed collectively in Fig. 2I, and the values for individual alleles and phenotypic combinations are provided in Supplementary Material, Table S1. Closer inspection of the embryos at E15.5 also showed coloboma or incomplete fusion of the optic fissure in Specc1lΔCCD2 mutants (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3B and C versus Supplementary Material, Fig. S3A and D; arrows). Thus, in-frame perturbation of CCD2 in the context of full-length SPECC1L was more detrimental to embryonic tissue movement and fusion events than complete loss of SPECC1L protein, indicating a gain-of-function mechanism.

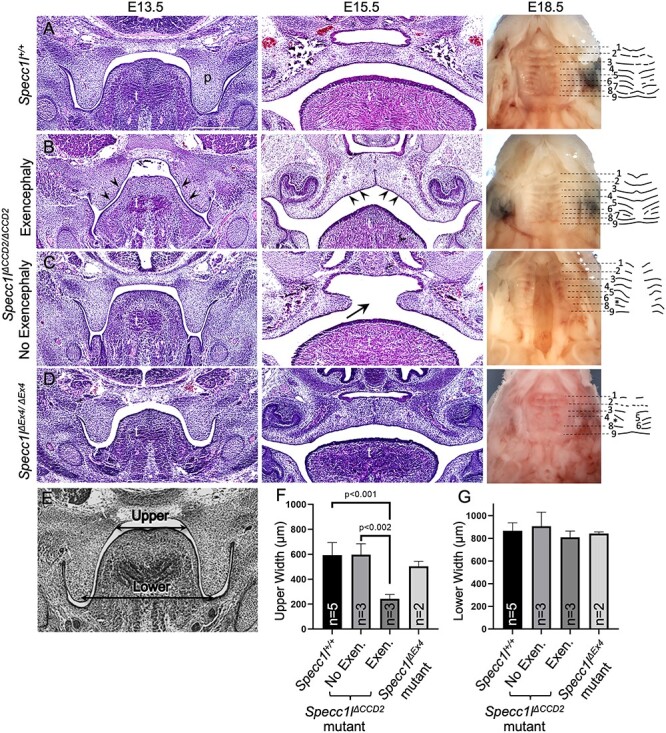

Homozygous Specc1lΔCCD2 mutant embryos did not simultaneously show exencephaly and cleft palate

In our phenotypic analysis, we noted that exencephaly (n = 12) and cleft palate (n = 12) never simultaneously occurred in the same Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 embryo (Supplementary Material, Table S1). In contrast, ventral body wall closure defect accompanied both exencephaly (n = 9/12, 75%) and cleft palate (n = 5/12, 42%). Histologic analysis of embryos showed that at E13.5, Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutants with exencephaly had a narrower oral cavity (Fig. 3B) than either wild-type control (Fig. 3A), homozygous Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutants without exencephaly (Fig. 3C) or homozygous null Specc1lΔEx4/ΔEx4 mutants (Fig. 3D). In addition to the narrow oral cavity, the palatal shelves themselves were abnormally wide, deforming the shape of the tongue (Fig. 3B, E13.5, arrowheads). This narrowing of the upper part of the oral cavity in exencephalic Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutants was statistically significant when compared with either wildtype (WT) or non-exencephalic Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutants (Fig. 3E–G). At E15.5, Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutants with exencephaly are able to complete palatal shelf elevation and fusion (Fig. 3B), albeit the oral cavity remains narrower (Fig. 3B, E15.5, arrowheads) than those in wild-type (Fig. 3A) or Specc1lΔEx4/ΔEx4 mutants (Fig. 3D). Most homozygous Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutants without exencephaly showed permanent cleft palate (Fig. 3C, arrow). Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutants did not survive postnatally even those without exencephaly or cleft palate. All ΔCCD2 mutants (n = 4) showed subtle abnormalities in palatal shelf rugae formation at E18.5 (Fig. 3C, E18.5). Interestingly, Specc1lΔEx4/ΔEx4 mutants (100%, n = 4) showed the most drastic effect on palatal rugae formation, indicating an overall defect in palatogenesis (Fig. 3D, E18.5).

Figure 3 .

Exencephaly narrows the oral cavity allowing Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant palatal shelves to fuse. Wild-type (A), Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant with exencephaly (B), Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant without exencephaly (C) and Specc1lΔEx4/ΔEx4 null (D) embryos at embryonic day (E) 13.5, 15.5 and 18.5 are shown. At E13.5 and E15.5, coronal sections through the oral cavity were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. In the Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant with exencephaly (B) at E13.5, it is clear to see a narrowing of the oral cavity and the tongue (B, E13.5, arrowheads). Even at E15.5, the exencephalic mutant shows a narrowed dome-shaped palate and tongue (B, E15.5, arrowheads). At E18.5, embryonic palates are shown with the lower jaw removed. In addition, palatal rugae pattern at E18.5 is shown schematically. Measurements of the upper and lower regions of the oral cavity (E) in coronally sectioned E13.5 embryos showed that exencephalic Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 embryos have significant narrowing of the upper region of the oral cavity (F). There was no significant change in the lower region (G), which serves as an internal size control. p, palatal shelf; t, tongue; *, missing palatal rugae.

Heterozygotes for Specc1lΔCCD2 show autosomal dominant phenotypes and sex differences

The Specc1lΔCCD2 alleles were generated on a mixed C57BL/6J and FVB/NJ background. As we backcrossed the alleles to the C57BL/6J background, we noticed an occurrence of ventral body wall closure defect (10%), cleft palate (6%) and exencephaly (6%) in the heterozygotes (Fig. 2I; Supplementary Material, Table S1). This is consistent with the autosomal dominant manifestation of human SPECC1L CCD2 variants. Interestingly, so far we have only identified cleft palate in female Specc1lΔCCD2/+ heterozygotes (13%) and not in male heterozygotes (0%) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). This sex difference among heterozygotes was borderline for ventral body wall closure defects (13% female versus 8% male) and for exencephaly (4 versus 8%) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). Interestingly, as we further backcrossed the alleles onto C57BL/6J to ~N6, we noticed that we were rarely getting any female heterozygotes at weaning (data not shown). We are therefore maintaining the colony on a mixed C57BL/6J and FVB/NJ background. We also looked at male to female ratios in homozygous Specc1lΔCCD2 mutants and found a prevalence of cleft palate in male mutants (25% female versus 66% male; Supplementary Material, Fig. S4) and of exencephaly in female mutants (50% female versus 33% male). Again, a difference was not observed in homozygous Specc1lΔCCD2 mutants for ventral body wall closure defects (62% female versus 58% male). These results suggest an interplay between strain and sex differences along with autosomal dominance.

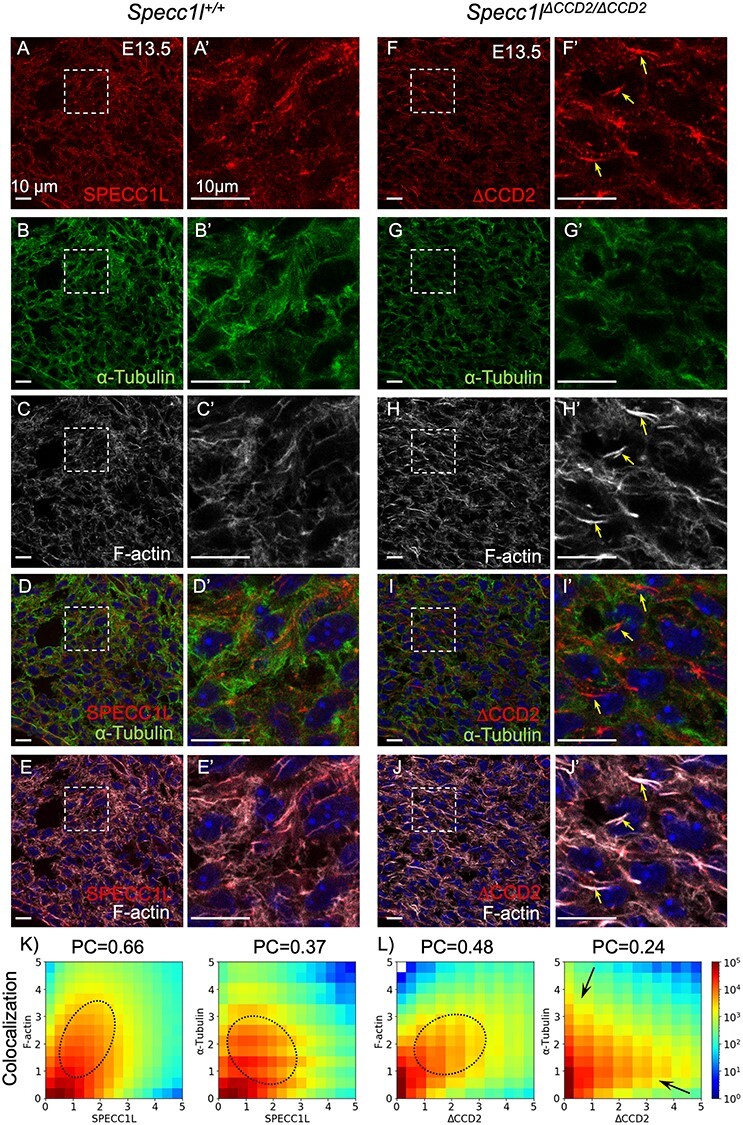

Abnormal cellular expression of SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein in palatal shelf mesenchyme

SPECC1L protein was broadly expressed in both the palatal shelf epithelium and mesenchyme. We have previously shown that SPECC1L expression was more prominent at cell–cell boundaries in epithelial cells (5,6). In Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant palatal shelf epithelium and periderm, we did not observe a striking difference in staining pattern or localization of SPECC1L, filamentous actin (F-actin) or microtubules (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5). However, in the palatal mesenchyme, we observed that SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein was not diffusely expressed throughout the cell and was instead concentrated in various regions of cells (Fig. 4A and A’ versus Fig. 4F and F’; arrows). We also previously showed that SPECC1L expression closely overlaps with F-actin staining (5,6). Consistently, both wild-type and SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 proteins showed co-localization with F-actin (Fig. 4E and E’ versus Fig. 4J and J’). However, there are many more, thick F-actin bundles in Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant palatal mesenchyme (Fig. 4F’ and J’; arrows). Overall, the fluorogram showed a moderate decrease in overlap with a reduced Pearson correlation value (Fig. 4K and L; 0.66 versus 0.48). In contrast, SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein showed much less co-localization with microtubules (Fig. 4D and D’ versus Fig. 4I and I’; arrows). This reduced overlap is also indicated by a bifurcated fluorogram for SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 and tubulin (Fig. 4K versus Fig. 4L; arrows) and a reduced Pearson correlation value (Fig. 4K and L; 0.37 versus 0.24). Microtubule immunostaining in the mutant tissue (Fig. 4G and G’ versus Fig. 4B and B’) appeared less intense; however, overall tubulin levels (Supplementary Material, Fig. S6) and microtubule staining in cultured mesenchymal cells (Fig. 5) did not show any differences. Reduced co-localization of ΔCCD2 protein with SPECC1L is consistent with our previous assertion that SPECC1L CCD2 helps the protein associate with microtubules (4,6,7). Thus, we argued that the gain-of-function underlying at least the palate elevation defect in Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutants mainly affected palatal shelf mesenchyme.

Figure 4 .

Abnormal cellular expression of SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 in E13.5 palatal shelf mesenchyme. (A–J) Wild-type Specc1l+/+ (A–E, A’–E’) and Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant (F–J, F’–J’) embryonic day (E) 13.5 cryosections were co-stained with antibodies against SPECC1L (A, A’, F, F′) and α-tubulin (B, B’, G, G’), and with phalloidin (C, C’, H, H’). A’–J’ are magnified regions that are boxed in the corresponding A–J. Wild-type SPECC1L (A, A’) shows an evenly distributed subcellular expression that strongly overlaps with both microtubules (D, D’) and filamentous actin (E, E’). In contrast, mutant SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 (F, F’) shows an abnormal expression pattern that appears to be clustered in subcellular regions (arrows). This clustered expression of the mutant SPECC1L shows reduced co-localization with microtubules (I, I’, increased red staining), and results in abnormal bundles of F-actin (J, J’). Scale bars = 10 μm. (K–L) Fluorograms (pixel distribution diagrams) depicting the frequency of pixels with various compositions of immunofluorescence (K, L). The immunofluorescence values are normalized to the intensity averaged over the entire field of view. The Pearson correlation coefficient (PC) characterizes the degree of co-localization of the corresponding sample. Wild-type SPECC1L immunofluorescence shows a tighter (diagonal) association with both F-actin and tubulin (K) compared with that of the CCD2 mutant (L). In particular, overlap of mutant SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein with tubulin is drastically reduced (L, arrows). Ovals indicate the approximate area of the diagram corresponding to co-localized immunofluorescence, arrows point to groups of pixels where only one of the immunofluorescence is present.

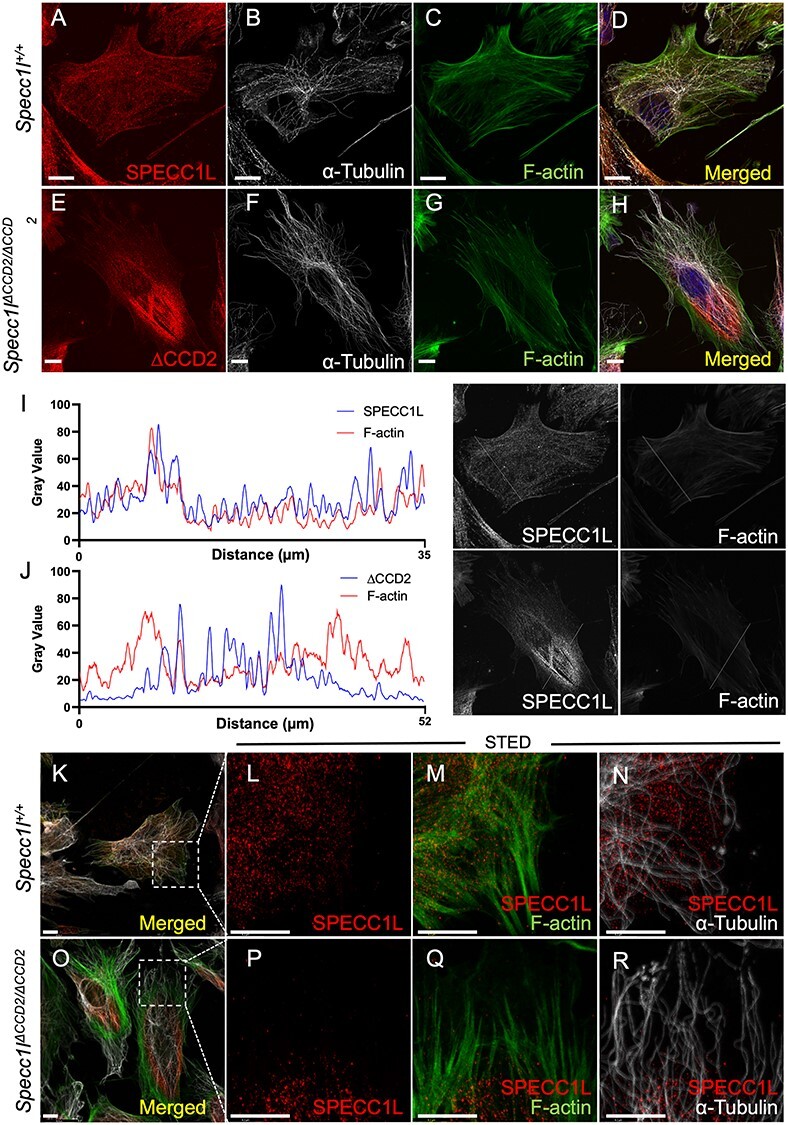

Figure 5 .

SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 shows abnormal perinuclear localization in primary mouse embryonic palatal mesenchyme cells. Primary mouse embryonic palatal mesenchyme (MEPM) cells were isolated from wild-type (A–D, K–N) and Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant (E–H, O–R) embryonic day (E) 13.5 embryos. Images A–H are maximum intensity projections of confocal z-stacks, whereas images K–R are confocal planes. MEPM cells were co-stained with antibodies against SPECC1L and α-tubulin, and with phalloidin as indicated. Merged images with DAPI are also shown (D, H). SPECC1L shows an evenly distributed subcellular expression pattern in wild-type MEPMs (A, D) that greatly overlaps with both microtubules (B, D) and actin filaments (F-actin; C, D). In contrast, ΔCCD2 protein in mutant MEPMs is clustered in a perinuclear region (E, H) with reduced overlap with either microtubules (F, H) or F-actin (G, H). The abnormal expression pattern of SPECC1L and F-actin in the mutant MEPMs was further confirmed using line scans through images in A and E. The line scan through wild-type MEPM cell (I) clearly showed similar pattern SPECC1L and F-actin expression, indicating an equilibrium. In contrast, the line scan through the mutant cell (J) shows clustering of the mutant protein in the middle of the cell, which resulted in an increase in F-actin at the outer edges of the cell. To better characterize the co-staining, super-resolution STED images were taken (L-N, P-R) of the boxed regions shown in K (wild-type) and O (ΔCCD2 mutant). STED images show a strong overlap between SPECC1L and F-actin (M, Q). Interestingly, regions of SPECC1L overlap in both wild-type and mutant cells show reduced F-actin staining. With microtubules, wild-type SPECC1L shows considerable overlap (N) compared with ΔCCD2 mutant (R). However, the main difference is an inability of mutant ΔCCD2 protein to distribute throughout the cytoplasm. Scale bars = 10 μm.

CCD2 is required for subcellular distribution of SPECC1L

To further assess the subcellular mesenchymal effects of SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein, we isolated primary mouse embryonic palatal mesenchyme (MEPM) cells from E13.5 wild-type and Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant embryos (10). Time-lapse imaging of wild-type and mutant MEPM cell cultures revealed that ΔCCD2 mutant cells exhibited a statistically significant deficit in their ability to form streams, an attribute of collective cell motility (Supplementary Material, Fig. S7). This deficit in collective cell motility was consistent with our previous studies in SPECC1L-deficient MEPM cells (10). At the cellular level, wild-type SPECC1L showed a diffuse punctate expression pattern (Fig. 5A), which closely mimicked F-actin expression pattern (Fig. 5C). In contrast, SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein showed an abnormal perinuclear aggregation (Fig. 5E). This abnormal perinuclear aggregation was even more vivid in migrating MEPM cells in a wound repair assay (Supplementary Material, Fig. S8). Although the mutant protein still co-localized with F-actin (Fig. 5H), there appeared to be a drastic decrease in F-actin staining in the perinuclear region where the SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein had aggregated (Fig. 5E, G, H). We confirmed our observation through a series of line scans through the images (Fig. 5I and J; Supplementary Material, Fig. S9). The line scans through WT cells showed even distribution of both SPECC1L protein and actin filaments (Fig. 5I; Supplementary Material, Fig. S9), which we argue are in equilibrium. In contrast, mutant SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein shows increased expression in the central region of the cell, whereas F-actin shows increased staining at the cell periphery (Fig. 5J; Supplementary Material, Fig. S9). Super-resolution stimulated emission depletion (STED) imaging revealed a general association of both WT (Fig. 5M) and mutant (Fig. 5Q) SPECC1L expression and actin filaments with reduced intensity. The microtubule expression pattern in cultured wild-type and mutant MEPM cells did not appear altered (Fig. 5B versus Fig. 5F; Fig. 5N versus Fig. 5R). However, in contrast to WT MEPM cells (Fig. 5N), there are clear regions of microtubules devoid of SPECC1L protein in mutant MEPM cells (Fig. 5R). Thus, we propose that SPECC1L protein requires its CCD2-based association with microtubules for intracellular trafficking and distribution. Furthermore, abnormal subcellular aggregation of SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein largely affected the actin cytoskeleton organization.

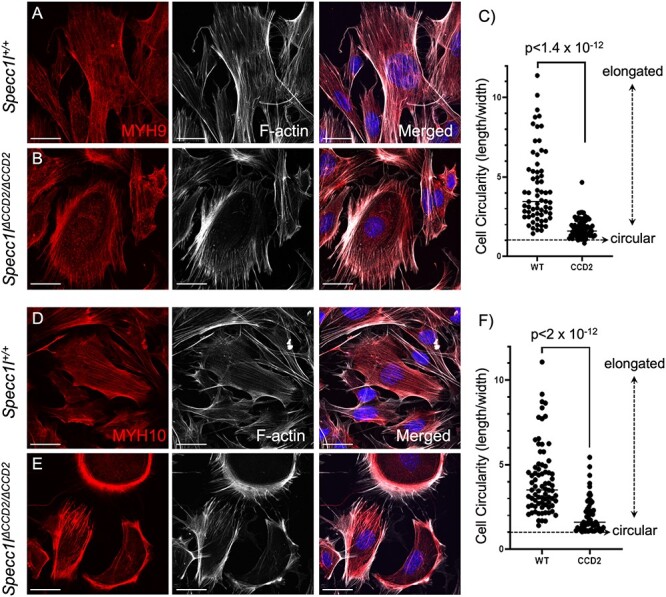

Abnormal staining of non-muscle myosin II in Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 MEPM cells

Non-muscle myosin II (NM-II) family consists of three types—A, B and C—that are distinguished by three heavy chains encoded by Myh9 (NM-IIA), Myh10 (NM-IIB) and Myh14 (NM-IIC), respectively (11,12). Although NM-IIC is not expressed in the palate during development, both NM-IIA and NM-IIB have been implicated in palatogenesis (13) and the etiology of cleft palate (14–16). We looked at expression of both MYH9 and MYH10 in wild-type and Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant MEPM cells. We observed that both MYH9 (Fig. 6A and B) and MYH10 (Fig. 6D and E) expression pattern was abnormal in mutant MEPM cells. There was a particularly increased localization of both NM-IIA and NM-IIB to cell periphery. There was also a change in cell shape, with many mutant MEPM cells being more circular (Fig. 6C and F). We also extended our analysis to the palate mesenchyme (Supplementary Material, Fig. S10) and found a similarly altered expression to the cell periphery of both MYH9 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S10A versus Supplementary Material, Fig. S10F) and MYH10 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S10K versus Supplementary Material, Fig. S10P). There also appeared to be reduced co-localization with microtubules of both NM-IIA (Supplementary Material, Fig. S10D versus Supplementary Material, Fig. S10I; arrows) and NM-IIB (Supplementary Material, Fig. S10N versus Supplementary Material, Fig. S10S; arrow), which was also evident with less diagonal pattern on the fluorograms and reduced Pearson correlation values (Supplementary Material, Fig. S10U and V).

Figure 6 .

Abnormal non-muscle myosin II expression in Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant primary mouse embryonic palatal mesenchyme cells. Wild-type (A, D) and Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant (B, E) primary mouse embryonic palatal mesenchyme (MEPM) cells were co-stained with antibodies against non-muscle myosin IIA (NM-IIA) component MYH9 (A, B) or with NM-IIB component MYH10 (D, E), and with phalloidin marking filamentous actin (F-actin). Merged images are shown with DAPI. Wild-type MYH9 (A) and MYH10 (D) show a uniform subcellular expression pattern that overlaps F-actin staining. In contrast, in mutant MEPM cells, both MYH9 (B) and MYH10 (E) show an abnormal clustered expression at the cell periphery along with F-actin. Compared with wild-type MEPM cells (A, D), the mutant MEPM cells also show a more rounded appearance (B, E). This circularity was measured as a ratio of length/width with one being circular or cuboidal (C, F). Compared with wild-type cells, the mutant cells showed much lower ratios (C, F), indicating increased circularity. Scale bars = 10 μm.

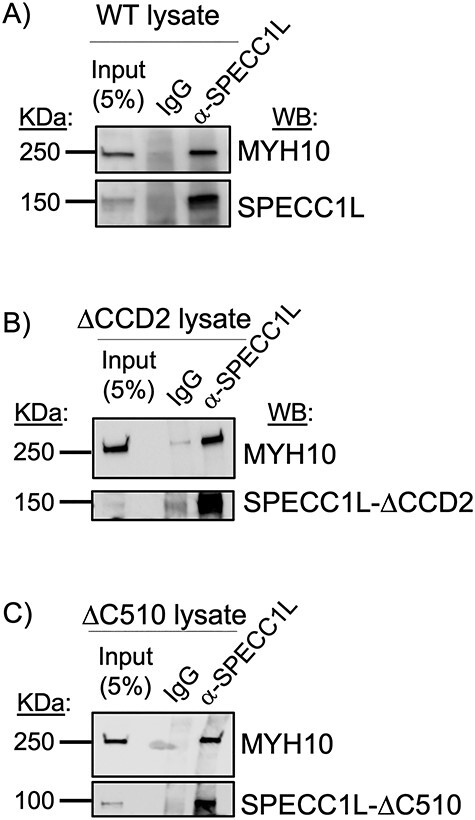

NM-IIB co-immunoprecipitates with SPECC1L

Given the altered expression pattern of NM-IIA and NM-IIB in Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant MEPM cells and tissue, we wanted to know if wild-type or mutant SPECC1L associated with NM-II. We immunoprecipitated SPECC1L protein from wild-type, Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 and Specc1lΔC510/ΔC510 embryonic tissue (Fig. 7). Wild-type SPECC1L strongly co-immunoprecipitated NM-IIB (Fig. 7A) as well as NM-IIA (not shown), showing an association in vivo. Interestingly, Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant protein also co-immunoprecipitated NM-IIB (Fig. 7B), indicating that its association with SPECC1L was not via CCD2. Therefore, we tested lysate from Specc1lΔC510/ΔC510 mutants lacking the C-terminal CHD. The SPECC1L-ΔC510 protein also co-immunoprecipitated NM-IIB (Fig. 7C), suggesting that there was a novel interaction domain for NM-IIB possibly in the N-terminal region of SPECC1L.

Figure 7 .

SPECC1L associates with NM-IIB component MYH10. Wild-type (A), Specc1lΔCCD2/ΔCCD2 mutant (B) and Specc1lΔC510/ΔC510 mutant (C) tissue lysate was used in co-immunoprecipitation assays using α-SPECC1L N-term antibody or IgG negative control; 5% input is shown as control. MYH10 was co-immunoprecipitated from WT, ΔCCD2 (lacking CCD2 domain) mutant and ΔC510 (lacking C-terminal CHD) mutant lysates. Thus, SPECC1L interaction with NM-IIB is not via CCD2 or CHD, but rather via a novel, yet unidentified N-terminal domain. WB, western blot.

Discussion

Patients with autosomal dominant SPECC1L variants show several structural birth defects including omphalocele and cleft palate (9). Yet in mice, we showed that a loss of the C-terminal region with CHD (6) or even a complete absence of SPECC1L protein (Fig. 1) did not result in these defects at birth. We hypothesized that these autosomal dominant variants that largely cluster in CCD2 are gain-of-function. We generated two mouse alleles with in-frame deletions in CCD2 (Fig. 1). Homozygous mutants for these in-frame ΔCCD2 deletions showed highly penetrant omphalocele and cleft palate, confirming our hypothesis that CCD2 perturbations are gain-of-function.

Furthermore, some ΔCCD2 heterozygous mutants also showed cleft palate. Interestingly, all ΔCCD2 heterozygous mutants with cleft palate were female. This is important since, in humans, non-syndromic cleft palate only phenotype is observed more often in females (~1.41 times) than in males (17,18). We also observed an effect of background strain on the survival of ΔCCD2 heterozygotes, especially females. Together, these results indicate that our mouse Specc1lΔCCD2 alleles aptly model the human condition.

Homozygous in-frame ΔCCD2 mutants also showed highly penetrant exencephaly and coloboma. Although cleft palate and omphalocele have been frequently observed in known patients with SPECC1L variants, exencephaly and coloboma are not. Coloboma was only observed in a small subset of homozygous mutants, and not in heterozygous mutants, thus suggesting that optic fissure closure may not be sensitive to one copy of the CCD2 mutation. In contrast, the main reason for absence of exencephaly in the patients identified to-date is likely selection bias. The current patient cohort was initially identified based on SPECC1L association with craniofacial anomalies (4,7) and then with omphalocele (8). Fetuses with exencephaly fail to survive postnatally and are not currently associated with SPECC1L variants.

SPECC1L appears to affect the efficiency of several embryonic tissue movement and fusion events. Several pieces of evidence for this efficiency argument come from our study of palatogenesis in various Specc1l alleles. First is the incomplete penetrance of the various defects of fusion events in ΔCCD2 mutants. Another is that in SPECC1L truncation (6) and null (Fig. 2) alleles, there is no cleft palate at birth, indicating that SPECC1L is not required for the process, but there is a demonstrable delay in palatal shelf elevation (6). We hypothesize that this elevation delay is more severe in in-frame ΔCCD2 mutants, which results in cleft palate at birth. A good case in point for this hypothesis is the absence of cleft palate in ΔCCD2 mutant embryos with exencephaly where the oral cavity is narrowed due to the loss of the cranium. According to our hypothesis, even with reduced efficiency in elevation, palatal shelves are able to fuse as they have a shorter distance to cover. An important corollary to this argument is that even subtle variants in SPECC1L may affect this efficiency enough to function as genetic modifiers. This is consistent with our identification of SPECC1L variants in patients with non-syndromic cleft lip/palate with subtle functional consequences (6) compared with variants identified in syndromic cases (4,7). We propose that the same would be true in other defective fusion events affecting the neural tube, ventral body wall and eye.

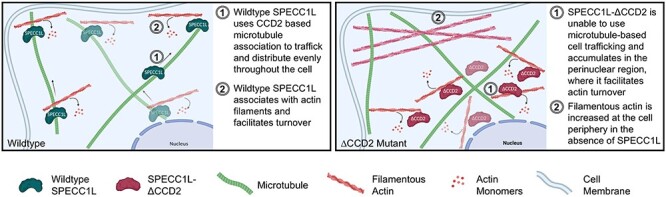

The basis for this reduced efficiency in the SPECC1L-deficient palate is likely poor vertical to horizontal remodeling during elevation (10). Several cellular mechanisms for this mesenchymal remodeling have been proposed (19–22). Cell proliferation is required, but not sufficient (23–25); however, migratory properties, potentially guided by WNT5A and FGF10 chemotactic gradients (26), may be needed for elevation to occur. We posited that, at the cellular level, SPECC1L deficiency leads to poor cell alignment and motility (10), two key elements of coordinated movement that can affect this remodeling. At the molecular level, the ability of SPECC1L to associate with both microtubules and actin via CCD2 and CHD, respectively, underlies its function. We had hypothesized that CCD2 based association with microtubules was critical, as most human variants clustered in this domain; however, the significance of the microtubule association was not evident. Previous in vitro assays suggested an ability to promote acetylation or stability of a subset of microtubules (4,6). Our data now show that while there is some reduction or mislocalization of microtubules in ΔCCD2 mutants, the main effect of CCD2 perturbation is an inability of SPECC1L to evenly distribute within the cell cytoplasm (Fig. 8). There can be several reasons for the mutant protein to cluster—for example, SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein may be tethered to the regions where it is expressed or degraded near the periphery of the cell. However, given the association of CCD2 with microtubules, we propose that SPECC1L is using microtubule-based trafficking to move throughout the cell potentially through association with kinesin motor proteins. Furthermore, the subcellular regions, where the mutant SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein aggregates, are conspicuously devoid of strongly staining actin filaments. Conversely, there is an increase in F-actin staining at the mutant cell periphery lacking the SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein. These observations are consistent with a role for SPECC1L in actin depolymerization or turnover, and with our previous reports of increased F-actin staining in SPECC1L-deficient cells (5,6).

Figure 8 .

Model for SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 dysfunction. Wild-type SPECC1L protein (left) is expressed uniformly throughout the cytoplasm and is found associated with actin filaments that stain lightly with phalloidin, indicating a role in filamentous actin turnover. In contrast, SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 protein expression (right) is clustered in the perinuclear region. This accumulation leads to a severe reduction in filamentous actin staining in the perinuclear region and a drastic increase in actin filaments towards the cell periphery. Thus, our data suggest that SPECC1L requires association with the microtubules via CCD2 for trafficking within the cell and that clustered accumulation of SPECC1L-ΔCCD2 leads to a disorganized actin cytoskeleton affecting cell alignment and motility. Schematic created with BioRender.com.

The subcellular misorganization of F-actin in ΔCCD2 mutant cells also provides a cellular basis for the gain-of-function. We have previously shown that SPECC1L deficiency leads to increased actin filament staining (4,5). However, this increase is uniformly spread out in the mutant cell. In contrast, in ΔCCD2 mutant cells, the clustered mutant protein is still able to turnover actin, which results in subcellular regions within the same cell with too much and too little actin filaments. This abnormal subcellular pattern with peripheral increase and perinuclear decrease in F-actin can be considered a toxic gain-of-function, compared even with Specc1l null cells. We do not yet have any conclusive evidence that SPECC1L functions as a dimer or multimer, but we hypothesize that this same toxic gain-of-function can sometimes result in phenotypes in heterozygotes.

Given our findings with actin cytoskeletal changes, we looked at NM-IIA and NM-IIB. NM-IIA (MYH9) has been implicated in association studies with non-syndromic CL/P (14–16) and in palatogenesis (13). Interestingly, similarly to Specc1l, NM-IIB (Myh10) null allele did not show cleft palate or omphalocele (11), whereas an Myh10 allele with a point mutation showed cleft palate, omphalocele and other structural birth defects (16). We observed an abnormal NM-IIA and IIB staining pattern towards the periphery of mutant MEPM cells, likely associated with branched actin filaments. We also observed a general rounding of mutant MEPM cells, which is consistent with a decrease in cytoplasmic association of NM-II with central long anti-parallel actin filaments. Most importantly, we show that SPECC1L physically associates with NM-II, independent of either the CCD2 (microtubule) or CHD (actin) domains. This result further establishes SPECC1L as a cytoskeletal scaffolding protein.

Our previous analysis with Specc1l-deficient alleles placed Specc1l downstream of Interferon Regulatory Factor 6 (Irf6) and showed oral epithelial defects including oral adhesions and ectopic apical misexpression of adhesion molecules in the periderm (6). However, the defects in Specc1l deficient of null alleles are not limited to the oral epithelium. We recently showed that Specc1l-deficient primary MEPM cells have migration and directed motility defects (10). The IRF6-Transcription Factor AP-2 Alpha (TFAP2A)-Grainyhead Like Transcription Factor 3 (GRHL3) pathway has been shown to play an important role in both neural tube and palate closure (27). In addition, Tfap2a and GRHL family member Grhl2 mutants show ventral body wall closure defects (28,29). Although the IRF6-TFAP2A-GRHL3 pathway functions primarily in the ectoderm, there is evidence that it also affects the mesoderm (30). Consistent with this observation, in Irf6 null palatal shelves, SPECC1L expression was reduced in both the epithelium and mesenchyme (6). Thus, it is important to note that while our analysis of the palatal shelves in Specc1lΔCCD2 alleles did not show any drastic oral epithelial changes, it does not mean that the ectoderm is not affected. As a first-order analysis, we have looked at F-actin staining during both neural tube (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1G–N) and ventral body wall (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2G and H) closure. In both cases, WT embryos show strong supracellular alignment of actin cables, whereas the mutant embryos show diminished organization. Poor supracellular alignment of actin filaments has been implicated previously in neural tube closure defects (31,32). In conclusion, by organizing cellular actin and myosin, SPECC1L may participate in the global alignment of actomyosin-based forces that play a critical role in time-sensitive embryonic tissue movement and fusion events.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Specc1l alleles

The general scheme for the CRISPR-based generation of Specc1l alleles is described in Fig. 1. Briefly, to generate the ΔEx4 null allele, two gRNAs flanking exon 4 (Fig. 1A and B) were introduced directly in F1 hybrid (C57Bl/6J:FVB/NJ) zygotes at 2–4 cell stage. Successful targeting was confirmed in the founders using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based loss of exon 4. The CCD2 specific alleles were generated using a single gRNA located in CCD2 in exon 4 (Fig. 1A and B). Progeny from founders were sequenced for in-frame deletions. Three of the in-frame deletions (Δ234, Δ576, Δ411 base pairs) were established as mouse lines and further analyzed (Fig. 1C–G).

Mouse embryo processing and histological analysis

Timed matings were set up overnight and checked for plugs the following morning. The embryos were classified as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5) at noon on the day that the plug was identified. At the desired embryonic time point, the pregnant females were euthanized using methods approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Embryos were harvested, washed in 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Prior to fixation, whole-embryo bright-field images were obtained using a Nikon SMZ 1500 stereomicroscope. Yolk sacs were taken at the time of harvesting for genotyping. Sex was determined by PCR using primers flanking an 84 bp deletion of the Rbm31x gene relative to its gametolog Rbm31y (Forward: CACCTTAAGAACAAGCCAATACA; Reverse: GGCTTGTCCTGAAAACATTTGG). A single product (269 bp) was amplified in female subjects and two products (269 bp; 353 bp) amplified in male subjects (33). Whole-mount 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining of the palate was achieved by decapitating fixed embryos, removing the lower jaw and incubating the exposed palates in 500–1000 nM DAPI solution overnight, then imaging on Nikon SMZ 1500 stereomicroscope. Fixed embryo heads were paraffin processed using Leica ASP300, embedded in paraffin blocks and coronally sectioned. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed on these sections and imaged using the EVOS FL Auto microscope. For cryosectioning, fixed embryo heads were submerged in 20% sucrose until the tissue sank, embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) media, coronally sectioned at a thickness of 10 μm, then stored at −80°C until immunostained.

MEPM isolation and culture

MEPM isolation was performed as described previously (10). Briefly, harvested E13.5 mouse embryos were decapitated, the lower jaw and tongue were removed, the palatal shelves were excised and incubated in 0.25% trypsin (ThermoFisher, 25200056) at 37°C for 10 min. The resulting MEPM cells were resuspended in DMEM high glucose supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Corning, 35-010-CV), 40 mM L-glutamine (Cytiva, SH30243.01) and 50 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Corning, 30-002-CI). MEPMs were plated into six-well plates and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Culture media was changed daily until the cells reached confluency, whereupon they were cryopreserved. For immunostaining, cells were thawed and seeded at the appropriate density.

Spontaneous collective motility assay

For the analysis of stream formation and collective motility, MEPM cells were seeded at high (450–900/mm2) densities into selected areas of six-well plates, delimited by silicone insert rings (Ibidi, 80209). Cultures were live imaged every 10 min with a 4× phase contrast objective. The local spatial correlations of cell movements were characterized by the average flow field that surrounds moving cells as described in (10,34,35). Briefly, cell motility was estimated using a particle image velocimetry algorithm, with an initial window size of 50 μm (10,36,37), resulting in velocity vectors at each frame and image location. A reference system was then aligned to each vector and adjacent vectors were registered in the appropriate bin (front, rear, etc.). The average velocity vector in each bin was used as a measure of spatial correlation. The calculated average co-movement vectors were fitted with an exponential function across the front–rear and left–right axes to obtain the correlation length: the characteristic distance local correlations in cell velocity disappear.

Western blotting

Protein was extracted by sonicating embryonic tissue in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer with Halt™ protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, 78440). Protein concentrations were quantified using Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Scientific, 23227). Samples were electrophoresed using Mini-Protean TGX Stain-Free 4–15% gradient pre-cast polyacrylamide gels (Bio-RAD, #4568084). After electrophoresis, the stain-free gel was activated by exposing to ultraviolet light for 45 s using the ChemiDoc MP imaging system (BioRad). This allows for fluorescent detection of total protein, which was quantitated using ImageLab software (BioRad). The protein was then transferred to an Immobilon polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (EMD Millipore, IPVH00010). Membranes were blocked using Odyssey Blocking Buffer (Li-Cor, 927-5000) for 1–2 h at room temperature (RT), incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, secondary antibody (1:10 000; Cell Signaling Technologies) for 1 h at RT and developed using Femto Super Signal West ECL reagent (Thermo Scientific, 34095). Membranes were imaged and analyzed using ChemiDoc MP imaging system (BioRad) and Imagelab software (BioRad). Primary antibodies used SPECC1L (1:2000; Proteintech, 25 390-1-AP), MYH10 (1:1000; Sigma, M7939) and HRP-conjugated beta-actin (1:5000, UBPBio, Y1059).

Immunofluorescence

For MEPM immunostaining, cells were grown on poly-lysine-coated glass coverslips and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at RT. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Trixon X-100 in 1× PBS for 10 min, washed with PBS 3× and blocked in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 50062Z) for 2 h at RT. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C, washed in 1× PBS, then incubated in secondary antibody for 2 h and DAPI and/or F-actin stain for 30 min at RT. Stained coverslips were mounted on slides with Prolong Gold Antifade Mounting medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, P10144). For ∆Np63 and β-catenin, an antigen retrieval protocol was followed by heating slides in sodium citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0) at 96°C for 10 min. Slides were washed in H2O and PBS, permeabilized using 0.5% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS for 30 min, washed in PBS again, then blocked in 10% NGS. Primary and secondary antibodies were incubated following the same method as described above. Images were acquired using either an EVOS FL Auto Inverted Imaging System or Leica SP8 STED 3× white light laser (WLL) confocal microscope. Primary antibodies: SPECC1L N-terminus (1:500 cells, 1:250 tissue Proteintech, 25390-1-AP), α-tubulin (1:100, 1:500 cells, 1:1000 tissue, Sigma, T9026), ∆Np63 (1:100, Biolegend, 619001), β-catenin (1:500 Cell Signaling Technology; 2677), MYH9 NM-IIA (1:100 Proteintech, 11128-1-AP), MYH10 NM-IIB (1:100 Sigma, M7939). Secondary antibodies and stains: Goat anti-Rabbit Immunoglobulin G (IgG) (H + L) Alexa 488 and 594 (1:1000 cells, 1:500 tissue Invitrogen; A-11008, A-11012), Goat anti-Mouse IgG1 Alexa 488 (1:500 Invitrogen, A-21121), Goat anti-Mouse IgG1 Alexa 680 (Jackson Immuno, 1156255205), Acti-stain 555 phalloidin (1:140, Cytoskeleton, PHDH1-A), Actin-stain 670 phalloidin (1:140, Cytoskeleton, PHDN1-A), DAPI (5 μM).

Immunoprecipitation

Protein was extracted by sonicating embryonic tissue in a lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl, 1% NP-40, 131 mM NaCl, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 10% glycerol. To prevent non-specific binding to the protein beads, the lysate was pre-cleared by incubating with Dynabeads Protein G (Invitrogen, 100-03D) for 4 h at 4°C while rocking. For each sample, equal volume of lysate was incubated with 1 μg of either SPECC1L N-terminus antibody (Proteintech, 25390-1-AP) or Normal Rabbit IgG control antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, 2729S). Dynabeads Protein G were added to the lysate/antibody mixture and incubated overnight at 4°C while rocking. The beads were washed with ice cold lysis buffer three times. Lysis buffer containing 5× Laemmli buffer with 10% 2-Mercaptoethanol (Sigma, M3148) was added to the beads, and then electrophoresed on polyacrylamide gels as described above for western blotting.

Image quantitation and analyses

Oral cavity measurements were taken from E13.5 H&E- and DAPI-stained palatal sections. Points along the upper and lower portions of the medial aspect of the palatal shelves were manually selected, and then measured using the Measure tool in Fiji ImageJ. Distribution of immunofluorescence in MEPM cells was analyzed using Plot Profile plugin of ImageJ. Two independent lines were measured through each cell, and the normalized immunofluorescence was plotted on a graph. Cell circularity was determined by taking the ratio of cell length over width. Co-localization of cytoskeletal components was analyzed using JaCoP Plugin of ImageJ (38) as well as by the Python Imaging Library. Statistical comparisons were performed using Prism GraphPad software and by the SciPy and Matplotlib Python packages.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Jeremy P Goering, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA.

Luke W Wenger, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA.

Marta Stetsiv, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA.

Michael Moedritzer, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA.

Everett G Hall, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA.

Dona Greta Isai, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA.

Brittany M Jack, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA.

Zaid Umar, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA.

Madison K Rickabaugh, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA.

Andras Czirok, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA; Department of Biological Physics, Eotvos University, Budapest 1053, Hungary.

Irfan Saadi, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA.

Authors’ Contributions

J.P.G., L.W.W., M.S., A.C. and I.S. conceived and designed the experiments. J.P.G., L.W.W., M.S., M.M., E.G.H., D.G.I., B.M.J., Z.U. and M.K.R. performed the experiments. D.G.I. and A.C. performed the time-lapse imaging analysis. J.P.G., M.S., A.C. and I.S. wrote the paper. L.W.W., M.M., B.M.J. and M.K.R. edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest statement. The authors do not have any competing financial interests pertaining to the studies presented here.

Funding

This project was supported in part by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) (grants DE026172 to I.S., F31DE027284 to E.H.) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) (grant GM102801 to A.C.). I.S. was also supported in part by the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) grant NIGMS P20 GM104936), Kansas IDeA Network for Biomedical Research Excellence grant (NIGMS P20 GM103418) and Kansas Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (KIDDRC) grant [U54 Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), HD090216]. The Confocal Imaging Facility, the Integrated Imaging Core and the Transgenic and Gene Targeting Institutional Facility at the University of Kansas Medical Center are supported, in part, by NIH/NIGMS COBRE (grant P30GM122731) and by NIH/NICHD KIDDRC (grant U54HD090216). The Leica STED microscope was supported by NIH (1S10OD023625).

References

- 1. Martin, P. and Wood, W. (2002) Epithelial fusions in the embryo. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 14, 569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ray, H.J. and Niswander, L. (2012) Mechanisms of tissue fusion during development. Development, 139, 1701–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mai, C.T., Isenburg, J.L., Canfield, M.A., Meyer, R.E., Correa, A., Alverson, C.J., Lupo, P.J., Riehle-Colarusso, T., Cho, S.J., Aggarwal, D. et al. (2019) National population-based estimates for major birth defects, 2010-2014. Birth Defects Res., 111, 1420–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saadi, I., Alkuraya, F.S., Gisselbrecht, S.S., Goessling, W., Cavallesco, R., Turbe-Doan, A., Petrin, A.L., Harris, J., Siddiqui, U., Grix, A.W., Jr. et al. (2011) Deficiency of the cytoskeletal protein SPECC1L leads to oblique facial clefting. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 89, 44–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilson, N.R., Olm-Shipman, A.J., Acevedo, D.S., Palaniyandi, K., Hall, E.G., Kosa, E., Stumpff, K.M., Smith, G.J., Pitstick, L., Liao, E.C. et al. (2016) SPECC1L deficiency results in increased adherens junction stability and reduced cranial neural crest cell delamination. Sci. Rep., 6, 17735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hall, E.G., Wenger, L.W., Wilson, N.R., Undurty-Akella, S.S., Standley, J., Augustine-Akpan, E.A., Kousa, Y.A., Acevedo, D.S., Goering, J.P., Pitstick, L. et al. (2020) SPECC1L regulates palate development downstream of IRF6. Hum. Mol. Genet., 29, 845–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kruszka, P., Li, D., Harr, M.H., Wilson, N.R., Swarr, D., McCormick, E.M., Chiavacci, R.M., Li, M., Martinez, A.F., Hart, R.A. et al. (2015) Mutations in SPECC1L, encoding sperm antigen with calponin homology and coiled-coil domains 1-like, are found in some cases of autosomal dominant Opitz G/BBB syndrome. J. Med. Genet., 52, 104–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhoj, E.J., Li, D., Harr, M.H., Tian, L., Wang, T., Zhao, Y., Qiu, H., Kim, C., Hoffman, J.D., Hakonarson, H. et al. (2015) Expanding the SPECC1L mutation phenotypic spectrum to include Teebi hypertelorism syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A, 167A, 2497–2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhoj, E.J., Haye, D., Toutain, A., Bonneau, D., Nielsen, I.K., Lund, I.B., Bogaard, P., Leenskjold, S., Karaer, K., Wild, K.T. et al. (2018) Phenotypic spectrum associated with SPECC1L pathogenic variants: new families and critical review of the nosology of Teebi, Opitz GBBB, and Baraitser-Winter syndromes. Eur. J. Med. Genet., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goering, J.P., Isai, D.G., Hall, E.G., Wilson, N.R., Kosa, E., Wenger, L.W., Umar, Z., Yousaf, A., Czirok, A. and Saadi, I. (2021) SPECC1L-deficient primary mouse embryonic palatal mesenchyme cells show speed and directionality defects. Sci. Rep., 11, 1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ma, X. and Adelstein, R.S. (2014) The role of vertebrate nonmuscle myosin II in development and human disease. BioArchitecture, 4, 88–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Newell-Litwa, K.A., Horwitz, R. and Lamers, M.L. (2015) Non-muscle myosin II in disease: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Dis. Model. Mech., 8, 1495–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim, S., Lewis, A.E., Singh, V., Ma, X., Adelstein, R. and Bush, J.O. (2015) Convergence and extrusion are required for normal fusion of the mammalian secondary palate. PLoS Biol., 13, e1002122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chiquet, B.T., Hashmi, S.S., Henry, R., Burt, A., Mulliken, J.B., Stal, S., Bray, M., Blanton, S.H. and Hecht, J.T. (2009) Genomic screening identifies novel linkages and provides further evidence for a role of MYH9 in nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. Eur. J. Hum. Genet., 17, 195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Birnbaum, S., Reutter, H., Mende, M., de Assis, N.A., Diaz-Lacava, A., Herms, S., Scheer, M., Lauster, C., Braumann, B., Schmidt, G. et al. (2009) Further evidence for the involvement of MYH9 in the etiology of non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Eur. J. Oral Sci., 117, 200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ma, X. and Adelstein, R.S. (2014) A point mutation in Myh10 causes major defects in heart development and body wall closure. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet., 7, 257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Michalski, A.M., Richardson, S.D., Browne, M.L., Carmichael, S.L., Canfield, M.A., VanZutphen, A.R., Anderka, M.T., Marshall, E.G. and Druschel, C.M. (2015) Sex ratios among infants with birth defects, National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997-2009. Am. J. Med. Genet. A, 167A, 1071–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rittler, M., Lopez-Camelo, J. and Castilla, E.E. (2004) Sex ratio and associated risk factors for 50 congenital anomaly types: clues for causal heterogeneity. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol., 70, 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bush, J.O. and Jiang, R. (2012) Palatogenesis: morphogenetic and molecular mechanisms of secondary palate development. Development, 139, 231–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lan, Y., Xu, J. and Jiang, R. (2015) Cellular and molecular mechanisms of palatogenesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol., 115, 59–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li, C., Lan, Y., Krumlauf, R. and Jiang, R. (2017) Modulating Wnt signaling rescues palate morphogenesis in Pax9 mutant mice. J. Dent. Res., 96, 1273–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gritli-Linde, A. (2008) The etiopathogenesis of cleft lip and cleft palate: usefulness and caveats of mouse models. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol., 84, 37–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jin, J.Z., Li, Q., Higashi, Y., Darling, D.S. and Ding, J. (2008) Analysis of Zfhx1a mutant mice reveals palatal shelf contact-independent medial edge epithelial differentiation during palate fusion. Cell Tissue Res., 333, 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kouskoura, T., Kozlova, A., Alexiou, M., Blumer, S., Zouvelou, V., Katsaros, C., Chiquet, M., Mitsiadis, T.A. and Graf, D. (2013) The etiology of cleft palate formation in BMP7-deficient mice. PLoS One, 8, e59463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lan, Y., Zhang, N., Liu, H., Xu, J. and Jiang, R. (2016) Golgb1 regulates protein glycosylation and is crucial for mammalian palate development. Development, 143, 2344–2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. He, F., Xiong, W., Yu, X., Espinoza-Lewis, R., Liu, C., Gu, S., Nishita, M., Suzuki, K., Yamada, G., Minami, Y. et al. (2008) Wnt5a regulates directional cell migration and cell proliferation via Ror2-mediated noncanonical pathway in mammalian palate development. Development, 135, 3871–3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kousa, Y.A., Zhu, H., Fakhouri, W.D., Lei, Y., Kinoshita, A., Roushangar, R.R., Patel, N.K., Agopian, A.J., Yang, W., Leslie, E.J. et al. (2019) The TFAP2A-IRF6-GRHL3 genetic pathway is conserved in neurulation. Hum. Mol. Genet., 28, 1726–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang, J., Hagopian-Donaldson, S., Serbedzija, G., Elsemore, J., Plehn-Dujowich, D., McMahon, A.P., Flavell, R.A. and Williams, T. (1996) Neural tube, skeletal and body wall defects in mice lacking transcription factor AP-2. Nature, 381, 238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pyrgaki, C., Liu, A. and Niswander, L. (2011) Grainyhead-like 2 regulates neural tube closure and adhesion molecule expression during neural fold fusion. Dev. Biol., 353, 38–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goudy, S., Angel, P., Jacobs, B., Hill, C., Mainini, V., Smith, A.L., Kousa, Y.A., Caprioli, R., Prince, L.S., Baldwin, S. et al. (2013) Cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous roles for IRF6 during development of the tongue. PLoS One, 8, e56270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roper, K. (2013) Supracellular actomyosin assemblies during development. BioArchitecture, 3, 45–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nikolopoulou, E., Hirst, C.S., Galea, G., Venturini, C., Moulding, D., Marshall, A.R., Rolo, A., De Castro, S.C.P., Copp, A.J. and Greene, N.D.E. (2019) Spinal neural tube closure depends on regulation of surface ectoderm identity and biomechanics by Grhl2. Nat. Commun., 10, 2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tunster, S.J. (2017) Genetic sex determination of mice by simplex PCR. Biol. Sex Differ., 8, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Czirok, A., Varga, K., Mehes, E. and Szabo, A. (2013) Collective cell streams in epithelial monolayers depend on cell adhesion. New J. Phys., 15, 75006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Szabo, A., Unnep, R., Mehes, E., Twal, W.O., Argraves, W.S., Cao, Y. and Czirok, A. (2010) Collective cell motion in endothelial monolayers. Phys. Biol., 7, 046007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zamir, E.A., Czirok, A., Rongish, B.J. and Little, C.D. (2005) A digital image-based method for computational tissue fate mapping during early avian morphogenesis. Annals Biomed. Eng., 33, 854–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Czirok, A., Isai, D.G., Kosa, E., Rajasingh, S., Kinsey, W., Neufeld, Z. and Rajasingh, J. (2017) Optical-flow based non-invasive analysis of cardiomyocyte contractility. Sci. Rep., 7, 10404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bolte, S. and Cordelieres, F.P. (2006) A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J. Microsc., 224, 213–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.