Abstract

Lyme disease often leaves patients with chronic symptoms of fatigue, easy confusion, and even cardiac arrhythmias. We report a case in which Lyme disease was treated with an herbal mixture due to protracted symptoms despite intravenous antibiotics. This mixture was associated with hepatotoxicity. General providers should be aware of the fact that homeopathic remedies may be associated with hepatotoxicity, and herbalists need better understanding of the safety risks of the individual components in remedy mixtures.

Keywords: Borrelia, chemical, drug, hepatotoxicity, homeopathic

Lyme disease caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi is the most common vector-borne illness in North America and Europe. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the annual incidence in the United States exceeds 300,000 cases.1 Chronic perception of poor health is common with this disorder, even after antibiotic therapy, and this often causes afflicted persons to seek alternative medications and interventions.2

CASE DESCRIPTION

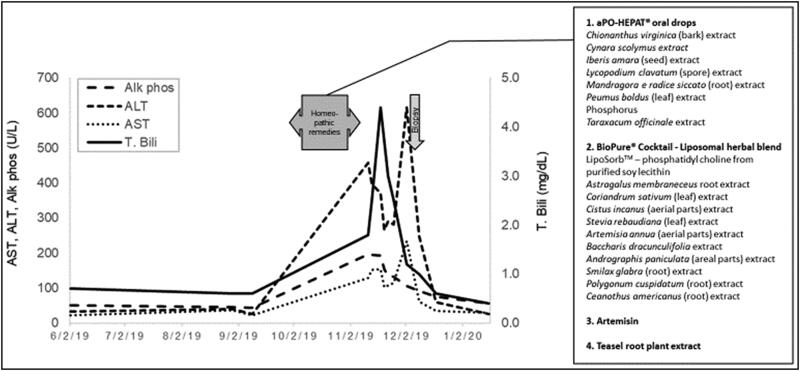

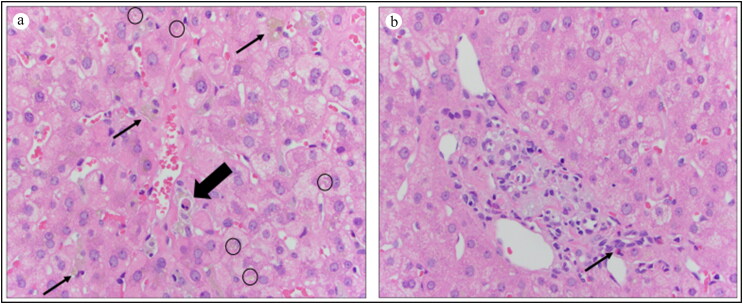

A previously healthy 45-year-old white woman contracted Lyme disease in 2015 at age 39 while residing in southwestern Germany. The characteristic skin lesion of erythema migrans was followed several weeks later by forgetfulness, symptomatic bradycardia, and fatigue. Antibiotic therapy with a 4-week course of doxycycline was delayed until 18 months later. The patient had transient symptomatic improvement after antibiotic therapy, but resumption of her chronic symptoms led to a 4-week course of intravenous cephalosporin-based therapy the following year. A Lyme specialist was consulted and four different homeopathic remedies were prescribed to be taken together (Figure 1). An increase in total serum bilirubin and serum aminotransferases was observed 4 weeks after treatment initiation (Figure 1). Mild jaundice and intractable pruritus developed despite discontinuation of treatment. Serologic testing for autoimmune hepatitis was negative. A percutaneous liver biopsy revealed features consistent with herbal hepatotoxicity (Figure 2). Rare eosinophils were seen in the biopsy but peripheral eosinophilia did not occur. The liver profile normalized 6 weeks after discontinuation of the alternative medicine and she has remained healthy ever since.

Figure 1.

The time course of biochemical events and drug exposure. Aminotransferases and bilirubin became elevated a few weeks after initiation of treatment and continued to be elevated for several weeks after discontinuation.

Figure 2.

(a) Central vein in center. Apoptotic body (large arrow) surrounded by ceroid-laden macrophages (small arrows). Several hepatocytes with bile pigment within them (circles) (hematoxylin and eosin, 400×). (b) Portal tract with several foamy, gray ceroid-laden macrophages and a single eosinophil (arrow). Features are consistent with herbal toxicity.

DISCUSSION

Elevated liver enzymes are an uncommon manifestation during the acute phase of Lyme disease and abate with antibiotic treatment.3 Unfortunately, many patients are left with chronic fatigue, easy confusion, and even cardiac arrhythmias during a prolonged convalescence. In the current case, the relation between the time of initiation of complex homeopathic treatment and abnormal liver chemistries was appropriate for herbal-induced hepatoxicity. This was further confirmed by the finding of ceroid-laden macrophages and apoptotic bodies (vesicles containing necrotic cellular debris) and the absence of features of chronic liver disease. The most likely implicated agent in the current case is artemisinin, an herbal compound that has been used in the treatment of malaria and has been previously reported to be hepatotoxic (livertox.nih.gov, accessed 2-17-2020), including cases with jaundice. The mechanism of injury has not been defined but the short latency period in previous cases as well as the current case suggests a hypersensitivity mechanism.

Lyme disease is often curable when doxycycline is given early. However, 10% to 20% of patients with Lyme disease continue to experience persistent fatigue, musculoskeletal symptoms, and cognitive symptoms after standard antibiotic treatment for 6 months or longer.4 Afflicted patients have easy access to internet-based testimonials from patients, particularly online blogs and discussion boards, as well as promotional materials by alternative therapy providers.2 As might be expected, a recent review of alternative treatments for Lyme disease found that none were associated with scientific studies that supported therapeutic benefit.2

A vaccine against Lyme disease was recently withdrawn from the market, and a high background rate of infection will likely persist. The use of serologic screening for Lyme disease in patients with a low probability of having the infection has been reported to result in a large number of false positives.5 Taken together, this could lead to a scenario in which seropositive individuals with or even without Lyme disease and persistent nonspecific symptoms of ill health have easy access to alternative treatments with unpredictable adverse events. Unfortunately, “Lyme specialists” are often advocates of nontraditional therapy and lack knowledge of the potential for adverse events. It is reasonable to conclude from the current case that hepatotoxicity from herbal treatment of Lyme disease is most likely underdiagnosed and a therapeutic misadventure that both general providers and hepatologists need to be aware of.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Lyme disease: data and statistics. https:/www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/index.html. Accessed February 15, 2020.

- 2.Mac S, Bahia S, Simbulan F, et al. Long-term sequelae and health-related quality of life associated with Lyme disease: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:440–452. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaidi SA, Singer C.. Gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of tickborne diseases in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1206–1220. doi: 10.1086/339871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lantos PM, Shapiro ED, Auwaerter PG, et al. Unorthodox alternative therapies marketed to treat Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1776–1782. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro ED, Wormser GP. Lyme disease in 2018: what is new (and what is not). JAMA. 2018;320:635–636. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]