Abstract

Objective:

Therapeutic development in progressive multiple sclerosis (PMS) has been hampered by a lack of reliable biomarkers to monitor neurodegeneration. Optical coherence tomography (OCT)-derived retinal measures have been proposed as promising biomarkers to fulfill this role. However, it is unclear if retinal atrophy persists in PMS, exceeds normal aging, or can be distinguished from relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).

Methods:

178 RRMS, 186 PMS, and 66 control participants were followed with serial OCT for a median follow-up of 3.7 years.

Results:

The estimated proportion of peri-papillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL) and macular ganglion cell+inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) thinning in MS attributable to normal aging increased from 42.7% and 16.7% respectively at age 25 years, to 83.7% and 81.1% at age 65 years. However, independent of age, PMS was associated with faster pRNFL (−0.34±0.09%/year; p<0.001) and GCIPL (−0.27±0.07%/year; p<0.001) thinning, as compared to RRMS. In both MS and controls, higher baseline age was associated with faster inner (INL) and outer nuclear layer (ONL) thinning. INL and ONL thinning were independently faster in PMS, as compared to controls (INL:−0.09±0.04%/year, p=0.03; ONL:−0.12±0.06%/year, p=0.04), and RRMS (INL:−0.10±0.04%/year, p=0.01; ONL:−0.13±0.05%/year, p=0.01), while they were similar in RRMS and controls. Unlike RRMS, disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) did not impact rates of retinal layer atrophy in PMS.

Interpretation:

PMS is associated with faster retinal atrophy independent of age. INL and ONL measures may be novel biomarkers of neurodegeneration in PMS, that appear to be unaffected by conventional DMTs. The effects of aging on rates of retinal layer atrophy should be considered in clinical trials incorporating OCT outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

In the majority of patients, multiple sclerosis (MS) is clinically characterized by an initial relapsing-remitting course (RRMS) often followed, years later, by a secondary progressive MS (SPMS) course, during which disability gradually accumulates, usually in the absence of clinical relapses and overt inflammatory radiological disease activity.1 A subset of patients exhibits a primary progressive MS (PPMS) course, wherein disability accumulates from disease onset, seemingly bypassing the relapsing-remitting stage of the disease.1 Whilst the exact pathologic mechanisms driving progressive MS (PMS) remain to be fully elucidated, it appears that the initial relapsing-remitting stage of the disease is primarily driven by adaptive immune system mediated inflammatory activity, followed thereafter by progressive neurodegeneration due to a variety of processes. These include compartmentalized inflammation, oxidative stress, axonal ionic imbalance, and mitochondrial dysfunction, which, in concert, may lead to a state of virtual hypoxia, ultimately culminating in neuro-axonal demise.2,3 Notably, therapeutic development in PMS has been hampered by a lack of reliable biomarkers to monitor neurodegeneration.4

The anterior visual pathway is a frequent site of involvement in MS and the retina is an unmyelinated structure of the central nervous system that may be rapidly, reliably and non-invasively assessed by use of optical coherence tomography (OCT), a reproducible, high-resolution imaging technique.5,6 Thus, the retina has been proposed as an opportune site to study and monitor neuro-axonal loss in MS. Studies utilizing OCT have shown that rates of composite ganglion cell + inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) thinning are faster in people with MS exhibiting evidence of clinico-radiological disease activity, mirror brain atrophy over time (especially of the gray matter), and are differentially modulated by disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) in RRMS.7–9 Furthermore, increased inner nuclear layer (INL) thickness predicts clinico-radiological disease activity, although decreased thicknesses of the INL and outer nuclear layer (ONL) have also been associated with increased MS disability.10–12 A seminal pathologic study of MS eyes found atrophy not only of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and ganglion cell layer, but also of the INL, which was more frequently found in MS eyes of subjects with longstanding and/or progressive disease.13 These data suggest that there may be differences in retinal pathology across the various stages of MS. However, these have been incompletely characterized, as the vast majority of OCT studies assessing the effects of age and disease subtype on retinal layer thickness measures in MS have been cross-sectional and included relatively small numbers of PMS participants.14–18

The primary objectives of this study were: 1) To determine if retinal layer atrophy is ongoing in PMS, and the contribution of normal aging-related changes to this atrophy, 2) To determine if PMS is associated with specific retinal layer findings helping to distinguish the disease state from RRMS and normal aging, and 3) To characterize the effects, and differences therein, of DMTs on retinal layer atrophy in PMS, as compared to RRMS.

METHODS

Study design and participants

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins University and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The study was conducted between September, 2008 and April, 2018.

Two cohorts were recruited: an MS cohort and a healthy control (HC) cohort. Participants with a diagnosis of MS confirmed by the treating neurologist, according to the 2005 revised McDonald criteria, without optic neuritis (ON) within 6 months prior to baseline assessment, were recruited by convenience sampling from the Johns Hopkins MS Center, Baltimore, MD.19 Disease subtype was classified as RRMS, SPMS or PPMS by the treating neurologist.20 MS participants underwent serial retinal imaging with OCT (every 6 to 12 months).

HC were recruited from amongst Johns Hopkins University staff and patients’ spouses, and were invited for annual OCT scans. Johns Hopkins University staff members live in a similar geographic area as our patient population and were chosen to have a similar range of ages (18–65 years) and sex ratio (roughly 70% female) as in a typical cohort of people with MS.

Individuals with ON within 6 months, refractive errors of greater than ±6 diopters, history of ocular surgery, glaucoma, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, or other significant neurological or ophthalmological disorders were excluded from the study.21 Data from participants who developed ON during the course of the study were censored at the last available OCT evaluation prior to the ON event.

Procedures

Retinal imaging was performed with spectral domain OCT (Cirrus HD-OCT, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, California), as previously described.22 Briefly, peripapillary and macular data were obtained with the Optic Disc Cube 200×200 protocol and Macular Cube 512×128 protocol, respectively. Scans with signal strength less than 7/10, or with artifact were excluded, in accordance with OSCAR-IB criteria.21,23

Peri-papillary RNFL (pRNFL) thickness values were generated by conventional Cirrus HD-OCT software, as described in detail elsewhere.22 Segmentation of the GCIPL, INL, and ONL was performed utilizing an automated segmentation algorithm, as previously described.24 Previous studies have shown that measures derived from this OCT segmentation algorithm are highly reliable, not only cross-sectionally, but also longitudinally, both in MS and HC.25 Average thicknesses of the GCIPL, INL, and ONL were calculated within an annulus, centered on the fovea, with an internal diameter of 1mm and an external diameter of 5mm. All macular cube scans and segmentations were reviewed to confirm the accuracy of the segmentation and to assess for the presence of macular pathology (including microcystoid macular pathology [MMP]; also referred to in the literature as microcystic macular edema [MME]).10,26

OCT methods and results are reported in accordance with consensus APOSTEL recommendations.27

Statistical analyses

Baseline retinal layer thicknesses were compared between groups using mixed-effects linear regression models with random subject-specific intercepts, adjusted for age, sex, race (African-American [AA] vs non-AA), and disease duration (for comparisons amongst MS subtypes). Longitudinal analyses were performed utilizing mixed-effects linear regression with random subject and eye-specific intercepts and random slopes in time, using time from baseline visit (in years) as a continuous independent variable. Importantly, given that OCT scans in this study were acquired at irregular intervals (every 6-12 months), mixed-effects models are robust to irregularly spaced measurements.28 Log-linear models were utilized to estimate annualized percent change in individual retinal layer thickness, in order to facilitate interpretation of the obtained beta coefficients across retinal layers.

We examined the effects of age on rates of change of individual retinal layer thicknesses by fitting linear models separately in MS and HC, including baseline age and its interaction with follow-up time.29 These models assume a linear relationship between the rate of retinal layer change and baseline age. In order to assess for non-linear relationships between age and rates of individual retinal layer thinning, models including additionally a quadratic baseline age term and its interaction with follow-up time were also examined. Inclusion of the quadratic age term did not improve fit of our models as determined by use of the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and thus models including linear age terms are presented.30 Since we found that pRNFL and GCIPL thinning in MS and HC exhibit different relationships with baseline age, comparisons of these measures between MS and HC were performed by calculating from these models point estimates (and their standard errors using the delta method) of pRNFL and GCIPL thinning at specific ages and comparing between groups.31 For the INL and ONL, given that the relationships observed with age were similar in MS and HC, comparisons between groups were performed with mixed effects linear regression models including a group*time interaction term and a common baseline age*time interaction term. In addition to age, the effects of other demographic and clinical characteristics, including sex, race (AA vs non-AA), disease subtype, history of ON, disease duration and baseline EDSS (quartiles) were similarly evaluated, by including in models these variables and their respective interactions with follow-up time. The effects of DMT category on rates of retinal layer change were analyzed separately in PMS and RRMS, utilizing mixed-effects linear regression, with treatment epochs (≥2 consecutive visits during which a participant remained untreated or on DMTs in the same category) nested within eyes, nested within participants. Assumptions for all models were validated by visual inspection of residuals, which did not show any significant deviations from normality or homoscedasticity.

Sample size calculations for PMS were performed based on variance parameters estimated from the mixed-effects models using the R package “longpower” according to the formula of Liu and Liang.32

Our comparisons of the retinal layer thicknesses between HC and MS subtypes (both cross-sectionally and longitudinally) were the primary focus of the study and based on a priori established research hypotheses. Other analyses (including the relationship of retinal layer atrophy with demographic factors and DMT use) are considered exploratory, and the results should be interpreted as such.33 A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 15 (College Station, TX), with the exception of the sample size calculations which were performed using R Version 3.5.3 (https://www.r-project.org/).

Role of the funding source

The sponsors of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had complete access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Study Population

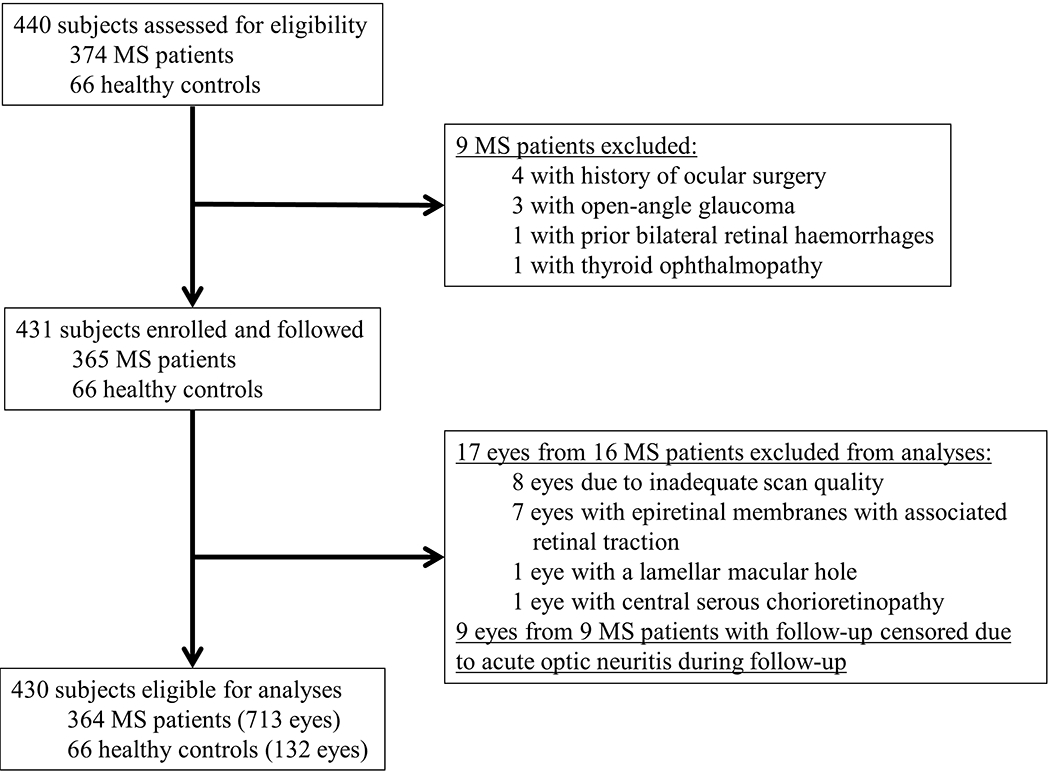

178 RRMS, 126 SPMS, 60 PPMS, and 66 HC participants, followed for a median duration of 3.7 years (IQR: 2.0 to 5.9 years), were eligible for inclusion in the analysis (Figure 1). Demographics and clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in detail in Table 1.

Figure 1 -. Study Profile.

MS: multiple sclerosis

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| HC | RRMS | PPMS | SPMS* | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects (eyes) | 66 (132) | 178 (351) | 60 (115) | 126 (247) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 35.9 (10.7) | 41.4 (9.9) | 53.3 (10.7) | 51.0 (9.6) | <0.001 a |

| Female, n (%) | 44 (66.7%) | 143 (80.3%) | 33 (55.0%) | 84 (66.7%) | 0.001 b |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| Caucasian American | 52 (78.8%) | 147 (82.6%) | 46 (76.7%) | 109 (86.5%) | 0.45c |

| African American | 9 (13.6%) | 23 (12.9%) | 10 (16.7%) | 15 (11.9%) | |

| Other | 5 (7.6%) | 8 (4.5%) | 4 (6.7%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| EDSS, median (IQR) | - | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 5.5 (3.0-6.0) | 5.5 (4.0-6.0) | <0.001 d |

| Disease duration, years, median (IQR) | - | 8.0 (4.0-12.0) | 7.5 (4.0-13.0) | 15.5 (9.0-24.0) | <0.001 e |

| On DMT at baseline, n (%) | - | 168 (94.4%) | 24 (40%) | 73 (57.9%) | <0.001 f |

| Eyes with optic neuritis history, n (%) | - | 115 (32.8%) | - | 66 (26.7%) | 0.11c |

| MMP, n (%) | - | 10 (5.6%) | 3 (5.0%) | 7 (5.6%) | 0.28c |

| Number of OCT scans per subject, median (IQR) | 4 (3-5) | 4 (3-5) | 3 (2-6) | 3 (2-5) | 0.73g |

| Follow-up time, years, median (IQR) | 3.5 (1.9-5.7) | 3.4 (2.1-5.7) | 3.6 (1.6-5.7) | 4.3 (2.3-6.6) | 0.07g |

Seven SPMS participants (5.6%) were classified as “relapsing-SPMS” by the treating physician.

One-way ANOVA; Pairwise comparisons by t-test revealed p<0.001 for all comparisons except for PPMS vs SPMS (p=0.16)

Chi-squared test; Pairwise comparisons: Controls vs RRMS (p=0.03), Controls vs PPMS (p=0.18), Controls vs SPMS (p=0.99), RRMS vs PPMS (p<0.001), RRMS vs SPMS (p=0.007), and PPMS vs SPMS (p=0.12)

Chi-squared test

Kruskal-Wallis test; Pairwise comparisons by Wilcoxon rank-sum test revealed p<0.001 for comparisons of SPMS or PPMS with RRMS and p=0.29 for comparison of PPMS and SPMS

Kruskal-Wallis test; Pairwise comparisons by Wilcoxon rank-sum test revealed p<0.001 for comparisons of PPMS or SPMS with RRMS and p=0.45 for comparison of PPMS and RRMS

Chi-squared test; Pairwise comparisons: RRMS vs SPMS (p<0.001), RRMS vs PPMS (p<0.001) and PPMS vs SPMS (p=0.02)

Kruskal-Wallis test

HC: healthy controls; RRMS: relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; SD: standard deviation, EDSS: expanded disability status scale; IQR: inter-quartile range; DMT: disease-modifying therapy; MMP: microcystoid macular pathology; OCT: optical coherence tomography

Baseline comparisons of retinal layer thicknesses

Baseline retinal layer thicknesses and comparisons between HC and MS eyes (by disease subtype) are presented in Table 2. As expected, GCIPL and pRNFL thicknesses were lower across all MS subtypes, as compared to HC, regardless of ON history. Comparisons between MS subtypes revealed lower GCIPL and pRNFL thicknesses in SPMS relative to RRMS eyes, and lower GCIPL thickness in PPMS as compared to RRMS eyes. When restricting analyses to eyes without a history of ON, GCIPL and pRNFL thicknesses were lower in both SPMS and PPMS relative to RRMS eyes. GCIPL and pRNFL thicknesses did not differ between SPMS and PPMS, irrespective of ON history.

Table 2.

Baseline retinal layer thicknesses and comparisons between groups

| HC | RRMS | PPMS | SPMS | HC vs RRMS | HC vs PPMS | HC vs SPMS | RRMS vs PPMS | RRMS vs SPMS | PPMS vs SPMS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retinal layer thicknesses, μm, mean (SD) | β (SE) | P-value | β (SE) | P-value | β (SE) | P-value | β (SE) | P-value | β (SE) | P-value | β (SE) | P-value | |||||

| pRNFL | All Eyes a | 93.9 (10.3) | 85.5 (12.9) | 84.9 (11.7) | 80.3 (12.4) | −8.2 (1.7) | <0.001 | −9.1 (2.2) | <0.001 | −13.4 (1.9) | <0.001 | −1.9 (1.9) | 0.31 | −3.5 (1.5) | 0.018 | −1.6 (1.9) | 0.39 |

| GCIPL | 77.5 (5.3) | 70.4 (9.2) | 68.6 (8.0) | 65.5 (8.8) | −7.4 (1.1) | <0.001 | −10.3 (1.5) | <0.001 | −13.2 (1.3) | <0.001 | −3.5 (1.3) | 0.008 | −4.7 (1.1) | <0.001 | −1.1 (1.3) | 0.40 | |

| INL | 45.6 (2.7) | 45.1 (2.9) | 43.8 (3.0) | 43.9 (2.8) | −0.3 (0.4) | 0.40 | −1.7 (0.6) | 0.001 | −1.7 (0.5) | <0.001 | −1.3 (0.5) | 0.006 | −1.2 (0.4) | 0.002 | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.83 | |

| ONL | 68.5 (6.0) | 67.9 (6.1) | 67.0 (5.3) | 66.6 (5.1) | −0.5 (0.8) | 0.54 | −2.6 (1.1) | 0.016 | −2.7 (0.9) | 0.004 | −1.9 (0.9) | 0.039 | −2.1 (0.7) | 0.004 | −0.3 (0.9) | 0.78 | |

| pRNFL | Non-ON Eyes b | 93.9 (10.3) | 89.0 (11.7) | 84.9 (11.7) | 82.3 (12.2) | −4.9 (1.7) | 0.004 | - | - | −11.8 (1.9) | <0.001 | −5.0 (1.9) | 0.01 | −5.1 (1.6) | 0.002 | −0.1 (1.9) | 0.94 |

| GCIPL | 77.5 (5.3) | 72.9 (7.9) | 68.6 (8.0) | 67.2 (8.5) | −4.9 (1.1) | <0.001 | - | - | −11.6 (1.3) | <0.001 | −5.5 (1.3) | <0.001 | −5.5 (1.1) | <0.001 | 0.03 (1.3) | 0.98 | |

| INL | 45.6 (2.7) | 45.2 (2.8) | 43.8 (3.0) | 43.9 (2.8) | −0.3 (0.4) | 0.42 | - | - | −1.7 (0.5) | <0.001 | −1.3 (0.5) | 0.006 | −1.2 (0.4) | 0.002 | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.88 | |

| ONL | 68.5 (6.0) | 68.3 (6.0) | 67.0 (5.3) | 66.8 (5.1) | −0.4 (0.8) | 0.67 | - | - | −2.6 (1.0) | 0.006 | −2.0 (0.9) | 0.03 | −2.2 (0.8) | 0.005 | −0.2 (0.9) | 0.83 | |

132 HC, 351 RRMS, 115 PPMS and 247 SPMS eyes

132 HC, 236 RRMS, 115 PPMS and 181 SPMS eyes

Derived from linear mixed-effects models including age, sex, race, and disease duration (for comparisons amongst MS subtypes).

Statistically significant comparisons are in bold.

HC: healthy controls; RRMS: relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error; pRNFL: peri-papillary retinal nerve fiber layer; GCIPL: ganglion cell + inner plexiform layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; ONL: outer nuclear layer

Deeper retinal layer (INL and ONL) thicknesses were also lower in SPMS and PPMS, as compared to RRMS and HC eyes, while INL and ONL thicknesses did not differ between RRMS and HC eyes. Results were similar in analyses excluding eyes with a history of ON, and INL and ONL thicknesses were not associated with ON history. Moreover, INL and ONL thicknesses were similar in PPMS and SPMS eyes, regardless of ON history.

Effects of age on longitudinal changes in retinal layer thicknesses and comparisons between MS and healthy controls

Mean unadjusted annualized percent change in retinal layer thicknesses in HC and MS subtypes are shown in Table 3. Importantly, significant thinning of all studied retinal layers occurred during follow-up in all groups, including in HC (p<0.05 for all). Given the expected difference in age between groups, we initially sought to examine the contribution of age to longitudinal rates of change in retinal layer thicknesses in MS and HC.

Table 3.

Unadjusted annualized percent change in retinal layer thicknesses in controls and in MS subtypes

| Unadjusted annualized percent change in retinal layer thickness, mean (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC (n=132 eyes) |

RRMS (n=351 eyes) |

PPMS (n=115 eyes) |

SPMS (n=247 eyes) |

|

| pRNFL | −0.37% (−0.53% to −0.20%) |

−0.59% (−0.68% to −0.49%) |

−0.69% (−0.86% to −0.53%) |

−0.69% (−0.80% to −0.59%) |

| GCIPL | −0.18% (−0.30% to −0.06%) |

−0.37% (−0.44% to −0.31%) |

−0.67% (−0.80% to −0.55%) |

−0.54% (−0.63% to −0.46%) |

| INL | −0.20% (−0.27% to −0.13%) |

−0.27% (−0.31% to −0.22%) |

−0.33% (−0.41% to −0.26%) |

−0.38% (−0.42% to −0.33%) |

| ONL | −0.11% (−0.21% to −0.02%) |

−0.17% (−0.23% to −0.12%) |

−0.27% (−0.37% to −0.17%) |

−0.30% (−0.36% to −0.24%) |

HC: healthy controls; RRMS: relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; CI: confidence intervals; pRNFL: peri-papillary retinal nerve fiber layer; GCIPL: ganglion cell + inner plexiform layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; ONL: outer nuclear layer

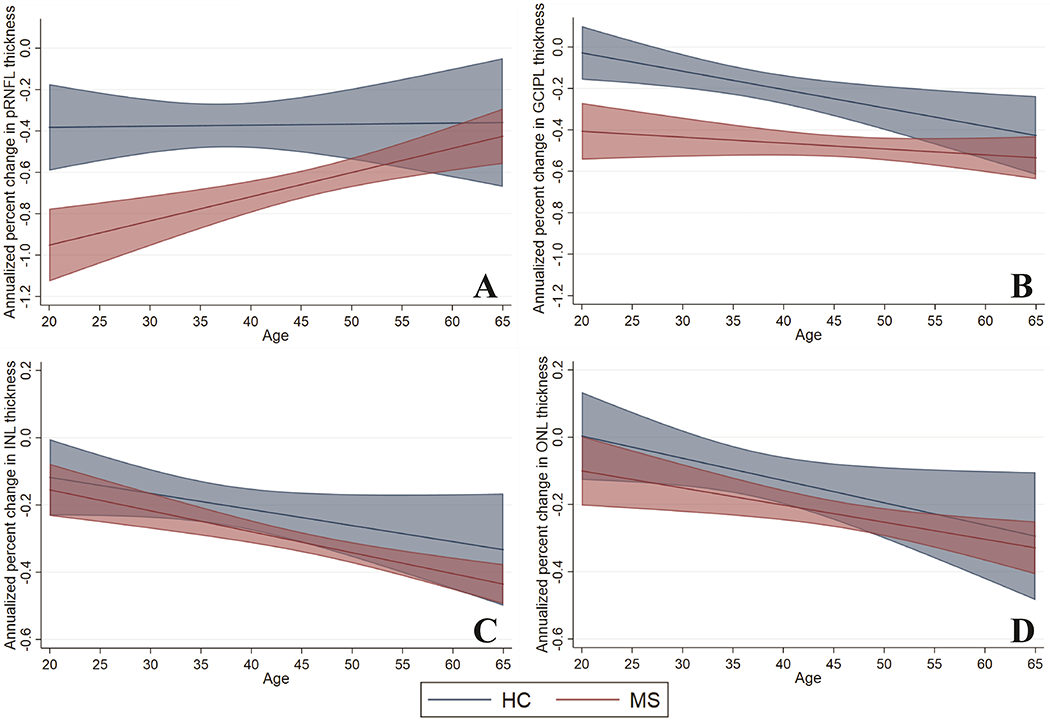

We evaluated the effect of age at enrollment on rates of retinal layer change during follow-up, by fitting models for the MS and HC cohorts, including an interaction term of baseline age*time. Figure 2, Table 4 and Supplementary Table 1 summarize these results. Higher age at baseline was associated with slower rates of pRNFL thinning (Figure 2A) in MS (βage*time: 0.12% absolute change in the annualized percent change per 10-year increase in age; 95% CI: 0.06% to 0.18%; p<0.001), but not in HC eyes (βage*time: 0.005% absolute change in the annualized percent change per 10-year increase in age; 95% CI: −0.10% to 0.11%; p=0.92). On the other hand, rates of GCIPL thinning (Figure 2B) were constant across age in MS (βage*time: −0.03% absolute change in annualized percent change per 10-year increase in age; 95% CI: −0.08% to 0.02%; p=0.25), although HC exhibited faster rates of GCIPL thinning with increasing age (βage*time: −0.09% absolute change in annualized percent change per 10-year increase in age; 95% CI: −0.15% to −0.02%; p=0.006). These results show that with increasing age, the rates of pRNFL and GCIPL atrophy in MS approaches rates similar to those expected with normal aging (Figure 2A and 2B).

Figure 2 -. Relationship of rates of retinal layer thinning and baseline age in multiple sclerosis and healthy controls.

Graphs demonstrating estimates (solid lines) of annualized percent change in retinal layer thicknesses and 95% confidence intervals (shaded intervals) by age at baseline, separately for multiple sclerosis (red) and healthy controls (blue), derived from mixed-effects linear regression models including baseline age, follow-up time and their interaction. The slope of the solid lines corresponds to the beta coefficients obtained for the age*time interaction term. Higher age at baseline was associated with slower rates of pRNFL thinning in MS participants, but not in controls (p<0.001 and p=0.92 respectively; Panel A). Rates of GCIPL thinning were constant across age in MS participants, however controls exhibited faster rates of GCIPL thinning with increasing age (p=0.25 and p=0.006 respectively; Panel B). Higher age at baseline was also associated with faster rates of INL (Panel C) and ONL (Panel D) thinning in MS (INL: p<0.001; ONL: p=0.006) and healthy controls (INL: p=0.09; ONL p=0.04), although the relationship for INL thinning did not attain statistical significance in the healthy controls.

Table 4.

Annualized percent change in pRNFL and GCIPL in healthy controls and MS by age at baseline

| Annualized Percent Change in pRNFL Thickness β (95% CI) | P-value* | Proportion of pRNFL thinning attributable to normal aging | Annualized Percent Change in GCIPL Thickness β (95% CI) | P-value* | Proportion of GCIPL thinning attributable to normal aging | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline (years) | HC | MS | HC | MS | ||||

| 25 | −0.38% (−0.55% to −0.21%) |

−0.89% (−1.04% to −0.75%) |

<0.001 | 42.7% | −0.07% (−0.18% to 0.03%) |

−0.42% (−0.54% to −0.31%) |

<0.001 | 16.7% |

| 35 | −0.38% (−0.48% to −0.27%) |

−0.78% (−0.87% to −0.68%) |

<0.001 | 48.7% | −0.16% (−0.23% to −0.09%) |

−0.45% (−0.52% to −0.37%) |

<0.001 | 35.6% |

| 45 | −0.37% (−0.50% to −0.24%) |

−0.66% (−0.73% to −0.59%) |

<0.001 | 56.1% | −0.25% (−0.33% to −0.17%) |

−0.48% (−0.53% to −0.43%) |

<0.001 | 52.1% |

| 55 | −0.36% (−0.58% to −0.15%) |

−0.54% (−0.63% to −0.46%) |

0.13 | 66.7% | −0.34% (−0.47% to −0.21%) |

−0.51% (−0.57% to −0.44%) |

0.03 | 66.7% |

| 65 | −0.36% (−0.67% to −0.05%) |

−0.43% (−0.56% to −0.29%) |

0.70 | 83.7% | −0.43% (−0.62% to −0.24%) |

−0.53% (−0.64% to −0.43%) |

0.33 | 81.1% |

P-value for comparison of point estimates of rates of change in retinal layer thicknesses between controls and MS participants at given age

HC: healthy controls; MS: multiple sclerosis; CI: confidence intervals; pRNFL: peri-papillary retinal nerve fiber layer; GCIPL: ganglion cell + inner plexiform layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; ONL: outer nuclear layer

Given the differing relationship of baseline age with pRNFL and GCIPL thinning in HC and MS eyes, in order to compare rates of thinning between groups, we utilized these models to calculate age-specific point estimates of annualized rates of thinning from age 25 to 65 (corresponding to the range of ages for the vast majority of study participants). Comparisons of these point estimates between HC and MS revealed significantly faster rates of pRNFL and GCIPL atrophy in the MS cohort up to ages 53 and 57 years respectively. Table 4 presents these point estimates from age 25 to 65 years in 10-year increments. We estimate that the percentage of pRNFL and GCIPL thinning in MS attributable to normal aging increased from 42.7% and 16.7% respectively at age 25 years, to 83.7% and 81.1% respectively at age 65 years.

Increasing age at baseline was also associated with faster rates of INL and ONL thinning in MS (absolute change in annualized percent change per 10-year increase in age: INL – βage*time: −0.06%, 95% CI: −0.09% to −0.03%, p<0.001; ONL – βage*time: −0.05%, 95% CI: −0.09% to −0.01%, p=0.006) and HC (absolute change in annualized percent change per 10-year increase in age: INL – βage*time: −0.05%, 95% CI: −0.10% to 0.01%, p=0.09; ONL – βage*time: −0.07%, 95% CI: −0.13% to −0.002%, p=0.04), with age-related increases of similar magnitude (Figure 2C and 2D), although the relationship for INL atrophy did not attain statistical significance in the HC group, likely due to sample size. In analyses accounting for age, rates of INL and ONL atrophy did not differ between the HC and whole MS cohort (INL: p=0.11; ONL p=0.20). However, consistent with the demonstration of reduced INL and ONL thicknesses at baseline in PMS, in age-adjusted comparisons by MS subtype, relative to HC, SPMS subjects had faster rates of INL (βSPMS*time: −0.11% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.20% to −0.02%; p=0.02) and ONL atrophy (βSPMS*time: −0.13% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.25% to −0.01%; p=0.03). Age-adjusted differences in INL and ONL thinning between PPMS and HC were in a similar direction, but not significant, possibly due to smaller sample size (INL – βPPMS*time: −0.07% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.17% to 0.03%; p=0.24; ONL – βPPMS*time: −0.09% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.23% to 0.05%; p=0.20).

The similarity of baseline INL and ONL thicknesses and of the longitudinal rates of change in INL and ONL thicknesses in SPMS and PPMS, provided sufficient support that these groups could be reasonably and feasibly combined in analyses. Age-adjusted analyses revealed faster rates of INL and ONL thinning in PMS (SPMS and PPMS) vs. HC (INL – βPMS*time: −0.09% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.18% to −0.01%; p=0.03; ONL – βPMS*time: −0.12% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.23% to −0.01%; p=0.04), but not between RRMS and HC (INL – βRRMS*time: −0.04% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.13% to 0.04%; p=0.30; ONL – βRRMS*time: −0.04% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.15% to 0.07%; p=0.49). Notably, at the centered age (45 years), these differences correspond to 38% faster INL and 80% faster ONL thinning in PMS compared to HC.

Effects of sex, race, clinical characteristics and disease-modifying therapies on longitudinal changes in retinal layer thicknesses in MS

Within MS subjects, we fitted multivariate models including, in addition to age, sex, race, disease subtype, disease duration, history of ON, baseline EDSS and their respective interactions with follow-up time. In these models, the longitudinal rates of retinal layer atrophy did not differ between PPMS and SPMS subtypes (pRNFL: p=0.47; GCIPL: p=0.37; INL: p=0.92; ONL: p=0.69) and, similar to previously, these groups were therefore combined in further analyses. PMS was independently associated with faster pRNFL (βPMS*time: −0.34% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.52% to −0.16%; p<0.001), GCIPL (βPMS*time: −0.27% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.41% to −0.12%; p<0.001), INL (βPMS*time: −0.10% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.18% to −0.02% p=0.01) and ONL (βPMS*time: −0.13% annualized percent rate of change; 95% CI: −0.24% to −0.03%; p=0.01) atrophy, as compared to RRMS. The estimated effects of all the covariates on the rates of longitudinal change in retinal layer thicknesses in MS are shown in Table 5. The relationships of age with rates of retinal layer atrophy remained similar to those presented previously, with the exception of the ONL, for which the relationship did not remain significant. Higher disease duration was associated with slower rates of pRNFL atrophy, and faster rates of INL and ONL atrophy. African-American race was associated with faster GCIPL. The highest quartiles of EDSS were associated with slower rates of INL and ONL atrophy. Sex and baseline history of ON were not associated with longitudinal rates of atrophy of any of the examined retinal layers.

Table 5.

Effects of co-variates on longitudinal rates of retinal layer atrophy in MS.

| pRNFL | GCIPL | INL | ONL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) |

P-value | β (95% CI) |

P-value | β (95% CI) |

P-value | β (95% CI) |

P-value | |

| Follow-up Time (per year) |

−0.59%

(−0.75% to −0.43%) |

<0.001 |

−0.43%

(−0.54% to −0.31%) |

<0.001 |

−0.31%

(−0.38% to −0.24%) |

<0.001 |

−0.25%

(−0.34% to −0.16%) |

<0.001 |

| Age (per 10 year increase) 1,2 |

0.12%

(0.05% to 0.20%) |

0.002 | −0.01% (−0.07% to 0.05%) |

0.66 |

−0.04%

(−0.07 to −0.002%) |

0.04 | −0.02% (−0.06% to 0.03%) |

0.49 |

| Male Sex 1 | 0.13% (−0.01% to 0.28%) |

0.08 | −0.03% (−0.15% to 0.08%) |

0.57 | −0.03% (−0.10% to 0.03%) |

0.36 | −0.010% (−0.09% to 0.08%) |

0.88 |

| African-American Race 1 | 0.01% (−0.20% to 0.23%) |

0.89 |

−0.23%

(−0.40% to −0.07%) |

0.007 | 0.05% (−0.04% to 0.15%) |

0.29 | −0.11% (−0.24% to 0.01%) |

0.07 |

| Disease Duration (per 10 year increase) 1,3 |

0.10%

(0.01% to 0.20%) |

0.03 | 0.01% (−0.07% to 0.08%) |

0.83 |

−0.06%

(−0.10% to −0.002%) |

0.003 |

−0.11%

(−0.16% to −0.05%) |

<0.001 |

| Progressive MS 1 |

−0.34%

(−0.52% to −0.16%) |

<0.001 |

−0.27%

(−0.41% to −0.12%) |

<0.001 |

−0.10%

(−0.18% to −0.02%) |

0.01 |

−0.13%

(−0.24% to −0.03%) |

0.01 |

| EDSS 1 | ||||||||

| ≤1.5 (Reference) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2.0 to 3.0 | 0.03% (−0.16% to 0.22%) |

0.75 | 0.09% (−0.05% to 0.24%) |

0.20 | 0.07% (−0.02% to 0.15%) |

0.11 | 0.09% (−0.02% to 0.20%) |

0.11 |

| 3.5 to 5.5 | 0.05% (−0.20% to 0.29%) |

0.71 | 0.12% (−0.06% to 0.30%) |

0.20 | 0.10% (−0.001% to 0.21%) |

0.052 |

0.22%

(0.08% to 0.36%) |

0.002 |

| ≥6.0 | 0.16% (−0.10% to 0.42%) |

0.24 | 0.19% (−0.02% to 0.39%) |

0.07 |

0.14%

(0.03% to 0.26%) |

0.01 |

0.16%

(0.01% to 0.31%) |

0.036 |

| History of ON 1 | −0.04% (−0.20% to 0.11%) |

0.59 | 0.08% (−0.04% to 0.20%) |

0.19 | −0.03% (−0.10% to 0.03%) |

0.32 | 0.07% (−0.02% to 0.16%) |

0.13 |

Beta coefficient for interaction with time

Centered at age 45 years

Centered at disease duration 9 years

All estimates are derived from mixed-effects linear regression models including age, race, sex, disease duration, EDSS (quartile), history of ON and their respective interactions with time.

pRNFL: peri-papillary retinal nerve fiber layer; GCIPL: ganglion cell + inner plexiform layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; ONL: outer nuclear layer; CI: confidence intervals; MS: multiple sclerosis; ON: optic neuritis

Finally, we evaluated the effects of DMTs on rates of retinal layer atrophy in PMS and RRMS. DMT use was categorized as “untreated”, “lower” (DMT-L: interferon-beta and glatiramer acetate) or “higher” (DMT-H: natalizumab, rituximab, daclizumab) efficacy, based on the traditional effects of these DMTs on clinico-radiological inflammatory disease activity (i.e. relapses and new lesions). Oral DMTs were excluded from this categorization given insufficient sample size and follow-up time. Furthermore, there was an insufficient number of untreated RRMS participants to be analyzed. Follow-up treatment epochs were defined as follow-up periods of ≥2 consecutive visits during which a participant remained untreated or on DMTs in the same category. In total, 319 patient-treatment epochs (632 eye-treatment epochs) from 310 individual subjects (599 eyes) were identified that fulfilled criteria (Supplementary Table 2). In analyses accounting for age, sex, race, disease duration, EDSS and history of ON, no differences in rates of retinal layer thickness change were observed between PMS patients on DMT-H, DMT-L, or no DMT treatment, whereas in RRMS, relative to DMT-L treatment, DMT-H treatment was associated with slower thinning of the GCIPL, INL and ONL (Table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of annualized percent change in retinal layer thickness by category of disease-modifying therapy in progressive and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis disease subtypes.

| Progressive MS | Relapsing-Remitting MS | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated (n=79 epochs) | DMT-L (n=39 epochs) | DMT-H (n=36 epochs) | Untreated vs DMT-L | Untreated vs DMT-H | DMT-L vs DMT-H | DMT-L (n=119 epochs) | DMT-H (n=46 epochs) | DMT-L vs DMT-H | |||||

| Unadjusted Annualized Percent Change, β (SE) | β (SE)* | P-value* | β (SE)* | P-value* | β (SE)* | P-value* | Unadjusted Annualized Percent Change, β (SE) | β (SE)* | P-value* | ||||

| pRNFL | −0.57% (0.09%) |

−0.42% (0.11%) |

−0.79% (0.16%) |

−0.15% (0.14%) |

0.27 | −0.03% (0.18%) |

0.87 | 0.13% (0.18%) |

0.49 | −0.64% (0.06%) |

−0.54% (0.10%) |

−0.07% (0.13%) |

0.61 |

| GCIPL | −0.58% (0.07%) |

−0.59% (0.09%) |

−0.48% (0.10%) |

−0.01% (0.11%) |

0.91 | −0.12% (0.13%) |

0.37 | 0.10% (0.14%) |

0.45 | −0.47% (0.04%) |

−0.20% (0.06%) |

−0.29%

(0.08%) |

<0.001 |

| INL | −0.37% (0.04%) |

−0.38% (0.04%) |

−0.44% (0.06%) |

−0.03% (0.05%) |

0.58 | 0.05% (0.07%) |

0.48 | 0.08% (0.07%) |

0.25 | −0.30% (0.03%) |

−0.14% (0.05%) |

−0.15%

(0.06%) |

0.007 |

| ONL | −0.24% (0.05%) |

−0.28% (0.06%) |

−0.45% (0.08%) |

0.09% (0.08%) |

0.29 | 0.18% (0.10%) |

0.07 | 0.10% (0.10%) |

0.36 | −0.25% (0.03%) |

0.06% (0.05%) |

−0.31%

(0.06%) |

<0.001 |

Derived from mixed-effects linear regression models including DMT category, age, race, sex, disease duration, EDSS (quartile), history of ON and their respective interactions with time.

Statistically significant comparisons are in bold.

MS: multiple sclerosis; CI: confidence intervals; DMT: disease-modifying therapy; DMT-L: lower efficacy DMT (interferon-beta, glatiramer acetate); DMT-H: higher efficacy DMT (natalizumab, rituximab, daclizumab); pRNFL: peri-papillary retinal nerve fiber layer; GCIPL: ganglion cell + inner plexiform layer; INL: inner nuclear layer; ONL: outer nuclear layer

We also performed sample size calculations for trials of putative neuroprotective agents in PMS employing retinal layer thicknesses as outcomes, assuming a 3-year follow-up with OCT performed at 6-month intervals, randomization 1:1, alpha 0.05, power 80%, and an effect size of 50%. Sample size estimates per trial arm were lowest for the GCIPL (n=125) and INL (n=123), relative to those for the pRNFL (n=173) and ONL (n=300).

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that PMS is independently associated with faster retinal atrophy, which, in contrast to RRMS, does not appear to be reduced by conventional low or high potency anti-inflammatory DMTs. Moreover, we importantly demonstrate evidence of faster INL and ONL atrophy in PMS relative to RRMS and HC, independently of age, suggesting that measures of these layers may represent novel biomarkers for tracking neurodegeneration, particularly in progressive disease.

While INL and ONL abnormalities have been suggested to occur in MS on the basis of pathological, electrophysiological, and OCT studies, the changes occurring within these layers appear to be non-uniform throughout the disease course.10–13,26,34,35 Post-mortem, prominent atrophy of the INL was observed in 40% of MS eyes and was most pronounced in people with longstanding and/or progressive disease.13 Studies employing OCT have demonstrated a spectrum of abnormalities of the INL and ONL in MS, including: 1) INL and ONL thinning with relative sparing of the pRNFL in a subset of MS patients with a more severe disease course, 2) presence of microcystoid macular pathology (predominantly within the INL) in subsets of MS eyes, a retinal phenotype associated with more severe ambulatory and visual disability, 3) increased INL thickness which is associated with subsequent clinico-radiological disease activity, 4) reduction in INL volume after treatment initiation in RRMS that is associated with favorable therapeutic response, and 5) transient increases in INL and ONL thicknesses following ON.10,11,26,34,35 Our study significantly expands upon this literature, helping to reconcile the contradictory concepts of swelling, such as in the INL, during the more inflammatory phases of MS, and the ultimately deeper retinal atrophy found post-mortem. Our demonstration that INL and ONL thicknesses are lower cross-sectionally, and exhibit faster thinning longitudinally in PMS, raises the possibility that a progressive neuronopathy may ensue as the MS disease course progresses into a more neurodegenerative and less inflammatory phase, and that this may be tracked in-vivo by OCT. This is further supported by the lack of effect of DMTs (including high potency therapies primarily targeting the adaptive immune system) on atrophy within these layers in PMS, although interestingly we did observe slower thinning of the INL and ONL in RRMS patients treated with natalizumab, as previously demonstrated in a smaller cohort.9 Notably, natalizumab is linked to greater brain atrophy in the first year of treatment, but less in subsequent years, a phenomenon that has been attributed to “pseudoatrophy” due to resolution of inflammation and edema.36,37 It is unclear if this phenomenon may occur in the retina, and adequately powered, prospective studies evaluating the dynamics of retinal layer atrophy following treatment initiation are necessary to further evaluate this.

Furthermore, we found that age impacts longitudinal rates of retinal layer thinning in MS and HC. Notably, studies evaluating the effects of normal aging on OCT-derived retinal layer thicknesses have been nearly exclusively cross-sectional and have mainly focused on the pRNFL and GCIPL.38–40 The vast majority of these studies demonstrate an overall decrease in retinal layer thicknesses with increasing age. Our study confirms that thinning of the examined retinal layers occurs longitudinally in normal aging, but also shows that rates of thinning may be faster with increasing age, although the pRNFL appears to possibly exhibit different dynamics with aging compared to the other examined retinal layers. These findings are consistent with observations that brain atrophy rates are faster with increasing age in normal aging.41–44 Overall, our findings show that the majority of pRNFL and GCIPL atrophy occurring in older MS patients is attributable to normal aging rather than the underlying disease process, and that INL and ONL atrophy rates are faster with increasing age in both MS and normal aging. These observations have important implications for the design of clinical trials of putative neuroprotective agents in MS including OCT measures as outcomes, as well as for the use of OCT in clinical practice to monitor retinal neuro-axonal loss.

Our study has several limitations that warrant discussion. Our HC cohort, although reasonably sized and followed over an extended period of time, was nonetheless smaller than the MS cohort, and larger longitudinal cohorts will be necessary to validate our findings and clarify cut-offs defining pathologic rates of retinal layer atrophy. Additionally, lifestyle factors including tobacco use and alcohol consumption were not systematically examined in this cohort, and these factors have been proposed to be associated with retinal atrophy, similar to their effects on brain atrophy.45 As expected, PMS patients were older, with greater disability at baseline than RRMS subjects. This led us to thoroughly evaluate the impact of demographic and clinical characteristics on longitudinal changes in retinal layer thicknesses and take these into account in our statistical analyses, with our results showing that PMS is independently associated with faster retinal layer atrophy. However, it is unclear if this effect is mediated by different pathobiologic mechanisms at play in PMS, or if subjects presenting with or transitioning to PMS exhibit faster retinal neuro-axonal loss due to increased susceptibility to neurodegeneration. The ideal way to evaluate effects of disease stage would be to assess retinal atrophy prior to, during transition, and following confirmation of PMS in the same subjects. However, this would be clearly difficult to study given the sample size and lengthy follow-up required to detect sufficient transition events, and the limited ability to identify a specific transition point to PMS, since this is usually a gradual process that is often clinically recognized retrospectively.46 Furthermore, the categorization of MS into disease subtypes has inherent limitations, given that the pathologic processes at play in PMS seem to be initiated early in the disease course, with relapsing and progressive disease appearing to exist on a continuum. However, in the absence of objective imaging or biologic markers to characterize the underlying disease processes in a given MS patient, this paradigm of clinical phenotyping is helpful to isolate (to some extent) different pathologic processes and treatment effects at different stages of the MS disease process. Finally, our analyses of the effects of DMTs should be interpreted with caution, given the observational nature of this study, and replication of these finding will be important by leveraging OCT data from randomized controlled clinical trials. Notably, given our sample size we did not assess the effects of individual DMTs on retinal atrophy in PMS, and DMTs were categorized according to their effects on inflammatory disease activity. The high-potency group mainly included participants treated with natalizumab, which failed to meet its primary endpoint in the ASCEND trial in SPMS, however successful trials in PMS appear to have been largely driven by anti-inflammatory effects in younger patients with evidence of inflammatory disease activity rather than distinct neuroprotective effects, supporting the rationale for categorizing DMTs according to efficacy at suppressing clinico-radiological disease activity.47–51

In conclusion, our study provides evidence that age impacts rates of retinal layer thinning in HC and MS, and that PMS is associated with faster retinal atrophy, independently of the effects of aging. Furthermore, INL and ONL atrophy appear to predominate in the progressive phases of MS, and seem to be unaffected by anti-inflammatory DMTs, including high potency therapies, and may accordingly represent novel biomarkers of neurodegeneration in PMS. While an important next step is to independently validate our findings, this does not mitigate the relevance of the current study findings, which shed light not only on the pathobiology of the various stages of MS, but also provides insight into the design of trials employing OCT measures as study endpoints, as well as the interpretation of OCT measures in clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDEGMENTS

This study was funded by the NIH/NINDS (R01NS082347 to P.A.C.), National MS Society (FP-1607-24999 to E.S.S.; RG-1606-08768 to S.S., TR 3760-A-3 to P.A.C., RG 4212-A-4 to L.J.B. subcontracted to P.A.C.), Race to Erase MS (to S.S.), Walters Foundation (to P.A.C.) and ACTRIMS (to IMSVISUAL).

Footnotes

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2018;378(2):169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahad DH, Trapp BD, Lassmann H. Pathological mechanisms in progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2015;14(2):183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trapp BD, Stys PK. Virtual hypoxia and chronic necrosis of demyelinated axons in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2009;8(3):280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ontaneda D, Fox RJ, Chataway J. Clinical trials in progressive multiple sclerosis: Lessons learned and future perspectives. Lancet Neurol 2015;14(2):208–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sotirchos ES, Saidha S. OCT is an alternative to MRI for monitoring MS - YES. Mult Scler 2018;24(6):701–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oertel FC, Zimmermann HG, Brandt AU, Paul F. Novel uses of retinal imaging with optical coherence tomography in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother 2018:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ratchford JN, Saidha S, Sotirchos ES et al. Active MS is associated with accelerated retinal ganglion cell/inner plexiform layer thinning. Neurology 2013;80(1):47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saidha S, Al-Louzi O, Ratchford JN et al. Optical coherence tomography reflects brain atrophy in multiple sclerosis: A four-year study. Ann Neurol 2015;78(5):801–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Button J, Al-Louzi O, Lang A et al. Disease-modifying therapies modulate retinal atrophy in multiple sclerosis: A retrospective study. Neurology 2017;88(6):525–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saidha S, Sotirchos ES, Ibrahim MA et al. Microcystic macular oedema, thickness of the inner nuclear layer of the retina, and disease characteristics in multiple sclerosis: A retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 2012;11(11):963–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knier B, Schmidt P, Aly L et al. Retinal inner nuclear layer volume reflects response to immunotherapy in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2016;139(11):2855–2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saidha S, Syc SB, Ibrahim MA et al. Primary retinal pathology in multiple sclerosis as detected by optical coherence tomography. Brain 2011;134:518–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green AJ, McQuaid S, Hauser SL et al. Ocular pathology in multiple sclerosis: Retinal atrophy and inflammation irrespective of disease duration. Brain 2010;133; 2010/04/23:1591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pulicken M, Gordon-Lipkin E, Balcer LJ et al. Optical coherence tomography and disease subtype in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2007;69(22):2085–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelfand JM, Goodin DS, Boscardin WJ et al. Retinal axonal loss begins early in the course of multiple sclerosis and is similar between progressive phenotypes. PLOS ONE 2012;7(5):e36847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albrecht P, Ringelstein M, Müller AK et al. Degeneration of retinal layers in multiple sclerosis subtypes quantified by optical coherence tomography. Mult Scler 2012;18(10):1422–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberwahrenbrock T, Schippling S, Ringelstein M et al. Retinal damage in multiple sclerosis disease subtypes measured by high-resolution optical coherence tomography. Mult Scler Int 2012;2012; 2012/08/14:530305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balk LJ, Cruz-Herranz A, Albrecht P et al. Timing of retinal neuronal and axonal loss in MS: A longitudinal OCT study. J Neurol 2016;263(7):1323–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald criteria”. Ann Neurol 2005;58(6):840–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lublin FD, Reingold SC. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: Results of an international survey. national multiple sclerosis society (USA) advisory committee on clinical trials of new agents in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1996;46(4):907–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tewarie P, Balk L, Costello F et al. The OSCAR-IB consensus criteria for retinal OCT quality assessment. PLOS ONE 2012;7(4):e34823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Syc SB, Warner CV, Hiremath GS et al. Reproducibility of high-resolution optical coherence tomography in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2010;16(7):829–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schippling S, Balk LJ, Costello F et al. Quality control for retinal OCT in multiple sclerosis: Validation of the OSCAR-IB criteria. Mult Scler 2015;21(2):163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lang A, Carass A, Hauser M et al. Retinal layer segmentation of macular OCT images using boundary classification. Biomed Opt Express 2013;4(7):1133–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhargava P, Lang A, Al-Louzi O et al. Applying an open-source segmentation algorithm to different OCT devices in multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls: Implications for clinical trials. Mult Scler Int 2015;2015:136295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gelfand JM, Nolan R, Schwartz DM et al. Microcystic macular oedema in multiple sclerosis is associated with disease severity. Brain 2012;135:1786–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cruz-Herranz A, Balk LJ, Oberwahrenbrock T et al. The APOSTEL recommendations for reporting quantitative optical coherence tomography studies. Neurology 2016;86(24):2303–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibbons RD, Hedeker D, DuToit S. Advances in analysis of longitudinal data. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2010;6:79–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrell CH, Brant LJ, Ferrucci L. Model choice can obscure results in longitudinal studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64A(2):215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarz G Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics 1978;6(2):461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clogg CC, Petkova E, Haritou A. Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. American Journal of Sociology 1995;100(5):1261–1293. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu G, Liang KY. Sample size calculations for studies with correlated observations. Biometrics 1997;53(3):937–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing--when and how? J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54(4):343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Louzi OA, Bhargava P, Newsome SD et al. Outer retinal changes following acute optic neuritis. Mult Scler 2016;22(3):362–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petzold A, Balcer LJ, Calabresi PA et al. Retinal layer segmentation in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2017;16(10):797–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller DH, Soon D, Fernando KT et al. MRI outcomes in a placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab in relapsing MS. Neurology 2007;68(17):1390–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Stefano N, Airas L, Grigoriadis N et al. Clinical relevance of brain volume measures in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2014;28(2):147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leung CKS, Yu M, Weinreb RN et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer imaging with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: A prospective analysis of age-related loss. Ophthalmology 2012;119(4):731–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang X, Francis BA, Dastiridou A et al. Longitudinal and cross-sectional analyses of age effects on retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell complex thickness by fourier-domain OCT. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2016;5(2):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nieves-Moreno M, Martínez-de-la-Casa JM, Morales-Fernández L et al. Impacts of age and sex on retinal layer thicknesses measured by spectral domain optical coherence tomography with spectralis. PLOS ONE 2018;13(3):e0194169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Enzinger C, Fazekas F, Matthews PM et al. Risk factors for progression of brain atrophy in aging: Six-year follow-up of normal subjects. Neurology 2005;64(10):1704–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Fennema-Notestine C et al. One-year brain atrophy evident in healthy aging. J Neurosci 2009;29(48):15223–15231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Battaglini M, Gentile G, Luchetti L et al. Lifespan normative data on rates of brain volume changes. Neurobiol Aging 2019;81:30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azevedo CJ, Cen SY, Jaberzadeh A et al. Contribution of normal aging to brain atrophy in MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2019;6(6):e616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahuja S, Kumar PS, Kumar VP et al. Effect of chronic alcohol and tobacco use on retinal nerve fibre layer thickness: A case–control study. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 2016;1(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: The 2013 revisions. Neurology 2014;83(3):278–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hawker K, O’Connor P, Freedman MS et al. Rituximab in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: Results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Ann Neurol 2009;66(4):460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montalban X, Hauser SL, Kappos L et al. Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017;376(3):209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kapoor R, Ho P, Campbell N et al. Effect of natalizumab on disease progression in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (ASCEND): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with an open-label extension. Lancet Neurol 2018;17(5):405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kappos L, Bar-Or A, Cree BAC et al. Siponimod versus placebo in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (EXPAND): A double-blind, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet 2018;391(10127):1263–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Metz LM, Liu W. Effective treatment of progressive MS remains elusive. The Lancet 2018;391(10127):1239–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.