Abstract

Objective:

To reassess the inclination of lower incisors and evaluate possible associations with gender, age, symphyseal parameters, and skeletal pattern.

Materials and Methods:

Twelve hundred and seventy-two (605 females, 667 males) cephalograms of untreated subjects of a craniofacial growth study (age: 8–16 years) were evaluated. Correlations between the angulation of the lower incisors and age, symphyseal distances (height, width, and depth), symphyseal ratios (height-width, height-depth), and skeletal angles (divergence of the jaws and gonial angle) were investigated for all ages separately and for both sexes independently.

Results:

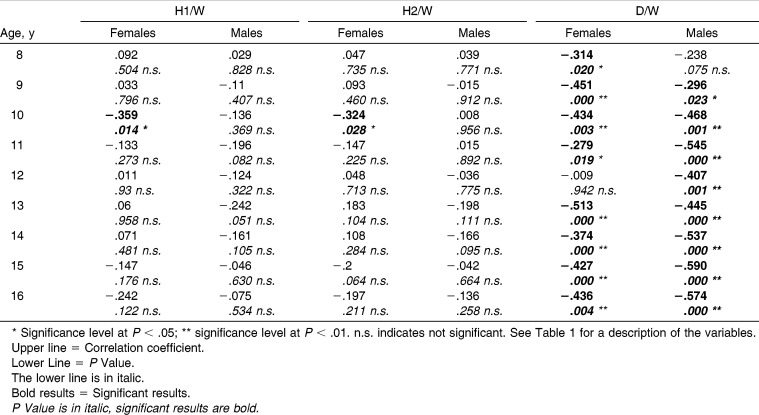

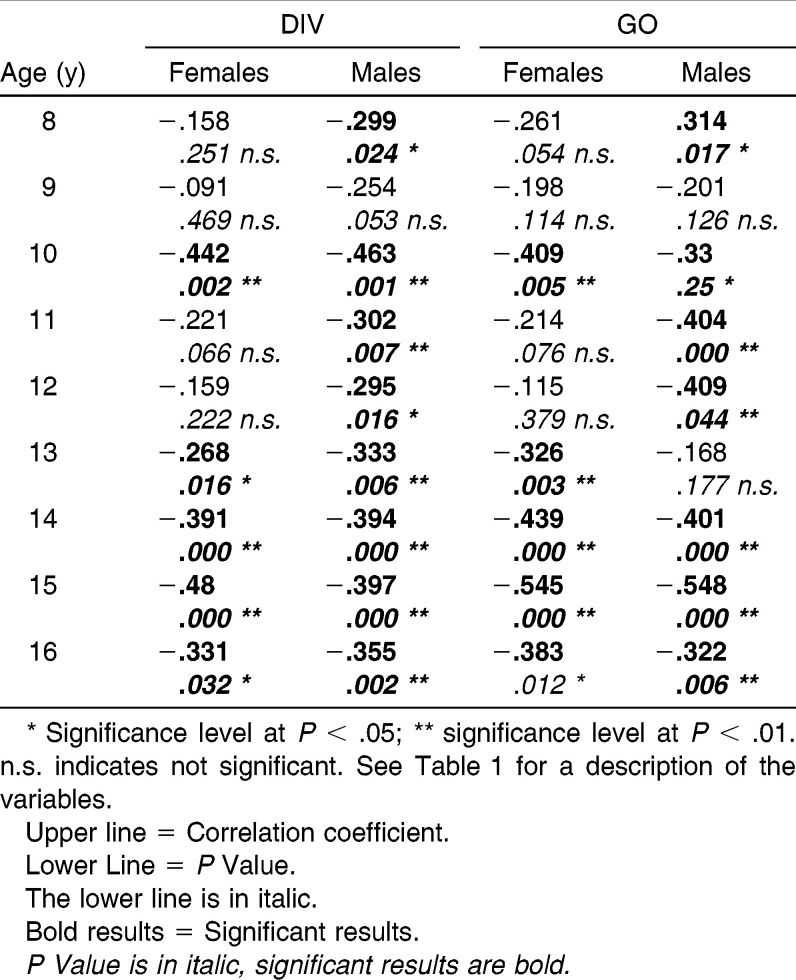

The inclination of lower incisors increased over age (8 years: girls = 93.9° [95% CI, 92.3°–95.7°], boys = 93.3° [95% CI, 91.8°–94.9°]; 16 years: girls = 96.1° [95% CI, 94.1°–98.2°], boys = 97.1° [95% CI, 95.6°–98.6°]). Inclination of lower incisors correlated with the divergence of the jaws for all ages significantly or highly significantly, except for boys and girls 9 years of age and girls 11 and 12 years of age, for which only a tendency was observed. Similarly, a strong correlation to gonial angle could be observed. No correlation could be found between the inclination of lower incisors and any symphyseal parameters (absolute measurements and ratios), except for symphyseal depth.

Conclusion:

Lower incisor inclination is linked to the subject's sex, age, and skeletal pattern. It is not associated with symphyseal dimensions, except symphyseal depth. Factors related to natural inclination of lower incisors should be respected when establishing a treatment plan.

Keywords: Lower incisor, Inclination, Cephalometry

INTRODUCTION

The assessment of radiological characteristics of the mandible has become an essential part in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. Commonly, two reasons are stated for the importance of evaluating mandibular morphology. First, the mandible is predominantly responsible for facial appearance, and its growth pattern has an indisputable impact on facial development. Second, the anatomical shape of a mandible and specifically its symphyseal characteristics are thought to reflect past growth behavior and future tendencies.1

Many efforts have been made to predict the growth of the mandible from a lateral cephalograph using several radiological parameters, with varying success. Notably, some studies attempted to determine whether the morphology of the symphysis could be used as a predictor for future mandibular growth.1–7 Björk3 and many others observed that with a backward rotation of the mandible, the anterior part of the symphysis is flattened or almost straight. In an anterior rotation, the frontal border gains prominence owing to the rotation of the symphysis. This association was echoed in another study2 demonstrating that symphysis morphology, particularly the ratio of height to width, is indicative of the direction of mandibular growth. Subjects with shorter and wider symphysis showed greater amounts of anterior mandibular growth than subjects with longer and narrower symphysis.

Björk's findings3 are considered to be of high scientific relevance due to his accurate methodology. However, their clinical significance is reduced because his study was confined to small cohorts of children with extreme growth patterns.8 The results are, therefore, inadequate to permit clinically useful predictions.6 In fact, when adopting the same morphological indicators that Björk3 or Skieller et al.7 had found to explain 86% of their cases, other investigators were not able to substantiate the associations published in the original publication.5 A further assessment showed that a prediction of mandibular rotation done by clinicians did not perform better than chance and that numerical data also failed to identify the rotation pattern.9 Hence, the predictive value of radiological indicators on a larger population sample seems modest at best. Most of the morphologic criteria described by Ricketts,1 Björk,3 or Skieller et al.7 do not contain information solid enough for a growth pattern prediction. However, there is some evidence that specifically the morphology of the symphysis2,10 and the antegonial notch depth11,12 may yield information about the growth of the mandible, although the latter has been disputed by some investigators.9,13

Based on the assumption that symphyseal morphology may, therefore, be the only reliable part of the mandible that contains information about the growth pattern of the mandible, it is of interest to discern whether the angulation of the lower incisors could be linked to a certain symphyseal morphology or other skeletal pattern.

An association between the lower incisor angulation and the rotation pattern has been postulated,1,3 but to the best of our knowledge, no investigation has been performed until now with the inclination of the lower incisors as the endpoint. This approach, although uncommon, is especially reasonable, as the angulation of the lower incisor is the only variable that can be easily modified clinically during treatment. Therefore, the aim of this present study was to revisit the inclination of lower incisors on a population far larger than in any previous study, to obtain reference values for symphyseal dimensions, and to reassess whether any symphyseal parameter or skeletal pattern could be used to disclose a change in angulation of the lower incisors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The material consisted of lateral cephalograms obtained from the Zurich Craniofacial Growth Study performed in the years 1981–1984. In the original study, healthy, untreated schoolchildren 6 to 18 years of age of White origin from local public schools were examined. The examination took place very close to the individual's birthday. In this present study, lateral cephalograms of all subjects of ages 8–16 years (1272 cephalograms; 605 females, 667 males) were used. Legal and ethical approval for releasing the data was obtained by the Federal Commission of Experts for Professional Secrecy in Medical Research.14

The lateral cephalograms were taken with the head stabilized in position by ear rods and nasal support. The Frankfort horizontal plane was set parallel to the floor, and teeth were in centric occlusion. The radiographs were taken with a focus-midsagittal plane distance of 200 cm and an enlargement of 7.5%.

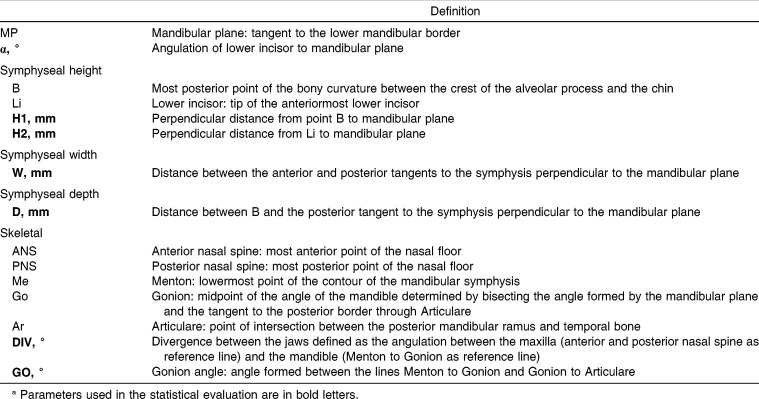

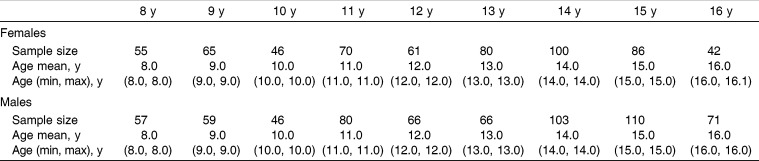

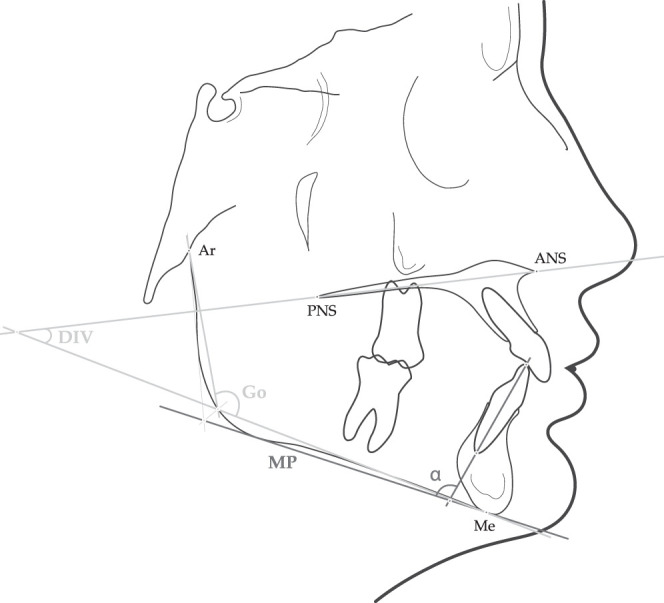

Three investigators traced and landmarked the lateral cephalograms by hand as defined in Table 1 and shown in Figures 1 and 2. The digitizing was performed using tablet digitizer Numonics AccuGrid (Numonics, Landsdale, Pa) with a resolution of 1 mil-Inch. Custom-made software was used for the calculation of the cephalometric values.

Table 1.

Figure 1.

Symphyseal parameters: heights (H1 and H2), width (W), and depth (D).

Figure 2.

Skeletal parameters: divergence of the jaws (DIV) and gonial angle (GO).

Thirty-eight cephalograms were traced a second time more than 6 months apart, 19 by the same investigator and 19 by a different investigator, in order to determine intra- and interobserver reproducibility.

Statistical Analysis

A standard statistical software package (IBM SPSS version 20; IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for data analysis. To determine intra- and interobserver reliability, the intraclass correlation coefficient for absolute agreement based on a one-way random effects analysis of variance was calculated. Descriptive statistics for the measurements were computed, and the assumption of normality of the variables was investigated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The Pearson correlation coefficient was performed to evaluate correlations between the variables. P values that were smaller than .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

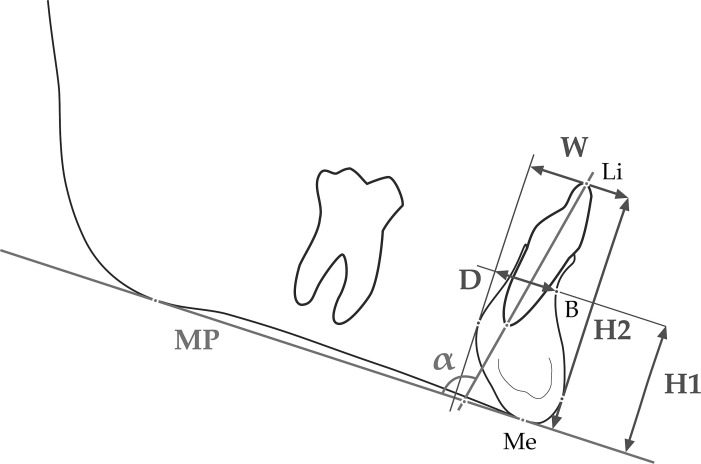

The intraclass correlation coefficient, given in Table 2, revealed a very good repeatability for all cephalometric measurements. The mean value for all measurements was .948 (min: .729; max: .995) for intraobserver repeatability and .933 (min: .700; max: .996) for interobserver repeatability, respectively.

Table 2.

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient for Intraobserver and Interobserver Repeatabilitya

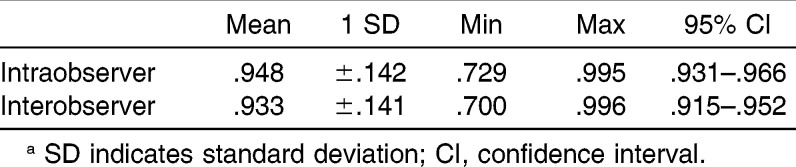

The distribution of the sample according to age and gender is listed in Table 3. Based on the fact that the records were always taken as close to the subject's birthday as possible, the mean, maximum, and minimum of the ages for each group were consistently very close to the defined group age. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test revealed a normal distribution for all investigated variables, ie, the inclination of lower incisors (α), both symphyseal heights (H1 and H2), the symphyseal width (W), and depth (D), as well as the skeletal parameters, ie, the divergence of the jaws (DIV) and gonial angle (GO). Therefore, parametric tests were used for further statistical analysis.

Table 3.

Descriptive Analysis: Sample Size and Distribution

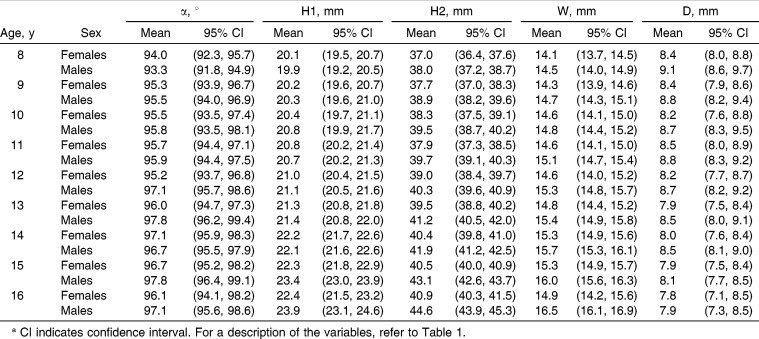

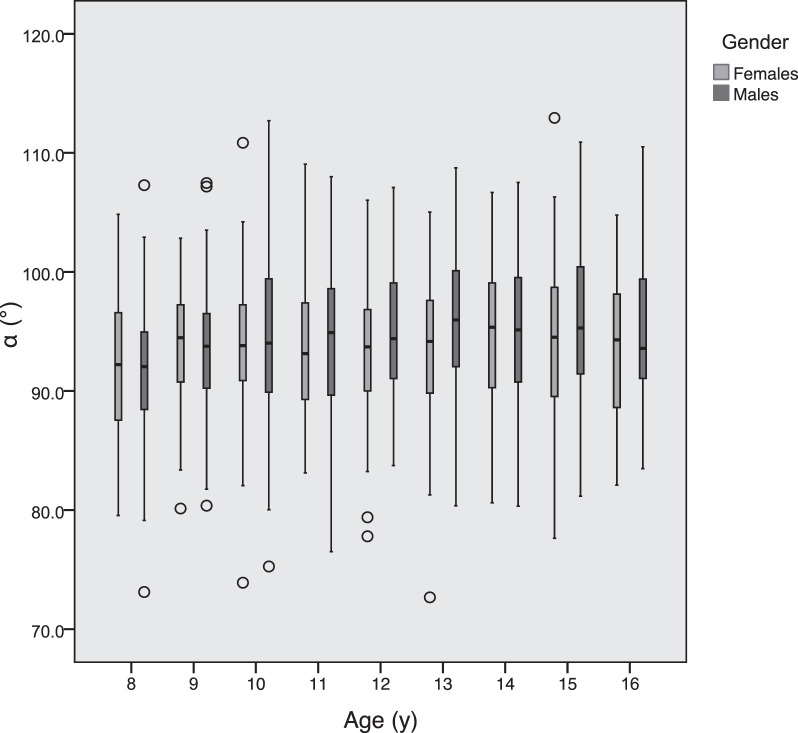

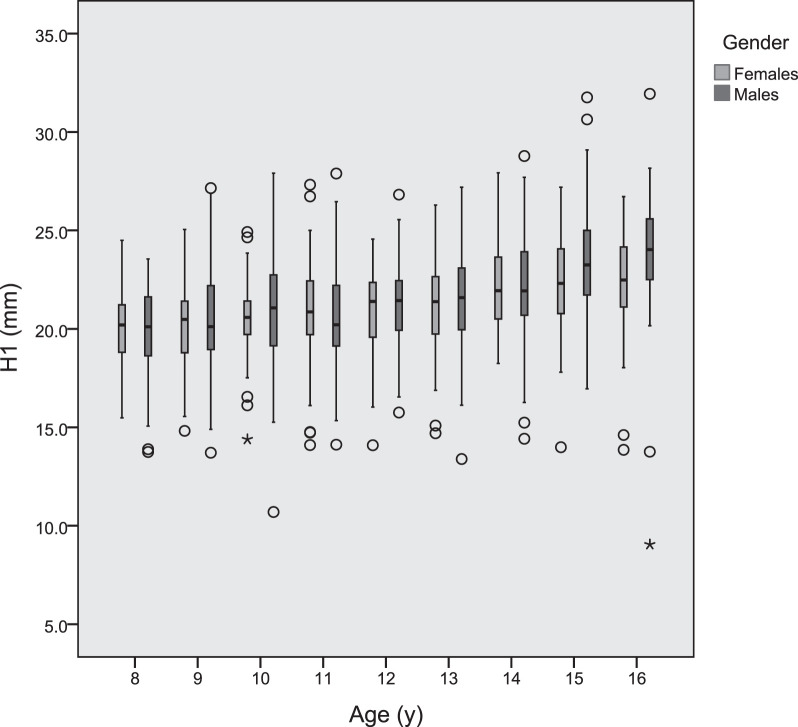

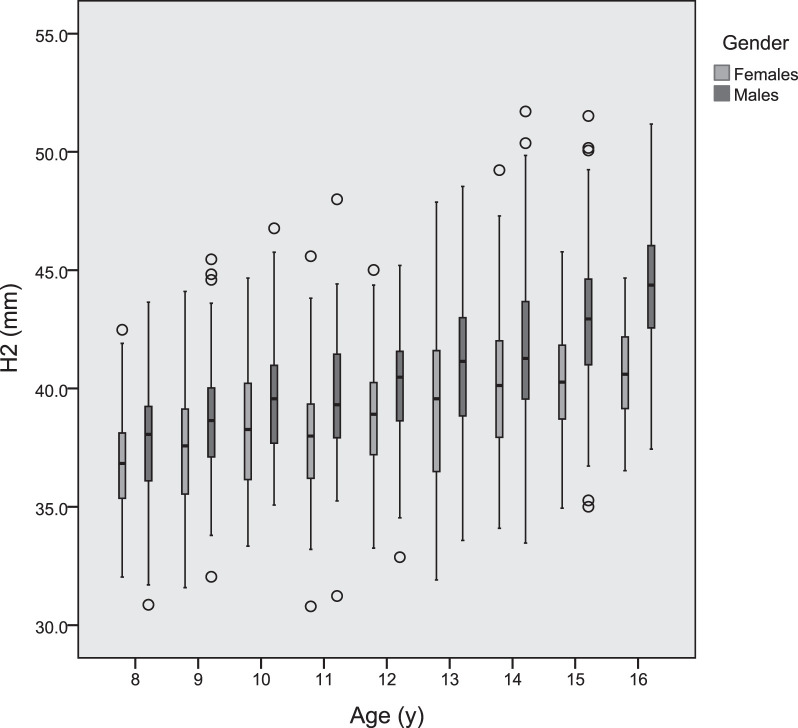

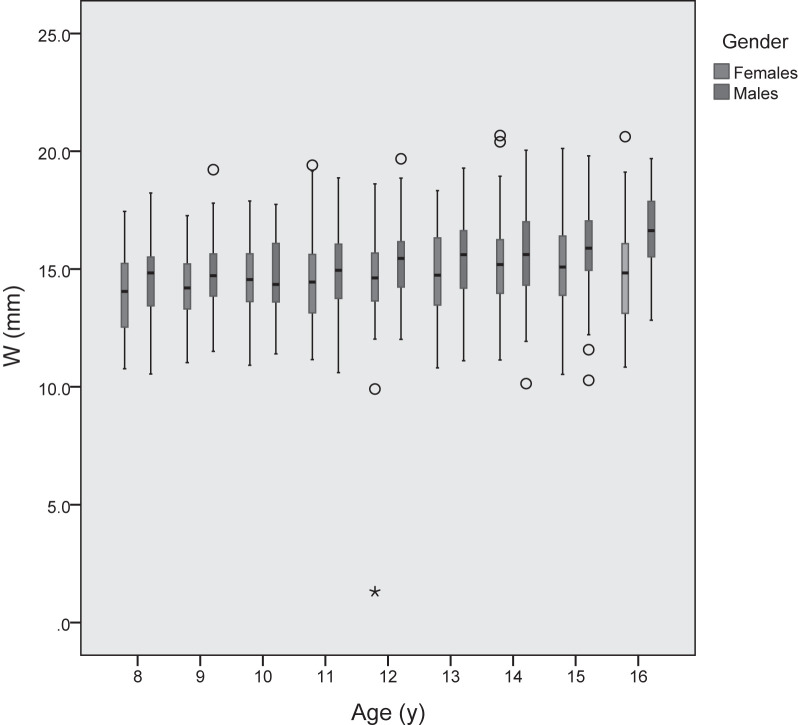

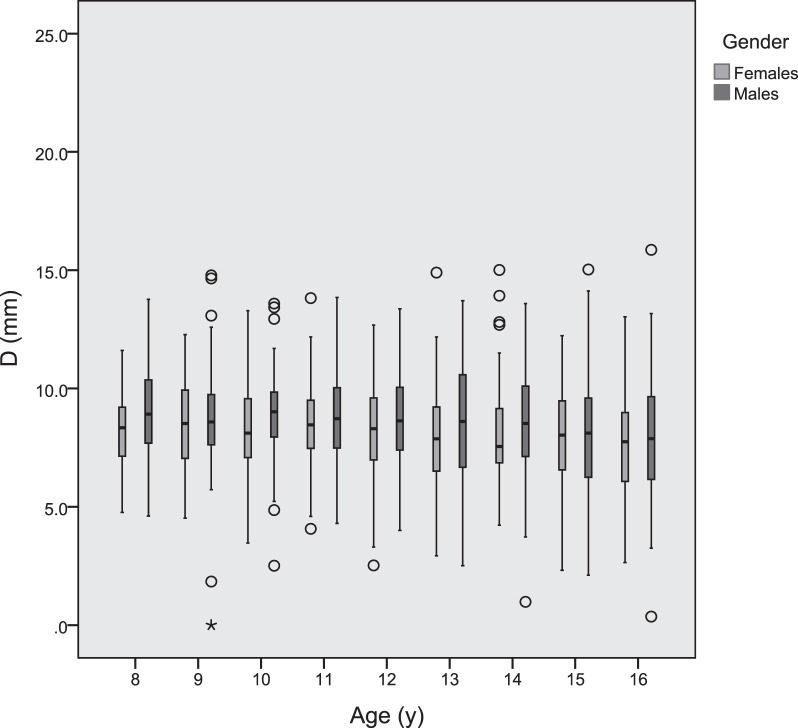

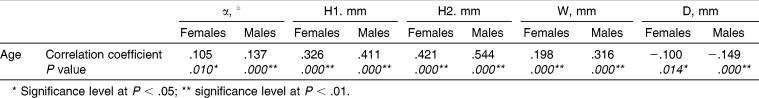

Table 4 offers an overview of the mean values and the 95% confidence intervals of the symphyseal variables α, H1, H2, W, and D. Figures 3 through 7 render those measurements in box and whisker plots. For α, H1, and W, an age-depended slight increase can be observed for both sexes. Similarly, an age-depended increase can be detected for H2, more pronounced in males. The symphyseal depth D decreases during the observed period.

Table 4.

Descriptive Analysis of the Symphyseal Variablesa

Figure 3.

Box-and-whisker plot for α.

Figure 4.

Box-and-whisker plot for symphyseal height (H1).

Figure 5.

Box-and-whisker plot for symphyseal height (H2).

Figure 6.

Box-and-whisker plot for symphyseal width (W).

Figure 7.

Box-and-whisker plot for symphyseal depth (D).

The correlation analysis revealed highly significant age dependency for all absolute symphyseal measurements in males, and significant to highly significant age dependency in females. The results of this correlation analysis are given in Table 5.

Table 5.

Symphyseal Configuration: Correlations of Absolute Measurements With Age (Correlation Coefficient and P Value)

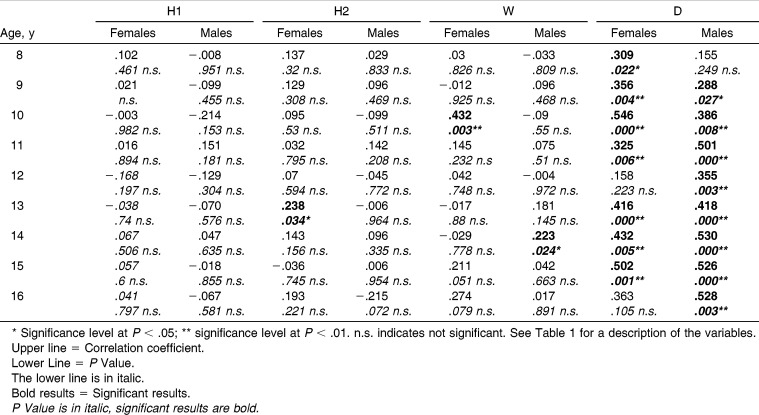

Table 6 demonstrates that no correlation to lower incisor inclination (α) could be found for H1 at any age or for H2 and W at almost any age (three exceptions) for both genders. In stark contrast, the symphyseal depth, however, correlated highly significantly with α for most of the ages. Additionally, the correlations between α and symphyseal ratios were studied in order to avoid biases derived from absolute measurements. The height-width ratios (both H1/W and H2/W) were analyzed as well as the depth-width (D/W) ratio. Table 7 reveals that no correlations could be established for H1/W and H2/W for almost all ages, males and females alike (two exceptions). Again, in apparent contrast, lower incisor inclination (α) correlated highly significantly with the depth-width ratio in both genders for nearly all ages.

Table 6.

Symphyseal Configuration: Correlations of Absolute Measurements With α (Correlation Coefficient and P Value)

Table 7.

Symphyseal Configuration: Correlations of Ratios With α (Correlation Coefficient and P Value)

Moreover, the correlations between lower incisor inclination (α) and the skeletal pattern were examined. Two reference values, the jaw divergence and gonial angle, were used to portray the skeletal pattern. The results are subsumed in Table 8. Significant and highly significant correlations could be observed, more prominently in males than females, and more recurrently in later stages of childhood.

Table 8.

Skeletal Pattern: Correlations of Angulations With α (Correlation Coefficient and P Value)

DISCUSSION

The rationale behind this present study was to investigate associated factors for lower incisor angulation. This angulation has a twofold relevance. First, the lower incisors play an essential role in orthodontic treatment planning because of their very restricted anatomical leeway, and excessive tipping may result in significant recession of the gingival margin and in bony dehiscences.15–21 Hence, reference values for both genders at all ages could prove to be useful. Second, as mentioned in the introduction, many attempts have have been made to discern whether symphyseal morphology contains information about the growth pattern of the mandible.1–7 It is, therefore, of interest to evaluate whether the angulation of the lower incisors could be linked to a certain symphyseal morphology or skeletal pattern.

Although the Zurich Craniofacial Growth Study is not based on serial long-term longitudinal samples, it was favored for this present investigation for two reasons. First, the large sample size of untreated subjects permitted a division of the data into subgroups by gender and age, while leaving every subgroup with enough statistical power. Second, the data collection was consistently performed very close to the subject's birthday, rendering thresholding for age groups unnecessary.

Sexual dimorphism in the facial dimensions is a fact that has been established by various analyses.22–25 Therefore, the present data had to be divided by gender in order to maintain the homogeneity of the sample.

The results reveal that the individual variation of all the parameters measured is substantial. Therefore, mean values can only be applied to individual cases with caution.26 Yet, when evaluating the data, some tendencies can be discerned that are of evident clinical importance. So, even if some correlation coefficients might be low at certain ages, it is the recurrent appearance of statistical significance that has to be considered and appraised.

Our study demonstrates an age dependency of lower incisor angulation. Throughout childhood, lower incisors become significantly more proclined. This phenomenon is more accentuated in males, with an increase of nearly 4° on average, than in females, with an increase of a little more than 2° on average. In light of this finding, treatment planning in growing patients should respect the fact that in the final result the lower incisors should be slightly more proclined than before treatment.

Our findings are in accordance with the reference values established by Bhatia and Leighton.27 However, the reference values of Riolo et al.28 only corroborate the observation of a more pronounced protrusion for males, but they do not reflect an age-dependent increase.

This study examined symphyseal parameters in order to establish reference values and to associate those values with lower incisor angulation. Reference values of symphyseal dimensions are essential, as it is commonly agreed that an especially narrow symphysis is an etiological factor in the development of fenestrations and dehiscences.29,30 Although symphyseal parameters have already been studied in earlier works, the present results can only be compared to those numbers with caution, as the definition and identification of symphyseal landmarks may differ from author to author, rendering a direct comparison of absolute values questionable. In agreement with our findings, other authors also attested to a continuous increase of symphyseal height throughout the entire observed childhood,2,27,28 which stands in contrast to the unaltered lower incisor angulation in later childhood. Furthermore, an additional observation is supported by the literature: The very modest gain in symphyseal height up to point B (distance H1)27 and the excessive vertical increase for symphyseal height up to the tip of the lower incisors (distance H2).2,28 This discovery, ie, that most of the changes occur in the dentoalveolar part of the symphysis, seems to reflect previous statements that the anterior basal part of the symphysis remains a stable landmark.3,31 Similarly, only little alteration can be witnessed in symphyseal width (distance W), with an increase of 1 mm for females and 2 mm for males over the entire observed period. This is in agreement with Riolo et al.28 but not with Aki et al.,2 who measured a more significant increase in the sagittal dimension of the symphysis.

The results indicate that the lower incisor inclination is not associated with symphyseal height or width. Similarly, the assessed height-width ratios (H1/W and H2/W) revealed no relationship. Yet, unexpectedly, symphyseal depth correlates noticeably with the examined angle. This is a striking, as-yet-undescribed revelation. The natural inclination of the lower incisor seems to be linked to the available space posteriorly. This fact is probably not appreciated enough. In regard to symphyseal configuration, the focus has been laid mostly on the anterior part of the symphysis in order to disclose a certain skeletal pattern and, with it, the proclination of lower incisors. Our study, however, indicates that it is not the morphology of the anterior part of the symphysis but rather the posterior space available for the apex of the incisors that seems to be of higher relevance to determine the correct inclination. Further studies should investigate the interpretation of this correlation, as our study merely illustrates a biological association, and no cause and effect relationship can be judged based on this statistical link.

In order to determine a link between the skeletal pattern and the angulation of the lower incisors, two representative variables, indicative of the skeletal pattern, were selected: the divergence of the jaws and the gonial angle. The divergence of the jaws is commonly used to categorize the rotation pattern,2,4 and the gonial angle has been shown to be a dependable parameter for the assessment of the rotation pattern.4,22,32–35 When evaluating the association with the skeletal background, both the divergence of the jaws and the gonial angle showed significant to highly significant negative correlations with the lower incisor angulation. A pronounced divergence of the jaws and an obtuse gonial angle are related to retroclined incisors. The observed correlation is stronger in males than females, and it is incontestably more prominent in later stages of childhood. This finding contains clinically relevant information. It is evident that if the natural inclination is dependent on the subject's skeletal pattern, it should be assumed that in treatment planning, this association should be respected as well. Moreover, the fact that the link between lower incisor inclination and skeletal background is more intensified in late puberty might be the reason why this association is not fostered in all studies.

In regard to the skeletal pattern, this study is limited to the investigation of vertical parameters, and it should be noted that both skeletal parameters assessed are topographically correlated, as they both share the mandibular plane as a reference line. Moreover, it would undoubtedly be of clinical interest to examine the influence of sagittal skeletal dimensions. These aspects should be included in further studies.

CONCLUSIONS

Lower incisor inclination is not associated with most symphyseal distances, except symphyseal depth.

Lower incisor angulation, however, is linked to the subject's sex, age, and skeletal vertical pattern.

When appraising dentofacial development, the factors that influence the natural inclination of lower incisors should be taken into account.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ricketts CM. Cephalometric synthesis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1960;46:647–673. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aki T, Nanda RS, Currier GF, Nanda SK. Assessment of symphysis morphology as a predictor of the direction of mandibular growth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994;106:60–69. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(94)70022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjork A. Prediction of mandibular growth rotation. Am J Orthod. 1969;55:585–599. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(69)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sassouni V. A classification of skeletal facial types. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1969;55:109–123. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(69)90122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee RS, Daniel FJ, Swartz M, Baumrind S, Korn EL. Assessment of a method for the prediction of mandibular rotation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;91:395–402. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leslie LR, Southard TE, Southard KA, et al. Prediction of mandibular growth rotation: assessment of the Skieller, Bjork, and Linde-Hansen method. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114:659–667. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skieller V, Bjork A, Linde-Hansen T. Prediction of mandibular growth rotation evaluated from a longitudinal implant sample. Am J Orthod. 1984;86:359–370. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9416(84)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lux CJ, Conradt C, Stellzig A, Komposch G. Evaluation of the predictive impact of cephalometric variables. Logistic regression and ROC curves. J Orofac Orthop. 1999;60:95–107. doi: 10.1007/BF01298960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumrind S, Korn EL, West EE. Prediction of mandibular rotation: an empirical test of clinician performance. Am J Orthod. 1984;86:371–385. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9416(84)90029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjork A, Skieller V. Normal and abnormal growth of the mandible. A synthesis of longitudinal cephalometric implant studies over a period of 25 years. Eur J Orthod. 1983;5:1–46. doi: 10.1093/ejo/5.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singer CP, Mamandras AH, Hunter WS. The depth of the mandibular antegonial notch as an indicator of mandibular growth potential. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;91:117–124. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambrechts AH, Harris AM, Rossouw PE, Stander I. Dimensional differences in the craniofacial morphologies of groups with deep and shallow mandibular antegonial notching. Angle Orthod. 1996;66:265–272. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1996)066<0265:DDITCM>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolodziej RP, Southard TE, Southard KA, Casko JS, Jakobsen JR. Evaluation of antegonial notch depth for growth prediction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;121:357–363. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.121561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Expertenkommission für das Berufsgeheimnis in der medizinischen Forschung. Sonderbewilligung zur Offenbarung des Berufsgeheimnnisses zu Forschungszwecken im Bereich der Medizin und des Gesundheitswesen. 2011:7640–7642. In: Bundesblatt, Volume 42, ed. Berne, Switzerland: The Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation; [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiner GG, Pearson JK, Ainamo J. Changes of the marginal periodontium as a result of labial tooth movement in monkeys. J Periodontol. 1981;52:314–320. doi: 10.1902/jop.1981.52.6.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batenhorst KF, Bowers GM, Williams JE., Jr Tissue changes resulting from facial tipping and extrusion of incisors in monkeys. J Periodontol. 1974;45:660–668. doi: 10.1902/jop.1974.45.9.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarikaya S, Haydar B, Ciger S, Ariyurek M. Changes in alveolar bone thickness due to retraction of anterior teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;122:15–26. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.119804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yared KF, Zenobio EG, Pacheco W. Periodontal status of mandibular central incisors after orthodontic proclination in adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:6.e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorfman HS. Mucogingival changes resulting from mandibular incisor tooth movement. Am J Orthod. 1978;74:286–297. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(78)90204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollender L, Ronnerman A, Thilander B. Root resorption, marginal bone support and clinical crown length in orthodontically treated patients. Eur J Orthod. 1980;2:197–205. doi: 10.1093/ejo/2.4.197-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wennstrom JL, Lindhe J, Sinclair F, Thilander B. Some periodontal tissue reactions to orthodontic tooth movement in monkeys. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nanda SK. Patterns of vertical growth in the face. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988;93:103–116. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(88)90287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schudy FF. The rotation of the mandible resulting from growth: its implications in orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 1965;35:36–50. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1965)035<0036:TROTMR>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siriwat PP, Jarabak JR. Malocclusion and facial morphology is there a relationship? An epidemiologic study. Angle Orthod. 1985;55:127–138. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1985)055<0127:MAFMIT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bishara SE, Jakobsen JR. Longitudinal changes in three normal facial types. Am J Orthod. 1985;88:466–502. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9416(85)80046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumrind S, Ben-Bassat Y, Korn EL, Bravo LA, Curry S. Mandibular remodeling measured on cephalograms. 1. Osseous changes relative to superimposition on metallic implants. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992;102:134–142. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(92)70025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhatia SN, Leighton BC. A Manual of Facial Growth. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riolo ML, Moyers RE, McNamara JA, Jr, Hunter WS. An Atlas of Craniofacial Growth. Ann Arbor, Mich: Center for Human Growth and Development, University of Michigan; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Artun J, Krogstad O. Periodontal status of mandibular incisors following excessive proclination. A study in adults with surgically treated mandibular prognathism. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;91:225–232. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90450-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wehrbein H, Bauer W, Diedrich P. Mandibular incisors, alveolar bone, and symphysis after orthodontic treatment. A retrospective study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;110:239–246. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(96)80006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bjork A. Variations in the growth pattern of the human mandible: longitudinal radiographic study by the implant method. J Dent Res. 1963;42:400–411. doi: 10.1177/00220345630420014701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Opdebeeck H, Bell WH. The short face syndrome. Am J Orthod. 1978;73:499–511. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(78)90240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trouten JC, Enlow DH, Rabine M, Phelps AE, Swedlow D. Morphologic factors in open bite and deep bite. Angle Orthod. 1983;53:192–211. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1983)053<0192:MFIOBA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cangialosi TJ. Skeletal morphologic features of anterior open bite. Am J Orthod. 1984;85:28–36. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(84)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fields HW, Proffit WR, Nixon WL, Phillips C, Stanek E. Facial pattern differences in long-faced children and adults. Am J Orthod. 1984;85:217–223. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(84)90061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]