Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is a lethal malignancy with a complex microenvironment. Dichotomous tumour-promoting and -restrictive roles have been ascribed to the tumour microenvironment, however the effects of individual stromal subsets remain incompletely characterised. Here, we describe how heterocellular Oncostatin M (OSM) - Oncostatin M Receptor (OSMR) signalling reprograms fibroblasts, regulates tumour growth and metastasis. Macrophage-secreted OSM stimulates inflammatory gene expression in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), which in turn induce a pro-tumourigenic environment and engage tumour cell survival and migratory signalling pathways. Tumour cells implanted in Osm-deficient (Osm−/−) mice display an epithelial-dominated morphology, reduced tumour growth and do not metastasise. Moreover, the tumour microenvironment of Osm−/− animals exhibit increased abundance of α smooth muscle actin positive myofibroblasts and a shift in myeloid and T cell phenotypes, consistent with a more immunogenic environment. Taken together, these data demonstrate how OSM-OSMR signalling coordinates heterocellular interactions to drive a pro-tumourigenic environment in PDA.

Subject terms: Cancer microenvironment, Cell signalling, Tumour immunology

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are a major component of the desmoplastic stroma in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA). Here the authors report the importance of macrophage-derived Oncostatin M in reprogramming CAFs to drive a pro-tumorigenic environment in PDA.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is characterised by an extensive desmoplastic reaction, which constitutes on average 85% of the tumour volume1,2. Here, mutated tumour cells are embedded in a stiff, remodelled extracellular matrix (ECM), which is abundantly co-inhabited by stromal host cells3. Dysregulated immune cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are a perpetual and dynamically regulated feature throughout PDA development2,4. CD4+ regulatory T cells, myeloid derived suppressor cells and macrophages (MØs) infiltrate early during PDA development, and directly promote tumour progression through matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) and IL6 signalling, while simultaneously suppressing anti-tumour immunity4–8. Consequently, targeting MØs and granulocytes, such as through CSF1R or CXCR2 inhibitors, increases T cell infiltration and sensitises tumours to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)9,10. In addition, tumour cells conscript resident pancreatic fibroblasts to support tumour cell survival, metabolic adaptation and exclusion of CD8+ T cells11–14. Targeting CAFs and the stiff, remodelled ECM such as through vitamin D receptor agonists, lysyl oxidase and leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) blocking antibodies or CXCR4 inhibitors improves response to chemotherapy and sensitises to ICIs11,15–17. Tumour-restrictive stromal cell populations have also been described in PDA, where genetic and pharmacologic ablation of CAFs accelerates disease progression and metastatic dissemination18–21. Yet, the mechanisms by which discrete stromal populations coordinate to regulate specific tumour functions remain incompletely characterised2,22.

Single-cell analysis has been instrumental in annotating individual stromal cell populations21,23–27. Recently, several distinct CAF populations have been identified, including myofibroblastic CAFs (myCAF), defined by elevated αSMA expression and ECM modulating features; inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), defined by expression of several inflammatory genes; and antigen-presenting CAFs (apCAFs), defined by expression of MHCII and CD7421,27–30. The transcriptional state of these CAF populations is dynamically regulated, and pharmacological intervention can therefore be used to manipulate these CAF subsets in vitro and in vivo29,30. Several signals have been demonstrated to induce specific CAF subtypes, where tissue stiffness, TGFβ signalling and spatial proximity to tumour nests induce myCAF features, whilst tumour cell-secreted IL1α drives the iCAF phenotype through the JAK-STAT pathway29,30. Importantly, CAF and immune cell regulation of PDA pathobiology is highly interdependent, where targeting individual populations is accompanied by a concomitant adaptation of the tumour microenvironment (TME). For example, ablation of αSMApos or FAPpos CAFs sensitises tumours to ICIs, targeting the stiff ECM alters immune infiltration, and pharmacologic and genetic manipulation of individual immune subsets drastically alters CAF functions10,11,15,19,20,23,31. Consequently, determining the functional interdependencies between dynamically regulated CAF subsets, immune infiltrates and tumour cell function remains critical to ascertain the benefits of stromal targeting strategies.

In this work, we explore the impact of heterocellular interactions across tumour cells, fibroblasts and MØs on PDA pathobiology. We observe that tumour cell-derived granulocyte–MØ colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) induces expression of Oncostatin M (OSM) in MØs, which in turn induces expression and secretion of pro-tumourigenic inflammatory mediators, such as IL6 family members (e.g. IL6 and LIF) and CXC- and CC- chemokines (CXCL1, CCL2 and CCL7), in stromal fibroblasts. This aberrant signalling milieu engages survival, motility and cell migration signalling pathways in tumour cells to accelerate metastasis. Pancreatic cancer cells (PCCs) orthotopically transplanted into immune-competent mice lacking Osm (Osm−/−) generate significantly smaller tumours which exhibit an altered microenvironment with a reduction in tumour-promoting cytokines and chemokines (IL6, CXCL1, TNFα and GM-CSF) and increased abundance of αSMApos myofibroblasts. The cognate OSM receptor, OSMR, is expressed in mesenchymal stromal cells, and in particular in fibroblasts and perivascular cells. Notably, OSMR expression level is correlated with inflammatory gene expression, a tumour-permissive immune infiltrate and a poor overall survival in human PDA. Taken together, the data presented establishes a role of OSM-OSMR signalling in driving an inflammatory microenvironment and supporting tumour growth.

Results

OSMR expression is associated with tumour-promoting inflammation and poor outcome in PDA

PDA progression is accelerated by an extensive fibroblast expansion and a concomitant myeloid cell infiltrate2,4. Several tumour cell-derived signals have been shown to regulate fibroblast function29,30,32, however, it is less clear whether other cell populations in the tumour ecosystem influence CAF function. To identify and characterise novel stromal receptor and ligand pair(s) that may regulate CAF function, we re-analysed available RNA-seq data of murine and human PDA. Differential gene expression analysis of iCAF and myCAF subsets29 identified several membrane receptors, such as Osmr, Antxr1 and Il1r1, which were expressed at a higher level in iCAFs (Fig. 1a). Single-cell RNA-sequencing confirmed expression of Osmr, Antxr1 and Il1r1 in CAFs as well as in endothelial and perivascular cells in both human and murine PDA27,33. Moreover, these receptors were expressed at higher levels in iCAFs compared to myCAFs and apCAFs (Fig. 1b, c and Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). To further analyse OSMR expression in human resected PDA we used multiplexed in situ mRNA hybridisation for OSMR with immunofluorescence for Vimentin (to broadly demark stroma) and pan-Cytokeratin (to demark epithelial cells) (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1c). Consistent with the scRNA-seq data, OSMR was broadly expressed within the VIMpos tumour stroma, however, OSMR-positive cells were also observed within the epithelium (PanCKpos) cells.

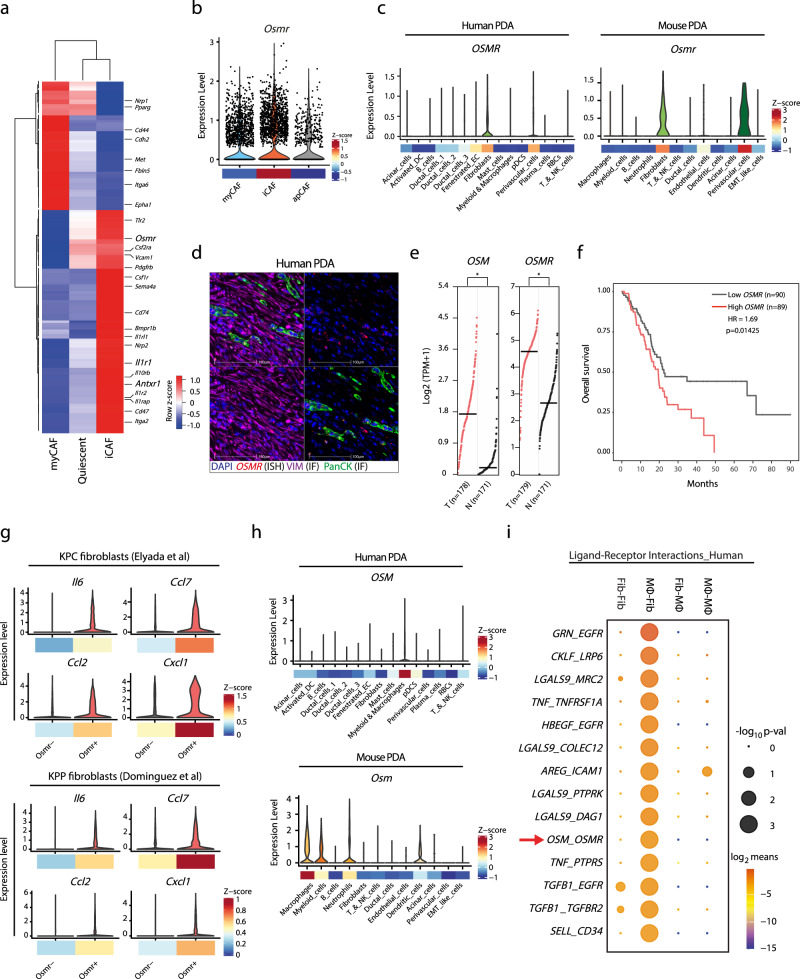

Fig. 1. OSMR expression is associated with tumour-promoting inflammation and poor outcome in PDA.

a Heatmap displaying relative expression levels of membrane receptors of stellate cells adopting a quiescent, inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts (iCAF), or myofibroblastic CAF (myCAF) phenotype (dataset: GSE93313). b Violin plot of normalised Osmr expression levels in myCAF, iCAF, and apCAFs in murine PDA (dataset: GSE129455) with mean expression z-scores shown below. c Violin plots of normalised OSMR/Osmr expression levels for individual cell types in human (left) and murine (right) PDA (top) and mean expression z-scores shown below (datasets: GSE129455, phs001840.v1.p1). d Representative in situ mRNA hybridisation (ISH) of OSMR multiplexed with immunofluorescence of VIM and PanCK in human PDA (n = 3). 20× magnification. Upper left quadrant, full overlay; upper right, OSMR; lower left, OSMR with VIM; lower right, OSMR with PanCK. Scale bar = 100 μm. e OSM (left) and OSMR (right) expression in human PDA (TCGA PanCancer PAAD dataset, n = 178) and normal pancreatic tissue (GTEx, n = 171). Mantel–Cox test. T tumour, N normal, TPM transcripts per million. f Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing overall survival of 179 PDA patients from TCGA PanCancer PAAD dataset. Patients were stratified by high (Top 50%, n = 89) and low (bottom 50%, n = 90) OSMR expression levels. Analysis by log-rank test and cox-proportional hazard regression. HR hazard ratio. g Violin plots of inflammatory gene expression in Osmrpos and Osmrneg CAFs in murine PDA tumours (datasets: GSE129455, MTAB-8483) with mean expression z-scores shown below. h Violin plots of normalised OSM/Osm expression across cell types of human (top) and murine (bottom) PDA (datasets: GSE129455, phs001840.v1.p1). Mean expression z-scores shown. i Top 14 predicted interactions between macrophage-derived ligands and fibroblast expressed receptors using CellPhoneDB receptor–ligand interaction statistical analysis (p-values < 0.05). Also see Supplementary Fig. 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To then determine whether expression of OSMR, ANTX1 and IL1R1 was correlated with patient prognosis, we studied their association with patient survival. Analysis of normal tissue samples (GTEx) and human PDA tumours (TCGA PanCancer PAAD) revealed a significantly higher expression level of OSMR and its cognate ligand, OSM, in human PDA compared to normal pancreatic tissue (Fig. 1e). Moreover, of the three iCAF-enriched receptors analysed, OSMR was the only receptor where expression was associated with poor outcome in PDA patients, where PDA patients with higher mRNA expression levels of OSMR exhibited worse overall survival than patients with lower OSMR expression (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1d). Further investigating the association between Osmr expression and the iCAF phenotype in vivo, we compared the expression of inflammatory mediators in Osmrpos and Osmrneg CAFs using publicly available scRNA-seq datasets of KPC27 and KPP33 tumours, which revealed elevated expression of Il6, Ccl2, Ccl7 and Cxcl1 in Osmrpos CAFs (Fig. 1g).

To investigate how the OSM–OSMR ligand–receptor interaction may be regulated in PDA, we analysed the expression pattern of cognate ligands for Osmr, Il1ra and Antxr1 receptors in both human and murine scRNA-seq datasets. OSM was expressed in MØs and myeloid cells in both murine and human PDA, as well as in murine neutrophils and dendritic cells (Fig. 1h), contrasting a broader expression of IL1R1 and ANTXR1 ligands (Supplementary Fig. 1e). This data indicated that myeloid/MØ-secreted OSM may act in a paracrine manner on OSMR-expressing mesenchymal cells, such as fibroblasts. To test this hypothesis, we subjected publicly available scRNA-seq datasets of human and mouse PDA to CellPhoneDB analysis and evaluated MØ–fibroblast ligand–receptor interactions27,34. This analysis further highlighted OSM–OSMR as a stromal paracrine signal conserved across both human and mouse PDA (Fig. 1i and Supplementary Fig. 1f–h). Given an established role of CAFs as fibroinflammatory regulators, we hypothesised that heterocellular OSM–OSMR signalling may induce inflammatory fibroblasts in PDA.

MØ–tumour cell interactions induce inflammatory fibroblasts in vitro

To further analyse heterocellular OSM–OSMR signalling, we firstly determined whether co-cultures of pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), PCCs and MØs in vitro increase the production of inflammatory mediators. We, therefore, quantified the abundance of 30 soluble inflammatory signals in the conditioned medium from mono- and co-cultures of PCCs, PSCs and MØs, by LUMINEX (Fig. 2a). Media from 2-way (2 W) co-cultures of PCC–PSC and PCC–MØ displayed moderately elevated levels of several tumour-promoting signals compared to mono-cultured PCCs, PSCs and MØs (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a)17,35,36. Furthermore, despite seeding an equal total cell number, 3-way (3 W) co-cultures of PCCs, PSCs and MØs lead to a profound change in the signalling milieu with a further increased abundance of 22 cytokines and chemokines (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Notably, several pro-tumoural signals (e.g. IL6, LIF, CXCL1, GM-CSF and CCL2), known to cause stromal activation and immunosuppression in PDA, increased drastically (Supplementary Fig. 2a)5,17,35–37. Thus, heterocellular interactions between tumour cells, MØs and stromal fibroblasts accentuate secretion of inflammatory signals in vitro.

Fig. 2. Macrophage–tumour cell interactions induce inflammatory fibroblasts in vitro.

a Heatmap showing relative levels of soluble signals quantified by LUMINEX, clustered with unsupervised hierarchical clustering (n = 3 per culture condition). b Heatmap of relative expression levels of soluble signals measured by RT-qPCR, clustered with unsupervised hierarchical clustering (n = 4 per culture condition). c Volcano plot showing differentially regulated genes (DEGs) of PSCs isolated from PCC–PSC (n = 4) and PCC–PSC–MØ (n = 4) co-cultures. 3 W: PCC–PSC–MØ co-culture. 2 W: PCC–PSC co-culture. FC fold change. d Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of RNAseq data from (c). NES normalised enrichment score, FDR false discovery rate. e RT-qPCR assay of selected myofibroblastic and inflammatory genes of PSCs stimulated with conditioned medium from 2 or 3 W co-cultures using different isolations of PCCs (PCC, PCC4 and PCC11). Left: Changes in expression state visualised by principle component analysis (PCA) across experimental conditions (n = 4). Right: Representative mRNA expression of inflammatory (Il6, Il4ra and Cxcl1) and myofibroblastic (Acta2) genes. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, n = 4, one-way ANOVA Tukey test. f RT-qPCR of selected myofibroblastic and inflammatory genes in PSCs stimulated with conditioned medium from 1, 2 or 3 W co-cultures of PCC, PSC and bone marrow-derived MØs. Left: Changes in expression state visualised by PCA plot across experimental conditions (n = 4). Right: Representative mRNA expression of inflammatory (Il6, Il4ra and Cxcl1) and myofibroblastic (Acta2) genes. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, n = 4, one-way ANOVA Tukey test. g Mass cytometry analysis of PSCs in mono- (n = 3) and co-culture with PCC (n = 3) or PCC and MØs (n = 3). Self-organising map clustering (FlowSOM) of PSCs in mono- and co-cultures displayed as t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbour Embedding (tSNE). h Mass cytometry analysis of PSCs from 3 W PCC–PSC–MØ co-culture. Number of macrophages plated in 3 W co-culture was titrated down and PDPN, CD73 and Integrin α5 expression levels shown as biaxial plots. Also see Supplementary Fig. 2. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To subsequently determine the cellular source(s) of individual signals, we FACS-isolated PCCs, PSCs and MØs from mono- and co-cultures and analysed the expression level of selected signals by RT-qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Most transcripts were expressed and regulated in a cell-type specific manner (Fig. 2b). For example, MØs expressed Tnf and Osm, PSCs expressed Il6, Cxcl9 and Cxcl10, and PCCs expressed Csf2 as well as Cxcl5. Other signals, such as Ccl2 and Ccl7, were expressed in MØs co-cultured with either PCC or PCC–PSC. However, Ccl2 and Ccl7 were also expressed in PSCs isolated from 3 W co-cultures with PCCs and MØs (Fig. 2b), demonstrating context-dependent control of inflammatory gene expression. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering and principle component analysis (PCA) of mRNA levels highlight that PSCs engaged discrete secretory programmes depending on specific heterocellular interactions (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2c). In particular, PSCs isolated from PCC–PSC–MØ co-cultures (herein called 3W-PSCs) clustered separately from PSCs isolated from mono- and 2 W co-cultures (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2c left), and displayed increased expression of interleukins such as Il6, as well as CC-/CXC-ligands such as Cxcl1, Ccl2 and Ccl7 (Supplementary Fig. 2c right). In contrast, PSCs from PCC–PSC 2 W co-culture (herein called 2W-PSCs) exhibited a distinct secretory pattern with increased expression of Cxcl12, Tgfb2 and Ccl11 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2c right). The analysed ligands were not differentially expressed in PCCs or MØs isolated from mono- and co-cultures (Fig. 2b), suggesting that PSCs are particularly responsive to changes in the local cellular environment.

To further investigate whether interactions across MØs, PCCs and PSCs induce a transcriptional programme in PSCs that is consistent with iCAFs, we FACS-isolated PSCs from mono-, PCC–PSC and PCC–PSC–MØ co-cultures, and analysed mRNA expression by RNA-seq (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Gene expression analysis identified 1758 differentially regulated genes in PSCs from 2 and 3 W co-cultures. 2W-PSCs displayed increased expression of genes encoding ECM proteins including collagens Col6a1, Col11a1, Col4a5, Col4a6 as well as Acta2, (α-smooth muscle actin, αSMA) a well-documented marker of myofibroblasts (Fig. 2c)22. Similarly, inflammatory signals, many of which were identified in the conditioned medium from 3 W co-cultures (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a), were abundantly expressed in 3W-PSCs, confirming fibroblasts as a major cellular source of inflammatory signals (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2e). For example, upregulated genes in 3W-PSCs include CC-chemokines (Ccl2, Ccl7 and Ccl5), JAK-STAT (Osmr, Jak2 and Stat3) and NFκB (Chuk, Nfkb1 and Relb) pathway components, as well as NFκB target genes such as C1s, Vcan, Has2, Mt2 and Il4ra (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2e, f). Indeed, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that 3 W co-culture is associated with an enrichment of “Inflammatory Signalling”, “TNFα Signalling via NFκB pathway” and “IL6-JAK-STAT pathway” in PSCs, whereas “Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition” (EMT) and “Oxidative Phosphorylation” pathways are enriched in 2W-PSCs (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2f). These results are consistent with the previously described iCAF subsets in PDA27,29,30,33, and suggest that heterocellular interactions influence fibroblast subtypes. To determine whether the PSC subtype switch is consistent across 2 and 3 W co-cultures with different PCCs, we collected conditioned medium from 2 W PCC–PSC and 3 W PCC–PSC–MØ co-cultures using three different PCCs, and analysed the expression of selected inflammatory (Il6, Il4ra and Cxcl1) and myofibroblastic (Acta2) markers in PSCs stimulated with the conditioned medium (Fig. 2e). Indeed, 2 and 3 W PSCs displayed a transcriptional change consistent with subtype switch across all PCC (Fig. 2e, left). Whereas Acta2 was more highly expressed across all 2 W conditions, 3 W conditioned medium increased inflammatory gene expression and decreased Acta2 (Fig. 2e, right). Moreover, to assess whether the PSC subtype switch was specific to 3 W co-culture conditions, and not due to direct interactions between PSCs and MØs, we compared gene expression in PSCs treated with conditioned medium from PCCs, PSCs and MØs in mono-2W- and 3W-co-cultures. This data confirmed that only in the presence of all three cell types did PSCs decrease Acta2 expression and increase Il6, Il4ra and Cxcl1 expression (Fig. 2f).

To then confirm the co-culture-dependent switch in fibroblast function using an orthogonal readout, we profiled the expression of 26 mesenchymal markers by mass cytometry (MC) in PSCs grown as mono-culture or in 2W- or 3W- co-cultures (Supplementary Fig. 2g). This analysis demonstrated a shift in marker levels between the culture conditions (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Fig. 2h), supporting a PSC phenotypic switch between PCC–PSC and PCC–PSC–MØ co-cultures. To confirm the role of MØs, we set up a MØ-limiting titration experiment, where we decreased the number of MØs in 3 W co-culture, and quantified mesenchymal marker expression by MC (Fig. 2h). This demonstrated that markers preferentially expressed in 3W-PSCs, such as PDPN, CD73 and Integrin α5, decreased as the number of MØs was reduced in the 3 W co-culture (Fig. 2h).

Heterocellular OSM–OSMR signalling induces inflammatory fibroblasts

Consistent with the in vivo gene expression analysis (Fig. 1c, h), Osm and OsmR is differentially expressed in vitro where MØs express Osm and PSCs express Osmr (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3a). We therefore hypothesised that heterocellular OSM–OSMR signalling induces expression of inflammatory mediators in PSCs. To test this hypothesis, we analysed the expression of selected myofibroblastic and inflammatory markers in PSCs treated with recombinant OSM or conditioned medium from mono- and co-cultured PCCs, PSCs and MØs (Fig. 3b). Recombinant OSM and 3 W co-culture conditioned medium induced a transcriptional shift in PSCs distinct from mono- and 2 W PCC–PSC co-cultures, as visualised by PCA (Fig. 3b left). Specifically, recombinant OSM increased expression of inflammatory mediators, including Il6, Il4ra Cxcl1, Mt2, Nos2 and Vcan, (Fig. 3b right). Similarly, markers predominantly expressed in PSCs co-cultured with PCCs, such as Thbs1, Col4a5, Col4a6, Acta2 and Ccnd1, are decreased following OSM stimulation (Fig. 3b right). Several of these genes have previously been associated with inflammatory (iCAF) and myofibroblastic (myCAF) phenotypes, confirming an inverse relationship between iCAF and myCAF transcriptional programmes 27,29,30.

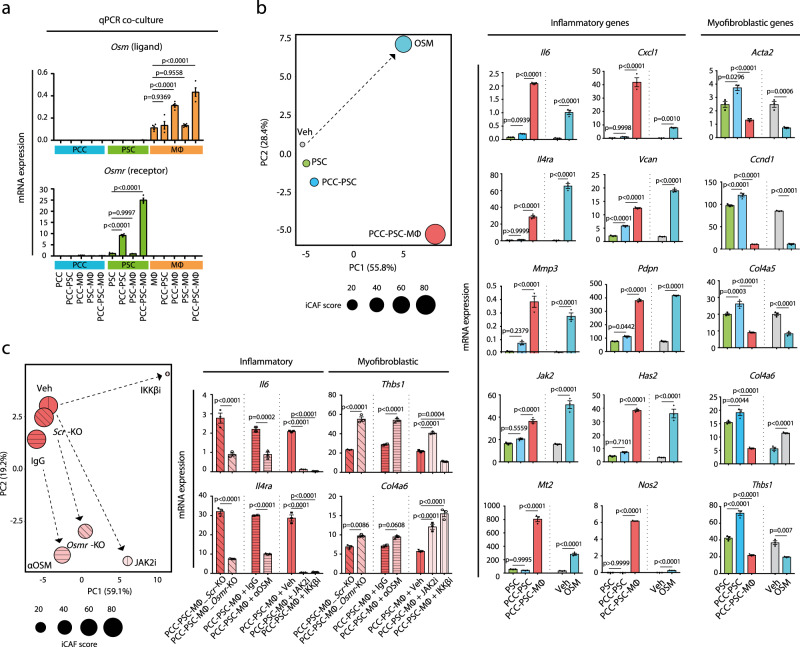

Fig. 3. Heterocellular OSM–OSMR signalling induces inflammatory fibroblasts.

a Cell-type-specific mRNA expression of Osm and Osmr across different culture conditions in vitro. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, n = 4, one-way ANOVA Tukey test. b RT-qPCR assay of myofibroblastic and inflammatory genes. PSCs were treated with recombinant OSM, conditioned medium or vehicle control, and gene expression analysis was performed. Left: Changes in expression state visualised by PCA. iCAF score is a sum of mean z-values of 15 selected inflammatory genes. Right: Representative mRNA expression of inflammatory and myofibroblastic genes of PSCs treated as indicated. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, n = 3, one-way ANOVA Tukey test. c RT-qPCR analysis of myofibroblastic and inflammatory genes in PSCs following pharmacological inhibitors and CRISPR–Cas9-medidated Osmr knockout (Osmr-KO) in PSCs. For inhibitor perturbation, PSCs were stimulated with conditioned medium supplemented with vehicle control, IKKβ inhibitor (TPCA-1, 1 µM), JAK2 inhibitor (AZD1480, 2.5 µM), control IgG antibody (2.5 ng/mL) or neutralising OSM antibody (αOSM, 2.5 ng/mL). For Osmr knockout, scrambled (Scr) control and Osmr-KO fibroblasts were stimulated with PCC–PSC–MØ conditioned medium and gene expression was analysed by RT-qPCR. Left: Changes in expression state visualised by a PCA plot. iCAF score is a sum of mean z-values of 15 selected inflammatory genes. Right: Representative mRNA expression of inflammatory (Il6 and Il4ra) and myofibroblastic (Thbs1 and Col4a6) genes of PSCs treated as indicated. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, n = 3, one-way ANOVA Tukey test. Also see Supplementary Fig. 3. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further elucidate the molecular dependencies of MØ-induced inflammatory gene expression in PSCs, we added OSM blocking or control antibodies to conditioned medium from PCC–PSC–MØ 3 W co-culture and assessed the impact on PSC gene expression (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3b). As inflammatory PSCs isolated from 3 W co-cultures were associated with increased JAK-STAT and NFκB pathway activation (Fig. 2d), we also included respective pharmacological inhibitors (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3b). As anticipated, and in agreement with previous observations30, inhibition of JAK2 and IKKβ reduced the expression of inflammatory mediators while simultaneously increasing expression of myofibroblastic genes. This resulted in a transcriptional state more similar to 2W-PSCs (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3b). Similarly, inclusion of an OSM blocking antibody in 3 W conditioned medium also induced a transcriptional shift in the PSCs, marked by decreased expression of inflammatory mediators and increased expression of myofibroblastic genes (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3b). The effect of the OSM blocking antibody as well as the JAK-STAT and NFκB pathway inhibitors was replicated using CRISPR–Cas9 mediated knockout of Osmr in PSCs (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 3b), confirming a role for OSM–OSMR signalling in inducing inflammatory gene expression in PSCs. Notably, inclusion of neutralising antibodies against previously described regulators of inflammatory fibroblasts, such as TNFα, IL1α and IL1β30, differentially influences fibroinflammatory gene expression when compared to OSM–OSMR-targeting modalities (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). For example, the OSM blocking antibody decreased expression of inflammatory genes such as Il6, Il4ra, Jak2, Has2, Vcan and Nos2, and increased myofibroblastic genes such as Thbs1 and Ccnd1 (Supplementary Fig. 3c). However, neutralising antibodies for OSM, TNFα and IL1β were needed in combination (“OTI”) to efficiently block Mmp3, Pdpn and Nt5e (Supplementary Fig. 3c). In addition, an IL1α neutralising antibody did not alter 3W-PSC gene expression differentially to an IL1β neutralising antibody (Supplementary Fig. 3d). This suggests that MØ-induced inflammatory genes in fibroblasts relies on multiple combinatorial signals. Together, this demonstrates a requirement of heterocellular OSM–OSMR signalling as a potent inducer of inflammatory fibroblasts.

Tumour cell-secreted GM-CSF increases MØ secretion of OSM

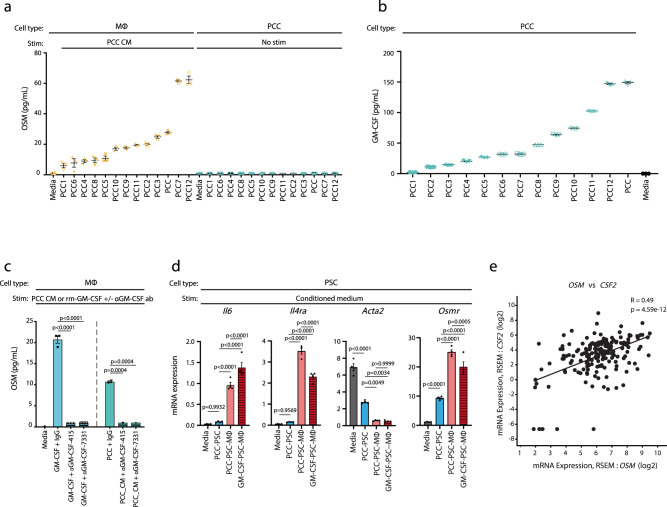

To identify putative Osm inducing signals, we treated MØs with PCC conditioned medium and determined OSM levels in conditioned medium by ELISA (Fig. 4a). None of the tested PCC cell lines produced OSM in mono-culture, however, conditioned medium from all 13 PCC lines increased OSM levels in MØs (Fig. 4a). To subsequently determine which PCC-derived signals induce OSM, we treated MØs with recombinant signals identified in the LUMINEX analysis of PCC conditioned medium (Fig. 2a), and measured OSM in the conditioned medium by ELISA (Supplementary Fig. 4). Strikingly, GM-CSF was the only tested soluble factor that induced OSM secretion (Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, increased levels of GM-CSF were generally observed in the conditioned medium of PCCs that strongly induced OSM (Fig. 4b). To functionally confirm a role of PCC-secreted GM-CSF, we collected PCC conditioned medium and included control or GM-CSF neutralising antibodies before stimulating MØs and measuring OSM by ELISA. GM-CSF neutralising antibodies blocked OSM secretion from MØs when added to PCC conditioned medium and recombinant GM-CSF (Fig. 4c), confirming that PCC-produced GM-CSF is a key regulator of OSM secretion. We then sought to determine whether GM-CSF could substitute PCCs in 3 W co-cultures to induce expression of inflammatory signals in PSC and added recombinant GM-CSF to PSC–MØ co-cultures and stimulated PSCs with the conditioned medium. Recombinant GM-CSF–PSC–MØ cultures induced both Osmr and inflammatory gene expression in PSCs (Fig. 4d). Together this data supports a role of GM-CSF in inducing Osm expression in MØs, thereby enabling MØ-induced inflammatory gene expression in fibroblasts. Finally, analysis of TCGA PanCancer PAAD dataset identified a positive correlation of OSM expression levels and CSF2 (encoding GM-CSF) expression in PDA patients (Fig. 4e), highlighting a clinical association between GM-CSF and OSM expression in PDA. Collectively, these findings imply GM-CSF as a positive regulator of MØ OSM secretion.

Fig. 4. Tumour cell-secreted GM-CSF increases macrophage secretion of OSM.

a Quantification of OSM levels in conditioned medium from bone-marrow-derived MØs stimulated with conditioned medium from PCC lines. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, n = 3. CM conditioned medium. b Quantification of GM-CSF levels in conditioned medium of PCC cell lines. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, n = 3. c Quantification of OSM levels in conditioned medium of bone-marrow-derived MØs stimulated with either recombinant murine GM-CSF (rm-GM-CSF) or PCC conditioned medium in the presence of neutralising GM-CSF antibodies (αGM-CSF-415, 1 µg/mL and αGM-CSF-7331, 1 µg/mL) or control. Results displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 3), one-way ANOVA Tukey test. d RT-qPCR assay of selected genes in PSCs stimulated with conditioned medium from 2 W (PCC–PSC) or 3 W co-cultures (PCC–PSCs–bone marrow-derived MØs) where recombinant murine GM-CSF substitutes for PCCs in the 3 W culture. Results displayed as mean ± SEM (n = 4), one-way ANOVA Tukey test. e Scatter plot of OSM (x-axis) and CSF2 (y-axis) expression levels in PDA patients (TCGA PAAD dataset, n = 179, two-tailed Spearman correlation test). RSEM RNA-seq by expectation-maximisation. Also see Supplementary Fig. 4. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

OSM supports the formation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment

We next sought to determine the role of OSM in vivo and analysed the microenvironment of tumours from PCCs38 orthotopically implanted into syngeneic wildtype or Osm-deficient C57BL/6 mice (Osm−/−) (Fig. 5a). First, we quantified a number of inflammatory cytokines with known tumour-promoting effects in PDA. Tumours from Osm−/− animals exhibited markedly reduced levels of several cytokines, including IL6, CXCL1, GM-CSF and TNFα, highlighting a profound change in the tumour environment (Fig. 5b). Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of the prototypical myCAF marker, αSMA (Acta2), revealed an increase in the αSMApos area in Osm−/− animals compared to wildtype animals (Fig. 5c). However, fibrillar collagens, as determined by picrosirius red staining, was not significantly different between tumours growing in wildtype or Osm−/− animals (Supplementary Fig. 5a). FACS analysis demonstrated a similar levels of CAF infiltration in wildtype and Osm−/− tumours (Fig. 5d right, Supplementary Fig. 5b), suggesting that the altered αSMA staining is due to a phenotypic switch from iCAFs to myCAFs. This is further supported by gene expression analysis, where CAFs isolated from Osm−/− tumours exhibited decreased inflammatory gene expression (e.g. Il6, Mmp3, Has2 and Osmr) but increased myofibroblast gene expression (e.g. Acta2, Itgav and Fn1) (Fig. 5d left). Together, these results demonstrate a role of OSM in establishing the characteristic inflammatory microenvironment of PDA.

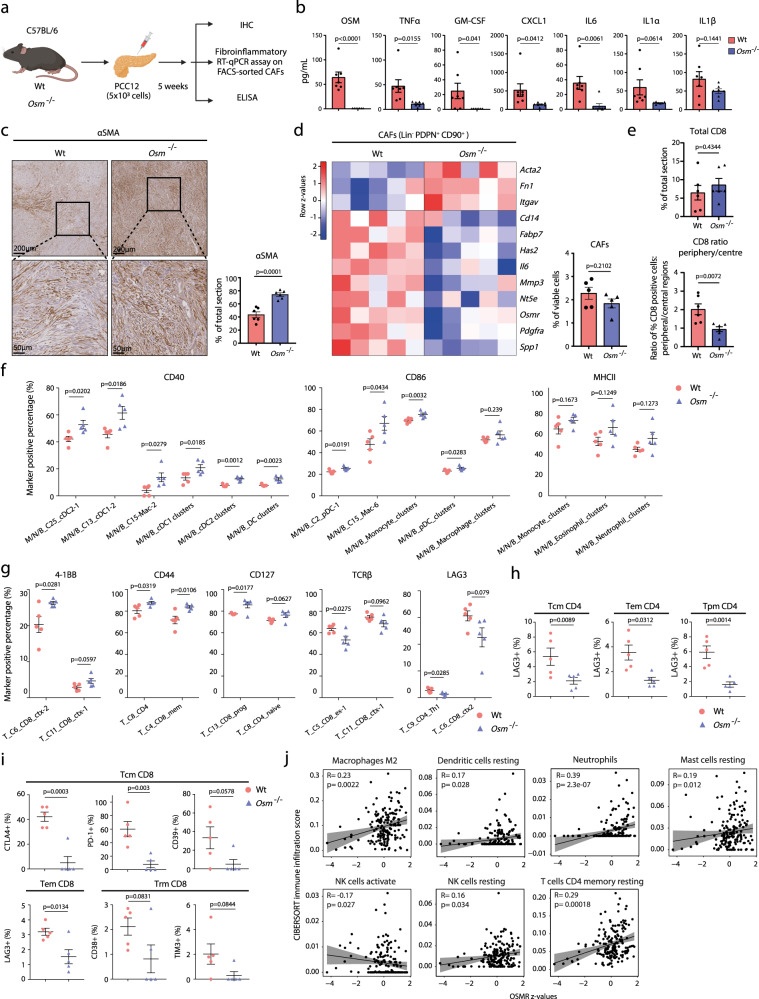

Fig. 5. OSM supports the formation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment.

a Experimental workflow of in vivo experiments. b Protein levels of indicated soluble signals in wildtype (n = 7) and Osm−/− (n = 7) tumours, measured by ELISA. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, two-tailed student t test. c Immunohistochemical analysis of αSMA in wildtype and Osm−/− tumour sections. Left: Representative αSMA staining. Right: Quantification of αSMApos staining of tumour sections of wildtype (n = 6) and Osm−/− (n = 6) animals. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, two-tailed student t test. d RT-qPCR gene expression analysis of FACS-isolated CAFs from wildtype (n = 5) and Osm−/− (n = 5) tumours displayed as a heatmap (left). Number of isolated CAFs shown as bar plot (right). Results displayed as mean ± SEM, two-tailed student t test. e Immunohistochemical analysis of CD8 in wildtype (n = 6) and Osm−/− (n = 6) animals. Upper: Total CD8pos staining. Lower: Ratio of peripheral/central CD8pos staining using the mean CD8pos stain from four representative peripheral regions and four representative central regions per tumour. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, two-tailed student t test. f Mass cytometry analysis quantifying abundance of antigen presenting cells (APCs) expressing co-stimulatory markers in wildtype (n = 5) and Osm−/− (n = 5) tumours. Results displayed as mean ± SEM. Unpaired two-tail student t test. g Mass cytometry analysis of CD45+/CD3+ T cells expressing indicated markers in wildtype (n = 5) and Osm−/− (n = 5) tumours. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, two-tailed student t test. h, i Mass cytometry analysis of memory T cells expressing indicated exhaustion/dysfunction markers in wildtype (n = 5) and Osm−/− (n = 5) tumours. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, two-tailed student t test. Tcm central memory, Tem effector memory, Trm resident memory. j Spearman correlation analysis between infiltration of indicated immune cells (determined by CIBERSORT) and OSMR expression levels in PDA patients from TCGA PanCancer PAAD dataset (n = 179). 95% confidence interval as shaded area. Also see Supplementary Figs. S5 and S6. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We subsequently stained tumours from wildtype and Osm−/− animals with the T cell marker CD8. Although the total CD8 staining was similar between wildtype and Osm−/− tumours, CD8 T cells infiltrated more efficiently into Osm−/− tumours (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 5c). We then immunophenotyped wildtype and Osm−/− tumours21. Single-cell dissociated tumours from wildtype (n = 5) and Osm−/− (n = 5) animals were barcoded, pooled and stained with 40 selected markers to annotate Myeloid, NK and B cells (M/N/B), after which samples were subjected to MC. CD45pos/CD3neg immune cells were manually gated, subjected to self-organising map clustering by flow cytometry (FlowSOM), using 25,000 cells from each wildtype (n = 5) and Osm−/− (n = 5) tumours (Supplementary Fig. 6a), and visualised by uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) (Supplementary Fig. 6b)39,40. This analysis identified 25 populations, including natural killer (NK) cells, B cells and several myeloid populations, such as MØs, monocytes, dendritic cells, neutrophils and eosinophils (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). Intriguingly, we observed an inverse MØ–monocyte ratio between wildtype and Osm−/− tumours (Supplementary Fig. 6c), where Osm−/− tumours contain decreased number of MØs but an increased number of monocytes (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Specifically, the MØ subset (M/N/B_C10), which express markers consistent with an immunosuppressive tumour-associated MØ (TAM) phenotype (CD11bpos; F4/80pos; MHCIIhigh)9, was significantly decreased in Osm−/− tumours (Supplementary Fig. 6a and e). In contrast, the classical monocytes and TAM precursors41,42, M/N/B_C19 (CD11bpos; Ly6Cpos) was more abundant in Osm−/− tumours (Supplementary Fig. 6a, e). This implies that the differentiation of classical monocytes into immunosuppressive TAMs is impaired in Osm−/− tumours. Moreover, antigen presenting cells (APCs) from Osm−/− tumours expressed higher levels of co-stimulatory molecules such as CD40 and CD86 (Fig. 5f). This shows that immune cells in Osm−/− tumours exhibit characteristics associated with improved antigen presentation, such as elevated expression of co-stimulatory markers, which may lead to more effective T cell activation.

To determine whether Osm−/− tumours also exhibit altered composition and function of CD45pos/CD3pos T cells, we immunophenotyped the T cell infiltrate of the same tumours by MC21. FlowSOM clustering of 182,800 T cells from wildtype (n = 5) and Osm−/− tumours (n = 5) identified 20 populations including CD8pos (progenitor, cytotoxic, exhausted and memory), CD4pos (naïve, Th1, Th2, memory and Treg) and γδ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 6f, g). Importantly, although the abundance of major T cell populations remained unchanged between wildtype and Osm−/− tumours (Supplementary Fig. 6h), we observed a notable shift in the expression of markers consistent with increased T cell activation in Osm−/− tumours (Fig. 5g). Specifically, T cell populations from Osm−/− tumours expressed higher levels of the co-stimulatory molecule 4-1BB (T_C6), activation markers such as CD44 (T_C8 and T_C4) and CD127 (T_C13), alongside decreased levels of TCRβ (T_C5) (Fig. 5g), consistent with improved T cell activation43,44. Further, the CD4pos Th1 population (T_C9) displayed reduced expression of exhaustion/dysfunctional marker, LAG3 (Fig. 5g) suggesting that T cell populations in Osm−/− tumours remain more functional and less exhausted.

CD44 and CD127, which demark T memory cells45, were increased across several populations of CD8pos and CD4pos T cells in Osm−/− tumours (Fig. 5g). We therefore further characterised memory T cell populations in these animals. Central memory (Tcm) and effector memory (Tem) CD4pos and CD8pos T cells displayed reduced levels of T cell exhaustion and inhibitory markers such as LAG3 (Fig. 5h, i), CTLA4 and PD-1 (Fig. 5i), consistent with improved function of memory CD4pos and CD8pos T cell populations in Osm−/− tumours (Fig. 5h, i and Supplementary Fig. 6i). Analysis of immune infiltrates in human PDA patients from TCGA PanCancer46 by CIBERSORT47 was consistent with the MC analysis (Fig. 5j). Specifically, we observed that OSMR expression levels, as a marker of iCAFs, correlated with infiltration of M2 MØs and neutrophils and resting or inactivated dendritic cells, mast cells, NK cells and CD4pos memory T cells in patients with PDA (Fig. 5j). In contrast, infiltration of activated NK cells was negatively correlated with patient OSMR expression (Fig. 5j). Together, this emphasises the relationship between OSMR expression and the establishment of an immunosuppressive microenvironment in patients with PDA, and underscores a functional role of heterocellular OSM–OSMR signalling in mediating an immunosuppressive, tumour-promoting environment.

PCC–PSC–MØ interactions reshape tumour cell signalling

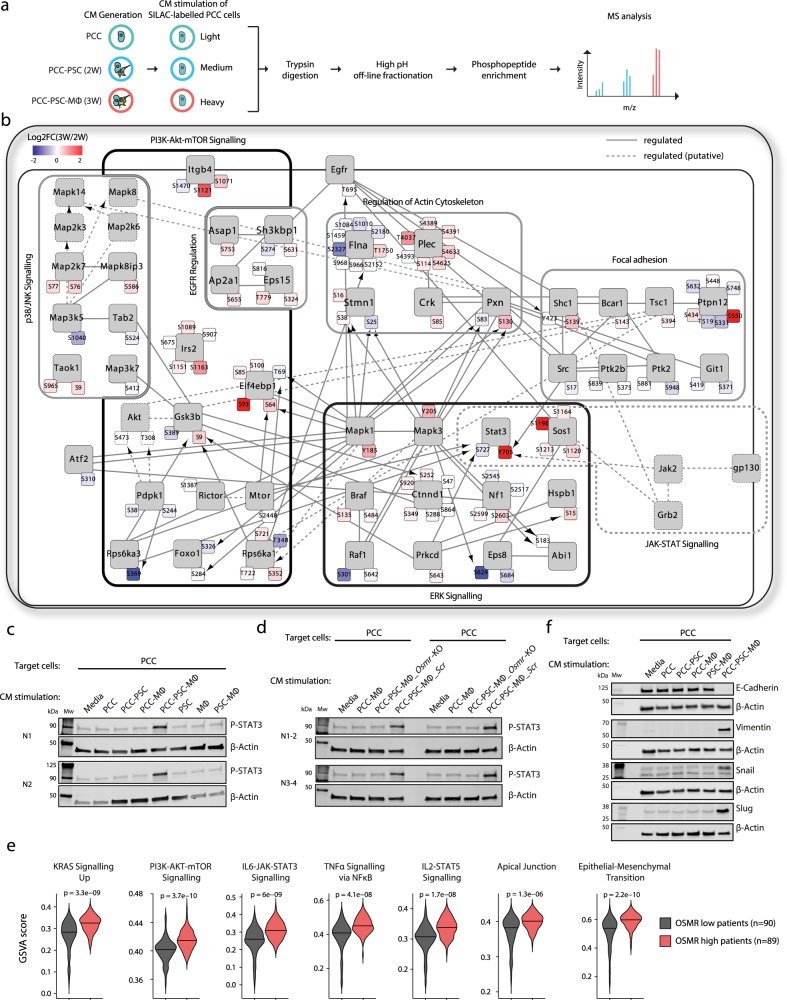

Given the extensive shift in the cellular signalling milieu between PCC–PSC and PCC–PSC–MØ co-cultures (Fig. 2a), we hypothesised that tumour cell signalling and function is differentially regulated under these two conditions. We, therefore, undertook a quantitative phosphoproteomics analysis of stroma-regulated tumour cell signalling, treating tumour cells with conditioned medium from mono-cultured PCC and 2 W PCC–PSC or 3 W PCC–PSC–MØ co-cultures (Fig. 6a). In agreement with previous observations, tumour–stroma interactions rewired tumour cell signalling to engage additional signalling pathways beyond the tumour cell-autonomous signalling state (Supplementary Fig. 7a)14,48 with additional differences between 2 and 3 W co-culture conditions. Specifically, we quantified 2523 phosphorylation sites that were differentially engaged in tumour cells treated with co-culture conditioned medium, of which, 3 W signals specifically regulated 508 unique tumour cell phosphosites, and 2 W signals specifically regulated 433 tumour cell phosphosites (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Kinases and pathways with known function in PDA development, such as MEK-MAPK, JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT signalling, were more engaged in tumour cells treated with 3 W conditioned medium compared to 2 W, including the phosphorylation of the activation sites of MAPK1 [Y185], MAPK3 [Y205] and STAT3 [Y705] as well as AKT substrate phosphorylation, such as GSK-3β [S9] and EIF4EBP1 (4E-BP1) [S64] (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 7b). Indeed, enrichment analysis of phosphorylation motifs revealed that 3W-regulated tumour cell signalling was predominantly regulated by the MAPK- and PKA/AKT-signalling pathways (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Concordantly, a kinase-substrate directed phospho-network analysis further highlighted MAPK1/3 and AKT as central kinases regulating PCC–PSC–MØ-induced tumour cell signalling (Fig. 6b). For example, PCC–PSC–MØ-activated MAPK1/3 can phosphorylate a number of downstream phosphoproteins, such as RPS6KA1 (RSK1), in turn phosphorylating GSK-3β, and 4E-BP1, which are also regulated by AKT49,50. Notably, both SHC1-engaged SRC and gp130-activated JAK2 signals increased the phosphorylation of STAT3 [Y705] (Fig. 6b), a critical step in pancreatic cancer progression36,51. Furthermore, PCC-PSC-MØ signalling uniquely results in phosphorylation of p38 and JNK pathway components including TAOK1 and MAP2K7 (MKK7) (Fig. 6b, Supplementary Fig. 7b), implicated in proliferation and invasion in multiple cancers52,53. To corroborate the global phosphoproteomics analysis we undertook a targeted phosphorylation analysis, which confirmed that PCC–PSC–MØ signals accentuate STAT3, MAPK1/3, AKT, p38 and JNK activation beyond mono- and 2 W co-culture conditions (Supplementary Fig. 7d). In addition, immunoblotting for phosphorylated STAT3 [Y705] in PCCs treated with conditioned medium across all mono- and co-culture conditions revealed a specific increase only with PCC–PSC–MØ conditioned medium (Fig. 6c). This effect is unlikely to be a direct effect of OSM on PCCs as recombinant OSM only engaged STAT3 phosphorylation in PSCs (Supplementary Fig. 7e). Furthermore, 3 W co-culture induced STAT3 phosphorylation in PCCs was dependent on OSMR expression in PSCs where CRISPR–Cas9-mediated knockout of Osmr in PSCs ablate 3 W co-culture induced STAT3 phosphorylation in PCCs (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 7f). These data underscore the importance of interactions between tumour cells, fibroblasts and macrophages in shaping tumour cell signalling.

Fig. 6. PCC–PSC–MØ interactions reshape tumour cell signalling.

a Experimental workflow outlining SILAC-based phosphoproteomics analysis of stroma-regulated tumour cell signalling. “Light” (L), “Medium” (M) and “Heavy” (H) labelled PCCs were stimulated (5 min) with PCC or PCC–PSC or PCC–PSC–MØ conditioned medium, respectively (n = 5). Pooled L/M/H peptides (in a 1:1:1 ratio) were fractionated, phospho-peptides enriched and analysed by LC–MS/MS. b PhosphoPath phospho-network analysis summarising PCC–PSC–MØ-regulated tumour cell signalling, relative to PCC–PSC-regulated signals (p < 0.05, Fisher exact test with Benjamini–Hochberg multiple testing correction). Arrows indicate kinase-substrate relationships and blunt-ended edges indicate protein–protein interactions. c Western blots of phosho-STAT3 levels in PCCs treated with conditioned medium from 1, 2 or 3 W co-cultures (n = 2). d Western blots of phosho-STAT3 levels in PCCs treated with conditioned medium from 2 W or 3 W co-cultures containing either Osmr-KO or Scr-PSCs (n = 4). e Single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) of PDA patients from TCGA PanCancer PAAD dataset (n = 179). Patients were stratified into OSMRhigh (n = 89) and OSMRlow (n = 90) groups. f Representative western blot of EMT markers in PCCs treated with conditioned medium from 1, 2, or 3 W co-cultures; E-cadherin, Vimentin, SNAIL, and SLUG (n = 3). Also see Supplementary Fig. 7. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Single sample GSEA (ssGSEA) of human PDA tumours adjusted for tumour purity (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. 7g), confirmed differential signalling pathway engagement where OSMRlhigh tumours display increased KRAS pathway activity, PI3K-AKT-mTOR and IL6-JAK-STAT3 signalling. Moreover, consistent with the observation that PCCs in 3 W co-culture regulated cell–cell adhesion, motility and actin cytoskeleton (Supplementary Fig. 7h), ssGSEA also identified an enrichment of EMT signature genes in OSMRlhigh tumours (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. 7i). To further validate this observation, we analysed PCCs treated with conditioned medium from 2 and 3 W co-cultures, which revealed a decrease in E-Cadherin levels concomitant with an increase in VIM and SNAIL/SLUG specifically in PCCs treated with conditioned medium from 3W-cultures (Fig. 6f, and Supplementary 7j). Thus, interactions between tumour cells, fibroblasts and MØs, through OSM–OSMR signalling, induce an inflammatory fibroblast phenotype, which in turn engage migratory and mesenchymal tumour cell signalling pathways.

OSM drives tumour growth and metastasis in vivo

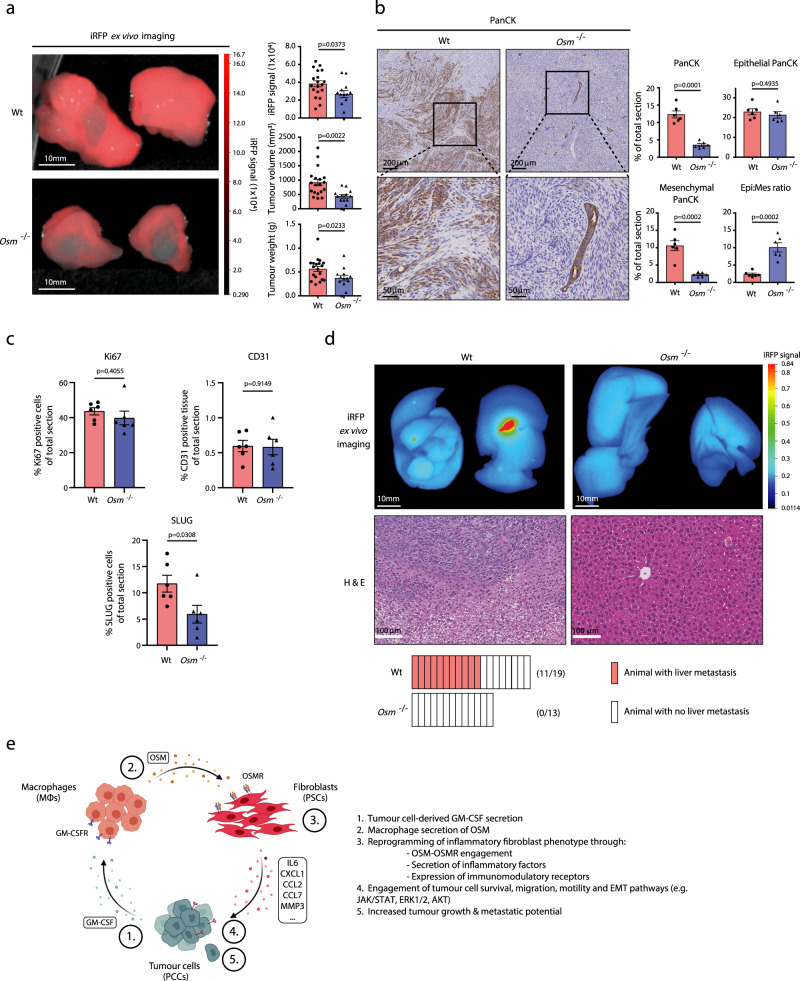

Lastly, we sought to determine the pathobiological role of OSM–OSMR signalling on tumour cell function in vivo. We analysed tumour growth and metastasis in the wildtype and Osm−/− orthotopic mouse model of PDA used in Fig. 5. Due to the desmoplastic reaction of pancreatic tumours, we transduced PCCs with infra-red RFP (iRFP) before implantation, thereby enabling quantitative analysis of tumour cell-specific growth54. As expected, tumour cells injected into the pancreas of wildtype animals efficiently established primary tumours, as quantified by iRFP signal intensity, primary tumour volume and tumour weight (Fig. 7a). In contrast, injection of the same cells into Osm−/− mice results in a significantly reduced tumour burden, shown by iRFP intensity, tumour volume and tumour weight (Fig. 7a), demonstrating a systemic role for OSM in primary tumour growth. IHC analysis confirms a reduced PanCKpos tissue area in Osm−/− tumours, corresponding to restrained tumour growth (Fig. 7b). No significant differences were observed in staining for the proliferation marker Ki67, however cleaved caspase 3 levels were increased in tumours from wild-type animals (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Fig. 8a, e). Quantitative morphology analysis of PanCKpos tumour cells highlights a morphological shift from a mixed mesenchymal and epithelial phenotype in wildtype animals towards an epithelial-dominated phenotype in the Osm−/− animals (Fig. 7b). Consistently, IHC staining for the EMT marker SLUG revealed decreased levels in tumours from Osm−/− animals but a non-significant difference in SNAIL levels (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Fig. 8c, d), supportive of an Osm-dependent regulation of tumour cell EMT.

Fig. 7. OSM drives tumour growth and metastasis in vivo.

a Left: Representative iRFP imaging of resected pancreatic tumours from orthotopically transplanted immune-competent wildtype (Wt) (n = 19) and Osm−/− (n = 13) mice. Right: Quantification of iRFP signal intensity, tumour volume and tumour weight. Results displayed as mean ± SEM (Wt, n = 19 and Osm−/− n = 13), two-tailed student t test. b Left: Representative Pan-Cytokeratin (PanCK) staining of wildtype and Osm−/− tumour sections. Right: Quantification of total PanCKpos staining, mesenchymal PanCKpos staining, and epithelial PanCKpos staining following morphology analysis, and the epithelial–mesenchymal PanCKpos ratio in tumour sections from wildtype (n = 6) and Osm−/− (n = 6) mice. A shift of PanCKpos cells from a mixed mesenchymal and epithelial morphology in wildtype tumours to a more epithelial-dominant morphology in Osm−/− animals. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, two-tailed student t test. c Quantification of total Ki67,pos CD31pos, and SLUGpos immunohistochemical staining of tumour sections from wildtype (n = 6) and Osm−/− (n = 6) mice. Results displayed as mean ± SEM, two-tailed student t test. d Upper: Representative iRFP in vivo imaging (top) and haematoxylin and eosin staining (bottom) of resected livers from wildtype and Osm−/− mice. Lower: Quantification of iRFPpos liver metastasis incidents in wildtype (n = 11/19) and Osm−/− (n = 0/13) animals. e Model outlining heterocellular OSM–OSMR signalling between pancreatic cancer cells, fibroblasts and macrophages. Pancreatic cancer cell secretion of GM-CSF induces macrophage secretion of OSM, which reprograms fibroblasts to an inflammatory phenotype, in turn accentuating tumour growth and metastasis. Also see Supplementary Fig. 8. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Liver is the most common metastatic site for PDA, and metastasis is the major contributor of cancer mortality55. Due to the observed difference in EMT signature between 2 and 3 W co-culture conditions in vitro and OSMRhigh and OSMRlow human PDA tumours (Fig. 6e, f), the morphological shift of tumour cells from a more migratory and mesenchymal to an epithelial-dominated phenotype (Fig. 7b), together with reduced levels of pro-metastatic inflammatory signals, such as IL6 (Fig. 5b), we hypothesised that loss of Osm would also be associated with reduced metastasis. Strikingly, whereas more than 50% of wild-type animals develops iRFP+ liver metastasis, none of the Osm−/− animals shows any signs of liver metastasis (Fig. 7d) demonstrating a role of OSM in regulating metastatic spread. Notably, staining for CD31 did not reveal any overt differences in the blood vessel abundance between tumours in wildtype or Osm−/− animals (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Fig. 8b). Taken together, these findings highlight that OSM is a key MØ-derived signal in establishing an inflammatory microenvironment promoting tumour growth and metastasis.

Discussion

Tumours are evolving multicellular ecosystems. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is characterised by an abundant desmoplastic reaction, where CAFs have emerged as coordinators of both tumour-promoting and -restricting functions of the microenvironment2,22. Single cell RNA expression and de novo inference analyses have been instrumental in annotating transcriptionally distinct CAF subsets21,24,26,27,33, however, further characterisation of individual populations and their heterocellular interdependencies is essential in elucidating pathological functions of CAFs. CAFs are highly plastic and readily adopt two interchangeable transcriptional subtypes, where myofibroblastic CAFs (myCAFs) are characterised by high contractility and expression of αSMA (ACTA2), whereas inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs) produce pro-tumourigenic cytokines such as IL6, CXCL1 and CCL227,29,30. Whereas genetic and pharmacologic ablation of CAFs, results in rapid progression and metastatic spread19,20, functional CAF reprogramming induce a microenvironment favourable to chemotherapy and ICI11,16, highlighting functional opposing roles of CAFs in the microenvironment. Tumour cells have been described to directly modulate CAF function though secretion of SHH, LIF, TGFβ and IL114,17,29,30, however, it is less clear whether other cell populations in the TME, beyond the tumour cells, can regulate CAF function.

Here, we describe a role for OSM and its cognate receptor (OSMR) in regulating pancreatic fibroblasts and the inflammatory TME (Fig. 7e). In PDA, Osmr is expressed in mesenchymal cells such as CAFs, endothelial cells and pericytes, and Osm is expressed in immune cells such as MØs, myeloid cells, dendritic cells and neutrophils. Notably, Osmrhigh CAFs express higher levels of inflammatory signals such as Il6, Ccl7, Ccl2 and Cxcl1 in animal models of PDA, OSMR is expressed at increased levels in human PDA and is associated with a tumour-promoting immune infiltrate and worse patient outcome. In vitro, co-cultures of cancer cells, MØs and fibroblasts as well as recombinant OSM increase Osmr expression and production of inflammatory signals in fibroblasts. However, while the presented data indicate a role of heterocellular OSM–OSMR signalling as a regulator of inflammatory fibroblasts, future studies will be critical to establish whether OSM–OSMR signalling directly involving tumour cells and other stromal cell populations play additional roles in PDA.

Reconstituted in vitro co-cultures of tumour cells, stellate cells and MØs activate tumour cell PI3K-AKT-mTOR, MEK-MAPK and EMT pathways. This is consistent with patient data, where high levels of OSMR expression is associated with enrichment of pro-tumourigenic pathways including KRAS signalling, IL-JAK-STAT signalling, PI3K-mTOR signalling and EMT. Tumours from orthotopically implanted PCCs are smaller and appear more epithelial in Osm deficient (Osm−/−) animals. Moreover, no overt metastasis is observed in Osm−/− animals, but further studies are needed to establish a mechanistic link between OSM signalling and metastasis—in particular given an established relationship between primary tumour size and metastatic dissemination. In other solid cancers such as breast cancer and squamous cell carcinoma, OSMR is directly expressed by the tumour cells and regulates cancer stem cell properties, EMT and metastasis56–58. Importantly, while the analysed scRNAseq data did not identify OSMR expression in epithelial cells, we were unable to apply a consistent cell-type annotation across other available data sets to confirm whether OSMR was expressed in epithelial cells, thus we cannot conclusively exclude that distinct epithelial populations may express OSMR. In situ hybridisation of human PDA demonstrated that OSMR was expressed both in stromal and epithelial cells, however response to recombinant OSM was restricted to pancreatic stellate in vitro. Moreover, OSMR expression in stellate cells is required for co-culture dependent activation of phospho-STAT3 signalling in tumour cells. Thus, although future studies are required to fully establish whether OSM may directly regulate tumour cell function in human PDA, the data presented here demonstrates that fibroblast reprogramming and rewiring of tumour cell signalling can regulate tumour cell signalling in a heterocellular manner.

OSM signalling has been associated with pro-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects in cardiac fibroblasts59 and in inflammatory bowel disease where OSM–OSMR signalling and stromal reprogramming drives colitis and mediates resistance to anti-TNFα treatment60. Moreover, a correlation between inflammatory fibroblasts and T cell exhaustion and dysfunction has been found in a de novo study of triple negative breast cancer61. Loss of OSM function in vivo is associated with a decrease in the level of several inflammatory signals with known pro-tumorigenic function, a shift in the myeloid to MØ infiltration of orthotopic tumours, as well as improved function of APCs and T cells. This suggests that OSM signalling may act to coordinate the inflammatory microenvironment through functional fibroblast reprogramming, and that the role may be conserved across multiple tissues and inflammatory diseases.

Together, the data presented here demonstrates a role for heterocellular OSM–OSMR signalling in establishing a pro-tumourigenic environment in PDA and highlights OSM–OSMR signalling as a putative therapeutic target in PDA.

Methods

Mice and in vivo experiments

To establish an immune-competent mouse line with whole-body depletion of Osm (Osm−/−), the cryopreserved sperm from a male C57BL/6 Osm−/− mouse (MMRRC_048921-UCD) was purchased from The KOMP Repository (University of California, Davis, US) and fertilised in vitro with eggs from a female wildtype donor C57BL/6 mouse (purchased from Envigo). The fertilised embryos were implanted into pseudo-pregnant surrogate females. The litters were crossed with age-matched wildtype C57BL/6 mice to produce heterozygotes, which were then crossed further to produce wildtype and Osm−/− breeders. All animals were genotyped and maintained under pathogen-free and ventilated cages with environment enrichment in the Biological Resources Unit at the CRUK Manchester Institute (CRUK MI), and allowed free access to irradiated food and autoclaved water ad libitum in a 12 h light/dark cycle, with room temperature at 21 ± 2 °C and humidity between 45 and 65%. All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body (AWERB) of the CRUK MI and undertaken under Home Office regulations under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and under Project Licence PPL 70/8745. Experiments are reported in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines. A 8- to 12-week-old male and female mice were enroled in approximately equal proportions for all animal experiments.

Patient samples

Research samples were obtained from the Manchester Cancer Research Centre (MCRC) Biobank with informed patient consent obtained prior to sample collection. The MCRC Biobank (ethics code: 18/NW/0092) is licensed by the Human Tissue Authority (license number: 30004) and is ethically approved as a research tissue bank by the South Manchester Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 07/H1003/161 + 5). The role of the MCRC Biobank is to distribute samples. For more information see [www.mcrc.manchester.ac.uk/Biobank/Ethics-and-Licensing].

Cell culture and cell lines

Mouse PDA cell lines (PCC, PCC1–PCC12) and PSCs used in this study have been previously described14,38,62. Mouse MØ cell line is from ATCC (ATCC TIB-71) and was used for all experiments except where bone marrow-derived MØs are specifically stated. All cells were cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in normal culture media (NCM), consisting of high glucose and pyruvate Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (ThermoFisher, 41966029) supplemented with 10% v/v heat inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS) (ThermoFisher, 10500064) and 1% v/v Hyclone Antibiotic/Antimycotic (Cytiva, SV30079.01). PCC (iKras mouse PDA cancer cell line) were cultured in the presence of 1 µg/mL doxycycline (Sigma, D9891). All cell lines, except PSC, were cultured for no more than ten passages to minimise culture-induced phenotypic drift. PSC cells were cultured for no more than five passages and CRISPR edited PSCs no more than nine passages. All cells used in experiments were routinely tested free of Mycoplasma. In addition, cells used in vivo were further tested for Mouse Hepatitis Virus (MHV) and Mycoplasma 5 days prior to the experiment. To ensure cell surface proteins engaged in signalling are preserved during in vitro experiments, cells were detached using Accutase Solution (Sigma, A6964). All in vitro experiments were performed in Minimal Media (DMEM with 0.5% v/v dialysed FBS (dFBS) (ThermoFisher, 26400044)) to minimise serum-induced signalling. All cell lines used and origin are listed in Supplementary Table 8.

Conditioned medium generation

To generate conditioned medium of mono- and co-cultures of PCC, PSC and MØ, a total of 2.5 × 106 or 7.5 × 106 cells was plated in either a T25 or T75 flask, respectively, and cultured in Minimal Media for 72 h. Conditioned medium from these mono- and co-cultures were passed through 0.22 µm syringe filters (VWR), and were either used fresh for stimulation experiments or stored at −80 °C until used for ELISA/LUMINEX experiments.

Stimulation of target cells with conditioned medium or recombinant protein or inhibitors

Target cells were plated and serum starved in Minimal Media 18 h prior to stimulation. On the day of stimulation, media was aspirated and the target cells were stimulated with fresh Minimal Media containing either conditioned media in a 1:1 ratio (v/v) or indicated concentrations of recombinant protein or inhibitors, and cultured for 72 h. A list of recombinant proteins, inhibitors, and neutralising antibodies can be found in Supplementary Table 9.

Bone marrow-derived MØ generation

Bone marrow-derived MØs (BMDMs) were generated as follows. Femurs and tibias were harvested from 8- to 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice (Envigo). Bones were washed in 70% ethanol, followed by two subsequent washes in ice-cold PBS. Epiphyses of the femurs and tibias were cut off with a disposable scalpel, and bone marrow was flushed out with 10 mL NCM using a 25 gauge needle, and was filtered through a 70 µm cell strainer. Bone marrow cells were washed and cultured in BMDM media (NCM supplemented with 20 ng/mL M-CSF) for 3 days. Media was replaced after 3 days with fresh BMDM media and cells were further cultured for 3 additional days. The resulting cells are bone-marrow-derived MØs and used for experiments.

LUMINEX assay

Custom magnetic beads (ThermoFisher) were used to measure the concentrations of a panel of murine CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL7, CCL11, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL5, CXCL10, IL-1β, IL-3, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-18, IL-22, IL-23, IL-27, IL-28, IL-31, M-CSF, GM-CSF, G-CSF, LIF, VEGF, RANKL and TNFα in conditioned media collected from mono- and co-cultures of PCC, PSC and MØ on MAGPIX (ThermoFisher) as per manufacturer’s protocol.

ELISA

Concentrations of OSM (DY495-05), GM-CSF (DY415-05), IL6 (DY406-05), IL1α (DY400-05), IL1β (DY401-05), TNFα (DY410-05), CXCL1 (DY453-05) (all from R & D Systems) in samples were measured using ELISA DuoSet kits as per manufacturer’s instructions. For tumour samples, ELISA was performed as previously described63. In brief, tumours were homogenised in PBS containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma, P8340) and PMSF (1 mM). Tumour homogenates were then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C and supernatants were stored at −80 °C until required for ELISA assay. Following quantification of total protein concentration in each tumour sample using Pierce BCA Assay Kit (ThermoFisher, 23225), tumour sample containing 100 mg of total protein was then used for ELISA assay.

Lentivirus transduction and EGFP-, mCherry-, TagBFP-, iRFP-labelling of cell lines

To generate EGFP-, mCherry- and TagBFP-expressing cell lines, a second-generation lentiviral system was used. 293FT cells (ThermoFisher) were plated in a 10 cm culture dish and cultured overnight in NCM. Next day, 4 µg of SFFV-EGFP or SFFV-mCherry or SFFV-TagBFP transfer plasmid, 2 µg of pCMV delta R8.2 packaging plasmid (Addgene, 12263), 1 µg pMD2.G envelope plasmid (Addgene, 12259) and 21 µL Polyethylenimine (PEI) (Sigma, 764647) were combined in 3:1 (PEI:plasmids) v/v ratio and mixed in 1 mL of serum-free DMEM and incubated at RT for 30 min. Plasmid/PEI mixture was added directly to 293FT cells, and incubated overnight. Virus-containing supernatant was collected and stored at 4 °C and replaced with fresh NCM and cells were cultured for another 24 h. Virus aliquots from both 24 and 48 h collections were combined, passed through a 0.22 µm syringe filter, and stored at −80 °C until required. Target cells were plated at 50% confluence and cultured overnight in NCM. Target cells were incubated in neat virus-containing conditioned media, supplemented with Polybrene (8 µg/mL final concentration) for 24 h. Media was replaced with fresh NCM after several washes with PBS. Cells were cultured until confluence and FACS-isolated for positivity for fluorescent protein expression. Transduced cells were further isolated on FACSAria III Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences, BD FACSDiva Software) to ensure high expression of fluorescent proteins. For iRFP-labelling of PCC12 cell line, lentiviral particles expressing iRFP were generated in 293FT cells using the PGK_iRFP720-WPRE transfer, pMD2.G envelope and psPAX2 packaging plasmids by following the steps shown above. PCC12 cells were labelled with iRFP-expressing viral aliquots as shown above. High iRFP-expressing PCC12 cells were isolated by FACSAria III Cell Sorter. PCC12-iRFP cells were passaged once more and multiple vials were cryopreserved until required for in vivo experiment.

Biomark HD multiplex qPCR

Assay primers and probes were designed using the Roche Universal Probe Library Assay Design Centre Tool (https://lifescience.roche.com/en_gb/brands/universal-probe-library.html). Refer to Supplementary Table 7 for a full list of primer sequences and respective TaqMan probe numbers of genes used in this study. Where possible, primer pairs spanning two exons were selected to avoid amplification of genomic DNA. cDNA was synthesised from 500 ng of RNA of each sample using Multiscribe RT enzyme (ThermoFisher) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed in a cycle of 25 °C for 10 min, 37 °C for 60 min, 95 °C for 5 min and 4 °C indefinitely until stored at −20 °C. A pre-amplification of the genes of interest was performed on cDNA of each sample in a reaction mixture of 1× TaqMan Pre-Amp Master Mix and a pool of assay-specific primers (5 nM) by temperature cycling at 95 °C for 10 min for 1 cycle, 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 4 min for 14 cycles and resting at 4 °C and stored at −20 °C. Assay Mix was made using 8 µM of each primer pair and 1 µM of the appropriate hydrolysis probe in 1× Assay Loading Reagent (Fluidigm, 85000736). Sample Mix was made by diluting the pre-amplified cDNA in TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, 4304437) and GE Sample Loading Reagent (Fluidigm, 85000746) in a 1:1 v/v ratio. Samples combined with Sample Mix and Assay Mix were then carefully loaded onto a 96 × 96 Dynamic Array Chip (Fluidigm, BMK-M-96.96) and analysed according to manufacturer’s instructions using standard settings with auto-exposure and ROX as passive reference dye. Raw RT-qPCR data was analysed using the BioMark Real-Time PCR Analysis Software (Fluidigm). Assay dependent thresholds were used to calculate cycle threshold (Ct) values and relative expression calculated as: relative expression = 2−ΔCt where ΔCt = (Ct value of Gene A) − (Geometric mean of Ct values for housekeeping genes: Gapdh, Tubb4a, Ppia, Tbp).

Immunoblotting

Cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and lysed for 1 min in Protein Lysis Cocktail (PLC) buffer [50 mM Trizma base (Sigma), 150 mM NaCl (Sigma 71376), 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Sigma), 1 mM EDTA (Sigma), 10 mM Sodium pyrophosphate tetrabasic (Sigma), 10% v/v Glycerol (Sigma), 1% v/v Triton X-100 (Sigma)], supplemented with 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Sigma), Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (1:500, Sigma) and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail 3 (1:100, Sigma). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (16,000g, 10 min, 4 °C), quantified by BCA Protein Assay (Pierce, Thermo Scientific), and boiled in 6× Laemmli Loading Buffer [415 mM SDS (Sigma), 895 µM Bromophenol blue (Sigma), 50% v/v Glycerol (Sigma), 60 mM Trizma base (Sigma) 600 mM Dithiothreitol (Sigma), dH2O to 10 mL], for 5 min at 95 °C. Lysates were loaded at 10 µg into pre-cast gels, 4–15%, 15-well, 15 µL (mini-PROTEAN, BIO-RAD), in 1× TGS buffer, and transferred onto 0.2 µm nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham) for 1 h 30, in 1× TGS, 20% MeOH, dH2O transfer buffer. Membranes were blocked for 1 h in ROTI-Block (Carl-Roth), incubated with primary antibodies (overnight, 4 °C) washed in PBST, and incubated with secondary antibodies (1 h, RT). Membranes were imaged using Odyssey CLx Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) for infra-red duplexing of fluorescent signals and quantified using Image Studio Lite software (LI-COR, version 5.2.5). A list of antibodies used and uncropped western blots can be found in the Supplementary Information file (Supplementary Table 5, and Supplementary Figs. 9–12) and the Source Data file.

CRISPR–Cas9-guided Osmr knockout of fibroblasts

Osmr knockout of fibroblasts was achieved by using a multi-gRNA approach (Synthego), where PSC cells were transfected with recombinant Cas9 and three individual gRNAs against Osmr, which were designed on https://www.synthego.com/. Specifically, prior to transfection, PSC cells were washed in PBS, detached using Accutase Solution, and washed twice in PBS. Subsequently, 2.5 × 105 cells were resuspended in 5 µl of P3 Primary Cell NucleofectorTM Solution (Lonza). In parallel, Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes were prepared by combining 4 μL of 30 μM of multi-gRNA mix (Synthego) and 1 μL of 20 μM Alt-R® S.p. HiFi Cas9 Nuclease V3 (Integrated DNA Technologies) in 10 μL of Primary Cell P3 Nucleofector solution (Lonza) and incubated at RT for 20 min. Finally, the cell suspension, RNP mixture and 0.8 μL of 100 µM Electroporation Enhancer Solution (Integrated DNA Technologies) were combined together and mixed gently by pipetting. The RNP–cell mixture was transferred into the Nucleocuvette Strip (Lonza) and transfected using the 4D-Nucleofector Core Unit (Lonza) with the pulse “CM-137”. Cells were then transferred into a T75 flask filled with pre-warmed NCM and cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Double-strand cleavage of Osmr gene was confirmed by gel electrophoresis of PCR product using primers flanking the gene-edited region. Osmr knockout was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. All the reagents used for nucleofection were from P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit S (Lonza, V4XP-3032). Target sequences of gRNAs and Sanger sequencing confirmation are included in the Supplementary Information file (Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Fig. 13).

Bulk RNA sequencing of fibroblasts from mono- and co-cultures

Cell Culture

mCherry-labelled fibroblasts (PSC-mCherry) were mono- (n = 4) and co-cultured with PCC-EGFP (n = 4) or PCC-EGFP and MØ-TagBFP (n = 4) in T75 flasks containing Minimal Medium with a total cell number of 7.5 × 106 cells per condition. After 72 h of culture, cells were gently washed in PBS, detached using Accutase Solution and resuspended in FACS Buffer (1% FBS in PBS) after filtered through 70 µm cell strainer. PSC-mCherry cells from each culture condition were sorted based on mCherry positivity using FACSAria III Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences), and RNA was immediately extracted using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, 74134).

RNA sequencing library preparation and analysis

Indexed PolyA libraries were prepared using the QuantSeq 3′ mRNA-Seq Library Prep Kit FWD for Illumina (Lexogen, 015.96). An input of 100 ng of total RNA was used with 14 cycles of amplification. Libraries were then quantified by qPCR using a Kapa Library Quantification Kit for Illumina (Roche, 07960336001). Single read 75 base-pair (bp) sequencing was performed by clustering 1.9 pM of the equimolar pooled libraries on a NextSeq 500 sequencer (Illumina Inc.). RNA-Seq reads were quality checked using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.bbsrc.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) software and trimming of bases was performed. Raw sequencing reads were then aligned to the mouse genome assembly (GRCm38.75) in single-end mode using the STAR 2.7 RNAseq aligner64 with default parameters. Mapped data were converted to normalised read counts (expression) using featureCounts65 and the Ensembl GTF annotation (Mus_musculus.GRCm38.75.gtf). Differential expression (DE) was evaluated using the DESeq2 Bioconductor package65. Genes with relative expression of Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted p-value < 0.05, and Log2FoldChange > 1 were considered to be differentially expressed.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

GSEA was performed using the GSEA software (V4.1.0) from the Broad Institute (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp) and run using default settings, permutation type and gene set66.

Orthotopic transplantation

KPC cells (PCC12, 8513) were prepared for orthotopic injection as follows. Twenty-four hour prior to the transplantation, cells were plated at 70% confluence in normal culture medium (NCM). On the day of injection, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and dislodged using Accutase Solution. After spinning down at 300 × g, 4 °C for 5 min, cells were washed two more times with ice-cold PBS before cell counting. Cell suspension was prepared at 5000 cells in 20 µL ice-cold Matrigel, and was kept on ice until injection. Mice were anaesthetised using isoflurane and subcutaneous injection of Buprenophine (Royal Veterinary College, RVC) (20 µL/10 g body weight, Buprecare) and Carprofen (RVC) (60 µL/30 g body weight, Rimadyl). Prior to surgery, fur was clipped, the exposed skin was cleaned using Chlorhexidine surgical scrub, and the animal was draped for surgery to maintain aseptic conditions. A median laparotomy was performed with a 5 mm incision made to the left abdominal flank. Mouse pancreas was carefully externalised using surgical forceps, and 20 µL of Matrigel cell suspension was injected into the pancreatic tail using an insulin syringe and needle (Braun Omnican 50, VWR). To prevent any leakage at the injection site, the needle was slowly withdrawn and the pancreas was left for 30 s. A successful injection without any leakage was confirmed by a formation of a bubble at the injection site. Muscle and skin layers were sutured with absorbable Vicryl suture (Ethicon). Prior to suturing the skin, Bupivacaine Hydrochloride (1:20 in sterile saline, Marcain Polyamp 0.5%) were administered locally to aid local anaesthesia, and animals were injected subcutaneously with 0.2 mL sterile saline. Mice were weighed twice a week, and were closely monitored for exhibiting any moderate signs of PDA such as swollen abdomen, impaired body conditioning (e.g. reduced mobility), hyperventilation and loss of body weight by more than 10%. Five weeks after the transplantation, mice were euthanised by cervical dislocation and tissues were collected accordingly for further analyses. Resected tumours were weighed, and tumour volumes were measured by external calliper using the formula, tumour volume = ½(length × width2).

iRFP in vivo imaging on LI-COR Pearl imager

Prior to imaging in vivo, mice were sacrificed via cervical dislocation and pancreatic tumours and livers were resected. Tissues were imaged for iRFP excitation (emission wavelength of 685 nm, 700 channel) on Pearl imager using Image Studio V5 software with the default setting for animal imaging as per manufacturer’s instructions. All quantifications were performed on Image Studio V5 as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Tumour disaggregation for flow and MC

Tumours were freshly isolated from wildtype or Osm−/− animals and immediately placed into ice-cold PBS (Fisher Scientific, 10091403), and kept on ice. All non-tumour tissues attached to tumours were thoroughly removed before proceeding further. Tumours were washed once with ice-cold RPMI media and minced into ~1 mm pieces using disposable scalpels in 2 mL of Disaggregation Buffer (DB; 2 mg/mL Collagenase Type IV (Thermo Fisher, 17104019), 1 mg/mL DNase1 (Sigma Aldrich, 10104159001) and 0.5 mg/mL Hyaluronidase (Sigma Aldrich, H3757) in RPMI). Tumour fragments were transferred into C-Tubes and individually disaggregated using GentleMACS Octo Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotech) on automated “37C_m_TDK1” programme. Once complete, the C-tubes were centrifuged at 100 g for 2 min, and the cell pellets were resuspended with fresh DB, and filtered through a 70 μm strainer. Cells were then washed with 10 mL ice-cold RPMI to quench the digestion. The single-cell suspension was pelleted at 300g for 6 min and used for flow and MC. Antibodies used are can be found in Supplementary Tables 1–3 and 6.

CAF isolation from mouse tumours

Single-cell dissociation of freshly isolated tumours was performed as described above. Cells were counted for each sample, and CD45+ cells were depleted using mouse CD45 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-052-301) and LS columns (130-042-401) following manufacturer’s recommendation. To discern viable cells, CD45+-depleted samples were stained with LIVE/DEAD Near-IR Dead Cell Stain Kit (LD) (ThermoFisher, L10119) following manufacturer’s recommendation. Cells were then washed and pelleted and stained with Fc block (BD Biosciences, 558636) for 5 min. A master mix of lineage and fibroblast marker antibodies was then added to each sample and incubated on ice for 30 min. Stained cells were washed in PBS, pelleted and resuspended in FACS Buffer (1% FBS in PBS) and kept on ice until FACS-isolation. Viable CAFs were sorted on BD FACSAria III Cell Sorter based on LD− CD45− EpCAM− CD31− PDPN+ CD90+ staining profile, and data analysed using Flowjo (BD Biosciences). Sorted CAFs were rapidly lysed and their RNA was extracted using RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen, 74034) for RT-qPCR assay.

MC antibodies and antibody conjugation

Fibroblast and immune cell (myeloid/NK/B cell (M/N/B) and T cell) antibody panels used for MC analyses in this study were generated as follows21. The dedicated panel builder (https://www.dvssciences.com) was used to estimate isotope and oxide spill-over and guide channel selection. Indicated antibodies were purchased pre-conjugated from Fluidigm, whereas all other antibodies were purchased in a carrier protein-free form and labelled with the indicated heavy-metal tag using Maxpar X8 Antibody Conjugation Kit (Fluidigm) as per manufacturer’s recommendations.

MC barcoding and antibody staining

Fibroblast MC analysis

Prior to setting up in vitro cultures, PCCs and MØs were labelled with EGFP using a lentivirus approach, as described above. PSC mono-culture (n = 3), PCC–PSC (n = 3) and PCC–PSC–MØ (n = 3) co-cultures were prepared as described above. After 72 h of in vitro cultures, 10 μL of 10 mM 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine (IdU) (Sigma Aldrich, 17125) solution in 0.2 M NaOH/water was added directly to the media, gently swirled and the cells incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. Cells were then washed in PBS, dislodged using Accutase Solution and quenched with CSM (Cell Staining Buffer), consisting of 5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma Aldrich, A3294) in PBS. Cells were filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, 340633). Subsequently, cells were resuspended and counted.

Barcoding

Totally, 3 × 106 cells from each culture condition were aliquoted into individual 5 mL polypropylene FACS tubes, pelleted and gentle mixed. A unique pair of lanthanide-conjugated anti-ITGB1 antibody pairs in 50 μL of CSM was then added to each sample. This live-cell barcoding method leveraged the consistently high expression of ITGB1 in fibroblasts, and in this instance a 5-choose-2 scheme (ITGB1-115In, -163Dy, -166Er, -169Tm, -172Yb) was used. Each sample was gently mixed and incubated on ice in the dark for 30 min. Cells from each sample were washed twice with CSM and combined into a 5 mL polypropylene FACS tube.

Live/dead cell staining

The pooled cells were resuspended in 300 μL of ice-cold PBS and vortexed well. Totally, 300 μL of 1 μM cisplatin (Fluidigm, 201064) in PBS was added into the cells, and incubated for 1 min. The staining was quenched with CSM, and cells were pelleted and aspirated. Subsequently, 60 μL of 100 U/mL heparin sodium salt (Sigma Aldrich, H3393) solution in PBS and 3 μL Fc block (BD Biosciences, 558636) was added to the cells. The cell mixture was gently mixed and incubated on ice for 5 min.

Fluorophore antibody staining

A master mix of fluorophore-conjugated antibodies in 150 μL CSM was added, gently mixed and incubated on ice in the dark for 45 min. Cells were washed with CSM and pelleted. Extracellular antibody staining. A master mix of 6 equivalents of extracellular targeting, metal-conjugated antibodies in 150 μL of CSM was added, gently mixed and incubated on ice in the dark for 45 min. Cells were washed twice with CSM.

Fixation and permeabilisation

The cell pellet was resuspended in 100 μL of PBS, vortexed and 2 mL of 1× FOXP3 Fixation Buffer from FOXP3 Fixation/Permeabilization Kit (Thermo Fisher, 00-5523-00) was added, followed by thorough vortexing. After 30 min incubation at RT, 2 mL of 1× FOXP3 Permeabilization Buffer was added and the cells were pelleted. Additional 2 mL of 1× FOXP3 Permeabilization Buffer was added and the cells were pelleted. Sixty microlitre of 100 U/mL heparin sodium salt in PBS and 3 μL of Fc block was added and the sample was mixed by gently rocking.

Intracellular antibody staining