Abstract

Remdesivir dry powder for inhalation was previously developed using thin film freezing (TFF). A single-dose 24-h pharmacokinetic study in hamsters demonstrated that pulmonary delivery of TFF remdesivir can achieve plasma remdesivir and GS-441524 levels higher than the reported EC50s of both remdesivir and GS-441524 (in human epithelial cells) over 20 h. The half-life of GS-4412524 following dry powder insufflation was about 7 h, suggesting the dosing regimen would be twice-daily administration. Although the remdesivir-Captisol® (80/20 w/w) formulation showed faster and greater absorption of remdesivir and GS-4412524 in the lung, remdesivir-leucine (80/20 w/w) exhibited a greater Cmax with shorter Tmax and lower AUC of GS-441524, indicating lower total drug exposure is required to achieve a high effective concentration against SAR-CoV-2. In conclusion, remdesivir dry powder for inhalation would be a promising alternative dosage form for the treatment of COVID-19 disease.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Remdesivir, Dry powder for inhalation, Thin film freezing, Pharmacokinetics

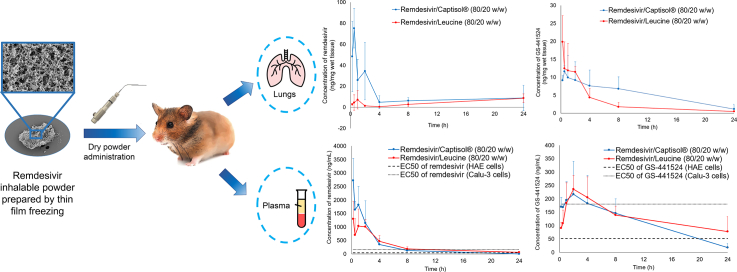

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) worldwide pandemic that is caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-CoV (SARS-CoV-2) has strained global health care systems. Although most COVID-19 patients experienced only mild respiratory symptoms, the infection can develop into acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pneumonia, and even multi-organ dysfunction which can be lethal (Singhal, 2020). As of January 2021, it has resulted in more than 86 million infected cases and 1.8 million deaths across the world (Johns Hopkins University, 2021). Several therapeutic agents have been investigated for the treatment of COVID-19 such as remdesivir, favipiravir, lopinavir/ritonavir, darunavir/cobicistat, nafamostat mesylate, chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine, camostat, tocilizumab, eculizumab, colchicine, baricitinib, aviptadil (Scavone et al., 2020) and niclosamide (Brunaugh et al., 2021); however, only remdesivir is currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in patients for the treatment of COVID-19 requiring hospitalization (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2020).

The investigational antiviral drug remdesivir (GS-5734) was originally developed for the treatment of Ebola virus infection by Gilead Sciences Inc. (Pardo et al., 2020). Remdesivir is a prodrug of the parent adenosine analog, GS-441524. The McGuigan prodrug moieties including phenol and L-alanine ethylbutyl ester help to increase lipophilicity and enhance cell permeability of the anionic phosphate moiety on remdesivir (Alanazi et al., 2019). These prodrug moieties are intracellularly metabolized by esterase to an alanine metabolite (GS-704277), and further metabolized by phosphoramidases to the monophosphorylated nucleotide (Yan and Muller, 2020). In the meantime, the parent nucleoside analogue core of remdesivir (GS-441524) can also diffuse into cells, and subsequently is converted to the monophosphorylated nucleotide (Eastman et al., 2020). Ultimately, the monophosphorylated nucleotide is metabolized into an active nucleoside triphosphate (NTP; GS-443902) by the host (Amirian and Levy, 2020). This active NTP inhibits viral RNA synthesis by competing with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for incorporation into the nascent RNA strand (Gordon et al., 2020).

Remdesivir has been repurposed for the treatment of COVID-19 as it is effective against COVID-19 in the human airway epithelial cell (Agostini et al., 2018). Recently, several on-going clinical trials have investigated the efficacy and safety of remdesivir (McCreary and Angus, 2020, National Library of Medicine U.S., 2020a, National Library of Medicine U.S., 2020b). In a double-blind clinical trial, severe COVID-19 patients receiving a 10-day course of remdesivir had a shorter recovery time compared to the placebo group (11 days vs. 15 days) (Beigel et al., 2020). In another clinical trial, the efficacy of a 5-day course of remdesivir or a 10-day course of remdesivir were compared with standard care in hospitalized patients with confirmed SAR-CoV-2 and moderate COVID-19 pneumonia among 105 hospitals in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The results showed the 5-day course had better clinical status distribution, compared to standard care (Spinner et al., 2020).

Currently, remdesivir is only available as a lyophilized powder for reconstitution and intravenous (IV) infusion, and concentrate solution for dilution and IV infusion (Gilead Sciences, Inc., 2020). Although the plasma concentration of remdesivir following IV administration can achieve two out of four reported IC50 values and two out of three reported IC90 values for the prodrug (Rasmussen et al., 2020), the current dosage forms are limited to only hospitalized patients, excluding outpatient care. Therefore, alternative dosage forms of remdesivir for different routes of administration are necessary to improve the accessibility of the drug for patients besides those who are critically ill.

Pulmonary administration of remdesivir is a promising strategy to improve the efficacy of the treatment towards SAR-CoV2 infection as it can maximize localized lung tissue concentrations while avoiding systemic toxicities. Our group previously developed remdesivir dry powders for inhalation by thin film freezing (TFF) (Sahakijpijarn et al., 2020a). The remdesivir dry powder formulations were optimized by combining with different excipients (e.g., Captisol®, mannitol, lactose, leucine) at different amounts (20%, 50%, and 80% w/w). Although only lactose and mannitol have been approved in FDA-approved inhaled products (Sahakijpijarn et al., 2020b), leucine and Captisol® are excipients in inhaled products that are currently under-investigated in FDA clinical trials (National Library of Medicine U.S., 2017, National Library of Medicine U.S., 2020c, Pilcer and Amighi, 2010). Additionally, Captisol® was selected in the study since it is used as a solubilizer in current remdesivir products (European Medicines Agency, 2020). After the TFF process, Remdesivir, lactose, and Captisol® were amorphous, while mannitol and leucine remained crystalline. The in vitro aerodynamic testing showed the drug loading can be increased up to 80% while maintaining optimal aerosol performance (up to 82.71 ± 2.54% fine particle fraction (FPF) of recovered dose, 1.45 ± 0.07 μm mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD)). Among different excipients, leucine and Captisol® exhibited higher FPF and smaller MMAD. The stability study showed both Captisol® and leucine-based formulations were chemically and physically stable after one-month storage at 25 °C/60%RH. Besides, the aerosol performance did not significantly change after one-month storage at 25 °C/60%RH (Sahakijpijarn et al., 2020a). Moreover, an in vivo pharmacokinetic study in rats demonstrated that remdesivir-Captisol (80/20) exhibited a faster absorption of remdesivir into the systemic circulation, resulting in a higher amount of remdesivir in plasma and a lower amount of GS-441524 in both plasma and lung tissue, compared to a remdesivir-leucine (80/20) formulation (Sahakijpijarn et al., 2020a).

To further understand the pharmacokinetic profile of remdesivir and GS-441524 following administration by dry powder inhalation, this study aimed to determine its PK parameters from both plasma and lung tissue in healthy Syrian hamsters. Small animal models that closely resemble the clinical and pathological features of SAR-CoV-2-induced diseases in humans are essential tools for the evaluation of antiviral drugs against COVID-19. Recently, it was reported SAR-CoV-2 replicated efficiently in the respiratory tract of Syrian hamsters and subsequently developed to a mild lung disease, which is similar to the disease found in early-stage COVID-19 patients (Chan et al., 2020). Therefore, Syrian hamsters were selected as an animal model in this study as they have been shown a useful mammalian model for studying pathogenesis, treatment, and vaccination against SAR-CoV-2 (Chan et al., 2020; Imai et al., 2020; Kaptein et al., 2020).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Remdesivir for sample preparation was purchased from Medkoo Biosciences (Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). Remdesivir, GS-441524, and its heavy isotope internal standards were purchased from Alsachim (Illkirch-Graffenstaden, France). Leucine was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Sulfobutylether-beta-cyclodextrin (SBECD, Captisol®) was kindly provided by Ligand Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (San Diego, CA).

2.2. Preparation of dry powder for inhalation

Two formulations were prepared for the pharmacokinetic study including remdesivir-Captisol (REM-CAP; 80/20 w/w), and remdesivir-leucine (REM-LEU; 80/20 w/w). Remdesivir and excipients (i.e., Captisol® and leucine) were dissolved in a mixture of acetonitrile/water (50/50 v/v) at a 0.3% w/v solids content. The solution was dropped onto a rotating cryogenically cooled stainless-steel drum through an 18-gauge syringe needle. The drum surface temperature was controlled at approximately −100 °C. The frozen samples were collected in a stainless-steel container filled with liquid nitrogen and then transferred into a −80 °C freezer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The formulations were dried using a lyophilizer (SP Industries Inc., Warminster, PA, USA) at 100 mTorr. The drying cycle was set at −40 °C for 20 h, and then ramped to 25 °C for 20 h, and finally secondary drying at 25 °C for 20 h.

2.3. Single-dose dry powder insufflation in hamsters

This study was in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; Protocol Number AUP-2019-00254) guidelines at The University of Texas at Austin. Female Syrian hamsters (Charles River, 049LVG) 35-42-days old and weighing between 80 and 130 g (average weight of 102 g) were housed in a 12-h light/dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum and were subjected to one week of acclimation to the housing environment. Seventy hamsters were separated into two equal groups by body weight (REM-CAP and REM-LEU).

TFF powder formulation was passed through a No. 200 sieve (75 μm aperture) to break down large aggregates into fine particles. Precisely weighed quantities of sieved TFF powder were administered to hamsters intratracheally using a dry powder insufflator (DP-4 model, Penn-Century Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA) connected to an air pump (AP-1 model, Penn-Century Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA). The dose of remdesivir was targeted to be 10 mg/kg. Each hamster was briefly anesthetized with isoflurane (4% induction, 2% maintenance) and placed on its back on an intubation stand. Its upper incisors were used to secure the hamster using silk at a 45° angle, with continuous delivery of anesthesia through a nose cone. A laryngoscope was used to visualize the trachea, and the blunt metal end of the insufflator device was inserted into the trachea. The sieved TFF powder was actuated into the lung using 3 puffs of the connected pump (200 μL of air per puff). The mass of powder delivered was measured by weighing the device chamber before and after dose actuations.

Following powder administration, five hamsters from each group were harvested at each time point (15 mins, 30 mins, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 h). Blood was drawn via cardiac puncture and immediately transferred into a heparinized microtainer (BD, 365985, Lithium Heparin/PST™ Gel). The blood sample was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 1.5 min, and the plasma was separated and frozen on dry ice. The hamster was carefully perfused with PBS, the lung was washed with 1 mL of PBS to remove the residual dry powder, and the lung was removed, weighed, and frozen. Plasma samples and lungs were kept frozen and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

2.4. Quantification of remdesivir and its metabolites in plasma and lung tissue

For plasma samples, remdesivir and its metabolites were extracted according to the following protocol (Sahakijpijarn et al., 2020a). Briefly, 100 μL of plasma was combined with 100 μL of methanol containing 100 ng/mL of the heavy labeled internal standards for remdesivir and GS-441524. The samples were mixed using a vortex mixer and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and placed in a 96-well plate for LC/MS/MS analysis.

For lung tissue samples, remdesivir and its metabolites were extracted according to the following protocol (Sahakijpijarn et al., 2020a). Briefly, lung tissue samples were added into a 2 mL tube with 3.5 g of 2.3 mm zirconia/silica beads (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA), and homogenized at 4800 rpm for 20 s. After homogenization, 1000 μL of methanol containing 100 ng/mL internal standards for remdesivir and GS-441524 was added to the tube. The tube was then vortexed and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was placed in a 96-well plate for LC/MS/MS analysis. Calibration standards were prepared for plasma and lung tissue in the same protocol. Remdesivir and GS-441524 standard solutions were spiked into the blank plasma and lung tissue to obtain matrix-matched calibrations. The calibration range for plasma and lung tissue was 0.1–1000 ng/mL, and 50–10,000 ng/mL, respectively. The calibration range was selected to bracket sample levels measured.

The content of Remdesivir and GS-441524 were analyzed with an Agilent 6470 triple quadrupole LC/MS/MS system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). An Agilent Poroshell column (2.1 × 50 mm, 2.7 μm) (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used at 40 °C with a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min. The gradient method with a mobile phase ratio of 0 to 90.25% of acetonitrile with 0.025% trifluoroacetic acid was used for total running time of 5 min. In total, 10 μL of each sample was injected for analysis.

2.5. Pharmacokinetic analysis

Remdesivir and metabolite GS-441524 plasma and lung concentrations over time data were analyzed by non-compartmental analysis using PKSolver to obtain pharmacokinetic parameters in the hamster model after inhalation of the formulations (Zhang et al., 2010). Due to the sparse sampling requirements with this animal model and to obtain lung concentrations over time a naïve pooled-data approach was used in which the noncompartmental analysis was fit to the data as if the average of the measured concentrations from the five animals at each time point were taken from a single subject. This was based on the methods previously reported for estimating population kinetics from very small sample sizes (Mahmood, 2014; Mentré et al., 1995).

3. Results

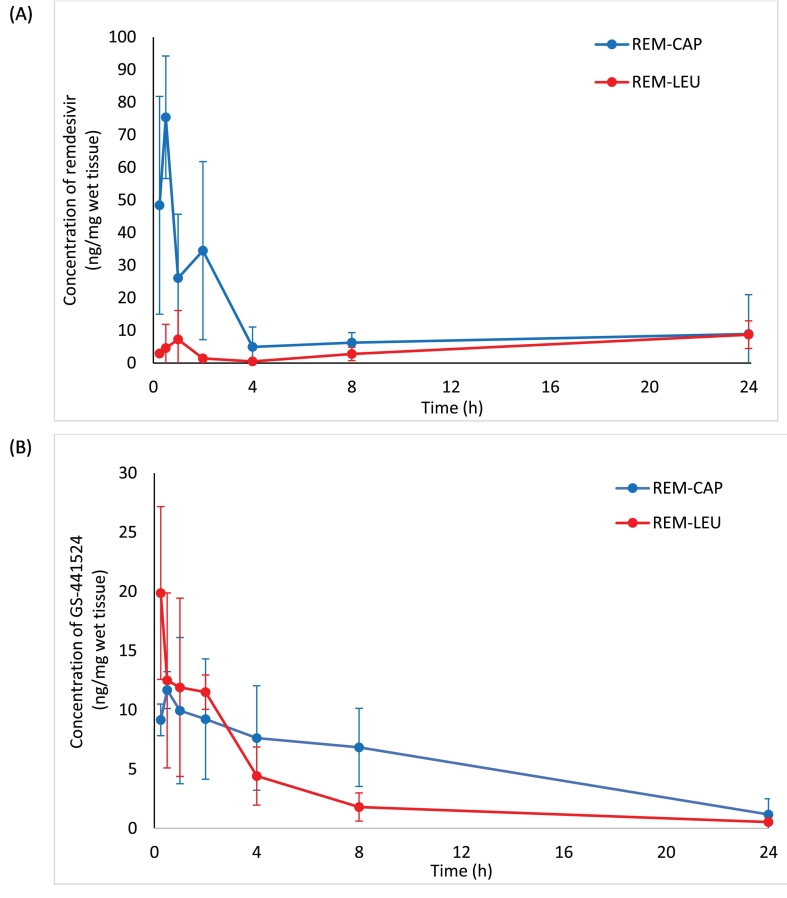

The concentrations of remdesivir and GS-441524 were determined in plasma and lung tissue from healthy hamsters treated with a single 10 mg/kg remdesivir dry powder insufflation of remdesivir/Captisol (REM-CAP) or remdesivir/leucine (REM-LEU) formulation. The resulting lung tissue concentration-versus-time curves are shown in Fig. 1, while the corresponding pharmacokinetic parameters are summarized in Table 1. The Cmax of remdesivir for REM-CAP was 8-fold higher than that of REM-LEU (75.41 ng/mg VS 8.71 ng/mg, respectively), while Tmax of remdesivir for REM-CAP was lower compared to REM-LEU (30 mins VS 24 h, respectively). Additionally, REM-CAP exhibited higher AUC0-24 of remdesivir in the lungs than REM-LEU, indicating higher absorption of remdesivir in the lung.

Fig. 1.

Lung concentration-time profiles of REM-CAP (remdesivir-Captisol®; 80/20 w/w) and REM-LEU (remdesivir-leucine; 80/20 w/w) after a single inhalation administration in hamsters; (A) remdesivir; (B) GS-441524.

Table 1.

In vivo pharmacokinetic parameters for lung remdesivir and GS-441524 concentrations of REM-CAP and REM-LEU following a single 10 mg/kg inhalation administration.

| Pharmacokinetic parameters | REM-CAP |

REM-LEU |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remdesivir | GS-441524 | Remdesivir | GS-441524 | |

| T1/2 (h) | – | 7.38 | – | 7.12 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 24 | 0.25 |

| Cmax (ng/mg) | 75.41 | 11.68 | 8.71 | 19.88 |

| AUC 0–24h (ng·h/mg) | 260.30 | 128.61 | 109.16 | 71.39 |

| AUC 0-inf (ng·h/mg) | – | 141.11 | – | 76.85 |

| MRT0-inf (h) | – | 9.46 | – | 6.94 |

| V/F (mg/kg)/(ng/mg) | – | 0.75 | – | 1.34 |

| Cl/F ((mg/kg)/(ng/mg)/h) | 0.00147 | 0.00345 | 0.00140 | 0.00209 |

For the level of a metabolite in the lungs, the AUC0-24 of GS-441524 of REM-CAP was about 1.7 times higher than that of REM-LEU (128.61 ng·h/mg VS 71.39 ng·h/mg, respectively). Despite this, REM-LEU exhibited a higher Cmax of GS-441524 (19.88 ng/mg VS 11.68 ng/mg) and shorter Tmax of GS-441524 (15 mins VS 30 mins) as compared to REM-CAP. GS-441524, in both formulations, was eliminated in a biphasic pattern with a distribution phase and an elimination phase. The half-life of GS-441524 for both formulations are similar (7.12 h for REM-CAP and 7.38 h for REM-LEU).

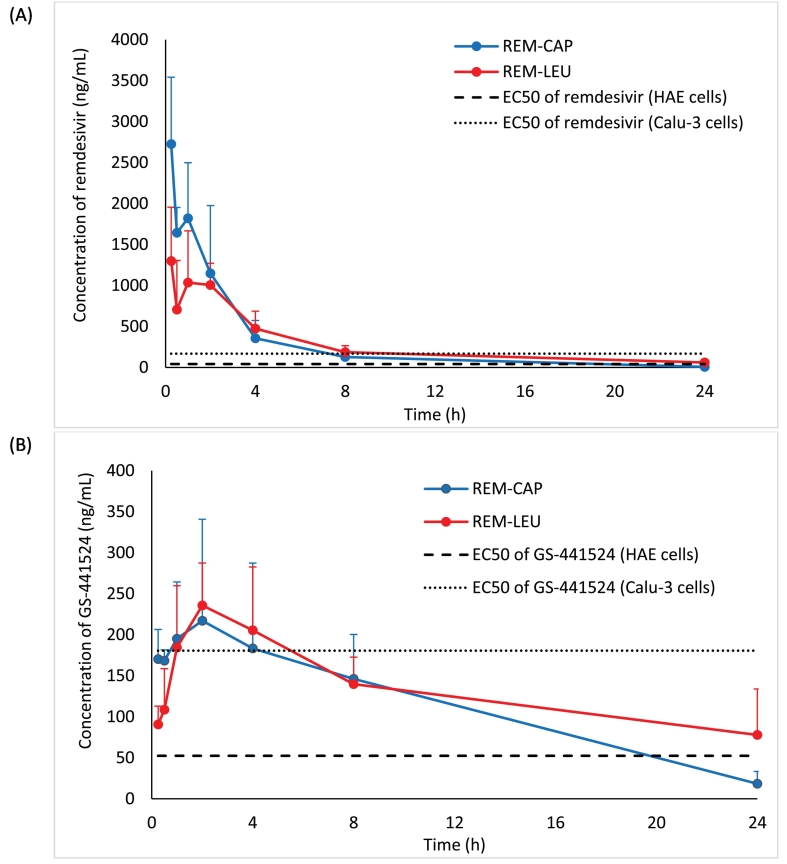

The systemic in vivo pharmacokinetics of drug absorption from the lungs was also investigated in hamsters. Fig. 2 shows the comparison of the mean remdesivir and GS-441524 plasma concentration-time profile from each formulation. The pharmacokinetic parameters following a single dose dry powder insufflation calculated using a non-compartment model are presented in Table 2. Overall, both formulations have similar plasma profiles of remdesivir and GS-441524. Rapid remdesivir concentration decay was observed in both formulations 30 mins following pulmonary administration before reaching the elimination phase. Similarly, GS-441524 plasma concentration for both formulations reached the maximum at 2 h, and continuously decreased after 2 h following pulmonary insufflation.

Fig. 2.

Plasma concentration-time profiles of REM-CAP (remdesivir-Captisol®; 80/20 w/w) and REM-LEU (remdesivir-leucine; 80/20 w/w) after a single inhalation administration in hamsters; (A) remdesivir; (B) GS-441524. Dash line and dot line represent EC50 of remdesivir and GS-441524 in human epithelial cells (HAE) (Agostini et al., 2018), and continuous human lung epithelial cell line (Calu-3) (Gilead Sciences, Inc., 2020), respectively.

Table 2.

In vivo pharmacokinetic parameters for plasma remdesivir and GS-441524 concentrations of REM-CAP and REM-LEU following a single 10 mg/kg inhalation administration.

| Pharmacokinetic parameters | REM-CAP |

REM-LEU |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remdesivir | GS-441524 | Remdesivir | GS-441524 | |

| T1/2 (h) | 3.65 | 6.04 | 5.62 | 14.26 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.25 | 2 | 0.25 | 2 |

| Cmax (ng/mg) | 2726.74 | 217.10 | 1298.65 | 235.78 |

| AUC0-24 (ng·h/mL) | 6779.83 | 2736.11 | 6647.90 | 3191.93 |

| AUCinf (ng·h/mL) | 6818.37 | 2895.69 | 7139.81 | 4792.48 |

| MRT0-inf (h) | 3.26 | 8.11 | 7.29 | 21.03 |

| V/F (mg/kg)/(ng/mg) | 0.0077 | 0.0301 | 0.0113 | 0.0429 |

| Cl/F ((mg/kg)/(ng/mg)/h) | 0.0015 | 0.0035 | 0.0014 | 0.0021 |

Although similar absorption patterns of remdesivir and GS-441524 were observed, the pharmacokinetic parameters were slightly different. REM-CAP exhibited higher mean remdesivir plasma concentration 15 mins following pulmonary administration when compared to REM-LEU (2726.74 ng/mL VS 1298.65 ng/mL, respectively). However, both formulations have similar AUC0-24 and AUC0-inf of remdesivir, indicating a similar extent of drug absorption into the systemic circulation.

For GS-441524 plasma levels, although no significant difference in Cmax and Tmax of GS-441524 between two formulations was observed, the AUC 0–24 of GS-441524 from REM-LEU was slightly higher than that of REM-CAP (3192.93 ng/mL VS 2736.11 ng/mL, respectively). Similarly, REM-LEU showed higher AUC0-inf of GS-441524 compared to REM-CAP (4792.48 ng/mL VS 2895.69, respectively).

Interestingly, the half-life of remdesivir from REM-LEU was longer than that of REM-CAP (5.62 VS 3.65 h, respectively). Likewise, REM-LEU exhibited a longer half-life of GS-441524 in plasma, compared to REM-CAP (14.26 h VS 6.04 h, respectively). This agrees with the mean residence time (MRT) of remdesivir and GS-441524. REM-LEU exhibited longer MRT0-inf of remdesivir and GS-441524, indicating remdesivir and GS-441524 were cleared from the plasma more slowly than from REM-CAP formulation.

4. Discussions

The in vivo pharmacokinetic results showed that pulmonary administration can produce plasma concentrations that achieve higher than the 50% maximal effective concentration (EC50). The EC50 is used to quantify the in vitro antiviral efficacy of drugs. Since the activity of antiviral agents depends on the cell type used for viral propagation, viral isolate, and viral quantification (Rasmussen et al., 2020), several EC50 values of remdesivir and GS-441524 against SARS-CoV-2 in different cell lines are reported (Agostini et al., 2018; Pruijssers et al., 2020; Sheahan et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020). Agostini et al. reported EC50 of remdesivir and GS-441524 against SAR-CoV-2 in human airway epithelial (HAE) to 70 nM (42.18 ng/mL) and 180 nM (52.43 ng/mL), respectively (Agostini et al., 2018). According to the prescribing information of Veklury®, the EC50 of remdesivir in HAE cells and continuous human lung epithelial cell line (Calu-3) is 9.9 nM (5.97 ng/mL) and 280 nM (168.73 ng/mL), respectively (Gilead Sciences, Inc., 2020). Pruijssers et al. also reported that the EC50 of remdesivir and GS-441524 in Calu-3 2B4 cells is 280 nM (168.73 ng/mL), and 620 nM (180.6 ng/mL), respectively (Pruijssers et al., 2020). Despite differences in the reported EC50 values, plasma concentrations following dry powder pulmonary insufflation of both formulations were higher than these reported EC50 values for remdesivir and GS-441524 in HAE cells at least over 20 h, and higher than the remdesivir EC50 in Calu-3 cells for over 8 h and likewise 4 h for GS-441524.

The plasma GS-441524 concentration-time profiles in our hamster study are consistent with our previous pharmacokinetic study in rats (Sahakijpijarn et al., 2020a). In the rat PK study, the average Cmax of REM-CAP and REM-LEU was in the range of 220–264 ng/L. Likewise, the AUC0-24 and AUCinf of both formulations in the rats were in the range of 2115.3–2778.5 ng·h/mL, and 2397.8–3204.9 ng·h/mL, respectively, which are close to the values in our hamster study. Despite the fact that different species have different drug metabolism rates, both studies indicated that pulmonary administration of remdesivir can achieve GS-441524 concentrations higher than the EC50.

Our in vivo pharmacokinetic results also provide useful information about dosing interval and dosing regimen. GS-441524 remained in the lungs for about 8 h before plateauing (Fig. 1B). The half-life of GS-441524 in the lungs of both formulations was about 7 h. Therefore, the suggested dosing regimen of inhaled remdesivir would be twice daily.

An effect of excipients on the pharmacokinetics parameters was also observed in this study. REM-CAP exhibited a faster and greater absorption of remdesivir in the lung, as the results showed shorter Tmax, greater Cmax, and higher AUC of remdesivir in the lung. Additionally, REM-CAP produced a greater Cmax of remdesivir in plasma when compared to REM-LEU. As reported in the previous study, the presence of Captisol® resulted in the faster absorption of remdesivir compared to the leucine formulation (Sahakijpijarn et al., 2020a). This is possibly related to the properties of Captisol®. As reported in the literature, Captisol® is a sulfobutyl ether derivative of β-cyclodextrin that can produce complexes with poorly soluble lipophilic drugs, and therefore enhance aqueous solubility and dissolution (Lockwood et al., 2003), and the bioavailability of drugs (Beig et al., 2015). Since REM-CAP contains remdesivir and Captisol® in an 80/20 weight ratio (i.e., 10:1 molar ratio of remdesivir: Captisol®), we hypothesized that approximately 10% of the remdesivir (on a weight basis) is complexed with Captisol® in a solubilized form (Sahakijpijarn et al., 2020a). According to Eriksson et al., a drug in the solution state exhibited a faster absorption than a drug in dry powder form in an isolated perfused lung model since it can bypass the dissolution process which is the rate-limiting step in the absorption process when administering poorly water-soluble drug particles (Eriksson et al., 2019). Another study by Tolman et al. also demonstrated that the complexation of drug and Captisol® can enhance the absorption of voriconazole to the systemic circulation since the AUCplasma to AUClung ratio of the nebulized voriconazole formulation with Captisol® was 8-fold higher than that of nanostructured amorphous voriconazole powder formulations following pulmonary administration (0.64 vs. 0.08, respectively) (Beinborn et al., 2012; Tolman et al., 2009). Based on several studies, the inclusion of drug and Captisol® is likely to improve the dissolution of remdesivir in lung fluid and to enhance absorption of remdesivir into the airway epithelial cell, as well as increase the absorption rate into the systemic circulation (Stella and Rajewski, 2020; Yang, 2020).

Interestingly, our current study demonstrated that the complexation of Captisol® and remdesivir appeared only to have an effect on the absorption rate, but not on the extent of drug absorption into the systemic circulation. The slower lung absorption of remdesivir of REM-LEU did not affect the absorption into systemic circulation as both formulations showed similar AUC0-24h and Tmax of remdesivir in plasma. Moreover, in terms of the efficacy of antiviral agents, pulmonary administration of REM-LEU can produce a higher Cmax of GS-441524 with a shorter Tmax and a lower AUC of GS-441524, indicating a lower total exposure of GS-441524 is needed to produce high GS-441524 levels in the lung for inhibiting virus replication. Therefore, REM-LEU would be a favorable formulation for further development.

5. Conclusions

We have demonstrated that dry powder administration can deliver remdesivir to the lungs and subsequently can be converted to GS-441524 both in the lungs and plasma of hamsters. The level of remdesivir and GS-441524 in plasma was sufficiently high to provide antiviral activity. The elimination rate of remdesivir and GS-441524 from the lungs will be useful information for future efficacy studies. Lastly, dry powder remdesivir for inhalation is a promising way to improve the treatment of COVID-19 and provide an alternative dosage form on an outpatient basis.

Funding

This research was funded by TFF Pharmaceuticals, Inc. through a sponsored research agreement at The University of Texas at Austin.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Moon, Sahakijpijarn, Warnken, and Williams are co-inventors of related intellectual property (IP). The Board of Regents of The University of Texas has licensed IP covering inhaled remdesivir formulations prepared with thin film freezing to TFF Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Moon and Sahakijpijarn acknowledge consulting for TFF Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Williams acknowledges ownership of stock in TFF Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Drug Dynamics Institute and its core facility TherapeUTex for conducting the animal study.

References

- Agostini M.L., Andres E.L., Sims A.C., Graham R.L., Sheahan T.P., Lu X., Smith E.C., Case J.B., Feng J.Y., Jordan R., Ray A.S., Cihlar T., Siegel D., Mackman R.L., Clarke M.O., Baric R.S., Denison M.R. Coronavirus susceptibility to the antiviral remdesivir (GS-5734) is mediated by the viral polymerase and the proofreading exoribonuclease. mBio. 2018;9 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00221-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanazi A.S., James E., Mehellou Y. The protide prodrug technology: where next? ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;10:2–5. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirian S.E., Levy J.K. Current knowledge about the antivirals remdesivir (GS-5734) and GS-441524 as therapeutic options for coronaviruses. One Health. 2020;9:100128. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beig A., Agbaria R., Dahan A. The use of captisol (SBE7-β-CD) in oral solubility-enabling formulations: Comparison to HPβCD and the solubility–permeability interplay. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015;77:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beigel J.H., Tomashek K.M., Dodd L.E., Mehta A.K., Zingman B.S., Kalil A.C., Hohmann E., Chu H.Y., Luetkemeyer A., Kline S., Lopez de Castilla D., Finberg R.W., Dierberg K., Tapson V., Hsieh L., Patterson T.F., Paredes R., Sweeney D.A., Short W.R., Touloumi G., Lye D.C., Ohmagari N., Oh M.-D., Ruiz-Palacios G.M., Benfield T., Fätkenheuer G., Kortepeter M.G., Atmar R.L., Creech C.B., Lundgren J., Babiker A.G., Pett S., Neaton J.D., Burgess T.H., Bonnett T., Green M., Makowski M., Osinusi A., Nayak S., Lane H.C. Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19 — final report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinborn N.A., Du J., Wiederhold N.P., Smyth H.D., Williams R.O., 3rd Dry powder insufflation of crystalline and amorphous voriconazole formulations produced by thin film freezing to mice. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012;81:600–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunaugh A.D., Seo H., Warnken Z., Ding L., Seo S.H., Smyth H.D.C. Development and evaluation of inhalable composite niclosamide-lysozyme particles: A broad-spectrum, patient-adaptable treatment for coronavirus infections and sequalae. PloS one. 2021;16(2):e0246803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.F., Zhang A.J., Yuan S., Poon V.K., Chan C.C., Lee A.C., Chan W.M., Fan Z., Tsoi H.W., Wen L., Liang R., Cao J., Chen Y., Tang K., Luo C., Cai J.P., Kok K.H., Chu H., Chan K.H., Sridhar S., Chen Z., Chen H., To K.K., Yuen K.Y. Simulation of the clinical and pathological manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a golden syrian hamster model: implications for disease pathogenesis and transmissibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:2428–2446. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman R.T., Roth J.S., Brimacombe K.R., Simeonov A., Shen M., Patnaik S., Hall M.D. Remdesivir: a review of its discovery and development leading to emergency use authorization for treatment of COVID-19. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020;6:672–683. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson J., Thorn H., Sjogren E., Holmsten L., Rubin K., Lennernas H. Pulmonary dissolution of poorly soluble compounds studied in an ex vivo rat lung model. Mol. Pharm. 2019;16:3053–3064. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA Approves First Treatment for COVID-19, October 22, 2020 ed. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. 2010.

- European Medicines Agency Summary on Compassionate Use: Remdesivir Gilead. EMA/178637/2020. 2020 https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/summary-compassionate-use-remdesivir-gilead_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gilead Sciences, Inc. Veklury® (Remdesivir) for Hospitalized Pediatric Patients [Prescribing Information] U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/214787Orig1s000lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C.J., Tchesnokov E.P., Feng J.Y., Porter D.P., Götte M. The antiviral compound remdesivir potently inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:4773–4779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC120.013056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai M., Iwatsuki-Horimoto K., Hatta M., Loeber S., Halfmann P.J., Nakajima N., Watanabe T., Ujie M., Takahashi K., Ito M., Yamada S., Fan S., Chiba S., Kuroda M., Guan L., Takada K., Armbrust T., Balogh A., Furusawa Y., Okuda M., Ueki H., Yasuhara A., Sakai-Tagawa Y., Lopes T.J.S., Kiso M., Yamayoshi S., Kinoshita N., Ohmagari N., Hattori S.-I., Takeda M., Mitsuya H., Krammer F., Suzuki T., Kawaoka Y. Syrian hamsters as a small animal model for SARS-CoV-2 infection and countermeasure development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117:16587–16595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009799117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) Coronavirus Resource Center. 2021 https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein S.J., Jacobs S., Langendries L., Seldeslachts L., ter Horst S., Liesenborghs L., Hens B., Vergote V., Heylen E., Maas E., De Keyzer C., Bervoets L., Rymenants J., Van Buyten T., Thibaut H.J., Dallmeier K., Boudewijns R., Wouters J., Augustijns P., Verougstraete N., Cawthorne C., Weynand B., Annaert P., Spriet I., Velde G.V., Neyts J., Rocha-Pereira J., Delang L. Antiviral treatment of SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters reveals a weak effect of favipiravir and a complete lack of effect for hydroxychloroquine. bioRxiv. 2020 2020.2006.2019.159053. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood S.F., O’Malley S., Mosher G.L. Improved aqueous solubility of crystalline astaxanthin (3,3′-dihydroxy-beta, beta-carotene-4,4′-dione) by Captisol (sulfobutyl ether beta-cyclodextrin) J. Pharm. Sci. 2003;92:922–926. doi: 10.1002/jps.10359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood I. Naive pooled–data approach for pharmacokinetic studies in pediatrics with a very small sample size. Am. J. Ther. 2014;21 doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31824ddee3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary E.K., Angus D.C. Efficacy of remdesivir in COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:1041–1042. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentré F., Burtin P., Merlé Y., van Bree J., Mallet A., Steimer J.-L. Sparse-sampling optimal designs in pharmacokinetics and toxicokinetics. Drug Inf. J. 1995;29:997–1019. [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine (U.S.) A study of AeroVanc for the treatment of MRSA infection in CF patients. ClinicalTrials.gov, No. NCT03181932. 2017 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03181932 [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine (U.S.) A Trial of Remdesivir in Adults With Mild and Moderate COVID-19. ClinicalTrials.gov, No. NCT04252664. 2020 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04252664 [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine (U.S.) A Trial of Remdesivir in Adults With Severe COVID-19. ClinicalTrials.gov, No. NCT04257656. 2020 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04257656 [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine (U.S.) Study in Participants With Early Stage Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) to Evaluate the Safety, Efficacy, and Pharmacokinetics of Remdesivir Administered by Inhalation. ClinicalTrials.gov, No. NCT04539262. 2020 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04539262 [Google Scholar]

- Pardo Joe, Shukla Ashutosh M, Chamarthi Gajapathiraju, Gupte Asmita. The journey of remdesivir: from Ebola to COVID-19. Drugs in Context. 2020;9:2020–4–14. doi: 10.7573/dic.2020-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilcer G., Amighi K. Formulation strategy and use of excipients in pulmonary drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2010;392:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruijssers A.J., George A.S., Schäfer A., Leist S.R., Gralinksi L.E., Dinnon K.H., Yount B.L., Agostini M.L., Stevens L.J., Chappell J.D., Lu X., Hughes T.M., Gully K., Martinez D.R., Brown A.J., Graham R.L., Perry J.K., Du Pont V., Pitts J., Ma B., Babusis D., Murakami E., Feng J.Y., Bilello J.P., Porter D.P., Cihlar T., Baric R.S., Denison M.R., Sheahan T.P. Remdesivir inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in human lung cells and chimeric SARS-CoV expressing the SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase in mice. Cell Rep. 2020;32:107940. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen H.B., Hansen P.R., Taboureau O., Thomsen R., Jürgens G. Pulmonary administration of remdesivir in the treatment of COVID-19. AAPS J. 2020;22:1–2. doi: 10.1208/s12248-020-00506-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakijpijarn S., Moon C., Koleng J.J., Christensen D.J., Williams Iii R.O. Development of remdesivir as a dry powder for inhalation by thin film freezing. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(11):1002. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12111002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakijpijarn S., Smyth H.D.C., Miller D.P., Weers J.G. Post-inhalation cough with therapeutic aerosols: formulation considerations. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020;165–166:127–141. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scavone C., Brusco S., Bertini M., Sportiello L., Rafaniello C., Zoccoli A., Berrino L., Racagni G., Rossi F., Capuano A. Current pharmacological treatments for COVID-19: what’s next? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020;177:4813–4824. doi: 10.1111/bph.15072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheahan T.P., Sims A.C., Graham R.L., Menachery V.D., Gralinski L.E., Case J.B., Leist S.R., Pyrc K., Feng J.Y., Trantcheva I., Bannister R., Park Y., Babusis D., Clarke M.O., Mackman R.L., Spahn J.E., Palmiotti C.A., Siegel D., Ray A.S., Cihlar T., Jordan R., Denison M.R., Baric R.S. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9:eaal3653. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) Indian J. Pediatr. 2020;87:281–286. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinner C.D., Gottlieb R.L., Criner G.J., Arribas López J.R., Cattelan A.M., Soriano Viladomiu A., Ogbuagu O., Malhotra P., Mullane K.M., Castagna A., Chai L.Y.A., Roestenberg M., Tsang O.T.Y., Bernasconi E., Le Turnier P., Chang S.-C., SenGupta D., Hyland R.H., Osinusi A.O., Cao H., Blair C., Wang H., Gaggar A., Brainard D.M., McPhail M.J., Bhagani S., Ahn M.Y., Sanyal A.J., Huhn G., Marty F.M., Investigators, f.t.G.-U.-.-. Effect of remdesivir vs standard care on clinical status at 11 days in patients with moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:1048–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella V.J., Rajewski R.A. Sulfobutylether-beta-cyclodextrin. Int. J. Pharm. 2020;583:119396. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman J.A., Nelson N.A., Son Y.J., Bosselmann S., Wiederhold N.P., Peters J.I., McConville J.T., Williams R.O., 3rd Characterization and pharmacokinetic analysis of aerosolized aqueous voriconazole solution. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009;72:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., Shi Z., Hu Z., Zhong W., Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan V.C., Muller F.L. Advantages of the parent nucleoside GS-441524 over remdesivir for covid-19 treatment. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:1361–1366. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K. What do we know about remdesivir drug interactions? Dlin. Transl. Sci. 2020;13:842–844. doi: 10.1111/cts.12815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Huo M., Zhou J., Xie S. PKSolver: an add-in program for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data analysis in Microsoft Excel. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 2010;99:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]