Abstract

Background

Social connection is recognized as an important determinant of health and well-being. The negative health impacts of poor social connection have been reported in research in older adults, however, less is known about the health impacts for those living in long-term care (LTC) homes. This review seeks to identify and summarize existing research to address the question: what is known from the literature about the association between social connection and physical health outcomes for people living in LTC homes?

Methods

A scoping review guided by the Arksey & O’Malley framework was conducted. Articles were included if they examined the association between social connection and a physical health outcome in a population of LTC residents.

Results

Thirty-four studies were included in this review. The most commonly studied aspects of social connection were social engagement (n = 14; 41%) and social support (n = 10; 29%). A range of physical health outcomes were assessed, including mortality, self-rated health, sleep, fatigue, nutrition, hydration, stress, frailty and others. Findings generally support the positive impact of social connection for physical health among LTC residents. However, most of the studies were cross-sectional (n = 21; 62%) and, of the eleven cohort studies, most (n = 8; 73%) assessed mortality as the outcome. 47% (n = 16) were published from 2015 onwards.

Conclusions

Research has reported positive associations between social connection and a range of physical health outcomes among LTC residents. These findings suggest an important role for social connection in promoting physical health. However, further research is needed to consider the influence of different aspects of social connection over time and in different populations within LTC homes as well as the mechanisms underlying the relationship with health.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-021-02638-4.

Keywords: Scoping review, Long-term care, Older adults, Nursing home, Physical health, Social connection

Background

Social connection (including social networks, social engagement, social support, and loneliness) is recognized as a key determinant of health and well-being [1, 2]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses suggest social connection influences not only mental health, but also physical health outcomes, including mortality [3, 4], coronary heart disease, and stroke [5]. A 2015 meta-analysis found that low social integration and low social support, two aspects of social connection, had a greater impact on mortality than smoking, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, and alcohol consumption [3]. The mechanisms underlying these associations have been postulated to include immune system function [6], stress regulation [7], and health behaviours (e.g., diet and exercise) [8]. Loneliness and social isolation, concepts reflecting poor quality or quantity of social connection, have also been posited to create barriers to healthy behaviour engagement and treatment plan adherence [9, 10].

Social isolation and loneliness are widespread in LTC homes [11, 12], however, relatively little is known about the health impacts in this setting [12–14]. Given the characteristics of LTC homes and their residents [15, 16], research is needed to specifically address issues of social connection in this population [12, 14]. For example, LTC homes have an integral role in enabling social connection for residents, such as through the home environment (e.g. shared living spaces, planned social and recreational activities) or promoting ongoing support when separated from family [17]. However, amid the current COVID-19 pandemic, LTC homes have restricted visitors (including family and friends) and group activities [18, 19] as a means of infection-control, which has had devastating impacts on social connection for residents [18, 20].

To our knowledge, there are no published reviews on the association between social connection and physical health among LTC home residents. To address this gap, the objective of this scoping review is to identify and summarize the existing research to address the question: what is known from the literature about the association between social connection and physical health outcomes for people living in LTC homes? We chose scoping review methodology to answer a broad research question by assessing published literature in which we anticipated a heterogeneous list of exposures and health outcomes, then to identify and report knowledge gaps [21–23].

Methods

This scoping review is a sub-analysis of a larger scoping review, initiated prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, to address a broad set of research questions on social connection among LTC home residents. A protocol for the larger scoping review has been published [14], and is briefly summarized below along with specifications for the present study, which represents the second publication stemming from the results of the larger scoping review. The results are being presented in multiple papers as a response to the volume of research studies located in our search as well as the immediate need to address knowledge gaps created by COVID-19. More specifically, the first publication was a direct response to the COVID-19 pandemic and research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; it focused on summarizing research on mental health impacts of social connection and potential strategies during COVID-19, which were knowledge gaps identified by our partner organisations (see section Consulting with stakeholders and knowledge users) [24]. A third publication is also in preparation, summarizing research reporting associations between LTC home- and community-level characteristics and resident social connection, which was also identified as an important knowledge gap.

The review followed the six-stage scoping review framework as developed by Arksey & O’Malley [25] and Levac et al. [22] and report results in accordance with the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews [23].

Searching for relevant literature

A literature search was conducted to identify relevant published journal articles that reported a quantitative measure of social connection among residents of LTC homes. Inclusion criteria specified settings described as LTC homes, nursing homes, or care homes. These terms were selected to reflect terminology differences between countries but also to reflect overlap and international consensus on the definition of nursing home [11]. In this paper, they are hereafter collectively referred to as LTC homes.

The following concepts were included as aspects of social connection: [26] social networks, the size and nature of the social network structure as well as characteristics of the social ties, and acknowledge that these networks provide opportunities for social support and social engagement [27]; social engagement, taking part in real-life activities with others [27, 28] as well as social disengagement [29]; social support, instrumental, emotional, appraisal, and informational help available [27] and social isolation, a lack of personal relationships [30]; social capital, the features of relationships that facilitate mutual benefits, such as interpersonal trust, reciprocity, and mutual aid [31]. The subjective experiences of loneliness [32], social connectedness [33], and perceived isolation [34] were also included.

For the current scoping review sub-analysis, studies reporting physical health outcomes were eligible for inclusion if they quantified any phenomenon that impacts the bodies’ function, form, or structure [35], including self-assessed health [36, 37]. Mental health outcomes were excluded as they were addressed in a separate publication [24]. Quality of life and well-being outcomes were also excluded [38]. Given the practical considerations of analyzing the volume of research anticipated in the larger scoping review and our original intent to map gaps in observational and interventional research, we did not include qualitative studies in this scoping review [14]. Although both observational and intervention studies were eligible for inclusion in the larger scoping review, we did not include studies that target social connection without also including a quantitative measure of social connection; for example, studies of interventions that address social connection but report only physical health outcomes would not be included in this review. See Table 1 for a summary of inclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Summary of the scoping review inclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | |

|---|---|

| Element | Inclusion details |

| Population | LTC home residents |

| Exposure | Social connection (including social networks, social engagement, social disengagement, social support, social isolation, social capital, loneliness, and social connectedness) |

| Comparator | Any |

| Outcome | Physical health |

The original search strategy was conducted by an information specialist who searched in MEDLINE(R) ALL (in Ovid, including Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily) and then translated into CINAHL (EBSCO), APA PsycINFO (Ovid), Scopus, Sociological Abstracts (Proquest), Embase and Embase Classic (Ovid), Emcare Nursing (Ovid) and AgeLine (EBSCO). Initial searches were conducted from the databases’ inception through to the date the search was executed (July 2019) and limited to the English language. The search strategies were updated with additions to acknowledge changes in the MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) indexing terms and the searches were executed again in January 2021 (see Additional file 1). Covidence (www.covidence.org) and Endnote were used for the review process and deduplication of database results [39].

Selecting studies

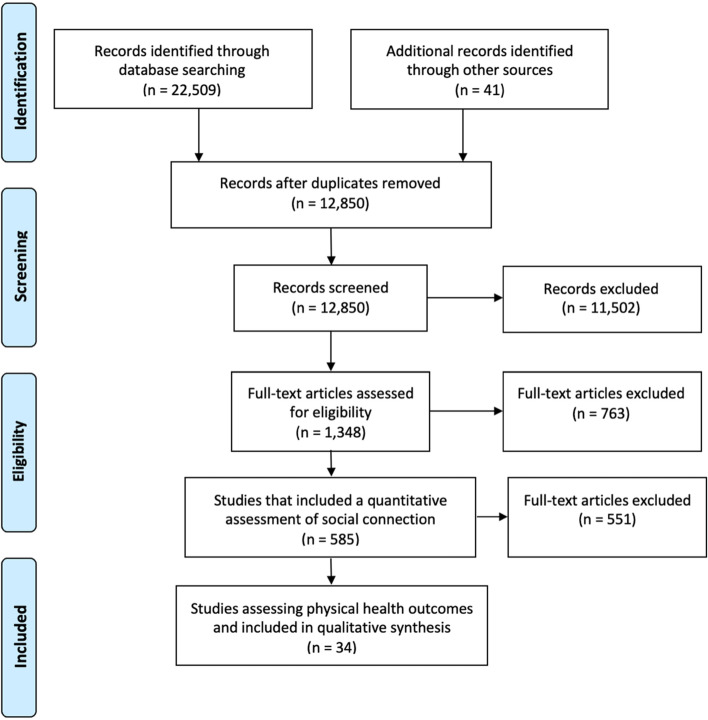

As part of the larger scoping review, to identify studies that reported a quantitative measure of social connection among residents of LTC homes, two reviewers independently screened article titles and abstracts and then full-text articles. Two reviewers also independently reviewed these articles to identify studies that reported associations between social connection and physical health outcomes (See Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram). In the case of disagreement, the reviewers discussed and resolved conflicts.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Diagram

Charting the data

A data abstraction form was created using Google forms and Google sheets to facilitate data extraction. Data charting was done independently and in duplicate. Given the nature of this review, no quality assessments of the studies were taken. Data were abstracted on article characteristics (e.g., country), objective, study design, setting (e.g., described as a nursing home or LTC home), sample (e.g., number of residents, mean age, sex distribution, inclusion/exclusion criteria related to cognition), measure of social connection, physical health outcome and a summary of study findings linking social connection and physical health outcomes.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

Study characteristics were summarized with descriptive statistics, as well as a narrative synthesis. For the narrative synthesis, we took a descriptive-analytical approach [25]. The study team postulated a theoretical model for the mechanisms underlying the association between social connection and physical health outcomes [6–10]. Study characteristics were then organized to describe patterns and explore potential factors contributing to direction and size of effect. The first author reported consolidated results back to the study team who reviewed the results, suggested refinements, and provided insights on the findings.

Consulting with stakeholders and knowledge users

The initial protocol [14] describes opportunities to present to and engage with LTC home residents, families, and staff, however, COVID-19 made in-person engagements impossible. Thus, for this review, we worked with partners from organizations who represent LTC knowledge users: Behavioural Supports Ontario Provincial Coordinating Office, Ontario Association of Residents’ Councils, and Family Councils Ontario. These members of our study team were involved in priority-setting (defining the review questions), analyzing data, interpreting and contextualizing the results, and coauthoring the current review.

Results

Study characteristics

As part of the larger scoping review [14], the search strategy yielded 22,509 titles, which reduced to 12,850 after deduplication. The list was distilled to 585 papers that quantified social connection in LTC residents, from which 34 papers were identified for the current analysis (see Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies are described in Additional file 2 and summarized in Tables 2, 3 and 4. Over two thirds (n = 23; 68%) of the studies were published in or after 2010 and just under half (n = 16; 47%) published in 2015 or later. The largest proportion of studies were from North America (n = 13; 38%), mostly the United States (n = 11; 32%). Just under two-thirds (n = 21; 62%) of the studies were cross-sectional and most of the remainder were cohort studies (n = 11; 32%). Among the eleven cohort studies, the majority (n = 8; 73%) assessed mortality as the outcome. Most of the studies described the setting as nursing homes (n = 27; 79%). The number of homes included in the studies ranged from 1 to 653, with a median of 6. The number of LTC residents included in the studies ranged from 40 to 30,055, with a median of 503.5. Mean resident age ranged from 68 to 87, with a median of 83.3. The proportion of females included in the studies ranged from 0 to 87% with a median of 71%.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in scoping review

| Study characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Total articles n (%) | 34 (100) |

| Year n (%) | |

| 1995–1999 | 2 (5.9) |

| 2000–2004 | 5 (14.7) |

| 2005–2009 | 4 (11.8) |

| 2010–2014 | 7 (20.6) |

| 2015+ | 16 (47.1) |

| Country n (%) | |

| United States | 11 (32.4) |

| Taiwan | 4 (11.8) |

| China | 4 (11.8) |

| Iceland | 2 (5.9) |

| Portugal | 2 (5.9) |

| Spain | 2 (5.9) |

| Italy | 2 (5.9) |

| Canada | 2 (5.9) |

| Othera | 12 (33) |

| Multipleb | 1 (2.9) |

| Study design n (%) | |

| Cross-sectional | 21 (61.8) |

| Cohort | 11 (32.4) |

| Ecologic | 1 (2.9) |

| Not Stated | 1 (2.9) |

| Study setting | |

| Nursing home | 27 (79.4) |

| Long-term care | 7 (20.6) |

| Number of institutions | |

| # of articles reporting n (%) | 29 (85.3) |

| Range | 1–653 |

| Median | 6 |

| Interquartile Range (IQR) | 42 |

| Number of residents (participants) | |

| # of articles reporting n (%) | 34 (100.0) |

| Range | 40–30,055 |

| Median | 503.5 |

| IQR | 1020.5 |

| Mean age of residents | |

| # of articles reporting n (%) | 24 (70.6) |

| Range | 68–87 |

| Median | 83.3 |

| IQR | 3.5 |

| Percentage of females | |

| # of articles reporting n (%) | 32 (94.1) |

| Range | 0–87 |

| Median | 70.6 |

| IQR | 14.4 |

aOther countries included Denmark, Lebanon, Iran, Hong Kong, Czech Republic, Finland, England, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Israel

bTotal greater than n=34 (100%) with one international study conducted in 8 countries

# number

Table 3.

Characteristics of social connection measures used in studies included in scoping review

| Social connection exposures characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Total articles n (%) | 34 (100) |

| Aspect of social connection | |

| Social engagement | 14 (41.2) |

| Social support | 10 (29.4) |

| Loneliness | 6 (17.6) |

| Social network | 2 (5.9) |

| Othera | 6 (17.6) |

| Instrument/Method | |

| Minimum Data Set | 12 (35.3) |

| UCLA Loneliness Scale | 3 (8.8) |

| Leisure Social Support Scale | 2 (5.9) |

| Otherb | 18 (52.9) |

aOther measures of social connection included social integration, social interaction, social participation, social relationships, social involvement, and social isolation

bOther instruments/methods used to assess social connection include the Duke Older Americans Resources and Services Procedures, the Hebrew Home Social Network Rating Scale, a survey, interviews, a Modified Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviours, behavioural observations, the Social Engagement Scale, the VAUX Social Support Questionnaire, a single question, the interRAI-LCTF, family visits, the Cohen-Mansfield measure of social network (1992), the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, a single-item question, the Loucks Social Network Score, the De Jong Gierveld Scale, the Social Provisions Scale, and the Personal Resource Questionnaire

Table 4.

Characteristics of physical health outcomes used in studies included in scoping review

| Physical health outcomes characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Total articles n (%) | 34 (100) |

| Physical health outcome categories | |

| Mortality | 8 (23.5) |

| Self-rated health | 6 (17.6) |

| Sleep and fatigue | 5 (14.7) |

| Nutrition and hydration | 5 (14.7) |

| Stress | 2 (5.9) |

| Frailty | 2 (5.9) |

| Othera | 6 (17.6) |

aOther measures of physical health included functional decline, successful aging, pain, self-feeding dependence over time, MRSA carriage, and multiple (including bladder or bowel incontinence, urinary tract infections, faecel impaction, little or no activity, bedfast residents, stage 1–4 ulcers, and falls)

Social connection and physical health outcomes in LTC home residents

The most common aspects of social connection assessed were social engagement, social support, and loneliness (see Table 3). The physical health outcomes were categorized as mortality, self-rated health, sleep and fatigue, nutrition and hydration, stress, frailty and other (see Table 4).

Mortality

Eight studies assessed the association between social connection and mortality. Seven studies reported higher social connection (social engagement or support) were associated with reduced risk of mortality [40–46]. The eighth study reported an unadjusted association between social network quality, but not size, with results suggesting this relationship may depend on sex and cognitive impairment, but the associations were not statistically significant in multivariable models [47].

Self-rated health

Six studies assessed the association between social connection and self-rated health. One study found that loneliness was associated with poor health among women but not men [48]. Another found that, when considering social engagement within the home, outside the home (family and friends), and relatives within the facility, only infrequent contacts within the LTC home were associated with worse health [49]. Two studies used path analysis to consider the role of social support in predicting self-rated health status [50, 51]. Another two studies found no statistically significant association between social connection and self-rated health [52, 53].

Sleep and fatigue

Five studies assessed the association between social connection and sleep and fatigue. Two studies reported social support was inversely associated with sleep problems [54, 55] whereas another found social network (but not social support) was positively associated with fatigue [56]. Two studies reported social engagement was associated with less daytime sleep [57, 58].

Nutrition and hydration

Five studies assessed the association between social connection and nutrition and hydration. Results from the studies varied. One study found the association between loneliness and risk of malnutrition or being malnourished was no longer statistically significant after adjusting for appetite, eating difficulties due to oral health problems, symptoms of depression and functional status [59]. Similarly, another study found the association between social engagement and energy intake was no longer statistically significant after adjusting for eating challenges [60]. One study found a higher prevalence of low social engagement among underweight residents (BMI < 20) [61]. Another study found that differences in social isolation and loneliness scores according to nutrition status groups (i.e. malnutrition, at risk of malnutrition, and satisfactory nutritional status) were not statistically significant [62]. One study reported low social engagement was associated with dehydration but not weight loss [63]. Another study found low social engagement predicted increased self-feeding dependence [64].

Stress

Two studies assessed the association between social support and stress; in the first, social support was associated with acute (but not chronic) stress [65] and, in the second, emotional support was inversely associated with stress but instrumental support was not [66].

Frailty

Two studies assessed the association between loneliness and frailty; one study reported loneliness was associated with frailty [67] and another study suggested the relationship may be mediated by activity engagement [68].

Other physical health outcomes

Six studies assessed a range of other physical health outcomes. An ecological study found an association between social engagement and reduced MRSA transmission [69]. Another study tested the association between social engagement and a range of health outcomes and quality indicators (including bladder and bowel health, bedfast residents, pressure ulcers, and falls); low social engagement was associated with reduced risk of an indwelling catheter but increased risk of faecal impaction and bedfast state [63]. Another study found social engagement was associated with functional decline, but only in unadjusted analysis [70]. Social support was not associated with successful aging [71] or pain [72] and social engagement was not associated with urinary incontinence [73].

Discussion

This scoping review of published research identified 34 studies that assessed the association between social connection and physical health in LTC residents. The studies reported a range of physical health outcomes, most commonly mortality, self-rated health, sleep, fatigue, nutrition, hydration, stress, and frailty. While the association between social and physical health has been studied for decades [74], research specific to LTC homes has received less attention [12]. To our knowledge, this review is the first to highlight research on the physical health outcomes of social connection in this population.

When considered together, the studies included in this review highlighted several knowledge gaps. First, aside from the studies of mortality, almost all (n = 21; 62%) the studies were cross-sectional, making temporal relationships impossible to determine for some outcomes; while it is possible that social connection impacts health, the impact of some of these same measures of health status (e.g., pain [75] and sleep [76]) on social connection have also been reported. Second, while the cohort studies identified in this review suggested consistent evidence of a potential protective effect for social connection on mortality among LTC residents, many studies did not test the potential mechanisms underlying the association between social connection. In particular, there was a lack of analysis on the potential biological [6, 7] and behavioural [8, 9] underpinnings that may explain the physical health outcomes associated with the multiple aspects of social connection being studied. The results of the current review, taken in context with a recent review on social connection and mental health outcomes in this population [24], suggest mechanisms consistent with previously proposed models [4, 77], but which highlight specific psychological factors (e.g., stress, depression) and lifestyle (e.g., nutrition, sleep) which warrant further research in this population. For example, with respect to the latter, addressing social connection as a means to improving nutritional status – either through individual-delivered interventions [78] or addressing aspects of the LTC home mealtime environment [79] – has been investigated. Third, few studies stratified results to compare populations within LTC homes (e.g., by sex or gender [47–49, 59], cognition [

While we acknowledge the policy and clinical practice implications from this scoping review are limited [21], our study identified a body of research on the health impacts of social connection that extends specifically to LTC residents. Set against the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic - and extending beyond it - our findings underscore how social connection is essential in LTC homes [85], the vital role of essential/designated care partners (i.e., family and friends) [86, 87] and the importance of integrating LTC residents’ social connection as a predictor of physical and mental health [24] and a measure of quality of life [88] and care [89, 90].

Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review of research assessing the association between social connection and physical health specifically among LTC residents. We have highlighted knowledge gaps and identified opportunities for future research, however, the results must be interpreted in context with limitations. First, this is a scoping review [22, 23, 25] and the objective and methods did not include an examination of the quality of evidence; the implications of the results are primarily to guide future research in this area. Second, only English language studies were included and so the geographical distribution of studies may reflect this eligibility criterion and limit the generalizability of the findings [91, 92]. Third, inconsistent use of terminology related to the main concepts of the initial literature search (i.e., LTC homes [11] and aspects of social connection [31]) may have contributed to some research papers being omitted from the review. Fourth, the literature search only included intervention studies which reported social connection outcomes [24], thereby precluding interventions studies from this review.

Conclusions

This study identified and summarized published research testing the association between social connection and physical health for people living in LTC homes. While a diverse range of outcomes were assessed, findings generally supported the positive association between social connection and physical health. Still, further research is needed to consider the influence of social connection on health trajectories, compare populations within LTC homes, integrate multiple aspects of social connection, and assess the distinct mechanisms through which these aspects of social connection might influence health in this population.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2. Study Characteristics.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to Ellen Snowball, Omar Farhat, and Jenny Jing for their assistance in selecting the studies and charting the data.

Abbreviations

- LTC

Long-Term Care

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- MDS

Minimum Data Set

- MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus

Authors’ contributions

KL, KSM, KA, AI, JBa, DHC, CE, MB, DL, JLG and JBe all contributed to the design and concept of the study, interpretation of the data, and writing the manuscript. JBa developed and conducted the literature search. KL and JBe designed the study, drafted and revised the manuscript and have agreed to be accountable for any questions arising from the work. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a “Knowledge Synthesis: COVID-19 in Mental Health and Substance Use” operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). JB, AI, and KM are supported by the Walter & Maria Schroeder Institute for Brain Innovation and Recovery. They are also members of the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA). The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study or methods, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Federal, Provincial and Territorial Advisory Committee on Population Health. Toward a healthy future: Second report on the health of Canadians.Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada [Internet]; 1999. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/report-rapport/toward/pdf/toward_a_healthy_english.PDF.

- 2.Federal, Provincial and Territorial Advisory Committee on Population Health. Strategies for population health, investing in the health of Canadians. Ottawa: Health Canada; 1994. Available from: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.825914/publication.htm.

- 3.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. Brayne C, editor. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102(13):1009–1016. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loucks EB, Sullivan LM, D’Agostino RB, Larson MG, Berkman LF, Benjamin EJ. Social networks and inflammatory markers in the Framingham heart study. J Biosoc Sci. 2006;38(6):835–842. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenberger NI, Taylor SE, Gable SL, Hilmert CJ, Lieberman MD. Neural pathways link social support to attenuated neuroendocrine stress responses. Neuroimage. 2007;35(4):1601–1612. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emmons KM, Barbeau EM, Gutheil C, Stryker JE, Stoddard AM. Social influences, social context, and health behaviors among working-class, multi-ethnic adults. Heal Educ Behav. 2007;34(2):315–334. doi: 10.1177/1090198106288011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson HS, Littles M, Jacob S, Coker C. Posttreatment breast cancer surveillance and follow-up care experiences of breast cancer survivors of African descent: an exploratory qualitative study. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(6):478–487. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alfonso V, Geller J, Bermbach N, Drummond A, Montaner JSG. Becoming a “treatment success”: what helps and what hinders patients from achieving and sustaining undetectable viral loads. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20(5):326–334. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanford AM, Orrell M, Tolson D, Abbatecola AM, Arai H, Bauer JM, et al. An international definition for “nursing home.”. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(3):181–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Victor CR. Loneliness in care homes: a neglected area of research? Aging Health. 2012;8(6):637–646. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brimelow RE, Wollin JA. Loneliness in old age: interventions to curb loneliness in long-term care facilities. Act adapt. Aging. 2017;41(4):301–315. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bethell J, Babineau J, Iaboni A, Green R, Cuaresma-Canlas R, Karunananthan R, et al. Social integration and loneliness among long-term care home residents: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):1–6. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Center for Health Statistics V and HS . Long-term care providers and services users in the United States, 2015–2016, analytical and epidemiological studies. 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ontario Long Term Care Association . This is long-term care 2018, 2019. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puurveen G, Baumbusch J, Gandhi P. From family involvement to family inclusion in nursing home settings: a critical interpretive synthesis. J Fam Nurs. 2018;24(1):60–85. doi: 10.1177/1074840718754314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simard J, Volicer L. Loneliness and isolation in long-term care and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:966–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Span P. Just what older people didn’t need: more isolation: The New York Times; 2020. [cited 2020 May 30]; Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/13/health/coronavirus-elderly-isolation-loneliness.html

- 20.Chu CH, Donato-Woodger S, Dainton CJ. Competing crises: COVID-19 countermeasures and social isolation among older adults in long-term care. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(10):2456–2459. doi: 10.1111/jan.14467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bethell J, Aelick K, Babineau J, Bretzlaff M, Edwards C, Gibson JL, et al. Social connection in long-term care homes: a scoping review of published research on the mental health impacts and potential strategies during COVID-19. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22:228–237.e25. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donovan NJ, Blazer D. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: review and commentary of a national academies report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(12):1233–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glass TA, Mendes De Leon C, Marottoli RA, Berkman LF. Population based study of social and productive activities as predictors of survival among elderly Americans. Br Med J. 1999;319(7208):478–483. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7208.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bassuk SS, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community- dwelling elderly persons. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(3):165–173. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machielse A. The heterogeneity of socially isolated older adults: a social isolation typology. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2015;58(4):338–356. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2015.1007258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leedahl SN, Sellon A, Chapin RK. Assessment of multiple constructs of social integration for older adults living in nursing homes. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2018;61(5):526–548. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2018.1451938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Jong GJ, van Tilburg T. The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur J Ageing. 2010;7(2):121–130. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Rourke HM, Sidani S. Definition, determinants, and outcomes of social connectedness for older adults: a scoping review. J Gerontol Nurs. 2017;43:43–52. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20170223-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(1):31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bair-Merritt MH, Blackstone M, Feudtner C. Physical health outcomes of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):278–290. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnittker J, Bacak V. The increasing predictive validity of self-rated health. PLoS One. 2014;9(1) [cited 2020 Aug 15]. Available from: /record/2014-09665-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Cohen GD, Perlstein S, Chapline J, Kelly J, Firth KM, Simmens S. The impact of professionally conducted cultural programs on the physical health, mental health, and social functioning of older adults. Gerontologist. 2006;46(6):726–734. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.6.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carr AJ, Gibson B, Robinson PG. Measuring quality of life is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? Br Med J. 2001;322:1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bramer WM, Giustini D, De Jong GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in endnote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(3):240–243. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drageset J, Eide GE, Kirkevold M, Ranhoff AH. Emotional loneliness is associated with mortality among mentally intact nursing home residents with and without cancer: a five-year follow-up study. J Clin Nurs. 2012;22(1–2):106–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hjaltadóttir I, Rahm Hallberg I, Kristensson Ekwall A, Nyberg P. Predicting mortality of residents at admission to nursing home: a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(86):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kiely DK, Simon SE, Jones RN, Morris JN. The protective effect of social engagement on mortality in long-term care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1367–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiely DK, Flacker JM. The protective effect of social engagement on 1-year mortality in a long-stay nursing home population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:472–478. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vetrano DL, Collamati A, Magnavita N, Sowa A, Topinkova E, Finne-Soveri H, et al. Health determinants and survival in nursing home residents in Europe: results from the SHELTER study. Maturitas. 2018;107:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fehnel CR, Lee Y, Wendell LC, Thompson BB, Potter S, Mor V. Post-acute care data for predicting readmission after ischemic stroke: a nationwide ohort analysis using the minimum data set. J Am Hear Assoc. 2015;e002145:1–9. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pastor-Barriuso R, Padrón-Monedero A, Parra-Ramírez LM, García López FJ, Damián J. Social engagement within the facility increased life expectancy in nursing home residents: a follow-up study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01876-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Lipson S, Werner P. Predictors of mortality in nursing home residents. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(4):273–280. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alarcão V, Madeira T, Peixoto-Plácido C, SousaSantos N, Fernandes E, Nicola P, et al. Gender differences in psychosocial determinants of self-perceived health among Portuguese older adults in nursing homes. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(8):1049–1056. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1471583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Damián J, Pastor-Barriuso R, Valderrama-Gama E. Factors associated with self-rated health in older people living in institutions. BMC Geriatr. 2008;8(5):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Y-B, Xue L-L, Xue H-P, Hou P. Health literacy, self-care agency, health status and social support among elderly Chinese nursing home residents. Health Educ J. 2018;77(3):303–311. doi: 10.1177/0017896917739777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zurakowski TL. The social environment of nursing homes and the health of older residents. Holist. Nurs Pract. 2000;14(4):12–23. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cott CA, Fox MT. Health and happiness for elderly institutionalized Canadians. Can J Aging. 2001;20(4):535. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keister KJ. Predictors of self-assessed health, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in nursing home residents at week 1 postrelocation. J Aging Health. 2006;18(5):722–742. doi: 10.1177/0898264306293265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu X, Hu Z, Nie Y, Zhu T, Kaminga AC, Yu Y, et al. The prevalence of poor sleep quality and associated risk factors among Chinese elderly adults in nursing homes: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papi S, Karimi Z, Ghaed Amini Harooni G, Nazarpour A, Shahry P. Determining the prevalence of sleep disorder and its predictors among elderly residents of nursing homes in Ahvaz City in 2017. Iran J Ageing. 2019;Special Issue(13):576–587. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cho J, Martin P, Margrett J, Macdonald M, Johnson MA, Poon LW. Multidimensional predictors of fatigue among octogenarians and centenarians. Gerontology. 2012;58:249–257. doi: 10.1159/000332214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li J, Chang Y-P, Porock D. Factors associated with daytime sleep in nursing home residents. Res Aging. 2015;37(1):103–117. doi: 10.1177/0164027514537081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin JL, Webber AP, Alam T, Harker JO, Josephson KR, Alessi CA. Daytime sleeping, sleep disturbance, and circadian rhythms in the nursing home. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:121–129. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192483.35555.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Madeira T, Peixoto-Plácido C, Sousa-Santos N, Santos O, Alarcão V, Goulão B, et al. Malnutrition among older adults living in Portuguese nursing homes: the PEN-3S study. Public Health Nutr. 2018;22(3):486–497. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018002318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morrison-Koechl J, Wu SA, Slaughter SE, Lengyel CO, Carrier N, Keller HH. Hungry for more: Low resident social engagement is indirectly associated with poor energy intake and mealtime experience in long-term care homes. Appetite. 2021;159:105044. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Beck AM, Ovesen L. Influence of social engagement and dining location on nutritional intake and body mass index of old nursing home residents. J Nutr Elder. 2003, 2003;22(4) [cited 2020 Aug 12]. Available from: http://www.haworthpress.com/store/product.asp?sku=J052.

- 62.El Zoghbi M, Boulos C, Saleh N, Salameh P, Awada S, Rachidi S, et al. Prevalence of malnutrition and its correlates in older adults living in long stay institutions situated in Beirut, Lebanon. J Res Health Sci. 2014;14(1):11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hjaltadóttir I, Ekwall AK, Hallberg IR. Quality of care in Icelandic nursing homes measured with minimum data set quality indicators: retrospective analysis of nursing home data over 7 years. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:1342–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Palese A, Grassetti L, Zuttion R, Ferrario B, Ponta S, Achil I, et al. Self-feeding dependence incidence and predictors among nursing home residents: findings from a 5 year retrospective regional study. Nurs Health Sci. 2019;21:297–306. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chang L-C. Reexamining the relationship between leisure and stress among older adults. J Leis Res. 2015;47:3. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang LC. Is social support always related to stress reduction in nursing home residents?: a study in leisure contexts. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2018;11(4):174–180. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20180502-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tse MMY, Lai C, Lui JYW, Kwong E, Yeung SY. Frailty, pain and psychological variables among older adults living in Hong Kong nursing homes: can we do better to address multimorbidities? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2016;23:303–311. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhao MM, Gao JM, Li M, Wang K. Relationship between loneliness and frailty among older adults in nursing homes: the mediating role of activity engagement. JAMDA. 2019;20:759–764. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murphy CR, Quan V, Kim D, Peterson E, Whealon M, Tan G, et al. Nursing home characteristics associated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) burden and transmission. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yeh K-P, Lin M-H, Liu L-K, Chen L-Y, Peng L-N, Chen L-K. Functional decline and mortality in long-term care settings: static and dynamic approach. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;5:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jcgg.2013.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu M, Yang Y, Zhang D, Sun Y, Hui X, Zhang J, et al. Prevalence and related factors of successful aging among Chinese rural elders living in nursing homes. Eur J Ageing. 2017;14:419–428. doi: 10.1007/s10433-017-0423-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weiner DK, Peterson BL, Logue P, Keefe FJ. Predictors of pain self-report in nursing home residents. Aging Clin Exp Res. 1998;10(5):411–420. doi: 10.1007/BF03339888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen Y-M, Hwang S-J, Chen L-K, Chen D-Y, Lan C-F. Urinary incontinence among institutionalized oldest old Chinese men in Taiwan. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28:335–338. doi: 10.1002/nau.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance and mortality: a nine year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109:186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tse M, Leung R, Ho S. Pain and psychological well-being of older persons living in nursing homes: an exploratory study in planning patient-centred intervention. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(2):312–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garms-Homolovà V, Flick U, Röhnsch G. Sleep disorders and activities in long term care facilities - a vicious cycle? J Health Psychol. 2010;15(5):744–754. doi: 10.1177/1359105310368185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for CVD: implications for evidence-based patient care and scientific inquiry. Heart. 2016;102:987–989. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maltais M, Rolland Y, Haÿ PE, Armaingaud D, Cestac P, Rouch L, et al. The effect of exercise and social activity interventions on nutritional status in older adults with dementia living in nursing homes: a randomised controlled trial. J Nutr Heal Aging. 2018;22(7):824–828. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Slaughter SE, Morrison-Koechl JM, Chaudhury H, Lengyel CO, Carrier N, Keller HH. The association of eating challenges with energy intake is moderated by the mealtime environment in residential care homes. Int. Psychogeriatrics. 2020;32(7):863–873. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine . Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: opportunities for the health care system. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ontario Long Term Care Association. This is long-term care. Toronto; 2019. [cited 2021 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.oltca.com/OLTCA/Documents/Reports/TILTC2019web.pdf

- 82.Budgett J, Brown A, Daley S, Page TE, Banerjee S, Livingston G, et al. The social functioning in dementia scale (SF-DEM): exploratory factor analysis and psychometric properties in mild, moderate, and severe dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit. 2019;11:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sommerlad A, Singleton D, Jones R, Banerjee S, Livingston G. Development of an instrument to assess social functioning in dementia: the social functioning in dementia scale (SF-DEM) Alzheimer’s Dement Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit. 2017;7:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Office for National Statistics. Measuring loneliness : guidance for use of the national indicators on surveys: Office for National Statistics; 2018. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/methodologies/measuringlonelinessguidanceforuseofthenationalindicatorsonsurveys

- 85.Bethell J, O'Rourke HM, Eagleson H, Gaetano D, Hykaway W, McAiney C. Social connection is essential in long-term care homes: considerations during COVID-19 and beyond. Can Geriatr J. 2021;24(2):151–153. doi: 10.5770/cgj.24.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Puurveen G, Baumbusch J, Gandhi P. From family involvement to family inclusion in nursing home settings: a critical interpretive synthesis. J Fam Nurs. 2018;24(1):60–85. doi: 10.1177/1074840718754314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Re-integration of family caregivers as essential partners in care in a time of COVID-19. Ottawa; 2020. [cited 2021 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/docs/default-source/itr/tools-and-resources/bt-re-integration-of-family-caregivers-as-essential-partners-covid-19-e.pdf

- 88.Bradshaw SA, Playford ED, Riazi A. Living well in care homes: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Age Ageing. 2012;41(4):429–440. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sion KYJ, Verbeek H, Zwakhalen SMG, Odekerken-Schröder G, Schols JMGA, Hamers JPH. Themes related to experienced quality of care in nursing homes from the resident’s perspective: a systematic literature review and thematic synthesis. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020. 10.1177/2333721420931964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Calkins MP. From research to application: supportive and therapeutic environments for people living with dementia. Gerontologist. 2018;58(suppl_1):S114–S128. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jones D. A WEIRD view of human nature skews psychologists’ studies. Am Assoc Adv Sci. 2010;328(5986):1627. doi: 10.1126/science.328.5986.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav Brain Sci. 2010:1–75 [cited 2020 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.psych.ubc.ca/henrich/home.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 2. Study Characteristics.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.