Abstract

The G (VP7) and P (VP4) serotype distribution of Brazilian porcine rotaviruses was determined using reverse transcription-PCR genotyping methods. Common porcine G types G3, G4, and G5 were detected in combination with P types [6] and [7]. The detection of nonporcine G types and unusual G-P combinations and the characterization of an atypical virus indicated that interspecies transmission may contribute to the genetic diversity of porcine rotaviruses.

Rotaviruses are a major cause of acute viral diarrhea in both humans and animals (13). Group A rotaviruses have two outer capsid proteins, VP7 and VP4, that are considered independent neutralization antigens and are encoded by different genomic RNA segments. The serotype specificity of VP7 is designated by the prefix G, and 14 G serotypes are recognized. These correlate with all known G genotypes, determined from sequence analysis of VP7 genes. The serotype specificity of VP4 is designated by the prefix P, and there are 10 P serotypes described. However, because of the difficulties with characterization of P serotypes, P genotypes have been determined from genetic analysis of VP4 genes, and 20 genetically distinct P types have been described for rotaviruses of humans and animals. These are indicated by including the genotype number in brackets (7). Serotypic and genotypic characterization of rotavirus strains is important to define the extent of diversity in circulating strains. Comparisons of strains from human and animal origins may provide insights into the interspecies evolution of this virus.

Studies in several countries have identified at least four main G serotypes of porcine rotavirus, G3 (Po/CRW-8 type), G4 (Po/Gottfried type), G5 (Po/OSU type), and G11 (Po/YM type) (10), and two main P serotypes [genotypes], P2B[6,Gott] and P9[7]. In Brazil, G5 rotaviruses have recently been found as common human pathogens, but only a limited number of porcine samples have been studied for their G and P type specificities (18). In this report, we determined the serotype distribution of porcine rotavirus strains obtained in three states of the southern region of Brazil. In addition, an atypical strain was characterized to determine its relatedness to a human rotavirus strain.

One hundred sixty-seven porcine stool specimens were collected from 52 small individually owned farms in the states of Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul. Samples were obtained from pigs 1 to 60 days old, with or without diarrhea, between June 1995 and October 1997. The piglets were raised in confinement without any contact with animals from other species. Fecal material was collected in plastic bags, directly from the rectum; maintained on ice during transport to the lab; and kept frozen at −20°C until analysis. Samples were subjected to enzyme immunoassay (EIARA-FIOCRUZ) and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with standard silver staining for rotavirus identification (17). Fifty-nine samples (35.3%) were positive for rotavirus by one or both techniques. Positive samples were subjected to G and P genotyping by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), with primers specific for porcine, bovine, and human rotavirus genotypes (8, 10, 11, 12). The complete geographic and epidemiologic information on these samples will be presented in a separate paper. Since G and P types were determined by genotyping methods, these are indicated by numbers enclosed in brackets.

PCR results showed a high diversity of G and P types (Table 1). Samples were classified into common porcine G genotypes G[3], G[4], and G[5], with the majority of samples (37.2%) belonging to genotype G[5]. Genotype G[11], commonly found in porcine samples in other countries (2), was not found in this survey. G[5] strains are common human pathogens in Brazil, usually in combination with human P1A[8] specificity (9, 18). As expected, P1A[8] strains were not detected; instead, for G[5] samples, six had P[6,Gott] specificity, one had P[6,M37] specificity, six belonged to the P[7] genotype, and six belonged to mixed P genotypes. P[6] genotypes were designated P[6,Gott] (porcine specific) or P[6,M37] (human specific). They represent distinct subtypes P2A and P2B, respectively (11, 18). Therefore, our RT-PCR assay is capable of differentiating subtypes, which might also be important in assessing interspecies transmission. Our results suggests the possibility of exchange of VP4 genes between animal and human rotaviruses. Twelve samples showed mixed P[6] and P[7] genotypes (Table 1). These results support the suggestion that Brazilian G[5] porcine samples with human P types could be the result of reassortment between human and porcine rotaviruses. Genotyping results highlighted some unusual samples: two samples with G[10] specificity, three G[9] samples, and two samples with mixed genotypes, one of G[4][9] and one of G[5][10]. G[10] rotaviruses have not been previously isolated from pigs in Brazil, despite the fact that they are common bovine pathogens in Brazil (3). Although P[6,Gott] rotaviruses have been reported previously in Brazil (18), the combination P[6,Gott]G[9] has not been observed. The three G[9] samples displayed different P specificities: P[6,Gott], P[7], and mixed P[6,Gott][M37]. This mixed P type was also observed with the sample showing G[4][9] specificity.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of rotavirus G and P types among porcine samples in the southern region of Brazila

| G genotype | No. of samples with P genotype:

|

No. P neg | No. total | % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P[6G] | P[6M] | P[7] | P[6G][6M] | P[6G][7] | P[6M][7] | P[6G][6M][7] | ||||

| G[3] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 8.5 | ||||

| G[4] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 8.5 | |||||

| G[5] | 6 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 22 | 37.3 | |

| G[9] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5.1 | |||||

| G[10] | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3.4 | ||||||

| G[4][9] | 1 | 1 | 1.7 | |||||||

| G[5][10] | 1 | 1 | 1.7 | |||||||

| G neg | 5 | 1 | 14 | 20 | 33.9 | |||||

| Total | 14 | 2 | 23 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 59 | 100.0 |

6G, 6, Gottfried-like; 6M, 6, M37-like; neg, negative.

The atypical porcine rotavirus displaying P[6,Gott][M37]G[9] specificity, ICB2185, was further characterized by sequencing of its VP7 gene. This unusual combination of G and P types raised the possibility of interspecies transmission from humans. This sample was identified in a piglet with diarrhea, belonged to group A, displayed a “long” electropherotype, and was classified into subgroup I by enzyme immunoassay. This strain was nontypeable by RT-PCR using animal G-type-specific primers (10), although genotyping with human G-type-specific primers (12) resulted in a 306-bp product, suggesting a G[9]-like VP7. However, when tested in a nested PCR with a second set of primers, including a G9-specific primer derived from the human rotavirus 116E, isolated in India (6), the sample failed to generate a G[9] product. Therefore, both strands of the full-length VP7 PCR product were sequenced with the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems) in an ABI-Prism 377 DNA sequencer. The VP7 gene was found to be 1,062 bp in length and to encode a polypeptide of 326 amino acids (aa).

The deduced amino acid sequence of ICB2185 was compared with those from standard viruses, representing all 14 G types (Table 2). The VP7 of ICB2185 exhibited over 89% amino acid identity with the porcine G4 strain Gottfried, the human G4 strain ST3, and the atypical human rotavirus strain M3014, identified in Australia, whose G type remains undefined (15). Identity with other G types was between 60.0 and 78.6%. Strains of the same G serotype generally share >91% VP7 amino acid identity (13, 15). Despite the high VP7 identity with G4 strains and the positive G[9] genotyping result, ICB2185 did not react with a G4-specific primer in nested PCR or with G4-specific (Serotec-Rota-MA [20, 23] and ST3:1 [5]) or G9-specific (F45:1 and F45:8 [14]) monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) in a serotyping enzyme immunoassay, indicating that this strain did not belong to serotype G4 or G9. Amino acid identity of only 76.8 to 78.3% was found between ICB2185 and human G9 strains, 116E, F45, and WI61. The latter strain was used to derive the sequence of the G9-specific primer used in the work of Gouvea et al. (12). Nucleotide sequence analysis of ICB2185 showed that, at the G9-specific primer binding position (757 to 776), only two mismatches were present (positions 769 and 775) while, at the G4-specific primer binding position, nine mismatches were found. At the site where the 116E-specific G9 primer binds (147 to 131), there are six mismatches, including the four nucleotides at the 5′ end (data not shown). This may explain the contradictory results of the two G-typing PCR methods above. In summary, sequence analysis indicated that the VP7 gene of ICB2185 was G4-like but contained a G9-specific primer binding site. Sequence variation at VP7 typing primer binding sites has been documented previously (1), leading to incorrect typing results. Improvement in RT-PCR-based typing methods may require the incorporation of degenerate primers that take into account the extent of natural sequence variation. Alternatively, hybridization using G-type-specific probes may be used to validate typing results.

TABLE 2.

Amino acid identity of VP7 deduced sequence of strain ICB2185 with rotaviruses of different G serotypes

| Strain | Species of origin | G type | % Identity |

|---|---|---|---|

| M3014 | Human | G? | 90.2 |

| Wa | Human | G1 | 78.6 |

| S2 | Human | G2 | 70.0 |

| HCR3 | Human | G3 | 78.6 |

| Gottfried | Porcine | G4 | 90.5 |

| ST3 | Human | G4 | 89.3 |

| OSU | Porcine | G5 | 74.3 |

| NCDV | Bovine | G6 | 75.8 |

| Ch2 | Chicken | G7 | 60.0 |

| B37 | Human | G8 | 71.6 |

| 116E | Human | G9 | 76.8 |

| F45 | Human | G9 | 77.7 |

| WI61 | Human | G9 | 78.3 |

| B223 | Bovine | G10 | 76.5 |

| YM | Porcine | G11 | 74.9 |

| L26 | Human | G12 | 72.5 |

| L338 | Equine | G13 | 73.1 |

| FI23 | Equine | G14 | 76.1 |

Amino acid sequences of the antigenic epitope regions A (aa 87 to 101), B (aa 142 to 152), C (aa 208 to 221), and F (aa 238 to 242) of VP7 are highly conserved between strains of the same serotype (14). Comparison of the amino acid sequences of these regions between ICB2185 and strains belonging to other serotypes showed that ICB2185 exhibited only 86.7% identity to region A of Gottfried (G4) (data not shown). Region B showed a maximum identity of only 63.6% with the two G4 strains, Gottfried and ST3, and with M3014. Region C showed 85.7% identity with M3014, and region F was identical to Gottfried. These data could explain why ICB2185 did not react with G4- and G9-specific MAbs. ST3:1 selects variants in, and presumably binds to, region A (4), while F45:1 and F45:8 map to region C and region A, respectively (14). Since these regions are divergent between ICB2185 and the prototype G4 and G9 strains (data not shown), it may explain the nonreactivity of the MAbs tested.

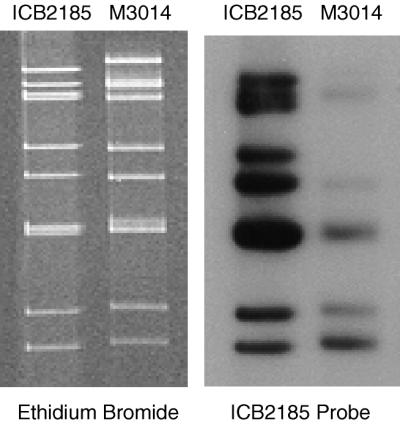

As ICB2185 showed high VP7 identity to the human strain M3014, it is possible that ICB2185 was derived from interspecies reassortment between human and porcine rotaviruses. To investigate this possibility, Northern hybridization was carried out using a whole-genome probe of ICB2185. The probe was prepared by labeling purified RNA with digoxigenin (DIG) by chemical linking of DIG to RNA using the DIG Chem-Link reagent (Roche Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). Northern hybridization under stringent conditions (50°C, 50% formamide, 5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate]) and detection of bound probe using anti-DIG antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Roche Biochemicals) and the chemiluminescent substrate CDP-Star (Roche Biochemicals) were carried out as previously described (16). Figure 1 shows that minimal homology existed between both viruses, as expected for viruses from different species. Homology between ICB2185 and M3014 in gene 7, 8, or 9 is probably due to the VP7 gene, as they share 84.8% identity in nucleotide sequence. However, the limited overall homology suggests that, if they are related, these viruses may not share a recent common ancestor. This is also seen in the comparatively low VP7 nucleotide sequence identity compared to higher amino acid sequence identity.

FIG. 1.

Northern hybridization analysis of ICB2185 and M3014 RNA using ICB2185-derived DIG-labeled total-genome probe.

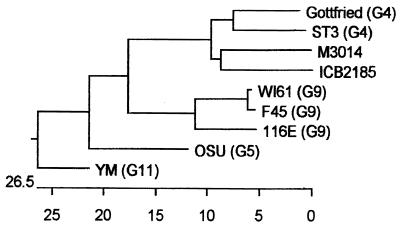

Although not exhibiting significant overall genome relatedness, the VP7 proteins of ICB2185 and M3014 shared several characteristics: both viruses exhibited the G[9] genotype by RT-PCR, these proteins were similar to but distinct from those from prototype G4 viruses, and they did not react with G4- or G9-specific MAbs. In a recent study of the phylogenetic relationships of VP7 sequences from 207 rotavirus strains, M3014 was placed in a distinct branch closely related to G4 viruses (19). Phylogenetic analysis shows that ICB2185 belongs to the same branch as M3014 (Fig. 2). Further studies using conventional seroneutralization techniques are needed to show if ICB2185 and M3014 constitute a subtype of G4 rotaviruses or a new G serotype.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of the VP7 gene sequences of porcine (ICB2185, Gottfried, OSU, and YM) and human (M3014, ST3, 116E, F45, and WI61) rotavirus strains. The dendrogram was constructed by the Clustal method using the Lasergene sequence analysis software. The length of each pair of branches represents the distance between sequence pairs, while the units at the bottom of the tree indicate the number of substitution events.

The results presented in this study demonstrate that serotypic and genotypic characterization of porcine rotavirus strains is important to define the extent of diversity in circulating strains. Such characterization could be facilitated by the use of appropriate MAbs in enzyme immunoassay in the first instance, followed by genetic methods (RT-PCR and hybridization) for samples not typed by enzyme immunoassay. Comparisons with human viruses may provide insights into the interspecies evolution of this virus. This is especially important in Brazil, where a high proportion of serotypes previously thought to be restricted to animal populations (e.g., G5) have been identified in children (2, 9, 21, 22).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the ICB2185 VP7 gene has been deposited in GenBank under the accession no. AF192267.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by FAPESP, São Paulo, Brazil, and the Royal Children's Hospital Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adah M I, Rohwedder A, Olayede O D, Werchau H. Nigerian rotavirus serotype G8 could not be typed by PCR due to nucleotide mutation at the 3′ end of the primer binding site. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1881–1887. doi: 10.1007/s007050050206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohl E H, Theil K W, Saif L J. Isolation and serotyping of porcine rotaviruses and antigenic comparison with other rotaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:105–111. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.2.105-111.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brito W M E D, Munford V, Rácz M L. Antigenic and molecular characterization of bovine rotavirus from State of Goiás. Virus Rev Res. 1998;3:57–58. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coulson B S, Kirkwood C D, Masendycz P J, Bishop R F, Gerna G. Amino acids involved in distinguishing between monotypes of rotavirus G serotypes 2 and 4. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:239–245. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-2-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulson B S, Unicomb L E, Pitson G E, Bishop R F. Simple and specific enzyme immunoassay using monoclonal antibodies for serotyping human rotaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:509–515. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.3.509-515.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das B K, Gentsch J R, Cicirello H G, Woods P A, Gupta A, Ramachandran M, Kumar R, Bhan M K, Glass R I. Characterization of rotavirus strain from newborns in New Delhi, India. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1820–1822. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1820-1822.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estes M K. Rotaviruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1625–1655. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gentsch J R, Glass R I, Woods P, Gouvea V, Gorziglia M, Flores J, Bimal K D, Bhan M K. Identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1365-1373.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gouvea V, Castro L, Timenetsky M C, Greenberg H B, Santos N. Rotavirus serotype G5 associated with diarrhea in Brazilian children. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1408–1409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1408-1409.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gouvea V, Santos N, Timenetsky M C. Identification of bovine and porcine rotavirus G types by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1338–1340. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1338-1340.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gouvea V, Santos N, Timenetsky M C. VP4 typing of bovine and porcine group A rotaviruses by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1333–1337. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1333-1337.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gouvea V, Glass R I, Woods P, Taniguchi K, Clark H F, Forrester B, Fang Z. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus nucleic acid from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:276–282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.276-282.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapikian A Z, Chanock R M. Rotaviruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1657–1708. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkwood C, Masendycz P, Coulson B S. Characteristics and location of cross-reactive and serotype-specific neutralization sites on VP7 of human G type 9 rotaviruses. Virology. 1993;196:79–88. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palombo E A, Bugg H C, Masendycz P J, Bishop R F. Sequence of the VP7 gene of an atypical human rotavirus: evidence for genetic and antigenic drift. DNA Seq. 1997;7:307–311. doi: 10.3109/10425179709034050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palombo E A, Bugg H C, Masendycz P J, Coulson B S, Barnes G L, Bishop R F. Multiple-gene rotavirus reassortants responsible for an outbreak of gastroenteritis in central and northern Australia. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1223–1227. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-6-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereira H G, Azeredo R S, Leite J P G, Candeias J A N, Rácz M L, Linhares A C, Gabbay Y B, Trabulsi L R. Electrophoretic study of the genome of human rotaviruses from Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Pará, Brazil. J Hyg. 1983;90:117–125. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400063919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santos N, Lima R C C, Nosawa C M, Linhares R E, Gouvea V. Detection of porcine rotavirus type G9 and of a mixture of types G1 and G5 associated with Wa-like VP4 specificity: evidence for natural human-porcine genetic reassortment. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2734–2736. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2734-2736.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki Y, Gojobori T, Nakagomi O. Intragenic recombination in rotaviruses. FEBS Lett. 1998;427:183–187. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taniguchi K, Urasawa T, Morita Y, Grenberg H B, Urasawa S. Direct serotyping of human rotavirus in stools by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using serotype 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-specific monoclonal antibodies to VP7. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:1159–1166. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.6.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theil K W. Group A rotaviruses. In: Saif L J, Theil K W, editors. Viral diarrheas of man and animals. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 279–367. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Timenetsky M C, Santos N, Gouvea V. Survey of rotavirus G and P types associated with human gastroenteritis in Sao Paulo, Brazil, from 1986 to 1992. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2622–2624. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2622-2624.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urasawa S A, Urasawa T, Taniguchi K, Wakasugi F, Kobayashi N, Chiba S, Sakurada N, Morita M, Tokieda M, Kawamoto H, Minekawa Y, Ohseto M. Survey of human rotavirus serotypes in different locales in Japan by using by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with monoclonal antibodies. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:44–51. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]