Abstract

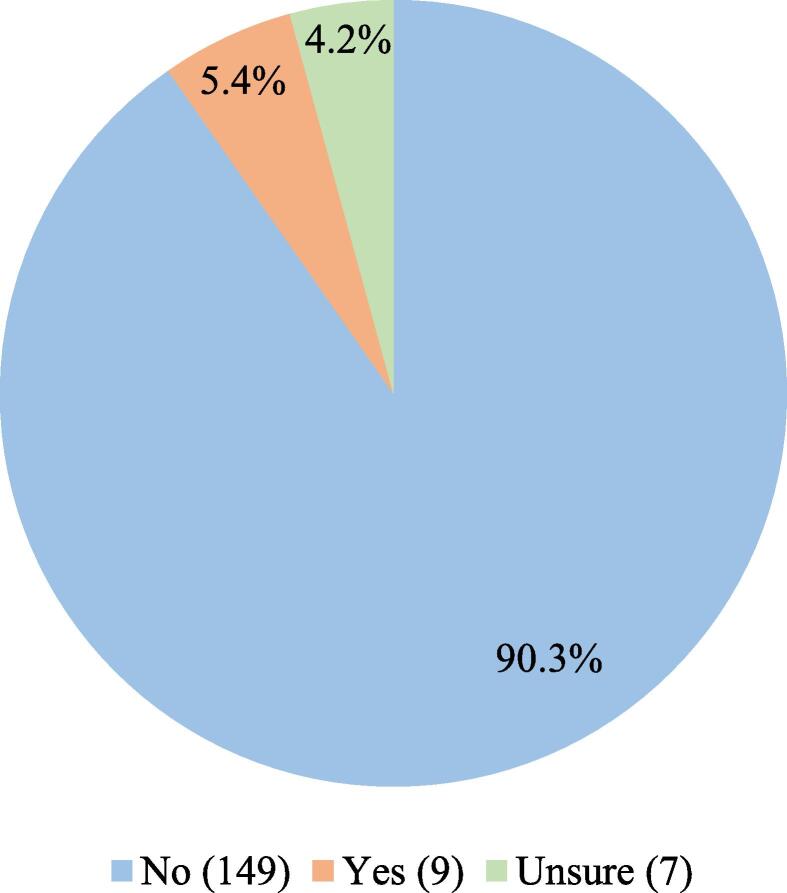

Our objective was to identify the percentage of marijuana-using caregivers who have been asked about their marijuana use by their child’s pediatrician. Data was collected from a cross-sectional, convenience sample survey study of 1500 caregivers presenting with their children to the Children’s Hospital Colorado Pediatric Emergency Department between December 2015 and July 2017. Of the 1500 caregivers surveyed, 167 (11%) reported using marijuana. When asked if their child’s pediatrician had ever inquired/counseled about caregiver marijuana use, 165 marijuana-using caregivers responded; 149 caregivers (90.3%) reported “no,” 9 caregivers (5.4%) reported “yes,” and 7 caregivers (4.2%) reported “unsure.” We concluded that of marijuana-using caregivers, only a small percentage indicated their child’s pediatrician had inquired about caregiver marijuana use. This suggests pediatricians are not engaging caregivers about marijuana use and the subsequent secondhand marijuana smoke exposure for children. The continued rise of marijuana use among parents makes this research of public health importance.

Keywords: Secondhand smoke, Marijuana, Tobacco, Pediatrics

1. Introduction

Marijuana is the second most common psychotropic substance used in the United States after alcohol, with nearly 12 million young adults reporting marijuana use in the past year (Volkow, 2020). While there is a declining trend of tobacco use in the United States, marijuana utilization is on the rise. Between 2002 and 2015, specifically among parents with children at home, marijuana use increased from 5% to 7%, while tobacco use decreased from 27% to 20%. A larger increase in marijuana use was seen in those who also smoke tobacco; during the same time period, marijuana use among tobacco smoking parents increased from 11% to 17% (Goodwin et al., 2018). When marijuana and tobacco smoking are combined, the harmful health effects may be potentiated (Macleod et al., 2015). Marijuana use among the next generation of parents (adults aged 19–22 years) also appears to be on the rise. The National Institute on Drug Abuse survey found marijuana use is at a historic high among this demographic, with approximately 43% of persons reporting any prior marijuana use, and 6–11% of persons reporting daily use (Schulenberg et al., 2020).

Marijuana smoking is often perceived as less harmful than tobacco smoking, yet marijuana and tobacco smoke contain many of the same toxic chemicals and carcinogens (Moir et al., 2008). Secondhand marijuana smoke exposure in children has not been extensively studied, while the negative health effects of tobacco smoke are well documented. As the 2006 Surgeon General Report on involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke noted: tobacco smoke is clearly linked to several pediatric diseases with significant morbidity and mortality including otitis media, impaired lung function, lower respiratory illness, and sudden infant death syndrome (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). Because of the similarities between marijuana and tobacco, further research into the potential harmful effects of secondhand marijuana is of importance.

While there is a dearth of specific messaging regarding marijuana, many organizations have highlighted the negative consequences of tobacco smoke and have created policy statements. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) states, “tobacco is unique among consumer products in that it severely injures and kills when used exactly as intended (Farber and Nelson, 2015).” There is no safe level of tobacco smoke exposure, as it poses harm from the moment of conception. The AAP suggests pediatricians counsel caregivers who smoke about smoking cessation, as well as provide advice to all children and adolescents regarding tobacco dangers before they initiate use.

Even with the AAP’s policy statement and encouragement of pediatricians to engage parents, studies show that only about 50% of parents were asked about their child’s smoke exposure by their pediatrician (Winickoff et al., 2003). How often pediatricians ask about marijuana use among parents has not been studied. Therefore, it is our aim to identify the percentage of caregivers who have been asked about marijuana utilization by their child’s pediatrician.

2. Methods

This brief article is a sub-analysis of a larger research study that consisted of a cross-sectional survey of a convenience sample of 1500 caregivers presenting with their children to a Pediatric Emergency Department in Colorado. Surveys were administered to caregivers between December 2015 and July 2017, several years after Colorado had legalized recreational marijuana use. Caregivers who met inclusion criteria were English or Spanish speaking, 21 to 85 years-old, presenting to the Pediatric ED with their child. Exclusion criteria included caregivers of all of the following: critically ill children, medically complex children, children over 11 years-old (to exclude primary marijuana use by the child), children utilizing medical marijuana, and children previously incorporated in this study. The hospital’s Institutional Review Board approved this study. This work has been carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and prioritized patient privacy and safety.

Caregivers were approached after presentation to the Pediatric ED by study investigators or trained research assistants. Once informed consent was obtained, participants were asked to complete the survey during wait times. Surveys were available in English and Spanish and were self-administered on a tablet. Responses were directly uploaded to a password protected REDCap database to maintain confidentiality. The survey asked questions regarding demographics, medical history of the child, and caregiver tobacco and marijuana habits. The specific question regarding marijuana use was, “Does anyone who lives in your home or who primarily cares for your child use marijuana (in any form)?” When respondents indicated marijuana use, the survey then asked several follow up questions such as type and frequency of use. The survey further prompted every caregiver indicating marijuana use to answer the question: “Has your child’s pediatrician ever asked or counseled you about marijuana?” The caregivers could respond with either “yes,” “no,” or “unsure.”

3. Results

Of the 1500 study participants, a total of 167 caregivers (11.1%) reported marijuana use. Investigating concomitant use of marijuana and tobacco, 84 caregivers (50.2%) reported only using marijuana, while 83 caregivers (49.7%) reported using both marijuana and tobacco. Of the marijuana users, the majority (158 caregivers) indicated a smoked or vaped route. In regards to frequency, 150 caregivers (90%) indicated their marijuana use was at least weekly, which we considered regular use (Table 1).

Table 1.

Caregiver-Reported Marijuana Use. Note: caregivers could indicate more than one type of marijuana product used.

| Total number of survey participants n = 1500 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Marijuana Use n = 167 | No Marijuana Use n = 1333 | |

| Type(s) of marijuana used | n/a | |

| Smoked/Vaporized | 158 (94.6%) | |

| Edibles | 42 (25.1%) | |

| Concentrated products | 13 (7.8%) | |

| Topical | 13 (7.8%) | |

| Other | 3 (1.8%) | |

| Frequency of marijuana use | n/a | |

| Daily | 76 (45.5%) | |

| Several times per week | 41 (24.6%) | |

| Weekly | 33 (19.7%) | |

| Several times per month | 9 (5.4%) | |

| Once per month | 5 (3.0%) | |

| <Once per month | 3 (1.8%) | |

| Tobacco use | ||

| Yes | 83 (49.7%) | 214 (16.1%) |

| No | 84 (50.2%) | 1119 (83.9%) |

We asked all marijuana-using caregivers if their child’s pediatrician had ever asked or counseled them about their marijuana use. Of the 167 marijuana-users, 165 responded to this question. One hundred forty nine caregivers (90.3%) reported “no,” 9 caregivers (5.4%) reported “yes,” and 7 caregivers (4.2%) reported “unsure” (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of marijuana-using caregivers who have been asked about their marijuana use by their child's pediatrician.

4. Discussion

Not much is known about the effects of secondhand marijuana smoke on children. Given the similar chemical composition to tobacco smoke, the negative health effects of marijuana smoke exposure may be similar. Pediatricians are encouraged to ask about and counsel parents about tobacco use, with one goal of decreasing secondhand smoke exposure in children. In our cohort, 11% of caregivers admitted to regularly smoking or vaping marijuana, yet only a small percentage of marijuana-using caregivers (5.4%) had been asked by their child’s pediatrician about marijuana use. The results of this study suggests health care providers are not starting the conversation or engaging caregivers about marijuana smoking, and the consequent secondhand smoke exposure for children.

A potential limitation of the study is the under-reporting of substance use given the nature of a survey study. Many of our respondents (75%) did not indicate any substance use, while this number may actually be lower. However, even if tobacco or marijuana-using caregivers did not accurately indicate their use, the overall impact on the results is likely very low. Another potential limitation is the single geographic location from which the study population was derived. The results may not be indicative of marijuana users and/or pediatricians across the country. Given the study population residing in a state with legalized marijuana use, it is reasonable to assume the pediatricians in this state are more likely than others to be familiar with marijuana use among parents and more comfortable with asking about marijuana. A final limitation of our study is that marijuana smoke exposure in children was assumed based on caregiver report of use. We did not measure biochemical validation in the children, which would have provided a precise measure of tobacco smoke exposure or marijuana smoke exposure. Prior studies have evaluated tobacco exposure in children by proxy of parental report, and we used a similar method. In the state where we conducted the survey, recreational use of marijuana is legal, yet it remains illegal to use marijuana on public property, raising the likelihood of caregivers using marijuana on their private property. The survey did not ask the participants to clarify the exact location of use.

5. Conclusion

Marijuana use is on the rise across the United States, including among parents. Increased usage of marijuana is likely as more states seek to legalize its recreational use; data indicates states with legalization of marijuana tend to have higher rates of use among its citizens (National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2021). While dangers of primary marijuana use are becoming more evident (Volkow et al., 2014), and the dangers of secondhand tobacco smoke already well established, marijuana exposure should also be addressed given its similarities to tobacco smoke. Pediatricians or general practitioners may be caring for an increasing number of children from homes where marijuana smoking occurs. Our study provides evidence that marijuana users are not being engaged in conversations regarding their own marijuana use, and therefore childhood marijuana smoke exposure remains poorly addressed. It may be beneficial for health care providers to screen families for marijuana use and be prepared to provide anticipatory guidance and marijuana smoking cessation counseling. Public health messaging similar to that of secondhand tobacco smoke could be implemented, as these methods have been established and have been shown to be informative and beneficial (Hall et al., 2016).

Funding

There was no source of funding for this study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Adam B. Johnson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing - original draft. Dana B. Watson: Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Farber H.J., Nelson K.E. Public policy to protect children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke, section on tobacco control. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):998–1007. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin R.D., Cheslack-Postava K., Santoscoy S., Bakoyiannis N., Hasin D.S., Collins B.N., Lepore S.J., Wall M.M. Trends in cannabis and cigarette use among parents with children at home: 2002 to 2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20173506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall K., Kisely S., Urrego F. The Use of pediatrician interventions to increase smoking cessation counseling among smoking caregivers: a systematic review. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila) 2016;55(7):583–592. doi: 10.1177/0009922816632347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod J., Robertson R., Copeland L., McKenzie J., Elton R., Reid P. Cannabis, tobacco smoking, and lung function: a cross-sectional observational study in a general practice population. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2015;65(631):e89–e95. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X683521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moir D., Rickert W.S., Levasseur G., Larose Y., Maertens R., White P., Desjardins S. A Comparison of mainstream and sidestream marijuana and tobacco cigarette smoke produced under two machine smoking conditions. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008;21(2):494–502. doi: 10.1021/tx700275p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5-6 2015-2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Model-Based Prevalence Estimates (50 States and the District of Colombia) https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHsaePercents2016/NSDUHsaePercents2016.pdf.

- Schulenberg, J. E., Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Miech, R. A. & Patrick, M. E., 2020. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2019: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–60. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs.html#monographs.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006.

- Volkow N.D., Baler R.D., Compton W.M., Weiss S.R.B. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow, N.D., 2020, Marijuana Research Report. National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institutes of Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services NIDA. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana. Revised July 2020.

- Winickoff J.P., McMillen R.C., Carroll B.C., Klein J.D., Rigotti N.A., Tanski S.E., Weitzman M. Addressing parental smoking in pediatrics and family practice: a national survey of parents. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):1146–1151. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]