Abstract

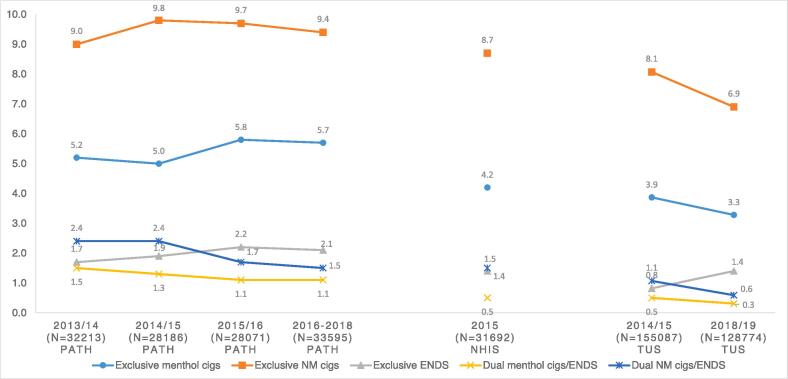

This study examines patterns of use for menthol/non-menthol cigarettes and Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) from 2013 to 2019 among U.S. adults. We calculated the weighted population prevalence of current exclusive and dual use for each product (i.e., menthol/non-menthol cigarettes and ENDS) stratified by age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income, and education in all surveys using data from three nationally representative surveys: the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study Waves 1–4 (W1-W4), 2013–2018; the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) 2015; and the Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS) 2014–2015 (T1) and 2018–2019 (T2). Exclusive non-menthol cigarette use (PATH: 9.0%W1, 9.4%W4; NHIS: 8.7%; TUS-CPS: 8.1%T1, 6.9%T2) and dual non-menthol cigarette/ENDS use (PATH: 2.4%W1, 1.5%W4; NHIS: 1.5%; TUS-CPS: 1.1%T1, 0.6%T2) were the most common single and dual tobacco use patterns, respectively, across all surveys. Both exclusive menthol cigarette use (3.9%T1-3.3%T2) and non-menthol cigarette use (8.1%T1-6.9%T2) declined in TUS-CPS from 2014/5–2018/9. Dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use also declined (PATH: 1.5%W1-1.1%W4; TUS-CPS: 0.5%T1-0.3%T2), as did dual non-menthol cigarette/ENDS use (PATH: 2.4%W1-1.5%W4; TUS-CPS 1.1%T1-0.6%T2). Across surveys, exclusive menthol cigarette use and dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use were more common among individuals aged 25–34 years old; non-Hispanic Blacks (NHBs); and low-income earners. Single and dual use patterns of menthol/non-menthol cigarettes and ENDS have declined over time. Nevertheless, certain vulnerable population groups, including NHBs and low-income earners, disproportionately use exclusive menthol cigarettes and dual menthol cigarette/ENDS, making menthol bans a potential policy target for reducing tobacco-related health disparities.

Keywords: Sociodemographic disparities, Cigarettes, Electronic cigarettes, Menthol, Dual use

1. Introduction

Menthol is an additive present in 90% of all commercial cigarettes in the United States, (Anderson, 2011) specifically in menthol cigarettes at about 0.1 percent or higher and in non-menthol cigarettes at about 0.03 percent or less. (TPSAC, 2011, Giovino et al., 2004, Williamson, 1986) Menthol cigarette sales represented about 35.4% of the cigarette market in 2018, up from 25.9% in 2010. (Delnevo et al., 2020) Compared to non-menthol cigarettes, menthol cigarettes are more likely to pose a public health risk to users and non-users of tobacco products. (TPSAC, 2011, Delnevo et al., 2020, Villanti et al., 2017) For non-users, menthol cigarette availability increases the likelihood of tobacco experimentation, and among users, menthol cigarette availability is linked with regular smoking and tobacco use addiction. (Hersey et al., 2010, Cullen et al., 2019) In addition, menthol cigarette smokers experience greater nicotine dependence symptoms, such as shorter first cigarette after waking, smoking cravings, and feeling irritable having not smoked for a few hours compared to non-menthol cigarette smokers. (Villanti et al., 2017, Hersey et al., 2010)

Studies have shown that youth, women, non-Hispanic Blacks, and people with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to smoke menthol cigarettes, thereby increasing the cigarette use burden among these population groups and contributing to tobacco-related health disparities. (D'Silva et al., 2012, Balbach et al., 2003, Villanti et al., 2016, Yerger et al., 2007, Gardiner, 2004, Vozoris, 2012) Among non-Hispanic Blacks, menthol cigarette smokers are also less likely than non-menthol smokers to quit smoking. (Smith et al., 2020) Furthermore, menthol cigarette smoking among young and middle-aged adults has been associated with the use of other flavored tobacco products like cigars and cigarillos, (Sterling et al., 2016, Sawdey et al., 2020) alcohol, and marijuana. (Azagba and Sharaf, 2014) Considering the evidence of the risks associated with menthol cigarette smoking, more studies will be useful to support the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposals that ban menthol flavors in specific tobacco products.

Similarly, exclusive ENDS use increased from 2.4% to 4.2% among US adults aged 25–44 years and from 2.4% to 7.6% among young adults from 2012 to 2018. (Phillips et al., 2017, Dai and Leventhal, 2019, [21]) Most ENDS products contain nicotine, which in turn can increase the risk of addiction, (Vanyukov et al., 2012, Jankowski et al., 2019) but it remains unknown what doses may result in health problems. (Office on Smoking et al., 2019) On the other hand, ENDS use may contribute to the reduction in smoking prevalence due to reduced initiation as the use of conventional cigarettes have declined among young adults. (Levy et al., 2019) Studies have shown that frequent ENDS use promoted smoking cessation among adults, (Hajek et al., 2019, Brouwer et al., 2020) although a number of adults who use ENDS as a cessation tool may end up as dual users, inadvertently discouraging cessation. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020) Thus, the risks and benefits of ENDS remain controversial mainly because of the insufficient evidence on its public health effects. (TPSAC, 2011, Office on Smoking et al., 2019)

A few studies have examined the population prevalence of cigarette and ENDS dual use, with estimates of 1.3% to 9.7% across different surveys. (Hirschtick et al., 2021, Weinberger et al., 2020, Villarroel et al., 2018) Sociodemographic patterns of exclusive ENDS use and dual use (cigarette and ENDS) differ depending on the characteristic. Unlike ENDS users who are mostly young adults (18–24 years old), (Dai and Leventhal, 2019, Hirschtick et al., 2021, Weinberger et al., 2020, Mayer et al., 2020) dual users are more likely to be older. (Hirschtick et al., 2021, Mayer et al., 2020) ENDS use patterns vary by income and education; some studies reported higher income individuals are more likely to use ENDS compared to low-income individuals, while some found no significant association (Dai and Leventhal, 2019, Hirschtick et al., 2021, Friedman and Horn, 2019). Dual users, on the other hand, are more likely to be individuals with less than a college degree than those with four or more years of college (Mayer et al., 2020), and lower-income individuals compared to those with a higher income. (Hirschtick et al., 2021) ENDS and dual use patterns are similar by race/ethnicity and sex; non-Hispanic White adults and men are more likely than other racial groups and women, respectively, (Weinberger et al., 2020, Mayer et al., 2020) to be both exclusive ENDS and dual users. Despite existing evidence on cigarettes and ENDS dual use, the sociodemographic patterns of menthol/non-menthol cigarette flavors and ENDS dual use are unknown.

This study aims to present recent trends on exclusive and dual use of menthol/non-menthol cigarette with ENDS from 2013 to 2019 using three nationally representative surveys. We examine data from three large nationally representative surveys collected over a similar period, enabling us to produce a range of comparable national estimates of exclusive and dual use of menthol/non-menthol cigarettes and ENDS. We also examine differences in patterns by age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and income.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

Data on sociodemographic variables, menthol/non-menthol cigarette smoking, and ENDS use were obtained from three nationally representative samples: the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Waves 1–4, 2013–2018, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) 2015, and the Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS) 2014/2015 and 2018/2019. We included NHIS 2015 as this was the only year, following 2010, the survey examined menthol flavoring in cigarettes. Details on each survey characteristics and variable definition can be found in the Supplement Guide.

The PATH Study is a longitudinal, nationally representative study of the US non-institutionalized population aged ≥ 12 years. It used a four-stage stratified area probability sample design, varying sampling rates for adults by age, race, and tobacco use status. (Hyland et al., 2017) Our study used the adult (aged ≥ 18 years) sample in PATH Waves 1 (September 2013 to December 2014), 2 (October 2014 to October 2015), 3 (October 2015 to October 2016), and 4 (December 2016 to January 2018). The PATH Study design oversampled tobacco users, young adults (aged 18–24), and Non-Hispanic Blacks adults. (Friedman and Horn, 2019)

The NHIS is a cross-sectional household interview survey that has been conducted since 1957. The sampling plan follows an area probability design that permits the representative sampling of households and non-institutional group quarters (e.g., college dormitories). (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016) The TUS-CPS is conducted every 3–4 years as part of the CPS, a monthly survey conducted by the US Census Bureau for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In each cycle, TUS-CPS collects nationally representative data from about 240,000 adults. (National Cancer Institute, 2016) We included three nationally representative surveys to provide a potential range of prevalence estimates for adult tobacco use as survey estimates may differ based on survey design. The study was exempt from the Institutional Review Board review because it was a secondary analysis of de-identified data.

2.2. Tobacco use measures

We classified tobacco products into menthol cigarettes, non-menthol cigarettes, and ENDS. ENDS were defined as e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes, e-hookahs, or other e-products in PATH (the definition of e-products changed across PATH wave questionnaires), and e-cigarettes, including vape-pens, hookah-pens, e-hookahs, or e-vaporizers in the NHIS and TUS-CPS studies. Current use for cigarette smokers was defined as smoking every day or some days for established smokers (smokers who had smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetime). Menthol cigarette use was defined as cigarette smokers indicating that their regular brand was flavored to taste like menthol/mint in PATH surveys and stating that they usually smoke menthol cigarettes instead of non-menthol cigarettes in the TUS-CPS and NHIS surveys. We defined current use among ENDS users as having used e-cigarettes every day or some days in the NHIS and TUS-CPS studies and PATH waves 1 and 2, and having used e-products every day or someday in PATH waves 3 and 4. Overall, we categorized tobacco measures into exclusive use of menthol cigarettes, non-menthol cigarettes, and ENDS, and dual use of menthol cigarettes with ENDS and non-menthol cigarettes with ENDS.

2.3. Sociodemographic variables

Sociodemographic variables included age group (18–24, 25–34, 35–54, or 55 + ), sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White [NHWs], Non-Hispanic Black [NHBs], Hispanics, or Non-Hispanic other [NHOs]), annual household income (<50 K [low-income earners], $50 K-$100 K [middle-income earners], or ≥$100 K [high-income earners]), and education for adults 25 years and older (<high school education, high school, some college, or ≥ 4-year college).

2.4. Statistical analyses

We calculated the weighted population prevalence for current exclusive and dual use of each tobacco product category stratified by age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income, and education in all surveys and adjusted for the appropriate complex survey designs. For PATH and TUS-CPS confidence intervals we used the balanced repeated replication (BRR) estimation and the Taylor linearization for NHIS. Considering the large number of comparisons in prevalence estimates - for five categories of tobacco-use patterns, across 17 sociodemographic strata and three surveys - we estimated significant differences in prevalence by examining a 95% confidence interval overlap between the subgroups across years and for all surveys. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 16.

3. Results

Fig. 1 presents tobacco product use distributions for each sample while supplementary table 1 also includes population characteristics. All three surveys had more females (51.7% NHIS 2015; 52.1% PATH Wave 3; 51.9% TUS-CPS 2014/15) than males, and NHWs were over half of the sampled population in NHIS 2015 (65.7%), PATH Wave 3 (65.6%), and TUS-CPS 2014/15 (64.8%). Approximately one-third of the population were aged 35–54 years old (34.1% NHIS 2015, 33.3% PATH Wave 3; 34.2% TUS-CPS 2014/15) and over another third were aged 55 and older (35.9% NHIS 2015, 36.8% PATH Wave 3; 35.2% TUS-CPS 2014/15). Over half of the PATH population were low-income earners (53.5% Wave 3), while low-income earners represented 42.7% of the NHIS and 49.7% of the TUS-CPS 2014/15 sample. Each educational category—high school, some college, and > 4-year college—represented between 25 and 30% of the sampled population in all three surveys (Supplementary table 1).

Fig 1.

Exclusive and Dual Use of Menthol/Non-menthol Cigarettes and ENDS among US Adults 2013–2019; PATH, TUS and NHIS.

In the following sections, we compare the overall prevalence estimates across surveys at one point in time using NHIS 2015, PATH Wave 2 (2014/15), and TUS-CPS 2014/15. We describe the frequency estimates across the sociodemographic groups using NHIS only, a cross-sectional study, better suited for prevalence measures than PATH which is a longitudinal study. Similarly, we use only the TUS-CPS sample, another cross-sectional study, to describe the overall time trends and across sociodemographic groups.

3.1. Cross-sectional patterns of exclusive and dual use of menthol or non-menthol cigarette and ENDS use

Exclusive non-menthol cigarette use (PATH 9.8% W2; NHIS 2015, 8.7%; TUS-CPS 2014/15, 8.1%) and dual non-menthol cigarette/ENDS use (PATH 2.4% W2; NHIS 2015, 1.5%; TUS-CPS 2014/15, 1.1%) were the most common single and dual tobacco use categories in each survey (Fig. 1). Exclusive menthol cigarette prevalence estimates (PATH W2, 5.0%; NHIS 2015, 4.2%; TUS-CPS 2014/15, 3.9%) were approximately half that of non-menthol cigarette use, and the prevalence of dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use ranged from 0.5% (NHIS and TUS-CPS 2014/15) to 1.3% (PATH W2). Overall, PATH estimates were higher than NHIS, which were higher than the TUS-CPS estimates (Fig. 1).

3.2. Prevalence of exclusive and dual use of menthol/non-menthol cigarettes and ENDS by sociodemographic characteristics using NHIS 2015

Non-menthol cigarette use and dual non-menthol cigarette/ENDS use were the most common exclusive and dual tobacco product use patterns among all sampled sociodemographic groups: age (Fig. 2, Supplementary table 2); sex (Supplementary table 3); race/ethnicity, except for NHBs, where menthol cigarettes and menthol cigarettes/ENDS were more common (Fig. 3, Supplementary table 4); income (Supplementary table 5); and education (Fig. 4, Supplementary table 6).

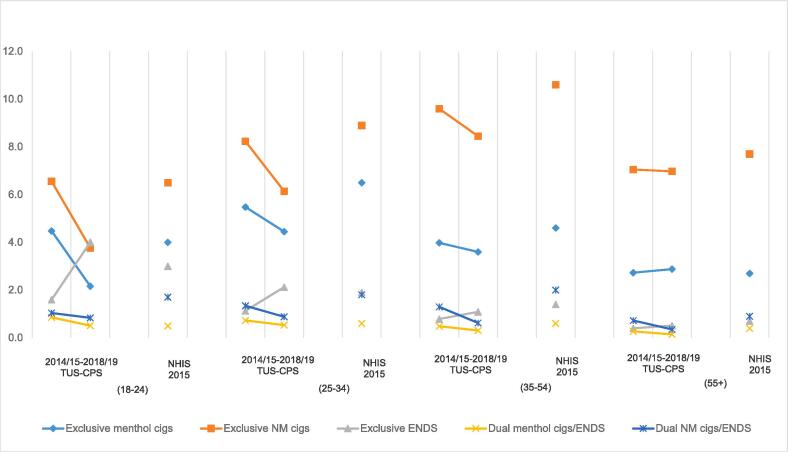

Fig 2.

Trends of Exclusive and Dual Use of Menthol/Non-menthol Cigarettes and ENDS among US Adults by Age group 2014–2019; TUS & 2015; NHIS.

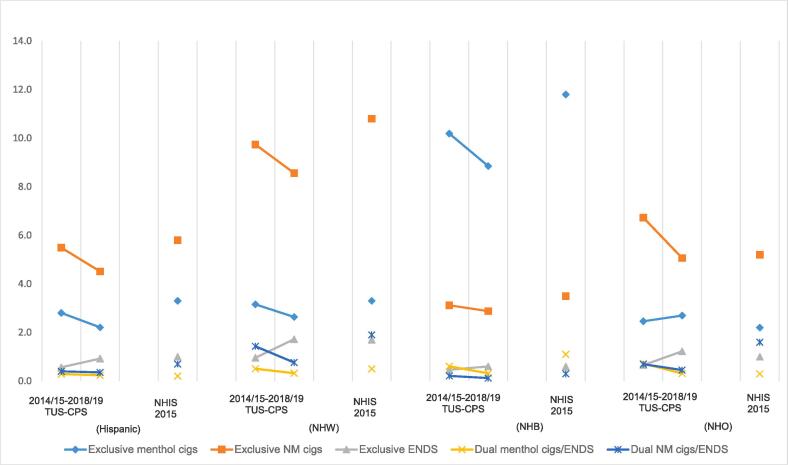

Fig 3.

Trends of Exclusive and Dual Use of Menthol/Non-menthol Cigarettes and ENDS among US Adults by Race/Ethnicity 2014–2019; TUS & 2015; NHIS.

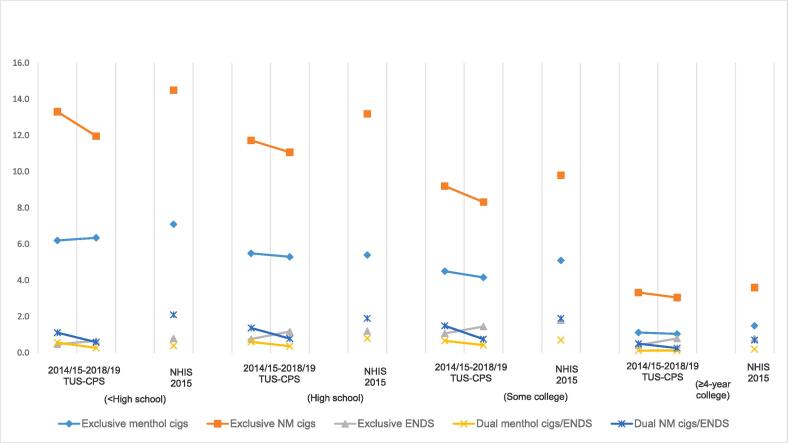

Fig 4.

Trends of Exclusive and Dual Use of Menthol/Non-menthol Cigarettes and ENDS among US Adults by Education 2014–2019; TUS & 2015; NHIS.

There were important differences in exclusive and dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use prevalence across sociodemographic groups, particularly by age and race/ethnicity. As mentioned earlier, we describe some of these differences here using the NHIS 2015 results. For instance, exclusive menthol cigarette use was more common among adults aged 25–34 years followed by 35–54-year-olds, while adults aged 55 + had the lowest prevalence (NHIS 6.5%, 4.6%, 2.7% respectively). Dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use was comparable among all age groups (NHIS 0.4%-0.6%) (Fig. 2). For race/ethnicity, NHBs used menthol cigarettes and dual menthol cigarette/ENDS much more commonly than NHWs; exclusive menthol cigarette use was 11.8% for NHBs and 3.3% for NHWs in NHIS, and dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use was 1.1% for NHBs and 0.5% for NHWs in NHIS (Fig. 3).

For socioeconomic groups, exclusive menthol cigarette use was more common among people with less than high school education (NHIS 7.1%) compared to other education levels (i.e., high school (NHIS 5.4%), some college (NHIS 5.1%), and college (NHIS 1.5%). Dual use patterns were comparable among all education levels, except that people with a college education who had a lower prevalence (Fig. 4). Regarding income, all tobacco use patterns in each survey were most common among low-income earners (<$50 K), except exclusive ENDS use, which was most common among middle-income earners (Supplementary table 6).

3.3. Overall trends of exclusive and dual use of menthol/non-menthol cigarettes and ENDS using TUS-CPS 2014/15 to TUS-CPS 2018/19

Using the TUS-CPS sample, exclusive menthol cigarette use decreased from 3.9% to 3.3% and non-menthol cigarette use decreased from 8.0% to 6.9% from 2014/2015 to 2018/2019. On the contrary, exclusive ENDS use increased from 0.8% to 1.4% during the same time period. Similar to cigarettes, dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use (TUS-CPS 0.5% T1 to 0.3% T2) and dual non-menthol cigarette/ENDS use TUS-CPS 1.1% T1 to 0.6% T2) decreased over time (Fig. 1).

3.4. Trends of exclusive and dual use of menthol/non-menthol cigarettes and ENDS by sociodemographic characteristics using TUS-CPS 2014/15 to TUS-CPS 2018/19

Tobacco use patterns changed over time across age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Exclusive non-menthol cigarette and menthol cigarette use decreased while exclusive ENDS use increased among 18–24-year-olds (Fig. 2, Supplementary table 2). However, comparable to all other age groups, there was a smaller decrease in dual non-menthol cigarette/ENDS use among 18–24-year-olds (Supplementary table 7). Among females, from 2014/15 to 2018/19, the prevalence of exclusive non-menthol cigarette use decreased by 12.7% (6.5% to 5.6%), while exclusive menthol cigarette use decreased by 14.9% (4.0% to 3.4%) (Supplementary table 7). Exclusive menthol cigarette use decreased by 13.2% among NHBs (10.2% to 8.8%), while exclusive ENDS use increased by 80.2% among NHWs (1.0% to 1.7%) (Fig. 3, Supplementary table 7). Tobacco use patterns also changed over time among socioeconomic groups. Exclusive non-menthol cigarette use decreased by 5.6% (11.7% to 11.1%) while exclusive ENDS use increased by 54.4% (0.8% to 1.2%) for participants with high school education (Supplementary table 7). Dual use patterns decreased across all education levels, except that dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use remained flat over time among people with a college education (Supplementary table 7). Exclusive menthol/non-menthol cigarettes and dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use decreased only among the low income earners (<$50 K) and fluctuated among other income groups (Supplementary table 7). Exclusive ENDS use increased among all income groups, while dual non-menthol cigarette/ENDS use decreased across all income levels (Supplementary table 7).

4. Discussion

Our study extends existing research on menthol/non-menthol use patterns beyond cigarettes to include ENDS across three nationally representative surveys. We present prevalence estimates of exclusive and dual use of menthol/non-menthol cigarettes and ENDS overall and stratified by age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and household income. Consistent with earlier studies, (Delnevo et al., 2020, Villanti et al., 2016, Giovino et al., 2015) our findings reveal that exclusive non-menthol cigarette use was more common than exclusive menthol cigarette use in all the population subgroups except for NHBs. We also found that exclusive non-menthol cigarettes declined among young adults aged 18–24, all race/ethnicities, and low-income earners between 2014 and 2019, continuing the downward trend from 2004 to 2015. (Villanti et al., 2016, Giovino et al., 2015, Mattingly et al., 2020) Our results also add to the existing literature by showing that dual non-menthol cigarette/ENDS use was more common than dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use in all population subgroups except NHBs.

Our results indicate that exclusive menthol cigarette and dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use was highest among adults aged 25–34 years. These results indicate the persistent use of menthol-flavored tobacco products among adults aged 18–34 years, consistent with previous patterns from 2004 to 2014. (Villanti et al., 2016, Giovino et al., 2015) We observed an overall decline in exclusive menthol cigarette use and over 70 percent increase in ENDS use from 2014 to 2019 in the TUS-CPS surveys. Among adults, menthol /mint flavor is the second highest preferred flavor, following tobacco flavor, for ENDS initiation. (Harrell et al., 2017) This suggests that even with an overall decline in exclusive menthol cigarette use, adults may be switching to menthol ENDS use. This possibility is consistent with studies that suggest that people who smoke menthol cigarettes are not likely to switch away from menthol flavors. (Kasza et al., 20142014) As the FDA considers a menthol flavor ban in cigarettes, they should also extend the ban to other tobacco products, especially other combustible products, as it would greatly reduce the tobacco burden among this population. (Delnevo et al., 2020, Villanti et al., 2016, Giovino et al., 2015, Cadham et al., 2020, Chaiton et al., 2020) and prevent multiple tobacco-related health risks as they age. (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health, 2012)

Our findings support earlier studies that show exclusive menthol cigarette use is more common among NHBs, (Villanti et al., 2016, Gardiner, 2004) and adds that dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use is also more common among this group. Furthermore, while we observed that exclusive menthol cigarette smoking decreased among NHB participants, there was no significant change in exclusive ENDS and dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019 in the TUS-CPS data. Despite the decline in exclusive menthol cigarette use among NHBs, the prevalence was over three times higher than the closest racial/ethnic group, NHOs, in 2018/19. A recent study found menthol cigarette prevalence among NHBs to be twice that of other races (Ribisl et al., 2017) and our findings suggest this gap may be increasing. In both surveys, even though exclusive non-menthol cigarette use was most common among NHWs, it was decreasing over time and contributing to the overall decline in cigarette use. (Delnevo et al., 2020) The persistent use of menthol cigarettes among NHBs not only slows the decline in overall cigarette smoking but may lead to a disparity gap between the white and black population. (Villanti et al., 2016, Giovino et al., 2015) A menthol ban in cigarettes has the potential to avoid tobacco use disparities between NHBs and NHWs, and further protect NHBs from further public health burden of exclusive and dual tobacco use. (Villanti et al., 2017)

Our study shows that menthol smoking was more common among the low-income earners (<$50 K), consistent with existing scientific evidence. (Villanti et al., 2017, Levy et al., 2019) We observed a decline in exclusive menthol cigarette use, exclusive non-menthol cigarette use, and dual non-menthol cigarette/ENDS use among low-income earners. Nevertheless, we observed that in 2018/19 (TUS-CPS), 1.5 times more low-income earners smoked menthol cigarettes exclusively than middle-income earners ($50 K-$100 K). Cigarettes, especially discounted flavored brands, are more commonly sold in convenience stores and gas stations, which are more prevalent in low-income neighborhoods and may contribute to this burden of tobacco use. (Ribisl et al., 2017) Also, the high prevalence of menthol cigarette use among low-income earners may be responsible for the persistent use of dual menthol cigarette/ENDS among this group.

We used three different surveys collected during similar periods with similar product definitions to improve the reliability of our conclusions as we provide a probable range of tobacco product use among the US adult population. Nevertheless, there were consistent differences in prevalence estimates across the three surveys; NHIS estimates were lower than PATH and higher than the TUS-CPS estimates. (Hirschtick et al., 2021, Louis et al., 1986) Discrepancies between estimates from PATH (longitudinal), NHIS (cross-sectional), and TUS-CPS (cross-sectional) studies might result from cohort effects or attrition, producing spurious and not substantive differences, (Shuy, 2002) or from data collection methods. Two-thirds of TUS-CPS data are collected via telephone interviews where participants are more likely to underreport stigmatized behaviors such as smoking compared to in-person interviews used by NHIS or self-interviewing methods used in PATH. (Hirschtick et al., 2021, Cho et al., 2021)

This study has several limitations. First, we were unable to reliably compare trend estimates across datasets because of time and survey design differences; PATH (2013 to 2018) is a longitudinal study while TUS-CPS (2014/2015 to 2018/2019) is a cross-sectional study. These time differences may also contribute to the variability in prevalence estimates, which is why we focused on differences across surveys (PATH, NHIS, TUS-CPS) during one point in time, and trends within the TUS-CPS sample. However, including PATH in our study ensures comparability with earlier studies. (Hirschtick et al., 2021, Patel et al., 2021, Villanti et al., 2017) Second, our current use measure did not distinguish between every day and some day users, even though product use and patterns of use may differ between both groups. However, our estimates are easily compared to other studies using this current use definition[51]. Third, we used self-reported data which may threaten the validity and reliability of our measures and may limit the accuracy of our findings. Fourth, we did not analyze ENDS use by flavor which may have provided more context on the differences in cigarette flavoring use patterns. Future studies should consider the use of more recent data to include menthol/non-menthol flavors in ENDS when assessing the use of menthol/non-menthol cigarettes with ENDS to shed more light on the differential use patterns as well as whether or not they were former or never smokers. Lastly, we used a conservative method for our statistical interpretation, but we acknowledge that the use of confidence interval overlap to interpret estimates may miss some significant relationships. However, it ensures that any findings we report as significant are robust considering the large number of comparison groups.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we found that single and dual use patterns of menthol/non-menthol cigarettes and ENDS have declined over time. Nevertheless, certain vulnerable population groups, including NHBs and low-income earners, disproportionately use exclusive menthol cigarettes and dual menthol cigarette/ENDS. While the FDA considers a ban on menthol in cigarettes, these results highlight its urgency. While there may be concerns that menthol smokers may switch to non-menthol brands following a comprehensive menthol ban, studies from Canada and some localities in the US have found that few menthol smokers make that switch. (Cadham et al., 2020, Chaiton et al., 2020) A menthol ban would help protect high-risk groups from initiating and continuing tobacco use and could have a potential pro-equity effect by reducing cigarette use among adults aged 18–34 years, NHBs, and low-income earners. (Giovino et al., 2015) Future studies should assess recent trends in frequency and intensity of exclusive and dual menthol cigarette/ENDS use to better inform tobacco control policy regarding the need and urgency to ban menthol flavors in cigarettes and other tobacco products.

6. Implications

In addition to exclusive menthol cigarette use, NHBs and low-income earners also use menthol cigarette/ENDS disproportionately. As the FDA considers a ban on menthol in cigarettes, these results highlight its urgency. A menthol ban would help protect high-risk groups from initiating and continuing tobacco use, including exclusive and dual use of menthol cigarette/ENDS, and could have a potential pro-equity effect by reducing cigarette use among NHBs, and low-income earners.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health [grant number U54-CA229974]. The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government.

Author contributions

NLF, JH and BU conceptualized the study. JH, LZA, DTM, AP curated the data and conducted the formal analyses. NLF and JH supervised the statistical analyses. BU, JH and NLF drafted the original manuscript. DTL, RM amd NLF acquired funding for the study. All authors contributed to the study design, interpretation of results, and final revision of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101566.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Anderson S.J. Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2011;20(Supplement 2):ii20–ii28. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (TPSAC) TPSAC. Menthol cigarettes and public health: review of the scientific evidence and recommendations. 2011.

- Giovino G., Sidney S., Gfroerer J., O'Malley P., Allen J., Richter P., Cummings K.M. Epidemiology of menthol cigarette use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(1):67–81. doi: 10.1080/14622203710001649696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson B. Summary of Data on Menthol. In:1986.

- Delnevo C.D., Giovenco D.P., Villanti A.C. Assessment of Menthol and Nonmenthol Cigarette Consumption in the US, 2000 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2013601. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanti A.C., Collins L.K., Niaura R.S., Gagosian S.Y., Abrams D.B. Menthol cigarettes and the public health standard: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):983. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4987-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersey J.C., Nonnemaker J.M., Homsi G. Menthol cigarettes contribute to the appeal and addiction potential of smoking for youth. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(Supplement 2):S136–S146. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen K.A., Liu S.T., Bernat J.K., Slavit W.I., Tynan M.A., King B.A., Neff L.J. Flavored Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students - United States, 2014–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(39):839–844. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6839a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Silva J., Boyle R.G., Lien R., Rode P., Okuyemi K.S. Cessation outcomes among treatment-seeking menthol and nonmenthol smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(5):S242–S248. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbach E.D., Gasior R.J., Barbeau E.M. Reynolds' targeting of African Americans: 1988–2000. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):822–827. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanti AC, Mowery PD, Delnevo CD, Niaura RS, Abrams DB, Giovino GA. Changes in the prevalence and correlates of menthol cigarette use in the USA, 2004-2014. Tob Control. 2016;25(Suppl 2):ii14-ii20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yerger V.B., Przewoznik J., Malone R.E. Racialized geography, corporate activity, and health disparities: tobacco industry targeting of inner cities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(4A):10–38. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner P. The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(1):55–65. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001649478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vozoris N.T. Mentholated cigarettes and cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):590–591. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P.H., Assefa B., Kainth S., Salas-Ramirez K.Y., McKee S.A., Giovino G.A. Use of Mentholated Cigarettes and Likelihood of Smoking Cessation in the United States: A Meta-Analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(3):307–316. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling K, Fryer C, Pagano I, Jones D, Fagan P. Association between menthol-flavoured cigarette smoking and flavoured little cigar and cigarillo use among African-American, Hispanic, and white young and middle-aged adult smokers. Tob Control. 2016;25(Suppl 2):ii21-ii31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sawdey MD, Chang JT, Cullen KA, et al. Trends and Associations of Menthol Cigarette Smoking Among US Middle and High School Students-National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2018. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Azagba S., Sharaf M.F. Binge drinking and marijuana use among menthol and non-menthol adolescent smokers: findings from the youth smoking survey. Addict Behav. 2014;39(3):740–743. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips E., Wang T.W., Husten C.G., Corey C.G., Apelberg B.J., Jamal A., Homa D.M., King B.A. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(44):1209–1215. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6644a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H., Leventhal A.M. Prevalence of e-Cigarette Use Among Adults in the United States, 2014–2018. Jama. 2019;322(18):1824–1827. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.15331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Center for Chronic Disease P, Health Promotion Office on S, Health. Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General. In: E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2016. [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; ed. Rockville, MD: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov M.M., Tarter R.E., Kirillova G.P., Kirisci L., Reynolds M.D., Kreek M.J., Conway K.P., Maher B.S., Iacono W.G., Bierut L., Neale M.C., Clark D.B., Ridenour T.A. Common liability to addiction and “gateway hypothesis”: theoretical, empirical and evolutionary perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:S3–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski M., Krzystanek M., Zejda J.E., et al. E-Cigarettes are More Addictive than Traditional Cigarettes-A Study in Highly Educated Young People. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(13):2279. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16132279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D.T., Warner K.E., Cummings K.M., Hammond D., Kuo C., Fong G.T., Thrasher J.F., Goniewicz M.L., Borland R. Examining the relationship of vaping to smoking initiation among US youth and young adults: a reality check. Tob Control. 2019;28(6):629–635. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P., Phillips-Waller A., Przulj D., Pesola F., Myers Smith K., Bisal N., Li J., Parrott S., Sasieni P., Dawkins L., Ross L., Goniewicz M., Wu Q.i., McRobbie H.J. A Randomized Trial of E-Cigarettes versus Nicotine-Replacement Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):629–637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2019). Surgeon General’s Advisory on E-cigarette Use Among Youth. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/surgeon-general-advisory/index.html. Published 2019. Accessed 7/23/2020, 2020.

- Brouwer AF, Jeon J, Hirschtick JL, et al. Transitions between cigarette, ENDS and dual use in adults in the PATH study (waves 1-4): multistate transition modelling accounting for complex survey design. Tob Control. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hirschtick J.L., Mattingly D.T., Cho B., Arciniega L.Z., Levy D.T., Sanchez-Romero L.M., Jeon J., Land S.R., Mistry R., Meza R., Fleischer N.L. Exclusive, Dual, and Polytobacco Use Among US Adults by Sociodemographic Factors: Results From 3 Nationally Representative Surveys. Am J Health Promot. 2021;35(3):377–387. doi: 10.1177/0890117120964065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger A.H., Zhu J., Barrington-Trimis J.L., Wyka K., Goodwin R.D. Cigarette Use, E-Cigarette Use, and Dual Product Use Are Higher Among Adults With Serious Psychological Distress in the United States: 2014–2017. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(10):1875–1882. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarroel MA, Cha AE, Vahratian A. Electronic Cigarette Use Among U.S. Adults, 2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020(365):1-8. [PubMed]

- Mayer M., Reyes-Guzman C., Grana R., Choi K., Freedman N.D. Demographic Characteristics, Cigarette Smoking, and e-Cigarette Use Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2020694. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A.S., Horn S.J.L. Socioeconomic Disparities in Electronic Cigarette Use and Transitions from Smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(10):1363–1370. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A., Ambrose B.K., Conway K.P., et al. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tobacco Control. 2017;26(4):371–378. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovino G.A., Villanti A.C., Mowery P.D., Sevilimedu V., Niaura R.S., Vallone D.M., Abrams D.B. Differential trends in cigarette smoking in the USA: is menthol slowing progress? Tob Control. 2015;24(1):28–37. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly DT, Hirschtick, J. L., Meza, R., Fleischer, N. F. . Trends in prevalence and sociodemographic and geographic patterns of current menthol cigarette use among U.S. adults, 2005–2015. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2020;20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Harrell M.B., Weaver S.R., Loukas A., Creamer M., Marti C.N., Jackson C.D., Heath J.W., Nayak P., Perry C.L., Pechacek T.F., Eriksen M.P. Flavored e-cigarette use: Characterizing youth, young adult, and adult users. Prev Med Rep. 2017;5:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasza KA, Hyland AJ, Bansal-Travers M, et al. Switching between menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes: findings from the U.S. Cohort of the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(9):1255-1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cadham C.J., Sanchez-Romero L.M., Fleischer N.L., Mistry R., Hirschtick J.L., Meza R., Levy D.T. The actual and anticipated effects of a menthol cigarette ban: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09055-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiton M., Schwartz R., Shuldiner J., Tremblay G., Nugent R. Evaluating a Real World Ban on Menthol Cigarettes: An Interrupted Time-Series Analysis of Sales. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(4):576–579. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribisl K.M., D'Angelo H., Feld A.L., Schleicher N.C., Golden S.D., Luke D.A., Henriksen L. Disparities in tobacco marketing and product availability at the point of sale: Results of a national study. Prev Med. 2017;105:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D.T., Yuan Z., Li Y., Mays D., Sanchez-Romero L.M. An Examination of the Variation in Estimates of E-Cigarette Prevalence among U.S. Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(17):3164. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16173164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis T.A., Robins J., Dockery D.W., Spiro A., Ware J.H. Explaining discrepancies between longitudinal and cross-sectional models. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39(10):831–839. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuy R.W. Handbook of interview research: Context and method. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. In-person versus telephone inter-viewing; pp. 537–555. [Google Scholar]

- Cho B., Hirschtick J.L., Usidame B., Meza R., Mistry R., Land S.R., Levy D.T., Holford T., Fleischer N.L. Sociodemographic Patterns of Exclusive, Dual, and Polytobacco Use Among U.S. High School Students: A Comparison of Three Nationally Representative Surveys. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(4):750–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute . Current Population Survey: Design and Methodology. National Cancer Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention, Health Promotion. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta GA: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics . Survey Description. National Health Interview Survey, 2015, 2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Patel A., Hirschtick J.L., Cook S., Usidame B., Mistry R., Levy D.T., Meza R., Fleischer N.L. Sociodemographic Patterns of Exclusive and Dual Use of ENDS and Menthol/Non-Menthol Cigarettes among US Youth (Ages 15–17) Using Two Nationally Representative Surveys (2013–2017) Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):7781. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanti A.C., Johnson A.L., Ambrose B.K., Cummings K.M., Stanton C.A., Rose S.W., Feirman S.P., Tworek C., Glasser A.M., Pearson J.L., Cohn A.M., Conway K.P., Niaura R.S., Bansal-Travers M., Hyland A. Flavored Tobacco Product Use in Youth and Adults: Findings From the First Wave of the PATH Study (2013–2014) Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(2):139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.