Abstract

We have previously proposed that IQGAP1, an effector of Rac1 and Cdc42, negatively regulates cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion by interacting with β-catenin and by causing the dissociation of α-catenin from cadherin–β-catenin–α-catenin complexes and that activated Rac1 and Cdc42 positively regulate cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion by inhibiting the interaction of IQGAP1 with β-catenin. However, it remains to be clarified in which physiological processes the Rac1-Cdc42-IQGAP1 system is involved. We here examined whether the Rac1-IQGAP1 system is involved in the cell-cell dissociation of Madin-Darby canine kidney II cells during 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)- or hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-induced cell scattering. By using enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-tagged α-catenin, we found that EGFP–α-catenin decreased prior to cell-cell dissociation during cell scattering. We also found that the Rac1-GTP level decreased after stimulation with TPA and that the Rac1-IQGAP1 complexes decreased, while the IQGAP1–β-catenin complexes increased during action of TPA. Constitutively active Rac1 and IQGAP1 carboxyl terminus, a putative dominant-negative mutant of IQGAP1, inhibited the disappearance of α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact induced by TPA. Taken together, these results indicate that α-catenin is delocalized from cell-cell contact sites prior to cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA or HGF and suggest that the Rac1-IQGAP1 system is involved in cell-cell dissociation through α-catenin relocalization.

Although cell-cell adhesion seems to be a static process for those who have not watched movies of cell-cell contacts, dynamic rearrangement of cell-cell adhesion occurs in a variety of cellular processes, including epithelial cell scattering, dispersal of cancer cells, cell division, and tissue rearrangement (for reviews, see references 2, 6, and 31). Cadherins, a family of cell-cell adhesion molecules, bind β-catenin or plakoglobin (also known as γ-catenin), which in turn is linked to the actin cytoskeleton via α-catenin (for a review, see reference 34). This linkage between cadherins and the actin-based cytoskeleton contributes to the development of a strong adhesive state. Indeed, α-catenin-deficient mouse teratocarcinoma F9 cells display a scattered-cell phenotype under conditions in which parental or α-catenin-reexpressing cells form compact colonies (16). In primary cultures of α-catenin-null keratinocytes, actin reorganization and polymerization at sites of cell-cell contact are prevented and adhesive contacts are not sealed (35). Loss of α-catenin expression has also been observed in lung carcinomas (36) and gastric carcinomas (22), and cells derived from these tumors show scattered-cell growth. Studies using optical tweezers and single-particle tracking have indicated that ∼50% of the E-cadherin on the plasma membrane in epithelial cells is connected to the actin cytoskeleton, probably by α-catenin, but that the rest appears to be unattached (29). Taken together, these observations indicate that cell-cell contacts are constantly rearranged through remodeling of cadherin-catenin complexes and that α-catenin is a key regulator. However, the mechanism underlying dynamic rearrangement of cell-cell adhesion remains to be clarified.

Recent studies have shown that Rho family GTPases are involved in the regulation of cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion (3, 13, 30; for a review, see reference 10). The identification and characterization of effectors of Rac1 and Cdc42 have provided insights into the modes of action of these GTPases. We have shown that IQGAP1, an effector of Rac1 and Cdc42, is localized at sites of cell-cell contact and negatively regulates cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion by interacting with E-cadherin and β-catenin and causing the dissociation of α-catenin from cadherin-catenin complexes (15). Activated Rac1 and Cdc42 positively regulate cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion by inhibiting the interaction of IQGAP1 with β-catenin (5). However, the physiological processes in which IQGAP1 functions remain to be clarified.

Cell scattering provides an example of dynamic rearrangement of cell-cell adhesion (2, 6, 31). 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) or hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) induces membrane ruffling, centrifugal spreading of Madin-Darby canine kidney II (MDCKII) cells in colonies, cell-cell dissociation, and ultimately cell scattering (7). This dynamic process is determined by a change in the balance between the cell-cell adhesive activity and cell motility; loss of cell-cell adhesion and increased cell motility promote cell scattering. Tiam1, one of the GDP/GTP exchange factors and an activator for Rac1, is localized at cell-cell contact and inhibits HGF-induced cell scattering in MDCKII cells, probably by increasing cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion (9). In addition, TPA- or HGF-induced cell-cell dissociation and subsequent cell scattering are inhibited in MDCKII cells expressing either constitutively active Rac1 (Rac1V12) or constitutively active Cdc42 (Cdc42V12), a mutant that is defective in GTPase activity and is thought to exist constitutively in the GTP-bound form in cells (11). However, the modes of action of Rac1 and Cdc42 in cell scattering remain to be clarified.

In the present study, we examined whether the Rac1-IQGAP1 system is involved in the cell-cell dissociation during TPA- or HGF-induced cell scattering. By using enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-tagged α-catenin, we found that EGFP–α-catenin disappeared from sites of cell-cell contact prior to cell-cell dissociation during cell scattering. We also found that the Rac1-IQGAP1 complexes decreased while the IQGAP1–β-catenin complexes increased during action of TPA and that Rac1V12 and IQGAP1-carboxyl terminus (IQGAP1-C), a putative dominant-negative mutant of IQGAP1, inhibited the disappearance of α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact induced by TPA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and chemicals.

MDCKII cells, EL cells, the cDNA encoding mouse α-catenin, and anti-E-cadherin rat monoclonal antibody (ECCD-2) were kindly provided by Akira Nagafuchi and Shoichiro Tsukita (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). Human recombinant HGF (21) was kindly provided by Toshikazu Nakamura (Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, Japan). TPA was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). 1,1′-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI) and dextran-conjugated tetramethylrhodamine were purchased from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, Oreg.). Rat anti-E-cadherin monoclonal antibody (ECCD-2) was kindly provided by Masatoshi Takeichi (Kyoto University). Anti-GFP antibody (mFX73) was kindly provided by Shohei Mitani (Tokyo Women's Medical University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan) and was used for immunoprecipitation. Anti-GFP antibody was purchased from CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc. (Heidelberg, Germany) and was used for immunoblotting. Rat anti-ZO-1 monoclonal antibody was purchased from CHEMICON International, Inc. (Temecula, Calif.). Mouse anti-E-cadherin, anti-β-catenin, and anti-plakoglobin monoclonal antibodies were obtained from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, Ky.). Rabbit anti-α-catenin polyclonal antibody and rabbit anti-β-catenin polyclonal antibody were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Mouse anti-hemagglutinin (HA) monoclonal antibody (12CA5) was purchased from Boehringer GmbH (Mannheim, Germany). Mouse anti-Rac1 monoclonal antibody was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology Inc. (Lake Placid, N.Y.). Rabbit anti-IQGAP1 and anti-maltose-binding protein (MBP) polyclonal antibodies were generated against glutathione S-transferase (GST)-IQGAP1 (amino acids [aa] 1 to 216) and MBP, respectively (15). All materials used in the nucleic acid study were purchased from Takara Shuzo Co. (Kyoto, Japan). Other materials and chemicals were obtained from commercial sources.

Plasmid constructs.

The expression plasmid of E-cadherin–GFP (pCDM8-EcadGFP) (1) was kindly provided by W. James Nelson (Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, Calif.). The expression plasmid of Clostridium botulinum C3 ADP-ribosyltransferase (pGEX-C3) was kindly provided by Alan Hall (MRC Laboratory for Molecular Cell Biology, University College London, London, United Kingdom). Various constructs of pGEX2T-small GTPases or pEF-BOS-small GTPases were produced as previously described (14). To obtain EGFP–mouse full-length α-catenin and enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP)-mouse full-length α-catenin, we subcloned the cDNA fragment of α-catenin into EcoRI and BamHI sites of EGFP-C2 (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) and ECFP-C2, which was generated by inserting the BsrGI-StuI fragment of EGFP-C2 into BsrGI and StuI sites of ECFP-C1. To obtain EGFP–human full-length IQGAP1, we subcloned the cDNA fragment of IQGAP1 into SalI and acII sites of EGFP-C2. To obtain MBP–IQGAP1 amino terminus (MBP–IQGAP1-N, aa 1 to 216) and MBP–IQGAP1 carboxyl terminus (MBP–IQGAP1-C, aa 1503 to 1657), the corresponding cDNA fragments of IQGAP1 were subcloned into XhoI sites of pMa1-KK1, which was generated by inserting a synthetic DNA fragment obtained by annealing sense and antisense synthetic nucleotides, sense oligonucleotide 5′-AATTGGGATCCGAATTCCCCGGGGTCGACCTCGAGATCGATAAGCTTTCTAGAGTGACTGACTGA T-3′ and antisense oligonucleotide 5′-AGCTATCAGTCAGTCACTCTAGAA AGCTTATCGATCTCGAGGTCGACCCCGGGGAATTCGGATCCC-3′, into EcoRI and HindIII sites of pMa1-c2 (H. Qadota, unpublished data). A fragment harboring a Cdc42/Rac1 interactive binding region (CRIB) of αPAK (aa 70 to 106) was generated by PCR using oligonucleotides CTGAGGATCCAAGGAGCGGCCAGAGATTTCTCT and CTGAGGATCCTCACAAGCGGGCCCACTGTTCTG, digested with BamHI, and inserted into the BamHI site of pGEX-4T-1 (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) to obtain pGEX-CRIB.

Protein purification.

The expression and purification of GST and various MBP fusion proteins were performed as described previously (15). GST–full-length IQGAP1 was purified from overexpressing Spodoptera frugiperda insect cells as previously described (5).

Cell culture.

MDCKII cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% calf serum. EL cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum containing 0.1 mg of G418/ml (20). To generate MDCKII cells stably expressing EGFP–α-catenin and EGFP-IQGAP1, we transfected MDCKII cells (5 × 105 cells/10-cm-diameter dish) with 25 μg of EGFP-C2–α-catenin and EGFP-C2–IQGAP1, respectively, using the Lipofectamine plus reagent (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.), and cultured them in the presence of 0.6 mg of G418/ml to select for stable transformants. Colonies of G418-resistant cells were isolated. For the generation of MDCKII cells stably expressing both E-cadherin–GFP and ECFP-C2–α-catenin, MDCKII cells were cotransfected with 20 μg of E-cadherin–GFP and 5 μg of pTK-Hyg (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) and cultured in the presence of 0.3 mg of hygromycin/ml. Further, MDCKII cells stably expressing E-cadherin–GFP were transfected with ECFP-C2–α-catenin and cultured in the presence of both 0.6 mg of G418/ml and 0.3 mg of hygromycin/ml. Several stable clones were isolated for each transfection experiment.

Microinjection.

MDCKII cells stably expressing EGFP–α-catenin were seeded at a density of 105 cells/13-mm-diameter cover glass in 6-cm-diameter dishes. At 24 h after seeding, the cells were starved for 24 h. Microinjection of small GTPases (0.1 to 1 mg/ml) or MBP–IQGAP1-C (1 mg/ml) was performed with sterile Femtotips (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) held in a Leitz Micromanipulator with pressure supplied by an Eppendorf Micro-injector 5242 as described previously (14).

Time-lapse imaging and image analysis.

MDCKII cells stably expressing EGFP–α-catenin were seeded at a density of 104 cells/3.5-cm-diameter glass-bottom dishes. At 24 h after seeding, the cells were starved for 24 h. At 30 min after microinjection of small GTPases or MBP–IQGAP1-C, the cells were stimulated with TPA (200 nM) or HGF (50 pM) and observed with a multidimensional microscopy system (DeltaVision SA3.1; Applied Precision, Inc., Issaquah, Wash.) built around a Zeiss Axiovert S100-2TV (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and equipped with a Photometrics PXL-2 cooled charge-coupled device camera containing a Kodak KAF1400 chip (Photometrics, Tucson, Ariz.). A Zeiss 63× plan-Apochromat oil-immersion objective was used. Filters for visualization of ECFP and EGFP were obtained from Chroma Technology Corp. (Brattleboro, Vt.). The out-of-focus information in the raw data was removed by three-dimensional constrained iterative deconvolution using software supplied with the DeltaVision system. For the pseudocolor quantitative representation of fluorescence intensities shown in Fig. 2, images acquired with DeltaVision software were exported to ImagePro Plus 4.0 (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, Md.) and analyzed.

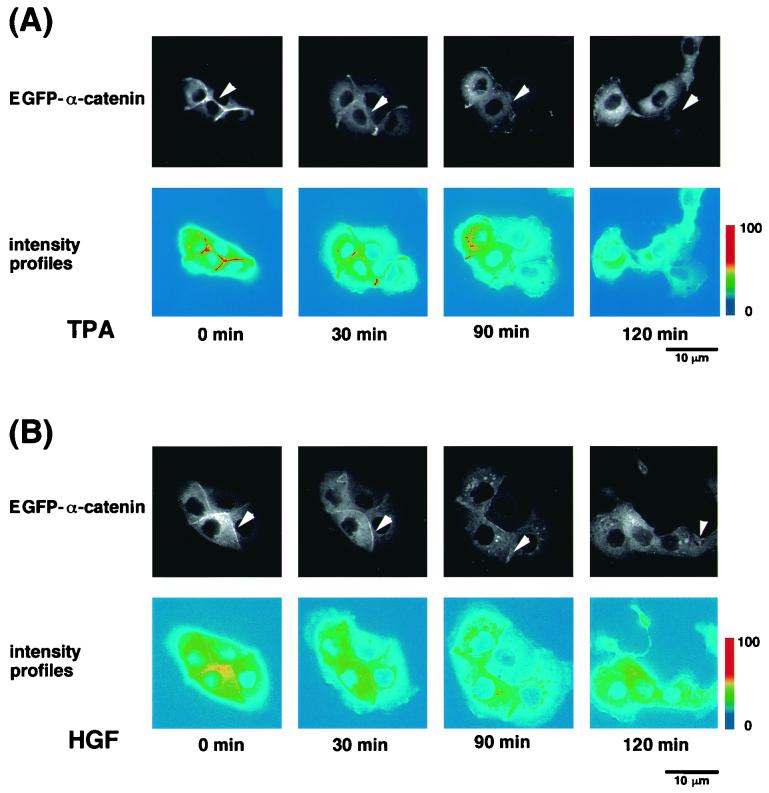

FIG. 2.

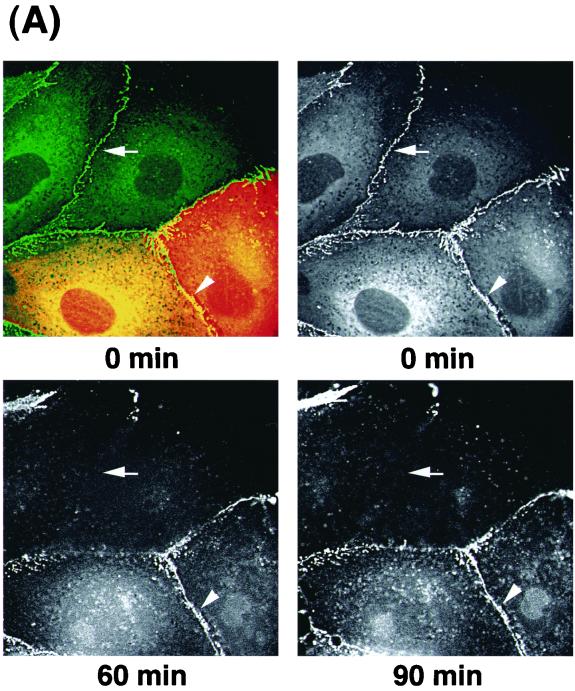

Dynamic relocalization of EGFP–α-catenin during TPA- or HGF-induced cell scattering. (A) Dynamic relocalization of EGFP–α-catenin during cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA. MDCKII cells stably expressing EGFP–α-catenin were starved for 24 h and then were stimulated with TPA (200 nM). (B) Dynamic relocalization of EGFP–α-catenin during cell-cell dissociation induced by HGF (50 pM). Representative time-lapse images are shown. Elapsed time is indicated at the bottom. Note that the amounts of EGFP–α-catenin at sites of cell-cell contact decreased before cell-cell dissociation (arrowhead). The intensity of EGFP–α-catenin fluorescence was quantified by pseudocolor using an ImagePro Plus system.

Immunofluorescence analysis.

MDCKII cells were starved for 24 h and incubated in DMEM containing TPA (200 nM) or HGF (50 pM) for 60 to 120 min at 37°C. The cells were fixed with 3.0% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min and then treated with PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 and 2 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml for 10 min. The fixed cells were stained with the indicated antibody as described previously (14).

Labeling cells with the lipid analogue, DiI.

Stock solutions (2.5 mg/ml) of DiI were made in ethanol and stored at −80°C (19). The cells were incubated in the presence of 20 μg of DiI/ml for 2 min at 37°C and then were fixed with 3.0% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min.

Immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously (14, 15). Briefly, subconfluent MDCKII or EL cells were harvested and lysed with lysis buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 10 μM (p-amidinophenyl)-methanesulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg of leupeptin/ml, 0.5% (wt/vol) Triton X-100, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MgCl2]. The lysates were mixed with the indicated antibody and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. The immunocomplex was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies.

Detection of GTP-bound Rac1 by use of GST-CRIB.

MDCKII cells (2 × 106 cells/10-cm-diameter dish) were seeded. At 24 h after seeding, the cells were starved for 24 h and then incubated in DMEM containing TPA (200 nM) for the indicated times. The cells were washed twice with ice-cold HEPES-buffered saline (containing 20 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl and 3 mM KCl), and lysed in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 10 μg of leupeptin/ml, 10 μg of aprotinin/ml, 10 μM (p-amidinophenyl)-methanesulfonyl fluoride]. The lysates were then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 7 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was incubated with purified GST-CRIB immobilized beads at 4°C for 1 h. The beads were washed three times with an excess of lysis buffer and eluted with Laemmli sample buffer. The eluates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Rac1 antibody.

Interaction of GST-IQGAP1 with MBP–IQGAP1-C.

The interaction of GST-IQGAP1 with MBP–IQGAP1-C was examined as previously described (15). Briefly, MBP alone, MBP–IQGAP1-N, or MBP–IQGAP1-C was mixed with affinity beads coated with GST or GST-IQGAP1. The beads were then washed, and the bound proteins were eluted by the addition of 20 mM glutathione. The eluates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-MBP antibody.

RESULTS

EGFP–α-catenin forms cadherin-catenin complexes and is localized at sites of cell-cell contact.

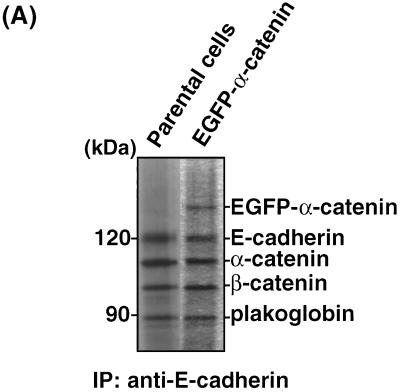

To investigate whether the Rac1-Cdc42-IQGAP1 system is involved in cell-cell dissociation during TPA- or HGF-induced cell scattering in MDCKII cells, we first examined the dynamics of α-catenin distribution in living cells, because IQGAP1 dissociates α-catenin from cadherin–β-catenin–α-catenin complexes (15). We constructed a cDNA encoding α-catenin tagged with EGFP at its amino terminus (EGFP–α-catenin). EGFP–α-catenin cDNA was stably expressed in MDCKII cells. EGFP–α-catenin had an apparent molecular mass of ∼130 kDa (Fig. 1A), consistent with the combined molecular masses of the fused proteins. When E-cadherin was immunoprecipitated from parental MDCKII cells, α-catenin, β-catenin, and plakoglobin were coimmunoprecipitated as previously described (1). When E-cadherin was immunoprecipitated from MDCKII cells stably expressing EGFP–α-catenin, EGFP–α-catenin as well as endogenous α-catenin were coimmunoprecipitated (Fig. 1A). EGFP–α-catenin accumulated at sites of cell-cell contact (Fig. 1B). The localization of EGFP–α-catenin at sites of cell-cell contact was indistinguishable from that of endogenous α-catenin in parental MDCKII cells. Since EGFP–α-catenin formed cadherin-catenin complexes and was localized at sites of cell-cell contact, we concluded that EGFP–α-catenin functioned as endogenous α-catenin.

FIG. 1.

Properties of EGFP–α-catenin similar to those of endogenous α-catenin. (A) Proteins in E-cadherin immunoprecipitates (IP) were compared between parental MDCKII cells and MDCKII cells stably expressing EGFP–α-catenin. Aliquots of the immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by silver staining. EGFP–α-catenin was coimmunoprecipitated with E-cadherin from MDCKII cells stably expressing EGFP–α-catenin. The molecular identity of each band was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-GFP, anti-E-cadherin, anti-α-catenin, anti-β-catenin, or anti-plakoglobin antibody (data not shown). (B) Endogenous α-catenin immunofluorescence in parental MDCKII cells and EGFP–α-catenin fluorescence in MDCKII cells stably expressing EGFP–α-catenin.

Dynamic relocalization of EGFP–α-catenin during cell scattering.

Using time-lapse microscopy over a 2-h period, we imaged MDCKII cells expressing EGFP–α-catenin to analyze the dynamics of EGFP–α-catenin distribution during TPA-induced cell scattering (Fig. 2A). Before stimulation with TPA, EGFP–α-catenin was localized at sites of cell-cell contact. Upon stimulation with TPA, cells extended lamellipodia and spread (15 to 30 min) and then started to detach from each other (2 to 6 h). Before complete cell-cell dissociation, the amounts of EGFP–α-catenin at sites of cell-cell contact gradually and partially decreased (Fig. 2A). The decrease in EGFP–α-catenin at sites of cell-cell contact was quantified by pseudocolor using an ImagePro Plus system (see Materials and Methods). As shown in the lower panel of Fig. 2A, the intensity of EGFP–α-catenin fluorescence at sites of cell-cell contact decreased before complete cell-cell dissociation (around 90 min after stimulation). Similar results were obtained when HGF was used instead of TPA (Fig. 2B).

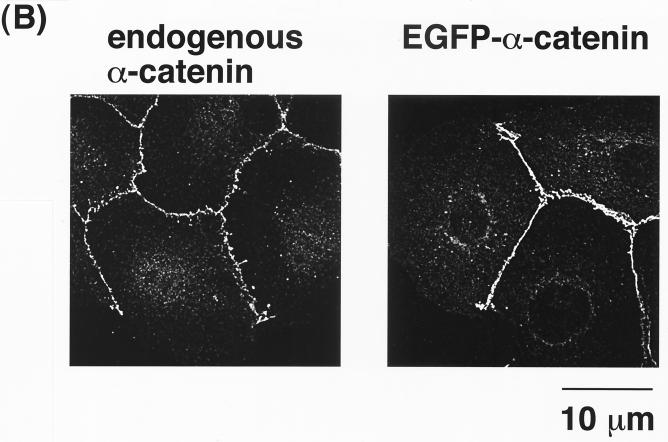

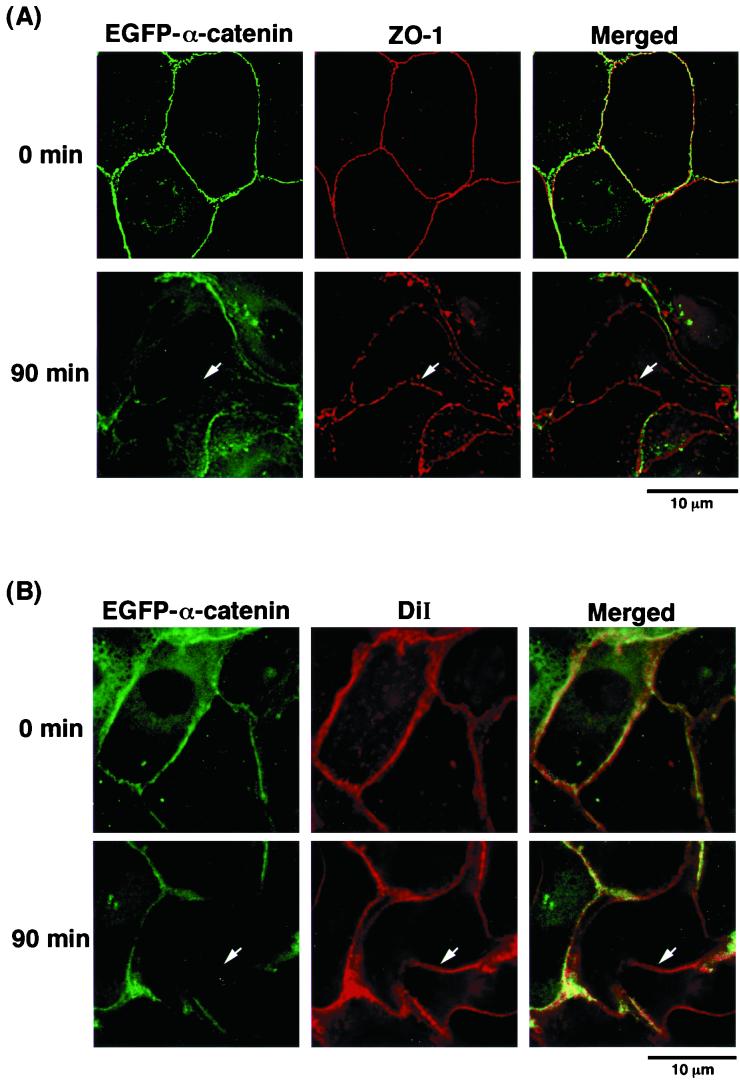

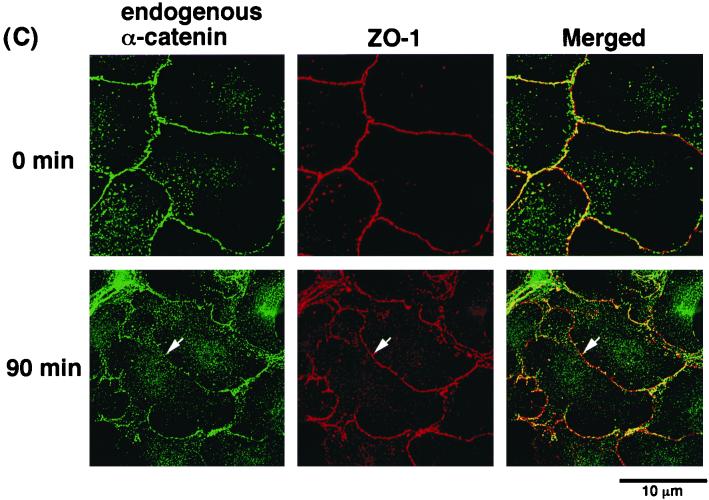

To examine whether cell-cell contact sites were still present when EGFP–α-catenin disappeared from sites of cell-cell contact during cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA, we examined the localization of ZO-1, a peripheral component of cell-cell adhesion, and a lipid analogue, DiI, which labels membranes. Before stimulation with TPA, both ZO-1 and EGFP–α-catenin were localized at sites of cell-cell contact (Fig. 3A). At 90 min after stimulation with TPA, ZO-1 was still present at sites of cell-cell contact, whereas EGFP–α-catenin had disappeared at some sites of cell-cell contact (Fig. 3A). Similarly, before stimulation with TPA, EGFP–α-catenin was colocalized with DiI at sites of cell-cell contact. At 90 min after stimulation with TPA, DiI remained present at these sites, but EGFP–α-catenin was missing at some sites of cell-cell contact (Fig. 3B). We confirmed that the dispersal of endogenous α-catenin in parental MDCKII cells preceded the loss of ZO-1 at sites of cell-cell contact (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that α-catenin is delocalized from cell-cell contact sites prior to cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA. The reason why the disappearance of α-catenin was not synchronously observed at sites of cell-cell contact might be that the responses of the cells to TPA or HGF were not synchronous.

FIG. 3.

Localization of ZO-1, a peripheral component of cell-cell adhesion, and the lipid analogue DiI, which labels membranes during cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA. (A) Localization of ZO-1 and EGFP–α-catenin during TPA-induced cell-cell dissociation. Serum-deprived MDCKII cells expressing EGFP–α-catenin were stimulated with TPA (200 nM). At 90 min after the start of the stimulation with TPA, the cells were fixed and stained with anti-ZO-1 antibody. Note that EGFP–α-catenin disappeared from sites of cell-cell contact before cell-cell dissociation, whereas ZO-1 was still present at these sites (arrow). (B) DiI was still present at sites of cell-cell contact when EGFP–α-catenin had already disappeared from these sites during TPA-induced cell scattering (arrow). (C) Localization of ZO-1 and endogenous α-catenin during TPA-induced cell-cell dissociation. At 90 min after the addition of TPA, the cells were doubly stained with anti-α-catenin and anti-ZO-1 antibodies. Endogenous α-catenin disappeared from sites of cell-cell contact before cell-cell dissociation, whereas ZO-1 was still present at the contact sites (arrow).

Dissociation of ECFP–α-catenin from E-cadherin–GFP during TPA-induced cell scattering.

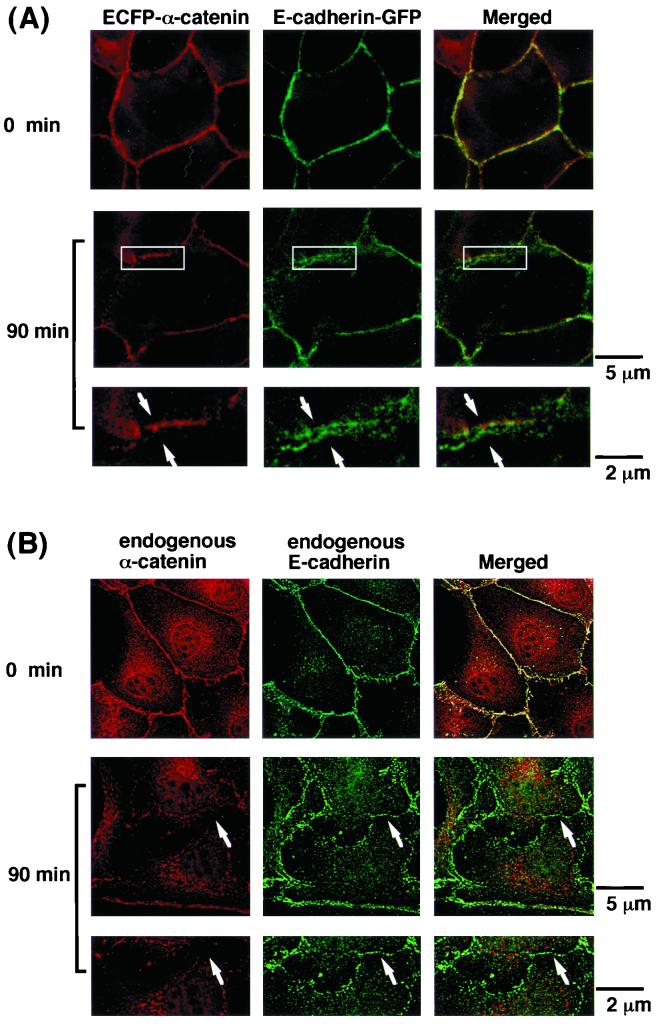

To further investigate the dynamics of α-catenin distribution during cell-cell dissociation, we examined the dynamics of both α-catenin and E-cadherin in the same cells by time-lapse microscopic observation of MDCKII cells stably expressing both ECFP-tagged α-catenin and E-cadherin–GFP (1). Before stimulation with TPA, ECFP–α-catenin and E-cadherin–GFP were colocalized at sites of cell-cell contact. At 90 min after the start of stimulation with TPA, some sites of cell-cell contact were observed in which ECFP–α-catenin had disappeared but E-cadherin–GFP still remained (Fig. 4A). Then, E-cadherin–GFP gradually disappeared from those sites of cell-cell contact (data not shown). Similar results were obtained with HGF instead of TPA (data not shown). Thus, it is likely that there is a loss of colocalization of ECFP–α-catenin with E-cadherin–GFP at specific sites of cell-cell contact. Since the responses of the cells to TPA or HGF were not synchronous and dissociated cadherin-catenin complexes were degraded quickly, the dissociation of cadherin and α-catenin was very temporal and was composed of partial events (see Discussion). We also observed a loss of colocalization of endogenous α-catenin with endogenous E-cadherin in the fixed parental MDCKII cells at 90 min after the start of stimulation with TPA (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, we examined the localization of β-catenin during TPA-induced cell scattering. Before stimulation with TPA, β-catenin and E-cadherin or β-catenin and α-catenin were colocalized at sites of cell-cell contact. At 90 min after the start of stimulation with TPA, β-catenin and E-cadherin were colocalized (Fig. 4C). In contrast, α-catenin had disappeared but β-catenin still remained at some sites of cell-cell contact (Fig. 4D). Similar results were obtained upon stimulation with HGF instead of TPA (data not shown). Thus, it is likely that there is a loss of colocalization of α-catenin with E-cadherin–β-catenin complexes at specific sites of cell-cell contact.

FIG. 4.

Loss of colocalization of α-catenin and E-cadherin during TPA-induced cell-cell dissociation. (A) MDCKII cells stably expressing both ECFP–α-catenin (red; using pseudocolor) and E-cadherin–GFP (green) were starved for 24 h and then were stimulated with TPA (200 nM). Before the stimulation, ECFP–α-catenin and E-cadherin–GFP were colocalized at sites of cell-cell contact. After 90 min of incubation with TPA, some sites of cell-cell contact where E-cadherin–GFP was still present at the plasma membrane but from which ECFP–α-catenin had disappeared (arrow) were observed. The regions in white boxes are shown magnified below. These results are representative of six independent experiments. (B) At 90 min after the start of stimulation with TPA, parental MDCKII cells were fixed and doubly stained with rabbit anti-α-catenin polyclonal and rat anti-E-cadherin monoclonal (ECCD-2) antibodies. Similar to the case of ECFP–α-catenin and E-cadherin–GFP, dissociation of endogenous α-catenin from endogenous E-cadherin was observed at some sites of cell-cell contact (arrow). (C) MDCKII cells were doubly stained with rat anti-E-cadherin monoclonal (ECCD-2) and rabbit anti-β-catenin polyclonal antibodies. (D) MDCKII cells were doubly stained with rabbit anti-α-catenin polyclonal and mouse anti-β-catenin monoclonal antibodies. At 90 min after stimulation with TPA, dissociation of α-catenin from β-catenin was observed at some sites of cell-cell contact (arrow). These results are representative of three independent experiments.

Effects of Rho family GTPases on the disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin during cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA.

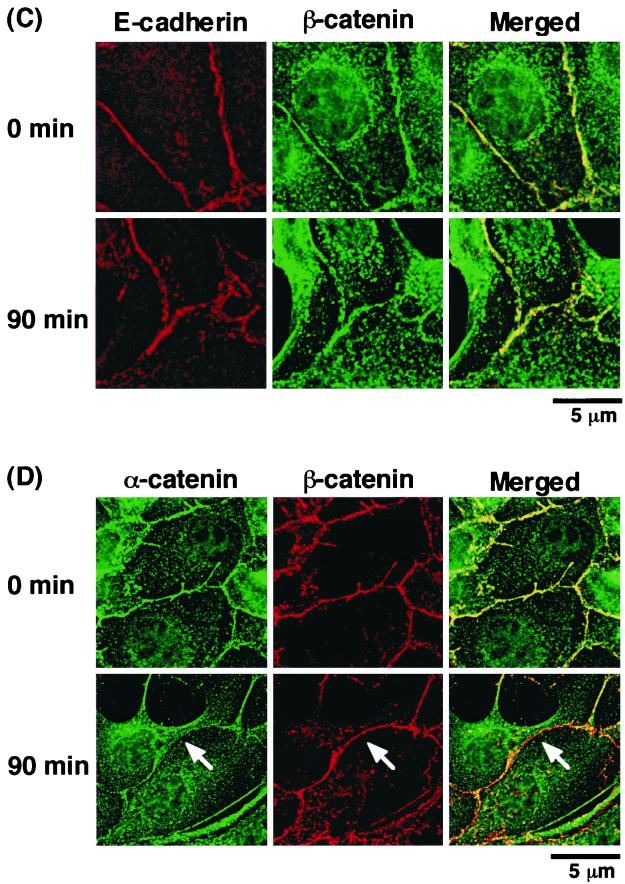

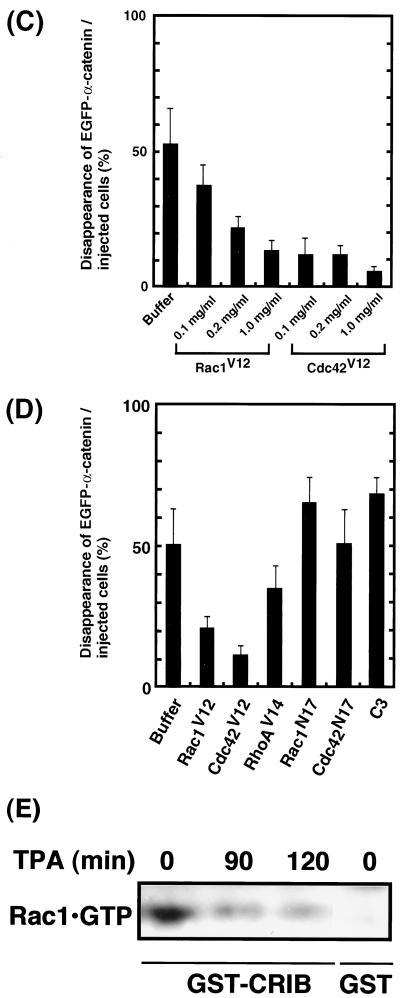

We and others have recently found that Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA participate in the regulation of cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion (3, 13, 30; for a review, see reference 10). Therefore, we examined the effects of the Rho family GTPases on the disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin during cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA. Constitutively active Rac1 (Rac1V12) inhibited the disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact and blocked cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained by using constitutively active Cdc42 (Cdc42V12) instead of Rac1V12 (Fig. 5B). Rac1V12 and Cdc42V12 inhibited TPA-induced disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5C). Although constitutively active RhoA (RhoAV14) partially inhibited the disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin and the cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA, cell morphology was dramatically changed (data not shown). Thus, interpretation of the effect of RhoAV14 is difficult. Dominant-negative Rac1 (Rac1N17) and dominant-negative Cdc42 (Cdc42N17), mutant proteins that preferentially bind GDP rather than GTP and are thought to exist constitutively in the GDP-bound form in cells, did not inhibit the disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin (Fig. 5D). C. botulinum C3 toxin (C3), an inhibitor of Rho, also did not inhibit the disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin. Similar results were obtained when HGF was used instead of TPA (data not shown). The effects of small GTPases on the localization of endogenous α-catenin were similar to those on the localization of EGFP–α-catenin (data not shown). These results are consistent with our previous results showing that activated Rac1 and Cdc42 positively regulate E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion by inhibiting the function of IQGAP1, which causes the dissociation of α-catenin from the cadherin-catenin complexes (5, 15).

FIG. 5.

Effects of small GTPases on TPA-induced disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact. (A) Inhibition of TPA-induced disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin and cell-cell dissociation by constitutively active Rac1 (Rac1V12). Stimulation of the cells with TPA induced the disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact before cell-cell dissociation during cell scattering (arrow). In contrast, microinjection of Rac1V12 (0.2 mg/ml) with rhodamine-labeled dextran (red) inhibited both disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact and cell-cell dissociation (arrowhead). The time after stimulation is indicated. (B) Similar results were obtained by using constitutively active Cdc42 (Cdc42V12; 0.2 mg/ml) instead of Rac1V12. (C) Rac1V12 and Cdc42V12 inhibited TPA-induced disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin in a dose-dependent manner. Indicated concentrations of Rac1V12 and Cdc42V12 were microinjected as done for panels A and B. At 30 min after the microinjection of the indicated protein, the cells were stimulated with TPA (200 nM) and incubated for 90 min. Data are means ± standard errors of the means of triplicate determinations. (D) Effects of Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA mutants on TPA-induced disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin. At 30 min after the microinjection of the indicated protein (small GTPase, 0.2 mg/ml each; C3, 0.1 mg/ml), the cells were stimulated with TPA (200 nM) and incubated for 90 min. Data are means ± standard errors of the means of triplicate determinations. (E) MDCKII cells were incubated with TPA (200 nM) for the indicated times. The cells were lysed, and the lysates were incubated with GST-CRIB. The proteins bound to GST-CRIB were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Rac1 antibody. These results are representative of five independent experiments.

To examine whether the amount of GTP-bound Rac1 decreases when the cell-cell adhesion is perturbed upon stimulation of the cells with TPA, we measured the amounts of GTP-bound Rac1 by use of the CRIB of PAK, which specifically binds to GTP-bound forms of Rac1 and Cdc42. Before stimulation of cells with TPA, Rac1 in its active GTP-bound form could be detected (Fig. 5E). At 90 and 120 min after stimulation, the Rac1-GTP level became less than the basal level (Fig. 5E). Total Rac1 in lysates did not change during this process (data not shown). Regarding Cdc42, we could not detect Cdc42-GTP under the same conditions, probably due to the fact that smaller amounts of Cdc42 than Rac1 are expressed in MDCKII cells (data not shown).

Dynamics of EGFP-IQGAP1 during cell scattering.

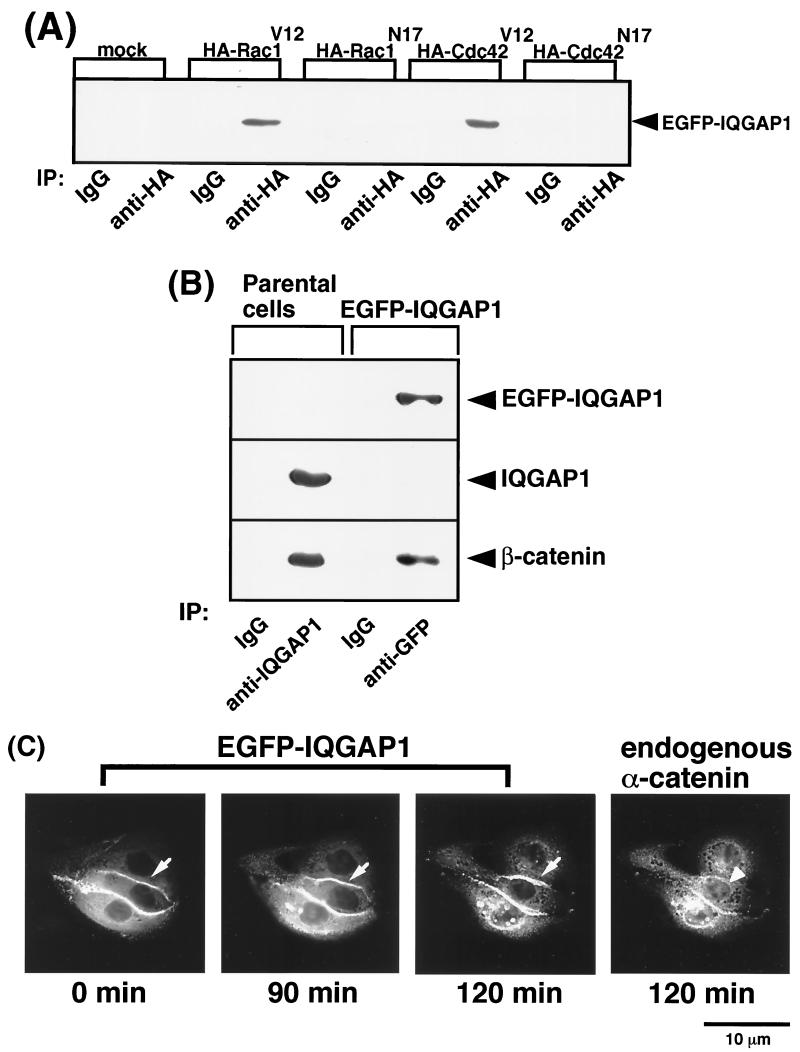

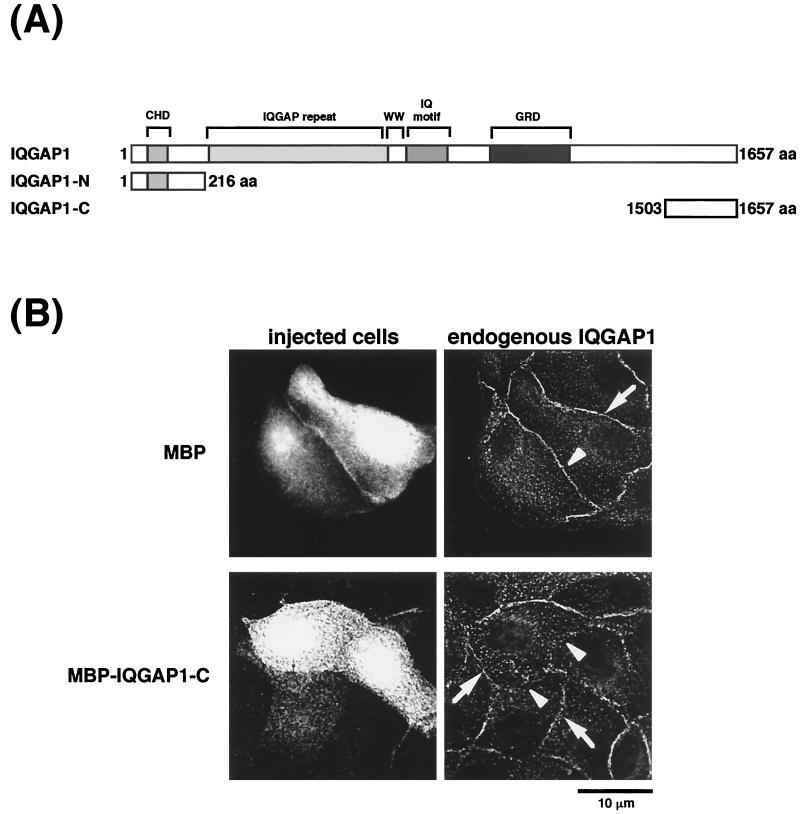

IQGAP1 is localized at sites of cell-cell contact where it forms a complex with E-cadherin and β-catenin, which results in weak adhesion between cells (for a review, see reference 10). To examine directly the dynamics of IQGAP1 distribution, we constructed a cDNA of IQGAP1 tagged with EGFP at its amino terminus (EGFP-IQGAP1). At first, to examine whether EGFP-IQGAP1 specifically binds activated Rac1, EGFP-IQGAP1 was cotransfected together with either HA-tagged Rac1V12 or HA-Rac1N17 into L cells expressing E-cadherin (EL cells), and then immunoprecipitation by anti-HA antibody was performed. EGFP-IQGAP1 was coimmunoprecipitated with HA-Rac1V12, but not with HA-Rac1N17 (Fig. 6A). Similar results were obtained using HA-Cdc42V12 instead of HA-Rac1V12 (Fig. 6A). Next, EGFP-IQGAP1 cDNA was stably expressed in MDCKII cells. When IQGAP1 was immunoprecipitated from parental MDCKII cells, β-catenin was coimmunoprecipitated as previously described (15). When EGFP-IQGAP1 was immunoprecipitated from MDCKII cells stably expressing EGFP-IQGAP1 by anti-GFP antibody, β-catenin was coimmunoprecipitated (Fig. 6B). Since EGFP-IQGAP1 bound Rac1V12, Cdc42V12, and β-catenin and was localized at sites of cell-cell contact (see below), we concluded that EGFP-IQGAP1 functioned as endogenous IQGAP1. Using time-lapse microscopy over a 2-h period, we imaged MDCKII cells expressing EGFP-IQGAP1 to analyze the dynamics of EGFP-IQGAP1 distribution during TPA-induced cell scattering (Fig. 6C). Before stimulation with TPA, EGFP-IQGAP1 as well as endogenous IQGAP1 were localized at the cytosol and at sites of cell-cell contact. At 2 h after stimulation with TPA, EGFP-IQGAP1 did not decrease at sites of cell-cell contact or was rather likely to increase a little (Fig. 6C). In contrast, endogenous α-catenin had disappeared from the intercellular junction. Then, EGFP-IQGAP1 gradually disappeared from the plasma membrane during cell scattering (data not shown). Similar results were obtained when HGF was used instead of TPA (data not shown). These results raise the possibility that IQGAP1–β-catenin complexes increase and α-catenin–β-catenin complexes decrease upon stimulation with TPA. To test this possibility, we examined whether the amounts of β-catenin that coimmunoprecipitated with IQGAP1 were affected by the treatment of cells with TPA. As shown in Fig. 6D, the association of β-catenin with IQGAP1 increased at 90 to 120 min after stimulation with TPA. Although we tried to examine whether α-catenin–β-catenin complexes decreased upon stimulation with TPA, we could not detect apparent changes of the amounts of α-catenin–β-catenin complexes (data not shown, and see Discussion). We also examined by immunoprecipitation of IQGAP1 whether the amounts of IQGAP1-Rac1 complexes were affected upon stimulation with TPA. Before stimulation with TPA, IQGAP1 was associated with Rac1. In contrast to IQGAP1–β-catenin complexes, the association of Rac1 with IQGAP1 decreased upon stimulation with TPA (Fig. 6D). These results suggest that activated Rac1 decreased during TPA-induced cell scattering and are consistent with the results in Fig. 5E.

FIG. 6.

Dynamics of EGFP-IQGAP1 during TPA-induced cell scattering. (A) EGFP-IQGAP1 and either HA-tagged Rac1 or Cdc42 were cotransfected into EL cells. EGFP-IQGAP1 was coimmunoprecipitated with HA-Rac1V12 and HA-Cdc42V12. (B) EGFP-IQGAP1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) by anti-GFP antibody from MDCKII cells stably expressing EGFP-IQGAP1. β-catenin was coimmunoprecipitated with EGFP-IQGAP1. (C) Dynamics of EGFP-IQGAP1 during cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA. Representative time-lapse images are shown. At 2 h after stimulation with TPA, the cells were fixed and stained with anti-α-catenin antibody. Note that EGFP-IQGAP1 (arrow) at sites of cell-cell contact did not decrease differently from endogenous α-catenin (arrowhead). (D) The amounts of IQGAP1–β-catenin and IQGAP1-Rac1 complexes upon stimulation with TPA. MDCKII cells were starved for 24 h and stimulated with TPA (200 nM). IQGAP1 was immunoprecipitated (I.P.) by anti-IQGAP1 antibody from MDCKII cells. Aliquots of the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting (I.B.) with anti-IQGAP1, anti-β-catenin, and anti-Rac1 antibodies. These results are representative of five independent experiments.

IQGAP1-C delocalizes endogenous IQGAP1.

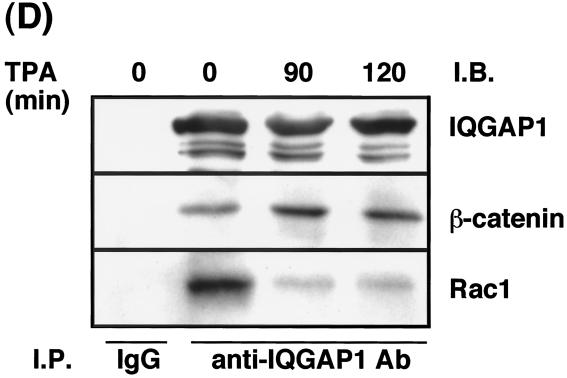

Next, we examined whether IQGAP1 is involved in the disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin during cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA. To screen for a putative dominant-negative mutant of IQGAP1, we constructed MBP–IQGAP1-N (aa 1 to 216) and MBP–IQGAP1-C (aa 1503 to 1657) (Fig. 7A). When MBP–IQGAP1-C was microinjected into MDCKII cells, endogenous IQGAP1 was delocalized from sites of cell-cell contact at 60 min after microinjection (Fig. 7B). On the other hand, when MBP or MBP–IQGAP1-N was microinjected into MDCKII cells, endogenous IQGAP1 remained localized at cell-cell contacts. The effect of IQGAP1-C on the delocalization of endogenous IQGAP1 was observed more strongly between two microinjected cells than between one microinjected cell and one not microinjected (Fig. 7C). Next, the effect of MBP–IQGAP1-C on the localization of EGFP–α-catenin was examined. When endogenous IQGAP1 was delocalized from sites of cell-cell contact, EGFP–α-catenin remained localized at these sites (Fig. 7D). Endogenous α-catenin also remained at sites of cell-cell contact under the same conditions (data not shown). These results suggest that MBP–IQGAP1-C directly or indirectly interacts with endogenous IQGAP1, delocalizes endogenous IQGAP1 from sites of cell-cell contact, and functions as a putative dominant-negative mutant of IQGAP1. To investigate this possibility in detail, we measured the interaction of GST–full-length IQGAP1 with MBP, MBP–IQGAP1-N, or MBP–IQGAP1-C. MBP–IQGAP1-C specifically and directly interacted with GST–full-length IQGAP1, but not with GST in vitro (Fig. 7E), whereas MBP and MBP–IQGAP1-N did not interact with GST–full-length IQGAP1. These results support the above possibility that MBP–IQGAP1-C specifically and directly binds IQGAP1 and functions as a putative dominant-negative mutant of IQGAP1 through delocalizing endogenous IQGAP1 from sites of cell-cell contact.

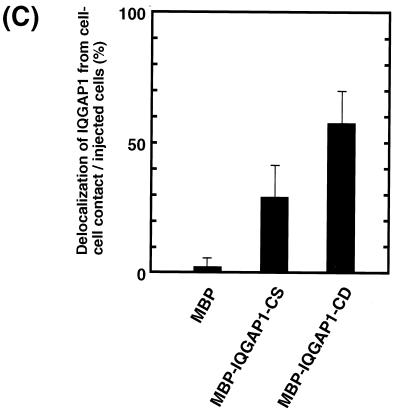

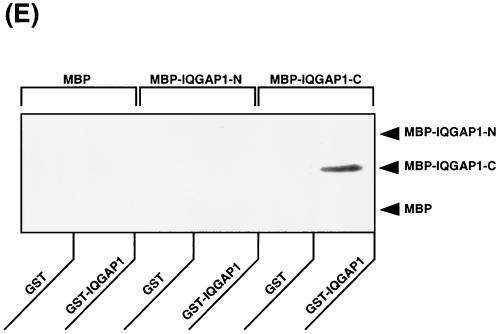

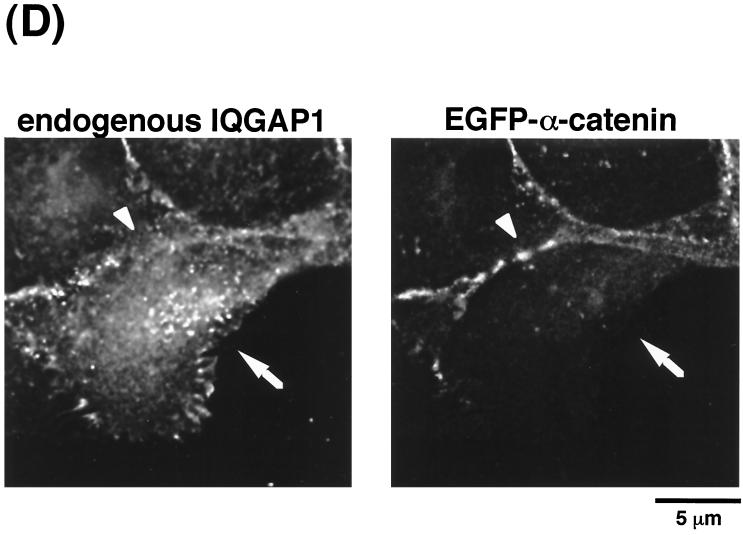

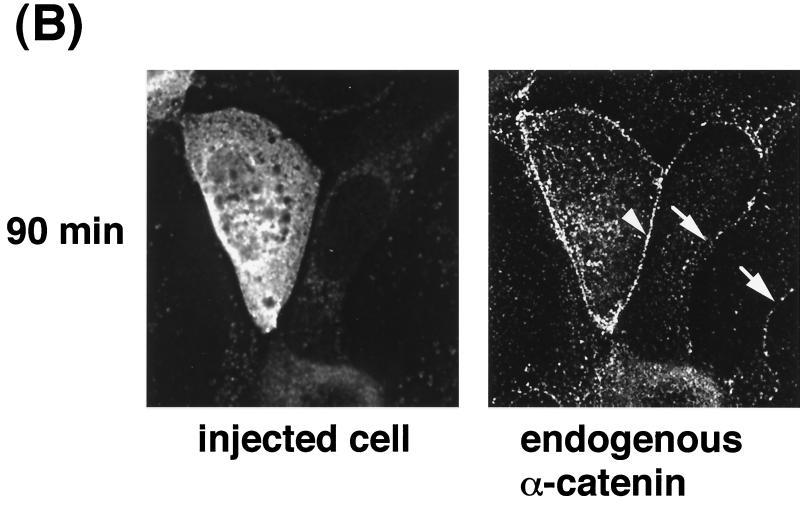

FIG. 7.

Delocalization of IQGAP1 by IQGAP1-C (aa 1503 to 1657). (A) Domain diagram of IQGAP1 and MBP-IQGAP1 mutants. IQGAP1 has a variety of domains, including a calponin homologous domain (CHD), IQGAP1 repeat (six repeated sequences), WW domain, IQ motif, and Ras GAP-related domain (GRD). (B) Microinjection of MBP–IQGAP1-C (aa 1503 to 1657) delocalized endogenous IQGAP1 from sites of cell-cell contact. MBP or MBP–IQGAP1-C (1 mg/ml each) was injected into MDCKII cells. At 60 min after injection, the cells were fixed and endogenous IQGAP1 was then stained with anti-IQGAP1-N antibody, which recognizes the N terminus (aa 1 to 216) of IQGAP1. Microinjection of MBP–IQGAP1-C delocalized endogenous IQGAP1 from sites of cell-cell contact, but that of MBP did not do so. Arrowheads indicate the sites of cell-cell contact between two injected cells, and arrows indicate the sites of cell-cell contact between one injected cell and one not injected. (C) The effect of IQGAP1-C on the delocalization of endogenous IQGAP1 was observed more strongly between two microinjected cells (indicated as MBP–IQGAP1-CD) than between one microinjected cell and one not microinjected (indicated as MBP–IQGAP1-CS). Data are means ± standard errors of the means of triplicate determinations. (D) MBP–IQGAP1-C was microinjected into an MDCKII cell expressing EGFP–α-catenin (arrow). At 60 min after the injection, the cells were fixed and endogenous IQGAP1 was then stained with anti-IQGAP1 antibody. MBP–IQGAP1-C induced the disappearance of endogenous IQGAP1 from sites of cell-cell contact, whereas EGFP–α-catenin remained localized at sites of cell-cell contact (arrowhead). (E) MBP, MBP–IQGAP1-N, or MBP–IQGAP1-C was mixed with affinity beads coated with either GST or GST-IQGAP1. After the beads had been washed, the bound proteins were eluted by the addition of 20 mM glutathione. The eluates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-MBP antibody. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

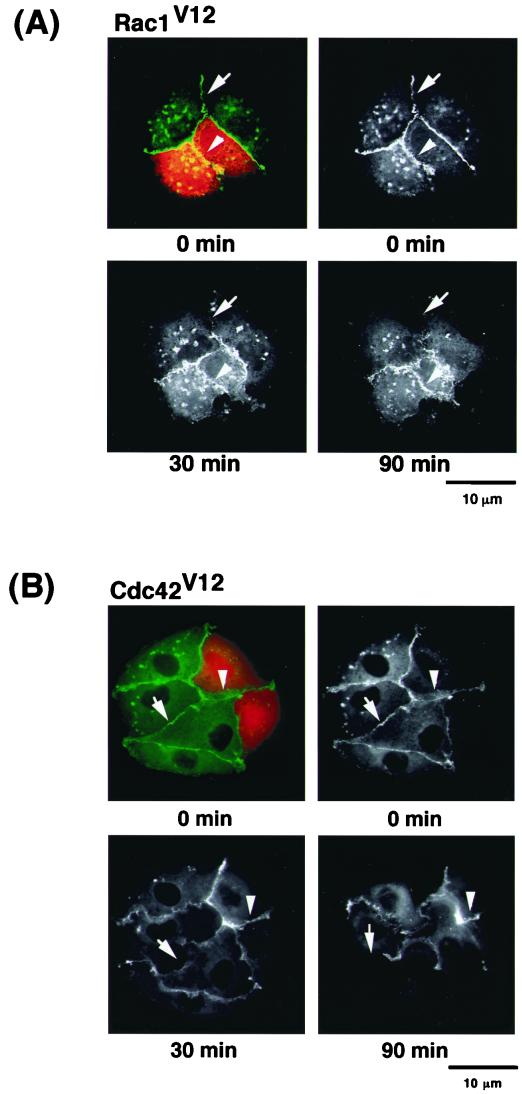

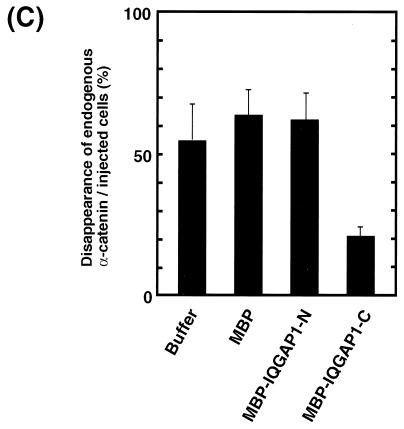

Effect of IQGAP1-C on the disappearance of α-catenin during cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA.

The effect of IQGAP1-C on the disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin during cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA was examined by time-lapse imaging. MBP–IQGAP1-C inhibited TPA-induced disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact (Fig. 8A). The effect of IQGAP1-C on the disappearance of endogenous α-catenin during TPA-induced cell scattering was also examined. MBP–IQGAP1-C inhibited the disappearance of endogenous α-catenin as well as EGFP–α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact induced by TPA (Fig. 8B and C). MBP or MBP–IQGAP1-N did not prevent the disappearance of α-catenin during cell-cell dissociation (Fig. 8C). These results suggest that IQGAP1 is involved in the disappearance of α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact during cell-cell dissociation and cell scattering.

FIG. 8.

Effect of IQGAP1-C on TPA-induced disappearance of α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact. (A) Inhibition of TPA-induced disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin by IQGAP1-C. Stimulation of the cells with TPA induced the disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact before cell-cell dissociation during cell scattering (arrow). In contrast, microinjection of MBP–IQGAP1-C (1 mg/ml) with rhodamine-labeled dextran (red) inhibited the disappearance of EGFP–α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact (arrowhead). The results are representative of 10 independent experiments. (B) Inhibition of TPA-induced disappearance of endogenous α-catenin by IQGAP1-C. At 30 min after the microinjection of MBP–IQGAP1-C (1 mg/ml), the cells were stimulated with TPA (200 nM) and then incubated for 90 min. Thereafter, the cells were fixed and stained with anti-α-catenin antibody. TPA induced the disappearance of α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact during cell scattering (arrow). In contrast, microinjection of IQGAP1-C (1 mg/ml) with rhodamine-labeled dextran inhibited the disappearance of α-catenin from sites of cell-cell contact (arrowhead). (C) IQGAP1-C, but neither MBP alone nor IQGAP1-N, inhibited TPA-induced disappearance of endogenous α-catenin. Data are means ± standard errors of the means of triplicate determinations.

DISCUSSION

Dynamic rearrangement of cadherin-catenin complexes.

Although α-catenin is considered to be a key protein in cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion, little is known about the dynamics of α-catenin during this process. In this study, using EGFP–α-catenin, we found that α-catenin disappeared from sites of cell-cell contact prior to cell-cell dissociation during cell scattering and confirmed that E-cadherin also disappeared from sites of cell-cell contact during cell scattering (data not shown; see reference 25). Furthermore, we found that α-catenin dissociated from cadherin at specific sites of cell-cell contact prior to the loss of E-cadherin from those sites. Dissociation of α-catenin from E-cadherin has been described as occurring during passage of normal human breast epithelial cells in culture (33). At early passages, α-catenin is colocalized with E-cadherin and β-catenin at sites of cell-cell contact. In contrast, at later passages, α-catenin appears in the cytoplasm, whereas E-cadherin and β-catenin are still localized at sites of cell-cell contact. In addition, treatment of leukemia cells expressing E-cadherin with pervanadate, a potent tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor, results in a reduction in E-cadherin activity and in the dissociation of α-catenin from the cadherin-catenin complexes (23). In this study, we attempted to detect the dissociation of α-catenin from the cadherin-catenin complexes during TPA- or HGF-induced cell-cell dissociation by immunoprecipitation of E-cadherin. However, we were unable to detect changes, probably due to the fact that the responses of the cells to TPA or HGF were not synchronous and that dissociated cadherin-catenin complexes are degraded quickly (32).

Rho GTPase activities during remodeling of cell-cell adhesion.

Judging from time-lapse video microscopic analysis at cell-cell contact, there exists a mixture of stable (strong) and dynamically remodeled (weak) adhesive sites of cell-cell contact, even in a single cell-cell contact when cells are unstimulated (1). In this study, we showed that Rac1-GTP levels decreased during cell scattering induced by TPA and that constitutively active Rac1, but not dominant-negative Rac1, inhibited both the disappearance of α-catenin from intercellular junctions and cell-cell dissociation induced by TPA. Taken together, these results suggest that Rac1 is activated at strong adhesive sites of cell-cell contact and is inactivated at weak adhesive sites of cell-cell contact. Thus, the activity of Rac1 at sites of cell-cell contact might be tightly regulated at specific sites of cell-cell adhesion. Cycling between activated and inactivated forms of Rac1 seems to play a pivotal role in the regulation of cell-cell adhesion.

Several groups have recently reported that integrin-mediated cell-substratum adhesion induces the activation of the Rho family GTPases (26, 28). The engagement of integrins with fibronectin activates Cdc42, which subsequently activates Rac1 during cell spreading 5 min after the attachment of cells to the substratum (26). Taking these data together, we speculate that E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion induces the activation of the Rho family GTPases. Recent observations support this idea. The engagement of E-cadherins in homophilic cell-cell interaction results in a rapid phosphotidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase)-dependent activation of Akt/PKB in MDCKII cells (24). Activated PI 3-kinase can activate Rac1 (8, 12, 27). Therefore, it will be important to examine whether cell-cell contact activates the Rho family GTPases. Indeed, by measuring the level of Rac1-GTP using GST-CRIB, we have found that the amount of Rac1-GTP increased during cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion and that a neutralizing antibody against E-cadherin (DECMA-1) inhibited Rac1 activation (M. Nakagawa and K. Kaibuchi, unpublished data). However, since we measured only the total amounts of GTP-bound Rac1 in cells, we could not determine at which sites of cell-cell adhesion Rac1 was activated. Further study is necessary to monitor and visualize the Rac1 activity at specific stages and sites of cell-cell adhesion.

Potential regulation of cell-cell dissociation during cell scattering by the Rac1-Cdc42-IQGAP1 system.

IQGAP1 negatively regulates E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion through interacting with β-catenin to cause the dissociation of α-catenin from the cadherin-catenin complexes. Activated Rac1 and Cdc42 positively regulate E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion by inhibiting the interaction of IQGAP1 with β-catenin (for a review, see reference 10). Based on these studies and the fact that ∼50% of E-cadherin appears to be connected to the actin cytoskeleton, probably by α-catenin, but that the rest appears to be free from cadherin-catenin complexes (29), we suggest that E-cadherin exists in a dynamic equilibrium between the E-cadherin–β-catenin–α-catenin complex and the E-cadherin–β-catenin–IQGAP1 complex at sites of cell-cell contact. The ratio between the two complexes could be a determinant of strength of the E-cadherin-mediated adhesion. Before stimulation with TPA or HGF, total amounts of activated Rac1 and Cdc42 at sites of cell-cell contact are relatively high and activated Rac1 and Cdc42 directly bind IQGAP1, thereby inhibiting the interaction of IQGAP1 with β-catenin and shifting the equilibrium towards the E-cadherin–β-catenin–α-catenin complex. Under these conditions, the ratio of the E-cadherin–β-catenin–α-catenin complex to the E-cadherin–β-catenin–IQGAP1 complex is high, leading to strong adhesion. Upon stimulation with TPA or HGF, total amounts of inactivated Rac1 and Cdc42 at sites of cell-cell contact increase, resulting in the dissociation of IQGAP1 from Rac1 and Cdc42. IQGAP1 is freed from Rac1 and Cdc42 and interacts with β-catenin to dissociate α-catenin from the cadherin-catenin complexes. In this case, the ratio of the E-cadherin–β-catenin–IQGAP1 complex to the E-cadherin–β-catenin–α-catenin complex is high, leading to weak adhesion and cell-cell dissociation. Such models may account for the dynamic relocalization of α-catenin and a part of the mechanism underlying the E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion during cell scattering. Consistently, we found here that the Rac1-GTP levels decreased after stimulation with TPA and that Rac1-IQGAP1 complexes decreased, while the IQGAP1–β-catenin complexes increased during action of TPA.

Mechanism of inhibition of endogenous IQGAP1 action by IQGAP1-C.

We showed that IQGAP1-C (aa 1503 to 1657) specifically delocalized endogenous IQGAP1 from sites of cell-cell contact and found that IQGAP1-C became diffusely localized in the cytosol and not at sites of cell-cell contact (data not shown). In addition, we found that IQGAP1-C, which possesses a coiled-coil structure, directly bound full-length IQGAP1 in vitro. These results raise the possibility that IQGAP1 forms an oligomer and that its oligomerization is essential for targeting sites of cell-cell adhesion, possibly through binding to β-catenin and E-cadherin. If so, IQGAP1-C may inhibit the oligomerization of full-length IQGAP1 molecules. Hetero-oligomer composed of full-length IQGAP1 and IQGAP1-C may have lower affinity to β-catenin and E-cadherin than the homo-oligomer, leading to delocalization of IQGAP1 from sites of cell-cell contact. Therefore, IQGAP1-C could function as a dominant-negative mutant of IQGAP1.

Alternatively, since it takes about 60 min for IQGAP1-C to delocalize endogenous IQGAP1, IQGAP1-C may inhibit the transport of IQGAP1 to sites of cell-cell contacts. Further work will be required to elucidate how IQGAP1-C inhibits the function of endogenous IQGAP1.

Other physiological processes in which IQGAP1 functions.

We have proposed that the Rac1-Cdc42-IQGAP1 system dynamically regulates cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion (10). However, it remains to be demonstrated in which physiological processes this Rac1-Cdc42-IQGAP1 system is involved. In this study, we demonstrated that IQGAP1 functions in cell-cell dissociation during cell scattering. Besides cell scattering, dynamic rearrangement in E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion underlies compaction of the eight-cell embryo, in which the embryo develops from a collection of loosely adherent blastomeres into a tightly packed epithelium called the blastocyst (4). Gastrulation provides another example of dynamic rearrangement of the cadherin-catenin complexes. In sea urchin embryos, cadherin is localized at sites of cell-cell contact throughout gastrulation, whereas α-catenin staining at the sites decreases markedly (17, 18). Further studies must determine whether IQGAP1 is involved in the regulation of cell-cell adhesion during compaction and gastrulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank W. James Nelson for providing the construct harboring E-cadherin–GFP and for helpful discussion during the course of our work; Akira Nagafuchi and Shoichiro Tsukita for providing MDCKII cells, EL cells, cDNA encoding mouse α-catenin, and antibody against E-cadherin (ECCD-2); Masatoshi Takeichi for providing antibody against E-cadherin (ECCD-2); Shohei Mitani for providing anti-GFP antibody (mFX73); Takahiro Nagase, Nobuo Nomura, and the Kazusa DNA Research Institute for providing cDNA of IQGAP1 and support from a cDNA Research Program; Alan Hall for providing pGEX-C3; Yoshiharu Matsuura for providing the baculovirus of GST-IQGAP1; and Toshikazu Nakamura for providing HGF.

This work was supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan (1999) and by grants from the program Research for the Future of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Human Frontier Science Program, and Kirin Brewery Company Limited.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams C L, Chen Y T, Smith S J, Nelson W J. Mechanisms of epithelial cell-cell adhesion and cell compaction revealed by high-resolution tracking of E-cadherin-green fluorescent protein. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1105–1119. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.4.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams C L, Nelson W J. Cytomechanics of cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:572–577. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braga V, Machesky L M, Hall A, Hotchin N A. The small GTPases rho and rac are required for the establishment of cadherin-dependent cell-cell contacts. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1421–1431. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming T P, Johnson M H. From egg to epithelium. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1988;4:459–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukata M, Kuroda S, Nakagawa M, Kawajiri A, Itoh N, Shoji I, Matsuura Y, Yonehara S, Kikuchi A, Kaibuchi K. Cdc42 and Racl regulate the interaction of IQGAP1 with β-catenin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26044–26050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gumbiner B M. Regulation of cadherin adhesive activity. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:399–404. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartmann G, Weidner K M, Schwarz H, Birchmeier W. The motility signal of scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor mediated through the receptor tyrosine kinase met requires intracellular action of Ras. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21936–21939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawkins P T, Eguinoa A, Qiu R G, Stokoe D, Cooke F T, Walters R, Wennstrom S, Claesson-Welsh L, Evans T, Symons M, Stephens L. PDGF stimulates an increase in GTP-Rac via activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Curr Biol. 1995;5:393–403. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hordijk P L, ten Klooster J P, van der Kammen R A, Michiels F, Oomen L C, Collard J G. Inhibition of invasion of epithelial cells by Tiam1-Rac signaling. Science. 1997;278:1464–1466. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5342.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaibuchi K, Kuroda S, Fukata M, Nakagawa M. Regulation of cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion by the Rho family GTPases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:591–596. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kodama A, Takaishi K, Nakano K, Nishioka H, Takai Y. Involvement of Cdc42 small G protein in cell-cell adhesion, migration and morphology of MDCK cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:3996–4006. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotani K, Yonezawa K, Hara K, Ueda H, Kitamura Y, Sakaue H, Ando A, Chavanieu A, Calas B, Grigorescu F, Nishiyama M, Waterfield M, Kasuga M. Involvement of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in insulin- or IGF-1-induced membrane ruffling. EMBO J. 1994;13:2313–2321. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuroda S, Fukata M, Fujii K, Nakamura T, Izawa I, Kaibuchi K. Regulation of cell-cell adhesion of MDCK cells by Cdc42 and Rac1 small GTPases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:430–435. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuroda S, Fukata M, Kobayashi K, Nakafuku M, Nomura N, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. Identification of IQGAP as a putative target for the small GTPases, Cdc42 and Rac1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23363–23367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuroda S, Fukata M, Nakagawa M, Fujii K, Nakamura T, Ookubo T, Izawa I, Nagase T, Nomura N, Tani H, Shoji I, Matsuura Y, Yonehara S, Kaibuchi K. Role of IQGAP1, a target of the small GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1, in regulation of E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. Science. 1998;281:832–835. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5378.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maeno Y, Moroi S, Nagashima H, Noda T, Shiozaki H, Monden M, Tsukita S, Nagafuchi A. Alpha-catenin-deficient F9 cells differentiate into signet ring cells. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1323–1328. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65385-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller J R, McClay D R. Changes in the pattern of adherens junction-associated β-catenin accompany morphogenesis in the sea urchin embryo. Dev Biol. 1997;192:310–322. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller J R, McClay D R. Characterization of the role of cadherin in regulating cell adhesion during sea urchin development. Dev Biol. 1997;192:323–339. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukherjee S, Soe T T, Maxfield F R. Endocytic sorting of lipid analogues differing solely in the chemistry of their hydrophobic tails. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1271–1284. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagafuchi A, Ishihara S, Tsukita S. The roles of catenins in the cadherin-mediated cell adhesion: functional analysis of E-cadherin-α-catenin fusion molecules. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:235–245. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura T, Nishizawa T, Hagiya M, Seki T, Shimonishi M, Sugimura A, Tashiro K, Shimizu S. Molecular cloning and expression of human hepatocyte growth factor. Nature. 1989;342:440–443. doi: 10.1038/342440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ochiai A, Akimoto S, Shimoyama Y, Nagafuchi A, Tsukita S, Hirohashi S. Frequent loss of alpha catenin expression in scirrhous carcinomas with scattered cell growth. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1994;85:266–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1994.tb02092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozawa M, Kemler R. Altered cell adhesion activity by pervanadate due to the dissociation of alpha-catenin from the E-cadherin catenin complex. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6166–6170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pece S, Chiariello M, Murga C, Gutkind J S. Activation of the protein kinase Akt/PKB by the formation of E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell junctions. Evidence for the association of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with the E-cadherin adhesion complex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19347–19351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potempa S, Ridley A J. Activation of both MAP kinase and phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase by Ras is required for hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor-induced adherens junction disassembly. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2185–2200. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price L S, Leng J, Schwartz M A, Bokoch G M. Activation of Rac and Cdc42 by integrins mediates cell spreading. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1863–1871. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.7.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reif K, Nobes C D, Thomas G, Hall A, Cantrell D A. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signals activate a selective subset of Rac/Rho-dependent effector pathways. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1445–1455. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00749-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren X D, Kiosses W B, Schwartz M A. Regulation of the small GTP-binding protein Rho by cell adhesion and the cytoskeleton. EMBO J. 1999;18:578–585. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sako Y, Nagafuchi A, Tsukita S, Takeichi M, Kusumi A. Cytoplasmic regulation of the movement of E-cadherin on the free cell surface as studied by optical tweezers and single particle tracking: corralling and tethering by the membrane skeleton. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1227–1240. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takaishi K, Sasaki T, Kotani H, Nishioka H, Takai Y. Regulation of cell-cell adhesion by rac and rho small G proteins in MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1047–1059. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takeichi M. Morphogenetic roles of classic cadherins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:619–627. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsukamoto T, Nigam S K. Cell-cell dissociation upon epithelial cell scattering requires a step mediated by the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24579–24584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsukatani Y, Suzuki K, Takahashi K. Loss of density-dependent growth inhibition and dissociation of alpha-catenin from E-cadherin. J Cell Physiol. 1997;173:54–63. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199710)173:1<54::AID-JCP7>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsukita S, Tsukita S, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S. Molecular linkage between cadherins and actin filaments in cell-cell adherens junctions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992;4:834–839. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90108-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasioukhin V, Bauer C, Yin M, Fuchs E. Directed actin polymerization is the driving force for epithelial cell-cell adhesion. Cell. 2000;100:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watabe M, Nagafuchi A, Tsukita S, Takeichi M. Induction of polarized cell-cell association and retardation of growth by activation of the E-cadherin-catenin adhesion system in a dispersed carcinoma line. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:247–256. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.1.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]