Abstract

Hypophysitis is defined as inflammation of the pituitary gland that is primary or secondary to a local or systemic process. Differential diagnosis is broad (including primary tumors, metastases, and lympho-proliferative diseases) and multifaceted. Patients with hypophysitis typically present with headaches, some degree of anterior and/or posterior pituitary dysfunction, and enlargement of pituitary gland and/or stalk, as determined by imaging. Most hypophysitis causes are autoimmune, but other etiologies include inflammation secondary to sellar tumors or cysts, systemic diseases, and infection or drug-induced causes. Novel pathologies such as immunoglobulin G4-related hypophysitis, immunotherapy-induced hypophysitis, and paraneoplastic pituitary-directed autoimmunity are also included in a growing spectrum of this rare pituitary disease. Typical magnetic resonance imaging reveals stalk thickening and homogenous enlargement of the pituitary gland; however, imaging is not always specific. Diagnosis can be challenging, and ultimately, only a pituitary biopsy can confirm hypophysitis type and rule out other etiologies. A presumptive diagnosis can be made often without biopsy. Detailed history and clinical examination are essential, notably for signs of underlying etiology with systemic manifestations. Hormone replacement and, in selected cases, careful observation is advised with imaging follow-up. High-dose glucocorticoids are initiated mainly to help reduce mass effect. A response may be observed in all auto-immune etiologies, as well as in lymphoproliferative diseases, and, as such, should not be used for differential diagnosis. Surgery may be necessary in some cases to relieve mass effect and allow a definite diagnosis. Immunosuppressive therapy and radiation are sometimes also necessary in resistant cases.

Keywords: hypophysitis, lymphocytic hypophysitis, IgG4-related hypophysitis, immunotherapy-induced hypophysitis, paraneoplastic pituitary-directed autoimmunity, stalk biopsy

Hypophysitis is a rare inflammatory disorder that affects the pituitary gland and infundibulum as a result of an autoimmune, infiltrative, infectious, neoplastic, or sometimes unknown pathogenic processes. Over the past decade, substantial diagnostic advances and increased hypophysitis knowledge and characterization have occurred. Novel etiologies, such as immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-related disease, immunotherapy-induced hypophysitis, and paraneoplastic pituitary-directed autoimmunity, have added to a growing hypophysitis disease spectrum. True hypophysitis incidence per year is unknown. Previously reported estimates are 1/9 million individuals (1). Recognition of novel causes, increased use and sophistication of imaging, and increased number of pathology samples postpituitary surgery have led to a hypophysitis disease incidence increase (2,3). Clinical diagnosis can be challenging since many pituitary lesions, including common pituitary adenomas and rare pituitary metastases, may clinically present with similar characteristics.

Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation in conjunction with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and laboratory findings, as well as biopsy results in some cases. In this minireview, we discuss the current approach to diagnosis and management of hypophysitis and address common clinical questions.

A PubMed online database search for all study types published in the English language using the terms “hypophysitis,” “pituitary stalk lesions,” “IgG4-related disease,” “immunotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors,” “neurosarcoidosis,” “Langerhans cell histiocytosis, LCH,” and “pituitary auto-immunity” was performed in June 2021. Articles were screened by title and abstract and restricted to adults. References from selected articles were also reviewed; articles published within the last 5 to 10 years were preferentially reviewed.

Hypophysitis: Classification and Pathogenesis

Hypophysitis is an umbrella term that covers a broad range of inflammatory disorders that affect the pituitary gland. Inflammation can affect only the anterior pituitary (adenohypophysitis), infundibulum and posterior pituitary (infundibulo-neurohypophysitis), or the entire pituitary (panhypophysitis) (1,4). Sometimes this process can extend into the hypothalamus (5) or present as isolated hypothalamitis (6,7).

Etiologically, hypophysitis is characterized as primary or secondary. Primary hypophysitis is an isolated condition and includes autoimmune [eg, lymphocytic hypophysitis (LHy)] and other inflammatory or infiltrative forms of isolated pituitary involvement of unknown causes. Secondary hypophysitis develops as a reaction to a local process (eg, rupture of Rathke’s cleft cyst), systemic disease, infection, and neoplastic processes or drugs (8) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hypophysitis: secondary etiologies, associated diseases, and differential diagnosis

| Etiology | Key clinical features | Laboratory investigation(s) to reach a diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Drug-induced hypophysitis Immune checkpoint inhibitors Interferon alpha Ustekinumab Daclizumab |

Active or recent use of drug within the last 2 years | Clinical diagnosis in the context of current/ recent immunotherapy |

| Autoimmune conditions Thyroid disease Type 1 diabetes mellitus Polyglandular syndrome Primary biliary cirrhosis |

Variable Multisystemic involvement Vitiligo, alopecia Atrophic gastritis Gonadal failure Autoimmune hepatitis |

Investigations specific to each autoimmune disease Anti-TPO |

| Connective tissue diseases Sjogren’s Systemic lupus erythematosus Other |

Multisystemic diseases Arthralgias and synovitis Xerostomia and xerophtalmia Rash, photosensitivity Mucosal ulcers Serositis Renal involvement Cardiac involvement |

CBC (thrombocytopenia, anemia) Urine analysis (proteinuria, hematuria) ANA Anti-Ro, anti-La Anti-SSa Anti-ds-DNA |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Diarrhea with/without blood Abdominal pain Extraintestinal (arthritis, eye, skin, hepatobiliary and others) |

CBC Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein Endoscopy |

| Sarcoidosis | Multisystemic disease causing Respiratory symptoms Malaise, fever, weight loss Hilar adenopathy Cutaneous signs (erythema nodosum, lupus pernio) Eye or cardiac involvement Kidney stones |

CBC Liver enzymes Serum and urinary calcium Serum or CSF ACE levels Chest radiograph CT chest FDG-PET |

| Infiltrative disease Langerhans cell histiocytosis Erdheim-Chester disease |

Multisystemic disease causing Rash, lid xanthelasmas or xanthomas Bone lesions (skull, pelvis, femur) Cardiovascular Lungs Polyadenopathy Hepatosplenomegaly |

Skeletal survey Bone scintigraphy Tissue biopsyCT chest-abdomen-pelvisFDG-PET |

| IgG4-related disease | Pituitary-isolated 4%-5% Multisystemic Retroperitoneal fibrosis Lachrymal and parotid infiltration Polyadenopathy Pancreatitis Affects older aged males |

Elevated IgG4 levels Tissue biopsy CT chest-abdomen-pelvis FDG-PET |

| Vasculitis Temporal arteritis Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener) Other |

Multisystemic disease causing Arthritis Headaches, visual symptoms Vascular lesions affecting Eyes Sinus, lung Skin Kidney Nervous system |

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein Serum creatinine ANCA Urine analysis (proteinuria, hematuria) Chest radiograph Tissue biopsy FDG-PET |

| Infections Tuberculosis Syphilis Bacterial, fungal, viral |

Very rare, in immunosuppressed patients | Leukocytosis or leucopenia PPD skin test or QuantiFERON-TB gold HIV serology Pituitary biopsy: special stains to identify microorganisms PCR for mycobacterium on CSF |

| Paraneoplastic syndromes Anti-Pit-1 Anti-ACTH/POMC |

Thymoma Large cell neuro-endocrine cancer Other neoplasms |

Antibody levels |

| Differential diagnosis | Key clinical features | Laboratory investigation(s) to reach a diagnosis |

| Sellar/para-sellar tumors Craniopharyngiomas Germinomas Astrocytomas Meningioma Other (these can also be secondary causes of hypophysitis) |

Germinomas Young males affected Frequent DI Craniopharyngiomas Intra or supra-sellar cystic lesion Bimodal age distribution < 20 and 50–70 years Frequent DI Meningioma Parasellar mass with dural tail |

Serum AFP and beta-hCG (can be normal in pure cell germinomas) CSF, AFP and beta-hCG Brain imaging Biopsy/surgery |

| Physiological pituitary hypertrophy | Homogeneous gland enlargement Usually absent headache No panhypopituitarism Underlying cause Severe primary gland insufficiency (gonadotroph hyperplasia of menopause, thyrotroph hyperplasia in severe untreated primary hypothyroidism) Somatotroph hyperplasia of adolescence Lactotroph hyperplasia of pregnancy |

Transient upon resolution of the underlying cause |

| Metastases most frequently from Lung Breast Prostate Kidney |

Sellar mass with or without suprasellar extension; rarely pituitary stalk thickening only Headaches, vision changes, CN palsy Anterior hypopituitarism and DI (very frequent) |

FDG-PET Tissue biopsy |

| Pituitary apoplexy | Acute or subacute symptoms of headache Visual deficits/ocular paresis Panhypopituitarism without DI Possible altered mental status Anticoagulation is a risk factor |

Brain CT: acute hemorrhagic infarct Pituitary MRI: lesion characteristics vary Acute: T1 iso- or hyperintense Subacute: T1 and T2 hyperintense Chronic: T1 and T2 hypointense Gadolinium: peripheral rim of enhancement |

| Lymphoproliferative malignancy Plasmacytoma Lymphoma |

Pituitary may be the sole presenting feature Cranial nerves frequently affected Frequent DI In association with multiple myeloma: anemia, bone pain, renal disease, hypercalcemia Extra-pituitary sites of primary pituitary lymphoma: bone marrow, liver, lung, adrenal gland, retroperitoneal lymph node |

CBC LDH Beta2-microglobulin FDG-PET Serum or CSF flow cytometry Oligoclonal bands Tissue/bone marrow biopsy CSF cytology |

| Acute Sheehan syndrome | Acute ischemia leads to enlargement of gland, no contrast uptake Context of severe hypovolemia and hypotension due to severe blood loss at delivery Acute panhypopituitarism, no DI, low prolactin |

Clinical diagnosis in the peripartum context |

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-foetoprotein; beta-hCG, beta-human chorionic gonadotropin; CBC, complete blood count; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CN, cranial nerve; CT, computed tomography; DI, diabetes insipidus; FDG-PET, fluoro-desoxy-glucose positive emission tomography; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; PPD, purified protein derivative skin test for tuberculosis.

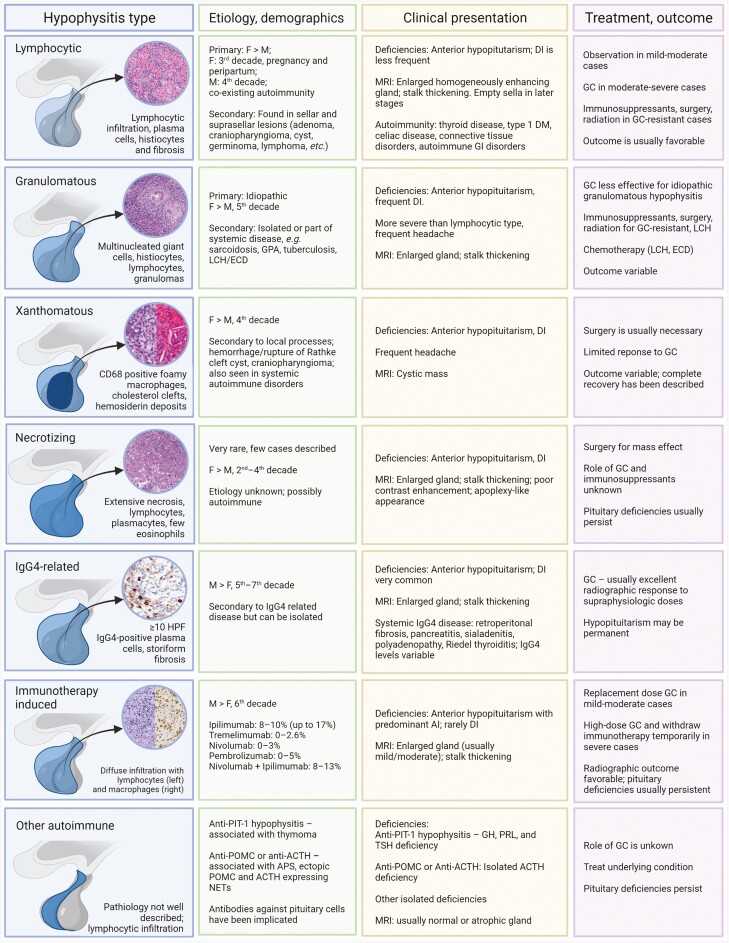

Histological classification includes lymphocytic, granulomatous, xanthomatous (9), IgG-4 related, necrotizing hypophysitis, and mixed forms (lymphogranulomatous, xanthogranulomatous) (4,10); LHy is overall the most common form (11,12). Accurate classification is sometimes not possible due to pathological features overlap (4,10,13-23) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of hypophysitis types, features and treatment options (created with BioRender.com). Histopathology image sources: lymphocytic (author’s [MF] pathology department), granulomatous (17), xanthomatous (9), necrotizing (23), immunoglobulin G4-related (14), and immunotherapy-induced (96). Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotrophic hormone; AI, adrenal insufficiency; APS, autoimmune polyglandular syndrome; DI, diabetes insipidus; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECD, Erdheim-Chester disease; F, female; GC, glucocorticoids; GH, growth hormone; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; HPF, high power field; LCH, Langerhans cell histiocytosis; M, male; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NETs, neuroendocrine tumors; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; PRL, prolactin.

Case 1

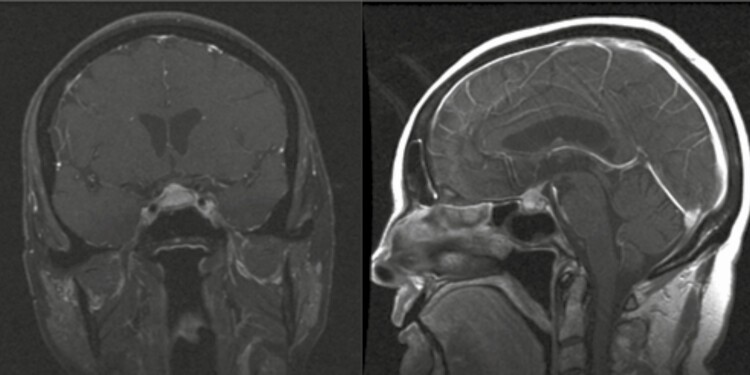

A 73-year-old female with a history of ulcerative colitis (in remission) presents with hyponatremia, weakness, and presyncopal episodes over the past year. She notes decreased vision in her right eye. Laboratory evaluations reveal anterior hypopituitarism without diabetes insipidus (DI). Hyponatremia was present and corrected with hydrocortisone and levothyroxine replacement. A pituitary MRI reveals an enlarged and heterogeneously enhancing pituitary gland, with mild mass effect on the optic chiasm and a slightly thickened pituitary stalk (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Case 1—Granulomatous hypophysitis. Postcontrast T1 pituitary MRI; left, coronal and right, sagittal. Enlarged and heterogeneously enhancing pituitary gland with thickened pituitary stalk and mild mass effect on the optic chiasm.

How Does Hypophysitis Typically Present?

Classically, hypophysitis presents with symptoms related to pituitary deficiencies with or without headaches and vision changes related to the mass effect of an enlarged pituitary gland and infundibulum. Approximately half of patients with primary hypophysitis present with headaches, while 10% to 30% present with visual disturbances related to mass effect (Table 2) (12,24-40).

Table 2.

Summary of primary hypophysitis studies

| Author, year | Patient demographics | Patient MRI findings | Patient clinical symptoms | Patient pituitary dysfunction | Outcome of patients managed medicallya | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient, n | Female, % | Mean age, years | Surveillance management | Glucocorticoid management | ||||

| Angelousi et al (30) | 22 | 77 | 42 36% with autoimmune disease |

45% sellar mass 35% stalk thickening 23% diffuse enlargement |

59% headache 32% diplopia |

36% HyperPRL 32% LH-FSH 32% DI 23% ACTH 14% TSH |

5/22 Improvement: 20% hormonal |

8/22 Prednisone 40-60 mg Improvement: 75% hormonal at 5 years 37% radiological |

| Amereller et al (24) | 60 | 73 | 45 42% with autoimmune disease |

56% stalk thickening 46% sellar mass 37% diffuse enlargement |

38% headache 17% visual impairment |

67% ACTH 57% TSH 52% LH-FSH 38% DI |

41/60 Improvement: 27%hormonal 10% radiological |

12/60 GC 30 mg-2 g pulse Improvement: 17% hormonal 25% radiological |

| Atkins et al (35) | 11 | 91 | 41 | 73% stalk thickening 55% sellar mass 36% diffuse enlargement |

55% headache | 36% ACTH 36% TSH 36% DI 27% HyperPRL 18% LH-FSH |

6/11 Improvement: 17% hormonal 50% radiological |

2/11 GC dose unknown Improvement: 0% hormonal 100% radiological |

| Chiloiro et al (36) | 21 | 81 | 40 81% with autoimmune disease |

57% stalk thickening | 24% headache 19% visual impairment |

48% DI 43% LH-FSH 43% HyperPRL 33% ACTH 14% TSH |

21/21 GC dose unknown Improvement: 86% hormonal 62% radiological |

|

| Honegger et al (26) | 79 | 71 | 41 | 86% stalk thickening | 50% headache 22% visual impairment |

62% LH-FSH 54% DI 48% TSH 47% ACTH 36% HyperPRL |

22/79 Improvement: 27% hormonal 45% radiological |

29/79 GC 20-500 mg Improvement: 14% hormonal 57% radiological 38% recurrence |

| Imber et al (33) | 21 | 62 | 37 | 68% diffuse enlargement 63% stalk thickening |

57% headache 52% visual impairment |

71% LH-FSH 57% ACTH 57% TSH 52% DI 48% HyperPRL |

15/21 (4 GC, 11 surveillance) Improvement: 27% hormonal 47% radiological |

15/21 (4 GC, 11 surveillance) Improvement: 27% hormonal 47% radiological |

| Imga et al (12) | 12 | 75 | 44 | 58% stalk thickening 33% diffuse enlargement |

67% headache 33% visual impairment |

75% TSH 75% LH-FSH 58% ACTH 17% DI 8% HyperPRL |

4/12 GC 1g pulse + surgery Improvement: 25% hormonal 100% radiological |

|

| Khare et al (32) | 24 | 88 | 32 | 92% diffuse enlargement 88% stalk thickening |

83% headache 13% diplopia |

75% ACTH 58% TSH 50% LH-FSH 17% DI |

15/24 Improvement: 33% hormonal 100% radiological |

4/24 GC 1g pulse Improvement: 100% hormonal 100% radiological |

| Korkmaz et al (39) | 17 | 59 | 31 6%with autoimmune disease |

47% sellar mass 41% stalk thickening 18% diffuse enlargement |

53% headache 12% visual impairment |

59% ACTH 53% TSH 47% LH-FSH 47% DI 41% HyperPRL |

10/17 Improvement: 10% hormonal 30% radiological |

5/17 GC 120mg, rescue Improvement: 20% hormonal 40% radiological |

| Krishnappa et al (40) | 39 | 82 | 39 | 85% diffuse enlargement | 64% ACTH 56% TSH 54% LH-FSH 18% DI |

21/39 Improvement: 43% hormonal 48% radiological |

18/39 GC 1g pulse Improvement: 85% hormonal 61% radiological |

|

| Kyriacou et al (38) | 22 | 86 | 38 | 64% sellar mass | 68% headache 32% visual impairment |

86% ACTH 59% TSH 41% LH-FSH 32% DI 23% HyperPRL |

13/22 Improvement: 0% hormonal |

3/22 Postoperative, GC dose unknown Improvement: 0% hormonal |

| Lupi et al (34) | 12 | 67 | 47 | 66% stalk thickening 33% diffuse enlargement |

33% headache | 83% DI 50% LH-FSH 42% TSH 33% ACTH |

4/12 Improvement: 0% hormonal 100% radiological |

8/12 GC 40 mg Improvement: 37% hormonal 100% radiological |

| Park et al (31) | 22 | 77 | 47 | 77% stalk thickening 59% diffuse enlargement |

27% headache 9% visual impairment |

82% DI 36% ACTH 36% TSH 32% LH-FSH 23% HyperPRL |

12/22 Improvement: 17% hormonal 0% radiological |

7/22 GC 50-500 mg Improvement: • 14% hormonal • 71% radiological |

| Oguz et al (27) | 20 | 75 | 41.5 | 24% diffuse enlargement 18% stalk thickening |

63% headache 37% visual impairment |

66% LH-FSH 61% TSH 39% ACTH 32% HyperPRL 28% DI |

1/20 surveillance Improvement: No radiological No hypopituitarism |

4/20 GC 60 mg-1 g pulse Improvement: 25% hormonal 100% radiological |

| Wang et al (25) | 50 | 66 | 37 | 96% stalk thickening 88% diffuse enlargement 78% sellar mass |

48% headache 40% visual impairment |

72% DI 60% LH-FSH 48% HyperPRL 38% TSH 26% ACTH |

9/50 Improvement: 22% DI only 22% radiological 11% recurrence |

26/50 GC 30-60 mg Improvement: 41% hormonal 100% imaging 46% recurrence |

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotrophic hormone (central adrenal insufficiency); DI, diabetes insipidus; GC, glucocorticoids; hyperPRL, hyperprolactinemia; Ig, immunoglobin; LH-FSH, luteinizing hormone-follicle stimulating hormone; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

aData are given as patients/total patients.

Symptoms related to loss of anterior and/or posterior pituitary hormones depend on etiology and extent of pituitary damage. Generally, the presence of both anterior pituitary dysfunction and DI is a clue to an inflammatory/infiltrative process, craniopharyngiomas, or metastasis and is highly unlikely in pituitary adenomas. In LHy and immunotherapy-induced hypophysitis, inflammatory process predominantly affects corticotrophs, followed by gonadotrophs and thyrotrophs (24). Importantly, this pattern is distinct from that of pituitary adenomas, where corticotrophs are usually affected last (4,41).

All patients require initial pituitary function testing: 8 am cortisol [and/or adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) stimulation test]; thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH); free thyroxine; prolactin; luteinizing hormone (LH); follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) with estradiol in premenopausal women or testosterone in men; insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1); and serum sodium, plasma, and urine osmolarity if DI is suspected (4,42). Hyponatremia may be observed in adrenal insufficiency (AI), severe hypothyroidism, and syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone, and hypernatremia may be observed in uncompensated DI cases. Depending on etiology and clinical context, each unique hypophysitis type may have specific systemic features related to the underlying cause (Table 1).

What Are the Radiological Features of Hypophysitis?

Hypophysitis harbors various imaging characteristics. The most frequent MRI finding is a thickened, nondeviated stalk, which can be isolated (infundibulo-neurohypophysitis) in one third of patients or associated with mild to moderate symmetric gland enlargement in >80% of patients (39,43). Contrast uptake is usually intense, homogeneous, and less frequently heterogeneous (43). An enlarged pituitary resembles a pituitary macroadenoma in approximately half of patients with primary hypophysitis (24,30,44). While the sellar floor may be eroded in pituitary adenomas, it is usually intact in hypophysitis (45). Other signs of hypophysitis include loss of posterior pituitary bright spot, caused by depletion in vasopressin granules in posterior pituitary hypophysitis (39,46). Dural inflammation may cause a dural tail sign, similar to that observed in patients with a meningioma (10). In late disease stages, the pituitary gland may appear atrophic, and MRI may show sellar arachnoidocele or an empty sella (47,48). Although there are no definite MRI features that can confirm hypophysitis, imaging can be diagnostic in the right clinical context; for example, stalk thickening in a young woman with recent pregnancy presenting with headache and hypopituitarism is highly suggestive of LHy (49). Specific radiologic findings in different types of hypophysitis are presented in Figure 1.

Case 1 Continued

The patient undergoes pituitary surgery for this mass with optic chiasm compression. Pathology reveals necrotizing granulomas with giant cells and rich lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. Staining for microorganisms (Steiner for acid-fast bacilli and fungi; Grocott methenamine-silver nitrate for Pneumocystis jirovecii) are negative. There is no evidence of sarcoidosis; angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level is normal; and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antinuclear antibody, and thyroid peroxidase antibody are negative.

Is a Biopsy Always Necessary to Confirm a Hypophysitis Diagnosis?

Biopsy establishes hypophysitis histopathological type and rules out other etiologies such as neoplasm. However, this is an invasive procedure, and risks and benefits must be carefully weighed. Biopsy is usually considered either when a diagnosis is unclear after initial investigations or when pathology results are needed for treatment (eg, long-term glucocorticoids, immunosuppression, or chemotherapy) (33). There are no established criteria for pituitary biopsy in adults. In the pediatric population, a recent UK consensus proposes biopsy in cases of unclear diagnosis after extensive laboratory, imaging, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) investigations, when stalk thickening is ≥6.5mm or when there is clinical deterioration, defined as worsening of hormonal dysfunction, structural disease, or visual disturbances (50). If a biopsy is contemplated, it should be performed by an experienced neurosurgeon in a specialized center (51).

Overall, there 5 hypophysitis histological subtypes described in Figure 1 (4,13-23).

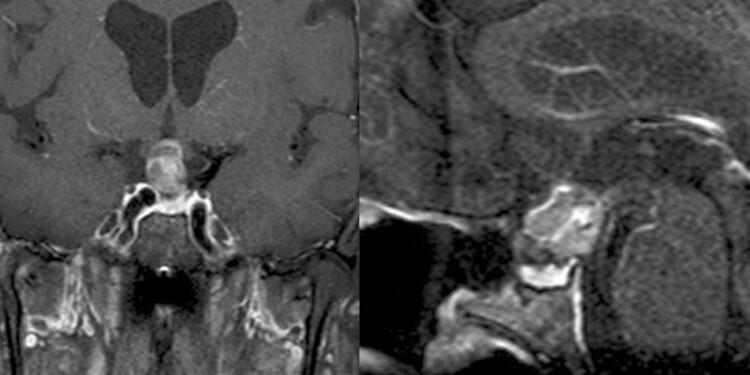

Case 2

A 71-year-old male presents with headaches, anterior hypopituitarism, and DI. Pituitary MRI shows heterogeneous suprasellar stalk lesion with cystic change of approximately 1 cm (Fig. 3), and biopsy reveals polyclonal lymphocytic infiltration (CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells) with CD68+ macrophages, leading to a presumed LHy diagnosis. The patient declines high-dose glucocorticoid (GC) treatment and is lost to follow-up. Over the following 3 years, headaches worsen, and the lesion has enlarged to 2 cm. The patient undergoes pituitary surgery. Pathology reveals a papillary craniopharyngioma; WHO grade I, with extensive reactive xanthogranulomatous changes including abundant macrophages and numerous giant cells and cholesterol clefts. The patient continues to be panhypopituitary; headaches have completely resolved. There is no evidence of residual disease at last postoperative follow-up (3 years).

Figure 3.

Case 2—Xanthogranulomatous inflammation associated with craniopharyngioma. Postcontrast T1 pituitary magnetic resonance imaging; left, coronal and right, sagittal. Progressive partially cystic suprasellar lesion, 14 × 13 × 18 mm with mass effect on the optic chiasm.

This rare case demonstrates a spectrum of inflammatory pituitary changes that can occur secondary to other sellar tumors and highlights the need for repeat imaging and further workup if clinical course is atypical for presumed LHy.

What Other Workup Can Be Performed to Elucidate a Hypophysitis Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis?

Pituitary biopsy may be the only modality that allows for a definitive diagnosis. However, a minority of patients will undergo a surgical procedure, as careful clinical evaluation may orient toward a probable diagnosis (52).

Demographic information is important to guide investigations. For instance, stalk thickening in a young female is suggestive of LHy, while in a child or adolescent, it should prompt investigations for germinoma; in older aged adults, other malignancies such as lymphoma should be considered (52).

A baseline workup includes a complete blood count, sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, calcium, creatinine, urinalysis, and ALT. Specific investigation are further tailored to clinical features: IgG4, ACE, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antinuclear antibody, lactate dehydrogenase, B2-microglobulin, alpha-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin, tuberculin skin test, or QuantiFERON-TB Gold. Key clinical features of systemic disease associated with hypophysitis and laboratory investigations to be considered are listed in Table 1. Serum antipituitary antibodies may be present; however, they lack specificity as they are commonly present in patients with different autoimmune disorders without pituitary involvement as well as in pituitary adenomas (53-55). Therefore, their measurement is of little clinical use currently. Recently, pituitary-specific positive transcription factor 1 (Pit-1) has been described as an antigen target in LHy, but antibody assays are not widely available (56).

Whole-body computed tomography or fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) could determine other affected sites in systemic diseases including sarcoidosis, tuberculosis (TB), granulomatosis with polyangiitis, malignancy, and IgG4-related disease, including other accessible locations for potential tissue biopsy; FDG-PET may reveal multisystemic hyperfunctional lesions (31,57). Whole-body imaging is recommended in patients with isolated stalk lesions and no LHy clinical context or when malignancy or infiltrative disease is highly suspected.

CSF analysis for cytology, flow cytometry, immunochemistry (including ACE, human chorionic gonadotropin, and alpha-fetoprotein) and culture can be also helpful if initial investigations are negative and neoplastic process or infection are suspected (25,52), as well as in evolving disease determined by either progressive hormonal dysfunction, increasing size of pituitary/stalk lesion, and/or visual deterioration (50).

If all these investigations are negative, a trial of empiric high-dose GC could be considered as most of the infiltrative and inflammatory conditions will have similar treatment (high-dose GC and/or immunosuppression). However, biopsy should be reconsidered in patients with unfavorable clinical course as biopsy-confirmed diagnosis would allow the selection of appropriate therapy and avoid delays in treatment of other diseases, especially hematologic or solid malignancies.

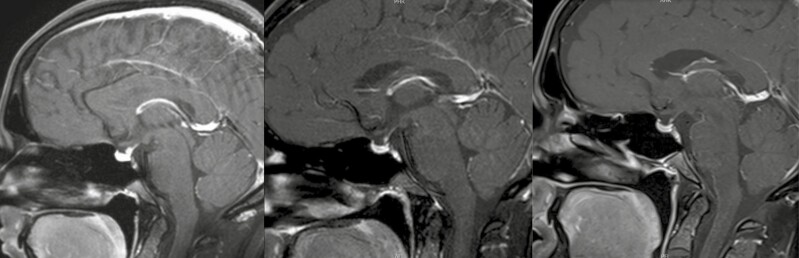

Case 3

A 30-year-old female presents with polydipsia and polyuria, and laboratory findings are consistent with DI. The patient is otherwise healthy, with a history of lichen sclerosis. Pituitary MRI reveals 5-mm stalk enlargement (Fig. 4). Anterior pituitary function is intact. The patient is treated with desmopressin and observed with serial MRIs, which show stability over a period of 3 years. The patient experiences an uneventful spontaneous pregnancy and delivery; pituitary MRI 2 years after delivery shows regression of thickened stalk. A near complete resolution of the stalk thickening is observed on MRI 12 years after delivery. Diabetes insipidus persists, and the patient continues to take desmopressin. This patient has never had a pituitary biopsy or treatment with high-dose GC, but probable diagnosis is LHy.

Figure 4.

Case 3—Lymphocytic hypophysitis with isolated infundibulo-neurohypophyisitis. Postcontrast T1 pituitary magnetic resonance imaging sagittal; left, baseline, stalk thickening measuring 5 mm in diameter, otherwise normal-size pituitary gland; middle, 5 years after initial presentation, spontaneous regression of stalk thickening, now approximately 2 mm in diameter; and right, 12 years after initial presentation, complete resolution of stalk thickening.

How Should Hypophysitis Be Treated?

Treatment should be geared toward the underlying disease etiology and severity.

GCs have been considered the mainstay of treatment for primary hypophysitis as GCs target the inflammatory process; however, spontaneous resolution of pituitary infiltration with/without permanent pituitary dysfunction can occur frequently. In a German cohort, 46% of patients with primary hypophysitis managed by observation only showed radiological improvement, and one third had hormonal recovery, mainly vasopressin and ACTH (37). In the chronic phase, when irreversible changes have occurred, anti-inflammatory treatment may not affect radiologic or hormonal outcome (58).

As no randomized controlled studies have been performed, it is unclear whether GC allows for better pituitary function recovery vs simple observation. Given a broad spectrum of GC side effects, risks and benefits should be weighed when deciding whether to treat mild cases of primary hypophysitis.

Clinical signs and symptoms should guide a decision to manage patients solely by observation. In patients with mild to moderate headache, mild pituitary dysfunction, no mass effect on optic chiasm, and probable LHy, observation may be safely considered (24,37). Initial clinical surveillance can be performed with pituitary MRI at 3 to 6 months. This imaging interval can be prolonged if disease evolution is favorable. However, if lesions are causing a significant mass effect at baseline or follow-up, either GC treatment, biopsy, or both should be performed (6). During observation, periodic reevaluation for pituitary function recovery is needed. Additionally, clinicians should be alert for new symptoms affecting other organs as systemic disorders such as sarcoidosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), and IgG4-related disease may manifest later in the course of disease (59,60).

Primary hypophysitis has very variable GC response rate, from 20% to >95% in a partial or complete hormonal and radiographic response (12,24-40). Overall improvement in endocrine function occurs less than reduction in pituitary mass, which can attain closer to a 75% response rate (11,12,24-40) (Table 2). Earlier GC initiation has been shown to improve hormonal recovery (40). Interestingly, some retrospective studies have revealed better pituitary function outcomes with observation vs GC administration; however, milder and potentially reversible cases were probably less likely to be treated with GC (24,35,37).

Studied prednisone doses for treatment of primary hypophysitis range widely, between 20 mg/day initial dose to 1 g methylprednisone pulse therapy. Due to the rarity of this condition and a lack of large randomized prospective clinical trials, the exact dose, duration, and even indication for GC is still a matter of debate. Some authors advocate use of pulse regimens of high-dose methylprednisolone (120 mg-1 g) intravenously (40,61). In a series of 39 patients, intravenous pulse followed by high-dose prednisone resulted in a 2-fold hormonal recovery rate compared to patients with observation (86% vs 43%, P = 0.0007) (40). Lower GC doses may also be effective. A prospective study compared 12 patients treated by 50 mg prednisone for 3 months with a slow taper to 8 patients managed by observation. At the end of a 2-year follow-up, more prednisone-treated patients (58.3%) compared to untreated patients (25%) improved their pituitary function, and 66% of treated vs 25% of untreated had radiographic improvement (46).

Studies comparing pulse or higher-dose vs lower-dose GC regimen are lacking. A 1 mg/kg/day dosing with slow taper may be preferred to GC pulse therapy to reduce risk of recurrence (34,46). However, recurrence can develop even during the steroid taper (37). In a series of 76 patients with primary hypophysitis, almost half (32/76) received GC treatment at some stage with a good initial response in almost all cases, but relapse and treatment failure occurred in 40% (37). No correlation was observed between duration of therapy and initial dose.

Immunosuppression with rituximab, azathioprine, or methotrexate may be considered in GC-refractory cases and as GC-sparing options. Azathioprine is the most studied and appears superior for mass reduction than hormonal improvement (10,11). Similar results have been observed with methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil (10). Rituximab, an anti-CD20+, can be used in B-lymphocytes predominant diseases and relapsing IgG4-related disease (62,63); complete remission is possible (64,65).

Surgery may be used not only for decompression of optic chiasm and GC-resistant cases but also to confirm diagnosis in cases where diagnosis needs clarification. In a large series of 60 patients with primary hypophysitis, patients who underwent surgery had a worse outcome, based on symptoms and endocrine dysfunction (24). However, it is likely that patients who had surgery had more severe baseline disease.

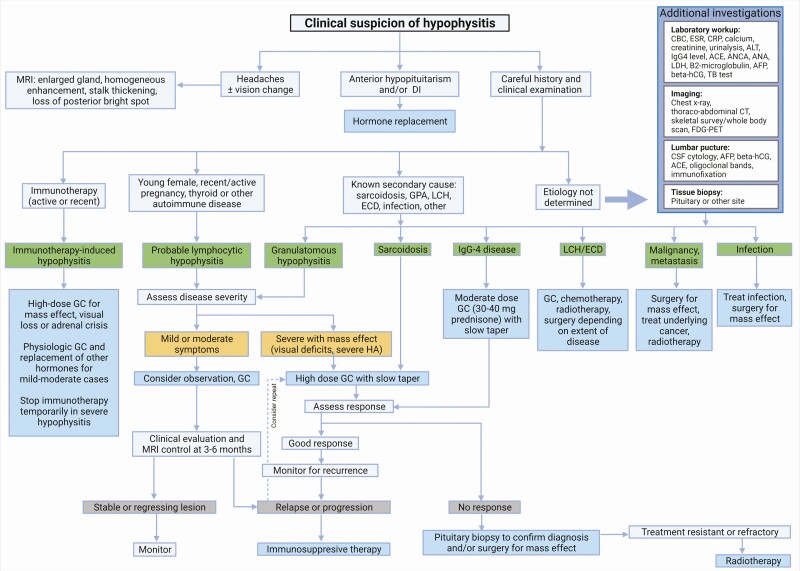

Fractionated radiotherapy and stereotactic radiosurgery have been used successfully in a few patients requiring multimodal therapy (10,37). For treatment-resistant and recurrent LHy, radiosurgery is an option to allow mass control and discontinuation of immunosuppression (66,67). Treatment of other specific types of hypophysitis is addressed in the following discussion. A suggested hypophysitis treatment management algorithm is outlined in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Hypophysitis treatment management algorithm (created with BioRender.com). Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ANA, antinuclear antibody; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; beta-hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; CBC, complete blood count; CRP, C-reactive protein; CT, computed tomography; DI, diabetes insipidus; ECD, Erdheim-Chester disease; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FDG-PET, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography; GC, glucocorticoids; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; LCH, Langerhans cell histiocytosis; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TB, tuberculosis.

Specific Hypophysitis Types

Lymphocytic Hypophysitis

Lymphocytic hypophysitis comprises approximately two thirds of cases of primary hypophysitis forms and occurs more commonly in females (2-4:1 female:male ratio); children and elderly may also be affected (4,25,30). In women, LHy occurs peripartum in more than half, either in late pregnancy or early postpartum with a peak occurrence during the third trimester (58). Interestingly, a few reports have shown a much weaker association of LHy with pregnancy; in one study, 11% of women had a recent pregnancy history, and in another study, 1/21 (5%) (26,32). Association with a personal or familial history of autoimmune disease (such as autoimmune thyroid disease, lupus, primary biliary cirrhosis, celiac disease, among others) is frequent, and specific human leukocyte antigen DQ8 and DR3 alleles are predisposing (41).

Lymphocytic hypophysitis appears to be a T cell–mediated event. In a murine model of hypophysitis, T cells activation rather than autoantibody/B cell infiltration is demonstrated. CD4+ T cells predominate and harbor a specific phenotype with T helper 17 and 1 cells, respectively, producing interleukin 17 and interferon-gamma (68,69).

Treatment of LHy is described in the previous discussion as treatment of primary hypophysitis. In cases of severe headache and significant mass effect, high-dose GCs are first-line treatment. Response to systemic GC treatment is usually good in LHy but notably less than in IgG4-related disease (70). Of note, secondary masslike inflammation due to a local or systemic process might also respond, especially in patients with a central nervous system lymphoma (71); thus, GC response does not confirm a presumptive diagnosis of LHy (40).

Granulomatous Hypophysitis

Granulomatous hypophysitis comprises approximately 20% of primary hypophysitis cases; similar to LHy, has a female predominance (2.5:1); and can be associated with autoimmune disorders (4,26). It usually manifests in the fourth decade of life.

Clinical presentation may be indistinguishable from LHy; however, several series have shown more severity, with more frequent headaches, higher rates of anterior hypopituitarism, DI (up to 75%), and degree of radiographic abnormality (26). Moreover, granulomatous hypophysitis is usually less GC-responsive compared to LHy (10,58).

Granulomatous forms of hypophysitis related to systemic disorders may not always manifest with multisystem involvement.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic autoimmune disorder with formation of noncaseating granulomas. Pituitary involvement occurs in <1 % of sarcoidosis cases. Sinonasal granulomas may be contiguous with the sella (59). Cranial nerves, as well as basal hypothalamus and the third ventricle floor, may be affected by the process (8,59). Interestingly, hypophysitis may be its only presenting feature. In a series of hypothalamo-pituitary sarcoidosis, only 11/24 (46%) patients had a previous diagnosis of sarcoidosis (59). However, patients with pituitary involvement had higher risk of developing systemic disease, with 71% lung, 58% neurologic, 38% sinus, and 33% with ocular involvement (59). Only one third of patients had an elevated serum ACE vs 71% controls without pituitary involvement (59). Elevated enzyme in CSF is found in approximately 50% of cases (72). Hypogonadism was the most frequent axis affected, and DI was present in half of cases. Sarcoidosis is evoked if a certain percentage of granulomas are found at biopsy (13,59,73). Pituitary MRI changes include a hypothalamic-pituitary or stalk thickening in almost all cases, which regress upon GC treatment. However, hormonal abnormalities persist long term (59).

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis hypophysitis is rare (< 1%) and is usually found in association with multisystem disease (ear, nose, and throat disease and lung, as well as kidney, skin, eyes, and arthralgias) (74,75). However, pituitary involvement as an initial presentation was noted in almost half of cases (75). There is a predilection in young females, and DI is almost universally present (74,75). First-line treatment is GCs; other treatment options include immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide (74,75).

Pituitary tuberculoma, is a rare presentation of TB. Interestingly, primary pituitary involvement can occur without multisystemic involvement. Most cases reported are in patients originating from endemic regions (76). Typical clinical presentation is an afebrile patient with headaches, visual impairment, and hypopituitarism with DI (76). Histology shows caseating and necrotizing granulomas. Acid-fast bacilli and Zielh-Neeslen stains are usually negative in pituitary TB, but polymerase chain reaction for mycobacterium on CSF can confirm diagnosis (76,77). In a German series, 3/7 cases of hypophysitis with granulomatous inflammation on biopsy were diagnosed with TB; none were diagnosed with miliary disease (12). Pituitary TB is treated with a combination of antituberculous medications (76).

Histiocytosis

Histiocytosis is a spectrum of disease originating from abnormal Langerhans cells (dendritic or antigen-presenting cells) and includes LCH and Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD). Hypothalamic-pituitary involvement is more frequent in LCH than ECD (78). In both conditions, infiltration preferentially affects neurohypophysis, with DI the most common presenting feature, sometimes even predating the diagnosis. Notably, LCH is most often encountered in children but can also occur during adulthood. Systemic manifestations in LCH and ECD mainly affect dermatological and skeletal systems. In LCH adults, 50% of patients will show lytic bony lesions (with skull, pelvis, and femur most affected), but most are asymptomatic (60,79-82). In ECD, bone involvement usually presents as osteosclerotic painful lesions affecting the lower limbs (80,81). Skin manifestations may present as a rash (LCH) or lid xanthelasmas or xanthomas (ECD). Other system involvement may include cardiovascular, respiratory, polyadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly (81,82).

Hypothalamic-pituitary infiltration occurs more commonly in those with systemic involvement. Pituitary biopsy will demonstrate granulomatous involvement of monoclonal Langerhans cells (CD1a+ and CD207+) along with polyclonal inflammatory cells, notably T lymphocytes, macrophages, and eosinophils (79). In ECD, histiocytes are CD68+ and CD1a− (80,81).

DI and growth hormone abnormalities are the most common (15%-50%) followed by hypogonadism (34%), ACTH (15%-21%), and TSH (16%-23%) deficiencies (83). Some may present with hypothalamic dysfunction including hyperphagia, adipsia, impaired thermoregulation, and sleep, memory, and behavioral disturbances (8,83). Treatment modalities include surgery, GCs, immunosuppressive agents, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and targeted agents (BRAF inhibitors, MEK inhibitors) (82).

IgG4-related Hypophysitis

IgG4-related hypophysitis is a plasma cell hypophysitis that may present either as an isolated pituitary lesion (sometimes classified as primary hypophysitis) or a multisystemic disease. It is characterized by a dense infiltration of lymphocytes and IgG4-positive plasmacytes, leading to fibrosis with characteristic cartwheel pattern in the advanced stages. IgG4-related disease may affect a wide range of organs, thus leading to a spectrum of clinical manifestation, the most frequent being retroperitoneal fibrosis, sclerosing sialadenitis, adenopathy, and pancreatitis but may also include lung interstitial infiltration, pericardial and vascular fibrosis, nephritis, or Riedel thyroiditis (84,85).

IgG4 hypophysitis is now increasingly recognized; in 2 reviews comprising 52 idiopathic hypophysitis cases, 30% to 40% were confirmed a posteriori with IgG4-related disease (2,16). Mean age at diagnosis is 55 to 65 years old, males being more frequently affected with multisystemic disease (84-86). Pituitary involvement in IgG4-related disease affects 4% to 5% of patients (87,88) and could be the sole presenting feature in 10% to 30% of those, mostly in women (84-86). The vast majority will thus have multiorgan involvement, and investigations including whole-body imaging is advised (70). FDG-PET scanning may reveal multisystemic hyperfunctional lesions (31,57).

Diagnosis is established based on the previously described histologic criteria or on compatible MRI findings combined with (1) other tissue biopsy proven disease or (2) elevated IgG4 levels >140 mg/dL and a good response to GC treatment (15).

Combined anterior hormone deficiency with DI is observed in 20% to 40% of cases (84-86). In more than half of patients both pituitary and stalk are enlarged on imaging (84). Notably, 15% to 25% of patients will have normal IgG4 serum levels, mostly women (84-86). Response to supraphysiological GC doses is universal and prevents fibrosis (84); prednisone, 30 to 40 mg per day, is usually given for 1 to 2 months and then tapered over 2 to 6 months (70). Relapses are infrequent, and rituximab might be a good alternative in these cases (85,89).

Immunotherapy-related Hypophysitis

Immunotherapy to increase host response to recognize tumor cells revolutionized oncology treatment. These molecules inhibit the self-tolerance and tumoral immune escape allowing T-cell activation, ultimately allowing an enhanced host immunologic response toward cancer cells. The main molecular targets are the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte protein 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), the first 2 located on T cells, and the latter on the antigen-presenting and tumor cells. CTLA-4 inhibitors (CTLA-4i; eg, ipilimumab, tremelimumab) act earlier in the immune response while PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors (PD-1/PD-L1i; eg, nivolumab and pembrolizumab) act more peripherally at the tumor level (3).

In parallel, immune-related events occur as side effects and can affect multiple organs and system including the pituitary gland. Mechanisms include autoantibodies directed to the pituitary and complement activation (type 2 hypersensitivity reaction) with CTLA-4i. Indeed, CTLA-4 is also expressed by pituitary cells, thus making it a direct target for these drugs (90,91). In a series of 8 patients who developed immunotherapy-related hypophysitis, 2 autoantibodies were significantly associated with hypophysitis. One targets integral membrane protein 2B, a protein implicated in ACTH stimulation and release, and the second targets guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(olf) subunit alpha, implicated in hormone synthesis, notably TSH (92).

Not all immunotherapy drugs have the same effect on the pituitary gland. A comprehensive cohort analysis on checkpoint inhibitors showed a different profile of PD-1/PD-L1i compared to CTLA-4i: lower incidence (1%-2%), milder course, development later during treatment, isolated AI, less headaches, and rare MRI changes (3,93,94). However, combined anti-CTLA and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies lead to an increased occurrence and earlier disease (95). ACTH is the most frequent deficit in all checkpoint inhibitors, usually isolated in PD-1/PD-L1i, and may be associated with TSH and LH/FSH deficits in CTLA-4i–treated patients. Very rarely hyperprolactinemia or DI will occur (96). Notably, DI is atypical and may suggest a pituitary metastasis.

The role of imaging in diagnosis is less clear in these patients and is mostly used to exclude other causes of hypopituitarism. Pituitary MRI changes can be either subtle or even absent with anti-PD-1 and PD-L1 (97), although MRI may reveal pituitary gland hypertrophy with CTLA-4i. Conversely, changes on MRI can precede hypopituitarism development (3). Thus, in patients undergoing brain imaging surveillance for their primary/metastatic cancer, close attention to the pituitary gland is needed.

Risk factors for immunotherapy-induced hypophysitis include male sex, older age, and possibly higher doses of the culprit drug (3). However, there are no specific predictors; clinical assessment and regular adrenal and thyroid monitoring should be planned at least monthly during the first 6 months and extended thereafter as needed (98). Cortisol axis evaluation can be challenging in patients who have received high-dose GCs and/or have dysalbuminemia and/or acute illness (99). An ACTH stimulation test might be falsely normal if the event is acute. As primary AI has also been described (much rarer), obtaining ACTH levels is important (100). Patients should be educated about symptoms of AI, although fatigue, appetite loss, and nausea are nonspecific, especially in an oncology context. Awareness is advised throughout and after treatment as some delayed events have been described, occurring up to 6 to 15 months after immunotherapy cessation (101).

Physiologic hormone replacement with hydrocortisone and/or thyroxine is recommended. Delaying immunotherapy might be reasonable in the acute setting until patient is stabilized but discontinuation does not seem to improve pituitary outcome and may lead to cancer progression (102-105). High-dose GCs should be restricted to patients with severe symptoms of mass effect, visual loss, or adrenal crisis. In patients with melanoma, use of high-dose GCs has not been shown to improve pituitary recovery. Furthermore, 1 study showed that patients with ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis who received higher GC doses had reduced survival (106). However, experiencing an immune-related event seems to confer a better overall survival compared to patients without such event (107). The adrenal axis rarely recovers in these patients, but gonadal and thyroid may, and they should be reassessed periodically.

Paraneoplastic Pituitary Autoimmunity

Recent advances in the understanding of pituitary autoimmunity have led to the description of a novel clinical entity: paraneoplastic pituitary autoimmunity. Tumors that express Pit-1 or proopiomelanocortin/ACTH may lead to production of anti-Pit-1 and anti-ACTH antibodies (41,108). Pit-1 is a transcription factor implicated in the differentiation of anterior pituitary cells, namely somatotrophs, lactotrophs, and thyrotrophs. Anti-Pit-1 syndrome thus leads to a combined deficit in growth hormone, prolactin, and TSH. Similarly, other tumors may trigger anti-ACTH antibodies production that lead to immune destruction of corticotrophs and subsequent AI. Interestingly, Pit-1 hypophysitis has been observed mostly in patients with thymomas and other malignancies such as lymphoma (109,110) and isolated ACTH deficiency in gastric cancer, lymphoma, and ACTH-expressing large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (41,108-111). Histology is not well described; however, autopsy pituitary lymphocytic infiltration was found in a patient with an ACTH-expressing large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (111). Clinical presentation is a hormonal deficiency, without headache, and may precede a diagnosis of underlying cancer for a few years (110,111). Imaging is often unremarkable or reveals mild pituitary atrophy or heterogeneous gland enhancement (110). Hypopituitarism is irreversible, and treatment relies on management of the underlying cancer and hormonal replacement (110).

Conclusion

In conclusion, in the last few years there has been a rich and innovative expansion of knowledge related to the pathophysiology of novel types of hypophysitis, including immunotherapy-induced, IgG-4-related disease, and paraneoplastic pituitary autoimmunity. Pituitary inflammation can present either as an isolated autoimmune event or can be secondary to various multisystemic conditions. With increasing incidence of hypophysitis, heightened clinical awareness is advised. While many pituitary lesions may mimic hypophysitis, a thorough history and clinical examination combined with biochemical, pituitary imaging, and, in selected cases, histological findings often allow the establishment of a correct diagnosis. In addition to hormonal replacement, high-dose GCs may be indicated in some patients; while mass effect will likely improve, pituitary function rarely returns to normal. Further studies on the characterization of the various hypophysitis facets will allow for a more accurate diagnosis and individualized patient treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shirley McCartney, PhD (Oregon Health & Science University) for editorial assistance, and Matthew Wood, MD (Oregon Health & Science University), for lymphocytic hypophysitis histopathology image.

Funding: No funding has been received for this work.

Additional Information

Disclosures: The authors have no conflict related to this topic.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Caturegli P, Newschaffer C, Olivi A, Pomper MG, Burger PC, Rose NR. Autoimmune hypophysitis. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(5):599-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bando H, Iguchi G, Fukuoka H, et al. The prevalence of IgG4-related hypophysitis in 170 consecutive patients with hypopituitarism and/or central diabetes insipidus and review of the literature. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170(2):161-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Faje A. Immunotherapy and hypophysitis: clinical presentation, treatment, and biologic insights. Pituitary. 2016;19(1):82-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gubbi S, Hannah-Shmouni F, Verbalis JG, Koch CA. Hypophysitis: an update on the novel forms, diagnosis and management of disorders of pituitary inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;33(6):101371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Türe U, De Bellis A, Harput MV, et al. Hypothalamitis: a novel autoimmune endocrine disease. a literature review and case report. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;106(2): e415-e429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gubbi S, Hannah-Shmouni F, Stratakis CA, Koch CA. Primary hypophysitis and other autoimmune disorders of the sellar and suprasellar regions. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2018;19(4):335-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wei Q, Yang G, Lue Z, et al. Clinical aspects of autoimmune hypothalamitis, a variant of autoimmune hypophysitis: experience from one center. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(3):300060519887832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fleseriu M, . Pituitary dysfunction in systemic disorders. In: Melmed S., ed. The Pituitary. 4th Ed. Academic Press, 2017:365-381. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gopal-Kothandapani JS, Bagga V, Wharton SB, Connolly DJ, Sinha S, Dimitri PJ. Xanthogranulomatous hypophysitis: a rare and often mistaken pituitary lesion. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2015;2015:140089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Joshi MN, Whitelaw BC, Carroll PV. Mechanisms in endocrinology: hypophysitis: diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;179(3):R151-R163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lupi I, Manetti L, Raffaelli V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hypophysitis: a short review. J Endocrinol Invest. 2011;34(8):e245-e252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Imga NN, Yildirim AE, Baser OO, Berker D. Clinical and hormonal characteristics of patients with different types of hypophysitis: a single-center experience. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2019;63(1):47-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Lopes MB. Update on hypophysitis and TTF-1 expressing sellar region masses. Brain Pathol. 2013;23(5):495-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kobalka PJ, Huntoon K, Becker AP. Neuropathology of pituitary adenomas and sellar lesions. Neurosurgery. 2021;88(5):900-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leporati P, Landek-Salgado MA, Lupi I, Chiovato L, Caturegli P. IgG4-related hypophysitis: a new addition to the hypophysitis spectrum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1971-1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernreuther C, Illies C, Flitsch J, et al. IgG4-related hypophysitis is highly prevalent among cases of histologically confirmed hypophysitis. Brain Pathol. 2017;27(6):839-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hunn BH, Martin WG, Simpson S Jr, Mclean CA. Idiopathic granulomatous hypophysitis: a systematic review of 82 cases in the literature. Pituitary. 2014;17(4):357-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hanna B, Li YM, Beutler T, Goyal P, Hall WA. Xanthomatous hypophysitis. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22(7):1091-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burt MG, Morey AL, Turner JJ, Pell M, Sheehy JP, Ho KK. Xanthomatous pituitary lesions: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Pituitary. 2003;6(3):161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Lillehei KO, Hankinson TC. Review of xanthomatous lesions of the sella. Brain Pathol. 2017;27(3):377-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang C, Wu H, Bao X, Wang R. Lymphocytic hypophysitis secondary to ruptured rathke cleft cyst: case report and literature review. World Neurosurg. 2018;114:172-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Langlois F, Manea A, Lim DST, et al. High prevalence of adrenal insufficiency at diagnosis and headache recovery in surgically resected Rathke’s cleft cysts-a large retrospective single center study. Endocrine. 2019;63(3):463-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gutenberg A, Caturegli P, Metz I, et al. Necrotizing infundibulo-hypophysitis: an entity too rare to be true? Pituitary. 2012;15(2):202-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amereller F, Küppers AM, Schilbach K, Schopohl J, Störmann S. Clinical characteristics of primary hypophysitis: a single-centre series of 60 cases. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2021;129(3):234-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang S, Wang L, Yao Y, et al. Primary lymphocytic hypophysitis: clinical characteristics and treatment of 50 cases in a single centre in China over 18 years. Clin Endocrinol. 2017;87(2):177-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Honegger J, Schlaffer S, Menzel C, et al. Diagnosis of primary hypophysitis in Germany. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(10):3841-3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oguz SH, Soylemezoglu F, Sendur SN, et al. Clinical characteristics, management, and treatment outcomes of primary hypophysitis: a monocentric cohort. Horm Metab Res. 2020;52(4):220-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Faje AT, Sullivan R, Lawrence D, et al. Ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis: a detailed longitudinal analysis in a large cohort of patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(11):4078-4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. González-Rodríguez E, Rodríguez-Abreu D; Spanish Group for Cancer Immuno-Biotherapy (GETICA) . Immune checkpoint inhibitors: review and management of endocrine adverse events. Oncologist. 2016;21(7):804-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Angelousi A, Cohen C, Sosa S, et al. Clinical, endocrine and imaging characteristics of patients with primary hypophysitis. Horm Metab Res. 2018;50(4):296-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Park SM, Bae JC, Joung JY, et al. Clinical characteristics, management, and outcome of 22 cases of primary hypophysitis. Endocrinol Metab. 2014;29(4):470-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khare S, Jagtap VS, Budyal SR, et al. Primary (autoimmune) hypophysitis: a single centre experience. Pituitary. 2015;18(1):16-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Imber BS, Lee HS, Kunwar S, Blevins LS, Aghi MK. Hypophysitis: a single-center case series. Pituitary. 2015;18(5):630-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lupi I, Cosottini M, Caturegli P, et al. Diabetes insipidus is an unfavorable prognostic factor for response to glucocorticoids in patients with autoimmune hypophysitis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177(2):127-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Atkins P, Ur E. Primary and ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis: a single-center case series. Endocr Res. 2020;45(4):246-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chiloiro S, Tartaglione T, Angelini F, et al. An overview of diagnosis of primary autoimmune hypophysitis in a prospective single-center experience. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104(3):280-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Honegger J, Buchfelder M, Schlaffer S, et al. Treatment of primary hypophysitis in Germany. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100(9): 3460-3469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kyriacou A, Gnanalingham K, Kearney T. Lymphocytic hypophysitis: modern day management with limited role for surgery. Pituitary. 2017;20(2):241-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Korkmaz OP, Sahin S, Ozkaya HM, et al. Primary hypophysitis: experience of a single tertiary center. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2021;129(1):14-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krishnappa B, Shah R, Sarathi V, et al. Early pulse glucocorticoid therapy and improved hormonal outcomes in primary hypophysitis. Neuroendocrinology. Published online March 2021. doi:10.1159/000516006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Takahashi Y. Mechanisms in endocrinology: autoimmune hypopituitarism: novel mechanistic insights. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;182(4):R59-R66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fleseriu M, Hashim IA, Karavitaki N, et al. Hormonal replacement in hypopituitarism in adults: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(11):3888-3921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gutenberg A, Larsen J, Lupi I, Rohde V, Caturegli P. A radiologic score to distinguish autoimmune hypophysitis from nonsecreting pituitary adenoma preoperatively. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(9):1766-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Leung GK, Lopes MB, Thorner MO, Vance ML, Laws ER Jr. Primary hypophysitis: a single-center experience in 16 cases. J Neurosurg. 2004;101(2):262-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Caranci F, Leone G, Ponsiglione A, et al. Imaging findings in hypophysitis: a review. Radiol Med. 2020;125(3):319-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chiloiro S, Tartaglione T, Capoluongo ED, et al. Hypophysitis outcome and factors predicting responsiveness to glucocorticoid therapy: a prospective and double-arm study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(10):3877-3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Karaca Z, Tanriverdi F, Unluhizarci K, Kelestimur F, Donmez H. Empty sella may be the final outcome in lymphocytic hypophysitis. Endocr Res. 2009;34(1-2):10-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gao H, Gu YY, Qiu MC. Autoimmune hypophysitis may eventually become empty sella. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2013;34(2):102-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nikouline A, Carr D. Postpartum headache: a broader differential. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;39:258.e5-258.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cerbone M, Visser J, Bulwer C, et al. Management of children and young people with idiopathic pituitary stalk thickening, central diabetes insipidus, or both: a national clinical practice consensus guideline. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(9):662-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Frara S, Rodriguez-Carnero G, Formenti AM, et al. Pituitary tumors centers of excellence. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2020;49(3): 553-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Catford S, Wang YY, Wong R. Pituitary stalk lesions: systematic review and clinical guidance. Clin Endocrinol. 2016;85(4):507-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Guaraldi F, Giordano R, Grottoli S, et al. Pituitary autoimmunity. Front Horm Res 2017;48:48-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ricciuti A, De Remigis A, Landek-Salgado MA, et al. Detection of pituitary antibodies by immunofluorescence: approach and results in patients with pituitary diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(5):1758-1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Carmichael JD. Update on the diagnosis and management of hypophysitis. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2012;19(4):314-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bellastella G, Maiorino MI, Bizzarro A, et al. Revisitation of autoimmune hypophysitis: knowledge and uncertainties on pathophysiological and clinical aspects. Pituitary. 2016;19(6):625-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tokue A, Higuchi T, Arisaka Y, Nakajima T, Tokue H, Tsushima Y. Role of F-18 FDG PET/CT in assessing IgG4-related disease with inflammation of head and neck glands. Ann Nucl Med. 2015;29(6):499-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gutenberg A, Hans V, Puchner MJ, et al. Primary hypophysitis: clinical-pathological correlations. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155(1):101-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Langrand C, Bihan H, Raverot G, et al. Hypothalamo-pituitary sarcoidosis: a multicenter study of 24 patients. QJM. 2012;105(10):981-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kaltsas GA, Powles TB, Evanson J, et al. Hypothalamo-pituitary abnormalities in adult patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis: clinical, endocrinological, and radiological features and response to treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(4):1370-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kristof RA, Van Roost D, Klingmüller D, Springer W, Schramm J. Lymphocytic hypophysitis: non-invasive diagnosis and treatment by high dose methylprednisolone pulse therapy? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67(3):398-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schreckinger M, Francis T, Rajah G, Jagannathan J, Guthikonda M, Mittal S. Novel strategy to treat a case of recurrent lymphocytic hypophysitis using rituximab. J Neurosurg. 2012;116(6):1318-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Carruthers MN, Topazian MD, Khosroshahi A, et al. Rituximab for IgG4-related disease: a prospective, open-label trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1171-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Byrne TN, Stone JH, Pillai SS, Rapalino O, Deshpande V. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 31-2016. A 53-year-old man with diplopia, polydipsia, and polyuria. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1469-1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Xu C, Ricciuti A, Caturegli P, Keene CD, Kargi AY. Autoimmune lymphocytic hypophysitis in association with autoimmune eye disease and sequential treatment with infliximab and rituximab. Pituitary. 2015;18(4):441-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ray DK, Yen CP, Vance ML, Laws ER, Lopes B, Sheehan JP. Gamma knife surgery for lymphocytic hypophysitis. J Neurosurg. 2010;112(1):118-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pekic S, Bogosavljevic V, Peker S, et al. Lymphocytic hypophysitis successfully treated with stereotactic radiosurgery: case report and review of the literature. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2018;79(1):77-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chalan P, Thomas N, Caturegli P. Th17 cells contribute to the pathology of autoimmune hypophysitis. J Immunol. 2021;206(11):2536-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Patel DD, Kuchroo VK. Th17 cell pathway in human immunity: lessons from genetics and therapeutic interventions. Immunity. 2015;43(6):1040-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Khosroshahi A, Wallace ZS, Crowe JL, et al. ; Second International Symposium on IgG4-Related Disease . International consensus guidance statement on the management and treatment of IgG4-related disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(7):1688-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Seymour M, Robertson T, Papacostas J, et al. A woman with visual loss, amenorrhoea and polyuria: the first reported case of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma presenting with hypopituitarism. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep Published online May 2021. doi:10.1530/EDM-20-0100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Oksanen V. New cerebrospinal fluid, neurophysiological and neuroradiological examinations in the diagnosis and follow-up of neurosarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis. 1987;4(2):105-110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis–diagnosis and management. QJM. 1999;92(2):103-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gu Y, Sun X, Peng M, Zhang T, Shi J, Mao J. Pituitary involvement in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis: case series and literature review. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(8):1467-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Vega-Beyhart A, Medina-Rangel IR, Hinojosa-Azaola A, et al. Pituitary dysfunction in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(2):595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ben Abid F, Abukhattab M, Karim H, Agab M, Al-Bozom I, Ibrahim WH. Primary pituitary tuberculosis revisited. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:391-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Husain N, Husain M, Rao P. Pituitary tuberculosis mimicking idiopathic granulomatous hypophysitis. Pituitary. 2008;11(3):313-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Aubart FC, Idbaih A, Emile JF, et al. Histiocytosis and the nervous system: from diagnosis to targeted therapies. Neuro Oncol 2021;23(9):1433-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tillotson CV, Anjum F, Patel BC.. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. StatPearls. Last updated July 19, 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430885/ [Google Scholar]

- 80. Garg N, Lavi ES. Clinical and neuroimaging manifestations of erdheim-chester disease: a review. J Neuroimaging. 2021;31(1):35-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gulati N, Allen CE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: version 2021. Hematol Oncol. 2021;39Suppl 1:15-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Salama HA, Jazieh AR, Alhejazi AY, et al. Highlights of the management of adult histiocytic disorders: Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Erdheim-Chester disease, Rosai-Dorfman disease, and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21(1):e66-e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Radojkovic D, Pesic M, Dimic D, et al. Localised Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the hypothalamic-pituitary region: case report and literature review. Hormones. 2018;17(1):119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Shikuma J, Kan K, Ito R, et al. Critical review of IgG4-related hypophysitis. Pituitary. 2017;20(2):282-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Li Y, Gao H, Li Z, Zhang X, Ding Y, Li F. Clinical characteristics of 76 patients with IgG4-related hypophysitis: a systematic literature review. Int J Endocrinol. 2019;2019:5382640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Iseda I, Hida K, Tone A, et al. Prednisolone markedly reduced serum IgG4 levels along with the improvement of pituitary mass and anterior pituitary function in a patient with IgG4-related infundibulo-hypophysitis. Endocr J. 2014;61(2):195-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Liu Y, Wang L, Zhang W, et al. Hypophyseal involvement in immunoglobulin G4-related disease: a retrospective study from a single tertiary center. Int J Endocrinol. 2018;2018:7637435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lin W, Lu S, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of immunoglobulin G4-related disease: a prospective study of 118 Chinese patients. Rheumatology. 2015;54(11):1982-1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Boharoon H, Tomlinson J, Limback-Stanic C, et al. A case series of patients with isolated IgG4-related hypophysitis treated with rituximab. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4(6):bvaa048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Iwama S, De Remigis A, Callahan MK, Slovin SF, Wolchok JD, Caturegli P. Pituitary expression of CTLA-4 mediates hypophysitis secondary to administration of CTLA-4 blocking antibody. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(230):230ra45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Wright JJ, Powers AC, Johnson DB. Endocrine toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(7):389-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Tahir SA, Gao J, Miura Y, et al. Autoimmune antibodies correlate with immune checkpoint therapy-induced toxicities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(44):22246-22251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Faje A, Reynolds K, Zubiri L, et al. Hypophysitis secondary to nivolumab and pembrolizumab is a clinical entity distinct from ipilimumab-associated hypophysitis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;181(3):211-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Dillard T, Yedinak CG, Alumkal J, Fleseriu M. Anti-CTLA-4 antibody therapy associated autoimmune hypophysitis: serious immune related adverse events across a spectrum of cancer subtypes. Pituitary. 2010;13(1):29-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Fernandes S, Varlamov EV, McCartney S, Fleseriu M. A novel etiology of hypophysitis: immune checkpoint inhibitors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):387-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Caturegli P, Di Dalmazi G, Lombardi M, et al. Hypophysitis secondary to cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 blockade: insights into pathogenesis from an autopsy series. Am J Pathol. 2016;186(12):3225-3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Iglesias P, Sánchez JC, Díez JJ. Isolated ACTH deficiency induced by cancer immunotherapy: a systematic review. Pituitary. 2021;24(4):630-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Albarel F, Castinetti F, Brue T. Management of endocrine disease: immune check point inhibitors-induced hypophysitis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;181(3):R107-R118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Bancos I, Hahner S, Tomlinson J, Arlt W. Diagnosis and management of adrenal insufficiency. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(3):216-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Corsello SM, Barnabei A, Marchetti P, De Vecchis L, Salvatori R, Torino F. Endocrine side effects induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(4):1361-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Couey MA, Bell RB, Patel AA, et al. Delayed immune-related events (DIRE) after discontinuation of immunotherapy: diagnostic hazard of autoimmunity at a distance. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee . Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 4):iv119-iv142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al. ; National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(17):1714-1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Girotra M, Hansen A, Farooki A, et al. Investigational Drug Steering Committee (IDSC) Immunotherapy Task Force collaboration . The current understanding of the endocrine effects from immune checkpoint inhibitors and recommendations for management. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018;2(3):pky021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Tsoli M, Kaltsas G, Angelousi A, Alexandraki K, Randeva H, Kassi E. Managing ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis: challenges and current therapeutic strategies. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:9551-9561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Faje AT, Lawrence D, Flaherty K, et al. High-dose glucocorticoids for the treatment of ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis is associated with reduced survival in patients with melanoma. Cancer. 2018;124(18):3706-3714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Faje A. Hypophysitis: evaluation and management. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;2:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Prodam F, Caputo M, Mele C, Marzullo P, Aimaretti G. Insights into non-classic and emerging causes of hypopituitarism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(2):114-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Kanie K, Iguchi G, Inuzuka M, et al. Two cases of anti-PIT-1 hypophysitis exhibited as a form of paraneoplastic syndrome not associated with thymoma. J Endocr Soc. 2020;5(3):bvaa194. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvaa194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Yamamoto M, Iguchi G, Bando H, et al. Autoimmune pituitary disease: new concepts with clinical implications. Endocr Rev 2020;41(2):bnz003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Bando H, Iguchi G, Kanie K, et al. Isolated adrenocorticotropic hormone deficiency as a form of paraneoplastic syndrome. Pituitary. 2018;21(5):480-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.