Abstract

Background

Parents and family carers of children with complex needs experience a high level of pressure to meet children's needs while maintaining family functioning and, as a consequence, often experience reduced well‐being and elevated psychological distress. Peer support interventions are intended to improve parent and carer well‐being by enhancing the social support available to them. Support may be delivered via peer mentoring or through support groups (peer or facilitator led).

Peer support interventions are widely available, but the potential benefits and risks of such interventions are not well established.

Objectives

To assess the effects of peer support interventions (compared to usual care or alternate interventions) on psychological and psychosocial outcomes, including adverse outcomes, for parents and other family carers of children with complex needs in any setting.

Search methods

We searched the following resources.

• Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; latest issue: April 2014), in the Cochrane Library.

• MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1966 to 19 March 2014).

• Embase (OvidSP) (1974 to 18 March 2014).

• Journals@OVID (22 April 2014).

• PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1887 to 19 March 2014).

• BiblioMap (EPPI‐Centre, Health Promotion Research database) (22 April 2014).

• ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (26 May 2014).

• metaRegister of Controlled Trials (13 May 2014).

We conducted a search update of the following databases.

• MEDLINE (OvidSP) (2013 to 20 February 2018) (search overlapped to 2013).

• PsycINFO (ProQuest) (2013 to 20 February 2018).

• Embase (Elsevier) (2013 to 21 February 2018).

We handsearched the reference lists of included studies and four key journals (European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: 31 March 2015; Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders: 30 March 2015; Diabetes Educator: 7 April 2015; Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: 13 April 2015). We contacted key investigators and consulted key advocacy groups for advice on identifying unpublished data.

We ran updated searches on 14 August 2019 and on 25 May 2021. Studies identified in these searches as eligible for full‐text review are listed as "Studies awaiting classification" and will be assessed in a future update.

Selection criteria

Randomised and cluster randomised controlled trials (RCTs and cluster RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs were eligible for inclusion. Controlled before‐and‐after and interrupted time series studies were eligible for inclusion if they met criteria set by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group. The comparator could be usual care or an alternative intervention. The population eligible for inclusion consisted of parents and other family carers of children with any complex needs. We applied no restriction on setting.

Data collection and analysis

Inclusion decisions were made independently by two authors, with differences resolved by a third author. Extraction to data extraction templates was conducted independently by two authors and cross‐checked. Risk of bias assessments were made independently by two authors and were reported according to Cochrane guidelines. All measures of treatment effect were continuous and were analysed in Review Manager version 5.3. GRADE assessments were undertaken independently by two review authors, with differences resolved by discussion.

Main results

We included 22 studies (21 RCTs, 1 quasi‐RCT) of 2404 participants. Sixteen studies compared peer support to usual care; three studies compared peer support to an alternative intervention and to usual care but only data from the usual care arm contributed to results; and three studies compared peer support to an alternative intervention only.

We judged risk of bias as moderate to high across all studies, particularly for selection, performance, and detection bias.

Included studies contributed data to seven effect estimates compared to usual care: psychological distress (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.10, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.32 to 0.11; 8 studies, 864 participants), confidence and self‐efficacy (SMD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.14 to 0.21; 8 studies, 542 participants), perception of coping (SMD ‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.21; 3 studies, 293 participants), quality of life and life satisfaction (SMD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.32 to 0.38; 2 studies, 143 participants), family functioning (SMD 0.15, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.38; 4 studies, 272 participants), perceived social support (SMD 0.31, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.77; 4 studies, 191 participants), and confidence and skill in navigating medical services (SMD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.28; 4 studies, 304 participants). In comparisons to alternative interventions, one pooled effect estimate was possible: psychological distress (SMD 0.2, 95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.79; 2 studies, 95 participants). No studies reported on adverse outcomes.

All narratively synthesised data for psychological distress (compared to usual care ‐ 2 studies), family functioning (compared to usual care ‐ 1 study; compared to an alternative intervention ‐ 1 study), perceived social support (compared to usual care ‐ 2 studies), and self‐efficacy (compared to alternative interventions ‐ 1 study) were equivocal. Comparisons with usual care showed no difference between intervention and control groups (perceived social support), some effect over time for both groups but more effect for intervention (distress), or mixed effects for intervention (family function). Comparisons with alternative interventions showed no difference between the intervention of interest and the alternative. This may indicate similar effects to the intervention of interest or lack of effect of both, and we are uncertain which option is likely.

We found no clear evidence of effects of peer support interventions on any parent outcome, for any comparator; however, the certainty of evidence for each outcome was low to very low, and true effects may differ substantially from those reported here.

We found no evidence of adverse events such as mood contagion, negative group interactions, or worsened psychological health.

Qualitative data suggest that parents and carers value peer support interventions and appreciate emotional support.

Authors' conclusions

Parents and carers of children with complex needs perceive peer support interventions as valuable, but this review found no evidence of either benefit or harm. Currently, there is uncertainty about the effects of peer support interventions for parents and carers of children with complex needs. However, given the overall low to very low certainty of available evidence, our estimates showing no effects of interventions may very well change with further research of higher quality.

Plain language summary

Peer support interventions for parents and carers of children with complex needs

Review question

This review assessed whether peer support interventions improve outcomes for parents and others caring for children with a wide range of complex needs (such as chronic or severe acute illness, disability, or delayed development).

Background

Parents and other family carers who care for children with complex needs may experience increased distress and reduced well‐being. Peer support interventions are intended to assist people caring for children to find social support from others who understand their situation. Peer support can be provided in groups, which sometimes are led by a facilitator, or can occur when people are matched with individual parents who have experience caring for a child with a similar condition.

Study characteristics

We included research up to 21 February 2018. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cluster RCTs, quasi‐RCTs, controlled before‐and‐after studies, and interrupted time series studies were all eligible for inclusion. Studies were included if they measured distress, confidence, feelings of coping, quality of life, how families functioned, feelings of support, or confidence in dealing with services among parents or any other family carers. Children being cared for could have any condition (for example, chronic or severe acute illness, disability, any kind of delayed or atypical development).

Results

We found 22 studies of 2404 participants who were caring for children with a wide range of conditions. All studies were RCTs or quasi‐RCTs and compared peer support to usual care (comparison 1) or to another intervention (comparison 2). Peer support was delivered in hospitals and in the community. Although we found studies that evaluated effects of peer support on all outcomes in comparison 1, and several outcomes in comparison 2, we did not see any benefit from peer support compared to usual care or compared to another intervention. We found no studies that reported on adverse effects (such as stress from hearing others' stories or conflicts with group members). Feedback from parents and carers suggests that they value emotional support, validation of their experiences, and access to knowledge that they find in peer support groups. More information is needed about training and supervision of peer support leaders, and about whether many participants withdraw from groups (and if so, why).

The overall quality of evidence for each outcome was low to very low, and because of this, our certainty about these findings is low. This means that further research is likely to change these findings while making clearer the possible benefits or harms of peer support interventions.

Conclusion

At the moment, we are uncertain about whether peer support helps or harms parents and carers of children with complex needs.

Summary of findings

Background

Many studies have found that parents and other family carers of children with complex needs, such as disability, developmental delay or learning difficulties, or other chronic or complex conditions such as autism spectrum disorder, experience exceptional pressure to meet the emotional and physical needs of the affected child or children, while at the same time maintaining family functioning (Cheshire 2010; Lee 2007; McGuire 2004; Resch 2010; Strunk 2010). (In this review, we use 'carers' to refer to family carers only, not paid professional carers).

Parents (and carers in a parenting role) of children with complex needs often show poor results on markers of psychosocial well‐being such as quality of life and life satisfaction, and they show elevated levels of psychological distress such as depression, anxiety, or stress (Cheshire 2010; McGuire 2004; Resch 2010).

The daily caregiving activities and responsibilities of parents of children with complex needs can be more time‐consuming than parenting a typically developing child, and can be physically and emotionally demanding (McGuire 2004; Resch 2010). These demands on the parent’s/carer’s time and energy can reduce the resources available for other meaningful and health‐protective activities such as employment, social activities, exercise, and hobbies. Family and social relationships can be disrupted and parents (or carers) left feeling overwhelmed, isolated, and lacking support (McGuire 2004; Resch 2010; Strunk 2010).

Description of the condition

Families of children with complex needs report experiencing more stress than families of children who do not have complex needs, regardless of the child's particular condition (Tak 2002; Van Riper 1992).

Demands of caregiving

Parents caring for children with complex needs experience anxiety about their child's diagnosis and prognosis, and may experience short‐term emotional distress, loneliness, uncertainty, and symptoms of depression (Barlow 2006). Physical caregiving activities, supporting provision of therapy, and advocating for the child can prove extremely time‐consuming (McGuire 2004). Parents may have difficulty gaining access to the services and resources they need (Banach 2010).

Behavioural problems may cause stress for families regardless of the underlying condition. For example, in families where children have developmental delay, behavioural problems resulting from the delay were reported to be a greater contributor to increased parenting stress than the developmental delay itself (Baker 2002). Parents may lack confidence in dealing with behavioural issues and may experience difficulty finding or accessing support services (Twoy 2007).

Changes to family life

Reviews have found that chronic diseases in children interfere with daily family life, increasing parents' burden of care (Barlow 2006). Balancing the healthcare needs of the affected child against other family needs, with reduced time for other necessary or enjoyable activities, is a source of family stress (Banach 2010). In addition to stresses directly related to the child's condition, families of children with complex needs must adapt to new roles, adjust their lives to cope with the needs of the child, and accommodate increased strain on family resources. As well as managing the needs of the affected child and of any other children in the family, parents must cope with their own chronic stress and periodic family crises (Bourke‐Taylor 2010; Dellve 2006).

Social stigma and isolation

Families that include a child with a chronic illness are at increased risk of isolation from formal and informal social support mechanisms (Tak 2002). Challenging behaviours and those due to emotional or cognitive conditions, which are seen by others as 'odd', may make social outings difficult ‐ a problem exacerbated by lack of understanding of the underlying condition among members of the community (Twoy 2007). This means that parents may choose isolation over the frustrations of taking their child out in public (Tak 2002). Physical frailty of the child, which may limits the child's ability to travel beyond the home, may similarly restrict parents' ability to maintain social networks.

Parents often feel the need to assist family and friends in handling their feelings about their child's condition, and to educate them and others such as workmates and acquaintances about the condition (Dellve 2006). Parents may feel stigmatised, either through the direct actions and comments of others, or indirectly through their own attributions and anxieties about what others might be thinking. As a result, they may restrict social activities or may socialise only with other families whose children have a similar diagnosis. In some cases, families may be excluded by others from social gatherings (Gray 2002).

Positive outcomes for families

Although families of children with complex needs face a range of challenges, in recent decades the benefits and rewards of raising a child with challenging behaviours or complex needs have been increasingly recognised. Families report feeling an enhanced sense of meaning or purpose and personal growth, and their positive perceptions of their role may be as high or higher than that of families of typically developing children (Blacher 2007; Hastings 2002). Social‐cultural constraints (such as service inefficiencies, perceived stigma, financial hardship, and low levels of support) have been found to contribute more to the negative impact of raising a child with complex needs than demands strictly associated with raising the child (Green 2007; Mas 2016; McConnell 2014).

Description of the intervention

The intervention of interest is peer support in the form of networks or groups for parents and carers of children with complex needs. Peer support may encompass peer‐led or facilitator‐led interventions, where the focus is on fostering peer‐to‐peer interactions and increasing social support. Peer support can be provided one‐to‐one or in a group, and may be given face‐to‐face or may be technology‐assisted (e.g. conducted by telephone or internet).

The aims of peer support interventions vary. However, for the purposes of this systematic review, we were interested in interventions intended to enhance the social support (perceived and/or actual) available to participants and to improve the well‐being of parents and carers across a range of psychological and psychosocial indicators.

How the intervention might work

Peer support interventions are assumed to work by increasing the amount of social support available to parents and carers of children with complex needs and providing that support in a form that is most useful and acceptable to families. It has been suggested that families of children with complex needs who display similar levels of function to families of children without such needs do so because they had current or prior affiliation with a support group (together with time and resources to adjust to the diagnosis) (Van Riper 1992). The perceived availability of support may play as great a role in determining stress levels in affected families as the actual support provided (Duarte 2005).

Peer support interventions are intended to supplement parents' existing social networks and to reduce feelings of isolation and stigma by introducing individuals who otherwise might not meet to others who can appreciate and understand their experiences (Shilling 2013). Participants' circumstances should be similar but need not be identical (Dale 2008). For example, parents who are in the early stages of adjusting to a diagnosis may benefit from the expertise of parents who have been coping longer with a diagnosis; parents who have been living with their child's condition for some time benefit from feeling that their experiences have meaning for others and from taking on an expert role.

Given the complexity of the emotional experience of raising a child with complex needs, peer support may work not by decreasing the negative impact or difficulties that parents experience, but rather by enhancing or encouraging the development of a new sense of meaning and purpose, opportunities for growth, and positive appraisals of their child and their caring role (Green 2007; Hastings 2002; Mas 2016; McConnell 2014). Although social support is the primary goal, peer support interventions may additionally increase instrumental (tangible) support for parents by increasing access to local social and health services, and may improve parents' knowledge about and confidence in managing their child's illness and other family issues.

Benefits of social support

Social support, defined as a combination of emotional concern, instrumental (tangible) aid, information, and appraisal, may mediate the stress experienced by families of children with serious physical, emotional, or behavioural challenges by contributing to coping resources (Coppola 2013; Dunkel‐Schetter 1987; Lazarus 1987). Social support may be of benefit for those who provide it as well as for those who receive it (Ignaki 2017). Such support has been found to reduce stress, for example, among parents of children with severe learning difficulties (Quine 1991). Social integration and support protect against the potentially harmful effects of stressful family circumstances and have beneficial effects on well‐being, whether or not a person is currently under stress (Armstrong 2005).

Emotional support and hope

Reports from practitioners working with parents of children with complex needs reveal that these parents want emotional support (e.g. someone to listen and understand), want to know of others in a similar situation who are doing well, and want to hear stories from others that give them hope for the future and make them feel less alone (Kirk 2015; Santelli 1996).

Reduction of isolation and stigma

Stigma, whether experienced or feared, can lead parents to avoid contact with others. Combined with the time‐consuming care tasks undertaken by these parents, this may mean increased risk of isolation for the families of children with complex needs. Social support can be an effective buffer against isolation (Kerr 2000).

Incidental learning

As well as buffering against stress, social support can have a direct effect on parenting stress by increasing exposure to incidental learning opportunities and competence‐promoting social interactions. Parents can benefit from the experience and knowledge of their peers without taking part in overt training and information sessions. A general survey of interactions between socio‐economic status, positive and negative parenting behaviours, and child difficulties recommended interventions to strengthen parents' social relationships with the goals of reducing stress and creating opportunities for parents to learn from and affirm one another (McConnell 2011).

Advocacy and self‐efficacy

Social support has been linked with enhanced advocacy skills and confidence in parents of children with complex needs (Banach 2010).

Instrumental support

Instrumental (tangible) support that parents and carers value includes information about specific disabilities and caring for children with complex needs, as well as ways to find and gain access to services and community resources (Santelli 1996).

Reciprocity

Social support provided by peers is suggested to provide reciprocal benefits: those receiving support gain the advantages described above, and people providing support report enhanced quality of life and validation of their previous experiences (Santelli 1997; Schwartz 1999). It has been suggested that social support must be reciprocal (or the possibility of reciprocity must at least exist) to be maximally effective (Hogan 2002). A group of peers of similar status provide a plausible arena for this egalitarian give‐and‐take of mutual support, in contradistinction to the power imbalance that may exist between service provider and service recipient.

Why it is important to do this review

A large number of self‐help and peer support groups and programmes target parents and carers of children with complex needs (Canary 2008; Davies 2005; Hastings 2004; Law 2001). These groups aim to provide “social support, practical information, and a sense of shared purpose or advocacy” (King 2000, p. 226). It is widely believed that these groups and programmes improve parental well‐being through social support mechanisms and peer support provided through sharing of experiences, information, and understanding, and provision of adaptive and credible models of coping (Davies 2005; King 2000; Lee 2007; McGuire 2004). However, despite anecdotal reports that these benefits are derived from participation in such groups and programmes (Ainbinder 1998; Davies 2005; Hartman 1992; Law 2001), little research has been undertaken to investigate the outcomes of participation in these groups and programmes for the parent/carer and the family in general.

Social support networks are not always uniformly positive in effect (Ortega 2002). Peer support groups have the potential to damage self‐esteem by reinforcing parents' self‐image as a member of a stigmatised group, and social comparison can lead to negative affect (Hogan 2002); so it is important to find out if, when, and how peer support interventions help, what barriers might exist to people's access to peer support, and if negative effects are known.

Some reviews in this general area already exist. We identified seven Cochrane Reviews relevant to this topic, but all were concerned with peer support for adult participants who were directly experiencing a condition or were supporting another adult with a condition, rather than supporting a child with a condition; some assessed interventions for which peer support was one component. Doull 2005 and Doull 2004 are protocols only. They have been withdrawn and will not be proceeding. Dale 2008 assessed the effectiveness of peer support telephone calls in improving physical, psychological, and behavioural health outcomes among adults; Lavender 2013 investigated telephone support for women during pregnancy and six weeks postpartum; and Chamberlain 2017 investigated psychosocial interventions for smoking cessation among pregnant women. Treanor 2019 assessed psychosocial interventions designed to improve quality of life and other outcomes for caregivers of people living with cancer; some of those interventions included a peer support component. González‐Fraile 2021 assessed the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions (including remotely delivered support interventions promoting interactions with peers) in preventing or reducing caregiver burden among family members of people with dementia.

Some interventions examined were similar to those considered in this review, although we are considering a potentially broader range of groups and settings. However, there is only limited overlap with our population ‐ adults, but adults considered in their role as carers of children ‐ and with our conditions and outcomes of interest, which are sequelae to caring for children with complex needs rather than conditions directly affecting adults.

We also identified two recent non‐Cochrane reviews that are relevant to this review. Niela‐Vilén 2014 conducted a review of internet‐based peer support for parents. This is a highly relevant type of intervention, but the population (any parents, not only parents of children with complex needs) is less relevant.

Shilling 2013 conducted an integrative review of parent‐to‐parent (mentoring) support interventions. Again, this is a relevant intervention type, and unlike the other reviews we identified was of interventions for parents of children with chronic disabling conditions. However, the current review considers a broader range of intervention types including face‐to‐face and online parent support groups.

Objectives

Primary

To assess the effects of peer support interventions (compared to usual care or alternative interventions) on a range of psychological and psychosocial outcomes, including adverse outcomes, for parents and other family carers of children with complex needs in any setting

Secondary

Given that caring and financial demands on these parents and carers are high, to collect and report data related to barriers to participation, as evaluated in any qualitative research on intervention effectiveness

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster RCTs, controlled before‐and‐after (CBA) studies, and interrupted times series (ITS) studies were eligible for inclusion in this review. Quasi‐RCTs (trials in which random allocation was attempted, but a method of allocation that was not strictly random, such as alternation, day of the week, or date of birth, was used) were also accepted.

To be included in this review, CBA and ITS studies had to meet the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group (EPOC) criteria (Ryan 2011). These specify, for CBA designs, at least two intervention sites and two control sites, comparable timing of measurements for control and intervention groups, and comparable key characteristics for control and intervention groups; and for ITS designs, a clearly specified intervention time point and at least three data collection points before and after that intervention.

We included studies with a broad range of control groups, including no‐treatment, wait list, and usual care controls. When a study compared peer support with an alternative intervention (with or without a usual care control), the study was included but could not be included in meta‐analyses with studies in which peer support was compared with a no‐treatment control.

We incorporated evidence from quantitative studies that also had a qualitative component (Noyes 2011b). We did not conduct a separate search for qualitative studies and therefore could neither include qualitative‐only studies nor conduct an exhaustive review of mixed‐methods studies.

Types of participants

Participants were parents and other family carers of children with complex needs (as reported in the included study) for whom complex needs include chronic or severe acute illness, disability, or delayed/atypical development or an enduring condition in the physical, psychological, developmental, or intellectual domain. 'Parents' could be encompassed in studies where participants were biological, adoptive, or foster parents; mothers only; fathers only; or both parents. 'Family carers' could include any adults acting in a parenting role, including grandparents. Studies in which participants were professional (paid) carers were excluded from this review.

'Children with complex needs' was defined in the broadest possible terms to include children with any acute or chronic medical or psychological condition with a relatively long‐lasting course or sequelae.

Children were defined as individuals aged 18 years or younger.

Types of interventions

The target intervention was provision of peer support through networks or groups. Peer support was defined in this review as the existence of a community of common interest where people gather (in person or virtually by telephone or computer) to share experiences, ask questions, provide emotional support, and gain self‐help (Eysenbach 2004; Iscoe 1985). This is consonant with definitions used in published Cochrane Reviews (e.g. Dale 2008; Kew 2016, with the additional stipulation that specific knowledge possessed by the peer group is concrete, pragmatic, and derived from personal experience rather than through formal training; and that the group consists of individuals who are perceived to be equal (Dale 2008). Peer support interventions can range from purely emergent, informal, and member‐driven approaches to those that are mandated, professionally driven, and formal (Doull 2005).

Peer support encompasses a continuum of interventions of various degrees of formality, all of which emphasise the role of personal experience in the provision of peer support. Interventions that utilise a formal or professional facilitator were included, provided the facilitator's role was to manage group interpersonal processes rather than solely to provide counselling or psychoeducation.

We included one‐to‐one mentor (also known as peer‐to‐peer) and group parent/carer support interventions and both face‐to‐face interventions and those that were technology‐assisted (i.e. conducted over the telephone or internet). This range of intervention types were classified into two categories: (1) support groups for parents and/or carers, with or without a facilitator, that were conducted online or face‐to‐face; and (2) mentor arrangements, in which a 'novice' parent or carer was matched with a more experienced parent or carer.

We included the following comparisons in this review.

Any peer support intervention delivered to parents or carers of children with complex needs versus control (no‐treatment, wait list, or usual care).

Any peer support intervention versus another psychosocial intervention.

We excluded studies if we judged that effects of the peer intervention could not be separated from those of other intervention components, or if peer support was a 'side effect' of participation in some other intervention. Thus, we excluded studies in which the primary focus was something other than developing and supporting peer networks (e.g. where professionals deliver an educative component or formal therapy) and in which improved peer networks were an incidental outcome.

If the peer support intervention was used as an active control for a trial evaluating a more intensive intervention (e.g. a non‐directive peer support group versus a psychoeducation or therapy group), we included the study; however, such studies could not be included in meta‐analyses unless there was also a no‐treatment control condition.

We included studies in which the client or the focus of the intervention is the child only if direct outcomes for parents and carers were measured. For example, interventions for which the child is the primary client (such as play groups and early intervention programmes) and in which parent peer support is an incidental assumed outcome were excluded from the review, unless this support and other parental outcomes were directly measured.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the psychosocial well‐being of parents and carers, as measured by a range of psychological, psychosocial, and skills acquisition outcomes for participants.

As social support (the target of the intervention) and psychosocial well‐being (the primary intervention outcome) are somewhat nebulous concepts, we operationalised the primary outcome using constructs developed by the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group (CHCP 2012).

We used the following parent outcome categories.

-

Psychological health outcomes.

Psychological distress.

Confidence and self‐efficacy.

Perception of coping.

-

Psychosocial outcomes.

Quality of life and life satisfaction.

Family functioning.

Perceived social support.

-

Skills acquisition outcomes.

Confidence and skill in navigating medical services.

When a study used both sub‐scales and full scales related to the same outcome (e.g. a full psychiatric distress scale and anxiety and depression sub‐scales from other measures), we followed advice from Cochrane Australia and used the full, and most general, scale in analyses. In one case in which a study used both depression and anxiety sub‐scales but no more general scale, we chose the sub‐scale that led to a more even distribution of depression versus anxiety sub‐scales across all studies.

-

Adverse outcomes.

Mood contagion.

Increased feelings of stigma from identifying with the group.

Negative group interactions.

Any decrease in psychological health on the measures listed above.

As the measures for adverse outcomes fit the same broad categories as those for beneficial outcomes, we adopted the strategy outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions of assessing beneficial and adverse effects together by the same method, with common eligibility criteria for included studies (Higgins 2011a).

The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions suggests grouping outcomes into short‐term, medium‐term, and long‐term, and taking no more than one of each from each study (Higgins 2011a). We have preferred longer‐ over shorter‐term outcomes when conducting meta‐analyses.

Secondary outcomes

Satisfaction with the intervention (when data were available)

Incidental learning/improved knowledge (when data were available)

Process factors

Process factors that may influence outcomes include the following.

Facilitators of and barriers to uptake of peer support interventions.

Participant and provider satisfaction or dissatisfaction with peer support interventions.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases and resources.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; latest issue: April 2014), in the Cochrane Library.

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1966 to 19 March 2014).

Embase (OvidSP) (1974 to 18 March 2014).

Journals@OVID (22 April 2014).

PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1887 to 19 March 2014).

BiblioMap (EPPI‐Centre, Health Promotion Research database) (22 April 2014).

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (26 May 2014).

metaRegister of Controlled Trials (13 May 2014).

We conducted a search update of the following databases.

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (2013 to 20 February 2018) (search overlapped to 2013 to ensure subsequent additions to 2013‐2014 were captured).

PsycINFO (ProQuest) (2013 to 20 February 2018).

Embase (Elsevier) (2013 to 21 February 2018).

Our search strategy was developed with the assistance of John Kis‐Rigo, Information Specialist at the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group, and is presented in Appendices 1 through 6.

A further search update was conducted on 14 August 2019, and again on 25 May 2021, by Anne Parkhill of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group, using the existing search strategy.

The Cochrane Library (2015‐).

Embase Classic + Embase (2018‐).

MEDLINE (2018‐).

PsycINFO (2018‐).

We placed no restrictions on publication date, publication status, or language. We sought unpublished studies, and we translated abstracts of potentially relevant studies to determine suitability for inclusion.

Searching other resources

ClinicalTrials.gov (13 May 2014).

World Health Organization Clinical Trials Registry (13 May 2014).

SCOPUS (13 May 2014).

Evidence in Health and Social Care (15 May 2014).

New York Academy of Medicine (8 May 2014).

OpenGrey (15 May 2014).

We conducted handsearches of the reference lists of included studies and relevant journals to identify other potentially eligible studies.

European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (31 March 2015).

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (30 March 2015).

Diabetes Educator (7 April 2015).

Journal of Intellectual Disability Research (13 April 2015).

We consulted advocacy and support groups via our existing professional connections with disability support and early childhood agencies to request information on any studies they were aware of: Down Syndrome Victoria, the Cerebral Palsy League, Tresillian Family Care Centres, and Women's and Children's Health Network. We contacted key investigators identified through other searches for advice on identifying other unpublished data and studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Bibliographic details of all search results were consolidated and duplicate records removed using EndNote. These were exported to Excel and were rated for potential inclusion independently by two review authors (GS/AP and GS/VL) based on title and abstract review. Differences were resolved by a third review author (VL or AP). Decisions about inclusion and exclusion were recorded in Excel.

We retrieved full texts for all studies assessed as possibly relevant on the basis of title and abstract review. The same two review authors (GS/AP) assessed studies for inclusion using Criteria for considering studies for this review, with the third review author (VL) also assessing studies on which the first two review authors disagreed. If decisions still were not clear, differences were resolved by discussion amongst all three review authors. Any studies examined in full text but excluded are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table along with reasons for exclusion. When several papers were related to the same trial, the trial ‐ not the papers related to it ‐ was counted. The unit of reporting is the trial ‐ not the number of papers.

Data extraction and management

For included studies, two review authors (GS/AP) independently extracted data, using the data extraction template provided by the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group for quantitative data related to intervention effectiveness (see Appendix 1) (Ryan 2011). Any qualitative data associated with included studies were recorded on a template adapted from the qualitative data extraction template used by Noyes and Popay (2007, cited in Noyes 2011a), with modifications to enable extraction of data related to the process outcomes described above (Types of outcome measures) (see Appendix 2).

When details were not included in the published study or were unclear, we attempted to contact study authors for further information (see Appendix 3 for details of contacts attempted).

Data extracted by one review author were cross‐checked and confirmed by another; any discrepancies were resolved by discussion. All data were pasted from the checked data extraction sheets directly into RevMan software (Review Manager 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and reported the risk of bias of included studies using the guidelines listed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b), in keeping with advice provided by the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group (Ryan 2011). These guidelines assess the following domains: random sequence generation; allocation sequence concealment; blinding (participants, personnel); blinding (outcome assessment); completeness of outcome data (attrition), selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias (e.g. pre‐existing significant differences in characteristics likely to affect parent outcomes; aspects of treatment as usual that may have been a confound; issues with agency recruitment). We judged each item as being at high, low, or unclear risk of bias, as set out in the data extraction template adapted by the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group (Ryan 2011, adapted from Higgins 2011a).

RCTs were deemed to be at highest risk of bias if they were scored as being at high risk of bias in the sequence generation, allocation concealment, or incomplete outcome data domain. RCTs were assessed as at unclear risk of bias if they were rated as unclear in at least one of these three domains. Low risk of bias studies were defined as those receiving a low risk of bias rating in all three of the sequence generation, allocation concealment, and incomplete outcome data domains of the tool.

Quasi‐RCTs were rated as being at high risk of bias on the random sequence generation item of the 'Risk of bias' tool.

No CBA or ITS studies were identified as eligible for inclusion.

Two review authors (GS/AP) independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies, with any disagreements resolved by discussion and consensus. When necessary, we attempted to contact study authors for clarification of methods (see Appendix 3).

All studies meeting inclusion criteria were included in our data synthesis, regardless of the outcome of the 'Risk of bias' assessment. If future updates of this review include non‐randomised studies (such as CBA or ITS designs), we will assess risk of bias with regard to selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias, as suggested in Section 13.5.2.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b).

Assessment of qualitative data

The qualitative data extraction template given as an example in Noyes 2011a was adapted for use in this review, with quality assessed for the domains of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

Measures of treatment effect

All outcomes from studies included in meta‐analyses were continuous. We used final values scores in preference to change‐from‐baseline scores.

There was variability in the types of measures used to assess outcomes. For example, psychological distress was measured on the Psychiatric Symptom Index (total and sub‐scales) the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, the Parenting Stress Index, and the Profile of Mood States (short form). We calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) for each outcome using mean, standard deviation, and numbers of people assessed in control and intervention groups via the inverse variance method in Review Manager 5 software (Section 9.4.3.2; Higgins 2011a; Review Manager 2014).

When standard deviations were not available, we calculated them from reported confidence intervals using the RevMan calculator.

Some outcomes were assessed on scales with differing directions (e.g. on the Caregiver Strain Questionnaire, a reduction in score indicates an improved outcome; on the Parent Coping Efficacy Scale, an increased score represents a better outcome). In these instances, the method outlined in Section 9.2.3.2 of Higgins 2011a was used to ensure that all scales had the same direction.

Qualitative data

When qualitative outcomes were reported in the studies included in this review, we performed a qualitative evidence synthesis to supplement our main quantitative data synthesis.

We extracted qualitative data on process factors affecting implementation, such as facilitators and barriers to participation in peer support interventions.

Unit of analysis issues

We considered the level at which randomisation occurred (e.g. individual, cluster, cross‐over) in included studies. We identified no cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion; therefore we did not need to perform corrections for inappropriate units of analysis.

Dealing with missing data

When data were missing, we attempted to contact study authors as described above. When missing data could not be obtained, we imputed these, following consultation with staff at Cochrane Australia, with appropriate adjustments to the standard error to account for added uncertainty in the results. Meta‐analyses did not include a significant quantity of imputed data: for Ireys 1996 we imputed standard deviations (SDs) from two other studies using the same scale; and for Preyde 2003, Flores 2009, and Swallow 2014, we calculated SDs using confidence intervals (CIs). Generally, when study data were insufficient for inclusion, the data were so incomplete as to make it impossible to include the study in the meta‐analysis. When a study was omitted from an outcome meta‐analysis due to lack of data, we have noted this in the narrative synthesis for that outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

When we considered studies similar enough, based on consideration of populations and intervention settings, to allow pooling of data using meta‐analysis, we assessed the degree of heterogeneity by visually inspecting forest plots and by examining the Chi² test for heterogeneity. We quantified heterogeneity by using the I² statistic. We considered an I² value of 50% or more to represent substantial levels of heterogeneity, but we also interpreted this value in light of the size and direction of effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity, based on the P value from the Chi² test (Higgins 2011a).

Assessment of reporting biases

We intended to assess the existence of reporting bias by testing for asymmetry of the funnel plot of intervention effect estimates against the standard error of intervention effect estimates. However, this was not appropriate, as there were no outcomes for which at least 10 studies were included in the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2011a; Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

Although we noted some heterogeneity in participants, settings, and interventions, this was expected, and we considered that they were sufficiently similar to allow for meta‐analyses when data were available. For the one outcome (psychological distress) for which there were enough included studies to allow meta‐analysis by intervention type, we checked this, but it did not lead to different assessments of effectiveness by intervention type. Outcomes did differ across studies, and we present meta‐analyses and narrative syntheses separately by broad outcomes. As expected, our included studies were clinically heterogeneous, and we used a random‐effects model to calculate SMDs. We had intended to convert any outcome SMDs back to differences on a single, well‐understood scale, but given the lack of any intervention effects, this proved unnecessary.

We included RCT (including quasi‐RCT) studies in our meta‐analyses. No CBA or ITS studies were eligible for inclusion. As we noted substantial risk of bias for nearly all outcomes, we did not stratify meta‐analyses into low versus high or unclear risk of bias.

Results for studies included in the review but not suitable for meta‐analysis were presented in the narrative synthesis for the appropriate outcome. We used the summary of risk of bias of an outcome across studies to judge the robustness of this evidence (Cash‐Gibson 2012). We used tables of results to form a narrative assessment of the evidence, clustering studies by intervention type and setting. For each study, we reported the same elements of information in the same order (Section 11.7.2; Higgins 2011a).

We conducted statistical analyses by using the latest version of RevMan software (Review Manager 2014).

Synthesis of qualitative data

A limited quantity of qualitative data were available for review; we followed advice from the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group ‐ Ryan 2016 ‐ and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Methods Programme ‐ Popay 2006 ‐ in synthesising these data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As discussed in the Background, subgroups of the population may differ in their capacity to benefit from the intervention, and intervention mode and setting may influence outcomes for different subgroups. We had intended to investigate the effects of variables such as existing social connectedness of participants, as well as delivery mode, setting, duration, and size of effects of interventions on outcomes. However, data were insufficient for subgroup analyses to be appropriate. Heterogeneity of data was taken into account when the certainty of evidence for each outcome was judged.

Sensitivity analysis

It was possible to use only SMDs for continuous outcomes due to the wide range of outcome measures used, and we found no dichotomous outcome measures for which it was necessary to make any decisions regarding types of ratios to be used. Therefore it was not appropriate to conduct sensitivity analyses for these variables. When we needed to impute data, we checked the effects of differing assumptions on our analyses and found that none were discernible.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

'Summary of findings' tables were based on the methods described in Schünemann 2011. We assessed the quality of evidence using the GRADE system ‐ Schünemann 2011 ‐ and GRADEpro software (www.guidelinedevelopment.org). Two review authors independently assessed the certainty of evidence for each outcome; when GRADE scores differed for an outcome, we discussed how we had applied the relevant criterion and come to a consensus score.

Consumer participation

The review authors have strong links with early childhood and disability advocacy agencies in Australia. We sent our contacts in these agencies drafts of the protocol and review and sought their comments, especially on recommendations regarding consumer‐important outcomes reported in the 'Summary of findings'. We used our connections with local consumer agencies to seek input from consumers overseas. Both the protocol and the review received input from a consumer as part of standard Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group editorial processes.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

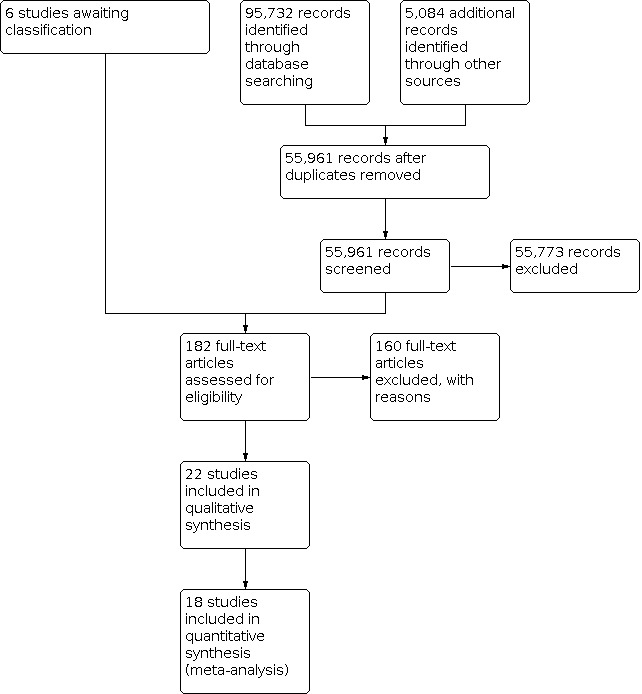

We identified 95,732 records from electronic database searches and 5084 records through other sources (see flow chart of study selection in Figure 1). After removing duplicates, we screened 55,961 records by title and abstract. We excluded 55,773 records at this stage. We obtained 182 records in full text, excluding 160 records. Reasons for exclusion of key excluded studies are detailed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. A summary of reasons (chiefly methodological) for excluding other studies is provided in Table 3. Six studies are awaiting classification. These were identified through recent updates to the searches, or they are papers for which we have not been able to obtain full text copies (details are in Studies awaiting classification). We approached authors of 9 subsequently excluded and 10 subsequently included studies for further information (see Appendix 3). One author of an included study could not be contacted. Authors of 13 studies provided further details, and authors of 6 studies did not respond.

1.

Study flow diagram.

1. Summary of reasons for excluding studies.

| Reason for exclusion | N |

| Intervention was not focused on parents/caregivers | 2 |

| Participants were carers of adults or the elderly | 6 |

| Participants were carers of a child without complex needs | 2 |

| Intervention was not peer support | 30 |

| Effects of the intervention were not able to be separated from other intervention components | 6 |

| Intervention outcomes not focused on parent/caregiver | 2 |

| Intervention outcomes not focused on psychological, psychosocial, or skills acquisition domains | 2 |

| Study design did not meet criteria for RCT, quasi‐RCT, CBA, or ITS | 50 |

| Study design was not an evaluation (e.g. descriptive, case study) | 26 |

| Qualitative data only | 3 |

| Review | 5 |

| Duplicates only identified at full text stage | 10 |

| TOTAL (does not include 16 studies described separately) | 144 |

Included studies

Twenty‐two studies including 2404 participants met selection criteria for inclusion in this review. Of these, 16 compared peer support interventions with a usual care control (Aiello 2015; Boogerd 2017; Boylan 2013; Flores 2009; Ireys 1996; Ireys 2001; Kutash 2011; Kutash 2013; McCallion 2004; Preyde 2003; Ruffolo 2005; Silver 1997; Singer 1999; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010; Swallow 2014). Three other studies compared peer support with an alternative intervention, as well as a usual care control (Roberts 2011; Scharer 2009; Wysocki 2008). In meta‐analyses of these studies, only peer support and usual care control findings were included. Three studies compared peer support with an alternative intervention only (Ferrin 2014; Rhodes 2008; Singer 1994). These studies could not be included in meta‐analyses but are part of our narrative synthesis. Additionally, Aiello 2015 did not include data in a format suitable for inclusion in a meta‐analysis.

Detailed information from all included studies is provided in the Characteristics of included studies tables. Key information is summarised below, and interventions evaluated by included studies are summarised in Table 4.

2. Characteristics of interventions.

| ID | Intervention type | Intervention details | Design | Population |

| Aiello 2015 | Parent groups | Asynchronous online tools used to share text messages, photos, and videos, and participate in discussion forums. Moderated by Speech Language Pathologists and Psychologist who proposed topics and answered questions but did not interfere in direct interactions between facilitators | RCT | Mothers of children with severe and profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss |

| Boogerd 2017 | Parent groups | Secure web‐based portal, one for each participating clinic. Peer support facilitated through chat‐application and forum. Site also provides for one‐to‐one communication with health professionals and downloadable information. Forum is moderated by nurse practitioners. Free access for the duration of the evaluation |

RCT | Parents of children with type 1 diabetes. |

| Boylan 2013 | Parent groups | Ninety minute sessions held weekly for eight weeks. Small and large group discussions of relevant issues. Aim was to provide social support and improve communication and problem‐solving skills. | RCT | Parents and carers of young people with deliberate self‐harm/suicidal behaviour. |

| Ferrin 2014 | Parent groups | Groups of eight‐ten families met for 12 weekly 90 minute sessions. Families could share thoughts and experiences in a safe, non‐directive environment. Therapist present but precluded from providing feedback, psycho‐education, information or advice. Control also included 12 weekly, 90 minutes sessions. Psycho‐education was provided for the first 9 sessions. The last 3 sessions included behavioural strategies for managing ADHD symptoms and reducing defiant behaviour. There was also some opportunity for group discussion and support. |

RCT Comparator is psycho‐education |

Parents of children and adolescents (5‐18) with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. |

| Flores 2009 | Parent mentors | Home visit from mentor within three days of child’s emergency department visit or hospitalisation. Then monthly meetings with assigned families at community centre. (Thus, there was a strong support group element as well). Numbers attending meetings varied. | RCT | African‐American and Latino parents of children (2‐18) with asthma. |

| Ireys 1996 | Parent mentors | Each parent mentor had child (now aged 18‐24) with JRA and was matched with five families of children with JRA. Over 15 months, mentors had fortnightly telephone contact and six‐weekly face‐to‐face meetings with mothers. They also hosted occasional group events. Thirty hours’ training for mentors. | RCT | Mothers of children (2‐11) with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. |

| Ireys 2001 | Parent mentors | Parents of child with chronic illness linked with veteran “Network Mother” who’s child with chronic illness was then in young adulthood. Over 15 months, mentors had fortnightly telephone contact and seven face‐to‐face meetings with mothers. They also hosted occasional group events. Thirty hours’ training for mentors. | RCT | Mothers of children (7‐11) with chronic illnesses. |

| Kutash 2011 | Parent mentor | School‐based peer‐to‐peer. Veteran parents telephoned participants once per week during school year for support. Veteran parents had 30 hours’ training in communication skills, active listening, reframing, empowerment, boundary issues, ED topics, confidentiality. Weekly group supervision with clinically trained staff member. | RCT | Parents of middle school youth in special education programs for emotional disturbance. |

| Kutash 2013 | Parent mentor | School‐based peer‐to‐peer. Veteran parents telephoned participants once per week during school year for support. Veteran parents had 30 hours’ training in communication skills, active listening, reframing, empowerment, boundary issues, ED topics, confidentiality. Weekly group supervision with clinically trained staff member. | RCT | Parents of middle school youth in special education programs for emotional disturbance. |

| McCallion 2004 | Parent groups | Facilitated support groups; 8‐10 grandparent caregivers attended six fortnightly sessions of 90 minutes. Respite care and transport assistance provided. In addition to educational topics, sessions covered self‐care such as stress reduction, relaxation, nutrition, and own health needs. Led by community agency workers, trained and supervised by first author. Also included active case management. | RCT | Grandparents with primary care of at least one grandchild (mean age 11, 5 aged >21) with an intellectual or other developmental disability, learning problem or attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder. |

| Preyde 2003 | Parent mentors | Parents invited to connect with parent buddy (experienced with the NICU) within one week of birth. Support delivered primarily via telephone. Very few details provided. | Quasi‐RCT | Mothers of very pre‐term infants in a neonatal intensive care unit. |

| Rhodes 2008 | Parent group | Ten weekly group sessions of 90 minutes. Facilitated by a counsellor, who took an active role only to answer questions the group could not answer themselves and to encourage/regulate participation. | CBA | Parents of children with an intellectual disability. |

| Roberts 2011 | Parent groups | Manualised, weekly meetings with other parents to discuss topics based on individual interests and needs. Duration uncertain, but child playgroups ran for two hours, for 40 weeks, and it is stated that parent groups were ‘concurrent’. Delivered by transdisciplinary team of teachers, speech pathologists, occupational therapists, psychologists—but not clear if this was for child, parent, or both groups. | RCT | Parents of preschool children with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder who were also eligible for a centre‐based manualized playgroup intervention. |

| Ruffolo 2005 | Parent groups | Highly‐structured problem‐solving groups. Two‐hour meetings held twice monthly, for a minimum of six months. Five to nine parents per group plus leader to facilitate (each group had a parent and a professional leader). Onsite childcare, transport support, and refreshments provided. Parent leaders were parents of children who had previously been engaged in the intensive case management program. Professionals were mental health professionals. Parent and professional leaders were trained together over one day in group processes. |

RCT | Parents of children with a serious emotional disorder. |

| Scharer 2009 | Parent groups | Support group conducted via facilitated online chat room, available weekly. Duration unknown. Facilitated by child and adult psychiatric nurses. Participants could access other parts of the intervention website outside chat room times. | RCT | Mothers of children (5‐12) in child psychiatric units with a serious mental illness. |

| Silver 1997 | Parent mentors | Parent‐to‐Parent Network. Participants attended six face‐to‐face meetings (home or hospital) and received bi‐weekly phone calls over 12 months. Occasional group activities offered. Lay ‘intervenors’ were women who had raised children with ongoing health conditions. Forty hours’ training for mentors. | RCT | Mothers of children (5‐8) with ongoing health conditions (not necessarily chronic: lasting 3 months or requiring hospitalisation for >=30 days in a year). |

| Singer 1994 | Parent groups | Information and emotional support groups held weekly for nine weeks. Duration unclear. Facilitated, with discussion topics chosen by parents. No skills training or homework provided. | RCT Comparator is stress management group |

Parents of children and youths (2‐20) with acquired brain injury. |

| Singer 1999 | Parent mentor | Parents referred to nearest Parent‐to‐Parent program to call and find out details of their matched supporting parent. Supporting parents instructed to make a minimum of four phone calls to participant over two months. Supporting parents received eight to ten hours of training in communication skills, local services, and advocacy and support. | RCT | Parents, carers, or grandparents of a child with a disability. |

| Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004 | Parent mentor | Initial home visit from parent mentor, then negotiated number of home visits and phone calls. On average, three home visits and 13 phone call or emails over six months; however, the ranges were quite wide for each contact type. Mentors were mothers judged by the research team to be successful at managing their child’s diabetes. Matched on child age group (1‐5 or 6‐10 years). |

RCT | Mothers of children with Type I diabetes. |

| Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010 | Parent mentor | Initial home visit or phone call, then further contacts by negotiation, with a minimum of one face‐to‐face visit over 12 months. Mentors as in 2004 study. | RCT | Mothers of children with Type I diabetes. |

| Swallow 2014 | Peer support | Social networking group as part of an online app providing (1) clinical care‐giving support and (2) psychosocial support for caregiving. Very few details about the social networking component provided. App available on secure server via computer, mobile phone, smartphone, tablet. | RCT | Parents of children with chronic kidney disease (stages 3‐5). |

| Wysocki 2008 | Parent groups | Facilitated education and support groups; 12 sessions of 45 minutes with three to five families over six months. | RCT | Parents of children with diabetes. |

Design

Most included studies (21 of 22) were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Aiello 2015; Boogerd 2017; Boylan 2013; Ferrin 2014; Flores 2009; Ireys 1996; Ireys 2001; Kutash 2011; Kutash 2013; McCallion 2004; Rhodes 2008; Roberts 2011; Ruffolo 2005; Scharer 2009; Silver 1997; Singer 1994; Singer 1999; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010; Swallow 2014; Wysocki 2008).

One study was a quasi‐RCT with allocation to treatment condition by alternation (Preyde 2003). We did not identify any controlled before‐and‐after or interrupted time series studies that met inclusion criteria.

Sample size

Studies ranged in size from 15 participants in Singer 1994 to 343 participants in Silver 1997. The median number of participants was 71.

We were able to include in at least one meta‐analysis 1927 participants from 14 studies (Boogerd 2017; Flores 2009; Ireys 1996; Ireys 2001; Kutash 2011; Kutash 2013; McCallion 2004; Preyde 2003; Roberts 2011; Ruffolo 2005; Scharer 2009; Silver 1997; Singer 1999; Swallow 2014); the largest meta‐analysis (8 studies) included 864 participants (psychological distress).

Settings

Studies were based in the United States (14) (Flores 2009; Ireys 1996; Ireys 2001; Kutash 2011; Kutash 2013; McCallion 2004; Ruffolo 2005; Scharer 2009; Silver 1997; Singer 1994; Singer 1999; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010; Wysocki 2008); Australia (2) (Rhodes 2008; Roberts 2011); and Brazil (Aiello 2015), Canada (Preyde 2003), Ireland (Boylan 2013), Spain (Ferrin 2014), The Netherlands (Boogerd 2017), and the UK (Swallow 2014).

Peer support interventions were conducted in the following settings.

Community (14) (Ferrin 2014; Flores 2009; Ireys 1996; Ireys 2001; Kutash 2011; Kutash 2013; McCallion 2004; Roberts 2011; Ruffolo 2005; Silver 1997; Singer 1999; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010; Wysocki 2008).

Online (4) (Aiello 2015; Boogerd 2017; Scharer 2009; Swallow 2014).

Hospital (3) (Boylan 2013; Preyde 2003; Singer 1994).

Outpatient therapy (1) (Rhodes 2008).

Participants

Participants were parents and carers of children with a wide range of chronic physical, developmental, and psychiatric conditions.

Parents of children with diabetes (4 studies) (Boogerd 2017; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010; Wysocki 2008).

Parents of children with emotional disturbance (3 studies) (Kutash 2011; Kutash 2013; Ruffolo 2005).

Parents of children with chronic illness (2 studies) (Ireys 2001; Silver 1997).

Parents of children with a disability (1 study) (Singer 1999).

Parents of children with acquired brain injury (1 study) (Singer 1994).

Parents of children with anorexia nervosa (1 study) (Rhodes 2008).

Parents of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (1 study) (Ferrin 2014).

Parents of children with autism spectrum disorder (1 study) (Roberts 2011).

Parents of children with chronic kidney disease (1 study) (Swallow 2014).

Parents of children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (1 study) (Ireys 1996).

Parents of young people with self‐harm or suicidal behaviour (1 study) (Boylan 2013).

Parents of children with serious mental illness (1 study) (Scharer 2009).

Minority parents of children with asthma (1 study) (Flores 2009).

Mothers of very preterm infants (1 study) (Preyde 2003).

Mothers of children with severe and profound sensorineural hearing loss (1 study) (Aiello 2015).

Grandparents with primary care of children with intellectual disability, other developmental disability, or learning problems, or with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders (1 study) (McCallion 2004).

Interventions

Peer support interventions identified in this review fell into two broad categories.

Support groups for parents and/or carers, with or without a facilitator, which were conducted online or face‐to‐face (11 studies) (Aiello 2015; Boogerd 2017; Boylan 2013; Ferrin 2014; McCallion 2004; Roberts 2011; Ruffolo 2005; Scharer 2009; Singer 1994; Swallow 2014; Wysocki 2008).

Mentor arrangements, whereby a 'novice' parent or carer was matched with a more experienced parent or carer, sometimes referred to as peer‐to‐peer support (11 studies) (Flores 2009; Ireys 1996; Ireys 2001; Kutash 2011; Kutash 2013; Preyde 2003; Rhodes 2008; Silver 1997; Singer 1999; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010).

Parent/carer support groups (11 studies)

The typical purpose of support groups was to encourage parents and carers to share information, concerns, and achievements and to form a mutually supportive network (Roberts 2011). Support group interventions had a wide range of stated aims, such as to:

provide social support and information (Aiello 2015; Boogerd 2017; Boylan 2013);

reduce parental stress, depression, and anxiety (Aiello 2015; Boogerd 2017; Boylan 2013; McCallion 2004; Roberts 2011; Singer 1994);

improve communication, problem‐solving skills, and coping skills (Boylan 2013; Ruffolo 2005); or

increase parent knowledge (Aiello 2015 Boogerd 2017), self‐efficacy, sense of empowerment and caregiving mastery, and perception of competence in managing the child's condition (McCallion 2004; Roberts 2011; Swallow 2014).

Not all trial authors cited a theoretical basis for their support group intervention. Those that were cited included social support as a way of reducing role strain and life disruptions (e.g. McCallion 2004). References in these cases refer to studies citing the models, not to the original models.

Group structures ranged from formal peer support programmes, as in Boylan 2013 and Ruffolo 2005, to self‐help groups with content determined collaboratively by participants and facilitator, as in McCallion 2004, to completely non‐directive groups, as in Ferrin 2014. The format for groups identified in this review was either face‐to‐face (as in Boylan 2013, Ferrin 2014, McCallion 2004, Roberts 2011, Ruffolo 2005, Singer 1994, and Wysocki 2008) or online (as in Aiello 2015, Boogerd 2017, Scharer 2009, and Swallow 2014).

Whether online or face‐to‐face, support groups might include large and small group discussions of relevant information (e.g. Boylan 2013; McCallion 2004; Singer 1994; Wysocki 2008); problem‐solving activity‐based discussions (Ruffolo 2005); and encouragement of emotional expression (Singer 1994). Other components of support groups included homework, skill‐building exercises, free time for socialising (Ruffolo 2005; Wysocki 2008), testimonials from peers, and advice on managing stress (Swallow 2014). To increase parents' access to groups, some interventions also provided in‐home or onsite respite care and transport assistance (McCallion 2004).

Support groups were generally (although not always) led by a facilitator with input from participants (Boylan 2013; Ferrin 2014; McCallion 2004), for example, choosing topics for discussion (McCallion 2004; Singer 1994; Wysocki 2008). If facilitators were involved, these groups were usually non‐directive, with facilitators in some interventions explicitly prohibited from offering feedback, psychoeducation, or advice (Boogerd 2017; Ferrin 2014). When facilitators were more directive, they tended to intervene only to manage group processes, so as to ensure smooth running and full participation of members (Scharer 2009). This aspect of facilitation seemed particularly important in online settings, where peer discussion took place in an online chat room with the facilitator present to monitor.

Some groups included both a professional facilitator and a parent leader (Ruffolo 2005). Only one intervention appeared to have no facilitator or group leaders: an online intervention in which participants had open access to the psychosocial support site (Swallow 2014).

Support group interventions may have been developed following parent focus groups (Boogerd 2017; Boylan 2013), or during a pilot phase (Boogerd 2017). Grandparent recommendations were used to identify material to be covered in grandparent support group sessions (McCallion 2004), and consumers were involved in the development of one online system (Swallow 2014). In many cases, it was not clear whether there was consumer involvement in the design or conduct of the groups.

In most cases, the support group was the main intervention under investigation; in some cases, peer support was an alternate intervention control for more intensive interventions such as a structured psychoeducation programme (Ferrin 2014), an individual home‐based intervention (Roberts 2011), a stress management group (Singer 1994), or a family therapy group (Wysocki 2008). In some instances, peer support was a component of a broader online application (Aiello 2015; Boogerd 2017; Swallow 2014).

Parent/carer mentors (11 studies)

The common purpose of parent mentor (or peer‐to‐peer) interventions was to enhance the mental health of participants (Ireys 2001), while improving parent quality of life (Flores 2009). These interventions included named programmes such as Parent‐to‐Parent (Singer 1999; Silver 1997), Family‐to‐Family Network (Ireys 2001), Parent Connect (Kutash 2011; Kutash 2013), HOMEWARD (Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004), Social Support to Empower Parents (Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010), and unnamed mentoring arrangements (Flores 2009; Ireys 1996; Preyde 2003). The stated aims of interventions were to provide informational, affirmational, and emotional support (Ireys 1996; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010) with the goals of:

reducing parent anxiety, depression, and stress (Ireys 1996; Ireys 2001);

improving carer quality of life (Flores 2009);

reducing caregiver strain (Kutash 2011; Kutash 2013);

improving parents' confidence in managing the child's condition (Rhodes 2008; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004); and

successfully adapting to the challenges of raising a child with a chronic condition (Singer 1999; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004).

Theoretical bases cited for parent mentor interventions included consideration of the impact of social support on parent behaviour and attitudes (Ireys 2001), social support as an extension of coping (Singer 1999), as a determinant of parental mental health (Silver 1997), and as an element of planned behaviour (Kutash 2013).

Parent mentor interventions typically linked participants with a veteran parent who had experience raising a child with a comparable chronic condition (Ireys 2001; Preyde 2003; Rhodes 2008). Peer support might be provided via home visits (Ireys 2001), meetings in community venues (Ireys 2001), or therapeutic settings (Rhodes 2008). Interventions often included telephone contact in addition to face‐to‐face contact (Flores 2009; Ireys 1996; Ireys 2001; Preyde 2003; Silver 1997; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010), or instead of face‐to‐face contact (Kutash 2011; Singer 1999).

Some parent mentor interventions also had a support group component, although this was generally informal and incidental to the mentoring relationship. For example, some parent mentors also convened group meetings with all their assigned families in community venues to encourage social networking and support (Flores 2009). In a school‐based programme (Kutash 2011; Kutash 2013), teachers received extra training and parents received written information (this was provided in control groups as well). One intervention was an adjunct to a well‐established family‐based treatment in which participants had access to a parent mentor and to the mentor's therapist throughout their own family therapy (Rhodes 2008). In at least one case, parent mentors had mandated topics to cover with participants (Silver 1997).

Parent mentors may have received extensive paid or volunteer training in interpersonal skills (as in Ireys 2001 Preyde 2003 and Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010) and in providing affirmational support that recognised the participant's existing competencies (Ireys 1996).

Some but not extensive consumer input was reported for parent mentor/peer‐to‐peer interventions. Parents had input into intervention design in one study (Singer 1999), and participants determined the amount of contact they received from mentors in two other interventions (Silver 1997; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004).

Both intervention types varied widely on salient details such as number and length of group and mentoring sessions, structure of sessions (if any), and training and qualifications of facilitators and mentors. In most studies, interventions tended to be poorly specified; it would not be possible to implement most interventions faithfully from the information published. This was the case whether the peer support intervention was the focus of the study or was used as an alternative treatment control. Generally, measures for ensuring programme fidelity were not reported, although several trial authors reported that fidelity was checked (e.g. Flores 2009; Kutash 2011; Kutash 2013; Roberts 2011).

Because there was such wide variation within intervention categories, we have followed our original protocol and have not conducted separate syntheses for each intervention type, although we considered doing so. With future studies and better‐specified interventions, conducting separate meta‐analyses and narrative syntheses for each intervention type would be an approach worth considering.

Outcomes

Many studies collected data on multiple child and family outcomes, as is shown in the Characteristics of included studies table. In most cases, the peer support intervention was compared with a treatment as usual control only. In other cases, there was a usual care control and another comparator; in a small number of cases, there was no usual care control and peer support was compared only with another intervention; data from these studies could not be included in meta‐analyses. These are noted in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Outcomes included in meta‐analyses and the specific scales used to measure those outcomes are listed below. Nearly all measures were self‐reported; however, this is to be expected given the field of research and the nature of the outcomes. Many of the scales used, particularly for psychological distress and for confidence and self‐efficacy, are well established with reasonable psychometric profiles. Although we considered the measures used when assessing risk of bias (especially performance bias), use of self‐report measures such as those listed here should be considered standard for this research.

-

Psychological distress.

Global psychological distress: Psychiatric Symptom Index (Ireys 1996; Silver 1997); Profile of Mood States (Scharer 2009).

Stress: Parenting Stress Index (Aiello 2015; Boogerd 2017; Ferrin 2014; Roberts 2011); Parent Stress Scale (Boylan 2013).

Anxiety: Psychiatric Symptom Index (anxiety sub‐scale) (Ireys 2001); State Anxiety Inventory (Preyde 2003).

Depression: Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (McCallion 2004).

-

Confidence and self‐efficacy.

Self‐efficacy: Parent Asthma Management Self‐Efficacy Scale (Flores 2009); Parent Efficacy Scale (Rhodes 2008); Parental Confidence Questionnaire (Sullivan‐Bolyai 2004; Sullivan‐Bolyai 2010).